La Tierra Media es el escenario de gran parte de la fantasía del escritor inglés J. R. R. Tolkien . El término es equivalente al Miðgarðr de la mitología nórdica y al Middangeard en las obras en inglés antiguo , incluido Beowulf . La Tierra Media es la oecumene (es decir, el mundo habitado por humanos, o el continente central de la Tierra ) en el pasado mitológico imaginado de Tolkien . Las obras más leídas de Tolkien, El hobbit y El señor de los anillos , están ambientadas íntegramente en la Tierra Media. "Tierra Media" también se ha convertido en un término abreviado para el legendarium de Tolkien , su gran cuerpo de escritos de fantasía, y para la totalidad de su mundo ficticio.

La Tierra Media es el continente principal de la Tierra (Arda) en un período imaginario del pasado, que termina con la Tercera Edad de Tolkien , hace unos 6.000 años. [T 1] Los relatos de Tolkien sobre la Tierra Media se centran principalmente en el noroeste del continente. Esta región sugiere Europa, el noroeste del Viejo Mundo , con los alrededores de la Comarca que recuerdan a Inglaterra , pero, más específicamente, las Midlands Occidentales , con la ciudad en su centro, Hobbiton , en la misma latitud que Oxford .

La Tierra Media de Tolkien está poblada no sólo por hombres , sino también por elfos , enanos , ents y hobbits , y por monstruos como dragones, trolls y orcos . A lo largo de la historia imaginada, los pueblos distintos de los hombres disminuyen, se van o desaparecen, hasta que, después del período descrito en los libros, sólo quedan hombres en el planeta.

Las historias de Tolkien narran la lucha por controlar el mundo (llamado Arda ) y el continente de la Tierra Media entre, por un lado, los angélicos Valar , los Elfos y sus aliados entre los Hombres ; y, por el otro, el demoníaco Melkor o Morgoth (un Vala caído en el mal), sus seguidores y sus súbditos, en su mayoría Orcos , Dragones y Hombres esclavizados. [T 2] En épocas posteriores, tras la derrota de Morgoth y su expulsión de Arda, su lugar es ocupado por su lugarteniente Sauron , un Maia . [T 3]

Los Valar se retiraron de la participación directa en los asuntos de la Tierra Media después de la derrota de Morgoth, pero en años posteriores enviaron a los magos o Istari para ayudar en la lucha contra Sauron. Los magos más importantes fueron Gandalf el Gris y Saruman el Blanco . Gandalf se mantuvo fiel a su misión y resultó crucial en la lucha contra Sauron. Saruman, sin embargo, se corrompió y trató de establecerse como rival de Sauron por el poder absoluto en la Tierra Media. Otras razas involucradas en la lucha contra el mal fueron los enanos , los ents y, más famosamente, los hobbits . Las primeras etapas del conflicto están narradas en El Silmarillion , mientras que las etapas finales de la lucha para derrotar a Sauron se cuentan en El hobbit y en El Señor de los Anillos . [T 3]

El conflicto por la posesión y el control de objetos preciosos o mágicos es un tema recurrente en las historias. La Primera Edad está dominada por la búsqueda condenada al fracaso del elfo Fëanor y la mayor parte de su clan Noldorin para recuperar tres joyas preciosas llamadas los Silmarils que Morgoth les robó (de ahí el título El Silmarillion ). La Segunda y la Tercera Edad están dominadas por la forja de los Anillos de Poder y el destino del Anillo Único forjado por Sauron, que otorga a su portador el poder de controlar o influir en aquellos que llevan los otros Anillos de Poder. [T 3]

En la antigua mitología germánica , el mundo de los hombres es conocido por varios nombres. El término inglés antiguo middangeard desciende de una palabra germánica anterior y por lo tanto tiene cognados como el término nórdico antiguo Miðgarðr de la mitología nórdica , transliterado al inglés moderno como Midgard . El significado original del segundo elemento, del protogermánico gardaz , era "recinto", cognado con el término inglés "yard"; middangeard fue asimilado por la etimología popular a "Tierra Media". [T 4] [2] La Tierra Media estaba en el centro de nueve mundos en la mitología nórdica, y de tres mundos (con el cielo arriba, el infierno abajo) en algunas versiones cristianas posteriores . [1]

El primer encuentro de Tolkien con el término middangeard , como afirmó en una carta, fue en un fragmento de inglés antiguo que estudió entre 1913 y 1914: [T 5]

Éala éarendel engla beorhtast / ofer middangeard monnum enviado.

Salve Eärendel, el más brillante de los ángeles / sobre la Tierra Media enviado a los hombres.

Este es del poema Crist 1 de Cynewulf . El nombre Éarendel fue la inspiración para el marinero de Tolkien, Eärendil , [T 5] que zarpó de las tierras de la Tierra Media para pedir ayuda a los poderes angelicales, los Valar . El primer poema de Tolkien sobre Eärendil, de 1914, el mismo año en que leyó el poema Crist , se refiere al "borde del mundo medio". [3] Tolkien consideraba que el middangeard era "el lugar de residencia de los hombres", [T 6] el mundo físico en el que el Hombre vive su vida y su destino, en oposición a los mundos invisibles por encima y por debajo de él, a saber, el Cielo y el Infierno . Afirma que es "mi propia madre tierra como lugar ", pero en un tiempo pasado imaginario, no en otro planeta. [T 7] Comenzó a utilizar el término "Tierra Media" a finales de los años 1930, en lugar de los términos anteriores "Grandes Tierras", "Tierras Exteriores" y "Tierras de Acá". [3] La primera aparición publicada de la palabra "Tierra Media" en las obras de Tolkien se encuentra en el prólogo de El Señor de los Anillos : "Los hobbits, de hecho, habían vivido tranquilamente en la Tierra Media durante muchos años antes de que otras personas se enteraran de su existencia". [T 8]

El término Tierra Media se ha utilizado como una forma abreviada de referirse a la totalidad del legendarium de Tolkien, en lugar de los términos técnicamente más apropiados, pero menos conocidos, «Arda» para el mundo físico y « Eä » para la realidad física de la creación en su conjunto. En términos geográficos cuidadosos, la Tierra Media es un continente en Arda, excluyendo regiones como Aman y la isla de Númenor. El uso alternativo más amplio se refleja en títulos de libros como La guía completa de la Tierra Media , El camino a la Tierra Media , El atlas de la Tierra Media y la serie de 12 volúmenes de Christopher Tolkien La historia de la Tierra Media . [4] [5]

El biógrafo de Tolkien, Humphrey Carpenter, afirma que la Tierra Media de Tolkien es el mundo conocido, "recordando el Midgard nórdico y las palabras equivalentes en inglés temprano", señalando que Tolkien dejó en claro que este era " nuestro mundo... en un período puramente imaginario... de la antigüedad". [6] Tolkien explicó en una carta a su editor que "es solo un uso del inglés medio middle-erde (o erthe ), alterado del inglés antiguo Middangeard : el nombre de las tierras habitadas de los hombres 'entre los mares'". [T 4] Hay alusiones a un mundo con un nombre similar o idéntico en la obra de otros escritores tanto antes como después de él. La traducción de 1870 de William Morris de la Saga Volsunga llama al mundo "Midgard". [7] El poema de Margaret Widdemer de 1918 "El mago gris" contiene los versos: "Vivía muy alegremente en la Tierra Media / Tan alegre como puede serlo una doncella / Hasta que el mago gris bajó por el camino / Y me arrojó su capa de telaraña..." [8] La Trilogía del espacio de CS Lewis de 1938-1945 llama al planeta de origen "Tierra Media" y hace referencia específicamente al legendarium inédito de Tolkien; ambos hombres eran miembros del grupo de discusión literaria Inklings . [9]

En el contexto general de su legendarium , la Tierra Media de Tolkien era parte de su mundo creado de Arda (que incluye las Tierras Imperecederas de Aman y Eressëa , separadas del resto del mundo físico), que a su vez era parte de la creación más amplia que él llamó Eä. Aman y la Tierra Media están separadas entre sí por el Gran Mar Belegaer , aunque hacen contacto en el extremo norte en el Hielo Crujiente o Helcaraxë. El continente occidental, Aman, era el hogar de los Valar , y los Elfos llamados Eldar . [T 9] En el lado oriental de la Tierra Media estaba el Mar Oriental. La mayoría de los eventos en las historias de Tolkien tienen lugar en el noroeste de la Tierra Media. En la Primera Edad , más al noroeste estaba el subcontinente Beleriand ; fue engullido por el océano al final de la Primera Edad. [5]

Tolkien preparó varios mapas de la Tierra Media. Algunos fueron publicados durante su vida. Los mapas principales son los publicados en El hobbit , El Señor de los Anillos , El Silmarillion y Cuentos inacabados , y aparecen como desplegables o ilustraciones. Tolkien insistió en que se incluyeran mapas en el libro para beneficio de los lectores, a pesar del gasto que implicaba. [T 10] El mapa definitivo e icónico de la Tierra Media fue publicado en El Señor de los Anillos . [T 11] Fue refinado con la aprobación de Tolkien por la ilustradora Pauline Baynes , utilizando las anotaciones detalladas de Tolkien, con imágenes de viñetas y pinturas más grandes en la parte superior e inferior, en un póster independiente, " Un mapa de la Tierra Media ". [10]

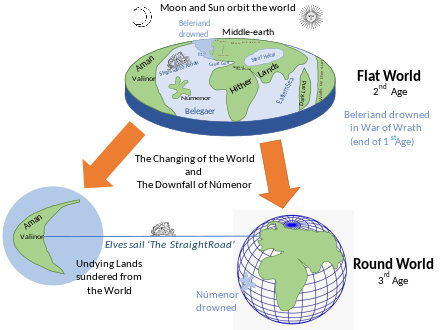

En la concepción de Tolkien, Arda fue creada específicamente como "la Morada" ( Imbar o Ambar ) para los Hijos de Ilúvatar ( Elfos y Hombres ). [12] Está concebida en una cosmología de Tierra plana , con las estrellas, y más tarde también el Sol y la Luna, girando a su alrededor. Los bocetos de Tolkien muestran una cara en forma de disco para el mundo que miraba hacia las estrellas. Sin embargo, el legendarium de Tolkien aborda el paradigma de la Tierra esférica al representar una transición catastrófica de un mundo plano a uno esférico, conocido como Akallabeth, en el que Aman se volvió inaccesible para los Hombres mortales. [11]

Tolkien describió la región en la que vivían los hobbits como "el noroeste del Viejo Mundo, al este del mar", [T 8] y el noroeste del Viejo Mundo es esencialmente Europa , especialmente Gran Bretaña . Sin embargo, como señaló en cartas privadas, las geografías no coinciden, y él no las hizo coincidir conscientemente cuando estaba escribiendo: [T 12]

En cuanto a la forma del mundo de la Tercera Edad , me temo que fue ideada "dramáticamente" más que geológica o paleontológicamente . [T 12]

Tengo una mentalidad histórica. La Tierra Media no es un mundo imaginario... El escenario de mi relato es esta Tierra, aquella en la que vivimos ahora, pero el período histórico es imaginario. Los elementos esenciales de ese lugar de residencia están todos allí (al menos para los habitantes del noroeste de Europa), por lo que naturalmente resulta familiar, aunque un poco glorificado por el encanto de la distancia en el tiempo. [T 13]

...si fuera "historia", sería difícil encajar las tierras y los acontecimientos (o "culturas") en las pruebas que poseemos, arqueológicas o geológicas, sobre la parte más cercana o más remota de lo que ahora se llama Europa; aunque se afirma expresamente que la Comarca , por ejemplo, estuvo en esta región... Espero que la brecha de tiempo, evidentemente larga pero indefinida, entre la Caída de Barad-dûr y nuestros días sea suficiente para la "credibilidad literaria", incluso para los lectores familiarizados con lo que se conoce como "prehistoria". Supongo que he construido un tiempo imaginario, pero he mantenido mis pies sobre mi propia madre tierra como lugar. Prefiero eso al modo contemporáneo de buscar globos remotos en el "espacio". [T 7]

En otra carta, Tolkien hizo correspondencias en latitud entre Europa y la Tierra Media:

La acción de la historia tiene lugar en el noroeste de la «Tierra Media», equivalente en latitud a las costas de Europa y las costas del norte del Mediterráneo. ... Si se considera que Hobbiton y Rivendel están (como se pretendía) en la latitud de Oxford , entonces Minas Tirith , 600 millas al sur, está en la latitud de Florencia . Las desembocaduras del Anduin y la antigua ciudad de Pelargir están en la latitud de la antigua Troya . [T 14]

En otra carta afirmó:

...Muchas gracias por tu carta. ... Llegó mientras estaba fuera, en Gondor ( es decir, Venecia ), como un cambio respecto del Reino del Norte, o habría respondido antes. [13]

Él confirmó, sin embargo, que la Comarca , la tierra de sus héroes hobbits , estaba basada en Inglaterra , en particular en las Midlands Occidentales de su infancia. [T 15] En el Prólogo de El Señor de los Anillos , Tolkien escribe: "Esos días, la Tercera Edad de la Tierra Media, ya han pasado hace mucho, y la forma de todas las tierras ha cambiado..." [T 16] Los Apéndices hacen varias referencias tanto en la historia como en la etimología de los temas "ahora" (en los idiomas ingleses modernos) y "entonces" (idiomas antiguos);

The year no doubt was of the same length,¹ [the footnote here reads: 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 46 seconds.] for long ago as those times are now reckoned in years and lives of men, they were not very remote according to the memory of the Earth.[T 17]

Both the Appendices and The Silmarillion mention constellations, stars and planets that correspond to those seen in the northern hemisphere of Earth, including the Sun, the Moon, Orion (and his belt),[T 18] Ursa Major[T 19][T 20] and Mars. A map annotated by Tolkien places Hobbiton on the same latitude as Oxford, and Minas Tirith at the latitude of Ravenna, Italy. He used Belgrade, Cyprus, and Jerusalem as further reference points.[14]

The history of Middle-earth, as described in The Silmarillion, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe.[T 21] Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees and the Years of the Sun.[T 22] A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees (by which time the Ainur had already long inhabited Arda) and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun.[T 23]

Arda is, as critics have noted, "our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in the past."[15] As such, it has not only an immediate story but a history, and the whole thing is an "imagined prehistory" of the Earth as it is now.[17]

The Ainur were angelic beings created by the one god of Eä, Eru Ilúvatar. The cosmological myth called the Ainulindalë, or "Music of the Ainur", describes how the Ainur sang for Ilúvatar, who then created Eä to give material form to their music. Many of the Ainur entered Eä, and the greatest of these were called the Valar. Melkor, the chief agent of evil in Eä, and later called Morgoth, was initially one of the Valar. With the Valar came lesser spirits of the Ainur, called the Maiar. Melian, the wife of the Elven King Thingol in the First Age, was a Maia. There were also evil Maiar, including the Balrogs and the second Dark Lord, Sauron. Sauron devised the Black Speech (Burzum) for his slaves (such as Orcs) to speak. In the Third Age, five of the Maiar were embodied and sent to Middle-earth to help the free peoples to overthrow Sauron. These are the Istari or Wizards, including Gandalf, Saruman, and Radagast.[T 24]

The Elves are known as "the Firstborn" of Ilúvatar: intelligent beings created by Ilúvatar alone, with many different clans. Originally Elves all spoke the same Common Eldarin ancestral tongue, but over thousands of years it diverged into different languages. The two main Elven languages were Quenya, spoken by the Light Elves, and Sindarin, spoken by the Dark Elves. Physically the Elves resemble humans; indeed, they can marry and have children with them, as shown by the few Half-elven in the legendarium. The Elves are agile and quick footed, being able to walk a tightrope unaided. Their eyesight is keen. Elves are immortal, unless killed in battle. They are re-embodied in Valinor if killed.[18][19]

Men were "the Secondborn" of the Children of Ilúvatar: they awoke in Middle-earth much later than the Elves. Men (and Hobbits) were the last humanoid race to appear in Middle-earth: Dwarves, Ents and Orcs also preceded them. The capitalized term "Man" (plural "Men") is used as a gender-neutral racial description, to distinguish humans from the other human-like races of Middle-earth. In appearance they are much like Elves, but on average less beautiful. Unlike Elves, Men are mortal, ageing and dying quickly, usually living 40–80 years. However the Númenóreans could live several centuries, and their descendants the Dúnedain also tended to live longer than regular humans. This tendency was weakened both by time and by intermingling with lesser peoples.[20]

The Dwarves are a race of humanoids who are shorter than Men but larger than Hobbits. The Dwarves were created by the Vala Aulë, before the Firstborn awoke due to his impatience for the arrival of the children of Ilúvatar to teach and to cherish. When confronted and shamed for his presumption by Ilúvatar, Eru took pity on Aulë and gave his creation the gift of life but under the condition that they be taken and put to sleep in widely separated locations in Middle-earth and not to awaken until after the Firstborn were upon the Earth. They are mortal like Men, but live much longer, usually several hundred years. A peculiarity of Dwarves is that both males and females are bearded, and thus appear identical to outsiders. The language spoken by Dwarves is called Khuzdul, and was kept largely as a secret language for their own use. Like Hobbits, Dwarves live exclusively in Middle-earth. They generally reside under mountains, where they are specialists in mining and metalwork.[21]

Tolkien identified Hobbits as an offshoot of the race of Men. Another name for Hobbit is 'Halfling', as they were generally only half the size of Men. In their lifestyle and habits they closely resemble Men, and in particular Englishmen, except for their preference for living in holes underground. By the time of The Hobbit, most of them lived in the Shire, a region of the northwest of Middle-earth, having migrated there from further east.[22]

The Ents were treelike shepherds of trees, their name coming from an Old English word for giant.[23] Orcs and Trolls (made of stone) were evil creatures bred by Morgoth. They were not original creations but rather "mockeries" of the Children of Ilúvatar and Ents, since only Ilúvatar has the ability to give conscious life to things. The precise origins of Orcs and Trolls are unclear, as Tolkien considered various possibilities and sometimes changed his mind, leaving several inconsistent accounts.[24] Late in the Third Age, the Uruks or Uruk-hai appeared: a race of Orcs of great size and strength that tolerate sunlight better than ordinary Orcs.[T 25] Tolkien also mentions "Men-orcs" and "Orc-men"; or "half-orcs" or "goblin-men". They share some characteristics with Orcs (like "slanty eyes") but look more like men.[T 26] Tolkien, a Catholic, realised he had created a dilemma for himself, as if these beings were sentient and had a sense of right and wrong, then they must have souls and could not have been created wholly evil.[25][26]

Dragons (or "worms") appear in several varieties, distinguished by whether they have wings and whether they breathe fire (cold-drakes versus fire-drakes). The first of the fire-drakes (Urulóki in Quenya)[T 27] was Glaurung the Golden, bred by Morgoth in Angband, and called "The Great Worm", "The Worm of Morgoth", and "The Father of Dragons".[T 28]

Middle-earth contains sapient animals including the Eagles,[T 29] Huan the Great Hound from Valinor and the wolf-like Wargs.[27] In general the origins and nature of these animals are unclear. Giant spiders such as Shelob descended from Ungoliant, of unknown origin.[T 30] Other sapient species include the Crebain, evil crows who become spies for Saruman, and the Ravens of Erebor, who brought news to the Dwarves. The horse-line of the Mearas of Rohan, especially Gandalf's mount, Shadowfax, also appear to be intelligent and understand human speech. The bear-man Beorn had a number of animal friends about his house.[28]

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, both set in Middle-earth, have been the subject of a variety of film adaptations. There were many early failed attempts to bring the fictional universe to life on screen, some even rejected by the author himself, who was skeptical of the prospects of an adaptation. While animated and live-action shorts were made of Tolkien's books in 1967 and 1971, the first commercial depiction of The Hobbit onscreen was the Rankin/Bass animated TV special in 1977.[29] In 1978 the first big screen adaptation of the fictional setting was introduced in Ralph Bakshi's animated The Lord of the Rings.[30]

New Line Cinema released the first part of director Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film series in 2001 as part of a trilogy; it was followed by a prequel trilogy in The Hobbit film series with several of the same actors playing their old roles.[31] In 2003, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King received 11 Academy Award nominations and won all of them, matching the totals awarded to Ben-Hur and Titanic.[32]

Two well-made fan films of Middle-earth, The Hunt for Gollum and Born of Hope, were uploaded to YouTube on 8 May 2009 and 11 December 2009 respectively.[33][34]

Numerous computer and video games have been inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien's works set in Middle-earth. Titles have been produced by studios such as Electronic Arts, Vivendi Games, Melbourne House, and Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment.[35][36] Aside from officially licensed games, many Tolkien-inspired mods, custom maps and total conversions have been made for many games, such as Warcraft III, Minecraft,[37] Rome: Total War, Medieval II: Total War, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. In addition, there are many text-based MMORPGs (known as MU*s) based on Middle-earth. The oldest of these dates back to 1991, and was known as Middle-earth MUD, run by using LPMUD.[38] After the Middle-earth MUD ended in 1992, it was followed by Elendor[39] and MUME.[40]

Lewis's Space Trilogy drew on Tolkien's Middle-earth lore at several points, where he used it to deepen the mythology underlying his action.

Echoes of these Norse battle animals appear throughout Tolkien's literature; in one way or another, all are associated with Gandalf or his cause. ... raven ... Eagles ... wolves ... horses ... Saruman is the one most closely associated with Odin's ravaging wolves and carrion birds