La dinastía almorávide ( árabe : المرابطون , romanizado : Al-Murābiṭūn , lit. 'los de los ribats ' [11] ) fue una dinastía musulmana bereber centrada en el territorio del actual Marruecos . [12] [13] Estableció un imperio que se extendió por el Magreb occidental y Al-Ándalus , comenzando en la década de 1050 y durando hasta su caída ante los almohades en 1147. [14]

Los almorávides surgieron de una coalición de los lamtuna , gudala y massufa, tribus nómadas bereberes que vivían en lo que hoy es Mauritania y el Sahara Occidental , [15] [16] atravesando el territorio entre los ríos Draa , Níger y Senegal . [17] [18] Durante su expansión hacia el Magreb, fundaron la ciudad de Marrakech como capital, c. 1070. Poco después de esto, el imperio se dividió en dos ramas: una norteña centrada en el Magreb, liderada por Yusuf ibn Tashfin y sus descendientes, y una meridional con base en el Sahara, liderada por Abu Bakr ibn Umar y sus descendientes. [15]

Los almorávides expandieron su control a al-Andalus (los territorios musulmanes en Iberia ) y fueron cruciales para detener temporalmente el avance de los reinos cristianos en esta región, con la batalla de Sagrajas en 1086 entre sus victorias distintivas. [19] Esto unió al Magreb y al-Andalus políticamente por primera vez [20] y transformó a los almorávides en el primer gran imperio islámico liderado por bereberes en el Mediterráneo occidental. [21] Sus gobernantes nunca reclamaron el título de califa y en su lugar asumieron el título de Amir al-Muslimīn ("Príncipe de los musulmanes") al tiempo que reconocían formalmente el señorío de los califas abasíes en Bagdad . [22] El período almorávide también contribuyó significativamente a la islamización de la región del Sahara y a la urbanización del Magreb occidental, mientras que los desarrollos culturales fueron estimulados por el aumento del contacto entre al-Andalus y África. [20] [23]

Tras un breve apogeo, el poder almorávide en al-Andalus comenzó a declinar tras la pérdida de Zaragoza en 1118. [24] La causa final de su caída fue la rebelión almohade liderada por Masmuda iniciada en el Magreb por Ibn Tumart en la década de 1120. El último gobernante almorávide, Ishaq ibn Ali , fue asesinado cuando los almohades capturaron Marrakech en 1147 y se establecieron como la nueva potencia dominante tanto en el norte de África como en al-Andalus. [25]

El término «almorávide» proviene del árabe « al-Murabit » ( المرابط ), pasando por el español : almorávide . [26] La transformación de la b de « al-Murabit » a la v de almorávide es un ejemplo de betacismo en español.

En árabe, " al-Murabit " significa literalmente "el que está atando", pero en sentido figurado significa "el que está listo para la batalla en una fortaleza". El término está relacionado con la noción de ribat رِباط , un monasterio-fortaleza fronterizo del norte de África, a través de la raíz rbt ( ربط " rabat ": atar, unir o رابط " raabat ": acampar ). [27] [28]

El nombre de "almorávide" estaba vinculado a una escuela de derecho malikita llamada "Dar al-Murabitin", fundada en Sus al-Aqsa , en el actual Marruecos , por un erudito llamado Waggag ibn Zallu . Ibn Zallu envió a su alumno Abdallah ibn Yasin a predicar el Islam malikita a los bereberes Sanhaja de Adrar (actual Mauritania ). Por lo tanto, el nombre de los almorávides proviene de los seguidores de Dar al-Murabitin, "la casa de los que estaban unidos en la causa de Dios". [29]

No se sabe exactamente cuándo o por qué los almorávides adquirieron ese apelativo. Al-Bakri , escribiendo en 1068, antes de su apogeo, ya los llama al -Murabitun , pero no aclara las razones de ello. Escribiendo tres siglos después, Ibn Abi Zar sugirió que fue elegido tempranamente por Abdallah ibn Yasin [30] porque, al encontrar resistencia entre los bereberes gudala de Adrar (Mauritania) a su enseñanza, tomó un puñado de seguidores para erigir un ribat improvisado (monasterio-fortaleza) en una isla costera (posiblemente la isla de Tidra , en la bahía de Arguin ). [31] Ibn 'Idhari escribió que el nombre fue sugerido por Ibn Yasin en el sentido de "perseverar en la lucha", para levantar la moral después de una batalla particularmente dura en el valle del Draa c. 1054 , en la que habían sufrido muchas pérdidas. [ cita requerida ] Cualquiera que sea la explicación verdadera, parece seguro que los almorávides eligieron la denominación para sí mismos, en parte con el objetivo consciente de evitar cualquier identificación tribal o étnica. [ cita requerida ]

El nombre podría estar relacionado con el ribat de Waggag ibn Zallu en el pueblo de Aglu (cerca de la actual Tiznit ), donde el futuro líder espiritual almorávide Abdallah ibn Yasin recibió su formación inicial. El biógrafo marroquí del siglo XIII Ibn al-Zayyat al-Tadili , y Qadi Ayyad antes que él en el siglo XII, señalan que el centro de aprendizaje de Waggag se llamaba Dar al-Murabitin (La casa de los almorávides), y que eso podría haber inspirado la elección del nombre de Ibn Yasin para el movimiento. [32] [33]

Los almorávides, a veces llamados «al-mulathamun» («los velados», de litham , árabe para « velo »). [36] remontan sus orígenes a varias tribus nómadas saharianas sanhaja , que habitaban en un área que se extiende entre el río Senegal en el sur y el río Draa en el norte. [37] La primera y principal tribu fundadora almorávide fue la lamtuna . [38] Ocupaba la región alrededor de Awdaghust (Aoudaghost) en el sur del Sahara según cronistas árabes contemporáneos como al-Ya'qubi , al-Bakri e Ibn Hawqal . [39] [40] Según el historiador francés Charles-André Julien : «La célula original del imperio almorávide era una poderosa tribu sanhaja del Sahara, la lamtuna, cuyo lugar de origen estaba en el Adrar en Mauritania ». [36] Se cree que el pueblo tuareg es su descendiente. [37] [41]

Estos nómadas se habían convertido al Islam en el siglo IX. [36] Posteriormente se unieron en el siglo X y, con el celo de los nuevos conversos, lanzaron varias campañas contra los " sudaneses " (pueblos paganos del África subsahariana ). [42] Bajo su rey Tinbarutan ibn Usfayshar, los Sanhaja Lamtuna erigieron (o capturaron) la ciudadela de Awdaghust, una parada crítica en la ruta comercial transahariana . Después del colapso de la unión Sanhaja, Awdaghust pasó al Imperio de Ghana ; y las rutas transsaharianas fueron asumidas por los Zenata Maghrawa de Sijilmasa . Los Maghrawa también explotaron esta desunión para desalojar a los Sanhaja Gazzula y Lamta de sus pastizales en los valles de Sous y Draa. Alrededor de 1035, el jefe Lamtuna Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Tifat (alias Tarsina), intentó reunificar las tribus del desierto de Sanhaja, pero su reinado duró menos de tres años. [ cita requerida ]

Hacia el año 1040, Yahya ibn Ibrahim , jefe de los Gudala (y cuñado del difunto Tarsina), partió en peregrinación a La Meca . A su regreso, se detuvo en Kairuán , en Ifriqiya , donde conoció a Abu Imran al-Fasi , natural de Fez , jurista y erudito de la escuela sunita malikí . En esa época, Ifriqiya estaba en ebullición. El gobernante zirí , al-Mu'izz ibn Badis , estaba contemplando abiertamente la posibilidad de romper con sus señores chiítas fatimíes en El Cairo, y los juristas de Kairuán le estaban presionando para que lo hiciera. En medio de esa atmósfera embriagadora, Yahya y Abu Imran entablaron una conversación sobre el estado de la fe en sus países occidentales, y Yahya expresó su decepción por la falta de educación religiosa y la negligencia de la ley islámica entre su pueblo sanhaja del sur. Por recomendación de Abu Imran, Yahya ibn Ibrahim se dirigió al ribat de Waggag ibn Zelu, en el valle del Sous , en el sur de Marruecos, para buscar un maestro malikí para su pueblo. Waggag le asignó a uno de sus residentes, Abdallah ibn Yasin . [43] : 122

Abdallah ibn Yasin era un bereber gazzula, y probablemente un converso más que un musulmán de nacimiento. Su nombre puede leerse como "hijo de Ya-Sin " (el título de la 36.ª sura del Corán ), lo que sugiere que había borrado su pasado familiar y había "renacido" del Libro Sagrado. [44] Ibn Yasin ciertamente tenía el ardor de un fanático puritano; su credo se caracterizaba principalmente por un formalismo rígido y una estricta adhesión a los dictados del Corán y la tradición ortodoxa . [45] (Cronistas como al-Bakri alegan que el conocimiento de Ibn Yasin era superficial). Las reuniones iniciales de Ibn Yasin con el pueblo guddala fueron mal. Como tenía más ardor que profundidad, los argumentos de Ibn Yasin fueron cuestionados por su audiencia. Respondió a las preguntas con acusaciones de apostasía y repartió duros castigos por las más mínimas desviaciones. Los Guddala pronto se cansaron y lo expulsaron casi inmediatamente después de la muerte de su protector, Yahya ibn Ibrahim, en algún momento de la década de 1040. [ cita requerida ]

Ibn Yasin, sin embargo, encontró una recepción más favorable entre el pueblo vecino de Lamtuna . [45] Probablemente percibiendo el poder organizativo útil del fervor piadoso de Ibn Yasin, el jefe de Lamtuna Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni invitó al hombre a predicar a su pueblo. Los líderes de Lamtuna, sin embargo, mantuvieron a Ibn Yasin bajo control, forjando una asociación más productiva entre ellos. Invocando historias de la vida temprana de Mahoma, Ibn Yasin predicó que la conquista era un complemento necesario a la islamización, que no era suficiente simplemente adherirse a la ley de Dios, sino que también era necesario destruir la oposición a ella. En la ideología de Ibn Yasin, cualquier cosa fuera de la ley islámica podía caracterizarse como "oposición". Identificó al tribalismo, en particular, como un obstáculo. Creía que no bastaba con instar a su audiencia a dejar de lado sus lealtades de sangre y diferencias étnicas y abrazar la igualdad de todos los musulmanes bajo la Ley Sagrada, era necesario obligarlos a hacerlo. Para los líderes de Lamtuna, esta nueva ideología encajaba con su antiguo deseo de refundar la unión Sanhaja y recuperar sus dominios perdidos. A principios de la década de 1050, los Lamtuna, bajo el liderazgo conjunto de Yahya ibn Umar y Abdallah ibn Yasin, que pronto se autodenominaron al -Murabitin (almorávides), emprendieron una campaña para atraer a sus vecinos a su causa. [43] : 123

A principios de la década de 1050, surgió una especie de triunvirato al frente del movimiento almorávide, que incluía a Abdallah Ibn Yasin, Yahya Ibn Umar y su hermano Abu Bakr Ibn Umar . El movimiento estaba ahora dominado por los lamtuna en lugar de los guddala. [46] Durante la década de 1050, los almorávides comenzaron su expansión y su conquista de las tribus saharianas. [47] Sus primeros objetivos importantes fueron dos ciudades estratégicas ubicadas en los bordes norte y sur del desierto: Sijilmasa en el norte y Awdaghust en el sur. El control de estas dos ciudades permitiría a los almorávides controlar efectivamente las rutas comerciales transaharianas. Sijilmasa estaba controlada por los maghrawa , una parte de la confederación bereber zenata del norte , mientras que Awdaghust estaba controlada por los soninké . [48] Ambas ciudades fueron capturadas en 1054 o 1055. [49] Sijilmasa fue capturada primero y su líder, Mas'ud Ibn Wannudin, fue asesinado, junto con otros líderes maghrawa. Según fuentes históricas, el ejército almorávide cabalgaba sobre camellos y contaba con 30.000 hombres, aunque esta cifra puede ser una exageración. [50] Fortalecidos con el botín de su victoria, dejaron una guarnición de miembros de la tribu Lamtuna en la ciudad y luego se dirigieron hacia el sur para capturar Awdaghust, lo que lograron ese mismo año. Aunque la ciudad era principalmente musulmana, los almorávides saquearon la ciudad y trataron a la población con dureza con la base de que reconocían al rey pagano de Ghana . [50]

No mucho después de que el principal ejército almorávide abandonara Sijilmasa, la ciudad se rebeló y los maghrawa regresaron, masacrando a la guarnición de Lamtuna. Ibn Yasin respondió organizando una segunda expedición para recuperarla, pero los guddala se negaron a unirse a él y regresaron a sus tierras natales en las regiones desérticas a lo largo de la costa atlántica. [51] [52] La historiadora Amira Bennison sugiere que algunos almorávides, incluidos los guddala, no estaban dispuestos a verse arrastrados a un conflicto con las poderosas tribus zanata del norte y esto creó tensión con aquellos, como Ibn Yasin, que veían la expansión hacia el norte como el siguiente paso en sus fortunas. [52] Mientras Ibn Yasin se fue al norte, Yahya Ibn Umar permaneció en el sur en Adrar, el corazón de los lamtuna, en un lugar defendible y bien provisto llamado Jabal Lamtuna, a unos 10 kilómetros al noroeste de la moderna Atar . [53] [54] Su bastión allí era una fortaleza llamada Azuggi (también traducida de forma variable como Azougui o Azukki), que había sido construida anteriormente por su hermano Yannu ibn Umar al-Hajj. [53] [55] [54] [56] Algunos eruditos, entre ellos Attilio Gaudio, [57] Christiane Vanacker, [58] y Brigitte Himpan y Diane Himpan-Sabatier [59] describen Azuggi como la "primera capital" de los almorávides. Yahya ibn Umar murió posteriormente en batalla contra los Guddala en 1055 o 1056, [52] o más tarde en 1057. [60]

Mientras tanto, en el norte, Ibn Yasin había ordenado a Abu Bakr que tomara el mando del ejército almorávide y pronto recuperaron Sijilmasa. [61] En 1056, habían conquistado Taroudant y el valle del Sous , y seguían imponiendo la ley islámica malikí sobre las comunidades que conquistaban. Cuando la campaña concluyó ese año, se retiraron a Sijilmasa y establecieron allí su base. Fue en esa época cuando Abu Bakr nombró a su primo, Yusuf ibn Tashfin , para comandar la guarnición de la ciudad. [62]

En 1058, cruzaron el Alto Atlas y conquistaron Aghmat , una próspera ciudad comercial cerca de las estribaciones de las montañas, y la convirtieron en su capital. [63] [15] Luego entraron en contacto con los Barghawata , una confederación tribal bereber que seguía una "herejía" islámica predicada por Salih ibn Tarif tres siglos antes. [64] Los Barghawata ocuparon la región al noroeste de Aghmat y a lo largo de la costa atlántica. Resistieron a los almorávides ferozmente y la campaña contra ellos fue sangrienta. Abdullah ibn Yasin murió en batalla con ellos en 1058 o 1059, en un lugar llamado Kurīfalalt o Kurifala. [11] [65] Sin embargo, en 1060, fueron conquistados por Abu Bakr ibn Umar y se vieron obligados a convertirse al Islam ortodoxo. [11] Poco después de esto, Abu Bakr había llegado hasta Meknes . [66]

Hacia el año 1068, Abu Bakr se casó con una mujer bereber noble y rica, Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyah , que llegaría a ser muy influyente en el desarrollo de la dinastía. Zaynab era hija de un rico comerciante de Kairuán que se había establecido en Aghmat. Había estado casada previamente con Laqut ibn Yusuf ibn Ali al-Maghrawi, gobernante de Aghmat, hasta que este último fue asesinado durante la conquista almorávide de la ciudad. [67]

Fue en esta época cuando Abu Bakr ibn Umar fundó la nueva capital de Marrakech. Las fuentes históricas citan una variedad de fechas para este evento que van desde 1062, dada por Ibn Abi Zar e Ibn Khaldun , hasta 1078 (470 AH), dada por Muhammad al-Idrisi . [68] El año 1070, dado por Ibn Idhari , [69] es el más utilizado por los historiadores modernos, [70] aunque algunos escritores todavía citan 1062. [71] Poco después de fundar la nueva ciudad, Abu Bakr se vio obligado a regresar al sur del Sahara para reprimir una rebelión de los Guddala y sus aliados que amenazaban las rutas comerciales del desierto, ya sea en 1060 [72] o 1071. [73] Su esposa Zaynab parece haber estado dispuesta a seguirlo al sur y él le concedió el divorcio. Al parecer, por orden de Abu Bakr, se casó con Yusuf Ibn Tashfin. [73] [66] Antes de partir, Abu Bakr nombró a Ibn Tashfin como su delegado a cargo de los nuevos territorios almorávides en el norte. [69] Según Ibn Idhari, Zaynab se convirtió en su asesor político más importante. [74]

Un año después, tras reprimir la revuelta en el sur, Abu Bakr regresó al norte, hacia Marrakech, con la esperanza de recuperar el control de la ciudad y de las fuerzas almorávides en el norte de África. [74] [66] Sin embargo, Ibn Tashfin no estaba dispuesto a renunciar a su propia posición de liderazgo. Mientras Abu Bakr todavía estaba acampado cerca de Aghmat, Ibn Tashfin le envió generosos regalos, pero se negó a obedecer su llamado, al parecer por consejo de Zaynab. [75] [11] Abu Bakr reconoció que no podía forzar la situación y no estaba dispuesto a luchar una batalla por el control de Marrakech, por lo que decidió reconocer voluntariamente el liderazgo de Ibn Tashfin en el Magreb. Los dos hombres se reunieron en terreno neutral entre Aghmat y Marrakech para confirmar el acuerdo. Después de una corta estancia en Aghmat, Abu Bakr regresó al sur para continuar su liderazgo de los almorávides en el Sahara. [75] [11]

Después de esto, el Imperio almorávide se dividió en dos partes distintas pero codependientes: una liderada por Ibn Tashfin en el norte, y otra liderada por Abu Bakr en el sur. [15] Abu Bakr continuó siendo reconocido formalmente como el líder supremo de los almorávides hasta su muerte en 1087. [66] Las fuentes históricas no dan ninguna indicación de que los dos líderes se trataran mutuamente como enemigos e Ibn Tashfin continuó acuñando monedas en nombre de Abu Bakr hasta la muerte de este último. [76] Después de la partida de Abu Bakr, Ibn Tashfin fue en gran parte responsable de la construcción del estado almorávide en el Magreb durante las siguientes dos décadas. [72] Uno de los hijos de Abu Bakr, Ibrahim, que sirvió como líder almorávide en Sijilmasa entre 1071 y 1076 (según la moneda acuñada allí), desarrolló una rivalidad con Ibn Tashfin e intentó enfrentarse a él hacia 1076. Marchó a Aghmat con la intención de reclamar la posición de su padre en el Magreb. Otro comandante almorávide, Mazdali ibn Tilankan , que estaba emparentado con ambos hombres, calmó la situación y convenció a Ibrahim de unirse a su padre en el sur en lugar de iniciar una guerra civil. [76] [77]

Mientras tanto, Ibn Tashfin había ayudado a poner bajo control almorávide la gran zona de lo que hoy es Marruecos , el Sáhara Occidental y Mauritania . Pasó al menos varios años capturando cada fuerte y asentamiento en la región alrededor de Fez y en el norte de Marruecos. [78] Después de que la mayor parte de la región circundante estuvo bajo su control, finalmente pudo conquistar Fez definitivamente. Sin embargo, existe cierta contradicción e incertidumbre entre las fuentes históricas con respecto a la cronología exacta de estas conquistas, ya que algunas fuentes datan las principales conquistas en la década de 1060 y otras las datan en la década de 1070. [79] Algunos autores modernos citan la fecha de la conquista final de Fez como 1069 (461 AH). [80] [81] [82] El historiador Ronald Messier da la fecha más específicamente como el 18 de marzo de 1070 (462 AH). [83] Otros historiadores datan esta conquista en 1074 o 1075. [80] [84] [85]

En 1079, Ibn Tashfin envió un ejército de 20.000 hombres desde Marrakech para avanzar hacia lo que ahora es Tlemcen para atacar a los Banu Ya'la, la tribu zenata que ocupaba la zona. Liderados por Mazdali Ibn Tilankan, el ejército derrotó a los Banu Ya'la en batalla cerca del valle del río Moulaya y ejecutó a su comandante, Mali Ibn Ya'la, el hijo del gobernante de Tlemcen. Sin embargo, Ibn Tilankan no avanzó hacia Tlemcen de inmediato ya que la ciudad de Oujda , ocupada por los Bani Iznasan, era demasiado fuerte para capturarla. [86] En cambio, el propio Ibn Tashfin regresó con un ejército en 1081 que capturó Oujda y luego conquistó Tlemcen, masacrando a las fuerzas maghrawa allí y a su líder, al-Abbas Ibn Bakhti al-Maghrawi. [86] Siguió adelante y en 1082 había capturado Argel . [82] Posteriormente, Ibn Tashfin consideró a Tlemcen como su base oriental. En ese momento, la ciudad había consistido en un asentamiento más antiguo llamado Agadir, pero Ibn Tashfin fundó una nueva ciudad junto a ella llamada Takrart, que más tarde se fusionó con Agadir en el período almohade para convertirse en la ciudad actual. [87] [88]

Los almorávides se enfrentaron posteriormente con los hammadíes al este en múltiples ocasiones, pero no hicieron un esfuerzo sostenido para conquistar el Magreb central y en su lugar centraron sus esfuerzos en otros frentes. [89] [90] Finalmente, en 1104, firmaron un tratado de paz con los hammadíes. [89] Argel se convirtió en su puesto avanzado más oriental. [90]

En la década de 1080, los gobernantes musulmanes locales de al-Andalus (la península Ibérica ) solicitaban la ayuda de Ibn Tashfin contra los reinos cristianos invasores del norte. Ibn Tashfin hizo de la captura de Ceuta su principal objetivo antes de hacer cualquier intento de intervenir allí. Ceuta, controlada por las fuerzas zenata bajo el mando de Diya al-Dawla Yahya, era la última ciudad importante en el lado africano del estrecho de Gibraltar que todavía resistía contra él. [91] A cambio de una promesa de ayudarlo, Ibn Tashfin exigió que al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad , el gobernante de Sevilla , brindara asistencia para sitiar la ciudad. Al-Mu'tamid accedió y envió una flota para bloquear la ciudad por mar, mientras que el hijo de Ibn Tashfin, Tamim, dirigió el asedio por tierra. [91] La ciudad finalmente se rindió en junio-julio de 1083 [92] o en agosto de 1084. [91]

Ibn Tashfin también se esforzó por organizar el nuevo reino almorávide. Bajo su gobierno, el Magreb occidental se dividió en provincias administrativas bien definidas por primera vez (antes de esto, había sido principalmente territorio tribal). Se estableció un gobierno central en desarrollo en Marrakech, mientras que confió provincias clave a aliados y parientes importantes. [93] El naciente estado almorávide se financió en parte con los impuestos permitidos por la ley islámica y con el oro que venía de Ghana en el sur, pero en la práctica siguió dependiendo del botín de las nuevas conquistas. [92] La mayoría del ejército almorávide continuó estando compuesto por reclutas sanhaja, pero Ibn Tashfin también comenzó a reclutar esclavos para formar una guardia personal ( ḥashm ), que incluía 5000 soldados negros ( 'abid ) y 500 soldados blancos ( uluj , probablemente de origen europeo). [92] [94]

En algún momento, Yusuf Ibn Tashfin decidió reconocer a los califas abasíes de Bagdad como señores supremos. Aunque los abasíes tenían poco poder político directo en ese momento, el simbolismo de este acto fue importante y aumentó la legitimidad de Ibn Tashfin. [95] Según Ibn Idhari, fue al mismo tiempo que Ibn Tashfin también tomó el título de amīr al-muslimīn ('Comandante de los musulmanes'). Ibn Idhari data esto en 1073-74, pero algunos autores, incluido el historiador moderno Évariste Lévi-Provençal , han datado esta decisión política más tarde, muy probablemente cuando los almorávides estaban en proceso de asegurar el control de al-Andalus. [96] Según Amira Bennison, el reconocimiento del califa abasí debe haberse establecido a más tardar en la década de 1090. [97] Cuando Abu Bakr ibn al-Arabi visitó Bagdad entre 1096 y 1098, posiblemente como parte de una embajada almorávide al califa al-Mustazhir , afirmó que las oraciones del viernes ya se estaban realizando en nombre del califa abasí en todos los territorios gobernados por Yusuf Ibn Tashfin. [97]

Tras dejar a Yusuf Ibn Tashfin en el norte y regresar al sur, Abu Bakr Ibn Umar hizo de Azuggi su base. La ciudad actuó como capital de los almorávides del sur bajo su mando y el de sus sucesores. [98] [99] [55] [100] [54] [101] A pesar de la importancia de las rutas comerciales del Sahara para los almorávides, la historia del ala sur del imperio no está bien documentada en las fuentes históricas árabes y a menudo se descuida en las historias del Magreb y de al-Andalus. [102] Esto también ha fomentado una división en los estudios modernos sobre los almorávides, y la arqueología ha desempeñado un papel más importante en el estudio del ala sur, en ausencia de más fuentes textuales. La naturaleza exacta y el impacto de la presencia almorávide en el Sahel es un tema muy debatido entre los africanistas . [102]

Según la tradición árabe, los almorávides bajo el liderazgo de Abu Bakr conquistaron el Imperio de Ghana , fundado por los soninkés, en algún momento alrededor de 1076-77. [99] Un ejemplo de esta tradición es el registro del historiador Ibn Khaldun , quien citó a Shaykh Uthman, el faqih de Ghana, escribiendo en 1394. Según esta fuente, los almorávides debilitaron a Ghana y recaudaron tributos del Sudán, hasta el punto de que la autoridad de los gobernantes de Ghana disminuyó, y fueron subyugados y absorbidos por los sosso , un pueblo vecino del Sudán. [103] Las tradiciones en Mali relataron que los sosso atacaron y tomaron el control de Mali también, y el gobernante de los sosso, Sumaouro Kanté, tomó el control de la tierra. [104]

Sin embargo, las críticas de Conrad y Fisher (1982) argumentaron que la noción de cualquier conquista militar almorávide en su núcleo es meramente folclore perpetuado, derivado de una mala interpretación o una confianza ingenua en fuentes árabes. [105] Según el profesor Timothy Insoll, la arqueología de la antigua Ghana simplemente no muestra los signos de cambio rápido y destrucción que se asociarían con cualquier conquista militar de la era almorávide. [106]

Dierke Lange está de acuerdo con la teoría original de la incursión militar, pero sostiene que esto no excluye la agitación política almorávide, afirmando que el factor principal de la desaparición del Imperio de Ghana se debió en gran medida a esta última. [107] Según Lange, la influencia religiosa almorávide fue gradual, en lugar de ser el resultado de una acción militar; allí los almorávides ganaron poder casándose con miembros de la nobleza de la nación. Lange atribuye el declive de la antigua Ghana a numerosos factores no relacionados, uno de los cuales es probablemente atribuible a luchas dinásticas internas instigadas por la influencia almorávide y las presiones islámicas, pero carentes de conquista militar. [108]

Esta interpretación de los acontecimientos ha sido cuestionada por estudiosos posteriores como Sheryl L. Burkhalter, [109] quien sostuvo que, cualquiera que fuera la naturaleza de la "conquista" en el sur del Sahara, la influencia y el éxito del movimiento almorávide en la obtención del oro de África occidental y su amplia circulación requirieron un alto grado de control político. [110]

El geógrafo árabe Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri escribió que los almorávides acabaron con el Islam ibadí en Tadmekka en 1084 y que Abu Bakr "llegó a la montaña de oro" en el profundo sur. [111] Abu Bakr finalmente murió en Tagant en noviembre de 1087 tras una herida en batalla -según la tradición oral, por una flecha [112] [113] - mientras luchaba en la región histórica de Sudán . [114]

Tras la muerte de Abu Bakr (1087), la confederación de tribus bereberes del Sahara quedó dividida entre los descendientes de Abu Bakr y su hermano Yahya, y habría perdido el control de Ghana. [111] Sheryl Burkhalter sugiere que el hijo de Abu Bakr, Yahya, fue el líder de la expedición almorávide que conquistó Ghana en 1076, y que los almorávides habrían sobrevivido a la pérdida de Ghana y a la derrota en el Magreb por parte de los almohades, y habrían gobernado el Sahara hasta finales del siglo XII. [109]

Inicialmente, parece que Ibn Tashfin tenía poco interés en involucrar a los almorávides en la política de al-Andalus (los territorios musulmanes en la península Ibérica). [115] Después del colapso del Califato de Córdoba a principios del siglo XI, al-Andalus se había dividido en pequeños reinos o ciudades-estado conocidas como las taifas . Estos estados luchaban constantemente entre sí, pero no podían reunir grandes ejércitos propios, por lo que se volvieron dependientes en cambio de los reinos cristianos del norte para el apoyo militar. Este apoyo se aseguró mediante el pago regular de parias (tributos) a los reyes cristianos, pero los pagos se convirtieron en una carga fiscal que vació los tesoros de estos gobernantes locales. A su vez, los gobernantes de taifas cargaron a sus súbditos con un aumento de impuestos, incluidos impuestos y aranceles que no se consideraban legales según la ley islámica. A medida que los pagos de tributos comenzaron a fallar, los reinos cristianos recurrieron a incursiones punitivas y, finalmente, a la conquista. Los reyes de taifas no quisieron o no pudieron unirse para contrarrestar esta amenaza, e incluso el reino de taifas más poderoso, Sevilla , fue incapaz de resistir los avances cristianos. [116] [117]

Tras la toma almorávide de Ceuta (1083) en la orilla sur del estrecho de Gibraltar, Ibn Tashfin tuvo vía libre para intervenir en al-Ándalus. Fue en ese mismo año cuando Alfonso VI , rey de Castilla y León , dirigió una campaña militar en el sur de al-Ándalus para castigar a al-Mu'tamid de Sevilla por no pagarle tributo. Su expedición penetró hasta Tarifa , el punto más meridional de la península Ibérica. Un par de años después, en mayo de 1085, se hizo con el control de Toledo , anteriormente una de las ciudades-estado más poderosas de al-Ándalus. Poco después, también inició un asedio a Zaragoza . [92] Estos dramáticos acontecimientos obligaron a los reyes de taifas a considerar finalmente la posibilidad de buscar una intervención externa por parte de los almorávides. [118] [119] Según la fuente árabe más detallada, fue al-Mu'tamid, el gobernante de Sevilla, quien convocó una reunión con sus vecinos, al-Mutawwakil de Badajoz y Abdallah ibn Buluggin de Granada , donde acordaron enviar una embajada a Ibn Tashfin para solicitar su ayuda. [118] Los reyes de taifas eran conscientes de los riesgos que conllevaba una intervención almorávide, pero la consideraron la mejor opción entre sus malas opciones. Se dice que al-Mu'tamid comentó amargamente: "Es mejor pastorear camellos que ser porquerizo", es decir, que era mejor someterse a otro gobernante musulmán que terminar como súbditos de un rey cristiano. [118] [119]

Como condición para su ayuda, Ibn Tashfin exigió que se le entregara Algeciras (una ciudad en la costa norte del estrecho de Gibraltar, frente a Ceuta) para poder usarla como base para sus tropas. Al-Mu'tamid estuvo de acuerdo. Ibn Tashfin, receloso de la vacilación de los reyes de taifas , envió inmediatamente una fuerza de avanzada de 500 soldados a través del estrecho para tomar el control de Algeciras. Lo hicieron en julio de 1086 sin encontrar resistencia. El resto del ejército almorávide, que contaba con unos 12.000 hombres, pronto los siguió. [118] Ibn Tashfin y su ejército marcharon entonces a Sevilla, donde se encontraron con las fuerzas de al-Mu'tamid, al-Mutawwakil y Abdallah ibn Buluggin. Alfonso VI, al enterarse de este acontecimiento, levantó el sitio de Zaragoza y marchó hacia el sur para enfrentarse a ellos. Los dos bandos se encontraron en un lugar al norte de Badajoz, llamado Zallaqa en fuentes árabes y Sagrajas en fuentes cristianas. En la batalla de Sagrajas (o batalla de Zallaqa), el 23 de octubre de 1086, Alfonso fue derrotado rotundamente y obligado a retirarse hacia el norte en desorden. Al-Mu'tamid recomendó que aprovecharan la ventaja, pero Ibn Tashfin no persiguió al ejército cristiano y regresó en su lugar a Sevilla y luego al norte de África. Es posible que no estuviera dispuesto a estar lejos de su base de origen durante demasiado tiempo o que la muerte de su hijo mayor, Sir, lo animara a regresar. [120] [121]

Tras la marcha de Ibn Tashfin, Alfonso VI reanudó rápidamente su presión sobre los reyes de taifas y les obligó a enviar de nuevo pagos de tributos. Capturó la fortaleza de Aledo , aislando así la zona oriental de al-Ándalus de los demás reinos musulmanes. Mientras tanto, Ibn Rashiq, gobernante de Murcia , se vio envuelto en una rivalidad con al-Mu'tamid de Sevilla. Como resultado, esta vez fueron las élites o notables ( wujūh ) de al-Ándalus quienes pidieron ayuda a los almorávides, en lugar de los reyes. [122] En mayo-junio de 1088, Ibn Tashfin desembarcó en Algeciras con otro ejército, al que pronto se unieron al-Mu'tamid de Sevilla, Abdallah ibn Buluggin de Granada y otras tropas enviadas por Ibn Sumadih de Almería e Ibn Rashiq de Murcia. A continuación, se dispusieron a retomar Aledo. El asedio, sin embargo, se vio socavado por las rivalidades y la desunión entre los reyes de taifas . Finalmente, llegaron noticias a los musulmanes de que Alfonso VI traía un ejército para ayudar a la guarnición castellana. En noviembre de 1088, Ibn Tashfin levantó el asedio y regresó al norte de África de nuevo, sin haber logrado nada. [123] Alfonso VI envió a su comandante de confianza, Alvar Fañez , para presionar nuevamente a los reyes de taifas . Logró obligar a Abdallah ibn Buluggin a reanudar los pagos de tributos y comenzó a presionar a al-Mu'tamid a su vez. [124]

En 1090, Ibn Tashfin regresó a al-Andalus una vez más, pero en este punto parecía haber renunciado a los reyes de taifas y ahora tenía la intención de tomar el control directo de la región. [124] [125] La causa almorávide se benefició del apoyo de los fuqahā malikis ( juristas islámicos ) en al-Andalus, quienes ensalzaron la devoción almorávide a la yihad mientras criticaban a los reyes de taifas como impíos, autoindulgentes y, por lo tanto, ilegítimos. [124] [126] En septiembre de 1090, Ibn Tashfin obligó a Granada a rendirse ante él y envió a Abdallah ibn Buluggin al exilio en Aghmat. Luego regresó al norte de África nuevamente, pero esta vez dejó a su sobrino, Sir ibn Abu Bakr, a cargo de las fuerzas almorávides en al-Andalus. Al-Mu'tamid, buscando salvar su posición, recurrió a una alianza con Alfonso VI, lo que socavó aún más su propio apoyo popular. [124] A principios de 1091, los almorávides tomaron el control de Córdoba y se dirigieron hacia Sevilla, derrotando a una fuerza castellana liderada por Alvar Fañez que vino a ayudar a al-Mu'tamid. En septiembre de 1091, al-Mu'tamid entregó Sevilla a los almorávides y fue exiliado a Aghmat. [124] A finales de 1091, los almorávides capturaron Almería. [124] A finales de 1091 o enero de 1092, Ibn Aisha, uno de los hijos de Ibn Tashfin, tomó el control de Murcia. [127]

La toma de Murcia puso a los almorávides al alcance de Valencia , que estaba oficialmente bajo el control de al-Qadir , el antiguo gobernante taifa de Toledo. Había sido instalado aquí en 1086 por los castellanos después de que tomaran el control de Toledo. [128] El gobierno impopular de al-Qadir en Valencia fue apoyado por una guarnición castellana encabezada por Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar , un noble y mercenario castellano más conocido hoy como El Cid. En octubre de 1092, cuando El Cid estaba fuera de la ciudad, hubo una insurrección y un golpe de estado liderado por el cadí (juez) Abu Ahmad Ja'far Ibn Jahhaf. Este último pidió ayuda a los almorávides en Murcia, quienes enviaron un pequeño grupo de guerreros a la ciudad. La guarnición castellana se vio obligada a marcharse y al-Qadir fue capturado y ejecutado. [129] [130]

Sin embargo, los almorávides no enviaron suficientes fuerzas para oponerse al regreso de El Cid e Ibn Jahhaf socavó su apoyo popular al proceder a instalarse como gobernante, actuando como otro rey de taifas . [130] [129] El Cid comenzó un largo asedio de la ciudad , rodeándola por completo, quemando las aldeas cercanas y confiscando las cosechas del campo circundante. Ibn Jahhaf acordó en un momento pagar tributo a El Cid para poner fin al asedio, lo que resultó en que los almorávides en la ciudad fueran escoltados fuera por los hombres de El Cid. [131] Por razones que siguen sin estar claras, un ejército de socorro almorávide dirigido por el sobrino de Ibn Tashfin, Abu Bakr ibn Ibrahim, se acercó a Valencia en septiembre de 1093, pero luego se retiró sin enfrentarse a El Cid. [130] Ibn Jahhaf continuó las negociaciones. Al final, se negó a pagar el tributo de El Cid y el asedio continuó. [130] En abril de 1094, la ciudad estaba muriendo de hambre y decidió rendirla poco después. El Cid volvió a entrar en Valencia el 15 de junio de 1094, después de 20 meses de asedio. En lugar de gobernar nuevamente a través de un títere, ahora tomó el control directo como rey. [132]

Mientras tanto, también en 1094, los almorávides tomaron el control de todo el reino de taifas de Badajoz después de que su gobernante, al-Mutawwakil, buscara su propia alianza con Castilla. [124] La expedición almorávide fue liderada por Sir ibn Abu Bakr, quien había sido designado gobernador de Sevilla. [132] Los almorávides luego volvieron su atención a Valencia, donde otro de los sobrinos de Ibn Tashfin, Muhammad ibn Ibrahim, recibió la orden de tomar la ciudad. [130] [132] Llegó fuera de sus murallas en octubre de 1094 y comenzó a atacar la ciudad. El asedio terminó cuando El Cid lanzó un ataque de dos lados: envió una salida desde una puerta de la ciudad que se hizo pasar por su fuerza principal, ocupando a las tropas almorávides, mientras que él personalmente dirigió otra fuerza desde una puerta de la ciudad diferente y atacó su campamento indefenso. Esto infligió la primera derrota importante a los almorávides en la península Ibérica. [133] Tras su victoria, El Cid ejecutó a Ibn Jahhaf quemándolo vivo en público, quizá en represalia por su traición. [130]

El Cid fortificó su nuevo reino construyendo fortalezas a lo largo de los accesos meridionales a la ciudad para defenderse de futuros ataques almorávides. [133] A finales de 1096, Ibn Aisha dirigió un ejército de 30.000 hombres para sitiar la más fuerte de estas fortalezas, Peña Cadiella (justo al sur de Xàtiva ). [133] El Cid se enfrentó a ellos y pidió refuerzos a Aragón . Cuando los refuerzos se acercaron, los almorávides levantaron el asedio, pero tendieron una trampa a las fuerzas del Cid mientras marchaban de regreso a Valencia. Emboscaron con éxito a los cristianos en un estrecho paso ubicado entre las montañas y el mar, pero el Cid logró reunir a sus tropas y repeler a los almorávides una vez más. [134] En 1097, el gobernador almorávide de Xàtiva, Ali ibn al-Hajj, [130] dirigió otra incursión en territorio valenciano, pero fue rápidamente derrotado y perseguido hasta Almenara , que el Cid capturó después de un asedio de tres meses. [134]

En 1097, el propio Yusuf Ibn Tashfin dirigió otro ejército a al-Andalus. Partiendo de Córdoba con Muhammad ibn al-Hajj como su comandante de campo, marchó contra Alfonso VI, que estaba en Toledo en ese momento. Los castellanos fueron derrotados en la batalla de Consuegra . El Cid no participó, pero su hijo, Diego, murió en la batalla. [135] Poco después, Alvar Fañez también fue derrotado cerca de Cuenca en otra batalla con los almorávides, liderados por Ibn Aisha. Este último siguió esta victoria devastando las tierras alrededor de Valencia y derrotó a otro ejército enviado por El Cid. [135] A pesar de estas victorias en el campo, los almorávides no capturaron ninguna ciudad nueva o fortaleza importante. [136]

El Cid intentó cristianizar Valencia, convirtiendo su mezquita principal en una iglesia y estableciendo un obispado , pero finalmente no logró atraer a muchos nuevos colonos cristianos a la ciudad. [135] Murió el 10 de julio de 1099, dejando a su esposa, Jimena, a cargo del reino. Ella no pudo resistir las presiones almorávides, que culminaron en un asedio de la ciudad por parte del veterano comandante almorávide, Mazdali, a principios de la primavera de 1102. En abril-mayo, Jimena y los cristianos que deseaban abandonar la ciudad fueron evacuados con la ayuda de Alfonso VI. Los almorávides ocuparon la ciudad después de ellos. [135] [136]

Ese mismo año, con la toma de Valencia contando como otro triunfo, Yusuf Ibn Tashfin celebró y dispuso que su hijo, Ali ibn Yusuf , fuera reconocido públicamente como su heredero. [136] El rey taifa de Zaragoza, la única otra potencia musulmana que quedaba en la península, envió un embajador en esta ocasión y firmó un tratado con los almorávides. [136] Cuando Ibn Tashfin murió en 1106, los almorávides tenían así el control de todo al-Andalus excepto Zaragoza. En general, no habían reconquistado ninguna de las tierras perdidas a los reinos cristianos en el siglo anterior. [137]

Ali Ibn Yusuf ( r. 1106-1143 ) nació en Ceuta y se educó en las tradiciones de al-Andalus, a diferencia de sus predecesores, que eran del Sahara. [138] [139] Según algunos eruditos, Ali ibn Yusuf representó una nueva generación de liderazgo que había olvidado la vida del desierto por las comodidades de la ciudad. [140] Su largo reinado de 37 años se ve históricamente ensombrecido por las derrotas y el deterioro de las circunstancias que caracterizaron los años posteriores, pero la primera década aproximadamente, antes de 1118, se caracterizó por continuos éxitos militares, posibles en gran parte gracias a generales expertos. [138] Si bien los almorávides siguieron siendo dominantes en las batallas de campo, las deficiencias militares se estaban haciendo evidentes en su relativa incapacidad para sostener y ganar asedios largos. [141] [142] En estos primeros años, el estado almorávide también era rico, acuñando más oro que nunca, y Ali ibn Yusuf se embarcó en ambiciosos proyectos de construcción, especialmente en Marrakech. [138]

Tras su entronización, Ali ibn Yusuf fue aceptado como nuevo gobernante por la mayoría de los súbditos almorávides, a excepción de su sobrino, Yahya ibn Abu Bakr, gobernador de Fez. [143] Ali ibn Yusuf marchó con su ejército hasta las puertas de Fez, lo que obligó a Yahya a huir a Tlemcen. Allí, el veterano comandante almorávide, Mazdali, convenció a Yahya de que se reconciliara con su tío. Yahya aceptó, realizó una peregrinación a La Meca y, a su regreso, se le permitió reunirse con la corte de Ali ibn Yusuf en Marrakech. [143]

Ali ibn Yusuf visited al-Andalus for the first time of his reign in 1107. He organized the Almoravid administration there and placed his brother Tamim as overall governor, with Granada acting as the administrative capital.[144] The first major offensive in al-Andalus during his reign took place in the summer of 1108. Tamim, assisted by troops from Murcia and Cordoba, besieged and captured the small fortified town of Uclés, east of Toledo. Alfonso VI sent a relief force, led by the veteran Alvar Fañez, that was defeated on 29 May in the Battle of Uclés.[145] The result was made worse for Alfonso VI because his son and heir, Sancho, died in the battle.[146] In the aftermath, the Castilians abandoned Cuenca and Huete, which opened the way for an Almoravid invasion of Toledo.[141] This came in the summer of 1109, with Ali Ibn Yusuf crossing over to lead the campaign in person. The death of Alfonso VI in June must have provided another advantage to the Almoravids. Talavera, west of Toledo, was captured on 14 August. Toledo itself, however, resisted under the leadership of Alvar Fañez. Unable to overcome the city's formidable defenses, Ali ibn Yusuf eventually retreated without capturing it.[141]

Meanwhile, the Taifa king of Zaragoza, al-Musta'in, was a capable ruler but faced conflicting pressures. Like the previous Taifa rulers, he continued to pay parias to the Christian kingdoms to keep the peace, but popular sentiment within the city opposed this policy and increasingly supported the Almoravids. To appease this sentiment, al-Musta'in embarked on an expedition against the Christians of Aragon, but it failed.[141] He died in battle in January 1110 at Valtierra. His son and successor, Imad al-Dawla, was unable to establish his authority and, faced with the threat of revolt, fled the city. Ali ibn Yusuf seized the opportunity and gave Muhammad ibn al-Hajj the task of capturing Zaragoza.[147] On 30 May, Ibn al-Hajj entered the city with little opposition, ending the last independent Taifa kingdom.[148]

The Almoravids remained on the offensive in the following years, but some of their best generals died during this time. In 1111, Sir ibn Abu Bakr (governor of Seville) campaigned in the west, occupying Lisbon and Santarém and securing the frontier along the Tagus River.[148] Muhammad ibn al-Hajj continued to be active in the east. His expedition to Huesca in 1112 was the last time that Muslim forces operated near the Pyrenees.[148] In 1114, he campaigned in Catalonia and raided across the region, aided by Ibn Aisha from Valencia. On their return march, however, the Almoravids were ambushed and both commanders were killed.[148] In late 1113, Sir ibn Abu Bakr passed away. In 1115, it was Mazdali, one of the most veteran and loyal allies of Yusuf ibn Tashfin's family, who died in battle while serving as governor of Cordoba and campaigning to the north of it. Together, these deaths represented a major loss of senior and capable commanders for the Almoravids.[146][149]

In 1115, the new governor of Zaragoza, Abu Bakr ibn Ibrahim ibn Tifilwit, besieged Barcelona for 27 days while Count Ramon Berengar III was in Majorca. They lifted the siege when the Count returned, but in that same year the Almoravids captured the Balearic Islands, which had been temporarily occupied by the Catalans and Pisans.[148] The Almoravids occupied Majorca without a fight after the death of the last local Muslim ruler, Mubashir al-Dawla.[148]

Ali ibn Yusuf made his third crossing into al-Andalus in 1117 to lead an attack on Coimbra.[150] After only a short siege, however, he withdrew. His army raided along the way back to Seville and won significant spoils, but it was a further sign that Almoravid initiative was being depleted.[148][146]

Almoravid fortunes began to turn definitively after 1117. While Léon and Castile were in disarray following the death of Alfonso VI, other Christian kingdoms exploited opportunities to expand their territories at the expense of the Almoravids.[151] In 1118, Alfonso I El Batallador ('The Battler'), king of Aragon, launched a successful attack on Zaragoza with the help of the French crusader Gaston de Béarn.[146] The siege of the city began on 22 May and, after no significant reinforcements arrived, it surrendered on 18 December.[152] Ali ibn Yusuf ordered a major expedition to recover the loss, but it suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Cutanda in 1120.[152]

The crisis is evidence that Almoravid forces were over-extended across their vast territories.[152][146] When the Almoravid governor of Zaragoza, Abd Allah ibn Mazdali, had died earlier in 1118, no replacement was forthcoming and the Almoravid garrison left in the city prior to the siege seems to have been very small.[152] It is possible that Yusuf ibn Tashfin had understood this problem and had intended to leave Zaragoza as a buffer state between the Almoravids and the Christians, as suggested by an apocryphal story in the Hulul al-Mawshiya, a 14th-century chronicle, which reports that Ibn Tashfin, while on his deathbed, advised his son to follow this policy.[153] Alfonso I's capture of Zaragoza in 1118, along with the union of Aragon with the counties of Catalonia in 1137, also transformed the Kingdom of Aragon into a major Christian power in the region. To the west, Afonso I of Portugal asserted his independent authority and effectively created the Kingdom of Portugal. The growing power of these kingdoms added to the political difficulties Muslims now faced in the Iberian Peninsula.[154]

This major reversal precipitated a decline in popular support for the Almoravids, at least in al-Andalus. Andalusi society largely cooperated with the Almoravids on the understanding that they could keep the aggressive Christian kingdoms at bay. Once this was no longer the case, their authority became increasingly hollow.[155][156] Their legitimacy was further undermined by the issue of taxation. One of the main appeals of early Almoravid rule had been its mission to eliminate non-canonical taxes (i.e. those not sanctioned by the Qur'an), thus relieving the people of a major fiscal burden. However, it was not feasible to finance Almoravid armies in the fight against multiple enemies across a large empire with the funding from Quranic taxes alone. Ali ibn Yusuf was thus forced to reintroduce non-canonical taxes while the Almoravids were losing ground.[155]

These developments may have been factors in sparking an uprising in Cordoba in 1121. The Almoravid governor was besieged in his palace and the rebellion became so serious that Ali ibn Yusuf crossed over into al-Andalus to deal with it himself. His army besieged Cordoba but, eventually, a peace was negotiated between the Almoravid governor and the population.[156][155] This was the last time Ali ibn Yusuf visited al-Andalus.[144]

Alfonso I of Aragon inflicted further humiliations upon the Almoravids in the 1120s. In 1125, he marched down the eastern coast, reached Granada (though he refrained from besieging it), and devastated the countryside around Cordoba. In 1129, he raided the region of Valencia and defeated an army sent to stop him.[157] The Almoravid position in al-Andalus was only shored up in the 1130s. In 1129, following Alfonso I's attacks, Ali ibn Yusuf sent his son (and later successor), Tashfin ibn Ali, to re-organize the military structure in al-Andalus. His governorship grew to include Granada, Almeria, and Cordoba, becoming in effect the governor of al-Andalus for many years, where he performed capably.[158] The Banu Ghaniya clan, relatives of the ruling Almoravid dynasty, also became important players during this period. Yahya ibn Ali ibn Ghaniya was governor of Murcia up to 1133, while his brother was governor of the Balearic Islands after 1126. For much of the 1130s, Tashfin and Yahya led the Almoravid forces to a number of victories over Christian forces and reconquered some towns.[159] The most significant was the Battle of Fraga in 1134, where the Almoravids, led by Yahya, defeated an Aragonese army besieging the small Muslim town of Fraga. Notably, Alfonso I El Batallor was wounded and died shortly after.[160]

The greatest challenge to Almoravid authority came from the Maghreb, in the form of the Almohad movement. The movement was founded by Ibn Tumart in the 1120s and then continued after his death (c. 1130) under his successor, Abd al-Mu'min. They established their base at Tinmal, in the High Atlas mountains south of Marrakesh, and from here they progressively rolled back Almoravid territories.[161][162] The struggle against the Almohads was immensely draining on Almoravid resources and contributed to their shortage of manpower elsewhere, including in al-Andalus. It also required the construction of large fortresses in the Almoravid heartlands in present-day Morocco, such as the fortress of Tasghimut.[163] On Ali ibn Yusuf's orders, defensive walls were built around the capital of Marrakesh for the first time in 1126.[164] In 1138, he recalled his son, Tashfin, to Marrakesh in order to assist in the fight against the Almohads. Removing him from al-Andalus only further weakened the Almoravid position there.[165]

In 1138, the Almoravids suffered a defeat at the hands of Alfonso VII of León and Castile. In the Battle of Ourique (1139), they were defeated by Afonso I of Portugal, who thereby won his crown.[citation needed] During the 1140s, the situation grew steadily worse.[166]

After Ali ibn Yusuf's death in 1143, his son Tashfin ibn Ali lost ground rapidly before the Almohads. In 1146, he was killed in a fall from a precipice while attempting to escape after a defeat near Oran.[167] The Muridun staged a major revolt in southwestern Iberia in 1144 under the leadership of the Sufi mystic Ibn Qasi, who later passed to the Almohads. Lisbon was conquered by the Portuguese in 1147.[167]

Tashfin's two successors were Ibrahim ibn Tashfin and Ishaq ibn Ali, but their reigns were short. The conquest of Marrakesh by the Almohads in 1147 marked the fall of the dynasty, though fragments of the Almoravids continued to struggle throughout the empire.[167] Among these fragments, there was the rebel Yahya Al-Sahrāwiyya, who resisted Almohad rule in the Maghreb for eight years after the fall of Marrakesh before surrendering in 1155.[168] Also in 1155, the remaining Almoravids were forced to retreat to the Balearic Islands and later Ifriqiya under the leadership of the Banu Ghaniya, who were eventually influential in the downfall of their conquerors, the Almohads, in the eastern part of the Maghreb.[169]

The Almoravids adopted the Black standard, both to mark a religious character to their political and military movement as well as their religious and political legitimacy, which was demonstrated through their connection to the Abbasid Caliphate. According to some authors, the black color marked "the fight against impiety and error", it was also considered a representation of prophet Muhammad's flag.[170] However, most sources indicate a clear affiliation with the Abbasid Caliphs, regarded as the supreme religious and secular authority of Sunni Islam. Historian Tayeb El-Hibri writes:[171]

From far-off Maghreb, an emissary of the Almoravid Ali bin Yusuf bin Tashfin came to Baghdad in 498/1104 declaring allegiance to the Abbasids, announcing the adoption of the official Abbasid black for banners, and received the title Amir al-Muslimin wa Nasir "Amir al-Mu'minin" (prince of the Muslims and helper of the Commander of the Faithful).

Thus, the Almoravids adopted all the symbols of the Abbasids, including the color black (al-aswad), which would take part in the social and cultural life of the Almoravid tribes in their peace and war time. The desert tribes of Lamtuna and Massufa would adopt the black color for their veil when wrapped around the head,[172] and for war banners in their battles in Al-Andalus.[173]

Later on, the Black banner would be attested in clashes and uprisings opposing Almoravid and Almohad movements. The Almohads would adopt the white flag against Almoravid authority,[174] while major anti-Almohad rebellions unleashed by the Banu Ghaniya in the Maghreb and Hudids in Al-Andalus would confirm their affiliation to the Abbasids in the same manner as the early Almoravid movement did.[175][176]

The Almoravid movement started as a conservative Islamic reform movement inspired by the Maliki school of jurisprudence.[177] The writings of Abu Imran al-Fasi, a Moroccan Maliki scholar, influenced Yahya Ibn Ibrahim and the early Almoravid movement.[178][179]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Grifo-museo-opera-duomo_(cropped)_(cropped).jpg)

Amira Bennison describes the art of the Almoravid period as influenced by the "integration of several areas into a single political unit and the resultant development of a widespread Andalusi–Maghribi style", as well as the tastes of the Sanhaja rulers as patrons of art.[181] Bennison also challenges Robert Hillenbrand's characterization of the art of al-Andalus and the Maghreb as provincial and peripheral in consideration of Islamic art globally, and of the contributions of the Almoravids as "sparse" as a result of the empire's "puritanical fervour" and "ephemerality."[182]

At first, the Almoravids, subscribing to the conservative Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, rejected what they perceived as decadence and a lack of piety among the Iberian Muslims of the Andalusi taifa kingdoms.[179] However, monuments and textiles from Almería from the late Almoravid period indicate that the empire had changed its attitude with time.[179]

Artistic production under the Almoravids included finely constructed minbars produced in Córdoba; marble basins and tombstones in Almería; fine textiles in Almería, Málaga, Seville; and luxury ceramics.[183]

.jpg/440px-Stele_Almeria_Gao-Saney_MNM_R88-19-279_(cropped).jpg)

A large group of marble tombstones have been preserved from the first half of the 12th century. They were crafted in Almería in Al-Andalus, at a time when it was a prosperous port city under Almoravid control. The tombstones were made of Macael marble, which was quarried locally, and carved with extensive Kufic inscriptions that were sometimes adorned with vegetal or geometric motifs.[185] These demonstrate that the Almoravids not only reused Umayyad marble columns and basins, but also commissioned new works.[186] The inscriptions on them are dedicated to various individuals, both men and women, from a range of different occupations, indicating that such tombstones were relatively affordable. The stones take the form of either rectangular stelae or of long horizontal prisms known as mqabriyyas (similar to the ones found in the much later Saadian Tombs of Marrakesh). They have been found in many locations across West Africa and Western Europe, which is evidence that a wide-reaching industry and trade in marble existed. A number of pieces found in France were likely acquired from later pillaging. Some of the most ornate tombstones found outside Al-Andalus were discovered in Gao-Saney in the African Sahel, testament to the reach of Almoravid influence into the African continent.[186][185]

Two Almoravid-period marble columns have also been found reused as spolia in later monuments in Fes. One is incorporated into the window of the Dar al-Muwaqqit (timekeeper's house) overlooking the courtyard of the Qarawiyyin Mosque, built in the Marinid period. The other is embedded into the decoration of the exterior southern façade of the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II, a structure which was rebuilt by Ismail Ibn Sharif.[187]

The fact that Ibn Tumart, leader of the Almohad movement, is recorded as having criticized Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf for "sitting on a luxurious silken cloak" at his grand mosque in Marrakesh indicates the important role of textiles under the Almoravids.[188]

.jpg/440px-Fragment_with_wrestling_lions_and_harpies_-_Google_Art_Project_(cropped).jpg)

Many of the remaining fabrics from the Almoravid period were reused by Christians, with examples in the reliquary of San Isidoro in León, a chasuble from Saint-Sernin in Toulouse, the Chasuble of San Juan de Ortega in the church of Quintanaortuña (near Burgos), the shroud of San Pedro de Osma, and a fragment found at the church of Thuir in the eastern Pyrenees.[183][189][190][191] Some of these pieces are characterized by the appearance of Kufic or "Hispano-Kufic" woven inscriptions, with letters sometimes ending in ornamental vegetal flourishes. The Chasuble of San Juan de Ortega is one such example, made of silk and gold thread and dating to the first half of the 12th century.[189][190] The Shroud of San Pedro de Osma is notable for its inscription stating "this was made in Baghdad", suggesting that it was imported. However, more recent scholarship has suggested that the textile was instead produced locally in centres such as Almeria, but that they were copied or based on eastern imports.[189] It's even possible that the inscription was knowingly falsified in order to exaggerate its value to potential sellers; Al-Saqati of Málaga, a 12th-century writer and market inspector,[192] wrote that there were regulations designed to prohibit the practice of making such false inscriptions.[189] As a result of the inscription, many of these textiles are known in scholarship as the "Baghdad group", representing a stylistically coherent and artistically rich group of silken textiles seemingly dating to reign of Ali ibn Yusuf or the first half of the 12th century.[189] Aside from the inscription, the shroud of San Pedro de Osma is decorated with images of two lions and harpies inside roundels that are ringed by images of small men holding griffins, repeating across the whole fabric.[189] The chasuble from Saint-Sernin is likewise decorated with figural images, in this case a pair of peacocks repeating in horizontal bands, with vegetal stems separating each pair and small kufic inscriptions running along the bottom.[190]

The decorative theme of having a regular grid of roundels containing images of animals and figures, with more abstract motifs filling the spaces in between, has origins traced as far back as Persian Sasanian textiles. In subsequent periods, starting with the Almohads, these roundels with figurative imagery are progressively replaced with more abstract roundels, while epigraphic decoration becomes more prominent than before.[189]

In early Islamic manuscripts, Kufic was the main script used for religious texts. Western or Maghrebi Kufic evolved from the standard (or eastern) Kufic style and was marked by the transformation of the low swooping sections of letters from rectangular forms to long semi-circular forms. It is found in 10th century Qurans before the Almoravid period.[193] Almoravid Kufic is the variety of Maghrebi Kufic script that was used as an official display script during the Almoravid period.[194]

Eventually, Maghrebi Kufic gave rise to a distinctive cursive script known as "Maghrebi", the only cursive script of Arabic derived from Kufic, which was fully formed by the early 12th century under the Almoravids.[193] This style was commonly used in Qurans and other religious works from this period onward, but it was rarely ever used in architectural inscriptions.[195][193] One version of this script during this early period is the Andalusi script, which was associated with Al-Andalus. It was usually finer and denser, and while the loops of letters below the line are semi-circular, the extensions of letters above the line continue to use straight lines that recall its Kufic origins. Another version of the script is rounder and larger, and is more associated with the Maghreb, although it is nonetheless found in Andalusi volumes too.[193]

The oldest known illuminated Quran from the western Islamic world (i.e. the Maghreb and Al-Andalus) dates from 1090, towards the end of the first Taifas period and the beginning of the Almoravid domination in Al-Andalus.[196]: 304 [197] It was produced either in the Maghreb or Al-Andalus and is now kept at the Uppsala University Library. Its decoration is still in the earliest phases of artistic development, lacking the sophistication of later volumes, but many of the features that were standard in later manuscripts[198] are present: the script is written in the Maghrebi style in black ink, but the diacritics (vowels and other orthographic signs) are in red or blue, simple gold and black roundels mark the end of verses, and headings are written in gold Kufic inside a decorated frame and background.[196]: 304 It also contains a frontispiece, of relatively simple design, consisting of a grid of lozenges variously filled with gold vegetal motifs, gold netting, or gold Kufic inscriptions on red or blue backgrounds.[197]

More sophisticated illumination is already evident in a copy of a sahih dated to 1120 (during the reign of Ali ibn Yusuf), also produced in either the Maghreb or Al-Andalus, with a rich frontispiece centered around a large medallion formed by an interlacing geometric motif, filled with gold backgrounds and vegetal motifs.[199] A similarly sophisticated Quran, dated to 1143 (at the end of Ali ibn Yusuf's reign) and produced in Córdoba, contains a frontispiece with an interlacing geometric motif forming a panel filled with gold and a knotted blue roundel at the middle.[196]: 304

The Almoravid conquest of al-Andalus caused a temporary rupture in ceramic production, but it returned in the 12th century.[200] There is a collection of about 2,000 Maghrebi-Andalusi ceramic basins or bowls (bacini) in Pisa, where they were used to decorate churches from the early 11th to fifteenth centuries.[200] There were a number of varieties of ceramics under the Almoravids, including cuerda seca pieces.[200] The most luxurious form was iridescent lustreware, made by applying a metallic glaze to the pieces before a second firing.[200] This technique came from Iraq and flourished in Fatimid Egypt.[200]

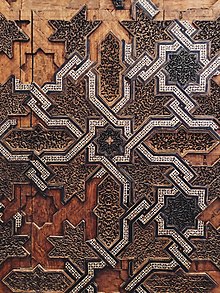

The Almoravid minbars—such as the minbar of the Grand Mosque of Marrakesh commissioned by Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf (1137), or the minbar for the University of al-Qarawiyyin (1144)[201][179]—expressed the Almoravids' Maliki legitimacy, their "inheritance of the Umayyad imperial role", and the extension of that imperial power into the Maghreb.[186] Both minbars are exceptional works of marquetry and woodcarving, decorated with geometric compositions, inlaid materials, and arabesque reliefs.[201][202][203]

The Almoravid period, along with the subsequent Almohad period, is considered one of the most formative stages of Moroccan and Moorish architecture, establishing many of the forms and motifs of this style that were refined in subsequent centuries.[204][205][206][207] Manuel Casamar Perez remarks that the Almoravids scaled back the Andalusi trend towards heavier and more elaborate decoration which had developed since the Caliphate of Córdoba and instead prioritized a greater balance between proportions and ornamentation.[208]

The two centers of artistic production in the Islamic west before the rise of the Almoravids were Kairouan and Córdoba, both former capitals in the region which served as sources of inspiration.[181] The Almoravids were responsible for establishing a new imperial capital at Marrakesh, which became a major center of architectural patronage thereafter. The Almoravids adopted the architectural developments of al-Andalus, such as the complex interlacing arches of the Great Mosque in Córdoba and of the Aljaferia palace in Zaragoza, while also introducing new ornamental techniques from the east such as muqarnas ("stalactite" or "honeycomb" carvings).[205][209]

.jpg/440px-Marrakesh_02_054_(4826882276).jpg)

After taking control of Al-Andalus in the Battle of Sagrajas, the Almoravids sent Muslim, Christian and Jewish artisans from Iberia to North Africa to work on monuments.[211] The Great Mosque in Algiers (c. 1097), the Great Mosque of Tlemcen (1136) and al-Qarawiyyin (expanded in 1135) in Fez are important examples of Almoravid architecture.[201] The Almoravid Qubba is one of the few Almoravid monuments in Marrakesh surviving, and is notable for its highly ornate interior dome with carved stucco decoration, complex arch shapes, and minor muqarnas cupolas in the corners of the structure.[212]: 114 The central nave of the expanded Qarawiyyin Mosque notably features the earliest full-fledged example of muqarnas vaulting in the western Islamic world. The complexity of these muqarnas vaults at such an early date—only several decades after the first simple muqarnas vaults appeared in distant Iraq—has been noted by architectural historians as surprising.[213]: 64 Another high point of Almoravid architecture is the intricate ribbed dome in front of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, which likely traces its origins to the 10th-century ribbed domes of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. The structure of the dome is strictly ornamental, consisting of multiple ribs or intersecting arches forming a twelve-pointed star pattern. It is also partly see-through, allowing some outside light to filter through a screen of pierced and carved arabesque decoration that fills the spaces between the ribs.[214][212]: 116–118

Aside from more ornamental religious structures, the Almoravids also built many fortifications, although most of these in turn were demolished or modified by the Almohads and later dynasties. The new capital, Marrakesh, initially had no city walls but a fortress known as the Ksar el-Hajjar ("Fortress of Stone") was built by the city's founder, Abu Bakr ibn Umar, in order to house the treasury and serve as an initial residence.[215][216] Eventually, circa 1126, Ali Ibn Yusuf also constructed a full set of walls, made of rammed earth, around the city in response to the growing threat of the Almohads.[215][216] These walls, although much restored and partly expanded in later centuries, continue to serve as the walls of the medina of Marrakesh today. The medina's main gates were also first built at this time, although many of them have since been significantly modified. Bab Doukkala, one of the western gates, is believed to have best preserved its original Almoravid layout.[217] It has a classic bent entrance configuration, of which variations are found throughout the medieval period of the Maghreb and Al-Andalus.[216][218]: 116 Elsewhere, the archaeological site of Tasghîmût, southeast of Marrakesh, and Amargu, northeast of Fes, provide evidence about other Almoravid forts. Built out of rubble stone or rammed earth, they illustrate similarities with older Hammadid fortifications, as well as an apparent need to build quickly during times of crisis.[204]: 219–220 [219] The walls of Tlemcen (present-day Algeria) were likewise partly built by the Almoravids, using a mix of rubble stone at the base and rammed earth above.[204]: 220

In domestic architecture, none of the Almoravid palaces or residences have survived, and they are known only through texts and archaeology. During his reign, Ali Ibn Yusuf added a large palace and royal residence on the south side of the Ksar el-Hajjar (on the present site of the Kutubiyya Mosque). This palace was later abandoned and its function was replaced by the Almohad Kasbah, but some of its remains have been excavated and studied in the 20th century. These remains have revealed the earliest known example in Morocco of a riad garden (an interior garden symmetrically divided into four parts).[220][204]: 404 In 1960 other excavations near Chichaoua revealed the remains of a domestic complex or settlement dating from the Almoravid period or even earlier. It consisted of several houses, two hammams, a water supply system, and possibly a mosque. On the site were found many fragments of architectural decoration which are now preserved at the Archeological Museum of Rabat. These fragments are made of deeply-carved stucco featuring Kufic and cursive Arabic inscriptions as well as vegetal motifs such as palmettes and acanthus leaves.[221] The structures also featured painted decoration in red ochre, typically consisting of border motifs composed of two interlacing bands. Similar decoration has also been found in the remains of former houses excavated in 2006 under the 12th-century Almoravid expansion of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes. In addition to the usual border motifs were larger interlacing geometric motifs as well as Kufic inscriptions with vegetal backgrounds, all executed predominantly in red.[195]

_Al-Mu’tamid.jpg/440px-Túmulo_do_poeta_português_(nascido_em_Beja)_Al-Mu’tamid.jpg)

The Almoravid movement has its intellectual origins in the writings and teachings of Abu Imran al-Fasi, who first inspired Yahya Ibn Ibrahim of the Guddala tribe in Kairouan. Ibn Ibrahim then inspired Abdallah ibn Yasin to organize for jihad and start the Almoravid movement.[222]

The Moroccan historian Muhammad al-Manuni noted that there were 104 paper mills in Fez under Yusuf ibn Tashfin in the 11th century.[223]

Moroccan literature flourished in the Almoravid period. The political unification of Morocco and al-Andalus under the Almoravid dynasty rapidly accelerated the cultural interchange between the two continents, beginning when Yusuf ibn Tashfin sent al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, former poet king of the Taifa of Seville, into exile in Tangier and ultimately Aghmat.[224]

The historians Ibn Hayyan, Al-Bakri, Ibn Bassam, and al-Fath ibn Khaqan all lived in the Almoravid period. Ibn Bassam authored Dhakhīra fī mahāsin ahl al-Jazīra ,[225] Al-Fath ibn Khaqan authored Qala'idu l-'Iqyan,[226] and Al-Bakri authored al-Masālik wa ’l-Mamālik (Book of Roads and Kingdoms).[227]

In the Almoravid period two writers stand out: Qadi Ayyad and Avempace. Ayyad is known for having authored Kitāb al-Shifāʾ bī Taʾrif Ḥuqūq al-Muṣṭafá.[228] Many of the Seven Saints of Marrakesh were men of letters.

The muwashshah was an important form of poetry and music in the Almoravid period. Great poets from the period are mentioned in anthologies such as Kharidat al Qasar ,[229] Rawd al-Qirtas, and Mu'jam as-Sifr.[230]

In the European portion of the Almoravid domain, poets such as Ibn Quzman produced popular zajal strophic poetry in vernacular Andalusi Arabic.[231] In the Almoravid period, several Andalusi poets expressed contempt for the city of Seville, the European capital of the Almoravids.[231][232]

Abdallah ibn Yasin imposed very strict disciplinary measures on his forces for every breach of his laws.[233] The Almoravids' first military leader, Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni, gave them a good military organization. Their main force was infantry, armed with javelins in the front ranks and pikes behind, which formed into a phalanx,[234] and was supported by camelmen and horsemen on the flanks.[64][234] They also had a flag carrier at the front who guided the forces behind him; when the flag was upright, the combatants behind would stand and when it was turned down, they would sit.[234]

Al-Bakri reports that, while in combat, the Almoravids did not pursue those who fled in front of them.[234] Their fighting was intense and they did not retreat when disadvantaged by an advancing opposing force; they preferred death over defeat.[234] These characteristics were possibly unusual at the time.[234]

After the death of El Cid, Christian chronicles reported a legend of a Turkish woman leading a band of 300 "Amazons", black female archers. This legend was possibly inspired by the ominous veils on the faces of the warriors and their dark skin colored blue by the indigo of their robes.[235]

Sanhaja tribal leaders recognizing the spiritual authority of Abdallah ibn Yasin (d. 1058 or 1059[a]):

Subsequent rulers:

As far west as the Maghrib, two Berber (Amazigh) dynasties that had emerged in the aftermath of the collapse of the Umayyad caliphate of Cordoba – the Almoravids (1040–1147), who were Abbasid vassals, and their autonomous Almohad successors (1121–1269) who claimed the caliphate for themselves...

The Almoravids, who acknowledged the spiritual authority of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, founded their capital at Marrakech and by 1082 had extended their control along the Mediterranean coast beyond present-day Algiers to the edge of the Kabylia region.

But, as was the rule throughout the history of al-Andalus, the Almoravid Berbers accepted Arab cultural patterns and Arabic as the language of administration and culture.

En outre, bien que les Almoravides aient parlé le berbère, l'arabe restait la langue officielle. [Furthermore, although the Almoravids spoke Berber, Arabic remained the official language.]

The Almoravids were an alliance of Sanhaja Berbers from the Guddala, Lamtuna and Massufa tribes, which formed in the 1040s in the area that is now Mauritania and Western Sahara.

The foundation of the town of Azūgi (vars. Azuggī, Azuḳḳī, Azukkī) as the southern capital of the Almoravids. It lies 10 km NW of Atar. According to al-Bakrī, it was a fortress, surrounded by 20,000 palms, and it had been founded by Yānnū b. ʿUmar al-Ḥād̲j̲d̲j̲, a brother of Yaḥyā b. ʿUmar. It seems likely that Azūgi became the seat of the Ḳāḍī Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-Murādī al-Ḥaḍramī (to cite both the Ḳāḍī ʿlyāḍ and Ibn Bas̲h̲kuwāl), who died there in 489/1095–96 (assuming Azūgi to be Azkid or Azkd). The town was for long regarded as the "capital of the Almoravids", well after the fall of the dynasty in Spain and even after its fall in the Balearic Islands. It receives a mention by al-Idrīsī, al-Zuhrī and other Arab geographers.

After the confrontation with Ibn Tashfin, Abu Bakr b. 'Umar returned to the desert, where he led the southern wing of the Almoravids in the jihad against the Sudanis. The base for his operations seems to have been the town of Azukki (Azugi, Arkar.) It is first mentioned as the fortress in Jabal Lamtuna (Adrar), where Yahya b. 'Umar was besieged and killed by the Juddala. Azukki, according to al-Bakri, was built by Yannu b. 'Umar, the brother of Yahya and Abu Bakr. Al-Idrisi mentions Azukki as an important Saharan town on the route from Sijilmasa to the Sudan, and adds that this was its Berber name, whereas Sudanis called it Kukadam (written as Quqadam).

Au milieu du Ve siecle H/XIe siecle ap. J.C., l'écrivain andalou al-Bakri fait état de l'existence à «Arki» d'une «forteresse...au milieu de 20 000 palmiers...édifiée par Yannu Ibn 'Umar al-Ḥāğ, frère de Yaḥya Ibn 'Umar... ». Cette brève mention est vraisemblablement a l'origine du qualificatif d'«almoravide» qu'en l'absence de toute investigation proprement archéologique, les historiens modernes ont généralement attribué aux ruines apparentes du tell archéologique d'Azūgi; nous y reviendrons. Au siecle suivant, al-Idrisi (1154) localise la «première des stations du Sahara...au pays des Massūfa et des Lamṭa» ; étape sur un itinéraire transsaharien joignant Siğilmāsa a Silla, Takrūr ou Gāna, Azūki, ou Kukdam en «langue gināwiyya des Sudan», abrite une population prospère. Pour brève et à nos yeux trop imprécise qu'elle soit, l'évocation d'al-Idrisi est néanmoins la plus étoffée de celles qui nous sont parvenues des auteurs «médiévaux» de langue arabe. Aucun écrivain contemporain d'al-Idrisi, ou postérieur, qu'il s'agisse d'al-Zuhri (ap. 1133), d'Ibn Sa'id et surtout d'Ibn Haldun—qui n'en prononce même pas le nom dans son récit pourtant complet de l'histoire du mouvement almoravide—ne nous fournit en effet d'élément nouveau sur Azūgi. À la fin du XVe siècle, au moment où apparaissent les navigateurs portugais sur les côtes sahariennes, al-Qalqašandi et al-Himyari ne mentionnent plus «Azūqi» ou «Azīfi» que comme un toponyme parmi d'autres au Bilād al-Sudān... Les sources écrites arabes des XIe–XVe siècles ne livrent donc sur Azūgi que de brèves notices, infiniment moins détaillées et prolixes que celles dont font l'objet, pour la même période et chez ces mêmes auteurs, certaines grandes cités toutes proches, telles Awdagust, Gāna, Kawkaw, Niani, Walāta, etc... Faut-il voir dans cette discrétion un témoignage «a silentio» sur l'affaiblissement matériel d'une agglomération—une «ville» au sens où l'entendent habituellement les auteurs cités?—dont al-Idrisi affirme effectivement qu'elle n'est point une grande ville»?

L'historien El Bekri, dans sa Description de l'Afrique septentrionale, parle de l'ancienne fortresse d'Azougui, située dans une grande palmeraie de l'Adrar mauritanien, comme ayant été la véritable capital des sultans almoravides, avant leur épopée maroco-espagnole. Elle ne dut connaître qu'une splendeur éphémère, car depuis la fin du XIIe siècle son nom disparaît des chroniques.

Il est souhaitable que les fouilles prévues à Azougui, première « capitale » fondée par les Almoravides (avant Marrakech) puissent être prochainement réalisées.

Its present capital is Āṭār, though in the mediaeval period its principal towns were Azuqqi (Azougui), which, for a while, was the "capital" of the southern wing of the Almoravid movement, (...)