Warren Gamaliel Harding (2 de noviembre de 1865 - 2 de agosto de 1923) fue el 29.º presidente de los Estados Unidos , cargo que ocupó desde 1921 hasta su muerte en 1923. Miembro del Partido Republicano , fue uno de los presidentes estadounidenses en funciones más populares durante su mandato. Tras su muerte, se expusieron varios escándalos, entre ellos Teapot Dome , así como una relación extramatrimonial con Nan Britton , que empañó su reputación.

Harding vivió en la zona rural de Ohio toda su vida, excepto cuando el servicio político lo llevó a otro lugar. Cuando era joven, compró The Marion Star y lo convirtió en un periódico exitoso. Harding sirvió en el Senado del estado de Ohio de 1900 a 1904, y fue vicegobernador durante dos años. Fue derrotado para gobernador en 1910 , pero fue elegido para el Senado de los Estados Unidos en 1914 , la primera elección directa del estado para ese cargo. Harding se postuló para la nominación republicana para presidente en 1920, pero se consideró una posibilidad remota antes de la convención . Cuando los candidatos principales no pudieron obtener una mayoría, y la convención quedó en un punto muerto, el apoyo a Harding aumentó y fue nominado en la décima votación. Llevó a cabo una campaña desde el porche , permaneciendo principalmente en Marion y permitiendo que la gente acudiera a él. Prometió un regreso a la normalidad del período anterior a la Primera Guerra Mundial , y derrotó al candidato demócrata James M. Cox en una victoria aplastante para convertirse en el primer senador en funciones elegido presidente.

Harding nombró a varias figuras respetadas para su gabinete , entre ellas Andrew Mellon en el Tesoro , Herbert Hoover en el Departamento de Comercio y Charles Evans Hughes en el Departamento de Estado . Un logro importante en política exterior llegó con la Conferencia Naval de Washington de 1921-1922, en la que las principales potencias navales del mundo acordaron un programa de limitaciones navales que duró una década. Harding liberó a prisioneros políticos que habían sido arrestados por su oposición a la Primera Guerra Mundial . En 1923, Harding murió de un ataque cardíaco en San Francisco mientras estaba en una gira por el oeste, y fue sucedido por el vicepresidente Calvin Coolidge .

Harding murió como uno de los presidentes más populares de la historia, pero la posterior exposición de escándalos erosionó su estima popular, al igual que las revelaciones de relaciones extramatrimoniales. El secretario del Interior de Harding, Albert B. Fall , y su fiscal general , Harry Daugherty , fueron posteriormente juzgados por corrupción en el cargo. Fall fue condenado, pero Daugherty no. Estos juicios dañaron enormemente la reputación póstuma de Harding. En las clasificaciones históricas de los presidentes de Estados Unidos durante las décadas posteriores a su mandato, Harding fue clasificado a menudo entre los peores, pero en las últimas décadas, algunos historiadores han comenzado a reevaluar las opiniones convencionales sobre el historial histórico de Harding en el cargo.

Warren Harding nació el 2 de noviembre de 1865 en Blooming Grove, Ohio . [1] Apodado "Winnie" cuando era pequeño, fue el mayor de ocho hijos de George Tryon Harding (generalmente conocido como Tryon) y Phoebe Elizabeth (de soltera Dickerson) Harding. [1] Phoebe era una partera con licencia estatal . Tryon cultivaba y enseñaba en la escuela cerca del Monte Gilead . A través del aprendizaje, el estudio y un año en la escuela de medicina, Tryon se convirtió en médico y comenzó una pequeña práctica. [2] El primer antepasado de Harding en las Américas fue Richard Harding, quien llegó de Inglaterra a la bahía de Massachusetts alrededor de 1624. [3] [4] Harding también tenía antepasados de Gales y Escocia, [5] y algunos de sus antepasados maternos eran holandeses, incluida la adinerada familia Van Kirk. [6]

Un oponente político en Blooming Grove rumoreaba que una de las bisabuelas de Harding era afroamericana . [7] Su tatarabuelo Amos Harding afirmó que un ladrón, que había sido atrapado en el acto por la familia, inició el rumor en un intento de extorsión o venganza. [8] En 2015, las pruebas genéticas de los descendientes de Harding determinaron, con más de un 95% de posibilidades de precisión, que carecía de antepasados africanos subsaharianos en cuatro generaciones. [9] [10]

En 1870, la familia Harding, que era abolicionista , [10] se mudó a Caledonia , donde Tryon adquirió The Argus , un periódico semanal local. En The Argus , Harding, desde los 11 años, aprendió los conceptos básicos del negocio periodístico. [11] A fines de 1879, a los 14 años, se inscribió en el alma mater de su padre , Ohio Central College en Iberia , donde demostró ser un estudiante experto. Él y un amigo publicaron un pequeño periódico, Iberia Spectator , durante su último año en Ohio Central, con la intención de atraer tanto a la universidad como a la ciudad. Durante su último año, la familia Harding se mudó a Marion , a unas 6 millas (10 km) de Caledonia, y cuando se graduó en 1882, se unió a ellos allí. [12]

En la juventud de Harding, la mayor parte de la población estadounidense todavía vivía en granjas y en pequeños pueblos. Harding pasó gran parte de su vida en Marion, una pequeña ciudad en la zona rural del centro de Ohio, y se relacionó estrechamente con ella. Cuando llegó a un alto cargo, dejó en claro su amor por Marion y su estilo de vida, hablando de los muchos jóvenes marionitas que se habían ido y disfrutado del éxito en otros lugares, al tiempo que sugería que el hombre, antaño el "orgullo de la escuela", que se había quedado atrás y se había convertido en conserje, era "el más feliz de todos". [13]

Al graduarse, Harding trabajó como profesor y como agente de seguros, e hizo un breve intento de estudiar derecho. Luego recaudó $300 (equivalentes a $9,800 en 2023) en asociación con otros para comprar un periódico en decadencia, The Marion Star , el más débil de los tres periódicos de la creciente ciudad y su único diario. Harding, de 18 años, utilizó el pase de tren que venía con el periódico para asistir a la Convención Nacional Republicana de 1884 , donde se codeó con periodistas más conocidos y apoyó al candidato presidencial, el exsecretario de Estado James G. Blaine . Harding regresó de Chicago para encontrar que el sheriff había reclamado el periódico. [14] Durante la campaña electoral, Harding trabajó para el Marion Democratic Mirror y estaba molesto por tener que elogiar al candidato presidencial demócrata, el gobernador de Nueva York Grover Cleveland , quien ganó las elecciones . [15] Después, con la ayuda financiera de su padre, Harding obtuvo la propiedad del periódico. [14]

Durante los últimos años de la década de 1880, Harding construyó el periódico Star . La ciudad de Marion tendía a votar por los republicanos (al igual que Ohio), pero el condado de Marion era demócrata. En consecuencia, Harding adoptó una postura editorial moderada, declarando que el diario Star era imparcial y distribuyó una edición semanal que era moderadamente republicana. Esta política atrajo a los anunciantes y sacó del mercado al semanario republicano de la ciudad. Según su biógrafo, Andrew Sinclair:

El éxito de Harding con el Star fue, sin duda, similar al de Horatio Alger . Empezó sin nada y, a base de trabajar, ganar tiempo, fanfarronear, retener pagos, pedir prestados salarios atrasados, fanfarronear y manipular, convirtió un periódico moribundo en un poderoso periódico de pueblo. Gran parte de su éxito se debió a su buena apariencia, a su afabilidad, a su entusiasmo y a su persistencia, pero también tuvo suerte. Como señaló una vez Maquiavelo , la inteligencia lleva lejos a un hombre, pero no puede prescindir de la buena fortuna. [16]

La población de Marion creció de 4.000 en 1880 al doble en 1890, y a 12.000 en 1900. Este crecimiento ayudó al Star , y Harding hizo todo lo posible por promover la ciudad, comprando acciones de muchas empresas locales. Algunas de ellas resultaron mal, pero en general tuvo éxito como inversor, dejando un patrimonio de 850.000 dólares en 1923 (equivalente a 15,2 millones de dólares en 2023). [17] Según el biógrafo de Harding , John Dean , la "influencia cívica de Harding era la de un activista que usaba su página editorial para mantener eficazmente su nariz -y una voz incisiva- en todos los asuntos públicos de la ciudad". [18] Hasta la fecha, Harding es el único presidente de los EE. UU. que ha tenido experiencia en periodismo a tiempo completo. [14] Se convirtió en un ferviente partidario del gobernador Joseph B. Foraker , un republicano. [19]

Harding conoció a Florence Kling , cinco años mayor que él, hija de un banquero y promotor inmobiliario local. Amos Kling era un hombre acostumbrado a salirse con la suya, pero Harding lo atacó implacablemente en el periódico. Amos involucró a Florence en todos sus asuntos, llevándola a trabajar desde que pudo caminar. Florence, tan testaruda como su padre, entró en conflicto con él después de regresar de la escuela de música. [a] Después de que se fugó con Pete deWolfe y regresó a Marion sin deWolfe y con un bebé llamado Marshall , Amos aceptó criar al niño, pero no apoyó a Florence, que se ganaba la vida como profesora de piano. Una de sus alumnas fue la hermana de Harding, Charity. En 1886, Florence Kling había obtenido el divorcio y ella y Harding estaban cortejándose, aunque no se sabe con certeza quién perseguía a quién. [20] [21]

El conflicto en ciernes acabó con una tregua entre los Kling. Amos creía que los Harding tenían sangre afroamericana y también se sintió ofendido por las posturas editoriales de Harding. Comenzó a difundir rumores sobre la supuesta ascendencia negra de Harding y alentó a los empresarios locales a boicotear los intereses comerciales de Harding. [10] Cuando Harding descubrió lo que estaba haciendo Kling, le advirtió que "le daría una paliza al hombrecillo si no dejaba de hacerlo". [b] [22]

Los Harding se casaron el 8 de julio de 1891, [23] en su nuevo hogar en Mount Vernon Avenue en Marion, que habían diseñado juntos en estilo Reina Ana . [24] El matrimonio no tuvo hijos. [25] Harding llamaba cariñosamente a su esposa "la Duquesa" por un personaje de una serie de The New York Sun que vigilaba de cerca al "Duque" y su dinero. [26]

Florence Harding se involucró profundamente en la carrera de su esposo, tanto en el Star como después de que él entró en la política. [20] Mostrando la determinación y el sentido comercial de su padre, ayudó a convertir al Star en una empresa rentable a través de su estricta gestión del departamento de circulación del periódico. [27] Se le atribuye haber ayudado a Harding a lograr más de lo que hubiera podido lograr solo; algunos han sugerido que lo empujó hasta la Casa Blanca. [28]

Poco después de comprar el Star , Harding centró su atención en la política, apoyando a Foraker en su primera candidatura exitosa para gobernador en 1885. Foraker fue parte de la generación de la guerra que desafió a los republicanos de Ohio más antiguos, como el senador John Sherman , por el control de la política estatal. Harding, siempre leal al partido, apoyó a Foraker en la compleja guerra interna que era la política republicana de Ohio. Harding estaba dispuesto a tolerar a los demócratas como necesarios para un sistema bipartidista , pero solo sentía desprecio por aquellos que abandonaban el Partido Republicano para unirse a movimientos de terceros partidos. [29] Fue delegado de la convención estatal republicana en 1888, a la edad de 22 años, en representación del condado de Marion, y sería elegido delegado en la mayoría de los años hasta convertirse en presidente. [30]

El éxito de Harding como editor afectó su salud. Entre 1889 (cuando tenía 23 años) y 1901, pasó cinco veces en el sanatorio de Battle Creek por razones que Sinclair describió como "fatiga, sobreesfuerzo y enfermedades nerviosas". [31] Dean relaciona estas visitas con los primeros episodios de la enfermedad cardíaca que mataría a Harding en 1923. Durante una de esas ausencias de Marion, en 1894, el director comercial del Star renunció. Florence Harding ocupó su lugar. Se convirtió en la principal asistente de su marido en el Star en el aspecto comercial, cargo que mantuvo hasta que los Harding se mudaron a Washington en 1915. Su competencia le permitió a Harding viajar para pronunciar discursos; su uso del pase gratuito de ferrocarril aumentó mucho después de su matrimonio. [32] Florence Harding practicó una estricta economía [27] y escribió sobre Harding: "lo hace bien cuando me escucha y mal cuando no lo hace". [33]

En 1892, Harding viajó a Washington, donde conoció al congresista demócrata de Nebraska William Jennings Bryan , y escuchó al "niño orador de Platte" hablar en el pleno de la Cámara de Representantes . Harding viajó a la Exposición Colombina de Chicago en 1893. Ambas visitas fueron sin Florence. Los demócratas generalmente ganaron los cargos del condado de Marion; cuando Harding se postuló para auditor en 1895, perdió, pero lo hizo mejor de lo esperado. Al año siguiente, Harding fue uno de los muchos oradores que hablaron en Ohio como parte de la campaña del candidato presidencial republicano, el ex gobernador de ese estado, William McKinley . Según Dean, "mientras trabajaba para McKinley [Harding] comenzó a hacerse un nombre en Ohio". [32]

Harding deseaba volver a intentar un cargo electivo. Aunque era un admirador de Foraker desde hacía mucho tiempo (por entonces senador de los EE. UU.), había tenido cuidado de mantener buenas relaciones con la facción del partido liderada por el otro senador estadounidense del estado, Mark Hanna , el representante político de McKinley y presidente del Comité Nacional Republicano (RNC). Tanto Foraker como Hanna apoyaron a Harding para el Senado estatal en 1899; ganó la nominación republicana y fue elegido fácilmente para un mandato de dos años. [34]

Harding comenzó sus cuatro años como senador estatal como un desconocido político; los terminó como una de las figuras más populares del Partido Republicano de Ohio. Siempre parecía tranquilo y mostraba humildad, características que lo hicieron querido por sus compañeros republicanos incluso cuando los superó en su ascenso político. Los líderes legislativos lo consultaban sobre problemas difíciles. [35] Era habitual en ese momento que los senadores estatales en Ohio cumplieran solo un mandato, pero Harding ganó la renominación en 1901. Después del asesinato de McKinley en septiembre (fue sucedido por el vicepresidente Theodore Roosevelt ), gran parte del apetito por la política se perdió temporalmente en Ohio. En noviembre, Harding ganó un segundo mandato, más del doble de su margen de victoria a 3.563 votos. [36]

Como la mayoría de los políticos de su tiempo, Harding aceptó que el clientelismo y la corrupción se utilizarían para devolver favores políticos. Hizo que su hermana Mary (que era legalmente ciega) fuera nombrada maestra en la Escuela para Ciegos de Ohio , aunque había candidatos mejor calificados. En otro negocio, ofreció publicidad en su periódico a cambio de pases de tren gratis para él y su familia. Según Sinclair, "es dudoso que Harding haya pensado alguna vez que había algo deshonesto en aceptar los requisitos de un cargo o puesto. El clientelismo y los favores parecían la recompensa normal por el servicio al partido en los días de Hanna". [37]

Poco después de su primera elección como senador, Harding conoció a Harry M. Daugherty , quien desempeñaría un papel importante en su carrera política. Daugherty, un candidato perenne a un cargo público que cumplió dos mandatos en la Cámara de Representantes del estado a principios de la década de 1890, se había convertido en un solucionador de problemas políticos y un cabildero en la capital del estado, Columbus. Después de conocer y hablar por primera vez con Harding, Daugherty comentó: "Vaya, sería un presidente muy atractivo". [38]

A principios de 1903, Harding anunció que se postularía para gobernador de Ohio , motivado por la retirada del candidato principal, el congresista Charles WF Dick . Hanna y George Cox sintieron que Harding no era elegible debido a su trabajo con Foraker: cuando comenzó la Era Progresista , el público comenzaba a tener una visión más negativa del comercio de favores políticos y de jefes como Cox. En consecuencia, persuadieron al banquero de Cleveland Myron T. Herrick , un amigo de McKinley, para que se postulara. Herrick también estaba en mejor posición para quitarle votos al probable candidato demócrata, el alcalde reformista de Cleveland Tom L. Johnson . Con pocas posibilidades de obtener la nominación a gobernador, Harding buscó la nominación como vicegobernador, y tanto Herrick como Harding fueron nominados por aclamación. [39] Foraker y Hanna (que murió de fiebre tifoidea en febrero de 1904) hicieron campaña para lo que se denominó la candidatura Four-H. Herrick y Harding ganaron por márgenes abrumadores. [40]

Una vez que él y Harding fueron inaugurados, Herrick tomó decisiones desacertadas que pusieron a distritos electorales republicanos cruciales en su contra, alejando a los agricultores al oponerse al establecimiento de una escuela de agricultura. [40] Por otro lado, según Sinclair, "Harding tenía poco que hacer, y lo hizo muy bien". [41] Su responsabilidad de presidir el Senado estatal le permitió aumentar su creciente red de contactos políticos. [41] Harding y otros imaginaron una exitosa campaña para gobernador en 1905, pero Herrick se negó a hacerse a un lado. A principios de 1905, Harding anunció que aceptaría la nominación como gobernador si se la ofrecían, pero ante la ira de líderes como Cox, Foraker y Dick (el reemplazo de Hanna en el Senado), anunció que no buscaría ningún cargo en 1905. Herrick fue derrotado, pero su nuevo compañero de fórmula, Andrew L. Harris , fue elegido, y sucedió como gobernador después de cinco meses en el cargo tras la muerte del demócrata John M. Pattison . Un funcionario republicano le escribió a Harding: "¿No te arrepientes de que Dick no te haya dejado postularte para vicegobernador?" [42]

Además de ayudar a elegir un presidente, los votantes de Ohio en 1908 debían elegir a los legisladores que decidirían si reelegir a Foraker. El senador se había peleado con el presidente Roosevelt por el caso Brownsville . Aunque Foraker tenía pocas posibilidades de ganar, buscó la nominación presidencial republicana contra su compatriota de Cincinnati, el secretario de Guerra William Howard Taft , quien fue el sucesor elegido por Roosevelt. [43] El 6 de enero de 1908, Harding's Star respaldó a Foraker y reprendió a Roosevelt por tratar de destruir la carrera del senador por una cuestión de conciencia. El 22 de enero, Harding en el Star cambió de opinión y se declaró a favor de Taft, considerando derrotado a Foraker. [44] Según Sinclair, el cambio de Harding a Taft "no fue ... porque vio la luz sino porque sintió el calor". [45] El hecho de sumarse al movimiento de Taft le permitió a Harding sobrevivir al desastre de su patrón: Foraker no logró obtener la nominación presidencial y fue derrotado para un tercer mandato como senador. También ayudó a salvar la carrera de Harding el hecho de que era popular entre las fuerzas más progresistas que ahora controlaban el Partido Republicano de Ohio y les había hecho favores. [46]

Harding buscó y ganó la nominación republicana a gobernador en 1910. En ese momento, el partido estaba profundamente dividido entre las alas progresistas y conservadoras, y no pudo derrotar a los demócratas unidos; perdió la elección ante el titular Judson Harmon . [47] Harry Daugherty dirigió la campaña de Harding, pero el candidato derrotado no le echó la culpa de la derrota. A pesar de la creciente brecha entre ellos, tanto el presidente Taft como el ex presidente Roosevelt llegaron a Ohio para hacer campaña por Harding, pero sus disputas dividieron al Partido Republicano y ayudaron a asegurar la derrota de Harding. [48]

La división del partido aumentó y en 1912 Taft y Roosevelt se enfrentaron por la nominación republicana. La Convención Nacional Republicana de 1912 estuvo muy dividida. A petición de Taft, Harding pronunció un discurso nominando al presidente, pero los delegados enojados no fueron receptivos a la oratoria de Harding. Taft fue nominado nuevamente, pero los partidarios de Roosevelt abandonaron el partido. Harding, como republicano leal, apoyó a Taft. El voto republicano se dividió entre Taft, el candidato oficial del partido, y Roosevelt, que se presentaba bajo la etiqueta del Partido Progresista . Esto permitió que el candidato demócrata, el gobernador de Nueva Jersey Woodrow Wilson , fuera elegido. [49]

El congresista Theodore Burton había sido elegido senador por la legislatura estatal en lugar de Foraker en 1909, y anunció que buscaría un segundo mandato en las elecciones de 1914. Para entonces, se había ratificado la Decimoséptima Enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos , que otorgaba al pueblo el derecho a elegir senadores, y Ohio había instituido elecciones primarias para el cargo. Foraker y el ex congresista Ralph D. Cole también participaron en las primarias republicanas. Cuando Burton se retiró, Foraker se convirtió en el favorito, pero su republicanismo de la vieja guardia se consideró obsoleto, y se instó a Harding a participar en la carrera. Daugherty se atribuyó el mérito de persuadir a Harding para que se presentara: "Lo encontré como una tortuga tomando el sol en un tronco, y lo empujé al agua". [50] Según el biógrafo de Harding, Randolph Downes, "hizo una campaña de tal dulzura y ligereza que se habría ganado los aplausos de los ángeles. Estaba calculada para no ofender a nadie excepto a los demócratas". [51] Aunque Harding no atacó a Foraker, sus partidarios no tuvieron esos escrúpulos. Harding ganó las primarias por 12.000 votos sobre Foraker. [52]

Lee La Amenaza y obtén la información,

ve a las urnas y vence al Papa.

Lema escrito en muros y vallas de Ohio, 1914 [53]

El oponente de Harding en las elecciones generales fue el fiscal general de Ohio, Timothy Hogan , que había ascendido a un cargo estatal a pesar del prejuicio generalizado contra los católicos romanos en las zonas rurales. En 1914, el inicio de la Primera Guerra Mundial y la perspectiva de un senador católico de Ohio aumentaron el sentimiento nativista . Las hojas de propaganda con nombres como La Amenaza y El Defensor contenían advertencias de que Hogan era la vanguardia de un complot dirigido por el Papa Benedicto XV a través de los Caballeros de Colón para controlar Ohio. Harding no atacó a Hogan (un viejo amigo) en este o en la mayoría de los otros temas, pero no denunció el odio nativista hacia su oponente. [54] [55]

El estilo conciliador de campaña de Harding lo ayudó; [55] un amigo de Harding consideró el discurso de campaña del candidato durante la campaña de otoño de 1914 como "una mezcla inconexa y altisonante de lugares comunes, patriotismo y pura tontería". [56] Dean señala: "Harding utilizó su oratoria con buenos resultados; lo llevó a ser elegido, haciendo el menor número posible de enemigos en el proceso". [56] Harding ganó por más de 100.000 votos en una victoria aplastante que también llevó al cargo a un gobernador republicano, Frank B. Willis . [56]

Cuando Harding se unió al Senado de los Estados Unidos, los demócratas controlaban ambas cámaras del Congreso y estaban liderados por el presidente Wilson. Como senador junior en la minoría, Harding recibió asignaciones de comités sin importancia, pero llevó a cabo esas tareas con asiduidad. [57] Era un voto republicano conservador y seguro. [58] Al igual que durante su tiempo en el Senado de Ohio, Harding llegó a ser muy querido. [59]

En dos cuestiones, el sufragio femenino y la prohibición del alcohol , en las que elegir el lado equivocado habría dañado sus perspectivas presidenciales en 1920, prosperó al adoptar posiciones matizadas. Como senador electo, indicó que no podía apoyar el voto femenino hasta que Ohio lo hiciera. El aumento del apoyo al sufragio allí y entre los republicanos del Senado significó que, cuando el Congreso votó sobre el tema, Harding era un firme partidario. Harding, que bebía, [60] inicialmente votó en contra de prohibir el alcohol. Votó a favor de la Decimoctava Enmienda , que impuso la prohibición, después de intentar modificarla con éxito poniendo un límite de tiempo a la ratificación, lo que se esperaba que la matara. Una vez que fue ratificada de todos modos, Harding votó para anular el veto de Wilson al Proyecto de Ley Volstead , que implementó la enmienda, asegurando el apoyo de la Liga Anti-Saloon . [61]

Harding, como político respetado tanto por republicanos como por progresistas , fue invitado a ser presidente temporal de la Convención Nacional Republicana de 1916 y a pronunciar el discurso inaugural . Instó a los delegados a presentarse como un partido unido. La convención nominó al juez Charles Evans Hughes . [62] Harding se acercó a Roosevelt una vez que el expresidente rechazó la nominación progresista de 1916 , una negativa que efectivamente hundió a ese partido. En las elecciones presidenciales de noviembre de 1916 , a pesar de la creciente unidad republicana, Hughes fue derrotado por poco ante Wilson. [63]

Harding habló y votó a favor de la resolución de la guerra solicitada por Wilson en abril de 1917 que sumió a los Estados Unidos en la Primera Guerra Mundial. [64] En agosto, Harding abogó por dar a Wilson poderes casi dictatoriales, afirmando que la democracia tenía poco lugar en tiempos de guerra. [65] Harding votó a favor de la mayoría de las leyes de guerra, incluida la Ley de Espionaje de 1917 , que restringía las libertades civiles, aunque se opuso al impuesto a las ganancias excesivas por considerarlo contrario a los negocios. En mayo de 1918, Harding, menos entusiasta sobre Wilson, se opuso a un proyecto de ley para ampliar los poderes del presidente. [66]

En las elecciones de mitad de período del Congreso de 1918, celebradas justo antes del armisticio , los republicanos tomaron el control del Senado por un estrecho margen. [67] Harding fue designado para el Comité de Relaciones Exteriores del Senado . [68] Wilson no llevó a ningún senador con él a la Conferencia de Paz de París , confiado en que podría forzar lo que se convirtió en el Tratado de Versalles a través del Senado apelando al pueblo. [67] Cuando regresó con un solo tratado que establecía tanto la paz como una Sociedad de Naciones , el país estaba abrumadoramente de su lado. A muchos senadores les disgustaba el Artículo X del Pacto de la Sociedad , que comprometía a los signatarios a la defensa de cualquier nación miembro que fuera atacada, viéndolo como obligar a los Estados Unidos a la guerra sin el consentimiento del Congreso. Harding fue uno de los 39 senadores que firmaron una carta de todos contra todos oponiéndose a la Sociedad. Cuando Wilson invitó al Comité de Relaciones Exteriores a la Casa Blanca para discutir informalmente el tratado, Harding interrogó hábilmente a Wilson sobre el Artículo X; el presidente evadió sus preguntas. El Senado debatió Versalles en septiembre de 1919 y Harding pronunció un importante discurso en su contra. Para entonces, Wilson había sufrido un derrame cerebral durante una gira de conferencias. Con un presidente incapacitado en la Casa Blanca y menos apoyo en el país, el tratado fue derrotado. [69]

_Harding_LCCN2016819939_(cropped).jpg/440px-Sen._Warren_S._(G.)_Harding_LCCN2016819939_(cropped).jpg)

Como la mayoría de los progresistas se habían reincorporado al Partido Republicano, se consideró probable que su ex líder, Theodore Roosevelt, hiciera una tercera candidatura a la Casa Blanca en 1920, y era el gran favorito para la nominación republicana. Estos planes terminaron cuando Roosevelt murió repentinamente el 6 de enero de 1919. Rápidamente surgieron varios candidatos, entre ellos el general Leonard Wood , el gobernador de Illinois Frank Lowden , el senador de California Hiram Johnson y una serie de posibilidades relativamente menores como Herbert Hoover (famoso por su trabajo de socorro en la Primera Guerra Mundial), el gobernador de Massachusetts Calvin Coolidge y el general John J. Pershing . [70]

Harding, aunque quería ser presidente, estaba tan motivado al entrar en la carrera por su deseo de mantener el control de la política republicana de Ohio, lo que le permitió su reelección al Senado en 1920. Entre los que codiciaban el asiento de Harding estaban el ex gobernador Willis (había sido derrotado por James M. Cox en 1916) y el coronel William Cooper Procter (director de Procter & Gamble ). El 17 de diciembre de 1919, Harding hizo un anuncio discreto de su candidatura presidencial. [71] A los principales republicanos no les gustaba Wood y Johnson, ambos de la facción progresista del partido, y Lowden, que tenía una veta independiente, no era considerado mucho mejor. Harding era mucho más aceptable para los líderes de la "vieja guardia" del partido. [72]

Daugherty, que se convirtió en el director de campaña de Harding, estaba seguro de que ninguno de los otros candidatos podría conseguir una mayoría. Su estrategia fue hacer de Harding una opción aceptable para los delegados una vez que los líderes flaquearan. Daugherty estableció una oficina de campaña "Harding para presidente" en Washington (dirigida por su confidente, Jess Smith ), y trabajó para gestionar una red de amigos y partidarios de Harding, incluido Frank Scobey de Texas (secretario del Senado del estado de Ohio durante los años de Harding allí). [73] Harding trabajó para apuntalar su apoyo mediante la escritura incesante de cartas. A pesar del trabajo del candidato, según Russell, "sin los esfuerzos mefistofélicos de Daugherty , Harding nunca habría logrado la nominación". [74]

La necesidad actual de Estados Unidos no es heroísmo, sino curación; no panaceas, sino normalidad; no revolución, sino restauración; no agitación, sino ajuste; no cirugía, sino serenidad; no lo dramático, sino lo desapasionado; no experimentación, sino equilibrio; no inmersión en la internacionalidad, sino sostenimiento en una nacionalidad triunfante.

Warren G. Harding, discurso ante el Home Market Club, Boston, 14 de mayo de 1920 [75]

En 1920, hubo sólo 16 estados con primarias presidenciales, de los cuales el más crucial para Harding fue Ohio. Harding necesitaba tener algunos leales en la convención para tener alguna posibilidad de nominación, y la campaña de Wood esperaba sacar a Harding de la carrera ganando Ohio. Wood hizo campaña en el estado, y su partidario, Procter, gastó grandes sumas; Harding habló en el estilo no confrontativo que había adoptado en 1914. Harding y Daugherty estaban tan seguros de arrasar con los 48 delegados de Ohio que el candidato pasó al siguiente estado, Indiana, antes de las primarias de Ohio del 27 de abril. [76] Harding ganó Ohio por sólo 15.000 votos sobre Wood, obteniendo menos de la mitad del voto total, y ganó sólo 39 de los 48 delegados. En Indiana, Harding terminó cuarto, con menos del diez por ciento de los votos, y no logró ganar ni un solo delegado. Estaba dispuesto a rendirse y dejar que Daugherty presentara sus papeles de reelección para el Senado, pero Florence Harding le arrebató el teléfono de la mano: "Warren Harding, ¿qué estás haciendo? ¿Rendirte? No hasta que termine la convención. ¡Piensa en tus amigos en Ohio!" [77] Al enterarse de que Daugherty había dejado la línea telefónica, la futura Primera Dama replicó: "Bueno, dile a Harry Daugherty de mi parte que estaremos en esta lucha hasta que el infierno se congele". [75]

Después de recuperarse del shock de los malos resultados, Harding viajó a Boston, donde pronunció un discurso que, según Dean, "resonaría durante toda la campaña de 1920 y la historia". [75] Allí, dijo que "la necesidad actual de Estados Unidos no es heroísmo, sino curación; no panaceas, sino normalidad; [c] no revolución, sino restauración". [78] Dean señala: "Harding, más que los otros aspirantes, estaba leyendo correctamente el pulso de la nación". [75]

El 8 de junio de 1920 se inauguró en el Chicago Coliseum la Convención Nacional Republicana , en la que se reunieron delegados profundamente divididos, sobre todo por los resultados de una investigación del Senado sobre los gastos de campaña, que acababa de publicarse. Ese informe determinó que Wood había gastado 1,8 millones de dólares (equivalentes a 27,38 millones en 2023), lo que dio fundamento a las afirmaciones de Johnson de que Wood estaba tratando de comprar la presidencia. Parte de los 600.000 dólares que Lowden había gastado habían acabado en los bolsillos de dos delegados de la convención. Johnson había gastado 194.000 dólares y Harding, 113.000. Se consideró que Johnson estaba detrás de la investigación, y la furia de las facciones de Lowden y Wood puso fin a cualquier posible compromiso entre los favoritos. De los casi 1.000 delegados, 27 eran mujeres: la Decimonovena Enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos , que garantizaba el voto a las mujeres, estaba a un estado de ratificarse y se aprobaría antes de finales de agosto. [79] [80] La convención no tenía jefe, la mayoría de los delegados sin formación votaban como querían y, con un demócrata en la Casa Blanca, los líderes del partido no podían usar el clientelismo para salirse con la suya. [81]

Los periodistas consideraron que era poco probable que Harding fuera nominado debido a su pobre desempeño en las primarias, y lo relegaron a un lugar entre los caballos oscuros . [79] Harding, quien al igual que los otros candidatos estaba en Chicago supervisando su campaña, había terminado sexto en la encuesta de opinión pública final, detrás de los tres candidatos principales, así como del ex juez Hughes y Herbert Hoover, y solo ligeramente por delante de Coolidge. [82] [83]

Después de que la convención tratara otros asuntos, las nominaciones para presidente se abrieron en la mañana del viernes 11 de junio. Harding había pedido a Willis que pusiera su nombre en la nominación, y el ex gobernador respondió con un discurso popular entre los delegados, tanto por su carácter campestre como por su brevedad en el intenso calor de Chicago. [84] El reportero Mark Sullivan, que estaba presente, lo calificó como una espléndida combinación de "oratoria, gran ópera y canto de cerdos ". Willis confesó, inclinándose sobre la barandilla del podio: "Digan, muchachos, y muchachas también, ¿por qué no nombran a Warren Harding?" [85] Las risas y los aplausos que siguieron crearon un sentimiento cálido para Harding. [85]

No espero que el senador Harding sea nominado en la primera, segunda o tercera votación, pero creo que podemos darnos el lujo de correr el riesgo de que alrededor de las once minutos después de las dos de la mañana del viernes en la convención, cuando quince o veinte hombres, algo cansados, estén sentados alrededor de una mesa, alguno de ellos diga: "¿A quién nominaremos?" En ese momento decisivo, los amigos del senador Harding pueden sugerirlo y permitirse el lujo de atenerse al resultado.

Harry M. Daugherty [86]

El 11 de junio por la tarde se realizaron cuatro votaciones que revelaron un empate. Con 493 votos necesarios para la nominación, Wood fue el que más cerca estuvo de conseguirlo con 314 1/2; Lowden tuvo 289 1/2. Lo mejor que Harding había logrado fue 65 1/2 . El presidente Henry Cabot Lodge de Massachusetts , líder de la mayoría del Senado , levantó la convención alrededor de las 7 p . m. [85] [87]

La noche del 11 al 12 de junio de 1920 se haría famosa en la historia política como la noche de la " sala llena de humo ", en la que, según cuenta la leyenda, los líderes del partido acordaron obligar a la convención a nominar a Harding. Los historiadores se han centrado en la sesión celebrada en la suite del presidente del Comité Nacional Republicano (RNC), Will Hays, en el Hotel Blackstone , en la que senadores y otros iban y venían, y se discutieron numerosos candidatos posibles. El senador de Utah Reed Smoot , antes de su partida a primera hora de la tarde, respaldó a Harding, diciendo a Hays y a los demás que, como era probable que los demócratas nominaran al gobernador Cox, deberían elegir a Harding para ganar Ohio. Smoot también le dijo al New York Times que había habido un acuerdo para nominar a Harding, pero que aún no se haría durante varias votaciones. [88] Esto no era cierto: varios participantes respaldaron a Harding (otros apoyaron a sus rivales), pero no hubo ningún pacto para nominarlo, y los senadores tenían poco poder para hacer cumplir cualquier acuerdo. Otros dos participantes en las discusiones en la sala llena de humo, el senador de Kansas Charles Curtis y el coronel George Brinton McClellan Harvey , un amigo cercano de Hays, predijeron a la prensa que Harding sería nominado debido a las responsabilidades de los otros candidatos. [89]

Los titulares de los periódicos matutinos sugerían intrigas. El historiador Wesley M. Bagby escribió: "Varios grupos trabajaron en líneas separadas para lograr la nominación, sin combinarse y con muy poco contacto". Bagby dijo que el factor clave en la nominación de Harding fue su amplia popularidad entre las bases de los delegados. [90]

Los delegados reunidos nuevamente habían oído rumores de que Harding era la elección de una camarilla de senadores. Aunque esto no era cierto, los delegados lo creyeron y buscaron una salida votando por Harding. Cuando la votación se reanudó en la mañana del 12 de junio, Harding ganó votos en cada una de las siguientes cuatro votaciones, aumentando a 133 1 ⁄ 2 mientras que los dos favoritos vieron pocos cambios. Lodge entonces declaró un receso de tres horas, para indignación de Daugherty, quien corrió al podio y lo confrontó: "¡No pueden derrotar a este hombre de esta manera! ¡La moción no fue aprobada! ¡No pueden derrotar a este hombre!" [91] Lodge y otros usaron el receso para tratar de detener el impulso de Harding y hacer que el presidente del RNC Hays fuera el candidato, un plan con el que Hays se negó a tener nada que ver. [92] La novena votación, después de un suspenso inicial, vio a delegación tras delegación dividirse en dos a favor de Harding, que tomó la delantera con 374 1 ⁄ 2 votos contra 249 de Wood y 121 1 ⁄ 2 de Lowden (Johnson tenía 83). Lowden entregó sus delegados a Harding, y la décima votación, celebrada a las 6 p. m., fue una mera formalidad, con Harding terminando con 672 1 ⁄ 5 votos contra 156 de Wood. La nominación fue unánime. Los delegados, desesperados por irse de la ciudad antes de incurrir en más gastos de hotel, procedieron entonces a la nominación a vicepresidente. Harding quería al senador Irvine Lenroot de Wisconsin, que no estaba dispuesto a presentarse, pero antes de que el nombre de Lenroot pudiera ser retirado y se decidiera otro candidato, un delegado de Oregón propuso al gobernador Coolidge, que fue recibido con un rugido de aprobación por parte de los delegados. Coolidge, popular por su papel en la disolución de la huelga de la policía de Boston en 1919, fue nominado a vicepresidente y recibió dos votos y medio más que Harding. James Morgan escribió en The Boston Globe : "Los delegados no quisieron quedarse en Chicago el domingo... los que eligieron al presidente no tenían ni una camisa limpia. De esas cosas, Rollo, depende el destino de las naciones". [93] [94]

La candidatura Harding/Coolidge fue rápidamente respaldada por los periódicos republicanos, pero los que tenían otros puntos de vista expresaron su decepción. El New York World consideró a Harding el candidato menos calificado desde James Buchanan , y consideró al senador de Ohio un hombre "débil y mediocre" que "nunca tuvo una idea original". [95] Los periódicos de Hearst llamaron a Harding "el abanderado de una nueva autocracia senatorial". [96] El New York Times describió al candidato presidencial republicano como "un político de Ohio muy respetable de segunda clase". [95]

La Convención Nacional Demócrata se inauguró en San Francisco el 28 de junio de 1920, bajo la sombra de Woodrow Wilson, que deseaba ser nominado para un tercer mandato. Los delegados estaban convencidos de que la salud de Wilson no le permitiría servir, y buscaron un candidato en otra parte. El ex secretario del Tesoro William G. McAdoo era un contendiente importante, pero era el yerno de Wilson y se negó a considerar una nominación mientras el presidente la quisiera. Muchos en la convención votaron por McAdoo de todos modos, y se produjo un punto muerto con el fiscal general A. Mitchell Palmer . En la 44.ª votación, los demócratas nominaron al gobernador Cox para presidente, con su compañero de fórmula, el secretario adjunto de la Marina Franklin D. Roosevelt . Como Cox era, cuando no estaba en política, propietario y editor de un periódico, esto puso a dos editores de Ohio uno contra el otro por la presidencia, y algunos se quejaron de que no había una elección política real. Tanto Cox como Harding eran conservadores económicos y, en el mejor de los casos, progresistas reacios. [97]

Harding decidió llevar a cabo una campaña desde el porche delantero , como McKinley en 1896. [98] Algunos años antes, Harding había remodelado su porche delantero para que se pareciera al de McKinley, lo que sus vecinos sintieron que significaba ambiciones presidenciales. [99] El candidato permaneció en su casa en Marion y dio discursos a las delegaciones visitantes. Mientras tanto, Cox y Roosevelt hicieron campaña por la nación, dando cientos de discursos. Coolidge habló en el noreste, más tarde en el sur, y no fue un factor significativo en la elección. [98]

In Marion, Harding ran his campaign. As a newspaperman himself, he fell into easy camaraderie with the press covering him, enjoying a relationship few presidents have equaled. His "return to normalcy" theme was aided by the atmosphere that Marion provided, an orderly place that induced nostalgia in many voters. The front porch campaign allowed Harding to avoid mistakes, and as time dwindled towards the election, his strength grew. The travels of the Democratic candidates eventually caused Harding to make several short speaking tours, but for the most part, he remained in Marion. America had no need for another Wilson, Harding argued, appealing for a president "near the normal."[100]

Harding's vague oratory irritated some; McAdoo described a typical Harding speech as "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea. Sometimes these meandering words actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly, a prisoner in their midst, until it died of servitude and over work."[101] H. L. Mencken concurred, "it reminds me of a string of wet sponges, it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a kind of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm ... of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of tosh. It is rumble and bumble. It is balder and dash."[d][101] The New York Times took a more positive view of Harding's speeches, writing that in them the majority of people could find "a reflection of their own indeterminate thoughts."[102]

Wilson had said that the 1920 election would be a "great and solemn referendum" on the League of Nations, making it difficult for Cox to maneuver on the issue—although Roosevelt strongly supported the League, Cox was less enthusiastic.[103] Harding opposed entry into the League of Nations as negotiated by Wilson, but favored an "association of nations,"[25] based on the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. This was general enough to satisfy most Republicans, and only a few bolted the party over this issue. By October, Cox had realized there was widespread public opposition to Article X, and said that reservations to the treaty might be necessary; this shift allowed Harding to say no more on the subject.[104]

The RNC hired Albert Lasker, an advertising executive from Chicago, to publicize Harding, and Lasker unleashed a broad-based advertising campaign that used many now-standard advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign. Lasker's approach included newsreels and sound recordings. Visitors to Marion had their photographs taken with Senator and Mrs. Harding, and copies were sent to their hometown newspapers.[105] Billboard posters, newspapers and magazines were employed in addition to motion pictures. Telemarketers were used to make phone calls with scripted dialogues to promote Harding.[106]

During the campaign, opponents spread old rumors that Harding's great-great-grandfather was a West Indian black person and that other blacks might be found in his family tree.[107] Harding's campaign manager rejected the accusations. Wooster College professor William Estabrook Chancellor publicized the rumors, based on supposed family research, but perhaps reflecting no more than local gossip.[108]

By Election Day, November 2, 1920, few had any doubts that the Republican ticket would win.[109] Harding received 60.2 percent of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the evolution of the two-party system, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34 percent of the national vote and 127 electoral votes.[110] Campaigning from a federal prison where he was serving a sentence for opposing the war, Socialist Eugene V. Debs received 3 percent of the national vote. The Republicans greatly increased their majority in each house of Congress.[111][112]

Harding was inaugurated on March 4, 1921, in the presence of his wife and father. Harding preferred a subdued inauguration without the customary parade, leaving only the actual ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural address, he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."[113]

After the election, Harding announced that no decisions about appointments would be made until he returned from a vacation in December. He traveled to Texas, where he fished and played golf with his friend Frank Scobey (soon to be director of the Mint) and then sailed for the Panama Canal Zone. He visited Washington when Congress opened in early December, and he was afforded a hero's welcome as the first sitting senator to be elected to the White House.[e] Back in Ohio, Harding planned to consult with the country's best minds, who visited Marion to offer their counsel regarding appointments.[114][115]

Harding chose pro-League Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, ignoring the advice of Senator Lodge and others. After Charles G. Dawes declined the Treasury position, he chose Pittsburgh banker Andrew W. Mellon, one of the richest people in the country. He appointed Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce.[116] RNC chairman Will Hays was made Postmaster General, then a cabinet post; he left after a year in the position to become chief censor to the motion-picture industry.[117]

The two Harding cabinet appointees who darkened the reputation of his administration by their involvement in scandal were Harding's Senate friend Albert B. Fall of New Mexico, the Interior Secretary, and Daugherty, the attorney general. Fall was a Western rancher and former miner who favored development.[117] He was opposed by conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot, who wrote, "it would have been possible to pick a worse man for Secretary of the Interior, but not altogether easy."[118] The New York Times mocked the Daugherty appointment, writing that rather than selecting one of the best minds, Harding had been content "to choose merely a best friend."[119] Eugene P. Trani and David L. Wilson, in their volume on Harding's presidency, suggest that the appointment made sense then, as Daugherty was "a competent lawyer well-acquainted with the seamy side of politics ... a first-class political troubleshooter and someone Harding could trust."[120]

Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson's hands-on management of international affairs.[121] Hughes had to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the League of Nations, deciding the U.S. would not join even a scaled-down version of the League. With the Treaty of Versailles unratified by the Senate, the U.S. remained technically at war with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Peacemaking began with the Knox–Porter Resolution, declaring the U.S. at peace and reserving any rights granted under Versailles. Treaties with Germany, Austria and Hungary, each containing many of the non-League provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, were ratified in 1921.[122]

This still left the question of relations between the U.S. and the League. Hughes' State Department initially ignored communications from the League, or tried to bypass it through direct contacts with member nations. By 1922, though, the U.S., through its consul in Geneva, was dealing with the League, and though the U.S. refused to participate in any meeting with political implications, it sent observers to sessions on technical and humanitarian matters.[123]

By the time Harding took office, there were calls from foreign governments for reduction of the massive war debt owed to the United States, and the German government sought to reduce the reparations that it was required to pay. The U.S. refused to consider any multilateral settlement. Harding sought passage of a plan proposed by Mellon to give the administration broad authority to reduce war debts in negotiation, but Congress, in 1922, passed a more restrictive bill. Hughes negotiated an agreement for Britain to pay off its war debt over 62 years at low interest, reducing the present value of the obligations. This agreement, approved by Congress in 1923, served as a model for negotiations with other nations. Talks with Germany on reduction of reparations payments resulted in the Dawes Plan of 1924.[124]

A pressing issue not resolved by Wilson was U.S. policy towards Bolshevik Russia. The U.S. had been among the nations that sent troops there after the Russian Revolution. Afterwards, Wilson refused to recognize the Russian SFSR. Harding's Commerce Secretary Hoover, with considerable experience in Russian affairs, took the lead on policy. When famine struck Russia in 1921, Hoover had the American Relief Administration, which he had headed, negotiate with the Russians to provide aid. Leaders of the U.S.S.R. (established in 1922) hoped in vain that the agreement would lead to recognition. Hoover supported trade with the Soviets, fearing U.S. companies would be frozen out of the Soviet market, but Hughes opposed this, and the matter was not resolved under Harding's presidency.[125]

Harding urged disarmament and lower defense costs during the campaign, but it had not been a major issue. He gave a speech to a joint session of Congress in April 1921, setting out his legislative priorities. Among the few foreign policy matters he mentioned was disarmament; he said the government could not "be unmindful of the call for reduced expenditure" on defense.[126]

Idaho Senator William Borah had proposed a conference at which the major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, and Japan, would agree to cuts in their fleets. Harding concurred, and after diplomatic discussions, representatives of nine nations convened in Washington in November 1921. Most of the diplomats first attended Armistice Day ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery, where Harding spoke at the entombment of the Unknown Soldier of World War I, whose identity, "took flight with his imperishable soul. We know not whence he came, only that his death marks him with the everlasting glory of an American dying for his country."[127]

Hughes, in his speech at the opening session of the conference on November 12, 1921, made the American proposal—the U.S. would decommission or not build 30 warships if Great Britain did likewise for 19 vessels, and Japan for 17.[128] Hughes was generally successful, with agreements reached on this and other points, including settlement of disputes over islands in the Pacific, and limitations on the use of poison gas. The naval agreement applied only to battleships, and to some extent aircraft carriers, and ultimately did not prevent rearmament. Nevertheless, Harding and Hughes were widely applauded in the press for their work. Senator Lodge and the Senate Minority Leader, Alabama's Oscar Underwood, were part of the U.S. delegation, and they helped ensure the treaties made it through the Senate mostly unscathed, though that body added reservations to some.[129][130]

The U.S. had acquired over a thousand vessels during World War I, and still owned most of them when Harding took office. Congress had authorized their disposal in 1920, but the Senate would not confirm Wilson's nominees to the Shipping Board. Harding appointed Albert Lasker as its chairman; the advertising executive undertook to run the fleet as profitably as possible until it could be sold. Few ships were marketable at anything approaching the government's cost. Lasker recommended a large subsidy to the merchant marine to facilitate sales, and Harding repeatedly urged Congress to enact it. The resulting bill was unpopular in the Midwest, and though it passed the House, it was defeated by a filibuster in the Senate, and most government ships were eventually scrapped.[131]

Intervention in Latin America had been a minor campaign issue, though Harding spoke against Wilson's decision to send U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and attacked the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Franklin Roosevelt, for his role in the Haitian intervention. Once Harding was sworn in, Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries who were wary of the American use of the Monroe Doctrine to justify intervention; at the time of Harding's inauguration, the U.S. also had troops in Cuba and Nicaragua. The troops stationed in Cuba were withdrawn in 1921, but U.S. forces remained in the other three nations throughout Harding's presidency.[f][132] In April 1921, Harding gained the ratification of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia, granting that nation $25 million (equivalent to $427.05 million in 2023) as settlement for the U.S.-provoked Panamanian revolution of 1903.[133] The Latin American nations were not fully satisfied, as the U.S. refused to renounce interventionism, though Hughes pledged to limit it to nations near the Panama Canal, and to make it clear what the U.S. aims were.[134]

The U.S. had intervened repeatedly in Mexico under Wilson, and had withdrawn diplomatic recognition, setting conditions for reinstatement. The Mexican government under President Álvaro Obregón wanted recognition before negotiations, but Wilson and his final Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby, refused. Both Hughes and Fall opposed recognition; Hughes instead sent a draft treaty to the Mexicans in May 1921, which included pledges to reimburse Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution there. Obregón was unwilling to sign a treaty before being recognized, and worked to improve the relationship between American business and Mexico, reaching agreement with creditors, and mounting a public relations campaign in the United States. This had its effect, and by mid-1922, Fall was less influential than he had been, lessening the resistance to recognition. The two presidents appointed commissioners to reach a deal, and the U.S. recognized the Obregón government on August 31, 1923, just under a month after Harding's death, substantially on the terms proffered by Mexico.[135]

When Harding took office on March 4, 1921, the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline.[136] At the suggestion of legislative leaders, Harding called a special session of Congress, to convene April 11. When Harding addressed the joint session the following day, he urged the reduction of income taxes (raised during the war), an increase in tariffs on agricultural goods to protect the American farmer, as well as more wide-ranging reforms, such as support for highways, aviation, and radio.[137][138] It was not until May 27 that Congress passed an emergency tariff increase on agricultural products. An act authorizing a Bureau of the Budget followed on June 10, and Harding appointed Charles Dawes as bureau director with a mandate to cut expenditures.[139]

Treasury Secretary Mellon also recommended that Congress cut income tax rates, and that the corporate excess profits tax be abolished. The House Ways and Means Committee endorsed Mellon's proposals, but some congressmen wanting to raise corporate tax rates fought the measure. Harding was unsure what side to endorse, telling a friend, "I can't make a damn thing out of this tax problem. I listen to one side, and they seem right, and then—God!—I talk to the other side, and they seem just as right."[138] Harding tried compromise, and gained passage of a bill in the House after the end of the excess profits tax was delayed a year. In the Senate, the bill became entangled in efforts to vote World War I veterans a soldier's bonus. Frustrated by the delays, on July 12, Harding appeared before the Senate to urge passage of the tax legislation without the bonus. It was not until November that the revenue bill finally passed, with higher rates than Mellon had proposed.[140][141]

In opposing the veterans' bonus, Harding argued in his Senate address that much was already being done for them by a grateful nation, and that the bill would "break down our Treasury, from which so much is later on to be expected".[142] The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee, but the issue returned when Congress reconvened in December 1921.[142] A bill providing a bonus, though unfunded, was passed by both houses in September 1922, but Harding's veto was narrowly sustained. A non-cash bonus for soldiers passed over Coolidge's veto in 1924.[143]

In his first annual message to Congress, Harding sought the power to adjust tariff rates. The passage of the tariff bill in the Senate, and in conference committee became a feeding frenzy of lobby interests.[144] When Harding signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act on September 21, 1922, he made a brief statement, praising the bill only for giving him some power to change rates.[145] According to Trani and Wilson, the bill was "ill-considered. It wrought havoc in international commerce and made the repayment of war debts more difficult."[146]

Mellon ordered a study that demonstrated historically that, as income tax rates were increased, money was driven underground or abroad, and he concluded that lower rates would increase tax revenues.[147][148] Based on his advice, Harding's revenue bill cut taxes, starting in 1922. The top marginal rate was reduced annually in four stages from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were cut for lower incomes starting in 1923, and the lower rates substantially increased the money flowing to the treasury. They also pushed massive deregulation, and federal spending as a share of GDP fell from 6.5% to 3.5%. By late 1922, the economy began to turn around. Unemployment was pared from its 1921 high of 12% to an average of 3.3% for the remainder of the decade. The misery index, a combined measure of unemployment and inflation, had its sharpest decline in U.S. history under Harding. Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains; annual GDP increases averaged at over 5% during the 1920s. Libertarian historians Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen argue that, "Mellon's tax policies set the stage for the most amazing growth yet seen in America's already impressive economy."[149]

The 1920s were a time of modernization for America—use of electricity became increasingly common. Mass production of motorized vehicles stimulated other industries as well, such as highway construction, rubber, steel, and building, as hotels were erected to accommodate the tourists venturing upon the roads. This economic boost helped bring the nation out of the recession.[150] To improve and expand the nation's highway system, Harding signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921. From 1921 to 1923, the federal government spent $162 million (equivalent to $2.9 billion in 2023) on America's highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.[151] In 1922, Harding proclaimed that America was in the age of the "motor car", which "reflects our standard of living and gauges the speed of our present-day life".[152]

Harding urged regulation of radio broadcasting in his April 1921 speech to Congress.[153] Commerce Secretary Hoover took charge of this project, and convened a conference of radio broadcasters in 1922, which led to a voluntary agreement for licensing of radio frequencies through the Commerce Department. Both Harding and Hoover realized something more than an agreement was needed, but Congress was slow to act, not imposing radio regulation until 1927.[154]

Harding also wished to promote aviation, and Hoover again took the lead, convening a national conference on commercial aviation. The discussions focused on safety matters, inspection of airplanes, and licensing of pilots. Harding again promoted legislation but nothing was done until 1926, when the Air Commerce Act created the Bureau of Aeronautics within Hoover's Commerce Department.[154]

Harding's attitude toward business was that government should aid it as much as possible.[155] He was suspicious of organized labor, viewing it as a conspiracy against business.[156] He sought to get them to work together at a conference on unemployment that he called to meet in September 1921 at Hoover's recommendation. Harding warned in his opening address that no federal money would be available. No important legislation came as a result, though some public works projects were accelerated.[157]

Within broad limits, Harding allowed each cabinet secretary to run his department as he saw fit.[158] Hoover expanded the Commerce Department to make it more useful to business. This was consistent with Hoover's view that the private sector should take the lead in managing the economy.[159] Harding greatly respected his Commerce Secretary, often asked his advice, and backed him to the hilt, calling Hoover "the smartest 'gink' I know".[160]

Widespread strikes marked 1922, as labor sought redress for falling wages and increased unemployment. In April, 500,000 coal miners, led by John L. Lewis, struck over wage cuts. Mining executives argued that the industry was seeing hard times; Lewis accused them of trying to break the union. As the strike became protracted, Harding offered compromise to settle it. As Harding proposed, the miners agreed to return to work, and Congress created a commission to look into their grievances.[161]

On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers went on strike. Harding recommended a settlement that made some concessions, but management objected. Attorney General Daugherty convinced Judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a sweeping injunction to break the strike. Although there was public support for the Wilkerson injunction, Harding felt it went too far, and had Daugherty and Wilkerson amend it. The injunction succeeded in ending the strike; however, tensions remained high between railroad workers and management for years.[162]

By 1922, the eight-hour day had become common in American industry. One exception was in steel mills, where workers labored through a twelve-hour workday, seven days a week. Hoover considered this practice barbaric and got Harding to convene a conference of steel manufacturers with a view to ending the system. The conference established a committee under the leadership of U. S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary, which in early 1923 recommended against ending the practice. Harding sent a letter to Gary deploring the result, which was printed in the press, and public outcry caused the manufacturers to reverse themselves and standardize the eight-hour day.[163]

Although Harding's first address to Congress called for passage of anti-lynching legislation,[10] he initially seemed inclined to do no more for African Americans than Republican presidents of the recent past had; he asked Cabinet officers to find places for blacks in their departments. Sinclair suggested that the fact that Harding received two-fifths of the Southern vote in 1920 led him to see political opportunity for his party in the Solid South. On October 26, 1921, Harding gave a speech in Birmingham, Alabama, to a segregated audience of 20,000 Whites and 10,000 Blacks. Harding, while saying that the social and racial differences between Whites and Blacks could not be bridged, urged equal political rights for the latter. Many African-Americans at that time voted Republican, especially in the Democratic South, and Harding said he did not mind seeing that support end if the result was a strong two-party system in the South. He was willing to see literacy tests for voting continue, if applied fairly to White and Black voters.[164] "Whether you like it or not," Harding told his segregated audience, "unless our democracy is a lie, you must stand for that equality."[10] The White section of the audience listened in silence, while the Black section cheered.[165] Three days after the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, Harding spoke at the all-Black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He declared, "Despite the demagogues, the idea of our oneness as Americans has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group. And so, I wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races." Speaking directly about the events in Tulsa, he said, "God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it."[166]

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer's federal anti-lynching bill, which passed the House of Representatives in January 1922.[167] When it reached the Senate floor in November 1922, it was filibustered by Southern Democrats, and Lodge withdrew it to allow the ship subsidy bill Harding favored to be debated, though it was likewise blocked. Blacks blamed Harding for the Dyer bill's defeat; Harding biographer Robert K. Murray noted that it was hastened to its end by Harding's desire to have the ship subsidy bill considered.[168]

With the public suspicious of immigrants, especially those who might be socialists or communists, Congress passed the Per Centum Act of 1921, signed by Harding on May 19, 1921, as a quick means of restricting immigration. The act reduced the numbers of immigrants to 3% of those from a given country living in the U.S., based on the 1910 census. This would, in practice, not restrict immigration from Ireland and Germany, but would bar many Italians and eastern European Jews.[169] Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed that enforcement had to be humane, and at the Secretary's recommendation, Harding allowed almost 1,000 deportable immigrants to remain.[170] Coolidge later signed the Immigration Act of 1924, permanently restricting immigration to the U.S.[171]

Harding's Socialist opponent in the 1920 election, Eugene Debs, was serving a ten-year sentence in the Atlanta Penitentiary for speaking against the war. Wilson had refused to pardon him before leaving office. Daugherty met with Debs, and was deeply impressed. There was opposition from veterans, including the American Legion, and also from Florence Harding. The president did not feel he could release Debs until the war was officially over, but once the peace treaties were signed, commuted Debs' sentence on December 23, 1921. At Harding's request, Debs visited the president at the White House before going home to Indiana.[172]

Harding released 23 other war opponents at the same time as Debs, and continued to review cases and release political prisoners throughout his presidency. Harding defended his prisoner releases as necessary to return the nation to normalcy.[173]

Harding appointed four justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. When Chief Justice Edward Douglass White died in May 1921, Harding was unsure whether to appoint former president Taft or former Utah senator George Sutherland—he had promised seats on the court to both men. After briefly considering awaiting another vacancy and appointing them both, he chose Taft as Chief Justice. Sutherland was appointed to the court in 1922, to be followed by two other economic conservatives, Pierce Butler and Edward Terry Sanford, in 1923.[174]

Harding also appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 42 judges to the United States district courts, and two judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals.[175]

Entering the 1922 midterm congressional election campaign, Harding and the Republicans had followed through on many of their campaign promises. But some of the fulfilled pledges, like cutting taxes for the well-off, did not appeal to the electorate. The economy had not returned to normalcy, with unemployment at 11 percent, and organized labor angry over the outcome of the strikes. From 303 Republicans elected to the House in 1920, the new 68th Congress saw that party fall to a 221–213 majority. In the Senate, the Republicans lost eight seats, and had 51 of 96 senators in the new Congress, which Harding did not survive to meet.[176]

A month after the election, the lame-duck session of the outgoing 67th Congress met. Harding then believed his early view of the presidency—that it should propose policies, but leave their adoption to Congress—was no longer enough, and he lobbied Congress, although in vain, to get his ship subsidy bill through.[176] Once Congress left town in early March 1923, Harding's popularity began to recover. The economy was improving, and the programs of Harding's more able Cabinet members, such as Hughes, Mellon and Hoover, were showing results. Most Republicans realized that there was no practical alternative to supporting Harding in 1924 for his re-election campaign.[177]

In the first half of 1923, Harding did two things that were later said to indicate foreknowledge of death: he sold the Star (though undertaking to remain as a contributing editor for ten years after his presidency), and he made a new will.[178] Harding had long suffered occasional health problems, but when he was not experiencing symptoms, he tended to eat, drink and smoke too much. By 1919, he was aware he had a heart condition. Stress caused by the presidency and by Florence Harding's own chronic kidney condition debilitated him, and he never fully recovered from an episode of influenza in January 1923. After that, Harding, an avid golfer, had difficulty completing a round. In June 1923, Ohio Senator Willis met with Harding, but brought to the president's attention only two of the five items he intended to discuss. When asked why, Willis responded, "Warren seemed so tired."[179]

In early June 1923, Harding set out on a journey, which he dubbed the "Voyage of Understanding".[177] The president planned to cross the country, go north to Alaska Territory, journey south along the West Coast, then travel by a U.S. Navy ship from San Diego along the Mexican and Central America West Coast, through the Panama Canal, to Puerto Rico, and return to Washington at the end of August.[180] Harding loved to travel and had long contemplated a trip to Alaska.[181] The trip would allow him to speak widely across the country, to politic and bloviate in advance of the 1924 campaign, and give him some rest[182] away from Washington's oppressive summer heat.[177]

Harding's political advisers had given him a physically demanding schedule, even though the president had ordered it cut back.[183] In Kansas City, Harding spoke on transportation issues; in Hutchinson, Kansas, agriculture was the theme. In Denver, he spoke on his support of Prohibition, and continued west making a series of speeches not matched by any president until Franklin Roosevelt. Harding had become a supporter of the World Court, and wanted the U.S. to become a member. In addition to making speeches, he visited Yellowstone and Zion National Parks,[184] and dedicated a monument on the Oregon Trail at a celebration organized by venerable pioneer Ezra Meeker and others.[185]

On July 5, Harding embarked on USS Henderson in Washington state. He was the first president to visit Alaska, and spent hours watching the dramatic landscapes from the deck of the Henderson.[186] After several stops along the coast, the presidential party left the ship at Seward to take the Alaska Railroad to McKinley Park and Fairbanks, where he addressed a crowd of 1,500 in 94 °F (34 °C) heat. The party was to return to Seward by the Richardson Trail, but due to Harding's fatigue, they went by train.[187]

On July 26, 1923, Harding toured Vancouver, British Columbia as the first sitting American president to visit Canada. He was welcomed by the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Walter Nichol,[188] Premier of British Columbia John Oliver, and the Mayor of Vancouver, and spoke to a crowd of over 50,000. Two years after his death, a memorial to Harding was unveiled in Stanley Park.[189] Harding visited a golf course, but completed only six holes before becoming fatigued. After resting for an hour, he played the 17th and 18th holes so it would appear he had completed the round. He did not succeed in hiding his exhaustion; one reporter thought he looked so tired that a rest of mere days would be insufficient to refresh him.[190]

In Seattle the next day, Harding kept up his busy schedule, giving a speech to 25,000 people at the stadium at the University of Washington. In the final speech he gave, Harding predicted statehood for Alaska.[191][192] The president rushed through his speech, not waiting for applause from the audience.[193]

Harding went to bed early the evening of July 27, 1923, a few hours after giving the speech at the University of Washington. Later that night, he called for his physician Charles E. Sawyer, complaining of pain in the upper abdomen. Sawyer thought that it was a recurrence of stomach upset, but Dr. Joel T. Boone suspected a heart problem. The press was told Harding had experienced an "acute gastrointestinal attack" and his scheduled weekend in Portland was cancelled. He felt better the next day, as the train rushed to San Francisco, where they arrived the morning of July 29. He insisted on walking from the train to the car, and was then rushed to the Palace Hotel,[194][195] where he suffered a relapse. Doctors found that not only was his heart causing problems, but also that he had pneumonia, and he was confined to bed rest in his hotel room. Doctors treated him with liquid caffeine and digitalis, and he seemed to improve. Hoover released Harding's foreign policy address advocating membership in the World Court, and the president was pleased that it was favorably received. By the afternoon of August 2, Harding's condition still seemed to be improving and his doctors allowed him to sit up in bed. At around 7:30 that evening, Florence was reading to him "A Calm Review of a Calm Man", a flattering article about him from The Saturday Evening Post; she paused and he told her, "That's good. Go on, read some more." Those were to be his last words. She resumed reading when, a few seconds later, Harding twisted convulsively and collapsed back in the bed, gasping. Florence Harding immediately called the doctors into the room, but they were unable to revive him with stimulants. Harding was pronounced dead a few minutes later, at the age of 57.[196] Harding's death was initially attributed to a cerebral hemorrhage, as doctors at the time did not generally understand the symptoms of cardiac arrest. Florence Harding did not consent to have the president autopsied.[25][194]

Harding's unexpected death came as a great shock to the nation. He was liked and admired, both the press and public had followed his illness closely, and had been reassured by his apparent recovery.[197] Harding's body was carried to his train in a casket for a journey across the nation, which was followed closely in the newspapers. Nine million people lined the railroad tracks as the train carrying his body proceeded from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., where he lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda. After funeral services there, Harding's body was transported to Marion, Ohio, for burial.[198]

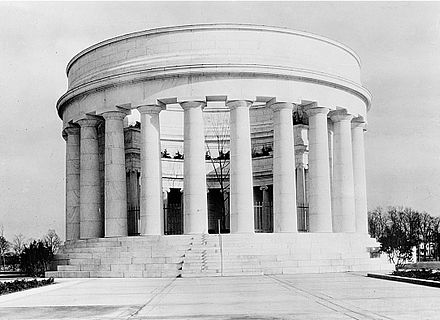

In Marion, Harding's body was placed on a horse-drawn hearse, which was followed by President Coolidge and Chief Justice Taft, then by Harding's widow and his father.[199] They followed the hearse through the city, past the Star building and finally to the Marion Cemetery where the casket was placed in the cemetery's receiving vault.[200][201] Funeral guests included inventor Thomas Edison and industrialist businessmen Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone.[202] Warren Harding and Florence Harding, who died the following year, rest in the Harding Tomb, which was dedicated in 1931 by U.S. President Herbert Hoover.[203]

Harding appointed friends and acquaintances to federal positions. Some served competently, such as Charles E. Sawyer, the Hardings' personal physician from Marion who attended to them in the White House, and alerted Harding to the Veterans' Bureau scandal. Others proved ineffective in office, such as Daniel R. Crissinger, a Marion lawyer whom Harding made Comptroller of the Currency and later a governor of the Federal Reserve Board; another was Harding's old friend Frank Scobey, Director of the Mint, who Trani and Wilson noted "did little damage during his tenure." Still others of these associates proved corrupt and were later dubbed the "Ohio Gang."[204]

Most of the scandals that have marred the reputation of Harding's administration did not emerge until after his death. The Veterans' Bureau scandal was known to Harding in January 1923 but, according to Trani and Wilson, "the president's handling of it did him little credit."[205] Harding allowed the corrupt director of the bureau, Charles R. Forbes, to flee to Europe, though he later returned and served prison time.[206] Harding had learned that Daugherty's factotum at the Justice Department, Jess Smith, was involved in corruption. The president ordered Daugherty to get Smith out of Washington and removed his name from the upcoming presidential trip to Alaska. Smith committed suicide on May 30, 1923.[207] It is uncertain how much Harding knew about Smith's illicit activities.[208] Murray noted that Harding was not involved in the corruption and did not condone it.[209]

Hoover accompanied Harding on the Western trip and later wrote that Harding asked what Hoover would do if he knew of some great scandal, whether to publicize it or bury it. Hoover replied that Harding should publish and get credit for integrity, and asked for details. Harding said that it had to do with Smith but, when Hoover enquired as to Daugherty's possible involvement, Harding refused to answer.[210]