Irán tiene sitios de investigación, dos minas de uranio , un reactor de investigación e instalaciones de procesamiento de uranio que incluyen tres plantas de enriquecimiento de uranio conocidas . [1]

El programa nuclear iraní, que comenzó en la década de 1950 con el apoyo de los Estados Unidos en el marco del programa Átomos para la Paz , se orientó a la exploración científica con fines pacíficos. En 1970, Irán ratificó el Tratado de No Proliferación Nuclear (TNP), sometiendo sus actividades nucleares a las inspecciones del OIEA . Después de la Revolución iraní de 1979 , cesó la cooperación y el Irán continuó con su programa nuclear de manera clandestina.

El OIEA inició una investigación luego de que las declaraciones del Consejo Nacional de Resistencia de Irán en 2002 revelaran actividades nucleares iraníes no declaradas. [2] [3] En 2006, el incumplimiento de Irán con sus obligaciones en virtud del TNP llevó al Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas a exigir a Irán que suspendiera sus programas. En 2007, la Estimación Nacional de Inteligencia de los Estados Unidos (NIE) declaró que Irán detuvo un supuesto programa activo de armas nucleares en 2003. [4] En noviembre de 2011, el OIEA informó de pruebas creíbles de que Irán había estado realizando experimentos destinados a diseñar una bomba nuclear, y que la investigación podría haber continuado a menor escala después de ese momento. [5] [6] El 1 de mayo de 2018, el OIEA reiteró su informe de 2015, diciendo que no había encontrado pruebas creíbles de actividad de armas nucleares después de 2009. [7] [8] [9]

El reactor Bushehr I, en funcionamiento desde septiembre de 2011, marcó el ingreso de Irán al mercado de la energía nuclear con la asistencia de Rusia. Esto se convirtió en un hito importante para que Rosatom se convirtiera en el mayor actor en el mercado mundial de la energía nuclear. [10] Se prevé que alcance su capacidad máxima a fines de 2012; Irán también ha comenzado a construir una nueva planta nuclear Darkhovin de 300 MW y ha expresado planes para construir más plantas nucleares de tamaño mediano y minas de uranio en el futuro.

A pesar del Plan de Acción Integral Conjunto (PAIC) de 2015 destinado a abordar las preocupaciones nucleares de Irán, la retirada de Estados Unidos en 2018 provocó nuevas sanciones, lo que afectó a las relaciones diplomáticas. El OIEA certificó el cumplimiento de Irán hasta 2019, pero los incumplimientos posteriores tensaron el acuerdo. [11] [12] En un informe del OIEA de 2020, se dijo que Irán había incumplido el PAIC y se enfrentó a las críticas de los signatarios. [13] [14] En 2021, Irán se enfrentó al escrutinio por su afirmación de que el programa era exclusivamente para fines pacíficos, especialmente con referencias al crecimiento de satélites, misiles y armas nucleares. [15] En 2022, el director de la Organización de Energía Atómica de Irán, Mohammad Eslami, anunció un plan estratégico para 10 GWe de generación de electricidad nuclear. [16] En octubre de 2023, un informe del OIEA estimó que Irán había aumentado sus reservas de uranio 22 veces por encima del límite del Plan de Acción Integral Conjunto (PAIC) acordado en 2015. [17]

El programa nuclear de Irán se inició en la década de 1950 con la ayuda de los Estados Unidos. [18] El 5 de marzo de 1957, se anunció un "acuerdo propuesto para la cooperación en la investigación de los usos pacíficos de la energía atómica" en el marco del programa Átomos para la Paz de la administración de Eisenhower . [19]

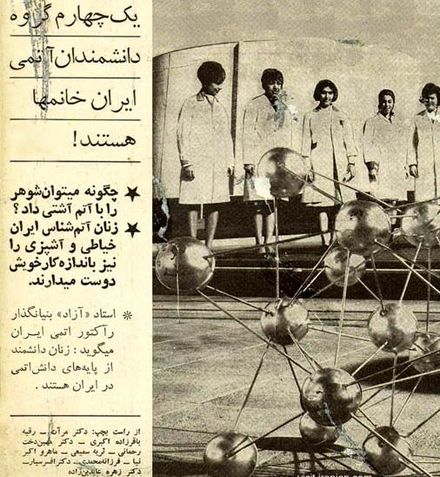

En 1967 se creó el Centro de Investigación Nuclear de Teherán (TNRC), dirigido por la Organización de Energía Atómica de Irán (AEOI). El TNRC estaba equipado con un reactor de investigación nuclear de 5 megavatios suministrado por la empresa estadounidense American Machine and Foundry , que funcionaba con uranio altamente enriquecido . [20] [21]

Irán firmó el Tratado de No Proliferación Nuclear (TNP) en 1968 y lo ratificó en 1970, sujetando su programa nuclear a la verificación del OIEA.

Un instituto de ciencias nucleares de la Organización del Tratado Central [22] fue trasladado de Bagdad a Teherán después de que Irak abandonara la CENTO.

La participación de los gobiernos de Estados Unidos y Europa occidental en el programa nuclear de Irán continuó hasta la Revolución iraní de 1979 que derrocó al último Sha de Irán . [23] Después de la Revolución, la mayor parte de la cooperación nuclear internacional con Irán se interrumpió. En 1981, los funcionarios iraníes concluyeron que el desarrollo nuclear del país debía continuar. Se llevaron a cabo negociaciones con Francia a fines de la década de 1980 y con Argentina a principios de la de 1990, y se alcanzaron acuerdos. En la década de 1990, Rusia formó una organización de investigación conjunta con Irán, proporcionando a Irán expertos nucleares rusos e información técnica. [10]

El Sha aprobó planes para construir hasta 23 centrales nucleares para el año 2000. [24] En marzo de 1974, el Sha imaginó un momento en el que el suministro mundial de petróleo se agotaría y declaró: "El petróleo es un material noble, demasiado valioso para quemarlo... Prevemos producir, lo antes posible, 23.000 megavatios de electricidad utilizando plantas nucleares". [25]

Las empresas estadounidenses y europeas se apresuraron a hacer negocios en Irán. [26] Bushehr , la primera planta, suministraría energía a la ciudad de Shiraz . En 1975, la firma alemana Kraftwerk Union AG, una empresa conjunta de Siemens AG y AEG , firmó un contrato por valor de entre 4.000 y 6.000 millones de dólares para construir la planta de reactor de agua a presión . La construcción de los dos reactores de 1.196 MWe debía haberse completado en 1981.

En 1975, el 10 por ciento de las acciones de Eurodif que poseía Suecia pasó a manos de Irán. La filial francesa Cogéma y el gobierno iraní crearon la empresa Sofidif ( Société franco–iranienne pour l'enrichissement de l'uranium par diffusion gazeuse ) con el 60 y el 40 por ciento de las acciones, respectivamente. A su vez, Sofidif adquirió una participación del 25 por ciento en Eurodif, lo que dio a Irán su participación del 10 por ciento en Eurodif. El Sha prestó 1.000 millones de dólares (y otros 180 millones de dólares en 1977) para la construcción de la fábrica de Eurodif, con el fin de tener derecho a comprar el 10 por ciento de la producción de la planta.

En 1976, el presidente estadounidense Gerald Ford firmó una directiva que ofrecía a Irán la oportunidad de comprar y operar una planta de reprocesamiento construida en Estados Unidos para extraer plutonio del combustible de los reactores. [27] El documento de estrategia de Ford decía que la "introducción de la energía nuclear satisfará las crecientes necesidades de la economía de Irán y liberará las reservas de petróleo restantes para la exportación o la conversión en petroquímicos ".

Una evaluación de la CIA sobre la proliferación de armas nucleares en 1974 afirmaba: "Si [el Sha] está vivo a mediados de los años 1980... y si otros países [en particular la India] han seguido adelante con el desarrollo de armas, no tenemos dudas de que Irán seguirá su ejemplo". [28]

Tras la Revolución de 1979 , se interrumpió la mayor parte de la cooperación nuclear internacional con Irán. Kraftwerk Union detuvo el trabajo en el proyecto Bushehr en enero de 1979, con un reactor completado al 50 por ciento y el otro al 85 por ciento, y se retiró completamente del proyecto en julio de 1979. La compañía dijo que basaron su acción en el impago de Irán de 450 millones de dólares en pagos atrasados, [29] mientras que otras fuentes afirman que se debió a la presión estadounidense. [30] [31] Estados Unidos también cortó el suministro de combustible altamente enriquecido para el Centro de Investigación Nuclear de Teherán , lo que lo obligó a cerrar durante varios años. Eurodif también dejó de suministrar uranio enriquecido a Irán. [30] [32] Irán argumentó más tarde que estas experiencias indican que las instalaciones y los suministros de combustible extranjeros son una fuente poco confiable de suministro de combustible nuclear. [30] [33]

En 1981, los funcionarios gubernamentales iraníes concluyeron que el desarrollo nuclear del país debía continuar. Los informes al OIEA incluían que un sitio en el Centro de Tecnología Nuclear de Isfahán (ENTEC) actuaría "como centro para la transferencia y el desarrollo de tecnología nuclear, así como para contribuir a la formación de la experiencia local y la mano de obra necesaria para sostener un programa muy ambicioso en el campo de la tecnología de reactores nucleares de energía y la tecnología del ciclo del combustible". El OIEA también fue informado sobre el departamento de materiales de Entec, que era responsable de la fabricación de pastillas de UO2 , y el departamento químico, cuyo objetivo era la conversión de U3O8 en UO de grado nuclear .2. [34]

En 1983, funcionarios del OIEA ayudaron a Irán en los aspectos químicos de la fabricación de combustible, ingeniería química y aspectos de diseño de plantas piloto para la conversión de uranio, corrosión de materiales nucleares, fabricación de combustible para LWR y desarrollo de plantas piloto para la producción de UO de grado nuclear.

2. [34] Sin embargo, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos "intervino directamente" para desalentar la asistencia del OIEA en materia de UO.

2y la producción de UF6 . [35] Un ex funcionario estadounidense dijo que "lo detuvimos de inmediato". Irán estableció más tarde una cooperación bilateral sobre cuestiones relacionadas con el ciclo del combustible con China, pero China también acordó abandonar la mayor parte del comercio nuclear pendiente con Irán, incluida la construcción del UF6.

6planta, debido a la presión de EE.UU. [34]

En abril de 1984, el BND filtró un informe según el cual Irán podría tener una bomba nuclear en dos años con uranio paquistaní; este fue el primer informe público de inteligencia occidental sobre un programa de armas nucleares posrevolucionario en Irán. [36] Más tarde ese año, el líder de la minoría del Senado de los EE. UU., Alan Cranston, afirmó que Irán estaba a siete años de poder construir su propia arma nuclear. [37]

Durante la guerra entre Irán e Irak , los dos reactores de Bushehr resultaron dañados por múltiples ataques aéreos iraquíes y el trabajo en el programa nuclear se paralizó. Irán notificó las explosiones al Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica y se quejó de la inacción internacional y del uso de misiles de fabricación francesa en el ataque. [38] [39] A finales de 2015, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani reveló que Irán consideró la posibilidad de desarrollar armas de destrucción masiva durante la guerra contra Irak. [40]

En 1985, Irán empezó a presionar a Francia para que recuperase su deuda con la inversión de Eurodif y le entregase uranio enriquecido. A partir de la primavera de 1985, se tomaron rehenes franceses en el Líbano; en 1986, se perpetraron atentados terroristas en París y fue asesinado el director de Eurodif , Georges Besse . En su investigación La République atomique, France-Iran le pacte nucléaire , David Carr-Brown y Dominique Lorentz señalaron la responsabilidad de los servicios de inteligencia iraníes. Sin embargo, más tarde se comprobó que el asesinato fue cometido por el grupo terrorista de izquierdas Action directe . El 6 de mayo de 1988, el primer ministro francés, Jacques Chirac, firmó un acuerdo con Irán: Francia aceptaba a Irán como accionista de Eurodif y le entregaba uranio enriquecido "sin restricciones".

En 1987-88, la Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica de Argentina firmó un acuerdo con Irán para ayudar a convertir el reactor de combustible HEU a uranio poco enriquecido al 19,75 por ciento , y para suministrar este último combustible a Irán. [41] Según un informe argentino de 2006, durante finales de la década de 1980 y principios de la de 1990, Estados Unidos presionó a Argentina para que terminara su cooperación nuclear con Irán, y desde principios de 1992 hasta 1994 se llevaron a cabo negociaciones entre Argentina e Irán con el objetivo de restablecer los tres acuerdos hechos en 1987-88. [42] Algunos han vinculado ataques como el ataque de 1992 a la embajada de Israel en Buenos Aires y el atentado a la AMIA como parte de una campaña iraní para presionar a Argentina para que honrara los acuerdos. [43] [44] El uranio fue entregado en 1993. [45]

Desde principios de los años 1990, Rusia formó una organización de investigación conjunta con Irán llamada Persépolis que proporcionaba a Irán expertos nucleares rusos, así como información técnica. Cinco instituciones rusas, incluida Roscosmos , ayudaron a Teherán a mejorar sus misiles. El intercambio de información técnica con Irán fue aprobado personalmente por el director del SVR, Trubnikov. [46] El presidente Boris Yeltsin tenía una "política de dos vías" que ofrecía tecnología nuclear comercial a Irán y discutía los temas con Washington. [47]

En 1991, Francia reembolsó más de 1.600 millones de dólares, mientras que Irán siguió siendo accionista de Eurodif a través de Sofidif . Sin embargo, Irán se abstuvo de solicitar el uranio producido. [48] [49]

En 1992, Irán invitó a los inspectores del OIEA a visitar todos los sitios e instalaciones que les pidieron. El Director General Blix informó que todas las actividades observadas eran compatibles con el uso pacífico de la energía atómica. [50] [51] Las visitas del OIEA incluyeron instalaciones no declaradas y el naciente proyecto de extracción de uranio de Irán en Saghand . Ese mismo año, funcionarios argentinos revelaron (bajo presión de los EE. UU.) que su país había cancelado una venta a Irán de equipo nuclear civil por valor de 18 millones de dólares. [52]

En 1995, Irán firmó un contrato con Rosatom para reanudar los trabajos en la planta de Bushehr, parcialmente completada, instalando en el edificio Bushehr I existente un reactor de agua presurizada VVER -1000 de 915 MWe .

En 1996, Estados Unidos convenció a China de que se retirara de un contrato para construir una planta de conversión de uranio. Sin embargo, los chinos proporcionaron planos de la instalación a los iraníes, quienes informaron al OIEA de que seguirían trabajando en el programa; el director del OIEA, Mohamed El Baradei, incluso visitó el lugar de construcción. [53]

En 2002, el Consejo Nacional de Resistencia de Irán (NCRI) expuso la existencia de una instalación de enriquecimiento de uranio no revelada en Natanz , lo que generó preocupaciones emergentes sobre el programa nuclear de Irán. [54] [55] En 2003, después de que el gobierno iraní reconoció formalmente las instalaciones, la Agencia de Energía Atómica las inspeccionó, encontrando que tenían un programa nuclear más avanzado de lo que había sido previamente anticipado por la inteligencia estadounidense. [56] Ese mismo año, el Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica (OIEA) informó por primera vez que Irán no había declarado actividades sensibles de enriquecimiento y reprocesamiento. [3] El enriquecimiento puede usarse para producir uranio para combustible de reactor o (a niveles de enriquecimiento más altos) para armas. [57] Irán dice que su programa nuclear es pacífico, [58] y luego había enriquecido uranio a menos del 5 por ciento, consistente con el combustible para una planta de energía nuclear civil. [59] Irán también afirmó que se vio obligado a recurrir al secreto después de que la presión estadounidense causara que varios de sus contratos nucleares con gobiernos extranjeros fracasaran. [60] Después de que la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA informara al Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU sobre el incumplimiento por parte de Irán de su acuerdo de salvaguardias , el Consejo exigió que Irán suspendiera sus actividades de enriquecimiento nuclear [61] mientras que el presidente iraní Mahmoud Ahmadinejad ha argumentado que las sanciones son "ilegales", impuestas por "potencias arrogantes", y que Irán ha decidido continuar con la supervisión de su autodenominado programa nuclear pacífico a través de "su vía legal apropiada", el Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica. [62] El descubrimiento inicial de la instalación de enriquecimiento en Natanz, así como la negativa de Irán a cooperar plenamente con el OIEA, aumentaron las tensiones entre Irán y las potencias occidentales. [63]

Tras las acusaciones públicas sobre las actividades nucleares no declaradas de Irán, el OIEA inició una investigación que concluyó en noviembre de 2003 que Irán había incumplido sistemáticamente sus obligaciones en virtud de su acuerdo de salvaguardias del TNP de informar sobre esas actividades al OIEA, aunque tampoco informó de ninguna prueba de vínculos con un programa de armas nucleares. La Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA retrasó la constatación formal de incumplimiento hasta septiembre de 2005, e informó de ello al Consejo de Seguridad en febrero de 2006. Después de que la Junta de Gobernadores informara al Consejo de Seguridad sobre el incumplimiento de Irán de su acuerdo de salvaguardias, el Consejo exigió que Irán suspendiera sus programas de enriquecimiento. El Consejo impuso sanciones después de que Irán se negara a hacerlo. Un informe del Congreso de Estados Unidos de mayo de 2009 sugería que "Estados Unidos, y más tarde los europeos, argumentaron que el engaño de Irán significaba que debía renunciar a su derecho a enriquecer uranio, una posición que probablemente se negociaría en las conversaciones con Irán". [64]

A cambio de suspender su programa de enriquecimiento, se le ofreció a Irán "un acuerdo integral a largo plazo que permitiría el desarrollo de relaciones y cooperación con Irán basadas en el respeto mutuo y el establecimiento de la confianza internacional en la naturaleza exclusivamente pacífica del programa nuclear iraní". [65] Sin embargo, Irán se ha negado sistemáticamente a renunciar a su programa de enriquecimiento, argumentando que el programa es necesario para su seguridad energética, que esos "acuerdos a largo plazo" son inherentemente poco fiables y lo privarían de su derecho inalienable a la tecnología nuclear pacífica. En junio de 2009, inmediatamente después de las controvertidas elecciones presidenciales iraníes , Irán aceptó inicialmente un acuerdo para renunciar a su arsenal de uranio poco enriquecido a cambio de combustible para un reactor de investigación médica, pero luego se echó atrás del acuerdo. [66] Actualmente, trece estados poseen instalaciones operativas de enriquecimiento o reprocesamiento, [67] y varios otros han expresado interés en desarrollar programas de enriquecimiento autóctonos. [68]

Para hacer frente a las preocupaciones de que su programa de enriquecimiento pueda ser desviado hacia usos no pacíficos, [69] Irán ofreció imponer restricciones adicionales a su programa de enriquecimiento, incluyendo, por ejemplo, la ratificación del Protocolo Adicional para permitir inspecciones más estrictas por parte del Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica, el funcionamiento de la instalación de enriquecimiento de uranio en Natanz como un centro de combustible multinacional con la participación de representantes extranjeros, la renuncia al reprocesamiento de plutonio y la fabricación inmediata de todo el uranio enriquecido en barras de combustible. [70] La oferta de Irán de abrir su programa de enriquecimiento de uranio a la participación privada y pública extranjera refleja las sugerencias de un comité de expertos del OIEA que se formó para investigar los métodos para reducir el riesgo de que las actividades sensibles del ciclo del combustible pudieran contribuir a las capacidades nacionales de armas nucleares. [71] Algunos expertos no gubernamentales de los Estados Unidos han respaldado este enfoque. [72] [73]

En todos los demás casos en que la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA llegó a la conclusión de que no se cumplían las salvaguardias en relación con el enriquecimiento o reprocesamiento clandestino, la resolución implicó (en los casos de Irak [74] y Libia [75] [76] [77] ) o se espera que implique (en el caso de Corea del Norte [78] [79] ) como mínimo el fin de actividades sensibles del ciclo del combustible. Según Pierre Goldschmidt , ex director general adjunto y jefe del departamento de salvaguardias del OIEA, y Henry D. Sokolski , director ejecutivo del Centro de Educación sobre Políticas de No Proliferación , algunos otros casos de incumplimiento de las salvaguardias notificados por la Secretaría del OIEA (Corea del Sur, Egipto) nunca se comunicaron al Consejo de Seguridad porque la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA nunca llegó a una conclusión formal de incumplimiento. [80] [81] Aunque el caso de Corea del Sur involucraba el enriquecimiento de uranio a niveles cercanos al grado de armas, [82] el propio país informó voluntariamente sobre la actividad aislada [83] y Goldschmidt ha argumentado que "las consideraciones políticas también jugaron un papel dominante en la decisión de la junta" de no hacer una constatación formal de incumplimiento. [84]

Un informe del Servicio de Investigación del Congreso de Estados Unidos del 23 de marzo de 2012 cita un informe del OIEA del 24 de febrero que dice que Irán había almacenado 240 libras de uranio enriquecido al 20 por ciento como una indicación de su capacidad para enriquecer a niveles más altos. [85] La política autoritaria de Irán puede plantear desafíos adicionales a un programa científico que requiere la cooperación entre muchos especialistas técnicos. [86] Algunos expertos sostienen que el enfoque intenso en el programa nuclear de Irán resta valor a la necesidad de un compromiso diplomático más amplio. [87] [88] Los funcionarios de inteligencia estadounidenses entrevistados por The New York Times en marzo de 2012 dijeron que seguían evaluando que Irán no había reiniciado su programa de armamento, que según la Estimación de Inteligencia Nacional de 2007 Irán había interrumpido en 2003, aunque han encontrado evidencia de que algunas actividades relacionadas con el armamento han continuado. Se dice que el Mossad israelí comparte esta creencia. [89]

El 14 de agosto de 2002, Alireza Jafarzadeh , portavoz del Consejo Nacional de Resistencia de Irán , reveló públicamente la existencia de dos instalaciones nucleares en construcción: una instalación de enriquecimiento de uranio en Natanz (parte de la cual es subterránea) y una instalación de agua pesada en Arak . Se ha sugerido firmemente que las agencias de inteligencia ya sabían sobre estas instalaciones, pero los informes habían sido clasificados. [2]

El OIEA solicitó inmediatamente acceso a esas instalaciones y más información y cooperación del Irán en relación con su programa nuclear. [90] Según los acuerdos vigentes en ese momento para la aplicación del acuerdo de salvaguardias del Irán con el OIEA, [91] el Irán no estaba obligado a permitir las inspecciones del OIEA de una nueva instalación nuclear hasta seis meses antes de que se introdujera material nuclear en ella. En ese momento, el Irán ni siquiera estaba obligado a informar al OIEA de la existencia de la instalación. Esta cláusula de los "seis meses" era la norma para la aplicación de todos los acuerdos de salvaguardias del OIEA hasta 1992, cuando la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA decidió que las instalaciones debían ser informadas durante la fase de planificación, incluso antes de que comenzara la construcción. El Irán fue el último país en aceptar esa decisión, y sólo lo hizo el 26 de febrero de 2003, después de que comenzara la investigación del OIEA. [3]

En mayo de 2003, poco después de la invasión estadounidense de Irak , algunos elementos del gobierno de Mohamed Jatamí hicieron una propuesta confidencial para un "Gran Pacto" a través de los canales diplomáticos suizos. Ofrecía una transparencia total del programa nuclear de Irán y la retirada del apoyo a Hamás y Hezbolá , a cambio de garantías de seguridad de los Estados Unidos y una normalización de las relaciones diplomáticas. La administración Bush no respondió a la propuesta, ya que altos funcionarios estadounidenses dudaban de su autenticidad. Según se informa, la propuesta fue ampliamente aprobada por el gobierno iraní, incluido el líder supremo, el ayatolá Jamenei . [92] [93] [94]

Francia, Alemania y el Reino Unido (los tres países de la UE ) emprendieron una iniciativa diplomática con Irán para resolver las cuestiones relativas a su programa nuclear. El 21 de octubre de 2003, en Teherán, el Gobierno iraní y los ministros de Asuntos Exteriores de los tres países de la UE emitieron una declaración conocida como la Declaración de Teherán [95] en la que Irán aceptaba cooperar con el OIEA, firmar y aplicar un Protocolo Adicional como medida voluntaria de fomento de la confianza y suspender sus actividades de enriquecimiento y reprocesamiento durante el curso de las negociaciones. A cambio, los tres países de la UE aceptaron explícitamente reconocer los derechos nucleares de Irán y discutir las formas en que Irán podría proporcionar "garantías satisfactorias" respecto de su programa de energía nuclear, después de lo cual Irán obtendría un acceso más fácil a la tecnología moderna. Irán firmó un Protocolo Adicional el 18 de diciembre de 2003 y aceptó actuar como si el protocolo estuviera en vigor, presentando los informes requeridos al OIEA y permitiendo el acceso requerido a los inspectores del OIEA, en espera de que Irán ratificara el Protocolo Adicional.

El 10 de noviembre de 2003, el OIEA informó [96] de que "es evidente que el Irán ha incumplido en varios casos y durante un período prolongado las obligaciones que le impone su Acuerdo de Salvaguardias en lo que respecta a la notificación de material nuclear y su procesamiento y utilización, así como a la declaración de las instalaciones en las que se ha procesado y almacenado dicho material". El Irán tenía la obligación de informar al OIEA de su importación de uranio de China y del uso posterior de ese material en actividades de conversión y enriquecimiento de uranio. También tenía la obligación de informar sobre los experimentos de separación de plutonio. Sin embargo, la República Islámica incumplió su promesa de permitir al OIEA realizar sus inspecciones y suspendió el acuerdo del Protocolo Adicional esbozado anteriormente en octubre de 2005.

Una lista completa de las "violaciones" específicas de Irán a su acuerdo de salvaguardias, que el OIEA describió como parte de un "patrón de ocultamiento", se puede encontrar en un informe del OIEA del 15 de noviembre de 2004 sobre el programa nuclear de Irán. [97] Irán atribuyó su falta de información sobre ciertas adquisiciones y actividades al obstruccionismo de los EE.UU., que según se informa incluyó presionar al OIEA para que dejara de proporcionar asistencia técnica al programa de conversión de uranio de Irán en 1983. [60] [98] Sobre la cuestión de si Irán tenía un programa oculto de armas nucleares, el informe del OIEA de noviembre de 2003 afirma que no encontró "ninguna prueba" de que las actividades no declaradas previamente estuvieran relacionadas con un programa de armas nucleares, pero también que no pudo concluir que el programa nuclear de Irán fuera exclusivamente pacífico.

En junio de 2004 se inició la construcción del IR-40 , un reactor de agua pesada de 40 MW .

En virtud de los términos del Acuerdo de París, [99] el 14 de noviembre de 2004, el negociador nuclear jefe de Irán anunció una suspensión voluntaria y temporal de su programa de enriquecimiento de uranio (el enriquecimiento no es una violación del TNP) y la implementación voluntaria del Protocolo Adicional, después de la presión del Reino Unido, Francia y Alemania en nombre de la Unión Europea . En ese momento se dijo que la medida era una medida voluntaria de fomento de la confianza, que continuaría durante un período de tiempo razonable (se mencionaron seis meses como referencia) mientras continuaban las negociaciones con la UE-3. El 24 de noviembre, Irán intentó modificar los términos de su acuerdo con la UE para excluir un puñado de equipos de este acuerdo para trabajos de investigación. Esta solicitud fue abandonada cuatro días después. Según Seyed Hossein Mousavian , uno de los representantes iraníes en las negociaciones del Acuerdo de París, los iraníes dejaron en claro a sus homólogos europeos que Irán no consideraría un fin permanente al enriquecimiento de uranio:

Antes de que se firmara el texto del Acuerdo de París, el Dr. Rohani... subrayó que no debían comprometerse a no hablar ni siquiera a pensar en una cesación. Los embajadores transmitieron su mensaje a sus ministros de Asuntos Exteriores antes de la firma del texto acordado en París... Los iraníes dejaron claro a sus homólogos europeos que si estos últimos pedían una terminación completa de las actividades del ciclo del combustible nuclear de Irán, no habría negociaciones. Los europeos respondieron que no pedían tal terminación, sino sólo una garantía de que el programa nuclear de Irán no se desviaría hacia fines militares. [100]

En febrero de 2005, Irán presionó a los tres países de la UE para que aceleraran las conversaciones, a lo que se negaron. [101] Las conversaciones avanzaron poco debido a las posiciones divergentes de las dos partes. [102] Bajo presión de los Estados Unidos, los negociadores europeos no pudieron aceptar el enriquecimiento en suelo iraní. Aunque los iraníes presentaron una oferta que incluía restricciones voluntarias al volumen y la producción de enriquecimiento, fue rechazada. Los tres países de la UE rompieron un compromiso que habían asumido de reconocer el derecho de Irán, en virtud del TNP, al uso pacífico de la energía nuclear. [103]

A principios de agosto de 2005, después de la elección de Mahmud Ahmadineyad como presidente en junio, Irán retiró los sellos de su equipo de enriquecimiento de uranio en Isfahán , [104] lo que los funcionarios del Reino Unido calificaron de "violación del Acuerdo de París" [105] aunque se puede argumentar que la UE violó los términos del Acuerdo de París al exigir que Irán abandonara el enriquecimiento nuclear. [106] Varios días después, la UE-3 ofreció a Irán un paquete a cambio del cese permanente del enriquecimiento. Según se informa, incluía beneficios en los campos político, comercial y nuclear, así como suministros a largo plazo de materiales nucleares y garantías de no agresión por parte de la UE (pero no de los EE. UU.). [105] El subdirector de la AEOI, Mohammad Saeedi, rechazó la oferta como "muy insultante y humillante" [105] y los analistas independientes la caracterizaron como una "caja vacía". [107] El anuncio de Irán de que reanudaría el enriquecimiento de uranio precedió en varios meses a la elección de Ahmadinejad. La demora en la reanudación del programa se hizo para permitir que el OIEA reinstalara el equipo de vigilancia. La reanudación efectiva del programa coincidió con la elección de Ahmadinejad y el nombramiento de Ali Larijani como negociador principal en materia nuclear. [108]

Alrededor de 2005, Alemania se negó a seguir exportando equipo nuclear o a reembolsar el dinero que Irán había pagado por dicho equipo en la década de 1980. [29]

En agosto de 2005, con la ayuda de Pakistán, [109] un grupo de expertos del gobierno de los Estados Unidos y científicos internacionales llegó a la conclusión de que los rastros de uranio apto para bombas encontrados en Irán provenían de equipo paquistaní contaminado y no eran evidencia de un programa de armas clandestino en Irán. [110] En septiembre de 2005, el Director General del OIEA, Mohamed ElBaradei, informó que "la mayoría" de los rastros de uranio altamente enriquecido encontrados en Irán por los inspectores del organismo provenían de componentes de centrifugadoras importados, lo que validó la afirmación de Irán de que los rastros se debían a la contaminación. Fuentes de Viena y del Departamento de Estado habrían declarado que, a todos los efectos prácticos, la cuestión del UME había sido resuelta. [111]

En un discurso pronunciado ante las Naciones Unidas el 17 de septiembre de 2005, Ahmadinejad sugirió que el enriquecimiento de uranio por parte de Irán podría ser gestionado por un consorcio internacional, en el que Irán compartiría la propiedad con otros países. La oferta fue rechazada de plano por la UE y los Estados Unidos. [103]

La Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA aplazó una decisión formal sobre el caso nuclear de Irán durante dos años después de 2003, mientras que Irán continuó cooperando con los tres países de la UE. El 24 de septiembre de 2005, después de que Irán abandonara el Acuerdo de París, la Junta concluyó que Irán había incumplido su acuerdo de salvaguardias, basándose principalmente en hechos que se habían comunicado ya en noviembre de 2003. [112]

El 4 de febrero de 2006, la Junta de 35 miembros votó 27 a 3 (con cinco abstenciones: Argelia , Belarús , Indonesia , Libia y Sudáfrica) a favor de informar sobre Irán al Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas. La medida fue patrocinada por la UE-3 y respaldada por los Estados Unidos. Dos miembros permanentes del Consejo, Rusia y China, aceptaron la remisión sólo con la condición de que el Consejo no tomara ninguna medida hasta marzo. Los tres miembros que votaron en contra de la remisión fueron Venezuela , Siria y Cuba . [113] [114] En respuesta, el 6 de febrero de 2006, Irán suspendió su aplicación voluntaria del Protocolo Adicional y toda otra cooperación voluntaria y no vinculante con el OIEA más allá de la requerida por su acuerdo de salvaguardias. [115]

A fines de febrero de 2006, el Director del OIEA, El Baradei, propuso un acuerdo por el cual Irán renunciaría al enriquecimiento a escala industrial y limitaría su programa a una instalación piloto de pequeña escala, y aceptaría importar su combustible nuclear de Rusia (véase banco de combustible nuclear ). Los iraníes indicaron que, si bien en principio no estarían dispuestos a renunciar a su derecho al enriquecimiento, estaban dispuestos a [116] considerar un compromiso. Sin embargo, en marzo de 2006, la administración Bush dejó en claro que no aceptaría ningún enriquecimiento en Irán. [117]

La Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA aplazó el informe oficial al Consejo de Seguridad sobre el incumplimiento del Irán (requerido por el Artículo XII.C del Estatuto del OIEA) [118] hasta el 27 de febrero de 2006. [119] La Junta normalmente toma decisiones por consenso, pero en una decisión poco frecuente adoptó la resolución por votación, con 12 abstenciones. [120]

El 11 de abril de 2006, Ahmadinejad anunció que Irán había enriquecido uranio con éxito en un discurso televisado desde la ciudad nororiental de Mashhad , donde dijo: "Estoy anunciando oficialmente que Irán se unió al grupo de aquellos países que tienen tecnología nuclear". El uranio fue enriquecido al 3,5 por ciento utilizando más de cien centrifugadoras.

El 13 de abril de 2006, después de que la Secretaria de Estado de los EE.UU. Condoleezza Rice dijera el día anterior que el Consejo de Seguridad debía considerar la posibilidad de adoptar "medidas enérgicas" para inducir a Teherán a cambiar el curso de sus ambiciones nucleares, Ahmadinejad prometió que Irán no se apartaría del enriquecimiento de uranio y que el mundo debía tratar a Irán como una potencia nuclear, diciendo: "Nuestra respuesta a quienes están enfadados porque Irán ha logrado completar el ciclo completo del combustible nuclear es sólo una frase. Les decimos: enfadémonos con nosotros y muéranse de ira", porque "no vamos a mantener conversaciones con nadie sobre el derecho de la nación iraní a enriquecer uranio". [121]

El 14 de abril de 2006, el Instituto de Ciencia y Seguridad Internacional publicó una serie de imágenes satelitales analizadas de las instalaciones nucleares iraníes de Natanz e Isfahán. [122] En estas imágenes se muestra una nueva entrada al túnel cerca de la Instalación de Conversión de Uranio de Isfahán y la continuación de la construcción en el sitio de enriquecimiento de uranio de Natanz. Además, una serie de imágenes que datan de 2002 muestran los edificios subterráneos de enriquecimiento y su posterior recubrimiento con tierra, hormigón y otros materiales. Ambas instalaciones ya estaban sujetas a las inspecciones y salvaguardias del OIEA.

El 28 de julio de 2006, el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas aprobó una resolución que daba a Irán hasta finales de agosto para suspender el enriquecimiento de uranio o enfrentarse a la amenaza de sanciones . [123]

Irán respondió a la demanda de detener el enriquecimiento de uranio el 24 de agosto de 2006, ofreciendo regresar a la mesa de negociaciones pero negándose a poner fin al enriquecimiento. [124]

El 30 de agosto de 2006, el presidente del Majlis, Qolam Ali Hadad-adel , dijo que Irán tenía derecho a "utilizar con fines pacíficos la tecnología nuclear y todos los demás funcionarios están de acuerdo con esta decisión", según la agencia de noticias semioficial de los estudiantes iraníes . "Irán abrió la puerta a las negociaciones para Europa y espera que la respuesta que se dio al paquete nuclear los lleve a la mesa de negociaciones". [124]

En la Resolución 1696 del 31 de julio de 2006, el Consejo de Seguridad exigió que Irán suspendiera todas las actividades relacionadas con el enriquecimiento y el reprocesamiento. [125]

En la Resolución 1737 del 26 de diciembre de 2006, el Consejo impuso una serie de sanciones a Irán por su incumplimiento de la Resolución 1696. [126] Estas sanciones estaban dirigidas principalmente contra la transferencia de tecnologías nucleares y de misiles balísticos [127] y, en respuesta a las preocupaciones de China y Rusia, eran más leves que las solicitadas por los Estados Unidos. [128] Esta resolución siguió a un informe del OIEA de que Irán había permitido inspecciones en virtud de su acuerdo de salvaguardias, pero no había suspendido sus actividades relacionadas con el enriquecimiento. [129]

El Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU ha aprobado ocho resoluciones sobre el programa nuclear de Irán:

El OIEA ha declarado constantemente que no puede concluir que el programa nuclear de Irán sea enteramente pacífico. Normalmente, esa conclusión sólo se sacaría en el caso de países que tienen un Protocolo Adicional en vigor. Irán dejó de aplicar el Protocolo Adicional en 2006, y también cesó toda otra cooperación con el OIEA más allá de lo que Irán reconoció que estaba obligado a proporcionar en virtud de su acuerdo de salvaguardias, después de que la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA decidiera, en febrero de 2006, informar al Consejo de Seguridad sobre el incumplimiento de las salvaguardias por parte de Irán. [115] El Consejo, invocando el Capítulo VII de la Carta de las Naciones Unidas , aprobó entonces la Resolución 1737, que obligaba a Irán a aplicar el Protocolo Adicional. Irán respondió que sus actividades nucleares eran pacíficas y que la participación del Consejo de Seguridad era maliciosa e ilegal. [130] En agosto de 2007, Irán y el OIEA llegaron a un acuerdo sobre las modalidades para resolver las cuestiones pendientes restantes, [131] y avanzaron en las cuestiones pendientes, excepto en la cuestión de los "supuestos estudios" sobre el uso de armas por parte de Irán. [132] El Irán afirmó que no había abordado los supuestos estudios en el plan de trabajo del OIEA porque no estaban incluidos en el plan. [133] El OIEA no detectó el uso real de material nuclear en relación con los supuestos estudios y dijo que lamentaba no haber podido proporcionar al Irán copias de la documentación relativa a los supuestos estudios, pero dijo que la documentación era completa y detallada y, por lo tanto, debía tomarse en serio. El Irán afirmó que las acusaciones se basan en documentos "falsificados" y datos "fabricados", y que no había recibido copias de la documentación que le permitieran demostrar que eran falsificados y fabricados. [134] [135]

En 2011, el OIEA comenzó a expresar una creciente preocupación por las posibles dimensiones militares del programa nuclear de Irán y publicó una serie de informes que criticaban el programa nuclear de Irán en ese sentido. [136]

En febrero de 2007, diplomáticos anónimos del OIEA supuestamente se quejaron de que la mayor parte de la información estadounidense compartida con el OIEA había resultado inexacta y ninguna había conducido a descubrimientos significativos dentro de Irán. [137]

El 10 de mayo de 2007, Irán y el OIEA negaron vehementemente los informes de que Irán había bloqueado a los inspectores del OIEA cuando intentaron acceder a las instalaciones de enriquecimiento de uranio de Irán. El 11 de marzo de 2007, Reuters citó al portavoz del OIEA Marc Vidricaire: "No se nos ha negado el acceso en ningún momento, ni siquiera en las últimas semanas. Normalmente no hacemos comentarios sobre esos informes, pero esta vez sentimos que teníamos que aclarar el asunto... Si tuviéramos un problema como ése, tendríamos que informar al consejo directivo [del OIEA, integrado por 35 naciones]... Eso no ha sucedido porque este supuesto suceso no tuvo lugar". [138]

El 30 de julio de 2007, los inspectores del OIEA pasaron cinco horas en el complejo de Arak, la primera visita de ese tipo desde abril. Se esperaban visitas a otras plantas del Irán durante los días siguientes. Se ha sugerido que tal vez se les haya concedido el acceso en un intento de evitar nuevas sanciones. [139]

En un informe del OIEA a la Junta de Gobernadores del 30 de agosto de 2007 se afirmaba que la planta de enriquecimiento de combustible de Natanz, en el Irán, estaba funcionando "muy por debajo de la cantidad prevista para una instalación de este diseño" y que 12 de las 18 cascadas de centrifugadoras previstas en la planta estaban funcionando. En el informe se afirmaba que el OIEA había "logrado verificar que no se habían desviado los materiales nucleares declarados en las instalaciones de enriquecimiento del Irán" y que se consideraban "resueltos" los problemas de larga data relacionados con los experimentos con plutonio y la contaminación con UME en los contenedores de combustible gastado. Sin embargo, el informe añadía que el Organismo seguía sin poder verificar determinados aspectos relacionados con el alcance y la naturaleza del programa nuclear del Irán.

En el informe también se esbozaba un plan de trabajo acordado por Irán y el OIEA el 21 de agosto de 2007. El plan de trabajo reflejaba un acuerdo sobre "modalidades para resolver las cuestiones pendientes de aplicación de las salvaguardias, incluidas las cuestiones pendientes desde hace mucho tiempo". Según el plan, estas modalidades abarcaban todas las cuestiones pendientes relativas al programa y las actividades nucleares anteriores de Irán. El informe del OIEA describía el plan de trabajo como "un importante paso adelante", pero añadía que "el Organismo considera esencial que Irán se adhiera al cronograma definido en él e implemente todas las salvaguardias y medidas de transparencia necesarias, incluidas las medidas previstas en el Protocolo Adicional". [140] Aunque el plan de trabajo no incluía un compromiso por parte de Irán de aplicar el Protocolo Adicional, el jefe de salvaguardias del OIEA, Olli Heinonen, observó que las medidas del plan de trabajo "para resolver nuestras cuestiones pendientes van más allá de los requisitos del Protocolo Adicional". [141]

Según Reuters, el informe probablemente frenaría la presión de Washington para imponer sanciones más severas contra Irán. Un alto funcionario de la ONU que estaba al tanto dijo que los esfuerzos de Estados Unidos por intensificar las sanciones contra Irán provocarían una reacción nacionalista por parte de Irán que haría retroceder la investigación del OIEA en ese país. [142] A fines de octubre de 2007, el inspector jefe del OIEA, Olli Heinonen, calificó la cooperación iraní con el OIEA como "buena", aunque todavía quedaba mucho por hacer. [143]

A finales de octubre de 2007, según el International Herald Tribune , el director del OIEA, Mohamed ElBaradei, declaró que no había visto "ninguna prueba" de que Irán estuviera desarrollando armas nucleares. El IHT citó a ElBaradei diciendo: "Tenemos información de que tal vez se han hecho algunos estudios sobre la posible fabricación de armas. Por eso hemos dicho que no podemos dar un pase a Irán en este momento, porque todavía hay muchos signos de interrogación... Pero ¿hemos visto que Irán tenga el material nuclear que pueda utilizarse fácilmente en un arma? No. ¿Hemos visto un programa activo de fabricación de armas? No". El informe del IHT continuaba diciendo que "ElBaradei dijo que estaba preocupado por la creciente retórica de los EE.UU., que observó que se centraba en las supuestas intenciones de Irán de construir un arma nuclear en lugar de en la prueba de que el país lo estuviera haciendo activamente. Si hay pruebas reales, ElBaradei dijo que le gustaría verlas". [144]

Un informe del OIEA del 15 de noviembre de 2007 concluyó que en nueve cuestiones pendientes enumeradas en el plan de trabajo de agosto de 2007, incluidos los experimentos con la centrífuga P-2 y el trabajo con metales de uranio, "las declaraciones de Irán son coherentes con... la información de que dispone el organismo", pero advirtió que su conocimiento de la actual labor atómica de Teherán se estaba reduciendo debido a la negativa de Irán a seguir aplicando voluntariamente el Protocolo Adicional, como había hecho en el pasado en virtud del acuerdo de Teherán de octubre de 2003 y el acuerdo de París de noviembre de 2004. Las únicas cuestiones pendientes eran los rastros de UME encontrados en un lugar y las acusaciones de las agencias de inteligencia estadounidenses basadas en una computadora portátil supuestamente robada a Irán que supuestamente contenía diseños relacionados con armas nucleares. El informe del OIEA también afirmó que Teherán sigue produciendo UME. Irán ha declarado que tiene derecho a la tecnología nuclear pacífica en virtud del TNP, a pesar de las exigencias del Consejo de Seguridad de que cese su enriquecimiento nuclear. [145]

El 18 de noviembre de 2007, Ahmadinejad anunció que tenía la intención de consultar con las naciones árabes sobre un plan, bajo los auspicios del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo , para enriquecer uranio en un tercer país neutral, como Suiza. [146]

Israel criticó los informes del OIEA sobre Irán y sobre el ex director del organismo, El Baradei. El Ministro de Asuntos Estratégicos de Israel, Avigdor Lieberman, desestimó los informes del OIEA calificándolos de "inaceptables" y acusó al director del organismo, El Baradei, de ser "proiraní". [147]

El 11 de febrero de 2008, informes de prensa indicaron que el informe del OIEA sobre el cumplimiento por parte de Irán del plan de trabajo de agosto de 2007 se retrasaría debido a desacuerdos internos sobre las conclusiones previstas del informe de que se habían resuelto los principales problemas. [148] El Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores francés , Bernard Kouchner, declaró que se reuniría con El Baradei para convencerlo de que "escuche a Occidente" y recordarle que el OIEA sólo se encarga del "aspecto técnico" y no del "aspecto político" de la cuestión. [149] Un alto funcionario del OIEA negó los informes de desacuerdos internos y acusó a las potencias occidentales de utilizar las mismas tácticas de "exageración" empleadas contra Irak antes de la invasión liderada por Estados Unidos en 2003 para justificar la imposición de nuevas sanciones a Irán por su programa nuclear. [150]

El 22 de febrero de 2008, el OIEA publicó su informe sobre la aplicación de las salvaguardias en el Irán. [151] ElBaradei declaró que "hemos logrado aclarar todas las cuestiones pendientes, incluida la más importante, que es el alcance y la naturaleza del programa de enriquecimiento del Irán", con la excepción de una sola cuestión, "y es la de los supuestos estudios de armamentización que supuestamente el Irán ha realizado en el pasado". [152]

Según el informe, el OIEA compartió con Irán información de inteligencia recientemente proporcionada por los EE.UU. sobre "supuestos estudios" sobre un programa de fabricación de armas nucleares. La información supuestamente se obtuvo de un ordenador portátil sacado de contrabando de Irán y proporcionado a los EE.UU. a mediados de 2004. [153] Se dice que el ordenador portátil fue recibido de un "antiguo contacto" en Irán que lo obtuvo de otra persona que ahora se cree que está muerta. [154] Un diplomático europeo de alto rango advirtió: "Puedo inventar esos datos", y argumentó que los documentos parecen "hermosos, pero están abiertos a dudas". [154] Estados Unidos se ha basado en el ordenador portátil para demostrar que Irán tiene la intención de desarrollar armas nucleares. [154] En noviembre de 2007, la Estimación Nacional de Inteligencia de los Estados Unidos (NIE) creía que Irán detuvo un supuesto programa activo de armas nucleares en 2003. [4] Irán ha descartado la información del ordenador portátil como una invención, y otros diplomáticos han descartado la información como relativamente insignificante y que llegó demasiado tarde. [155]

El informe del OIEA de febrero de 2008 afirma que el OIEA "no ha detectado el uso de material nuclear en relación con los supuestos estudios, ni tiene información creíble al respecto". [151]

El 26 de mayo de 2008, el OIEA publicó otro informe periódico sobre la aplicación de las salvaguardias en el Irán [156] , en el que el OIEA ha podido seguir verificando la no desviación de material nuclear declarado en el Irán, y el Irán ha proporcionado al OIEA acceso al material nuclear declarado y a los informes de contabilidad, como lo exige su acuerdo de salvaguardias. El Irán había instalado varias centrifugadoras nuevas, incluidos modelos más avanzados, y las muestras ambientales mostraban que las centrifugadoras "siguieron funcionando como se declaró", produciendo uranio poco enriquecido. El informe también señaló que otros elementos del programa nuclear del Irán seguían estando sujetos a la supervisión y las salvaguardias del OIEA, incluida la construcción de la instalación de agua pesada en Arak, la construcción y el uso de celdas calientes asociadas con el reactor de investigación de Teherán, los esfuerzos de conversión de uranio y el combustible nuclear ruso entregado para el reactor de Bushehr.

En el informe se afirma que el OIEA había solicitado, como "medida de transparencia" voluntaria, que se le permitiera el acceso a los lugares de fabricación de centrifugadoras, pero que el Irán había rechazado la solicitud. El informe del OIEA afirma que el Irán también había presentado respuestas a preguntas sobre las "posibles dimensiones militares" de su programa nuclear, que incluyen "supuestos estudios" sobre un denominado Proyecto Sal Verde , pruebas de alto poder explosivo y vehículos de reentrada de misiles. Según el informe, las respuestas del Irán todavía estaban siendo examinadas por el OIEA en el momento de su publicación. Sin embargo, como parte de su "evaluación general" anterior de las acusaciones, el Irán había respondido que los documentos en los que se formulaban las acusaciones eran falsos, no auténticos o se referían a aplicaciones convencionales. El informe afirma que el Irán puede tener más información sobre los supuestos estudios, que "siguen siendo motivo de grave preocupación", pero que el propio OIEA no había detectado pruebas de que el Irán hubiera diseñado o fabricado realmente armas nucleares o componentes. El OIEA también afirma que no estaba en posesión de ciertos documentos que contenían las acusaciones contra el Irán, por lo que no podía compartirlos con el Irán.

Según el informe del OIEA del 15 de septiembre de 2008 sobre la aplicación de salvaguardias en el Irán [157] , el Irán siguió proporcionando al OIEA acceso a material y actividades nucleares declarados, que seguían realizándose con salvaguardias y sin pruebas de que se hubiera desviado material nuclear para usos no pacíficos. No obstante, el informe reiteró que el OIEA no podría verificar la naturaleza exclusivamente pacífica del programa nuclear del Irán a menos que el Irán adoptara "medidas de transparencia" que excedieran su acuerdo de salvaguardias con el OIEA, ya que el OIEA no verifica la ausencia de actividades nucleares no declaradas en ningún país a menos que el Protocolo Adicional esté en vigor.

El Baradei declaró que "hemos logrado aclarar todas las cuestiones pendientes, incluida la más importante, que es el alcance y la naturaleza del programa de enriquecimiento de Irán", con la excepción de una sola cuestión, "y es los supuestos estudios de armamentización que supuestamente Irán ha realizado en el pasado". [158] Según el informe, Irán había aumentado el número de centrifugadoras operativas en su planta de enriquecimiento de combustible en Isfahán y continuaba enriqueciendo uranio. Contrariamente a algunos informes de los medios de comunicación que afirmaban que Irán había desviado hexafluoruro de uranio (UF6 ) para un renovado programa de armas nucleares, [159] el OIEA enfatizó que todo el UF6 estaba bajo las salvaguardias del OIEA. También se le pidió a Irán que aclarara la información sobre la asistencia extranjera que pudiera haber recibido en relación con una carga explosiva de alto poder para un dispositivo nuclear de tipo implosión. Irán declaró que no había habido tales actividades en Irán. [157]

El OIEA también informó de que había celebrado una serie de reuniones con funcionarios iraníes para resolver las cuestiones pendientes, incluidos los "supuestos estudios" sobre la fabricación de armas nucleares que se enumeraban en el informe del OIEA de mayo de 2008. Durante el curso de esas reuniones, los iraníes presentaron una serie de respuestas escritas, incluida una presentación de 117 páginas que confirmaba la veracidad parcial de algunas de las acusaciones, pero en la que se afirmaba que las acusaciones en su conjunto se basaban en documentos "falsificados" y datos "fabricados", y que el Irán no había recibido realmente la documentación que corroboraba las acusaciones. Según el "Acuerdo de Modalidades" de agosto de 2007 entre el Irán y el OIEA, el Irán había acordado examinar y evaluar las afirmaciones sobre los "supuestos estudios", como gesto de buena fe, "tras recibir todos los documentos relacionados". [160]

Si bien el informe volvió a expresar su "pesar" por el hecho de que el OIEA no hubiera podido proporcionar al Irán copias de la documentación relativa a los supuestos estudios, también instó al Irán a que proporcionara al OIEA "información sustantiva que respaldara sus declaraciones y facilitara el acceso a la documentación y a las personas pertinentes" en relación con los supuestos estudios, como "cuestión de transparencia". [157] El OIEA presentó una serie de propuestas al Irán para ayudar a resolver las acusaciones y expresó su disposición a debatir modalidades que pudieran permitirle demostrar de manera creíble que las actividades a las que se hacía referencia en la documentación no estaban relacionadas con la energía nuclear, como afirmaba el Irán, al tiempo que protegía la información sensible relacionada con sus actividades militares convencionales. El informe no indica si el Irán aceptó o rechazó esas propuestas. [157]

El informe también reiteró que los inspectores del OIEA no habían encontrado "ninguna prueba del diseño o fabricación reales por parte de Irán de componentes de material nuclear de un arma nuclear o de ciertos otros componentes clave, como iniciadores, o de estudios de física nuclear relacionados... El Organismo tampoco ha detectado el uso real de material nuclear en relación con los supuestos estudios", pero insistió en que el OIEA no podría verificar formalmente la naturaleza pacífica del programa nuclear de Irán a menos que Irán hubiera acordado adoptar las "medidas de transparencia" solicitadas. [157]

En un informe presentado el 19 de febrero de 2009 a la Junta de Gobernadores, [161] El Baradei informó de que el Irán seguía enriqueciendo uranio en contravención de las decisiones del Consejo de Seguridad y había producido más de una tonelada de uranio poco enriquecido. Los resultados de las muestras ambientales tomadas por el OIEA en la FEP y la PFEP5 indicaban que las plantas habían estado funcionando a los niveles declarados por Teherán, "dentro de las incertidumbres de medición normalmente asociadas a las plantas de enriquecimiento de una capacidad similar". El OIEA también pudo confirmar que no se estaban llevando a cabo actividades relacionadas con el reprocesamiento en el reactor de investigación de Teherán y la instalación de producción de radioisótopos de xenón del Irán.

Según el informe, Irán también siguió negándose a proporcionar información sobre el diseño o acceso para verificar la información sobre el diseño de su reactor de investigación de agua pesada IR-40. En febrero de 2003, Irán y el OIEA acordaron modificar una disposición del Acuerdo Subsidiario de su acuerdo de salvaguardias (Código 3.1) para exigir dicho acceso. [162] Irán dijo al OIEA en marzo de 2007 que "suspendía" la aplicación del Código 3.1 modificado, que había sido "aceptado en 2003, pero aún no ratificado por el parlamento", y que "volvería" a la aplicación de la versión de 1976 del Código 3.1. [163] El acuerdo subsidiario sólo puede modificarse por acuerdo mutuo. [164] Irán dice que, dado que el reactor no está en condiciones de recibir material nuclear, la solicitud de acceso del OIEA no estaba justificada, y pidió que el OIEA no programara una inspección para verificar la información sobre el diseño. [161] El OIEA afirma que su derecho a verificar la información de diseño que se le proporciona es un "derecho continuo, que no depende de la etapa de construcción de una instalación ni de la presencia de material nuclear en ella". [163]

En cuanto a los "supuestos estudios" sobre la fabricación de armas nucleares, el OIEA dijo que "como resultado de la continua falta de cooperación por parte del Irán en relación con las cuestiones restantes que dan lugar a preocupaciones sobre las posibles dimensiones militares del programa nuclear del Irán, el Organismo no ha logrado ningún progreso sustancial en esas cuestiones" y pidió a los Estados miembros que habían proporcionado información sobre los supuestos programas que permitieran que se compartiera esa información con el Irán. El OIEA dijo que la continua negativa del Irán a aplicar el Protocolo Adicional era contraria a la solicitud de la Junta de Gobernadores y del Consejo de Seguridad y que podía seguir verificando la no desviación del material nuclear declarado en el Irán. [165] El Irán dijo que durante los seis años que el Organismo había estado examinando su caso, el OIEA no había encontrado ninguna prueba que demostrara que Teherán estuviera tratando de fabricar un arma nuclear. [166]

En cuanto al informe del OIEA, varios informes de prensa sugirieron que Irán no había informado adecuadamente sobre la cantidad de uranio poco enriquecido que poseía porque las estimaciones iraníes no coincidían con las conclusiones del inspector del OIEA, y que Irán ahora tenía suficiente uranio para fabricar una bomba nuclear. [167] [168] El informe fue ampliamente criticado como injustificadamente provocativo y exagerado. [169] [170] [171] En respuesta a la controversia, la portavoz del OIEA, Melissa Fleming, afirmó que el OIEA no tenía ninguna razón para creer que las estimaciones de uranio poco enriquecido producido por Irán fueran un error intencional, y que no se podía retirar material nuclear de la instalación para enriquecerlo aún más para fabricar armas nucleares sin el conocimiento del organismo, ya que la instalación está sujeta a vigilancia por vídeo y el material nuclear se mantiene sellado. [172]

Ali Asghar Soltaniyeh, embajador de Irán ante el OIEA, dijo que el informe de febrero no "ofrecía ninguna nueva perspectiva sobre el programa nuclear de Irán". [173] Afirmó que el informe estaba escrito de una manera que claramente causa malentendidos en la opinión pública. Sugirió que los informes deberían redactarse de manera que tuvieran una sección sobre si Irán ha cumplido con sus obligaciones en virtud del TNP y una sección separada sobre si "el cumplimiento del Protocolo Adicional o de los subacuerdos 1 y 3 exceden el compromiso o no". [ cita requerida ]

En una entrevista de prensa en febrero de 2009, ElBaradei dijo que Irán tiene uranio poco enriquecido, pero "eso no significa que mañana vayan a tener armas nucleares, porque mientras estén bajo la verificación del OIEA, mientras no estén fabricando armas, ya se sabe". ElBaradei continuó diciendo que hay un déficit de confianza con Irán, pero que no se debe exagerar la preocupación y que "muchos otros países están enriqueciendo uranio sin que el mundo haga ningún escándalo al respecto". [174]

En febrero de 2009, El Baradei habría dicho que creía que la posibilidad de un ataque militar a las instalaciones nucleares de Irán había sido descartada. "La fuerza sólo puede utilizarse como última opción... cuando se han agotado todas las demás posibilidades políticas", dijo a Radio France International . [166] [175] El ex director general Hans Blix criticó a los gobiernos occidentales por los años perdidos por sus "enfoques ineficaces" respecto del programa nuclear de Irán. Blix sugirió que Occidente ofreciera "garantías contra ataques desde el exterior y actividades subversivas desde el interior" y también sugirió que la participación de Estados Unidos en la diplomacia regional "ofrecería a Irán un mayor incentivo para alcanzar un acuerdo nuclear que las declaraciones del equipo de Bush de que 'Irán debe comportarse'". [176]

En julio de 2009, el jefe entrante del OIEA, Yukiya Amano , dijo: "No veo ninguna evidencia en los documentos oficiales del OIEA" de que Irán esté tratando de obtener la capacidad de desarrollar armas nucleares. [177]

En septiembre de 2009, El Baradei dijo que Irán había violado la ley al no revelar antes la existencia de la Planta de Enriquecimiento de Combustible de Fordow , su segundo sitio de enriquecimiento de uranio cerca de Qom . Sin embargo, dijo, las Naciones Unidas no tenían pruebas creíbles de que Irán tuviera un programa nuclear operativo. [178]

En noviembre de 2009, 25 miembros de la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA, integrada por 35 naciones, aprobaron una exigencia de los Estados Unidos, Rusia, China y otras tres potencias [ ¿cuáles? ] para que Irán detuviera inmediatamente la construcción de su recién revelada instalación nuclear y congelara el enriquecimiento de uranio. Los funcionarios iraníes restaron importancia a la resolución, pero los Estados Unidos y sus aliados insinuaron que la ONU podría aplicar nuevas sanciones si Irán se mantenía desafiante. [179]

En febrero de 2010, el OIEA informó que Irán no había explicado las compras de tecnología sensible, así como las pruebas secretas de detonadores de alta precisión y diseños modificados de conos de misiles para acomodar cargas útiles más grandes, experimentos estrechamente asociados con ojivas atómicas. [180]

En mayo de 2010, el OIEA informó que Irán había declarado una producción de más de 2,5 toneladas métricas de uranio poco enriquecido, que sería suficiente si se enriquece más para fabricar dos armas nucleares, y que Irán se ha negado a responder a las preguntas de los inspectores sobre una variedad de actividades, incluyendo lo que el organismo llamó las "posibles dimensiones militares" del programa nuclear de Irán. [181] [182]

En julio de 2010, Irán prohibió la entrada en el país a dos inspectores del OIEA. El OIEA rechazó las razones de Irán para la prohibición y dijo que apoyaba plenamente a los inspectores, a los que Teherán había acusado de informar erróneamente sobre la falta de algunos equipos nucleares. [183]

En agosto de 2010, el OIEA afirmó que Irán había comenzado a utilizar un segundo conjunto de 164 centrifugadoras conectadas en cascada para enriquecer uranio hasta un 20% en su planta piloto de enriquecimiento de combustible de Natanz. [184]

En noviembre de 2011, el OIEA informó [185] que los inspectores habían encontrado evidencia creíble de que Irán había estado realizando experimentos destinados a diseñar una bomba nuclear hasta 2003, y que la investigación podría haber continuado en menor escala después de esa fecha. [186] El Director del OIEA, Yukiya Amano, dijo que la evidencia reunida por el organismo "indica que Irán ha llevado a cabo actividades relacionadas con el desarrollo de un dispositivo explosivo nuclear". [187] Varios expertos nucleares occidentales afirmaron que había muy pocas novedades en el informe, [188] y que los informes de los medios de comunicación habían exagerado su importancia. [189] Irán afirmó que el informe era poco profesional y desequilibrado, y que había sido preparado con una influencia política indebida principalmente por los Estados Unidos. [190]

En noviembre de 2011, funcionarios del OIEA identificaron un "gran recipiente de contención de explosivos" dentro de Parchin . [191] El OIEA evaluó posteriormente que Irán había estado realizando experimentos para desarrollar capacidad de armas nucleares. [192]

La Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA aprobó una resolución [193] por 32 votos a favor y 2 en contra, en la que expresaba "profunda y creciente preocupación" por las posibles dimensiones militares del programa nuclear iraní y calificaba de "esencial" que Irán proporcionara información adicional y acceso al OIEA. [6] [194] Estados Unidos acogió con satisfacción la resolución y dijo que intensificaría las sanciones para presionar a Irán a cambiar de rumbo. [195] En respuesta a la resolución del OIEA, Irán amenazó con reducir su cooperación con el OIEA, aunque el Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores iraní, Ali Akbar Salehi, restó importancia a las conversaciones sobre la retirada del TNP o del OIEA. [196]

El 24 de febrero de 2012, el Director General del OIEA, Amano, informó a la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA que delegaciones de alto nivel del OIEA se habían reunido dos veces con funcionarios iraníes para intensificar los esfuerzos por resolver las cuestiones pendientes, pero que seguían existiendo diferencias importantes y que Irán no había concedido las solicitudes del OIEA para acceder al sitio de Parchin , donde el OIEA cree que se han llevado a cabo investigaciones sobre explosivos de alta potencia pertinentes para las armas nucleares. Irán desestimó el informe del OIEA sobre las posibles dimensiones militares de su programa nuclear por basarse en "acusaciones infundadas". Amano pidió a Irán que aceptara un enfoque estructurado, basado en las prácticas de verificación del OIEA, para resolver las cuestiones pendientes. [197] En marzo de 2012, Irán dijo que permitiría otra inspección en Parchin "cuando se llegara a un acuerdo sobre un plan de modalidades". [198] Poco después, se informó de que Irán podría no consentir un acceso sin restricciones. [199] Un estudio de imágenes satelitales del ISIS afirmó haber identificado un sitio explosivo en Parchin. [200]

El informe de febrero del OIEA también describió los avances en los esfuerzos de enriquecimiento y fabricación de combustible de Irán, incluyendo la triplicación del número de cascadas de enriquecimiento de uranio a casi el 20 por ciento y las pruebas de elementos de combustible para el Reactor de Investigación de Teherán y el todavía incompleto reactor de investigación de agua pesada IR-40 . [197] Aunque Irán seguía instalando miles de centrifugadoras adicionales, éstas se basaban en un diseño errático y obsoleto, tanto en su planta principal de enriquecimiento en Natanz como en una instalación más pequeña en Fordow enterrada a gran profundidad. "Parece que todavía están luchando con las centrifugadoras avanzadas", dijo Olli Heinonen, ex inspector nuclear jefe, mientras que el experto nuclear Mark Fitzpatrick señaló que Irán había estado trabajando en "modelos de segunda generación durante más de diez años y todavía no puede ponerlos en funcionamiento a gran escala". [201] Peter Crail y Daryl G. Kimball, de la Asociación de Control de Armas, comentaron que el informe "no identifica ningún avance" y "confirma las impresiones iniciales de que los anuncios de Irán de la semana pasada sobre una serie de 'avances nucleares' fueron exagerados". [202]

En mayo de 2012, el OIEA informó de que Irán había aumentado su tasa de producción de uranio poco enriquecido al 3,5 por ciento y ampliado sus reservas de uranio enriquecido al 19,75 por ciento, pero que estaba teniendo dificultades con las centrifugadoras más avanzadas. [203] El OIEA también informó de la detección de partículas de uranio enriquecido al 27 por ciento en la instalación de enriquecimiento de Fordu . Sin embargo, un diplomático en Viena advirtió de que el aumento de la pureza del uranio detectado por los inspectores podría resultar accidental. [204] Este cambio hizo que el uranio de Irán pasara drásticamente a ser un material apto para fabricar bombas. Hasta entonces, el nivel más alto de pureza que se había encontrado en Irán era del 20 por ciento. [205]

A fines de agosto, el OIEA creó un Grupo de Trabajo sobre Irán para ocuparse de las inspecciones y otras cuestiones relacionadas con el programa nuclear de Irán, en un intento de centrar y agilizar el manejo del programa nuclear de Irán por parte del OIEA concentrando expertos y otros recursos en un equipo dedicado. [206]

El 30 de agosto, el OIEA publicó un informe que mostraba una importante expansión de las actividades iraníes de enriquecimiento. En el informe se decía que Irán había más que duplicado el número de centrifugadoras en la instalación subterránea de Fordow, de 1.064 centrifugadoras en mayo a 2.140 centrifugadoras en agosto, aunque el número de centrifugadoras en funcionamiento no había aumentado. El informe decía que desde 2010 Irán había producido unos 190 kg de uranio enriquecido al 20%, frente a los 145 kg de mayo. El informe también señalaba que Irán había convertido parte del uranio enriquecido al 20% en una forma de óxido y lo había transformado en combustible para su uso en reactores de investigación, y que una vez que se han producido esta conversión y fabricación, el combustible no puede enriquecerse fácilmente hasta alcanzar una pureza apta para armas. [207] [208]

El informe también expresó su preocupación por Parchin , que el OIEA ha tratado de inspeccionar en busca de pruebas de desarrollo de armas nucleares. Desde que el OIEA solicitó el acceso, "se han llevado a cabo importantes trabajos de excavación y paisajismo en una extensa zona del lugar y sus alrededores", se han demolido cinco edificios, mientras que se han eliminado líneas eléctricas, vallas y caminos pavimentados, todo lo cual obstaculizaría la investigación del OIEA si se le permitiera el acceso. [209]

En una sesión informativa sobre este informe ante la Junta de Gobernadores a principios de septiembre de 2012, el Director General Adjunto del OIEA, Herman Nackaerts, y el Director General Adjunto, Rafael Grossi, mostraron imágenes satelitales a sus estados miembros que supuestamente demuestran los esfuerzos iraníes por eliminar pruebas incriminatorias de sus instalaciones en Parchin, o una "limpieza nuclear". Estas imágenes mostraban un edificio en Parchin cubierto con lo que parecía ser una lona rosa, así como la demolición del edificio y la remoción de tierra que, según el OIEA, "dificultarían significativamente" su investigación. Un diplomático occidental de alto rango describió la presentación como "bastante convincente". El Instituto para la Ciencia y la Seguridad Internacional (ISIS) dijo que el propósito de la lona rosa podría ser ocultar a los satélites "trabajos de limpieza" adicionales. Sin embargo, Ali Asghar Soltanieh, enviado de Irán al OIEA, negó el contenido de la presentación, diciendo que "simplemente tener una foto desde allí arriba, una imagen satelital... esa no es la forma en que el organismo debe hacer su trabajo profesional". [210]

Según la Associated Press, el OIEA recibió "nueva e importante información de inteligencia" en septiembre de 2012, que cuatro diplomáticos confirmaron que fue la base de un pasaje del informe del OIEA de agosto de 2012 que decía que "la agencia ha obtenido más información que corrobora aún más" las sospechas. Según se informa, la información de inteligencia indica que Irán había avanzado en el trabajo de modelado informático del rendimiento de una ojiva nuclear, trabajo que David Albright, del ISIS, dijo que era "crucial para el desarrollo de un arma nuclear". La información de inteligencia también aumentaría los temores del OIEA de que Irán haya avanzado en su investigación de armas en múltiples frentes, ya que el modelado informático suele ir acompañado de pruebas físicas de los componentes que entrarían en un arma nuclear. [211]

En respuesta a este informe, el 13 de septiembre la Junta de Gobernadores del OIEA aprobó una resolución que reprendió a Irán por desafiar las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas de suspender el enriquecimiento de uranio y pidió a Irán que permitiera las inspecciones de las pruebas de que está buscando tecnología armamentística. [212] La resolución, que se aprobó por 31 votos a favor, 1 en contra y 3 abstenciones, también expresó "serias preocupaciones" sobre el programa nuclear de Irán, al tiempo que deseaba una solución pacífica. El diplomático estadounidense de alto rango Robert Wood culpó a Irán de "demoler sistemáticamente" una instalación en la base militar de Parchin, que los inspectores del OIEA han intentado visitar en el pasado, pero a la que no se les ha concedido el acceso, diciendo que "Irán ha estado tomando medidas que parecen coherentes con un esfuerzo por eliminar las pruebas de sus actividades pasadas en Parchin". [213] La resolución fue presentada conjuntamente por China, Francia, Alemania, Rusia, los Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido. [214]

El 16 de noviembre, el OIEA publicó un informe que muestra la continua expansión de las capacidades iraníes de enriquecimiento de uranio. En Fordow, se han instalado las 2.784 centrifugadoras IR-1 (16 cascadas de 174 cada una), aunque sólo cuatro cascadas están en funcionamiento y otras cuatro están completamente equipadas, probadas al vacío y listas para empezar a funcionar. [215] Irán ha producido aproximadamente 233 kg de uranio enriquecido a casi el 20 por ciento, un aumento de 43 kg desde el informe del OIEA de agosto de 2012. [216]

El informe del OIEA de agosto de 2012 afirmó que Irán había comenzado a utilizar 96 kg de su uranio enriquecido a casi el 20 por ciento para fabricar combustible para el reactor de investigación de Teherán, lo que hace más difícil enriquecer aún más ese uranio hasta el grado de armas , ya que primero tendría que convertirse nuevamente en gas hexafluoruro de uranio. [217] Aunque más de este uranio se ha fabricado en combustible, no se ha enviado uranio adicional a la planta de fabricación de placas de combustible en Isfahán . [215]

En el informe de noviembre se señala que Irán ha seguido negando al OIEA el acceso a la base militar de Parchin . Citando pruebas obtenidas por imágenes satelitales de que "Irán construyó un gran recipiente de contención de explosivos en el que se realizan experimentos hidrodinámicos" relacionados con el desarrollo de armas nucleares, el informe expresa preocupación por la posibilidad de que los cambios que se están produciendo en la base militar de Parchin puedan eliminar las pruebas de actividades nucleares pasadas, y señala que prácticamente no ha habido actividad en ese lugar entre febrero de 2005 y el momento en que el OIEA solicitó el acceso. Esos cambios incluyen:

Irán afirmó que se esperaba que el reactor de investigación de agua pesada IR-40 en Arak comenzara a funcionar en el primer trimestre de 2014. Durante las inspecciones in situ del diseño del IR-40, los inspectores del OIEA observaron que continuaba la instalación de las tuberías del circuito de refrigeración y moderador. [218]

El 21 de febrero, el OIEA publicó un informe que mostraba que la capacidad iraní de enriquecimiento de uranio seguía aumentando. Hasta el 19 de febrero, se habían instalado en Natanz 12.699 centrifugadoras IR-1, lo que incluye la instalación de 2.255 centrifugadoras desde el último informe del OIEA, publicado en noviembre. [219]

Fordow, la instalación nuclear situada cerca de Qom, contiene 16 cascadas, divididas equitativamente entre la Unidad 1 y la Unidad 2, con un total de 2.710 centrifugadoras. Irán sigue utilizando las cuatro cascadas de 174 centrifugadoras IR-1 cada una en dos conjuntos en tándem para producir 19,75 por ciento de uranio poco enriquecido en un total de 696 centrifugadoras de enriquecimiento, el mismo número de centrifugadoras de enriquecimiento que se informó en noviembre de 2012. [220]

Irán ha producido aproximadamente 280 kg de uranio enriquecido al 20 por ciento, un aumento de 47 kg desde el informe del OIEA de noviembre de 2012 y la producción total de uranio poco enriquecido al 3,5 por ciento asciende a 8.271 kg (en comparación con los 7.611 kg informados durante el último trimestre). [219]

El informe del OIEA de febrero de 2013 afirmó que Irán había reanudado la reconversión de uranio enriquecido cerca del 20 por ciento en forma de óxido para fabricar combustible para el reactor de investigación de Teherán, lo que hace más difícil enriquecer aún más ese uranio hasta el grado de armas , ya que primero tendría que convertirse nuevamente en gas UF6. [ 221]

En el informe de febrero se señala que Irán ha seguido negando al OIEA el acceso a la base militar de Parchin , citando pruebas obtenidas por imágenes satelitales de que "Irán construyó un gran recipiente de contención de explosivos en el que se realizan experimentos hidrodinámicos". Esa instalación podría ser un indicador del desarrollo de armas nucleares. En el informe se expresa preocupación por la posibilidad de que los cambios que se están produciendo en la base militar de Parchin puedan eliminar las pruebas de actividades nucleares pasadas, y se señala que prácticamente no ha habido actividad en ese lugar entre febrero de 2005 y el momento en que el OIEA solicitó el acceso. Esos cambios incluyen:

El Irán afirmó que se esperaba que el reactor de investigación de Teherán, moderado por agua pesada, IR-40, en Arak, comenzara a funcionar en el primer trimestre de 2014. Durante las inspecciones in situ del diseño del IR-40, los inspectores del OIEA observaron que la instalación de las tuberías del circuito de refrigeración y moderador, según se había informado anteriormente, estaba casi terminada. El OIEA informó de que el Irán utilizará el reactor de investigación de Teherán para probar el combustible para el reactor IR-40, cuya construcción el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas ha exigido que el Irán deje de construir porque podría utilizarse para producir plutonio para armas nucleares. El informe del OIEA afirma que "el 26 de noviembre de 2012, el Organismo verificó un prototipo de conjunto de combustible de uranio natural IR-40 antes de su traslado al TRR para realizar pruebas de irradiación". [221] Desde su última visita, el 17 de agosto de 2011, el Organismo no ha tenido más acceso a la planta, por lo que depende de imágenes satelitales para supervisar el estado de la planta. [221]