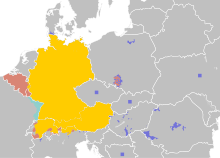

Alemán (alemán: Deutsch , pronunciado [dɔʏtʃ]) )[10]es unalengua germánica occidentalde lafamilia de lenguas indoeuropeas, hablada principalmente enEuropaoccidentaly. Es la lengua nativa más hablada dentro de laUnión Europea. Es el idioma más hablado yoficial(o cooficial) enAlemania,Austria,Suiza,Liechtensteiny la provincia autónoma italiana deTirol del Sur. También es un idioma oficial deLuxemburgo,Bélgicay la región autónoma italiana deFriuli-Venecia Julia, así como unidioma nacionalenNamibia. También hay comunidades de habla alemana notables enFrancia(Alsacia), laRepública Checa(Bohemia del Norte),Polonia(Alta Silesia),Eslovaquia(Región de Košice,SpišyHauerland),Dinamarca(Schleswig del Norte),RumaniayHungría(Sopron).

El alemán es uno de los principales idiomas del mundo . Es la segunda lengua germánica más hablada , después del inglés, tanto como primera como segunda lengua . El alemán también se enseña ampliamente como lengua extranjera , especialmente en Europa continental (donde es la tercera lengua extranjera más enseñada después del inglés y el francés) y en los Estados Unidos. En general, el alemán es la cuarta segunda lengua más comúnmente aprendida, [11] y la tercera segunda lengua más comúnmente aprendida en los Estados Unidos en la educación K-12. [12] El idioma ha sido influyente en los campos de la filosofía, la teología, la ciencia y la tecnología. Es el segundo idioma más utilizado en la ciencia [13] y el tercer idioma más utilizado en sitios web . [13] [14] Los países de habla alemana ocupan el quinto lugar en términos de publicación anual de nuevos libros, con una décima parte de todos los libros (incluidos los libros electrónicos) en el mundo publicados en alemán. [ cita requerida ]

El alemán está estrechamente relacionado con otras lenguas germánicas occidentales, a saber, el afrikáans , el neerlandés , el inglés , las lenguas frisias y el escocés . También contiene similitudes estrechas en vocabulario con algunas lenguas del grupo germánico del norte , como el danés , el noruego y el sueco . El alemán moderno se desarrolló gradualmente a partir del alto alemán antiguo , que a su vez se desarrolló a partir del protogermánico durante la Alta Edad Media .

El alemán es una lengua flexiva , con cuatro casos para sustantivos, pronombres y adjetivos (nominativo, acusativo, genitivo, dativo); tres géneros (masculino, femenino, neutro) y dos números (singular, plural). Tiene verbos fuertes y débiles . La mayor parte de su vocabulario deriva de la antigua rama germánica de la familia de lenguas indoeuropeas, mientras que una parte más pequeña se deriva en parte del latín y el griego , junto con menos palabras prestadas del francés y el inglés moderno . Sin embargo, el inglés es la principal fuente de palabras prestadas más recientes .

El alemán es una lengua pluricéntrica ; las tres variantes estandarizadas son el alemán , el austríaco y el alemán estándar suizo . El alemán estándar a veces se denomina alto alemán , lo que hace referencia a su origen regional. El alemán también es notable por su amplio espectro de dialectos , con muchas variedades existentes en Europa y otras partes del mundo. Algunas de estas variedades no estándar han sido reconocidas y protegidas por gobiernos regionales o nacionales. [15]

Desde 2004, los jefes de Estado de los países de habla alemana se reúnen cada año [16] y el Consejo de Ortografía Alemana es el principal organismo internacional que regula la ortografía alemana .

El alemán es una lengua indoeuropea que pertenece al grupo germánico occidental de las lenguas germánicas . Las lenguas germánicas se subdividen tradicionalmente en tres ramas: germánico del norte , germánico oriental y germánico occidental . La primera de estas ramas sobrevive en el danés moderno , sueco , noruego , feroés e islandés , todos los cuales descienden del nórdico antiguo . Las lenguas germánicas orientales ahora están extintas, y el gótico es el único idioma de esta rama que sobrevive en textos escritos. Las lenguas germánicas occidentales, sin embargo, han experimentado una extensa subdivisión dialectal y ahora están representadas en idiomas modernos como el inglés, el alemán, el holandés , el yiddish , el afrikáans y otros. [17]

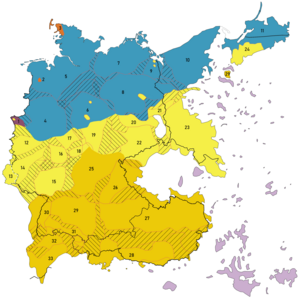

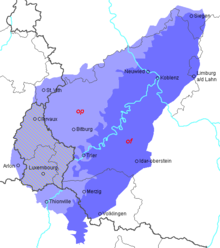

Dentro del continuo dialectal de las lenguas germánicas occidentales, las líneas Benrath y Uerdingen (que pasan por Düsseldorf - Benrath y Krefeld - Uerdingen , respectivamente) sirven para distinguir los dialectos germánicos que se vieron afectados por el cambio consonántico del alto alemán (al sur de Benrath) de los que no lo fueron (al norte de Uerdingen). Los diversos dialectos regionales hablados al sur de estas líneas se agrupan como dialectos del alto alemán , mientras que los hablados al norte comprenden los dialectos del bajo alemán y del bajo franconio . Como miembros de la familia de lenguas germánicas occidentales, se ha propuesto que el alto alemán, el bajo alemán y el bajo franconio se distingan históricamente como irminónico , ingvaeónico e istvaeónico , respectivamente. Esta clasificación indica su descendencia histórica de los dialectos hablados por los irminones (también conocidos como el grupo del Elba), los ingvaeones (o grupo germánico del Mar del Norte) y los istvaeones (o grupo del Weser-Rin). [17]

El alemán estándar se basa en una combinación de dialectos de Turingia - Alto Sajonia y Alta Franconia, que son dialectos del centro y alto alemán que pertenecen al grupo de dialectos del alto alemán . Por lo tanto, el alemán está estrechamente relacionado con las otras lenguas basadas en dialectos del alto alemán, como el luxemburgués (basado en dialectos de Franconia central ) y el yiddish . También están estrechamente relacionados con el alemán estándar los dialectos del alto alemán hablados en los países de habla alemana del sur , como el alemán suizo ( dialectos alemánicos ) y los diversos dialectos germánicos hablados en la región francesa del Gran Este , como el alsaciano (principalmente alemánico, pero también dialectos de Franconia central y alta ) y el franconio de Lorena (franconia central).

Después de estos dialectos del alto alemán, el alemán estándar está menos relacionado con las lenguas basadas en dialectos del bajo franconio (por ejemplo, holandés y afrikáans), dialectos del bajo alemán o del bajo sajón (hablados en el norte de Alemania y el sur de Dinamarca ), ninguno de los cuales experimentó el cambio consonántico del alto alemán. Como se ha señalado, el primero de estos tipos de dialectos es istvaeónico y el segundo ingvaeónico, mientras que los dialectos del alto alemán son todos irminónicos; las diferencias entre estos idiomas y el alemán estándar son, por tanto, considerables. También están relacionadas con el alemán las lenguas frisias: frisón del norte (hablado en Nordfriesland ), frisón de Saterland (hablado en Saterland ) y frisón occidental (hablado en Frisia ), así como las lenguas anglicanas del inglés y el escocés. Estos dialectos anglofrisones no participaron en el cambio consonántico del alto alemán, y las lenguas anglicanas también adoptaron mucho vocabulario tanto del nórdico antiguo como del idioma normando .

La historia del idioma alemán comienza con el cambio de consonantes del alto alemán durante el período de las migraciones , que separó los dialectos del alto alemán antiguo del sajón antiguo . Este cambio de sonido implicó un cambio drástico en la pronunciación de las consonantes oclusivas tanto sonoras como sordas ( b , d , g y p , t , k , respectivamente). Los principales efectos del cambio fueron los siguientes.

Aunque hay evidencia escrita del idioma alto alemán antiguo en varias inscripciones de futhark antiguo desde el siglo VI d. C. (como la hebilla de Pforzen ), el período del alto alemán antiguo generalmente se considera que comienza con los Abrogans (escritos c. 765-775 ), un glosario latín-alemán que proporciona más de 3000 palabras del alto alemán antiguo con sus equivalentes en latín . Después de los Abrogans , las primeras obras coherentes escritas en alto alemán antiguo aparecen en el siglo IX, siendo las principales entre ellas los Muspilli , los encantamientos de Merseburg y Hildebrandslied , y otros textos religiosos (el Georgslied , Ludwigslied , Evangelienbuch e himnos y oraciones traducidos). [19] Los Muspilli es un poema cristiano escrito en un dialecto bávaro que ofrece un relato del alma después del Juicio Final , y los encantamientos de Merseburg son transcripciones de hechizos y encantamientos de la tradición germánica pagana . Sin embargo, de particular interés para los académicos ha sido el Hildebrandslied , un poema épico secular que cuenta la historia de un padre y un hijo distanciados que sin saberlo se encuentran en batalla. Lingüísticamente, este texto es muy interesante debido al uso mixto de dialectos del antiguo sajón y del alto alemán antiguo en su composición. Las obras escritas de este período provienen principalmente de los grupos alamanes , bávaros y turingios , todos pertenecientes al grupo germánico del Elba ( Irminones ), que se habían establecido en lo que ahora es el centro-sur de Alemania y Austria entre los siglos II y VI, durante la gran migración. [18]

En general, los textos supervivientes del alto alemán antiguo (ALA) muestran una amplia gama de diversidad dialectal con muy poca uniformidad escrita. La tradición escrita temprana del ALA sobrevivió principalmente a través de monasterios y scriptoria como traducciones locales de originales latinos; como resultado, los textos supervivientes están escritos en dialectos regionales muy dispares y muestran una influencia latina significativa, particularmente en el vocabulario. [18] En ese momento, los monasterios, donde se producían la mayoría de las obras escritas, estaban dominados por el latín, y el alemán solo se usaba ocasionalmente en escritos oficiales y eclesiásticos.

Aunque no hay un acuerdo completo sobre las fechas del período del alto alemán medio (MHG), generalmente se considera que duró desde 1050 hasta 1350. [20] Este fue un período de expansión significativa del territorio geográfico ocupado por las tribus germánicas y, en consecuencia, del número de hablantes de alemán. Mientras que durante el período del alto alemán antiguo las tribus germánicas se extendieron solo hasta el este de los ríos Elba y Saale , el período del MHG vio a varias de estas tribus expandirse más allá de este límite oriental hacia el territorio eslavo (conocido como Ostsiedlung ). Con el aumento de la riqueza y la expansión geográfica de los grupos germánicos vino un mayor uso del alemán en las cortes de los nobles como el idioma estándar de los procedimientos oficiales y la literatura. [20] Un claro ejemplo de esto es el mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache empleado en la corte de Hohenstaufen en Suabia como un idioma escrito supradialectal estandarizado. Si bien estos esfuerzos todavía estaban limitados a nivel regional, el alemán comenzó a usarse en lugar del latín para ciertos propósitos oficiales, lo que generó una mayor necesidad de regularidad en las convenciones escritas.

Si bien los principales cambios del período MHG fueron socioculturales, el alto alemán aún estaba atravesando cambios lingüísticos significativos en sintaxis, fonética y morfología (por ejemplo, diptongación de ciertos sonidos vocálicos: hus (OHG y MHG "casa") → haus (regionalmente en el MHG posterior) → Haus (NHG), y debilitamiento de vocales cortas átonas a schwa [ə]: taga (OHG "días") → tage (MHG)). [21]

Del periodo MHG se conserva una gran riqueza de textos. Cabe destacar que estos textos incluyen una serie de impresionantes obras seculares, como el Nibelungenlied , un poema épico que cuenta la historia del cazador de dragones Sigfrido ( c. siglo XIII ), y el Iwein , un poema en verso artúrico de Hartmann von Aue ( c. 1203 ), poemas líricos y romances cortesanos como Parzival y Tristán . También es digno de mención el Sachsenspiegel , el primer libro de leyes escrito en bajo alemán medio ( c. 1220 ). La abundancia y especialmente el carácter secular de la literatura del periodo MHG demuestran los comienzos de una forma escrita estandarizada del alemán, así como el deseo de los poetas y autores de ser entendidos por los individuos en términos supradialectales.

En general, se considera que el período del alto alemán medio terminó cuando la Peste Negra de 1346-1353 diezmó la población de Europa. [22]

El alto alemán moderno comienza con el período del Nuevo Alto Alemán Temprano (ENHG), que Wilhelm Scherer fecha entre 1350 y 1650, y termina con el fin de la Guerra de los Treinta Años . [22] Este período vio un mayor desplazamiento del latín por el alemán como lengua principal de los procedimientos cortesanos y, cada vez más, de la literatura en los estados alemanes . Si bien estos estados todavía formaban parte del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico y estaban lejos de cualquier forma de unificación, el deseo de una lengua escrita cohesiva que fuera comprensible en los numerosos principados y reinos de habla alemana era más fuerte que nunca. Como lengua hablada, el alemán permaneció muy fracturado durante este período, con una gran cantidad de dialectos regionales a menudo incomprensibles entre sí que se hablaban en todos los estados alemanes; sin embargo, la invención de la imprenta alrededor de 1440 y la publicación de la traducción vernácula de la Biblia de Lutero en 1534 tuvieron un efecto inmenso en la estandarización del alemán como lengua escrita supradialectal.

El período ENHG vio el surgimiento de varias formas interregionales importantes de cancillería alemana, una de las cuales fue el gemeine tiutsch , utilizado en la corte del emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Maximiliano I , y la otra fue el Meißner Deutsch , utilizado en el Electorado de Sajonia en el Ducado de Sajonia-Wittenberg . [24]

Junto con estos estándares escritos cortesanos, la invención de la imprenta condujo al desarrollo de una serie de lenguajes de imprenta ( Druckersprachen ) destinados a hacer que el material impreso fuera legible y comprensible en tantos dialectos diferentes del alemán como fuera posible. [25] La mayor facilidad de producción y la mayor disponibilidad de textos escritos provocaron una mayor estandarización de la forma escrita del alemán.

Uno de los acontecimientos centrales en el desarrollo de la ENHG fue la publicación de la traducción de Lutero de la Biblia al alto alemán (el Nuevo Testamento se publicó en 1522; el Antiguo Testamento se publicó en partes y se completó en 1534). [26] Lutero basó su traducción principalmente en el Meißner Deutsch de Sajonia , y pasó mucho tiempo entre la población de Sajonia investigando el dialecto para hacer el trabajo lo más natural y accesible posible para los hablantes de alemán. Las copias de la Biblia de Lutero presentaban una larga lista de glosas para cada región, traduciendo palabras que eran desconocidas en la región al dialecto regional. Lutero dijo lo siguiente sobre su método de traducción:

Quien quiera hablar alemán no debe preguntar al latín cómo debe hacerlo; debe preguntar a la madre en el hogar, a los niños en la calle, al hombre común en el mercado y observar cuidadosamente cómo hablan, para luego traducir en consecuencia. Entonces entenderán lo que se les dice porque es alemán. Cuando Cristo dice " ex plentyia cordis os loquitur ", yo traduciría, si siguiera a los papistas, " aus dem Überflusz des Herzens redet der Mund" . Pero, díganme, ¿es esto hablar alemán? ¿Qué alemán entiende esas cosas? No, la madre en el hogar y el hombre común dirían: " Wesz das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über" . [27]

La traducción de la Biblia de Lutero al alto alemán también fue decisiva para la lengua alemana y su evolución desde el Nuevo Alto Alemán temprano hasta el alemán estándar moderno. [26] La publicación de la Biblia de Lutero fue un momento decisivo en la difusión de la alfabetización en la Alemania moderna temprana , [26] y promovió el desarrollo de formas no locales de lenguaje y expuso a todos los hablantes a formas de alemán de fuera de su propia área. [28] Con la traducción de la Biblia de Lutero en la lengua vernácula, el alemán se impuso contra el dominio del latín como lengua legítima para temas cortesanos, literarios y ahora eclesiásticos. Su Biblia era omnipresente en los estados alemanes: casi todos los hogares poseían una copia. [29] Sin embargo, incluso con la influencia de la Biblia de Lutero como estándar escrito no oficial, un estándar ampliamente aceptado para el alemán escrito no apareció hasta mediados del siglo XVIII. [30]

El alemán era la lengua comercial y gubernamental del Imperio de los Habsburgo , que abarcaba una gran zona de Europa central y oriental . Hasta mediados del siglo XIX, era esencialmente la lengua de los habitantes de las ciudades de la mayor parte del Imperio. Su uso indicaba que el hablante era un comerciante o alguien de una zona urbana, independientemente de su nacionalidad.

Praga ( ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Prag ) y Budapest ( ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Buda , ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Ofen ), por nombrar dos ejemplos, se germanizaron gradualmente en los años posteriores a su incorporación al dominio de los Habsburgo; otras, como Presburgo ( Pozsony , ahora Bratislava), se establecieron originalmente durante el período de los Habsburgo y eran principalmente alemanas en ese momento. Praga, Budapest, Bratislava y ciudades como Zagreb ( ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Agram ) o Liubliana ( ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Laibach ) contenían minorías alemanas significativas.

En las provincias orientales de Banat , Bucovina y Transilvania ( ‹Ver Tfd› en alemán: Banat, Buchenland, Siebenbürgen ), el alemán era el idioma predominante no solo en las ciudades más grandes, como Temeschburg ( Timisoara ), Hermannstadt ( Sibiu ) y Kronstadt ( Brașov ), sino también en muchas localidades más pequeñas en las áreas circundantes. [31]

En 1901, la Segunda Conferencia Ortográfica finalizó con una estandarización (casi) completa del idioma alemán estándar en su forma escrita, y el Manual Duden fue declarado su definición estándar. [32] La puntuación y la ortografía compuesta (compuestos unidos o aislados) no se estandarizaron en el proceso.

El Deutsche Bühnensprache ( lit. ' lengua alemana de teatro ' ) de Theodor Siebs había establecido convenciones para la pronunciación alemana en los teatros , [33] tres años antes; sin embargo, se trataba de un estándar artificial que no correspondía a ningún dialecto hablado tradicional. Más bien, se basaba en la pronunciación del alemán en el norte de Alemania, aunque posteriormente se consideró a menudo como una norma prescriptiva general, a pesar de las diferentes tradiciones de pronunciación, especialmente en las regiones de habla alta alemana que todavía caracterizan el dialecto del área hoy en día, especialmente la pronunciación de la terminación -ig como [ɪk] en lugar de [ɪç]. En el norte de Alemania, el alto alemán era una lengua extranjera para la mayoría de los habitantes, cuyos dialectos nativos eran subconjuntos del bajo alemán. Por lo general, solo se encontraba en la escritura o el habla formal; de hecho, la mayor parte del alto alemán era una lengua escrita, no idéntica a ningún dialecto hablado, en toda el área de habla alemana hasta bien entrado el siglo XIX. Sin embargo, durante el siglo XX se estableció una estandarización más amplia de la pronunciación a partir de los discursos públicos en teatros y medios de comunicación, que quedó documentada en diccionarios de pronunciación.

Las revisiones oficiales de algunas de las reglas de 1901 no se publicaron hasta que la controvertida reforma ortográfica alemana de 1996 se convirtió en el estándar oficial por los gobiernos de todos los países de habla alemana. [34] Los medios de comunicación y las obras escritas se producen ahora casi todos en alemán estándar, que se entiende en todas las áreas donde se habla alemán.

Distribución aproximada de hablantes nativos de alemán (suponiendo un total redondeado de 95 millones) en todo el mundo:

Como resultado de la diáspora alemana , así como de la popularidad del alemán enseñado como lengua extranjera , [35] [36] la distribución geográfica de los hablantes de alemán (o "germanófonos") abarca todos los continentes habitados.

Sin embargo, la determinación de un número exacto y global de hablantes nativos de alemán se complica por la existencia de varias variedades cuyo estatus como "lenguas" o "dialectos" separados se disputa por razones políticas y lingüísticas, incluidas variedades cuantitativamente fuertes como ciertas formas de alemánico y bajo alemán . [9] Con la inclusión o exclusión de ciertas variedades, se estima que aproximadamente entre 90 y 95 millones de personas hablan alemán como primera lengua , [37] [ página necesaria ] [38] entre 10 y 25 millones lo hablan como segunda lengua , [37] [ página necesaria ] y entre 75 y 100 millones como lengua extranjera . [2] Esto implicaría la existencia de aproximadamente entre 175 y 220 millones de hablantes de alemán en todo el mundo. [39]

El sociolingüista alemán Ulrich Ammon estimó el número de hablantes de alemán como lengua extranjera en 289 millones, sin aclarar los criterios con los que clasificaba a los hablantes. [40]

En 2012 [update], alrededor de 90 millones de personas, o el 16% de la población de la Unión Europea , hablaban alemán como lengua materna, lo que lo convierte en el segundo idioma más hablado en el continente después del ruso y el segundo idioma más grande en términos de hablantes en general (después del inglés), así como el idioma nativo más hablado. [2]

La zona de Europa central en la que la mayoría de la población habla alemán como primera lengua y tiene el alemán como lengua (co)oficial se denomina "German Sprachraum ". El alemán es el idioma oficial de los siguientes países:

El alemán es lengua cooficial de los siguientes países:

Aunque las expulsiones y la asimilación (forzada) después de las dos guerras mundiales las redujeron considerablemente, en áreas adyacentes y separadas del Sprachraum existen comunidades minoritarias de hablantes nativos de alemán, en su mayoría bilingües.

Dentro de Europa, el alemán es una lengua minoritaria reconocida en los siguientes países: [41]

En Francia, las variedades del alto alemán del alsaciano y del franconio del Mosela se consideran « lenguas regionales », pero la Carta Europea de las Lenguas Regionales o Minoritarias de 1998 aún no ha sido ratificada por el gobierno. [44]

Namibia también fue una colonia del Imperio alemán, desde 1884 hasta 1915. Alrededor de 30.000 personas todavía hablan alemán como lengua materna en la actualidad, en su mayoría descendientes de colonos alemanes . [45] El período del colonialismo alemán en Namibia también condujo a la evolución de una lengua pidgin basada en el alemán estándar llamada " alemán negro de Namibia ", que se convirtió en una segunda lengua para partes de la población indígena. Aunque está casi extinto en la actualidad, algunos namibios mayores aún tienen algún conocimiento de él. [46]

El alemán siguió siendo un idioma oficial de facto de Namibia después del fin del dominio colonial alemán junto con el inglés y el afrikáans , y tuvo un estatus cooficial de iure desde 1984 hasta su independencia de Sudáfrica en 1990. Sin embargo, el gobierno de Namibia percibió el afrikáans y el alemán como símbolos del apartheid y el colonialismo, y decidió que el inglés sería el único idioma oficial tras la independencia, afirmando que era un idioma "neutral" ya que prácticamente no había hablantes nativos de inglés en Namibia en ese momento. [45] El alemán, el afrikáans y varias lenguas indígenas se convirtieron así en "idiomas nacionales" por ley, identificándolos como elementos del patrimonio cultural de la nación y asegurando que el estado reconociera y apoyara su presencia en el país.

En la actualidad, Namibia se considera el único país de habla alemana fuera del Sprachraum en Europa. [47] El alemán se utiliza en una amplia variedad de ámbitos en todo el país, especialmente en los negocios, el turismo y la señalización pública, así como en la educación, las iglesias (sobre todo la Iglesia Evangélica Luterana de habla alemana en Namibia (GELK) ), otras esferas culturales como la música y los medios de comunicación (como los programas de radio en alemán de la Namibian Broadcasting Corporation ). El Allgemeine Zeitung es uno de los tres periódicos más importantes de Namibia y el único diario en alemán de África. [45]

An estimated 12,000 people speak German or a German variety as a first language in South Africa, mostly originating from different waves of immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries.[48] One of the largest communities consists of the speakers of "Nataler Deutsch",[49] a variety of Low German concentrated in and around Wartburg. The South African constitution identifies German as a "commonly used" language and the Pan South African Language Board is obligated to promote and ensure respect for it.[50]

Cameroon was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916. However, German was replaced by French and English, the languages of the two successor colonial powers, after its loss in World War I. Nevertheless since the 21st century, German has become a popular foreign language among pupils and students, with 300,000 people learning or speaking German in Cameroon in 2010 and over 230,000 in 2020.[51] Today Cameroon is one of the African countries outside Namibia with the highest number of people learning German.[52]

In the United States, German is the fifth most spoken language in terms of native and second language speakers after English, Spanish, French, and Chinese (with figures for Cantonese and Mandarin combined), with over 1 million total speakers.[53] In the states of North Dakota and South Dakota, German is the most common language spoken at home after English.[54] As a legacy of significant German immigration to the country, German geographical names can be found throughout the Midwest region, such as New Ulm and Bismarck (North Dakota's state capital), plus many other regions.[55]

A number of German varieties have developed in the country and are still spoken today, such as Pennsylvania Dutch and Texas German.

In Brazil, the largest concentrations of German speakers are in the states of Rio Grande do Sul (where Riograndenser Hunsrückisch developed), Santa Catarina, and Espírito Santo.[56]

German dialects (namely Hunsrik and East Pomeranian) are recognized languages in the following municipalities in Brazil:

In Chile, during the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a massive immigration of Germans, Swiss and Austrians. Because of that, two dialects of German emerged, Lagunen-Deutsch and Chiloten-Deutsch.[59] Immigrants even founded prosperous cities and towns. The impact of nineteenth century German immigration to southern Chile was such that Valdivia was for a while a Spanish-German bilingual city with "German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish".[60] Currently, German and its dialects are spoken in many cities, towns and rural areas of southern Chile, such as Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Puerto Varas, Frutillar, Nueva Braunau, Castro, Ancud, among many others.

Small concentrations of German-speakers and their descendants are also found in Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, and Bolivia.[48]

In Australia, the state of South Australia experienced a pronounced wave of Prussian immigration in the 1840s (particularly from Silesia region). With the prolonged isolation from other German speakers and contact with Australian English, a unique dialect known as Barossa German developed, spoken predominantly in the Barossa Valley near Adelaide. Usage of German sharply declined with the advent of World War I, due to the prevailing anti-German sentiment in the population and related government action. It continued to be used as a first language into the 20th century, but its use is now limited to a few older speakers.[61]

As of the 2013 census, 36,642 people in New Zealand spoke German, mostly descendants of a small wave of 19th century German immigrants, making it the third most spoken European language after English and French and overall the ninth most spoken language.[62]

A German creole named Unserdeutsch was historically spoken in the former German colony of German New Guinea, modern day Papua New Guinea. It is at a high risk of extinction, with only about 100 speakers remaining, and a topic of interest among linguists seeking to revive interest in the language.[63]

Like English, French, and Spanish, German has become a standard foreign language throughout the world, especially in the Western World.[2][64] German ranks second on par with French among the best known foreign languages in the European Union (EU) after English,[2] as well as in Russia,[65] and Turkey.[2] In terms of student numbers across all levels of education, German ranks third in the EU (after English and French)[36] and in the United States (after Spanish and French).[35][66] In British schools, where learning a foreign language is not mandatory, a dramatic decline in entries for German A-Level has been observed.[67] In 2020, approximately 15.4 million people were enrolled in learning German across all levels of education worldwide. This number has decreased from a peak of 20.1 million in 2000.[68] Within the EU, not counting countries where it is an official language, German as a foreign language is most popular in Eastern and Northern Europe, namely the Czech Republic, Croatia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Sweden, Poland, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2][69] German was once, and to some extent still is, a lingua franca in those parts of Europe.[70]

A visible sign of the geographical extension of the German language is the German-language media outside the German-speaking countries. German is the second most commonly used scientific language[71][better source needed] as well as the third most widely used language on websites after English and Russian.[72]

Deutsche Welle (German pronunciation: [ˈdɔʏtʃə ˈvɛlə]; "German Wave" in German), or DW, is Germany's public international broadcaster. The service is available in 30 languages. DW's satellite television service consists of channels in German, English, Spanish, and Arabic.

German-speaking people living abroad (and people wanting to learn German) can visit the websites of German-language newspapers and TV- and radio stations. The free software MediathekView allows the downloading of videos from the websites of some public German, Austrian, and Swiss TV stations and of the public Franco-German TV network ARTE. With the webpage "onlinetvrecorder.com", it is possible to record programs of many German and some international TV stations.

Note that some material is region-restricted for legal reasons and cannot be accessed from everywhere in the world. Some websites have a paywall or limit the access for free/unregistered users.

See also:

The basis of Standard German developed with the Luther Bible and the chancery language spoken by the Saxon court, part of the regional High German group.[73] However, there are places where the traditional regional dialects have been replaced by new vernaculars based on Standard German; that is the case in large stretches of Northern Germany but also in major cities in other parts of the country. It is important to note, however, that the colloquial Standard German differs from the formal written language, especially in grammar and syntax, in which it has been influenced by dialectal speech.

Standard German differs regionally among German-speaking countries in vocabulary and some instances of pronunciation and even grammar and orthography. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local dialects. Even though the national varieties of Standard German are only somewhat influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a pluricentric language, with currently three national standard varieties of German: Standard German German, Standard Austrian German and Standard Swiss German. In comparison to other European languages (e.g. Portuguese, English), the multi-standard character of German is still not widely acknowledged.[74] However, 90% of Austrian secondary school teachers of German consider German as having "more than one" standard variety.[75] In this context, some scholars speak of a One Standard German Axiom that has been maintained as a core assumption of German dialectology.[76]

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum, e.g. "Umgangssprache" (colloquial standards) from more dialectal varieties to more standard varieties depending on the circumstances.

In German linguistics, German dialects are distinguished from varieties of Standard German. The varieties of Standard German refer to the different local varieties of the pluricentric German. They differ mainly in lexicon and phonology, but also smaller grammatical differences. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially in Northern Germany.

In the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of Standard German is largely restricted to the written language. About 11% of the Swiss residents speak Standard German at home, but this is mainly due to German immigrants.[78] This situation has been called a medial diglossia. Swiss Standard German is used in the Swiss education system, while Austrian German is officially used in the Austrian education system.

The German dialects are the traditional local varieties of the language; many of them are not mutually intelligible with standard German, and they have great differences in lexicon, phonology, and syntax. If a narrow definition of language based on mutual intelligibility is used, many German dialects are considered to be separate languages (for instance by ISO 639-3). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics.

The German dialect continuum is traditionally divided most broadly into High German and Low German, also called Low Saxon. However, historically, High German dialects and Low Saxon/Low German dialects do not belong to the same language. Nevertheless, in today's Germany, Low Saxon/Low German is often perceived as a dialectal variation of Standard German on a functional level even by many native speakers.

The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with often only neighbouring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who know only Standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the dialect continuum of High German and Low Saxon.

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany until the 16th century. In 1534, the Luther Bible was published. It aimed to be understandable to a broad audience and was based mainly on Central and Upper German varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low German and became the language of science and literature. Around the same time, the Hanseatic League, a confederation of northern ports, lost its importance as new trade routes to Asia and the Americas were established, and the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany.

The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass education in Standard German in schools. Gradually, Low German came to be politically viewed as a mere dialect spoken by the uneducated. The proportion of the population who can understand and speak it has decreased continuously since World War II.

The Low Franconian dialects fall within a linguistic category used to classify a number of historical and contemporary West Germanic varieties most closely related to, and including, the Dutch language. Consequently, the vast majority of the Low Franconian dialects are spoken outside of the German language area. Low Franconian dialects are spoken in the Netherlands, Belgium, South Africa, Suriname and Namibia, and along the Lower Rhine in Germany, in North Rhine-Westphalia. The region in Germany encompasses parts of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region and of the Ruhr.

The Low Franconian dialects have three different standard varieties: In the Netherlands, Belgium and Suriname, it is Dutch, which is itself a Low Franconian language. In South Africa, it is Afrikaans, which is also categorized as Low Franconian. During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, the Low Franconian dialects now spoken in Germany, used Middle Dutch or Early Modern Dutch as their literary language and Dachsprache. Following a 19th-century change in Prussian language policy, use of Dutch as an official and public language was forbidden; resulting in Standard German taking its place as the region's official language.[79][80] As a result, these dialects are now considered German dialects from a socio-linguistic point of view.[81]

The Low Franconian dialects in Germany are divided by the Uerdingen line (north of which "i" is pronounced as "ik" and south of which as "ich") into northern and southern Low Franconian. The northern variants comprise Kleverlandish, which is most similar to Standard Dutch. The other ones are transitional between Low Franconian and Ripuarian, but closer to Low Franconian.

* city with German as standard language

The High German dialects consist of the Central German, High Franconian and Upper German dialects. The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central and Upper German. The High German varieties spoken by the Ashkenazi Jews have several unique features and are considered as a separate language, Yiddish, written with the Hebrew alphabet.

The Central German dialects are spoken in Central Germany, from Aachen in the west to Görlitz in the east. Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German dialects.

The West Central German dialects are the Central Franconian dialects (Ripuarian and Moselle Franconian) and the Rhenish Franconian dialects (Hessian and Palatine). These dialects are considered as

Luxembourgish as well as Transylvanian Saxon and Banat Swabian are based on Moselle Franconian dialects.

Further east, the non-Franconian, East Central German dialects are spoken (Thuringian, Upper Saxon, Erzgebirgisch (dialect of the Ore Mountains) and North Upper Saxon–South Markish, and earlier, in the then German-speaking parts of Silesia also Silesian, and in then German southern East Prussia also High Prussian).

The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central and Upper German. They consist of the East and South Franconian dialects.

The East Franconian dialects are spoken in the region of Franconia. Franconia consists of the Bavarian districts of Upper, Middle, and Lower Franconia, the region of South Thuringia (those parts of Thuringia south of the Thuringian Forest), and the eastern parts of the region of Heilbronn-Franken (Tauber Franconia and Hohenlohe) in northeastern Baden-Württemberg. East Franconian is also spoken in most parts of Saxon Vogtland (in the Vogtland District around Plauen, Reichenbach im Vogtland, Auerbach/Vogtl., Oelsnitz/Vogtl. and Klingenthal). East Franconian is colloquially referred to as "Fränkisch" (Franconian) in Franconia (including Bavarian Vogtland), and as "Vogtländisch" (Vogtlandian) in Saxon Vogtland.

South Franconian is spoken in northern Baden-Württemberg and in the northeasternmost tip of Alsace (around Wissembourg) in France. In Baden-Württemberg, they are considered dialects of German, and in Alsace a South Franconian variant of Alsatian.

The Upper German dialects are the Alemannic and Swabian dialects in the west and the Austro-Bavarian dialects in the east.

.jpg/440px-Andermatt_-_Schwiizerdütsch_(15922347261).jpg)

Alemannic dialects are spoken in Switzerland (High Alemannic in the densely populated Swiss Plateau including Zürich and Bern, in the south also Highest Alemannic, and Low Alemannic in Basel), Baden-Württemberg (Swabian and Low Alemannic, in the southwest also High Alemannic), Bavarian Swabia (Swabian, in the southwesternmost part also Low Alemannic), Vorarlberg/Austria (Low, High, and Highest Alemannic), Alsace/France (Low Alemannic, in the southernmost part also High Alemannic), Liechtenstein (High and Highest Alemannic), and in the district of Reutte in Tyrol, Austria (Swabian). The Alemannic dialects are considered

In Germany, the Alemannic dialects are often referred to as Swabian in Bavarian Swabia and in the historical region of Württemberg, and as Badian in the historical region of Baden.

The southernmost German-speaking municipality is in the Alemannic region: Zermatt in the Canton of Valais, Switzerland, as is the capital of Liechtenstein: Vaduz.

The Austro-Bavarian dialects are spoken in Austria (Vienna, Lower and Upper Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Salzburg, Burgenland, and in most parts of Tyrol), southern and eastern Bavaria (Upper and Lower Bavaria as well as Upper Palatinate), and South Tyrol. Austro-Bavarian is also spoken in southwesternmost Saxony: in the southernmost tip of Vogtland (in the Vogtland District around Adorf, Bad Brambach, Bad Elster and Markneukirchen), where it is referred to as Vogtländisch (Vogtlandian), just like the East Franconian variant that dominates in Vogtland. There is also one single Austro-Bavarian village in Switzerland: Samnaun in the Canton of the Grisons.

The northernmost Austro-Bavarian village is Breitenfeld (municipality of Markneukirchen, Saxony), the southernmost village is Salorno sulla Strada del Vino (German: Salurn an der Weinstraße), South Tyrol.

German is a fusional language with a moderate degree of inflection, with three grammatical genders; as such, there can be a large number of words derived from the same root.

German nouns inflect by case, gender, and number:

This degree of inflection is considerably less than in Old High German and other old Indo-European languages such as Latin, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit, and it is also somewhat less than, for instance, Old English, modern Icelandic, or Russian. The three genders have collapsed in the plural. With four cases and three genders plus plural, there are 16 permutations of case and gender/number of the article (not the nouns), but there are only six forms of the definite article, which together cover all 16 permutations. In nouns, inflection for case is required in the singular for strong masculine and neuter nouns only in the genitive and in the dative (only in fixed or archaic expressions), and even this is losing ground to substitutes in informal speech.[82] Weak masculine nouns share a common case ending for genitive, dative, and accusative in the singular. Feminine nouns are not declined in the singular. The plural has an inflection for the dative. In total, seven inflectional endings (not counting plural markers) exist in German: -s, -es, -n, -ns, -en, -ens, -e.

Like the other Germanic languages, German forms noun compounds in which the first noun modifies the category given by the second: Hundehütte ("dog hut"; specifically: "dog kennel"). Unlike English, whose newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written "open" with separating spaces, German (like some other Germanic languages) nearly always uses the "closed" form without spaces, for example: Baumhaus ("tree house"). Like English, German allows arbitrarily long compounds in theory (see also English compounds). The longest German word verified to be actually in (albeit very limited) use is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz, which, literally translated, is "beef labelling supervision duties assignment law" [from Rind (cattle), Fleisch (meat), Etikettierung(s) (labelling), Überwachung(s) (supervision), Aufgaben (duties), Übertragung(s) (assignment), Gesetz (law)]. However, examples like this are perceived by native speakers as excessively bureaucratic, stylistically awkward, or even satirical. On the other hand, even this compound could be expanded by any native speaker.

The inflection of standard German verbs includes:

The meaning of basic verbs can be expanded and sometimes radically changed through the use of a number of prefixes. Some prefixes have a specific meaning; the prefix zer- refers to destruction, as in zerreißen (to tear apart), zerbrechen (to break apart), zerschneiden (to cut apart). Other prefixes have only the vaguest meaning in themselves; ver- is found in a number of verbs with a large variety of meanings, as in versuchen (to try) from suchen (to seek), vernehmen (to interrogate) from nehmen (to take), verteilen (to distribute) from teilen (to share), verstehen (to understand) from stehen (to stand).

Other examples include the following:haften (to stick), verhaften (to detain); kaufen (to buy), verkaufen (to sell); hören (to hear), aufhören (to cease); fahren (to drive), erfahren (to experience).

Many German verbs have a separable prefix, often with an adverbial function. In finite verb forms, it is split off and moved to the end of the clause and is hence considered by some to be a "resultative particle". For example, mitgehen, meaning "to go along", would be split, giving Gehen Sie mit? (Literal: "Go you with?"; Idiomatic: "Are you going along?").

Indeed, several parenthetical clauses may occur between the prefix of a finite verb and its complement (ankommen = to arrive, er kam an = he arrived, er ist angekommen = he has arrived):

A selectively literal translation of this example to illustrate the point might look like this:

German word order is generally with the V2 word order restriction and also with the SOV word order restriction for main clauses. For yes–no questions, exclamations, and wishes, the finite verb always has the first position. In subordinate clauses, all verb forms occur at the very end.

German requires a verbal element (main verb, modal verb or auxiliary verb as finite verb) to appear second in the sentence. The verb is preceded by the topic of the sentence. The element in focus appears at the end of the sentence. For a sentence without an auxiliary, these are several possibilities:

The position of a noun in a German sentence has no bearing on its being a subject, an object or another argument. In a declarative sentence in English, if the subject does not occur before the predicate, the sentence could well be misunderstood.

However, German's flexible word order allows one to emphasise specific words:

Normal word order:

Second variant in normal word order:

Object in front:

Adverb of time in front:

Both time expressions in front:

Another possibility:

Swapped adverbs:

Swapped object:

The flexible word order also allows one to use language "tools" (such as poetic meter and figures of speech) more freely.

When an auxiliary verb is present, it appears in second position, and the main verb appears at the end. This occurs notably in the creation of the perfect tense. Many word orders are still possible:

The main verb may appear in first position to put stress on the action itself. The auxiliary verb is still in second position.

Sentences using modal verbs as finite verbs place the infinitive at the end. For example, the English sentence "Should he go home?" would be rearranged in German to say "Should he (to) home go?" (Soll er nach Hause gehen?). Thus, in sentences with several subordinate or relative clauses, the infinitives are clustered at the end. Compare the similar clustering of prepositions in the following (highly contrived) English sentence: "What did you bring that book that I do not like to be read to out of up for?"

German subordinate clauses have all verbs clustered at the end, with the finite verb normally in the final position of the cluster. Given that auxiliaries encode future, passive, modality, and the perfect, very long chains of verbs at the end of the sentence can occur. In these constructions, the past participle formed with ge- is often replaced by the infinitive.

The order at the end of such strings is subject to variation, but the second one in the last example is unusual.

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.[83] However, there is a significant amount of loanwords from other languages, in particular Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and most recently English.[84] In the early 19th century, Joachim Heinrich Campe estimated that one fifth of the total German vocabulary was of French or Latin origin.[85]

Latin words were already imported into the predecessor of the German language during the Roman Empire and underwent all the characteristic phonetic changes in German. Their origin is thus no longer recognizable for most speakers (e.g. Pforte, Tafel, Mauer, Käse, Köln from Latin porta, tabula, murus, caseus, Colonia). Borrowing from Latin continued after the fall of the Roman Empire during Christianisation, mediated by the church and monasteries. Another important influx of Latin words can be observed during Renaissance humanism. In a scholarly context, the borrowings from Latin have continued until today, in the last few decades often indirectly through borrowings from English. During the 15th to 17th centuries, the influence of Italian was great, leading to many Italian loanwords in the fields of architecture, finance and music. The influence of the French language in the 17th to 19th centuries resulted in an even greater import of French words. The English influence was already present in the 19th century, but it did not become dominant until the second half of the 20th century.

Thus, Notker Labeo translated the Aristotelian treatises into pure (Old High) German in the decades after the year 1000.[86] The tradition of loan translation revitalized in the 17th and 18th century with poets like Philipp von Zesen or linguists like Joachim Heinrich Campe, who introduced close to 300 words, which are still used in modern German. Even today, there are movements that promote the substitution of foreign words that are deemed unnecessary with German alternatives.[87]

As in English, there are many pairs of synonyms due to the enrichment of the Germanic vocabulary with loanwords from Latin and Latinized Greek. These words often have different connotations from their Germanic counterparts and are usually perceived as more scholarly.

The size of the vocabulary of German is difficult to estimate. The Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary), initiated by the Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm) and the most comprehensive guide to the vocabulary of the German language, already contained over 330,000 headwords in its first edition. The modern German scientific vocabulary is estimated at nine million words and word groups (based on the analysis of 35 million sentences of a corpus in Leipzig, which as of July 2003 included 500 million words in total).[88]

Written texts in German are easily recognisable as such by distinguishing features such as umlauts and certain orthographical features, such as the capitalization of all nouns, and the frequent occurrence of long compounds. Because legibility and convenience set certain boundaries, compounds consisting of more than three or four nouns are almost exclusively found in humorous contexts. (English also can string nouns together, though it usually separates the nouns with spaces: as, for example, "toilet bowl cleaner".)

In German orthography, nouns are capitalized, which makes it easier for readers to determine the function of a word within a sentence. This convention is almost unique to German today (shared perhaps only by the closely related Luxembourgish language and several insular dialects of the North Frisian language), but it was historically common in Northern Europe in the early modern era, including in languages such as Danish which abolished the capitalization of nouns in 1948, and English for a while, into the 1700s.

Before the German orthography reform of 1996, ß replaced ss after long vowels and diphthongs and before consonants, word-, or partial-word endings. In reformed spelling, ß replaces ss only after long vowels and diphthongs.

Since there is no traditional capital form of ß, it was replaced by SS (or SZ) when capitalization was required. For example, Maßband (tape measure) became MASSBAND in capitals. An exception was the use of ß in legal documents and forms when capitalizing names. To avoid confusion with similar names, lower case ß was sometimes maintained (thus "KREßLEIN" instead of "KRESSLEIN"). Capital ß (ẞ) was ultimately adopted into German orthography in 2017, ending a long orthographic debate (thus "KREẞLEIN and KRESSLEIN").[89]

Umlaut vowels (ä, ö, ü) are commonly transcribed with ae, oe, and ue if the umlauts are not available on the keyboard or other medium used. In the same manner, ß can be transcribed as ss. Some operating systems use key sequences to extend the set of possible characters to include, amongst other things, umlauts; in Microsoft Windows this is done using Alt codes. German readers understand these transcriptions (although they appear unusual), but they are avoided if the regular umlauts are available, because they are a makeshift and not proper spelling. (In Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein, city and family names exist where the extra e has a vowel lengthening effect, e.g. Raesfeld [ˈraːsfɛlt], Coesfeld [ˈkoːsfɛlt] and Itzehoe [ɪtsəˈhoː], but this use of the letter e after a/o/u does not occur in the present-day spelling of words other than proper nouns.)

There is no general agreement on where letters with umlauts occur in the sorting sequence. Telephone directories treat them by replacing them with the base vowel followed by an e. Some dictionaries sort each umlauted vowel as a separate letter after the base vowel, but more commonly words with umlauts are ordered immediately after the same word without umlauts. As an example in a telephone book Ärzte occurs after Adressenverlage but before Anlagenbauer (because Ä is replaced by Ae). In a dictionary Ärzte comes after Arzt, but in some dictionaries Ärzte and all other words starting with Ä may occur after all words starting with A. In some older dictionaries or indexes, initial Sch and St are treated as separate letters and are listed as separate entries after S, but they are usually treated as S+C+H and S+T.

Written German also typically uses an alternative opening inverted comma (quotation mark) as in „Guten Morgen!“.

Until the early 20th century, German was printed in blackletter typefaces (in Fraktur, and in Schwabacher), and written in corresponding handwriting (for example Kurrent and Sütterlin). These variants of the Latin alphabet are very different from the serif or sans-serif Antiqua typefaces used today, and the handwritten forms in particular are difficult for the untrained to read. The printed forms, however, were claimed by some to be more readable when used for Germanic languages.[90] The Nazis initially promoted Fraktur and Schwabacher because they were considered Aryan, but they abolished them in 1941, claiming that these letters were Jewish.[91] It is believed that this script was banned during the Nazi régime,[who?] as they realized that Fraktur would inhibit communication in the territories occupied during World War II.[92]

The Fraktur script however remains present in everyday life in pub signs, beer brands and other forms of advertisement, where it is used to convey a certain rusticality and antiquity.

A proper use of the long s (langes s), ſ, is essential for writing German text in Fraktur typefaces. Many Antiqua typefaces also include the long s. A specific set of rules applies for the use of long s in German text, but nowadays it is rarely used in Antiqua typesetting. Any lower case "s" at the beginning of a syllable would be a long s, as opposed to a terminal s or short s (the more common variation of the letter s), which marks the end of a syllable; for example, in differentiating between the words Wachſtube (guard-house) and Wachstube (tube of polish/wax). One can easily decide which "s" to use by appropriate hyphenation, (Wach-ſtube vs. Wachs-tube). The long s only appears in lower case.

German does not have any dental fricatives (the category containing English ⟨th⟩). All of the ⟨th⟩ sounds, which the English language still has, disappeared on the continent in German with the consonant shifts between the 8th and 10th centuries.[93] It is sometimes possible to find parallels between English and German by replacing the English ⟨th⟩ with ⟨d⟩ in German, e.g. "thank" → Dank, "this" and "that" → dies and das, "thou" (old 2nd person singular pronoun) → du, "think" → denken, "thirsty" → durstig, etc.

Likewise, the ⟨gh⟩ in Germanic English words, pronounced in several different ways in modern English (as an ⟨f⟩ or not at all), can often be linked to German ⟨ch⟩, e.g. "to laugh" → lachen, "through" → durch, "high" → hoch, "naught" → nichts, "light" → leicht or Licht, "sight" → Sicht, "daughter" → Tochter, "neighbour" → Nachbar. This is due to the fact that English ⟨gh⟩ was historically pronounced in the same way as German ⟨ch⟩ (as /x/ and /ç/ in an allophonic relationship, or potentially as /x/ in all circumstances as in modern Dutch) with these word pairs originally (up until around the mid to late 16th century) sounding far more similar than they do today.

The German language is used in German literature and can be traced back to the Middle Ages, with the most notable authors of the period being Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach. The Nibelungenlied, whose author remains unknown, is also an important work of the epoch. The fairy tales collected and published by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the 19th century became famous throughout the world.

Reformer and theologian Martin Luther, who translated the Bible into High German (a regional group or German varieties at southern and therefore higher regions), is widely credited for attibuted to the basis for the modern Standard German language. Among the best-known poets and authors in German are Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Kleist, Hoffmann, Brecht, Heine and Kafka. Fourteen German-speaking people have won the Nobel Prize in literature: Theodor Mommsen, Rudolf Christoph Eucken, Paul von Heyse, Gerhart Hauptmann, Carl Spitteler, Thomas Mann, Nelly Sachs, Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll, Elias Canetti, Günter Grass, Elfriede Jelinek, Herta Müller and Peter Handke, making it the second most awarded linguistic region (together with French) after English.

Native speakers=105, total speakers=185

According to the council's 2017 spelling manual: When writing the uppercase [of ß], write SS. It's also possible to use the uppercase ẞ. Example: Straße – STRASSE – STRAẞE.

Facsimile of Bormann's Memorandum

The memorandum itself is typed in Antiqua, but the NSDAP letterhead is printed in Fraktur.

"For general attention, on behalf of the Führer, I make the following announcement:

It is wrong to regard or to describe the so-called Gothic script as a German script. In reality, the so-called Gothic script consists of Schwabach Jew letters. Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.

Today the Führer, talking with Herr Reichsleiter Amann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script. All printed materials are to be gradually converted to this normal script. As soon as is feasible in terms of textbooks, only the normal script will be taught in village and state schools.

The use of the Schwabach Jew letters by officials will in future cease; appointment certifications for functionaries, street signs, and so forth will in future be produced only in normal script.

On behalf of the Führer, Herr Reichsleiter Amann will in future convert those newspapers and periodicals that already have foreign distribution, or whose foreign distribution is desired, to normal script.

Sum of Standard German, Swiss German, and all German dialects not listed under "Standard German".

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)