Recep Tayyip Erdoğan [b] (nacido el 26 de febrero de 1954) es un político turco que es el duodécimo y actual presidente de Turquía desde 2014. Anteriormente se desempeñó como el 25º primer ministro de 2003 a 2014 como parte del Partido de Justicia y Desarrollo (AKP), que cofundó en 2001. También se desempeñó como alcalde de Estambul de 1994 a 1998.

Erdoğan nació en Beyoğlu , Estambul , y estudió en la Academia Aksaray de Ciencias Económicas y Comerciales , antes de trabajar como consultor y gerente senior en el sector privado. Se volvió activo en la política local, fue elegido presidente del distrito de Beyoğlu del Partido del Bienestar en 1984 y presidente de Estambul en 1985. Después de las elecciones locales de 1994 , Erdoğan fue elegido alcalde de Estambul. Dijo en ese momento: " La democracia es como un tren: cuando llegamos a nuestro destino, nos bajamos ". [4] En 1998 fue condenado por incitar al odio religioso y prohibido de la política después de recitar un poema de Ziya Gökalp que comparaba las mezquitas con cuarteles y a los fieles con un ejército. Erdoğan fue liberado de prisión en 1999 y formó el AKP, abandonando las políticas abiertamente islamistas.

Erdoğan llevó al AKP a una victoria aplastante en las elecciones para la Gran Asamblea Nacional en 2002, y se convirtió en primer ministro después de ganar una elección parcial en Siirt en 2003. Erdoğan llevó al AKP a dos victorias electorales más en 2007 y 2011. Su mandato consistió en la recuperación económica de la crisis económica de 2001 , el inicio de las negociaciones de membresía de la UE y la reducción de la influencia militar en la política . A fines de 2012, su gobierno comenzó las negociaciones de paz con el Partido de los Trabajadores del Kurdistán (PKK) para poner fin al conflicto kurdo-turco , negociaciones que finalizaron tres años después.

En 2014, Erdoğan se convirtió en el primer presidente elegido directamente del país . La presidencia de Erdoğan ha estado marcada por un retroceso democrático y un cambio hacia un estilo de gobierno más autoritario . Sus políticas económicas han provocado altas tasas de inflación y la depreciación del valor de la lira turca . Ha intervenido en los conflictos en curso en Siria y Libia , lanzó operaciones contra el Estado Islámico , las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias y las fuerzas de Asad , y ha hecho amenazas contra Grecia . Supervisó la transformación del sistema parlamentario de Turquía en un sistema presidencial , introduciendo límites de mandato y ampliando los poderes ejecutivos, y la crisis migratoria de Turquía . Erdoğan respondió a la invasión rusa de Ucrania en 2022 cerrando el Bósforo a los refuerzos navales rusos, negociando un acuerdo entre Rusia y Ucrania sobre la exportación de cereales y mediando en un intercambio de prisioneros. [5]

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan nació el 26 de febrero de 1954 en una familia musulmana conservadora pobre . [6] [7] La familia de Erdoğan es originaria de Adjara , una región de Georgia . [8] Aunque se informó que Erdoğan dijo en 2003 que era de origen georgiano y que sus orígenes estaban en Batumi , [7] [9] más tarde lo negó. [7] Sus padres fueron Ahmet Erdoğan (1905-1988) y Tenzile Erdoğan ( née Mutlu; 1924-2011). [10]

Mientras Erdoğan asistía a la escuela en Estambul, pasaba la mayor parte de sus vacaciones de verano en Güneysu , Rize, de donde es originaria su familia. A lo largo de su vida, volvió a menudo a este hogar espiritual y en 2015 abrió una enorme mezquita en la cima de una montaña cerca de este pueblo. [11] La familia regresó a Estambul cuando Erdoğan tenía 13 años. [12]

Cuando era adolescente, el padre de Erdoğan le proporcionaba una asignación semanal de 2,5 liras turcas, menos de un dólar. Con ella, Erdoğan compraba postales y las revendía en la calle. Vendía botellas de agua a los conductores atrapados en el tráfico. Erdoğan también trabajaba como vendedor ambulante vendiendo simit (anillos de pan de sésamo), vistiendo una bata blanca y vendiendo el simit desde un carrito rojo de tres ruedas con los panecillos apilados detrás de un cristal. [12] En su juventud, Erdoğan jugó al fútbol semiprofesional en el Camialtıspor FC, un club local. [13] [1] [14] [15] Fenerbahçe quería que se transfiriera al club [ aclaración necesaria ] pero su padre lo impidió. [16] El estadio del club de fútbol local en el distrito donde creció, Kasımpaşa SK, lleva su nombre. [17] [18]

Erdoğan es miembro de la Comunidad de İskenderpaşa , una comunidad sufista turca de la tariqah Naqshbandi . [19] [20]

Erdoğan se graduó de la Escuela Primaria Kasımpaşa Piyale en 1965, y de la Escuela Secundaria İmam Hatip de Estambul , una escuela secundaria vocacional religiosa, en 1973. [21] El mismo camino educativo fue seguido por otros cofundadores del Partido AK . [22] Una cuarta parte del plan de estudios de las escuelas İmam Hatip implica el estudio del Corán , la vida del profeta islámico Mahoma y el idioma árabe . Erdoğan estudió el Corán en el İmam Hatip, donde sus compañeros de clase comenzaron a llamarlo hoca ("maestro" o "oficial religioso").

Erdoğan asistió a una reunión del grupo estudiantil nacionalista Unión Nacional de Estudiantes Turcos ( Milli Türk Talebe Birliği ), que buscaba formar una cohorte conservadora de jóvenes para contrarrestar el creciente movimiento de izquierdas en Turquía. Dentro del grupo, Erdoğan se distinguió por sus habilidades oratorias, desarrollando una inclinación por hablar en público y sobresaliendo frente a una audiencia. Ganó el primer lugar en un concurso de lectura de poesía organizado por la Comunidad de Pintores Técnicos Turcos, y comenzó a prepararse para discursos mediante la lectura y la investigación. Erdoğan comentaría más tarde sobre estos concursos como "un aumento de nuestro coraje para hablar frente a las masas". [23]

Erdoğan quería realizar estudios superiores en la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas de la Universidad de Ankara , conocida comúnmente como Mülkiye, pero sólo los estudiantes con diplomas de bachillerato regular podían solicitarlo, excluyendo así a los graduados de Imam Hatip. Mülkiye era conocida por su departamento de ciencias políticas, que formó a muchos estadistas y políticos en Turquía. Erdoğan fue entonces admitido en la Escuela Secundaria Eyüp, una escuela estatal regular. El hecho de que finalmente recibiera un diploma de bachillerato de esta escuela es un tema de debate. [24] [25]

Según su biografía oficial, Erdoğan posteriormente estudió administración de empresas en la Escuela de Economía y Ciencias Comerciales de Aksaray ( en turco : Aksaray İktisat ve Ticaret Yüksekokulu ), ahora conocida como la Facultad de Economía y Ciencias Administrativas de la Universidad de Mármara . [1] Tanto la autenticidad como el estatus de su título han sido objeto de disputas y controversias sobre si el diploma es legítimo y debe considerarse suficiente para hacerlo elegible como candidato a la presidencia. [26]

En 1976, Erdoğan se dedicó a la política al unirse a la Unión Nacional de Estudiantes Turcos, un grupo de acción anticomunista . Ese mismo año, se convirtió en jefe de la sección juvenil de Beyoğlu del Partido de Salvación Nacional (MSP) islamista, [27] y más tarde fue ascendido a presidente de la sección juvenil de Estambul. [21] Ocupó este puesto hasta el golpe militar de 1980 que disolvió todos los partidos políticos principales. Pasó a ser consultor y alto ejecutivo en el sector privado tras el golpe.

Tres años después, en 1983, Erdoğan siguió los pasos de la mayoría de los seguidores de Necmettin Erbakan y se unió al recién fundado Partido del Bienestar (PR). El nuevo partido, al igual que sus predecesores, se adhirió a la corriente islamista de Erbakan , la Visión Nacional . Erdoğan se convirtió en presidente del distrito de Beyoğlu en 1984 y jefe de su rama de Estambul en 1985. Erdoğan se presentó a las elecciones parlamentarias parciales de 1986 como candidato en el sexto distrito electoral de Estambul, pero no logró ser elegido. Tres años después, Erdoğan se presentó a la alcaldía del distrito de Beyoğlu, quedando en segundo lugar con el 22,8% de los votos. [28]

En las elecciones generales de 1991 , el Partido del Bienestar duplicó con creces su porcentaje de votos en Estambul en comparación con cuatro años antes, alcanzando el 16,7%. En un principio, se pensó que Erdoğan, que encabezaba la lista de distrito de su partido, había sido elegido para el parlamento. Sin embargo, como producto del sistema de representación proporcional de lista abierta adoptado durante el mandato anterior, después de que se tabularan todos los votos que expresaban una preferencia por un candidato, fue Mustafa Baş quien obtuvo el escaño asignado al Partido del Bienestar. Una diferencia de aproximadamente 4.000 votos preferenciales separó a los dos, con ~13.000 de Baş frente a ~9.000 de Erdoğan. [29]

En las elecciones locales de 1994 , Erdoğan se presentó como candidato a la alcaldía de Estambul . Era un candidato joven y desconocido en un campo abarrotado. A lo largo de la campaña, los medios de comunicación se burlaron de él y sus oponentes lo trataron como un patán. [30] En una sorpresa, ganó con el 25,19% del voto popular, lo que lo convirtió en la primera vez que un alcalde de Estambul era elegido de su partido político. Su victoria coincidió con una ola de victorias del Partido del Bienestar en todo el país, ya que ganaron 28 alcaldías provinciales (la mayor cantidad de cualquier partido) y numerosos escaños metropolitanos, incluida la capital, Ankara.

Erdoğan gobernó de manera pragmática, centrándose en cuestiones básicas. Su objetivo era abordar los problemas crónicos que asolaban la metrópoli, como la escasez de agua , la contaminación (en particular los problemas de recolección de residuos) y el tráfico gravemente congestionado. Emprendió una renovación de la infraestructura: amplió y modernizó la red de agua con la instalación de cientos de kilómetros de nuevas tuberías y construyó más de cincuenta puentes, viaductos y tramos de autopista para mitigar el tráfico. Se construyeron instalaciones de reciclaje de última generación y se redujo la contaminación del aire mediante un plan para cambiar al gas natural. Cambió los autobuses públicos por otros respetuosos con el medio ambiente. Tomó precauciones para prevenir la corrupción, utilizando medidas para garantizar que los fondos municipales se utilizaran con prudencia. Pagó una parte importante de la deuda de dos mil millones de dólares de la Municipalidad Metropolitana de Estambul e invirtió cuatro mil millones de dólares en la ciudad. [31] También abrió el Ayuntamiento a la gente, dio su dirección de correo electrónico y estableció líneas directas municipales. [32]

Erdoğan inició la primera mesa redonda de alcaldes durante la conferencia de Estambul , que dio lugar a un movimiento mundial organizado de alcaldes. Un jurado internacional de siete miembros de las Naciones Unidas otorgó por unanimidad a Erdoğan el premio ONU-Hábitat . [33]

En diciembre de 1997 en Siirt , Erdoğan recitó una versión modificada del poema "La oración del soldado" escrito por Ziya Gökalp , un activista pan-turco de principios del siglo XX. [34] Esta versión incluía una estrofa adicional al principio, sus dos primeros versos decían "Las mezquitas son nuestros cuarteles, las cúpulas nuestros cascos / Los minaretes nuestras bayonetas y los fieles nuestros soldados..." [12] Según el artículo 312/2 del código penal turco, su recitación fue considerada por el juez como una incitación a la violencia y al odio religioso o racial. [35] [36] [34] En su defensa, Erdoğan dijo que el poema fue publicado en libros aprobados por el estado. [32] Cómo esta versión del poema terminó en un libro publicado por la Institución de Normas Turcas siguió siendo un tema de discusión. [37]

Erdoğan fue condenado a diez meses de prisión. [36] Se vio obligado a renunciar a su puesto de alcalde debido a su condena. La condena también estipuló una prohibición política, que le impedía participar en las elecciones. [38] Había apelado para que la sentencia se convirtiera en una multa monetaria, pero en su lugar se redujo a cuatro meses (del 24 de marzo de 1999 al 27 de julio de 1999). [39]

Erdoğan fue trasladado a la prisión de Pınarhisar en Kırklareli . El día que Erdoğan fue a prisión, lanzó un álbum llamado This Song Doesn't End Here . [40] El álbum presenta una lista de canciones de siete poemas y se convirtió en el álbum más vendido de Turquía en 1999, vendiendo más de un millón de copias. [41] En 2013, Erdoğan visitó la prisión de Pınarhisar nuevamente por primera vez en catorce años. Después de la visita, dijo: "Para mí, Pınarhisar es un símbolo de renacimiento, donde preparamos el establecimiento del Partido de la Justicia y el Desarrollo". [42]

Erdoğan fue miembro de partidos políticos que fueron prohibidos por el ejército o los jueces. Dentro de su Partido de la Virtud , hubo una disputa sobre el discurso apropiado del partido entre los políticos tradicionales y los políticos pro-reforma. Estos últimos imaginaron un partido que pudiera operar dentro de los límites del sistema, y por lo tanto no ser prohibido como sus predecesores como el Partido del Orden Nacional , el Partido de Salvación Nacional y el Partido del Bienestar . Querían darle al grupo el carácter de un partido conservador ordinario con sus miembros siendo demócratas musulmanes siguiendo el ejemplo de los demócratas cristianos de Europa . [32]

Cuando en 2001 también se prohibió el Partido de la Virtud, se produjo una división definitiva: los seguidores de Necmettin Erbakan fundaron el Partido de la Felicidad (SP) y los reformistas fundaron el Partido de la Justicia y el Desarrollo (AKP) bajo el liderazgo de Abdullah Gül y Erdoğan. Los políticos pro-reforma se dieron cuenta de que un partido estrictamente islámico nunca sería aceptado como partido gobernante por el aparato estatal y creían que un partido islámico no atraía a más de un 20 por ciento del electorado turco. El partido AK se presentó enfáticamente como un partido conservador democrático amplio con nuevos políticos del centro político (como Ali Babacan y Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu ), al tiempo que respetaba las normas y valores islámicos, pero sin un programa religioso explícito. Esto resultó ser un éxito ya que el nuevo partido ganó el 34% de los votos en las elecciones generales de 2002. Erdoğan se convirtió en primer ministro en marzo de 2003 después de que el gobierno de Gül pusiera fin a su prohibición política. [43]

.jpg/440px-Mariano_Rajoy_visiting_Recep_Tayyip_Erdoğan_in_Turkey_(5).jpg)

Las elecciones de 2002 fueron las primeras en las que Erdoğan participó como líder de un partido. Todos los partidos elegidos previamente para el parlamento no lograron obtener suficientes votos para volver a ingresar al parlamento. El AKP ganó el 34,3% del voto nacional y formó el nuevo gobierno. Las acciones turcas subieron más del 7% el lunes por la mañana. Los políticos de la generación anterior, como Ecevit , Bahceli , Yılmaz y Çiller , dimitieron. El segundo partido más grande, el CHP, recibió el 19,4% de los votos. El AKP obtuvo una victoria aplastante en el parlamento, obteniendo casi dos tercios de los escaños. Erdoğan no pudo convertirse en primer ministro porque el poder judicial aún lo prohibía participar en la política por su discurso en Siirt. Gül se convirtió en primer ministro en su lugar. En diciembre de 2002, la Junta Electoral Suprema anuló los resultados de las elecciones generales de Siirt debido a irregularidades en la votación y programó una nueva elección para el 9 de febrero de 2003 . En ese momento, el líder del partido Erdoğan pudo presentarse como candidato al parlamento gracias a un cambio legal hecho posible por el opositor Partido Republicano del Pueblo. El AKP incluyó a Erdoğan como candidato para las elecciones reprogramadas, que ganó y se convirtió en primer ministro después de que Gül entregara el cargo. [44]

El 14 de abril de 2007, aproximadamente 300.000 personas marcharon en Ankara para protestar contra la posible candidatura de Erdoğan en las elecciones presidenciales de 2007, temerosos de que, si era elegido presidente, alteraría la naturaleza secular del Estado turco. [45] Erdoğan anunció el 24 de abril de 2007 que el partido había nominado a Abdullah Gül como candidato del AKP en las elecciones presidenciales. [46] [47] Las protestas continuaron durante las siguientes semanas; se informó de que más de un millón de personas participaron en una manifestación el 29 de abril en Estambul, [48] decenas de miles en protestas separadas el 4 de mayo en Manisa y Çanakkale , [49] y un millón en Esmirna el 13 de mayo. [50]

El escenario de las elecciones de 2007 estaba preparado para una lucha por la legitimidad a los ojos de los votantes entre su gobierno y el CHP. Erdoğan utilizó el evento que tuvo lugar durante las desafortunadas elecciones presidenciales unos meses antes como parte de la campaña electoral general de su partido. El 22 de julio de 2007, el AKP obtuvo una importante victoria sobre la oposición, obteniendo el 46,7% del voto popular. Las elecciones del 22 de julio marcaron la segunda vez en la historia de la República de Turquía en la que un partido gobernante en el poder ganó una elección al aumentar su porcentaje de apoyo popular. [51] El 14 de marzo de 2008, el Fiscal General de Turquía solicitó al Tribunal Constitucional del país que prohibiera el partido gobernante de Erdoğan. [52] El partido se libró de la prohibición el 30 de julio de 2008, un año después de ganar el 46,7% de los votos en las elecciones nacionales, aunque los jueces redujeron la financiación pública del partido en un 50%. [53]

En las elecciones de junio de 2011, el partido gobernante de Erdoğan obtuvo 327 escaños (49,83% del voto popular), lo que lo convirtió en el único primer ministro en la historia de Turquía en ganar tres elecciones generales consecutivas, recibiendo cada vez más votos que en la elección anterior. El segundo partido, el Partido Republicano del Pueblo (CHP), obtuvo 135 escaños (25,94%), el nacionalista MHP obtuvo 53 escaños (13,01%) y los Independientes obtuvieron 35 escaños (6,58%). [54]

En 2013, un escándalo de corrupción por 100 mil millones de dólares llevó al arresto de aliados cercanos de Erdoğan y lo incriminó. [55] [56] [57]

Después de que los partidos de oposición bloquearan las elecciones presidenciales de 2007 boicoteando el parlamento, el gobernante AKP propuso un paquete de reformas constitucionales. El paquete de reformas fue vetado primero por el presidente Ahmet Necdet Sezer . Luego presentó una solicitud al tribunal constitucional turco sobre el paquete de reformas, porque el presidente no puede vetar enmiendas por segunda vez. El tribunal constitucional turco no encontró ningún problema en el paquete y el 68,95% de los votantes apoyaron los cambios constitucionales. [58] Las reformas consistieron en elegir al presidente por voto popular en lugar de por el parlamento; reducir el mandato presidencial de siete años a cinco; permitir que el presidente se presente a la reelección para un segundo mandato; celebrar elecciones generales cada cuatro años en lugar de cinco; y reducir de 367 a 184 el quórum de legisladores necesario para las decisiones parlamentarias.

La reforma de la Constitución fue una de las principales promesas del AKP durante la campaña electoral de 2007. El principal partido de oposición, el CHP, no estaba interesado en alterar la Constitución a gran escala, lo que hizo imposible formar una Comisión Constitucional ( Anayasa Uzlaşma Komisyonu ). [59] Las enmiendas carecían de la mayoría de dos tercios necesaria para convertirse en ley instantáneamente, pero consiguieron 336 votos en el parlamento de 550 escaños, suficientes para someter las propuestas a referéndum. El paquete de reformas incluía una serie de cuestiones como el derecho de los individuos a apelar ante el tribunal más alto, la creación de la oficina del defensor del pueblo ; la posibilidad de negociar un contrato laboral a nivel nacional; la igualdad de género; la capacidad de los tribunales civiles para condenar a miembros del ejército; el derecho de los funcionarios públicos a hacer huelga; una ley de privacidad; y la estructura del Tribunal Constitucional . El referéndum fue aprobado por una mayoría del 58%. [60]

En 2009, el gobierno del primer ministro Erdoğan anunció un plan para ayudar a poner fin al conflicto de un cuarto de siglo entre Turquía y el Partido de los Trabajadores del Kurdistán que había costado más de 40.000 vidas. El plan del gobierno, apoyado por la Unión Europea , pretendía permitir que se utilizara el idioma kurdo en todos los medios de difusión y campañas políticas, y restableció los nombres kurdos a las ciudades y pueblos que habían recibido nombres turcos . [61] Erdoğan dijo: "Hemos dado un paso valiente para resolver los problemas crónicos que constituyen un obstáculo para el desarrollo, el progreso y el empoderamiento de Turquía". [61] Erdoğan aprobó una amnistía parcial para reducir las penas que enfrentaban muchos miembros del movimiento guerrillero kurdo PKK que se habían rendido al gobierno. [62] El 23 de noviembre de 2011, durante una reunión televisada de su partido en Ankara, se disculpó en nombre del estado por la masacre de Dersim , donde murieron muchos alevíes y zazas . [63] En 2013, el gobierno de Erdoğan inició un proceso de paz entre el Partido de los Trabajadores del Kurdistán (PKK) y el gobierno turco, [64] mediado por parlamentarios del Partido Democrático de los Pueblos (HDP). [65]

En 2015, tras la derrota electoral del AKP, el ascenso de un partido de oposición socialdemócrata y pro-kurdo , y el pequeño incidente de Ceylanpınar , decidió que el proceso de paz había terminado y apoyó la revocación de la inmunidad parlamentaria de los parlamentarios del HDP. [66] La confrontación violenta se reanudó en 2015-2017, principalmente en el sureste de Turquía, lo que resultó en un mayor número de muertos y varias operaciones externas por parte del ejército turco. Los representantes y los electos del HDP han sido sistemáticamente arrestados, removidos y reemplazados en sus cargos, tendencia que se confirmó después del intento de golpe de Estado turco de 2016 y las purgas posteriores . Se produjeron seis mil muertes adicionales solo en Turquía durante 2015-2022. Sin embargo, a partir de 2022, la intensidad del conflicto PKK-Turquía disminuyó en los últimos años. [67] En la década anterior, Erdogan y el gobierno del AKP utilizaron la retórica marcial contra el PKK y operaciones externas para aumentar los votos nacionalistas turcos antes de las elecciones. [68] [69] [70]

Erdoğan ha dicho varias veces que Turquía reconocería las matanzas masivas de armenios durante la Primera Guerra Mundial como genocidio solo después de una investigación exhaustiva por parte de una comisión conjunta turco-armenia compuesta por historiadores, arqueólogos , politólogos y otros expertos. [71] [72] [73] En 2005, Erdoğan y el líder del principal partido de oposición, Deniz Baykal, escribieron una carta al presidente de Armenia, Robert Kocharyan , proponiendo la creación de una comisión conjunta turco-armenia. [74] El ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Armenia, Vartan Oskanian, rechazó la oferta porque afirmó que la propuesta en sí era "insincera y no seria". Añadió: "Esta cuestión no puede considerarse a nivel histórico con los turcos, que ellos mismos politizaron el problema". [75] [76]

En diciembre de 2008, Erdoğan criticó la campaña “Me disculpo” de los intelectuales turcos para reconocer el genocidio armenio, diciendo: “No acepto ni apoyo esta campaña. No cometimos ningún crimen, por lo tanto no necesitamos disculparnos… No tendrá ningún beneficio más que provocar problemas, perturbar nuestra paz y deshacer los pasos que se han tomado”. [77]

En 2011, Erdoğan ordenó el derribo del Monumento a la Humanidad de 33 metros de altura (108 pies) , un monumento de amistad turco-armenia en Kars , que se encargó en 2006 y representaba una metáfora del acercamiento de los dos países después de muchos años de disputa por los acontecimientos de 1915. Erdoğan justificó la eliminación afirmando que el monumento estaba ofensivamente cerca de la tumba de un erudito islámico del siglo XI, y que su sombra arruinaba la vista de ese sitio, mientras que los funcionarios del municipio de Kars dijeron que fue erigido ilegalmente en un área protegida. Sin embargo, el ex alcalde de Kars que aprobó la construcción original del monumento dijo que el municipio estaba destruyendo no solo un "monumento a la humanidad", sino "la humanidad misma". La demolición no estuvo exenta de oposición; entre sus detractores hubo varios artistas turcos. Dos de ellos, el pintor Bedri Baykam y su socio, el coordinador general de la Galería de Arte Pirámide, Tugba Kurtulmus, fueron apuñalados después de una reunión con otros artistas en el centro cultural Akatlar de Estambul. [78]

El 23 de abril de 2014, la oficina de Erdoğan emitió una declaración en nueve idiomas (incluidos dos dialectos del armenio) en la que expresaba sus condolencias por las matanzas de armenios y afirmaba que los acontecimientos de 1915 habían tenido consecuencias inhumanas. La declaración describía las matanzas como un dolor compartido por las dos naciones y decía: “Haber vivido acontecimientos que tuvieron consecuencias inhumanas –como la reubicación– durante la Primera Guerra Mundial no debería impedir que turcos y armenios establezcan entre sí actitudes compasivas y mutuamente humanas”. [79]

En abril de 2015, en una misa especial en la Basílica de San Pedro para conmemorar el centenario de los acontecimientos, el Papa Francisco describió las atrocidades cometidas contra los civiles armenios entre 1915 y 1922 como "el primer genocidio del siglo XX". En protesta, Erdoğan retiró al embajador turco del Vaticano y convocó al embajador del Vaticano para expresar su "decepción" por lo que llamó un mensaje discriminatorio. Más tarde declaró que "no llevamos una mancha o una sombra como el genocidio". El presidente estadounidense, Barack Obama, pidió un "reconocimiento pleno, franco y justo de los hechos", pero nuevamente se abstuvo de etiquetarlo como "genocidio", a pesar de su promesa de campaña de hacerlo. [80] [81] [82]

Durante el mandato de Erdoğan como Primer Ministro, se redujeron los amplios poderes de la Ley Antiterrorista de 1991. En 2004, se abolió la pena de muerte en todas las circunstancias. [83] Se inició el proceso de iniciativa democrática , con el objetivo de mejorar los estándares democráticos en general y los derechos de las minorías étnicas y religiosas en particular. En 2012, se establecieron la Institución de Derechos Humanos e Igualdad de Turquía y la Institución del Defensor del Pueblo . Se ratificó el Protocolo Facultativo de la Convención contra la Tortura de las Naciones Unidas . Los niños ya no son procesados en virtud de la legislación antiterrorista. [84] A la comunidad judía se le permitió celebrar Hanukkah públicamente por primera vez en la historia moderna de Turquía en 2015. [85] El gobierno turco aprobó una ley en 2008 para devolver las propiedades confiscadas en el pasado por el estado a fundaciones no musulmanas. [86] También allanó el camino para la asignación gratuita de lugares de culto, como sinagogas e iglesias, a fundaciones no musulmanas. [87] Sin embargo, los funcionarios europeos notaron un retorno a formas más autoritarias después del estancamiento de la propuesta de Turquía de unirse a la Unión Europea [88] en particular en materia de libertad de expresión , [89] [90] [91] libertad de prensa [92] [93] [94] y derechos de la minoría kurda . [95] [96] [97] [98] Las demandas de los activistas para el reconocimiento de los derechos LGBT fueron rechazadas públicamente por los miembros del gobierno. [99] [100]

Reporteros sin Fronteras informó de una disminución continua de la libertad de prensa durante los últimos mandatos de Erdoğan, con una clasificación de alrededor de 100 en su Índice de Libertad de Prensa durante su primer mandato y una clasificación de 153 de un total de 179 países en 2021. [101] Freedom House informó de una ligera recuperación en los últimos años y otorgó a Turquía una puntuación de libertad de prensa de 55/100 en 2012 después de un punto bajo de 48/100 en 2006. [102] [103] [104] [105]

En 2011, el gobierno de Erdoğan realizó reformas legales para devolver las propiedades de las minorías cristianas y judías que fueron confiscadas por el gobierno turco en la década de 1930. [106] El valor total de las propiedades devueltas alcanzó los 2 mil millones de dólares (USD). [107]

Bajo el gobierno de Erdoğan, el gobierno turco endureció las leyes sobre la venta y el consumo de alcohol , prohibiendo toda publicidad y aumentando el impuesto a las bebidas alcohólicas. [108]

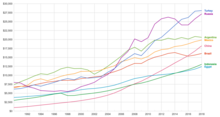

En 2002, Erdoğan heredó una economía turca que estaba empezando a recuperarse de una recesión como resultado de las reformas implementadas por Kemal Derviş . [109] Erdoğan apoyó al Ministro de Finanzas Ali Babacan en la aplicación de políticas macroeconómicas. Erdoğan intentó atraer más inversores extranjeros a Turquía y levantó muchas regulaciones gubernamentales. El flujo de efectivo en la economía turca entre 2002 y 2012 causó un crecimiento del 64% en el PIB real y un aumento del 43% en el PIB per cápita; comúnmente se anunciaron números considerablemente más altos, pero estos no tomaron en cuenta la inflación del dólar estadounidense entre 2002 y 2012. [110] El crecimiento anual promedio del PIB per cápita fue del 3,6%. El crecimiento del PIB real entre 2002 y 2012 fue mayor que los valores de los países desarrollados, pero estuvo cerca del promedio cuando también se tienen en cuenta los países en desarrollo. La posición de la economía turca en términos de PIB pasó ligeramente del puesto 17 al 16 durante esta década. Una consecuencia importante de las políticas aplicadas entre 2002 y 2012 fue la ampliación del déficit de cuenta corriente de 600 millones de dólares a 58.000 millones de dólares (estimación de 2013) [111].

Desde 1961, Turquía ha firmado 19 acuerdos de préstamo con el FMI. El gobierno de Erdoğan satisfizo los requisitos presupuestarios y de mercado de los dos durante su administración y recibió cada cuota del préstamo, la única vez que un gobierno turco ha hecho esto. [112] Erdoğan heredó una deuda de $ 23,5 mil millones con el FMI, que se redujo a $ 0,9 mil millones en 2012. Decidió no firmar un nuevo acuerdo. La deuda de Turquía con el FMI se declaró así completamente pagada y anunció que el FMI podría pedir préstamos a Turquía. [113] En 2010, los swaps de incumplimiento crediticio a cinco años para la deuda soberana de Turquía se negociaban a un mínimo histórico de 1,17%, por debajo de los de nueve países miembros de la UE y Rusia. En 2002, el Banco Central Turco tenía $ 26,5 mil millones en reservas. Esta cantidad alcanzó los 92.200 millones de dólares en 2011. Durante el liderazgo de Erdoğan, la inflación cayó del 32% al 9,0% en 2004. Desde entonces, la inflación turca ha seguido fluctuando alrededor del 9% y sigue siendo una de las tasas de inflación más altas del mundo. [114] La deuda pública turca como porcentaje del PIB anual disminuyó del 74% en 2002 al 39% en 2009. En 2012, Turquía tenía una proporción de deuda pública a PIB menor que 21 de los 27 miembros de la Unión Europea y una proporción de déficit presupuestario a PIB menor que 23 de ellos. [115]

En 2003, el gobierno de Erdoğan impulsó la Ley del Trabajo, una reforma integral de las leyes laborales de Turquía. La ley amplió considerablemente los derechos de los empleados, estableciendo una semana laboral de 45 horas y limitando las horas extras a 270 horas al año, brindó protección legal contra la discriminación por motivos de sexo, religión o afiliación política, prohibió la discriminación entre trabajadores permanentes y temporales, dio derecho a una indemnización a los empleados despedidos sin "causa válida" y ordenó la firma de contratos escritos para los contratos de trabajo de un año o más de duración. [116] [117]

Erdoğan aumentó el presupuesto del Ministerio de Educación de 7.500 millones de liras en 2002 a 34.000 millones de liras en 2011, la mayor proporción del presupuesto nacional otorgada a un ministerio. [118] Antes de su mandato como primer ministro, el ejército recibía la mayor parte del presupuesto nacional. La educación obligatoria se aumentó de ocho años a doce. [119] En 2003, el gobierno turco, junto con UNICEF , inició una campaña llamada "¡Vamos niñas, [vamos] a la escuela!" ( en turco : Haydi Kızlar Okula! ). El objetivo de esta campaña era cerrar la brecha de género en la matriculación en la escuela primaria mediante la provisión de una educación básica de calidad para todas las niñas, especialmente en el sureste de Turquía. [120]

En 2005, el parlamento concedió una amnistía a los estudiantes expulsados de las universidades antes de 2003. La amnistía se aplicó a los estudiantes expulsados por motivos académicos o disciplinarios. [121] En 2004, los libros de texto se volvieron gratuitos y desde 2008 cada provincia de Turquía tiene su propia universidad. [122] Durante el mandato de Erdoğan, el número de universidades en Turquía casi se duplicó, de 98 en 2002 a 186 en octubre de 2012. [123]

El Primer Ministro cumplió sus promesas de campaña al iniciar el proyecto Fatih , en el que todas las escuelas estatales, desde el nivel preescolar hasta el secundario, recibieron un total de 620.000 pizarrones inteligentes, mientras que se distribuyeron tabletas a 17 millones de estudiantes y aproximadamente a un millón de profesores y administradores. [124]

En junio de 2017, Erdoğan aprobó un proyecto de propuesta del Ministerio de Educación según el cual el plan de estudios de las escuelas excluiría la enseñanza de la teoría de la evolución de Charles Darwin a partir de 2019. A partir de entonces, la enseñanza se pospondría y comenzaría en el nivel de pregrado. [125]

Bajo el gobierno de Erdoğan, el número de aeropuertos en Turquía aumentó de 26 a 50 en un período de 10 años. [128] Entre la fundación de la República de Turquía en 1923 y 2002, se habían creado 6.000 km de carreteras de doble calzada . Entre 2002 y 2011, se construyeron otros 13.500 km de autopistas. Debido a estas medidas, el número de accidentes de tráfico se redujo en un 50 por ciento. [129] Por primera vez en la historia turca, se construyeron líneas ferroviarias de alta velocidad , y el servicio de trenes de alta velocidad del país comenzó en 2009. [130] En 8 años, se construyeron 1.076 km de vías férreas y se renovaron 5.449 km de vías férreas. La construcción de Marmaray , un túnel ferroviario submarino bajo el estrecho del Bósforo , comenzó en 2004. Se inauguró en el 90 aniversario de la República Turca el 29 de octubre de 2013. [131] La inauguración del Puente Yavuz Sultan Selim , el tercer puente sobre el Bósforo , fue el 26 de agosto de 2016. [132]

En marzo de 2006, la Junta Suprema de Jueces y Fiscales (HSYK) celebró una conferencia de prensa para protestar públicamente por la obstrucción del nombramiento de jueces para los tribunales superiores durante más de 10 meses. La HSYK dijo que Erdoğan quería llenar los puestos vacantes con sus propios designados. Erdoğan fue acusado de crear una ruptura con el tribunal de apelación más alto de Turquía, el Yargıtay , y el tribunal administrativo superior, el Danıştay . Erdoğan declaró que la constitución otorgaba el poder de asignar estos puestos a su partido electo. [133]

En mayo de 2007, el presidente del Tribunal Supremo de Turquía pidió a los fiscales que consideraran si Erdoğan debía ser acusado por comentarios críticos con respecto a la elección de Abdullah Gül como presidente. [133] Erdoğan dijo que el fallo era "una vergüenza para el sistema de justicia" y criticó al Tribunal Constitucional que había invalidado una votación presidencial porque un boicot de otros partidos significaba que no había quórum . Los fiscales investigaron sus comentarios anteriores, incluyendo decir que había disparado una "bala a la democracia". Tülay Tuğcu , presidente del Tribunal Constitucional, condenó a Erdoğan por "amenazas, insultos y hostilidad" hacia el sistema de justicia. [134]

.jpg/440px-Visita_del_Presidente_de_Turquía_a_la_Cancillería_del_Perú_(24663516722).jpg)

El ejército turco tiene un historial de intervención en la política, habiendo derrocado a gobiernos electos cuatro veces en el pasado . Durante el gobierno de Erdoğan, la relación civil-militar avanzó hacia la normalización, en la que la influencia de los militares en la política se redujo significativamente. [135] El gobernante Partido de la Justicia y el Desarrollo se ha enfrentado a menudo a los militares, ganando poder político al desafiar a un pilar del establishment laicista del país.

El problema más importante que causó profundas fisuras entre el ejército y el gobierno fue el memorando electrónico de medianoche publicado en el sitio web del ejército objetando la selección del Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores Abdullah Gül como candidato del partido gobernante para la Presidencia en 2007. El ejército argumentó que la elección de Gül, cuya esposa usa un pañuelo islámico , podría socavar el orden laicista del país. Contrariamente a las expectativas, el gobierno respondió con dureza al memorando electrónico del ex Jefe del Estado Mayor General, General Yaşar Büyükanıt , declarando que los militares no tenían nada que ver con la selección del candidato presidencial. [136]

Tras asumir el poder en 2003, el gobierno de Erdoğan se embarcó en un amplio programa de reforma del sistema sanitario turco, denominado Programa de Transformación de la Salud (PTS), para aumentar considerablemente la calidad de la atención sanitaria y proteger a todos los ciudadanos de los riesgos financieros. Su introducción coincidió con el período de crecimiento económico sostenido, lo que permitió al gobierno turco realizar mayores inversiones en el sistema sanitario. Como parte de las reformas, en 2004 se amplió el programa de la "Tarjeta Verde", que proporciona prestaciones sanitarias a los pobres. [137] El programa de reforma tenía por objeto aumentar la proporción de atención sanitaria privada frente a la estatal, lo que, junto con las largas colas en los hospitales estatales, dio lugar al aumento de la atención médica privada en Turquía, lo que obligó a los hospitales estatales a competir aumentando la calidad.

En abril de 2006, Erdoğan dio a conocer un paquete de reformas de la seguridad social exigido por el Fondo Monetario Internacional en el marco de un acuerdo de préstamo. La medida, que Erdoğan calificó como una de las reformas más radicales de la historia, fue aprobada con una feroz oposición. Los tres organismos de seguridad social de Turquía se unificaron bajo un mismo techo, lo que permitió ofrecer servicios de salud y beneficios de jubilación iguales a los miembros de los tres organismos. El sistema anterior había sido criticado por reservar la mejor atención médica para los funcionarios públicos y relegar a los demás a esperar en largas colas. En virtud del segundo proyecto de ley, todos los menores de 18 años tenían derecho a servicios de salud gratuitos, independientemente de si pagaban primas a alguna organización de seguridad social. El proyecto de ley también prevé un aumento gradual de la edad de jubilación: a partir de 2036, la edad de jubilación aumentará hasta los 65 años en 2048 tanto para las mujeres como para los hombres. [138]

En enero de 2008, el Parlamento turco aprobó una ley que prohíbe fumar en la mayoría de los lugares públicos. Erdoğan se muestra abiertamente contrario al tabaquismo. [139]

La política exterior turca durante el mandato de Erdoğan como primer ministro ha estado asociada al nombre de Ahmet Davutoğlu . Davutoğlu fue el principal asesor de política exterior del primer ministro Recep Tayyip Erdoğan antes de que fuera nombrado ministro de Asuntos Exteriores en 2009. La base de la política exterior de Erdoğan se basa en el principio de "no hacer enemigos, hacer amigos" [140] y la búsqueda de "cero problemas" con los países vecinos. [141]

Erdoğan es cofundador de la Alianza de Civilizaciones de las Naciones Unidas (AOC). La iniciativa busca impulsar la acción internacional contra el extremismo mediante el establecimiento de un diálogo y una cooperación internacionales, interculturales e interreligiosos.

Cuando Erdoğan llegó al poder, continuó con la larga ambición de Turquía de unirse a la Unión Europea . Turquía, bajo Erdoğan, hizo muchos avances en sus leyes que calificarían para la membresía de la UE. [142] El 3 de octubre de 2005 comenzaron las negociaciones para la adhesión de Turquía a la Unión Europea . [143] [144] Erdoğan fue nombrado "El europeo del año 2004" por el periódico European Voice por las reformas en su país para lograr la adhesión de Turquía a la Unión Europea. Dijo en un comentario que "la adhesión de Turquía muestra que Europa es un continente donde las civilizaciones se reconcilian y no chocan". [145] El 3 de octubre de 2005, las negociaciones para la adhesión de Turquía a la UE comenzaron formalmente durante el mandato de Erdoğan como Primer Ministro. [143]

La Comisión Europea, en general, apoya las reformas de Erdoğan, pero sigue siendo crítica con sus políticas. Las negociaciones sobre una posible adhesión a la UE se estancaron en 2009 y 2010, cuando los puertos turcos fueron cerrados a los barcos chipriotas. El gobierno turco sigue negándose a reconocer a Chipre como Estado miembro de la UE .

Las relaciones entre Grecia y Turquía se normalizaron durante el mandato de Erdoğan como primer ministro. En mayo de 2004, Erdoğan se convirtió en el primer primer ministro turco en visitar Grecia desde 1988, y el primero en visitar la minoría turca de Tracia desde 1952. En 2007, Erdoğan y el primer ministro griego Kostas Karamanlis inauguraron el gasoducto greco-turco de gas natural, que proporciona al gas del Caspio su primera salida directa a Occidente. [146] Turquía y Grecia firmaron un acuerdo para crear una Unidad Operativa Conjunta Combinada en el marco de la OTAN para participar en las Operaciones de Apoyo a la Paz. [147] Erdoğan y su partido apoyaron firmemente el referéndum respaldado por la UE para reunificar Chipre en 2004. [148] Las negociaciones sobre una posible membresía en la UE se paralizaron en 2009 y 2010, cuando los puertos turcos se cerraron a los barcos chipriotas como consecuencia del aislamiento económico de la República Turca del Norte de Chipre no reconocida internacionalmente y el fracaso de la UE para poner fin al aislamiento, como había prometido en 2004. [149] El gobierno turco continúa con su negativa a reconocer a la República de Chipre. [150]

Armenia es el único vecino de Turquía que Erdoğan no ha visitado durante su mandato como primer ministro. La frontera turco-armenia está cerrada desde 1993 debido al conflicto de Nagorno-Karabaj con Azerbaiyán , un aliado cercano de Turquía .

Los esfuerzos diplomáticos dieron como resultado la firma de protocolos entre los ministros de Asuntos Exteriores de Turquía y Armenia en Suiza para mejorar las relaciones entre los dos países. Uno de los puntos del acuerdo fue la creación de una comisión conjunta sobre el tema. El Tribunal Constitucional de Armenia decidió que la comisión contradice la constitución armenia . Turquía respondió diciendo que la decisión del tribunal armenio sobre los protocolos no es aceptable, lo que dio como resultado la suspensión del proceso de rectificación por parte turca. [151]

Erdoğan ha dicho que el presidente armenio Serge Sarkisian debería disculparse por haber pedido a los niños de las escuelas que reocuparan el este de Turquía. Cuando un estudiante le preguntó en una ceremonia de concurso literario si los armenios podrán recuperar sus "territorios occidentales" junto con el monte Ararat, Sarkisian dijo: "Esta es la tarea de vuestra generación". [152]

En diciembre de 2004, el presidente Putin visitó Turquía, lo que la convirtió en la primera visita presidencial en la historia de las relaciones turco-rusas, además de la del presidente del Soviet Supremo de la URSS , Nikolai Podgorny , en 1972. En noviembre de 2005, Putin asistió a la inauguración de un gasoducto de gas natural Blue Stream construido conjuntamente en Turquía. Esta secuencia de visitas de alto nivel ha puesto en primer plano varias cuestiones bilaterales importantes. Los dos países consideran que su objetivo estratégico es lograr una "cooperación multidimensional", especialmente en los campos de la energía, el transporte y el ejército. En concreto, Rusia pretende invertir en las industrias de combustible y energía de Turquía, y también espera participar en licitaciones para la modernización del ejército de Turquía. [153] Las relaciones durante este tiempo son descritas por el presidente Medvedev como "Turquía es uno de nuestros socios más importantes con respecto a cuestiones regionales e internacionales. Podemos decir con confianza que las relaciones ruso-turcas han avanzado al nivel de una asociación estratégica multidimensional". [154]

En mayo de 2010, Turquía y Rusia firmaron 17 acuerdos para mejorar la cooperación en materia de energía y otros campos, incluidos pactos para construir la primera planta de energía nuclear de Turquía y otros planes para un oleoducto desde el Mar Negro hasta el Mar Mediterráneo . Los líderes de ambos países también firmaron un acuerdo sobre viajes sin visado, que permite a los turistas entrar en el otro país de forma gratuita y permanecer allí hasta 30 días. [ cita requerida ]

Cuando Barack Obama asumió la presidencia de Estados Unidos , realizó su primera reunión bilateral en el exterior en Turquía en abril de 2009.

En una conferencia de prensa conjunta en Turquía, Obama dijo: "Estoy tratando de hacer una declaración sobre la importancia de Turquía, no sólo para Estados Unidos sino para el mundo. Creo que donde hay más posibilidades de construir relaciones más sólidas entre Estados Unidos y Turquía es en el reconocimiento de que Turquía y Estados Unidos pueden construir una asociación modelo en la que una nación predominantemente cristiana , una nación predominantemente musulmana –una nación occidental y una nación que se extiende a lo largo de dos continentes– podamos crear una comunidad internacional moderna que sea respetuosa, segura, próspera, en la que no haya tensiones –las inevitables tensiones entre culturas–, lo cual creo que es extraordinariamente importante". [155]

La administración Bush nombró a Turquía bajo el gobierno de Erdoğan como parte de la " coalición de los dispuestos " que fue central en la invasión de Irak en 2003. [ 156] El 1 de marzo de 2003, el Parlamento turco rechazó una moción que permitía a los militares turcos participar en la invasión de Irak de la coalición liderada por Estados Unidos, junto con el permiso para que tropas extranjeras se estacionaran en Turquía para este propósito. [157]

Tras la caída de Saddam Hussein , Irak y Turquía firmaron 48 acuerdos comerciales sobre cuestiones como la seguridad, la energía y el agua. El gobierno turco intentó mejorar las relaciones con el Kurdistán iraquí abriendo una universidad turca en Erbil y un consulado turco en Mosul . [158] El gobierno de Erdoğan fomentó las relaciones económicas y políticas con Irbil , y Turquía comenzó a considerar al Gobierno Regional del Kurdistán en el norte de Irak como un aliado contra el gobierno de Maliki. [159]

Erdoğan visitó Israel el 1 de mayo de 2005, un gesto inusual para un líder de un país de mayoría musulmana. [160] Durante su viaje, Erdoğan visitó Yad Vashem , el monumento oficial de Israel a las víctimas del Holocausto . [160] El presidente de Israel, Shimon Peres, se dirigió al parlamento turco durante una visita en 2007, la primera vez que un líder israelí se dirigía a la legislatura de una nación predominantemente musulmana. [161]

Su relación empeoró en la conferencia del Foro Económico Mundial de 2009 por las acciones de Israel durante la Guerra de Gaza . [162] Erdoğan fue interrumpido por el moderador mientras respondía a Peres. Erdoğan declaró: "Señor Peres, usted es mayor que yo. Tal vez se sienta culpable y por eso está levantando la voz. Cuando se trata de matar, usted lo sabe muy bien. Recuerdo cómo mataba a los niños en las playas...". Cuando el moderador le recordó que debían levantar la sesión para cenar, Erdoğan abandonó el panel, acusando al moderador de darle a Peres más tiempo que a todos los demás panelistas juntos. [163]

Las tensiones aumentaron aún más tras el ataque a la flotilla de Gaza en mayo de 2010. Erdoğan condenó enérgicamente el ataque, describiéndolo como "terrorismo de Estado", y exigió una disculpa israelí. [164] En febrero de 2013, Erdoğan calificó al sionismo como un "crimen contra la humanidad", comparándolo con la islamofobia, el antisemitismo y el fascismo. [165] Más tarde se retractó de la declaración, diciendo que había sido malinterpretado. Dijo que "todo el mundo debería saber" que sus comentarios estaban dirigidos a las "políticas israelíes", especialmente en lo que respecta a "Gaza y los asentamientos". [166] [167] Las declaraciones de Erdoğan fueron criticadas por el Secretario General de la ONU, Ban Ki-moon , entre otros. [168] [169] En agosto de 2013, el Hürriyet informó que Erdoğan había afirmado tener pruebas de la responsabilidad de Israel en la destitución de Morsi del cargo en Egipto . [170] Los gobiernos israelí y egipcio rechazaron la sugerencia. [171]

En respuesta al conflicto de 2014 entre Israel y Gaza , Erdoğan acusó a Israel de llevar a cabo « terrorismo de Estado » y un «intento de genocidio» contra los palestinos . [172] También afirmó que «si Israel continúa con esta actitud, definitivamente será juzgado en tribunales internacionales». [173]

Durante el mandato de Erdoğan, las relaciones diplomáticas entre Turquía y Siria se deterioraron significativamente. En 2004, el presidente Bashar al-Assad llegó a Turquía para la primera visita oficial de un presidente sirio en 57 años. A finales de 2004, Erdoğan firmó un acuerdo de libre comercio con Siria. Las restricciones de visado entre los dos países se levantaron en 2009, lo que provocó un auge económico en las regiones cercanas a la frontera siria. [174] Sin embargo, en 2011 la relación entre los dos países se tensó tras el estallido del conflicto en Siria . Recep Tayyip Erdoğan dijo que estaba tratando de "cultivar una relación favorable con cualquier gobierno que tomara el lugar de Assad". [175] Sin embargo, comenzó a apoyar a la oposición en Siria, después de que las manifestaciones se volvieran violentas, creando un grave problema de refugiados sirios en Turquía. [176] La política de Erdoğan de proporcionar entrenamiento militar a los combatientes anti-Damasco también ha creado un conflicto con el aliado de Siria y vecino de Turquía, Irán. [177]

En agosto de 2006, el rey Abdullah bin Abdulaziz as-Saud visitó Turquía. Se trataba de la primera visita de un monarca saudí a Turquía en las últimas cuatro décadas. El monarca realizó una segunda visita el 9 de noviembre de 2007. El volumen del comercio turco-saudí superó los 3.200 millones de dólares en 2006, casi el doble de la cifra alcanzada en 2003. En 2009, esta cantidad alcanzó los 5.500 millones de dólares y el objetivo para el año 2010 era de 10.000 millones de dólares . [178]

Erdoğan condenó la intervención liderada por Arabia Saudita en Bahréin y calificó al movimiento saudí como "un nuevo Karbala ". Exigió la retirada de las fuerzas saudíes de Bahréin . [179]

Erdoğan había realizado su primera visita oficial a Egipto el 12 de septiembre de 2011, acompañado por seis ministros y 200 empresarios. [180] Esta visita se realizó muy poco después de que Turquía expulsara a los embajadores israelíes, cortando todas las relaciones diplomáticas con Israel porque este se negó a disculparse por el ataque a la flotilla de Gaza en el que murieron ocho turcos y un turco-estadounidense. [180]

La visita de Erdoğan a Egipto fue recibida con mucho entusiasmo por los egipcios . La CNN informó que algunos egipcios dijeron: "Lo consideramos el líder islámico en Oriente Medio", mientras que otros apreciaron su papel en el apoyo a Gaza. [180] Erdoğan fue homenajeado más tarde en la plaza Tahrir por miembros de la Unión de Jóvenes de la Revolución Egipcia, y los miembros de la embajada turca recibieron un escudo de armas en reconocimiento al apoyo del Primer Ministro a la Revolución Egipcia. [181]

Erdoğan declaró en una entrevista de 2011 que apoyaba el secularismo en Egipto, lo que generó una reacción furiosa entre los movimientos islámicos, especialmente el Partido Libertad y Justicia , que era el ala política de la Hermandad Musulmana . [181] Sin embargo, los comentaristas sugieren que al formar una alianza con la junta militar durante la transición de Egipto a la democracia, Erdoğan puede haber inclinado la balanza a favor de un gobierno autoritario. [181]

Erdoğan condenó las concentraciones llevadas a cabo por la policía egipcia el 14 de agosto de 2013 en las plazas de Rabaa al-Adawiya y al-Nahda, donde violentos enfrentamientos entre agentes de policía y manifestantes islamistas partidarios de Morsi provocaron cientos de muertes, en su mayoría manifestantes. [182] En julio de 2014, un año después de la destitución de Mohamed Morsi , Erdoğan calificó al presidente egipcio Abdel Fattah el-Sisi de "tirano ilegítimo". [183]

.jpg/440px-2015_01_25_Turkish_President_Visit_to_Somalia-1_(16176887607).jpg)

El gobierno de Erdoğan mantiene fuertes vínculos con el gobierno somalí. Durante la sequía de 2011 , el gobierno de Erdoğan contribuyó con más de 201 millones de dólares a las labores de socorro humanitario en las zonas afectadas de Somalia. [184] Tras una mejora considerable de la situación de seguridad en Mogadiscio a mediados de 2011, el gobierno turco también reabrió su embajada en el extranjero con la intención de ayudar de forma más eficaz en el proceso de desarrollo posterior al conflicto. [185] Fue uno de los primeros gobiernos extranjeros en reanudar las relaciones diplomáticas formales con Somalia después de la guerra civil. [186]

En mayo de 2010, los gobiernos turco y somalí firmaron un acuerdo de entrenamiento militar, de conformidad con las disposiciones delineadas en el Proceso de Paz de Yibuti. [187] Turkish Airlines se convirtió en la primera aerolínea comercial internacional de larga distancia en dos décadas en reanudar los vuelos hacia y desde el Aeropuerto Internacional Adén Adde de Mogadiscio . [186] Turquía también lanzó varios proyectos de desarrollo e infraestructura en Somalia, incluyendo la construcción de varios hospitales y la ayuda para renovar el edificio de la Asamblea Nacional. [186]

Las protestas del parque Gezi de 2013 se llevaron a cabo contra el autoritarismo percibido de Erdoğan y sus políticas, comenzando con una pequeña sentada en Estambul en defensa de un parque de la ciudad . [188] Después de la intensa reacción de la policía con gases lacrimógenos , las protestas crecieron cada día. Ante la protesta masiva más grande en una década, Erdoğan hizo esta controvertida observación en un discurso televisado: "La policía estuvo allí ayer, está allí hoy y estará allí mañana". Después de semanas de enfrentamientos en las calles de Estambul , su gobierno en un primer momento se disculpó con los manifestantes [189] y convocó a un plebiscito , pero luego ordenó una ofensiva contra los manifestantes. [188] [190]

Erdoğan prestó juramento el 28 de agosto de 2014 y se convirtió en el duodécimo presidente de Turquía . [191] El 29 de agosto prestó juramento al nuevo primer ministro Ahmet Davutoğlu . Cuando se le preguntó sobre su porcentaje de votos menor al esperado del 51,79 %, supuestamente respondió: "Incluso hubo quienes no simpatizaron con el Profeta . Yo, sin embargo, gané el 52 %". [192] Al asumir el papel de presidente, Erdoğan fue criticado por afirmar abiertamente que no mantendría la tradición de neutralidad presidencial. [193] Erdoğan también ha declarado su intención de desempeñar un papel más activo como presidente, como utilizar los poderes de convocatoria del gabinete que rara vez utiliza el presidente. [194] La oposición política ha argumentado que Erdoğan seguirá persiguiendo su propia agenda política, controlando el gobierno, mientras que su nuevo primer ministro Ahmet Davutoğlu sería dócil y sumiso. [195] Además, el predominio de los partidarios leales de Erdoğan en el gabinete de Davutoğlu alimentó la especulación de que Erdoğan tenía la intención de ejercer un control sustancial sobre el gobierno. [196]

El 1 de julio de 2014, Erdoğan fue nombrado candidato presidencial del AKP en las elecciones presidenciales turcas . Su candidatura fue anunciada por el vicepresidente del AKP, Mehmet Ali Şahin .

Erdoğan pronunció un discurso después del anuncio y utilizó por primera vez el «logotipo de Erdoğan». El logotipo fue criticado porque era muy similar al que utilizó el presidente estadounidense Barack Obama en las elecciones presidenciales de 2008. [ 197]

Erdoğan fue elegido presidente de Turquía en la primera vuelta de las elecciones con el 51,79% de los votos, lo que hizo innecesaria la segunda vuelta al obtener más del 50%. El candidato conjunto del CHP , el MHP y otros 13 partidos de la oposición, el ex secretario general de la Organización para la Cooperación Islámica Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, ganó el 38,44% de los votos. El candidato pro-kurdo del HDP Selahattin Demirtaş ganó el 9,76%. [198]

Las elecciones presidenciales turcas de 2018 se celebraron como parte de las elecciones generales de 2018 , junto con las elecciones parlamentarias el mismo día. Tras la aprobación de los cambios constitucionales en un referéndum celebrado en 2017, el presidente electo será tanto jefe de Estado como jefe de Gobierno de Turquía, asumiendo este último papel de la oficina del primer ministro, que se abolirá . [199]

El presidente en ejercicio, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, declaró su candidatura por la Alianza Popular (en turco: Cumhur İttifakı ) el 27 de abril de 2018, [ cita requerida ] con el apoyo del MHP. [200] La principal oposición de Erdoğan, el Partido Republicano del Pueblo , nominó a Muharrem İnce , un miembro del parlamento conocido por su oposición combativa y sus discursos enérgicos contra Erdoğan. [201] Además de estos candidatos, Meral Akşener , fundador y líder del Partido del Bien , [202] Temel Karamollaoğlu , líder del Partido de la Felicidad y Doğu Perinçek , líder del Partido Patriótico , han anunciado sus candidaturas y han recogido las 100.000 firmas necesarias para la nominación. La alianza por la que Erdoğan era candidato obtuvo el 52,59% del voto popular.

Para las elecciones presidenciales de 2023 su candidatura está en disputa ya que lanzó su campaña en junio de 2022, [203] pero la oposición sostiene que un tercer mandato presidencial violaría la constitución . [204] Durante la primera ronda de votaciones en las elecciones presidenciales de 2023, Erdoğan no logró cruzar el umbral del 50%, lo que resultó en una segunda vuelta electoral contra Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu . [205] El 28 de mayo de 2023 Erdoğan ganó la segunda vuelta con el 52,14% de los votos, con más del 99% del total de votos escrutados. [206]

El 8 de marzo de 2024 declaró que se retiraría una vez que terminara su mandato presidencial en 2028. [207]

En abril de 2017, se celebró un referéndum constitucional , en el que los votantes de Turquía (y los ciudadanos turcos en el extranjero) aprobaron un conjunto de 18 enmiendas propuestas a la Constitución de Turquía. [208] Las enmiendas incluían la sustitución del sistema parlamentario existente por un sistema presidencial . El cargo de Primer Ministro sería abolido y la presidencia se convertiría en un cargo ejecutivo dotado de amplios poderes ejecutivos. Los escaños del parlamento se incrementarían de 550 a 600 y la edad de candidatura al parlamento se reduciría de 25 a 18 años. El referéndum también pidió cambios en la Junta Suprema de Jueces y Fiscales . [209]

En las elecciones locales de 2019 , el partido gobernante AKP perdió el control de Estambul y Ankara por primera vez en 25 años, así como de 5 de las 6 ciudades más grandes de Turquía. La pérdida se ha atribuido ampliamente a la mala gestión de Erdoğan de la crisis económica turca, el creciente autoritarismo y la supuesta inacción del gobierno en la crisis de refugiados sirios . [210] Poco después de las elecciones, el Consejo Electoral Supremo de Turquía ordenó una reelección en Estambul , cancelando el certificado de alcalde de Ekrem İmamoğlu . La decisión provocó una disminución significativa de la popularidad de Erdoğan y del AKP y su partido volvió a perder las elecciones en junio con un margen mayor. [211] [212] [213] [214] El resultado fue visto como un gran golpe para Erdoğan, quien una vez había dicho que si su partido "perdía Estambul, perderíamos Turquía". La victoria de la oposición fue caracterizada como "el principio del fin" para Erdoğan, [215] [216] [217] y los comentaristas internacionales calificaron la repetición como un enorme error de cálculo del gobierno que llevó a una posible candidatura de İmamoğlu en las próximas elecciones presidenciales programadas . [215] [217] Se sospecha que la magnitud de la derrota del gobierno podría provocar una reorganización del gabinete y elecciones generales anticipadas, actualmente programadas para junio de 2023. [218] [219]

Los gobiernos de Nueva Zelanda y Australia y el partido de oposición CHP han criticado a Erdoğan después de que éste mostrara repetidamente a sus partidarios en los mítines de campaña para las elecciones locales del 31 de marzo un vídeo tomado por el tirador de la mezquita de Christchurch y dijo que los australianos y neozelandeses que llegaron a Turquía con sentimientos antimusulmanes "serían enviados de vuelta en ataúdes como sus abuelos" en Galípoli . [220] [221]

Erdoğan también ha recibido críticas por la construcción de una nueva residencia oficial llamada Complejo Presidencial , que ocupa aproximadamente 50 acres de la Granja Forestal Atatürk (AOÇ) en Ankara . [222] [223] Dado que la AOÇ es un terreno protegido, se emitieron varias órdenes judiciales para detener la construcción del nuevo palacio, aunque las obras continuaron de todos modos. [224] La oposición describió la medida como un claro desprecio por el estado de derecho. [225] El proyecto fue objeto de fuertes críticas y se hicieron acusaciones de corrupción durante el proceso de construcción, destrucción de la vida silvestre y la completa destrucción del zoológico en la AOÇ para dar paso al nuevo complejo. [226] El hecho de que el palacio sea técnicamente ilegal ha llevado a que se lo etiquete como 'Kaç-Ak Saray', la palabra kaçak en turco significa 'ilegal'. [227]

Ak Saray fue diseñado originalmente como una nueva oficina para el Primer Ministro. Sin embargo, al asumir la presidencia, Erdoğan anunció que el palacio se convertiría en el nuevo Palacio Presidencial, mientras que la Mansión Çankaya sería utilizada por el Primer Ministro. La medida fue vista como un cambio histórico ya que la Mansión Çankaya había sido utilizada como la oficina icónica de la presidencia desde su inicio. El Complejo Presidencial tiene casi 1.000 habitaciones y costó $350 millones (€270 millones), lo que provocó enormes críticas en un momento en que los accidentes mineros y los derechos de los trabajadores habían dominado la agenda. [228] [229]

El 29 de octubre de 2014, Erdoğan tenía previsto celebrar una recepción por el Día de la República en el nuevo palacio para conmemorar el 91º aniversario de la República de Turquía e inaugurar oficialmente el Palacio Presidencial . Sin embargo, después de que la mayoría de los participantes invitados anunciaran que boicotearían el evento y se produjera un accidente minero en el distrito de Ermenek en Karaman , la recepción se canceló. [230]

El presidente Erdoğan y su gobierno siguen presionando para que se emprendan acciones judiciales contra la prensa libre que aún existe en Turquía. El último periódico que ha sido incautado es Zaman , en marzo de 2016. [231] Después de la incautación, Morton Abramowitz y Eric Edelman , ex embajadores estadounidenses en Turquía, condenaron las acciones del presidente Erdoğan en un artículo de opinión publicado por The Washington Post : "Claramente, la democracia no puede florecer ahora bajo Erdoğan". [232] "El ritmo general de las reformas en Turquía no solo se ha ralentizado, sino que en algunas áreas clave, como la libertad de expresión y la independencia del poder judicial, ha habido una regresión, lo que es particularmente preocupante", dijo la relatora Kati Piri en abril de 2016 después de que el Parlamento Europeo aprobara su informe anual de progreso sobre Turquía. [233]

El 22 de junio de 2016, el presidente Recep Tayyip Erdoğan dijo que se consideraba exitoso en "destruir" a los grupos civiles turcos "que trabajan contra el Estado", [234] una conclusión que había sido confirmada unos días antes por Sedat Laçiner , profesor de Relaciones Internacionales y rector de la Universidad Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart : "Proscribir la oposición desarmada y pacífica, condenar a las personas a castigos injustos bajo acusaciones erróneas de terrorismo, alimentará el terrorismo genuino en la Turquía de Erdoğan. Las armas y la violencia se convertirán en la única alternativa para expresar legalmente el pensamiento libre". [235]

Tras el intento de golpe de Estado, más de 200 periodistas fueron detenidos y más de 120 medios de comunicación fueron clausurados. Los periodistas de Cumhuriyet fueron detenidos en noviembre de 2016 tras una prolongada campaña de represión contra el periódico. Posteriormente, Reporteros sin Fronteras calificó a Erdoğan de "enemigo de la libertad de prensa" y afirmó que "oculta su dictadura agresiva bajo una apariencia de democracia". [236]

En 2014, Turquía bloqueó temporalmente el acceso a Twitter . [237] En abril de 2017, Turquía bloqueó todo acceso a Wikipedia debido a una disputa de contenido. [238] El gobierno turco levantó una prohibición de dos años y medio sobre Wikipedia el 15 de enero de 2020, restaurando el acceso a la enciclopedia en línea un mes después de que el tribunal superior de Turquía dictaminara que bloquear Wikipedia era inconstitucional.

El 1 de julio de 2020, en una declaración dirigida a los miembros de su partido, Erdoğan anunció que el gobierno introduciría nuevas medidas y regulaciones para controlar o cerrar plataformas de redes sociales como YouTube , Twitter y Netflix . A través de estas nuevas medidas, cada empresa estaría obligada a designar un representante oficial en el país para responder a las inquietudes legales. La decisión se tomó después de que varios usuarios de Twitter insultaran a su hija Esra después de que diera a luz a su cuarto hijo. [239]

El 20 de julio de 2016, el presidente Erdoğan declaró el estado de emergencia , citando el intento de golpe de estado como justificación. [240] En un principio, se había previsto que durara tres meses. El parlamento turco aprobó esta medida. [241] El estado de emergencia se extendió posteriormente de forma continua hasta 2018 [242] [243] en medio de las purgas turcas en curso en 2016, incluidas purgas exhaustivas de medios independientes y la detención de decenas de miles de ciudadanos turcos políticamente opuestos a Erdoğan. [244] Más de 50.000 personas han sido detenidas y más de 160.000 despedidas de sus trabajos hasta marzo de 2018. [245] [242]

En agosto de 2016, Erdoğan comenzó a arrestar a periodistas que habían publicado o estaban a punto de publicar artículos que cuestionaban la corrupción dentro de la administración de Erdoğan, y a encarcelarlos. [246] El número de periodistas turcos encarcelados por Turquía es mayor que el de cualquier otro país, incluidos todos los periodistas actualmente encarcelados en Corea del Norte, Cuba, Rusia y China juntos. [247] A raíz del intento de golpe de Estado de julio de 2016, la administración de Erdoğan comenzó a arrestar a decenas de miles de personas, tanto dentro del gobierno como del sector público, y a encarcelarlas bajo cargos de presunto "terrorismo". [248] [249] [250] Como resultado de estos arrestos, muchos en la comunidad internacional se quejaron de la falta de un proceso judicial adecuado en el encarcelamiento de la oposición de Erdoğan. [251]

In April 2017 Erdoğan successfully sponsored legislation effectively making it illegal for the Turkish legislative branch to investigate his executive branch of government.[252] Without the checks and balances of freedom of speech, and the freedom of the Turkish legislature to hold him accountable for his actions, many have likened Turkey's current form of government to a dictatorship with only nominal forms of democracy in practice.[253][254] At the time of Erdoğan's successful passing of the most recent legislation silencing his opposition, United States President Donald Trump called Erdoğan to congratulate him for his "recent referendum victory".[255]

On 29 April 2017 Erdoğan's administration began an internal Internet block of all of the Wikipedia online encyclopedia site via Turkey's domestic Internet filtering system. This blocking action took place after the government had first made a request for Wikipedia to remove what it referred to as "offensive content". In response, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales replied via a post on Twitter stating, "Access to information is a fundamental human right. Turkish people, I will always stand with you and fight for this right."[256][257]

In January 2016, more than a thousand academics signed a petition criticizing Turkey's military crackdown on ethnic Kurdish towns and neighborhoods in the east of the country, such as Sur (a district of Diyarbakır), Silvan, Nusaybin, Cizre and Silopi, and asking an end to violence.[258] Erdoğan accused those who signed the petition of "terrorist propaganda", calling them "the darkest of people". He called for action by institutions and universities, stating, "Everyone who benefits from this state but is now an enemy of the state must be punished without further delay".[259] Within days, over 30 of the signatories were arrested, many in dawn-time raids on their homes. Although all were quickly released, nearly half were fired from their jobs, eliciting a denunciation from Turkey's Science Academy for such "wrong and disturbing" treatment.[260] Erdoğan vowed that the academics would pay the price for "falling into a pit of treachery".[261]

On 8 July 2018, Erdoğan sacked 18,000 officials for alleged ties to US based cleric Fethullah Gülen, shortly before renewing his term as an executive president. Of those removed, 9000 were police officers with 5000 from the armed forces with the addition of hundreds of academics.[262]

Under his presidency, Erdoğan has decreased the independence of the Central Bank and pushed it to pursue a highly unorthodox monetary policy, decreasing interest rates even with high inflation.[263] He has pushed the theory that inflation is caused by high interest rates, an idea universally rejected by economists.[263][264] This, along with other factors such as excessive current account deficit and foreign-currency debt,[265] in combination with Erdoğan's increasing authoritarianism, caused an economic crisis starting from 2018, leading to large depreciation of the Turkish lira and very high inflation.[266][267][268][269] Economist Paul Krugman described the unfolding crisis as "a classic currency-and-debt crisis, of a kind we've seen many times", adding: "At such a time, the quality of leadership suddenly matters a great deal. You need officials who understand what's happening, can devise a response and have enough credibility that markets give them the benefit of the doubt. Some emerging markets have those things, and they are riding out the turmoil fairly well. The Erdoğan regime has none of that".[270]

In February 2016, Erdoğan threatened to send the millions of refugees in Turkey to EU member states,[271] saying: "We can open the doors to Greece and Bulgaria anytime and we can put the refugees on buses ... So how will you deal with refugees if you don't get a deal?"[272]

In an interview to the news magazine Der Spiegel, German minister of defence Ursula von der Leyen said on 11 March 2016 that the refugee crisis had made good cooperation between EU and Turkey an "existentially important" issue. "Therefore it is right to advance now negotiations on Turkey's EU accession".[273]

In its resolution "The functioning of democratic institutions in Turkey" from 22 June 2016, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe warned that "recent developments in Turkey pertaining to freedom of the media and of expression, erosion of the rule of law and the human rights violations in relation to anti-terrorism security operations in south-east Turkey have ... raised serious questions about the functioning of its democratic institutions".[274][275]

In January 2017, Erdoğan said that the withdrawal of Turkish troops from Northern Cyprus is "out of the question" and Turkey will be in Cyprus "forever".[276]

In September 2020, Erdoğan declared his government's support for Azerbaijan following a major conflict between Armenian and Azeri forces over a disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh.[277] He dismissed demands for a ceasefire.[278] In 2022, Erdoğan and Russian President Vladimir Putin planned for Turkey to become an energy hub for all of Europe through the TurkStream and Blue Stream gas pipelines.[279][280] In October 2023 Erdoğan canceled attendance at the third European Political Community (EPC) meeting.[281][282]

_(1).jpg/440px-Putin_meets_Erdogan_(2024-06-03)_(1).jpg)

In May 2022, Erdoğan voiced his opposition to Finland and Sweden joining NATO, accusing the two countries of tolerating groups which Turkey classifies as terrorist organizations,[283] including the Kurdish militant groups PKK, PYD and YPG and the supporters of Fethullah Gülen.[284] Following a protest in Sweden where a Quran was burned, Erdogan re-iterated that he would not support Sweden's bid to join NATO.[285] President of Finland Sauli Niinistö visited Erdogan in Istanbul and Ankara in March 2023. During the visit, Erdogan confirmed that he supported Finnish NATO membership and declared that the Turkish parliament would confirm Finnish membership before the Turkish Presidential elections in May 2023.[286] On 23 March 2023, the Turkish parliament's foreign relations committee confirmed the Finnish NATO membership application and sent the process to the Turkish Parliament's plenary session.[287] On 1 April 2023, Erdoğan confirmed and signed the Turkish Grand National Assembly's ratification of Finnish NATO membership.[288] This decision sealed Finland's entry to NATO. In June 2023, Erdoğan again voiced his opposition to Sweden joining NATO.[289] Just prior to the NATO summit in Vilnius in July 2023, Erdoğan linked Sweden's accession to NATO membership to Turkey's application for EU membership. Turkey had applied for EU membership in 1999, but talks made little progress since 2016.[290][291] In September 2023, Erdoğan announced that the European Union was well into a rupture in its relations with Turkey and that they would part ways during Turkey's European Union membership process.[292] However, on 23 October 2023, Erdoğan approved Sweden's pending NATO membership bid and sent the accession protocol to the Turkish Parliament for ratification.[293] Two days later, Turkey's parliamentary speaker, Numan Kurtulmuş, sent a bill approving Sweden's NATO membership bid to parliament's foreign affairs committee.[294] The committee discussed the ratification on 16 November 2023, but a decision was deferred,[295] with a request for Sweden to produce a written roadmap to implement its anti-terrorism commitments.[296][297] On 26 December 2023, the Turkish parliament's foreign relations committee confirmed the Swedish NATO membership application and sent the process to the Turkish Parliament's plenary session.[298] On 25 January 2024, Erdoğan formally signed and approved the Turkish parliament's decision to ratify Swedish NATO membership.[299]

There is a long-standing dispute between Turkey and Greece in the Aegean Sea. Erdoğan warned that Greece will pay a "heavy price" if Turkey's gas exploration vessel – in what Turkey said are disputed waters – is attacked.[300] He deemed the readmission of Greece into the military alliance NATO a mistake, claiming they were collaborating with terrorists.[301]

In March 2017, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated to the Turks in Europe, "Make not three, but five children. Because you are the future of Europe. That will be the best response to the injustices against you." This has been interpreted as an imperialist call for demographic warfare.[302]

According to The Economist, Erdoğan is the first Turkish leader to take the Turkish diaspora seriously, which has created friction within these diaspora communities and between the Turkish government and several of its European counterparts.[303]

In February 2018, President Erdoğan expressed Turkish support of the Republic of Macedonia's position during negotiations over the Macedonia naming dispute saying that Greece's position is wrong.[304]

In March 2018, President Erdoğan criticized the Kosovan Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj for dismissing his Interior Minister and Intelligence Chief for failing to inform him of an unauthorized and illegal secret operation conducted by the National Intelligence Organization of Turkey on Kosovo's territory that led to the arrest of six people allegedly associated with the Gülen movement.[305][306]

On 26 November 2019, an earthquake struck the Durrës region of Albania. President Erdoğan expressed his condolences.[307] and citing close Albanian-Turkish relations, he committed Turkey to reconstructing 500 earthquake destroyed homes and other civic structures in Laç, Albania.[308][309][310] In Istanbul, Erdoğan organised and attended a donors conference (8 December) to assist Albania that included Turkish businessmen, investors and Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama.[311]

In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive to recapture the Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh. Addressing the United Nations General Assembly, Erdoğan stated "As everyone now acknowledges, Karabakh is Azerbaijani territory. Imposition of another status [to the region] will never be accepted," and that "[Turkey] support[s] the steps taken by Azerbaijan—with whom we act together with the motto of one nation, two states—to defend its territorial integrity."[312] Erdoğan also met with Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.[313]

.jpg/440px-Prime_Minister_Keir_Starmer_attends_NATO_Summit_(53850724928).jpg)

In May 2018, British Prime Minister Theresa May welcomed Erdoğan to the United Kingdom for a three-day state visit. Erdoğan declared that the United Kingdom is "an ally and a strategic partner, but also a real friend. The cooperation we have is well beyond any mechanism that we have established with other partners."[314]