El zorro rojo ( Vulpes vulpes ) es el más grande de los zorros verdaderos y uno de los miembros más ampliamente distribuidos del orden Carnivora , estando presente en todo el hemisferio norte , incluida la mayor parte de América del Norte , Europa y Asia , además de partes del norte de África . Está catalogado como de menor preocupación en la Lista Roja de la UICN . [1] Su área de distribución ha aumentado junto con la expansión humana, habiéndose introducido en Australia , donde se considera dañino para los roedores y marsupiales nativos de tamaño pequeño y mediano . Debido a su impacto en las especies nativas, está incluido en la lista de las " 100 peores especies invasoras del mundo ". [4]

El zorro rojo se originó en Eurasia durante el Pleistoceno medio hace al menos 400.000 años [5] y luego colonizó América del Norte en algún momento antes de hace 130.000 años. [6] Entre los zorros verdaderos, el zorro rojo representa una forma más progresiva en la dirección de la carnivoría . [7] Aparte de su gran tamaño, el zorro rojo se distingue de otras especies de zorros por su capacidad de adaptarse rápidamente a nuevos entornos. A pesar de su nombre, la especie a menudo produce individuos con otras coloraciones, incluidos individuos leucísticos y melánicos . [7] Actualmente se reconocen cuarenta y cinco subespecies , [8] que se dividen en dos categorías: los grandes zorros del norte y los pequeños zorros grises del desierto del sur basales de Asia y el norte de África. [7]

Los zorros rojos se encuentran generalmente en parejas o grupos pequeños que consisten en familias, como una pareja apareada y sus crías, o un macho con varias hembras que tienen lazos de parentesco. Las crías de la pareja apareada permanecen con sus padres para ayudar en el cuidado de los nuevos cachorros. [9] La especie se alimenta principalmente de pequeños roedores, aunque también puede apuntar a conejos , ardillas , aves de caza , reptiles , invertebrados [7] y ungulados jóvenes . [7] A veces también comen frutas y verduras. [10] Aunque el zorro rojo tiende a matar a depredadores más pequeños, incluidas otras especies de zorros, es vulnerable al ataque de depredadores más grandes, como lobos , coyotes , chacales dorados , grandes aves depredadoras como águilas reales y búhos reales , [11] y felinos de tamaño mediano y grande . [12]

La especie tiene una larga historia de asociación con los humanos, habiendo sido ampliamente cazada como plaga y animal de piel durante muchos siglos, además de estar representada en el folclore y la mitología humana. Debido a su amplia distribución y gran población, el zorro rojo es uno de los animales de piel más importantes capturados para el comercio de pieles . [13] : 229–230 Demasiado pequeño para representar una amenaza para los humanos, se ha beneficiado ampliamente de la presencia de la habitación humana y ha colonizado con éxito muchas áreas suburbanas y urbanas . La domesticación del zorro rojo también está en marcha en Rusia , y ha dado como resultado el zorro plateado domesticado .

.jpg/440px-Red_fox_kits_(40215161564).jpg)

Los machos se llaman tods o perros, las hembras se llaman zorras y las crías se conocen como cachorros o kits. [14] Aunque el zorro ártico tiene una pequeña población nativa en el norte de Escandinavia, y mientras que el área de distribución del zorro corsaco se extiende hasta la Rusia europea , el zorro rojo es el único zorro nativo de Europa occidental, por lo que simplemente se le llama "el zorro" en inglés británico coloquial.

La palabra "zorro" proviene del inglés antiguo , que deriva del protogermánico * fuhsaz . Compárese con el frisón occidental foks , el holandés vos y el alemán Fuchs . Este, a su vez, deriva del protoindoeuropeo * puḱ- 'de pelo grueso; cola'. Compárese con el hindi pū̃ch 'cola', el tocario B päkā 'cola; chowrie' y el lituano pūkas 'piel / pelusa'. La cola peluda también forma la base del nombre galés del zorro, llwynog , literalmente 'peludo', de llwyn 'arbusto'. Del mismo modo, el portugués : raposa de rabo 'cola', el lituano uodẽgis de uodegà 'cola' y el ojibwa waagosh de waa , que se refiere al "rebote" o parpadeo hacia arriba y hacia abajo de un animal o su cola. [ cita requerida ]

El término científico vulpes deriva de la palabra latina para zorro, y da los adjetivos vulpino y vulpecular . [15]

Se considera que el zorro rojo es una forma más especializada de Vulpes que las especies de zorro afgano , corsac y de Bengala , en lo que respecta a su tamaño general y adaptación a la carnivoría ; el cráneo muestra muchos menos rasgos neoténicos que en otros zorros, y su área facial está más desarrollada. [7] Sin embargo, no está tan adaptado a una dieta puramente carnívora como el zorro tibetano . [7]

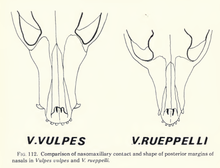

El linaje hermano del zorro rojo es el zorro de Rüppell , pero las dos especies están sorprendentemente estrechamente relacionadas a través de marcadores de ADN mitocondrial , con el zorro de Rüppell anidado dentro de los linajes de zorros rojos. [16] [17] Tal anidación de una especie dentro de otra se llama parafilia . Se han sugerido varias hipótesis para explicar esto, [16] incluyendo (1) divergencia reciente del zorro de Rüppell de un linaje de zorros rojos, (2) clasificación de linaje incompleta o introgresión de ADNmt entre las dos especies. Con base en la evidencia del registro fósil, el último escenario parece más probable, que está respaldado además por las claras diferencias ecológicas y morfológicas entre las dos especies. [ cita requerida ]

La especie es de origen euroasiático y puede haber evolucionado a partir de Vulpes alopecoides o del relacionado chino V. chikushanensis , ambos vivieron durante el Villafranquiano medio del Pleistoceno . [19] Los primeros especímenes fósiles de V. vulpes fueron descubiertos en el condado de Baranya , Hungría , y datan de hace 3,4 a 1,8 millones de años. [20] El zorro rojo ancestral probablemente era más diminuto en comparación con los zorros actuales, ya que los primeros fósiles de zorro rojo han mostrado una constitución más pequeña que los especímenes vivos. [19] : 115–116 Los primeros restos fósiles de la especie moderna datan de mediados del Pleistoceno, [21] encontrados en asociación con basureros y desechos dejados por los primeros asentamientos humanos. Esto ha llevado a la teoría de que el zorro rojo fue cazado por humanos primitivos (como fuente de alimento y pieles); También existe la posibilidad de que los zorros rojos se alimenten de basurales o de cadáveres de animales sacrificados. [22]

Los zorros rojos colonizaron el continente norteamericano en dos oleadas: antes y durante la glaciación de Illinois y durante la glaciación de Wisconsin . [23] El mapeo genético demuestra que los zorros rojos en América del Norte han estado aislados de sus contrapartes del Viejo Mundo durante más de 400.000 años, lo que plantea la posibilidad de que se haya producido especiación y que el nombre binomial anterior de Vulpes fulva pueda ser válido. [24] En el extremo norte, se han encontrado fósiles de zorros rojos en depósitos de la etapa Sangamoniana cerca del distrito Fairbanks , Alaska , y Medicine Hat , Alberta . Los fósiles que datan del Wisconsiniano están presentes en 25 sitios en Arkansas , California , Colorado , Idaho , Misuri , Nuevo México , Ohio , [25] Tennessee , Texas , Virginia y Wyoming . Aunque se extendieron muy al sur durante el Wisconsinan, la aparición de condiciones cálidas redujo su área de distribución hacia el norte, y solo recientemente recuperaron sus antiguas áreas de distribución en América del Norte debido a los cambios ambientales inducidos por el hombre. [26] Las pruebas genéticas indican que existen dos refugios distintos para el zorro rojo en América del Norte, que han estado separados desde el Wisconsinan. El refugio del norte (o boreal) se encuentra en Alaska y el oeste de Canadá, y consta de las subespecies más grandes V. v. alascensis , V. v. abietorum , V. v. regalis y V. v. rubricosa . El refugio del sur (o montañoso) se encuentra en los parques subalpinos y las praderas alpinas del oeste, desde las Montañas Rocosas hasta las cascadas y las cordilleras de Sierra Nevada , y consta de las subespecies más pequeñas V. v. cascadensis , V. v. macroura , V. v. necator y V. v. patwin . Este último clado ha estado separado de todas las demás poblaciones de zorros rojos desde al menos el último máximo glacial, y puede poseer adaptaciones ecológicas o fisiológicas únicas. [23]

Aunque los zorros europeos ( V. v. crucigera ) fueron introducidos en partes de los Estados Unidos en la década de 1900, la investigación genética reciente indica una ausencia de haplotipos mitocondriales del zorro europeo en cualquier población norteamericana. [27] Además, los zorros rojos del este de América del Norte introducidos han colonizado la mayor parte del interior de California, desde el sur de California hasta el valle de San Joaquín , Monterey y el área de la bahía de San Francisco de la costa norte (incluyendo San Francisco urbano y ciudades adyacentes). A pesar de la adaptabilidad del zorro rojo a la vida urbana, todavía se encuentran en cantidades algo mayores en las partes del norte de California (al norte del área de la bahía) que en el sur, ya que el desierto es más alpino y aislado. Los zorros rojos del este parecen haberse mezclado con el zorro rojo del valle de Sacramento ( V. v. patwin ) solo en una estrecha zona híbrida. [28] Además, no se observa evidencia de cruzamiento de zorros rojos del este de Estados Unidos en California con el zorro rojo montañoso de Sierra Nevada ( V. v. necator ) u otras poblaciones en el Oeste Intermontano (entre las Montañas Rocosas al este y las Montañas Cascade y Sierra Nevada al oeste). [29]

La tercera edición de Mammal Species of the World [8] enumera 45 subespecies como válidas. En 2010, se identificó una 46.ª subespecie distinta, el zorro rojo del Valle de Sacramento ( V. v. patwin ), que habita las praderas del Valle de Sacramento, a través de estudios de haplotipos mitocondriales . [30] Castello (2018) reconoció 30 subespecies del zorro rojo del Viejo Mundo y nueve subespecies del zorro rojo norteamericano como válidas. [31]

Se sabe que existe una importante mezcla de genes entre diferentes subespecies; los zorros rojos británicos se han cruzado extensamente con zorros rojos importados de Alemania, Francia, Bélgica, Cerdeña y posiblemente Siberia y Escandinavia. [32] : 140 Sin embargo, los estudios genéticos sugieren muy pocas diferencias entre los zorros rojos muestreados en toda Europa. [33] [34] La falta de diversidad genética es consistente con el hecho de que el zorro rojo es una especie muy ágil, con un zorro rojo cubriendo 320 km (200 mi) en menos de un año. [35]

Las subespecies de zorro rojo en Eurasia y el norte de África se dividen en dos categorías: [7]

Los zorros rojos que viven en Asia Central muestran rasgos físicos intermedios entre los zorros del norte y los zorros grises del desierto del sur. [7]

El zorro rojo tiene un cuerpo alargado y extremidades relativamente cortas. La cola, que es más larga que la mitad de la longitud del cuerpo [7] (70 por ciento de la longitud de la cabeza y el cuerpo), [46] es esponjosa y llega al suelo cuando está de pie. Sus pupilas son ovaladas y están orientadas verticalmente. [7] Tienen membranas nictitantes , pero se mueven solo cuando los ojos están cerrados. Las patas delanteras tienen cinco dedos, mientras que las traseras tienen solo cuatro y carecen de espolones . [9] Son muy ágiles, capaces de saltar vallas de 2 m (6 pies 7 pulgadas) de altura, y nadan bien. [47] Las zorras normalmente tienen cuatro pares de pezones , [7] aunque no son infrecuentes las zorras con siete, nueve o diez pezones. [9] Los testículos de los machos son más pequeños que los de los zorros árticos. [7]

Sus cráneos son bastante estrechos y alargados, con pequeñas cajas craneales . Sus dientes caninos son relativamente largos. El dimorfismo sexual del cráneo es más pronunciado que en los zorros corsac, y las hembras de zorros rojos tienden a tener cráneos más pequeños que los machos, con regiones nasales más anchas y paladares duros , además de tener caninos más grandes. [7] Sus cráneos se distinguen de los de los perros por sus hocicos más estrechos, premolares menos apiñados , dientes caninos más delgados y perfiles cóncavos en lugar de convexos. [9]

Los zorros rojos son la especie más grande del género Vulpes . [48] Sin embargo, en relación con las dimensiones, los zorros rojos son mucho más ligeros que los perros de tamaño similar del género Canis . Los huesos de sus extremidades, por ejemplo, pesan un 30 por ciento menos por unidad de área de hueso de lo esperado para perros de tamaño similar. [49] : 122 Muestran una variación significativa individual, sexual, de edad y geográfica en el tamaño. En promedio, los adultos miden 35-50 cm (14-20 pulgadas) de alto en el hombro y 45-90 cm (18-35 pulgadas) de longitud corporal con colas que miden 30-55,5 cm (11,8-21,9 pulgadas). Las orejas miden 7,7-12,5 cm (3,0-4,9 pulgadas) y las patas traseras 12-18,5 cm (4,7-7,3 pulgadas). Los pesos varían de 2,2 a 14 kg (4,9 a 30,9 lb), y las zorras suelen pesar entre un 15 y un 20 % menos que los machos. [50] [51] Los zorros rojos adultos tienen cráneos que miden entre 129 y 167 mm (5,1 a 6,6 pulgadas), mientras que los de las zorras miden entre 128 y 159 mm (5,0 a 6,3 pulgadas). [7] La huella de la pata delantera mide 60 mm (2,4 pulgadas) de largo y 45 mm (1,8 pulgadas) de ancho, mientras que la huella de la pata trasera mide 55 mm (2,2 pulgadas) de largo y 38 mm (1,5 pulgadas) de ancho. Trotan a una velocidad de 6 a 13 km/h (3,7 a 8,1 mph) y tienen una velocidad máxima de carrera de 50 km/h (31 mph). Tienen una zancada de 25-35 cm (9,8-13,8 pulgadas) cuando caminan a un ritmo normal. [49] : 36 Los zorros rojos norteamericanos son generalmente de constitución ligera, con cuerpos comparativamente largos para su masa y tienen un alto grado de dimorfismo sexual. Los zorros rojos británicos son de constitución robusta, pero bajos, mientras que los zorros rojos de Europa continental están más cerca del promedio general entre las poblaciones de zorros rojos. [52] El zorro rojo más grande registrado en Gran Bretaña fue un macho de 1,4 m (4 pies 7 pulgadas) de largo, que pesaba 17,2 kg (38 libras), asesinado en Aberdeenshire , Escocia, a principios de 2012. [53]

El pelaje de invierno es denso, suave, sedoso y relativamente largo. En los zorros del norte, el pelaje es muy largo, denso y esponjoso, pero es más corto, más escaso y más grueso en las formas del sur. [7] Entre los zorros del norte, las variedades norteamericanas generalmente tienen los pelos de protección más sedosos , [13] : 231 mientras que la mayoría de los zorros rojos euroasiáticos tienen un pelaje más grueso. [13] : 235 El pelaje en las áreas de "ventanas térmicas" como la cabeza y la parte inferior de las piernas se mantiene denso y corto durante todo el año, mientras que el pelaje en otras áreas cambia con las estaciones. Los zorros controlan activamente la vasodilatación periférica y la vasoconstricción periférica en estas áreas para regular la pérdida de calor. [54] Hay tres morfos de color principales ; rojo, plateado/negro y cruzado (ver Mutaciones ). [46] En el morfo rojo típico, sus pelajes son generalmente de color rojizo-oxidado brillante con tintes amarillentos. A lo largo de la columna vertebral se encuentra una franja difusa de pelos de color marrón rojizo y castaño. Dos franjas adicionales pasan por los omoplatos y, junto con la franja espinal, forman una cruz. La parte inferior de la espalda suele ser de un color plateado moteado. Los flancos son de un color más claro que la espalda, mientras que el mentón, los labios inferiores, la garganta y la parte delantera del pecho son blancos. El resto de la superficie inferior del cuerpo es oscura, marrón o rojiza. [7] Durante la lactancia, el pelaje del vientre de las zorras puede volverse rojo ladrillo. [9] Las partes superiores de las extremidades son de un color rojizo oxidado, mientras que las patas son negras. La parte frontal de la cara y la parte superior del cuello son de un rojo oxidado marrón brillante, mientras que los labios superiores son blancos. La parte posterior de las orejas es negra o marrón rojiza, mientras que la superficie interna es blanquecina. La parte superior de la cola es marrón rojiza, pero de un color más claro que la espalda y los flancos. La parte inferior de la cola es gris pálido con un tinte de color paja. En la base de la cola suele haber una mancha negra, donde se encuentra la glándula supracaudal . La punta de la cola es blanca. [7]

La coloración atípica en el zorro rojo generalmente representa etapas hacia el melanismo completo , [7] y ocurre principalmente en regiones frías. [10]

Los zorros rojos tienen visión binocular , [9] pero su vista reacciona principalmente al movimiento. Su percepción auditiva es aguda, pudiendo oír al urogallo negro cambiando de refugio a 600 pasos, el vuelo de los cuervos a 0,25-0,5 km (0,16-0,31 mi) y el chillido de los ratones a unos 100 m (330 ft). [7] Son capaces de localizar sonidos con un margen de error de un grado a 700-3000 Hz, aunque con menor precisión a frecuencias más altas. [47] Su sentido del olfato es bueno, pero más débil que el de los perros especializados. [7]

Los zorros rojos tienen un par de sacos anales revestidos por glándulas sebáceas, ambos de los cuales se abren a través de un solo conducto. [55] El tamaño y el volumen de los sacos anales aumentan con la edad, variando en tamaño de 5 a 40 mm de longitud, 1 a 3 mm de diámetro y con una capacidad de 1 a 5 ml. [56] Los sacos anales actúan como cámaras de fermentación en las que las bacterias aeróbicas y anaeróbicas convierten el sebo en compuestos olorosos, incluidos los ácidos alifáticos . La glándula caudal de forma ovalada mide 25 mm (0,98 pulgadas) de largo y 13 mm (0,51 pulgadas) de ancho, y se dice que huele a violetas . [7] La presencia de glándulas en los pies es equívoca. Las cavidades interdigitales son profundas, con un tinte rojizo y huelen fuertemente. Las glándulas sebáceas están presentes en el ángulo de la mandíbula y la mandíbula. [9]

El zorro rojo es una especie con una amplia distribución geográfica. Su área de distribución cubre casi 70 000 000 km2 ( 27 000 000 millas cuadradas), incluyendo lugares tan al norte como el Círculo Polar Ártico . Se encuentra en toda Europa, en África al norte del desierto del Sahara, en toda Asia, excepto en el extremo sudeste asiático, y en toda América del Norte, excepto en la mayor parte del suroeste de los Estados Unidos y México. Está ausente en Groenlandia , Islandia , las islas del Ártico, las partes más septentrionales de Siberia central y en desiertos extremos. [1] No está presente en Nueva Zelanda y está clasificado como un "organismo nuevo prohibido" según la Ley de Sustancias Peligrosas y Nuevos Organismos de 1996 , que no permite su importación. [57]

En Australia, las estimaciones de 2012 indicaron que había más de 7,2 millones de zorros rojos, [58] con un área de distribución que se extendía por la mayor parte del continente. [49] : 14 Se establecieron en Australia a través de introducciones sucesivas en las décadas de 1830 y 1840, por colonos en las colonias británicas de Van Diemen's Land (ya en 1833) y el distrito de Port Phillip de Nueva Gales del Sur (ya en 1845), que querían fomentar el deporte tradicional inglés de la caza del zorro . Una población permanente de zorros rojos no se estableció en la isla de Tasmania , y se sostiene ampliamente que los zorros fueron superados por el diablo de Tasmania . [59] Sin embargo, en el continente, la especie tuvo éxito como depredador superior . El zorro es generalmente menos común en áreas donde el dingo es más frecuente, pero ha logrado, principalmente a través de su comportamiento de excavación, diferenciarse de nicho tanto con el perro como con el gato salvajes . En consecuencia, el zorro se ha convertido en una de las especies invasoras más destructivas del continente. [ cita requerida ]

El zorro rojo ha sido implicado en la extinción o declive de varias especies nativas de Australia, particularmente las de la familia Potoroidae , incluyendo la rata-canguro del desierto . [60] La propagación de los zorros rojos a través de la parte sur del continente ha coincidido con la propagación de los conejos en Australia , y se corresponde con disminuciones en la distribución de varios mamíferos terrestres de tamaño mediano, incluyendo bettongs de cola de cepillo , bettongs madrigueras , bettongs rufos , bilbies , numbats , ualabíes de cola de uña con bridas y quokkas . [61] La mayoría de esas especies ahora están limitadas a áreas (como islas) donde los zorros rojos están ausentes o son raros. Existen programas locales de erradicación del zorro, aunque la eliminación ha demostrado ser difícil debido al comportamiento de madriguera del zorro y la caza nocturna, por lo que el enfoque está en la gestión, incluida la introducción de recompensas estatales. [62] Según el gobierno de Tasmania, los zorros rojos fueron introducidos accidentalmente en la isla de Tasmania, anteriormente libre de zorros, en 1999 o 2000, lo que representó una amenaza significativa para la vida silvestre nativa, incluido el bettong oriental , y se inició un programa de erradicación, llevado a cabo por el Departamento de Industrias Primarias y Agua de Tasmania . [63]

El origen de la subespecie ichnusae en Cerdeña , Italia, es incierto, ya que no se encuentra en depósitos del Pleistoceno en su tierra natal actual. Es posible que se originara durante el Neolítico después de su introducción a la isla por los humanos. Es probable entonces que las poblaciones de zorros sardos provengan de repetidas introducciones de animales de diferentes localidades en el Mediterráneo. Esta última teoría puede explicar la diversidad fenotípica de la subespecie. [22]

.jpg/440px-Young_Fox_(16605353545).jpg)

Los zorros rojos establecen áreas de distribución estables dentro de áreas particulares o son itinerantes sin morada fija. [49] : 117 Usan su orina para marcar sus territorios . [64] [65] Un zorro macho levanta una pata trasera y su orina se rocía hacia adelante frente a él, mientras que una zorra hembra se agacha para que la orina se rocíe en el suelo entre las patas traseras. [66] La orina también se usa para marcar sitios de escondite vacíos , utilizados para almacenar comida encontrada, como recordatorios para no perder el tiempo investigándolos. [49] : 125 [67] [68] Los machos generalmente tienen tasas más altas de marcado con orina durante fines del verano y el otoño, pero el resto del año las tasas entre machos y hembras son similares. [69] El uso de hasta 12 posturas de micción diferentes les permite controlar con precisión la posición de la marca de olor. [70] Los zorros rojos viven en grupos familiares que comparten un territorio conjunto. En hábitats favorables y/o áreas con baja presión de caza, los zorros subordinados pueden estar presentes en un área de distribución. Los zorros subordinados pueden ser uno o dos, a veces hasta ocho en un territorio. Estos subordinados podrían ser animales anteriormente dominantes , pero en su mayoría son crías del año anterior, que actúan como ayudantes en la crianza de las crías de la zorra reproductora. Alternativamente, su presencia se ha explicado como una respuesta a excedentes temporales de alimentos no relacionados con la asistencia al éxito reproductivo. Las zorras no reproductoras vigilarán, jugarán, acicalarán, aprovisionarán y recuperarán a las crías, [9] un ejemplo de selección de parentesco . Los zorros rojos pueden abandonar a sus familias una vez que alcanzan la edad adulta si las posibilidades de ganar un territorio propio son altas. Si no es así, se quedarán con sus padres, a costa de posponer su propia reproducción. [49] : 140–141

.jpg/440px-Red_foxes_mating_(2).jpg)

Los zorros rojos se reproducen una vez al año en primavera. Dos meses antes del celo (normalmente en diciembre), los órganos reproductores de las zorras cambian de forma y tamaño. Cuando entran en el período de celo, sus cuernos uterinos duplican su tamaño y sus ovarios crecen entre 1,5 y 2 veces más. La formación de esperma en los machos comienza en agosto-septiembre, y los testículos alcanzan su mayor peso en diciembre-febrero. [7] El período de celo de la zorra dura tres semanas, [9] durante las cuales los zorros caninos se aparean con las zorras durante varios días, a menudo en madrigueras.El bulbo glandular del macho se agranda durante la cópula , [10] formando un vínculo copulatorio que puede durar más de una hora. [9] El período de gestación dura entre 49 y 58 días. [7] Aunque los zorros son en gran medida monógamos , [71] la evidencia de ADN de una población indicó grandes niveles de poligamia , incesto y camadas de paternidad mixta. [9] Las zorras subordinadas pueden quedar embarazadas, pero por lo general no logran parir, o sus crías son asesinadas después del parto por la hembra dominante u otras subordinadas. [9]

El tamaño medio de la camada consiste en cuatro a seis crías, aunque se han producido camadas de hasta 13 crías. [7] Las camadas grandes son típicas en áreas donde la mortalidad de zorros es alta. [49] : 93 Las crías nacen ciegas, sordas y sin dientes, con un pelaje esponjoso de color marrón oscuro. Al nacer, pesan 56-110 g (2,0-3,9 oz) y miden 14,5 cm (5,7 pulgadas) de longitud corporal y 7,5 cm (3,0 pulgadas) de longitud de cola. Al nacer, tienen patas cortas, cabeza grande y pechos anchos. [7] Las madres permanecen con las crías durante 2-3 semanas, ya que no pueden termorregularse . Durante este período, los padres o las zorras estériles alimentan a las madres. [9] Las zorras son muy protectoras de sus crías, y se sabe que incluso luchan contra los terriers en su defensa. [32] : 21–22 Si la madre muere antes de que los cachorros sean independientes, el padre se hace cargo de su cuidado. [32] : 13 Los ojos de los cachorros se abren después de 13-15 días, tiempo durante el cual sus canales auditivos se abren y sus dientes superiores erupcionan, y los dientes inferiores emergen 3-4 días después. [7] Sus ojos son inicialmente azules, pero cambian a ámbar a las 4-5 semanas. El color del pelaje comienza a cambiar a las tres semanas de edad, cuando aparece la raya negra del ojo. Al mes, se ven manchas rojas y blancas en sus caras. Durante este tiempo, sus orejas se erigen y sus hocicos se alargan. [9] Los cachorros comienzan a dejar sus guaridas y a experimentar con alimentos sólidos traídos por sus padres a la edad de 3-4 semanas. El período de lactancia dura 6-7 semanas. [7] Sus pelajes lanudos comienzan a estar cubiertos por pelos de protección brillantes después de 8 semanas. [9] A la edad de 3-4 meses, las crías tienen patas largas, pecho estrecho y fibrosas. Alcanzan proporciones adultas a la edad de 6-7 meses. [7] Algunas zorras pueden alcanzar la madurez sexual a la edad de 9-10 meses, por lo que dan a luz a su primera camada al año de edad. [7] En cautiverio, su longevidad puede ser de hasta 15 años, aunque en estado salvaje por lo general no sobreviven más allá de los 5 años de edad. [72]

Fuera de la temporada de cría , la mayoría de los zorros rojos prefieren vivir al aire libre, en áreas con vegetación densa, aunque pueden entrar en madrigueras para escapar del mal tiempo. [9] Sus madrigueras a menudo se excavan en laderas de colinas o montañas, barrancos, acantilados, orillas empinadas de cuerpos de agua, zanjas, depresiones, cunetas, en grietas de rocas y entornos humanos desatendidos. Los zorros rojos prefieren cavar sus madrigueras en suelos bien drenados. Las guaridas construidas entre las raíces de los árboles pueden durar décadas, mientras que las excavadas en las estepas duran solo varios años. [7] Pueden abandonar permanentemente sus guaridas durante los brotes de sarna , posiblemente como mecanismo de defensa contra la propagación de enfermedades. [9] En las regiones desérticas de Eurasia, los zorros pueden utilizar las madrigueras de lobos , puercoespines y otros mamíferos grandes, así como las excavadas por colonias de jerbos. En comparación con las madrigueras construidas por zorros árticos, tejones, marmotas y zorros corsac, las madrigueras del zorro rojo no son demasiado complejas. Las madrigueras del zorro rojo se dividen en una madriguera y madrigueras temporales, que consisten solo en un pequeño pasaje o cueva para ocultarse. La entrada principal de la madriguera conduce hacia abajo (40–45°) y se ensancha en una madriguera, de la que se ramifican numerosos túneles laterales. La profundidad de la madriguera varía de 0,5 a 2,5 m (1 ft 8 in – 8 ft 2 in), rara vez se extiende hasta el agua subterránea . El pasaje principal puede alcanzar los 17 m (56 ft) de longitud, con una media de 5–7 m (16–23 ft). En primavera, los zorros rojos limpian sus madrigueras del exceso de tierra mediante movimientos rápidos, primero con las patas delanteras y luego con movimientos de patadas con las patas traseras, arrojando la tierra descartada a más de 2 m (6 ft 7 in) de la madriguera. Cuando nacen las crías, los desechos descartados son pisoteados, formando así un lugar donde las crías pueden jugar y recibir comida. [7] Pueden compartir sus guaridas con marmotas [10] o tejones. [7] A diferencia de los tejones, que limpian meticulosamente sus madrigueras y defecan en letrinas , los zorros rojos habitualmente dejan trozos de presa alrededor de sus guaridas. [32] : 15–17 El tiempo medio de sueño de un zorro rojo cautivo es de 9,8 horas al día. [73]

_WOB.JPG/440px-Lis_(Vulpes_vulpes)_WOB.JPG)

Red fox body language consists of movements of the ears, tail and postures, with their body markings emphasising certain gestures. Postures can be divided into aggressive/dominant and fearful/submissive categories. Some postures may blend the two together.[49]: 42–43 Inquisitive foxes will rotate and flick their ears whilst sniffing. Playful individuals will perk their ears and rise on their hind legs. Male foxes courting females, or after successfully evicting intruders, will turn their ears outwardly, and raise their tails in a horizontal position, with the tips raised upward. When afraid, red foxes grin in submission, arching their backs, curving their bodies, crouching their legs and lashing their tails back and forth with their ears pointing backwards and pressed against their skulls. When merely expressing submission to a dominant animal, the posture is similar, but without arching the back or curving the body. Submissive foxes will approach dominant animals in a low posture, so that their muzzles reach up in greeting. When two evenly matched foxes confront each other over food, they approach each other sideways and push against each other's flanks, betraying a mixture of fear and aggression through lashing tails and arched backs without crouching and pulling their ears back without flattening them against their skulls. When launching an assertive attack, red foxes approach directly rather than sideways, with their tails aloft and their ears rotated sideways.[49]: 43 During such fights, red foxes will stand on each other's upper bodies with their forelegs, using open mouthed threats. Such fights typically only occur among juveniles or adults of the same sex.[9]

Red foxes have a wide vocal range, and produce different sounds spanning five octaves, which grade into each other.[49]: 28 Recent analyses identify 12 different sounds produced by adults and 8 by kits.[9] The majority of sounds can be divided into "contact" and "interaction" calls. The former vary according to the distance between individuals, while the latter vary according to the level of aggression.[49]: 28

Another call that does not fit into the two categories is a long, drawn-out, monosyllabic "waaaaah" sound. As it is commonly heard during the breeding season, it is thought to be emitted by vixens summoning males. When danger is detected, foxes emit a monosyllabic bark. At close quarters, it is a muffled cough, while at long distances it is sharper. Kits make warbling whimpers when nursing, these calls being especially loud when they are dissatisfied.[49]: 28

Red foxes are omnivores with a highly varied diet.[74][75] Research conducted in the former Soviet Union showed red foxes consuming over 300 animal species and a few dozen species of plants.[7] They primarily feed on small rodents like voles, mice, ground squirrels, hamsters, gerbils, woodchucks, pocket gophers and deer mice.[7][10] Secondary prey species include birds (with Passeriformes, Galliformes and waterfowl predominating), leporids, porcupines, raccoons, opossums, reptiles, insects, other invertebrates, flotsam (marine mammals, fish and echinoderms) and carrion.[7][10][76] On very rare occasions, foxes may attack young or small ungulates.[7] They typically target mammals up to about 3.5 kg (7.7 lb) in weight, and they require 500 g (18 oz) of food daily.[47] Red foxes readily eat plant material and in some areas fruit can amount to 100% of their diet in autumn. Commonly consumed fruits include blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, cherries, persimmons, mulberries, apples, plums, grapes and acorns. Other plant material includes grasses, sedges and tubers.[10]

Red foxes are implicated in the predation of game and song birds, hares, rabbits, muskrats and young ungulates, particularly in preserves, reserves and hunting farms where ground-nesting birds are protected and raised, as well as in poultry farms.[7]

While the popular consensus is that olfaction is very important for hunting,[77] two studies that experimentally investigated the role of olfactory, auditory and visual cues found that visual cues are the most important ones for hunting in red foxes[78] and coyotes.[79][80]

Red foxes prefer to hunt in the early morning hours before sunrise and late evening.[7] Although they typically forage alone, they may aggregate in resource-rich environments.[72] When hunting mouse-like prey, they first pinpoint their prey's location by sound, then leap, sailing high above their quarry, steering in mid-air with their tails, before landing on target up to 5 m (16 ft) away.[1] They typically only feed on carrion in the late evening hours and at night.[7] They are extremely possessive of their food and will defend their catches from even dominant animals.[49]: 58 Red foxes may occasionally commit acts of surplus killing; during one breeding season, four red foxes were recorded to have killed around 200 black-headed gulls each, with peaks during dark, windy hours when flying conditions were unfavourable. Losses to poultry and penned game birds can be substantial because of this.[9][49]: 164 Red foxes seem to dislike the taste of moles, but will nonetheless catch them alive and present them to their kits as playthings.[49]: 41

A 2008–2010 study of 84 red foxes in the Czech Republic and Germany found that successful hunting in long vegetation or under snow appeared to involve an alignment of the red fox with the Earth's magnetic field.[81][82]

Red foxes typically dominate other fox species. Arctic foxes generally escape competition from red foxes by living farther north, where food is too scarce to support the larger-bodied red species. Although the red species' northern limit is linked to the availability of food, the Arctic species' southern range is limited by the presence of the former. Red and Arctic foxes were both introduced to almost every island from the Aleutian Islands to the Alexander Archipelago during the 1830s–1930s by fur companies. The red foxes invariably displaced the Arctic foxes, with one male red fox having been reported to have killed off all resident Arctic foxes on a small island in 1866.[49]: 85 Where they are sympatric, Arctic foxes may also escape competition by feeding on lemmings and flotsam rather than voles, as favoured by red foxes. Both species will kill each other's kits, given the opportunity.[7] Red foxes are serious competitors of corsac foxes, as they hunt the same prey all year. The red species is also stronger, is better adapted to hunting in snow deeper than 10 cm (3.9 in) and is more effective in hunting and catching medium-sized to large rodents. Corsac foxes seem to only outcompete red foxes in semi-desert and steppe areas.[7][83] In Israel, Blanford's foxes escape competition with red foxes by restricting themselves to rocky cliffs and actively avoiding the open plains inhabited by red foxes.[49]: 84–85 Red foxes dominate kit and swift foxes. Kit foxes usually avoid competition with their larger cousins by living in more arid environments, though red foxes have been increasing in ranges formerly occupied by kit foxes due to human-induced environmental changes. Red foxes will kill both species and compete with them for food and den sites.[10] Grey foxes are exceptional, as they dominate red foxes wherever their ranges meet. Historically, interactions between the two species were rare, as grey foxes favoured heavily wooded or semiarid habitats as opposed to the open and mesic ones preferred by red foxes. However, interactions have become more frequent due to deforestation, allowing red foxes to colonise grey fox-inhabited areas.[10]

Wolves may kill and eat red foxes in disputes over carcasses.[7][84] In areas in North America where red fox and coyote populations are sympatric, red fox ranges tend to be located outside coyote territories. The principal cause of this separation is believed to be active avoidance of coyotes by the red foxes. Interactions between the two species vary in nature, ranging from active antagonism to indifference. The majority of aggressive encounters are initiated by coyotes, and there are few reports of red foxes acting aggressively toward coyotes except when attacked or when their kits were approached. Foxes and coyotes have sometimes been seen feeding together.[85] In Israel, red foxes share their habitat with golden jackals. Where their ranges meet, the two canids compete due to near-identical diets. Red foxes ignore golden jackal scents or tracks in their territories and avoid close physical proximity with golden jackals themselves. In areas where golden jackals become very abundant, the population of red foxes decreases significantly, apparently because of competitive exclusion.[86] However, there is one record of multiple red foxes interacting peacefully with a golden jackal in southwestern Germany.[87]

.jpg/440px-Aquila_chrysaetos_1_(Bohuš_Číčel).jpg)

Red foxes dominate raccoon dogs, sometimes killing their kits or biting adults to death. Cases are known of red foxes killing raccoon dogs after entering their dens. Both species compete for mouse-like prey. This competition reaches a peak during early spring when food is scarce. In Tatarstan, red fox predation accounted for 11.1% of deaths among 54 raccoon dogs and amounted to 14.3% of 186 raccoon dog deaths in northwestern Russia.[7]

Red foxes may kill small mustelids like weasels,[10] stone martens,[88] pine martens (martes martes), stoats, Siberian weasels, polecats and young sables. Eurasian badgers may live alongside red foxes in isolated sections of large burrows.[7] It is possible that the two species tolerate each other out of mutualism; red foxes provide Eurasian badgers with food scraps, while Eurasian badgers maintain the shared burrow's cleanliness.[32]: 15 However, cases are known of Eurasian badgers driving vixens from their dens and destroying their litters without eating them.[89] Wolverines may kill red foxes, often while the latter is sleeping or near carrion.[7]: 546 Red foxes, in turn, may kill young wolverines.[90]

Red foxes may compete with striped hyenas on large carcasses. Red foxes may give way to striped hyenas on unopened carcasses, as the latter's stronger jaws can easily tear open flesh that is too tough for red foxes. Red foxes may harass striped hyenas, using their smaller size and greater speed to avoid the hyena's attacks. Sometimes, red foxes seem to deliberately torment striped hyenas even when there is no food at stake. Some red foxes may mistime their attacks and are killed.[49]: 77–79 Red fox remains are often found in striped hyena dens and striped hyenas may steal red foxes from traps.[7]

In Eurasia, red foxes may be preyed upon by leopards, caracals and Eurasian lynxes. The Eurasian lynxes chase red foxes into deep snow, where their long legs and larger paws give them an advantage over red foxes, especially when the depth of the snow exceeds one meter.[7] In the Velikoluksky District in Russia, red foxes are absent or are seen only occasionally where Eurasian lynxes establish permanent territories.[7] Researchers consider Eurasian lynxes to represent considerably less danger to red foxes than wolves do.[7] North American felid predators of red foxes include cougars, Canada lynxes and bobcats.[46]

Red foxes compete with various birds of prey such as common buzzards (Buteo buteo) and northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis) and even steal their kills.[91][92] In turn, golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) regularly takes young red foxes and prey on adults if needed.[93][94] Other large eagles such as wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax), eastern imperial eagles (Aquila heliaca), white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla), and steller's sea eagles (Haliaeetus pelagicus) have also been known to kill red foxes less frequently.[95][96][97][98][99] Additionally, large owls such as Eurasian eagle-owls (Bubo bubo) and snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus) will prey on young foxes, and adults on exceptional occasions.[100][101][102]

Red foxes are the most important rabies vector in Europe. In London, arthritis is common in foxes, being particularly frequent in the spine.[9] Foxes may be infected with leptospirosis and tularemia, though they are not overly susceptible to the latter. They may also fall ill from listeriosis and spirochetosis, as well as acting as vectors in spreading erysipelas, brucellosis and tick-borne encephalitis. A mysterious fatal disease near Lake Sartlan in the Novosibirsk Oblast was noted among local red foxes, but the cause was undetermined. The possibility was considered that it was caused by an acute form of encephalomyelitis, which was first observed in captive-bred silver foxes. Individual cases of foxes infected with Yersinia pestis are known.[7]

Red foxes are not readily prone to infestation with fleas. Species like Spilopsyllus cuniculi are probably only caught from the fox's prey species, while others like Archaeopsylla erinacei are caught whilst traveling. Fleas that feed on red foxes include Pulex irritans, Ctenocephalides canis and Paraceras melis. Ticks such as Ixodes ricinus and I. hexagonus are not uncommon in red foxes, and are typically found on nursing vixens and kits still in their earths. The louse Trichodectes vulpis specifically targets red foxes, but is found infrequently. The mite Sarcoptes scabiei is the most important cause of mange in red foxes. It causes extensive hair loss, starting from the base of the tail and hindfeet, then the rump before moving on to the rest of the body. In the final stages of the condition, red foxes can lose most of their fur, 50% of their body weight and may gnaw at infected extremities. In the epizootic phase of the disease, it usually takes red foxes four months to die after infection. Other endoparasites include Demodex folliculorum, Notoderes, Otodectes cynotis (which is frequently found in the ear canal), Linguatula serrata (which infects the nasal passages) and ringworms.[7]

Up to 60 helminth species are known to infect captive-bred foxes in fur farms, while 20 are known in the wild. Several coccidian species of the genera Isospora and Eimeria are also known to infect them.[7] The most common nematode species found in red fox guts are Toxocara canis and Uncinaria stenocephala, Capillaria aerophila[103] and Crenosoma vulpis; the latter two infect their lungs and trachea.[104] Capillaria plica infects the red fox's bladder. Trichinella spiralis rarely affects them. The most common tapeworm species in red foxes are Taenia spiralis and T. pisiformis. Others include Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis. Eleven trematode species infect red foxes,[9] including Metorchis conjunctus.[105] A red fox from was found to be a host of intestinal parasitic acanthocephalan worms, Pachysentis canicola in Bushehr Province, Iran,[106] Pachysentis procumbens and Pachysentis ehrenbergi in both in Egypt.[107]

Red foxes feature prominently in the folklore and mythology of human cultures with which they are sympatric. In Greek mythology, the Teumessian fox,[108] or Cadmean vixen, was a gigantic fox that was destined never to be caught. The fox was one of the children of Echidna.[109]

In Celtic mythology, the red fox is a symbolic animal. In the Cotswolds, witches were thought to take the shape of foxes to steal butter from their neighbours.[110] In later European folklore, the figure of Reynard the Fox symbolises trickery and deceit. He originally appeared (then under the name of "Reinardus") as a secondary character in the 1150 poem "Ysengrimus". He reappeared in 1175 in Pierre Saint Cloud's Le Roman de Renart, and made his debut in England in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Nun's Priest's Tale. Many of Reynard's adventures may stem from actual observations on fox behaviour; he is an enemy of the wolf and has a fondness for blackberries and grapes.[49]: 32–33

Chinese folk tales tell of fox-spirits called huli jing that may have up to nine tails, or kumiho as they are known in Korea.[111] In Japanese mythology, the kitsune are fox-like spirits possessing magical abilities that increase with their age and wisdom. Foremost among these is the ability to assume human form. While some folktales speak of kitsune employing this ability to trick others, other stories portray them as faithful guardians, friends, lovers, and wives.[112] In Arab folklore, the fox is considered a cowardly, weak, deceitful, and cunning animal, said to feign death by filling its abdomen with air to appear bloated, then lies on its side, awaiting the approach of unwitting prey.[43] The animal's cunning was noted by the authors of the Bible who applied the word "fox" to false prophets (Ezekiel 13:4) and the hypocrisy of Herod Antipas (Luke 13:32).[113]

The cunning Fox is commonly found in Native American mythology, where it is portrayed as an almost constant companion to Coyote. Fox, however, is a deceitful companion that often steals Coyote's food. In the Achomawi creation myth, Fox and Coyote are the co-creators of the world, that leave just before the arrival of humans. The Yurok tribe believed that Fox, in anger, captured the Sun, and tied him to a hill, causing him to burn a great hole in the ground. An Inuit story tells of how Fox, portrayed as a beautiful woman, tricks a hunter into marrying her, only to resume her true form and leave after he offends her. A Menominee story tells of how Fox is an untrustworthy friend to Wolf.[114]

The earliest historical records of fox hunting come from the 4th century BC; Alexander the Great is known to have hunted foxes and a seal dated from 350 BC depicts a Persian horseman in the process of spearing a fox. Xenophon, who viewed hunting as part of a cultured man's education, advocated the killing of foxes as pests, as they distracted hounds from hares. The Romans were hunting foxes by AD 80. During the Dark Ages in Europe, foxes were considered secondary quarries, but gradually grew in importance. Cnut the Great re-classed foxes as Beasts of the Chase, a lower category of quarry than Beasts of Venery. Foxes were gradually hunted less as vermin and more as Beasts of the Chase, to the point that by the late 1200s, Edward I had a royal pack of foxhounds and a specialised fox huntsman. In this period, foxes were increasingly hunted above ground with hounds, rather than underground with terriers. Edward, Second Duke of York assisted the climb of foxes as more prestigious quarries in his The Master of Game. By the Renaissance, fox hunting became a traditional sport of the nobility. After the English Civil War caused a drop in deer populations, fox hunting grew in popularity. By the mid-1600s, Great Britain was divided into fox hunting territories, with the first fox hunting clubs being formed (the first was the Charlton Hunt Club in 1737). The popularity of fox hunting in Great Britain reached a peak during the 1700s.[49]: 21 Although already native to North America, red foxes from England were imported for sporting purposes to Virginia and Maryland in 1730 by prosperous tobacco planters.[115] These American fox hunters considered the red fox more sporting than the grey fox.[115]

The grays furnished more fun, the reds more excitement. The grays did not run so far, but usually kept near home, going in a circuit of six or eight miles. 'An old red, generally so called irrespective of age, as a tribute to his prowess, might lead the dogs all day, and end by losing them as evening fell, after taking them a dead stretch for thirty miles. The capture of a gray was what men boasted of; a chase after 'an old red' was what they 'yarned' about.[115]

Red foxes are still widely persecuted as pests, with human-caused deaths among the highest causes of mortality in the species. Annual red fox kills are: UK 21,500–25,000 (2000); Germany 600,000 (2000–2001); Austria 58,000 (2000–2001); Sweden 58,000 (1999–2000); Finland 56,000 (2000–2001); Denmark 50,000 (1976–1977); Switzerland 34,832 (2001); Norway 17,000 (2000–2001); Saskatchewan (Canada) 2,000 (2000–2001); Nova Scotia (Canada) 491 (2000–2001); Minnesota (US) 4,000–8,000 (average annual trapping harvest 2002–2009);[116] New Mexico (US) 69 (1999–2000).[88]

Red foxes are among the most important fur-bearing animals harvested by the fur trade. Their pelts are used for trimmings, scarfs, muffs, jackets and coats. They are principally used as trimming for both cloth coats and fur garments, including evening wraps.[13]: 229–230 The pelts of silver foxes are popular as capes,[13]: 246 while cross foxes are mostly used for scarves and rarely for trimming.[13]: 252 The number of sold fox scarves exceeds the total number of scarves made from other fur-bearers. However, this amount is overshadowed by the total number of red fox pelts used for trimming purposes.[13]: 229–230 The silver colour morphs are the most valued by furriers, followed by the cross colour morphs and the red colour morphs, respectively.[32]: 207 In the early 1900s, over 1,000 American red fox skins were imported to Great Britain annually, while 500,000 were exported annually from Germany and Russia.[32]: 6 The total worldwide trade of wild red foxes in 1985–86 was 1,543,995 pelts. Red foxes amounted to 45% of U.S. wild-caught pelts worth $50 million.[88] Pelt prices are increasing, with 2012 North American wholesale auction prices averaging $39 and 2013 prices averaging $65.78.[117]

North American red foxes, particularly those of northern Alaska, are the most valued for their fur, as they have guard hairs of a silky texture which, after dressing, allow the wearer unrestricted mobility. Red foxes living in southern Alaska's coastal areas and the Aleutian Islands are an exception, as they have extremely coarse pelts that rarely exceed one-third of the price of their northern Alaskan cousins.[13]: 231 Most European peltries have coarse-textured fur compared to North American varieties. The only exceptions are the Nordic and Far Eastern Russian peltries, but they are still inferior to North American peltries in terms of silkiness.[13]: 235

Red foxes may on occasion prey on lambs. Usually, lambs targeted by red foxes tend to be physically weakened specimens, but not always. Lambs belonging to small breeds, such as the Scottish Blackface, are more vulnerable than larger breeds, such as the Merino. Twins may be more vulnerable to red foxes than singlets, as ewes cannot effectively defend both simultaneously. Crossbreeding small, upland ewes with larger, lowland rams can cause difficult and prolonged labour for ewes due to the heaviness of the resulting offspring, thus making the lambs more at risk to red fox predation. Lambs born from gimmers (ewes breeding for the first time) are more often killed by red foxes than those of experienced mothers, who stick closer to their young.[49]: 166–167

Red foxes may prey on domestic rabbits and guinea pigs if they are kept in open runs or are allowed to range freely in gardens. This problem is usually averted by housing them in robust hutches and runs. Urban red foxes frequently encounter cats and may feed alongside them. In physical confrontations, the cats usually have the upper hand. Authenticated cases of red foxes killing cats usually involve kittens. Although most red foxes do not prey on cats, some may do so and may treat them more as competitors rather than food.[49]: 180–181

.jpg/440px-A_tame_fox_cub_at_home_with_Mr_and_Mrs_Gordon_Jones,_Talysarn_(4478261667).jpg)

In their unmodified wild state, red foxes are generally unsuitable as pets.[118] Many supposedly abandoned kits are adopted by well-meaning people during the spring period, though it is unlikely that vixens would abandon their young. Actual orphans are rare and the ones that are adopted are likely kits that simply strayed from their den sites.[119] Kits require almost constant supervision; when still suckling, they require milk at four-hour intervals day and night. Once weaned, they may become destructive to leather objects, furniture and electric cables.[49]: 56 Though generally friendly toward people when young, captive red foxes become fearful of humans, save for their handlers, once they reach 10 weeks of age.[49]: 61 They maintain their wild counterparts' strong instinct of concealment and may pose a threat to domestic birds, even when well-fed.[32]: 122 Although suspicious of strangers, they can form bonds with cats and dogs, even ones bred for fox hunting. Tame red foxes were once used to draw ducks close to hunting blinds.[32]: 132–133

White to black individual red foxes have been selected and raised on fur farms as "silver foxes". In the second half of the 20th century, a lineage of domesticated silver foxes was developed by Russian geneticist Dmitry Belyayev who, over a 40-year period, bred several generations selecting only those individuals that showed the least fear of humans. Eventually, Belyayev's team selected only those that showed the most positive response to humans, thus resulting in a population of silver foxes whose behaviour and appearance was significantly changed. After about 10 generations of controlled breeding, these foxes no longer showed any fear of humans and often wagged their tails and licked their human caretakers to show affection. These behavioural changes were accompanied by physical alterations, which included piebald coats, floppy ears in kits and curled tails, similar to the traits that distinguish domestic dogs from grey wolves.[120]

Red foxes have been exceedingly successful in colonising built-up environments, especially lower-density suburbs,[47] although many have also been sighted in dense urban areas far from the countryside. Throughout the 20th century, they have established themselves in many Australian, European, Japanese and North American cities. The species first colonised British cities during the 1930s, entering Bristol and London during the 1940s, and later established themselves in Cambridge and Norwich. In Ireland, they are now common in suburban Dublin. In Australia, red foxes were recorded in Melbourne as early as the 1930s, while in Zurich, Switzerland, they only started appearing in the 1980s.[121] Urban red foxes are most common in residential suburbs consisting of privately owned, low-density housing. They are rare in areas where industry, commerce or council-rented houses predominate.[47] In these latter areas, the distribution is of a lower average density because they rely less on human resources; the home range of these foxes average from 80–90 ha (0.80–0.90 km2; 200–220 acres), whereas those in more residential areas average from 25–40 ha (0.25–0.40 km2; 62–99 acres).[122]

In 2006, it was estimated that there were 10,000 red foxes in London.[123] City-dwelling red foxes may have the potential to consistently grow larger than their rural counterparts as a result of abundant scraps and a relative lack of predators. In cities, red foxes may scavenge food from litter bins and bin bags, although much of their diet is similar to rural red foxes.[citation needed]

Urban red foxes are most active at dusk and dawn, doing most of their hunting and scavenging at these times. It is uncommon to spot them during the day, but they can be caught sunbathing on roofs of houses or sheds. Urban red foxes will often make their homes in hidden and undisturbed spots in urban areas as well as on the edges of a city, visiting at night for sustenance. They sleep at night in dens.

While urban red foxes will scavenge successfully in the city (and the red foxes tend to eat anything that humans eat) some urban residents will deliberately leave food out for the animals, finding them endearing. Doing this regularly can attract urban red foxes to one's home; they can become accustomed to human presence, warming up to their providers by allowing themselves to be approached and in some cases even played with, particularly young kits.[122]

Urban red foxes can cause problems for local residents. They have been known to steal chickens, disrupt rubbish bins and damage gardens. Most complaints about urban red foxes made to local authorities occur during the breeding season in late January/early February or from late April to August when the new kits are developing.[122]

In the U.K., hunting red foxes in urban areas is banned and shooting them in an urban environment is not suitable. One alternative to hunting urban red foxes has been to trap them, which appears to be a more viable method.[124] However, killing red foxes has little effect on the population in an urban area; those that are killed are very soon replaced, either by new kits during the breeding season or by other red foxes moving into the territory of those that were killed. A more effective method of urban red fox control is to deter them from the specific areas they inhabit. Deterrents such as creosote, diesel oil, or ammonia can be used. Cleaning up and blocking access to den locations can also discourage an urban red fox's return.[122]

In January 2014 it was reported that "Fleet", a relatively tame urban red fox tracked as part of a wider study by the University of Brighton in partnership with the BBC TV series Winterwatch, had unexpectedly traveled 195 miles in 21 days from his neighbourhood in Hove at the western edge of East Sussex across rural countryside as far as the town of Rye, near the eastern edge of the county. He was still continuing his journey when the GPS collar stopped transmitting due to suspected water damage. Along with setting a record for the longest journey undertaken by a tracked red fox in the United Kingdom, his travels have highlighted the fluidity of movement between rural and urban red fox populations.[125][126]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: Check |url= value (help)