Shetland , también llamadas Islas Shetland , es un archipiélago de Escocia situado entre las islas Orcadas , las islas Feroe y Noruega . Es la región más septentrional del Reino Unido .

Las islas se encuentran a unas 50 millas (80 kilómetros) al noreste de Orkney, a 110 millas (170 km) de Escocia continental y a 140 millas (220 km) al oeste de Noruega. Forman parte de la frontera entre el océano Atlántico al oeste y el mar del Norte al este. Su superficie total es de 1.467 km² ( 566 millas cuadradas), y la población ascendía a 23.020 en 2022. [2] Las islas forman parte de la circunscripción de Shetland del Parlamento escocés . La autoridad local, el Consejo de las Islas Shetland , es una de las 32 áreas del consejo de Escocia. El centro administrativo de las islas, el asentamiento más grande y el único burgo es Lerwick , que ha sido la capital de Shetland desde 1708, antes de lo cual la capital era Scalloway .

El archipiélago tiene un clima oceánico , una geología compleja, una costa accidentada y muchas colinas bajas y onduladas. La isla más grande, conocida como " la Tierra firme ", tiene una superficie de 373 millas cuadradas (967 km 2 ), [3] y es la quinta isla más grande de las Islas Británicas . Es una de las 16 islas habitadas de Shetland.

Los humanos han vivido en Shetland desde el período Mesolítico . Se sabe que los pictos fueron los habitantes originales de las islas, antes de la conquista nórdica y la posterior colonización en la Alta Edad Media . [4] Durante los siglos X al XV, las islas formaron parte del Reino de Noruega hasta que fueron anexadas al Reino de Escocia debido a una disputa real que involucraba el pago de una dote . [5] En 1707, cuando Escocia e Inglaterra se unieron para formar el Reino de Gran Bretaña , el comercio entre Shetland y el norte de Europa continental disminuyó. El descubrimiento de petróleo del Mar del Norte en la década de 1970 impulsó significativamente la economía, el empleo y los ingresos del sector público de Shetland. [6] La pesca siempre ha sido una parte importante de la economía de las islas.

El estilo de vida local refleja la herencia nórdica de las islas, incluidos los festivales de fuego Up Helly Aa y una fuerte tradición musical, especialmente el estilo tradicional de violín . Casi todos los nombres de lugares en las islas tienen origen nórdico. [7] Las islas han producido una variedad de escritores de prosa y poetas, que a menudo han escrito en el dialecto Shetland distintivo del idioma escocés . Muchas áreas en las islas se han reservado para proteger la fauna y la flora locales , incluidos varios sitios importantes de anidación de aves marinas. El poni Shetland y el perro pastor de Shetland son dos razas animales Shetland bien conocidas . Otros animales con razas locales incluyen la oveja Shetland , la vaca , el ganso y el pato . El cerdo Shetland, o grice , se ha extinguido desde aproximadamente 1930.

El lema de las islas, que aparece en el escudo de armas del Consejo , es " Með lögum skal land byggja " ("Por ley se construirá la tierra"). [a] La frase es de origen nórdico antiguo , se menciona en la saga Njáls y probablemente fue tomada prestada de leyes provinciales noruegas como la Ley Frostathing .

El nombre Shetland puede derivar de las palabras nórdicas antiguas hjalt (' empuñadura ') y land ('tierra'), según la reivindicación popular y tradicional. Otra posibilidad es que la primera sílaba derive del nombre de una antigua tribu celta . [8] [9] Andrew Jennings ha sugerido un vínculo con los caledones .

En el año 43 d. C., el autor romano Pomponio Mela hizo referencia en su escrito a siete islas que llamó Haemodae . En el año 77 d. C., Plinio el Viejo llamó a estas mismas islas Acmodae . Los académicos han deducido que ambas referencias son a islas del grupo Shetland. Otra posible referencia escrita temprana a las islas es el informe de Tácito en Agricola en el año 98 d. C. Después de describir el descubrimiento y conquista romanos de Orkney, agregó que la flota romana había visto " Thule , también". [Nota 2] En la literatura irlandesa temprana , Shetland se menciona como Insi Catt - "las Islas de los Gatos" (que significa la isla habitada por la tribu llamada Cat ). Este puede haber sido el nombre de los habitantes pre-nórdicos para las islas. Cat era el nombre de un pueblo picto que ocupaba partes del norte de Escocia continental (véase Reino de Cat ); y su nombre sobrevive en los nombres del condado de Caithness y en el nombre gaélico escocés de Sutherland , Cataibh , que significa "entre los gatos". [12]

La versión más antigua conocida del nombre moderno Shetland es Hetland ; esto puede representar "Catland", la suavización de la C- a H- en la lengua germánica según la ley de Grimm (que también coincide con la hipótesis de Jennings sobre el cambio de sonido temprano necesario para la descendencia de *kalid- a *halit- , de Caledones ). Aparece en una carta escrita por Harald, conde de Orkney, Shetland y Caithness, en ca. 1190. [13] En 1431, las islas eran referidas como Hetland , después de varias transformaciones intermedias. Es posible que el sonido picto "cat" haya contribuido a este nombre nórdico . En el siglo XVI, Shetland era referida como Hjaltland . [14] [15] [Nota 3]

Poco a poco, el idioma norn escandinavo hablado anteriormente por los habitantes de las islas fue reemplazado por el dialecto Shetland del escocés y Hjaltland se convirtió en Ȝetland . La letra inicial es la letra del escocés medio , yogh , cuya pronunciación es casi idéntica al sonido norn original, /hj/ . Cuando se interrumpió el uso de la letra yogh, a menudo se reemplazó por la letra z de aspecto similar (que en ese momento generalmente se representaba con una cola rizada: ⟨ʒ⟩) de ahí Zetland , la forma utilizada en el nombre del consejo del condado anterior a 1975. [16] [17] Esta es la fuente del código postal ZE utilizado para Shetland.

La mayoría de las islas individuales tienen nombres nórdicos , aunque las derivaciones de algunas son oscuras y pueden representar nombres o elementos prenórdicos, pictos o incluso preceltas . [18]

.jpg/440px-Gulberwick_IMG_3157_(20121529905).jpg)

Shetland se encuentra a unos 170 kilómetros al norte de Gran Bretaña y a 230 kilómetros al oeste de Bergen , Noruega . Tiene una superficie de 1468 kilómetros cuadrados y una costa de 2702 kilómetros de largo. [19]

Lerwick , la capital y el asentamiento más grande, tiene una población de 6.958 habitantes y aproximadamente la mitad de la población total del archipiélago, de 22.920 personas [20], vive a 16 km (10 mi) de la ciudad. [21]

Scalloway , en la costa oeste, que fue la capital hasta 1708, tiene una población de menos de 1.000 personas. [22]

Sólo 16 de las 100 islas que componen el grupo están habitadas. La isla principal del grupo se conoce como Mainland . Las siguientes en tamaño son Yell , Unst y Fetlar , que se encuentran al norte, y Bressay y Whalsay , que se encuentran al este. East y West Burra , Muckle Roe , Papa Stour , Trondra y Vaila son islas más pequeñas al oeste de Mainland. Las otras islas habitadas son Foula, a 28 km al oeste de Walls , Fair Isle , a 38 km al suroeste de Sumburgh Head , y Out Skerries, al este. [Nota 4]

Las islas deshabitadas incluyen Mousa , conocida por el Broch de Mousa , el mejor ejemplo conservado de un broch de la Edad de Hierro ; Noss al este de Bressay , que ha sido una reserva natural nacional desde 1955; St Ninian's Isle , conectada a Mainland por el tómbolo activo más grande del Reino Unido; y Out Stack , el punto más septentrional de las Islas Británicas . [23] [24] [25] La ubicación de Shetland significa que proporciona una serie de registros de este tipo: Muness es el castillo más septentrional del Reino Unido y Skaw el asentamiento más septentrional. [26]

La geología de las Shetland es compleja, con numerosas fallas y ejes de pliegue . Estas islas son el puesto avanzado septentrional de la orogenia caledonia , y hay afloramientos de rocas metamórficas de Lewisian , Dalradian y Moine con historias similares a sus equivalentes en el continente escocés. También hay depósitos de arenisca roja antigua e intrusiones de granito . La característica más distintiva es la ofiolita en Unst y Fetlar, que es un remanente del fondo del océano Iapetus compuesto de peridotita ultrabásica y gabro . [27]

Gran parte de la economía de Shetland depende de los sedimentos petrolíferos de los mares circundantes. [28] La evidencia geológica muestra que alrededor del 6100 a. C. un tsunami causado por el deslizamiento de tierra de Storegga golpeó Shetland, así como la costa oeste de Noruega, y puede haber creado una ola de hasta 25 m (82 pies) de altura en los voes donde las poblaciones modernas son más altas. [29]

El punto más alto de las Shetland es Ronas Hill , a 450 m (1480 pies). Las glaciaciones del Pleistoceno cubrieron por completo las islas. Durante ese período, el Stanes of Stofast, un bloque glacial errático de 2000 toneladas , se posó en una prominente cima de una colina en Lunnasting . [30]

Se ha estimado que en Escocia hay unos 275 farallones , de los cuales unos 110 se encuentran en las costas de Shetland. En muchos de ellos no hay constancia de que haya habido intentos de escalada por parte de escaladores . [31] [32]

Shetland tiene un área escénica nacional que, inusualmente, incluye una serie de ubicaciones discretas: Fair Isle, Foula, South West Mainland (incluidas las islas Scalloway ), Muckle Roe, Esha Ness , Fethaland y Herma Ness . [33] El área total cubierta por la designación es de 41.833 ha , de las cuales 26.347 ha son marinas (es decir, por debajo de la marea baja). [34]

En octubre de 2018 entró en vigor en Escocia una ley que impide a los organismos públicos, sin un motivo justificado, mostrar las Shetland en un recuadro separado en los mapas, como se había hecho a menudo. La legislación exige que las islas se muestren "de una manera que represente de forma precisa y proporcionada su ubicación geográfica en relación con el resto de Escocia", de modo que quede clara la distancia real de las islas con respecto a otras zonas. [35] [36] [37]

.jpg/440px-Starry_Nights_IMG_5868_(23146012374).jpg)

Shetland tiene un clima marítimo templado oceánico ( Köppen : Cfb ), que linda con la variedad subpolar , aunque ligeramente por encima de la media en temperaturas de verano , con inviernos largos pero frescos y veranos cortos y cálidos. El clima durante todo el año es moderado debido a la influencia de los mares circundantes, con temperaturas mínimas nocturnas medias de poco más de 1 °C (34 °F) en enero y febrero y temperaturas máximas diurnas medias de cerca de 14 °C (57 °F) en julio y agosto. [38] La temperatura más alta registrada fue de 27,8 °C (82,0 °F) el 6 de agosto de 1910 en Sumburgh Head [39] y la más baja de −8,9 °C (16,0 °F) en los eneros de 1952 y 1959. [40] El período sin heladas puede ser de tan solo tres meses. [41] En cambio, las zonas interiores de la vecina Escandinavia , situadas en latitudes similares, experimentan diferencias de temperatura significativamente mayores entre el verano y el invierno, y las temperaturas máximas medias de los días normales de julio son comparables al récord histórico de calor de Lerwick, que ronda los 23 °C (73 °F), lo que demuestra aún más el efecto moderador del océano Atlántico. En cambio, los inviernos son considerablemente más suaves que los esperados en las zonas continentales cercanas, incluso comparables a las temperaturas invernales de muchas partes de Inglaterra y Gales mucho más al sur.

El clima en general es ventoso, nublado y a menudo húmedo, con al menos 2 mm (0,08 pulgadas) de lluvia cayendo más de 250 días al año. La precipitación media anual es de 1.252 mm (49,3 pulgadas), siendo los meses más lluviosos de noviembre a enero, con un promedio de 5,6 a 5,9 pulgadas de precipitación, principalmente lluvia. Las nevadas suelen limitarse al período de noviembre a febrero, y rara vez la nieve permanece en el suelo durante más de un día. Cae relativamente menos lluvia de abril a julio, aunque en promedio, ningún mes recibe menos de 50 mm (2,0 pulgadas). La niebla es común durante el verano debido al efecto refrescante del mar en las suaves corrientes de aire del sur. [38] [40]

Debido a la latitud de las islas , en las noches claras de invierno a veces se pueden ver las auroras boreales en el cielo, mientras que en verano hay luz diurna casi perpetua , una situación conocida localmente como "simmer tenu" [42] . La media anual de sol brillante es de 1110 horas, y los días nublados son comunes. [43]

Los principales asentamientos de nivel 1, [47] es decir, las áreas de localidad que tienen la mayor población y/o provisión de servicios/instalaciones, son:

Lista de islas por mayor población:

Debido a la práctica, que data al menos del Neolítico temprano , de construir en piedra en islas prácticamente sin árboles, Shetland es extremadamente rica en restos físicos de las eras prehistóricas y hay más de 5000 sitios arqueológicos en total. [52] Un yacimiento de basural en West Voe en la costa sur de Mainland, que data del 4320-4030 a. C., ha proporcionado la primera evidencia de actividad humana mesolítica en Shetland. [53] [54] El mismo sitio proporciona fechas para la actividad neolítica temprana y los hallazgos en Scord of Brouster en Walls han sido datados en el 3400 a. C. [Nota 5] Los "cuchillos de Shetland" son herramientas de piedra que datan de este período hechas de felsita de Northmavine . [56]

Los fragmentos de cerámica encontrados en el importante yacimiento de Jarlshof también indican que hubo actividad neolítica allí, aunque el asentamiento principal data de la Edad del Bronce . [57] Esto incluye una herrería , un grupo de timoneles y un broch posterior. El sitio ha proporcionado evidencia de habitación durante varias fases hasta la época vikinga . [51] [58] Los túmulos en forma de talón son un estilo de túmulo con cámara exclusivo de Shetland, con un ejemplo particularmente grande en Vementry . [56]

Durante la Edad del Hierro se erigieron numerosos brochs . Además de Mousa, hay ruinas importantes en Clickimin , Culswick , Old Scatness y West Burrafirth , aunque su origen y propósito es un tema de cierta controversia. [59] Los habitantes de la Edad del Hierro posterior de las Islas del Norte probablemente eran pictos, aunque el registro histórico es escaso. Hunter (2000) afirma en relación con el rey Bridei I de los pictos en el siglo VI d. C.: "En cuanto a Shetland, Orkney, Skye y las Islas Occidentales, es probable que sus habitantes, la mayoría de los cuales parecen haber sido pictos en cultura y habla en este momento, hayan considerado a Bridei como una presencia bastante distante". [60] En 2011, el sitio colectivo, " El crisol de las Shetland de la Edad del Hierro ", que incluye Broch de Mousa, Old Scatness y Jarlshof, se unió a la "Lista tentativa" de sitios del Patrimonio Mundial del Reino Unido . [61] [62]

La creciente población de Escandinavia provocó una escasez de recursos disponibles y de tierra cultivable allí y condujo a un período de expansión vikinga , por lo que los nórdicos gradualmente cambiaron su atención del saqueo a la invasión. [63] Shetland fue colonizada a fines del siglo VIII y IX, [64] siendo incierto el destino de la población indígena picta existente. Los habitantes de Shetland modernos aún conservan el ADN nórdico y muchos árboles genealógicos muestran el sistema patronímico nórdico (-sson/son, -dottir/daughter). Los estudios de ADN modernos, como el Estudio de Salud Vikingo, tienen graves fallas, ya que solo dan cuenta de una pequeña fracción de la población. [65]

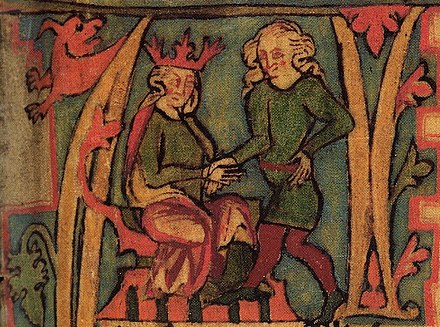

Los vikingos utilizaron las islas como base para expediciones piratas a Noruega y las costas de Escocia continental. En respuesta, el rey noruego Harald Hårfagre ("Harald el Hermoso") anexó las Islas del Norte (que comprendían las Orcadas y las Shetland) en 875. [Nota 6] Rognvald Eysteinsson recibió las Orcadas y las Shetland como condado de Harald como reparación por la muerte de su hijo en batalla en Escocia, y luego pasó el condado a su hermano Sigurd el Poderoso . [67]

Las islas se convirtieron al cristianismo a finales del siglo X. El rey Olaf I Tryggvasson convocó al jarl Sigurd el Fuerte durante una visita a Orkney y le dijo: "Ordeno que tú y todos tus súbditos os bauticéis. Si os negáis, os mataré en el acto y juro que devastaré cada isla con fuego y acero". Como era de esperar, Sigurd aceptó y las islas se convirtieron al cristianismo de un plumazo. [68] Inusualmente, desde alrededor de 1100 en adelante los jarls nórdicos debían lealtad tanto a Noruega como a la corona escocesa a través de sus posesiones como condes de Caithness . [69]

En 1194, cuando Harald Maddadsson era conde de Orkney y Shetland , estalló una rebelión contra el rey Sverre Sigurdsson de Noruega. Los Eyjarskeggjar ("Barbudos de la Isla") navegaron hacia Noruega, pero fueron derrotados en la Batalla de Florvåg , cerca de Bergen . Después de su victoria, el rey Sverre puso a Shetland bajo el dominio noruego directo, una situación que se prolongó durante casi dos siglos. [70] [71]

Desde mediados del siglo XIII en adelante, los monarcas escoceses buscaron cada vez más tomar el control de las islas que rodeaban sus mares. El proceso fue iniciado en serio por Alejandro II y fue continuado por su sucesor Alejandro III . Esta estrategia finalmente llevó a una invasión de Escocia por Haakon IV Haakonsson , rey de Noruega. Su flota se reunió en Bressay Sound antes de zarpar hacia Escocia. Después del punto muerto de la batalla de Largs , Haakon se retiró a Orkney, donde murió en diciembre de 1263, entretenido en su lecho de muerte con recitaciones de las sagas. Su muerte detuvo cualquier expansión noruega en Escocia y después de esta desafortunada expedición, las Hébridas y Mann fueron cedidas al Reino de Escocia como resultado del Tratado de Perth de 1266 , aunque los escoceses reconocieron la soberanía noruega continua sobre Orkney y Shetland. [72] [73] [74]

En el siglo XIV, Orkney y Shetland siguieron siendo posesión noruega, pero la influencia escocesa estaba creciendo. Jon Haraldsson , que fue asesinado en Thurso en 1231, fue el último de una línea ininterrumpida de jarls nórdicos, [75] y a partir de entonces los condes fueron nobles escoceses de las casas de Angus y St Clair . [76] A la muerte de Haakon VI en 1380, [77] Noruega formó una unión política con Dinamarca, después de la cual el interés de la casa real en las islas decayó. [70] En 1469, Shetland fue pignorada por Christian I , en su calidad de rey de Noruega, como garantía contra el pago de la dote de su hija Margarita , prometida a Jacobo III de Escocia . Como el dinero nunca se pagó, la conexión con la Corona de Escocia se volvió permanente. [Nota 7] En 1470, William Sinclair, primer conde de Caithness , cedió su título a Jacobo III, y al año siguiente las Islas del Norte fueron absorbidas directamente por la Corona de Escocia, [80] una acción confirmada por el Parlamento de Escocia en 1472. [81] No obstante, la conexión de Shetland con Noruega ha demostrado ser duradera. [Nota 8]

Desde principios del siglo XV, los habitantes de las Shetlands vendían sus productos a través de la Liga Hanseática de mercaderes alemanes. La Hansa compraba barcos cargados de pescado salado, lana y mantequilla, e importaba sal , telas , cerveza y otros productos. A finales del siglo XVI y principios del XVII, la influencia del déspota Robert Stewart , conde de Orkney, recibió las islas de manos de su media hermana María Estuardo, reina de Escocia , y de su hijo Patrick . Este último comenzó la construcción del castillo de Scalloway , pero después de su encarcelamiento en 1609, la Corona volvió a anexionarse las Orcadas y las Shetland hasta 1643, cuando Carlos I se las concedió a William Douglas, séptimo conde de Morton . Estos derechos los conservaron de forma intermitente los Morton hasta 1766, cuando James Douglas, decimocuarto conde de Morton , los vendió a Laurence Dundas . [82] [83]

.jpg/440px-County_Buildings,_King_Erik_Street,_Lerwick_(geograph_5160230).jpg)

El comercio con las ciudades del norte de Alemania duró hasta el Acta de Unión de 1707 , cuando los altos aranceles a la sal impidieron a los comerciantes alemanes comerciar con Shetland. Shetland entró entonces en una depresión económica, ya que los comerciantes locales no estaban tan capacitados para comerciar con pescado salado. Sin embargo, algunos terratenientes comerciantes locales retomaron el trabajo de los comerciantes alemanes y equiparon sus propios barcos para exportar pescado de Shetland al continente. Para los agricultores independientes de Shetland esto tuvo consecuencias negativas, ya que ahora tenían que pescar para estos terratenientes comerciantes. [84]

La viruela afectó a las islas en los siglos XVII y XVIII (como a toda Europa), pero a medida que las vacunas estuvieron disponibles después de 1800, la salud mejoró. Las islas se vieron muy afectadas por la hambruna de la patata de 1846 y el gobierno introdujo un Plan de Ayuda para las islas bajo el mando del capitán Robert Craigie de la Marina Real, que se quedó en Lerwick para supervisar el proyecto entre 1847 y 1852. Durante este período, Craigie también hizo mucho por mejorar y aumentar las carreteras en las islas. [85]

La población aumentó hasta un máximo de 31.670 en 1861. Sin embargo, el dominio británico tuvo un precio para mucha gente común, así como para los comerciantes. Las habilidades náuticas de los habitantes de las Shetland fueron solicitadas por la Marina Real . Unos 3.000 sirvieron durante las guerras napoleónicas de 1800 a 1815 y las cuadrillas de prensa eran abundantes. Durante este período, 120 hombres fueron capturados solo en Fetlar, y solo 20 de ellos regresaron a casa. A fines del siglo XIX, el 90% de todas las Shetland estaba en manos de solo 32 personas, y entre 1861 y 1881 emigraron más de 8.000 habitantes de las Shetland. [86] [87] Con la aprobación de la Ley de tenencias de crofters (Escocia) de 1886, el primer ministro liberal William Gladstone emancipó a los crofters del gobierno de los terratenientes. La ley permitió que aquellos que habían sido efectivamente siervos de los terratenientes se convirtieran en propietarios-ocupantes de sus propias pequeñas granjas. [88] En ese momento, los pescadores de Holanda , que tradicionalmente se habían reunido cada año en la costa de Shetland para pescar arenque , desencadenaron una industria en las islas que experimentó un auge desde alrededor de 1880 hasta la década de 1920, cuando las existencias de este pez comenzaron a disminuir. [89] La producción alcanzó su punto máximo en 1905 con más de un millón de barriles, de los cuales 708.000 se exportaron. [90]

La Ley de Gobierno Local (Escocia) de 1889 estableció un sistema uniforme de consejos de condado en Escocia y realineó los límites de muchos de los condados de Escocia: el Consejo del Condado de Zetland, que se creó en 1890, se estableció en los Edificios del Condado en Lerwick. [91]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial , muchos habitantes de las Shetland sirvieron en los Gordon Highlanders , otros 3.000 sirvieron en la Marina Mercante y más de 1.500 en una reserva naval local especial. El 10.º Escuadrón de Cruceros estaba estacionado en Swarbacks Minn (el tramo de agua al sur de Muckle Roe), y durante un solo año a partir de marzo de 1917, más de 4.500 barcos zarparon de Lerwick como parte de un sistema de convoyes escoltados. En total, Shetland perdió más de 500 hombres, una proporción mayor que cualquier otra parte de Gran Bretaña, y hubo más oleadas de emigración en las décadas de 1920 y 1930. [87] [92]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , la Dirección de Operaciones Especiales estableció en el otoño de 1940 una unidad naval noruega apodada " Shetland Bus ", con base primero en Lunna y después en Scalloway para realizar operaciones alrededor de la costa de Noruega. Se reunieron alrededor de 30 barcos pesqueros utilizados por refugiados noruegos y el Shetland Bus realizó operaciones encubiertas, transportando agentes de inteligencia, refugiados, instructores para la resistencia y suministros militares. Hizo más de 200 viajes a través del mar, y Leif Larsen , el oficial naval aliado más condecorado de la guerra, hizo 52 de ellos. [93] [94] También se establecieron varios aeródromos y sitios de la RAF en Sullom Voe y varios faros sufrieron ataques aéreos enemigos. [92]

Las reservas de petróleo descubiertas a finales del siglo XX en los mares al este y al oeste de Shetland han proporcionado una fuente alternativa de ingresos muy necesaria para las islas. [6] La cuenca de Shetland Oriental es una de las provincias petroleras más prolíficas de Europa. Como resultado de los ingresos del petróleo y los vínculos culturales con Noruega, se desarrolló brevemente un pequeño movimiento de autogobierno para reformular la posición constitucional de Shetland . Vio como modelos a la Isla de Man , así como al vecino más cercano de Shetland, las Islas Feroe , una dependencia autónoma de Dinamarca. [95]

La población era de 17.814 habitantes en 1961. [96]

En la actualidad, los principales productores de ingresos en Shetland son la agricultura , la acuicultura , la pesca , la energía renovable , la industria petrolera ( producción de petróleo crudo y gas natural ), las industrias creativas y el turismo . [97] Unst también tiene un sitio de lanzamiento de cohetes llamado SaxaVord Spaceport (anteriormente conocido como Shetland Space Centre). [98] Una noticia de febrero de 2021 indicó que un fabricante de cohetes de Alemania, HyImpulse Technologies, planeaba lanzar naves espaciales impulsadas por hidrógeno desde el puerto espacial, a partir de 2023. [99] Durante el mes anterior, el Centro Espacial había presentado planes al Consejo para una "instalación de lanzamiento de satélites e infraestructura asociada". [100]

En febrero de 2021, la información del sitio web Promote Shetland indicaba que "Shetland depende menos del turismo que muchas islas escocesas" y que el petróleo era un sector importante de la economía. También se hizo hincapié en el "proceso de transición gradual del petróleo a la energía limpia y renovable... la producción de hidrógeno limpio". La pesca seguía siendo el sector principal y se esperaba que creciera. [101]

La pesca es fundamental para la economía de las islas en la actualidad, con una captura total de 75.767 t (83.519 toneladas) en 2009, valorada en más de 73,2 millones de libras esterlinas. La caballa del Atlántico representa más de la mitad de la captura en Shetland en peso y valor, y hay desembarques significativos de eglefino , bacalao , arenque , merlán , rape y mariscos . [102]

Un informe publicado en octubre de 2020 se mostraba optimista sobre el futuro de este sector: "Con nuevos mercados de pescado en Lerwick y Scalloway, y planes para ampliar su oferta de acuicultura en Yell, Shetland se está preparando para un mayor crecimiento en su industria más grande". [103]

En febrero de 2021, el sitio web Promote Shetland afirmó que "se desembarca más pescado en Shetland que en Inglaterra, Gales e Irlanda del Norte juntos", que "Shetland cosecha 40.000 toneladas de salmón al año, por un valor de 180 millones de libras" y que "en Shetland se cultivan 6.500 toneladas de mejillones, más del 80 por ciento de la producción escocesa total". [104]

Oil and gas were first landed in 1978 at Sullom Voe, which has subsequently become one of the largest terminals in Europe.[6][105] Taxes from the oil have increased public sector spending on social welfare, art, sport, environmental measures and financial development. Three quarters of the islands' workforce is employed in the service sector,[106][107] and the Shetland Islands Council alone accounted for 27.9% of output in 2003.[108][109] Shetland's access to oil revenues has funded the Shetland Charitable Trust, which in turn funds a wide variety of local programmes. The balance of the fund in 2011 was £217 million, i.e., about £9,500 per head.[110][Note 9]

In January 2007, the Shetland Islands Council signed a partnership agreement with Scottish and Southern Energy for the Viking Wind Farm, a 200-turbine wind farm and subsea cable. This renewable energy project would produce about 600 megawatts and contribute about £20 million to the Shetland economy per year.[112] The plan met with significant opposition within the islands, primarily resulting from the anticipated visual impact of the development.[113] However, in August 2024 the completion of the first part of the project saw Shetland connected to the mainland National Grid for the first time via a 600 MW HVDC link.[114]

The PURE project in Unst is a research centre which uses a combination of wind power and fuel cells to create a wind-hydrogen system. The project is run by the Unst Partnership, the local community's development trust.[115][116]

A status report on hydrogen production in Shetland, published in September 2020, stated that Shetland Islands Council (SIC) had "joined a number of organisations and projects to drive forward plans to establish hydrogen as a future energy source for the isles and beyond". For example, it was a member of the Scottish Hydrogen Fuel Cell Association (SHFCA). The ORION project, previously named the Shetland Energy Hub, was underway; the plan was to create an energy hub that would use clean electricity in the development of "new technologies such as blue and green hydrogen generation".[117]

In December 2020 the Scottish government released a hydrogen policy statement with plans for incorporating both blue and green hydrogen for use in heating, transportation and industry.[118] The government also planned an investment of £100 million in the hydrogen sector "for the £180 million Emerging Energy Technologies Fund".[119] Shetland Islands Council planned to obtain further specifics about the availability of funding. The government had already agreed that the production of "green" hydrogen from wind power near Sullom Voe Terminal was a valid plan. A December 2020 report stated that "the extensive terminal could also be used for direct refuelling of hydrogen-powered ships" and suggested that the fourth jetty at Sullom Voe "could be suitable for ammonia export".[120]

Farming is mostly concerned with the raising of Shetland sheep, known for their unusually fine wool.[22][121][122]

Knitwear is important both to the economy and culture of Shetland, and the Fair Isle design is well known. However, the industry faces challenges due to plagiarism of the word "Shetland" by manufacturers operating elsewhere, and a certification trademark, "The Shetland Lady", has been registered.[123]

Crofting, the farming of small plots of land on a legally restricted tenancy basis, is still practised and is viewed as a key Shetland tradition as well as an important source of income.[124] Crops raised include oats and barley; however, the cold, windswept islands make for a harsh environment for most plants.

Television signals in Shetland are received from the Bressay TV transmitter.[125] Shetland is served by a weekly local newspaper, The Shetland Times and the online Shetland News [126] with radio service being provided by BBC Radio Shetland and the commercial radio station SIBC.[127]

Shetland is a popular destination for cruise ships, and in 2010 the Lonely Planet guide named Shetland as the sixth best region in the world for tourists seeking unspoilt destinations. The islands were described as "beautiful and rewarding" and the Shetlanders as "a fiercely independent and self-reliant bunch".[128] Overall visitor expenditure was worth £16.4 million in 2006, in which year just under 26,000 cruise liner passengers arrived at Lerwick Harbour. This business has grown substantially with 109 cruise ships already booked in for 2019, representing over 107,000 passenger visits.[129] In 2009, the most popular visitor attractions were the Shetland Museum, the RSPB reserve at Sumburgh Head, Bonhoga Gallery at Weisdale Mill and Jarlshof.[130] Geopark Shetland (now Shetland UNESCO Global Geopark) was established by the Amenity Trust in 2009 to boost sustainable tourism to the islands.[131]

According to the Promote Shetland organisation's website, tourism increased "by £12.6 million between 2017 and 2019 with more than half of visitors giving their trip a perfect rating".[104]

Extremely popular in many countries, with seven series having been filmed and aired by early 2023, Shetland (TV series) was inspired by the Ann Cleeves books about the fictional Detective Inspector Jimmy Perez. This has created an interest in Shetland[132] and some tourists visit because they wish to see the places where the series is set and filmed. In 2018, series star Douglas Henshall said in an interview, "When we were there filming, there's people from Australia and different parts of America who had come specifically because of the show ... It's showing all over the world. Now you get a lot of people from Scandinavia on these noir tours".[133][134]

An October 2018 report stated that 91,000 passengers from cruise ships arrived that year (a record high), an increase over the 70,000 in 2017. There was a drop in 2019 to "over 76,000 cruise ship passengers".[135][136]

Tourism dropped significantly in 2020 (and into 2021) due to restrictions necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the major decline in the number of cruise ships that continued to operate worldwide.[137]

As of early February 2021, the Promote Shetland website was still stating this information: "At present, nobody should travel to Shetland from a Level 3 or Level 4 local authority area in Scotland, unless it's for essential purposes". That page reiterated the government recommendation "that people avoid any unnecessary travel between Scotland and England, Wales, or Northern Ireland".[138]

A September 2020 report stated that "The Highlands and Islands region has been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic to date, when compared to Scotland and the UK as a whole". The tourism industry required short-term support for "business survival and recovery" and that was expected to continue as the sector was "severely impacted for as long as physical distancing and travel restrictions" remained in place.[139] As of 31 December 2020, the usage of ferries and buses was restricted to those traveling for essential purposes.[140] The Island Equivalent scheme was introduced in early 2021 by the Scottish government to financially assist hospitality and retail businesses "affected by Level 3 coronavirus restrictions". Previous schemes in 2020 included the Strategic Framework Business Fund and the Coronavirus Business Support Fund.[141]

Transport between islands is primarily by ferry, and Shetland Islands Council operates various inter-island services.[142] Shetland is also served by a domestic connection from Lerwick to Aberdeen on mainland Scotland. This service, which takes about 12 hours, is operated by NorthLink Ferries. Some services also call at Kirkwall, Orkney, which increases the journey time between Aberdeen and Lerwick by 2 hours.[143][144] There are plans for road tunnels to some of the islands, especially Bressay and Whalsay; however, it is hard to convince the mainland government to finance them.[145]

Sumburgh Airport, the main airport in Shetland, is located close to Sumburgh Head, 40 km (25 mi) south of Lerwick. Loganair operates flights to other parts of Scotland up to ten times a day, the destinations being Kirkwall, Aberdeen, Inverness, Glasgow and Edinburgh.[146] Lerwick/Tingwall Airport is located 11 km (6.8 mi) west of Lerwick. Operated by Directflight in partnership with Shetland Islands Council, it is devoted to inter-island flights from the Shetland Mainland to Fair Isle and Foula.[147]

Scatsta Airport was an airport near Sullom Voe which allowed frequent charter flights from Aberdeen to transport oilfield workers. The airport closed on 30 June 2020.[148]

Public bus services are operated in Mainland, Trondra, Burra, Unst and Yell, with scheduled dial-a-ride services available in Bressay and Fetlar. Buses also connect with ferries leading to Foula, Papa Stour, and Whalsay.[149][150]

The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and there are numerous sites of wrecked ships.[151] Lighthouses are sited as an aid to navigation at various locations.[152]

The Shetland Islands Council is the local government authority for all the islands and is based in Lerwick Town Hall.

Shetland is sub-divided into 18 community council areas[153] and into 12 civil parishes that are used for statistical purposes.[154]

As of early 2021, Shetland had 22 primary schools, five junior high schools, and two high schools: Anderson High School and Brae High School.[156][157]

Shetland College UHI is a partner of the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI). UHI's Centre for Rural Creativity partners with Shetland Arts Development Agency to provide courses on film, music and media up to Masters level at Mareel. The North Atlantic Fisheries College (NAFC) also operates in partnership with UHI offering "a range of training courses relevant to the maritime industries".[156]

The Institute for Northern Studies, operated by UHI, provides "postgraduate teaching and research programmes"; one of the three locations is at Shetland.[158]

The Shetland Football Association oversees two divisions — a Premier League and a Reserve League — which are affiliated with the Scottish Amateur Football Association.[159] Seasons take place during summer.

The islands are represented by the Shetland football team, which regularly competes in the Island Games.

Religion in Shetland (2011)[160]

The Reformation reached the archipelago in 1560. This was an apparently peaceful transition and there is little evidence of religious intolerance in Shetland's recorded history.[161]

In the 2011 census, Shetland registered a higher proportion of people with no religion than the Scottish average.[160] Nevertheless, a variety of religious denominations are represented in the islands.

The Methodist Church has a relatively high membership in Shetland, which is a District of the Methodist Church (with the rest of Scotland comprising a separate District).[162]

The Church of Scotland had a Presbytery of Shetland that includes St. Columba's Church in Lerwick.[163] On 1 June 2020 the Presbytery of Shetland merged with the Presbytery of Aberdeen becoming the Presbytery of Aberdeen and Shetland. In addition there was further church reorganisation in the islands with a series of church closures and all parishes merging into one, covering the whole of Shetland.

The Catholic population is served by the church of St. Margaret and the Sacred Heart in Lerwick. The parish is part of the Diocese of Aberdeen.

The Scottish Episcopal Church (part of the Anglican Communion) has regular worship at: St Magnus' Church, Lerwick; St Colman's Church, Burravoe; and the Chapel of Christ the Encompasser, Fetlar, the last of which is maintained by the Society of Our Lady of the Isles, the most northerly and remote Anglican religious order of nuns.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a congregation in Lerwick. The former print works and offices of the local newspaper, The Shetland Times, has been converted into a chapel. Jehovah's Witnesses has a congregation and Kingdom Hall in Lerwick.

Shetland is represented in the House of Commons as part of the Orkney and Shetland constituency, which elects one Member of Parliament (MP). As of May 2023, and since 2001, the MP is Alistair Carmichael, a Liberal Democrat.[164] This seat has been held by the Liberal Democrats or their predecessors the Liberal Party since 1950, longer than any other seat in the United Kingdom.[165][166][167]

In the Scottish Parliament the Shetland constituency elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post system. Tavish Scott of the Scottish Liberal Democrats had held the seat since the creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.[168] Beatrice Wishart MSP, also of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, was elected to replace Tavish Scott in August 2019.[169] Shetland is also within the Highlands and Islands electoral region which elects seven MSPs.

The political composition of the Shetland Islands Council is 21 Independents and 1 Scottish National Party.[170]

In the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom, Shetland voted to remain in the United Kingdom by the third largest margin of the 32 local authority areas, by 63.71% to 36.29% in favour of the Union.

In the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, Shetland voted for the UK to remain an EU member state, with 56.5% voting to remain and 43.5% voting to leave. In comparison to the rest of Scotland, Shetland had lower-than-average support for remaining in the EU.

The Wir Shetland movement was set up in 2015 to campaign for greater autonomy.[171] In September 2020, the Shetland Islands Council voted 18–2 to explore replacing the council with a new system of government which controls a fairer share of the islands revenue streams and has a greater influence over their own affairs, which could include very lucrative oil fields and fishing waters.[172]

In 2022, as part of the Levelling Up White Paper, an "Island Forum" was proposed, which would allow local policymakers and residents in Shetland to work alongside their counterparts in Orkney, the Western Isles, Anglesey and the Isle of Wight on common issues, such as broadband connectivity, and provide a platform for them to communicate directly with the government on the challenges island communities face in terms of levelling up.[173][174]

Roy Grönneberg, who founded the local chapter of the Scottish National Party in 1966, designed the flag of Shetland in cooperation with Bill Adams to mark the 500th anniversary of the transfer of the islands from Norway to Scotland. The colours are identical to those of the flag of Scotland, but are shaped in the Nordic cross. After several unsuccessful attempts, including a plebiscite in 1985, the Lord Lyon King of Arms approved it as the official flag of Shetland in 2005.[175][Note 10]

30Jan1973.jpg/440px-UpHellyAa3(AnneBurgess)30Jan1973.jpg)

After the islands were officially transferred from Norway to Scotland in 1472, several Scots families from the Scottish Lowlands emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries.[176][177] Studies of the genetic makeup of the islands' population, however, indicate that Shetlanders are just under half Scandinavian in origin, and sizeable amounts of Scandinavian ancestry, both patrilineal and matrilineal, have been reported in Orkney (55%) and Shetland (68%).[177] This combination is reflected in many aspects of local life. For example, almost every place name in use can be traced back to the Vikings.[178] The Lerwick Up Helly Aa is one of several fire festivals held in Shetland annually in the middle of winter, starting on the last Tuesday of January.[179] The festival is just over 100 years old in its present, highly organised form. Originally held to break up the long nights of winter and mark the end of Yule, the festival has become one celebrating the isles' heritage and includes a procession of men dressed as Vikings and the burning of a replica longship.[180]

Shetland also competes in the biennial International Island Games, which it hosted in 2005.[181]

The cuisine of Shetland is based on locally produced lamb, beef and seafood, some of it organic. The real ale-producing Valhalla Brewery is the most northerly in Britain. The Shetland Black is a variety of blue potato with a dark skin and indigo-coloured flesh markings.[182]

The Norn language was a form of Old Norse spoken in the Northern Isles, and continued to be spoken until the 18th century. It was gradually replaced in Shetland by an insular dialect of Scots, known as Shetlandic, which is in turn being replaced by Scottish English. Although Norn was spoken for hundreds of years, it is now extinct and few written sources remain, although influences remain in the Insular Scots dialects.[183] The Shetland dialect is used in local radio and dialect writing, and is kept alive by organisations such as Shetland Forwirds, and the Shetland Folk Society.[184][185][186]

Shetland's culture and landscapes have inspired a variety of musicians, writers and film-makers. The Forty Fiddlers was formed in the 1950s to promote the traditional fiddle style, which is a vibrant part of local culture today.[187] Notable exponents of Shetland folk music include Aly Bain, Jenna Reid, Fiddlers' Bid, and the late Tom Anderson and Peerie Willie Johnson. Thomas Fraser was a country musician who never released a commercial recording during his life, but whose work has become popular more than 20 years after his death in 1978.[188]

The annual Shetland Folk Festival began in 1981 and is hosted on the first weekend of May.[189]

Walter Scott's 1822 novel The Pirate is set in "a remote part of Shetland", and was inspired by his 1814 visit to the islands. The name Jarlshof meaning "Earl's Mansion" is a coinage of his.[190] Robert Cowie, a doctor born in Lerwick published the 1874 work entitled Shetland: Descriptive and Historical; Being a Graduation Thesis on the Inhabitants of the Shetland Islands; and a Topographical Description of the Country. Menzies. 1874.

Hugh MacDiarmid, the Scots poet and writer, lived in Whalsay from the mid-1930s through 1942, and wrote many poems there, including a number that directly address or reflect the Shetland environment, such as "On A Raised Beach", which was inspired by a visit to West Linga.[191] The 1975 novel North Star by Hammond Innes is largely set in Shetland and Raman Mundair's 2007 book of poetry A Choreographer's Cartography offers a British Asian perspective on the landscape.[192] The Shetland Quartet by Ann Cleeves, who previously lived in Fair Isle, is a series of crime novels set around the islands.[193] In 2013, her novel Red Bones became the basis of BBC crime drama television series Shetland.[194]

Vagaland, who grew up in Walls, was arguably Shetland's finest poet of the 20th century.[195] Haldane Burgess was a Shetland historian, poet, novelist, violinist, linguist and socialist, and Rhoda Bulter (1929–1994) is one of the best-known Shetland poets of recent times. Other 20th- and 21st-century poets and novelists include Christine De Luca, Robert Alan Jamieson who grew up in Sandness, the late Lollie Graham of Veensgarth, Stella Sutherland of Bressay,[196] the late William J. Tait from Yell[197] and Laureen Johnson.[198]

There is one monthly magazine in production: Shetland.[199] The quarterly The New Shetlander, founded in 1947, is said to be Scotland's longest-running literary magazine.[200] For much of the later 20th century, it was the major vehicle for the work of local writers — and of others, including early work by George Mackay Brown.[201]

Michael Powell made The Edge of the World in 1937, a dramatisation based on the true story of the evacuation of the last 36 inhabitants of the remote island of St Kilda on 29 August 1930. St Kilda lies in the Atlantic Ocean, 64 km (40 mi) west of the Outer Hebrides but Powell was unable to get permission to film there. Undaunted, he made the film over four months during the summer of 1936 in Foula and the film transposes these events to Shetland. Forty years later, the documentary Return to the Edge of the World was filmed, capturing a reunion of cast and crew of the film as they revisited the island in 1978.

A number of other films have been made on or about Shetland including A Crofter's Life in Shetland (1932),[202] A Shetland Lyric (1934),[203] Devil's Gate (2003) and It's Nice Up North (2006), a comedy documentary by Graham Fellows. The Screenplay film festival takes place annually in Mareel, a cinema, music and education venue.

The BBC One television series Shetland, a crime drama, is set in the islands and is based on the book series by Ann Cleeves. The programme is filmed partly in Shetland and partly on the Scottish mainland.[204][205]

Shetland has three national nature reserves, at the seabird colonies of Hermaness and Noss, and at Keen of Hamar to preserve the serpentine flora. There are a further 81 SSSIs, which cover 66% or more of the land surfaces of Fair Isle, Papa Stour, Fetlar, Noss, and Foula. Mainland has 45 separate sites.[206]

The landscape in Shetland is marked by the grazing of sheep and the harsh conditions have limited the total number of plant species to about 400. Native trees such as rowan and crab apple are only found in a few isolated places such as cliffs and loch islands. The flora is dominated by Arctic-alpine plants, wild flowers, moss and lichen. Spring squill, buck's-horn plantain, Scots lovage, roseroot and sea campion are abundant, especially in sheltered places. Shetland mouse-ear (Cerastium nigrescens) is an endemic flowering plant found only in Shetland. It was first recorded in 1837 by botanist Thomas Edmondston. Although reported from two other sites in the nineteenth century, it currently grows only on two serpentine hills in the island of Unst. The nationally scarce oysterplant is found in several islands and the British Red Listed bryophyte Thamnobryum alopecurum has also been recorded.[207][208][209][210] Listed marine algae include: Polysiphonia fibrillosa (Dillwyn) Sprengel and Polysiphonia atlantica Kapraun and J.Norris, Polysiphonia brodiaei (Dillwyn) Sprengel, Polysiphonia elongata (Hudson) Sprengel, Polysiphonia elongella, Harvey.[211] The Shetland Monkeyflower is unique to Shetland and is a mutation of the Monkeyflower (mimulus guttatus) introduced to Shetland in the 19th century.[212][213]

.jpg/440px-Puffin_Party_IMG_3348_(19674441423).jpg)

Shetland has numerous seabird colonies. Birds found in the islands include Atlantic puffin, storm-petrel, red-throated diver, northern gannet and great skua (locally called "bonxie").[214] Numerous rarities have also been recorded including black-browed albatross and snow goose. A single pair of snowy owls bred in Fetlar from 1967 to 1975.[214][215][216] The Shetland wren, Fair Isle wren, and Shetland starling are subspecies endemic to Shetland.[217][218] There are also populations of various moorland birds such as curlew, lapwing, snipe and golden plover.[219]

One of the early ornithologists that wrote about the wealth of birdlife in Shetland was Edmund Selous (1857–1934) in his book The Bird Watcher in the Shetlands (1905).[220] He wrote extensively about the gulls and terns, about the arctic skuas, the black guillemots and many other birds (and the seals) of the islands.

The geographical isolation and recent glacial history of Shetland have resulted in a depleted mammalian fauna and the brown rat and house mouse are two of only three species of rodent present in the islands. The Shetland field mouse is the third and the archipelago's fourth endemic subspecies, of which there are three varieties in Yell, Foula, and Fair Isle.[218] They are variants of Apodemus sylvaticus and archaeological evidence suggests that this species was present during the Middle Iron Age (around 200 BC to 400 CE). It is possible that Apodemus was introduced from Orkney where a population has existed since at the least the Bronze Age.[221]

.jpg/440px-Chilling_Out_MG_9137_(34618081391).jpg)

There is a variety of indigenous breeds, of which the diminutive Shetland pony is probably the best known, as well as being an important part of the Shetland farming tradition. The first written record of the pony was in 1603 in the Court Books of Shetland and, for its size, it is the strongest of all the horse breeds.[222][223] Others are the Shetland Sheepdog or "Sheltie", the endangered Shetland cattle[224] and Shetland goose[225][226] and the Shetland sheep which is believed to have originated prior to 1000 AD.[227] The Grice was a breed of semi-domesticated pig that had a habit of attacking lambs. It became extinct sometime between the middle of the nineteenth century and the 1930s.[228]

If you are one of the millions of people around the world fascinated by Jimmy Perez and his crime-solving adventures in Ann Cleeves' Shetland – now a major BBC TV series, we think you'll love the real place

VisitScotland in Shetland last year said the Shetland TV series and books had been an "amazing success" for the islands

from 28 December 2020 to 24 January 2021, businesses in Level 3 island areas, including Shetland, can now apply for a payment of £2,000 or £3,000

What James III had acquired from Earl William in return for this compensation was the comital rights in Orkney and Shetland. He already held a wadset of the royal rights; and to ensure his complete control, he referred the matter to parliament. On 20 February 1472, the three estates approved the annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the crown...