El Go es un juego de mesa de estrategia abstracta para dos jugadores en el que el objetivo es cercar más territorio que el oponente. El juego fue inventado en China hace más de 2500 años y se cree que es el juego de mesa más antiguo que se juega de forma continua hasta el día de hoy. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Una encuesta de 2016 realizada por los 75 países miembros de la Federación Internacional de Go descubrió que hay más de 46 millones de personas en todo el mundo que saben jugar al Go y más de 20 millones de jugadores actuales, la mayoría de los cuales viven en el este de Asia . [6]

Las piezas del juego se llaman piedras . Un jugador usa las piedras blancas y el otro las negras. Los jugadores se turnan para colocar sus piedras en las intersecciones vacías ( puntos ) del tablero. Una vez colocadas, las piedras no se pueden mover, pero las piedras capturadas se retiran inmediatamente del tablero. Una sola piedra (o grupo conectado de piedras) es capturada cuando está rodeada por las piedras del oponente en todos los puntos adyacentes ortogonalmente . [7] El juego continúa hasta que ningún jugador desee hacer otro movimiento.

Cuando un juego concluye, el ganador se determina contando el territorio rodeado de cada jugador junto con las piedras capturadas y los komi (puntos agregados a la puntuación del jugador con las piedras blancas como compensación por jugar en segundo lugar). [8] Los juegos también pueden terminar por rendición. [9]

El tablero estándar de Go tiene una cuadrícula de 19×19 líneas, que contiene 361 puntos. Los principiantes suelen jugar en tableros más pequeños de 9×9 y 13×13 [10] , y la evidencia arqueológica muestra que el juego se jugaba en siglos anteriores en un tablero con una cuadrícula de 17×17. Sin embargo, los tableros con una cuadrícula de 19×19 se habían convertido en estándar cuando el juego llegó a Corea en el siglo V d. C. y a Japón en el siglo VII d. C. [11]

El Go se consideraba una de las cuatro artes esenciales de los eruditos aristocráticos chinos cultos de la antigüedad. La primera referencia escrita al juego se reconoce generalmente como el anal histórico Zuo Zhuan [12] [13] ( c. siglo IV a. C.). [14]

A pesar de sus reglas relativamente simples, el Go es extremadamente complejo. En comparación con el ajedrez , el Go tiene un tablero más grande con más posibilidades de juego y partidas más largas y, en promedio, muchas más alternativas a considerar por movimiento. Se ha calculado que el número de posiciones legales en el tablero en Go es aproximadamente2,1 × 10 170 , [15] [a] que es mucho mayor que el número de átomos en el universo observable , que se estima en el orden de 10 80 . [17]

El nombre Go es una forma corta de la palabra japonesa igo (囲碁;いご), que deriva del anterior wigo (ゐご), a su vez del chino medio ɦʉi gi (圍棋, mandarín : wéiqí , lit. ' juego de mesa de cerco ' o ' juego de mesa de rodear ' ). En inglés, el nombre Go cuando se usa para el juego a menudo se escribe con mayúscula para diferenciarlo de la palabra común go . [18] En los eventos patrocinados por la Fundación Ing Chang-ki , se escribe goe . [19]

El nombre coreano baduk (바둑) deriva de la palabra del coreano medio Badok , cuyo origen es controvertido; las etimologías más plausibles incluyen el sufijo dok añadido a Ba para significar 'tablero plano y ancho', o la unión de Bat , que significa 'campo', y Dok , que significa 'piedra'. Etimologías menos plausibles incluyen una derivación de Badukdok , que hace referencia a las piezas del juego, o una derivación del chino páizi (排子), que significa 'organizar piezas'. [20]

El Go es un juego de enfrentamiento entre dos jugadores cuyo objetivo es capturar territorio, es decir, ocupar y rodear con sus propias piedras un área total vacía del tablero mayor que la del oponente. [21] A medida que avanza el juego, los jugadores colocan piedras en el tablero creando "formaciones" de piedras y cerrando espacios. Las piedras nunca se mueven en el tablero, pero cuando son "capturadas" se retiran del tablero. Las piedras se unen entre sí para formar una formación al estar adyacentes a lo largo de las líneas negras, no en diagonales (de las cuales no hay ninguna). Las disputas entre formaciones opuestas suelen ser extremadamente complejas y pueden dar como resultado la expansión, reducción o captura total y pérdida de formaciones y sus espacios vacíos cerrados (llamados "ojos"). Otro componente esencial del juego es el control del sente (es decir, controlar la ofensiva, de modo que el oponente se vea obligado a realizar movimientos defensivos); esto suele cambiar varias veces durante el juego.

Inicialmente, el tablero está vacío y los jugadores se turnan para colocar una piedra por turno. A medida que avanza el juego, los jugadores intentan unir sus piedras para formar formaciones "vivas" (es decir, que estén permanentemente a salvo de ser capturadas), así como amenazar con capturar las piedras y formaciones de su oponente. Las piedras tienen características tanto ofensivas como defensivas, según la situación.

Un concepto esencial es que una formación de piedras debe tener, o ser capaz de formar, al menos dos puntos abiertos cerrados conocidos como ojos para preservarse de ser capturada. Una formación que tenga al menos dos ojos no puede ser capturada, incluso después de que el oponente la rodee por fuera, [23] porque cada ojo constituye una libertad que el oponente debe llenar como paso final en la captura. Una formación que tenga dos o más ojos se dice que está incondicionalmente viva, [24] por lo que puede evadir la captura indefinidamente, y un grupo que no puede formar dos ojos se dice que está muerto y puede ser capturado.

La estrategia general es colocar piedras para cercar el territorio, atacar a los grupos débiles del oponente (intentando matarlos para que sean eliminados) y siempre estar atento al estado de vida de los propios grupos. [25] [26] Las libertades de los grupos son contables. Las situaciones en las que grupos mutuamente opuestos deben capturarse entre sí o morir se denominan razas de captura, o semeai . [27] En una raza de captura, el grupo con más libertades podrá finalmente capturar las piedras del oponente. [27] [28] [b] La captura de razas y los elementos de vida o muerte son los principales desafíos del Go.

Al final del juego, los jugadores pueden pasar en lugar de colocar una piedra si creen que no hay más oportunidades de juego rentable. [29] El juego termina cuando ambos jugadores pasan [30] o cuando un jugador se rinde. En general, para puntuar el juego, cada jugador cuenta el número de puntos desocupados rodeados por sus piedras y luego resta el número de piedras que fueron capturadas por el oponente. El jugador con la puntuación mayor (después de ajustar el hándicap llamado komi) gana el juego.

En las etapas iniciales del juego, los jugadores suelen establecer grupos de piedras (o bases ) cerca de las esquinas y alrededor de los lados del tablero, generalmente comenzando en la tercera o cuarta línea desde el borde del tablero en lugar de en el borde mismo del tablero. Los bordes y las esquinas facilitan el desarrollo de grupos que tienen mejores opciones de vida (autoviabilidad para un grupo de piedras que evita la captura) y establecen formaciones para territorio potencial. [31] Los jugadores suelen comenzar cerca de las esquinas porque establecer territorio es más fácil con la ayuda de dos bordes del tablero. [32] Las secuencias de apertura de esquinas establecidas se denominan joseki y a menudo se estudian de forma independiente. [33] Sin embargo, en la mitad del juego, los grupos de piedras también deben alcanzar el área central grande del tablero para capturar más territorio.

Las damas son puntos que se encuentran entre los muros limítrofes de los blancos y los negros y, como tales, se consideran sin valor para ninguno de los dos bandos. Los seki son pares de grupos blancos y negros que están mutuamente vivos y en los que ninguno tiene dos ojos.

Ko (chino y japonés:劫) es una posición de captura de piedra que puede repetirse indefinidamente. Las reglas no permiten que se repita una posición del tablero. Por lo tanto, no se permitiría ningún movimiento que restableciera la posición anterior del tablero y el siguiente jugador se vería obligado a jugar en otro lugar. Si la jugada requiere una respuesta estratégica por parte del primer jugador, cambiando aún más el tablero, entonces el segundo jugador podría "retomar el ko", y el primer jugador estaría en la misma situación de necesitar cambiar el tablero antes de intentar recuperar el ko. Y así sucesivamente. [34] Algunas de estas peleas de ko pueden ser importantes y decidir la vida de un grupo grande, mientras que otras pueden valer solo uno o dos puntos. Algunas peleas de ko se conocen como kos de picnic cuando solo un bando tiene mucho que perder. [35] En japonés, se llama hanami ko. [36]

Jugar con otros jugadores requiere generalmente conocer la fuerza de cada uno, indicada por su rango (que va de 30 kyu a 1 kyu, luego de 1 dan a 7 dan, luego de 1 dan pro a 9 dan pro). Una diferencia de rango puede ser compensada por un hándicap: a las negras se les permite colocar dos o más piedras en el tablero para compensar la mayor fuerza de las blancas. [37] [38] Existen diferentes conjuntos de reglas (coreano, japonés, chino, AGA, etc.), que son casi completamente equivalentes, excepto por ciertas posiciones especiales y el método de puntuación al final.

Los aspectos estratégicos básicos incluyen los siguientes:

La estrategia utilizada puede llegar a ser muy abstracta y compleja. Los jugadores de alto nivel pasan años mejorando su comprensión de la estrategia, y un novato puede jugar cientos de partidas contra oponentes antes de poder ganar con regularidad.

La estrategia se ocupa de la influencia global, la interacción entre piedras distantes, la necesidad de tener en cuenta todo el tablero durante las luchas locales y otras cuestiones que afectan al juego en su conjunto. Por lo tanto, es posible permitir una pérdida táctica cuando confiere una ventaja estratégica.

Los novatos suelen empezar colocando piedras al azar en el tablero, como si fuera un juego de azar. Se desarrolla una comprensión de cómo se conectan las piedras para obtener mayor poder, y luego se pueden entender algunas secuencias de apertura comunes básicas. Aprender las formas de vida y muerte ayuda de manera fundamental a desarrollar la comprensión estratégica de los grupos débiles . [c] Se dice que un jugador que juega agresivamente y puede manejar la adversidad muestra kiai , o espíritu de lucha, en el juego.

En la apertura del juego, los jugadores suelen jugar y ganar territorio en las esquinas del tablero primero, ya que la presencia de dos bordes les hace más fácil rodear el territorio y establecer los ojos que necesitan. [39] Desde una posición segura en una esquina, es posible reclamar más territorio extendiéndose a lo largo del costado del tablero. [40] La apertura es la parte teóricamente más difícil del juego y requiere una gran proporción del tiempo de reflexión de los jugadores profesionales. [41] [42] La primera piedra jugada en una esquina del tablero generalmente se coloca en la tercera o cuarta línea desde el borde. Los jugadores tienden a jugar en o cerca del punto de 4–4 estrellas durante la apertura. Jugar más cerca del borde no produce suficiente territorio para ser eficiente, y jugar más lejos del borde no asegura de manera segura el territorio. [43]

En la apertura, los jugadores suelen jugar secuencias establecidas llamadas joseki , que son intercambios equilibrados a nivel local; [44] sin embargo, el joseki elegido también debe producir un resultado satisfactorio a escala global. Por lo general, es aconsejable mantener un equilibrio entre territorio e influencia. Cuál de estos obtiene prioridad es a menudo una cuestión de gusto individual.

La fase intermedia del juego es la más combativa y suele durar más de 100 movimientos. Durante la fase intermedia, los jugadores invaden los territorios de los demás y atacan a las formaciones que carecen de los dos ojos necesarios para ser viables. Estos grupos pueden ser salvados o sacrificados por algo más significativo en el tablero. [45] Es posible que un jugador logre capturar un grupo grande y débil del oponente, lo que a menudo resulta decisivo y termina la partida con una rendición. Sin embargo, las cosas pueden ser aún más complejas, con grandes concesiones, grupos aparentemente muertos que reviven y un juego hábil para atacar de tal manera que se construyan territorios en lugar de matar. [46]

El final del medio juego y la transición al final del juego se caracterizan por algunas características. Cerca del final de una partida, el juego se divide en combates localizados que no se afectan entre sí, [47] con la excepción de los combates de ko , en los que antes el área central del tablero se relacionaba con todas las partes del mismo. Ningún grupo grande y débil sigue en serio peligro. A los movimientos se les puede atribuir razonablemente un valor definido, como 20 puntos o menos, en lugar de ser simplemente necesarios para competir. Ambos jugadores establecen objetivos limitados en sus planes, en cuanto a crear o destruir territorio, capturar o salvar piedras. Estos aspectos cambiantes del juego suelen ocurrir prácticamente al mismo tiempo, para los jugadores fuertes. En resumen, el medio juego cambia al final del juego cuando los conceptos de estrategia e influencia necesitan una reevaluación en términos de resultados finales concretos en el tablero.

Aparte del orden de juego (movimientos alternos, las negras mueven primero o toman una ventaja) y las reglas de puntuación, esencialmente solo hay dos reglas en Go:

Casi toda la información sobre cómo se juega el juego es heurística, es decir, se trata de información aprendida sobre cómo funcionan los patrones de las piedras en el tablero, en lugar de una regla. Otras reglas son especializadas, ya que surgen de diferentes conjuntos de reglas, pero las dos reglas anteriores cubren casi la totalidad de cualquier juego jugado.

Aunque existen algunas diferencias menores entre los conjuntos de reglas utilizados en diferentes países, [48] más notablemente en las reglas de puntuación chinas y japonesas, [49] estas diferencias no afectan en gran medida las tácticas y la estrategia del juego.

Salvo que se indique lo contrario, las reglas básicas que se presentan aquí son válidas independientemente de las reglas de puntuación utilizadas. Las reglas de puntuación se explican por separado. Los términos de Go para los que no existe un equivalente en inglés se denominan comúnmente por sus nombres en japonés.

Los dos jugadores, Negro y Blanco, se turnan para colocar piedras de su color en las intersecciones del tablero, una piedra a la vez. El tamaño habitual del tablero es una cuadrícula de 19×19, pero para principiantes o para jugar partidas rápidas, [50] los tamaños de tablero más pequeños de 13×13 [51] y 9×9 también son populares. [52] El tablero está vacío para empezar. [53] Negro juega primero a menos que se le dé un hándicap de dos o más piedras, en cuyo caso juega primero Blanco. Los jugadores pueden elegir cualquier intersección desocupada para jugar excepto aquellas prohibidas por las reglas de ko y suicidio (ver más abajo). Una vez jugada, una piedra nunca puede ser movida y puede ser retirada del tablero solo si es capturada. [54] Un jugador puede pasar su turno, negándose a colocar una piedra, aunque esto generalmente solo se hace al final del juego cuando ambos jugadores creen que no se puede lograr nada más con más juego. Cuando ambos jugadores pasan consecutivamente, el juego termina [55] y luego se puntúa.

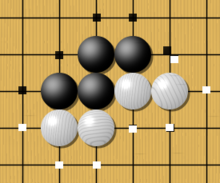

Las piedras del mismo color adyacentes vertical y horizontalmente forman una cadena (también llamada cadena o grupo ), [56] formando una unidad discreta que no se puede dividir. [57] Solo las piedras conectadas entre sí por las líneas del tablero crean una cadena; las piedras que están adyacentes en diagonal no están conectadas. Las cadenas se pueden expandir colocando piedras adicionales en intersecciones adyacentes, y se pueden conectar entre sí colocando una piedra en una intersección que esté adyacente a dos o más cadenas del mismo color. [58]

Un punto vacío adyacente a una piedra, a lo largo de una de las líneas de la cuadrícula del tablero, se denomina libertad para esa piedra. [59] [60] Las piedras en una cadena comparten sus libertades. [56] Una cadena de piedras debe tener al menos una libertad para permanecer en el tablero. Cuando una cadena está rodeada por piedras opuestas de modo que no tiene libertades, es capturada y removida del tablero. [61]

Un ejemplo de una situación en la que se aplica la regla ko

Los jugadores no pueden hacer un movimiento que devuelva el juego a la posición inmediatamente anterior. Esta regla, llamada regla ko , evita la repetición interminable (un punto muerto). [62] Como se muestra en el ejemplo ilustrado: las blancas tenían una piedra donde estaba el círculo rojo, y las negras la acaban de capturar jugando una piedra en 1 (por lo que la piedra blanca ha sido removida). Sin embargo, es evidente que ahora la piedra negra en 1 está inmediatamente amenazada por las tres piedras blancas circundantes. Si se le permitiera a las blancas jugar de nuevo en el círculo rojo, la situación volvería a la original, pero la regla ko prohíbe ese tipo de repetición interminable. Por lo tanto, las blancas se ven obligadas a moverse a otro lugar, o pasar. Si las blancas quieren recuperar la piedra negra en 1 , las blancas deben atacar a las negras en otro lugar del tablero con tanta fuerza que las negras se muevan a otro lugar para contrarrestarlo, lo que le da a las blancas esa oportunidad. Si el movimiento forzado de las blancas tiene éxito, se denomina "ganar el sente "; Si las negras responden en otra parte del tablero, las blancas pueden retomar la piedra de las negras en 1 y el ko continúa, pero esta vez las negras deben moverse a otra parte. Una repetición de tales intercambios se denomina pelea de ko . [63] Para detener la posibilidad de peleas de ko , se necesitarían agregar dos piedras del mismo color al grupo, formando un grupo de 5 piedras negras o 5 piedras blancas.

Si bien los distintos conjuntos de reglas coinciden en la regla ko que prohíbe devolver el tablero a una posición inmediatamente anterior, abordan de distintas maneras la situación relativamente poco común en la que un jugador podría recrear una posición anterior que se encuentra más alejada. Consulte Reglas de Go § Repetición para obtener más información.

Un jugador no puede colocar una piedra de manera que él o su grupo no tengan inmediatamente ninguna libertad, a menos que al hacerlo se prive inmediatamente a un grupo enemigo de su libertad final. En el segundo caso, el grupo enemigo es capturado, dejando a la nueva piedra con al menos una libertad, por lo que la nueva piedra puede ser colocada. [66] Esta regla es responsable de la importantísima diferencia entre uno y dos ojos: si un grupo con un solo ojo está completamente rodeado por fuera, puede ser eliminado con una piedra colocada en su único ojo. (Un ojo es un punto vacío o un grupo de puntos rodeados por un grupo de piedras).

Las reglas de Inglaterra y Nueva Zelanda no tienen esta regla [67] , y en ese caso un jugador podría destruir uno de sus propios grupos (suicidarse). Esta jugada solo sería útil en conjuntos limitados de situaciones que involucraran un espacio interior pequeño o planificación [68] . En el ejemplo de la derecha, puede ser útil como amenaza de ko.

Como las negras tienen la ventaja de jugar el primer movimiento, la idea de otorgarle a las blancas alguna compensación surgió durante el siglo XX. Esto se llama komi , que le da a las blancas una compensación de 5,5 puntos bajo las reglas japonesas, 6,5 puntos bajo las reglas coreanas y 15/4 piedras, o 7,5 puntos bajo las reglas chinas (la cantidad de puntos varía según el conjunto de reglas). [69] En el juego con hándicap, las blancas reciben solo un komi de 0,5 puntos, para romper un posible empate ( jigo ).

Se utilizan dos tipos generales de procedimientos de puntuación y los jugadores deciden cuál utilizar antes de jugar. Ambos procedimientos casi siempre dan el mismo ganador.

Ambos procedimientos se cuentan después de que ambos jugadores hayan pasado consecutivamente, las piedras que todavía están en el tablero pero que no pueden evitar ser capturadas, llamadas piedras muertas , se eliminan. Dado que la cantidad de piedras que un jugador tiene en el tablero está directamente relacionada con la cantidad de prisioneros que ha tomado su oponente, la puntuación neta resultante, es decir, la diferencia entre las puntuaciones de las negras y las blancas es idéntica bajo ambos conjuntos de reglas (a menos que los jugadores hayan pasado diferentes cantidades de veces durante el transcurso de la partida). Por lo tanto, el resultado neto dado por los dos sistemas de puntuación rara vez difiere en más de un punto. [71]

Si bien no se menciona en las reglas del Go (al menos en conjuntos de reglas más simples, como los de Nueva Zelanda y los EE. UU.), el concepto de un grupo vivo de piedras es necesario para una comprensión práctica del juego. [72]

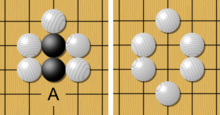

Ejemplos de ojos (marcados). Los grupos negros en la parte superior del tablero están vivos, ya que tienen al menos dos ojos. Los grupos negros en la parte inferior están muertos, ya que solo tienen un ojo. El punto marcado con a es un ojo falso, por lo que el grupo negro con el ojo falso a puede ser eliminado por el grupo blanco en dos turnos.

Cuando un grupo de piedras está casi rodeado y no tiene opciones para conectarse con piedras amigas en otros lugares, el estado del grupo es vivo, muerto o inestable . Se dice que un grupo de piedras está vivo si no puede ser capturado, incluso si se permite al oponente moverse primero. Por el contrario, se dice que un grupo de piedras está muerto si no puede evitar ser capturado, incluso si se permite al propietario del grupo el primer movimiento. De lo contrario, se dice que el grupo está inestable: el jugador defensor puede hacerlo vivo o el oponente puede matarlo , dependiendo de quién juegue primero. [72]

Un ojo es un punto vacío o un grupo de puntos rodeados por un grupo de piedras. Si el ojo está rodeado por piedras negras, las blancas no pueden jugar allí a menos que tal jugada suponga tomar la última libertad de las negras y capturar las piedras negras. (Según la regla del suicidio en la mayoría de los conjuntos de reglas, tal movimiento está prohibido, pero incluso si no estuviera prohibido, sería un suicidio inútil de una piedra blanca).

Si un grupo de las negras tiene dos ojos, las blancas nunca pueden capturarlo porque no pueden quitar ambas libertades simultáneamente. Si las negras tienen un solo ojo, las blancas pueden capturar el grupo de las negras jugando en el ojo único, quitando la última libertad de las negras. Tal movimiento no es un suicidio porque las piedras negras se quitan primero. En el diagrama de "Ejemplos de ojos", todos los puntos rodeados con un círculo son ojos. Los dos grupos negros en las esquinas superiores están vivos, ya que ambos tienen al menos dos ojos. Los grupos en las esquinas inferiores están muertos, ya que ambos tienen un solo ojo. El grupo en la esquina inferior izquierda puede parecer que tiene dos ojos, pero el punto vacío rodeado marcado con una a no es en realidad un ojo. Las blancas pueden jugar allí y tomar una piedra negra. A este punto se le suele llamar ojo falso . [72]

Existe una excepción al requisito de que un grupo debe tener dos ojos para estar vivo, una situación llamada seki (o vida mutua ). Cuando grupos de diferentes colores están adyacentes y comparten libertades, la situación puede llegar a una posición en la que ningún jugador quiere moverse primero porque al hacerlo permitiría al oponente capturar; en tales situaciones, las piedras de ambos jugadores permanecen en el tablero (en seki). Ningún jugador recibe puntos por esos grupos, pero al menos esos grupos permanecen vivos, en lugar de ser capturados. [e]

El seki puede ocurrir de muchas maneras. Las más simples son:

En el diagrama "Ejemplo de seki (vida mutua)", los dos puntos marcados con un círculo son libertades compartidas por un grupo negro y uno blanco. Ambos grupos interiores están en riesgo y ninguno de los jugadores quiere jugar en un punto marcado con un círculo, porque hacerlo permitiría al oponente capturar su grupo en el siguiente movimiento. Los grupos exteriores en este ejemplo, tanto negros como blancos, están vivos. Seki puede resultar de un intento de un jugador de invadir y matar a un grupo casi establecido del otro jugador. [72]

Tactics deal with immediate fighting between stones, capturing and saving stones, life, death and other issues localized to a specific part of the board. Larger issues which encompass the territory of the entire board and planning stone-group connections are referred to as Strategy and are covered in the Strategy section above.

There are several tactical constructs aimed at capturing stones.[73] These are among the first things a player learns after understanding the rules. Recognizing the possibility that stones can be captured using these techniques is an important step forward.

A ladder. Black cannot escape unless the ladder connects to black stones further down the board that will intercept with the ladder or if one of white's pieces has only one liberty.

The most basic technique is the ladder.[74] This is also sometimes called a "running attack", since it unfolds as one player trying to outrun the other's attack. To capture stones in a ladder, a player uses a constant series of capture threats (atari), giving the opponent only one place to place his stone to keep his group alive. This forces the opponent to move into a zigzag pattern (surrounding the ladder on the outside) as shown in the adjacent diagram to keep the attack coming. Unless the pattern runs into friendly stones along the way, the stones in the ladder cannot avoid capture. However, if the ladder can run into other black stones, thus saving them, then experienced players recognize the futility of continuing the attack. These stones can also be saved if a suitably strong threat can be forced elsewhere on the board, so that two Black stones can be placed here to save the group.

A net. The chain of three marked Black stones cannot escape in any direction, since each Black stone attempting to extend the chain outward (on the red circles) can be easily blocked by one White stone.

Another technique to capture stones is the so-called net,[75] also known by its Japanese name, geta. This refers to a move that loosely surrounds some stones, preventing their escape in all directions. An example is given in the adjacent diagram. It is often better to capture stones in a net than in a ladder, because a net does not depend on the condition that there are no opposing stones in the way, nor does it allow the opponent to play a strategic ladder breaker. However, the ladder only requires one turn to kill all the opponent's stones, whereas a net requires more turns to do the same.

A snapback. Although Black can capture the white stone by playing at the circled point, the resulting shape for Black has only one liberty (at 1), thus White can then capture the three black stones by playing at 1 again (snapback).

A third technique to capture stones is the snapback.[76] In a snapback, one player allows a single stone to be captured, then immediately plays on the point formerly occupied by that stone; by so doing, the player captures a larger group of their opponent's stones, in effect snapping back at those stones. An example can be seen on the right. As with the ladder, an experienced player does not play out such a sequence, recognizing the futility of capturing only to be captured back immediately.

One of the most important skills required for strong tactical play is the ability to read ahead.[77] Reading ahead includes considering available moves to play, the possible responses to each move, and the subsequent possibilities after each of those responses. Some of the strongest players of the game can read up to 40 moves ahead even in complicated positions.[78]

As explained in the scoring rules, some stone formations can never be captured and are said to be alive, while other stones may be in a position where they cannot avoid being captured and are said to be dead. Much of the practice material available to players of the game comes in the form of life and death problems, also known as tsumego.[79] In such problems, players are challenged to find the vital move sequence that kills a group of the opponent or saves a group of their own. Tsumego are considered an excellent way to train a player's ability at reading ahead,[79] and are available for all skill levels, some posing a challenge even to top players.

In situations when the Ko rule applies, a ko fight may occur.[63] If the player who is prohibited from capture is of the opinion that the capture is important because it prevents a large group of stones from being captured for instance, the player may play a ko threat.[63] This is a move elsewhere on the board that threatens to make a large profit if the opponent does not respond. If the opponent does respond to the ko threat, the situation on the board has changed, and the prohibition on capturing the ko no longer applies. Thus the player who made the ko threat may now recapture the ko. Their opponent is then in the same situation and can either play a ko threat as well or concede the ko by simply playing elsewhere. If a player concedes the ko, either because they do not think it important or because there are no moves left that could function as a ko threat, they have lost the ko, and their opponent may connect the ko.

Instead of responding to a ko threat, a player may also choose to ignore the threat and connect the ko.[63] They thereby win the ko, but at a cost. The choice of when to respond to a threat and when to ignore it is a subtle one, which requires a player to consider many factors, including how much is gained by connecting, how much is lost by not responding, how many possible ko threats both players have remaining, what the optimal order of playing them is, and what the size—points lost or gained—of each of the remaining threats is.[80]

Frequently, the winner of the ko fight does not connect the ko but instead captures one of the chains that constituted their opponent's side of the ko.[63] In some cases, this leads to another ko fight at a neighboring location.

The earliest written reference to the game is generally recognized as the historical annal Zuo Zhuan[12][13] (c. 4th century BCE),[14] referring to a historical event of 548 BCE. It is also mentioned in Book XVII of the Analects of Confucius[14] and in two books written by Mencius[13][81] (c. 3rd century BCE).[14] In all of these works, the game is referred to as yì (弈). Today, in China, it is known as weiqi (simplified Chinese: 围棋; traditional Chinese: 圍棋; pinyin: ; Wade–Giles: wei ch'i), lit. 'encirclement board game'.

Go was originally played on a 17×17 line grid, but a 19×19 grid became standard by the time of the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE).[13] Legends trace the origin of the game to the mythical Chinese emperor Yao (2337–2258 BCE), who was said to have had his counselor Shun design it for his unruly son, Danzhu, to favorably influence him.[82][83] Other theories suggest that the game was derived from Chinese tribal warlords and generals, who used pieces of stone to map out attacking positions.[84][85]

In China, Go had an important status among elites and was associated with ideas of self-cultivation, wisdom, and gentlemanly ideals.[86]: 23 It was considered one of the four cultivated arts of the Chinese scholar gentleman, along with calligraphy, painting and playing the musical instrument guqin.[87] In ancient times the rules of Go were passed on verbally, rather than being written down.[88]

Go was introduced to Korea sometime between the 5th and 7th centuries CE, and was popular among the higher classes. In Korea, the game is called baduk (Korean: 바둑), and a variant of the game called Sunjang baduk was developed by the 16th century. Sunjang baduk became the main variant played in Korea until the end of the 19th century, when the current version was reintroduced from Japan.[89][90]

The game reached Japan in the 7th century CE—where it is called go (碁) or igo (囲碁). It became popular at the Japanese imperial court in the 8th century,[91] and among the general public by the 13th century.[92] The game was further formalized in the 15th century. In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu re-established Japan's unified national government. In the same year, he assigned the then-best player in Japan, a Buddhist monk named Nikkai (né Kanō Yosaburo, 1559), to the post of Godokoro (Minister of Go).[93]

Nikkai took the name Hon'inbō Sansa and founded the Hon'inbō Go school.[93] Several competing schools were founded soon after.[93] These officially recognized and subsidized Go schools greatly developed the level of play and introduced the dan/kyu style system of ranking players.[94] Players from the four schools (Hon'inbō, Yasui, Inoue and Hayashi) competed in the annual castle games, played in the presence of the shōgun.[95]

Despite its widespread popularity in East Asia, Go has been slow to spread to the rest of the world. Although there are some mentions of the game in western literature from the 16th century forward, Go did not start to become popular in the West until the end of the 19th century, when German scientist Oskar Korschelt wrote a treatise on the game.[96] By the early 20th century, Go had spread throughout the German and Austro-Hungarian empires. In 1905, Edward Lasker learned the game while in Berlin. When he moved to New York, Lasker founded the New York Go Club together with (amongst others) Arthur Smith, who had learned of the game in Japan while touring the East and had published the book The Game of Go in 1908.[97] Lasker's book Go and Go-moku (1934) helped spread the game throughout the U.S.,[97] and in 1935, the American Go Association was formed. Two years later, in 1937, the German Go Association was founded.

World War II put a stop to most Go activity, since it was a popular game in Japan, but after the war, Go continued to spread.[98] For most of the 20th century, the Japan Go Association (Nihon Ki-in) played a leading role in spreading Go outside East Asia by publishing the English-language magazine Go Review in the 1960s, establishing Go centers in the U.S., Europe and South America, and often sending professional teachers on tour to Western nations.[99] Internationally, the game had been commonly known since the start of the twentieth century by its shortened Japanese name, and terms for common Go concepts are derived from their Japanese pronunciation.

In 1996, NASA astronaut Daniel Barry and Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata became the first people to play Go in space. They used a special Go set, which was named Go Space, designed by Wai-Cheung Willson Chow. Both astronauts were awarded honorary dan ranks by the Nihon Ki-in.[100]

As of December 2015[update], the International Go Federation has 75 member countries, with 67 member countries outside East Asia.[101] Chinese cultural centres across the world are promoting Go, and cooperating with local Go associations, for example the seminars held by the Chinese cultural centre in Tel Aviv, Israel, together with the Israeli Go association.[102]

In Go, rank indicates a player's skill in the game. Traditionally, ranks are measured using kyu and dan grades,[103] a system also adopted by many martial arts. More recently, mathematical rating systems similar to the Elo rating system have been introduced.[104] Such rating systems often provide a mechanism for converting a rating to a kyu or dan grade.[104] Kyu grades (abbreviated k) are considered student grades and decrease as playing level increases, meaning 1st kyu is the strongest available kyu grade. Dan grades (abbreviated d) are considered master grades, and increase from 1st dan to 7th dan. First dan equals a black belt in eastern martial arts using this system. The difference among each amateur rank is one handicap stone. For example, if a 5k plays a game with a 1k, the 5k would need a handicap of four stones to even the odds. Top-level amateur players sometimes defeat professionals in tournament play.[105] Professional players have professional dan ranks (abbreviated p). These ranks are separate from amateur ranks.

The rank system comprises, from the lowest to highest ranks:

Tournament and match rules deal with factors that may influence the game but are not part of the actual rules of play. Such rules may differ between events. Rules that influence the game include: the setting of compensation points (komi), handicap, and time control parameters. Rules that do not generally influence the game are the tournament system, pairing strategies, and placement criteria.

Common tournament systems used in Go include the McMahon system,[106] Swiss system, league systems and the knockout system. Tournaments may combine multiple systems; many professional Go tournaments use a combination of the league and knockout systems.[107]

Tournament rules may also set the following:

A game of Go may be timed using a game clock. Formal time controls were introduced into the professional game during the 1920s and were controversial.[110] Adjournments and sealed moves began to be regulated in the 1930s. Go tournaments use a number of different time control systems. All common systems envisage a single main period of time for each player for the game, but they vary on the protocols for continuation (in overtime) after a player has finished that time allowance.[g] The most widely used time control system is the so-called byoyomi[h] system. The top professional Go matches have timekeepers so that the players do not have to press their own clocks.

Two widely used variants of the byoyomi system are:[111]

Go games are recorded with a simple coordinate system. This is comparable to algebraic chess notation, except that Go stones do not move and thus require only one coordinate per turn. Coordinate systems include purely numerical (4–4 point), hybrid (K3), and purely alphabetical.[112] The Smart Game Format uses alphabetical coordinates internally, but most editors represent the board with hybrid coordinates as this reduces confusion.

Alternatively, the game record can also be noted by writing the successive moves on a diagram, where odd numbers mean black stones, even numbers mean white stones (or conversely when playing with a handicap), and a notation like "25=22" in the margin means that the 25th stone was played at the same location as the 22nd one, which had been captured in the meantime.

The Japanese word kifu is sometimes used to refer to a game record.

In Unicode, Go stones can be represented with black and white circles from the block Geometric Shapes:

The block Miscellaneous Symbols includes "Go markers"[113] that were likely meant for mathematical research of Go:[114][115]

A Go professional is a professional player of the game of Go. There are six areas with professional go associations, these are: China (Chinese Weiqi Association), Japan (Nihon Ki-in, Kansai Ki-in), South Korea (Korea Baduk Association), Taiwan (Taiwan Chi Yuan Culture Foundation), the United States (AGA Professional System) and Europe (European Professional System).

Although the game was developed in China, the establishment of the Four Go houses by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the start of the 17th century shifted the focus of the Go world to Japan. State sponsorship, allowing players to dedicate themselves full-time to study of the game, and fierce competition between individual houses resulted in a significant increase in the level of play. During this period, the best player of his generation was given the prestigious title Meijin (master) and the post of Godokoro (minister of Go). Of special note are the players who were dubbed Kisei (Go Sage). The only three players to receive this honor were Dōsaku, Jōwa and Shūsaku, all of the house Hon'inbō.[116]

After the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration period, the Go houses slowly disappeared, and in 1924, the Nihon Ki-in (Japanese Go Association) was formed. Top players from this period often played newspaper-sponsored matches of 2–10 games.[117] Of special note are the (Chinese-born) player Go Seigen (Chinese: Wu Qingyuan), who scored 80% in these matches and beat down most of his opponents to inferior handicaps,[118] and Minoru Kitani, who dominated matches in the early 1930s.[119] These two players are also recognized for their groundbreaking work on new opening theory (Shinfuseki).[120]

For much of the 20th century, Go continued to be dominated by players trained in Japan. Notable names included Eio Sakata, Rin Kaiho (born in Taiwan), Masao Kato, Koichi Kobayashi and Cho Chikun (born Cho Ch'i-hun, from South Korea).[121] Top Chinese and Korean talents often moved to Japan, because the level of play there was high and funding was more lavish. One of the first Korean players to do so was Cho Namchul, who studied in the Kitani Dojo 1937–1944. After his return to Korea, the Hanguk Kiwon (Korea Baduk Association) was formed and caused the level of play in South Korea to rise significantly in the second half of the 20th century.[122] In China, the game declined during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) but quickly recovered in the last quarter of the 20th century, bringing Chinese players, such as Nie Weiping and Ma Xiaochun, on par with their Japanese and South Korean counterparts.[123] The Chinese Weiqi Association (today part of the China Qiyuan) was established in 1962, and professional dan grades started being issued in 1982.[124] Western professional Go began in 2012 with the American Go Association's Professional System.[125] In 2014, the European Go Federation followed suit and started their professional system.[126]

With the advent of major international titles from 1989 onward, it became possible to compare the level of players from different countries more accurately. Cho Hunhyun of South Korea won the first edition of the Quadrennial Ing Cup in 1989. His disciple Lee Chang-ho was the dominant player in international Go competitions for more than a decade spanning much of 1990s and early 2000s; he is also credited with groundbreaking works on the endgame. Cho, Lee and other South Korean players such as Seo Bong-soo, Yoo Changhyuk and Lee Sedol between them won the majority of international titles in this period.[127] Several Chinese players also rose to the top in international Go from 2000s, most notably Ma Xiaochun, Chang Hao, Gu Li and Ke Jie. As of 2016[update], Japan lags behind in the international Go scene.

Historically, more men than women have played Go. Special tournaments for women exist, but until recently, men and women did not compete together at the highest levels; however, the creation of new, open tournaments and the rise of strong female players, most notably Rui Naiwei, have in recent years highlighted the strength and competitiveness of emerging female players.[128]

The level in other countries has traditionally been much lower, except for some players who had preparatory professional training in East Asia.[k] Knowledge of the game has been scant elsewhere up until the 20th century. A famous player of the 1920s was Edward Lasker.[l] It was not until the 1950s that more than a few Western players took up the game as other than a passing interest. In 1978, Manfred Wimmer became the first Westerner to receive a professional player's certificate from an East Asian professional Go association.[129] In 2000, American Michael Redmond became the first Western player to achieve a 9 dan rank.

It is possible to play Go with a simple paper board and coins, plastic tokens, or white beans and coffee beans for the stones; or even by drawing the stones on the board and erasing them when captured. More popular midrange equipment includes cardstock, a laminated particle board, or wood boards with stones of plastic or glass. More expensive traditional materials are still used by many players. The most expensive Go sets have black stones carved from slate and white stones carved from translucent white shells (traditionally Meretrix lamarckii), played on boards carved in a single piece from the trunk of a tree.

The Go board (generally referred to by its Japanese name goban 碁盤) typically measures between 45 and 48 cm (18 and 19 in) in length (from one player's side to the other) and 42 to 44 cm (16+1⁄2 to 17+1⁄4 in) in width. Chinese boards are slightly larger, as a traditional Chinese Go stone is slightly larger to match. The board is not square; there is a 15:14 ratio in length to width, because with a perfectly square board, from the player's viewing angle the perspective creates a foreshortening of the board. The added length compensates for this.[130] There are two main types of boards: a table board similar in most respects to other gameboards like that used for chess, and a floor board, which is its own free-standing table and at which the players sit.

The traditional Japanese goban is between 10 and 18 cm (3.9 and 7.1 in) thick and has legs; it sits on the floor (see picture).[130] It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged Kaya tree (Torreya nucifera), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the related California Torreya (Torreya californica) has been prized for its light color and pale rings as well as its reduced expense and more readily available stock. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the slow-growing Kaya trees; both T. nucifera and T. californica take many hundreds of years to grow to the necessary size, and they are now extremely rare, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.[131] As Kaya trees are a protected species in Japan, they cannot be harvested until they have died. Thus, an old-growth, floor-standing Kaya goban can easily cost in excess of $10,000 with the highest-quality examples costing more than $60,000.[132]

Other, less expensive woods often used to make quality table boards in both Chinese and Japanese dimensions include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), Kauri (Agathis), and Shin Kaya (various varieties of spruce, commonly from Alaska, Siberia and China's Yunnan Province).[131] So-called Shin Kaya is a potentially confusing merchant's term: shin means 'new', and thus shin kaya is best translated 'faux kaya', because the woods so described are biologically unrelated to Kaya.[131]

A full set of Go stones (goishi) usually contains 181 black stones and 180 white ones; a 19×19 grid has 361 points, so there are enough stones to cover the board, and Black gets the extra odd stone because that player goes first. However it may happen, especially in beginners' games, that many back-and-forth captures empty the bowls before the end of the game: in that case an exchange of prisoners allows the game to continue.

Traditional Japanese stones are double-convex, and made of clamshell (white) and slate (black).[133] The classic slate is nachiguro stone mined in Wakayama Prefecture and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam (Meretrix lusoria) or the Korean hard clam; however, due to a scarcity in the Japanese supply of these clams, the stones are most often made of shells harvested from Mexico.[133] Historically, the most prized stones were made of jade, often given to the reigning emperor as a gift.[133]

In China, the game is traditionally played with single-convex stones[133] made of a composite called Yunzi. The material comes from Yunnan Province and is made by sintering a proprietary and trade-secret mixture of mineral compounds derived from the local stone. This process dates to the Tang dynasty and, after the knowledge was lost in the 1920s during the Chinese Civil War, was rediscovered in the 1960s by the now state-run Yunzi company. The material is praised for its colors, its pleasing sound as compared to glass or to synthetics such as melamine, and its lower cost as opposed to other materials such as slate/shell. The term yunzi can also refer to a single-convex stone made of any material; however, most English-language Go suppliers specify Yunzi as a material and single-convex as a shape to avoid confusion, as stones made of Yunzi are also available in double-convex while synthetic stones can be either shape.

Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colors that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones.[133][m]

The bowls for the stones are shaped like a flattened sphere with a level underside.[134] The lid is loose fitting and upturned before play to receive stones captured during the game. Chinese bowls are slightly larger, and a little more rounded, a style known generally as Go Seigen; Japanese Kitani bowls tend to have a shape closer to that of the bowl of a snifter glass, such as for brandy. The bowls are usually made of turned wood. Mulberry is the traditional material for Japanese bowls, but is very expensive; wood from the Chinese jujube date tree, which has a lighter color (it is often stained) and slightly more visible grain pattern, is a common substitute for rosewood, and traditional for Go Seigen-style bowls. Other traditional materials used for making Chinese bowls include lacquered wood, ceramics, stone and woven straw or rattan. The names of the bowl shapes, Go Seigen and Kitani, were introduced in the last quarter of the 20th century by the professional player Janice Kim as homage to two 20th-century professional Go players by the same names, of Chinese and Japanese nationality, respectively, who are referred to as the "Fathers of modern Go".[116]

The traditional way to place a Go stone is to first take one from the bowl, gripping it between the index and middle fingers, with the middle finger on top, and then placing it directly on the desired intersection.[135] One can also place a stone on the board and then slide it into position under appropriate circumstances (where it does not move any other stones). It is considered respectful towards White for Black to place the first stone of the game in the upper right-hand corner.[136] (Because of symmetry, this has no effect on the game's outcome.)

It is considered poor manners to run one's fingers through one's bowl of unplayed stones, as the sound, however soothing to the player doing this, can be disturbing to one's opponent. Similarly, clacking a stone against another stone, the board, or the table or floor is also discouraged. However, it is permissible to emphasize select moves by striking the board more firmly than normal, thus producing a sharp clack. Additionally, hovering one's arm over the board (usually when deciding where to play) is also considered rude as it obstructs the opponent's view of the board.

Manners and etiquette are extensively discussed in 'The Classic of WeiQi in Thirteen Chapters', a Song dynasty manual to the game. Apart from the points above it also points to the need to remain calm and honorable, in maintaining posture, and knowing the key specialised terms, such as titles of common formations. Generally speaking, much attention is paid to the etiquette of playing, as much as to winning or actual game technique.

Go long posed a daunting challenge to computer programmers, putting forward "difficult decision-making tasks, an intractable search space, and an optimal solution so complex it appears infeasible to directly approximate using a policy or value function".[137] Prior to 2015,[137] the best Go programs only managed to reach amateur dan level.[138] On smaller 9×9 and 13x13 boards, computer programs fared better, and were able to compare to professional players. Many in the field of artificial intelligence consider Go to require more elements that mimic human thought than chess.[139]

The reasons why computer programs had not played Go at the professional dan level prior to 2016 include:[140]

It was not until August 2008 that a computer won a game against a professional level player at a handicap of 9 stones, the greatest handicap normally given to a weaker opponent. It was the Mogo program, which scored this first victory in an exhibition game played during the US Go Congress.[147][148] By 2013, a win at the professional level of play was accomplished with a four-stone advantage.[149][150] In October 2015, Google DeepMind's program AlphaGo beat Fan Hui, the European Go champion and a 2 dan (out of 9 dan possible) professional, five times out of five with no handicap on a full size 19×19 board.[137] AlphaGo used a fundamentally different paradigm than earlier Go programs; it included very little direct instruction, and mostly used deep learning where AlphaGo played itself in hundreds of millions of games such that it could measure positions more intuitively. In March 2016, Google next challenged Lee Sedol, a 9 dan considered the top player in the world in the early 21st century,[151] to a five-game match. Leading up to the game, Lee Sedol and other top professionals were confident that he would win;[152] however, AlphaGo defeated Lee in four of the five games.[153][154] After having already lost the series by the third game, Lee won the fourth game, describing his win as "invaluable".[155] In May 2017, AlphaGo beat Ke Jie, who at the time continuously held the world No. 1 ranking for two years,[156][157] winning each game in a three-game match during the Future of Go Summit.[158][159] In October 2017, DeepMind announced a significantly stronger version called AlphaGo Zero which beat the previous version by 100 games to 0.[160]

In February 2023, Kellin Pelrine, an amateur American Go player, won 14 out of 15 games against a top-ranked AI system in a significant victory over artificial intelligence. Pelrine took advantage of a previously unknown flaw in the Go computer program, which had been identified by another computer. He exploited this weakness by slowly encircling the opponent's stones and distracting the AI with moves in other parts of the board. The tactics used by Pelrine have highlighted a fundamental flaw in the deep learning systems that underpin many of today's advanced AI. Although the AI systems can "understand" specific situations, they lack the ability to generalize in a way that humans find easy.[161][162][163]

An abundance of software is available to support players of the game. This includes programs that can be used to view or edit game records and diagrams, programs that allow the user to search for patterns in the games of strong players, and programs that allow users to play against each other over the Internet.

Some web servers[citation needed] provide graphical aids like maps, to aid learning during play. These graphical aids may suggest possible next moves, indicate areas of influence, highlight vital stones under attack and mark stones in atari or about to be captured.

There are several file formats used to store game records, the most popular of which is SGF, short for Smart Game Format. Programs used for editing game records allow the user to record not only the moves, but also variations, commentary and further information on the game.[o]

Electronic databases can be used to study life and death situations, joseki, fuseki and games by a particular player. Programs are available that give players pattern searching options, which allow players to research positions by searching for high-level games in which similar situations occur. Such software generally lists common follow-up moves that have been played by professionals and gives statistics on win–loss ratio in opening situations.

Internet-based Go servers allow access to competition with players all over the world, for real-time and turn-based games.[p] Such servers also allow easy access to professional teaching, with both teaching games and interactive game review being possible.[q]

Apart from technical literature and study material, Go and its strategies have been the subject of several works of fiction, such as The Master of Go by Nobel prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata[r] and The Girl Who Played Go by Shan Sa. Other books have used Go as a theme or minor plot device. For example, the novel Shibumi by Trevanian centers around the game and uses Go metaphors.[164] [165] Go features prominently in the Chung Kuo series of novels by David Wingrove, being the favourite game of the main villain.[166]

The manga (Japanese comic book) and anime series Hikaru no Go, released in Japan in 1998, had a large impact in popularizing Go among young players, both in Japan and—as translations were released—abroad.[167][168]

Similarly, Go has been used as a subject or plot device in film, such as Pi (π), A Beautiful Mind, Tron: Legacy, Knives Out, and The Go Master (a biopic of Go professional Go Seigen).[169][s] 2013's Tôkyô ni kita bakari or Tokyo Newcomer portrays a Chinese foreigner Go player moving to Tokyo.[170] In King Hu's wuxia film The Valiant Ones, the characters are color-coded as Go stones (black or other dark shades for the Chinese, white for the Japanese invaders), Go boards and stones are used by the characters to keep track of soldiers prior to battle, and the battles themselves are structured like a game of Go.[171]

Go has also been featured as a plot device in a number of television series. Examples include Starz's science fiction thriller Counterpart, which is rich in references (the opening itself featuring developments on a Go board), and includes Go matches, accurately played, relevant to the plot.[172] Also, in 2024 Netflix released the historical-fictional Korean series Captivating the King.

The corporation and brand Atari was named after the Go term.[173]

Hedge fund manager Mark Spitznagel used Go as his main investing metaphor in his investing book The Dao of Capital.[174] The Way of Go: 8 Ancient Strategy Secrets for Success in Business and Life by Troy Anderson applies Go strategy to business.[175] GO: An Asian Paradigm for Business Strategy[176] by Miura Yasuyuki, a manager with Japan Airlines,[177] uses Go to describe the thinking and behavior of business men.

A 2004 review of literature by Fernand Gobet, de Voogt and Jean Retschitzki shows that relatively little scientific research has been carried out on the psychology of Go, compared with other traditional board games such as chess.[178] Computer Go research has shown that given the large search tree, knowledge and pattern recognition are more important in Go than in other strategy games, such as chess.[178] A study of the effects of age on Go-playing[179] has shown that mental decline is milder with strong players than with weaker players. According to the review of Gobet and colleagues, the pattern of brain activity observed with techniques such as PET and fMRI does not show large differences between Go and chess. On the other hand, a study by Xiangchuan Chen et al.[180] showed greater activation in the right hemisphere among Go players than among chess players, but the research was inconclusive because strong players from Go were hired while very weak chess players were hired in the original study.[181] There is some evidence to suggest a correlation between playing board games and reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.[182]

Arthur Mary, a French researcher in clinical psychopathology, reports on his psychotherapeutic approaches using the game of Go with patients in private practice and in a psychiatric ward.[183] Drawing on neuroscience research and employing a psychoanalytic (Lacanian) and phenomenological approach, he demonstrates how drives are expressed on the goban.[184] He offers some suggestions to therapists for defining ways of playing go that lead to therapeutic effects.[185]

In formal game theory terms, Go is a non-chance, combinatorial game with perfect information. Informally that means there are no dice used (and decisions or moves create discrete outcome vectors rather than probability distributions), the underlying math is combinatorial, and all moves (via single vertex analysis) are visible to both players (unlike some card games where some information is hidden). Perfect information also implies sequence—players can theoretically know about all past moves.

Other game theoretical taxonomy elements include the facts

In the endgame, it can often happen that the state of the board consists of several subpositions that do not interact with the others. The whole board position can then be considered as a mathematical sum, or composition, of the individual subpositions.[187] It is this property of Go endgames that led John Horton Conway to the discovery of surreal numbers.[188]

In combinatorial game theory terms, Go is a zero-sum, perfect-information, partisan, deterministic strategy game, putting it in the same class as chess, draughts (checkers), and Reversi (Othello).

The game emphasizes the importance of balance on multiple levels: to secure an area of the board, it is good to play moves close together; however, to cover the largest area, one needs to spread out, perhaps leaving weaknesses that can be exploited. Playing too low (close to the edge) secures insufficient territory and influence, yet playing too high (far from the edge) allows the opponent to invade. Decisions in one part of the board may be influenced by an apparently unrelated situation in a distant part of the board (for example, ladders can be broken by stones at an arbitrary distance away). Plays made early in the game can shape the nature of conflict a hundred moves later.

The game complexity of Go is such that describing even elementary strategy fills many introductory books. In fact, numerical estimates show that the number of possible games of Go far exceeds the number of atoms in the observable universe.[t]

Go also contributed to the development of combinatorial game theory (with Go infinitesimals[189] being a specific example of its use in Go).

Go begins with an empty board. It is focused on building from the ground up (nothing to something) with multiple, simultaneous battles leading to a point-based win. Chess is tactical rather than strategic, as the predetermined strategy is to trap one individual piece (the king). This comparison has also been applied to military and political history, with Scott Boorman's book The Protracted Game (1969) and, more recently, Robert Greene's book The 48 Laws of Power (1998) exploring the strategy of the Chinese Communist Party in the Chinese Civil War through the lens of Go.[190][191]

A similar comparison has been drawn among Go, chess and backgammon, perhaps the three oldest games that enjoy worldwide popularity.[192] Backgammon is a "man vs. fate" contest, with chance playing a strong role in determining the outcome. Chess, with rows of soldiers marching forward to capture each other, embodies the conflict of "man vs. man". Because the handicap system tells Go players where they stand relative to other players, an honestly ranked player can expect to lose about half of their games; therefore, Go can be seen as embodying the quest for self-improvement, "man vs. self".[192]