En muchos países, las mujeres han estado subrepresentadas en el gobierno y en diferentes instituciones. [1] Esta tendencia histórica aún persiste, aunque cada vez más mujeres son elegidas para ser jefas de Estado y de gobierno . [2] [3]

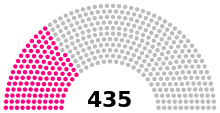

En octubre de 2019, la tasa de participación mundial de las mujeres en los parlamentos nacionales era del 24,5 %. [4] En 2013, las mujeres representaban el 8 % de todos los líderes nacionales y el 2 % de todos los puestos presidenciales. Además, el 75 % de todas las primeras ministras y presidentas han asumido el cargo en las últimas dos décadas. [5]

Las mujeres pueden enfrentarse a una serie de retos que afectan a su capacidad de participar en la vida política y convertirse en dirigentes políticas. Varios países están estudiando medidas que puedan aumentar la participación de las mujeres en el gobierno a todos los niveles, desde el local hasta el nacional e internacional. Sin embargo, en la actualidad hay más mujeres que aspiran a ocupar puestos de liderazgo.

Las mujeres han estado notablemente en menor número en el poder ejecutivo del gobierno. Sin embargo, la brecha de género se ha ido cerrando, aunque lentamente, y las mujeres siguen estando subrepresentadas. [6]

Las siguientes mujeres líderes son actualmente jefas de Estado o jefas de gobierno de su nación:

.jpg/440px-The_Queen_and_Margaret_Thatcher_1_July_1979_(6992989180).jpg)

Las revoluciones socialistas que tuvieron lugar durante la Primera Guerra Mundial vieron a las primeras mujeres convertirse en miembros de gobiernos. Yevgenia Bosch ocupó el cargo de Ministra del Interior y Líder interina del Secretariado Popular de Ucrania , uno de los varios órganos de gobierno en competencia en la República Popular de Ucrania , predecesora de la Ucrania soviética (se proclamó como República Soviética de Rusia el 25 de enero de 1918). A veces se la considera la primera mujer moderna líder de un gobierno nacional. [7]

Las primeras mujeres que ocuparon puestos de jefatura de Estado , además de las gobernantes hereditarias , lo hicieron en países socialistas. Khertek Anchimaa-Toka dirigió la República Popular de Tuvan , un estado poco reconocido que hoy forma parte de Rusia, de 1940 a 1944. Sükhbaataryn Yanjmaa fue líder interina de la República Popular de Mongolia entre 1953 y 1954 y Soong Ching-ling fue copresidenta interina de la República Popular China entre 1968 y 1972 y nuevamente en 1981.

La primera mujer elegida democráticamente como primera ministra (jefa de gobierno) de un país soberano fue Sirimavo Bandaranaike de Ceilán (hoy Sri Lanka) en 1960-1965. Volvió a ocupar el cargo en 1970-77 y 1994-2000; un total de 17 años. Otras primeras ministras elegidas de forma temprana fueron Indira Gandhi de la India (1966-1977; volvió a ocupar el cargo en 1980-1984), Golda Meir de Israel (1969-1974) y Margaret Thatcher del Reino Unido (1979-1990). Angela Merkel de Alemania es la mujer que ha ocupado el cargo de jefa de gobierno durante más tiempo (de forma continuada) (2005-2021). [8]

La primera mujer en ostentar el título de « presidenta », en lugar de reina o primera ministra, fue Isabel Perón de Argentina (nombrada jefa de Estado y de gobierno, 1974-76). La primera presidenta electa del mundo fue Vigdís Finnbogadóttir de Islandia , cuyo mandato duró de 1980 a 1996. Es la jefa de Estado electa de cualquier país con más años en el cargo hasta la fecha. Corazón Aquino , presidenta de Filipinas (1986-1992), fue la primera mujer presidenta del sudeste asiático .

Benazir Bhutto , primera ministra de Pakistán (1988-1990), fue la primera mujer primera ministra de un país de mayoría musulmana . Volvió a ocupar el cargo entre 1993 y 1996. La segunda fue Khaleda Zia (1991-1996) de Bangladesh . Tansu Çiller de Turquía fue la primera mujer musulmana elegida primera ministra en Europa (1993-1996).

Elisabeth Domitien fue nombrada primera ministra de la República Centroafricana (1975-1976). Carmen Pereira de Guinea-Bissau (1984) y Sylvie Kinigi de Burundi (1993) ejercieron como jefas de Estado durante 2 días y 101 días respectivamente. Ruth Perry de Liberia fue la primera mujer designada como jefa de Estado en África (1996-1997). Diez años después, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf de Liberia fue la primera mujer elegida como jefa de Estado en África (2006-2018).

Sri Lanka fue la primera nación en tener una presidenta, Chandrika Kumaratunga (1994-2000), y una primera ministra ( Sirimavo Bandaranaike ) simultáneamente. Esto también marcó la primera vez que una primera ministra (Sirimavo Bandaranaike) sucedió directamente a otra primera ministra (Chandrika Kumaratunga). La elección de Mary McAleese como presidenta de Irlanda (1997-2011) fue la primera vez que una presidenta sucedió directamente a otra presidenta, Mary Robinson . Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir , primera ministra de Islandia (2009-2013), fue la primera líder mundial abiertamente lesbiana, la primera líder mundial femenina en casarse con una pareja del mismo sexo mientras estaba en el cargo.

La primera mujer nombrada presidenta de la Comisión Europea fue Ursula von der Leyen en 2019.

Isabel II , jefa de Estado del Reino Unido y los reinos de la Commonwealth desde 1952 hasta 2022, es la jefa de Estado y la reina con el reinado más prolongado en la historia mundial.

Cuando Barbados se convirtió en república el último día de noviembre de 2021, se convirtió en la primera nación en tener una mujer como presidenta, Sandra Mason . El país aún no ha tenido un presidente hombre.

Sofia Panina fue la primera viceministra de Bienestar Estatal y viceministra de Educación del mundo en Rusia en 1917. Alexandra Kollontai se convirtió en la primera mujer en ocupar un puesto ministerial, como Comisaria del Pueblo para el Bienestar Social en la Rusia Soviética en octubre de 1917. [9] Yevgenia Bosch ocupó el cargo de Ministra del Interior y Líder interina del Secretariado Popular de Ucrania desde diciembre de 1917 hasta marzo de 1918. La condesa Markievicz fue Ministra de Trabajo en la República de Irlanda de 1919 a 1922.

La primera mujer ministra del mundo en un gabinete de gobierno reconocido internacionalmente fue Nina Bang , ministra de Educación danesa de 1924 a 1926. Margaret Bondfield fue ministra de Trabajo en el Reino Unido de 1929 a 1931; fue la primera mujer ministra de gabinete y la primera mujer miembro del Consejo Privado del Reino Unido . [10] Dolgor Puntsag fue la primera mujer ministra de Salud del mundo en Mongolia en 1930. La primera mujer en ocupar el cargo de ministra de finanzas fue Varvara Yakovleva , comisaria del pueblo de finanzas de la Unión Soviética de 1930 a 1937. Frances Perkins , secretaria de Trabajo de 1933 a 1945, fue la primera mujer en ocupar un puesto en el gabinete del gobierno federal de los Estados Unidos. En 1938, Azerbaiyán nombró a la primera mujer ministra de Justicia , Ayna Sultanova . En 1947, Ana Pauker, de Rumania , fue la primera mujer ministra de Asuntos Exteriores , cargo que ocupó durante cuatro años. Qian Ying, de China, fue la primera mujer ministra del Interior , de 1959 a 1960. La primera mujer que ocupó el cargo de ministra de Defensa fue Sirimavo Bandaranaike , de Ceilán , de 1960 a 1965.

Si bien la representación de las mujeres como ministras aumentó durante el siglo XX, hasta el siglo XXI las mujeres que ocupaban los puestos más altos del gabinete eran relativamente poco frecuentes. En los últimos años, las mujeres han ocupado cada vez más los puestos más importantes de sus gobiernos en áreas no tradicionales para las mujeres en el gobierno, como las relaciones exteriores, la defensa y la seguridad nacional, y las finanzas o los ingresos.

Kamala Harris es la primera mujer en ocupar el cargo de vicepresidenta de los Estados Unidos, lo que la convierte en la mujer política de mayor rango en la historia de ese país. Janet Yellen es la primera mujer en ocupar el cargo de secretaria del Tesoro de los Estados Unidos, tras haber sido presidenta de la Reserva Federal y presidenta del Consejo de Asesores Económicos de la Casa Blanca. [11]

Yevgenia Bosch , líder militar bolchevique , ocupó el cargo de Secretario del Pueblo de Asuntos Internos en la República Popular de Ucrania de los Soviets de Obreros y Campesinos de 1917 a 1918, que era responsable de las funciones ejecutivas de la República Popular de Ucrania , parte de la República Soviética de Rusia . [12] [13] [14]

Nellie Ross fue la primera mujer en prestar juramento como gobernadora de un estado de EE. UU. en enero de 1925, seguida ese mismo mes por Miriam A. Ferguson .

Louise Schröder fue la primera mujer miembro de la Asamblea Nacional de Weimar . Tras la división de Alemania tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, ejerció como alcaldesa de Berlín Occidental entre 1948 y 1951.

Sucheta Kripalani fue la primera mujer ministra principal de la India y se desempeñó como jefa del gobierno de Uttar Pradesh entre 1963 y 1967.

Savka Dabčević-Kučar , de la República Socialista de Croacia (1967-1969), fue la primera mujer que ocupó el cargo de primera ministra de un estado constituyente europeo no soberano. Ocupó el cargo de presidenta del Consejo Ejecutivo (primera ministra) de Croacia cuando era una república constituyente de la República Federativa Socialista de Yugoslavia .

Imelda Marcos fue gobernadora de Metro Manila en Filipinas desde 1975 hasta 1986, cuando la Revolución del Poder Popular derrocó a los Marcos y obligó a la familia al exilio.

Griselda Álvarez fue la primera mujer gobernadora de México , ejerciendo el cargo de gobernadora del estado de Colima de 1979 a 1985.

Carrie Lam se convirtió en la primera mujer jefa ejecutiva de Hong Kong en 2017 y antes de eso fue Secretaria Jefa de Administración desde 2012.

Claudia Sheinbaum es la primera alcaldesa de la Ciudad de México . Es la jefa de la jurisdicción gubernamental más poblada administrada por una mujer en América y la tercera en el mundo (después de la canciller Angela Merkel de Alemania y la primera ministra Sheikh Hasina de Bangladesh).

El número de mujeres líderes en todo el mundo ha aumentado, pero aún representan un grupo pequeño. [15] En los niveles ejecutivos de gobierno, las mujeres se convierten en primeras ministras con mayor frecuencia que en presidentas. Parte de las diferencias en estos caminos hacia el poder es que las primeras ministras son elegidas por los propios miembros de los partidos políticos, mientras que los presidentes son elegidos por el público. En 2013, las mujeres representaban el 8 por ciento de todos los líderes nacionales y el 2 por ciento de todos los puestos presidenciales. Además, el 75 por ciento de todas las primeras ministras y presidentas han asumido el cargo en las últimas dos décadas. [5] Desde 1960 hasta 2015, 108 mujeres se han convertido en líderes nacionales en 70 países, y más de ellas han sido primeras ministras que presidentas. [16]

Las ejecutivas suelen tener un alto nivel de educación y pueden tener relaciones estrechas con familias políticamente importantes o de clase alta. La situación general de la mujer en un país no predice si una mujer alcanzará un puesto ejecutivo ya que, paradójicamente, las ejecutivas han ascendido sistemáticamente al poder en países donde la posición social de las mujeres está por detrás de la de los hombres. [17]

En los países más desarrollados, las mujeres han luchado durante mucho tiempo para llegar a ser presidentas o primeras ministras. Israel eligió a su primera primera ministra en 1969, pero nunca volvió a hacerlo. En cambio, Estados Unidos no ha tenido ninguna presidenta. [18]

Sri Lanka fue la primera nación en tener una presidenta, Chandrika Kumaratunga (1994-2000), y una primera ministra ( Sirimavo Bandaranaike ) simultáneamente. Esto también marcó la primera vez que una primera ministra (Sirimavo Bandaranaike) sucedió directamente a otra primera ministra (Chandrika Kumaratunga). La elección de Mary McAleese como presidenta de Irlanda (1997-2011) fue la primera vez que una presidenta sucedió directamente a otra presidenta, Mary Robinson . Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir , primera ministra de Islandia (2009-2013), fue la primera líder mundial abiertamente lesbiana del mundo, la primera líder mundial femenina en casarse con una pareja del mismo sexo mientras estaba en el cargo. Barbados fue la primera nación en tener una presidenta inaugural, Sandra Mason (desde 2021); por lo tanto, el país no ha tenido presidentes hombres.

La jefa de gobierno no perteneciente a la realeza que más tiempo ha estado en el cargo y la líder femenina que más tiempo ha estado en el cargo en un país es Sheikh Hasina . Es la primera ministra que más tiempo ha estado en el cargo en la historia de Bangladesh , habiendo servido durante un total combinado de 100 años.20 años, 303 días. A partir del 27 de septiembre de 2024, es la mujer elegida jefa de gobierno con más años en el cargo en el mundo . [19] [20] [21]

En 2021, Estonia se convirtió en el primer país en tener una mujer elegida como jefa de Estado y una mujer elegida como jefa de Gobierno. [22] (Si solo se consideran los países donde el jefe de Estado es elegido directamente, entonces el primer país en tener una mujer elegida como jefa de Estado y una mujer elegida como jefa de Gobierno es Moldavia, también en 2021). [23]

En mayo de 2024, 28 mujeres se desempeñan como jefas de estado y/o de gobierno en 28 países. De ellas, 15 se desempeñan como jefas de estado y 16 como jefas de gobierno . El estatus social de las mujeres no se correlaciona necesariamente con su probabilidad de alcanzar altos puestos ejecutivos, como lo demuestra el surgimiento de muchas líderes femeninas en naciones donde las mujeres generalmente tienen un estatus social más bajo. Ejemplos notables incluyen Sri Lanka , que fue el primer país en tener una presidenta y una primera ministra simultáneamente, y Barbados , que ha tenido una jefa de estado desde que se convirtió en una república. [24]

La proporción de mujeres en los parlamentos nacionales de todo el mundo está creciendo, pero aún están subrepresentadas. [25] Al 1 de abril de 2019, el promedio mundial de mujeres en las asambleas nacionales es del 24,3 por ciento. [26] Al mismo tiempo, existen grandes diferencias entre países, por ejemplo, Sri Lanka tiene tasas de participación femenina bastante bajas en el parlamento en comparación con Ruanda, Cuba y Bolivia, donde las tasas de representación femenina son las más altas. [27] Tres de los diez principales países en 2019 estaban en América Latina (Bolivia, Cuba y México), y los estadounidenses han visto el mayor cambio agregado en los últimos 20 años. [28]

De 192 países enumerados en orden descendente por el porcentaje de mujeres en la cámara baja o única, los 20 países principales con la mayor representación de mujeres en los parlamentos nacionales son (las cifras reflejan información al 1 de enero de 2020; a – representa una legislatura unicameral sin cámara alta): [27]

Hay nuevas cifras disponibles hasta febrero de 2014 de IDEA Internacional, la Universidad de Estocolmo y la Unión Interparlamentaria. [29]

Aunque el 86% de los países han alcanzado al menos el 10% de mujeres en su legislatura nacional, muchos menos han cruzado las barreras del 20% y el 30%. A julio de 2019, solo el 23% de las naciones soberanas tenían más del 30% de mujeres en el parlamento . Las principales democracias de habla inglesa se ubican principalmente en el 40% superior de los países clasificados. Nueva Zelanda ocupa el puesto número 5 con mujeres que comprenden el 48,3% de su parlamento. El Reino Unido (32,0% en la cámara baja, 26,4% en la cámara alta) ocupa el puesto número 39, mientras que Australia (30,5% en la cámara baja, 48,7% en la cámara alta) ocupa el puesto número 47 de 189 países. Canadá ocupa el puesto 60 (29,6% en la cámara baja, 46,7% en la cámara alta), mientras que Estados Unidos ocupa el puesto 78 (23,6% en la cámara baja, 25,0% en la cámara alta). [27] No todas estas cámaras baja y/o alta en los parlamentos nacionales son elegidas directamente; por ejemplo, en Canadá, los miembros de la cámara alta (el Senado) son designados.

Al 1 de marzo de 2022 [update], Cuba tiene el porcentaje más alto entre los países sin cuota. [30] En el sur de Asia, Nepal ocupa el primer lugar en el ranking de participación de mujeres en política con (33%). [31] Entre los países de Asia oriental , Taiwán tiene el mayor porcentaje de mujeres en el Parlamento (38,0%).

Pamela Paxton describe tres factores que son razones por las cuales la representación a nivel nacional se ha vuelto mucho mayor en las últimas décadas. [32] El primero es el cambio en las condiciones estructurales y económicas de las naciones, que dice que los avances educativos junto con un aumento en la participación de las mujeres en la fuerza laboral fomenta la representación. [33] El segundo es el factor político; la representación de las mujeres en el cargo se basa en un sistema de proporcionalidad. Algunos sistemas de votación están construidos de manera que un partido que obtiene el 25% de los votos obtiene el 25% de los escaños. En estos procesos, un partido político se siente obligado a equilibrar la representación dentro de sus votos entre los géneros, aumentando la actividad de las mujeres en la posición política. Un sistema de pluralidad-mayoría , como el utilizado en los Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido y la India, solo permite elecciones de un solo candidato y, por lo tanto, permite a los partidos políticos dictar por completo los representantes de las regiones incluso si solo controlan una pequeña mayoría de los votos. Por último, está la disposición ideológica de un país; el concepto de que los aspectos culturales de los roles o posiciones de las mujeres en los lugares donde viven determinan su posición en esa sociedad, y en última instancia, ayudan o impiden que esas mujeres ocupen puestos políticos. [33]

En 1995, las Naciones Unidas fijaron como meta una representación femenina del 30% [34] . La tasa actual de crecimiento anual de las mujeres en los parlamentos nacionales es de alrededor del 0,5% en todo el mundo. A este ritmo, la paridad de género en las legislaturas nacionales no se alcanzará hasta 2068 [35].

En Brasil, la Secretaría de Políticas para las Mujeres fue hasta hace poco el principal organismo estatal de feminismo a nivel federal. Bajo los gobiernos del Partido de los Trabajadores (2003-2016), Brasil implementó políticas centradas en las mujeres en tres dimensiones de su política exterior: diplomacia, cooperación para el desarrollo y seguridad. [36]

En Irlanda, Ann Marie O'Brien ha estudiado a las mujeres en el Departamento de Asuntos Exteriores irlandés asociado con la Sociedad de Naciones y las Naciones Unidas, 1923-1976. Ella concluye que las mujeres tenían mayores oportunidades en la ONU. [37]

En los Estados Unidos, Frances E. Willis se unió al Servicio Exterior en 1927, convirtiéndose en la tercera mujer estadounidense en hacerlo. Trabajó en Chile, Suecia, Bélgica, España, Gran Bretaña y Finlandia, así como en el Departamento de Estado. En 1953, se convirtió en la primera embajadora estadounidense en Suiza y más tarde sirvió como embajadora en Noruega y Ceilán. El ascenso de Willis en el Servicio Exterior se debió a su competencia, trabajo duro y confianza en sí misma. También fue útil en su carrera el apoyo de mentores influyentes. Si bien no era una feminista militante, Willis abrió un camino para que otras diplomáticas mujeres lo siguieran. [38] [39] [40] [41]

En Estados Unidos, el 18 de diciembre de 2018, Nevada se convirtió en el primer estado en tener una mayoría femenina en su legislatura. Las mujeres ocupan nueve de los 21 escaños del Senado de Nevada y 23 de los 42 escaños de la Asamblea de Nevada. [42]

Una encuesta realizada en 2003 por Ciudades y Gobiernos Locales Unidos (CGLU), una red mundial que apoya a los gobiernos locales inclusivos, concluyó que la proporción media de mujeres en los consejos locales era del 15%. En los puestos de liderazgo, la proporción de mujeres era menor: por ejemplo, el 5% de los alcaldes de los municipios latinoamericanos son mujeres.

Se ha prestado cada vez más atención a la representación de las mujeres a nivel local. [43] La mayor parte de esta investigación se centra en los países en desarrollo. La descentralización gubernamental suele dar lugar a estructuras de gobierno local más abiertas a la participación de las mujeres, tanto como concejalas locales electas como usuarias de los servicios del gobierno local. [6]

Según un estudio comparativo sobre las mujeres en los gobiernos locales de Asia Oriental y el Pacífico, las mujeres han tenido más éxito en alcanzar puestos de toma de decisiones en los gobiernos locales que en el nivel nacional. [35] Los gobiernos locales tienden a ser más accesibles y tienen más puestos disponibles. Además, el papel de las mujeres en los gobiernos locales puede ser más aceptado porque se las considera una extensión de su participación en la comunidad.

La representación de las mujeres en los órganos deliberativos locales es, en promedio, del 35,5% en 141 países. Cabe destacar que tres países han logrado la paridad de género y otros 22 informan de una representación femenina superior al 40% en estos órganos. A pesar de estos avances, existen variaciones regionales sustanciales: la representación llega al 41% en Asia central y meridional , pero cae a sólo el 20% en Asia occidental y el norte de África . Esta disparidad pone de relieve los diversos desafíos y los distintos grados de progreso en la promoción de la participación de las mujeres en la gobernanza local a nivel mundial. [24]

En promedio, las democracias tienen el doble de mujeres en el gabinete que las autocracias. [44] En los sistemas autoritarios de gobierno, los gobernantes tienen incentivos relativamente débiles para nombrar mujeres en puestos de gabinete. Por el contrario, los gobernantes autoritarios tienen mayores incentivos para nombrar a individuos leales en el gabinete con el fin de aumentar sus posibilidades de supervivencia y disminuir el riesgo de golpes de Estado y revoluciones. [44] En las democracias, los líderes tienen incentivos para nombrar puestos de gabinete que les ayuden a ganar la reelección. [44]

Los politólogos dividen las causas de la escasa representación de las mujeres en puestos gubernamentales en dos categorías: la oferta y la demanda. La oferta se refiere a la ambición general de las mujeres de presentarse a un cargo y al acceso a recursos como la educación y el tiempo, mientras que la demanda se refiere al apoyo de la élite, el sesgo de los votantes y el sexismo institucional. [45] Las mujeres se enfrentan a numerosos obstáculos para lograr la representación en el gobierno. Los mayores desafíos que puede enfrentar una mujer en el gobierno ocurren durante la búsqueda de su puesto en el gobierno, a diferencia de cuando mantiene dicho puesto. Los estudios muestran que uno de los grandes desafíos es la financiación de una campaña. Los estudios también muestran que las mujeres que se postulan para un cargo político recaudan una cantidad similar de dinero en comparación con sus homólogos masculinos, sin embargo, sienten que necesitan trabajar más para lograrlo. [46] La violencia contra las mujeres en la política también disuade a las mujeres de presentarse a las elecciones.

Según una encuesta realizada a una muestra de 3.640 funcionarios municipales electos, las mujeres se enfrentan a adversidades en cuestiones como la financiación de una campaña porque los líderes de los partidos no las reclutan tanto como a los hombres. Hay dos factores que contribuyen a esta tendencia. En primer lugar, los líderes de los partidos tienden a reclutar candidatos que son similares a ellos. Como la mayoría de los líderes de los partidos son hombres, suelen considerar a los hombres como candidatos principales porque comparten más similitudes que la mayoría de las mujeres. El mismo concepto se aplica al analizar el segundo factor. El reclutamiento se realiza a través de redes como los titulares de cargos de nivel inferior o las empresas afiliadas. Como las mujeres están subrepresentadas en estas redes, según las estadísticas, es menos probable que sean reclutadas que los hombres. Debido a estos desafíos, las mujeres tienen que dedicar tiempo y esfuerzo consciente a construir un sistema de apoyo financiero, a diferencia de los hombres.

Algunos han sostenido que la política es una "matriz de dominación" diseñada por la raza, la clase, el género y la sexualidad. La interseccionalidad desempeña un papel importante en el trato que reciben las mujeres cuando se presentan a un cargo político y durante el tiempo que ocupan un cargo político. Un estudio realizado en Brasil encontró disparidades raciales que afectan aún más a las candidatas durante los procesos de reclutamiento y selección de candidatos. Las mujeres brasileñas afrodescendientes fueron las más desfavorecidas cuando se presentaron a un cargo político. [47]

La desigualdad de género dentro de las familias, la división inequitativa del trabajo dentro de los hogares y las actitudes culturales sobre los roles de género subyugan aún más a las mujeres y sirven para limitar su representación en la vida pública. [35] Además, a menudo se espera que la subrepresentación política de las mujeres en la democracia postsoviética que tiende a caracterizarse por altos niveles de corrupción política sea el resultado de las normas de género patriarcales y las preferencias de los votantes por colocar a los hombres en posiciones de liderazgo (Moser y Scheiner, 2012). [48] Las sociedades que son altamente patriarcales a menudo tienen estructuras de poder locales que dificultan que las mujeres combatan. [6] Por lo tanto, sus intereses a menudo no están representados o están subrepresentados.

Uno de los principales retos que las candidatas deben superar para obtener puestos políticos es el sesgo de los votantes. Según un estudio, las mujeres eran más propensas a afirmar que era más fácil para los hombres ser elegidos para cargos más altos. El estudio encontró que el 58% de los hombres y el 73% de las mujeres afirmaron que era más fácil para los hombres ser elegidos para cargos más altos. [49] En los EE. UU., según una encuesta, el 15% de los estadounidenses todavía cree que los hombres son mejores candidatos políticos que las mujeres. [50] Otra encuesta encontró que el 13% de las mujeres estadounidenses están muy de acuerdo o de acuerdo con que los hombres tienden a ser mejores candidatos políticos que las mujeres. [51]

En Estados Unidos, muchos votantes suponen que los hombres y las mujeres poseen rasgos que reflejan los estereotipos en los que creen. Muchos suponen que las candidatas son demasiado emocionales, más dispuestas a ceder o a hacer concesiones, menos cualificadas y más amables. Estas nociones suelen afectar negativamente a las mujeres, ya que la gente suele creer que muchas mujeres no deberían presentarse a las elecciones debido a estos estereotipos sobre los candidatos. [52]

Además, en el ámbito electoral se espera más de las mujeres que de los hombres. Un estudio en particular concluyó que las mujeres tienen estándares éticos y morales más altos que los hombres. [53] En este estudio, los datos de dieciocho países latinoamericanos mostraron que cuando se lanzaron ciertos escándalos o acusaciones de mala conducta contra una administración ejecutiva, la calificación de aprobación pública se redujo en mayor medida contra las ejecutivas que contra los ejecutivos, en promedio. Por lo tanto, el autor de este estudio sostiene que se espera que las mujeres se adhieran más estrictamente a los estándares éticos que los hombres, lo que sin duda implica un sesgo de género en la población votante.

Se han presentado numerosos argumentos en los que se afirma que el sistema de votación por mayoría simple es una desventaja para las posibilidades de que las mujeres ocupen cargos públicos. Andrew Reynolds expone uno de estos argumentos al afirmar: "Los sistemas de distritos uninominales con mayoría simple, ya sean del tipo angloamericano de mayoría simple (FPTP), el sistema australiano de voto alternativo por preferencia (AV) o el sistema francés de dos vueltas (TRS), se consideran particularmente desfavorables para las posibilidades de que las mujeres sean elegidas para un cargo público". [54] Andrew cree que los mejores sistemas son los sistemas de listas proporcionales . "En estos sistemas de alta proporcionalidad entre los escaños obtenidos y los votos emitidos, los partidos pequeños pueden ganar representación y los partidos tienen un incentivo para ampliar su atractivo electoral general haciendo que sus listas de candidatos sean lo más diversas posible". [54]

Incluso una vez elegidas, las mujeres tienden a ocupar ministerios o puestos similares menos valorados. [43] A veces se los describe como "industrias blandas" e incluyen la salud, la educación y el bienestar. Con mucha menor frecuencia, las mujeres tienen autoridad para tomar decisiones ejecutivas en dominios más poderosos o aquellos que se asocian con nociones tradicionales de masculinidad (como las finanzas y el ejército). Por lo general, cuanto más poderosa es la institución, menos probable es que se representen los intereses de las mujeres. Además, en las naciones más autocráticas, es menos probable que las mujeres tengan representados sus intereses. [6] Muchas mujeres alcanzan una posición política debido a lazos de parentesco, ya que tienen familiares varones que participan en la política. [43] Estas mujeres tienden a provenir de familias de mayores ingresos y estatus y, por lo tanto, pueden no estar tan centradas en los problemas que enfrentan las familias de menores ingresos. En los Estados Unidos, el extremo inferior de la escala profesional contiene una mayor proporción de mujeres, mientras que el nivel superior contiene una mayor proporción de hombres. Las investigaciones muestran que las mujeres están subrepresentadas en los puestos directivos de los organismos estatales, ya que representan solo el 18% del Congreso y el 15% de los puestos en los consejos de administración de las empresas. Cuando las mujeres consiguen algún nivel de representación es en los ámbitos de la salud, el bienestar social y el trabajo, y se las considera responsables de abordar cuestiones etiquetadas como femeninas. [55]

Un estudio de 2015 realizado por Kristin Kanthak y Jonathan Woon exploró por qué la participación de las mujeres en el gobierno no está al nivel que debería. Si bien hay múltiples factores que se analizan a lo largo de esta página, los autores sostienen que las mujeres tienden a ser más reacias a las elecciones que los hombres. Parece que la voluntad y la capacidad de las mujeres para participar en el gobierno es similar al nivel de ambición de los hombres, pero cuando hay una elección de por medio, su interés cae drásticamente. Las elecciones tienden a ser desordenadas, perjudiciales y costosas, lo que hace que muchas mujeres dejen de presentarse como candidatas. [56]

Además, el deseo de las mujeres de presentarse como candidatas se ve reforzado en gran medida por el estímulo de sus relaciones [57] . Mientras que la ambición de los hombres se deriva de la ambición personal, la educación, el matrimonio, etc., las mujeres reciben un estímulo abrumador de sus confidentes cercanos que apoyan sus esfuerzos en la esfera política. Esto puede ser un desafío, porque si ciertas mujeres no crecen en un entorno donde se aliente su participación en la arena política, esto reduce severamente cualquier deseo de involucrarse en ellas. En general, esto perjudica la representación femenina en el gobierno.

Además, las mujeres que se presentan a un cargo público suelen ser objeto de un escrutinio adicional e innecesario sobre su vida privada. Por ejemplo, las elecciones de moda de las mujeres políticamente activas suelen ser criticadas por los medios de comunicación. En estos "análisis", las mujeres rara vez obtienen la aprobación de los medios, que suelen decir que muestran demasiada piel o muy poca, o tal vez que parecen demasiado femeninas o demasiado masculinas. Sylvia Bashevkin también señala que sus vidas románticas suelen ser objeto de mucho interés para la población en general, tal vez más que su agenda política o sus posturas sobre cuestiones. [58] Señala que aquellas que "parecen ser sexualmente activas fuera de un matrimonio heterosexual monógamo se enfrentan a dificultades particulares, ya que tienden a ser retratadas como zorras molestas" [59] que están más interesadas en su vida romántica privada que en sus responsabilidades públicas. [58] Si están en una relación monógama y casada pero tienen hijos, entonces su idoneidad para el cargo se convierte en una cuestión de cómo se las arreglan para ser políticos y al mismo tiempo cuidar de sus hijos, algo sobre lo que a un político varón rara vez, o nunca, se le preguntaría.

Los deberes familiares y la formación de familias causan retrasos significativos en las carreras políticas de las mujeres aspirantes. [60] Mientras hacía campaña en las elecciones de la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos de 2018 en Nueva York , la candidata a las primarias demócratas Liuba Grechen Shirley utilizó fondos de campaña para pagar a una cuidadora para sus dos hijos pequeños. [1] La FEC dictaminó que los candidatos federales pueden usar fondos de campaña para pagar los costos de cuidado infantil que resultan del tiempo dedicado a postularse para un cargo. Grechen Shirley se convirtió en la primera mujer en la historia en recibir la aprobación para gastar fondos de campaña en cuidado infantil. [61]

Un estudio de 2017 concluyó que las candidatas republicanas obtienen peores resultados en las elecciones que los hombres republicanos y las mujeres demócratas. [62]

Un estudio de 2020 encontró que ser promovido al puesto de alcalde o parlamentario duplica la probabilidad de divorcio para las mujeres, pero no para los hombres. [63]

Se ha demostrado que las mujeres enfrentan más consecuencias cuando se enfrentan a escándalos. Un estudio realizado en 2019 por Catherine Reyes-Housholder utiliza a la expresidenta chilena Michelle Bachelet como caso de estudio sobre el efecto del índice de aprobación determinado por el género durante una controversia. El estudio descubrió que los índices de aprobación de los presidentes hombres no cambian con la corrupción percibida en el gobierno, pero los índices de aprobación de las mujeres sí. [64]

En Canadá, hay evidencia de que las mujeres políticas enfrentan el estigma de género por parte de los miembros masculinos de los partidos políticos a los que pertenecen, lo que puede socavar la capacidad de las mujeres para alcanzar o mantener roles de liderazgo. Pauline Marois , líder del Parti Québécois (PQ) y la oposición oficial de la Asamblea Nacional de Quebec , fue objeto de una reclamación de Claude Pinard, un " backbencher " del PQ, de que muchos quebequenses no apoyan a una mujer política: "Creo que una de sus serias desventajas es el hecho de que es mujer [...] Creo sinceramente que un buen segmento de la población no la apoyará porque es mujer". [65] Un estudio de 2000 que analizó los resultados de las elecciones de 1993 en Canadá encontró que entre "candidatos mujeres y hombres en situaciones similares", las mujeres en realidad tenían una pequeña ventaja de votos. El estudio mostró que ni la participación electoral ni los distritos urbanos/rurales eran factores que ayudaban o perjudicaban a una candidata, pero "la experiencia en cargos públicos en organizaciones no políticas hizo una modesta contribución a la ventaja electoral de las mujeres". [66]

Bruce M. Hicks, investigador de estudios electorales de la Universidad de Montreal, afirma que la evidencia muestra que las candidatas mujeres comienzan con una ventaja de hasta un 10 por ciento a ojos de los votantes, y que los votantes suelen asociarlas más favorablemente con temas como la atención de la salud y la educación. [65] La percepción del electorado de que las candidatas mujeres tienen más competencia en esferas tradicionalmente femeninas, como la educación y la atención de la salud, presenta la posibilidad de que los estereotipos de género puedan funcionar a favor de una candidata mujer, al menos entre el electorado. En política, sin embargo, Hicks señala que el sexismo no es nada nuevo:

(El problema de Marois) refleja lo que viene sucediendo desde hace algún tiempo: las mujeres que ocupan puestos de autoridad tienen problemas en cuanto a la forma en que gestionan la autoridad [...] El problema no son ellas, sino los hombres que están bajo su mando, que resienten recibir órdenes de mujeres fuertes. Y el diálogo sucio que se desarrolla tras bambalinas puede salir a la luz pública. [65]

En el propio Quebec, Don McPherson señaló que el propio Pinard ha tenido un mayor éxito electoral con Pauline Marois como líder del partido que con un líder masculino anterior, cuando Pinard no fue elegido en su distrito electoral. Desde el punto de vista demográfico, el distrito electoral de Pinard es rural, con "votantes relativamente mayores y menos instruidos". [67]

En Nigeria , no hay muchas mujeres en puestos de liderazgo. Actualmente, sólo siete de los 109 senadores y 22 de los 360 miembros de la Cámara de Representantes son mujeres. Hay varias explicaciones de por qué la participación de las mujeres en los partidos políticos es tan baja. Por ejemplo, las mujeres se ven disuadidas de presentarse a cargos públicos debido a los altos costos de la política. Los formularios de nominación y declaración de intereses que los partidos políticos exigen a los candidatos para presentarse a los escaños de su plataforma con frecuencia están fuera del alcance de las mujeres. Además, el precio de una campaña electoral es escandaloso. Y el acceso limitado a la educación también significa un acceso limitado a empleos bien remunerados. Las mujeres también tienen menos probabilidades de poder continuar el proceso de obtención de puestos de liderazgo debido a las responsabilidades laborales no remuneradas, los derechos de herencia desiguales y la discriminación abierta.

En un estudio que analizó la financiación de las campañas en Chile, los investigadores encontraron un sesgo de género significativo contra las mujeres en la financiación de las campañas. [46] En Chile, los partidos reciben dinero directamente del gobierno para asignarlo a sus diversos candidatos, y los candidatos están limitados a una cierta cantidad de dinero que pueden gastar en su campaña. El gobierno chileno instituyó múltiples políticas para tratar de aumentar la representación de género. Fijó una cuota del 40% en los escaños políticos y reembolsó a los partidos políticos cuando eligieron candidatas políticas en un esfuerzo por incentivarlas. Incluso en este caso "menos probable", los investigadores encontraron que en los candidatos sin experiencia previa en la candidatura, los hombres recaudarían más fondos que las mujeres.

Muchos de los desafíos que enfrentan las mujeres y que conducen a su escasa representación en los cargos políticos se ven amplificados por otros factores institucionales. La raza, en particular, desempeña un papel cada vez más importante en los desafíos que enfrentan las mujeres cuando deciden postularse para un cargo, se postulan activamente para un cargo y ejercen activamente un cargo. En un estudio que se centró en el tratamiento de las mujeres afrobrasileñas, los investigadores descubrieron que la institucionalización de los partidos aumenta la posibilidad de que los partidos elijan a las mujeres, sin embargo, el efecto es más atenuado para las afrobrasileñas. En Brasil, los afroamericanos ya enfrentan una importante brecha de recursos, como un ingreso promedio más bajo, niveles más bajos de legislación y tasas más altas de analfabetismo. Junto con estas barreras, las mujeres afrobrasileñas también enfrentan barreras para acceder al poder. Los investigadores descubrieron que las mujeres afrodescendientes recaudaban sistemáticamente menos dinero y obtenían menos votantes incluso cuando poseían las características tradicionales de una candidata política adecuada. [68]

Un estudio concluyó que la interseccionalidad juega un papel importante en la ambición de las mujeres y su decisión de postularse para un cargo político. [69] Encontraron que cuando se les decía a las mujeres las diferentes razones de la subrepresentación de las mujeres en los cargos políticos, las mujeres de diferentes razas respondían de manera muy diferente. Los investigadores afirmaron que "atribuir la falta de paridad de las mujeres a factores de demanda permite a las mujeres blancas y asiáticas "descartar" la posibilidad de que el fracaso se deba a sus propias habilidades, lo que aumenta la ambición política de las mujeres. Alternativamente, enmarcar la subrepresentación de las mujeres como debida a factores de oferta deprime la ambición política de las mujeres blancas y asiáticas posiblemente debido a la amenaza de los estereotipos. Las mujeres negras responden de manera opuesta, con una ambición política deprimida en escenarios de demanda, mientras que las latinas no se ven afectadas por estas narrativas". [69]

La participación de las mujeres en la política formal es menor que la de los hombres en todo el mundo. [70] El argumento planteado por las académicas Jacquetta Newman y Linda White es que la participación de las mujeres en el ámbito de la alta política es crucial si el objetivo es afectar la calidad de la política pública. Como tal, el concepto de representación especular apunta a lograr la paridad de género en los cargos públicos. En otras palabras, la representación especular dice que la proporción de mujeres en puestos de liderazgo debe coincidir con la proporción de mujeres en la población que gobiernan. La representación especular se basa en el supuesto de que los funcionarios electos de un género en particular probablemente apoyarían políticas que buscan beneficiar a los electores del mismo género.

Una crítica clave es que la representación especular supone que todos los miembros de un sexo en particular operan bajo la rúbrica de una identidad compartida, sin tomar en consideración otros factores como la edad, la educación, la cultura o el estatus socioeconómico. [71] Sin embargo, los defensores de la representación especular argumentan que las mujeres tienen una relación diferente con las instituciones gubernamentales y las políticas públicas que la de los hombres, y por lo tanto merecen una representación igualitaria solo en esta faceta. Esta característica se basa en la realidad histórica de que las mujeres, independientemente de su origen, han sido en gran medida excluidas de los puestos legislativos y de liderazgo influyentes. Como señala Sylvia Bashevkin, "la democracia representativa parece deteriorada, parcial e injusta cuando las mujeres, como mayoría de los ciudadanos, no se ven reflejadas en el liderazgo de su sistema político". [72] De hecho, la cuestión de la participación de las mujeres en la política es de tal importancia que las Naciones Unidas han identificado la igualdad de género en la representación (es decir, la representación especular) como un objetivo en la Convención sobre la Eliminación de Todas las Formas de Discriminación contra la Mujer (CEDAW) y la Plataforma de Acción de Beijing . [73] Además de buscar la igualdad, el objetivo de la representación especular es también reconocer la importancia de la participación de las mujeres en la política, lo que posteriormente legitima dicha participación.

Los resultados de los estudios que analizaron la importancia de la representación de las mujeres en los resultados de las políticas públicas han sido dispares. Aunque las mujeres en los Estados Unidos tienen más probabilidades de identificarse como feministas, [74] un estudio de 2014 que analizó a los Estados Unidos no encontró "ningún efecto del género del alcalde en los resultados de las políticas". [75] Un estudio de 2012 encontró evidencia mixta de que la proporción de concejalas en Suecia afectó las condiciones de las ciudadanas, como el ingreso de las mujeres, el desempleo, la salud y la licencia parental. [76] Un estudio de 2015 en Suecia dijo que: "Los hallazgos muestran que las legisladoras defienden los intereses feministas más que sus colegas masculinos, pero que solo responden marginalmente a las preferencias electorales de las mujeres". [77] Un estudio de 2016 que analizó a los políticos africanos encontró que "las diferencias de género en las prioridades políticas [son] bastante pequeñas en promedio, varían entre los dominios de políticas y los países". [78]

Según la OCDE , la mayor presencia de mujeres en los gabinetes de ministros está asociada con un aumento del gasto en salud pública en muchos países. [79]

La representación especular surge de las barreras que suelen enfrentar las candidatas políticas, entre ellas los estereotipos de género, la socialización política, la falta de preparación para la actividad política y el equilibrio entre el trabajo y la familia. En los medios de comunicación, a menudo se les pregunta a las mujeres cómo equilibrarían las responsabilidades de un cargo electo con las de sus familias, algo que nunca se les pregunta a los hombres. [80]

Estereotipos sexuales: Los estereotipos sexuales presuponen que los rasgos masculinos y femeninos están entrelazados con el liderazgo. Por lo tanto, el sesgo contra las mujeres surge de la percepción de que la feminidad produce inherentemente un liderazgo débil. [81] Debido a la naturaleza agresiva y competitiva de la política, muchos insisten en que la participación en cargos electivos requiere rasgos masculinos. [82] Los estereotipos sexuales están lejos de ser una narrativa histórica. La presión recae sobre las candidatas (y no sobre los candidatos) para que mejoren sus rasgos masculinos con el fin de obtener el apoyo de los votantes que se identifican con los roles de género socialmente construidos. Aparte de esto, los estudios de la American University en 2011 revelan que las mujeres tienen un 60% menos de probabilidades que los hombres de creer que no están calificadas para asumir responsabilidades políticas. [83] Por lo tanto, el patriarcado en la política es responsable de la menor participación de las mujeres.

Violencia sexual y física : En Kenia, una activista de los derechos de la mujer llamada Asha Ali fue amenazada y golpeada por tres hombres por presentarse como candidata frente a sus hijos y su anciana madre. [84] Una encuesta de 2010 de ochocientos posibles votantes estadounidenses encontró que incluso un lenguaje sexista muy leve tenía un impacto en su probabilidad de votar por una mujer (Krook, 2017). [84] Incluso a principios de 2016, una niña de 14 años fue secuestrada de su cama a altas horas de la noche y violada como venganza por la victoria de su madre en las elecciones locales en la India, lo que es un ejemplo de violencia sexual. [84] Toda esta evidencia sugiere que las mujeres enfrentan muchos desafíos en un entorno político donde los hombres intentan reprimir a las mujeres cada vez que intentan alzar sus voces en la política para hacer un cambio positivo para el empoderamiento de las mujeres.

Falta de apoyo de los medios de comunicación: El estudio cualitativo y cuantitativo revela que los medios reflejan y fortalecen una sociedad dominada por los hombres. [85] Las mujeres que aparecen en las noticias suelen ser por malas noticias y por razones vulgares o erróneas, como su aspecto, su vida personal, su ropa y su carácter. [85] A los medios les gusta dar más actualizaciones sobre todos estos ejemplos anteriores en lugar de su papel político real y sus logros . [86]

Socialización política: La socialización política es la idea de que, durante la infancia, las personas son adoctrinadas en normas políticas construidas socialmente. En el caso de la representación de las mujeres en el gobierno, dice que los estereotipos sexuales comienzan a una edad temprana y afectan la disposición del público sobre qué géneros son aptos para los cargos públicos. Los agentes de socialización pueden incluir la familia, la escuela, la educación superior, los medios de comunicación y la religión. [87] Cada uno de estos agentes juega un papel fundamental ya sea al fomentar el deseo de entrar en la política o al disuadir a alguien de hacerlo.

En general, las niñas tienden a ver la política como un “dominio masculino”. [88] Newman y White sugieren que las mujeres que se postulan para un cargo político han sido “socializadas hacia un interés y una vida en la política” y que “muchas políticas mujeres informan haber nacido en familias políticas con normas débiles sobre los roles de género”. [89]

Las mujeres que se presentan al Senado de Estados Unidos suelen estar subrepresentadas en la cobertura informativa. La forma en que se presenta a los candidatos masculinos y femeninos en los medios de comunicación tiene un efecto en la forma en que las candidatas son elegidas para un cargo público. Las candidatas reciben un trato diferente en los medios de comunicación que sus homólogos masculinos en las elecciones al Senado de Estados Unidos. Las mujeres reciben menos cobertura informativa y la cobertura que reciben se concentra más en su viabilidad y menos en sus posiciones sobre los temas, lo que hace que las candidatas sean pasadas por alto y subestimadas durante las elecciones, lo que es un obstáculo para las mujeres que se presentan al Senado de Estados Unidos. [90]

Falta de preparación para la actividad política: Una consecuencia de la socialización política es que determina la inclinación de las mujeres a seguir carreras que pueden ser compatibles con la política formal. Carreras en derecho, negocios, educación y gobierno, profesiones en las que las mujeres son minoría, son ocupaciones comunes para aquellas que luego deciden ingresar a un cargo público. [89]

Equilibrar el trabajo y la familia: el equilibrio entre el trabajo y la vida familiar es invariablemente más difícil para las mujeres, porque la sociedad generalmente espera que sean las principales cuidadoras de los niños y las encargadas del hogar. Debido a estas exigencias, se supone que las mujeres optarían por posponer sus aspiraciones políticas hasta que sus hijos sean mayores. Además, el deseo de una mujer de hacer carrera en la política, junto con la medida en que la encuestada sienta que sus deberes familiares podrían inhibir su capacidad para ser una funcionaria electa. [91] Las investigaciones han demostrado que las nuevas políticas en Canadá y los EE. UU. son mayores que sus homólogos masculinos. [92] Por el contrario, una mujer puede verse presionada a no tener hijos para buscar un cargo político.

Las barreras institucionales también pueden representar un obstáculo para equilibrar la carrera política y la familia. Por ejemplo, en Canadá, los miembros del Parlamento no contribuyen al Seguro de Empleo; por lo tanto, no tienen derecho a prestaciones por paternidad. [93] Esta falta de licencia parental sería sin duda una razón para que las mujeres retrasen su candidatura a un cargo electoral. Además, la movilidad desempeña un papel crucial en la dinámica trabajo-familia. Los funcionarios electos suelen tener que viajar largas distancias desde y hacia sus respectivas capitales, lo que puede ser un factor disuasorio para las mujeres que aspiran a un cargo político.

A nivel mundial, han existido cuatro vías generales que han llevado a las mujeres a ocupar cargos políticos: [94]

En 2017, se realizó un estudio utilizando una muestra de países de todo el mundo. De este, de las 77 mujeres ejecutivas de los países estudiados, 22 eran provisionales [95] De estos tipos, sin embargo, la familia política representó más de una cuarta parte de las ejecutivas. [95] Se encontró que este era principalmente el caso en Asia y América Latina. En América Latina, el 75% de los ejecutivos no provisionales tenían vínculos de sangre con un expresidente o figura política. [96] El 78% de las ejecutivas asiáticas comparten este rasgo.

Se encontró que las mujeres a menudo lideran o participan en movimientos revolucionarios o de democratización, sin embargo esto rara vez conduce a un ascenso político. [97] Se encontró que los lazos familiares son un determinante más importante del ascenso político que cualquier tipo de mérito. [98]

El modelo de reclutamiento político es un término acuñado por politólogos que estudiaron por qué las mujeres no ocupan cargos políticos en la misma proporción que los hombres. El modelo de reclutamiento político clasifica los pasos entre un ciudadano y un político, y muchos politólogos lo utilizan para estudiar dónde las mujeres están perdiendo la oportunidad y las posibilidades de ocupar un cargo electo. El modelo de reclutamiento político tiene cuatro partes: elegibles, aspirantes, candidatos y electos. Al estudiar las vías de participación política, los politólogos se centran en dónde en esta vía las mujeres tienden a "escaparse". [45]

.jpg/440px-Prime_Minister_Sanna_Marin_meeting_with_Estonian_Prime_Minister_Kaja_Kallas_in_Helsinki_19.2.2021_(50958763761).jpg)

Las Naciones Unidas han identificado seis vías para fortalecer la participación femenina en la política y el gobierno, a saber: la igualdad de oportunidades educativas, la fijación de cuotas para la participación femenina en los órganos de gobierno, la reforma legislativa para prestar más atención a las cuestiones que afectan a las mujeres y los niños, la financiación de presupuestos con perspectiva de género que tengan en cuenta por igual las necesidades de hombres y mujeres, el aumento de la presencia de estadísticas desglosadas por sexo en las investigaciones y los datos nacionales, y el fomento de la presencia y la capacidad de acción de los movimientos de base en favor del empoderamiento de la mujer . [35]

La primera organización gubernamental formada con el objetivo de la igualdad de las mujeres fue el Zhenotdel , en la Rusia soviética en la década de 1920.

Las mujeres con educación formal (en cualquier nivel) tienen más probabilidades de retrasar el matrimonio y el nacimiento de hijos, estar mejor informadas sobre la nutrición de los lactantes y los niños y garantizar la inmunización infantil. Los hijos de madres con educación formal están mejor alimentados y tienen mayores tasas de supervivencia. [35] La educación es una herramienta vital para que cualquier persona de la sociedad mejore su carrera profesional, y la igualdad de oportunidades educativas para niños y niñas puede adoptar la forma de varias iniciativas:

Mark P. Jones, en referencia al trabajo de Norris sobre el reclutamiento legislativo , afirma que: "A diferencia de otros factores que se han identificado como influyentes en el nivel de representación legislativa de las mujeres, como la cultura política y el nivel de desarrollo económico de un país, las reglas institucionales son relativamente fáciles de cambiar". [102]

En un artículo sobre la exclusión de las mujeres de la política en el sur de África, Amanda Gouws dijo: "Los mayores obstáculos que deben superar las mujeres todavía están en el nivel local, donde tanto los hombres como las mujeres suelen ser reclutados en las comunidades y tienen habilidades políticas limitadas". [103] El nivel de educación en estos gobiernos locales o, en realidad, de las personas que ocupan esos puestos de poder, son deficientes.

Un ejemplo de los obstáculos que enfrentan las mujeres para recibir una buena educación proviene de Beijing. "La mayoría de las mujeres que asistieron a los foros de ONG que acompañan a las conferencias de la ONU , que son para delegaciones gubernamentales (aunque cada vez más gobiernos incluyen activistas y miembros de ONG entre sus delegados oficiales), eran mujeres educadas de clase media de ONG internacionales , donantes, académicas y activistas". [104] Lydia Kompe , una conocida activista sudafricana, era una de estas mujeres rurales. Señaló que se sentía abrumada y completamente desempoderada. Al principio, no creía que pudiera terminar su mandato debido a su falta de educación. [103] Manisha Desai explica que: "Existe una desigualdad simplemente en torno al hecho de que el sistema de la ONU y sus ubicaciones dicen mucho sobre el enfoque actual de esos sistemas, tales puestos en los EE. UU. y Europa Occidental permiten un acceso más fácil a esas mujeres en el área. [104] También es importante señalar que las instituciones afectan la propensión cultural a elegir candidatas mujeres de diferentes maneras en diferentes partes del mundo". [54]

El estudio de la historia de la representación de las mujeres ha sido una importante contribución para ayudar a los académicos a considerar estos conceptos. Andrew Reynolds afirma: "la experiencia histórica a menudo conduce a un avance de género, y la liberalización política permite a las mujeres movilizarse dentro de la esfera pública". [54] Sostiene que veremos un mayor número de mujeres en puestos de alto nivel en las democracias establecidas que en las democracias en desarrollo, y "cuanto más iliberal sea un estado, menos mujeres habrá en puestos de poder". [54] A medida que los países abren los sistemas educativos a las mujeres y más mujeres participan en campos históricamente dominados por los hombres, es posible ver un cambio en las opiniones políticas sobre las mujeres en el gobierno.

Las cuotas son requisitos explícitos sobre el número de mujeres en puestos políticos. [101] "Las cuotas de género para la elección de legisladores han sido utilizadas desde finales de la década de 1970 por unos pocos partidos políticos (a través de la carta del partido) en un pequeño número de democracias industriales avanzadas; ejemplos de ello serían Alemania y Noruega ". [102] Andrew Reynolds dice que hay "una práctica cada vez mayor en las legislaturas para que el estado, o los propios partidos, utilicen mecanismos de cuotas formales o informales para promover a las mujeres como candidatas y diputadas ". [54] Las estadísticas que rodean los sistemas de cuotas han sido examinadas a fondo por la academia. El Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos decidió su primer caso de cuotas femeninas en 2019 y, a diciembre de 2019 [update], había un caso de cuotas masculinas pendiente en el tribunal. [105] En Zevnik y otros contra Eslovenia, el tribunal expresó su firme apoyo a las cuotas de género como herramienta para aumentar la participación de las mujeres en la política. [106] Las cuotas de género son una forma popular de feminismo estatal .

Los tipos de cuotas incluyen:

Las cuotas pueden utilizarse durante diferentes etapas del proceso de nominación/selección política para abordar diferentes coyunturas en las que las mujeres pueden estar inherentemente desfavorecidas: [101]

El uso de cuotas puede tener efectos marcados en la representación femenina en el gobierno. Se estima que unas cuotas más estrictas aumentan el número de mujeres elegidas para el parlamento unas tres veces en comparación con unas cuotas más débiles. [112] En 1995, Ruanda ocupaba el puesto 24 en cuanto a representación femenina, y saltó al primer puesto en 2003 tras la introducción de las cuotas. [113] Se pueden observar efectos similares en Argentina, Irak, Burundi, Mozambique y Sudáfrica, por ejemplo. [101] De los 20 países que ocupan los primeros puestos en cuanto a representación femenina en el gobierno, 17 de ellos utilizan algún tipo de sistema de cuotas para garantizar la inclusión femenina. Aunque dicha inclusión se instituye principalmente a nivel nacional, en la India se han hecho esfuerzos para abordar la inclusión femenina a nivel subnacional, mediante cuotas para los puestos parlamentarios. [114]

El hecho de que las cuotas hayan modificado drásticamente el número de representantes femeninas en el poder político ha dado lugar a un panorama más amplio. Aunque los países tienen derecho a regular sus propias leyes, el sistema de cuotas ayuda a explicar las instituciones sociales y culturales y su comprensión y visión general de las mujeres en general. "A primera vista, estos cambios parecen coincidir con la adopción de cuotas de género para las candidaturas en todo el mundo, ya que las cuotas han aparecido en países de todas las principales regiones del mundo con una amplia gama de características institucionales, sociales, económicas y culturales". [115]

Las cuotas han sido muy útiles para permitir que las mujeres obtengan apoyo y oportunidades cuando intentan alcanzar puestos de poder, pero muchos ven esto como una mala acción. Drude Dahlerup y Lenita Freidenvall argumentan esto en su artículo "Cuotas como una 'vía rápida' hacia la representación igualitaria de las mujeres" al afirmar: "Desde una perspectiva liberal, las cuotas como un derecho de grupo específico entran en conflicto con el principio de igualdad de oportunidades para todos. Favorecer explícitamente a ciertos grupos de ciudadanos, es decir, las mujeres, significa que no todos los ciudadanos (hombres) tienen la misma oportunidad de lograr una carrera política". [116] Dahlerup y Freidenvall afirman que, si bien las cuotas crean un desequilibrio teórico en las oportunidades para los hombres y que necesariamente rompen el concepto de "noción liberal clásica de igualdad", [116] las cuotas son casi necesarias para llevar la relación de las mujeres en la política a un estado superior, ya sea a través de la igualdad de oportunidades o simplemente de la igualdad de resultados. [116] "De acuerdo con esta interpretación de la subrepresentación de las mujeres, se necesitan cuotas obligatorias para el reclutamiento y la elección de candidatas, que posiblemente también incluyan disposiciones sobre límites de tiempo". [116]

La introducción de cuotas de género en el proceso electoral ha generado controversia entre los políticos, lo que ha dado lugar a una resistencia a la aceptación de las cuotas en el ámbito político. [117] La movilización de las mujeres en la política se ha visto obstaculizada por la preservación de la supervivencia política masculina y para evitar la interferencia política con el poder y la dominación masculinos. [117] Además, la aplicación de cuotas de género ha provocado que la población de candidatos masculinos disminuya para que sus contrapartes femeninas puedan participar, y esto se conoce comúnmente como la "suma negativa", y puede dar lugar a que se rechace a un hombre más calificado para permitir que participe una política femenina. [117] Sin embargo, esta noción de "más calificado" sigue siendo poco clara y se utiliza con demasiada frecuencia como una herramienta opresiva para mantener el statu quo, es decir, excluyendo a las mujeres. De hecho, solo podemos utilizar indicadores indirectos para predecir los resultados futuros. Por ejemplo, las investigaciones han demostrado desde hace mucho tiempo que el uso de las puntuaciones del SAT en los EE. UU. para la admisión a la universidad favorece a las clases privilegiadas que pueden recibir capacitación adicional antes del examen, mientras que las clases menos favorecidas podrían haber tenido tanto o incluso más éxito una vez en la universidad. El problema de los representantes es aún peor en el caso de las mujeres, ya que esto se suma al sesgo cognitivo de la homofilia , que lleva a los hombres que ya están en el poder a favorecer a otros hombres para que trabajen con ellos. Además, en el caso de Argentina, que actualmente está obligado a un partido con un 30% de mujeres en cada nivel de gobierno, se introdujo la "cuota de mujeres"; mujeres que tenían menos experiencia y solo fueron elegidas debido al requisito legal de las cuotas. [118] La introducción de la "cuota de mujeres" ha desencadenado lo que los politólogos denominan un "efecto mandato", donde las mujeres de la cuota se sienten obligadas a representar únicamente los intereses del público femenino. [118] Además, con el fin de preservar la supervivencia política masculina, se han utilizado "técnicas de dominación" para excluir y deslegitimar la representación femenina en la política, y esto se puede ver en el caso de Argentina, donde se necesitaron varias elecciones para obtener el 35% de representantes femeninas. [118] Con el aumento de la representación femenina en Argentina, cuestiones que antes rara vez se discutían se volvieron primordiales en los debates, como "leyes penales, leyes de agresión sexual y leyes sobre licencia de maternidad y embarazo... educación sexual, [y] anticoncepción de emergencia".

La representación sustantiva contiene dos partes distintas: tanto el proceso como el resultado de tener mujeres políticas. [118] La representación sustantiva basada en el proceso se ocupa de la perspectiva de género, los temas que las representantes femeninas discuten en los debates políticos y el impacto que tienen en la creación de proyectos de ley. [118] Asimismo, este proceso también incluye la creación de redes entre mujeres en el gobierno y organizaciones femeninas. [118] La representación sustantiva por resultado se relaciona con el éxito de la aprobación de leyes que permitan la igualdad de género tanto en asuntos públicos como privados. [118] Además, la representación sustantiva como proceso no siempre da como resultado una representación sustantiva por resultado; la implementación de cuotas de género y la representación femenina no instiga directamente una afluencia en la legislación. [118]

La teoría de la masa crítica tiene correlaciones tanto con la representación sustantiva como proceso como con la representación sustantiva como resultado. La teoría de la masa crítica sugiere que una vez que se haya alcanzado un cierto porcentaje de representantes mujeres, las legisladoras podrán crear y hacer posibles políticas transformadoras, y esto tiene el potencial de ejercer presión sobre las mujeres que participan en el programa de cuotas para que actúen en nombre de todas las mujeres. [118] Alcanzar una masa crítica elimina la presión de mantener el status quo, al que las minorías se ven obligadas a adaptarse para evitar que la mayoría las etiquete de forasteras. [119] Una crítica primordial a la teoría de la masa crítica es su atención a los números y la comprensión de que las mujeres que participan en el programa de cuotas deben representar a las mujeres colectivamente. [118] Además, la representación de las mujeres como un grupo colectivo sigue siendo controvertida, ya que "si es una madre blanca, heterosexual y de clase media, no puede hablar en nombre de las mujeres afroamericanas, o de las mujeres pobres, o de las mujeres lesbianas sobre la base de su propia experiencia, del mismo modo que los hombres no pueden hablar en nombre de las mujeres simplemente sobre la base de la suya". [118]

Un estudio transnacional encontró que la implementación de cuotas electorales de género, que aumentó sustancialmente la representación de las mujeres en el parlamento, condujo a mayores gastos gubernamentales en salud pública y disminuciones relativas en el gasto militar, en consonancia con la presunción de que las mujeres favorecen lo primero mientras que los hombres favorecen lo segundo en los países incluidos en el estudio. [120] Sin embargo, si bien un aumento numérico en las legisladoras puede empujar la política en la dirección de los intereses de las mujeres, las legisladoras pueden ser encasilladas en la especialización en legislación sobre temas de mujeres, como encuentra un estudio para legisladores en Argentina, Colombia y Costa Rica. [121] En Argentina, otro estudio encuentra que la introducción de cuotas de género aumentó la frecuencia total de proyectos de ley presentados sobre temas de mujeres, mientras que redujo la frecuencia con la que los hombres presentaron proyectos de ley en esta área legislativa; esta evidencia lleva a los autores a concluir que la introducción de legisladoras puede disminuir el incentivo de los legisladores hombres para introducir políticas en línea con los intereses de las mujeres. [122]

En numerosas ocasiones, la legislación igualitaria ha beneficiado a la progresión general de la igualdad de la mujer a escala mundial. Aunque las mujeres han entrado en la legislación, no se está estableciendo la representación general en los niveles superiores del gobierno. "Si se observan los puestos ministeriales desglosados por asignación de cartera, se observa una tendencia mundial a colocar a las mujeres en los puestos ministeriales socioculturales más suaves en lugar de en los puestos más difíciles y políticamente más prestigiosos de planificación económica, seguridad nacional y asuntos exteriores, que a menudo se consideran trampolines hacia el liderazgo nacional". [54]

Las agendas legislativas, algunas impulsadas por figuras políticas femeninas, pueden centrarse en varias cuestiones clave para abordar las disparidades de género actuales:

Sex-responsive budgets address the needs and interests of different individuals and social groups, maintaining awareness of sexual equality issues within the formation of policies and budgets. Such budgets are not necessarily a 50–50 male-female split, but accurately reflect the needs of each sex (such as increased allocation for women's reproductive health).[126] Benefits of gender-responsive budgets include:

A sex-responsive budget may also work to address issues of unpaid care work and caring labor gaps.[126]

In the last decades several countries have tied state funding of political parties to compliance with gender quotas, known as gender-targeted public funding.[127] The idea is to use state funding to incentivize political parties to increase gender diversity on their ballot by either giving a fine or give extra resources to parties depending on whether they satisfy a fixed gender balance goal.[128] A 2021 study published in American Political Science Review found that this type of state-driven gendered electoral financing is likely to lead to success when combined with either proportional representation of a 15% minimum of women MPs.[129]

Current research which uses sex-aggregated statistics may underplay or minimize the quantitative presentation of issues such as maternal mortality, violence against women, and girls' school attendance.[35] Sex-disaggregated statistics are lacking in the assessment of maternal mortality rates, for example. Prior to UNICEF and UNIFEM efforts to gather more accurate and comprehensive data, 62 countries had no recent national data available regarding maternal mortality rates.[130] Only 38 countries have sex-disaggregated statistics available to report frequency of violence against women.[130] 41 countries collect sex-disaggregated data on school attendance, while 52 countries assess sex-disaggregated wage statistics.[130]

Though the representation has become a much larger picture, it is important to notice the inclination of political activity emphasizing women over the years in different countries. "Although women's representation in Latin America, Africa, and the West progressed slowly until 1995, in the most recent decade, these regions show substantial growth, doubling their previous percentage".[32]

Researching politics on a global scale does not just reinvent ideas of politics, especially towards women, but brings about numerous concepts. Sheri Kunovich and Pamela Paxton's research method, for example, took a different path by studying "cross-national" implications to politics, taking numerous countries into consideration. This approach helps identify research beforehand that could be helpful in figuring out commodities within countries and bringing about those important factors when considering the overall representation of women. "At the same time, we include information about the inclusion of women in the political parties of each country".[33] Research within gender and politics has taken a major step towards a better understanding of what needs to be better studied. Mona Lena Krook states: "These kinds of studies help establish that generalizing countries together is far too limiting to the overall case that we see across countries and that we can take the information we gain from these studies that look at countries separately and pose new theories as to why countries have the concepts they do; this helps open new reasons and thus confirms that studies need to be performed over a much larger group of factors."[131] Authors and researchers such as Mala Htun and Laurel Weldon also state that single comparisons of established and developed countries is simply not enough but is also surprisingly hurtful to the progress of this research, they argue that focusing on a specific country "tends to duplicate rather than interrogate" the overall accusations and concepts we understand when comparing political fields.[132] They continue by explaining that comparative politics has not established sex equality as a major topic of discussion among countries.[132] This research challenges the current standings as to what needs to be the major focus in order to understand gender in politics.

A 2018 study in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy found that for German local elections "female council candidates advance more from their initial list rank when the mayor is female. This effect spreads to neighboring municipalities and leads to a rising share of female council members."[133]

Women's informal collectives are crucial to improving the standard of living for women worldwide. Collectives can address such issues as nutrition, education, shelter, food distribution, and generally improved standard of living.[134] Empowering such collectives can increase their reach to the women most in need of support and empowerment. Though women's movements have a very successful outcome with the emphasis on gaining equality towards women, other movements are taking different approaches to the issue. Women in certain countries, instead of approaching the demands as representation of women as "a particular interest group", have approached the issue on the basis of the "universality of sex differences and the relation to the nation".[132] Htun and Weldon also bring up the point of democracy and its effects on the level of equality it brings. In their article, they explain that a democratic country is more likely to listen to "autonomous organizing" within the government. Women's movements would benefit from this the most or has had great influence and impact because of democracy, though it can become a very complex system.[132] When it comes to local government issues, political standings for women are not necessarily looked upon as a major issue. "Even civil society organizations left women's issues off the agenda. At this level, traditional leaders also have a vested interest that generally opposes women's interests".[103] Theorists believe that having a setback in government policies would be seen as catastrophic to the overall progress of women in government. Amanda Gouws says that "The instability of democratic or nominally democratic regimes makes women's political gains very vulnerable because these gains can be easily rolled back when regimes change. The failure to make the private sphere part of political contestation diminishes the power of formal democratic rights and limits solutions to gender inequality".[103]

Women are largely underrepresented in government bodies for a variety of reasons, with the leading theory being a gap in political ambition between men and women. In addition, women are encouraged to run for office less than men and will usually be at a disadvantage if they choose to run due to negative stereotypes and gender role expectations. This makes women more election averse then men due to being less likely to take risks. These factors prevent many women from attempting to enter the political field.[135] More demographics often bring different experiences, attitudes and resources that greatly affect legislation, party agendas, and constituency service. A study by Bonneau and Kanthak focused on responses to Hillary Clinton campaign videos found that women supporters who witness her run for presidency were more likely to want to run themselves. This is not true for all women, as non-supporters were less likely to say they would run for office after witnessing the videos. Feelings about a candidate have a massive effect on whether or not a person will run themselves after seeing another campaign.[136]

Since women have been marginalized in politics throughout history, the symbolic effect of women entering politics has a significant impact on whether women feel represented and heard in political issues. Studies find that the more women in state legislature, the more likely women are to run for office than in a male dominated government system. The increased representation in government roles also incentivizes political engagement and activity, whether that means voting or campaigning.[137]

There are many branches of the government and organizations dedicated to improving representation for women, such as the Office of Public Engagement and Intergovernmental Affairs, a United States government office specifically focused on representation in the White House. Another example is the White House Council of Women and Girls, another United States governmental organization. Offices for representation will usually have a target demographic to protect the representation of. There are other offices dedicated to certain issues regarding those demographics, like the protection of women against sexual assault. It should be mentioned that intersectionality is common, as gender, race and sexuality can overlap. These characteristics often reinforce each other or cause strife within a community.[138]

Affirmative action both corrects existing unfair treatment and gives women equal opportunity in the future.[139] Moreover, the impact that gender representation can have on politics cannot be emphasized enough. In their noteworthy paper on examining the effects of female leadership in the times of crisis, Bruce et al. show that women as mayors in Brazilian municipalities had a negative, sizable and significant impact on the number of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations per one hundred thousand inhabitants.[140] It is interesting to note that the effect of women in power in Brazil was stronger in pro-Bolsonaro strongholds, who became infamous for his beliefs of not wearing a mask and being skeptical of vaccines.[140]

In addition to the points raised above, Supriya Garikipati and Uma Kambhampati conduct an analysis to determine if there is any significant difference between COVID-19 pandemic being handled by women as compared to men. Their findings show that COVID-death related outcomes are better in countries which are led by women across all the 194 nations.[141] They even find that testing rates per hundred thousand people are significantly higher in countries led by women, and still report fewer cases than countries led by men. Women were noted to have reacted quicker to enacting lockdowns and ensuring proper communication to the public once the pandemic hit. In the conclusion of the study, it was found that overall women-led countries handled the COVID-19 outbreak better, especially in countries with more affordable healthcare such as Germany.[142]