Un paraíso fiscal es un término, a menudo utilizado de manera peyorativa, para describir un lugar con tasas impositivas muy bajas para inversores no domiciliados , incluso si las tasas oficiales pueden ser más altas. [a] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

En algunas definiciones más antiguas, un paraíso fiscal también ofrece secreto financiero . [b] [6] Sin embargo, mientras que los países con altos niveles de secreto pero también altas tasas de impuestos, más notablemente los Estados Unidos y Alemania en las clasificaciones del Índice de Secreto Financiero (FSI), [c] pueden aparecer en algunas listas de paraísos fiscales, a menudo se los omite de las listas por razones políticas o por falta de conocimiento de la materia. En contraste, los países con niveles más bajos de secreto pero también bajas tasas de impuestos "efectivas", más notablemente Irlanda en las clasificaciones del FSI, aparecen en la mayoría de las § listas de paraísos fiscales. [9] El consenso sobre las tasas impositivas efectivas ha llevado a los académicos a señalar que el término "paraíso fiscal" y " centro financiero offshore " son casi sinónimos. [10] En realidad, muchos centros financieros offshore no tienen prácticas fiscales dañinas y están a la vanguardia entre los centros financieros con respecto a las prácticas AML y la presentación de informes fiscales internacionales.

Los avances de la última década han reducido sustancialmente la capacidad de las personas o corporaciones para utilizar los paraísos fiscales para la evasión fiscal (no pago ilegal de impuestos adeudados). Estos incluyen el fin del secreto bancario en muchas jurisdicciones, incluida Suiza, tras la aprobación de la Ley de Cumplimiento Fiscal de Cuentas Extranjeras de los EE. UU. y la adopción del CRS por la mayoría de los países, incluidos los paraísos fiscales típicos, un acuerdo multilateral de intercambio automático de datos de los contribuyentes, iniciativa de la OCDE . [11] [12] Los países del CRS requieren que los bancos y otras entidades identifiquen la residencia de los titulares de cuentas, los propietarios beneficiarios de las entidades corporativas [13] [14] [15] [16] y registren los saldos de las cuentas anuales y comuniquen dicha información a las agencias tributarias locales, que informarán a las agencias tributarias donde residen los titulares de cuentas o los propietarios beneficiarios de las corporaciones. [17] El CRS pretende terminar con el secreto financiero offshore y la evasión fiscal dando a las agencias tributarias el conocimiento para gravar los ingresos y activos offshore. Sin embargo, las corporaciones muy grandes y complejas, como las multinacionales , aún pueden transferir ganancias a paraísos fiscales corporativos utilizando esquemas intrincados.

Los paraísos fiscales tradicionales, como Jersey , son abiertos en cuanto a las tasas impositivas cero, por lo que tienen pocos tratados fiscales bilaterales . Los paraísos fiscales corporativos modernos tienen tasas impositivas "principales" distintas de cero y altos niveles de cumplimiento de la OCDE , y por lo tanto tienen grandes redes de tratados fiscales bilaterales. Sin embargo, sus herramientas de erosión de la base imponible y traslado de beneficios ("BEPS") permiten a las empresas lograr tasas impositivas "efectivas" más cercanas a cero, no solo en el paraíso sino en todos los países con los que el paraíso tiene tratados fiscales; colocándolos en listas de paraísos fiscales. Según estudios modernos, los 10 principales paraísos fiscales incluyen paraísos centrados en las corporaciones como los Países Bajos, Singapur, Irlanda y el Reino Unido, mientras que Luxemburgo, Hong Kong, las Islas Caimán, Bermudas, las Islas Vírgenes Británicas y Suiza figuran como importantes paraísos fiscales tradicionales y principales paraísos fiscales corporativos. Los paraísos fiscales corporativos a menudo sirven como "conductos" hacia los paraísos fiscales tradicionales. [18] [19] [20]

El uso de paraísos fiscales genera una pérdida de ingresos fiscales para países que no son paraísos fiscales. Las estimaciones de la escala financiera de impuestos evitados varían, pero las más creíbles estiman que oscilan entre 100.000 y 250.000 millones de dólares al año. [21] [22] [23] [24] Además, el capital depositado en paraísos fiscales puede abandonar permanentemente la base imponible (erosión de la base imponible). Las estimaciones del capital depositado en paraísos fiscales también varían: las más creíbles oscilan entre 7 y 10 billones de dólares (hasta el 10% de los activos globales). [25] El daño de los paraísos fiscales tradicionales y corporativos se ha observado particularmente en los países en desarrollo, donde los ingresos fiscales son necesarios para construir infraestructura. [26] [27] [28]

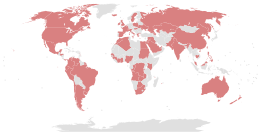

Más del 15% [d] de los países son a veces etiquetados como paraísos fiscales. [4] [9] Los paraísos fiscales son en su mayoría economías exitosas y bien gobernadas, y ser un paraíso ha traído prosperidad. [31] [32] Los 10-15 principales países de PIB per cápita , excluyendo los exportadores de petróleo y gas, son paraísos fiscales. Debido a § El PIB per cápita inflado (debido a los flujos contables BEPS), los paraísos son propensos al sobreapalancamiento (el capital internacional fija incorrectamente el precio artificial de la deuda al PIB). Esto puede conducir a graves ciclos crediticios y/o crisis inmobiliarias/bancarias cuando se fijan de nuevo los precios de los flujos de capital internacionales. El Celtic Tiger de Irlanda y la posterior crisis financiera de 2009-13 son un ejemplo. [33] Jersey es otro. [34] La investigación muestra § Estados Unidos como el mayor beneficiario, y el uso de paraísos fiscales por parte de las corporaciones estadounidenses maximizó los ingresos del tesoro estadounidense. [35]

El enfoque histórico en la lucha contra los paraísos fiscales (por ejemplo, los proyectos de la OCDE y el FMI ) se ha centrado en normas comunes, transparencia e intercambio de datos. [36] El auge de los paraísos fiscales corporativos que cumplen con los requisitos de la OCDE, cuyas herramientas BEPS fueron responsables de la mayoría de los impuestos perdidos, [37] [26] [23] condujo a críticas a este enfoque, frente a los impuestos reales pagados. [38] [39] Las jurisdicciones con impuestos más altos, como Estados Unidos y muchos estados miembros de la Unión Europea, se apartaron del Proyecto BEPS de la OCDE en 2017-18 para introducir regímenes fiscales anti-BEPS, destinados a aumentar los impuestos netos pagados por las corporaciones en los paraísos fiscales corporativos (por ejemplo, la Ley de recortes de impuestos y empleos de los EE. UU. de 2017 ("TCJA"), los regímenes fiscales GILTI-BEAT-FDII y pasar a un sistema fiscal "territorial" híbrido, y el régimen propuesto de impuesto a los servicios digitales de la UE y la base imponible corporativa consolidada común de la UE ). [38]

Si bien ya en la Antigua Grecia se registran zonas de baja tributación, los académicos tributarios identifican lo que conocemos como paraísos fiscales como un fenómeno moderno, [40] [41] y señalan las siguientes fases en su desarrollo:

No existe un consenso establecido sobre una definición específica de lo que constituye un paraíso fiscal. Esta es la conclusión de organizaciones no gubernamentales , como la Tax Justice Network en 2018, [58] de la investigación de 2008 de la Oficina de Responsabilidad Gubernamental de los Estados Unidos , [74] de la investigación de 2015 del Servicio de Investigación del Congreso de los Estados Unidos , [75] de la investigación de 2017 del Parlamento Europeo, [76] y de destacados investigadores académicos sobre paraísos fiscales. [77]

Sin embargo, la cuestión es importante, ya que ser etiquetado como un "paraíso fiscal" tiene consecuencias para un país que busca desarrollarse y comerciar en virtud de tratados fiscales bilaterales. Cuando Irlanda fue incluida en la "lista negra" del miembro del G20 Brasil en 2016, el comercio bilateral disminuyó. [78] [79]

Uno de los primeros artículos importantes sobre los paraísos fiscales [80] fue el artículo Hines-Rice de 1994 de James R. Hines Jr. [54]. Es el artículo más citado sobre investigación de paraísos fiscales [81] , incluso a finales de 2017 [82] , y Hines es el autor más citado sobre investigación de paraísos fiscales [81] . Además de ofrecer información sobre los paraísos fiscales, adoptó la opinión de que la diversidad de países que se convierten en paraísos fiscales era tan grande que las definiciones detalladas eran inadecuadas. Hines simplemente señaló que los paraísos fiscales eran: "un grupo de países con tasas impositivas inusualmente bajas". Hines reafirmó este enfoque en un artículo de 2009 con Dhammika Dharmapala [4] .

En diciembre de 2008, Dharmapala escribió que el proceso de la OCDE había eliminado en gran medida la necesidad de incluir el "secreto bancario" en cualquier definición de paraíso fiscal y que ahora se trataba "en primer lugar y sobre todo, de tasas de impuestos corporativos bajas o nulas", [77] y que esta se ha convertido en la definición general del "diccionario financiero" de un paraíso fiscal. [1] [2] [3]

Hines perfeccionó su definición en 2016 para incorporar la investigación sobre los incentivos para los paraísos fiscales en materia de gobernanza, que es ampliamente aceptada en el léxico académico. [10] [80] [83]

Los paraísos fiscales suelen ser estados pequeños y bien gobernados que imponen tasas impositivas bajas o nulas a los inversores extranjeros.

— James R. Hines Jr. "Empresas multinacionales y paraísos fiscales", The Review of Economics and Statistics (2016) [5]

En abril de 1998, la OCDE elaboró una definición de paraíso fiscal, que se refiere a aquellos países que cumplen "tres de cuatro" criterios. [84] [85] Se elaboró como parte de su iniciativa "Competencia fiscal perjudicial: un problema mundial emergente". [86] En 2000, cuando la OCDE publicó su primera lista de paraísos fiscales, [29] no incluía a ningún país miembro de la OCDE, ya que se consideraba que todos ellos habían participado en el nuevo Foro Mundial sobre Transparencia e Intercambio de Información con Fines Fiscales de la OCDE , y por lo tanto no cumplirían los criterios ii y iii . Como la OCDE nunca ha incluido a ninguno de sus 35 miembros como paraísos fiscales, Irlanda, Luxemburgo, los Países Bajos y Suiza a veces se definen como los "paraísos fiscales de la OCDE". [87]

En 2017, sólo Trinidad y Tobago cumplía la definición de la OCDE de 1998; por lo tanto, esa definición cayó en descrédito. [56] [88]

(†) El cuarto criterio fue retirado tras las objeciones de la nueva administración estadounidense de Bush en 2001, [36] y en el informe de la OCDE de 2002 la definición pasó a ser "dos de tres criterios". [9]

La definición de la OCDE de 1998 es la más frecuentemente invocada por los "paraísos fiscales de la OCDE". [89] Sin embargo, esa definición (como se señaló anteriormente) perdió credibilidad cuando, en 2017, bajo sus parámetros, solo Trinidad y Tobago calificó como paraíso fiscal y desde entonces ha sido ampliamente descartada por los académicos de paraísos fiscales, [77] [83] [45] incluida la investigación del Servicio de Investigación del Congreso de los EE. UU. de 2015 sobre los paraísos fiscales, por ser restrictiva y permitir que los paraísos de baja tributación de Hines (es decir, a los que se aplica el primer criterio) eviten la definición de la OCDE mejorando la cooperación de la OCDE (por lo que el segundo y el tercer criterio no se aplican). [75]

Por lo tanto, la evidencia (aunque indudablemente sea limitada) no sugiere ningún impacto de la iniciativa de la OCDE sobre la actividad en los paraísos fiscales. [...] Por lo tanto, no se puede esperar que la iniciativa de la OCDE tenga un gran impacto en los usos corporativos de los paraísos fiscales, incluso si (o cuando) la iniciativa se implemente plenamente.

— Dhammika Dharmapala , “¿Qué problemas y oportunidades generan los paraísos fiscales?” (diciembre de 2008) [77]

En abril de 2000, el Foro de Estabilidad Financiera (o FSF) definió el concepto relacionado de un centro financiero extraterritorial (o OFC), [90] que el FMI adoptó en junio de 2000, produciendo una lista de 46 OFC . [57] La definición del FSF-FMI se centró en las herramientas BEPS que ofrecen los paraísos, y en la observación de Hines de que los flujos contables de las herramientas BEPS son "desproporcionados" y, por lo tanto, distorsionan las estadísticas económicas del paraíso. La lista del FSF-FMI capturó nuevos paraísos fiscales corporativos, como los Países Bajos, que Hines consideró demasiado pequeños en 1994. [9] En abril de 2007, el FMI utilizó un enfoque más cuantitativo para generar una lista de 22 OFC principales , [47] y en 2018 enumeró los ocho OFC principales que manejan el 85% de todos los flujos. [37] Desde aproximadamente 2010, los académicos tributarios consideraron que los OFC y los paraísos fiscales eran términos sinónimos . [10] [91] [92]

En octubre de 2010, Hines publicó una lista de 52 paraísos fiscales , que había escalado cuantitativamente mediante el análisis de los flujos de inversión corporativa. [30] Los paraísos más grandes de Hines estaban dominados por paraísos fiscales corporativos, que Dharmapala señaló en 2014 representaban la mayor parte de la actividad global de paraísos fiscales según las herramientas BEPS. [93] La lista de Hines de 2010 fue la primera en estimar los diez paraísos fiscales globales más grandes, solo dos de los cuales, Jersey y las Islas Vírgenes Británicas, estaban en la lista de la OCDE de 2000.

En julio de 2017, el grupo CORPNET de la Universidad de Ámsterdam ignoró cualquier definición de paraíso fiscal y se centró en un enfoque puramente cuantitativo, analizando 98 millones de conexiones corporativas globales en la base de datos Orbis . Las listas de CORPNET de los cinco principales OFC conducto y los cinco principales OFC sumideros coincidieron con 9 de los 10 principales paraísos de la lista de Hines de 2010, y solo diferían en el Reino Unido, que solo transformó su código fiscal en 2009-12 . [59] El estudio de CORPNET sobre los OFC conducto y sumideros dividió la comprensión de un paraíso fiscal en dos clasificaciones: [60] [94]

En junio de 2018, el académico fiscal Gabriel Zucman ( et alia ) publicó una investigación que también ignoró cualquier definición de paraíso fiscal, pero estimó el "traslado de beneficios" corporativo (es decir, BEPS ) y la "rentabilidad corporativa mejorada" que Hines y Dharmapala habían observado. [64] Zucman señaló que la investigación de CORPNET subrepresentaba los paraísos asociados con empresas de tecnología estadounidenses, como Irlanda y las Islas Caimán , ya que Google, Facebook y Apple no aparecen en Orbis. [95] Aun así, la lista de Zucman de 2018 de los 10 principales paraísos también coincidió con 9 de los 10 principales paraísos de la lista de Hines de 2010, pero con Irlanda como el mayor paraíso mundial. [65] Estas listas (Hines 2010, CORPNET 2017 y Zucman 2018), y otras, que siguieron un enfoque puramente cuantitativo, mostraron un consenso firme en torno a los mayores paraísos fiscales corporativos.

En octubre de 2009, la Red de Justicia Fiscal introdujo el Índice de Secreto Financiero ("FSI") y el término "jurisdicción de secreto" [58] para destacar cuestiones relacionadas con los países que cumplen con los requisitos de la OCDE y que tienen tasas impositivas elevadas y no aparecen en las listas académicas de paraísos fiscales, pero que tienen problemas de transparencia. El FSI no evalúa las tasas impositivas ni los flujos BEPS en su cálculo, pero a menudo se lo malinterpreta como una definición de paraíso fiscal en los medios financieros [c], en particular cuando incluye a los EE. UU. y Alemania como las principales "jurisdicciones de secreto". [96] [97] [98] Sin embargo, muchos tipos de paraísos fiscales también se clasifican como jurisdicciones de secreto.

Si bien los paraísos fiscales son diversos y variados, los académicos fiscales a veces reconocen tres "agrupaciones" principales de paraísos fiscales cuando analizan la historia de su desarrollo: [40] [41] [51] [50]

Como se analiza en § Historia, el primer centro de paraíso fiscal reconocido fue el triángulo Zúrich-Zug-Liechtenstein creado a mediados de la década de 1920, al que luego se unió Luxemburgo en 1929. [40] La privacidad y el secreto se establecieron como un aspecto importante de los paraísos fiscales europeos. Sin embargo, los paraísos fiscales europeos modernos también incluyen paraísos fiscales centrados en las empresas, que mantienen niveles más altos de transparencia de la OCDE, como los Países Bajos e Irlanda. [f] Los paraísos fiscales europeos actúan como una parte importante de los flujos globales hacia los paraísos fiscales, y tres de los cinco principales OFC de Conduit globales son europeos (es decir, los Países Bajos, Suiza e Irlanda). [60] Cuatro paraísos fiscales relacionados con Europa aparecen en las diversas listas notables de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales, a saber: los Países Bajos, Irlanda, Suiza y Luxemburgo.

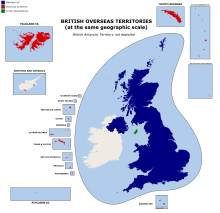

Muchos paraísos fiscales son antiguas o actuales dependencias del Reino Unido y aún utilizan las mismas estructuras jurídicas básicas. [41] Seis paraísos fiscales relacionados con el Imperio Británico aparecen en las listas de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales del §, a saber: paraísos fiscales del Caribe (por ejemplo, Bermudas, las Islas Vírgenes Británicas y las Islas Caimán), paraísos fiscales de las Islas del Canal (por ejemplo, Jersey) y paraísos fiscales asiáticos (por ejemplo, Singapur y Hong Kong). Como se analiza en el § Historia, el Reino Unido creó su primera "empresa no residente" en 1929 y lideró el mercado de centros financieros extraterritoriales de eurodólares después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [40] [41] Desde la reforma de su código tributario corporativo en 2009-2012, el Reino Unido ha resurgido como un importante paraíso fiscal centrado en las corporaciones. [59] Dos de los cinco principales OFC de Conduit globales pertenecen a este grupo (es decir, el Reino Unido y Singapur). [60]

En noviembre de 2009, Michael Foot, ex funcionario del Banco de Inglaterra e inspector bancario de las Bahamas, presentó un informe integrado sobre las tres dependencias de la Corona británica (Guernsey, Isla de Man y Jersey) y los seis territorios de ultramar (Anguila, Bermudas, Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Islas Caimán, Gibraltar, Islas Turcas y Caicos), "para identificar las oportunidades y los desafíos como centros financieros extraterritoriales", para el Tesoro de Su Majestad . [99] [100]

Como se analiza en § Historia, la mayoría de estos paraísos fiscales datan de finales de los años 1960 y copiaron efectivamente las estructuras y servicios de los grupos antes mencionados. [40] La mayoría de estos paraísos fiscales no son miembros de la OCDE, o en el caso de los paraísos fiscales relacionados con el Imperio Británico, no tienen un miembro senior de la OCDE en su núcleo. [40] [51] Algunos han sufrido reveses durante varias iniciativas de la OCDE para frenar los paraísos fiscales (por ejemplo, Vanuatu y Samoa). [40] Sin embargo, otros como Taiwán (para AsiaPAC) y Mauricio (para África), han crecido materialmente en las últimas décadas. [51] Taiwán ha sido descrito como "La Suiza de Asia", con un enfoque en el secreto. [101] Aunque ningún paraíso fiscal relacionado con los mercados emergentes se clasifica en los cinco principales OFC de conducto globales o en ninguna de las § listas de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales, tanto Taiwán como Mauricio se clasifican en los diez principales OFC de sumidero globales. [60]

Hasta la fecha se han elaborado tres tipos principales de listas de paraísos fiscales: [75]

La investigación también destaca indicadores proxy , de los cuales los dos más destacados son:

El aumento posterior a 2010 en las técnicas cuantitativas de identificación de paraísos fiscales ha dado como resultado una lista más estable de los mayores paraísos fiscales. Dharmapala señala que, como los flujos BEPS corporativos dominan la actividad de los paraísos fiscales, estos son en su mayoría paraísos fiscales corporativos. [93] Nueve de los diez principales paraísos fiscales en el estudio de Gabriel Zucman de junio de 2018 también aparecen en las diez listas principales de los otros dos estudios cuantitativos desde 2010. Cuatro de los cinco principales OFC de Conduit están representados; sin embargo, el Reino Unido solo transformó su código tributario en 2009-2012. [59] Los cinco principales OFC de Sink están representados, aunque Jersey solo aparece en la lista de Hines de 2010.

Los estudios reflejan el ascenso de Irlanda y Singapur, dos importantes sedes regionales de algunos de los mayores usuarios de herramientas BEPS, como Apple , Google y Facebook . [106] [107] [108] En el primer trimestre de 2015, Apple completó la mayor acción BEPS de la historia, cuando transfirió US$300 mil millones de propiedad intelectual a Irlanda, lo que el economista premio Nobel Paul Krugman llamó " economía de duendes ". En septiembre de 2018, utilizando los datos de impuestos de repatriación de la TCJA, la NBER enumeró los principales paraísos fiscales como: "Irlanda, Luxemburgo, Países Bajos, Suiza, Singapur, Bermudas y [los] paraísos fiscales del Caribe". [66] [67]

(*) Aparece como uno de los diez principales paraísos fiscales en las tres listas; 9 paraísos fiscales importantes cumplen este criterio, Irlanda, Singapur, Suiza y los Países Bajos (los paraísos fiscales intermediarios) y las Islas Caimán, las Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Luxemburgo, Hong Kong y Bermudas (los paraísos fiscales receptores) .

(†) También aparece como uno de los 5 paraísos fiscales intermediarios (Irlanda, Singapur, Suiza, los Países Bajos y el Reino Unido), en la investigación de CORPNET de 2017; o

(‡) También aparece como uno de los 5 principales paraísos fiscales receptores (Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Luxemburgo, Hong Kong, Jersey, Bermudas), en la investigación de CORPNET de 2017.

(Δ) Identificado en la primera y más grande lista de la OCDE de 2000 de 35 paraísos fiscales (la lista de la OCDE solo contenía a Trinidad y Tobago en 2017). [29] [56]

El consenso más fuerte entre los académicos con respecto a los paraísos fiscales más grandes del mundo es, por lo tanto, el siguiente: Irlanda, Singapur, Suiza y los Países Bajos (los principales OFC conducto), y las Islas Caimán, las Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Luxemburgo, Hong Kong y Bermudas (los principales OFC sumidero), con el Reino Unido (un importante OFC conducto) aún en transformación.

De estos diez paraísos fiscales principales, todos, excepto el Reino Unido y los Países Bajos, figuraban en la lista original de Hines-Rice de 1994. El Reino Unido no era un paraíso fiscal en 1994, y Hines estimó que la tasa impositiva efectiva de los Países Bajos en 1994 era superior al 20%. (Hines identificó a Irlanda como el país con la tasa impositiva efectiva más baja, con un 4%). Cuatro de ellos: Irlanda, Singapur, Suiza (3 de los 5 principales paraísos fiscales de los países de origen) y Hong Kong (uno de los 5 principales paraísos fiscales de los países de destino), figuraban en la subcategoría de los 7 principales paraísos fiscales de la lista de Hines-Rice de 1994 , lo que pone de relieve la falta de progreso en la reducción de los paraísos fiscales. [54]

En términos de indicadores proxy , esta lista, excluyendo a Canadá, contiene los siete países que recibieron más de una inversión fiscal estadounidense desde 1982 (ver aquí ). [105] Además, seis de estos grandes paraísos fiscales están entre los 15 primeros en términos de PIB per cápita , y de los otros cuatro, tres de ellos, los lugares del Caribe, no están incluidos en las tablas de PIB per cápita del FMI y el Banco Mundial.

En un informe conjunto del FMI de junio de 2018 sobre el efecto de los flujos BEPS en los datos económicos mundiales, ocho de los países mencionados anteriormente (excluidos Suiza y el Reino Unido) fueron citados como los principales paraísos fiscales del mundo. [37]

La lista más larga de investigaciones cuantitativas no gubernamentales sobre paraísos fiscales es la del estudio de la Universidad de Ámsterdam CORPNET de julio de 2017 sobre paraísos fiscales de conducto y de sumideros , con 29 (5 paraísos fiscales de conducto y 25 de sumideros). A continuación se enumeran los 20 paraísos fiscales más grandes (5 paraísos fiscales de conducto y 15 de sumideros), que coinciden con otras listas principales, como se indica a continuación:

(*) Aparece como uno de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales en las tres listas cuantitativas, Hines 2010, ITEP 2017 y Zucman 2018 (arriba); los nueve de esos 10 principales paraísos fiscales se enumeran a continuación.

(♣) Aparece en la lista de James Hines de 2010 de 52 paraísos fiscales; 17 de las 20 ubicaciones a continuación están en la lista de James Hines de 2010.

(Δ) Identificado en la lista más grande de la OCDE de 2000 de 35 paraísos fiscales (la lista de la OCDE solo contenía a Trinidad y Tobago en 2017); solo cuatro de las ubicaciones a continuación estuvieron alguna vez en una lista de la OCDE. [29]

(↕) Identificado en la primera lista de la Unión Europea de 2017 de 17 paraísos fiscales; [61] solo una de las ubicaciones a continuación está en la lista de la UE de 2017.

Los Estados soberanos que figuran principalmente como grandes paraísos fiscales corporativos son:

Estados soberanos o regiones autónomas que figuran a la vez como importantes paraísos fiscales corporativos y como importantes paraísos fiscales tradicionales:

Estados soberanos (incluidos los de facto) que figuran principalmente como paraísos fiscales tradicionales (pero que tienen tipos impositivos distintos de cero):

Los estados soberanos o subnacionales que son paraísos fiscales muy tradicionales (es decir, con una tasa impositiva explícita del 0 %) incluyen (lista más completa en la tabla opuesta):

La investigación posterior a 2010 sobre los paraísos fiscales se centra en el análisis cuantitativo (que puede clasificarse) y tiende a ignorar los paraísos fiscales muy pequeños sobre los que los datos son limitados, ya que el paraíso se utiliza para la evasión fiscal individual en lugar de la evasión fiscal corporativa. La última lista amplia y creíble de paraísos fiscales globales sin clasificar es la lista de James Hines de 2010 de 52 paraísos fiscales. Se muestra a continuación, pero se amplió a 55 para incluir los paraísos identificados en el estudio de OFC Conduit and Sink de julio de 2017 que no se consideraron paraísos en 2010, a saber, el Reino Unido, Taiwán y Curazao. La lista de James Hines de 2010 contiene 34 de los 35 paraísos fiscales originales de la OCDE; [29] y en comparación con los § 10 principales paraísos fiscales y § 20 principales paraísos fiscales anteriores, muestran que los procesos de la OCDE se centran en el cumplimiento de los paraísos pequeños.

(†) Identificado como uno de los 5 conductos por CORPNET en 2017; la lista anterior tiene 5 de los 5.

(‡) Identificado como uno de los 24 sumideros más grandes por CORPNET en 2017; la lista anterior tiene 23 de los 24 (falta Guyana).

(↕) Identificado en la primera lista de 2017 de la Unión Europea de 17 paraísos fiscales; la lista anterior contiene 8 de los 17. [61]

(Δ) Identificado en la primera y más grande lista de la OCDE de 2000 de 35 paraísos fiscales (la lista de la OCDE solo contenía a Trinidad y Tobago en 2017); la lista anterior contiene 34 de los 35 (faltan las Islas Vírgenes de los Estados Unidos). [29]

Entidades dedicadas en EE.UU.:

Los principales Estados soberanos que figuran en listas de secreto financiero (por ejemplo, el Índice de Secreto Financiero ), pero no en listas de paraísos fiscales corporativos o paraísos fiscales tradicionales, son:

Ni Estados Unidos ni Alemania han aparecido en ninguna lista de paraísos fiscales elaborada por los principales líderes académicos en investigación sobre paraísos fiscales, a saber, James R. Hines Jr. , Dhammika Dharmapala o Gabriel Zucman . No se conocen casos de empresas extranjeras que hayan ejecutado inversiones fiscales a Estados Unidos o Alemania con fines fiscales, una característica básica de un paraíso fiscal corporativo. [105]

La estimación de la escala financiera de los paraísos fiscales es complicada por su inherente falta de transparencia. [38] Incluso las jurisdicciones que cumplen con los requisitos de transparencia de la OCDE, como Irlanda, Luxemburgo y los Países Bajos, ofrecen herramientas de secreto alternativas (por ejemplo, fideicomisos, QIAIF y ULL ) que pueden usarse para el secreto de los UBO. [137] Por ejemplo, cuando la Comisión Europea descubrió que la tasa impositiva de Apple en Irlanda era del 0,005% , encontraron que Apple había usado ULL irlandeses para evitar la presentación de cuentas públicas irlandesas desde principios de los años 1990. [138]

Además, a veces hay confusión entre las cifras que se centran en la cantidad de impuestos anuales perdidos debido a los paraísos fiscales (que se estima en cientos de miles de millones de dólares) y las cifras que se centran en la cantidad de capital que reside en los paraísos fiscales (que se estima en muchos billones de dólares). [137]

A marzo de 2019 [update], los métodos más creíbles utilizados para estimar la escala financiera han sido: [137]

Las ONG han elaborado muchas otras "estimaciones aproximadas" que son derivados burdos del primer método ("datos bancarios") y que a menudo son criticadas por tomar interpretaciones y conclusiones erróneas de los datos bancarios y financieros globales agregados para producir estimaciones erróneas. [137] [139]

Un estudio notable sobre el efecto financiero fue Price of Offshore: Revisited in 2012–2014, del ex economista jefe de McKinsey & Company, James S. Henry . [140] [141] [142] Henry realizó el estudio para la Tax Justice Network (TJN) y, como parte de su análisis, hizo una crónica de la historia de las estimaciones financieras pasadas de varias organizaciones. [137] [38]

Henry utilizó principalmente datos bancarios globales de varias fuentes regulatorias para estimar que: [141] [142]

La credibilidad de Henry y la profundidad de su análisis hicieron que el informe atrajera la atención internacional. [140] [144] [145] El TJN complementó su informe con otro informe sobre las consecuencias del análisis en términos de desigualdad global y pérdida de ingresos para las economías en desarrollo. [146] El informe fue criticado por un informe de 2013 financiado por Jersey Finance (un grupo de presión para el sector de servicios financieros en Jersey), y escrito por dos académicos estadounidenses, Richard Morriss y Andrew Gordon. [139] En 2014, el TJN emitió un informe en respuesta a estas críticas. [147] [148]

En 2015, el economista fiscal francés Gabriel Zucman publicó La riqueza oculta de las naciones , en la que utilizó datos de cuentas nacionales globales para calcular la cantidad de posiciones netas de activos extranjeros de los países ricos que no se declaran porque se encuentran en paraísos fiscales. Zucman estimó que entre el 8 y el 10% de la riqueza financiera mundial de los hogares, o más de 7,6 billones de dólares estadounidenses, se encontraba en paraísos fiscales. [25] [27] [149] [38]

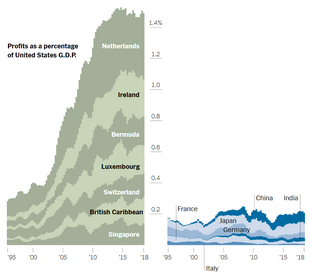

Zucman publicó varios artículos en coautoría sobre el uso de los paraísos fiscales por parte de las corporaciones, titulados "The Missing Profits of Nations" (2016-2018), [21] [22] y "The Exorbitant Tax Privilege" (2018), [66] [67] que mostraban que las corporaciones protegen de impuestos a más de 250 mil millones de dólares por año. Zucman demostró que casi la mitad de ellas son corporaciones estadounidenses, [68] y que fue el motor de cómo las corporaciones estadounidenses acumularon depósitos en efectivo en el extranjero de 1 a 2 billones de dólares desde 2004. [69] El análisis de Zucman (et alia) mostró que las cifras del PIB mundial estaban materialmente distorsionadas por los flujos BEPS multinacionales. [150] [38]

Un estudio de 2022 realizado por Zucman y coautores estimó que el 36% de las ganancias de las empresas multinacionales se trasladan a paraísos fiscales. [151] Si las ganancias se hubieran reasignado a su fuente nacional, "las ganancias nacionales aumentarían alrededor de un 20% en los países de la Unión Europea con impuestos elevados, un 10% en los Estados Unidos y un 5% en los países en desarrollo, mientras que caerían un 55% en los paraísos fiscales". [151]

En 2007, la OCDE estimó que el capital depositado en el extranjero ascendía a entre 5 y 7 billones de dólares, lo que representa aproximadamente el 6-8% del total de las inversiones mundiales bajo gestión. [152] En 2017, como parte del Proyecto BEPS de la OCDE, estimó que entre 100 y 240 mil millones de dólares en ganancias corporativas estaban siendo protegidas de la tributación a través de actividades BEPS llevadas a cabo a través de jurisdicciones de tipo paraíso fiscal. [23] [38]

En 2018, la revista trimestral del FMI Finance & Development publicó una investigación conjunta entre el FMI y académicos tributarios titulada "Piercing the Veil", que estimaba que alrededor de 12 billones de dólares de inversión corporativa global en todo el mundo eran "solo inversiones corporativas fantasma" estructuradas para evitar impuestos corporativos, y se concentraban en ocho lugares importantes. [37] En 2019, el mismo equipo publicó otra investigación titulada "The Rise of Phantom Investments", que estimaba que un alto porcentaje de la inversión extranjera directa (IED) global era "fantasma", y que "las carcasas corporativas vacías en los paraísos fiscales socavan la recaudación de impuestos en las economías avanzadas, de mercados emergentes y en desarrollo". [26] La investigación destacó a Irlanda y estimó que más de dos tercios de la IED de Irlanda era "fantasma". [153] [154]

En varios trabajos de investigación, James R. Hines Jr. demostró que los paraísos fiscales eran, por lo general, naciones pequeñas pero bien gobernadas y que ser un paraíso fiscal había traído consigo una prosperidad significativa. [31] [32] En 2009, Hines y Dharmapala sugirieron que aproximadamente el 15% de los países son paraísos fiscales, pero se preguntaron por qué más países no se habían convertido en paraísos fiscales dada la prosperidad económica observable que podría traer. [4]

Hoy en día hay alrededor de 40 paraísos fiscales importantes en el mundo, pero los considerables beneficios económicos que aparentemente se obtienen al convertirse en un paraíso fiscal plantean la pregunta de por qué no hay más.

— Dhammika Dharmapala , James R. Hines Jr. , ¿Qué países se convierten en paraísos fiscales? (2009) [4]

Hines y Dharmapala concluyeron que la gobernanza era un tema importante para los países más pequeños que intentaban convertirse en paraísos fiscales. Sólo los países con una gobernanza sólida y una legislación en la que las empresas y los inversores extranjeros confiaran podrían convertirse en paraísos fiscales. [4] La visión positiva de Hines y Dharmapala sobre los beneficios financieros de convertirse en un paraíso fiscal, además de ser dos de los principales líderes académicos en la investigación sobre los paraísos fiscales, los puso en un agudo conflicto con las organizaciones no gubernamentales que abogan por la justicia fiscal , como la Red de Justicia Fiscal, que los acusó de promover la evasión fiscal. [155] [156] [157]

Los paraísos fiscales tienen una alta puntuación en términos de PIB per cápita , ya que sus estadísticas económicas "principales" están infladas artificialmente por los flujos BEPS que se suman al PIB del paraíso, pero no son gravables en el paraíso. [37] [158] Como los mayores facilitadores de los flujos BEPS, los paraísos fiscales centrados en las empresas, en particular, conforman la mayoría de las 10-15 principales tablas de PIB per cápita, excluyendo las naciones de petróleo y gas (véase la tabla siguiente). La investigación sobre los paraísos fiscales sugiere que una alta puntuación de PIB per cápita, en ausencia de recursos naturales materiales, es un indicador indirecto importante de un paraíso fiscal. [47] En el centro de la definición del FSF-FMI de un centro financiero extraterritorial se encuentra un país donde los flujos financieros BEPS son desproporcionados con respecto al tamaño de la economía autóctona. [47] La transacción BEPS de la "economía del duende" de Apple en Irlanda en el primer trimestre de 2015 fue un ejemplo dramático, que provocó que Irlanda abandonara sus métricas de PIB y PNB en febrero de 2017, a favor de una nueva métrica, el ingreso nacional bruto modificado o GNI*.

La inflación artificial del PIB puede atraer capital extranjero infravalorado (que utiliza la métrica de deuda/PIB "principal" del refugio), lo que produce fases de mayor crecimiento económico. [32] Sin embargo, el mayor apalancamiento conduce a ciclos crediticios más severos, en particular cuando la naturaleza artificial del PIB está expuesta a los inversores extranjeros. [33] [159]

Notas:

En 2018, el destacado economista de paraísos fiscales, Gabriel Zucman , demostró que la mayoría de las disputas sobre impuestos corporativos se dan entre jurisdicciones con impuestos elevados, y no entre jurisdicciones con impuestos elevados y jurisdicciones con impuestos bajos. [162] La investigación de Zucman (et alia) mostró que las disputas con paraísos fiscales importantes como Irlanda, Luxemburgo y los Países Bajos, en realidad son bastante raras. [64] [163]

Demostramos teórica y empíricamente que, en el actual sistema tributario internacional, las autoridades fiscales de los países con altos impuestos no tienen incentivos para combatir el traslado de beneficios a paraísos fiscales. En cambio, centran sus esfuerzos de aplicación de la ley en reubicar los beneficios contabilizados en otros países con altos impuestos, robándose en la práctica ingresos entre sí. Esta falla de la política puede explicar la persistencia del traslado de beneficios a países con bajos impuestos a pesar de los altos costos que ello implica para los países con altos impuestos.

— Gabriel Zucman , Harvard Kennedy School (mayo de 2018) [164]

Un área controvertida de investigación sobre los paraísos fiscales es la sugerencia de que los paraísos fiscales en realidad promueven el crecimiento económico global al resolver problemas percibidos en los regímenes fiscales de las naciones con impuestos más altos (por ejemplo, el debate anterior sobre el sistema fiscal "mundial" de los EE. UU.). Líderes académicos importantes en la investigación de los paraísos fiscales, como Hines, [165] Dharmapala, [77] y otros, [166] citan evidencia de que, en ciertos casos, los paraísos fiscales parecen promover el crecimiento económico en países con impuestos más altos y pueden respaldar regímenes fiscales híbridos beneficiosos de impuestos más altos sobre la actividad doméstica, pero impuestos más bajos sobre el capital o los ingresos de origen internacional:

No está claro el efecto de los paraísos fiscales sobre el bienestar económico en países con altos impuestos, aunque la disponibilidad de paraísos fiscales parece estimular la actividad económica en países cercanos con altos impuestos.

— James R. Hines Jr. , "Resumen: Paraísos fiscales" (2007) [31]

Los paraísos fiscales cambian la naturaleza de la competencia fiscal entre otros países, permitiéndoles muy posiblemente mantener altas tasas impositivas internas que son efectivamente mitigadas para los inversionistas internacionales móviles cuyas transacciones se canalizan a través de paraísos fiscales. [..] De hecho, los países que se encuentran cerca de paraísos fiscales han exhibido un crecimiento del ingreso real más rápido que aquellos más alejados, posiblemente en parte como resultado de los flujos financieros y sus efectos en el mercado.

— James R. Hines Jr. , “Las islas del tesoro”, pág. 107 (2010) [30]

El artículo más citado sobre la investigación de los centros financieros extraterritoriales ("CFE"), [167] un término estrechamente relacionado con los paraísos fiscales, señaló los aspectos positivos y negativos de los CFE en las economías vecinas con altos impuestos o economías de origen, y marginalmente se pronunció a favor de los CFE. [168]

CONCLUSIÓN: Utilizando muestras tanto bilaterales como multilaterales, encontramos empíricamente que los centros financieros offshore exitosos alientan el mal comportamiento en los países de origen ya que facilitan la evasión fiscal y el lavado de dinero [...] No obstante, los centros financieros offshore creados para facilitar actividades indeseables aún pueden tener consecuencias positivas no deseadas. [...] Concluimos tentativamente que los OFC se caracterizan mejor como "simbiontes".

— Andrew K. Rose, Mark M. Spiegel, "Centros financieros offshore: ¿Parásitos o simbiontes?", The Economic Journal , (septiembre de 2007) [168]

Sin embargo, otros académicos notables en materia tributaria cuestionan firmemente estas opiniones, como el trabajo de Slemrod y Wilson, quienes en su § Important papers on tax havens, etiquetan a los paraísos fiscales como parásitos de las jurisdicciones con regímenes tributarios normales, que pueden dañar sus economías. [169] Además, los grupos de campaña por la justicia fiscal han sido igualmente críticos con Hines y otros en estas opiniones. [156] [157] Una investigación realizada en junio de 2018 por el FMI mostró que gran parte de la inversión extranjera directa ("IED") que provenía de paraísos fiscales hacia países con impuestos más altos, en realidad se había originado en el país con impuestos más altos, [37] y, por ejemplo, que la mayor fuente de IED en el Reino Unido, en realidad era del Reino Unido, pero se invirtió a través de paraísos fiscales. [170]

Es fácil desdibujar los límites con las teorías económicas más controvertidas sobre los efectos de los impuestos corporativos en el crecimiento económico y sobre si deberían existir impuestos corporativos. Otros investigadores que han examinado los paraísos fiscales, como Zucman , destacan la injusticia de los paraísos fiscales y ven los efectos como una pérdida de ingresos para el desarrollo de la sociedad. [171] Sigue siendo un área controvertida con defensores de ambos lados. [172]

Un hallazgo del trabajo de Hines-Rice de 1994 , reafirmado por otros, [166] fue que: las bajas tasas impositivas extranjeras [de los paraísos fiscales] en última instancia mejoran las recaudaciones impositivas de los EE. UU . [54] Hines demostró que, como resultado de no pagar impuestos extranjeros mediante el uso de paraísos fiscales, las multinacionales estadounidenses evitaron acumular créditos impositivos extranjeros que reducirían su obligación tributaria en los EE. UU. Hines volvió a este hallazgo varias veces, y en su trabajo de 2010, "Treasure Islands", donde mostró cómo las multinacionales estadounidenses utilizaron paraísos fiscales y herramientas BEPS para evitar los impuestos japoneses sobre sus inversiones japonesas, señaló que esto estaba siendo confirmado por otra investigación empírica a nivel de empresa. [35] Las observaciones de Hines influirían en la política estadounidense respecto de los paraísos fiscales, incluidas las normas de " marcar la casilla " [h] de 1996, y la hostilidad estadounidense a los intentos de la OCDE de frenar las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda, [i] [36] y por qué, a pesar de la divulgación pública de la evasión fiscal por parte de empresas como Google, Facebook y Apple, con las herramientas BEPS irlandesas, Estados Unidos ha hecho poco para detenerlas. [166]

Las tasas impositivas extranjeras más bajas implican créditos menores por impuestos extranjeros y mayores recaudaciones impositivas finales en Estados Unidos (Hines y Rice, 1994). [54] Dyreng y Lindsey (2009), [35] ofrecen evidencia de que las empresas estadounidenses con filiales extranjeras en ciertos paraísos fiscales pagan impuestos extranjeros más bajos e impuestos estadounidenses más altos que las grandes empresas estadounidenses similares en otros aspectos.

— James R. Hines Jr. , “Las islas del tesoro”, pág. 107 (2010) [30]

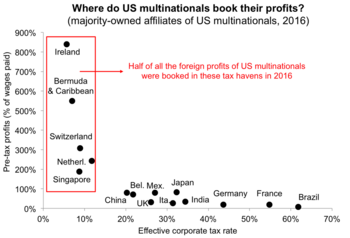

Una investigación realizada entre junio y septiembre de 2018 confirmó que las multinacionales estadounidenses son los mayores usuarios globales de paraísos fiscales y herramientas BEPS. [68] [69] [150]

Las multinacionales estadounidenses utilizan los paraísos fiscales [j] más que las multinacionales de otros países que han mantenido sus regulaciones sobre las corporaciones extranjeras controladas. Ningún otro país de la OCDE que no sea un paraíso fiscal registra una proporción tan alta de ganancias extranjeras contabilizadas en paraísos fiscales como Estados Unidos. [...] Esto sugiere que la mitad de todas las ganancias globales transferidas a paraísos fiscales son transferidas por multinacionales estadounidenses. En cambio, alrededor del 25% se acumula en países de la UE, el 10% en el resto de la OCDE y el 15% en países en desarrollo (Tørsløv et al., 2018).

— Gabriel Zucman , Thomas Wright, “El privilegio fiscal exorbitante”, Documentos de trabajo del NBER (septiembre de 2018). [66] [67]

En 2019, grupos no académicos, como el Consejo de Relaciones Exteriores , se dieron cuenta de la magnitud del uso que hacen las empresas estadounidenses de los paraísos fiscales:

Más de la mitad de los beneficios que las empresas estadounidenses declaran haber obtenido en el extranjero se registran en unos pocos paraísos fiscales de baja tributación, lugares que, por supuesto, no son en realidad el hogar de los clientes, trabajadores y contribuyentes que facilitan la mayor parte de sus negocios. Una corporación multinacional puede canalizar sus ventas globales a través de Irlanda, pagar regalías a su filial holandesa y luego canalizar los ingresos a su filial bermudeña, aprovechando la tasa impositiva corporativa nula de Bermudas.

— Brad Setser , "La estafa global oculta en la ley de reforma fiscal de Trump, al descubierto", The New York Times (febrero de 2019). [173]

Los grupos de justicia fiscal interpretaron la investigación de Hines como una competencia fiscal entre Estados Unidos y naciones con impuestos más altos (es decir, el erario público estadounidense obtiene impuestos excesivos a expensas de otros). La TCJA de 2017 parece respaldar esta opinión, ya que el erario público estadounidense puede imponer un impuesto de repatriación del 15,5 % sobre más de un billón de dólares de ganancias no gravadas en el extranjero acumuladas por multinacionales estadounidenses con herramientas BEPS a partir de ingresos no estadounidenses. Si estas multinacionales estadounidenses hubieran pagado impuestos sobre estas ganancias no estadounidenses en los países en los que se obtuvieron, habría habido una pequeña responsabilidad adicional por impuestos estadounidenses. La investigación de Zucman y Wright (2018) estimó que la mayor parte del beneficio de repatriación de la TCJA fue para los accionistas de las multinacionales estadounidenses, y no para el erario público estadounidense. [66] [k]

Los académicos que estudian los paraísos fiscales atribuyen el apoyo de Washington al uso de los paraísos fiscales por parte de las corporaciones estadounidenses a un compromiso político entre Washington y otras naciones de la OCDE con impuestos más altos, para compensar las deficiencias del sistema fiscal "mundial" estadounidense. [174] [175] Hines había abogado por un cambio a un sistema fiscal "territorial", como el que utilizan la mayoría de las demás naciones, lo que eliminaría la necesidad de las multinacionales estadounidenses de contar con paraísos fiscales. En 2016, Hines, junto con académicos fiscales alemanes, demostró que las multinacionales alemanas hacen poco uso de los paraísos fiscales porque su régimen fiscal, un sistema "territorial", elimina cualquier necesidad de ellos. [176]

La investigación de Hines fue citada por el Consejo de Asesores Económicos ("CEA") al redactar la legislación TCJA en 2017 y abogar por pasar a un marco de sistema tributario "territorial" híbrido. [177] [178]

Hay una serie de conceptos notables en relación con la forma en que las personas y las empresas interactúan con los paraísos fiscales: [45] [179]

Algunos autores sobre los paraísos fiscales los describen como "estados capturados" por su industria financiera offshore, sugiriendo que los requisitos legales, tributarios y de otro tipo de las firmas de servicios profesionales que operan desde el paraíso fiscal reciben mayor prioridad que cualquier necesidad estatal conflictiva. [50] [180] El término se ha utilizado particularmente para paraísos fiscales más pequeños, [181] con ejemplos de Delaware, Seychelles, [182] y Jersey. [183] Sin embargo, el término "estado capturado" también se ha utilizado para centros financieros offshore o paraísos fiscales más grandes y mejor establecidos de la OCDE y la UE. [184] [185] [186] Ronen Palan ha señalado que incluso cuando los paraísos fiscales comenzaron como "centros comerciales", pueden eventualmente ser "capturados" por "poderosas firmas financieras y legales extranjeras que escriben las leyes de estos países que luego explotan". [187] Algunos ejemplos tangibles incluyen la divulgación pública en 2016 de la estructura fiscal del Proyecto Goldcrest de Amazon Inc. , que mostró cuán estrechamente trabajó el Estado de Luxemburgo con Amazon durante más de dos años para ayudarla a evitar impuestos globales. [188] [189] Otros ejemplos incluyen cómo el Gobierno holandés eliminó las disposiciones para prevenir la evasión fiscal corporativa mediante la creación de la herramienta Dutch Sandwich BEPS, que los bufetes de abogados holandeses luego comercializaron a las corporaciones estadounidenses:

En mayo de 2003, Joop Wijn , antiguo ejecutivo de capital de riesgo de ABN Amro Holding NV, se convierte en Secretario de Estado de Asuntos Económicos, y el Wall Street Journal no tarda en informar sobre su gira por Estados Unidos, durante la cual presenta la nueva política fiscal de los Países Bajos a docenas de abogados fiscales, contables y directores de impuestos corporativos estadounidenses. En julio de 2005, decide abolir la disposición que pretendía evitar la evasión fiscal por parte de las empresas estadounidenses, para hacer frente a las críticas de los asesores fiscales.

— Oxfam / De Correspondent , "Cómo los Países Bajos se convirtieron en un paraíso fiscal", 31 de mayo de 2017. [190] [191]

Las resoluciones fiscales preferenciales (PTR) pueden ser utilizadas por una jurisdicción por razones benignas, por ejemplo, incentivos fiscales para fomentar la renovación urbana. Sin embargo, las PTR también pueden utilizarse para proporcionar aspectos de los regímenes fiscales que normalmente se encuentran en los paraísos fiscales tradicionales. [45] Por ejemplo, mientras que los ciudadanos británicos pagan impuestos completos sobre sus activos, los ciudadanos extranjeros que residen legalmente en el Reino Unido no pagan impuestos sobre sus activos globales, siempre que se dejen fuera del Reino Unido; por lo tanto, para un residente extranjero, el Reino Unido se comporta de manera similar a un paraíso fiscal tradicional. [192] Algunos académicos fiscales dicen que las PTR hacen que la distinción con los paraísos fiscales tradicionales "sea una cuestión de grado más que cualquier otra cosa". [45] [193] La OCDE ha hecho de la investigación de las PTR una parte clave de su proyecto a largo plazo de lucha contra las prácticas fiscales nocivas , iniciado en 1998; para 2019, la OCDE había investigado más de 255 PTR. [194] La revelación de Lux Leaks en 2014 reveló 548 PTR emitidos por las autoridades de Luxemburgo a clientes corporativos de PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Cuando la Comisión Europea multó a Apple con 13 mil millones de dólares en 2016 , la multa fiscal más grande de la historia, afirmaron que Apple había recibido "resoluciones fiscales preferenciales" en 1991 y 2007. [138] [195]

Las corporaciones pueden trasladar su sede legal desde una jurisdicción de origen con impuestos más altos a un paraíso fiscal ejecutando una inversión fiscal . Una " inversión fiscal desnuda " es cuando la corporación tenía pocas actividades comerciales previas en la nueva ubicación. La primera inversión fiscal fue la "inversión desnuda" de McDermott International a Panamá en 1983. [55] [53] El Congreso de los EE. UU. prohibió efectivamente las "inversiones desnudas" para las corporaciones estadounidenses al introducir la regulación 7874 del IRS en la Ley de Creación de Empleo Estadounidense de 2004. [ 53] Una " inversión fiscal de fusión " es cuando la corporación supera la regulación 7874 del IRS al fusionarse con una corporación que tiene una "presencia comercial sustancial" en la nueva ubicación. [53] El requisito de una presencia comercial sustancial significaba que las corporaciones estadounidenses solo podían invertir en paraísos fiscales más grandes, y particularmente en paraísos fiscales de la OCDE y de la UE. Un mayor endurecimiento de las regulaciones por parte del Tesoro de Estados Unidos en 2016, así como la reforma fiscal estadounidense TCJA de 2017, redujeron los beneficios fiscales de una corporación estadounidense que invierte en un paraíso fiscal. [53]

Incluso cuando una corporación ejecuta una inversión fiscal a un paraíso fiscal, también necesita trasladar (o despojar de sus ganancias ) sus ganancias no gravadas al nuevo paraíso fiscal. [53] Estas se denominan técnicas de erosión de la base imponible y traslado de beneficios (BEPS). [93] Las corporaciones estadounidenses utilizaron herramientas BEPS notables como el Double Irish con un Dutch Sandwich para acumular reservas de efectivo offshore no gravadas de 1 a 2 billones de dólares en paraísos fiscales como Bermudas (por ejemplo, el Bermuda Black Hole de Apple ) entre 2004 y 2017. [196] Como se analiza en el § Escala financiera, en 2017, la OCDE estimó que las herramientas BEPS protegían de impuestos entre 100.000 y 200.000 millones de dólares en ganancias corporativas anuales; mientras que en 2018, Zucman estimó que la cifra estaba más cerca de los 250.000 millones de dólares anuales. Esto fue a pesar del Proyecto BEPS de la OCDE de 2012-2016. En 2015, Apple ejecutó la mayor transacción BEPS registrada en la historia cuando trasladó 300 mil millones de dólares de su propiedad intelectual a Irlanda, en lo que se denominó una inversión fiscal híbrida.

Las herramientas más importantes de BEPS son las que utilizan la contabilidad de la propiedad intelectual (PI) para trasladar las ganancias entre jurisdicciones. El concepto de que una empresa cargue sus costos de una jurisdicción a sus ganancias en otra jurisdicción (es decir, la fijación de precios de transferencia ) es bien conocido y aceptado. Sin embargo, la PI permite a una empresa "revaluar" sus costos de manera espectacular. Por ejemplo, un importante programa de software podría haber costado 1.000 millones de dólares en salarios y gastos generales. La contabilidad de la PI permite trasladar la propiedad legal del programa a un paraíso fiscal donde puede revaluarse hasta alcanzar un valor de 100.000 millones de dólares, que se convierte en el nuevo precio al que se imputa a las ganancias globales. Esto crea un traslado de todas las ganancias globales de vuelta al paraíso fiscal. La PI ha sido descrita como "el principal vehículo de evasión fiscal corporativa". [197] [198]

Los países tradicionales de ultramar, como las Islas Caimán, las Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Guernsey o Jersey, tienen clara su neutralidad fiscal corporativa. Por ello, tienden a no firmar tratados fiscales bilaterales completos con otras jurisdicciones con impuestos más altos. En cambio, los ingresos provenientes de estructuras de inversión en esas jurisdicciones están sujetos a la retención fiscal completa establecida por la jurisdicción onshore pertinente. Los Territorios Británicos de Ultramar y las Dependencias de la Corona brindan transparencia fiscal completa y presentación automática de informes fiscales a las autoridades fiscales onshore a través de CRS y FACTA.

Otros paraísos fiscales, por ejemplo en Europa o Asia, mantienen tasas impositivas corporativas más altas que no son cero, pero en su lugar ofrecen herramientas BEPS y PTR complejas y confidenciales que acercan la tasa impositiva corporativa "efectiva" a cero; todos ellos ocupan un lugar destacado en las principales jurisdicciones en materia de derecho de propiedad intelectual (véase el gráfico). Estos "paraísos fiscales corporativos" (o CFE de conducto) aumentan aún más la respetabilidad al exigir a las empresas que utilizan sus herramientas BEPS/PTR que mantengan una "presencia sustancial" en el paraíso; esto se denomina impuesto al empleo y puede costar a la empresa alrededor del 2-3% de los ingresos. Sin embargo, estas iniciativas permiten que el paraíso fiscal corporativo mantenga grandes redes de tratados fiscales bilaterales completos, que permiten a las empresas con sede en el paraíso transferir ganancias globales no gravadas de regreso al paraíso (y a los CFE de sumidero, como se muestra arriba). Estos "paraísos fiscales corporativos" niegan rotundamente cualquier asociación con ser un paraíso fiscal y mantienen altos niveles de cumplimiento y transparencia, y muchos están en la lista blanca de la OCDE (y son miembros de la OCDE o de la UE). Muchos de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales son "paraísos fiscales corporativos".

En 2017, el grupo de investigación CORPNET de la Universidad de Ámsterdam publicó los resultados de su análisis de big data de varios años de más de 98 millones de conexiones corporativas globales. CORPNET ignoró cualquier definición previa de paraíso fiscal o cualquier concepto de estructuración legal o fiscal, para seguir en cambio un enfoque puramente cuantitativo. Los resultados de CORPNET dividieron la comprensión de los paraísos fiscales en Sink OFC , que son paraísos fiscales tradicionales a los que las empresas dirigen fondos no gravados, y Conduit OFC , que son las jurisdicciones que crean las estructuras fiscales compatibles con la OCDE que permiten que los fondos no gravados se dirijan desde las jurisdicciones con impuestos más altos a los Sink OFC. A pesar de seguir un enfoque puramente cuantitativo, los 5 principales Conduit OFC y los 5 principales Sink OFC de CORPNET coinciden estrechamente con los otros § 10 principales paraísos fiscales académicos. Los OFC conducto de CORPNET contenían varias jurisdicciones importantes consideradas paraísos fiscales de la OCDE y/o la UE, incluidos los Países Bajos, el Reino Unido, Suiza e Irlanda. [60] [94] [200] Los OFC conducto están fuertemente correlacionados con los "paraísos fiscales corporativos" modernos y los OFC sumideros con los "paraísos fiscales tradicionales".

Además de las estructuras corporativas, los paraísos fiscales también proporcionan envoltorios legales libres de impuestos (o "neutrales desde el punto de vista fiscal") para mantener activos, también conocidos como vehículos de propósito especial (SPV) o empresas de propósito especial (SPC). [50] Estos SPV y SPC no solo están libres de todos los impuestos, aranceles e IVA, sino que están adaptados a los requisitos regulatorios y los requisitos bancarios de segmentos específicos. [50] Por ejemplo, el SPV de la Sección 110 con impuestos cero es un envoltorio importante en el mercado global de titulización. [200] Este SPV ofrece características que incluyen estructuras huérfanas , que se facilitan para respaldar los requisitos de lejanía de quiebra , que no serían apropiados en centros financieros más grandes , ya que podrían dañar la base impositiva local, pero que los bancos necesitan en las titulizaciones. El SPC de las Islas Caimán es una estructura utilizada por los administradores de activos, ya que puede acomodar clases de activos como activos de propiedad intelectual ("PI"), activos de criptomonedas y activos de créditos de carbono; Entre los productos de la competencia se incluyen el QIAIF irlandés y el SICAV de Luxemburgo . [201]

Algunas empresas en paraísos fiscales han sido objeto de la obtención ilegal y divulgación pública o no pública de datos de cuentas de clientes, siendo las más notables:

En 2008, el Servicio Federal de Inteligencia alemán pagó 4,2 millones de euros a Heinrich Kieber, un antiguo archivista de datos informáticos de LGT Treuhand , un banco de Liechtenstein, por una lista de 1.250 datos de cuentas de clientes del banco. [202] Se produjeron investigaciones y detenciones relacionadas con cargos de evasión fiscal ilegal. [203] Las autoridades alemanas compartieron los datos con el IRS estadounidense , y el HMRC británico pagó 100.000 libras esterlinas por los mismos datos. [204] Las autoridades de varios otros países europeos, Australia y Canadá también recibieron los datos. Las autoridades de Liechtenstein protestaron enérgicamente por el caso y emitieron una orden de arresto contra el hombre sospechoso de haber filtrado los datos. [205]

En abril de 2013, el Consorcio Internacional de Periodistas de Investigación (ICIJ) publicó una base de datos de 260 gigabytes con capacidad de búsqueda que contenía 2,5 millones de archivos de clientes de paraísos fiscales filtrados anónimamente al ICIJ y analizados con 112 periodistas en 58 países. [206] [207] La mayoría de los clientes provenían de China continental, Hong Kong, Taiwán, la Federación Rusa y antiguas repúblicas soviéticas; las Islas Vírgenes Británicas fueron identificadas como el paraíso fiscal más importante para los clientes chinos, y Chipre un importante paraíso fiscal para los clientes rusos. [208] Varios nombres destacados estaban contenidos en las filtraciones, entre ellos: el director de campaña de François Hollande , Jean-Jacques Augier ; el ministro de finanzas de Mongolia, Bayartsogt Sangajav; el presidente de Azerbaiyán; la esposa del viceprimer ministro de Rusia; y el político canadiense Anthony Merchant . [209]

En noviembre de 2014, el Consorcio Internacional de Periodistas de Investigación (ICIJ) publicó 28.000 documentos que totalizaban 4,4 gigabytes de información confidencial sobre resoluciones fiscales privadas de Luxemburgo otorgadas a PricewaterhouseCoopers entre 2002 y 2010 en beneficio de sus clientes en Luxemburgo. Esta investigación del ICIJ reveló 548 resoluciones fiscales para más de 340 empresas multinacionales con sede en Luxemburgo. Las revelaciones de LuxLeaks atrajeron la atención internacional y los comentarios sobre los esquemas de evasión fiscal corporativos en Luxemburgo y en otros lugares. Este escándalo contribuyó a la implementación de medidas destinadas a reducir el dumping fiscal y regular los esquemas de evasión fiscal que benefician a las empresas multinacionales. [210] [211]

En febrero de 2015, el periódico francés Le Monde recibió más de 3,3 gigabytes de datos confidenciales de clientes relacionados con un plan de evasión fiscal supuestamente operado con el conocimiento y el estímulo del banco multinacional británico HSBC a través de su filial suiza, HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) . La fuente fue el analista informático francés Hervé Falciani , que proporcionó datos sobre cuentas de más de 100.000 clientes y 20.000 empresas offshore en HSBC en Ginebra; la revelación ha sido calificada como "la mayor filtración en la historia de la banca suiza". Le Monde pidió a 154 periodistas afiliados a 47 medios de comunicación diferentes que procesaran los datos, incluidos The Guardian , Süddeutsche Zeitung y el ICIJ. [212] [213]

En 2015, 11,5 millones de documentos con un total de 2,6 terabytes, que detallaban información financiera y de relaciones entre abogados y clientes de más de 214.488 entidades offshore, algunas de las cuales databan de la década de 1970, que fueron tomados del bufete de abogados panameño Mossack Fonseca , fueron filtrados anómalamente al periodista alemán Bastian Obermayer en Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ). Dada la escala sin precedentes de los datos, SZ trabajó con el ICIJ, así como con periodistas de 107 organizaciones de medios en 80 países que analizaron los documentos. Después de más de un año de análisis, las primeras noticias se publicaron el 3 de abril de 2016. Los documentos nombraban a figuras públicas prominentes de todo el mundo, incluido el primer ministro británico David Cameron y el primer ministro islandés Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson . [214]

En 2017, 13,4 millones de documentos con un total de 1,4 terabytes, que detallaban tanto las actividades personales como las de los principales clientes corporativos del bufete de abogados offshore Appleby , que abarcaban 19 paraísos fiscales, se filtraron a los periodistas alemanes Frederik Obermaier y Bastian Obermayer en Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ). Al igual que con los Papeles de Panamá en 2015, SZ trabajó con el ICIJ y más de 100 organizaciones de medios para procesar los documentos. Contienen los nombres de más de 120.000 personas y empresas, entre ellas Apple, AIG, el príncipe Carlos, la reina Isabel II, el presidente de Colombia Juan Manuel Santos y el entonces secretario de Comercio de Estados Unidos Wilbur Ross. Con un tamaño de 1,4 terabytes, esta es la segunda filtración de datos más grande de la historia, superada solo por los Papeles de Panamá de 2016. [215]

En octubre de 2021, el Consorcio Internacional de Periodistas de Investigación (ICIJ) filtró 11,9 millones de documentos con 2,9 terabytes de datos . La filtración expuso las cuentas secretas en paraísos fiscales de 35 líderes mundiales, incluidos presidentes actuales y anteriores, primeros ministros y jefes de estado, así como más de 100 multimillonarios, celebridades y líderes empresariales.

En un informe de fecha 15 de junio de 2023, [216] el Parlamento de la Unión Europea hizo ciertas admisiones escalofriantes con respecto a la conducta y la publicidad en torno a la filtración de datos de Pandora Papers:

[El Parlamento] Destaca la importancia de defender la libertad de los periodistas de informar sobre cuestiones de interés público sin enfrentarse a la amenaza de costosas acciones legales, incluso cuando reciben documentos, conjuntos de datos u otros materiales confidenciales, secretos o restringidos, independientemente de su origen. (§2)

[El Parlamento] Lamenta la falta de responsabilidad democrática en el proceso de elaboración de la «lista de la UE de países y territorios no cooperadores a efectos fiscales»; recuerda que el Consejo parece guiarse a veces por motivos diplomáticos o políticos en lugar de por evaluaciones objetivas cuando decide trasladar países de la «lista gris» a la «lista negra» y viceversa; subraya que esto socava la credibilidad, la previsibilidad y la utilidad de las listas; pide que se consulte al Parlamento en la preparación de la lista y que se revisen en profundidad los criterios de selección (§78)

[El Parlamento] observa que, a pesar de la aplicación de la legislación europea y nacional sobre la transparencia de la propiedad efectiva, como han informado organizaciones no gubernamentales, la calidad de los datos en algunos registros públicos de la UE requiere mejoras (§60).

Las diversas contramedidas que las jurisdicciones con impuestos más altos han adoptado contra los paraísos fiscales se pueden agrupar en los siguientes tipos:

En 2010, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Cumplimiento Tributario de Cuentas Extranjeras (FATCA), que requiere que las instituciones financieras extranjeras (FFI) de amplio alcance (bancos, corredores de bolsa, fondos de cobertura, fondos de pensiones, compañías de seguros, fideicomisos) informen directamente al Servicio de Impuestos Internos (IRS) de los EE. UU. sobre todos los clientes que sean personas estadounidenses . A partir de enero de 2014, FATCA requiere que las FFI proporcionen informes anuales al IRS sobre el nombre y la dirección de cada cliente estadounidense, así como el saldo de cuenta más grande en el año y los débitos y créditos totales de cualquier cuenta propiedad de una persona estadounidense. [217] Además, FATCA requiere que cualquier empresa extranjera que no cotice en una bolsa de valores o cualquier sociedad extranjera que tenga un 10% de propiedad estadounidense informe al IRS los nombres y el número de identificación fiscal (TIN) de cualquier propietario estadounidense. La FATCA también exige que los ciudadanos estadounidenses y los titulares de tarjetas verdes que tengan activos financieros extranjeros superiores a 50.000 dólares completen un nuevo Formulario 8938 que se presentará junto con la declaración de impuestos 1040 , a partir del año fiscal 2010. [218]

En 2014, la OCDE siguió el ejemplo de FATCA con el Estándar Común de Reporte , un estándar de información para el intercambio automático de información fiscal y financiera a nivel global (que ya sería necesario para que FATCA procese los datos). A partir de 2017, participan en el CRS Australia, Bahamas, Bahréin, Bermudas, Brasil, Islas Vírgenes Británicas, Brunei Darussalam, Canadá, Islas Caimán, Chile, China, Islas Cook, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Israel, Japón, Jersey, Kuwait, Líbano, Macao, Malasia, Mauricio, Mónaco, Nueva Zelanda, Panamá, Qatar, Rusia, Arabia Saudita, Singapur, Suiza, Turquía, Emiratos Árabes Unidos y Uruguay. [219]

En la cumbre del G20 celebrada en Londres el 2 de abril de 2009, los países del G20 acordaron definir una lista negra de paraísos fiscales, que se segmentaría según un sistema de cuatro niveles, en función del cumplimiento de una "norma fiscal acordada internacionalmente". [220] La lista al 2 de abril de 2009 se puede consultar en el sitio web de la OCDE. [221] Los cuatro niveles eran:

Los países que se encontraban en la última categoría fueron clasificados inicialmente como "paraísos fiscales no cooperativos". Uruguay fue clasificado inicialmente como no cooperativo. Sin embargo, tras la apelación, la OCDE declaró que sí cumplía las normas de transparencia fiscal y, por lo tanto, lo ascendió a una categoría superior. Filipinas tomó medidas para retirarse de la lista negra y el Primer Ministro de Malasia, Najib Razak, había sugerido anteriormente que Malasia no debería estar en la última categoría. [222]

En abril de 2009 la OCDE anunció a través de su director, Ángel Gurría, que Costa Rica, Malasia, Filipinas y Uruguay habían sido eliminados de la lista negra después de haber asumido "un compromiso pleno de intercambiar información según los estándares de la OCDE". [223] A pesar de los llamados del ex presidente francés Nicolas Sarkozy para que Hong Kong y Macao se incluyeran en la lista por separado de China, todavía no se los ha incluido de forma independiente, aunque se espera que se agreguen en una fecha posterior. [220]

La respuesta del gobierno a la ofensiva ha sido en general de apoyo, aunque no universal. [224] El Primer Ministro de Luxemburgo, Jean-Claude Juncker, ha criticado la lista, afirmando que "no tiene credibilidad", por no incluir varios estados de los EE.UU. que proporcionan infraestructura de constitución que son indistinguibles de los aspectos de los paraísos fiscales puros a los que se opone el G20. [225] En 2012, 89 países han implementado reformas suficientes para ser incluidos en la lista blanca de la OCDE. [226]

En diciembre de 2017, la Comisión Europea adoptó una "lista negra" de territorios para fomentar el cumplimiento y la cooperación: Samoa Americana , Bahréin , Barbados , Granada , Guam , Corea del Sur , Macao , Islas Marshall , Mongolia , Namibia , Palau , Panamá , Santa Lucía , Samoa , Trinidad y Tobago , Túnez , Emiratos Árabes Unidos . [61] Además, la Comisión elaboró una "lista gris" de 47 jurisdicciones que ya se habían comprometido a cooperar con la UE para cambiar sus normas sobre transparencia y cooperación fiscal. [227] Solo uno de los 17 paraísos fiscales de la UE incluidos en la lista negra, a saber, Samoa, estaba en el § Los 20 principales paraísos fiscales anterior. Las listas de la UE no incluían ninguna jurisdicción de la OCDE o de la UE, ni ninguno de los § Los 10 principales paraísos fiscales. [62] [63] [228] [229] Unas semanas después, en enero de 2018, el Comisario de Fiscalidad de la UE , Pierre Moscovici , llamó a Irlanda y los Países Bajos "agujeros negros fiscales". [230] [231] Después de solo unos meses, la UE redujo aún más la lista negra, [232] y para noviembre de 2018, contenía solo cinco jurisdicciones: Samoa Americana, Guam, Samoa, Trinidad y Tobago y las Islas Vírgenes de los Estados Unidos. [233] Sin embargo, en marzo de 2019, la lista negra de la UE se amplió a 15 jurisdicciones, incluidas Bermudas, uno de los 10 principales paraísos fiscales y el quinto mayor sumidero de fondos de financiación extraterritorial . [234]

El 27 de marzo de 2019, el Parlamento Europeo votó por 505 votos a favor y 63 en contra la aceptación de un nuevo informe que comparaba a Luxemburgo , Malta , Irlanda , los Países Bajos y Chipre con "presentar rasgos de paraíso fiscal y facilitar la planificación fiscal agresiva". [71] [235] Sin embargo, a pesar de esta votación, la Comisión Europea no está obligada a incluir estas jurisdicciones de la UE en la lista negra. [70]

Desde principios de los años 2000, Portugal ha adoptado una lista específica de jurisdicciones consideradas paraísos fiscales por el Gobierno, a la que se asocian un conjunto de sanciones fiscales para los contribuyentes residentes en Portugal. No obstante, la lista ha sido criticada [236] por no ser objetiva ni racional desde un punto de vista económico.

Para evitar inversiones fiscales flagrantes de corporaciones estadounidenses a paraísos fiscales principalmente de tipo caribeño (por ejemplo, Bermudas y las Islas Caimán), el Congreso de Estados Unidos agregó la Regulación 7874 al código del IRS con la aprobación de la Ley de Creación de Empleo Estadounidense de 2004. Si bien la legislación fue efectiva, se requirieron más regulaciones del Tesoro de Estados Unidos en 2014-2016 para evitar las inversiones fiscales de fusión mucho más grandes , que culminaron con el bloqueo efectivo de la propuesta de 2016 de 160 mil millones de dólares de Pfizer-Allergan en Irlanda. Desde estos cambios, no ha habido más inversiones fiscales materiales en Estados Unidos.

En la cumbre del G20 de Los Cabos de 2012 , se acordó que la OCDE emprendiera un proyecto para combatir las actividades de erosión de la base imponible y traslado de beneficios (BEPS) por parte de las empresas. Un Instrumento Multilateral BEPS de la OCDE , que consta de "15 acciones" diseñadas para implementarse a nivel nacional y a través de disposiciones de tratados fiscales bilaterales, se acordó en la cumbre del G20 de Antalya de 2015. El Instrumento Multilateral BEPS de la OCDE ("MLI"), fue adoptado el 24 de noviembre de 2016 y desde entonces ha sido firmado por más de 78 jurisdicciones; entró en vigor en julio de 2018. El MLI ha sido criticado por "diluir" varias de sus iniciativas propuestas, incluido el informe país por país ("CbCr"), y por proporcionar varias excepciones a las que se acogieron varios paraísos fiscales de la OCDE y la UE. Estados Unidos no firmó el MLI.

El Double Irish fue la mayor herramienta BEPS de la historia que, en 2015, estaba protegiendo de los impuestos estadounidenses más de 100.000 millones de dólares en beneficios corporativos, en su mayoría estadounidenses. Cuando la Comisión Europea multó a Apple con 13.000 millones de euros por utilizar una estructura híbrida ilegal de Double Irish , su informe señaló que Apple había estado utilizando la estructura al menos desde 1991. [237] Varias investigaciones del Senado y del Congreso en Washington citaron el conocimiento público del Double Irish desde 2000 en adelante. Sin embargo, no fueron los EE. UU. quienes finalmente obligaron a Irlanda a cerrar la estructura en 2015, sino la Comisión Europea; [238] y a los usuarios existentes se les dio hasta 2020 para encontrar acuerdos alternativos, dos de los cuales (por ejemplo, el acuerdo de malta pura ) ya estaban en funcionamiento. [239] [240] La falta de acción de los EE. UU., similar a su posición con el MLI de la OCDE (arriba), se ha atribuido a los EE. UU. como el mayor usuario y beneficiario de los paraísos fiscales. Sin embargo, algunos comentaristas señalan que la § Reforma fundamental del código tributario corporativo de los EE. UU. por la TCJA de 2017 puede cambiar esto. [241]

Después de perder 22 inversiones fiscales entre 2007 y 2010, la mayoría a manos de Irlanda, el Reino Unido decidió reformar completamente su código tributario corporativo. [242] Entre 2009 y 2012, el Reino Unido redujo su tasa impositiva corporativa principal del 28% al 20% (y finalmente al 19%), cambió el código tributario corporativo británico de un "sistema tributario mundial" a un "sistema tributario territorial", y creó nuevas herramientas BEPS basadas en propiedad intelectual, incluida una caja de patentes de bajos impuestos . [242] En 2014, The Wall Street Journal informó que "en los acuerdos de inversión fiscal de EE. UU., el Reino Unido ahora es un ganador". [243] En una presentación de 2015, HMRC mostró que muchas de las inversiones británicas pendientes del período 2007 a 2010 habían regresado al Reino Unido como resultado de las reformas fiscales (la mayoría del resto había entrado en transacciones posteriores y no podía regresar, incluido Shire ). [244]

Estados Unidos siguió una reforma muy similar a la del Reino Unido con la aprobación de la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de 2017 (TCJA), que redujo la tasa impositiva corporativa estadounidense del 35% al 21%, cambió el código impositivo corporativo estadounidense de un "sistema impositivo mundial" a un "sistema impositivo territorial" híbrido, y creó nuevas herramientas BEPS basadas en la propiedad intelectual, como el impuesto FDII, así como otras herramientas anti-BEPS como el impuesto BEAT. [245] [246] Al defender la TCJA, el Consejo de Asesores Económicos del Presidente (CEA) se basó en gran medida en el trabajo del académico James R. Hines Jr. sobre el uso corporativo estadounidense de los paraísos fiscales y las probables respuestas de las corporaciones estadounidenses a la TCJA. [82] Desde la TCJA, Pfizer ha guiado las tasas impositivas agregadas globales que son muy similares a lo que esperaban en su inversión abortada de 2016 con Allergan plc en Irlanda.