Los dacios ( / ˈd eɪ ʃ ən z / ; latín : Daci [ˈdaːkiː] ; griego : Δάκοι, [1] Δάοι, [ 1] Δάκαι [2] ) fueron los antiguos habitantes indoeuropeos de la región cultural de Dacia , ubicada en el área cercana a los montes Cárpatos y al oeste del mar Negro . A menudo se los considera un subgrupo de los tracios . [3] [4] [5] Esta área incluye principalmente los actuales países de Rumania y Moldavia , así como partes de Ucrania , [6] Serbia oriental , Bulgaria septentrional , Eslovaquia , [7] Hungría y el sur de Polonia . [6] Los dacios y los getas relacionados [8] hablaban la lengua dacia , que tiene una relación debatida con la lengua tracia vecina y puede ser un subgrupo de esta. [9] [10] Los dacios fueron influenciados culturalmente en cierta medida por los vecinos escitas y por los invasores celtas del siglo IV a . C. [11]

Los dacios eran conocidos como Geta (plural Getae ) en los escritos griegos antiguos , [ cita requerida ] y como Dacus (plural Daci ) o Getae en los documentos romanos , [13] pero también como Dagae y Gaete como se representa en el mapa romano tardío Tabula Peutingeriana . Fue Heródoto quien utilizó por primera vez el etnónimo Getae en sus Historias . [14] En griego y latín, en los escritos de Julio César , Estrabón y Plinio el Viejo , el pueblo llegó a ser conocido como "los dacios". [15] Getae y dacios eran términos intercambiables, o utilizados con cierta confusión por los griegos. [16] [17] Los poetas latinos a menudo usaban el nombre Getae . [18] Virgilio los llamó Getae cuatro veces, y Daci una vez, Luciano Getae tres veces y Daci dos veces, Horacio los nombró Getae dos veces y Daci cinco veces, mientras que Juvenal una vez Getae y dos veces Daci . [19] [20] [18] En el año 113 d. C., Adriano utilizó el término poético getae para los dacios. [21] Los historiadores modernos prefieren utilizar el nombre geto-dacios . [15] Estrabón describe a los getae y a los dacios como tribus distintas pero afines. Esta distinción se refiere a las regiones que ocupaban. [22] Estrabón y Plinio el Viejo también afirman que los getae y los dacios hablaban el mismo idioma. [22] [23]

Por el contrario, el nombre de dacios , cualquiera que sea el origen del nombre, fue utilizado por las tribus más occidentales que lindaban con los panonios y, por lo tanto, llegaron a ser conocidos por primera vez por los romanos. [24] Según la Geographica de Estrabón , el nombre original de los dacios era Δάοι " Daoi ". [1] El nombre Daoi (una de las antiguas tribus geto-dacias) fue ciertamente adoptado por observadores extranjeros para designar a todos los habitantes de los países al norte del Danubio que aún no habían sido conquistados por Grecia o Roma. [15] [15]

El nombre etnográfico Daci se encuentra bajo varias formas en fuentes antiguas. Los griegos usaban las formas Δάκοι " Dakoi " ( Estrabón , Dión Casio y Dioscórides ) y Δάοι "Daoi" (singular Daos). [25] [1] [26] [a] [27] La forma Δάοι "Daoi" se usaba con frecuencia según Esteban de Bizancio . [20]

Los latinos utilizaron las formas Davus , Dacus y una forma derivada Dacisci (Vopiscus e inscripciones). [28] [29] [30] [20]

Existen similitudes entre los etnónimos de los dacios y los de Dahae (griego Δάσαι Δάοι, Δάαι, Δαι, Δάσαι Dáoi , Dáai , Dai , Dasai ; latín Dahae , Daci ), un pueblo indoeuropeo ubicado al este del mar Caspio , hasta el primer milenio a. C. Los académicos han sugerido que hubo vínculos entre los dos pueblos desde la antigüedad. [31] [32] [33] [20] El historiador David Gordon White ha afirmado, además, que los "dacios... parecen estar relacionados con los dahae". [34] (Asimismo, White y otros académicos también creen que los nombres Dacii y Dahae también pueden tener una etimología compartida; consulte la sección siguiente para obtener más detalles).

A finales del siglo I d. C., todos los habitantes de las tierras que hoy forman Rumania eran conocidos por los romanos como daci, con la excepción de algunas tribus celtas y germánicas que se infiltraron desde el oeste, y los sármatas y pueblos relacionados desde el este. [17]

El nombre Daci , o "dacios", es un etnónimo colectivo . [35] Dio Cassius informó que los propios dacios usaban ese nombre, y los romanos los llamaban así, mientras que los griegos los llamaban getae. [36] [37] [38] Las opiniones sobre los orígenes del nombre Daci están divididas. Algunos eruditos consideran que se origina en el indoeuropeo * dha-k- , con la raíz * dhe- 'poner, colocar', mientras que otros piensan que el nombre Daci se origina en * daca 'cuchillo, daga' o en una palabra similar a dáos, que significa 'lobo' en el idioma relacionado de los frigios . [39] [40]

Una hipótesis es que el nombre Getae se origina del indoeuropeo * guet- 'pronunciar, hablar'. [41] [39] Otra hipótesis es que Getae y Daci son los nombres iraníes de dos grupos escitas de habla iraní que habían sido asimilados por la población más grande de habla tracia de la posterior "Dacia". [42] [43]

En el siglo I d. C., Estrabón sugirió que su raíz formaba un nombre que antes llevaban los esclavos: griego Daos, latín Davus (-k- es un sufijo conocido en los nombres étnicos indoeuropeos). [44] En el siglo XVIII, Grimm propuso el gótico dags o "día" que daría el significado de "luz, brillante". Sin embargo, dags pertenece a la raíz sánscrita dah- , y una derivación de Dah a Δάσαι "Daci" es difícil. [20] En el siglo XIX, Tomaschek (1883) propuso la forma "Dak", que significa aquellos que entienden y pueden hablar , al considerar "Dak" como una derivación de la raíz da ("k" es un sufijo); cf. sánscrito dasa , bactriano daonha . [45] Tomaschek también propuso la forma "Davus", que significa "miembros del clan/compatriota" cf. Daqyu bactriano , danhu "cantón". [45]

Desde el siglo XIX, muchos estudiosos han propuesto un vínculo etimológico entre el endónimo de los dacios y los lobos.

Sin embargo, según el historiador y arqueólogo rumano Alexandru Vulpe , la etimología dacia explicada por daos ("lobo") tiene poca plausibilidad, ya que la transformación de daos en dakos es fonéticamente improbable y el estándar draco no era exclusivo de los dacios. Por lo tanto, lo descarta como etimología popular . [53]

Otra etimología, vinculada a las raíces lingüísticas protoindoeuropeas *dhe- que significa "establecer, colocar" y dheua → dava ("asentamiento") y dhe-k → daci, es apoyada por el historiador rumano Ioan I. Russu (1967). [54]

Mircea Eliade intentó, en su libro De Zalmoxis a Genghis Khan , dar una base mitológica a una supuesta relación especial entre los dacios y los lobos: [55]

La evidencia de proto-tracios o proto-dacios en el período prehistórico depende de los restos de la cultura material . En general, se propone que un pueblo proto-dacio o proto-tracio se desarrolló a partir de una mezcla de pueblos indígenas e indoeuropeos de la época de la expansión protoindoeuropea en la Edad del Bronce Temprano (3300-3000 a. C.) [65] cuando estos últimos, alrededor de 1500 a. C., conquistaron a los pueblos indígenas. [66] Los pueblos indígenas eran agricultores del Danubio, y los pueblos invasores del tercer milenio a. C. eran guerreros-pastores kurganos de las estepas ucranianas y rusas. [67]

La indoeuropeización se completó a principios de la Edad del Bronce. La mejor descripción de los pueblos de esa época es la de los prototracios, que más tarde, en la Edad del Hierro, se transformaron en los geto-dacios del Danubio y los Cárpatos, así como en los tracios de la península balcánica oriental. [68]

Entre el siglo XV y el XII a. C., la cultura dacio-getae estuvo influenciada por los guerreros de los túmulos y campos de urnas de la Edad del Bronce que se dirigían a través de los Balcanes hacia Anatolia. [69]

En los siglos VIII al VII a. C., la migración de los escitas desde el este hacia la estepa póntica empujó hacia el oeste y lejos de las estepas al pueblo agatirsi escita relacionado que había habitado anteriormente en la estepa póntica alrededor del lago Maeotis . [70] Después de esto, los agatirsos se establecieron en los territorios de la actual Moldavia , Transilvania y posiblemente Oltenia , donde se mezclaron con la población indígena de origen tracio . [71] [70] Cuando los agatirsos fueron más tarde completamente asimilados por las poblaciones geto-tracias, [71] sus asentamientos fortificados se convirtieron en los centros de los grupos geticos que más tarde se transformarían en la cultura dacia; una parte importante del pueblo dacio descendía de los agatirsos. [71] Cuando los celtas de La Tène llegaron en el siglo IV a. C., los dacios estaban bajo la influencia de los escitas. [69]

Alejandro Magno atacó a los getas en el año 335 a. C. en el bajo Danubio, pero en el año 300 a. C. ya habían formado un estado fundado en una democracia militar y comenzaron un período de conquista. [69] Más celtas llegaron durante el siglo III a. C., y en el siglo I a. C. el pueblo de Boyos intentó conquistar parte del territorio dacio en el lado oriental del río Teiss. Los dacios expulsaron a los boyos hacia el sur a través del Danubio y fuera de su territorio, momento en el que los boyos abandonaron cualquier plan de invasión. [69]

Algunos historiadores húngaros consideran que los dacios y los getas son las mismas tribus escitas de los dahae , los masagetas y también el exónimo Daxia con Dacia. [52] [72]

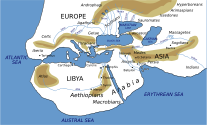

Al norte del Danubio, los dacios ocupaban [ ¿cuándo? ] un territorio más grande que la Dacia ptolemaica, [ aclaración necesaria ] extendiéndose entre Bohemia en el oeste y las cataratas del Dniéper en el este, y hasta los ríos Prípiat , Vístula y Óder en el norte y noroeste. [73] [ mejor fuente necesaria ] En el 53 a. C., Julio César declaró que el territorio dacio [ aclaración necesaria ] estaba en la frontera oriental del bosque hercínico . [69] Según la Geographica de Estrabón , escrita alrededor del 20 d. C., [74] los getes (geto-dacios) limitaban con los suevos que vivían en el bosque hercínico , que está en algún lugar en las proximidades del río Duria, el actual Váh (Waag). [75] Los dacios vivían a ambos lados del Danubio. [76] [77] Según Estrabón , los moesios también vivían a ambos lados del Danubio. [38] Según Agripa , [78] Dacia estaba limitada por el océano Báltico al norte y por el Vístula al oeste. [79] Los nombres de las personas y los asentamientos confirman las fronteras de Dacia según lo descrito por Agripa. [78] [80] El pueblo dacio también vivía al sur del Danubio. [78]

Los dacios y getas siempre fueron considerados tracios por los antiguos (Dión Casio, Trogo Pompeyo, Apiano , Estrabón y Plinio el Viejo), y se decía que ambos hablaban la misma lengua tracia . [81] [82] La afiliación lingüística del dacio es incierta, ya que la antigua lengua indoeuropea en cuestión se extinguió y dejó rastros muy limitados, generalmente en forma de nombres de lugares, nombres de plantas y nombres personales. El tracodacio (o tracio y dacomisio) [ ¿cuál? ] parece pertenecer al grupo oriental (satem) de lenguas indoeuropeas. [ ¿por qué? ] [83] Hay dos teorías contradictorias: algunos eruditos (como Tomaschek 1883; Russu 1967; Solta 1980; Crossland 1982; Vraciu 1980) consideran que el dacio es una lengua tracia o un dialecto de la misma. Esta opinión es apoyada por RG Solta, quien dice que el tracio y el dacio son lenguas muy estrechamente relacionadas. [9] [10] Otros eruditos (como Georgiev 1965, Duridanov 1976) consideran que el tracio y el dacio son dos lenguas indoeuropeas diferentes y específicas que no pueden reducirse a una lengua común. [84] Lingüistas como Polomé y Katičić expresaron reservas [ aclaración necesaria ] sobre ambas teorías. [85]

En general, se considera que los dacios eran hablantes de tracio, lo que representa una continuidad cultural de las comunidades anteriores de la Edad de Hierro llamadas vagamente geticas. [86] Dado que en una interpretación, el dacio es una variedad del tracio, por razones de conveniencia, se utiliza el término genérico "daco-tracio", con "dacio" reservado para el idioma o dialecto que se hablaba al norte del Danubio, en la actual Rumania y el este de Hungría, y "tracio" para la variedad hablada al sur del Danubio. [87] No hay duda de que la lengua tracia estaba relacionada con la lengua dacia que se hablaba en lo que hoy es Rumania, antes de que parte de esa área fuera ocupada por los romanos. [88] Además, tanto el tracio como el dacio tienen uno de los principales cambios característicos de las lenguas indoeuropeas, *k y *g a *s y *z. [89] Con respecto al término "getico" (getae), aunque se han hecho intentos para distinguir entre dacio y getico, no parece haber ninguna razón convincente para ignorar el punto de vista de El geógrafo griego Estrabón afirmó que los dacios y los getas, tribus tracias que habitaban al norte del Danubio (los dacios al oeste de la zona y los getas más al este), eran el mismo pueblo y hablaban el mismo idioma. [87]

Otra variedad que a veces se ha reconocido es la de moesio (o misio) para la lengua de una zona intermedia inmediatamente al sur del Danubio en Serbia, Bulgaria y la Dobruja rumana: este y los dialectos al norte del Danubio se han agrupado juntos como daco-moesio. [87] La lengua de la población indígena no ha dejado casi ningún rastro en la antroponimia de Moesia, pero la toponimia indica que los moesios en la orilla sur del Danubio, al norte de los montes Haemus, y los tribali en el valle del Morava, compartían una serie de rasgos lingüísticos característicos [ especificar ] con los dacios al sur de los Cárpatos y los getae en la llanura de Valaquia, lo que los distingue de los tracios, aunque sus lenguas están indudablemente relacionadas. [90]

La cultura dacia se estudia principalmente a través de fuentes romanas. Hay abundantes pruebas de que eran una potencia regional en la ciudad de Sarmizegetusa y sus alrededores . Sarmizegetusa era su capital política y espiritual. La ciudad en ruinas se encuentra en lo alto de las montañas del centro de Rumania. [91]

Vladimir Georgiev niega que el dacio y el tracio estuvieran estrechamente relacionados por varias razones, la más notable es que los nombres de las ciudades dacias y moesias suelen terminar con el sufijo -DAVA , mientras que las ciudades de Tracia propiamente dicha (es decir, al sur de los Balcanes ) generalmente terminan en -PARA (véase lengua dacia ). Según Georgiev, la lengua hablada por los dacios étnicos debería clasificarse como "daco-moesia" y considerarse distinta del tracio. Georgiev también afirmó que los nombres de la Dacia y Moesia, aproximadamente romanas, muestran cambios diferentes y generalmente menos extensos en las consonantes y vocales indoeuropeas que los que se encuentran en la propia Tracia. Sin embargo, la evidencia parece indicar la divergencia de una lengua traco-dacia en grupos de dialectos del norte y del sur, no tan diferentes como para calificar como lenguas separadas. [92] Polomé considera que tal diferenciación léxica ( -dava vs. para ) sería, sin embargo, apenas evidencia suficiente para separar el daco-moesio del tracio. [85]

Un extenso relato de las tribus nativas de Dacia se puede encontrar en la novena tabula de Europa de la Geografía de Ptolomeo . [93] La Geografía probablemente fue escrita en el período 140-150 d. C., pero las fuentes a menudo eran anteriores; por ejemplo, la Britania romana se muestra antes de la construcción del Muro de Adriano en los años 120 d. C. [94] La Geografía de Ptolomeo también contiene un mapa físico probablemente diseñado antes de la conquista romana, y que no contiene una nomenclatura detallada. [95] Hay referencias a la Tabula Peutingeriana , pero parece que el mapa dacio de la Tabula se completó después del triunfo final de la nacionalidad romana. [96] La lista de Ptolomeo incluye no menos de doce tribus con nombres geto-dacios. [97] [98]

Las quince tribus de Dacia nombradas por Ptolomeo, comenzando por las más septentrionales, son las siguientes. En primer lugar, los anartes , los teuriscos y los coertobocos/ costobocos . Al sur de ellos están los buredeenses ( buri / burs ), los cotenses/ cotini y luego los albocenses , los potulatenses y los sense , mientras que los más meridionales eran los saldenses , los ciaginsi y los piephigi . Al sur de ellos estaban los predasenses /predavenses, los rhadacenos /rhatacenses, los caucoenses (cauci) y los biephi . [93] Doce de estas quince tribus enumeradas por Ptolomeo son étnicamente dacias, [98] y tres son celtas: anarti, teuriscos y cotenses. [98] También hay breves menciones previas de otras tribus getas o dacias en las orillas izquierda y derecha del Danubio, o incluso en Transilvania, que se añadirían a la lista de Ptolomeo . Entre estas otras tribus están los trixae , los crobidos y los apúlicos . [93]

Algunos pueblos que habitaban la región generalmente descrita en tiempos romanos como "Dacia" no eran dacios étnicos. [99] Los verdaderos dacios eran un pueblo de ascendencia tracia. Elementos germanos (daco-germanos), elementos celtas (daco-celtas) y elementos iraníes (daco-sármatas) ocuparon territorios en el noroeste y noreste de Dacia. [100] [101] [99] Esta región cubría aproximadamente la misma área que la Rumania moderna más Besarabia (República de Moldavia ) y el este de Galicia (suroeste de Ucrania), aunque Ptolomeo ubica Moldavia y Besarabia en Sarmatia Europaea , en lugar de Dacia . [102] Después de las Guerras Dacias (101-6 d. C.), los romanos ocuparon solo aproximadamente la mitad de la región dacia más amplia. La provincia romana de Dacia cubría desde el oeste de Valaquia hasta el Limes Transalutanus (al este del río Alutus u Olt ) y Transilvania , hasta su frontera con los Cárpatos. [103]

El impacto de la conquista romana sobre este pueblo es incierto. Una hipótesis es que fueron eliminados de manera efectiva. Una pista importante sobre el carácter de las bajas dacias la ofrecen las fuentes antiguas Eutropio y Critón. Ambos hablan de hombres cuando describen las pérdidas sufridas por los dacios en las guerras. Esto sugiere que ambos se refieren a pérdidas debidas a los combates, no a un proceso de exterminio de toda la población. [104] Un fuerte componente del ejército dacio, incluidos los bastarnos celtas y los germanos, se habían retirado en lugar de someterse a Trajano. [105] Algunas escenas en la Columna de Trajano representan actos de obediencia de la población dacia, y otras muestran a los dacios refugiados regresando a sus propios lugares. [106] En la Columna de Trajano se representan dacios que intentan comprar amnistía (uno ofrece a Trajano una bandeja con tres lingotes de oro). [107] Alternativamente, un número sustancial puede haber sobrevivido en la provincia, aunque probablemente fueron superados en número por los inmigrantes romanizados. [108] La vida cultural en Dacia se volvió muy mixta y decididamente cosmopolita debido a las comunidades coloniales. Los dacios conservaron sus nombres y sus propias costumbres en medio de los recién llegados, y la región continuó exhibiendo características dacias. [109] Los dacios que sobrevivieron a la guerra están atestiguados como rebeldes contra la dominación romana en Dacia al menos dos veces, en el período de tiempo inmediatamente posterior a las Guerras Dacias, y de manera más decidida en el 117 d. C. [ 110] En el 158 d. C., se rebelaron nuevamente y fueron reprimidos por Marco Estacio Prisco. [111] Al parecer, algunos dacios fueron expulsados de la zona ocupada al final de cada una de las dos Guerras Dacias o emigraron de otra manera. No se sabe con certeza dónde se asentaron estos refugiados. Algunas de estas personas podrían haberse mezclado con las tribus étnicas dacias existentes más allá de los Cárpatos (los costobocos y los carpos).

Tras la conquista de Dacia por Trajano, se produjeron problemas recurrentes relacionados con los grupos dacios excluidos de la provincia romana, tal y como la definió finalmente Adriano. A principios del siglo III, los «dacios libres», como se los conocía anteriormente, eran un grupo significativamente problemático, identificado entonces como los carpos, que requirieron la intervención imperial en más de una ocasión. [112] En 214 Caracalla se enfrentó a sus ataques. Más tarde, Filipo el Árabe vino en persona para ocuparse de ellos; asumió el título triunfal de Carpico Máximo e inauguró una nueva era para la provincia de Dacia (20 de julio de 246). Más tarde, tanto Decio como Galieno asumieron los títulos de Dacicus Maximus. En 272, Aureliano asumió el mismo título que Filipo. [112]

En el año 140 d. C., Ptolomeo enumera los nombres de varias tribus que residían en los márgenes de la Dacia romana (oeste, este y norte de la cordillera de los Cárpatos), y el panorama étnico parece ser mixto. Al norte de los Cárpatos se registran los anarti, los teuriscos y los costobocos. [113] Los anarti (o anartes) y los teuriscos probablemente eran originalmente pueblos celtas o una mezcla de dacios y celtas. [101] Los anarti, junto con los celtas cotini , son descritos por Tácito como vasallos del poderoso pueblo germánico quadi . [114] Los teuriscos probablemente eran un grupo de tauriscos celtas de los Alpes orientales . Sin embargo, la arqueología ha revelado que las tribus celtas se habían extendido originalmente de oeste a este hasta Transilvania, antes de ser absorbidas por los dacios en el siglo I a. C. [115] [116]

La opinión principal es que los costobocos eran étnicamente dacios. [117] Otros los consideraban una tribu eslava o sármata. [118] [119] También hubo una influencia celta, por lo que algunos los consideran un grupo mixto celta y tracio que aparece, después de la conquista de Trajano, como un grupo dacio dentro del superestrato celta. [120] Los costobocos habitaban las laderas meridionales de los Cárpatos. [121] Ptolomeo nombró a los coestobocos (costobocos en fuentes romanas) dos veces, mostrándolos divididos por el Dniéster y los montes Peucinos (Cárpatos). Esto sugiere que vivían en ambos lados de los Cárpatos, pero también es posible que se combinaran dos relatos sobre el mismo pueblo. [121] También había un grupo, los transmontanos, que algunos eruditos modernos identifican como costobocos transmontanos dacios del extremo norte. [122] [123] El nombre Transmontani proviene del latín dacio, [124] literalmente "gente sobre las montañas". Mullenhoff los identificó con los Transiugitani, otra tribu dacia al norte de los montes Cárpatos. [125]

Basándose en el relato de Dio Cassius , Heather (2010) considera que los vándalos de Hasding, alrededor del año 171 d. C., intentaron tomar el control de tierras que anteriormente pertenecían al grupo dacio libre llamado los costobocios. [126] Hrushevskyi (1997) menciona que la opinión generalizada anterior de que estas tribus de los Cárpatos eran eslavas no tiene base. Esto se contradice con los propios nombres coestobocos que se conocen por las inscripciones, escritas por un coestoboco y, por lo tanto, presumiblemente con precisión. Estos nombres suenan bastante diferentes a todo lo eslavo. [118] Eruditos como Tomaschek (1883), Schütte (1917) y Russu (1969) consideran que estos nombres costobocios son tracodacios. [127] [128] [129] Esta inscripción también indica el origen dacio de la esposa del rey costobocio "Ziais Tiati filia Daca". [130] Esta indicación de la línea de descendencia sociofamiliar que se ve también en otras inscripciones (es decir, Diurpaneus qui Euprepes Sterissae f(ilius) Dacus) es una costumbre atestiguada desde el período histórico (que comienza en el siglo V a. C.) cuando los tracios estaban bajo la influencia griega. [131] Es posible que no se haya originado con los tracios, ya que podría ser simplemente una moda prestada de los griegos para especificar la ascendencia y para distinguir a los individuos homónimos dentro de la tribu. [132] Schütte (1917), Parvan y Florescu (1982) señalaron también los nombres de lugares característicos dacios que terminan en '–dava' dados por Ptolomeo en el país de los costobocos. [133] [134]

Los carpos eran un grupo considerable de tribus que vivían más allá de la frontera nororiental de la Dacia romana. La opinión mayoritaria entre los estudiosos modernos es que los carpos eran una tribu del norte de Tracia y un subgrupo de los dacios. [135] Sin embargo, algunos historiadores los clasifican como eslavos. [136] Según Heather (2010), los carpos eran dacios de las estribaciones orientales de la cordillera de los Cárpatos (la actual Moldavia y Valaquia) que no habían sido sometidos al dominio romano directo en el momento de la conquista de la Dacia de Transilvania por parte de Trajano. Después de que generaron un nuevo grado de unidad política entre ellos en el transcurso del siglo III, estos grupos dacios llegaron a ser conocidos colectivamente como los carpos. [137]

Las fuentes antiguas sobre los Carpi, anteriores al año 104 d. C., los ubicaban en un territorio situado entre el lado occidental de la Galicia de Europa del Este y la desembocadura del Danubio. [138] El nombre de la tribu es homónimo de los montes Cárpatos. [122] Carpi y cárpato son palabras dacias derivadas de la raíz (s)ker - "cortar" cf. albanés karp "piedra" y sánscrito kar - "cortar". [139] [140] Una cita del cronista bizantino del siglo VI Zósimo que se refiere a los carpo-dacios (griego: Καρποδάκαι, latín: Carpo-Dacae ), que atacaron a los romanos a finales del siglo IV, se considera una prueba de su etnia dacia. De hecho, Carpi/Carpodaces es el término utilizado para los dacios fuera de Dacia propiamente dicha. [141] Sin embargo, que los Carpi eran dacios no lo demuestra tanto la forma Καρποδάκαι en Zosimus sino sus topónimos característicos en – dava , dados por Ptolomeo en su país. [142] El origen y las afiliaciones étnicas de los Carpi han sido debatidos a lo largo de los años; en los tiempos modernos están estrechamente asociados con los montes Cárpatos, y se ha defendido con buenos argumentos a favor de atribuirles una cultura material distinta, "una forma desarrollada de la cultura geto-dacia de La Tene", a menudo conocida como la cultura Poienesti, que es característica de esta zona. [143]

Los dacios están representados en las estatuas que coronan el Arco de Constantino y en la Columna de Trajano . [12] El artista de la Columna se esforzó por representar, en su opinión, una variedad de personas dacias, desde hombres, mujeres y niños de alto rango hasta los casi salvajes. Aunque el artista buscó modelos en el arte helenístico para algunos tipos de cuerpo y composiciones, no representa a los dacios como bárbaros genéricos. [144]

Los autores clásicos aplicaron un estereotipo generalizado al describir a los "bárbaros" (celtas, escitas, tracios) que habitaban las regiones al norte del mundo griego. [145] De acuerdo con este estereotipo, todos estos pueblos son descritos, en marcado contraste con los griegos "civilizados", como mucho más altos, de piel más clara y con cabello lacio de color claro y ojos azules. [145] Por ejemplo, Aristóteles escribió que "los escitas del Mar Negro y los tracios tienen el cabello lacio, porque tanto ellos mismos como el aire circundante son húmedos"; [146] según Clemente de Alejandría , Jenófanes describió a los tracios como "rubicundos y morenos". [145] [147] En la columna de Trajano, el cabello de los soldados dacios está representado más largo que el de los soldados romanos y tenían barbas recortadas. [148]

La pintura corporal era una costumbre entre los dacios. [ especificar ] Es probable que el tatuaje tuviera originalmente un significado religioso. [149] Practicaban el tatuaje o pintura corporal simbólico-ritual tanto para hombres como para mujeres, con símbolos hereditarios transmitidos hasta la cuarta generación. [150]

En ausencia de registros históricos escritos por los propios dacios (y tracios), el análisis de sus orígenes depende en gran medida de los restos de la cultura material. En general, la Edad del Bronce fue testigo de la evolución de los grupos étnicos que surgieron durante el período Eneolítico y, finalmente, del sincretismo de elementos tanto autóctonos como indoeuropeos de las estepas y las regiones pónticas. [151] Varios grupos de tracios no se habían separado hacia el 1200 a. C., [151] pero existen fuertes similitudes entre los tipos cerámicos encontrados en Troya y los tipos cerámicos del área de los Cárpatos. [151] Alrededor del año 1000 a. C., los países de los Cárpatos y el Danubio estaban habitados por una rama septentrional de los tracios. [152] En el momento de la llegada de los escitas (c. 700 a. C.), los tracios de los Cárpatos y el Danubio estaban evolucionando rápidamente hacia la civilización de la Edad del Hierro de Occidente. Además, todo el cuarto período de la Edad del Bronce de los Cárpatos ya había sido profundamente influenciado por la primera Edad del Hierro tal como se desarrolló en Italia y las tierras alpinas. Los escitas, que llegaron con su propio tipo de civilización de la Edad del Hierro, pusieron fin a estas relaciones con Occidente. [153] A partir de aproximadamente el año 500 a. C. (la segunda Edad del Hierro), los dacios desarrollaron una civilización distinta, capaz de sustentar grandes reinos centralizados en el siglo I a. C. y el siglo I d. C. [154]

Desde el primer relato detallado de Heródoto, se reconoce que los getas pertenecen a los tracios. [14] Aun así, se distinguen de los demás tracios por particularidades de religión y costumbres. [145] La primera mención escrita del nombre "dacios" se encuentra en fuentes romanas, pero los autores clásicos son unánimes en considerarlos una rama de los getas, un pueblo tracio conocido por escritos griegos. Estrabón especificó que los dacios son los getas que vivían en el área hacia la llanura de Panonia ( Transilvania ), mientras que los getas propiamente dichos gravitaban hacia la costa del Mar Negro ( Escitia Menor ).

Desde los escritos de Heródoto en el siglo V a. C., [14] los getas/dacios son reconocidos como pertenecientes a la esfera de influencia tracia. A pesar de esto, se distinguen de otros tracios por particularidades de religión y costumbres. [145] Los geto-dacios y los tracios eran pueblos emparentados pero no eran lo mismo. [155] Las diferencias con los tracios del sur o con los vecinos escitas eran probablemente tenues, ya que varios autores antiguos confunden la identificación con ambos grupos. [145] El lingüista Vladimir Georgiev dice que basándose en la ausencia de topónimos que terminan en dava en el sur de Bulgaria , los moesios y los dacios (o como él los llama dacomisios) no podrían estar relacionados con los tracios . [156]

En el siglo XIX, Tomaschek consideró una estrecha afinidad entre los beso-tracios y los getae-dacios, un parentesco original de ambos pueblos con los pueblos iranios. [157] Son tribus arias , varios siglos antes de que los escolotes del Pont y los sauromatae abandonaran la patria aria y se establecieran en la cadena de los Cárpatos, en los montes Haemus (Balcanes) y Ródope . [157] Los beso-tracios y los getae-dacios se separaron muy pronto de los arios, ya que su lengua aún mantiene raíces que faltan en el iranio y muestra características fonéticas no iraníes (es decir, reemplazando la "l" iraní por "r"). [157]

Los geto-dacios habitaron ambas orillas del río Tisa antes del ascenso de los boyos celtas , y nuevamente después de que estos últimos fueran derrotados por los dacios bajo el rey Burebista. [158] Durante la segunda mitad del siglo IV a. C., la influencia cultural celta aparece en los registros arqueológicos del Danubio medio, la región alpina y el noroeste de los Balcanes, donde era parte de la cultura material de La Tène medio . Este material aparece en el noroeste y centro de Dacia, y se refleja especialmente en los entierros. [154] Los dacios absorbieron la influencia celta del noroeste a principios del siglo III a. C. [159] La investigación arqueológica de este período ha resaltado varias tumbas de guerreros celtas con equipo militar. Sugiere la penetración forzada de una élite militar celta dentro de la región de Dacia, ahora conocida como Transilvania, que limita al este con la cordillera de los Cárpatos. [154] Los yacimientos arqueológicos de los siglos III y II a. C. en Transilvania revelaron un patrón de coexistencia y fusión entre los portadores de la cultura de La Tène y los dacios indígenas. Se trataba de viviendas domésticas con una mezcla de cerámica celta y dacia, y varias tumbas de estilo celta que contenían vasijas de tipo dacio. [154] Hay unos setenta yacimientos celtas en Transilvania, en su mayoría cementerios, pero la mayoría de ellos, si no todos, indican que la población nativa imitó las formas de arte celta que les gustaban, pero se mantuvo obstinadamente y fundamentalmente dacia en su cultura. [159]

El casco celta de Ciumeşti , Satu Mare , Rumania (norte de Dacia), un casco totémico de cuervo de la Edad de Hierro, que data del siglo IV a. C. Un casco similar está representado en el caldero tracocelta de Gundestrup , siendo usado por uno de los guerreros montados (detalle etiquetado aquí). Véase también una ilustración de Brennos con un casco similar. Alrededor del 150 a. C., el material de La Tène desaparece de la zona. Esto coincide con los escritos antiguos que mencionan el ascenso de la autoridad dacia. Terminó la dominación celta, y es posible que los celtas fueran expulsados de Dacia. Alternativamente, algunos académicos han propuesto que los celtas de Transilvania permanecieron, pero se fusionaron con la cultura local y, por lo tanto, dejaron de ser distintivos. [154] [159]

Archaeological discoveries in the settlements and fortifications of the Dacians in the period of their kingdoms (1st century BC and 1st century AD) included imported Celtic vessels and others made by Dacian potters imitating Celtic prototypes, showing that relations between the Dacians and the Celts from the regions north and west of Dacia continued.[160] In present-day Slovakia, archaeology has revealed evidence for mixed Celtic-Dacian populations in the Nitra and Hron river basins.[161]

After the Dacians subdued the Celtic tribes, the remaining Cotini stayed in the mountains of Central Slovakia, where they took up mining and metalworking. Together with the original domestic population, they created the Puchov culture that spread into central and northern Slovakia, including Spis, and penetrated northeastern Moravia and southern Poland. Along the Bodrog River in Zemplin they created Celtic-Dacian settlements which were known for the production of painted ceramics.[161]

Herodotus says: "before Darius reached the Danube, the first people he subdued were the Getae, who believed that they never die".[14] A persian clay tablet found at Gherla mentions Darius and although the Persian army probably did not reach the modern findspot of the tablet, the object is probably evidence of the Persian campaign to Dacia.[162]

It is possible that the Persian expedition and the subsequent occupation may have altered the way in which the Getae expressed the immortality belief. The influence of thirty years of Achaemenid presence may be detected in the emergence of an explicit iconography of the "Royal Hunt" that influenced Dacian and Thracian metalworkers, and of the practice of hawking by their upper class.[citation needed]

Greek and Roman chroniclers record the defeat and capture of the Macedonian general Lysimachus in the 3rd century BC by the Getae (Dacians) ruled by Dromihete, their military strategy, and the release of Lysimachus following a debate in the assembly of the Getae.[163]

The Scythians' arrival in the Carpathian mountains is dated to 700 BC.[164] The Agathyrsi of Transylvania had been mentioned by Herodotus (fifth century BC),[165] who regarded them as not a Scythian people, but closely related to them. In other respects, their customs were close to those of the Thracians.[166] The Agathyrsi were completely denationalized at the time of Herodotus and absorbed by the native Thracians.[167][164]

The opinion that the Agathyrsi were almost certainly Thracians results also from the writings preserved by Stephen of Byzantium, who explains that the Greeks called the Trausi the Agathyrsi, and we know that the Trausi lived in the Rhodope Mountains. Certain details from their way of life, such as tattooing, also suggest that the Agathyrsi were Thracians. Their place was later taken by the Dacians.[168] That the Dacians were of Thracian stock is not in doubt, and it is safe to assume that this new name also encompassed the Agathyrsi, and perhaps other neighbouring Thracian people as well, as a result of some political upheaval.[168]

The Goths, a confederation of east German peoples, arrived in southern Ukraine no later than 230.[169] During the next decade, a large section of them moved down the Black Sea coast and occupied much of the territory north of the lower Danube.[169] The Goths' advance towards the area north of the Black Sea involved competing with the indigenous population of Dacian-speaking Carpi, as well as indigenous Iranian-speaking Sarmatians and Roman garrison forces.[170] The Carpi, often called "Free Dacians", continued to dominate the anti-Roman coalition made up of themselves, Taifali, Astringi, Vandals, Peucini, and Goths until 248, when the Goths assumed the hegemony of the loose coalition.[171] The first lands taken over by the Thervingi Goths were in Moldavia, and only during the fourth century did they move in strength down into the Danubian plain.[172] The Carpi found themselves squeezed between the advancing Goths and the Roman province of Dacia.[169] In 275 AD, Aurelian surrendered the Dacian territory[clarification needed] to the Carpi and the Goths.[173] Over time, Gothic power in the region grew, at the Carpi's expense. The Germanic-speaking Goths replaced native Dacian-speakers as the dominant force around the Carpathian mountains.[174] Large numbers of Carpi, but not all of them, were admitted into the Roman empire in the twenty-five years or so after 290 AD.[175] Despite this evacuation of the Carpi around 300 AD, considerable groups of the natives (non-Romanized Dacians, Sarmatians and others) remained in place under Gothic domination.[176]

In 330 AD, the Gothic Thervingi contemplated moving to the Middle Danube region,[citation needed] and from 370 relocated with their fellow Gothic Greuthungi to new homes in the Roman Empire.[175] The Ostrogoths were still more isolated, but even the Visigoths preferred to live among their own kind. As a result, the Goths settled in pockets. Finally, although Roman towns continued on a reduced level, there is no question as to their survival.[172]

In 336 AD, Constantine took the title Dacicus Maximus 'great victor in Dacia', implying at least partial reconquest of Trajan Dacia.[177] In an inscription of 337, Constantine was commemorated officially as Germanicus Maximus, Sarmaticus, Gothicus Maximus, and Dacicus Maximus, meaning he had defeated the Germans, Sarmatians, Goths, and Dacians.[178]

Dacian polities arose as confederacies that included the Getae, the Daci, the Buri, and the Carpi[dubious – discuss] (cf. Bichir 1976, Shchukin 1989),[158] united only periodically by the leadership of Dacian kings such as Burebista and Decebal. This union was both military-political and ideological-religious[158] on ethnic basis. The following are some of the attested Dacian kingdoms:

The kingdom of Cothelas, one of the Getae, covered an area near the Black Sea, between northern Thrace and the Danube, today Bulgaria, in the 4th century BC.[179] The kingdom of Rubobostes controlled a region in Transylvania in the 2nd century BC.[180] Gaius Scribonius Curio (proconsul 75–73 BC) campaigned successfully against the Dardani and the Moesi, becoming the first Roman general to reach the river Danube with his army.[181] His successor, Marcus Licinius Lucullus, brother of the famous Lucius Lucullus, campaigned against the Thracian Bessi tribe and the Moesi, ravaging the whole of Moesia, the region between the Haemus (Balkan) mountain range and the Danube. In 72 BC, his troops occupied the Greek coastal cities of Scythia Minor (the modern Dobrogea region in Romania and Bulgaria), which had sided with Rome's Hellenistic arch-enemy, king Mithridates VI of Pontus, in the Third Mithridatic War.[182] Greek geographer Strabo claimed that the Dacians and Getae had been able to muster a combined army of 200,000 men during Strabo's era, the time of Roman emperor Augustus.[183]

The Dacian kingdom reached its maximum extent under king Burebista (ruled 82 – 44 BC). The capital of the kingdom was possibly the city of Argedava, also called Sargedava in some historical writings, situated close to the river Danube. The kingdom of Burebista extended south of the Danube, in what is today Bulgaria, and the Greeks believed their king was the greatest of all Thracians.[184][better source needed] During his reign, Burebista transferred the Geto-Dacians' capital from Argedava to Sarmizegetusa.[185][186] For at least one and a half centuries, Sarmizegethusa was the Dacian capital, reaching its peak under king Decebalus. Burebista annexed the Greek cities on the Pontus.(55–48 BC).[187] Augustus wanted to avenge the defeat of Gaius Antonius Hybrida at Histria (Sinoe) 32 years before, and to recover the lost standards. These were held in a powerful fortress called Genucla (Isaccea, near modern Tulcea, in the Danube delta region of Romania), controlled by Zyraxes, the local Getan petty king.[188] The man selected for the task was Marcus Licinius Crassus, grandson of Crassus the triumvir, and an experienced general at 33 years of age, who was appointed proconsul of Macedonia in 29 BC.[189]

By the year AD 100, more than 400,000 square kilometres were dominated by the Dacians, who numbered two million.[b] Decebalus was the last king of the Dacians, and despite his fierce resistance against the Romans was defeated, and committed suicide rather than being marched through Rome in a triumph as a captured enemy leader.

Burebista's Dacian state was powerful enough to threaten Rome, and Caesar contemplated campaigning against the Dacians.[citation needed] Despite this, the formidable Dacian power under Burebista lasted only until his death in 44 BC. The subsequent division of Dacia continued for about a century until the reign of Scorilo. This was a period of only occasional attacks on the Roman Empire's border, with some local significance.[190]

The unifying actions of the last Dacian king Decebalus (ruled 87–106 AD) were seen as dangerous by Rome. Despite the fact that the Dacian army could now gather only some 40,000 soldiers,[190] Decebalus' raids south of the Danube proved unstoppable and costly. In the Romans' eyes, the situation at the border with Dacia was out of control, and Emperor Domitian (ruled 81 to 96 AD) tried desperately to deal with the danger through military action. But the outcome of Rome's disastrous campaigns into Dacia in AD 86 and AD 88 pushed Domitian to settle the situation through diplomacy.[190]

Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 AD) opted for a different approach and decided to conquer the Dacian kingdom, partly in order to seize its vast gold mines wealth. The effort required two major wars (the Dacian Wars), one in 101–102 AD and the other in 105–106 AD. Only fragmentary details survive of the Dacian war: a single sentence of Trajan's own Dacica; little more of the Getica written by his doctor, T. Statilius Crito; nothing whatsoever of the poem proposed by Caninius Rufus (if it was ever written), Dio Chrysostom's Getica or Appian's Dacica. Nonetheless, a reasonable account can be pieced together.[191]

In the first war, Trajan invaded Dacia by crossing the river Danube with a boat-bridge and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Dacians at the Second Battle of Tapae in 101 AD. The Dacian king Decebalus was forced to sue for peace. Trajan and Decebalus then concluded a peace treaty which was highly favourable to the Romans. The peace agreement required the Dacians to cede some territory to the Romans and to demolish their fortifications. Decebalus' foreign policy was also restricted, as he was prohibited from entering into alliances with other tribes.

However, both Trajan and Decebalus considered this only a temporary truce and readied themselves for renewed war. Trajan had Greek engineer Apollodorus of Damascus construct a stone bridge over the Danube river, while Decebalus secretly plotted alliances against the Romans.[citation needed] In 105, Trajan crossed the Danube river and besieged Decebalus' capital, Sarmizegetusa, but the siege failed because of Decebalus' allied tribes. However, Trajan was an optimist. He returned with a newly constituted army and took Sarmizegetusa by treachery. Decebalus fled into the mountains, but was cornered by pursuing Roman cavalry. Decebalus committed suicide rather than being captured by the Romans and be paraded as a slave, then be killed. The Roman captain took his head and right hand to Trajan, who had them displayed in the Forums. Trajan's Column in Rome was constructed to celebrate the conquest of Dacia.

The Roman people hailed Trajan's triumph in Dacia with the longest and most expensive celebration in their history, financed by a part of the gold taken from the Dacians.[citation needed] For his triumph, Trajan gave a 123-day festival (ludi) of celebration, in which approximately 11,000 animals were slaughtered and 11,000 gladiators fought in combats. This surpassed Emperor Titus's celebration in AD 70, when a 100-day festival included 3,000 gladiators and 5,000 to 9,000 wild animals.[192]

Only about half part of Dacia then became a Roman province,[193] with a newly built capital at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, 40 km away from the site of Old Sarmisegetuza Regia, which was razed to the ground. The name of the Dacians' homeland, Dacia, became the name of a Roman province, and the name Dacians was used to designate the people in the region.[3] Roman Dacia, also Dacia Traiana or Dacia Felix, was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271 or 275 AD.[194][unreliable source?][195][196] Its territory consisted of eastern and southeastern Transylvania, and the regions of Banat and Oltenia (located in modern Romania).[194] Dacia was organised from the beginning as an imperial province, and remained so throughout the Roman occupation.[197] It was one of the empire's Latin provinces; official epigraphs attest that the language of administration was Latin.[198] Historian estimates of the population of Roman Dacia range from 650,000 to 1,200,000.[199]

Dacians that remained outside the Roman Empire after the Dacian wars of AD 101–106 had been named Dakoi prosoroi (Latin Daci limitanei), "neighbouring Dacians".[25] Modern historians use the generic name "Free Dacians" or Independent Dacians.[200][128][127] The tribes Daci Magni (Great Dacians), Costoboci (generally considered a Dacian subtribe), and Carpi remained outside the Roman empire, in what the Romans called Dacia Libera (Free Dacia).[3] By the early third century the "Free Dacians" were a significantly troublesome group, by now identified as the Carpi.[200] Bichir argues that the Carpi were the most powerful of the Dacian tribes who had become the principal enemy of the Romans in the region.[201] In 214 AD, Caracalla campaigned against the Free Dacians.[202] There were also campaigns against the Dacians recorded in 236 AD.[203]

Roman Dacia was evacuated by the Romans under emperor Aurelian (ruled 271–5 AD). Aurelian made this decision on account of counter-pressures on the Empire there caused by the Carpi, Visigoths, Sarmatians, and Vandals; the lines of defence needed to be shortened, and Dacia was deemed not defensible given the demands on available resources. Roman power in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia. The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and the distance from Roman authority, encouraged the presence of local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanic tribes. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary fortresses to supplement the defence. Thracians in Moesia and Dacia were Romanized, while those within the Byzantine empire were their Hellenized descendants that had mingled with the Greeks.

Roman Dacia was never a uniformly or fully Romanized area. Post-Aurelianic Dacia fell into three divisions: the area along the river, usually under some type of Roman administration even if in a highly localized form; the zone beyond this area, from which Roman military personnel had withdrawn, leaving a sizable population behind that was generally Romanized; and finally what is now the northern parts of Moldavia, Crisana, and Maramures, which were never occupied by the Romans. These last areas were always peripheral to the Roman province, not militarily occupied but nonetheless influenced by Rome as part of the Roman economic sphere. Here lived the free, unoccupied Carpi, often called "Free Dacians".[172]

The Aurelian retreat was a purely military decision to withdraw the Roman troops to defend the Danube. The inhabitants of the old province of Dacia displayed no awareness of impending dissolution. There were no sudden flights or dismantling of property.[173] It is not possible to discern how many civilians followed the army out of Dacia; it is clear that there was no mass emigration, since there is evidence of continuity of settlement in Dacian villages and farms; the evacuation may not at first have been intended to be a permanent measure.[173] The Romans left the province, but they didn't consider that they lost it.[173] Dobrogea was not abandoned at all, but continued as part of the Roman Empire for over 350 years.[204] As late as AD 300, the tetrarchic emperors had resettled tens of thousands of Dacian Carpi inside the empire, dispersing them in communities the length of the Danube, from Austria to the Black Sea.[205]

Dacians were divided into two classes: the aristocracy (tarabostes) and the common people (comati). Only the aristocracy had the right to cover their heads, and wore a felt hat. The common people, who comprised the rank and file of the army, the peasants and artisans, might have been called capillati in Latin. Their appearance and clothing can be seen on Trajan's Column.

The chief occupations of the Dacians were agriculture, apiculture, viticulture, livestock, ceramics and metalworking. They also worked the gold and silver mines of Transylvania. At Pecica, Arad, a Dacian workshop was discovered, along with equipment for minting coins and evidence of bronze, silver, and iron-working that suggests a broad spectrum of smithing.[206] Evidence for the mass production of iron is found on many Dacian sites, indicating guild-like specialization.[206] Dacian ceramic manufacturing traditions continue from the pre-Roman to the Roman period, both in provincial and unoccupied Dacia, and well into the fourth and even early fifth centuries.[207] They engaged in considerable external trade, as is shown by the number of foreign coins found in the country (see also Decebalus Treasure). On the northernmost frontier of "free Dacia", coin circulation steadily grew in the first and second centuries, with a decline in the third and a rise again in the fourth century; the same pattern as observed for the Banat region to the southwest. What is remarkable is the extent and increase in coin circulation after Roman withdrawal from Dacia, and as far north as Transcarpathia.[208]

The first coins produced by the Geto-Dacians were imitations of silver coins of the Macedonian kings Philip II and Alexander the Great. Early in the 1st century BC, the Dacians replaced these with silver denarii of the Roman Republic, both official coins of Rome exported to Dacia, as well as locally made imitations of them. The Roman province Dacia is represented on the Roman sestertius coin as a woman seated on a rock, holding an aquila, a small child on her knee. The aquila holds ears of grain, and another small child is seated before her holding grapes.

Dacians had developed the murus dacicus (double-skinned ashlar-masonry with rubble fill and tie beams) characteristic to their complexes of fortified cities, like their capital Sarmizegetusa Regia in what is today Hunedoara County, Romania.[206] This type of wall has been discovered not only in the Dacian citadel of the Orastie mountains, but also in those at Covasna, Breaza near Făgăraș, Tilișca near Sibiu, Căpâlna in the Sebeș valley, Bănița not far from Petroșani, and Piatra Craivii to the north of Alba Iulia.[209] The degree of their urban development was displayed on Trajan's Column and in the account of how Sarmizegetusa Regia was defeated by the Romans. The Romans were given by treachery the locations of aqueducts and pipelines of the Dacian capital, only after destroying the water supply being able to end the long siege of Sarmisegetuza.

According to Romanian nationalist archaeology, the cradle of the Dacian culture is considered to be north of the Danube towards the Carpathian mountains, in the historical Romanian province of Muntenia. It is identified as an evolution of the Iron Age Basarabi culture. Such narrative believe that the earlier Iron Age Basarabi evidence in the northern lower Danube area connects to the iron-using Ferigile-Birsesti group. This is an archaeological manifestation of the historical Getae who, along with the Agathyrsae, are one of a number of tribal formations recorded by Herodotus.[165][210] In archaeology, "free Dacians" are attested by the Puchov culture (in which there are Celtic elements) and Lipiţa culture to the east of the Carpathians.[211] The Lipiţa culture has a Dacian/North Thracian origin.[212][213] This North Thracian population was dominated by strong Celtic influences, or had simply absorbed Celtic ethnic components.[214] Lipiţa culture has been linked to the Dacian tribe of Costoboci.[215][216]These standpoints are highly problematic, as there is no linear continuity between aforementioned cultures. in reality, the creation of the Dacian ethnos was foreshadowed by migratory movements from the lower Danube region following the collapse of the Celtic cultural circle c. 300 BC (The grave with a helmet from Ciumeşti – 50 years from its discovery. Comments on the greaves. 2. The Padea-Panagjurski kolonii group in Transylvania. Old and new discoveries)

Specific Dacian material culture includes: wheel-turned pottery that is generally plain but with distinctive elite wares, massive silver dress fibulae, precious metal plate, ashlar masonry, fortifications, upland sanctuaries with horseshoe-shaped precincts, and decorated clay heart altars at settlement sites. Among many discovered artifacts, the Dacian bracelets stand out, depicting their cultural and aesthetic sense.[206] There are difficulties correlating funerary monuments chronologically with Dacian settlements; a small number of burials are known, along with cremation pits, and isolated rich burials as at Cugir.[206] Dacian burial ritual continued under Roman occupation and into the post-Roman period.[217]

The Dacians are generally considered to have been Thracian speakers, representing a cultural continuity from earlier Iron Age communities.[86] Some historians and linguists consider Dacian language to be a dialect of or the same language as Thracian.[145][218] The vocalism and consonantism differentiate the Dacian and Thracian languages.[219] Others consider that Dacian and Illyrian form regional varieties (dialects) of a common language. (Thracians inhabited modern southern Bulgaria and northern Greece. Illyrians lived in modern Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia.)

The ancient languages of these people became extinct, and their cultural influence highly reduced, after the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Celts, Huns, Goths, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. Therefore, in the study of the toponomy of Dacia, one must take account of the fact that some place-names were taken by the Slavs from as yet unromanised Dacians.[220] A number of Dacian words are preserved in ancient sources, amounting to about 1150 anthroponyms and 900 toponyms, and in Discorides some of the rich plant lore of the Dacians is preserved along with the names of 42 medicinal plants.[16]

The Dacians knew about writing.[221][222][223] Permanent contacts with the Graeco-Roman world had brought the use of the Greek and later the Latin alphabet.[224] It is also certainly not the case that writing with Greek and Latin letters and knowledge of Greek and Latin were known in all the settlements scattered throughout Dacia, but there is no doubt about the existence of such knowledge in some circles of Dacian society.[225] However, the most revealing discoveries concerning the use of the writing by the Dacians occurred in the citadels on the Sebes mountains.[224] Some groups of letters from stone blocks at Sarmisegetuza might express personal names; these cannot now be read because the wall is ruined, and because it is impossible to restore the original order of the blocks in the wall.[226]

Dacian religion was considered by the classic sources as a key source of authority, suggesting to some that Dacia was a predominantly theocratic state led by priest-kings. However, the layout of the Dacian capital Sarmizegethusa indicates the possibility of co-rulership, with a separate high king and high priest.[158] Ancient sources recorded the names of several Dacian high priests (Deceneus, Comosicus and Vezina) and various orders of priests: "god-worshipers", "smoke-walkers" and "founders".[158] Both Hellenistic and Oriental influences are discernible in the religious background, alongside chthonic and solar motifs.[158]

According to Herodotus' account of the story of Zalmoxis or Zamolxis,[14] the Getae (speaking the same language as the Dacians and the Thracians, according to Strabo) believed in the immortality of the soul, and regarded death as merely a change of country. Their chief priest held a prominent position as the representative of the supreme deity, Zalmoxis, who is called also Gebeleizis by some among them.[14][229] Strabo wrote about the high priest of King Burebista Deceneus: "a man who not only had wandered through Egypt, but also had thoroughly learned certain prognostics through which he would pretend to tell the divine will; and within a short time he was set up as god (as I said when relating the story of Zamolxis)."[230]

The Goth Jordanes in his Getica (The origin and deeds of the Goths), also gives an account of Deceneus the highest priest, and considered Dacians a nation related to the Goths. Besides Zalmoxis, the Dacians believed in other deities, such as Gebeleizis, the god of storm and lightning, possibly related to the Thracian god Zibelthiurdos.[231] He was represented as a handsome man, sometimes with a beard. Later Gebeleizis was equated with Zalmoxis as the same god. According to Herodotus, Gebeleizis (*Zebeleizis/Gebeleizis who is only mentioned by Herodotus) is just another name of Zalmoxis.[232][14][233][234]

Another important deity was Bendis, goddess of the moon and the hunt.[235]By a decree of the oracle of Dodona, which required the Athenians to grant land for a shrine or temple, her cult was introduced into Attica by immigrant Thracian residents,[c] and, though Thracian and Athenian processions remained separate, both cult and festival became so popular that in Plato's time (c. 429–13 BC) its festivities were naturalised as an official ceremony of the Athenian city-state, called the Bendideia.[d]

Known Dacian theonyms include Zalmoxis, Gebeleïzis and Darzalas.[236][e] Gebeleizis is probably cognate to the Thracian god Zibelthiurdos (also Zbelsurdos, Zibelthurdos), wielder of lightning and thunderbolts. Derzelas (also Darzalas) was a chthonic god of health and human vitality. The pagan religion survived longer in Dacia than in other parts of the empire; Christianity made little headway until the fifth century.[173]

Fragments of pottery with different "inscriptions" with Latin and Greek letters incised before and after firing have been discovered in the settlement at Ocnita – Valcea.[237] An inscription carries the word Basileus (Βασιλεύς in Greek, meaning "king") and seems to have been written before the vessel was hardened by fire.[238] Other inscriptions contain the name of the king, believed to be Thiemarcus,[238] and Latin groups of letters (BVR, REB).[239] BVR indicates the name of the tribe or union of tribes, the Buridavensi Dacians who lived at Buridava and who were mentioned by Ptolemy in the second century AD under the name of Buridavensioi.[240]

The typical dress of Dacians, both men and women, can be seen on Trajan's column.[149]

Dio Chrysostom described the Dacians as natural philosophers.[241]

The history of Dacian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 2nd century AD in the region typically referred to by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Dacia. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Dacian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans. Apart from conflicts between Dacians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Dacian tribes as well.

The weapon most associated with the Dacian forces that fought against Trajan's army during his invasions of Dacia was the falx, a single-edged scythe-like weapon. The falx was able to inflict horrible wounds on opponents, easily disabling or killing the heavily armored Roman legionaries that they faced. This weapon, more so than any other single factor, forced the Roman army to adopt previously unused or modified equipment to suit the conditions on the Dacian battlefield.[242]

This is a list of several important Dacian individuals or those of partly Dacian origin.

Study of the Dacians, their culture, society and religion is not purely a subject of ancient history, but has present day implications in the context of Romanian nationalism. Positions taken on the vexed question of the origin of the Romanians and to what degree are present-day Romanians descended from the Dacians might have contemporary political implications. For example, the government of Nicolae Ceaușescu claimed an uninterrupted continuity of a Dacian-Romanian state, from King Burebista to Ceaușescu himself.[243] The Ceaușescu government conspicuously commemorated the supposed 2,050th anniversary of the founding of the "unified and centralized" country that was to become Romania, on which occasion the historical film Burebista was produced.

"The ducks come from the trucks." – A Romanian language pun about a mistranslation (duck and truck sound like dac and trac, the ethnonyms for Dacian and Thracian).[244]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)