Las matemáticas son el estudio de la representación y el razonamiento sobre objetos abstractos(como números , puntos , espacios , conjuntos , estructuras y juegos ). Las matemáticas se utilizan en todo el mundo como una herramienta esencial en muchos campos, incluidas las ciencias naturales , la ingeniería , la medicina y las ciencias sociales . Las matemáticas aplicadas , la rama de las matemáticas que se ocupa de la aplicación del conocimiento matemático a otros campos, inspiran y utilizan nuevos descubrimientos matemáticos y, en ocasiones, conducen al desarrollo de disciplinas matemáticas completamente nuevas, como la estadística y la teoría de juegos . Los matemáticos también se dedican a la matemática pura , o a la matemática por sí misma, sin tener en mente ninguna aplicación. No existe una línea clara que separe las matemáticas puras y las aplicadas, y a menudo se descubren aplicaciones prácticas para lo que comenzó como matemáticas puras. ( Articulo completo... )

.jpg/440px-Srinivasa_Ramanujan_-_OPC_-_2_(cleaned).jpg)

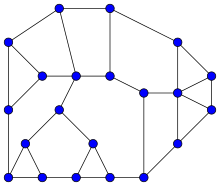

La teoría de juegos es una rama de las matemáticas que se utiliza a menudo en el contexto de la economía . Estudia las interacciones estratégicas entre agentes . En los juegos estratégicos, los agentes eligen estrategias que maximizarán su retorno, dadas las estrategias que eligen los demás agentes. La característica esencial es que proporciona un enfoque de modelado formal de situaciones sociales en las que los tomadores de decisiones interactúan con otros agentes. La teoría de juegos amplía el enfoque de optimización más simple desarrollado en la economía neoclásica .

El campo de la teoría de juegos surgió con la clásica Teoría de los juegos y el comportamiento económico de 1944 de John von Neumann y Oskar Morgenstern . Un centro importante para el desarrollo de la teoría de juegos fue RAND Corporation , donde ayudó a definir estrategias nucleares .

La teoría de juegos ha desempeñado y sigue desempeñando un papel importante en las ciencias sociales y ahora también se utiliza en muchos campos académicos diversos. A partir de la década de 1970, la teoría de juegos se aplicó al comportamiento animal, incluida la teoría de la evolución . Muchos juegos, especialmente el dilema del prisionero , se utilizan para ilustrar ideas en ciencias políticas y ética . La teoría de juegos ha llamado recientemente la atención de los científicos informáticos debido a su uso en inteligencia artificial y cibernética . ( Articulo completo... )

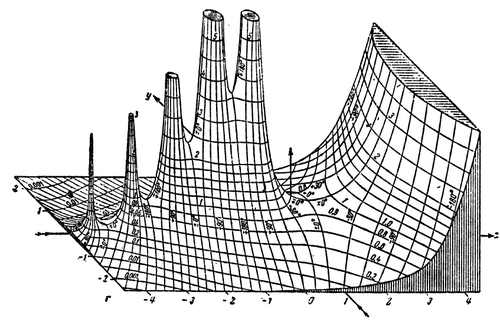

Álgebra | Aritmética | Análisis | Análisis complejo | Matemáticas aplicadas | Cálculo | Teoría de categorías | Teoría del caos | Combinatoria | Sistemas dinámicos | Fractales | Teoría de juegos | Geometría | Geometría algebraica | Teoría de grafos | Teoría de grupos | Álgebra lineal | Lógica matemática | Teoría de modelos | Geometría multidimensional | Teoría de números | Análisis numérico | Optimización | Teoría del orden | Probabilidad y estadística | Teoría de conjuntos | Estadísticas | Topología | Topología algebraica | Trigonometria | Programación lineal

Matemáticas | Historia de las matemáticas | Matemáticos | Premios | Educación | Literatura | Notación | Organizaciones | Teoremas | Pruebas | Problemas no resueltos

![]() Mathematics WikiProject es el centro de edición relacionada con las matemáticas en Wikipedia. Únase a la discusión en la página de discusión del proyecto .

Mathematics WikiProject es el centro de edición relacionada con las matemáticas en Wikipedia. Únase a la discusión en la página de discusión del proyecto .

Los siguientes proyectos hermanos de la Fundación Wikimedia brindan más información sobre este tema: