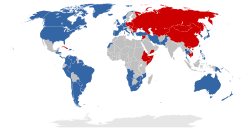

El Bloque del Este , también conocido como Bloque Comunista ( Combloc ), Bloque Socialista y Bloque Soviético , fue el término colectivo para una coalición no oficial de estados comunistas de Europa Central y Oriental , Asia , África y América Latina que estaban alineados con la Unión Soviética y existieron durante la Guerra Fría (1947-1991). Estos estados seguían la ideología del marxismo-leninismo , en oposición al bloque occidental capitalista . El Bloque del Este a menudo se denominaba " Segundo Mundo ", mientras que el término " Primer Mundo " se refería al Bloque Occidental y " Tercer Mundo " se refería a los países no alineados que se encontraban principalmente en África, Asia y América Latina, pero que también incluían notablemente a Yugoslavia, ex aliada soviética anterior a 1948 , que se encontraba en Europa.

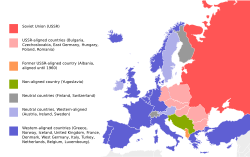

En Europa occidental , el término Bloque del Este generalmente se refería a la URSS y a los países de Europa central y oriental del Comecon ( Alemania del Este , Polonia , Checoslovaquia , Hungría , Rumania , Bulgaria y Albania ). [a] En Asia , el Bloque del Este comprendía a Mongolia , Vietnam , Laos , Kampuchea , Corea del Norte , Yemen del Sur , Siria y China . [b] [c] En América , los países alineados con la Unión Soviética incluían a Cuba desde 1961 y por períodos limitados a Nicaragua y Granada . [1]

El término Bloque del Este se utilizaba a menudo indistintamente con el término Segundo Mundo . Este uso más amplio del término incluiría no sólo a la China maoísta y Camboya , sino también a los satélites soviéticos de corta duración como la Segunda República del Turkestán Oriental (1944-1949), la República Popular de Azerbaiyán (1945-1946) y la República de Mahabad (1946), así como los estados marxistas-leninistas a caballo entre el Segundo y el Tercer Mundo antes del final de la Guerra Fría: la República Democrática Popular del Yemen (desde 1967), la República Popular del Congo (desde 1969), la República Popular de Benín , la República Popular de Angola y la República Popular de Mozambique desde 1975, el Gobierno Revolucionario Popular de Granada de 1979 a 1983, el Derg / República Democrática Popular de Etiopía desde 1974, y la República Democrática Somalí desde 1969 hasta la Guerra de Ogadén en 1977. [2] [3] [4] [5] Aunque no eran marxistas-leninistas , los líderes del partido Baazista Siria consideraban oficialmente al país como parte del Bloque Socialista y establecieron una estrecha alianza económica y militar con la Unión Soviética. [6] [7]

Muchos estados fueron acusados por el Bloque Occidental de pertenecer al Bloque Oriental cuando formaban parte del Movimiento de Países No Alineados . La definición más limitada del Bloque Oriental sólo incluiría a los estados del Pacto de Varsovia y a la República Popular de Mongolia como antiguos estados satélites dominados en su mayoría por la Unión Soviética. El desafío de Cuba al control soviético completo fue lo suficientemente notable como para que a veces se excluyera a Cuba como estado satélite por completo, ya que a veces intervino en otros países del Tercer Mundo incluso cuando la Unión Soviética se oponía a ello. [1]

El uso del término "Bloque del Este" después de 1991 puede ser más limitado para referirse a los estados que formaron el Pacto de Varsovia (1955-1991) y Mongolia (1924-1991), que ya no son estados comunistas. [8] [9] A veces se los menciona de manera más general como "los países de Europa del Este bajo el comunismo", [10] excluyendo a Mongolia, pero incluyendo a Yugoslavia y Albania , que se habían separado de la Unión Soviética en la década de 1960. [11]

Aunque Yugoslavia era un país socialista, no era miembro del Comecon ni del Pacto de Varsovia. Al separarse de la URSS en 1948, Yugoslavia no pertenecía al Este, pero tampoco pertenecía al Oeste debido a su sistema socialista y su condición de miembro fundador del Movimiento de Países No Alineados . [12] Sin embargo, algunas fuentes consideran que Yugoslavia es miembro del Bloque del Este. [11] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] Otros consideran que Yugoslavia no es miembro después de que rompió con la política soviética en la ruptura de Tito-Stalin de 1948. [20] [21] [12]

En 1922, la RSFS de Rusia , la RSS de Ucrania , la RSS de Bielorrusia y la RSFS de Transcaucasia aprobaron el Tratado de Creación de la URSS y la Declaración de Creación de la URSS, formando la Unión Soviética . [25] El líder soviético Joseph Stalin , que veía a la Unión Soviética como una "isla socialista", declaró que la Unión Soviética debía ver que "el actual cerco capitalista sea reemplazado por un cerco socialista". [26]

En 1939, la URSS firmó el Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop con la Alemania nazi [27] que contenía un protocolo secreto que dividía a Rumania, Polonia, Letonia, Lituania, Estonia y Finlandia en esferas de influencia alemana y soviética. [27] [28] Polonia oriental, Letonia, Estonia, Finlandia y Besarabia en el norte de Rumania fueron reconocidas como partes de la esfera de influencia soviética . [28] Lituania fue agregada en un segundo protocolo secreto en septiembre de 1939. [29]

La Unión Soviética había invadido las partes del este de Polonia que le habían sido asignadas por el Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop dos semanas después de la invasión alemana del oeste de Polonia, seguida de una coordinación con las fuerzas alemanas en Polonia. [30] [31] Durante la ocupación de Polonia oriental por la Unión Soviética , los soviéticos liquidaron el estado polaco y una reunión germano-soviética abordó la futura estructura de la "región polaca". [32] Las autoridades soviéticas inmediatamente comenzaron una campaña de sovietización [33] [34] de las áreas recientemente anexadas por los soviéticos . [35] [36] [37] Las autoridades soviéticas colectivizaron la agricultura [38] y nacionalizaron y redistribuyeron la propiedad privada y estatal polaca. [39] [40] [41]

Las ocupaciones soviéticas iniciales de los países bálticos ocurrieron a mediados de junio de 1940, cuando las tropas soviéticas de la NKVD atacaron los puestos fronterizos en Lituania , Estonia y Letonia , [42] [43] seguidas de la liquidación de las administraciones estatales y su reemplazo por cuadros soviéticos. [42] [44] Las elecciones para el parlamento y otros cargos se llevaron a cabo con candidatos únicos listados y los resultados oficiales fueron inventados, pretendiendo la aprobación de los candidatos prosoviéticos por el 92,8 por ciento de los votantes en Estonia, el 97,6 por ciento en Letonia y el 99,2 por ciento en Lituania. [45] [46] Las "asambleas populares" instaladas fraudulentamente declararon inmediatamente a cada uno de los tres países correspondientes como "Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas" y solicitaron su "admisión en la Unión Soviética de Stalin ". Esto resultó formalmente en la anexión de Lituania, Letonia y Estonia por parte de la Unión Soviética en agosto de 1940. [45] La comunidad internacional condenó esta anexión de los tres países bálticos y la consideró ilegal. [47] [48]

En 1939, la Unión Soviética intentó sin éxito una invasión de Finlandia , [49] tras lo cual las partes firmaron un tratado de paz provisional que otorgaba a la Unión Soviética la región oriental de Carelia (10% del territorio finlandés), [49] y se estableció la República Socialista Soviética Karelo-Finlandesa fusionando los territorios cedidos con la KASSR . Después de un ultimátum soviético de junio de 1940 que exigía Besarabia, Bucovina y la región de Hertsa a Rumania, [50] [51] los soviéticos entraron en estas áreas, Rumania cedió a las demandas soviéticas y los soviéticos ocuparon los territorios . [50] [52]

_(B&W).jpg/440px-Yalta_Conference_(Churchill,_Roosevelt,_Stalin)_(B&W).jpg)

En junio de 1941, Alemania rompió el pacto Molotov-Ribbentrop al invadir la Unión Soviética . Desde el momento de esta invasión hasta 1944, las áreas anexadas por la Unión Soviética formaron parte del Ostland de Alemania (a excepción de la República Socialista Soviética de Moldavia ). A partir de entonces, la Unión Soviética comenzó a empujar a las fuerzas alemanas hacia el oeste a través de una serie de batallas en el Frente Oriental .

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, en la frontera soviético-finlandesa , las partes firmaron otro tratado de paz cediendo territorio a la Unión Soviética en 1944, seguido de una anexión soviética de aproximadamente los mismos territorios finlandeses orientales que los del tratado de paz provisional anterior como parte de la República Socialista Soviética de Karelo-Finlandia . [53]

Entre 1943 y 1945 se celebraron varias conferencias sobre la Europa de posguerra que, en parte, abordaron la posible anexión y control soviético de países de Europa central. Existían varios planes aliados para el orden estatal en Europa central para la posguerra. Mientras que Joseph Stalin intentó poner el mayor número posible de estados bajo control soviético, el primer ministro británico Winston Churchill prefería una Confederación del Danubio de Europa central para contrarrestar a estos países contra Alemania y Rusia. [54] La política soviética de Churchill con respecto a Europa central difería enormemente de la del presidente estadounidense Franklin D. Roosevelt , ya que el primero creía que el líder soviético Stalin era un tirano parecido al "diablo" que lideraba un sistema vil. [55]

Cuando se le advirtió de una posible dominación por parte de una dictadura de Stalin sobre parte de Europa, Roosevelt respondió con una declaración que resumía su razonamiento para las relaciones con Stalin: "Tengo el presentimiento de que Stalin no es ese tipo de hombre... Creo que si le doy todo lo que pueda y no le pido nada a cambio, noblesse oblige, no intentará anexionarse nada y trabajará conmigo por un mundo de democracia y paz". [56] Durante una reunión con Stalin y Roosevelt en Teherán en 1943, Churchill declaró que Gran Bretaña estaba vitalmente interesada en restaurar a Polonia como un país políticamente independiente. [57] Gran Bretaña no presionó en el asunto por temor a que se convirtiera en una fuente de fricción entre los aliados. [57]

En febrero de 1945, en la conferencia de Yalta , Stalin exigió una esfera soviética de influencia política en Europa Central. [58] Finalmente, Churchill y Roosevelt convencieron a Stalin de no desmembrar Alemania. [58] Stalin declaró que la Unión Soviética mantendría el territorio del este de Polonia que ya había tomado mediante una invasión en 1939 con algunas excepciones , y quería un gobierno polaco prosoviético en el poder en lo que quedaría de Polonia. [58] Después de la resistencia de Churchill y Roosevelt, Stalin prometió una reorganización del actual gobierno prosoviético sobre una base democrática más amplia en Polonia. [58] Afirmó que la principal tarea del nuevo gobierno sería preparar elecciones. [59] Sin embargo, el referéndum popular polaco de 1946 (conocido como el referéndum "Tres veces Sí") y las posteriores elecciones parlamentarias polacas de 1947 no cumplieron con los estándares democráticos y fueron en gran medida manipuladas. [60]

Las partes en Yalta acordaron además que se permitiría a los países de la Europa liberada y a los antiguos satélites del Eje "crear instituciones democráticas de su propia elección", de conformidad con "el derecho de todos los pueblos a elegir la forma de gobierno bajo la cual vivirán". [61] Las partes también acordaron ayudar a esos países a formar gobiernos provisionales "que se comprometerían a establecerse lo antes posible mediante elecciones libres" y "facilitar, cuando fuera necesario, la celebración de esas elecciones". [61]

A principios de la Conferencia de Potsdam de julio-agosto de 1945 , tras la rendición incondicional de Alemania, Stalin repitió las promesas previas que había hecho a Churchill de que se abstendría de una " sovietización " de Europa Central. [62] Además de las reparaciones, Stalin presionó por un "botín de guerra", que permitiría a la Unión Soviética apoderarse directamente de la propiedad de las naciones conquistadas sin limitaciones cuantitativas o cualitativas. [63] Se añadió una cláusula que permitía que esto ocurriera con algunas limitaciones. [63]

Al principio, los soviéticos ocultaron su papel en otras políticas del bloque del Este, y la transformación apareció como una modificación de la " democracia burguesa " occidental. [64] Como le dijeron a un joven comunista en Alemania del Este, "tiene que parecer democrático, pero debemos tener todo bajo nuestro control". [65] Stalin sintió que la transformación socioeconómica era indispensable para establecer el control soviético, lo que reflejaba la visión marxista-leninista de que las bases materiales, la distribución de los medios de producción, moldeaban las relaciones sociales y políticas. [66] La Unión Soviética también cooptó a los países de Europa del Este en su esfera de influencia haciendo referencia a algunas similitudes culturales. [67]

Los cuadros formados en Moscú fueron colocados en puestos de poder cruciales para cumplir órdenes relativas a la transformación sociopolítica. [66] La eliminación del poder social y financiero de la burguesía mediante la expropiación de la propiedad industrial y territorial recibió prioridad absoluta. [64] Estas medidas fueron publicitadas como "reformas" en lugar de transformaciones socioeconómicas. [64] Salvo inicialmente en Checoslovaquia, las actividades de los partidos políticos tenían que adherirse a la "política de bloques", y los partidos finalmente tuvieron que aceptar la membresía en un "bloque antifascista" que los obligaba a actuar sólo por "consenso" mutuo. [68] El sistema de bloques permitió a la Unión Soviética ejercer el control interno indirectamente. [69]

Los departamentos cruciales, como los responsables del personal, la policía general, la policía secreta y la juventud, estaban estrictamente dirigidos por los comunistas. [69] Los cuadros de Moscú diferenciaban a las "fuerzas progresistas" de los "elementos reaccionarios" y dejaban a ambos sin poder. Tales procedimientos se repitieron hasta que los comunistas consiguieron un poder ilimitado y sólo quedaron los políticos que apoyaban incondicionalmente la política soviética. [70]

En junio de 1947, después de que los soviéticos se negaran a negociar una posible flexibilización de las restricciones al desarrollo alemán, Estados Unidos anunció el Plan Marshall , un programa integral de asistencia estadounidense a todos los países europeos que quisieran participar, incluida la Unión Soviética y los de Europa del Este. [71] Los soviéticos rechazaron el Plan y adoptaron una posición de línea dura contra los Estados Unidos y las naciones europeas no comunistas. [72] Sin embargo, Checoslovaquia estaba ansiosa por aceptar la ayuda estadounidense; el gobierno polaco tenía una actitud similar, y esto fue de gran preocupación para los soviéticos. [73]

En una de las señales más claras del control soviético sobre la región hasta ese momento, el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores checoslovaco, Jan Masaryk , fue convocado a Moscú y reprendido por Stalin por considerar unirse al Plan Marshall. El primer ministro polaco, Józef Cyrankiewicz, fue recompensado por el rechazo polaco al Plan con un enorme acuerdo comercial de cinco años, que incluía 450 millones de dólares en créditos, 200.000 toneladas de grano, maquinaria pesada y fábricas. [74]

En julio de 1947, Stalin ordenó a estos países que se retiraran de la Conferencia de París sobre el Programa de Recuperación Europea, que se ha descrito como "el momento de la verdad" en la división de Europa posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [75] A partir de entonces, Stalin buscó un control más fuerte sobre otros países del Bloque del Este, abandonando la apariencia previa de instituciones democráticas. [76] Cuando pareció que, a pesar de la fuerte presión, los partidos no comunistas podrían recibir más del 40% de los votos en las elecciones húngaras de agosto de 1947 , se instituyeron represiones para liquidar cualquier fuerza política independiente. [76]

Ese mismo mes, comenzó la aniquilación de la oposición en Bulgaria sobre la base de las continuas instrucciones de los cuadros soviéticos. [76] [77] En una reunión de todos los partidos comunistas a finales de septiembre de 1947 en Szklarska Poręba , [78] los partidos comunistas del Bloque del Este fueron culpados por permitir incluso una influencia menor de los no comunistas en sus respectivos países durante el período previo al Plan Marshall. [76]

En la antigua capital alemana, Berlín, rodeada por la Alemania ocupada por los soviéticos, Stalin instituyó el Bloqueo de Berlín el 24 de junio de 1948, impidiendo que alimentos, materiales y suministros llegaran a Berlín Occidental . [79] El bloqueo fue causado, en parte, por las elecciones locales anticipadas de octubre de 1946 en las que el Partido Socialista Unificado de Alemania (SED) fue rechazado en favor del Partido Socialdemócrata, que había obtenido dos veces y media más votos que el SED. [80] Estados Unidos, Gran Bretaña, Francia, Canadá, Australia, Nueva Zelanda y varios otros países comenzaron un masivo "puente aéreo de Berlín", abasteciendo a Berlín Occidental con alimentos y otros suministros. [81]

Los soviéticos lanzaron una campaña de relaciones públicas contra el cambio de política occidental y los comunistas intentaron perturbar las elecciones de 1948, lo que provocó grandes pérdidas en ellas, [82] mientras 300.000 berlineses se manifestaban e instaron a que continuara el puente aéreo internacional. [83] En mayo de 1949, Stalin levantó el bloqueo, permitiendo la reanudación de los envíos occidentales a Berlín. [84] [85]

Después de los desacuerdos entre el líder yugoslavo Josip Broz Tito y la Unión Soviética con respecto a Grecia y Albania , se produjo una ruptura entre Tito y Stalin , seguida por la expulsión de Yugoslavia del Cominform en junio de 1948 y un breve y fallido golpe de Estado soviético en Belgrado. [86] La división creó dos fuerzas comunistas separadas en Europa. [86] Inmediatamente se inició una vehemente campaña contra el titoísmo en el Bloque del Este, describiendo a los agentes tanto de Occidente como de Tito en todos los lugares como participantes en actividades subversivas. [86]

Stalin ordenó convertir el Cominform en un instrumento para monitorear y controlar los asuntos internos de otros partidos del Bloque del Este. [86] También consideró brevemente convertir el Cominform en un instrumento para sentenciar a los desviadores de alto rango, pero descartó la idea por considerarla poco práctica. [86] En cambio, se inició una iniciativa para debilitar a los líderes del partido comunista a través del conflicto. [86] Los cuadros soviéticos en puestos del partido comunista y del estado en el Bloque recibieron instrucciones de fomentar el conflicto dentro de la dirigencia y de transmitir información unos contra otros. [86] Esto acompañó un flujo continuo de acusaciones de "desviaciones nacionalistas", "apreciación insuficiente del papel de la URSS", vínculos con Tito y "espionaje para Yugoslavia". [87] Esto resultó en la persecución de muchos cuadros importantes del partido, incluidos los de Alemania del Este. [87]

El primer país en experimentar este enfoque fue Albania , donde el líder Enver Hoxha inmediatamente cambió de rumbo de favorecer a Yugoslavia a oponerse a ella. [87] En Polonia , el líder Władysław Gomułka , que previamente había hecho declaraciones pro-yugoslavas, fue depuesto como secretario general del partido a principios de septiembre de 1948 y posteriormente encarcelado. [87] En Bulgaria , cuando pareció que Traicho Kostov, que no era un cuadro de Moscú, era el siguiente en la línea de liderazgo, en junio de 1949, Stalin ordenó el arresto de Kostov, seguido poco después por una sentencia de muerte y ejecución. [87] Varios otros funcionarios búlgaros de alto rango también fueron encarcelados. [87] Stalin y el líder húngaro Mátyás Rákosi se reunieron en Moscú para orquestar un juicio espectáculo del oponente de Rákosi László Rajk , quien luego fue ejecutado. [88] La preservación del bloque soviético dependía del mantenimiento de un sentido de unidad ideológica que afianzara la influencia de Moscú en Europa del Este, así como el poder de las élites comunistas locales. [89]

La ciudad portuaria de Trieste fue objeto de especial atención después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Hasta la ruptura entre Tito y Stalin, las potencias occidentales y el bloque oriental se enfrentaron sin concesiones. El estado tapón neutral Territorio Libre de Trieste , fundado en 1947 con la ayuda de las Naciones Unidas, se dividió y disolvió en 1954 y 1975, también a causa de la distensión entre Occidente y Tito. [90] [91]

A pesar del diseño institucional inicial del comunismo implementado por Joseph Stalin en el Bloque del Este, el desarrollo posterior varió entre países. [92] En los estados satélite, después de que se concluyeron inicialmente los tratados de paz, la oposición fue esencialmente liquidada, se impusieron pasos fundamentales hacia el socialismo y los líderes del Kremlin buscaron fortalecer el control allí. [93] Desde el principio, Stalin dirigió sistemas que rechazaban las características institucionales occidentales de las economías de mercado , la democracia parlamentaria capitalista (denominada "democracia burguesa" en el lenguaje soviético) y el estado de derecho que sometía la intervención discrecional del estado. [94] Los estados resultantes aspiraban al control total de un centro político respaldado por un aparato represivo extenso y activo, y un papel central de la ideología marxista-leninista . [94]

Sin embargo, los vestigios de las instituciones democráticas nunca fueron destruidos por completo, lo que dio como resultado la fachada de instituciones de estilo occidental, como los parlamentos, que en realidad solo aprobaban automáticamente las decisiones tomadas por los gobernantes, y las constituciones, a las cuales la adhesión de las autoridades era limitada o inexistente. [94] Los parlamentos todavía eran elegidos, pero sus reuniones se realizaban solo unos pocos días al año, solo para legitimar las decisiones del politburó, y se les prestaba tan poca atención que algunos de los que servían estaban realmente muertos, y los funcionarios declaraban abiertamente que sentarían a los miembros que habían perdido las elecciones. [95]

El primer secretario o secretario general del comité central de cada partido comunista era la figura más poderosa de cada régimen. [96] El partido sobre el que el politburó tenía influencia no era un partido de masas sino, conforme a la tradición leninista , un partido selectivo más pequeño de entre el tres y el catorce por ciento de la población del país que había aceptado la obediencia total. [97] Aquellos que consiguieron ser miembros de este grupo selectivo recibieron recompensas considerables, como el acceso a tiendas especiales de precios más bajos con una mayor selección de productos nacionales y/o extranjeros de alta calidad ( dulces , alcohol , cigarros , cámaras , televisores y similares), escuelas especiales, instalaciones de vacaciones, casas, muebles nacionales y/o extranjeros de alta calidad, obras de arte, pensiones, permiso para viajar al extranjero y automóviles oficiales con matrículas distintivas para que la policía y otros pudieran identificar a estos miembros a distancia. [97]

Además de las restricciones a la emigración, a la sociedad civil, definida como un dominio de acción política fuera del control estatal del partido, no se le permitió arraigarse firmemente, con la posible excepción de Polonia en la década de 1980. [ 98] Si bien el diseño institucional de los sistemas comunistas se basó en el rechazo del estado de derecho, la infraestructura legal no fue inmune al cambio que reflejaba la ideología en decadencia y la sustitución de la ley autónoma. [98] Inicialmente, los partidos comunistas eran pequeños en todos los países excepto Checoslovaquia, de modo que existía una grave escasez de personas políticamente "confiables" para la administración, la policía y otras profesiones. [99] Por lo tanto, los no comunistas "políticamente poco confiables" inicialmente tuvieron que cubrir tales roles. [99] Aquellos que no obedecían a las autoridades comunistas fueron expulsados, mientras que los cuadros de Moscú comenzaron programas de partido a gran escala para capacitar al personal que cumpliría con los requisitos políticos. [99] Los antiguos miembros de la clase media fueron discriminados oficialmente, aunque la necesidad que tenía el Estado de sus habilidades y ciertas oportunidades para reinventarse como buenos ciudadanos comunistas permitió que muchos de ellos lograran el éxito. [100]

Los regímenes comunistas del bloque del Este consideraban a los grupos marginales de intelectuales de la oposición como una amenaza potencial debido a las bases que sustentaban el poder comunista en ellos. [101] La supresión de la disidencia y la oposición se consideraba un requisito fundamental para conservar el poder, aunque el enorme gasto con el que se mantenía a la población de ciertos países bajo vigilancia secreta puede no haber sido racional. [101] Tras una fase inicial totalitaria, un período postotalitario siguió a la muerte de Stalin en el que el método principal de gobierno comunista pasó del terror de masas a la represión selectiva, junto con estrategias ideológicas y sociopolíticas de legitimación y de obtención de lealtad. [102] Los jurados fueron reemplazados por un tribunal de jueces profesionales y dos asesores legos que eran actores confiables del partido. [103]

La policía disuadía y contenía a la oposición a las directivas del partido. [103] La policía política era el núcleo del sistema, y sus nombres se convirtieron en sinónimo de poder puro y amenaza de represalias violentas si un individuo actuaba contra el Estado. [103] Varias organizaciones de policía estatal y policía secreta aplicaban el gobierno del partido comunista, entre ellas las siguientes:

La prensa en el período comunista era un órgano del Estado, completamente dependiente y subordinado al partido comunista. [104] Antes de finales de los años 1980, las organizaciones de radio y televisión del Bloque del Este eran propiedad del Estado, mientras que los medios impresos eran generalmente propiedad de organizaciones políticas, en su mayoría del partido comunista local. [105] Los periódicos y revistas juveniles eran propiedad de organizaciones juveniles afiliadas a partidos comunistas. [105]

El control de los medios de comunicación era ejercido directamente por el propio partido comunista y por la censura estatal, que también estaba controlada por el partido. [105] Los medios de comunicación servían como una forma importante de control sobre la información y la sociedad. [106] Las autoridades consideraban que la difusión y la representación del conocimiento eran vitales para la supervivencia del comunismo, ya que sofocaban los conceptos alternativos y las críticas. [106] Se publicaron varios periódicos estatales del Partido Comunista, entre ellos:

La Agencia Telegráfica de la Unión Soviética (TASS) sirvió como agencia central para la recopilación y distribución de noticias internas e internacionales para todos los periódicos, estaciones de radio y televisión soviéticas. Con frecuencia fue infiltrada por agencias de inteligencia y seguridad soviéticas, como la NKVD y el GRU . La TASS tenía filiales en 14 repúblicas soviéticas, incluidas la RSS de Lituania , la RSS de Letonia , la RSS de Estonia , la RSS de Moldavia , la RSS de Ucrania y la RSS de Bielorrusia .

Los países occidentales invirtieron fuertemente en transmisores potentes que permitieron que servicios como la BBC , VOA y Radio Free Europe (RFE) se escucharan en el Bloque del Este, a pesar de los intentos de las autoridades de bloquear las vías aéreas.

Bajo el ateísmo estatal de muchas naciones del Bloque del Este, la religión fue activamente reprimida. [107] Dado que algunos de estos estados vincularon su herencia étnica a sus iglesias nacionales, tanto los pueblos como sus iglesias fueron blanco de los soviéticos. [108] [109]

En 1949, la Unión Soviética , Bulgaria, Checoslovaquia , Hungría, Polonia y Rumania fundaron el Comecon de acuerdo con el deseo de Stalin de imponer la dominación soviética de los estados menores de Europa Central y apaciguar a algunos estados que habían expresado interés en el Plan Marshall , [110] [111] y que ahora estaban, cada vez más, aislados de sus mercados y proveedores tradicionales en Europa Occidental. [75] El papel del Comecon se volvió ambiguo porque Stalin prefería vínculos más directos con otros jefes del partido que la sofisticación indirecta del Comecon; no jugó un papel significativo en la década de 1950 en la planificación económica. [112] Inicialmente, el Comecon sirvió como cobertura para la toma soviética de materiales y equipos del resto del Bloque del Este, pero el equilibrio cambió cuando los soviéticos se convirtieron en subsidiarios netos del resto del Bloque en la década de 1970 a través de un intercambio de materias primas de bajo costo a cambio de productos terminados de mala calidad. [113]

En 1955, se formó el Pacto de Varsovia en parte como respuesta a la inclusión de Alemania Occidental en la OTAN y en parte porque los soviéticos necesitaban una excusa para retener unidades del Ejército Rojo en Hungría. [111] Durante 35 años, el Pacto perpetuó el concepto estalinista de seguridad nacional soviética basada en la expansión imperial y el control sobre regímenes satélites en Europa del Este. [114] Esta formalización soviética de sus relaciones de seguridad en el Bloque del Este reflejó el principio básico de política de seguridad de Moscú de que la presencia continua en Europa Central y Oriental era una base de su defensa contra Occidente. [114] A través de sus estructuras institucionales, el Pacto también compensó en parte la ausencia del liderazgo personal de Joseph Stalin desde su muerte en 1953. [114] El Pacto consolidó los ejércitos de los otros miembros del Bloque en los que los oficiales y agentes de seguridad soviéticos sirvieron bajo una estructura de mando soviética unificada. [115]

A partir de 1964, Rumania adoptó un rumbo más independiente. [116] Si bien no repudió ni el Comecon ni el Pacto de Varsovia, dejó de desempeñar un papel significativo en ninguno de ellos. [116] La asunción del liderazgo de Nicolae Ceaușescu un año después empujó a Rumania aún más en la dirección de la separatismo. [116] Albania, que se había vuelto cada vez más aislada bajo el liderazgo estalinista Enver Hoxha después de la desestalinización , y sufrió una división albano-soviética en 1961, se retiró del Pacto de Varsovia en 1968 [117] después de la invasión del Pacto de Varsovia a Checoslovaquia . [118]

En 1917, Rusia restringió la emigración al instituir controles de pasaportes y prohibir la salida de nacionales beligerantes. [119] En 1922, después del Tratado sobre la Creación de la URSS , tanto la RSS de Ucrania como la RSFS de Rusia emitieron reglas generales para los viajes que prohibían virtualmente todas las salidas, haciendo imposible la emigración legal. [120] Los controles fronterizos se reforzaron posteriormente de tal manera que, en 1928, incluso la salida ilegal era efectivamente imposible. [120] Esto más tarde incluyó controles de pasaportes internos , que cuando se combinaron con permisos individuales de Propiska ("lugar de residencia") de la ciudad y restricciones internas de libertad de movimiento a menudo llamadas el kilómetro 101 , restringieron en gran medida la movilidad incluso dentro de pequeñas áreas de la Unión Soviética. [121]

Después de la creación del Bloque Oriental, la emigración desde los países recientemente ocupados, excepto en circunstancias limitadas, se detuvo efectivamente a principios de la década de 1950, y el enfoque soviético para controlar el movimiento nacional fue emulado por la mayor parte del resto del Bloque Oriental. [122] Sin embargo, en Alemania del Este , aprovechando la frontera interior alemana entre las zonas ocupadas, cientos de miles huyeron a Alemania Occidental, con cifras totales de 197.000 en 1950, 165.000 en 1951, 182.000 en 1952 y 331.000 en 1953. [123] [124] Una razón para el marcado aumento de 1953 fue el miedo a una posible mayor sovietización con las acciones cada vez más paranoicas [ dudosas – discutir ] de Joseph Stalin a finales de 1952 y principios de 1953. [125] 226.000 habían huido sólo en los primeros seis meses de 1953. [126]

Con el cierre oficial de la frontera interior alemana en 1952, [127] las fronteras del sector de la ciudad de Berlín siguieron siendo considerablemente más accesibles que el resto de la frontera debido a su administración por las cuatro potencias ocupantes. [128] En consecuencia, comprendía efectivamente un "vacío legal" a través del cual los ciudadanos del Bloque del Este todavía podían moverse hacia el oeste. [127] Los 3,5 millones de alemanes orientales que se habían ido en 1961, llamados Republikflucht , totalizaban aproximadamente el 20% de toda la población de Alemania Oriental. [129] En agosto de 1961, Alemania Oriental erigió una barrera de alambre de púas que eventualmente se expandiría a través de la construcción hasta el Muro de Berlín , cerrando efectivamente el vacío legal. [130]

Con una emigración convencional prácticamente inexistente, más del 75% de los que emigraron de los países del Bloque del Este entre 1950 y 1990 lo hicieron en virtud de acuerdos bilaterales de "migración étnica". [131] Alrededor del 10% eran migrantes refugiados en virtud de la Convención de Ginebra de 1951. [131] La mayoría de los soviéticos a los que se les permitió salir durante este período de tiempo eran judíos étnicos a los que se les permitió emigrar a Israel después de que una serie de deserciones embarazosas en 1970 hicieran que los soviéticos abrieran emigraciones étnicas muy limitadas. [132] La caída de la Cortina de Hierro estuvo acompañada por un aumento masivo de la migración europea de Este a Oeste. [131] Entre los desertores famosos del Bloque del Este se encontraba la hija de Joseph Stalin , Svetlana Alliluyeva , quien denunció a Stalin después de su deserción en 1967. [133]

Los países del bloque del Este, como la Unión Soviética, tuvieron altas tasas de crecimiento demográfico. En 1917, la población de Rusia en sus fronteras actuales era de 91 millones. A pesar de la destrucción en la Guerra Civil Rusa , la población creció a 92,7 millones en 1926. En 1939, la población aumentó un 17 por ciento a 108 millones. A pesar de más de 20 millones de muertes sufridas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la población de Rusia creció a 117,2 millones en 1959. El censo soviético de 1989 mostró que la población de Rusia era de 147 millones de personas. [134]

El sistema económico y político soviético produjo otras consecuencias, como por ejemplo en los estados bálticos , donde la población era aproximadamente la mitad de lo que debería haber sido en comparación con países similares como Dinamarca, Finlandia y Noruega durante los años 1939-1990. La mala vivienda fue un factor que condujo a una grave disminución de las tasas de natalidad en todo el bloque del Este. [135] Sin embargo, las tasas de natalidad seguían siendo más altas que en los países de Europa occidental. La dependencia del aborto, en parte porque la escasez periódica de píldoras anticonceptivas y dispositivos intrauterinos hacía que estos sistemas no fueran fiables, [136] también deprimió la tasa de natalidad y forzó un cambio hacia políticas pronatalistas a finales de los años 1960, incluidos severos controles al aborto y exhortaciones propagandísticas como la distinción de "madre heroína" otorgada a las mujeres rumanas que tenían diez o más hijos. [137]

En octubre de 1966, se prohibió la anticoncepción artificial en Rumania y se exigieron pruebas de embarazo periódicas para las mujeres en edad fértil, con severas sanciones para cualquiera que hubiera interrumpido un embarazo. [138] A pesar de esas restricciones, las tasas de natalidad siguieron siendo bajas, en parte debido a los abortos inducidos por personas no calificadas. [137] Las poblaciones de los países del Bloque del Este eran las siguientes: [139] [140]

Las sociedades del bloque del Este funcionaban según principios antimeritocráticos con fuertes elementos igualitarios. Por ejemplo, Checoslovaquia favorecía a los individuos menos cualificados, además de conceder privilegios a la nomenclatura y a quienes tenían la clase o los antecedentes políticos adecuados. Las sociedades del bloque del Este estaban dominadas por el partido comunista gobernante, al que Pavel Machonin denominó "partidocracia". [141] Los antiguos miembros de la clase media eran oficialmente discriminados, aunque la necesidad de sus habilidades les permitió reinventarse como buenos ciudadanos comunistas. [100] [142]

En todo el bloque del Este existía una escasez de viviendas. En Europa se debió principalmente a la devastación causada por la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Los esfuerzos de construcción se vieron afectados tras un severo recorte de los recursos estatales disponibles para la vivienda a partir de 1975. [143] Las ciudades se llenaron de grandes bloques de apartamentos construidos en serie . [144] La política de construcción de viviendas adolecía de considerables problemas organizativos. [145] Además, las casas terminadas tenían acabados de calidad notablemente deficiente. [145]

El énfasis casi total en los grandes bloques de apartamentos fue una característica común de las ciudades del Bloque del Este en los años 1970 y 1980. [146] Las autoridades de Alemania del Este vieron grandes ventajas de costo en la construcción de bloques de apartamentos Plattenbau , de modo que la construcción de dicha arquitectura en el borde de las grandes ciudades continuó hasta la disolución del Bloque del Este. [146] Edificios como los Paneláks de Checoslovaquia y los Panelház de Hungría . Deseando reforzar el papel del Estado en los años 1970 y 1980, Nicolae Ceaușescu promulgó el programa de sistematización , que consistía en la demolición y reconstrucción de aldeas, pueblos, ciudades y pueblos existentes, en su totalidad o en parte, para dar lugar a bloques de apartamentos estandarizados en todo el país ( blocuri ). [146] Bajo esta ideología, Ceaușescu construyó en los años 1980 el Centro Cívico de Bucarest, que alberga el Palacio del Parlamento , en el lugar del antiguo centro histórico.

Incluso a finales de los años 1980, las condiciones sanitarias en la mayoría de los países del bloque del Este estaban lejos de ser adecuadas. [147] En todos los países para los que existían datos, el 60% de las viviendas tenían una densidad de más de una persona por habitación entre 1966 y 1975. [147] El promedio en los países occidentales para los que se disponía de datos se aproximaba a 0,5 personas por habitación. [147] Los problemas se agravaban por los acabados de mala calidad en las viviendas nuevas, que a menudo obligaban a los ocupantes a someterse a una cierta cantidad de trabajos de acabado y reparaciones adicionales. [147]

EspañolLa escasez cada vez mayor de las décadas de 1970 y 1980 se produjo durante un aumento de la cantidad de viviendas en relación con la población entre 1970 y 1986. [150] Incluso en el caso de las viviendas nuevas, el tamaño medio de las mismas era de sólo 61,3 metros cuadrados (660 pies cuadrados) en el Bloque del Este, en comparación con los 113,5 metros cuadrados (1.222 pies cuadrados) en diez países occidentales para los que se disponía de datos comparables. [150] Los estándares de espacio variaban considerablemente: en 1986, la vivienda nueva media en la Unión Soviética era sólo el 68% del tamaño de su equivalente en Hungría. [150] Aparte de casos excepcionales, como Alemania del Este en 1980-1986 y Bulgaria en 1970-1980, los estándares de espacio en las viviendas de nueva construcción aumentaron antes de la disolución del Bloque del Este. [150] El tamaño de las viviendas variaba considerablemente a lo largo del tiempo, especialmente después de la crisis del petróleo en el Bloque del Este; Por ejemplo, las viviendas de Alemania Occidental en la década de 1990 tenían una superficie media de 83 metros cuadrados (890 pies cuadrados), en comparación con el tamaño medio de las viviendas en la RDA de 67 metros cuadrados (720 pies cuadrados) en 1967. [151] [152]

La mala vivienda fue uno de los cuatro factores principales (otros eran las malas condiciones de vida, el aumento del empleo femenino y el aborto como medio fomentado de control de la natalidad) que llevaron a la disminución de las tasas de natalidad en todo el Bloque del Este. [135]

Debido a la falta de señales del mercado , las economías del Bloque del Este experimentaron un desarrollo deficiente por parte de los planificadores centrales . [154] [155] El Bloque del Este también dependía de la Unión Soviética para obtener cantidades significativas de materiales. [154] [156]

El atraso tecnológico dio lugar a una dependencia de las importaciones procedentes de los países occidentales y, a su vez, a una demanda de divisas occidentales. Los países del bloque del Este se endeudaron en gran medida con el Club de París (bancos centrales) y el Club de Londres (bancos privados) y, a principios de los años 1980, la mayoría de ellos se vieron obligados a notificar a los acreedores su insolvencia. Sin embargo, esta información se mantuvo en secreto para los ciudadanos y la propaganda promovió la idea de que los países estaban en el mejor camino hacia el socialismo. [157] [158] [159]

Como consecuencia de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y de las ocupaciones alemanas en Europa del Este, gran parte de la región sufrió una enorme destrucción de la industria y de la infraestructura, así como pérdidas de vidas civiles. Sólo en Polonia, la política de saqueo y explotación causó enormes pérdidas materiales a la industria polaca (el 62% de la cual fue destruida), [160] a la agricultura, a la infraestructura y a los monumentos culturales, cuyo costo se ha estimado en aproximadamente 525.000 millones de euros o 640.000 millones de dólares en valores de cambio de 2004. [161]

En todo el Bloque del Este, tanto en la URSS como en el resto del Bloque, se le dio prominencia a Rusia y se la llamó la naiboleye vydayushchayasya natsiya (la nación más prominente) y el rukovodyashchiy narod (el pueblo líder). [162] Los soviéticos promovieron la reverencia de las acciones y características rusas y la construcción de jerarquías estructurales soviéticas en los demás países del Bloque del Este. [162]

.jpg/440px-Bucur_Obor_(1986).jpg)

La característica definitoria del totalitarismo estalinista fue la simbiosis única del Estado con la sociedad y la economía, lo que resultó en que la política y la economía perdieran sus características distintivas como esferas autónomas y distinguibles. [92] Inicialmente, Stalin dirigió sistemas que rechazaban las características institucionales occidentales de las economías de mercado , la gobernanza democrática (denominada "democracia burguesa" en el lenguaje soviético) y el estado de derecho que sometía la intervención discrecional del Estado. [94]

Los soviéticos ordenaron la expropiación y estatización de la propiedad privada. [163] Los "regímenes réplica" de estilo soviético que surgieron en el Bloque no sólo reprodujeron la economía de comando soviética , sino que también adoptaron los métodos brutales empleados por Joseph Stalin y las políticas secretas de estilo soviético para suprimir la oposición real y potencial. [163]

Los regímenes estalinistas del Bloque del Este veían incluso a grupos marginales de intelectuales de la oposición como una amenaza potencial debido a las bases que sustentaban el poder estalinista en ellos. [101] La supresión de la disidencia y la oposición era un prerrequisito central para la seguridad del poder estalinista dentro del Bloque del Este, aunque el grado de oposición y supresión de disidentes variaba según el país y el momento en todo el Bloque del Este. [101]

Además, los medios de comunicación en el Bloque del Este eran órganos del Estado, completamente dependientes y subordinados al gobierno de la URSS, con organizaciones de radio y televisión de propiedad estatal, mientras que los medios impresos eran generalmente propiedad de organizaciones políticas, en su mayoría del partido local. [104] Mientras que más de 15 millones de residentes del Bloque del Este emigraron hacia el oeste entre 1945 y 1949, [164] la emigración se detuvo efectivamente a principios de la década de 1950, con el enfoque soviético para controlar el movimiento nacional emulado por la mayor parte del resto del Bloque del Este. [122]

En la URSS, debido al estricto secreto soviético bajo Joseph Stalin , durante muchos años después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, incluso los extranjeros mejor informados no sabían efectivamente sobre las operaciones de la economía soviética. [165] Stalin había sellado el acceso exterior a la Unión Soviética desde 1935 (y hasta su muerte), permitiendo efectivamente que no hubiera viajes extranjeros dentro de la Unión Soviética, de modo que los forasteros no sabían de los procesos políticos que habían tenido lugar allí. [166] Durante este período, e incluso durante 25 años después de la muerte de Stalin, los pocos diplomáticos y corresponsales extranjeros permitidos dentro de la Unión Soviética estaban generalmente restringidos a unos pocos kilómetros de Moscú, sus teléfonos estaban intervenidos, sus residencias estaban restringidas a lugares exclusivos para extranjeros y eran constantemente seguidos por las autoridades soviéticas. [166]

Los soviéticos también modelaron las economías del resto del Bloque del Este fuera de la Unión Soviética siguiendo las líneas de la economía de comando soviética. [167] Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la Unión Soviética utilizó procedimientos draconianos para asegurar el cumplimiento de las directivas de invertir todos los activos de manera planificada por el Estado, incluida la colectivización de la agricultura y la utilización de un considerable ejército de trabajadores reunidos en el sistema de gulag . [168] Este sistema se impuso en gran medida a otros países del Bloque del Este después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [168] Si bien la propaganda de mejoras proletarias acompañó los cambios sistémicos, el terror y la intimidación del estalinismo despiadado consecuente ofuscaron los sentimientos de cualquier supuesto beneficio. [113]

Stalin consideraba que la transformación socioeconómica era indispensable para establecer el control soviético, lo que reflejaba la visión marxista-leninista de que las bases materiales, la distribución de los medios de producción, moldeaban las relaciones sociales y políticas. [66] Los cuadros entrenados en Moscú fueron colocados en posiciones de poder cruciales para cumplir órdenes relacionadas con la transformación sociopolítica. [66] La eliminación del poder social y financiero de la burguesía mediante la expropiación de la propiedad industrial y territorial recibió absoluta prioridad. [64]

Estas medidas fueron anunciadas públicamente como reformas más que como transformaciones socioeconómicas. [64] En todo el Bloque del Este, a excepción de Checoslovaquia , se erigieron "organizaciones sociales" como sindicatos y asociaciones que representaban a varios grupos sociales, profesionales y otros, con una sola organización para cada categoría, y sin competencia. [64] Esas organizaciones estaban dirigidas por cuadros estalinistas, aunque durante el período inicial permitieron cierta diversidad. [68]

Al mismo tiempo, al final de la guerra, la Unión Soviética adoptó una " política de saqueo " de transporte físico y reubicación de activos industriales de Europa del Este a la Unión Soviética. [169] Se exigió a los estados del Bloque del Este que proporcionaran carbón, equipo industrial, tecnología, material rodante y otros recursos para reconstruir la Unión Soviética. [170] Entre 1945 y 1953, los soviéticos recibieron una transferencia neta de recursos del resto del Bloque del Este bajo esta política de aproximadamente 14 mil millones de dólares, una cantidad comparable a la transferencia neta de los Estados Unidos a Europa occidental en el Plan Marshall . [170] [171] Las "reparaciones" incluyeron el desmantelamiento de los ferrocarriles en Polonia y las reparaciones rumanas a los soviéticos entre 1944 y 1948 valoradas en 1.800 millones de dólares simultáneamente con la dominación de los SovRoms . [168]

Además, los soviéticos reorganizaron las empresas como sociedades anónimas en las que los soviéticos poseían el interés de control. [171] [172] Utilizando ese vehículo de control, varias empresas tuvieron que vender productos a precios inferiores a los mundiales a los soviéticos, como las minas de uranio en Checoslovaquia y Alemania del Este , las minas de carbón en Polonia y los pozos de petróleo en Rumania . [173]

El modelo comercial de los países del bloque del Este se modificó severamente. [174] Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, no más del 1%-2% del comercio de esos países se realizaba con la Unión Soviética. [174] Para 1953, la proporción de dicho comercio había aumentado al 37%. [174] En 1947, Joseph Stalin también había denunciado el Plan Marshall y prohibió a todos los países del bloque del Este participar en él. [175]

El dominio soviético vinculó aún más a otras economías del bloque del Este [174] a Moscú a través del Consejo de Ayuda Económica Mutua (CAME) o Comecon , que determinaba las asignaciones de inversión de los países y los productos que se comercializarían dentro del bloque del Este. [176] Aunque el Comecon se inició en 1949, su papel se volvió ambiguo porque Stalin prefería vínculos más directos con otros jefes del partido que la sofisticación indirecta del consejo. No jugó un papel significativo en la década de 1950 en la planificación económica. [112]

Inicialmente, el Comecon sirvió como tapadera para la toma soviética de materiales y equipos del resto del Bloque del Este, pero el equilibrio cambió cuando los soviéticos se convirtieron en subsidiarios netos del resto del Bloque en la década de 1970 a través de un intercambio de materias primas de bajo costo a cambio de productos terminados de mala calidad. [113] Si bien recursos como el petróleo, la madera y el uranio inicialmente hicieron atractivo el acceso a otras economías del Bloque del Este, los soviéticos pronto tuvieron que exportar materias primas soviéticas a esos países para mantener la cohesión en ellos. [168] Después de la resistencia a los planes del Comecon de extraer los recursos minerales de Rumania y utilizar en gran medida su producción agrícola, Rumania comenzó a adoptar una postura más independiente en 1964. [116] Si bien no repudió al Comecon, no asumió un papel significativo en su funcionamiento, especialmente después del ascenso al poder de Nicolae Ceauşescu . [116]

Según la propaganda oficial en la Unión Soviética, la vivienda, la atención sanitaria y la educación eran asequibles sin precedentes. [177] [¿ Fuente poco fiable? ] El alquiler de un apartamento suponía, de media, sólo el 1% del presupuesto familiar, cifra que llegaba al 4% si se tenían en cuenta los servicios municipales. Los billetes de tranvía costaban 20 kopeks y una barra de pan, 15 kopeks. El salario mensual medio de un ingeniero era de 140 a 160 rublos . [178]

La Unión Soviética realizó importantes avances en el desarrollo del sector de bienes de consumo del país. En 1970, la URSS produjo 679 millones de pares de calzado de cuero, en comparación con los 534 millones de los Estados Unidos. Checoslovaquia, que tenía la mayor producción per cápita de zapatos del mundo, exportaba una parte importante de su producción de zapatos a otros países. [179]

El aumento del nivel de vida en el socialismo condujo a una disminución constante de la jornada laboral y a un aumento del tiempo libre. En 1974, la semana laboral media de los trabajadores industriales soviéticos era de 40 horas. En 1968, las vacaciones pagadas alcanzaron un mínimo de 15 días laborables. A mediados de los años 70, el número de días libres al año (días libres, feriados y vacaciones) era de 128 a 130, casi el doble de la cifra de los diez años anteriores. [180]

Debido a la falta de señales del mercado en dichas economías, experimentaron un desarrollo incorrecto por parte de los planificadores centrales, lo que resultó en que esos países siguieran un camino de desarrollo extensivo (gran movilización de capital, mano de obra, energía y materias primas utilizados ineficientemente) en lugar de un desarrollo intensivo (uso eficiente de los recursos) para intentar lograr un crecimiento rápido. [154] [181] Los países del Bloque del Este tuvieron que seguir el modelo soviético, que enfatizaba demasiado la industria pesada a expensas de la industria ligera y otros sectores. [182]

Como ese modelo implicaba la explotación pródiga de los recursos naturales y de otro tipo, se lo ha descrito como una especie de modalidad de "tala y quema". [181] Si bien el sistema soviético se esforzaba por lograr una dictadura del proletariado , había poco proletariado existente en muchos países de Europa del Este, de modo que para crear uno, era necesario construir una industria pesada. [182] Cada sistema compartía los temas distintivos de las economías orientadas al Estado, incluidos los derechos de propiedad mal definidos, la falta de precios de equilibrio del mercado y capacidades productivas exageradas o distorsionadas en relación con las economías de mercado análogas. [92]

En los sistemas de asignación y distribución de recursos se produjeron errores y despilfarro importantes. [144] Debido a los órganos estatales monolíticos dirigidos por el partido, estos sistemas no ofrecían mecanismos ni incentivos eficaces para controlar los costes, el despilfarro, la ineficiencia y el despilfarro. [144] Se dio prioridad a la industria pesada debido a su importancia para el estamento militar-industrial y para el sector de la ingeniería. [183]

Las fábricas a veces estaban ubicadas de manera ineficiente, lo que generaba altos costos de transporte, mientras que la mala organización de las plantas a veces daba como resultado retrasos en la producción y efectos secundarios en otras industrias que dependían de proveedores monopolistas de productos intermedios. [184] Por ejemplo, cada país, incluida Albania , construyó fábricas de acero independientemente de si carecían de los recursos necesarios de energía y minerales. [182] Se construyó una enorme planta metalúrgica en Bulgaria a pesar del hecho de que sus minerales tenían que ser importados de la Unión Soviética y transportados 320 kilómetros (200 millas) desde el puerto de Burgas . [182] Una fábrica de tractores de Varsovia en 1980 tenía una lista de 52 páginas de equipos oxidados y sin usar, entonces inútiles. [182]

This emphasis on heavy industry diverted investment from the more practical production of chemicals and plastics.[176] In addition, the plans' emphasis on quantity rather than quality made Eastern Bloc products less competitive in the world market.[176] High costs passed through the product chain boosted the 'value' of production on which wage increases were based, but made exports less competitive.[184] Planners rarely closed old factories even when new capacities opened elsewhere.[184] For example, the Polish steel industry retained a plant in Upper Silesia despite the opening of modern integrated units on the periphery while the last old Siemens-Martin process furnace installed in the 19th century was not closed down immediately.[184]

Producer goods were favoured over consumer goods, causing consumer goods to be lacking in quantity and quality in the shortage economies that resulted.[155][181]

By the mid-1970s, budget deficits rose considerably and domestic prices widely diverged from the world prices, while production prices averaged 2% higher than consumer prices.[185] Many premium goods could be bought either in a black market or only in special stores using foreign currency generally inaccessible to most Eastern Bloc citizens, such as Intershop in East Germany,[186] Beryozka in the Soviet Union,[187] Pewex in Poland,[188][189] Tuzex in Czechoslovakia,[190] Corecom in Bulgaria, or Comturist in Romania. Much of what was produced for the local population never reached its intended user, while many perishable products became unfit for consumption before reaching their consumers.[144]

As a result of the deficiencies of the official economy, black markets were created that were often supplied by goods stolen from the public sector.[191][192] The second, "parallel economy" flourished throughout the Bloc because of rising unmet state consumer needs.[193] Black and gray markets for foodstuffs, goods, and cash arose.[193] Goods included household goods, medical supplies, clothes, furniture, cosmetics and toiletries in chronically short supply through official outlets.[189]

Many farmers concealed actual output from purchasing agencies to sell it illicitly to urban consumers.[189] Hard foreign currencies were highly sought after, while highly valued Western items functioned as a medium of exchange or bribery in Stalinist countries, such as in Romania, where Kent cigarettes served as an unofficial extensively used currency to buy goods and services.[194] Some service workers moonlighted illegally providing services directly to customers for payment.[194]

The extensive production industrialization that resulted was not responsive to consumer needs and caused a neglect in the service sector, unprecedented rapid urbanization, acute urban overcrowding, chronic shortages, and massive recruitment of women into mostly menial and/or low-paid occupations.[144] The consequent strains resulted in the widespread used of coercion, repression, show trials, purges, and intimidation.[144] By 1960, massive urbanisation occurred in Poland (48% urban) and Bulgaria (38%), which increased employment for peasants, but also caused illiteracy to skyrocket when children left school for work.[144]

Cities became massive building sites, resulting in the reconstruction of some war-torn buildings but also the construction of drab, dilapidated, system-built apartment blocks.[144] Urban living standards plummeted because resources were tied up in huge long-term building projects, while industrialization forced millions of former peasants to live in hut camps or grim apartment blocks close to massive polluting industrial complexes.[144]

Collectivization is a process pioneered by Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s by which Marxist–Leninist regimes in the Eastern Bloc and elsewhere attempted to establish an ordered socialist system in rural agriculture.[195] It required the forced consolidation of small-scale peasant farms and larger holdings belonging to the landed classes for the purpose of creating larger modern "collective farms" owned, in theory, by the workers therein. In reality, such farms were owned by the state.[195]

In addition to eradicating the perceived inefficiencies associated with small-scale farming on discontiguous land holdings, collectivization also purported to achieve the political goal of removing the rural basis for resistance to Stalinist regimes.[195] A further justification given was the need to promote industrial development by facilitating the state's procurement of agricultural products and transferring "surplus labor" from rural to urban areas.[195] In short, agriculture was reorganized in order to proletarianize the peasantry and control production at prices determined by the state.[196]

The Eastern Bloc possesses substantial agricultural resources, especially in southern areas, such as Hungary's Great Plain, which offered good soils and a warm climate during the growing season.[196] Rural collectivization proceeded differently in non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries than it did in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s.[197] Because of the need to conceal the assumption of control and the realities of an initial lack of control, no Soviet dekulakisation-style liquidation of rich peasants could be carried out in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries.[197]

Nor could they risk mass starvation or agricultural sabotage (e.g., holodomor) with a rapid collectivization through massive state farms and agricultural producers' cooperatives (APCs).[197] Instead, collectivization proceeded more slowly and in stages from 1948 to 1960 in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, and from 1955 to 1964 in Albania.[197] Collectivization in the Baltic republics of the Lithuanian SSR, Estonian SSR and Latvian SSR took place between 1947 and 1952.[198]

Unlike Soviet collectivization, neither massive destruction of livestock nor errors causing distorted output or distribution occurred in the other Eastern Bloc countries.[197] More widespread use of transitional forms occurred, with differential compensation payments for peasants that contributed more land to APCs.[197] Because Czechoslovakia and East Germany were more industrialized than the Soviet Union, they were in a position to furnish most of the equipment and fertilizer inputs needed to ease the transition to collectivized agriculture.[181] Instead of liquidating large farmers or barring them from joining APCs as Stalin had done through dekulakisation, those farmers were utilised in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc collectivizations, sometimes even being named farm chairman or managers.[181]

Collectivisation often met with strong rural resistance, including peasants frequently destroying property rather than surrendering it to the collectives.[195] Strong peasant links with the land through private ownership were broken and many young people left for careers in industry.[196] In Poland and Yugoslavia, fierce resistance from peasants, many of whom had resisted the Axis, led to the abandonment of wholesale rural collectivisation in the early 1950s.[181] In part because of the problems created by collectivisation, agriculture was largely de-collectivised in Poland in 1957.[195]

The fact that Poland nevertheless managed to carry out large-scale centrally planned industrialisation with no more difficulty than its collectivised Eastern Bloc neighbours further called into question the need for collectivisation in such planned economies.[181] Only Poland's "western territories", those eastwardly adjacent to the Oder-Neisse line that were annexed from Germany, were substantially collectivised, largely in order to settle large numbers of Poles on good farmland which had been taken from German farmers.[181]

There was significant progress made in the economy in countries such as the Soviet Union. In 1980, the Soviet Union took first place in Europe and second worldwide in terms of industrial and agricultural production, respectively. In 1960, the USSR's industrial output was only 55% that of America, but this increased to 80% in 1980.[177][unreliable source?]

With the change of the Soviet leadership in 1964, there were significant changes made to economic policy. The Government on 30 September 1965 issued a decree "On improving the management of industry" and the 4 October 1965 resolution "On improving and strengthening the economic incentives for industrial production". The main initiator of these reforms was Premier A. Kosygin. Kosygin's reforms on agriculture gave considerable autonomy to the collective farms, giving them the right to the contents of private farming. During this period, there was the large-scale land reclamation program, the construction of irrigation channels, and other measures.[177] In the period 1966–1970, the gross national product grew by over 35%. Industrial output increased by 48% and agriculture by 17%.[177] In the eighth Five-Year Plan, the national income grew at an average rate of 7.8%. In the ninth Five-Year Plan (1971–1975), the national income grew at an annual rate of 5.7%. In the tenth Five-Year Plan (1976–1981), the national income grew at an annual rate of 4.3%.[177]

The Soviet Union made noteworthy scientific and technological progress. Unlike countries with more market-oriented economies, scientific and technological potential in the USSR was used in accordance with a plan on the scale of society as a whole.[199]

In 1980, the number of scientific personnel in the USSR was 1.4 million. The number of engineers employed in the national economy was 4.7 million. Between 1960 and 1980, the number of scientific personnel increased by a factor of 4. In 1975, the number of scientific personnel in the USSR amounted to one-fourth of the total number of scientific personnel in the world. In 1980, as compared with 1940, the number of invention proposals submitted was more than 5 million. In 1980, there were 10 all-Union research institutes, 85 specialised central agencies, and 93 regional information centres.[200]

The world's first nuclear power plant was commissioned on 27 June 1954 in Obninsk.[citation needed] Soviet scientists made a major contribution to the development of computer technology. The first major achievements in the field were associated with the building of analog computers. In the USSR, principles for the construction of network analysers were developed by S. Gershgorin in 1927 and the concept of the electrodynamic analog computer was proposed by N. Minorsky in 1936. In the 1940s, the development of AC electronic antiaircraft directors and the first vacuum-tube integrators was begun by L. Gutenmakher. In the 1960s, important developments in modern computer equipment were the BESM-6 system built under the direction of S. A. Lebedev, the MIR series of small digital computers, and the Minsk series of digital computers developed by G.Lopato and V. Przhyalkovsky.[201]

Author Turnock claims that transport in the Eastern Bloc was characterised by poor infrastructural maintenance.[202] The road network suffered from inadequate load capacity, poor surfacing and deficient roadside servicing.[202] While roads were resurfaced, few new roads were built and there were very few divided highway roads, urban ring roads or bypasses.[203] Private car ownership remained low by Western standards.[203]

Vehicle ownership increased in the 1970s and 1980s with the production of inexpensive cars in East Germany such as Trabants and the Wartburgs.[203] However, the wait list for the distribution of Trabants was ten years in 1987 and up to fifteen years for Soviet Lada and Czechoslovakian Škoda cars.[203] Soviet-built aircraft exhibited deficient technology, with high fuel consumption and heavy maintenance demands.[202] Telecommunications networks were overloaded.[202]

Adding to mobility constraints from the inadequate transport systems were bureaucratic mobility restrictions.[204] While outside of Albania, domestic travel eventually became largely regulation-free, stringent controls on the issue of passports, visas and foreign currency made foreign travel difficult inside the Eastern Bloc.[204] Countries were inured to isolation and initial post-war autarky, with each country effectively restricting bureaucrats to viewing issues from a domestic perspective shaped by that country's specific propaganda.[204]

Severe environmental problems arose through urban traffic congestion, which was aggravated by pollution generated by poorly maintained vehicles.[204] Large thermal power stations burning lignite and other items became notorious polluters, while some hydro-electric systems performed inefficiently because of dry seasons and silt accumulation in reservoirs.[205] Kraków was covered by smog 135 days per year while Wrocław was covered by a fog of chrome gas.[specify][206]

Several villages were evacuated because of copper smelting at Głogów.[206] Further rural problems arose from piped water construction being given precedence over building sewerage systems, leaving many houses with only inbound piped water delivery and not enough sewage tank trucks to carry away sewage.[207] The resulting drinking water became so polluted in Hungary that over 700 villages had to be supplied by tanks, bottles and plastic bags.[207] Nuclear power projects were prone to long commissioning delays.[205]

The catastrophe at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Ukrainian SSR was caused by an irresponsible safety test on a reactor design that is normally safe,[208] some operators lacking an even basic understanding of the reactor's processes and authoritarian Soviet bureaucracy, valuing party loyalty over competence, that kept promoting incompetent personnel and choosing cheapness over safety.[209][210] The consequent release of fallout resulted in the evacuation and resettlement of over 336,000 people[211] leaving a massive desolate Zone of alienation containing extensive still-standing abandoned urban development.

Tourism from outside the Eastern Bloc was neglected, while tourism from other Stalinist countries grew within the Eastern Bloc.[212] Tourism drew investment, relying upon tourism and recreation opportunities existing before World War II.[213] By 1945, most hotels were run-down, while many which escaped conversion to other uses by central planners were slated to meet domestic demands.[213] Authorities created state companies to arrange travel and accommodation.[213] In the 1970s, investments were made to attempt to attract western travelers, though momentum for this waned in the 1980s when no long-term plan arose to procure improvements in the tourist environment, such as an assurance of freedom of movement, free and efficient money exchange and the provision of higher quality products with which these tourists were familiar.[212] However, Western tourists were generally free to move about in Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia and go where they wished. It was more difficult or even impossible to go as an individual tourist to East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. It was generally possible in all cases for relatives from the west to visit and stay with family in the Eastern Bloc countries, except for Albania. In these cases, permission had to be sought, precise times, length of stay, location and movements had to be known in advance.

Catering to western visitors required creating an environment of an entirely different standard than that used for the domestic populace, which required concentration of travel spots including the building of relatively high-quality infrastructure in travel complexes, which could not easily be replicated elsewhere.[212] Because of a desire to preserve ideological discipline and the fear of the presence of wealthier foreigners engaging in differing lifestyles, Albania segregated travelers.[214] Because of the worry of the subversive effect of the tourist industry, travel was restricted to 6,000 visitors per year.[215]

Growth rates in the Eastern Bloc were initially high in the 1950s and 1960s.[167] During this first period, progress was rapid by European standards and per capita growth within the Eastern Bloc increased by 2.4 times the European average.[184] Eastern Europe accounted for 12.3 percent of European production in 1950 but 14.4 in 1970.[184] However, the system was resistant to change and did not easily adapt to new conditions. For political reasons, old factories were rarely closed, even when new technologies became available.[184] As a result, after the 1970s, growth rates within the bloc experienced relative decline.[216] Meanwhile, West Germany, Austria, France and other Western European nations experienced increased economic growth in the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle"), Trente Glorieuses ("thirty glorious years") and the post-World War II boom.

From the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, the economy of the Eastern Bloc steadily increased at the same rate as the economy in Western Europe, with the non-reformist Stalinist nations of the Eastern Bloc having a stronger economy than the reformist-Stalinist states.[217] While most western European economies essentially began to approach the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) levels of the United States during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Eastern Bloc countries did not,[216] with per capita GDPs trailing significantly behind their comparable western European counterparts.[218]

The following table displays a set of estimated growth rates of GDP from 1951 onward, for the countries of the Eastern Bloc as well as those of Western Europe as reported by The Conference Board as part of its Total Economy Database. In some cases data availability does not go all the way back to 1951.

The United Nations Statistics Division also calculates growth rates, using a different methodology, but only reports the figures starting in 1971 (for Slovakia and the constituent republics of the USSR data availability begins later). Thus, according to the United Nations growth rates in Europe were as follows:

The following table lists the level of nominal GDP per capita in certain selected countries, measured in US dollars, for the years 1970, 1989, and 2015:

While it can be argued the World Bank estimates of GDP used for 1990 figures underestimate Eastern Bloc GDP because of undervalued local currencies, per capita incomes were undoubtedly lower than in their counterparts.[218] East Germany was the most advanced industrial nation of the Eastern Bloc.[186] Until the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, East Germany was considered a weak state, hemorrhaging skilled labor to the West such that it was referred to as "the disappearing satellite".[222] Only after the wall sealed in skilled labor was East Germany able to ascend to the top economic spot in the Eastern Bloc.[222] Thereafter, its citizens enjoyed a higher quality of life and fewer shortages in the supply of goods than those in the Soviet Union, Poland or Romania.[186]

While official statistics painted a relatively rosy picture, the East German economy had eroded because of increased central planning, economic autarky, the use of coal over oil, investment concentration in a few selected technology-intensive areas and labor market regulation.[223] As a result, a large productivity gap of nearly 50% per worker existed between East and West Germany.[223][224] However, that gap does not measure the quality of design of goods or service such that the actual per capita rate may be as low as 14 to 20 per cent.[224] Average gross monthly wages in East Germany were around 30% of those in West Germany, though after accounting for taxation the figures approached 60%.[225]

Moreover, the purchasing power of wages differed greatly, with only about half of East German households owning either a car or a color television set as late as 1990, both of which had been standard possessions in West German households.[225] The Ostmark was only valid for transactions inside East Germany, could not be legally exported or imported[225] and could not be used in the East German Intershops which sold premium goods.[186] In 1989, 11% of the East German labor force remained in agriculture, 47% was in the secondary sector and 42% in services.[224]

Once installed, the economic system was difficult to change given the importance of politically reliable management and the prestige value placed on large enterprises.[184] Performance declined during the 1970s and 1980s due to inefficiency when industrial input costs, such as energy prices, increased.[184] Though growth lagged behind the West, it did occur.[176] Consumer goods started to become more available by the 1960s.[176]

Before the Eastern Bloc's dissolution, some major sectors of industry were operating at such a loss that they exported products to the West at prices below the real value of the raw materials.[226] Hungarian steel costs doubled those of western Europe.[226] In 1985, a quarter of Hungary's state budget was spent on supporting inefficient enterprises.[226] Tight planning in Bulgaria's industry meant continuing shortages in other parts of its economy.[226]

In social terms, the 18 years (1964–1982) of Brezhnev's leadership saw real incomes grow more than 1.5 times. More than 1.6 billion square metres of living space were commissioned and provided to over 160 million people. At the same time, the average rent for families did not exceed 3% of the family income. There was unprecedented affordability of housing, health care and education.[177]

In a survey by the Sociological Research Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1986, 75% of those surveyed said that they were better off than the previous ten years. Over 95% of Soviet adults considered themselves "fairly well off". 55% of those surveyed felt that medical services improved, 46% believed public transportation had improved and 48% said that the standard of services provided public service establishments had risen.[227]

During the years 1957–1965, housing policy underwent several institutional changes with industrialisation and urbanisation had not been matched by an increase in housing after World War II.[228] Housing shortages in the Soviet Union were worse than in the rest of the Eastern Bloc due to a larger migration to the towns and more wartime devastation and were worsened by Stalin's pre-war refusals to invest properly in housing.[228] Because such investment was generally not enough to sustain the existing population, apartments had to be subdivided into increasingly smaller units, resulting in several families sharing an apartment previously meant for one family.[228]

The prewar norm became one Soviet family per room, with the toilets and kitchen shared.[228] The amount of living space in urban areas fell from 5.7 square metres per person in 1926 to 4.5 square metres in 1940.[228] In the rest of the Eastern Bloc during this time period, the average number of people per room was 1.8 in Bulgaria (1956), 2.0 in Czechoslovakia (1961), 1.5 in Hungary (1963), 1.7 in Poland (1960), 1.4 in Romania (1966), 2.4 in Yugoslavia (1961) and 0.9 in 1961 in East Germany.[228]

After Stalin's death in 1953, forms of an economic "New Course" brought a revival of private house construction.[228] Private construction peaked in 1957–1960 in many Eastern Bloc countries and then declined simultaneously along with a steep increase in state and co-operative housing.[228] By 1960, the rate of housebuilding per head had picked up in all countries in the Eastern Bloc.[228] Between 1950 and 1975, worsening shortages were generally caused by a fall in the proportion of all investment made housing.[229] However, during that period the total number of dwellings increased.[230]