La violencia doméstica es la violencia u otro abuso que ocurre en un entorno doméstico, como en un matrimonio o cohabitación . La violencia doméstica se utiliza a menudo como sinónimo de violencia de pareja , que es cometida por una de las personas en una relación íntima contra la otra persona, y puede tener lugar en relaciones o entre ex cónyuges o parejas. En su sentido más amplio, la violencia doméstica también implica violencia contra niños, padres o ancianos. Puede asumir múltiples formas, incluyendo abuso físico , verbal , emocional , económico , religioso , reproductivo , financiero o abuso sexual , o combinaciones de estos. Puede variar desde formas sutiles y coercitivas hasta violación marital y otros abusos físicos violentos, como estrangulamiento, palizas, mutilación genital femenina y lanzamiento de ácido que pueden resultar en desfiguración o muerte, e incluye el uso de tecnología para acosar, controlar, monitorear, acechar o hackear. [1] [2] El asesinato doméstico incluye la lapidación , la quema de novias , los crímenes de honor y la muerte por dote , que a veces involucra a miembros de la familia que no cohabitan. En 2015, el Ministerio del Interior del Reino Unido amplió la definición de violencia doméstica para incluir el control coercitivo. [3]

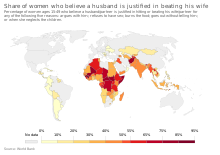

En todo el mundo, las víctimas de la violencia doméstica son en su gran mayoría mujeres, y ellas tienden a sufrir formas más graves de violencia. [4] [5] [6] [7] La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) estima que una de cada tres mujeres sufre violencia doméstica en algún momento de su vida. [8] En algunos países, la violencia doméstica puede considerarse justificada o legalmente permitida, en particular en casos de infidelidad real o presunta por parte de la mujer. Las investigaciones han establecido que existe una correlación directa y significativa entre el nivel de desigualdad de género de un país y las tasas de violencia doméstica, donde los países con menor igualdad de género experimentan tasas más altas de violencia doméstica. [9] La violencia doméstica es uno de los delitos menos denunciados en todo el mundo, tanto para hombres como para mujeres. [10] [11]

La violencia doméstica ocurre a menudo cuando el abusador cree que tiene derecho a ella, o que es aceptable, justificada o poco probable que se denuncie. Puede producir un ciclo intergeneracional de violencia en los niños y otros miembros de la familia, que pueden sentir que dicha violencia es aceptable o tolerada. Muchas personas no se reconocen a sí mismas como abusadores o víctimas, porque pueden considerar sus experiencias como conflictos familiares que se han salido de control. [12] La conciencia, la percepción, la definición y la documentación de la violencia doméstica difieren ampliamente de un país a otro. Además, la violencia doméstica a menudo ocurre en el contexto de matrimonios forzados o infantiles . [13]

En las relaciones abusivas, puede haber un ciclo de abuso durante el cual aumentan las tensiones y se comete un acto de violencia, seguido de un período de reconciliación y calma. Las víctimas pueden quedar atrapadas en situaciones de violencia doméstica a través del aislamiento , el poder y el control , el vínculo traumático con el abusador, [14] la aceptación cultural, la falta de recursos financieros, el miedo y la vergüenza , o para proteger a los niños. Como resultado del abuso, las víctimas pueden experimentar discapacidades físicas, agresión desregulada, problemas de salud crónicos, enfermedades mentales, finanzas limitadas y una capacidad deficiente para crear relaciones saludables. Las víctimas pueden experimentar trastornos psicológicos graves, como el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT). Los niños que viven en un hogar con violencia a menudo muestran problemas psicológicos desde una edad temprana, como la evitación, la hipervigilancia a las amenazas y la agresión desregulada, lo que puede contribuir a la traumatización indirecta. [15]

El primer uso conocido del término violencia doméstica en un contexto moderno, es decir, violencia en el hogar, fue en un discurso ante el Parlamento del Reino Unido por Jack Ashley en 1973. [16] [17] El término anteriormente se refería principalmente a disturbios civiles , violencia doméstica desde dentro de un país en oposición a la violencia internacional perpetrada por una potencia extranjera. [18] [19] [nb 1]

Tradicionalmente, la violencia doméstica (VD) se asociaba principalmente con la violencia física. Se utilizaban términos como abuso de esposa , maltrato de esposa , maltrato de esposa y mujer maltratada , pero han perdido popularidad debido a los esfuerzos por incluir a las parejas no casadas, el abuso que no sea físico, los perpetradores femeninos y las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo. [nb 2] La violencia doméstica ahora se define comúnmente de manera amplia para incluir "todos los actos de violencia física, sexual, psicológica o económica " [24] que pueden ser cometidos por un miembro de la familia o una pareja íntima. [24] [25] [26]

El término violencia de pareja se utiliza a menudo como sinónimo de abuso doméstico [27] o violencia doméstica , [28] pero se refiere específicamente a la violencia que ocurre dentro de la relación de pareja (es decir, matrimonio, cohabitación o parejas íntimas que no cohabitan). [29] A estos, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) agrega las conductas controladoras como una forma de abuso. [30] La violencia de pareja se ha observado en relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo y del sexo opuesto, [31] y en el primer caso tanto por parte de hombres contra mujeres como de mujeres contra hombres. [32] La violencia familiar es un término más amplio, que a menudo se utiliza para incluir el abuso infantil , el abuso de ancianos y otros actos violentos entre miembros de la familia. [28] [33] [34] En 1993, la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer definió la violencia doméstica como:

Violencia física, sexual y psicológica ocurrida en el seno de la familia, incluidos los golpes, el abuso sexual de las niñas en el hogar, la violencia relacionada con la dote , la violación conyugal, la mutilación genital femenina y otras prácticas tradicionales perjudiciales para la mujer, la violencia no conyugal y la violencia relacionada con la explotación. [35]

La Encyclopædia Britannica afirma que "a principios del siglo XIX, la mayoría de los sistemas legales aceptaban implícitamente que golpear a la esposa era un derecho del marido" sobre su esposa. [36] [37] El derecho consuetudinario inglés , que data del siglo XVI, trataba la violencia doméstica como un delito contra la comunidad en lugar de contra la mujer individual al acusar a golpear a la esposa de alterar el orden público . Las esposas tenían derecho a buscar reparación en forma de una fianza de un juez de paz local . Los procedimientos eran informales y extraoficiales, y ninguna guía legal especificaba el estándar de prueba o el grado de violencia que bastaría para una condena. Las dos sentencias típicas eran obligar al marido a pagar una fianza o obligarlo a hacer promesas de sus asociados para garantizar un buen comportamiento en el futuro. Las palizas también podían acusarse formalmente de agresión, aunque tales procesamientos eran poco frecuentes y, salvo en casos de lesiones graves o muerte, las sentencias eran típicamente multas pequeñas. [38]

Por extensión, este marco se mantuvo en las colonias americanas. El Cuerpo de Libertades de los colonos de la Bahía de Massachusetts de 1641 declaró que una mujer casada debía estar "libre de corrección corporal o azotes por parte de su marido". [39] New Hampshire y Rhode Island también prohibieron explícitamente los golpes a la esposa en sus códigos penales. [38]

Después de la Revolución Americana , los cambios en el sistema legal pusieron mayor poder en manos de los tribunales estatales que sentaban precedentes en lugar de los jueces locales. Muchos estados transfirieron la jurisdicción en casos de divorcio de sus legislaturas a su sistema judicial, y el recurso legal disponible para las mujeres maltratadas pasó a ser cada vez más el divorcio por motivos de crueldad y la demanda por agresión. Esto colocó una mayor carga de la prueba sobre la mujer, ya que necesitaba demostrar a un tribunal que su vida estaba en riesgo. En 1824, la Corte Suprema de Mississippi , citando la regla general , estableció un derecho positivo a golpear a la esposa en el caso State v. Bradley , un precedente que prevalecería en el derecho consuetudinario durante las décadas siguientes. [38]

La agitación política y el movimiento feminista de primera ola , durante el siglo XIX, llevaron a cambios tanto en la opinión popular como en la legislación sobre la violencia doméstica en el Reino Unido, los EE. UU. y otros países. [40] [41] En 1850, Tennessee se convirtió en el primer estado de los EE. UU. en prohibir explícitamente los golpes a la esposa. [42] [43] [44] Pronto le siguieron otros estados. [37] [45] En 1871, la marea de la opinión legal comenzó a volverse en contra de la idea de un derecho a golpear a la esposa, ya que los tribunales de Massachusetts y Alabama revirtieron el precedente establecido en Bradley . [38] En 1878, la Ley de Causas Matrimoniales del Reino Unido hizo posible que las mujeres en el Reino Unido buscaran la separación legal de un marido abusivo. [46] A fines de la década de 1870, la mayoría de los tribunales en los EE. UU. habían rechazado un supuesto derecho de los esposos a disciplinar físicamente a sus esposas. [47] A principios del siglo XX, los jueces paternalistas protegían regularmente a los perpetradores de violencia doméstica con el fin de reforzar las normas de género dentro de la familia. [48] En los casos de divorcio y violencia doméstica criminal, los jueces imponía castigos severos a los perpetradores masculinos, pero cuando se invertían los roles de género, a menudo daban poco o ningún castigo a las perpetradoras femeninas. [48] A principios del siglo XX, era común que la policía interviniera en casos de violencia doméstica en los EE. UU., pero los arrestos seguían siendo poco frecuentes. [49]

En la mayoría de los sistemas jurídicos del mundo, la violencia doméstica se ha abordado recién a partir de la década de 1990; de hecho, antes de fines del siglo XX, en la mayoría de los países había muy poca protección, en la ley o en la práctica, contra la violencia doméstica. [50] En 1993, la ONU publicó Estrategias para enfrentar la violencia doméstica: Manual de recursos . [51] Esta publicación instaba a los países de todo el mundo a tratar la violencia doméstica como un acto criminal, afirmaba que el derecho a una vida familiar privada no incluía el derecho a abusar de los miembros de la familia y reconocía que, en el momento de su redacción, la mayoría de los sistemas jurídicos consideraban que la violencia doméstica estaba en gran medida fuera del ámbito de aplicación de la ley, describiendo la situación en ese momento de la siguiente manera: "La disciplina física de los niños está permitida y, de hecho, se fomenta en muchos sistemas jurídicos y un gran número de países permiten el castigo físico moderado de una esposa o, si no lo hacen ahora, lo han hecho en los últimos 100 años. Una vez más, la mayoría de los sistemas jurídicos no penalizan las circunstancias en las que una esposa se ve obligada a tener relaciones sexuales con su marido contra su voluntad... De hecho, en el caso de la violencia contra las esposas, existe una creencia generalizada de que las mujeres provocan, pueden tolerar o incluso disfrutar de un cierto nivel de violencia por parte de sus cónyuges". [51]

En las últimas décadas, se ha pedido el fin de la impunidad legal de la violencia doméstica, una impunidad a menudo basada en la idea de que estos actos son privados. [52] [53] El Convenio del Consejo de Europa sobre prevención y lucha contra la violencia contra la mujer y la violencia doméstica , más conocido como el Convenio de Estambul, es el primer instrumento jurídicamente vinculante en Europa que trata de la violencia doméstica y la violencia contra la mujer. [54] El convenio busca poner fin a la tolerancia, en la ley o en la práctica, de la violencia contra la mujer y la violencia doméstica. En su informe explicativo, reconoce la larga tradición de los países europeos de ignorar, de iure o de facto , estas formas de violencia. [55] En el párrafo 219 se afirma: "Hay muchos ejemplos de la práctica anterior en los Estados miembros del Consejo de Europa que muestran que se hicieron excepciones al procesamiento de tales casos, ya sea en la ley o en la práctica, si la víctima y el perpetrador estaban, por ejemplo, casados entre sí o habían estado en una relación. El ejemplo más destacado es la violación dentro del matrimonio, que durante mucho tiempo no se había reconocido como violación debido a la relación entre la víctima y el perpetrador". [55]

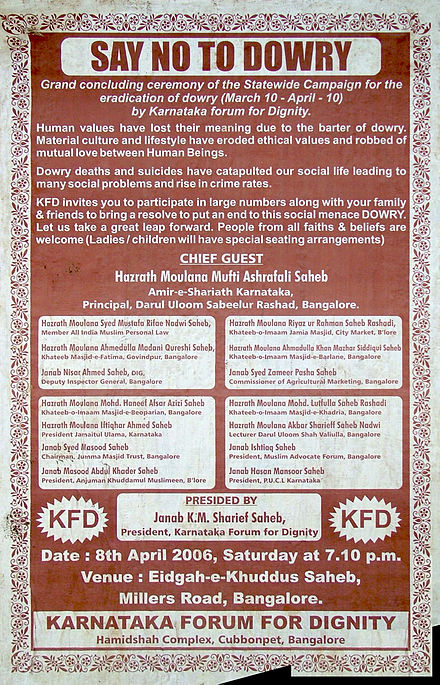

Se ha prestado mayor atención a formas específicas de violencia doméstica, como los crímenes de honor, las muertes por dote y los matrimonios forzados. En las últimas décadas, la India ha hecho esfuerzos para reducir la violencia relacionada con la dote: en 2005 se promulgó la Ley de Protección de las Mujeres contra la Violencia Doméstica , tras años de defensa y activismo por parte de las organizaciones de mujeres. [56] Los crímenes pasionales en América Latina, una región que tiene una historia de tratar este tipo de asesinatos con extrema indulgencia, también han llamado la atención internacional. En 2002, Widney Brown, director de defensa de derechos de Human Rights Watch, sostuvo que existen similitudes entre la dinámica de los crímenes pasionales y los crímenes de honor, afirmando que: "los crímenes pasionales tienen una dinámica similar [a los crímenes de honor] en el sentido de que las mujeres son asesinadas por miembros masculinos de la familia y los crímenes se perciben como excusables o comprensibles". [57]

Históricamente, los niños tenían pocas protecciones contra la violencia de sus padres y, en muchas partes del mundo, esto sigue siendo así. Por ejemplo, en la Antigua Roma, un padre podía matar legalmente a sus hijos. Muchas culturas han permitido a los padres vender a sus hijos como esclavos . El sacrificio de niños también era una práctica común. [58] El maltrato infantil comenzó a atraer la atención general con la publicación de "El síndrome del niño maltratado" por el psiquiatra pediátrico C. Henry Kempe en 1962. Antes de esto, las lesiones en los niños, incluso las fracturas óseas repetidas, no se reconocían comúnmente como resultado de un trauma intencional. En cambio, los médicos a menudo buscaban enfermedades óseas no diagnosticadas o aceptaban los relatos de los padres sobre accidentes accidentales, como caídas o agresiones por parte de matones del vecindario. [59] : 100–103

No toda la violencia doméstica es equivalente. Las diferencias en frecuencia, gravedad, propósito y resultado son todas significativas. La violencia doméstica puede adoptar muchas formas, incluida la agresión física o el asalto (golpes, patadas, mordeduras, empujones, inmovilizaciones, bofetadas, lanzamiento de objetos, palizas, etc.) o amenazas de los mismos; abuso sexual; control o dominio; intimidación ; acecho ; abuso pasivo/encubierto (por ejemplo, negligencia ); y privación económica. [60] [61] También puede significar poner en peligro a alguien, coerción criminal, secuestro, encarcelamiento ilegal, allanamiento y acoso . [62]

El abuso físico es el que implica un contacto destinado a causar miedo, dolor, lesiones, otro sufrimiento físico o daño corporal. [63] [64] En el contexto del control coercitivo, el abuso físico se utiliza para controlar a la víctima. [65] La dinámica del abuso físico en una relación suele ser compleja. La violencia física puede ser la culminación de otras conductas abusivas, como amenazas, intimidación y restricción de la autodeterminación de la víctima mediante el aislamiento, la manipulación y otras limitaciones de la libertad personal. [66] La negación de atención médica, la privación del sueño y el uso forzado de drogas o alcohol también son formas de abuso físico. [63] También puede incluir infligir lesiones físicas a otras personas, como niños o mascotas, con el fin de causar daño emocional a la víctima. [67]

El estrangulamiento en el contexto de la violencia doméstica ha recibido una atención significativa. [68] Ahora se reconoce como una de las formas más letales de violencia doméstica; sin embargo, debido a la falta de lesiones externas y la falta de conciencia social y capacitación médica al respecto, el estrangulamiento a menudo ha sido un problema oculto. [69] Como resultado, en los últimos años, muchos estados de EE. UU. han promulgado leyes específicas contra el estrangulamiento. [70]

Los homicidios como resultado de la violencia doméstica representan una mayor proporción de los homicidios de mujeres que de hombres. Más del 50% de los homicidios de mujeres son cometidos por parejas íntimas anteriores o actuales en los Estados Unidos. [71] En el Reino Unido, el 37% de las mujeres asesinadas fueron asesinadas por una pareja íntima, en comparación con el 6% de los hombres. Entre el 40 y el 70% de las mujeres asesinadas en Canadá, Australia, Sudáfrica, Israel y los Estados Unidos fueron asesinadas por una pareja íntima. [72] La OMS afirma que, a nivel mundial, alrededor del 38% de los homicidios de mujeres son cometidos por una pareja íntima. [73]

Durante el embarazo , la mujer corre un mayor riesgo de sufrir abusos, o los abusos de larga data pueden cambiar en gravedad y causar efectos negativos en la salud de la madre y el feto. [74] El embarazo también puede dar lugar a una pausa en la violencia doméstica cuando el abusador no quiere dañar al feto. El riesgo de violencia doméstica para las mujeres que han estado embarazadas es mayor inmediatamente después del parto . [75]

Los ataques con ácido son una forma extrema de violencia en la que se arroja ácido a las víctimas, generalmente a sus caras, lo que provoca daños extensos que incluyen ceguera a largo plazo y cicatrices permanentes . [76] [77] [78] [79] [80] Estos son comúnmente una forma de venganza contra una mujer por rechazar una propuesta de matrimonio o un avance sexual. [81] [82]

En Oriente Medio y otras partes del mundo, los homicidios domésticos planificados, o crímenes de honor , se llevan a cabo debido a la creencia de los perpetradores de que la víctima ha deshonrado a la familia o la comunidad. [83] [84] Según Human Rights Watch , los crímenes de honor generalmente se realizan contra mujeres por "negarse a contraer un matrimonio concertado , ser víctima de una agresión sexual , solicitar el divorcio" o ser acusadas de cometer adulterio . [85] En algunas partes del mundo, donde existe una fuerte expectativa social de que una mujer sea virgen antes del matrimonio, una novia puede ser sometida a violencia extrema, incluido un crimen de honor, si se considera que no es virgen en su noche de bodas debido a la ausencia de sangre. [86] [nb 3]

La quema de novias o asesinato por dote es una forma de violencia doméstica en la que una mujer recién casada es asesinada en su casa por su marido o la familia de su marido debido a su insatisfacción con la dote proporcionada por su familia. El acto suele ser el resultado de demandas de una dote mayor o más prolongada después del matrimonio. [102] La violencia por dote es más común en el sur de Asia , especialmente en la India. En 2011, la Oficina Nacional de Registros Criminales informó 8.618 muertes por dote en la India, pero las cifras no oficiales estiman al menos tres veces esa cantidad. [56]

La OMS define el abuso sexual como todo acto sexual, tentativa de consumar un acto sexual, comentarios o insinuaciones sexuales no deseados, o actos para comercializar o utilizar de cualquier otro modo la sexualidad de una persona mediante coacción . También incluye las inspecciones obligatorias de virginidad y la mutilación genital femenina. [105] Además de la iniciación del acto sexual mediante la fuerza física, el abuso sexual ocurre si una persona es presionada verbalmente para que consienta, [106] no puede comprender la naturaleza o condición del acto, no puede negarse a participar o no puede comunicar su falta de voluntad para participar en el acto sexual. Esto podría deberse a la inmadurez de la menor, enfermedad, discapacidad o la influencia del alcohol u otras drogas, o debido a la intimidación o presión. [107]

En muchas culturas, se considera que las víctimas de violación han deshonrado o deshonrado a sus familias y enfrentan una violencia familiar grave, incluidos los crímenes de honor. [108] Esto es especialmente así si la víctima queda embarazada. [109]

La OMS define la mutilación genital femenina como «todos los procedimientos que implican la extirpación parcial o total de los genitales externos femeninos u otras lesiones a los órganos genitales femeninos por razones no médicas». Este procedimiento se ha realizado en más de 125 millones de mujeres vivas en la actualidad y se concentra en 29 países de África y Oriente Medio. [110]

El incesto , o contacto sexual entre un adulto de la misma familia y un niño, es una forma de violencia sexual familiar. [111] En algunas culturas, existen formas ritualizadas de abuso sexual infantil que tienen lugar con el conocimiento y consentimiento de la familia, donde se induce al niño a participar en actos sexuales con adultos, posiblemente a cambio de dinero o bienes. Por ejemplo, en Malawi algunos padres hacen arreglos para que un hombre mayor, a menudo llamado hiena , tenga relaciones sexuales con sus hijas como una forma de iniciación. [112] [113] El Convenio del Consejo de Europa para la protección de los niños contra la explotación y el abuso sexual [114] fue el primer tratado internacional para abordar el abuso sexual infantil que ocurre dentro del hogar o la familia. [115]

La coerción reproductiva (también llamada reproducción forzada ) son amenazas o actos de violencia contra los derechos reproductivos, la salud y la toma de decisiones de una pareja; e incluye un conjunto de comportamientos destinados a presionar o coaccionar a una pareja para que se quede embarazada o ponga fin a un embarazo. [116] La coerción reproductiva está asociada con el sexo forzado, el miedo o la incapacidad de tomar una decisión anticonceptiva, el miedo a la violencia después de negarse a tener relaciones sexuales y la interferencia abusiva de la pareja con el acceso a la atención médica. [117] [118]

En algunas culturas, el matrimonio impone a las mujeres la obligación social de reproducirse. En el norte de Ghana, por ejemplo, el pago del precio de la novia significa que la mujer tiene la obligación de tener hijos, y las mujeres que utilizan métodos anticonceptivos se enfrentan a amenazas de violencia y represalias. [119] La OMS incluye el matrimonio forzado, la cohabitación y el embarazo , incluida la herencia de la esposa , dentro de su definición de violencia sexual. [120] [121] La herencia de la esposa, o matrimonio levirato , es un tipo de matrimonio en el que el hermano de un hombre fallecido está obligado a casarse con su viuda, y la viuda está obligada a casarse con el hermano de su marido fallecido.

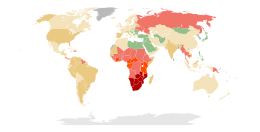

La violación conyugal es una penetración no consentida perpetrada contra un cónyuge. No se denuncia ni se persigue lo suficiente y es legal en muchos países, en parte debido a la creencia de que a través del matrimonio, una mujer da su consentimiento irrevocable para que su marido tenga relaciones sexuales con ella cuando lo desee. [122] [123] [124] [125] [126] En el Líbano , por ejemplo, mientras se debatía una propuesta de ley que penalizaría la violación conyugal, el jeque Ahmad Al-Kurdi, juez del tribunal religioso sunita , dijo que la ley "podría llevar al encarcelamiento del hombre cuando en realidad está ejerciendo el menor de sus derechos maritales". [127] Las feministas han trabajado sistemáticamente desde los años 1960 para penalizar la violación conyugal a nivel internacional. [128] En 2006, un estudio de la ONU concluyó que la violación conyugal era un delito perseguible en al menos 104 países. [129] La violación conyugal, que en el pasado era ampliamente tolerada o ignorada por la ley y la sociedad, ahora es repudiada por las convenciones internacionales y cada vez más criminalizada. Los países que ratificaron la Convención de Estambul, el primer instrumento jurídicamente vinculante en Europa en el ámbito de la violencia contra la mujer, [54] están obligados por sus disposiciones a garantizar que los actos sexuales no consentidos cometidos contra un cónyuge o pareja sean ilegales. [130] La Convención entró en vigor en agosto de 2014. [131]

El abuso emocional o psicológico es un patrón de comportamiento que amenaza, intimida, deshumaniza o socava sistemáticamente la autoestima. [132] Según el Convenio de Estambul, la violencia psicológica es “la conducta intencional encaminada a perjudicar gravemente la integridad psicológica de una persona mediante coacción o amenazas”. [133]

El abuso emocional incluye minimización, amenazas, aislamiento, humillación pública , crítica implacable, devaluación personal constante, control coercitivo, obstrucción repetida y manipulación psicológica . [30] [67] [134] [135] El acecho es una forma común de intimidación psicológica, y es perpetrado con mayor frecuencia por parejas íntimas anteriores o actuales. [136] [137] Las víctimas tienden a sentir que su pareja tiene un control casi total sobre ellas, lo que afecta en gran medida la dinámica de poder en una relación, empoderando al perpetrador y desempoderando a la víctima. [138] Las víctimas a menudo experimentan depresión , lo que las pone en mayor riesgo de trastornos alimentarios , [139] suicidio y abuso de drogas y alcohol . [138] [ fuente autopublicada? ] [140] [141] [142]

El control coercitivo implica un comportamiento controlador diseñado para hacer que una persona sea dependiente aislándola del apoyo, explotándola de su independencia y regulando sus actividades diarias. [135] Implica los actos de agresión verbal , castigo, humillación, amenazas o intimidación. El control coercitivo puede ocurrir físicamente, por ejemplo a través del abuso físico, dañando o asustando a las víctimas. [143] Los derechos humanos de la víctima pueden verse infringidos al ser privada de su derecho a la libertad y reducir su capacidad de actuar libremente. Los abusadores tienden a deshumanizar , hacer amenazas, privar de necesidades básicas y acceso personal, aislar y rastrear la agenda diaria de la víctima a través de software espía. [144] Las víctimas generalmente sienten una sensación de ansiedad y miedo que afecta gravemente su vida personal, financiera, física y psicológicamente.

El abuso económico (o abuso financiero) es una forma de abuso en la que uno de los miembros de la pareja tiene control sobre el acceso del otro a los recursos económicos. [145] Los bienes conyugales se utilizan como medio de control. El abuso económico puede implicar impedir que un cónyuge adquiera recursos, limitar lo que la víctima puede utilizar o explotar de otro modo los recursos económicos de la víctima. [145] [146] El abuso económico disminuye la capacidad de la víctima para mantenerse a sí misma, aumentando la dependencia del perpetrador, lo que incluye un acceso reducido a la educación, el empleo, el avance profesional y la adquisición de bienes. [145] [146] [147] Obligar o presionar a un miembro de la familia a firmar documentos, vender cosas o cambiar un testamento son formas de abuso económico. [64]

A la víctima se le puede asignar una asignación que le permita controlar de cerca cuánto dinero gasta, impidiendo que gaste sin el consentimiento del agresor, lo que lleva a la acumulación de deuda o al agotamiento de los ahorros de la víctima. [145] [146] [147] Los desacuerdos sobre el dinero gastado pueden dar lugar a represalias con más abusos físicos, sexuales o emocionales. [148] En partes del mundo donde las mujeres dependen de los ingresos de sus maridos para sobrevivir (debido a la falta de oportunidades de empleo femenino y la falta de bienestar estatal), el abuso económico puede tener consecuencias muy graves. Las relaciones abusivas se han asociado con la desnutrición tanto en las madres como en los niños. En la India, por ejemplo, la retención de alimentos es una forma documentada de abuso familiar. [149]

Uno de los factores más importantes en la violencia doméstica es la creencia de que el maltrato, ya sea físico o verbal, es aceptable. Otros factores de riesgo incluyen el abuso de sustancias, la falta de educación, los problemas de salud mental, la falta de habilidades para afrontar la situación, el maltrato infantil y la dependencia excesiva del maltratador. [150] [151]

Un motivo primordial para cometer actos de violencia doméstica e interpersonal en una relación es establecer y mantener relaciones basadas en el poder y el control sobre las víctimas. [152] [153] [154] [155]

La moralidad de los maltratadores no está en sintonía con la ley y los estándares de la sociedad. [156] Las investigaciones muestran que la cuestión clave para los perpetradores de abuso es su decisión consciente y deliberada de delinquir en la búsqueda de la autogratificación. [157]

Los hombres que perpetran violencia tienen características específicas: son narcisistas, carecen voluntariamente de empatía y eligen tratar sus necesidades como más importantes que las de los demás. [157] Los perpetradores manipulan psicológicamente a sus víctimas para hacerles creer que su abuso y violencia son causados por la incompetencia de la víctima (como esposa, amante o como ser humano) en lugar del deseo egoísta de los perpetradores de poder y control sobre ellos. [153]

Lenore E. Walker presentó el modelo de un ciclo de abuso que consta de cuatro fases. En primer lugar, hay una acumulación de abuso cuando la tensión aumenta hasta que se produce un incidente de violencia doméstica. Durante la etapa de reconciliación, el abusador puede ser amable y cariñoso y luego hay un período de calma. Cuando la situación está tranquila, la persona abusada puede tener la esperanza de que la situación cambie. Luego, las tensiones comienzan a acumularse y el ciclo comienza de nuevo. [158]

Un aspecto común entre los maltratadores es que fueron testigos de abusos en su infancia. Fueron participantes de una cadena de ciclos intergeneracionales de violencia doméstica. [159] Eso no significa, a la inversa, que si un niño es testigo o sujeto de violencia se convertirá en un maltratador. [150] Comprender y romper los patrones de abuso intergeneracional puede hacer más por reducir la violencia doméstica que otros remedios para manejar el abuso. [159]

Las respuestas que se centran en los niños sugieren que las experiencias vividas a lo largo de la vida influyen en la propensión de un individuo a participar en la violencia familiar (ya sea como víctima o como perpetrador). Los investigadores que apoyan esta teoría sugieren que es útil pensar en tres fuentes de violencia doméstica: la socialización infantil, las experiencias previas en relaciones de pareja durante la adolescencia y los niveles de tensión en la vida actual de una persona. Las personas que observan a sus padres maltratándose entre sí, o que han sido maltratadas ellas mismas, pueden incorporar el maltrato en su comportamiento dentro de las relaciones que establecen como adultos. [160] [161] [162]

Las investigaciones indican que cuanto más se castiga físicamente a los niños, más probabilidades hay de que, cuando sean adultos, actúen de forma violenta hacia los miembros de la familia, incluidas las parejas íntimas. [163] Las personas que reciben más azotes cuando son niños tienen más probabilidades de aprobar, cuando son adultos, que se golpee a una pareja, y también experimentan más conflictos maritales y sentimientos de ira en general. [164] Varios estudios han descubierto que el castigo físico está asociado con "niveles más altos de agresión contra los padres, hermanos, compañeros y cónyuges", incluso cuando se controlan otros factores. [165] Aunque estas asociaciones no prueban una relación causal , varios estudios longitudinales sugieren que la experiencia del castigo físico sí tiene un efecto causal directo sobre las conductas agresivas posteriores. Dichas investigaciones han demostrado que el castigo corporal de los niños (por ejemplo, cachetadas, bofetadas o azotes) predice una internalización más débil de valores como la empatía, el altruismo y la resistencia a la tentación, junto con una conducta más antisocial , incluida la violencia en el noviazgo. [166]

En algunas sociedades patrilineales del mundo, la novia joven se muda con la familia de su marido. Como nueva en el hogar, comienza ocupando la posición más baja (o una de las más bajas) en la familia, a menudo es objeto de violencia y abusos y, en particular, está fuertemente controlada por los suegros: con la llegada de la nuera a la familia, el estatus de la suegra se eleva y ahora tiene (a menudo por primera vez en su vida) un poder sustancial sobre otra persona, y "este sistema familiar en sí mismo tiende a producir un ciclo de violencia en el que la novia que antes había sido maltratada se convierte en la suegra maltratadora de su nueva nuera". [167] Amnistía Internacional escribe que, en Tayikistán, "es casi un ritual de iniciación para la suegra someter a su nuera a los mismos tormentos que ella misma sufrió cuando era una joven esposa". [168]

Estos factores incluyen la genética y la disfunción cerebral y son estudiados por la neurociencia . [169] Las teorías psicológicas se centran en los rasgos de personalidad y las características mentales del delincuente. Los rasgos de personalidad incluyen estallidos repentinos de ira , poco control de los impulsos y baja autoestima . Varias teorías sugieren que la psicopatología es un factor, y que el abuso experimentado en la infancia lleva a algunas personas a ser más violentas en la edad adulta. Se ha encontrado una correlación entre la delincuencia juvenil y la violencia doméstica en la edad adulta. [170]

Los estudios han encontrado una alta incidencia de psicopatología entre los maltratadores domésticos. [171] [172] [173] Por ejemplo, algunas investigaciones sugieren que alrededor del 80% de los hombres, tanto los que fueron derivados por los tribunales como los que se auto-refirieron en estos estudios de violencia doméstica, exhibieron psicopatología diagnosticable, típicamente trastornos de la personalidad . "La estimación de trastornos de la personalidad en la población general estaría más en el rango del 15-20%... A medida que la violencia se vuelve más severa y crónica en la relación, la probabilidad de psicopatología en estos hombres se acerca al 100%". [174]

Dutton ha sugerido un perfil psicológico de los hombres que maltratan a sus esposas, argumentando que tienen personalidades limítrofes que se desarrollan temprano en la vida. [175] [176] Sin embargo, estas teorías psicológicas son controvertidas: Gelles sugiere que las teorías psicológicas son limitadas y señala que otros investigadores han descubierto que solo el 10% (o menos) encaja en este perfil psicológico. Sostiene que los factores sociales son importantes, mientras que los rasgos de personalidad, las enfermedades mentales o la psicopatía son factores menores. [177] [178] [179]

Una explicación psicológica evolutiva de la violencia doméstica es que representa los intentos masculinos de controlar la reproducción femenina y asegurar la exclusividad sexual. [180] La violencia relacionada con las relaciones extramatrimoniales se considera justificada en ciertas partes del mundo. Por ejemplo, una encuesta en Diyarbakir , Turquía , encontró que, cuando se preguntó cuál era el castigo apropiado para una mujer que había cometido adulterio, el 37% de los encuestados dijo que debería ser asesinada, mientras que el 21% dijo que le deberían cortar la nariz o las orejas. [181]

Un informe de 1997 sugirió que los maltratadores domésticos muestran conductas de retención de pareja más altas que el promedio, que son intentos de mantener la relación con la pareja. El informe había afirmado que los hombres, más que las mujeres, estaban utilizando "la exhibición de recursos, la sumisión y la degradación, y las amenazas intrasexuales para retener a sus parejas". [182]

Las teorías sociales analizan los factores externos del entorno del delincuente, como la estructura familiar, el estrés, el aprendizaje social, e incluyen teorías de elección racional . [183]

La teoría del aprendizaje social sugiere que las personas aprenden observando y modelando el comportamiento de los demás. Con refuerzo positivo , el comportamiento continúa. Si uno observa un comportamiento violento, es más probable que lo imite. Si no hay consecuencias negativas (por ejemplo, la víctima acepta la violencia, con sumisión), entonces es probable que el comportamiento continúe. [184] [185] [186]

La teoría de los recursos fue propuesta por William Goode en 1971. [187] Las mujeres que dependen más de su cónyuge para su bienestar económico (por ejemplo, amas de casa, mujeres con discapacidad, mujeres desempleadas) y son las principales cuidadoras de sus hijos, temen la mayor carga financiera que supone abandonar su matrimonio. La dependencia significa que tienen menos opciones y pocos recursos para ayudarlas a afrontar o cambiar el comportamiento de su cónyuge. [188]

Las parejas que comparten el poder de forma equitativa experimentan una menor incidencia de conflictos y, cuando surgen, es menos probable que recurran a la violencia. Si uno de los cónyuges desea controlar y tener poder en la relación, puede recurrir al abuso. [189] Esto puede incluir coerción y amenazas, intimidación, abuso emocional, abuso económico, aislamiento, tomar a la ligera la situación y culpar al cónyuge, utilizar a los niños (amenazar con quitárselos) y comportarse como "amo del castillo". [190] [191]

Otro informe ha señalado que los maltratadores domésticos pueden estar cegados por la ira y, por lo tanto, se ven a sí mismos como víctimas cuando se trata de maltratar a su pareja en el ámbito doméstico. Debido principalmente a las emociones negativas y a las dificultades en la comunicación entre los miembros de la pareja, los maltratadores creen que han sido agraviados y, por lo tanto, psicológicamente se hacen ver como víctimas. [192]

El estrés puede aumentar cuando una persona vive en una situación familiar, con mayores presiones. El estrés social, debido a finanzas inadecuadas u otros problemas similares en una familia, puede aumentar aún más las tensiones. [177] La violencia no siempre es causada por el estrés, pero puede ser una forma en que algunas personas responden al estrés. [193] [194] Las familias y parejas en situación de pobreza pueden tener más probabilidades de sufrir violencia doméstica, debido al aumento del estrés y los conflictos sobre las finanzas y otros aspectos. [195] Algunos especulan que la pobreza puede obstaculizar la capacidad de un hombre para vivir a la altura de su idea de masculinidad exitosa, por lo que teme perder el honor y el respeto. Una teoría sugiere que cuando no puede apoyar económicamente a su esposa y mantener el control, puede recurrir a la misoginia , el abuso de sustancias y el crimen como formas de expresar la masculinidad. [195]

Las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo pueden experimentar factores de estrés social similares. Además, la violencia en las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo se ha vinculado a la homofobia internalizada, que contribuyó a la baja autoestima y la ira tanto en el perpetrador como en la víctima. [196] La homofobia internalizada también parece ser una barrera para que las víctimas busquen ayuda. De manera similar, el heterosexismo puede desempeñar un papel clave en la violencia doméstica en la comunidad LGBT. Como ideología social que implica que "la heterosexualidad es normativa, moralmente superior y mejor que [la homosexualidad]", [196] el heterosexismo puede obstaculizar los servicios y conducir a una autoimagen poco saludable en las minorías sexuales. El heterosexismo en las instituciones legales y médicas se puede ver en casos de discriminación, prejuicios e insensibilidad hacia la orientación sexual. Por ejemplo, a partir de 2006, siete estados negaron explícitamente a las personas LGBT la capacidad de solicitar órdenes de protección, [196] proliferando las ideas de subyugación LGBT, que está vinculada a sentimientos de ira e impotencia.

El poder y el control en las relaciones abusivas es la forma en que los abusadores ejercen abuso físico, sexual y de otro tipo para ganar control dentro de las relaciones. [197]

Una visión causalista de la violencia doméstica es que se trata de una estrategia para ganar o mantener poder y control sobre la víctima. Esta visión coincide con la teoría de costo-beneficio de Bancroft, que sostiene que el abuso recompensa al perpetrador de otras maneras que no sean, o además de, el simple ejercicio de poder sobre su(s) víctima(s). Cita evidencia en apoyo de su argumento de que, en la mayoría de los casos, los abusadores son perfectamente capaces de ejercer control sobre sí mismos, pero eligen no hacerlo por diversas razones. [198]

En ocasiones, una persona busca tener el poder y el control absolutos sobre su pareja y utiliza diferentes medios para lograrlo, incluida la violencia física. El agresor intenta controlar todos los aspectos de la vida de la víctima, como sus decisiones sociales, personales, profesionales y financieras. [64]

Las cuestiones de poder y control son parte integral del Proyecto de Intervención contra el Abuso Doméstico de Duluth , ampliamente utilizado . Desarrollaron la Rueda de Poder y Control para ilustrarlo: tiene el poder y el control en el centro, rodeados de rayos que representan las técnicas utilizadas. Los títulos de los rayos incluyen coerción y amenazas , intimidación, abuso emocional, aislamiento , minimización , negación y culpabilización, uso de niños, abuso económico y privilegio. [199]

Los críticos de este modelo sostienen que ignora las investigaciones que vinculan la violencia doméstica con el abuso de sustancias y los problemas psicológicos. [200] Algunas investigaciones modernas sobre los patrones de violencia doméstica han descubierto que las mujeres tienen más probabilidades de ser físicamente abusivas con su pareja en relaciones en las que sólo uno de los miembros de la pareja es violento, [201] [202] lo que pone en tela de juicio la eficacia de utilizar conceptos como el privilegio masculino para tratar la violencia doméstica. Algunas investigaciones modernas sobre los predictores de lesiones por violencia doméstica sugieren que el predictor más fuerte de lesiones por violencia doméstica es la participación en la violencia doméstica recíproca. [201]

La teoría de la no subordinación, a veces llamada teoría de la dominación, es un área de la teoría jurídica feminista que se centra en la diferencia de poder entre hombres y mujeres. [203] La teoría de la no subordinación adopta la posición de que la sociedad, y particularmente los hombres en la sociedad, utilizan las diferencias sexuales entre hombres y mujeres para perpetuar este desequilibrio de poder. [203] A diferencia de otros temas dentro de la teoría jurídica feminista, la teoría de la no subordinación se centra específicamente en ciertos comportamientos sexuales, incluido el control de la sexualidad de las mujeres , el acoso sexual , la pornografía y la violencia contra las mujeres en general. [204] Catharine MacKinnon sostiene que la teoría de la no subordinación aborda mejor estos problemas particulares porque afectan casi exclusivamente a las mujeres. [205] MacKinnon aboga por la teoría de la no subordinación sobre otras teorías, como la igualdad formal, la igualdad sustantiva y la teoría de la diferencia, porque la violencia sexual y otras formas de violencia contra las mujeres no son una cuestión de "igualdad y diferencia", sino que se ven mejor como desigualdades más centrales para las mujeres. [205] Aunque la teoría de la no subordinación se ha analizado extensamente al evaluar diversas formas de violencia sexual contra las mujeres, también sirve como base para comprender la violencia doméstica y por qué ocurre. La teoría de la no subordinación aborda la cuestión de la violencia doméstica como un subconjunto del problema más amplio de la violencia contra las mujeres porque las víctimas son abrumadoramente mujeres. [206]

Los defensores de la teoría de la no subordinación proponen varias razones por las que funciona mejor para explicar la violencia doméstica. En primer lugar, hay ciertos patrones recurrentes en la violencia doméstica que indican que no es el resultado de una ira intensa o discusiones, sino más bien es una forma de subordinación. [207] Esto se evidencia en parte por el hecho de que las víctimas de violencia doméstica suelen ser maltratadas en una variedad de situaciones y por una variedad de medios. [207] Por ejemplo, a veces las víctimas son golpeadas después de haber estado durmiendo o de haber sido separadas del agresor, y a menudo el maltrato adquiere una forma financiera o emocional además del maltrato físico. [207] Los partidarios de la teoría de la no subordinación utilizan estos ejemplos para disipar la noción de que el maltrato es siempre el resultado del calor del momento en que se produce la ira o discusiones intensas. [207] Además, los maltratadores a menudo emplean tácticas manipuladoras y deliberadas cuando abusan de sus víctimas, que pueden "variar desde buscar y destruir un objeto preciado de ella hasta golpearla en áreas de su cuerpo que no muestran moretones (por ejemplo, el cuero cabelludo) o en áreas donde se sentiría avergonzada de mostrar a otros sus moretones". [207] Estas conductas pueden ser incluso más útiles para un maltratador cuando el maltratador y la víctima comparten hijos, porque el maltratador a menudo controla los activos financieros de la familia, lo que hace que sea menos probable que la víctima se vaya si eso pondría a sus hijos en riesgo. [208]

La profesora Martha Mahoney, de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Miami , también señala la agresión durante la separación (un fenómeno en el que el agresor vuelve a agredir a la víctima que está intentando o ha intentado abandonar una relación abusiva) como prueba adicional de que la violencia doméstica se utiliza para subordinar a las víctimas a sus agresores. [209] La falta de voluntad del agresor para permitir que la víctima abandone la relación corrobora la idea de que se está utilizando la violencia para obligar a la víctima a seguir cumpliendo los deseos del agresor de que le obedezca. [209] Los teóricos de la no subordinación argumentan que todas estas acciones (la variedad de comportamientos y entornos abusivos, la explotación de los hijos de la víctima y la agresión tras la separación) sugieren un problema mayor que la mera incapacidad de gestionar adecuadamente la ira, aunque la ira puede ser un subproducto de estos comportamientos. [207] El propósito de estas acciones es mantener a la víctima, y a veces a toda la familia, subordinada al agresor, según la teoría de la no subordinación. [209]

Una segunda razón para utilizar la teoría de la no subordinación para explicar la violencia doméstica es que la frecuencia con la que ocurre supera la idea de que es meramente el resultado de la ira del agresor. El profesor Mahoney explica que debido al sensacionalismo generado en la cobertura mediática de casos de violencia doméstica particularmente horribles, es difícil para las personas conceptualizar con qué frecuencia ocurre la violencia doméstica en la sociedad. [209] Sin embargo, la violencia doméstica es un suceso habitual que experimenta hasta la mitad de las personas en los EE. UU., y una abrumadora cantidad de víctimas son mujeres. [209] La gran cantidad de víctimas de violencia doméstica en los EE. UU. sugiere que no es meramente el resultado de parejas íntimas que no pueden controlar su ira. [209] La teoría de la no subordinación sostiene que es el deseo del agresor de subordinar a la víctima, no su ira incontable, lo que explica la frecuencia de la violencia doméstica. [209] Los teóricos de la no subordinación argumentan que otras formas de teoría legal feminista no ofrecen ninguna explicación para el fenómeno de la violencia doméstica en general o la frecuencia con la que ocurre. [210]

Los críticos de la teoría de la no subordinación se quejan de que no ofrece soluciones a los problemas que señala. Por ejemplo, los defensores de la teoría de la no subordinación critican ciertos enfoques que se han adoptado para abordar la violencia doméstica en el sistema legal, como las políticas de arresto o procesamiento obligatorios. [211] Estas políticas quitan discreción a la aplicación de la ley al obligar a los agentes de policía a detener a los presuntos infractores de violencia doméstica y a los fiscales a procesar esos casos. [211] Hay mucho discurso en torno al arresto obligatorio. Los opositores argumentan que socava la autonomía de la víctima, desalienta el empoderamiento de las mujeres al descontar otros recursos disponibles y pone a las víctimas en mayor riesgo de abuso doméstico. Los estados que han implementado leyes de arresto obligatorio tienen tasas de homicidio 60% más altas, lo que se ha demostrado que es coherente con la disminución de las tasas de denuncia. [212] Los defensores de estas políticas sostienen que el sistema de justicia penal es a veces la única manera de llegar a las víctimas de violencia doméstica, y que si un infractor sabe que será arrestado, disuadirá la conducta de violencia doméstica futura. [211] Las personas que apoyan la teoría de la no subordinación argumentan que estas políticas sólo sirven para subordinar aún más a las mujeres al obligarlas a tomar un determinado curso de acción, agravando así el trauma que experimentaron durante el abuso. [211] Sin embargo, la teoría de la no subordinación en sí misma no ofrece soluciones mejores o más apropiadas, por lo que algunos académicos sostienen que otras formas de teoría jurídica feminista son más apropiadas para abordar cuestiones de violencia doméstica y sexual. [213]

La violencia doméstica suele coexistir con el abuso de alcohol. Dos tercios de las víctimas de abuso doméstico han informado de que el consumo de alcohol es un factor. Los bebedores moderados participan con mayor frecuencia en la violencia íntima que los bebedores moderados y los abstemios; sin embargo, por lo general son los bebedores empedernidos o los bebedores compulsivos los que participan en las formas más crónicas y graves de agresión. Las probabilidades, la frecuencia y la gravedad de los ataques físicos están correlacionadas positivamente con el consumo de alcohol. A su vez, la violencia disminuye después del tratamiento conductual del alcoholismo marital. [214]

Existen estudios que demuestran que existe un vínculo entre la violencia doméstica y la crueldad hacia los animales . Una gran encuesta nacional realizada por el Centro Noruego para Estudios sobre la Violencia y el Estrés Traumático encontró una "superposición sustancial entre el maltrato a los animales de compañía y el maltrato infantil" y que la crueldad hacia los animales "se daba con mayor frecuencia junto con el maltrato psicológico y formas menos graves de maltrato físico infantil", lo que "resuena con las conceptualizaciones del maltrato doméstico como un patrón continuo de maltrato psicológico y control coercitivo". [215]

.jpg/440px-Advertisement_for_Littleton_Butter_(31_December_1903).jpg)

La forma en que se considera la violencia doméstica varía de persona a persona y de cultura a cultura, pero en muchos lugares fuera de Occidente, el concepto es muy poco comprendido. En algunos países, incluso es ampliamente aceptado o completamente suprimido. Esto se debe a que en la mayoría de estos países la relación entre marido y mujer no se considera una relación de iguales, sino una en la que la mujer debe someterse al marido. Esto está codificado en las leyes de algunos países; por ejemplo, en Yemen , las normas sobre el matrimonio establecen que la mujer debe obedecer a su marido y no debe salir de casa sin su permiso. [216]

Según Violence against Women in Families and Relationships , "a nivel mundial, la mayoría de la población de varios países considera que golpear a la esposa está justificado en algunas circunstancias, más comúnmente en situaciones de infidelidad real o sospechada por parte de las esposas o de su 'desobediencia' hacia un esposo o pareja". [217] Estos actos violentos contra una esposa a menudo no son considerados una forma de abuso por la sociedad (tanto hombres como mujeres), sino que se considera que han sido provocados por el comportamiento de la esposa, a quien se considera culpable. En muchos lugares, los actos extremos como los crímenes de honor también son aprobados por un sector alto de la sociedad. En una encuesta, el 33,4% de los adolescentes de la capital de Jordania, Ammán , aprobaron los crímenes de honor. Esta encuesta se llevó a cabo en la capital de Jordania, que es mucho más liberal que otras partes del país; los investigadores dijeron que "esperaríamos que en las partes más rurales y tradicionales de Jordania, el apoyo a los crímenes de honor fuera incluso mayor". [218]

En un artículo de 2012, The Washington Post informó: "El grupo Reuters Trust Law nombró a la India uno de los peores países del mundo para las mujeres este año, en parte porque allí [la violencia doméstica] suele considerarse merecida. Un informe de 2012 de UNICEF concluyó que el 57 por ciento de los niños y el 53 por ciento de las niñas de entre 15 y 19 años de edad de la India piensan que golpear a la esposa está justificado". [219]

En las culturas conservadoras, una esposa que se viste con un atuendo considerado insuficientemente modesto puede sufrir violencia grave a manos de su marido o de sus familiares, y la mayoría de la sociedad considera que esas respuestas violentas son apropiadas: en una encuesta, el 62,8% de las mujeres en Afganistán dijeron que está justificado que un marido golpee a su esposa si ella viste ropa inapropiada. [220]

Según Antonia Parvanova , una de las dificultades de abordar legalmente la cuestión de la violencia doméstica es que en muchas sociedades dominadas por los hombres los hombres no comprenden que infligir violencia contra sus esposas es contra la ley. Dijo, refiriéndose a un caso ocurrido en Bulgaria: "Un marido fue juzgado por golpear brutalmente a su esposa y cuando el juez le preguntó si entendía lo que había hecho y si lo lamentaba, el marido dijo: 'Pero ella es mi esposa'. Ni siquiera entiende que no tiene derecho a golpearla". [222] El Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas escribe que: [223] "En algunos países en desarrollo, las prácticas que subyugan y dañan a las mujeres -como golpear a la esposa, matar en nombre del honor, mutilación genital femenina y muertes por dote- se toleran como parte del orden natural de las cosas".

Otra causa de impunidad jurídica son las fuertes opiniones de la población de ciertas sociedades de que la reconciliación es más apropiada que el castigo en los casos de violencia doméstica; un estudio encontró que el 64% de los funcionarios públicos en Colombia dijeron que si estuviera en sus manos resolver un caso de violencia de pareja, la acción que tomarían sería alentar a las partes a reconciliarse. [224]

La culpabilización de las víctimas también es una práctica habitual en muchas sociedades, incluso en los países occidentales: una encuesta del Eurobarómetro de 2010 reveló que el 52% de los encuestados estaba de acuerdo con la afirmación de que el "comportamiento provocador de las mujeres" era una causa de violencia contra las mujeres; los encuestados de Chipre, Dinamarca, Estonia, Finlandia, Letonia, Lituania, Malta y Eslovenia eran los que estaban más de acuerdo con esa afirmación (más del 70% en cada uno de estos países). [225] [226] [227]

Existe controversia sobre la influencia de la religión en la violencia doméstica. El judaísmo, el cristianismo y el islam han apoyado tradicionalmente los hogares dominados por los hombres y "la violencia contra la mujer, sancionada socialmente, ha persistido desde la antigüedad". [228]

Las opiniones sobre la influencia del Islam en la violencia doméstica difieren. Mientras que algunos autores [¿ quiénes? ] sostienen que el Islam está relacionado con la violencia contra las mujeres, especialmente en forma de crímenes de honor, [229] otros, como Tahira Shahid Khan, profesora especializada en cuestiones de la mujer en la Universidad Aga Khan de Pakistán, sostienen que es la dominación de los hombres y la condición inferior de las mujeres en la sociedad lo que conduce a estos actos, no la religión en sí. [230] [231] El discurso público (por ejemplo, a través de los medios de comunicación) y político que debate la relación entre el Islam, la inmigración y la violencia contra las mujeres es muy controvertido en muchos países occidentales. [232]

Entre los cristianos, los hombres y mujeres que asisten a la iglesia con mayor frecuencia tienen menos probabilidades de cometer violencia doméstica contra sus parejas. [233] El efecto de la asistencia a la iglesia no es causado por mayores niveles de apoyo social e integración comunitaria , que no están significativamente relacionados con la perpetración de violencia doméstica. Además, incluso cuando se tienen en cuenta las variaciones en los problemas psicológicos (a saber, los síntomas depresivos , la baja autoestima y el alcoholismo ), el efecto saludable de la asistencia a la iglesia permanece. [234] Las personas que son teológicamente conservadoras no tienen más probabilidades de cometer violencia doméstica, sin embargo, los hombres altamente conservadores tienen significativamente más probabilidades de cometer violencia doméstica cuando sus parejas son mucho más liberales que ellos. [235]

La enseñanza católica sobre el divorcio ha llevado a las mujeres a tener miedo de abandonar matrimonios abusivos. Sin embargo, los obispos católicos afirman específicamente que nadie está obligado a permanecer en un matrimonio abusivo. [236]

Las autoridades judías medievales no estaban de acuerdo con el tema de golpear a la esposa. La mayoría de los rabinos que vivían en tierras islámicas lo permitían como una herramienta de disciplina, mientras que los de la Francia y Alemania cristianas generalmente lo consideraban una justificación para el divorcio inmediato. [237]

Las costumbres y tradiciones locales son a menudo responsables de mantener ciertas formas de violencia doméstica. Entre esas costumbres y tradiciones figuran la preferencia por los hijos varones (el deseo de una familia de tener un niño y no una niña, muy extendido en algunas partes de Asia), que puede dar lugar a abusos y descuido de las niñas por parte de miembros de la familia decepcionados; los matrimonios infantiles y forzados; la dote; el sistema jerárquico de castas que estigmatiza a las castas inferiores y a los "intocables", lo que conduce a la discriminación y a la restricción de oportunidades de las mujeres, haciéndolas así más vulnerables a los abusos; los estrictos códigos de vestimenta para las mujeres que pueden ser impuestos mediante la violencia por miembros de la familia; el estricto requisito de la virginidad femenina antes del matrimonio y la violencia relacionada con las mujeres y niñas que no se ajustan a las normas; los tabúes sobre la menstruación que hacen que las mujeres sean aisladas y rechazadas durante el período de la menstruación; la mutilación genital femenina (MGF); las ideologías de los derechos conyugales a las relaciones sexuales que justifican la violación marital; y la importancia que se da al honor familiar. [238] [239] [240]

Un estudio de 2018 informó que en África subsahariana el 38% de las mujeres justificaban el abuso, en comparación con Europa, que tenía el 29%, y el sur de Asia, que tiene el número más alto con el 47% de las mujeres que justificaban el abuso. [241] Estas altas tasas podrían deberse al hecho de que en los países económicamente menos desarrollados, las mujeres están sujetas a las normas sociales y están sujetas a la tradición, por lo que tienen miedo de ir en contra de esa tradición, ya que recibirían una reacción violenta [242] mientras que en los países económicamente más desarrollados, las mujeres están más educadas y, por lo tanto, no se ajustarán a aquellas tradiciones que restringen sus derechos humanos básicos.

Según un informe de 2003 de Human Rights Watch, "costumbres como el pago de la 'doncella' (pago que hace un hombre a la familia de la mujer con la que desea casarse), mediante el cual un hombre esencialmente compra los favores sexuales y la capacidad reproductiva de su esposa, subrayan el derecho socialmente sancionado de los hombres a dictar los términos del sexo y a usar la fuerza para hacerlo". [243]

En los últimos años, se han logrado avances en el ámbito de la lucha contra las prácticas consuetudinarias que ponen en peligro a las mujeres, y en varios países se han promulgado leyes al respecto. El Comité Interafricano sobre Prácticas Tradicionales que Afectan a la Salud de las Mujeres y los Niños es una ONG que trabaja para cambiar los valores sociales, aumentar la conciencia y promulgar leyes contra las tradiciones nocivas que afectan a la salud de las mujeres y los niños en África. También se han promulgado leyes en algunos países; por ejemplo, el Código Penal de Etiopía de 2004 tiene un capítulo sobre prácticas tradicionales nocivas: Capítulo III: Delitos cometidos contra la vida, la persona y la salud mediante prácticas tradicionales nocivas . [244] Además, el Consejo de Europa adoptó el Convenio de Estambul, que exige a los Estados que lo ratifiquen que creen y apliquen plenamente leyes contra los actos de violencia previamente tolerados por la tradición, la cultura, la costumbre, en nombre del honor, o para corregir lo que se considere un comportamiento inaceptable. [245] La ONU creó el Manual sobre respuestas policiales eficaces a la violencia contra la mujer para proporcionar directrices para abordar y gestionar la violencia mediante la creación de leyes eficaces, políticas y prácticas de aplicación de la ley y actividades comunitarias para romper las normas sociales que toleran la violencia, la criminalizan y crean sistemas de apoyo eficaces para las supervivientes de la violencia. [246]

En culturas donde la policía y las autoridades judiciales tienen reputación de corruptas y de aplicar prácticas abusivas, las víctimas de violencia doméstica suelen ser reacias a recurrir a ayuda formal. [247]

La violencia contra las mujeres a veces es justificada por las propias mujeres; por ejemplo, en Malí, el 60% de las mujeres sin educación, poco más de la mitad de las mujeres con educación primaria y menos del 40% de las mujeres con educación secundaria o superior creen que los maridos tienen derecho a usar la violencia por razones correctivas. [248]

La aceptación de la violencia doméstica ha disminuido en algunos países, por ejemplo en Nigeria , donde el 62,4% de las mujeres apoyaban la violencia doméstica en 2003, el 45,7% en 2008 y el 37,1% en 2013. [249] Sin embargo, en algunos casos la aceptación aumentó, por ejemplo en Zimbabwe , donde el 53% de las mujeres justifican los golpes a las esposas. [250]

En Nigeria, la educación, el lugar de residencia, el índice de riqueza, la afiliación étnica, la afiliación religiosa, la autonomía de las mujeres en la toma de decisiones en el hogar y la frecuencia con la que se escucha la radio o se ve la televisión influyen significativamente en las opiniones de las mujeres sobre la violencia doméstica. [249] En opinión de los adolescentes de 15 a 19 años, el 14% de los niños en Kazajstán , pero el 9% de las niñas, creían que golpear a la esposa estaba justificado, y en Camboya, el 25% de los niños y el 42% de las niñas pensaban que estaba justificado. [251]

Un matrimonio forzado es un matrimonio en el que uno o ambos participantes se casan sin su consentimiento dado libremente. [252] En muchas partes del mundo, a menudo es difícil trazar una línea entre el matrimonio "forzado" y el "consensual": en muchas culturas (especialmente en el sur de Asia, Oriente Medio y partes de África ), los matrimonios se arreglan de antemano, a menudo tan pronto como nace una niña; la idea de que una niña vaya en contra de los deseos de su familia y elija ella misma a su futuro marido no es socialmente aceptada: no hay necesidad de usar amenazas o violencia para forzar el matrimonio, la futura novia se someterá porque simplemente no tiene otra opción. Como en el caso del matrimonio infantil, las costumbres de la dote y el precio de la novia contribuyen a este fenómeno. [253] Un matrimonio infantil es un matrimonio en el que una o ambas partes son menores de 18 años. [254]

Los matrimonios forzados e infantiles están asociados con una alta tasa de violencia doméstica. [13] [254] Este tipo de matrimonios están relacionados con la violencia tanto en lo que respecta a la violencia conyugal perpetrada dentro del matrimonio, como en lo que respecta a la violencia relacionada con las costumbres y tradiciones de estos matrimonios: violencia y tráfico relacionados con el pago de la dote y el precio de la novia, crímenes de honor por negarse al matrimonio. [255] [256] [257] [258]

El Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas afirma que, "A pesar de los compromisos casi universales de poner fin al matrimonio infantil, una de cada tres niñas en los países en desarrollo (excluyendo China) probablemente se casará antes de cumplir los 18 años. Una de cada nueve niñas se casará antes de cumplir los 15 años". [259] El Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas estima que, "más de 67 millones de mujeres de entre 20 y 24 años en 2010 se habían casado siendo niñas, la mitad de las cuales en Asia y una quinta parte en África". [259] El Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas dice que, "en la próxima década, 14,2 millones de niñas menores de 18 años se casarán cada año; esto se traduce en 39.000 niñas casadas cada día y esta cifra aumentará a un promedio de 15,1 millones de niñas al año, a partir de 2021 hasta 2030, si continúan las tendencias actuales". [259]

La falta de una legislación adecuada que penalice la violencia doméstica, o alternativamente una legislación que prohíba las conductas consentidas, puede obstaculizar el progreso en lo que respecta a la reducción de la incidencia de la violencia doméstica. El Secretario General de Amnistía Internacional ha declarado que: "Es increíble que en el siglo XXI algunos países estén tolerando el matrimonio infantil y la violación marital mientras otros están proscribiendo el aborto, las relaciones sexuales fuera del matrimonio y la actividad sexual entre personas del mismo sexo, incluso punibles con la muerte". [260] Según la OMS, "una de las formas más comunes de violencia contra la mujer es la ejercida por un marido o una pareja masculina". La OMS señala que esa violencia a menudo se ignora porque a menudo "los sistemas jurídicos y las normas culturales no la tratan como un delito, sino más bien como un asunto familiar 'privado' o una parte normal de la vida". [52] La penalización del adulterio se ha citado como una incitación a la violencia contra la mujer, ya que estas prohibiciones a menudo tienen por objeto, en la ley o en la práctica, controlar el comportamiento de las mujeres y no el de los hombres; y se utilizan para racionalizar los actos de violencia contra la mujer. [261] [262]

Muchos países consideran legal la violencia doméstica o no han adoptado medidas destinadas a penalizar su ocurrencia, [263] [264] especialmente en países de mayoría musulmana, y entre esos países, algunos consideran la disciplina de las esposas como un derecho del marido, por ejemplo en Iraq. [265]

Según la Alta Comisionada para los Derechos Humanos , Navi Pillay : [53]

Algunos han sostenido, y siguen sosteniendo, que la violencia familiar queda fuera del marco conceptual de los derechos humanos internacionales. Sin embargo, en virtud de las leyes y normas internacionales, existe una clara responsabilidad del Estado de defender los derechos de las mujeres y garantizar la no discriminación, lo que incluye la responsabilidad de prevenir, proteger y proporcionar reparación, independientemente del sexo y de la situación de la persona en la familia.

La forma en que se equilibran los derechos individuales de un miembro de la familia frente a los derechos de la familia como unidad varía significativamente en diferentes sociedades. Esto puede influir en el grado en que un gobierno puede estar dispuesto a investigar incidentes familiares. [266] En algunas culturas, se espera que los miembros individuales de la familia sacrifiquen casi por completo sus propios intereses en favor de los intereses de la familia en su conjunto. Lo que se considera una expresión indebida de autonomía personal se condena como inaceptable. En estas culturas, la familia predomina sobre el individuo y, cuando esto interactúa con culturas del honor, la elección individualista que puede dañar la reputación de la familia en la comunidad puede dar lugar a castigos extremos, como los crímenes de honor. [267]

En Australia, la violencia doméstica se refiere a los casos de violencia en entornos domésticos entre personas que mantienen relaciones íntimas. [268] El término puede ser modificado por la legislación de cada estado y puede ampliar el espectro de la violencia doméstica, como en Victoria, donde las relaciones familiares y presenciar cualquier tipo de violencia en la familia se define como un incidente de violencia familiar . [269] En los países nórdicos, el término violencia en relaciones cercanas se utiliza en contextos legales y de políticas. [270]

La violencia doméstica ocurre en las comunidades inmigrantes y, a menudo, en estas comunidades hay poco conocimiento de las leyes y políticas del país de acogida. Un estudio realizado entre asiáticos del sur de primera generación en el Reino Unido concluyó que tenían poco conocimiento sobre lo que constituye una conducta delictiva según la ley inglesa. Los investigadores descubrieron que "ciertamente no había conciencia de que pudiera haber violación dentro de un matrimonio". [271] [272] Un estudio realizado en Australia demostró que entre las mujeres inmigrantes de la muestra que habían sido maltratadas por sus parejas y no lo denunciaron, el 16,7% no sabía que la violencia doméstica era ilegal, mientras que el 18,8% no sabía que podían obtener protección. [273]

La capacidad de las víctimas de violencia doméstica para abandonar la relación es fundamental para prevenir nuevos abusos. En las comunidades tradicionales, las mujeres divorciadas suelen sentirse rechazadas y excluidas. Para evitar este estigma, muchas mujeres prefieren permanecer en el matrimonio y soportar los abusos. [274]

Las leyes discriminatorias sobre el matrimonio y el divorcio también pueden desempeñar un papel en la proliferación de la práctica. [275] [276] Según Rashida Manjoo , relatora especial de las Naciones Unidas sobre la violencia contra la mujer:

En muchos países, el acceso de la mujer a la propiedad depende de su relación con el hombre. Cuando se separa de su marido o cuando éste muere, corre el riesgo de perder su casa, sus tierras, sus enseres domésticos y otros bienes. La falta de garantía de igualdad de derechos de propiedad en caso de separación o divorcio desalienta a las mujeres a abandonar matrimonios violentos, ya que pueden verse obligadas a elegir entre la violencia en el hogar y la indigencia en la calle. [277]

La imposibilidad legal de obtener el divorcio también es un factor en la proliferación de la violencia doméstica. [278] En algunas culturas donde los matrimonios son arreglados entre familias, una mujer que intenta una separación o divorcio sin el consentimiento de su marido y su familia extendida o parientes puede correr el riesgo de ser sometida a violencia basada en el honor. [279] [267]

La costumbre del precio de la novia también hace más difícil abandonar un matrimonio: si una esposa quiere irse, el marido puede exigirle a su familia que le devuelva el precio de la novia. [280] [281] [282]

En países avanzados [ aclaración necesaria ] como el Reino Unido, las víctimas de violencia doméstica pueden tener dificultades para conseguir una vivienda alternativa, lo que puede obligarlas a permanecer en la relación abusiva. [283]

Muchas víctimas de violencia doméstica demoran la decisión de abandonar al abusador porque tienen mascotas y temen lo que les pueda pasar si se van. Los refugios deben aceptar más mascotas, y muchos se niegan a hacerlo. [284]

En algunos países, la política de inmigración está vinculada a si la persona que desea obtener la ciudadanía está casada o no con su patrocinador. Esto puede hacer que las personas queden atrapadas en relaciones violentas: pueden correr el riesgo de ser deportadas si intentan separarse (pueden ser acusadas de haber contraído un matrimonio ficticio ). [285] [286] [287] [288] A menudo, las mujeres provienen de culturas en las que sufrirán la deshonra de sus familias si abandonan su matrimonio y regresan a casa, por lo que prefieren permanecer casadas, quedando atrapadas en un ciclo de abuso. [289]

Algunos estudios han encontrado cierta asociación entre la pandemia de COVID-19 y un aumento en la tasa de violencia doméstica. [290] Los mecanismos de afrontamiento adoptados por las personas durante el estado de aislamiento se han visto implicados en el aumento en todo el mundo. [291] Algunas de las implicaciones de este período de restricción son la angustia financiera, el estrés inducido, la frustración y la consiguiente búsqueda de mecanismos de afrontamiento, que podrían desencadenar la violencia. [292]

En las principales ciudades de Nigeria, como Lagos y Abuja, en la India y en la provincia de Hubei en China, se registró un aumento del nivel de violencia de pareja. [293] [294]

En muchos países, incluidos Estados Unidos, China y muchos países europeos, se ha registrado un aumento de la prevalencia de la violencia doméstica durante las restricciones. En la India, se registró un aumento del 131 % de la violencia doméstica en las zonas que aplicaron medidas de confinamiento estrictas. [295] [296]

Moretones, huesos rotos, heridas en la cabeza, laceraciones y hemorragias internas son algunos de los efectos agudos de un incidente de violencia doméstica que requieren atención médica y hospitalización. [297] Algunas condiciones de salud crónicas que se han vinculado a las víctimas de violencia doméstica son artritis , síndrome del intestino irritable , dolor crónico , dolor pélvico , úlceras y migrañas. [298] Las víctimas que están embarazadas durante una relación de violencia doméstica experimentan un mayor riesgo de aborto espontáneo, parto prematuro y lesiones o muerte del feto. [297]

Una nueva investigación muestra que existen fuertes vínculos entre la exposición a la violencia doméstica y el abuso en todas sus formas y mayores tasas de muchas enfermedades crónicas. [299] La evidencia más sólida proviene del Estudio de Experiencias Adversas en la Infancia, que muestra correlaciones entre la exposición al abuso o negligencia y mayores tasas en la edad adulta de enfermedades crónicas, conductas de alto riesgo para la salud y una menor expectativa de vida. [300] La evidencia de la asociación entre la salud física y la violencia contra la mujer se ha ido acumulando desde principios de los años 1990. [301]

La OMS ha señalado que las mujeres que viven en relaciones abusivas tienen un riesgo significativamente mayor de contraer el VIH/SIDA. La OMS señala que las mujeres que viven en relaciones violentas tienen dificultades para negociar relaciones sexuales más seguras con sus parejas, a menudo se ven obligadas a mantener relaciones sexuales y les resulta difícil solicitar pruebas adecuadas cuando creen que pueden estar infectadas con el VIH. [303] Una década de investigación transversal en Ruanda, Tanzania, Sudáfrica y la India ha demostrado sistemáticamente que las mujeres que han sufrido violencia de pareja tienen más probabilidades de estar infectadas con el VIH. [304] La OMS afirmó que: [303]

Existen razones de peso para poner fin a la violencia de pareja, tanto en sí misma como para reducir la vulnerabilidad de las mujeres y las niñas al VIH/SIDA. Las pruebas sobre los vínculos entre la violencia contra la mujer y el VIH/SIDA ponen de relieve que existen mecanismos directos e indirectos mediante los cuales ambos interactúan.

Las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo se ven afectadas de manera similar por el estado serológico respecto del VIH/SIDA en casos de violencia doméstica. La investigación de Heintz y Melendez concluyó que las personas del mismo sexo pueden tener dificultades para abordar el tema del sexo seguro por razones como "una menor percepción de control sobre el sexo, miedo a la violencia y una distribución desigual del poder..." [305]. De quienes informaron sobre violencia en el estudio, aproximadamente el 50% informó haber tenido experiencias sexuales forzadas, de las cuales solo la mitad informó haber utilizado medidas de sexo seguro. Las barreras para el sexo seguro incluían el miedo al abuso y el engaño en las prácticas sexuales seguras. La investigación de Heintz y Melendez concluyó finalmente que la agresión/abuso sexual en las relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo es una preocupación importante en cuanto a la infección por VIH/SIDA, ya que disminuye los casos de sexo seguro. Además, estos incidentes generan más miedo y estigma en torno a las conversaciones sobre sexo seguro y a conocer el estado serológico respecto de una ETS. [305]

Entre las víctimas que aún viven con sus agresores se reportan comúnmente altos niveles de estrés, miedo y ansiedad. La depresión también es común, ya que se hace que las víctimas se sientan culpables por "provocar" el abuso y con frecuencia son sometidas a críticas intensas . Se informa que el 60% de las víctimas cumplen los criterios de diagnóstico de depresión , ya sea durante o después de la terminación de la relación, y tienen un riesgo mucho mayor de suicidio. Aquellos que son maltratados emocional o físicamente a menudo también están deprimidos debido a un sentimiento de inutilidad. Estos sentimientos a menudo persisten a largo plazo y se sugiere que muchos reciban terapia para ello debido al mayor riesgo de suicidio y otros síntomas traumáticos. [306]