Karate (空手) ( / k ə ˈ r ɑː t i / ; Pronunciación japonesa: [kaɾate] Karate-do(空手道, Karate-dō )es unarte marcialdesarrollado en elReino Ryukyu. Se desarrolló a partir de lasartes marciales indígenas de Ryukyu(llamadaste(手), "mano"; enokinawense )bajo la influencia delasartesmarciales chinas.[1][2]Mientras queel Karate modernounarte de golpeo que utiliza puñetazos y patadas, el karate tradicional también empleatécnicasde lanzamientoybloqueo de articulaciones[3]Un practicante de karate se llamakarate-ka(空手家).

A partir del siglo XIV, los primeros artistas marciales chinos trajeron sus técnicas a Okinawa. A pesar de que el Reino de Ryukyu fue convertido en un estado títere por los samuráis japoneses en 1609, después de la Invasión de Ryukyu , sus lazos culturales con China siguieron siendo fuertes. [4] Dado que a los okinawenses se les prohibió llevar espadas bajo el gobierno samurái, grupos clandestinos de jóvenes aristócratas crearon métodos de combate sin armas como una forma de resistencia, combinando estilos locales y chinos. [4] Esta mezcla de artes marciales se conoció como kara-te唐手, que se traduce como "mano china". Inicialmente, no había uniformes, cinturones de colores, sistemas de clasificación o estilos estandarizados. [4] El entrenamiento enfatizaba la autodisciplina. [4] Muchos elementos esenciales del karate se incorporaron hace un siglo. [4]

El Reino de Ryukyu había sido conquistado por el Dominio Satsuma japonés y se había convertido en su estado vasallo desde 1609, pero fue anexado formalmente al Imperio de Japón en 1879 como Prefectura de Okinawa . Los samuráis de Ryukyu ( okinawense : samurē ) que habían sido los portadores del karate perdieron su posición privilegiada y, con ella, el karate estuvo en peligro de perder la transmisión. Sin embargo, el karate recuperó gradualmente su popularidad después de 1905, cuando comenzó a enseñarse en las escuelas de Okinawa. Durante la era Taishō (1912-1926), el karate fue introducido en el Japón continental por Gichin Funakoshi y Motobu Chōki . El sentimiento ultranacionalista de la década de 1930 afectó a todos los aspectos de la cultura japonesa. [4] Para hacer que el arte marcial importado fuera más identificable, Funakoshi incorporó elementos del judo , como los uniformes de entrenamiento, los cinturones de colores y los sistemas de clasificación. [4] La popularidad del Karate fue inicialmente lenta y con poca exposición, pero cuando una revista publicó una historia sobre Motobu derrotando a un boxeador extranjero en Kioto, el Karate rápidamente se hizo conocido en todo Japón. [5]

En esta era de creciente militarismo japonés , [6] el nombre fue cambiado de唐手("mano china" o " mano Tang ") [7] a空手("mano vacía") - ambos se pronuncian karate en japonés - para indicar que los japoneses deseaban desarrollar la forma de combate al estilo japonés. [8] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Okinawa se convirtió (1945) en un importante sitio militar de los Estados Unidos y el karate se hizo popular entre los militares estacionados allí. [9] [10] Las películas de artes marciales de los años 1960 y 1970 sirvieron para aumentar enormemente la popularidad de las artes marciales en todo el mundo, y los angloparlantes comenzaron a usar la palabra karate de manera genérica para referirse a todas las artes marciales asiáticas basadas en golpes . [11] Las escuelas de karate ( dōjōs ) comenzaron a aparecer en todo el mundo, atendiendo a aquellos con interés casual, así como a aquellos que buscaban un estudio más profundo del arte.

El karate, al igual que otras artes marciales japonesas, se considera que no solo se trata de técnicas de lucha, sino también de cultivo espiritual. [12] [13] Muchas escuelas de karate y dōjōs han establecido reglas llamadas dōjō kun , que enfatizan la perfección del carácter, la importancia del esfuerzo y el respeto por la cortesía. El karate se presentó en los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2020 después de que su inclusión en los Juegos fuera apoyada por el Comité Olímpico Internacional . Web Japan (patrocinado por el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Japón ) afirma que el karate tiene 50 millones de practicantes en todo el mundo, [14] mientras que la Federación Mundial de Karate afirma que hay 100 millones de practicantes en todo el mundo. [15]

Originalmente en Okinawa durante el período del Reino Ryukyu, existía un arte marcial indígena Ryukyuan llamado te (Okinawense: tī , lit. ' mano ' ). Además, en el siglo XIX, surgió un arte marcial derivado de China llamado tōde (Okinawense: tōdī , lit. ' mano Tang ' ). Según Gichin Funakoshi, existía una distinción entre Okinawan-te y tōde a fines del siglo XIX. [16] Con la aparición de tōde , se cree que te también pasó a llamarse Okinawa-te (Okinawa: Uchinādī , lit. ' mano de Okinawa ' ). Sin embargo, esta distinción se volvió gradualmente borrosa con el declive de Okinawa-te .

Alrededor de 1905, cuando el karate comenzó a enseñarse en las escuelas públicas de Okinawa, tōde se leía kun'yomi y se llamaba karate (唐手, lit. ' mano Tang ' ) al estilo japonés. Tanto tōde como karate se escriben con los mismos caracteres chinos que significan "mano Tang/China", pero el primero es on'yomi (lectura china) y el segundo es kun'yomi (lectura japonesa). Dado que la distinción entre Okinawa-te y tōde ya estaba borrosa en ese momento, el karate se usó para abarcar ambos. "Kara (から)" es un kun'yomi para el carácter "唐" (tō/とう en on'yomi ) que se deriva de " Confederación Gaya (加羅)" y más tarde incluyó cosas derivadas de China (específicamente de la dinastía Tang ). [17] Por lo tanto, tōde y karate (mano Tang) difieren en el alcance del significado de las palabras. [18]

Japón envió enviados a la dinastía Tang e introdujo gran parte de la cultura china. Gichin Funakoshi propuso que tōde /karate podría haber sido usado en lugar de te , ya que Tang se convirtió en sinónimo de bienes de lujo importados. [19]

Según Gichin Funakoshi, la palabra pronunciada karate (から手) existía en el período del Reino Ryukyu, pero no está claro si significaba mano Tang (唐手) o mano vacía (空手) . [20]

Los orígenes chinos del karate fueron vistos cada vez con más recelo debido a las crecientes tensiones entre China y Japón y también a la amenaza inminente de una guerra a gran escala entre los dos países. [4] En 1933, el carácter japonés para karate fue alterado por un homófono, una palabra que se pronuncia de manera idéntica pero con un significado diferente. Por lo tanto, "mano china" fue reemplazada por "mano vacía". [4]

Pero este cambio de nombre no se extendió inmediatamente entre los practicantes de karate de Okinawa. Hubo muchos practicantes de karate, como Chōjun Miyagi , que todavía usaban te en la conversación cotidiana hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [21]

Cuando el karate se enseñó por primera vez en Japón continental en la década de 1920, Gichin Funakoshi y Motobu Chōki utilizaron el nombre karate-jutsu (唐手術, lit. ' arte de la mano Tang ' ) junto con karate. [22] [23] La palabra jutsu (術) significa arte o técnica, y en aquellos días se usaba a menudo como sufijo del nombre de cada arte marcial, como en jujutsu y kenjutsu (esgrima). [24]

El primer uso documentado de un homófono del logograma pronunciado kara , reemplazando el carácter chino que significa "dinastía Tang" por el carácter que significa "vacío", tuvo lugar en Karate Kumite (空手組手), escrito en agosto de 1905 por Chōmo Hanashiro (1869-1945). [25] En Japón continental, el karate (空手, mano vacía) comenzó a usarse gradualmente a partir de los escritos de Gichin Funakoshi y Motobu Chōki en la década de 1920. [26] [27]

En 1929, el Grupo de Estudio de Karate de la Universidad de Keio (instructor Gichin Funakoshi) utilizó este término en referencia al concepto de vacío del Sutra del Corazón , y esta terminología se popularizó más tarde, especialmente en Tokio. También existe la teoría de que el motivo de este cambio de nombre fue el empeoramiento de las relaciones entre Japón y China en ese momento. [28]

El 25 de octubre de 1936 se celebró una mesa redonda de maestros de karate en Naha, prefectura de Okinawa, y se resolvió oficialmente utilizar el nombre karate (mano vacía) en el sentido de kūshu kūken (空手空拳, lit. ' sin nada en las manos o los puños ' ). [29] Para conmemorar este día, la Asamblea de la Prefectura de Okinawa aprobó una resolución en 2005 para decidir el 25 de octubre como el "Día del Karate". [30]

Otro desarrollo nominal es la adición de dō (道;どう) al final de la palabra karate. Dō es un sufijo que tiene numerosos significados, incluidos camino, sendero, ruta y vía. [31] Se utiliza en muchas artes marciales que sobrevivieron a la transición de Japón de la cultura feudal a los tiempos modernos . Implica que estas artes no son solo sistemas de lucha, sino que contienen elementos espirituales cuando se promueven como disciplinas. [32] En este contexto, dō generalmente se traduce como "el camino de ..." Los ejemplos incluyen aikido , judo, kyūdō y kendo . Por lo tanto, karatedō es más que solo técnicas de mano vacía. Es "el camino de la mano vacía". [33]

Desde la década de 1980, el término karate (カラテ) se escribe en katakana en lugar de caracteres chinos, principalmente por Kyokushin Karate (fundador: Masutatsu Oyama ). [34] En Japón, el katakana se utiliza principalmente para palabras extranjeras, lo que le da al Kyokushin Karate una impresión moderna y nueva.

Existen varias teorías sobre los orígenes del karate, pero las principales son las siguientes.

En Okinawa existía una antigua danza marcial llamada mēkata (舞方). Los bailarines bailaban acompañados de canciones y música sanshin , similar al kata de karate. En la campiña de Okinawa, el mēkata se mantuvo hasta principios del siglo XX. Existe una teoría de que de este mēkata con elementos marciales nació el te (okinawense: tī , mano) y se desarrolló hasta convertirse en karate. Esta teoría es defendida por Ankō Asato y su alumno Gichin Funakoshi. [35]

Se dice que en 1392 un grupo de profesionales conocidos como las " Treinta y seis familias de Min " emigraron a la aldea de Kume (ahora Kume, ciudad de Naha) en Naha desde la provincia de Fujian durante la dinastía Ming en ese momento. Trajeron consigo conocimientos y habilidades avanzadas a Ryukyu, y existe la teoría de que el kenpō chino, el origen del karate, también llegó a Ryukyu en esa época.

También existe la " teoría de la importación de Keichō ", que afirma que el karate fue traído a Ryukyu después de la invasión de Ryukyu por el Dominio Satsuma (Keichō 14, 1609), así como la teoría de que fue introducido por Kōshōkun (Okinawa: Kūsankū) basado en la descripción en Ōshima Writing . [36]

También existen otras teorías, como que se desarrolló a partir del sumo de Okinawa ( shima ) o que se originó a partir del jujutsu , que había sido introducido desde Japón. [37]

La razón para el desarrollo de técnicas de combate sin armas en Ryukyu se ha atribuido convencionalmente a una política de prohibición de armas, que se dice que se implementó en dos ocasiones. La primera fue durante el reinado del rey Shō Shin (1476-1526; r. 1477-1527), cuando se recogieron armas de todo el país y fueron estrictamente controladas por el gobierno real. La segunda vez fue después de la invasión de Ryukyu por el Dominio Satsuma en 1609. A través de las dos políticas, la creencia popular de que los samuráis de Ryukyu, que fueron privados de sus armas, desarrollaron el karate para competir con los samuráis de Satsuma se ha mencionado tradicionalmente como si fuera un hecho histórico. [38]

Sin embargo, en los últimos años muchos investigadores han cuestionado la relación causal entre la política de prohibición de armas y el desarrollo del karate. [39] Por ejemplo, como base de la política de prohibición de armas del rey Shō Shin, una inscripción en el parapeto del salón principal del castillo de Shuri (百浦添欄干之銘, 1509), que establece que "las espadas, los arcos y las flechas deben apilarse exclusivamente como armas de defensa nacional", [40] se ha interpretado convencionalmente como que significa "las armas se recogían y sellaban en un almacén". Sin embargo, en los últimos años, los investigadores de los estudios de Okinawa han señalado que la interpretación correcta es que "las espadas, los arcos y las flechas se recogían y se usaban como armas del estado". [41]

También se sabe que la política de prohibición de armas (un aviso de 1613 al gobierno real de Ryukyu), que se dice que fue implementada por el Dominio Satsuma, solo prohibía llevar espadas y otras armas, pero no su posesión, y era una regulación relativamente laxa. Este aviso establecía: "(1) La posesión de armas está prohibida. (2) La posesión de armas propiedad privada de príncipes, tres magistrados y samuráis está permitida. (3) Las armas deben repararse en Satsuma a través de la oficina del magistrado de Satsuma. (4) Las espadas deben informarse a la oficina del magistrado de Satsuma para su aprobación". [42] No prohibía la posesión de armas (excepto pistolas) ni siquiera su práctica. De hecho, incluso después de la subyugación al Dominio Satsuma, se sabe de varios maestros ryukyuanos de esgrima, lanza, tiro con arco y otras artes. Por ello, algunos investigadores critican la teoría de que el karate se desarrolló debido a la política de prohibición de armas como "un rumor en la calle sin fundamento alguno". [43]

El karate comenzó como un sistema de lucha común conocido como te (Okinawa: tī ) entre la clase samurái de Ryukyu. Había pocos estilos formales de te, pero muchos practicantes con sus propios métodos. Un ejemplo sobreviviente es Motobu Udundī ( lit. ' Mano del Palacio Motobu ' ), que se ha transmitido hasta el día de hoy en la familia Motobu, una de las ramas de la antigua familia real de Ryukyu. [44] En el siglo XVI, el libro de historia de Ryukyu " Kyūyō " (球陽, establecido alrededor de 1745) menciona que Kyō Ahagon Jikki [ja] , un sirviente favorito del rey Shō Shin, usó un arte marcial llamado "karate" (空手, lit. ' mano vacía ' ) para aplastar ambas piernas de un asesino. Se cree que este karate se refiere al te , no al karate actual, y Ankō Asato presenta a Kyō Ahagon como un "artista marcial destacado". [35]

Sin embargo, algunos creen que la anécdota de Kyō Ahagon es una media leyenda y que no está claro si en realidad era un maestro del te . En el siglo XVIII, los nombres de Nishinda Uēkata , Gushikawa Uēkata y Chōken Makabe son conocidos como maestros del te . [45]

Nishinda Uēkata y Gushikawa Uēkata fueron artistas marciales activos durante el reinado del rey Shō Kei (reinó entre 1713 y 1751). Nishinda Uēkata era bueno con la lanza y el te , y Gushikawa Uēkata también era bueno con la espada de madera (esgrima). [46]

Chōken Makabe fue un hombre de finales del siglo XVIII. Su estatura baja y su habilidad para saltar le valieron el apodo de "Makabe Chān-gwā " ( literalmente, " pequeño gallo de pelea " ), ya que era como un chān (gallo de pelea). Se dice que el techo de su casa estaba marcado por su pie al patear. [47]

Se sabe que en "Ōshima Writing" (1762), escrito por Yoshihiro Tobe, un erudito confuciano del Dominio de Tosa , que entrevistó a samuráis de Ryukyu que habían llegado a Tosa (actual prefectura de Kōchi ), hay una descripción de un arte marcial llamado kumiai-jutsu (組合術) realizado por Kōshōkun (Okinawa: Kūsankū). Se cree que Kōshōkun puede haber sido un oficial militar en una misión de Qing que visitó Ryukyu en 1756, y algunos creen que el karate se originó con Kōshōkun.

Además, el testamento (Parte I: 1778, Parte II: 1783) del samurái de Ryukyuan Aka Pēchin Chokushki (1721-1784) menciona el nombre de un arte marcial llamado karamutō (からむとう), junto con la esgrima japonesa Jigen-ryū y el jujutsu , lo que indica que los samuráis de Ryukyuan practicaban estas artes en el siglo XVIII. [48]

En 1609, el Dominio Satsuma japonés invadió Ryukyu y este se convirtió en su estado vasallo, pero continuó pagando tributo a las dinastías Ming y Qing en China. En ese momento, China había implementado una política de prohibición marítima y solo comerciaba con países tributarios, por lo que el Dominio Satsuma quería que Ryukyu continuara pagando tributo para beneficiarse de él.

Los enviados de la misión de tributo fueron elegidos entre la clase samurái de Ryukyu, y fueron a Fuzhou en Fujian y permanecieron allí entre seis meses y un año y medio. También se enviaron estudiantes extranjeros financiados por el gobierno y por fondos privados a estudiar en Beijing o Fuzhou durante varios años. Algunos de estos enviados y estudiantes estudiaron artes marciales chinas en China. Los estilos de artes marciales chinas que estudiaron no se conocen con certeza, pero se supone que estudiaron la Grulla Blanca de Fujian y otros estilos de la provincia de Fujian.

Sōryo Tsūshin (monje Tsūshin), activo durante el reinado del rey Shō Kei, fue un monje que fue a la dinastía Qing para estudiar artes marciales chinas y, según se dice, fue uno de los mejores artistas marciales de su tiempo en Ryukyu. [49]

No se sabe cuándo el nombre tōde (唐手, lit. ' mano Tang ' ) comenzó a usarse en el Reino de Ryukyu, pero según Ankō Asato, se popularizó gracias a Kanga Sakugawa (1786-1867), apodado "Tōde Sakugawa". [35] Sakugawa era un samurái de Shuri que viajó a la China Qing para aprender artes marciales chinas. Las artes marciales que dominó eran nuevas y diferentes del te. A medida que Sakugawa difundió el tōde , el te tradicional pasó a llamarse Okinawa-te (沖縄手, lit. ' mano de Okinawa ' ), y gradualmente se desvaneció al fusionarse con el tōde .

En general, se cree que el karate actual es el resultado de la síntesis de te ( Okinawa-te ) y tōde . Funakoshi escribe: "A principios de la era moderna, cuando China era muy venerada, muchos artistas marciales viajaron a China para practicar kenpo chino y lo agregaron al kenpo antiguo, el llamado 'Okinawa-te'. Después de estudiar más a fondo, descartaron las desventajas de ambos, adoptaron sus ventajas y agregaron más sutileza, y así nació el karate". [16]

Los primeros estilos de karate suelen generalizarse como Shuri-te , Naha-te y Tomari-te , llamados así por las tres ciudades de las que surgieron. [50] Cada zona y sus maestros tenían katas, técnicas y principios particulares que distinguían su versión local de te de las demás.

Alrededor de la década de 1820, Matsumura Sōkon (1809-1899) comenzó a enseñar Okinawa-te . [51] Matsumura fue, según una teoría, un estudiante de Sakugawa. El estilo de Matsumura se convirtió más tarde en el origen de muchas escuelas de Shuri-te .

Itosu Ankō (1831-1915) estudió con Matsumura y Bushi Nagahama de Naha-te . [52] Creó las formas Pin'an (" Heian " en japonés) que son katas simplificados para estudiantes principiantes. En 1905, Itosu ayudó a introducir el karate en las escuelas públicas de Okinawa. Estas formas se enseñaban a los niños en el nivel de la escuela primaria. La influencia de Itosu en el karate es amplia. Las formas que creó son comunes en casi todos los estilos de karate. Sus estudiantes se convirtieron en algunos de los maestros de karate más conocidos, incluidos Motobu Chōyū , Motobu Chōki , Yabu Kentsū , Hanashiro Chōmo , Gichin Funakoshi y Kenwa Mabuni . A veces se hace referencia a Itosu como "el abuelo del karate moderno". [53]

En 1881, Higaonna Kanryō regresó de China después de años de instrucción con Ryu Ryu Ko y fundó lo que se convertiría en Naha-te . Uno de sus estudiantes fue el fundador de Gojū-ryū , Chōjun Miyagi . Chōjun Miyagi enseñó a karatekas tan conocidos como Seko Higa (que también entrenó con Higaonna), Meitoku Yagi , Miyazato Ei'ichi y Seikichi Toguchi , y durante un breve tiempo cerca del final de su vida, An'ichi Miyagi (un maestro reivindicado por Morio Higaonna ).

Además de los tres primeros estilos de karate te , una cuarta influencia de Okinawa es la de Uechi Kanbun (1877-1948). A la edad de 20 años fue a Fuzhou en la provincia de Fujian, China, para escapar del reclutamiento militar japonés. Mientras estuvo allí estudió con Shū Shiwa (chino: Zhou Zihe周子和 1874-1926). [54] Fue una figura destacada del estilo chino Nanpa Shorin-ken en ese momento. [55] Más tarde desarrolló su propio estilo de karate Uechi-ryū basado en los katas Sanchin , Seisan y Sanseiryu que había estudiado en China. [56]

Cuando a Shō Tai , el último rey del Reino Ryūkyū, se le ordenó mudarse a Tokio en 1879, lo acompañaron destacados maestros de karate como Ankō Asato y Chōfu Kyan (padre de Chōtoku Kyan ). Se desconoce si enseñaron karate a los japoneses en Tokio, aunque hay registros de que Kyan enseñó karate a su hijo. [57]

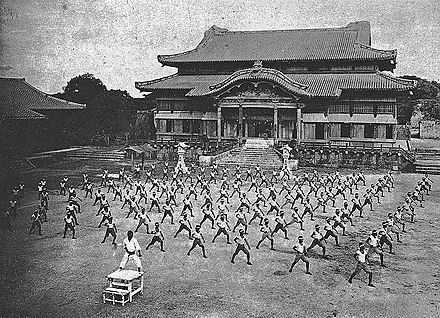

En 1908, los estudiantes de la Escuela Secundaria de la Prefectura de Okinawa dieron una demostración de karate en Butokuden en Kioto, que también fue presenciada por Kanō Jigorō (fundador del judo).

En mayo de 1922, Gichin Funakoshi (fundador del Shotokan ) presentó imágenes de karate en dos pergaminos colgantes en la primera Exposición de Educación Física en Tokio. [58] El siguiente junio, Funakoshi fue invitado al Kodokan para dar una demostración de karate frente a Jigoro Kano y otros expertos en judo. Este fue el comienzo de la introducción a gran escala del karate en Tokio.

En noviembre de 1922, Motobu Chōki (fundador de Motobu-ryū ) participó en un combate de judo contra boxeo en Kioto, donde derrotó a un boxeador extranjero. El combate se publicó en la revista más importante de Japón, "King [ja] ", que tenía una tirada de alrededor de un millón de ejemplares en ese momento, y el karate y el nombre de Motobu se hicieron conocidos instantáneamente en todo Japón. [5]

En 1922, Funakoshi publicó el primer libro sobre karate, [59] y en 1926 Motobu publicó el primer libro técnico sobre kumite. [60] A medida que la popularidad del karate crecía, se establecieron clubes de karate uno tras otro en las universidades japonesas con Funakoshi y Motobu como instructores. [61] [62]

En la era Showa (1926-1989), otros maestros de karate de Okinawa también llegaron al Japón continental para enseñar karate. Entre ellos se encontraban Kenwa Mabuni , Chōjun Miyagi , Kanken Tōyama y Kanbun Uechi .

Con el ascenso del militarismo en Japón, algunos maestros de karate gradualmente comenzaron a considerar el nombre karate (唐手, lit. ' mano Tang ' ) indeseable. El nombre karate (空手, lit. ' mano vacía ' ) ya había sido utilizado por Chōmo Hanashiro en Okinawa en 1905, [63] y Funakoshi decidió utilizar este nombre también. Además, el nombre karatedō (唐手道, lit. ' el camino de la mano Tang ' ), que ya era utilizado por el club de karate de la Universidad Imperial de Tokio (ahora la Universidad de Tokio) en 1929 al agregar el sufijo dō (道, camino) al karate, [64] también fue utilizado por Funakoshi, quien decidió utilizar el nombre karatedō (空手道, lit. ' el camino de la mano vacía ' ) de la misma manera. [16]

El sufijo dō implica que el karatedō es un camino hacia el autoconocimiento, no solo un estudio de los aspectos técnicos de la lucha. Como la mayoría de las artes marciales practicadas en Japón, el karate hizo su transición de -jutsu a -dō a principios del siglo XX. El " dō " en "karate-dō" lo distingue del karate- jutsu , como el aikido se distingue del aikijutsu , el judo del jujutsu , el kendo del kenjutsu y el iaido del iaijutsu .

En 1933, el karate fue reconocido oficialmente como arte marcial japonés por la Dai Nippon Butoku Kai , pero inicialmente pertenecía a la división de jujutsu y los exámenes de título eran realizados por maestros de jujutsu.

En 1935, Funakoshi cambió los nombres de muchos katas y del karate en sí. La motivación de Funakoshi fue que los nombres de muchos de los katas tradicionales eran ininteligibles y que sería inapropiado usar los nombres de los estilos chinos para enseñar karate como un arte marcial japonés. [65] También dijo que los katas tenían que simplificarse para difundir el karate como una forma de educación física, por lo que algunos de los katas fueron modificados. [66] Siempre se refirió a lo que enseñaba simplemente como karate, pero en 1936 construyó un dōjō en Tokio y el estilo que dejó atrás generalmente se llama Shotokan en honor a este dōjō. Shoto , que significa "ola de pino", era el seudónimo de Funakoshi y kan significa "salón".

El 25 de octubre de 1936, se celebró una mesa redonda de maestros de karate en Naha, prefectura de Okinawa, donde se decidió oficialmente cambiar el nombre del karate de karate (mano Tang) a karate (mano vacía). Asistieron Chōmo Hanashiro, Chōki Motobu, Chōtoku Kyan, Jūhatsu Kyoda , Chōjun Miyagi , Shinpan Gusukuma y Chōshin Chibana . En 2005, la Asamblea de la Prefectura de Okinawa aprobó una resolución para conmemorar esta decisión designando el 25 de octubre como el "Día del Karate". [67]

La modernización y sistematización del karate en Japón también incluyó la adopción del uniforme blanco, que consistía en el dogi o keikogi —llamado mayoritariamente simplemente karategi— y los cinturones de colores. Ambas innovaciones fueron originadas y popularizadas por Jigoro Kano , el fundador del judo y uno de los hombres a los que Funakoshi consultó en sus esfuerzos por modernizar el karate.

En esa época, casi no había entrenamiento de kumite en karate, y el entrenamiento de kata era el foco principal. [68] Tampoco había combates. Sin embargo, en ese momento, ya se celebraban combates de judo y kendo en Japón continental, y también se practicaba activamente la práctica de randori (乱取り, lit. ' práctica de estilo libre ' ) y los jóvenes en Japón continental gradualmente se sintieron insatisfechos con la práctica exclusiva de kata. [68]

En Okinawa antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los karatekas practicaban iri kumi ( kumite en okinawense ), lo que permitía todo tipo de técnicas (golpes, estrangulamientos, luxaciones, etc.) pero de forma controlada para no lesionar al oponente cuando se apuntaba a zonas vitales. [69] A pesar de que el sparring era originalmente una forma de práctica inadvertida para estudiantes mayores, no hubo "competiciones" hasta que se introdujeron las competiciones de estilo occidental en Japón. [70]

Gichin Funakoshi afirmó: "En el karate no hay competiciones". [71] Shigeru Egami relata que, durante su visita a Okinawa en 1940, escuchó que algunos karatekas fueron expulsados de sus dōjō porque adoptaron el combate después de haberlo aprendido en Tokio. A principios de los años 30, se introdujo y desarrolló el combate preestablecido y, finalmente, unos años más tarde, se permitió el combate libre para los estudiantes de Shotokan. [72]

Según Yasuhiro Konishi , el entrenamiento basado únicamente en kata fue criticado a menudo por los principales practicantes de judo de la época, como Shuichi Nagaoka y Hajime Isogai , quienes dijeron: "El karate que haces no se puede entender solo con kata, así que ¿por qué no intentas un poco más para que el público en general pueda entenderlo?" [68] En el contexto de estas quejas y críticas, jóvenes como Hironori Ōtsuka y Konishi idearon su propio kumite y combates de kumite, que son los prototipos del kumite actual. [68] [73] El énfasis de Motobu en el kumite atrajo a Ōtsuka y Konishi, quienes más tarde estudiaron kumite de Okinawa con él. [68]

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, las actividades de karate se paralizaron temporalmente debido al "Aviso de prohibición del judo, el kendo y otras artes marciales" emitido por el Ministerio de Educación según la directiva del Comandante Supremo de las Potencias Aliadas . Sin embargo, debido a que este aviso no incluía la palabra "karate", el Ministerio de Educación interpretó que el karate no estaba prohibido y que el karate pudo reanudar sus actividades antes que otras artes marciales.

En 1957 Masutatsu Oyama (que nació en Corea, Choi Yeong-Eui 최영의) fundó formalmente una nueva forma de karate llamada Kyokushin . El Kyokushin es en gran medida una síntesis de Shotokan y Gōjū-ryū. Enseña un plan de estudios que enfatiza la vitalidad , la dureza física y el combate de contacto total . Debido a su énfasis en el combate físico de fuerza total , el Kyokushin ahora se denomina a menudo " karate de contacto total " o " karate de derribo " (por el nombre de sus reglas de competencia). Muchas otras organizaciones y estilos de karate descienden del plan de estudios de Kyokushin.

El karate puede practicarse como arte ( budō ), defensa personal o como deporte de combate . El karate tradicional pone énfasis en el autodesarrollo (budō). [74] El entrenamiento de estilo japonés moderno enfatiza los elementos psicológicos incorporados en un kokoro (actitud) adecuado, como la perseverancia, la intrepidez, la virtud y las habilidades de liderazgo. El karate deportivo pone énfasis en el ejercicio y la competencia. Las armas son una actividad de entrenamiento importante en algunos estilos de karate.

El entrenamiento de karate se divide comúnmente en kihon (conceptos básicos o fundamentos), kata (formas) y kumite (combate).

Kihon significa fundamentos y estos forman la base para todo lo demás en el estilo, incluyendo posturas, golpes, puñetazos, patadas y bloqueos. Los estilos de karate le dan distinta importancia al kihon. Por lo general, se trata de un entrenamiento al unísono de una técnica o una combinación de técnicas por parte de un grupo de karatekas. El kihon también puede ser ejercicios preestablecidos en grupos más pequeños o en parejas.

Kata (型:かた) significa literalmente "forma" o "modelo". Kata es una secuencia formalizada de movimientos que representan varias posturas ofensivas y defensivas. Estas posturas se basan en aplicaciones de combate idealizadas. Las aplicaciones cuando se aplican en una demostración con oponentes reales se denominan Bunkai . El Bunkai muestra cómo se utiliza cada postura y movimiento. Bunkai es una herramienta útil para comprender un kata.

Para alcanzar un rango formal, el karateka debe demostrar un desempeño competente de los katas específicos requeridos para ese nivel. Se utiliza comúnmente la terminología japonesa para grados o rangos. Los requisitos para los exámenes varían entre las escuelas.

El combate en Karate se llama kumite (組手:くみて). Literalmente significa "encuentro de manos". El kumite se practica tanto como deporte como entrenamiento de autodefensa. Los niveles de contacto físico durante el combate varían considerablemente. El karate de contacto total tiene varias variantes. El karate de derribo (como Kyokushin ) utiliza técnicas de máxima potencia para derribar a un oponente al suelo. El combate con armadura, bogu kumite , permite técnicas de máxima potencia con cierta seguridad. El kumite deportivo en muchas competiciones internacionales de la Federación Mundial de Karate es libre o estructurado con contacto ligero o semicontacto y los puntos son otorgados por un árbitro.

En el kumite estructurado ( yakusoku , preestablecido), dos participantes realizan una serie de técnicas coreografiadas, en las que uno golpea mientras el otro bloquea. La forma finaliza con una técnica devastadora ( hito tsuki ).

En el combate libre (Jiyu Kumite), los dos participantes pueden elegir libremente la técnica que puntúe. Las técnicas permitidas y el nivel de contacto están determinados principalmente por la política de la organización del deporte o estilo, pero pueden modificarse según la edad, el rango y el sexo de los participantes. Según el estilo, también se permiten derribos , barridos y, en algunos casos excepcionales, incluso agarres en el suelo por tiempo limitado .

El combate libre se realiza en un área marcada o cerrada. El combate dura un tiempo fijo (2 a 3 minutos). El tiempo puede transcurrir de forma continua ( iri kume ) o detenerse para que lo decida el árbitro. En el kumite de contacto ligero o semicontacto , los puntos se otorgan en función de los siguientes criterios: buena forma, actitud deportiva, aplicación vigorosa, conciencia/ zanshin , buen ritmo y distancia correcta. En el kumite de karate de contacto completo, los puntos se basan en los resultados del impacto, en lugar de en la apariencia formal de la técnica de puntuación.

En la tradición bushidō , el dōjō kun es un conjunto de pautas que deben seguir los karatekas. Estas pautas se aplican tanto en el dōjō (sala de entrenamiento) como en la vida cotidiana.

El karate de Okinawa utiliza un entrenamiento complementario conocido como hojo undo . Este utiliza un equipo simple hecho de madera y piedra. El makiwara es un poste de golpeo. El juego nigiri es un recipiente grande utilizado para desarrollar la fuerza de agarre. Estos ejercicios complementarios están diseñados para aumentar la fuerza , la resistencia , la velocidad y la coordinación muscular . [75] El karate deportivo enfatiza el ejercicio aeróbico , el ejercicio anaeróbico , la potencia , la agilidad , la flexibilidad y el manejo del estrés . [76] Todas las prácticas varían según la escuela y el maestro.

El karate se divide en organizaciones de estilos. [77] Estas organizaciones a veces cooperan en organizaciones o federaciones de karate deportivo no específicas de un estilo. Ejemplos de organizaciones deportivas incluyen AAKF/ITKF, AOK, TKL, AKA, WKF, NWUKO, WUKF y WKC. [78] Las organizaciones realizan competiciones (torneos) desde el nivel local hasta el internacional. Los torneos están diseñados para enfrentar a miembros de escuelas o estilos opuestos entre sí en kata, combate y demostración de armas. A menudo están separados por edad, rango y sexo con reglas o estándares potencialmente diferentes basados en estos factores. El torneo puede ser exclusivamente para miembros de un estilo en particular (cerrado) o uno en el que cualquier artista marcial de cualquier estilo puede participar dentro de las reglas del torneo (abierto).

La Federación Mundial de Karate (WKF) es la organización deportiva de karate más grande y está reconocida por el Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI) como responsable de la competencia de karate en los Juegos Olímpicos. [79] La WKF ha desarrollado reglas comunes que rigen todos los estilos. Las organizaciones nacionales de la WKF se coordinan con sus respectivos Comités Olímpicos Nacionales .

La competición de karate de la WKF tiene dos disciplinas: combate ( kumite ) y formas ( kata ). [80] Los competidores pueden participar como individuos o como parte de un equipo. La evaluación para kata y kobudō la realiza un panel de jueces, mientras que el combate lo juzga un árbitro principal, generalmente con árbitros asistentes al costado del área de combate. Los combates de combate generalmente se dividen por peso, edad, género y experiencia. [81]

WKF only allows membership through one national organization/federation per country to which clubs may join. The World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF)[82] offers different styles and federations a world body they may join, without having to compromise their style or size. The WUKF accepts more than one federation or association per country.

Sport organizations use different competition rule systems.[77][81][83][84][85] Light contact rules are used by the WKF, WUKO, IASK and WKC. Full contact karate rules used by Kyokushinkai, Seidokaikan and other organizations. Bogu kumite (full contact with protective shielding of targets) rules are used in the World Koshiki Karate-Do Federation organization.[86] Shinkaratedo Federation use boxing gloves.[87] Within the United States, rules may be under the jurisdiction of state sports authorities, such as the boxing commission.

Karate, although not widely used in mixed martial arts, has been effective for some MMA practitioners.[88][89] Various styles of karate are practiced in MMA: Lyoto Machida and John Makdessi practice Shotokan;[90] Bas Rutten and Georges St-Pierre train in Kyokushin;[91] Michelle Waterson holds a black belt in American Free Style Karate;[92] Stephen Thompson practices American Kenpo Karate;[93] and both Gunnar Nelson[94] and Robert Whittaker practiced Gōjū-ryū.[95] Additionally, John Kavanagh has been successful as coach with a Kenpo Karate pedigree.[96]

_18.jpg/440px-2018-10-18_Karate_Boys'_+68_kg_at_2018_Summer_Youth_Olympics_–_Bronze_IRL–MAR_(Martin_Rulsch)_18.jpg)

In August 2016, the International Olympic Committee approved karate as an Olympic sport beginning at the 2020 Summer Olympics.[97][98] Karate also debuted at the 2018 Summer Youth Olympics. During this debut of Karate in the Summer Olympics, sixty competitors from around the world competed in the Kumite competition, and twenty competed in the Kata competition. In September 2015, karate was included in a shortlist along with baseball, softball, skateboarding, surfing, and sport climbing to be considered for inclusion in the 2020 Summer Olympics;[99] and in June 2016, the executive board of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced that they would support the proposal to include all of the shortlisted sports in the 2020 Games.[100] Finally, on 3 August 2016, all five sports (counting baseball and softball together as one sport) were approved for inclusion in the 2020 Olympic program.[101]

Karate was not included in the 2024 Olympic Games, although it has made the shortlist for inclusion, alongside nine others, in the 2028 Summer Olympics.[102]

In 1924, Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, adopted the Dan system from the judo founder Jigoro Kano[103] using a rank scheme with a limited set of belt colors. Other Okinawan teachers also adopted this practice. In the Kyū/Dan system the beginner grades start with a higher numbered kyū (e.g., 10th Kyū or Jukyū) and progress toward a lower numbered kyū. The Dan progression continues from 1st Dan (Shodan, or 'beginning dan') to the higher dan grades. Kyū-grade karateka are referred to as "color belt" or mudansha ("ones without dan/rank"). Dan-grade karateka are referred to as yudansha (holders of dan/rank). Yudansha typically wear a black belt. Normally, the first five to six dans are given by examination by superior dan holders, while the subsequent (7 and up) are honorary, given for special merits and/or age reached. Requirements of rank differ among styles, organizations, and schools. Kyū ranks stress Karate stances, Equilibrioception, and motor coordination. Speed and power are added at higher grades.

Minimum age and time in rank are factors affecting promotion. Testing consists of demonstration of techniques before a panel of examiners or senseis. This will vary by school, but testing may include everything learned at that point, or just new information. The demonstration is an application for new rank (shinsa) and may include basics, kata, bunkai, self-defense, routines, tameshiwari (breaking), and kumite (sparring).

In Karate-Do Kyohan, Funakoshi quoted from the Heart Sutra, which is prominent in Shingon Buddhism: "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form itself" (shiki zokuze kū kū zokuze shiki).[104]He interpreted the "kara" of Karate-dō to mean "to purge oneself of selfish and evil thoughts ... for only with a clear mind and conscience can the practitioner understand the knowledge which he receives." Funakoshi believed that one should be "inwardly humble and outwardly gentle." Only by behaving humbly can one be open to Karate's many lessons. This is done by listening and being receptive to criticism. He considered courtesy of prime importance. He said that "Karate is properly applied only in those rare situations in which one really must either down another or be downed by him." Funakoshi did not consider it unusual for a devotee to use Karate in a real physical confrontation no more than perhaps once in a lifetime. He stated that Karate practitioners must "never be easily drawn into a fight." It is understood that one blow from a real expert could mean death. It is clear that those who misuse what they have learned bring dishonor upon themselves. He promoted the character trait of personal conviction. In "time of grave public crisis, one must have the courage ... to face a million and one opponents." He taught that indecisiveness is a weakness.[105]

Karate is divided into many styles, each with their different training methods, focuses, and cultures; though they mainly originate from the historical Okinawan parent styles of Naha-te, Tomari-te and Shuri-te.

However some of the schools' founders have been sceptical with the separation of karate into many styles. Gichin Funakoshi simply stated that there are as many styles as instructors in the world while Kenwa Mabuni explained that the notion of different variations of karate came from outsiders.[106] During karate popularization in mainland Japan, it was spread the idea that karate was divided into two branches: Shōrin-ryū (derived from Itosu's teachings) and Shōrei-ryū (derived from Higaonna's teachings);[107] but Chōjun Miyagi believed that was just a wrong perception.[108] Mas Oyama was actively opposed to the idea of the break-down into several karate schools.[109] He believed that making karate a combat sport, as well keeping it as a martial art, could be a possible approach to unify all schools.[110]

In the modern era the major four styles of karate are considered to be Gōjū-ryū, Shotokan, Shitō-ryū, and Wadō-ryū.[111] These four styles are those recognised by the World Karate Federation for international kata competition.[112] Some widespread styles[113][107] oftenly accepted for kata competition include Kyokushin, Shōrin-ryū or Uechi-Ryū among others.[114][115][112]

Karate has grown in popularity in Africa, particularly in South Africa and Ghana.[116][117][118]

Karate began in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s as Japanese people immigrated to the country. Karate was practised quietly without a large amount of organization. During the Second World War, many Japanese-Canadian families were moved to the interior of British Columbia. Masaru Shintani, at the age of 13, began to study Shorin-Ryu karate in the Japanese camp under Kitigawa. In 1956, after 9 years of training with Kitigawa, Shintani travelled to Japan and met Hironori Otsuka (Wado Ryu). In 1958, Otsuka invited Shintani to join his organization Wado Kai, and in 1969 he asked Shintani to officially call his style Wado.[119]

In Canada during this same time, karate was also introduced by Masami Tsuruoka who had studied in Japan in the 1940s under Tsuyoshi Chitose.[120] In 1954, Tsuruoka initiated the first karate competition in Canada and laid the foundation for the National Karate Association.[120]

In the late 1950s Shintani moved to Ontario and began teaching karate and judo at the Japanese Cultural Centre in Hamilton. In 1966, he began (with Otsuka's endorsement) the Shintani Wado Kai Karate Federation. During the 1970s Otsuka appointed Shintani the Supreme Instructor of Wado Kai in North America. In 1979, Otsuka publicly promoted Shintani to hachidan (8th dan) and privately gave him a kudan certificate (9th dan), which was revealed by Shintani in 1995. Shintani and Otsuka visited each other in Japan and Canada several times, the last time in 1980 two years prior to Otsuka's death. Shintani died 7 May 2000.[119]

After World War II, members of the United States military learned karate in Okinawa or Japan and then opened schools in the US. In 1945, Robert Trias opened the first dōjō in the United States in Phoenix, Arizona, a Shuri-ryū karate dōjō.[121] In the 1950s, William J. Dometrich, Ed Parker, Cecil T. Patterson, Gordon Doversola, Harold G. Long, Donald Hugh Nagle, George Mattson and Peter Urban all began instructing in the US.

Tsutomu Ohshima began studying karate under Shotokan's founder, Gichin Funakoshi, while a student at Waseda University, beginning in 1948. In 1957, Ohshima received his godan (fifth-degree black belt), the highest rank awarded by Funakoshi. He founded the first university karate club in the United States at California Institute of Technology in 1957. In 1959, he founded the Southern California Karate Association (SCKA) which was renamed Shotokan Karate of America (SKA) in 1969.

In the 1960s, Anthony Mirakian, Richard Kim, Teruyuki Okazaki, John Pachivas, Allen Steen, Gosei Yamaguchi (son of Gōgen Yamaguchi), Michael G. Foster and Pat Burleson began teaching martial arts around the country.[122]

In 1961, Hidetaka Nishiyama, a co-founder of the Japan Karate Association (JKA) and student of Gichin Funakoshi, began teaching in the United States. He founded the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF). Takayuki Mikami was sent to New Orleans by the JKA in 1963.

In 1964, Takayuki Kubota relocated the International Karate Association from Tokyo to California.

Due to past conflict between Korea and Japan, most notably during the Japanese occupation of Korea in the early 20th century, the influence of karate in Korea is a contentious issue.[123] From 1910 until 1945, Korea was annexed by the Japanese Empire. It was during this time that many of the Korean martial arts masters of the 20th century were exposed to Japanese karate. After regaining independence from Japan, many Korean martial arts schools that opened up in the 1940s and 1950s were founded by masters who had trained in karate in Japan as part of their martial arts training.

Won Kuk Lee, a Korean student of Funakoshi, founded the first martial arts school after the Japanese occupation of Korea ended in 1945, called the Chung Do Kwan. Having studied under Gichin Funakoshi at Chuo University, Lee had incorporated taekkyon, kung fu, and karate in the martial art that he taught which he called "Tang Soo Do", the Korean transliteration of the Chinese characters for "Way of Chinese Hand" (唐手道).[124] In the mid-1950s, the martial arts schools were unified under President Rhee Syngman's order, and became taekwondo under the leadership of Choi Hong Hi and a committee of Korean masters. Choi, a significant figure in taekwondo history, had also studied karate under Funakoshi. Karate also provided an important comparative model for the early founders of taekwondo in the formalization of their art including hyung and the belt ranking system. The original taekwondo hyung were identical to karate kata. Eventually, original Korean forms were developed by individual schools and associations. Although the World Taekwondo Federation and International Taekwon-Do Federation are the most prominent among Korean martial arts organizations, tang soo do schools that teach Japanese karate still exist as they were originally conveyed to Won Kuk Lee and his contemporaries from Funakoshi.

Karate appeared in the Soviet Union in the mid-1960s, during Nikita Khrushchev's policy of improved international relations. The first Shotokan clubs were opened in Moscow's universities.[125] In 1973, however, the government banned karate—together with all other foreign martial arts—endorsing only the Soviet martial art of sambo.[126][127] Failing to suppress these uncontrolled groups, the USSR's Sport Committee formed the Karate Federation of USSR in December 1978.[128] On 17 May 1984, the Soviet Karate Federation was disbanded and all karate became illegal again. In 1989, karate practice became legal again, but under strict government regulations, only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 did independent karate schools resume functioning, and so federations were formed and national tournaments in authentic styles began.[129][130]

In the 1950s and 1960s, several Japanese karate masters began to teach the art in Europe, but it was not until 1965 that the Japan Karate Association (JKA) sent to Europe four well-trained young Karate instructors Taiji Kase, Keinosuke Enoeda, Hirokazu Kanazawa and Hiroshi Shirai.[citation needed] Kase went to France, Enoeada to England and Shirai in Italy. These Masters maintained always a strong link between them, the JKA and the others JKA masters in the world, especially Hidetaka Nishiyama in the US

France Shotokan Karate was created in 1964 by Tsutomu Ohshima. It is affiliated with another of his organizations, Shotokan Karate of America (SKA). However, in 1965 Taiji Kase came from Japan along with Enoeda and Shirai, who went to England and Italy respectively, and karate came under the influence of the JKA.

Hiroshi Shirai, one of the original instructors sent by the JKA to Europe along with Kase, Enoeda and Kanazawa, moved to Italy in 1965 and quickly established a Shotokan enclave that spawned several instructors who in their turn soon spread the style all over the country. By 1970 Shotokan karate was the most spread martial art in Italy apart from Judo. Other styles such as Wado Ryu, Goju Ryu and Shito Ryu, are present and well established in Italy, while Shotokan remains the most popular.

Vernon Bell, a 3rd Dan Judo instructor who had been instructed by Kenshiro Abbe introduced Karate to England in 1956, having attended classes in Henry Plée's Yoseikan dōjō in Paris. Yoseikan had been founded by Minoru Mochizuki, a master of multiple Japanese martial arts, who had studied Karate with Gichin Funakoshi, thus the Yoseikan style was heavily influenced by Shotokan.[131] Bell began teaching in the tennis courts of his parents' back garden in Ilford, Essex and his group was to become the British Karate Federation. On 19 July 1957, Vietnamese Hoang Nam 3rd Dan, billed as "Karate champion of Indo China", was invited to teach by Bell at Maybush Road, but the first instructor from Japan was Tetsuji Murakami (1927–1987) a 3rd Dan Yoseikan under Minoru Mochizuki and 1st Dan of the JKA, who arrived in England in July 1959.[131] In 1959, Frederick Gille set up the Liverpool branch of the British Karate Federation, which was officially recognised in 1961. The Liverpool branch was based at Harold House Jewish Boys Club in Chatham Street before relocating to the YMCA in Everton where it became known as the Red Triangle. One of the early members of this branch was Andy Sherry who had previously studied Jujutsu with Jack Britten. In 1961, Edward Ainsworth, another blackbelt Judoka, set up the first Karate study group in Ayrshire, Scotland having attended Bell's third 'Karate Summer School' in 1961.[131]

Outside of Bell's organisation, Charles Mack traveled to Japan and studied under Masatoshi Nakayama of the Japan Karate Association who graded Mack to 1st Dan Shotokan on 4 March 1962 in Japan.[131] Shotokai Karate was introduced to England in 1963 by another of Gichin Funakoshi's students, Mitsusuke Harada.[131] Outside of the Shotokan stable of karate styles, Wado Ryu Karate was also an early adopted style in the UK, introduced by Tatsuo Suzuki, a 6th Dan at the time in 1964.

Despite the early adoption of Shotokan in the UK, it was not until 1964 that JKA Shotokan officially came to the UK. Bell had been corresponding with the JKA in Tokyo asking for his grades to be ratified in Shotokan having apparently learnt that Murakami was not a designated representative of the JKA. The JKA obliged, and without enforcing a grading on Bell, ratified his black belt on 5 February 1964, though he had to relinquish his Yoseikan grade. Bell requested a visitation from JKA instructors and the next year Taiji Kase, Hirokazu Kanazawa, Keinosuke Enoeda and Hiroshi Shirai gave the first JKA demo at the old Kensington Town Hall on 21 April 1965. Hirokazu Kanazawa and Keinosuke Enoeda stayed and Murakami left (later re-emerging as a 5th Dan Shotokai under Harada).[131]

In 1966, members of the former British Karate Federation established the Karate Union of Great Britain (KUGB) under Hirokazu Kanazawa as chief instructor[132] and affiliated to JKA. Keinosuke Enoeda came to England at the same time as Kanazawa, teaching at a dōjō in Liverpool. Kanazawa left the UK after 3 years and Enoeda took over. After Enoeda's death in 2003, the KUGB elected Andy Sherry as Chief Instructor. Shortly after this, a new association split off from KUGB, JKA England. An earlier significant split from the KUGB took place in 1991 when a group led by KUGB senior instructor Steve Cattle formed the English Shotokan Academy (ESA). The aim of this group was to follow the teachings of Taiji Kase, formerly the JKA chief instructor in Europe, who along with Hiroshi Shirai created the World Shotokan Karate-do Academy (WKSA), in 1989 to pursue the teaching of "Budo" karate as opposed to what he viewed as "sport karate". Kase sought to return the practice of Shotokan Karate to its martial roots, reintroducing among other things open hand and throwing techniques that had been side lined as the result of competition rules introduced by the JKA. Both the ESA and the WKSA (renamed the Kase-Ha Shotokan-Ryu Karate-do Academy (KSKA) after Kase's death in 2004) continue following this path today. In 1975, Great Britain became the first team ever to take the World male team title from Japan after being defeated the previous year in the final.

The World Karate Federation was first introduced to Oceania as the Oceania Karate Federation 1973.[133]

The Australian Karate Federation, under the World Karate Federation, was first introduced in 1970. In 1972 Frank Novak became the first fully qualified Shotokan instructor to arrive in Australia and teach in the country,[134] establishing the first Shotokan Karate dojo in Australia.[135] At karate's debut in the Olympics at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Tsuneari Yahiro became Australia's first Karate Olympian.[136]

Karate spread rapidly in the West through popular culture. In 1950s popular fiction, karate was at times described to readers in near-mythical terms, and it was credible to show Western experts of unarmed combat as unaware of Eastern martial arts of this kind.[137][better source needed] Following the inclusion of judo at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, there was growing mainstream Western interest in Japanese martial arts, particularly karate, during the 1960s.[138] By the 1970s, martial arts films (especially kung fu films and Bruce Lee flicks from Hong Kong) had formed a mainstream genre and launched the "kung fu craze" which propelled karate and other Asian martial arts into mass popularity. However, mainstream Western audiences at the time generally did not distinguish between different Asian martial arts such as karate, kung fu and tae kwon do.[93]

In the film series 007 (1953–present), the main protagonist James Bond is exceptionally skillful in martial arts. He is an expert in various types of martial arts including Karate, as well as Judo, Aikido, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Filipino Eskrima and Krav Maga.[citation needed]

During the late 20th century, specifically during the 80s and 90s, karate saw a rise in mainstream popularity. America in the 80s took hold of the martial arts craze and began to produce more homegrown films in the martial arts genre.[139] Films weren't the only popular visual representation of Karate in the 80s, just as arcades grew in popularity, so did Karate in arcade fighting games. The first video game to feature fist fighting was Heavyweight Champ in 1976,[140] but it was Karate Champ that popularized the one-on-one fighting game genre in arcades in 1984. In 1987, Capcom released Street Fighter, featuring multiple Karateka characters.[141][142]

The Karate Kid (1984) and its sequels The Karate Kid, Part II (1986), The Karate Kid, Part III (1989) and The Next Karate Kid (1994) are films relating the fictional story of an American adolescent's introduction into karate.[143][144] Its television sequel, Cobra Kai (2018), has led to similar growing interest in karate.[145] The success of The Karate Kid further popularized karate (as opposed to Asian martial arts more generally) in mainstream American popular culture.[93] Karate Kommandos is an animated children's show, with Chuck Norris appearing to reveal the moral lessons contained in every episode.Dragon Ball (1984–present) is a Japanese media franchise (Anime) whose characters use a variety and hybrid of east Asian martial arts styles, including Karate[146][147][148] and Wing Chun (Kung fu).[147][148][149] Dragon Ball was originally inspired by the classical 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West, combined with elements of Hong Kong martial arts films, with influences of Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee.

In the film series The Matrix, Neo uses a variety of martial arts styles.[150] Neo's skill in martial arts was shown having downloaded into his brain, which granted combat abilities equivalent to a martial artist with decades of experience. Kenpo Karate is one of the many styles Neo learns as part of his computerised combat training.[151] As part of the preparation for the movie, Yuen Woo-ping had Keanu Reeves undertake four months of martial arts training in a variety of different styles.[150]

Many other film stars such as Bruce Lee, Chuck Norris, Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and Jet Li come from a range of other martial arts.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)