La dinastía Konbaung ( birmana : ကုန်းဘောင်မင်းဆက် ), también conocida como el Tercer Imperio Birmano (တတိယမြန်မာနိုင် ငံတော်), [9] fue la última dinastía que gobernó Birmania desde 1752 hasta 1885. Creó el segundo imperio más grande en la historia birmana [10] y continuó las reformas administrativas iniciadas por la dinastía Toungoo , sentando las bases del moderno estado de Birmania. Sin embargo, las reformas resultaron insuficientes para detener el avance del Imperio británico , que derrotó a los birmanos en las tres guerras anglo-birmanas a lo largo de un período de seis décadas (1824-1885) y puso fin a la milenaria monarquía birmana en 1885. Pretendientes La dinastía afirma descender de Myat Phaya Lat , una de las hijas de Thibaw. [11]

Los reyes Konbaung, una dinastía expansionista, emprendieron campañas contra Manipur, Assam , Arakan , el reino Mon de Pegu , Siam ( Ayutthaya , Thonburi , Rattanakosin ) y la dinastía Qing de China, estableciendo así el Tercer Imperio Birmano. El estado moderno de Myanmar , sujeto a guerras y tratados posteriores con los británicos, puede rastrear sus fronteras actuales hasta estos eventos.

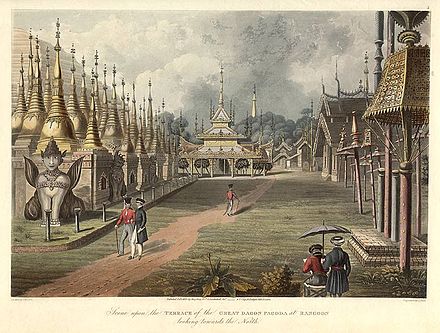

A lo largo de la dinastía Konbaung, la capital fue reubicada varias veces por razones religiosas, políticas y estratégicas.

La dinastía fue fundada por un jefe de aldea, que más tarde sería conocido como Alaungpaya , en 1752 para desafiar al Reino Hanthawaddy restaurado que acababa de derrocar a la dinastía Taungoo . En 1759, las fuerzas de Alaungpaya habían reunificado toda Birmania (y Manipur ) y expulsado a los franceses y los británicos que habían proporcionado armas a Hanthawaddy. [12]

El segundo hijo de Alaungpaya, Hsinbyushin , subió al trono tras un breve reinado de su hermano mayor, Naungdawgyi (1760-1763). Continuó la política expansionista de su padre y finalmente tomó Ayutthaya en 1767, después de siete años de lucha.

En 1760, Birmania inició una serie de guerras con Siam que durarían hasta mediados del siglo XIX. En 1770, los herederos de Alaungpaya habían destruido Ayutthaya Siam (1765-1767) , sometido gran parte de Laos (1765) y derrotado cuatro invasiones de la China Qing (1765-1769). [13] Con los birmanos preocupados durante otras dos décadas por otra inminente invasión de los chinos, [14] Siam se reunificó en 1771 y pasó a capturar Lan Na en 1776. [ 15] Birmania y Siam estuvieron en guerra hasta 1855 , pero después de décadas de guerra, los dos países intercambiaron Tenasserim (a Birmania) y Lan Na (a Siam).

En defensa de su reino, la dinastía libró cuatro guerras con éxito contra la dinastía Qing de China, que veía amenazada la expansión del poder birmano en Oriente. En 1770, a pesar de su victoria sobre los ejércitos chinos, el rey Hsinbyushin pidió la paz con China y firmó un tratado para mantener el comercio bilateral con el Reino Medio, que era muy importante para la dinastía en ese momento. La dinastía Qing abrió entonces sus mercados y restableció el comercio con Birmania en 1788, tras la reconciliación. A partir de entonces, prevalecieron relaciones pacíficas y amistosas entre China y Birmania durante mucho tiempo.

En 1823, emisarios birmanos liderados por George Gibson, hijo de un mercenario inglés, llegaron a la ciudad vietnamita de Saigón . El rey birmano Bagyidaw estaba muy interesado en conquistar Siam y esperaba que Vietnam pudiera ser un aliado útil. Vietnam acababa de anexionarse Camboya. El emperador vietnamita era Minh Mạng , que acababa de subir al trono tras la muerte de su padre, Gia Long (el fundador de la dinastía Nguyen ). Una delegación comercial de Vietnam había estado recientemente en Birmania, ansiosa por expandir el comercio de nidos de pájaros (tổ yến) . Sin embargo, el interés de Bagyidaw en enviar una misión de regreso era asegurar una alianza militar. [16] [17]

Frente a una China poderosa y un Siam resurgente en el este, la dinastía Konbaung tenía ambiciones de expandir el Imperio Konbaung hacia el oeste.

Bodawpaya adquirió los reinos occidentales de Arakan (1784), Manipur (1814) y Assam (1817), lo que dio lugar a una frontera larga y mal definida con la India británica . [18] La corte Konbaung había puesto sus miras en la posible conquista de la Bengala británica cuando estalló la Primera Guerra Anglo-Birmana .

Los europeos comenzaron a establecer puestos comerciales en la región del delta del Irrawaddy durante este período. Konbaung intentó mantener su independencia equilibrándose entre los franceses y los británicos . Al final fracasó, los británicos rompieron relaciones diplomáticas en 1811 y la dinastía luchó y perdió tres guerras contra el Imperio británico , que culminaron con la anexión total de Birmania por parte de los británicos.

Los británicos derrotaron a los birmanos en la primera guerra anglo-birmana (1824-1826) tras enormes pérdidas para ambos bandos, tanto en términos de personal como de activos financieros. Birmania tuvo que ceder Arakan, Manipur, Assam y Tenasserim , y pagar una cuantiosa indemnización de un millón de libras .

En 1837, el hermano del rey Bagyidaw , Tharrawaddy , tomó el trono, puso a Bagyidaw bajo arresto domiciliario y ejecutó a la reina principal Me Nu y a su hermano. Tharrawaddy no hizo ningún intento por mejorar las relaciones con Gran Bretaña.

Su hijo Pagan , que se convirtió en rey en 1846, ejecutó a miles (algunas fuentes dicen que hasta 6.000) de sus súbditos más ricos e influyentes con acusaciones falsas. [19] Durante su reinado, las relaciones con los británicos se volvieron cada vez más tensas. En 1852, estalló la segunda guerra anglo-birmana . Pagan fue sucedido por su hermano menor, el progresista Mindon .

Los gobernantes Konbaung, conscientes de la necesidad de modernizarse, intentaron llevar a cabo diversas reformas con un éxito limitado. El rey Mindon y su hábil hermano, el príncipe heredero Kanaung, establecieron fábricas estatales para producir armas y bienes modernos ; al final, estas fábricas resultaron más costosas que efectivas para evitar la invasión y la conquista extranjeras.

Los reyes Konbaung ampliaron las reformas administrativas iniciadas en el período de la dinastía Toungoo restaurada (1599-1752) y alcanzaron niveles sin precedentes de control interno y expansión externa. Reforzaron el control en las tierras bajas y redujeron los privilegios hereditarios de los jefes Shan . También instituyeron reformas comerciales que aumentaron los ingresos del gobierno y los hicieron más predecibles. La economía monetaria continuó ganando terreno. En 1857, la corona inauguró un sistema completo de impuestos y salarios en efectivo, con la ayuda de la primera moneda de plata estandarizada del país. [20]

Mindon también intentó reducir la carga fiscal bajando el pesado impuesto sobre la renta y creó un impuesto a la propiedad , así como aranceles a las exportaciones extranjeras. Estas políticas tuvieron el efecto contrario de aumentar la carga fiscal, ya que las élites locales aprovecharon la oportunidad para promulgar nuevos impuestos sin reducir los antiguos; pudieron hacerlo porque el control desde el centro era débil. Además, los aranceles a las exportaciones extranjeras sofocaron el floreciente comercio.

Mindon intentó acercar a Birmania a un mayor contacto con el mundo exterior y fue anfitrión del Quinto Gran Sínodo Budista en 1872 en Mandalay , ganándose el respeto de los británicos y la admiración de su propio pueblo.

Mindon evitó la anexión en 1875 cediendo los Estados Karenni .

Sin embargo, el alcance y el ritmo de las reformas fueron desiguales y, en última instancia, resultaron insuficientes para detener el avance del colonialismo británico. [21]

Murió antes de poder nombrar a un sucesor, y Thibaw , un príncipe menor, fue colocado en el trono por Hsinbyumashin , una de las reinas de Mindon, junto con su hija, Supayalat . ( Rudyard Kipling la menciona como la reina de Thibaw, y toma prestado su nombre, en su poema " Mandalay "). El nuevo rey Thibaw procedió, bajo la dirección de Supayalat, a masacrar a todos los posibles contendientes al trono. Esta masacre fue llevada a cabo por la reina. [ cita requerida ]

La dinastía llegó a su fin en 1885 con la abdicación forzada y el exilio del rey y la familia real a la India. Los británicos, alarmados por la consolidación de la Indochina francesa , anexaron el resto del país en la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Birmana en 1885. La anexión fue anunciada en el parlamento británico como regalo de Año Nuevo a la Reina Victoria el 1 de enero de 1886.

Aunque la dinastía había conquistado vastas extensiones de territorio, su poder directo se limitaba a su capital y a las fértiles llanuras del valle del río Irrawaddy . Los gobernantes Konbaung establecieron severas exacciones y tuvieron dificultades para combatir las rebeliones internas. En diversas ocasiones, los estados Shan pagaron tributo a la dinastía Konbaung, pero a diferencia de las tierras Mon, nunca estuvieron bajo el control directo de los birmanos.

La dinastía Konbaung era una monarquía absoluta . Como en el resto del sudeste asiático, el concepto tradicional de realeza aspiraba a que los Chakravartin (Monarcas Universales) crearan su propio mandala o campo de poder dentro del universo Jambudipa , junto con la posesión del elefante blanco que les permitía asumir el título de Hsinbyushin o Hsinbyumyashin (Señor de los Elefantes Blancos), jugó un papel importante en sus esfuerzos. De mayor importancia terrenal fue la amenaza histórica de incursiones periódicas y ayuda a rebeliones internas, así como la invasión e imposición de señoríos de los reinos vecinos de los Mon, Tai Shans y Manipuris. [22]

El reino estaba dividido en provincias llamadas myo ( မြို့ ). [23] [24] Estas provincias eran administradas por Myosa ( မြို့စား ), que eran miembros de la familia real o los funcionarios de más alto rango del Hluttaw. [25] Recaudaban ingresos para el gobierno real, pagaderos al Shwedaik (Tesoro Real) en cuotas fijas y retenían lo que sobraba. [25] Cada myo se subdividía en distritos llamados taik ( တိုက် ), que contenían conjuntos de aldeas llamadas ywa ( ရွာ ). [23]

Las provincias costeras periféricas del reino ( Pegu , Tenasserim , Martaban y Arakan ) eran administradas por un virrey llamado Myowun , que era designado por el rey y poseía poderes civiles, judiciales, fiscales y militares. [25] Los consejos provinciales ( myoyon ) estaban formados por myo saye (escribas de la ciudad), nakhandaw (receptores de las órdenes reales), sitke (jefes de guerra), htaunghmu (carcelero), ayatgaung (jefe del barrio) y dagahmu (guardián de las puertas). [26] Cada provincia estaba dividida en distritos llamados myo , cada uno dirigido por un myo ok (si era designado), o por un myo thugyi (si el cargo era hereditario). [26] El virrey de Pegu era asistido por varios funcionarios adicionales, entre ellos un akhunwun (oficial de ingresos), un akaukwun (recaudador de aduanas) y un yewun (conservador del puerto). [27]

Los feudos tributarios periféricos en los límites del reino eran autónomos en la práctica y nominalmente administrados por el rey. [28] Estos incluían los reinos de habla tai (lo que se convirtió en los Estados Shan durante el gobierno británico), Palaung, Kachin y Manipuri . Los príncipes tributarios de estos feudos juraban lealtad regularmente y ofrecían tributo a los reyes Konbaung (a través de rituales llamados gadaw pwedaw ) [29] y se les otorgaban privilegios reales y eran designados sawbwa (de Shan saopha, 'señor del cielo') [28] [30] En particular, las familias de los sawbwa Shan se casaban regularmente con miembros de la aristocracia birmana y tenían un estrecho contacto con la corte Konbaung. [28]

El gobierno estaba administrado centralmente por varias agencias reales asesoras, siguiendo un patrón establecido durante la dinastía Taungoo . [31]

El Hluttaw ( လွှတ်တော် , lit. "lugar de liberación real", cf Consejo de Estado) [32] tenía funciones legislativas, ministeriales y judiciales, administrando el gobierno real según lo delegado por el rey. [32] Las sesiones en el Hluttaw se celebraban durante 6 horas diarias, de 6 a 9 am, y de mediodía a 3 pm. [33] Enumerado por rango, el Hluttaw estaba compuesto por:

El Byedaik ( ဗြဲတိုက် , lit. "Cámaras de solteros", con Bye derivando de Mon blai ( Mon : ဗ္ကဲာ , "soltero") sirvió como Consejo Privado manejando los asuntos internos de la corte y también sirvió como interlocutor entre el rey y otras agencias reales. [38] El Byedaik estaba compuesto por:

El Shwedaik ( ရွှေတိုက် ) era el Tesoro Real y, como tal, servía como depósito de los metales preciosos y tesoros del estado. [43] Además, el Shwedaik conservaba los archivos del estado y mantenía varios registros, incluidas genealogías detalladas de funcionarios hereditarios e informes del censo. [43] [42] El Shwedaik estaba compuesto por:

Cada agencia real incluía un gran séquito de funcionarios de nivel medio y bajo responsables de los asuntos cotidianos. Entre ellos se encontraban:

y 3 clases de oficiales ceremoniales:

La sociedad Konbaung estaba centrada en el rey, que tomaba muchas esposas y engendraba numerosos hijos, creando una enorme familia real extensa que constituía la base de poder de la dinastía y competía por la influencia en la corte real. También planteaba problemas de sucesión que a menudo terminaban en masacres reales.

The Lawka Byuha Kyan ( လောကဗျူဟာကျမ်း ), also known as the Inyon Sadan ( အင်းယုံစာတန်း ), is the earliest extant work on Burmese court protocols and customs. [46] La obra fue escrita por Inyon Wungyi Thiri Uzana, también conocida como Inyon Ywaza, durante el reinado de Alaungpaya , el fundador de la dinastía Konbaung. [47]

La vida en la corte real durante la dinastía Konbaung consistía tanto en rituales y ceremonias codificadas como en aquellas que se innovaban con el avance de la dinastía. Muchas ceremonias se componían de ideas hindúes localizadas y adaptadas a tradiciones existentes, tanto de origen birmano como budista. Estos rituales también se utilizaban para legitimar el gobierno de los reyes birmanos, ya que los monarcas Konbaung afirmaban descender de Maha Sammata a través del clan Sakyan (del que Gautama Buda era miembro) y la Casa de Vijaya . [48] La vida en la corte real estaba estrechamente regulada. Los eunucos ( မိန်းမဆိုး ) supervisaban a las damas de la casa real y los apartamentos. [49] Las reinas y concubinas inferiores no podían residir en los edificios principales del palacio. [49]

Los brahmanes, generalmente conocidos como ponna ( ပုဏ္ဏား ) en birmano, servían como especialistas en ceremonias rituales, astrología y ritos devocionales a las deidades hindúes en la corte Konbaung. [50] Jugaban un papel esencial en los rituales de elección de reyes, ceremonias de consagración y ablución llamadas abhiseka ( ဗိဿိတ် ). [51] Los brahmanes de la corte ( ပုရောဟိတ် , parohita ) estaban bien integrados en la vida diaria de la corte, asesorando y consultando al rey sobre diversos asuntos. [52] Una jerarquía social entre los brahmanes determinaba sus respectivos deberes y funciones. [52] Los brahmanes astrólogos llamados huya ( ဟူးရား ) eran responsables de determinar los cálculos astrológicos, como determinar el momento propicio para la fundación de una nueva capital, un nuevo palacio, pagoda o asunción de la residencia real, anunciar un nombramiento, dejar un lugar, visitar una pagoda o iniciar una campaña militar. [53] También establecieron el calendario religioso, prepararon el almanaque ( သင်္ကြန်စာ ), calcularon los próximos eclipses solares y lunares, identificaron los principales días festivos basados en el ciclo lunar y comunicaron los tiempos y fechas propicios. [53] Un grupo especial de brahmanes que realizaban rituales abhiseka también fueron seleccionados como pyinnya shi ( ပညာရှိ ), consejeros reales designados. [54]

También se organizaron eventos suntuosos en torno a las ceremonias de vida de los miembros de la familia real. [55] Los brahmanes presidían muchas de estas ceremonias auspiciosas, incluida la construcción de una nueva capital real; la consagración del nuevo palacio, la ceremonia real del arado; las ceremonias de nombramiento, primera alimentación con arroz y cuna; los rituales de unción de la cabeza del abhiseka y la participación del rey en las celebraciones del Año Nuevo birmano (Thingyan). [56] Durante Thingyan, un grupo de 8 brahmanes rociaba agua bendecida por un grupo de 8 monjes budistas, por todo el recinto del palacio, en el Hluttaw , varios patios, las principales puertas de la ciudad y las 4 esquinas de la capital. [56] El rey asistía a muchas de las ceremonias que involucraban a miembros de la familia real, desde ceremonias de cuna ( ပုခက်မင်္ဂလာ ) hasta ceremonias de perforación de orejas, desde bodas hasta funerales. [55]

Algunos edificios del palacio real servían como sede de diversas ceremonias de la vida. Por ejemplo, el Gran Salón de Audiencias era donde los jóvenes príncipes se sometían a la ceremonia de mayoría de edad shinbyu y eran ordenados como monjes novicios . [57] Este era también el lugar donde los jóvenes príncipes ceremonialmente se ataban el cabello en un moño ( သျှောင်ထုံး ). [57] Las elaboradas fiestas de Año Nuevo birmano tenían lugar en el Hmannandawgyi (Palacio de los Espejos): el tercer día del Año Nuevo, el rey y la reina principal participaban de arroz Thingyan, arroz cocido mojado en agua perfumada fría, mientras estaban sentados en su trono. [58] También se celebraban representaciones musicales y dramáticas y otras fiestas en ese complejo. [58]

Las funciones más importantes de la corte durante el reinado de un rey eran los abhiseka o rituales consagratorios, que se celebraban en varias ocasiones durante el reinado de un rey, para reforzar su lugar como patrón de la religión ( Sasana ) y la rectitud. [55] Todos los rituales abhiseka implicaban verter agua de una caracola sobre la cabeza del candidato (normalmente el rey), instruyéndole sobre lo que debía o no debía hacer por amor a su pueblo y advirtiéndole de que si no cumplía, podría sufrir ciertas miserias. [56] Los rituales de ablución eran responsabilidad de un grupo de 8 brahmanes de élite especialmente cualificados para realizar el ritual. [56] Debían permanecer castos antes de la ceremonia. [56] Otro grupo de brahmanes era responsable de la consagración del Príncipe Heredero. [56]

En total, había 14 tipos de ceremonias abhiseka : [56]

Rajabhiseka ( ရာဇဘိသိက် ): la coronación del rey, presidida por brahmanes, era el ritual más importante de la corte real. [59] [61] La ceremonia se celebraba típicamente en el mes birmano de Kason , pero no necesariamente ocurría durante el comienzo de un reinado. [61] [59] El Sasanalinkaya afirma que Bodawpaya , como su padre, fue coronado solo después de establecer el control sobre la administración del reino y purificar las instituciones religiosas. [61] Las características más importantes de este ritual eran: la obtención del agua de la unción; el baño ceremonial; la unción; y el juramento del rey. [62]

Se hicieron preparativos elaborados precisamente para esta ceremonia. Se construyeron tres pabellones ceremoniales ( Sihasana o Trono del León ; Gajasana o Trono del Elefante; y el Marasana o Trono del Pavo Real) en una parcela de tierra específicamente designada (llamada el "jardín del pavo real") para esta ocasión. [63] También se hicieron ofrendas a las deidades y se cantaron parittas budistas. [59] Individuos especialmente designados, generalmente las hijas de dignatarios, incluidos comerciantes y brahmanes, fueron encargados de obtener agua para ungir en medio de un río. [64] El agua se colocó en los respectivos pabellones. [65]

En un momento propicio, el rey se vistió con el traje de un Brahma y la reina con el de una reina de devaloka . [66] La pareja fue escoltada a los pabellones en procesión, acompañada por un caballo blanco o un elefante blanco. [67] [66] El rey primero bañó su cuerpo en el pabellón Morasana, luego su cabeza en el pabellón Gajasana. [68] Luego entró en el pabellón Sihasana para asumir su asiento en el trono de coronación, elaborado para parecerse a una flor de loto floreciente , hecho de madera de higuera y pan de oro aplicado. [68] Los brahmanes le entregaron los cinco artículos de la vestimenta de la coronación ( မင်းမြောက်တန်ဆာ , Min Myauk Taza ):

En su trono, ocho princesas ungieron al rey vertiendo agua especialmente obtenida sobre su cabeza, cada una usando una caracola deslumbrada con gemas blancas, conjurándolo solemnemente con fórmulas para gobernar con justicia. [68] [67] Luego, los brahmanes levantaron un paraguas blanco sobre la cabeza del rey. [67] Esta unción fue repetida por ocho brahmanes de sangre pura y ocho comerciantes. [70] Después, el rey repitió las palabras atribuidas a Buda al nacer: "¡Soy el primero en todo el mundo! ¡Soy el más excelente en todo el mundo! ¡Soy incomparable en todo el mundo!" e hizo la invocación vertiendo agua de una jarra de oro. [67] El ritual terminó con el rey refugiándose en las Tres Joyas . [67]

Como parte de la coronación, se liberaron prisioneros. [70] El rey y su séquito regresaron al palacio, y los pabellones ceremoniales fueron desmantelados y arrojados al río. [71] Siete días después de la ceremonia, el rey y los miembros de la familia real hicieron una procesión inaugural, rodeando el foso de la ciudad en una barcaza estatal dorada, en medio de música festiva y espectadores. [60]

Uparājabhiseka ( ဥပရာဇဘိသေက ) – la Instalación del Uparaja (Príncipe Heredero), en birmano Einshe Min ( အိမ်ရှေ့မင်း ), era uno de los rituales más importantes en el reinado del rey. La Ceremonia de Instalación tenía lugar en el Byedaik (Consejo Privado). [72] El Príncipe Heredero era investido, recibía aparamentos e insignias, y se le otorgaban una multitud de regalos. [73] El rey también nombró formalmente un séquito de personal doméstico para supervisar los asuntos públicos y privados del Príncipe. [74] Después, el Príncipe Heredero fue desfilado hasta su nuevo Palacio, compadeciéndose de su nuevo rango. [75] Comenzaron entonces los preparativos para una boda real con una princesa especialmente preparada para convertirse en la consorte del nuevo rey. [75]

Kun U Khun Mingala ( ကွမ်းဦးခွံ့မင်္ဂလာ ): la ceremonia de la Alimentación del Primer Betel se celebraba unos 75 días después del nacimiento de un príncipe o princesa para reforzar la salud, la prosperidad y la belleza del recién nacido. [76] La ceremonia implicaba la alimentación de betel , mezclada con alcanfor y otros ingredientes. Un funcionario designado ( ဝန် ) organizaba los rituales previos a la ceremonia. [76] Estos rituales incluían un conjunto específico de ofrendas al Buda, a los espíritus indígenas ( yokkaso , akathaso , bhummaso , etc.), a los Guardianes del Sasana y a los padres y abuelos del niño, todos los cuales se organizaban en la cámara del infante. [77] Se hicieron ofrendas adicionales a los Cien Phi ( ပီတစ်ရာနတ် ), un grupo de 100 espíritus siameses encabezados por Nandi ( နန္ဒီနတ်သမီး ), personificado por una figura brahmán hecha de hierba kusa , que era ceremonial. Le daba bolas de arroz cocido con la mano izquierda. [77] [78]

Nāmakaraṇa ( နာမကရဏ ): la ceremonia de nombramiento se llevó a cabo 100 días después del nacimiento de un príncipe o princesa. [77] También se ofreció comida para los dignatarios y artistas presentes. [79] El nombre del bebé se inscribió en una placa de oro o en una hoja de palma . [79] La noche anterior a la ceremonia,se celebró un pwe para los asistentes. [79] Al amanecer de la ceremonia, los monjes budistas pronunciaron un sermón en la corte. [78] Después, en el apartamento de la Reina Principal, el bebé fue sentado en un diván con la Reina Principal, con los respectivos asistentes de la corte real sentados según su rango. [80] Un Ministro del Interior presidió entonces las ofrendas ceremoniales ( ကုဗ္ဘီး ) hechas a la Triple Gema , los 11 devas encabezados por Thagyamin , 9 deidades hindúes, nat indígenas y los 100 Phi . [81] [80] Luego se recitó una oración protectora. [82] Después de la oración, un pyinnyashi preparó y 'alimentó' a Nandi. En el momento auspicioso calculado por los astrólogos, el heraldo real leyó el nombre del infante tres veces. [82] Después, otro heraldo real recitó un inventario de los regalos ofrecidos por los dignatarios presentes. [82] Al cierre de la ceremonia, se produjo un banquete, con los asistentes alimentados en orden de precedencia. [82] Las ofrendas al Buda se enviaban a las pagodas, y las de Nandi, a los brahmanes sacrificadores. [82]

Lehtun Mingala ( လယ်ထွန်မင်္ဂလာ ) [83] – la Ceremonia Real de Arado era un festival anual en el que se rompía la tierra con arados en los campos reales al este de la capital real, para asegurar suficientes lluvias durante el año propiciando al Moekhaung Nat, que se creía que controlaba la lluvia. [49] [84] La ceremonia estaba tradicionalmente vinculada a un evento en la vida de Gotama Buddha . Durante el arado real de los campos por parte del rey Suddhodana , el niño Buda se levantó, se sentó con las piernas cruzadas y comenzó a meditar, bajo la sombra de un árbol de manzana rosa . [85]

The ceremony was held at the beginning of June, at the break of the southwest monsoon.[86] For the ceremony, the king, clad in state robes (a paso with the peacock emblem (daungyut)), a long silk surcoat or tunic encrusted with jewels, a spire-like crown (tharaphu), and 24 strings of the salwe across his chest, and a gold plate or frontlet over his forehead) and his audience made a procession to the leya (royal fields).[87] At the ledawgyi, a specially designated plot of land, milk-white oxen were attached to royal ploughs covered with gold leaf, stood ready for ploughing by ministers, princes and the kings.[88] The oxen were decorated with gold and crimson bands, reins bedecked with rubies and diamonds, and heavy gold tassels hung from the gilded horns.[88] The king initiated the ploughing, and shared this duty among himself, ministers and the princes.[89] After the ceremonial ploughing of the ledawgyi was complete, festivities sprung up throughout the royal capital.[89]

At Thingyan and at the end of the Buddhist lent, the king's head was ceremonially washed with water from Gaungsay Gyun (lit. Head Washing Island) between Martaban and Moulmein, near the mouth of the Salween River.[90] After the Second Anglo-Burmese War (which resulted in Gaungsay Gyun falling under British possession), purified water from Irrawaddy River was instead procured. This ceremony also preceded the earboring, headdressing, and marriage ceremonies of the royal family.[91]

The Obeisance ceremony was a grand ceremony held at the Great Audience Hall thrice a year where tributary princes and courtiers laid tribute, paid homage to their benefactor, the Konbaung king, and swore their allegiance to the monarchy.[49] The ceremony was held 3 times a year:

During this ceremony, the king was seated at the Lion Throne, along with the chief queen, to his right.[57] The Crown Prince was seated immediately before the throne in a cradle-like seat, followed by princes of the blood (min nyi min tha).[57] Constituting the audience were courtiers and dignitaries from vassal states, who were seated according to rank, known in Burmese as Neya Nga Thwe (နေရာငါးသွယ်):[57]

There, the audience paid obeisance to the monarch and renewed their allegiance to the monarch.[57] Women, barring the chief queen, were not permitted to be seen during these ceremonies.[57] Lesser queens, ministers' wives and other officials were seated in a room behind the throne: the queens were seated in the centre within the railing surrounding the flight of steps, while the wives of ministers and others sat in the space without.[57]

Throughout the Konbaung dynasty, the royal family performed ancestral rites to honour their immediate ancestors. These rites were performed at the thrice a year at the Zetawunsaung (Jetavana Hall or "Hall of Victory"), which housed the Goose Throne (ဟင်္သာသနပလ္လင်), immediately preceding the Obeisance Ceremony.[94] On a platform in a room to the west of hall, the king and members of the royal family paid obeisance to images of monarchs and consorts of the Konbaung dynasty. Offerings and Pali prayers from a book of odes were also made to the images.[94] The images, which stood 6 to 24 inches (150 to 610 mm) tall, were made of solid gold.[95] Images were only made for Konbaung kings at their death (if he died on the throne) or for Konbaung queens (if she died while her consort was on throne), but not of a king who died after deposition or a queen who survived her husband.[95] Items used by the deceased personage (e.g. sword, spear, betel box) were preserved along with the associated image.[95] After the British conquest of Upper Burma, 11 images fell into the hands of the Superintendent at the Governor's Residence, Bengal, where they were melted down.[95]

When a king died, his royal white umbrella was broken and the great drum and gong at the palace's bell tower (at the eastern gate of the palace), was struck.[69] It was custom for members of the royal family, including the king, to be cremated: their ashes were put into a velvet bag and thrown into the river.[96] King Mindon Min was the first to break tradition; his remains were not cremated, but instead were buried intact, according to his wishes, at the place where his tomb now stands.[96] Before his burial, the King Mindon's body was laid in state before his throne at the Hmannandawgyi (Palace of Mirrors).[58][57]

The Foundation Sacrifice was a Burmese practice whereby human victims known as myosade (မြို့စတေး) were ceremonially sacrificed by burial during the foundation of a royal capital, to propitiate and appease the guardian spirits. to ensure impregnability of the capital city.[97] The victims were crushed to death underneath a massive teak post erected near each gateway, and at the four corners of the city walls, to render the city secure and impregnable.[98] Although this practice contradicted the fundamental tenets of Buddhism, it was in alignment with prevailing animistic beliefs, which dictated that the spirits of persons who suffered violent deaths became nats (spirits) and protective and possessive of their death sites.[98] The preferred sites for such executions were the city's corners and the gates, the most vulnerable defence points.[98]

The Konbaung monarchs followed ancient precedents and traditions to found the new royal city. Brahmins were tasked with planning these sacrificial ceremonies and determining the auspicious day according to astrological calculations and the signs of individuals best suited for sacrifice.[98] Usually, victims were selected from a spectrum of social classes, or unfortuitiously apprehended against will during the day of the sacrifice.[98] Women in the latter stages of pregnancy were preferred, as the sacrifice would yield two guardian spirits instead of one.[98]

Such sacrifices took place at the foundation of Wunbe In Palace in Ava in 1676 and may have taken place at the foundation of Mandalay in 1857.[97] Royal court officials at the time claimed that the tradition was dispensed altogether, with flowers and fruit offered in lieu of human victims.[98] Burmese chronicles and contemporary records only make mention of large jars of oil buried at the identified locations, which was, by tradition, to ascertain whether the spirits would continue to protect the city (i.e., so long as the oil remained intact, the spirits were serving their duty).[98] Shwe Yoe's The Burman describes 52 men, women and children buried, with 3 buried under the post near each of the twelve gates of the city walls, one at each corner of those walls, one at each corner of the teak stockade, one under each of the four entrances to the Palace, and four under the Lion Throne.[99] Taw Sein Ko's Annual Report for 1902–03 for the Archaeological Survey of India mentions only four victims buried at the corners of the city walls.

Brahmins at the Konbaung court regularly performed a variety of grand devotional rituals to indigenous spirits (nat) and Hindu deities.[55] The following were the most important devotional cults:

During the Konbaung dynasty, Burmese society was highly stratified. Loosely modelled on the four Hindu varnas, Konbaung society was divided into four general social classes (အမျိုးလေးပါး) by descent:[93]

Society also distinguished between the free and slaves (ကျွန်မျိုး), who were indebted persons or prisoners of war (including those brought back from military campaigns in Arakan, Ayuthaya, and Manipur), but could belong to one of the four classes. There was also distinction between taxpayers and non-taxpayers. Tax-paying commoners were called athi (အသည်), whereas non-taxpaying individuals, usually affiliated to the royal court or under government service, were called ahmuhtan (အမှုထမ်း).

Outside of hereditary positions, there were two primary paths to influence: joining the military (မင်းမှုထမ်း) and joining the Buddhist Sangha in the monasteries.

Sumptuary laws called yazagaing dictated life and consumption for Burmese subjects in the Konbaung kingdom, everything from the style of one's house to clothing suitable to one's social standing from regulations concerning funerary ceremonies and the coffin to be used to usage of various speech forms based on rank and social status.[109][110][111] In particular, sumptuary laws in the royal capital were exceedingly strict and the most elaborate in character.[112]

For instance, sumptuary laws forbade ordinary Burmese subjects to build houses of stone or brick and dictated the number of tiers on the ornamental spired roof (called pyatthat) allowed above one's residence— the royal palace's Great Audience Hall and the 4 main gates of the royal capital, as well as monasteries, were allowed 9 tiers while those of the most powerful tributary princes (sawbwa) were permitted 7, at most.[113][114]

Sumptuary laws ordained 5 types of funerals and rites accorded to each: the king, royal family members, holders of ministerial offices, merchants and those who possessed titles, and peasants (who received no rites at death).[115]

Sumptuary regulations regarding dress and ornamentation were carefully observed. Designs with the peacock insignia were strictly reserved for the royal family and long-tailed hip-length jackets (ထိုင်မသိမ်းအင်္ကျီ) and surcoats were reserved for officials.[116] Velvet sandals (ကတ္တီပါဖိနပ်) were worn exclusively by royals.[117] Gold anklets were worn only by the royal children. [109] Silk cloth, brocaded with gold and silver flowers and animal figures were only permitted to be worn by members of the royal family and ministers’ wives. [109] Adornment with jewels and precious stones was similarly regulated. Usage of hinthapada (ဟင်္သပဒါး), a vermilion dye made from cinnabar was regulated.[109]

Throughout the Konbaung dynasty, cultural integration continued. For the first time in history, the Burmese language and culture came to predominate the entire Irrawaddy valley, with the Mon language and ethnicity completely eclipsed by 1830. The nearer Shan principalities adopted more lowland norms.

Captives from various military campaigns in their hundreds and thousands were brought back to the kingdom and resettled as hereditary servants to royalty and nobility or dedicated to pagodas and temples; these captives added new knowledge and skills to Burmese society and enriched Burmese culture. They were encouraged to marry into the host community thus enriching the gene pool as well.[118] Captives from Manipur formed the cavalry called Kathè myindat (Cassay Horse) and also Kathè a hmyauk tat (Cassay Artillery) in the royal Burmese army. Even captured French soldiers, led by Chevalier Milard, were forced into the Burmese army.[119] The incorporated French troops with their guns and muskets played a key role in the later battles between the Burmese and the Mons. They became an elite corps, which was to play a role in the Burmese battles against the Siamese (attacks and capture of Ayutthaya from 1760 to 1765) and the Manchus (battles against the Chinese armies of the Qianlong Emperor from 1766 to 1769).[119] Muslim eunuchs from Arakan also served in the Konbaung court.[120][121][122][123][124]

A small community of foreign scholars, missionaries and merchants also lived in Konbaung society. Besides mercenaries and adventurers who had offered their services since the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century, a few Europeans served as ladies-in-waiting to the last queen Supayalat in Mandalay, a missionary established a school attended by Mindon's several sons including the last king Thibaw, and an Armenian had served as a king's minister at Amarapura.

Among the most visible non-Burmans of the royal court were Brahmins. They typically originated from one of four locales:

The evolution and growth of Burmese literature and theatre continued, aided by an extremely high adult male literacy rate for the era (half of all males and 5% of females).[127] Foreign observers such as Michael Symes remarked on widespread literacy among commoners, from peasants to watermen.[118]

The Siamese captives carried off from Ayutthaya as part of the Burmese–Siamese War (1765–67) went on to have an outsize influence on traditional Burmese theatre and dance. In 1789, a Burmese royal commission consisting of Princes and Ministers was charged with translating Siamese and Javanese dramas from Thai to Burmese. With the help of Siamese artists captured from Ayutthaya in 1767, the commission adapted two important epics from Thai to Burmese: the Siamese Ramayana and the Enao, the Siamese version of Javanese Panji tales into Burmese Yama Zattaw and Enaung Zattaw.[128] One classical Siamese dance, called Yodaya Aka (lit. Ayutthaya-style dance) is considered one of the most delicate of all traditional Burmese dances.

.jpg/440px-013_Boating_(8946785984).jpg)

During the Konbaung period, the techniques of European painting like linear perspective, chiaroscuro and sfumato became more established amongst Burmese painting style.[129][page needed] Temple paintings from this period utilized techniques such as by casting shadows and distance haze on traditional Burmese styles.[130] The Konbaung period also developed parabaik folding-book manuscripts styles that recorded court and royal acitivies by painting on white parakbaik.[131]

In the earlier part of the dynasty between 1789 and 1853, the Amarapura style of Buddha image statuary art developed. Artisans used a unique style using wood gild with gold leaf and red lacquer. The rounder faced image of the Buddha from this period may have been influenced by the capture of the Mahamuni Image from Arakan.[132] After Mindon Min moved the capital to Mandalay, a new Mandalay style of Buddha images developed, depicting a new curly-haired Buddha image and using alabaster and bronze as materials. This later style would be retained through the British colonial period.[133]

Burmese dynasties had a long history of building regularly planned cities along the Irawaddy valley between the 14th to 19th century. Town planning in pre-modern Burma reached its climax during the Konbaung period with cities such as Mandalay. Alaungpaya directed many town planning initiatives. He built many small fortified towns with major defences. One of these, Rangoon, was founded in 1755 as a fortress and sea harbor. The city had an irregular plan with stockades made of teak logs on a ground rampart. Rangoon had six city gates with each gate flanked by massive brick towers with typical merlons with cross-shaped embrasures. The stupa of Shwedagon, Sule and Botataung were located outside the city walls. The city had main roads paved with bricks and drains along the sides.[134]

This period also saw a proliferation of stupas and temples with developments in stucco techniques. Wooden monasteries of this period intricately decorated with wood carvings of the Jataka Tales are one of the more prominent distinctive examples of traditional Burmese architecture that survive to the present day.[130]

Monastic and lay elites around the Konbaung kings, particularly from Bodawpaya's reign, launched a major reformation of Burmese intellectual life and monastic organisation and practice known as the Sudhamma Reformation. It led to, amongst other things, Burma's first proper state histories.[135]

Note: Naungdawgyi was the eldest brother of Hsinbyushin and Bodawpaya who was the grandfather of Bagyidaw who was Mindon's elder uncle. They were known by these names to posterity, although the formal titles at their coronation by custom ran to some length in Pali; Mintayagyi paya (Lord Great King) was the equivalent of Your/His Majesty whereas Hpondawgyi paya (Lord Great Glory) would be used by the royal family.

After the abolition of the monarchy, the title of Royal Householder of the Konbaung dynasty nominally passed to Myat Phaya Lat, Thibaw's second daughter, as the King's eldest daughter renounced her royal titles to be with an Indian commoner.[11]

Thibaw's third daughter Myat Phaya Galay returned to Burma and sought the return of the throne from the British in the 1920s. Her eldest son Taw Phaya Gyi was taken by Imperial Japan during the Second World War for his potential as a puppet king. Japan's efforts failed due to Taw Phaya Gyi's distaste of the Japanese and his assassination in 1948 by Communist insurgents.[136]

After the death of Myat Phaya Lat, her grandson-in-law Taw Phaya became the nominal Royal Householder. Taw Phaya was the son of Myat Phaya Galay, the brother of Taw Phaya Gyi and the husband of Myat Phaya Lat's granddaughter Hteik Su Gyi Phaya.[137] Upon Taw Phaya's death in 2019, it is unclear who serves as the Royal Householder. Soe Win, the eldest son of Taw Phaya Gyi is assumed to be the Royal Householder as there is little public information about Taw Phaya's children.[138]