La dinastía Nguyễn ( en vietnamita : 茹阮; en vietnamita : Nhà Nguyễn ; en vietnamita :朝阮) fue la última dinastía vietnamita , precedida por los señores Nguyễn y que gobernó el estado vietnamita unificado de forma independiente desde 1802 hasta 1883 antes de convertirse en un protectorado francés. Durante su existencia, el imperio se expandió hasta el sur de Vietnam, Camboya y Laos a través de una continuación de las guerras de siglos de Nam tiến y siameses-vietnamitas . Con la conquista francesa de Vietnam , la dinastía Nguyễn se vio obligada a ceder la soberanía sobre partes del sur de Vietnam a Francia en 1862 y 1874, y después de 1883 la dinastía Nguyễn solo gobernó nominalmente los protectorados franceses de Annam (en el centro de Vietnam) así como Tonkín (en el norte de Vietnam). Más tarde cancelaron los tratados con Francia y fueron el Imperio de Vietnam por un corto tiempo hasta el 25 de agosto de 1945.

La familia Nguyễn Phúc estableció un gobierno feudal sobre grandes cantidades de territorio como los señores Nguyễn (1558-1777, 1780-1802) en el siglo XVI antes de derrotar a la dinastía Tây Sơn y establecer su propio gobierno imperial en el siglo XIX. El gobierno dinástico comenzó con Gia Long ascendiendo al trono en 1802, después de poner fin a la dinastía Tây Sơn anterior. La dinastía Nguyễn fue absorbida gradualmente por Francia en el transcurso de varias décadas en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, comenzando con la Campaña de Cochinchina en 1858 que condujo a la ocupación de la zona sur de Vietnam . Siguieron una serie de tratados desiguales ; El territorio ocupado pasó a ser la colonia francesa de Cochinchina en el Tratado de Saigón de 1862 , y el Tratado de Huế de 1863 dio a Francia acceso a los puertos vietnamitas y aumentó el control de sus asuntos exteriores. Finalmente, los Tratados de Huế de 1883 y 1884 dividieron el territorio vietnamita restante en los protectorados de Annam y Tonkín bajo el gobierno nominal de Nguyễn Phúc. En 1887, Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkín y el Protectorado francés de Camboya se agruparon para formar la Indochina francesa .

La dinastía Nguyễn siguió siendo la dinastía imperial formal de Annam y Tonkín en Indochina hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Japón había ocupado Indochina con la colaboración francesa en 1940, pero como la guerra parecía cada vez más perdida, Japón derrocó a la administración francesa en marzo de 1945 y proclamó la independencia de sus países constituyentes. El Imperio de Vietnam bajo el emperador Bao Dai fue un estado títere japonés nominalmente independiente durante los últimos meses de la guerra. Terminó con la abdicación de Bao Dai tras la rendición de Japón y la Revolución de Agosto del Viet Minh anticolonial en agosto de 1945. Esto puso fin al gobierno de 143 años de la dinastía Nguyễn. [7]

El nombre Việt Nam ( pronunciación vietnamita: [viə̀t naːm] , chữ Hán :越南) es una variación de Nam Việt (南越; literalmente " Việt del Sur "), un nombre que se remonta a la dinastía Triệu del siglo II a. C. [8] El término "Việt" (Yue) ( chino :越; pinyin : Yuè ; cantonés Yale : Yuht ; Wade–Giles : Yüeh 4 ; vietnamita : Việt ) en chino medio temprano se escribió por primera vez utilizando el logograma "戉" para un hacha (un homófono), en inscripciones de hueso de oráculo y bronce de finales de la dinastía Shang ( c. 1200 a. C.), y más tarde como "越". [9] En ese momento se refería a un pueblo o jefe al noroeste de Shang. [10] A principios del siglo VIII a. C., una tribu en el medio Yangtsé se llamaba Yangyue , un término utilizado más tarde para los pueblos más al sur. [10] Entre los siglos VII y IV a. C. Yue/Việt se refería al Estado de Yue en la cuenca baja del Yangtsé y su gente. [9] [10] Desde el siglo III a. C. el término se utilizó para las poblaciones no chinas del sur y suroeste de China y el norte de Vietnam, con grupos étnicos particulares llamados Minyue , Ouyue , Luoyue (vietnamita: Lạc Việt ), etc., llamados colectivamente Baiyue (Bách Việt, chino :百越; pinyin : Bǎiyuè ; cantonés Yale : Baak Yuet ; vietnamita : Bách Việt ; "Cien Yue/Viet"; ). [9] [10] [11] El término Baiyue/Bách Việt apareció por primera vez en el libro Lüshi Chunqiu compilado alrededor del 239 a. C. [12] En los siglos XVII y XVIII, los vietnamitas educados se llamaban a sí mismos y a su gente como người Việt y người Nam , que se combinaron para convertirse en người Việt Nam (pueblo vietnamita). Sin embargo, esta designación era para los propios vietnamitas y no para todo el país.[13]

La forma Việt Nam (越南) se registró por primera vez en el poema oracular del siglo XVI Sấm Trạng Trình . El nombre también se ha encontrado en 12 estelas talladas en los siglos XVI y XVII, incluida una en la pagoda Bao Lam en Hải Phòng que data de 1558. [14] En 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (que más tarde se convirtió en el emperador Gia Long) estableció la dinastía Nguyễn. En el segundo año de su gobierno, le pidió al emperador Jiaqing de la dinastía Qing que le confiriera el título de 'Rey de Nam Việt / Nanyue' (南越en carácter chino) después de tomar el poder en Annam. El emperador se negó porque el nombre estaba relacionado con Nanyue de Zhao Tuo , que incluía las regiones de Guangxi y Guangdong en el sur de China. Por lo tanto, el emperador Qing decidió llamar a la zona "Viet Nam" en su lugar. [15] Entre 1804 y 1813, el nombre Vietnam fue utilizado oficialmente por el emperador Gia Long. [a]

En 1839, bajo el gobierno del emperador Minh Mạng , el nombre oficial del imperio fue Đại Việt Nam (大越南, que significa "Gran Vietnam"), y se acortó a Đại Nam (大南, que significa "Gran Sur"). [17] [18]

Durante la década de 1930, su gobierno utilizó el nombre Nam Triều (南朝, dinastía del Sur) en sus documentos oficiales. [19]

Los occidentales en el pasado solían llamar al reino Annam [20] [21] o el Imperio Annamita. [22] Sin embargo, en la historiografía vietnamita, los historiadores modernos a menudo se refieren a este período en la historia vietnamita como Nguyễn Vietnam , [23] o simplemente Vietnam para distinguirlo del reino Đại Việt anterior al siglo XIX . [24]

El clan Nguyễn, que se originó en la provincia de Thanh Hóa, había ejercido durante mucho tiempo una influencia política sustancial y un poder militar a lo largo de la historia moderna vietnamita de una forma u otra. Las afiliaciones del clan con las élites gobernantes se remontan al siglo X, cuando Nguyễn Bặc fue nombrado primer gran canciller de la efímera dinastía Đinh bajo el emperador Đinh Bộ Lĩnh en 965. [25] Otro ejemplo de sus influencias se materializa a través de Nguyễn Thị Anh , la emperatriz consorte del emperador Lê Thái Tông ; sirvió como regente oficial de Đại Việt para su hijo, el emperador niño Lê Nhân Tông entre 1442 y 1453. [26]

En 1527, Mạc Đăng Dung , después de derrotar y ejecutar al vasallo de la dinastía Lê , Nguyễn Hoằng Dụ en una rebelión, emergió como el vencedor intermedio y estableció la dinastía Mạc . Lo hizo deponiendo al emperador Lê, Lê Cung Hoàng , tomando el trono para sí mismo, terminando efectivamente con la dinastía Lê, una vez próspera pero en decadencia . El hijo de Nguyễn Hoằng Dụ, Nguyễn Kim , el líder del clan Nguyễn con sus aliados, el clan Trịnh permaneció ferozmente leal a la dinastía Lê . Intentaron restaurar la dinastía Lê en el poder, encendiendo una rebelión anti-Mạc, a favor de la causa leal. [27] [28] Tanto el clan Trịnh como el clan Nguyễn volvieron a tomar las armas en la provincia de Thanh Hóa y se rebelaron contra los Mạc. Sin embargo, la rebelión inicial fracasó y las fuerzas leales tuvieron que huir al reino de Lan Xang , donde el rey Photisarath les permitió establecer un gobierno leal exiliado en Xam Neua (actual Laos). Los leales a Lê bajo el mando de Lê Ninh, un descendiente de la familia imperial, escaparon a Muang Phuan (hoy Laos ). Durante este exilio, el marqués de An Thanh, Nguyễn Kim convocó a los que todavía eran leales al emperador Lê y formó un nuevo ejército para comenzar otra revuelta contra Mạc Đăng Dung. En 1539, la coalición regresó a Đại Việt comenzando su campaña militar contra los Mạc en Thanh Hóa , capturando a los Tây Đô en 1543.

En 1539, la dinastía Lê fue restaurada en oposición a los Mạc en Thăng Long , esto ocurrió después de que los leales capturaran la provincia de Thanh Hoá, reinstalando al emperador Lê Trang Tông en el trono. Sin embargo, los Mạc en este punto todavía controlaban la mayor parte del país, incluida la capital, Thăng Long . Nguyễn Kim , quien había servido como líder de los leales durante los 12 años de la Guerra Lê-Mạc (de 1533 a 1545) y durante el período de las dinastías del Norte y del Sur , fue asesinado en 1545 por un general Mạc capturado, Dương Chấp Nhất. Poco después de la muerte de Nguyễn Kim, su yerno, Trịnh Kiểm , líder del clan Trịnh, mató a Nguyễn Uông, el hijo mayor de Kim, para hacerse con el control de las fuerzas leales. El sexto hijo de Kim, Nguyễn Hoàng , teme que su destino sea como el de su hermano mayor; por ello, intentó escapar de la capital para evitar las purgas. Más tarde, le pide a su hermana, Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Bảo (la esposa de Trịnh Kiểm) que le pida a Kiểm que lo nombre gobernador de la frontera sur de Đại Việt, Thuận Hóa (actual provincia de Quảng Bình a Quảng Nam). Trịnh Kiểm, pensando en esta propuesta como una oportunidad para quitarle el poder y la influencia a Nguyễn Hoàng de la ciudad capital, aceptó la propuesta.

En 1558, Lê Anh Tông , emperador de la recién restaurada dinastía Lê, nombró a Nguyễn Hoàng señorío de Thuận Hóa , el territorio que había sido conquistado previamente durante el siglo XV al reino de Champa . Este hecho de que Nguyễn Hoàng abandonara Thăng Long sentó las bases para la eventual fragmentación y división de Đại Việt más adelante, ya que el clan Trịnh consolidaría su poder en el norte , estableciendo un sistema político único en el que los emperadores Lê reinarían (como figuras decorativas) pero los señores Trịnh gobernarían (ejerciendo el poder político real). Mientras tanto, los descendientes del clan Nguyễn, a través del linaje de Nguyễn Hoàng, gobernarían en el sur ; El clan Nguyễn, al igual que sus parientes Trịnh en el norte, reconoce la autoridad de los emperadores Lê sobre Đại Việt, pero al mismo tiempo ejerce poder político únicamente sobre su propio territorio. [29] Sin embargo, el cisma oficial de las dos familias no comenzaría hasta 1627, la primera guerra entre las dos.

Nguyễn Phúc Lan eligió la ciudad de Phú Xuân en 1636 como su residencia y estableció el dominio del señor Nguyễn en la parte sur del país. Aunque los señores Nguyễn y Trịnh gobernaron como gobernantes de facto en sus respectivas tierras, rindieron tributo oficial a los emperadores Lê en un gesto ceremonial y reconocieron a la dinastía Lê como la legitimidad de Đại Việt .

Nguyễn Hoàng y sus sucesores comenzaron a rivalizar con los señores Trịnh , después de negarse a pagar impuestos y tributos al gobierno central en Hanoi mientras los señores Nguyễn intentaban crear el régimen autónomo. Expandieron su territorio al convertir partes de Camboya en un protectorado, invadieron Laos , capturaron los últimos vestigios de Champa en 1693 y gobernaron en una línea ininterrumpida hasta 1776. [30] [31] [32]

La guerra del siglo XVII entre los Trịnh y los Nguyễn terminó en una paz incómoda, con los dos bandos creando estados separados de facto aunque ambos profesaban lealtad a la misma dinastía Lê . Después de 100 años de paz interna, los señores Nguyễn se enfrentaron a la rebelión de Tây Sơn en 1774. Su ejército había sufrido pérdidas considerables de personal después de una serie de campañas en Camboya y se mostró incapaz de contener la revuelta. A finales de año, los señores Trịnh habían formado una alianza con los rebeldes Tây Sơn y capturaron Huế en 1775. [33]

El señor Nguyễn, Nguyễn Phúc Thuần huyó al sur, a la provincia de Quảng Nam , donde dejó una guarnición bajo el mando del cogobernante Nguyễn Phúc Dương . Huyó más al sur, a la provincia de Gia Định (alrededor de la actual ciudad de Ho Chi Minh) por mar antes de la llegada del líder de Tây Sơn, Nguyễn Nhạc , cuyas fuerzas derrotaron a la guarnición de Nguyễn y se apoderaron de Quảng Nam. [34]

A principios de 1777, una gran fuerza de Tây Sơn bajo el mando de Nguyễn Huệ y Nguyễn Lữ atacó y capturó Gia Định desde el mar y derrotó a las fuerzas del señor Nguyễn. Los Tây Sơn recibieron un amplio apoyo popular, ya que se presentaron como campeones del pueblo vietnamita, que rechazaba cualquier influencia extranjera y luchaba por la reinstauración total de la dinastía Lê. Por lo tanto, la eliminación de los señoríos Nguyễn y Trinh se consideró una prioridad y todos los miembros de la familia Nguyễn, excepto uno, capturados en Saigón fueron ejecutados.

En 1775, Nguyễn Ánh, de 13 años, escapó y, con la ayuda del sacerdote católico vietnamita Paul Hồ Văn Nghị, pronto llegó a la Sociedad de Misiones Extranjeras de París en Hà Tiên . Con los grupos de búsqueda de Tây Son acercándose, siguió avanzando y finalmente conoció al misionero francés Pigneau de Behaine . Al retirarse a las islas Thổ Chu en el golfo de Tailandia, ambos escaparon de la captura de Tây Sơn. [35] [36] [37]

Pigneau de Behaine decidió apoyar a Ánh, que se había declarado heredero del señorío de Nguyễn. Un mes después, el ejército de Tây Sơn bajo el mando de Nguyễn Huệ había regresado a Quy Nhơn . Ánh aprovechó la oportunidad y rápidamente reunió un ejército en su nueva base en Long Xuyên , marchó a Gia Định y ocupó la ciudad en diciembre de 1777. Los Tây Sơn regresaron a Gia Định en febrero de 1778 y recuperaron la provincia. Cuando Ánh se acercó con su ejército, los Tây Sơn se retiraron. [38]

En el verano de 1781, las fuerzas de Ánh habían aumentado a 30.000 soldados, 80 acorazados, tres grandes barcos y dos barcos portugueses adquiridos con la ayuda de De Behaine. Ánh organizó una emboscada infructuosa a los campamentos de base de Tây Sơn en la provincia de Phú Yên . En marzo de 1782, el emperador de Tây Sơn , Thái Đức, y su hermano Nguyễn Huệ enviaron una fuerza naval para atacar a Ánh. El ejército de Ánh fue derrotado y huyó a través de Ba Giồng a Svay Rieng en Camboya.

Ánh se reunió con el rey camboyano Ang Eng , quien le concedió el exilio y le ofreció apoyo en su lucha contra los Tây Sơn. En abril de 1782, un ejército de los Tây Sơn invadió Camboya, detuvo y obligó a Ang Eng a pagar tributo y exigió que todos los ciudadanos vietnamitas que vivían en Camboya regresaran a Vietnam. [39]

El apoyo de los vietnamitas chinos comenzó cuando la dinastía Qing derrocó a la dinastía Ming . Los chinos Han se negaron a vivir bajo el régimen manchú Qing y huyeron al sudeste asiático (incluido Vietnam). La mayoría fueron recibidos por los señores Nguyễn para reasentarse en el sur de Vietnam y establecer negocios y comercio.

En 1782, Nguyễn Ánh escapó a Camboya y los Tây Sơn se apoderaron del sur de Vietnam (ahora Cochinchina). Habían discriminado a los chinos étnicos, disgustando a los chino-vietnamitas. Ese abril, los leales a Nguyễn Tôn Thất Dụ, Trần Xuân Trạch, Trần Văn Tự y Trần Công Chương enviaron apoyo militar a Ánh. El ejército de Nguyễn mató al gran almirante Phạm Ngạn, que tenía una estrecha relación con el emperador Thái Đức, en el puente de Tham Lương. [39] Thái Đức, enojado, pensó que los chinos étnicos habían colaborado en el asesinato. Saqueó la ciudad de Cù lao (actual Biên Hòa ), que tenía una gran población china, [40] [41] y ordenó la opresión de la comunidad china para vengar su ayuda a Ánh. Anteriormente se había producido una limpieza étnica en Hoi An , lo que llevó a que los chinos ricos apoyaran a Ánh. Regresó a Giồng Lữ, derrotó al almirante Nguyễn Học del Tây Sơn y capturó ochenta acorazados. Ánh luego comenzó una campaña para recuperar el sur de Vietnam, pero Nguyễn Huệ desplegó una fuerza naval en el río y destruyó su armada. Ánh volvió a escapar con sus seguidores a Hậu Giang . Camboya más tarde cooperó con Tây Sơn para destruir la fuerza de Ánh y lo hizo retirarse a Rạch Giá , luego a Hà Tiên y Phú Quốc .

Tras las derrotas consecutivas ante los Tây Sơn, Ánh envió a su general Châu Văn Tiếp a Siam para solicitar asistencia militar. Siam, bajo el gobierno de Chakri , quería conquistar Camboya y el sur de Vietnam. El rey Rama I aceptó aliarse con el señor Nguyễn e intervenir militarmente en Vietnam. Châu Văn Tiếp envió una carta secreta a Ánh sobre la alianza. Después de reunirse con los generales siameses en Cà Mau , Ánh, treinta oficiales y algunas tropas visitaron Bangkok para reunirse con Rama I en mayo de 1784. El gobernador de la provincia de Gia Định , Nguyễn Văn Thành , aconsejó a Ánh que no pidiera ayuda extranjera. [42] [43]

Rama I, temiendo la creciente influencia de la dinastía Tây Sơn en Camboya y Laos, decidió enviar su ejército contra ella. En Bangkok, Ánh comenzó a reclutar refugiados vietnamitas en Siam para que se unieran a su ejército (que sumaba más de 9000). [44] Regresó a Vietnam y preparó sus fuerzas para la campaña de Tây Sơn en junio de 1784, después de lo cual capturó Gia Định. Rama I nombró a su sobrino, Chiêu Tăng, como almirante el mes siguiente. El almirante dirigió fuerzas siamesas, incluidas 20 000 tropas de marina y 300 buques de guerra, desde el golfo de Siam hasta la provincia de Kiên Giang . Además, más de 30 000 tropas de infantería siamesa cruzaron la frontera camboyana hacia la provincia de An Giang . [45] El 25 de noviembre de 1784, el almirante Châu Văn Tiếp murió en batalla contra los Tây Sơn en el distrito de Mang Thít , provincia de Vĩnh Long . La alianza salió victoriosa en gran medida de julio a noviembre, y el ejército de los Tây Sơn se retiró al norte. Sin embargo, el emperador Nguyễn Huệ detuvo la retirada y contraatacó a las fuerzas siamesas en diciembre. En la batalla decisiva de Rạch Gầm–Xoài Mút, murieron más de 20.000 soldados siameses y el resto se retiró a Siam. [46]

Ánh, desilusionado con Siam, huyó a la isla de Thổ Chu en abril de 1785 y luego a la isla de Ko Kut en Tailandia. El ejército siamés lo escoltó de regreso a Bangkok, donde estuvo exiliado brevemente.

La guerra entre el señor Nguyễn y la dinastía Tây Sơn obligó a Ánh a buscar más aliados. Su relación con De Behaine mejoró y aumentó el apoyo a una alianza con Francia. Antes de la solicitud de asistencia militar siamesa, De Behaine estaba en Chanthaburi y Ánh le pidió que fuera a la isla Phú Quốc . [47] Ánh le pidió que contactara al rey Luis XVI de Francia para obtener ayuda; De Behaine aceptó coordinar una alianza entre Francia y Vietnam, y Ánh le dio una carta para presentar en la corte francesa. El hijo mayor de Ánh, Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh , fue elegido para acompañar a De Behaine. Debido al mal tiempo, el viaje se pospuso hasta diciembre de 1784. El grupo partió de la isla Phú Quốc hacia Malaca y de allí a Pondicherry , y Ánh trasladó a su familia a Bangkok. [48] El grupo llegó a Lorient en febrero de 1787 y Luis XVI aceptó reunirse con ellos en mayo.

El 28 de noviembre de 1787, Behaine firmó el Tratado de Versalles con el ministro francés de Asuntos Exteriores, Armand Marc, en el Palacio de Versalles en nombre de Nguyễn Ánh. [49] El tratado estipulaba que Francia proporcionaría cuatro fragatas, 1200 tropas de infantería, 200 artillerías, 250 cafres (soldados africanos) y otros equipos. Nguyễn Ánh cedió el estuario de Đà Nẵng y la isla de Côn Sơn a Francia. [50] A los franceses se les permitió comerciar libremente y controlar el comercio exterior en Vietnam. Vietnam tuvo que construir un barco por año que era similar al barco francés que traía ayuda y se la dio a Francia. Vietnam estaba obligado a suministrar alimentos y otra ayuda a Francia cuando los franceses estaban en guerra con otras naciones del este de Asia.

El 27 de diciembre de 1787, Pigneau de Behaine y Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh abandonaron Francia rumbo a Pondicherry para esperar el apoyo militar prometido por el tratado. Sin embargo, debido a la Revolución Francesa y la abolición de la monarquía francesa, el tratado nunca se ejecutó. Thomas Conway , quien era responsable de la asistencia francesa, se negó a proporcionarla. Aunque el tratado no se implementó, de Behaine reclutó a un empresario francés que tenía la intención de comerciar en Vietnam y recaudó fondos para ayudar a Nguyễn Ánh. Gastó quince mil francos de su propio dinero para comprar armas y buques de guerra. Cảnh y de Behaine regresaron a Gia Định en 1788 (después de que Nguyễn Ánh lo había recuperado), seguidos por un barco con el material de guerra. Entre los franceses que fueron reclutados se encontraban Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau , Philippe Vannier , Olivier de Puymanel y Jean-Marie Dayot . Un total de veinte personas se unieron al ejército de Ánh. Los franceses compraron y suministraron equipo y armamento, reforzando la defensa de Gia Định, Vĩnh Long, Châu Đốc, Hà Tiên, Biên Hòa, Bà Rịa y entrenando la artillería y la infantería de Ánh según el modelo europeo. [51]

En 1786, Nguyễn Huệ dirigió el ejército contra los señores Trịnh; Trịnh Khải escapó hacia el norte pero fue capturado por la población local. Luego se suicidó. Después de que el ejército de Tây Sơn regresó a Quy Nhơn, los súbditos del señor Trịnh restauraron a Trịnh Bồng (hijo de Trịnh Giang ) como el próximo señor. Lê Chiêu Thống , emperador de la dinastía Lê, quería recuperar el poder de manos de Trịnh. Convocó a Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, gobernador de Nghệ An, para atacar al señor Trịnh en la Ciudadela Imperial de Thăng Long . Trịnh Bồng se rindió a los Lê y se convirtió en monje. Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh quería unificar el país bajo el gobierno de los Lê y comenzó a preparar al ejército para marchar hacia el sur y atacar a los Tây Sơn. Huệ dirigió el ejército, mató a Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh y capturó a los Lê. La posterior capital de los Lê. La familia imperial de los Lê fue exiliada a China y la dinastía de los Lê se derrumbó.

En esa época, la influencia de Nguyễn Huệ se hizo más fuerte en el norte de Vietnam; esto hizo que el emperador Nguyễn Nhạc de la dinastía Tây Sơn sospechara de la lealtad de Huệ. La relación entre los hermanos se volvió tensa, lo que finalmente llevó a una batalla. Huệ hizo que su ejército rodeara la capital de Nhạc, en la ciudadela de Quy Nhơn, en 1787. Nhạc le rogó a Huệ que no lo matara, y se reconciliaron. En 1788, el emperador Lê Chiêu Thống huyó a China y pidió ayuda militar. El emperador Qianlong de la dinastía Qing ordenó a Sun Shiyi que liderara la campaña militar en Vietnam. La campaña fracasó y, más tarde, la dinastía Qing reconoció a la dinastía Tây Sơn como la dinastía legítima en Vietnam. Sin embargo, con la muerte de Huệ (1792), la dinastía Tây Sơn comenzó a debilitarse.

Ánh comenzó a reorganizar una fuerza armada fuerte en Siam. Abandonó Siam (después de agradecer al rey Rama I) y regresó a Vietnam. [52] [53] Durante la guerra de 1787 entre Nguyễn Huệ y Nguyễn Nhạc en el norte de Vietnam, Ánh recuperó la capital vietnamita meridional de Gia Định. El sur de Vietnam había sido gobernado por los Nguyễn y seguían siendo populares, especialmente entre los chinos étnicos. Nguyễn Lữ , el hermano menor de Tây Sơn (que gobernaba el sur de Vietnam), no pudo defender la ciudadela y se retiró a Quy Nhơn . La ciudadela de Gia Định fue tomada por los señores Nguyễn. [54]

En 1788, el hijo de De Behaine y Ánh, el príncipe Cảnh, llegó a Gia Định con equipo de guerra moderno y más de veinte franceses que querían unirse al ejército. La fuerza fue entrenada y reforzada con ayuda francesa. [55]

Después de la caída de la ciudadela de Gia Định, Nguyễn Huệ preparó una expedición para recuperarla antes de su muerte el 16 de septiembre de 1792. Su pequeño hijo, Nguyễn Quang Toản , lo sucedió como emperador de Tây Sơn y fue un líder pobre. [56] En 1793, Nguyễn Ánh inició una campaña contra Quang Toản. Debido al conflicto entre funcionarios de la corte de Tây Sơn, Quang Toản perdió batalla tras batalla. En 1797, Ánh y Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh atacaron Qui Nhơn (entonces en la provincia de Phú Yên ) en la batalla de Thị Nại. Salieron victoriosos y capturaron una gran cantidad de equipo Tây Sơn. [57] Quang Toản se volvió impopular debido a sus asesinatos de generales y oficiales, lo que llevó a una decadencia del ejército. En 1799, Ánh capturó la ciudadela de Quy Nhơn. Se apoderó de la capital ( Phú Xuân ) el 3 de mayo de 1801, y Quang Toản se retiró al norte. El 20 de julio de 1802, Ánh capturó Hanoi y, para poner fin a la dinastía Tây Sơn , todos los miembros de la dinastía Tây Sơn fueron capturados. Ánh ejecutó a todos los miembros de la dinastía Tây Sơn ese año.

En la historiografía vietnamita, el período independiente se conoce como el período Nhà Nguyễn thời độc lập . Durante este período, los territorios de la dinastía Nguyễn comprendían los territorios actuales de Vietnam y partes de la moderna Camboya y Laos , limitando con Siam al oeste y la dinastía manchú Qing al norte. Los emperadores gobernantes Nguyễn establecieron y dirigieron el primer sistema administrativo y burocrático imperial bien definido de Vietnam y anexaron Camboya y Champa a sus territorios en la década de 1830. Junto con Chakri Siam y Konbaung Burma , era una de las tres principales potencias del sudeste asiático en ese momento. [58] El emperador Gia Long fue relativamente amigable con las potencias occidentales y el cristianismo. Después de que su reinado de Minh Mạng trajera un nuevo enfoque, gobernó durante 21 años desde 1820 hasta 1841, como un gobernante conservador y confuciano ; Introdujo una política de aislacionismo que mantuvo al país aislado del resto del mundo durante casi 40 años hasta la invasión francesa en 1858. Minh Mạng reforzó el control sobre el catolicismo , los musulmanes y las minorías étnicas, lo que dio lugar a más de doscientas rebeliones en todo el país durante su reinado de veintiún años. También expandió aún más el imperialismo vietnamita en las actuales Laos y Camboya .

Los sucesores de Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị (r. 1841-1847) y Tự Đức (r. 1847-1883) se verían afectados por graves problemas que finalmente diezmaron el estado vietnamita. A fines de la década de 1840, Vietnam se vio afectado por la pandemia mundial de cólera que mató aproximadamente al 8% de la población del país, mientras que las políticas aislacionistas del país dañaron la economía. Francia y España declararon la guerra a Vietnam en septiembre de 1858. Frente a estas potencias industrializadas, la ermitaña dinastía Nguyễn y su ejército se desmoronaron, y la alianza capturó Saigón a principios de 1859. Siguieron una serie de tratados desiguales , primero el Tratado de Saigón de 1862 y luego el Tratado de Huế de 1863 , que dio a Francia acceso a los puertos vietnamitas y aumentó el control de sus asuntos exteriores. El Tratado de Saigón (1874) concluyó la anexión francesa de Cochinchina que había comenzado en 1862.

El último emperador independiente de Nguyễn fue Tự Đức. A su muerte, se produjo una crisis sucesoria , ya que el regente Tôn Thất Thuyết orquestó el asesinato de tres emperadores en un año. Esto presentó una oportunidad para los franceses. La corte de Huế se vio obligada a firmar la Convención de Harmand en septiembre de 1883, que formalizó la entrega de Tonkín a la administración francesa. Después de la firma del Tratado de Patenôtre en 1884, Francia terminó su anexión y partición de Vietnam en tres protectorados constituyentes de la Indochina francesa y convirtió a Nguyễn en una monarquía vasalla. [59] Finalmente, el Tratado de Tientsin (1885) entre el Imperio chino y la República Francesa se firmó el 9 de junio de 1885 reconociendo el dominio francés sobre Vietnam. [60] Todos los emperadores posteriores a Đồng Khánh fueron elegidos por los franceses y sólo gobernaron simbólicamente.

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh unificó Vietnam después de trescientos años de división del país. Celebró su coronación en Huế el 1 de junio de 1802 y se proclamó emperador ( en vietnamita : Hoàng Đế ), con el nombre de la era Gia Long (嘉隆). Este título enfatizaba su gobierno desde la región de "Gia" Định (hoy Saigón ) en el extremo sur hasta Thăng "Long" (hoy Hanoi ) en el norte. [61] Gia Long priorizó la defensa de la nación y trabajó para evitar otra guerra civil. Reemplazó el sistema feudal con una doctrina reformista del medio , basada en el confucianismo . [62] [63] La dinastía Nguyen fue fundada como un estado tributario del Imperio Qing, y Gia Long recibió un perdón imperial y el reconocimiento como gobernante de Vietnam del Emperador Jiaqing por reconocer la soberanía china . [1] [64] Los enviados enviados a China para adquirir este reconocimiento citaron el antiguo reino de Nanyue (vietnamita: Nam Việt ) al Emperador Jiaqing como el nombre del país, esto disgustó al emperador que estaba desconcertado por tales pretensiones, y Nguyễn Phúc Ánh tuvo que renombrar oficialmente su reino como Vietnam el año siguiente para satisfacer al emperador. [65] [61] El país era conocido oficialmente como 'El (Gran) estado vietnamita' ( vietnamita : Đại Việt Nam quốc), [66]

Gia Long afirmó que estaba reviviendo el estado burocrático que fue construido por el rey Lê Thánh Tông durante la edad de oro del siglo XV (1470-1497), como tal, adoptó un modelo de gobierno confuciano-burocrático y buscó la unificación con los literatos del norte. [67] Para asegurar la estabilidad en el reino unificado, colocó a dos de sus asesores más leales y educados en el confucianismo, Nguyễn Văn Thành y Lê Văn Duyệt como virreyes de Hanoi y Saigón. [68] De 1780 a 1820, aproximadamente 300 franceses sirvieron en la corte de Gia Long como funcionarios. [69] Al ver la influencia francesa en Vietnam con alarma, el Imperio británico envió dos enviados a Gia Long en 1803 y 1804 para convencerlo de que abandonara su amistad con los franceses. [70] En 1808, una flota británica liderada por William O'Bryen Drury montó un ataque en el delta del río Rojo, pero pronto fue rechazada por la armada vietnamita y sufrió varias pérdidas. Después de la Guerra Napoleónica y la muerte de Gia Long, el Imperio Británico reanudó las relaciones con Vietnam en 1822. [71] Durante su reinado, se estableció un sistema de carreteras que conectaban Hanoi, Hue y Saigón con estaciones postales y posadas, se construyeron y terminaron varios canales que conectaban el río Mekong con el golfo de Siam . [72] [73] En 1812, Gia Long emitió el Código de Gia Long, que se instituyó con base en el Código Ch'ing de China, reemplazó al Código anterior de 1480 de Thánh Tông. [74] [75] [69] En 1811, estalló un golpe de estado en el Reino de Camboya , un estado tributario vietnamita, lo que obligó al rey pro-vietnamita Ang Chan II a buscar el apoyo de Vietnam. Gia Long envió 13.000 hombres a Camboya, restaurando con éxito a su vasallo en su trono, [76] y comenzando una ocupación más formal del país durante los siguientes 30 años, mientras que Siam se apoderó del norte de Camboya en 1814. [77]

Gia Long murió en 1819 y fue sucedido por su cuarto hijo, Nguyễn Phúc Đảm , quien pronto fue conocido como el emperador Minh Mạng (r. 1820-1841) de Vietnam. [78]

Minh Mạng era el hermano menor del príncipe Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh y cuarto hijo del emperador Gia Long. Educado en los principios confucianos desde su juventud, [79] Minh Mạng se convirtió en emperador de Vietnam en 1820, durante un brote mortal de cólera que asoló y mató a 200.000 personas en todo el país. [80] Su reinado se centró principalmente en centralizar y estabilizar el estado, aboliendo el sistema virreinal e implementando una nueva administración basada en la burocracia provincial. [81] También detuvo la diplomacia con Europa y tomó medidas enérgicas contra las minorías religiosas. [82]

Minh Mạng evitó las relaciones con las potencias europeas. En 1824, tras la muerte de Jean Marie Despiau , ningún asesor occidental que hubiera servido a Gia Long permaneció en la corte de Minh Mạng. El último cónsul francés de Vietnam, Eugene Chaigneau, nunca pudo obtener una audiencia con Minh Mạng. Después de su partida, Francia cesó los intentos de contacto. [83] Al año siguiente lanzó una campaña de propaganda anticatólica , denunciando la religión como "viciosa" y llena de "enseñanzas falsas". En 1832 Minh Mạng convirtió el Principado Cham de Thuận Thành en una provincia vietnamita, la conquista final en una larga historia de conflicto colonial entre Cham y Vietnam . [84] Alimentaba coercitivamente con carne de lagarto y cerdo a los musulmanes Cham y con carne de vaca a los hindúes Cham en violación de sus religiones para asimilarlos por la fuerza a la cultura vietnamita. [85] La primera revuelta Cham por la independencia tuvo lugar en 1833-1834 cuando Katip Sumat , un mulá Cham que acababa de regresar a Vietnam desde La Meca, declaró una guerra santa ( yihad ) contra el emperador vietnamita. [86] [87] [88] [89] La rebelión no logró obtener el apoyo de la élite Cham y fue rápidamente reprimida por el ejército vietnamita. [90] Una segunda revuelta comenzó el año siguiente, liderada por un clérigo musulmán llamado Ja Thak con el apoyo de la antigua realeza Cham, la gente de las tierras altas y los disidentes vietnamitas. Minh Mạng aplastó sin piedad la rebelión de Ja Thak y ejecutó al último gobernante Cham Po Phaok The a principios de 1835. [91]

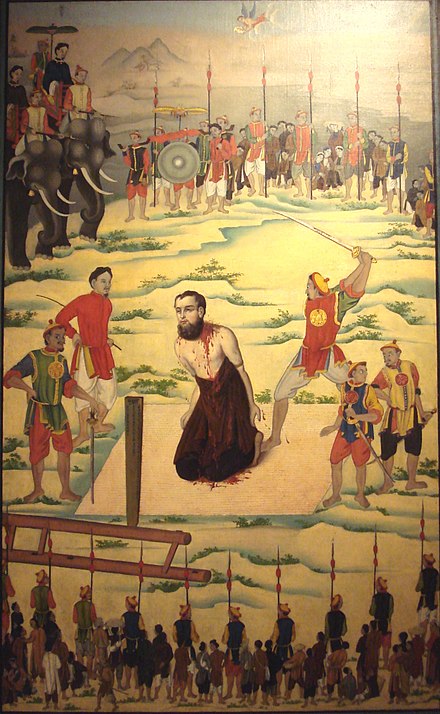

En 1833, cuando Minh Mạng había estado tratando de tomar el control firme sobre las seis provincias del sur, estalló una gran rebelión en Saigón liderada por Lê Văn Khôi (un hijo adoptivo del virrey de Saigón Lê Văn Duyệt ) , que intentaba colocar al hermano de Minh Mang, el príncipe Cảnh, en el trono. [92] La rebelión duró dos años, reuniendo mucho apoyo de los católicos vietnamitas, los jemeres, los comerciantes chinos en Saigón e incluso el gobernante siamés Rama III hasta que fue aplastada por las fuerzas gubernamentales en 1835. [93] [94] [84] En enero, emitió la primera prohibición del catolicismo en todo el país y comenzó a perseguir a los cristianos. [95] [96] 130 misioneros cristianos, sacerdotes y líderes de la iglesia fueron ejecutados, docenas de iglesias fueron quemadas y destruidas. [78]

Minh Mạng también expandió su imperio hacia el oeste, poniendo el centro y sur de Laos bajo la provincia de Cam Lộ, y chocó con el antiguo aliado de su padre, Siam , en Vientiane y Camboya. [97] [98] Apoyó la revuelta del rey laosiano Anouvong de Vientiane contra los siameses y se apoderó de Xam Neua y Savannakhet en 1827. [98]

En 1834, la Corona vietnamita anexó completamente Camboya y la renombró como provincia de Tây Thành . Minh Mạng nombró al general Trương Minh Giảng como gobernador de la provincia camboyana, expandiendo su asimilación religiosa forzosa al nuevo territorio. El rey Ang Chan II de Camboya murió al año siguiente y Ming Mang instaló a la hija de Chan, Ang Mey, como princesa comandante de Camboya. [99] Los funcionarios camboyanos debían usar ropa de estilo vietnamita y gobernar al estilo vietnamita. [100] Sin embargo, el gobierno vietnamita sobre Camboya no duró mucho y resultó agotador para la economía de Vietnam. [101] Minh Mạng murió en 1841, mientras se desarrollaba un levantamiento jemer con apoyo siamés, poniendo fin a la provincia de Tây Thành y al control vietnamita de Camboya. [102] [103]

Durante los siguientes cuarenta años, Vietnam fue gobernado por otros dos emperadores independientes: Thiệu Trị (1841-1847) y Tự Đức (1848-1883). Thiệu Trị o príncipe Miên Tông, era el hijo mayor del emperador Minh Mạng. Su reinado de seis años mostró una disminución significativa de la persecución católica. Con el rápido crecimiento de la población de 6 millones en la década de 1820 a 10 millones en 1850, [104] los intentos de autosuficiencia agrícola estaban resultando inviables. Entre 1802 y 1862, la corte se enfrentó a 405 revueltas pequeñas y grandes de campesinos, disidentes políticos, minorías étnicas y leales a Lê (personas que eran leales a la antigua dinastía Lê Duy) en todo el país, [105] esto hizo que responder al desafío de los colonizadores europeos fuera significativamente más desafiante.

En 1845, el buque de guerra estadounidense USS Constitution aterrizó en Đà Nẵng , tomando como rehenes a todos los funcionarios locales y exigiendo que Thiệu Trị liberara al obispo francés Dominique Lefèbvre , que se encontraba en prisión . [106] [107] [108] En 1847, Thiệu Trị había hecho las paces con Siam, pero el encarcelamiento de Dominique Lefèbvre ofreció una excusa para la agresión francesa y británica. En abril, la marina francesa atacó a los vietnamitas y hundió muchos barcos vietnamitas en Đà Nẵng, exigiendo la liberación de Lefèbvre. [109] [110] [111] Enfadado por el incidente, Thiệu Trị ordenó que se destruyeran todos los documentos europeos de su palacio y que todos los europeos capturados en tierras vietnamitas fueran ejecutados de inmediato. [112] En otoño, dos buques de guerra británicos de Sir John Davis llegaron a Đà Nẵng e intentaron forzar un tratado comercial con Vietnam, pero el emperador se negó. Murió unos días después de una apoplejía. [113]

Tự Đức , o príncipe Hồng Nhậm, era el hijo menor de Thiệu Trị, muy instruido en el saber confuciano, y fue coronado por el ministro y corregente Trương Đăng Quế. El príncipe Hồng Bảo , hermano mayor de Tự Đức y heredero primogénito, se rebeló contra Tự Đức el día de su ascenso al trono. [114] Este golpe fracasó, pero se libró de la ejecución gracias a la intervención de Từ Dụ , y su sentencia se redujo a cadena perpetua. [115] Consciente del auge de las influencias occidentales en Asia, Tự Đức confirmó la política aislacionista de su abuelo hacia las potencias europeas, prohibiendo las embajadas, el comercio y el contacto con extranjeros y renovando la persecución de los católicos que su abuelo había orquestado. [116] Durante los primeros doce años de Tự Đức, los católicos vietnamitas enfrentaron una dura persecución con 27 misioneros europeos, 300 sacerdotes y obispos vietnamitas y 30.000 cristianos vietnamitas ejecutados y crucificados entre 1848 y 1860. [112]

A finales de la década de 1840, otro brote de cólera azotó Vietnam, procedente de la India. La epidemia se propagó rápidamente sin control y mató a 800.000 personas (entre el 8 y el 10 % de la población de Vietnam en 1847) en todo el Imperio. [117] Las langostas plagaron el norte de Vietnam en 1854, y una importante rebelión al año siguiente dañó gran parte de la zona rural de Tonkín. Estas diversas crisis debilitaron considerablemente el control del imperio sobre Tonkín. [112]

En la década de 1850-70, una nueva clase de intelectuales liberales surgió en la corte a medida que la persecución se relajaba, muchos de ellos católicos que habían estudiado en el extranjero en Europa, más notablemente Nguyễn Trường Tộ , quien instó al emperador a reformar y transformar el Imperio siguiendo el modelo occidental y abrir Vietnam a Occidente. [118] A pesar de sus esfuerzos, los burócratas confucianos conservadores y el propio Tự Đức tenían un interés literal en tales reformas. [119] [120] La economía siguió siendo en gran parte agrícola, con el 95% de la población viviendo en áreas rurales, solo la minería ofrecía potencial a los sueños de los modernistas de un estado de estilo occidental.

En septiembre de 1858, Napoleón III organizó un bombardeo del ejército franco-español e invadió Đà Nẵng para protestar contra las ejecuciones de dos misioneros dominicos españoles. Siete meses después, navegaron hacia el sur para atacar Saigón y el rico delta del Mekong. [121] Las tropas de la Alianza mantuvieron Saigón durante dos años, mientras que una rebelión de los leales a Lê liderada por el obispo católico Pedro Tạ Văn Phụng , que se autoproclamó príncipe Lê, estalló en el norte y se intensificó. [122] [123] Junto con el pretexto de vengar la muerte de los misioneros, la invasión francesa fue diseñada para demostrar a Europa que Francia no era una potencia de segunda categoría y "civilizar" la zona. En febrero de 1861, llegaron refuerzos franceses y 70 buques de guerra liderados por el general Vassoigne y abrumaron las fortalezas vietnamitas. Ante la invasión de la Alianza y la rebelión interna, Tự Đức decidió ceder tres provincias del sur a Francia para hacer frente a la rebelión coincidente. [124] [125]

En junio de 1862 se firmó el Tratado de Saigón , que dio como resultado que Vietnam perdiera tres provincias del sur: Gia Định , Mỹ Tho y Biên Hòa, que se convirtieron en la base de la Cochinchina francesa . En el Tratado de Huế (1863), la isla de Poulo Condoræ permitiría el catolicismo, tres puertos estarían abiertos al comercio francés y el mar se abrió para permitir la expansión francesa en Kampuchea . y se exigió que se enviaran reparaciones de guerra a Francia. A pesar de los elementos religiosos de este tratado, Francia no intervendría en la revuelta cristiana en el norte de Vietnam , incluso con sus misioneros instándolos a hacerlo. Para la reina viuda, Từ Dụ, la corte y el pueblo, el tratado de 1862 fue una humillación nacional. Tự Đức envió una vez más una misión al emperador francés Napoleón III , en la que pidió que se revisara el tratado de 1862. En julio de 1864 se firmó otro borrador de tratado. Francia devolvió las tres provincias a Vietnam, pero aún conservaba el control sobre tres ciudades importantes: Saigón, Mỹ Tho y Thủ Dầu Một. [126] En 1866, Francia convenció a Tự Đức de entregar las provincias meridionales de Vĩnh Long, Hà Tiên y Châu Đốc. Phan Thanh Giản , el gobernador de las tres provincias, dimitió inmediatamente. Sin resistencia, en 1867, los franceses anexaron las provincias y centraron su atención en las provincias del norte. [127]

A finales de la década de 1860, piratas, bandidos y restos de la rebelión Taiping en China huyeron a Tonkín y convirtieron el norte de Vietnam en un foco de sus actividades de incursión. El estado vietnamita era demasiado débil para luchar contra los piratas. [128] Estos rebeldes chinos acabaron formando sus propios ejércitos mercenarios como lo habían hecho las Banderas Negras y cooperaron con los funcionarios vietnamitas locales para interferir en los intereses comerciales franceses. Mientras Francia buscaba adquirir Yunnan y Tonkín, cuando en 1873 un comerciante-aventurero francés llamado Jean Dupuis fue interceptado por la autoridad local de Hanoi, el gobierno francés de Cochinchina respondió enviando un nuevo ataque sin hablar con la corte de Hue. [129] Un ejército francés dirigido por Francis Garnier llegó a Tonkín en noviembre. Debido a que los administradores locales se habían aliado con las Banderas Negras y desconfiaban del gobernador de Hanoi, Nguyễn Tri Phương , a fines de noviembre, los leales franceses y Lê abrieron fuego contra la ciudadela vietnamita de Hanoi. Tự Đức envió de inmediato delegaciones para negociar con Garnier, pero el príncipe Hoàng Kế Viêm , gobernador de Sơn Tây , había reclutado a la milicia china de las Banderas Negras de Liu Yongfu para atacar a los franceses. [130] Garnier fue asesinado el 21 de diciembre por los soldados de las Banderas Negras en la batalla de Cầu Giấy . [131] Se alcanzó una negociación de paz entre Vietnam y Francia el 5 de enero de 1874. [132] Francia reconoció formalmente la independencia total de Vietnam de China; Francia pagaría las deudas españolas de Vietnam; la fuerza francesa devolvió Hanoi a los vietnamitas; El ejército vietnamita en Hanoi tuvo que disolverse y reducirse a una simple fuerza policial; se garantizó la total libertad religiosa y comercial; Vietnam se vio obligado a reconocer las seis provincias del sur como territorios franceses. [133] [134]

Tan solo dos años después del reconocimiento francés, Tự Đức envió una embajada a la China Qing en 1876 y reanudó la relación tributaria con los chinos (la última misión fue en 1849). En 1878, Vietnam reanudó las relaciones con Tailandia. [135] En 1880, Gran Bretaña, Alemania y España todavía estaban debatiendo el destino de Vietnam, y la embajada china en París rechazó abiertamente el acuerdo franco-vietnamita de 1874. En París, el primer ministro Jules Ferry propuso una campaña militar directa contra Vietnam para revisar el tratado de 1874. Debido a que Tự Đức estaba demasiado preocupado como para mantener a los franceses fuera de su imperio sin enfrentarse directamente a ellos, solicitó la ayuda de la corte china. En 1882, 30.000 tropas Qing inundaron las provincias del norte y ocuparon ciudades. Las Banderas Negras también habían regresado, juntas, colaborando con los funcionarios vietnamitas locales y acosando a las empresas francesas. En marzo, los franceses respondieron enviando una segunda expedición liderada por Henri Rivière al norte para lidiar con estos diversos problemas, pero tuvieron que evitar toda la atención internacional, particularmente de China. [136] El 25 de abril de 1882, Rivière tomó Hanoi sin encontrar ninguna resistencia. [137] [138] Tự Đức informó a la corte china que su estado tributario estaba siendo atacado. En septiembre de 1882, 17 divisiones chinas (200.000 hombres) cruzaron las fronteras chino-vietnamitas y ocuparon Lạng Sơn , Cao Bằng, Bac Ninh y Thái Nguyên, con el pretexto de defenderse de la agresión francesa. [139]

Con el apoyo del ejército chino y del príncipe Hoàng Kế Viêm, Liu Yongfu y las Banderas Negras decidieron atacar Rivière. El 19 de mayo de 1883, las Banderas Negras emboscaron y decapitaron a Rivière en la Segunda Batalla de Cầu Giấy . [140] Cuando la noticia de la muerte de Rivière llegó a Francia, hubo una protesta inmediata y demandas de una respuesta. El Parlamento francés votó rápidamente a favor de la conquista de Vietnam. Decenas de miles de refuerzos franceses y chinos llegaron al delta del río Rojo . [141]

Tự Đức murió el 17 de julio. [142] Los problemas de sucesión paralizaron temporalmente la corte. Uno de sus sobrinos, Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Ái, fue coronado emperador Dục Đức pero, sin embargo, fue encarcelado y ejecutado después de tres días por los tres poderosos regentes Nguyễn Văn Tường , Tôn Thất Thuyết y Tran Tien Thanh por razones desconocidas. El hermano de Tự Đức, Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Dật, sucedió el 30 de julio como emperador Hiệp Hòa. [143] El alto funcionario del Censorado de la corte, Phan Đình Phùng, denunció a los tres regentes por su manejo irregular de la sucesión de Tự Đức. Tôn Thất Thuyết criticó a Phan Đình Phùng y lo envió de la corte a su territorio natal, donde más tarde lideró una campaña nacionalista. movimiento de resistencia contra los franceses durante diez años. [144]

Para sacar a Vietnam de la guerra, Francia decidió tomar un asalto directo a la ciudad de Huế. El ejército francés se dividió en dos partes: la más pequeña bajo el mando del general Bouët se quedó en Hanoi y esperó refuerzos de Francia mientras que la flota francesa liderada por Amédée Courbet y Jules Harmand navegó hacia Thuận An , la puerta marítima de Huế el 17 de agosto. Harmand exigió a los dos regentes Nguyễn Văn Tường y Tôn Thất Thuyết que entregaran Vietnam del Norte, Vietnam del Norte-Centro ( Thanh Hoá , Nghệ An , Hà Tĩnh ) y la provincia de Bình Thuận a posesión francesa, y que aceptaran un residente francés en Huế que pudiera exigir audiencias imperiales. Envió un ultimátum a los regentes diciendo que "el nombre de Vietnam ya no existiría en la historia" si no cumplían con esto. [145] [146]

El 18 de agosto, los acorazados franceses comenzaron a bombardear las posiciones vietnamitas en la ciudadela de Thuận An. Dos días después, al amanecer, Courbet y los marines franceses desembarcaron en la costa. A la mañana siguiente, todas las defensas vietnamitas en Huế fueron abrumadas por los franceses. El emperador Hiệp Hòa envió al mandarín Nguyễn Thượng Bắc para negociar. [147]

El 25 de septiembre, dos funcionarios judiciales, Trần Đình Túc y Nguyễn Trọng Hợp firmaron un tratado de veintisiete artículos conocido como Convención Harmand . [148] A los franceses se les concedió Bình Thuận; Đà Nẵng y Qui Nhơn se abrieron al comercio; la esfera gobernante de la monarquía vietnamita se redujo al Vietnam central, mientras que el norte de Vietnam se convirtió en un protectorado francés. En noviembre, el emperador Hiệp Hòa y Trần Tiễn Thành fueron ejecutados por Nguyễn Văn Tường y Tôn Thất Thuyết por sus supuestas simpatías profrancesas. Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Đăng, de 14 años, fue coronado emperador Kiến Phúc . Después de lograr la paz con China mediante el Acuerdo de Tientsin en mayo de 1884, el 6 de junio el embajador francés en China, Jules Patenôtre des Noyers, firmó con Nguyen Van Tuong el Tratado de Protectorado de Patente , que confirmó el dominio francés sobre Vietnam. [149] [59] El 31 de mayo de 1885, Francia nombró al primer gobernador de todo Vietnam. [150] El 9 de junio de 1885, Vietnam dejó de existir después de 83 años como estado independiente. [60] El líder de la facción pro-guerra, Tôn Thất Thuyết y sus partidarios se rebelaron contra los franceses en julio de 1885, pero se vieron obligados a retirarse a las tierras altas de Laos con el joven emperador Hàm Nghi (Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Lịch). Mientras tanto, Los franceses instalaron a su hermano pro-francés Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Kỷ como emperador Đồng Khánh . [151] Thuyết convocó a la nobleza, los leales y los nacionalistas a armarse para la resistencia contra la ocupación francesa ( movimiento Cần Vương ). [152] El movimiento duró 11 años (1885-1896) y Thuyết se vio obligado a exiliarse en China en 1888. [153]

El Tratado de Huế de 1883 llevó al resto de Vietnam a convertirse en protectorados franceses, divididos en los Protectorados de Annam y Tonkín . Sin embargo, los términos fueron considerados demasiado duros en los círculos diplomáticos franceses y nunca fueron ratificados en Francia. El siguiente Tratado de Huế de 1884 proporcionó una versión suavizada del tratado anterior. [154] El Tratado de Tientsin de 1885 , que reafirmó el Acuerdo de Tientsin de 1884 y puso fin a la guerra chino-francesa , confirmó el estatus de Vietnam como protectorado francés y cortó la relación tributaria de Vietnam con la dinastía Qing al requerir que todos los asuntos exteriores de Vietnam se llevaran a cabo a través de Francia. [155]

Después de esto, la dinastía Nguyễn solo gobernó nominalmente los dos protectorados franceses. Annam y Tonkín se fusionaron con Cochinchina y el protectorado camboyano vecino en 1887 para formar la Unión de la Indochina Francesa , de la que se convirtieron en componentes administrativos. [154]

El dominio francés también reforzó los ingredientes que los portugueses ya habían añadido al guiso cultural de Vietnam: el catolicismo y un alfabeto basado en el latín . La ortografía utilizada en la transliteración vietnamita está de hecho basada en el portugués, porque los franceses se basaron en un diccionario compilado anteriormente por un clérigo portugués, Francisco de Pina . [154] Debido a su presencia en Macao , los portugueses también fueron los que trajeron el catolicismo a Vietnam en el siglo XVI, aunque fueron los franceses quienes construyeron la mayoría de las iglesias y establecieron misiones en el país. [156] [157]

Mientras intentaba maximizar el uso de los recursos naturales y la mano de obra de Indochina para luchar en la Primera Guerra Mundial, Francia reprimió los movimientos patrióticos de masas de Vietnam. Indochina (principalmente Vietnam) tuvo que proporcionar a Francia 70.000 soldados y 70.000 trabajadores, que fueron reclutados a la fuerza desde las aldeas para servir en el frente de batalla francés. Vietnam también contribuyó con 184 millones de piastras en préstamos y 336.000 toneladas de alimentos.

Estas cargas resultaron pesadas, ya que la agricultura sufrió desastres naturales entre 1914 y 1917. A falta de una organización nacional unificada, el vigoroso movimiento nacional vietnamita no supo aprovechar las dificultades que tenía Francia como resultado de la guerra para organizar levantamientos significativos.

En mayo de 1916, el emperador Duy Tân, de dieciséis años, escapó de su palacio para participar en un levantamiento de las tropas vietnamitas. Los franceses fueron informados del plan y sus líderes fueron arrestados y ejecutados. Duy Tân fue depuesto y exiliado a la isla de Reunión , en el océano Índico.

El sentimiento nacionalista se intensificó en Vietnam (especialmente durante y después de la Primera Guerra Mundial), pero los levantamientos y los intentos de conseguir concesiones de los franceses no lograron éxito. La Revolución rusa tuvo un gran impacto en la historia vietnamita del siglo XX.

Para Vietnam, el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial el 1 de septiembre de 1939 fue tan decisivo como la toma de Đà Nẵng por parte de Francia en 1858. La potencia del Eje , Japón, invadió Vietnam el 22 de septiembre de 1940, intentando construir bases militares para atacar a las fuerzas aliadas en el sudeste asiático. Esto condujo a un período de Indochina bajo ocupación japonesa con la cooperación de los franceses de Vichy , que aún conservaban la administración de la colonia. Durante este tiempo, el Viet Minh , un movimiento de resistencia comunista, se desarrolló bajo Ho Chi Minh a partir de 1941, con el apoyo de los aliados . Durante la hambruna de 1944-1945 en el norte de Vietnam , más de un millón de personas murieron de hambre.

En marzo de 1945, después de la liberación de Francia y fuertes reveses en la guerra, los japoneses en un último esfuerzo por reunir apoyo en Indochina derrocaron a la administración francesa , encarcelaron a sus funcionarios públicos y proclamaron la independencia de Camboya , Laos y Vietnam, que se convirtió en el Imperio de Vietnam con Bảo Đại como su Emperador. [5] [6] El Imperio de Vietnam era un estado títere del Imperio de Japón . [5] Después de la rendición de Japón , Bảo Đại abdicó el 25 de agosto de 1945 después de que el Viet Minh lanzara la Revolución de Agosto . [158]

Esto puso fin al reinado de 143 años de la dinastía Nguyễn.

La dinastía Nguyễn mantuvo el sistema burocrático y jerárquico de las dinastías anteriores. El emperador era el jefe de estado que ejercía autoridad absoluta. Bajo el emperador estaba el Ministerio del Interior (que trabajaba en documentos, mensajes imperiales y registros) y cuatro Grandes Secretariados ( en vietnamita : Tứ trụ Đại thần ), posteriormente rebautizados como Ministerio del Consejo Secreto. [159] [160] [161]

El emperador de la dinastía Nguyễn era un gobernante absolutista , lo que significa que era tanto jefe de estado como jefe de gobierno . [162] El Código Gia Long de 1812 declaró al monarca vietnamita como gobernante universal de todo Vietnam; utilizando el concepto confuciano del Mandato del Cielo para proporcionar a los monarcas un poder absoluto. Su reinado e imágenes populares se juzgaban en función de lo próspero que fuera el sustento (民生, dân sinh ) del pueblo y el concepto confuciano de chính danh (rectificación de nombres), según las Analectas bíblicas confucianas , todo tiene que permanecer en su orden correcto. [163] [164] Gia Long también percibió la antigua concepción china de Hua-Yi y en 1805 confesó su Imperio como Trung Quốc (中國, "el Reino Medio "), el término vietnamita que a menudo se refiere a China pero que ahora fue utilizado por Gia Long para enfatizar su estatus de Hijo del Cielo y la devaluación de China. [165] [166] Después de las siguientes décadas, el confucianismo y la teoría del Mandato del Cielo gradualmente perdieron sus posiciones entre los funcionarios e intelectuales vietnamitas. Cuando el cuarto emperador, Tự Đức, cedió el sur de Vietnam a Francia y llamó a todos los funcionarios del sur a entregar las armas, muchos ignoraron, desobedecieron al Hijo del Cielo y continuaron luchando contra los invasores. Muchos disidentes lo vieron como un rendidor y temeroso de Francia. Las rebeliones contra Tự Đức estallaron todos los años desde 1860 hasta su muerte en 1883. [167]

En Vietnam existía una teoría dual de la soberanía. A todos los monarcas Nguyễn se les llamaba hoàng đế (黃帝, título chino-vietnamita para "Emperador") en la corte mientras que él se refería a sí mismo como la primera persona honorífica trẫm (el que da la orden). También utilizaban el concepto de thiên tử (天子, " Hijo del Cielo ", que se tomó prestado de China) para demostrar que el gobernante descendía y era comisionado por el cielo para gobernar el reino. [163] Sin embargo, en la mayoría de los casos, los gobernantes Nguyen eran llamados formalmente vua (𪼀, el título vietnamita para "monarca" o "gobernante soberano") por la gente común vietnamita. [168] [169] El concepto de un Hijo del Cielo divino no se ha practicado dogmáticamente, y la divinidad del monarca no era absoluta debido a la teoría dual. Por ejemplo, Xu Jiyu , un geógrafo chino, informó que los burócratas de la corte vietnamita se sentaban e incluso se sentían libres de buscarse piojos en el cuerpo durante las audiencias de la corte. Gia Long le dijo una vez al hijo de JB Chaigneau, uno de sus asesores, que el uso del Hijo del Cielo en Vietnam era un "absurdo" y "al menos en la Compañía mixta vietnamita-europea". [169] Una vez que el joven príncipe heredero es elegido para suceder, su obligación es ser filial con sus padres, estar bien educado en política y clásicos e interiorizar la moral y la ética de un gobernante. [170]

Después de la firma del Tratado de Huế de 1884, la dinastía Nguyễn se convirtió en dos protectorados de Francia y los franceses instalaron a sus propios administradores. [171] Aunque los emperadores de la dinastía Nguyễn todavía controlaban nominalmente los protectorados de Annam y Tonkín, el Residente Superior de Annam gradualmente ganó más influencia sobre la corte imperial en Huế . [171] En 1897, al Residente Superior se le otorgó el poder de nombrar a los emperadores de la dinastía Nguyễn y presidió las reuniones del Viện cơ mật . [171] Estas medidas incorporaron a los funcionarios franceses directamente a la estructura administrativa de la Corte Imperial de Huế y legitimaron aún más el gobierno francés en la rama legislativa del gobierno Nguyễn. [171] A partir de este período, todos los edictos imperiales emitidos por los emperadores de Đại Nam tenían que ser confirmados por el Superior Residente de Annam, lo que le otorgaba poder legislativo y ejecutivo sobre el gobierno de Nguyễn. [171]

En el año 1898, el gobierno federal de la Indochina francesa se hizo cargo de las tareas de gestión financiera y de la propiedad de la corte imperial de la dinastía Nguyễn, lo que significó que el emperador de la dinastía Nguyễn (en ese momento Thành Thái ) se convirtió en un empleado asalariado de la estructura colonial indochina, reduciendo su poder a ser solo un funcionario del gobierno del Protectorado. [171] El Superior Residente de Annam también se hizo cargo de la gestión de los mandarines provinciales y fue miembro del Consejo Supremo ( Conseil supérieur ) del Gobierno General de la Indochina Francesa. [171]

La subunidad monetaria de Vietnam era el quan (貫). Un quan equivalía a 10 monedas, equivalentes a ₫ 600. En 1839, el emperador Minh Mạng determinó que los funcionarios recibieran los siguientes impuestos ( vietnamita : thuế đầu người ): [172]

Los funcionarios del primer al tercer rango recibían impuestos dos veces al año, mientras que los del cuarto al séptimo rango recibían impuestos al final de las cuatro estaciones. Los funcionarios del octavo y noveno rango lo hacían todos los meses del año. [173] El Emperador también otorgaba un dinero anual "dưỡng liêm" para prevenir la corrupción entre los administradores regionales. [174]

Cuando los mandarines se jubilaban, podían recibir entre cien y cuatrocientos quan del emperador. Cuando morían, la corte imperial proporcionaba entre veinte y doscientos quan para un funeral. [ cita requerida ]

Durante el reinado de Gia Long, el reino se dividió en veintitrés protectorados cuasi militantes y cuatro departamentos militares . [175] Cada protectorado, además de tener sus propios gobiernos regionales separados, estaba bajo la patrulla de una unidad mayor y poderosa llamada Señor Supremo de la Ciudadela o Virrey . Por ejemplo, los protectorados del norte tenían al Bắc thành Tổng trấn (Virrey de los Protectorados del Norte) en Hanoi, y los protectorados del sur tenían al Gia Định thành Tổng trấn (Virrey de los Protectorados de Gia Định) que residía en Saigón . [176] Dos virreyes famosos durante el reinado de Gia Long fueron Nguyễn Văn Thành (Hanoi) y Lê Văn Duyệt (Saigón). En 1802, estos eran:

En 1831, Minh Mạng reorganizó su reino convirtiendo todos estos protectorados en 31 provincias ( tỉnh ). Cada provincia tenía una serie de jurisdicciones más pequeñas: la prefectura ( phủ ), la subprefectura ( châu , en áreas que tenían una población significativa de minorías étnicas). Bajo la prefectura y la subprefectura, estaba el distrito ( huyện ) y el cantón ( tổng ). Bajo el distrito y el cantón, el conjunto de aldeas alrededor de un templo religioso común o un punto de factor social, la aldea (làng o la comuna xã ) era la unidad administrativa más baja, de la que una persona respetada se encargaba nominalmente de la administración de la aldea, que se llamaba lý trưởng. [177]

Dos provincias cercanas se combinaron en un par. Cada par tenía un gobernador general ( Tổng đốc ) y un gobernador ( Tuần phủ ). [178] Con frecuencia, había doce gobernadores generales y once gobernadores, aunque, en algunos períodos, el Emperador designaba un "comisionado a cargo de las fronteras patrulladas" ( kinh lược sứ ) que supervisaba toda la parte norte y sur del reino. [179] En 1803, Vietnam tenía 57 prefecturas, 41 subprefecturas, 201 distritos, 4136 cantones y 16 452 aldeas, y luego, en la década de 1840, se había incrementado a 72 prefecturas, 39 subprefecturas y 283 distritos, con un promedio de 30 000 personas por distrito. [177] Camboya había sido absorbida por el sistema administrativo vietnamita, y llevó el nombre de provincia de Tây Thành desde 1834 hasta 1845. [180] En áreas con grupos minoritarios como Tày , Nùng , Mèo ( pueblo hmong ), Mường , Mang y Jarai , la corte de Huế impuso el sistema de gobierno tributario y cuasi burocrático coexistente, al tiempo que permitía a estas personas tener sus propios gobernantes locales y autonomía. [181]

En 1832 había:

La dinastía Nguyễn consideraba a las culturas que no eran chinas como bárbaras y se autodenominaban Reino Central (Trung Quốc, 中國). [184] Esto incluye a los chinos Han bajo la dinastía Qing, que eran considerados como "no chinos". Los Qing hicieron que los chinos ya no fueran "Han". A los chinos se les llamaba "Thanh nhân" (清人) . Esto ocurrió después de que Vietnam enviara un delegado a Pekín, tras lo cual un desastre diplomático hizo que Vietnam considerara a otros "no chinos" como bárbaros de la misma manera que los Qing. [185] Durante la dinastía Nguyễn , los propios vietnamitas ordenaron a los jemeres camboyanos que adoptaran la cultura vietnamita dejando de lado hábitos "bárbaros" como cortarse el pelo y ordenándoles que lo dejaran crecer, además de obligarlos a reemplazar las faldas por pantalones. [186] Los refugiados chinos Han de la dinastía Ming, que sumaban 3.000, llegaron a Vietnam al final de la dinastía Ming. Se opusieron a la dinastía Qing y fueron ferozmente leales a esta última. Las mujeres vietnamitas se casaron con estos refugiados chinos Han, ya que la mayoría de ellos eran soldados y hombres solteros. No llevaban el peinado manchú a diferencia de los inmigrantes chinos posteriores a Vietnam durante la dinastía Qing . [187]

Bajo el emperador Minh Mạng, la sinización de las minorías étnicas se convirtió en política de estado. Reivindicó el legado del confucianismo y de la dinastía Han de China para Vietnam, y utilizó el término "pueblo Han" (漢人, Hán nhân ) para referirse a los vietnamitas. [188] [189] Según el emperador, "Debemos esperar que sus hábitos bárbaros se disipen inconscientemente y que cada día se infecten más con las costumbres Han [chino-vietnamitas]". [190] Estas políticas estaban dirigidas a los jemeres y las tribus de las montañas . [191] Nguyễn Phúc Chu se había referido a los vietnamitas como "pueblo Han" en 1712, distinguiéndolos de los chams. [192] Los señores Nguyễn establecieron colonias después de 1790. Gia Long dijo: "Hán di hữu hạn" (漢 夷 有 限, "Los vietnamitas y los bárbaros deben tener fronteras claras"), distinguiendo a los jemeres de los vietnamitas. [193] Minh Mang implementó una política de aculturación para los pueblos minoritarios no vietnamitas. [194] "Thanh nhân" (清 人 refiriéndose a la dinastía Qing ) o "Đường nhân" (唐人 refiriéndose a la dinastía Tang ) fueron utilizados para referirse a los chinos étnicos por los vietnamitas, quienes se llamaban a sí mismos "Hán dân" (漢 民) y "Hán nhân" (漢人 refiriéndose a la dinastía Han ) durante el gobierno Nguyễn del siglo XIX. [195] Desde 1827, los descendientes de los refugiados de la dinastía Ming fueron llamados Minh nhân (明人) o Minh Hương (明 鄉) por los gobernantes Nguyễn, para distinguirlos de los chinos étnicos. [196] Los minh nhân fueron tratados como vietnamitas desde 1829. [197] [198] : 272 No se les permitió ir a China, y tampoco se les permitió usar la cola manchú . [199]

La dinastía Nguyễn popularizó la vestimenta con influencia Qing . [200] [201] [202] [203] [204] [205] Los pantalones fueron adoptados por las mujeres hablantes de H'mong Blanco , [206] reemplazando sus faldas tradicionales. [207] Las túnicas y pantalones con influencia Qing fueron usados por los vietnamitas. El áo dài fue desarrollado en la década de 1920, cuando se agregaron pliegues compactos y ajustados al predecesor del áo dài, el áo ngũ thân. [208] Los pantalones y túnicas de influencia china fueron ordenados por el señor Nguyễn Phúc Khoát durante el siglo XVIII, reemplazando al tradicional áo tràng vạt vietnamita derivado del jiaoling youren chino (chino: 交領右衽). [209] Aunque los pantalones y túnicas de influencia china fueron ordenados por el gobierno de Nguyen, se usaron faldas en aldeas aisladas del norte de Vietnam hasta la década de 1920. [210] Nguyễn Phúc Khoát encargó ropa de estilo chino para los militares y burócratas vietnamitas . [211]

Una polémica de 1841 , "Sobre la distinción de los bárbaros", se basó en el letrero Qing "Albergue de bárbaros vietnamitas" (越夷會館) en la residencia de Fujian del diplomático Nguyen y chino Hoa Lý Văn Phức. [212] [213] [214] [215] Argumentaba que los Qing no suscribían los textos neoconfucianistas de las dinastías Song y Ming que aprendieron los vietnamitas, [216] quienes se veían a sí mismos como compartiendo una civilización con los Qing. [217] Este evento desencadenó un desastre diplomático. La consecuencia fue que las tribus de las tierras altas chinas no "Han" y otros pueblos no vietnamitas que vivían cerca (o en) Vietnam fueron llamados "bárbaros" por la corte imperial vietnamita. [218] [219] El ensayo distingue a los Yi y Hua, y menciona a Zhao Tuo, Wen, Shun y Taibo. [220] Kelley y Woodside describieron el confucianismo de Vietnam. [221]

Los emperadores Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị y Tự Đức se opusieron a la intervención francesa en Vietnam y trataron de reducir la creciente comunidad católica del país . El encarcelamiento de misioneros que habían entrado ilegalmente en el país fue el principal pretexto de los franceses para invadir (y ocupar) Indochina . Al igual que la China Qing, una serie de incidentes involucraron a otras naciones europeas durante el siglo XIX.

Aunque los señores Nguyễn anteriores eran fieles budistas , Gia Long no lo era. Adoptó el neoconfucianismo y restringió activamente el budismo. Los eruditos, las élites y los funcionarios atacaron las doctrinas budistas y las criticaron por supersticiosas e inútiles. El tercer emperador, Thiệu Trị , elevó el confucianismo a la categoría de religión verdadera, aunque consideró que el budismo era una superstición. [222]

Se prohibió la construcción de nuevas pagodas y templos budistas. Se obligó a los clérigos y monjas budistas a unirse a las obras públicas para limitar la influencia del budismo y promover el confucianismo como la única creencia dominante de la sociedad. Sin embargo, la adopción de una cultura confuciana sínica entre la población vietnamita que vivía en medio de una infraestructura del sudeste asiático, amplió la distancia entre la población y la corte lejana. [223] El budismo todavía prevalecía en la sociedad dominante y tenía su presencia dentro del palacio imperial. Las emperatrices madres, las reinas, las princesas y las concubinas eran budistas devotas, a pesar de la prohibición patriarcal.

El confucianismo en sí era la ideología de la corte de Nguyen, también proporcionaba el núcleo básico de la educación clásica y el examen civil cada año. Gia Long siguió el confucianismo para crear y mantener una sociedad y estructuras sociales conservadoras . Los rituales e ideas confucianos circulaban basados en la enseñanza confuciana antigua, como Las Analectas y Anales de Primavera y Otoño en colecciones de escritura vietnamita. [224] La corte importaba rígidamente estos libros chinos de los comerciantes chinos. Rituales confucianos como cầu đảo (ofrenda al cielo por el viento y la lluvia durante una sequía) que el emperador y los funcionarios de la corte realizan para desear que el cielo lloviera sobre su reino. [225] Si la oferta tenía éxito, tenían que realizar lễ tạ (ritual de acción de gracias) al cielo. Además, el emperador creía que los espíritus santos y las diosas naturales de su país también podían hacer llover. En 1804, Gia Long construyó el Templo Nam Hải Long Vương (Templo del Rey Dragón del Océano Austral) en Thuận An, al noreste de Hue, en su fidelidad al dios de Thuận An ( Thần Thuận An ), el lugar donde se realizaba la mayor parte del ritual cầu đảo . [226] Su sucesor, Minh Mạng, continuó construyendo varios templos dedicados al Vũ Sư (dios de la lluvia) y altares para Thần Mây (dios de las nubes) y Thần Sấm (dios del trueno). [227]

Nguyễn Trường Tộ , un destacado intelectual católico y reformista, lanzó un ataque contra las estructuras confucianas en 1867 por considerarlas decadentes. Escribió a Tự Đức: "el mal que ha traído a China y a nuestro país el estilo de vida confuciano". Criticó la educación confuciana de la corte por dogmática y poco realista, promovida para su reforma educativa. [228]

Durante los años de Gia Long, el catolicismo se practicaba pacíficamente sin ninguna restricción. Comenzó con Minh Mạng, quien consideraba al cristianismo como una religión heterodoxa por su rechazo al culto a los antepasados, la importante creencia de la monarquía vietnamita. Después de leer la Biblia (Antiguo y Nuevo Testamento), consideró que la religión cristiana era irracional y ridícula, y elogió al Japón Tokugawa por sus notorias políticas sobre los cristianos. Minh Mạng también estuvo influenciado por la propaganda anticristiana escrita por funcionarios y literatos confucianos vietnamitas, que describía la mezcla de hombres y mujeres y la sociedad liberal dentro de la Iglesia. Lo que más le preocupaba del cristianismo y el catolicismo era escribir textos que demostraran que el cristianismo era un medio para que los europeos se apoderaran de países extranjeros. También elogió la política anticristiana en Japón. [229] Las iglesias fueron destruidas y muchos cristianos fueron encarcelados. La persecución se intensificó durante el reinado de su nieto Tự Đức , cuando la mayoría de los esfuerzos del estado fueron para aniquilar el cristianismo vietnamita. Irónicamente, incluso durante el apogeo de la campaña anticatólica, a muchos eruditos católicos todavía se les permitía ocupar altos cargos en la corte imperial.

A finales de 1862, tras un edicto imperial, el catolicismo fue reconocido oficialmente y los fieles de la fe obtuvieron protección estatal. Se calcula que a finales del siglo XIX Vietnam contaba con entre 600.000 y 700.000 cristianos católicos.

.jpg/440px-Family(1).jpg)

Antes de la conquista francesa, la población vietnamita era muy escasa debido a la economía agrícola del país. La población en 1802 era de 6,5 millones de personas y solo había crecido a 8 millones en 1840. [230] La rápida industrialización después de la década de 1860 marcó el comienzo de un crecimiento masivo de la población y una rápida urbanización a fines del siglo XIX. Muchos campesinos abandonaron las granjas arrendatarias y se mudaron a las ciudades, donde fueron contratados por fábricas de propiedad francesa. En 1880, se estimaba que los vietnamitas eran en ese entonces tan altos como 18 millones de personas, [231] mientras que las estimaciones modernas de Angus Maddison han sugerido una cifra menor de 12,2 millones de personas. [232] Vietnam bajo la dinastía Nguyễn siempre fue un complejo multiétnico. Casi el 80% de la población del Imperio era étnicamente vietnamita (llamados annamitas en aquel entonces), [233] cuya lengua pertenecía a la familia mon-jemer (mon-anamita en aquel entonces), [234] y el resto eran cham , chinos , jemeres , mường , tày (llamados Thô en aquel entonces) y otras 50 minorías étnicas como los mang , jarai y yao. [235]

.jpg/440px-Childrens_(1).jpg)

Los annamitas se distribuyen por las tierras bajas del país desde Tonkín hasta Cochichina. Los chams viven en el centro de Vietnam y el delta del Mekong. Los chinos se concentraron particularmente en áreas urbanizadas como Saigón, Chợ Lớn y Hanoi. [236] Los chinos tendían a dividirse en dos grupos llamados Minh Hương (明鄉) y Thanh nhân (清人). [237] Los Minh Hương eran refugiados chinos que habían emigrado y se habían establecido en Vietnam a principios del siglo XVII, que se casaron con mujeres vietnamitas, se habían asimilado sustancialmente a las poblaciones vietnamitas y jemeres locales y eran leales a los nguyen, [238] en comparación con los thanh nhân que habían llegado recientemente al sur de Vietnam, dominaban el comercio del arroz. Durante el reinado de Minh Mạng, en 1827 se emitió una restricción contra los Thanh nhân, que no podían acceder a la burocracia estatal y tenían que integrarse en la población vietnamita como los Minh Hương. [239]

El pueblo Mường habitaba las colinas al oeste del delta del río Rojo y, aunque estaba subordinado a la autoridad central, se le permitía portar armas, un privilegio que no se concedía a ningún otro súbdito de la corte de Huế. Los Tày y los Mang vivían en las tierras altas del norte de Tonkín, ambos sometidos a la corte de Huế junto con los impuestos y tributos, pero se les permitía tener sus jefes hereditarios. [240]

Las primeras fotografías de Vietnam fueron tomadas por Jules Itier en Danang , en 1845. [241] Las primeras fotos de los vietnamitas fueron tomadas por Fedor Jagor en noviembre de 1857 en Singapur. [242] Debido al contacto prohibido con extranjeros, la fotografía regresó a Vietnam nuevamente durante la conquista francesa y Paul Berranger tomó fotografías durante la invasión francesa de Da Nang (septiembre de 1858). [243] Desde la toma francesa de Saigón en 1859, la ciudad y el sur de Vietnam se habían abierto a los extranjeros, y la fotografía entró a Vietnam exclusivamente desde Francia y Europa. [244]

La Casa de Nguyễn Phúc (Nguyen Gia Mieu) se fundó históricamente en el siglo XIV en la aldea de Gia Miêu, provincia de Thanh Hóa , antes de que gobernaran el sur de Vietnam desde 1558 hasta 1777, convirtiéndose luego en la dinastía gobernante de todo Vietnam. Tradicionalmente, la familia se remonta a Nguyễn Bặc (?–979), el primer duque de Đại Việt. Los príncipes y descendientes masculinos de Gia Long se llaman Hoàng Thân, mientras que los descendientes lineales masculinos de los señores Nguyen anteriores se llaman Tôn Thất . Los nietos del emperador eran Hoàng tôn. Las hijas del emperador se llamaban Hoàng nữ, y siempre ganaban el título de công chúa (princesa).

Su sucesión prácticamente se realiza según la ley de primogenitura, pero a veces entra en conflicto. El primer conflicto sucesorio surgió en 1816 cuando Gia Long estaba planeando un heredero. Su primer príncipe Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh murió en 1802. Como resultado, surgieron dos facciones rivales, una apoyaba a Nguyễn Phúc Mỹ Đường , el hijo mayor del príncipe Cảnh, como príncipe heredero, mientras que la otra apoyaba al príncipe Đảm (más tarde Minh Mang). [245] El segundo conflicto fue la sucesión de 1847 cuando dos jóvenes príncipes Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Bảo y Hồng Nhậm fueron arrastrados por el emperador Thiệu Trị como heredero potencial. Al principio, Thiệu Trị aparentemente eligió al príncipe Hồng Bảo porque era mayor, pero después de escuchar el consejo de dos regentes, Trương Đăng Quế y Nguyễn Tri Phương , revisó al heredero en el último minuto y eligió a Hồng Nhậm como príncipe heredero. [246]

La siguiente lista contiene los nombres de las eras de los emperadores , que tienen significado en chino y vietnamita. Por ejemplo, el nombre de la era del primer gobernante, Gia Long, es la combinación de los antiguos nombres de Saigón (Gia Định) y Hanoi (Thăng Long) para mostrar la nueva unidad del país; el cuarto, Tự Đức, significa "Herencia de Virtudes"; el noveno, Đồng Khánh, significa "Celebración Colectiva".

Tras la muerte del emperador Tự Đức (y según su testamento), Dục Đức ascendió al trono el 19 de julio de 1883. Fue destronado y encarcelado tres días después, tras ser acusado de borrar un párrafo del testamento de Tự Đức. Sin tiempo para anunciar su título dinástico, su nombre de era fue bautizado con el nombre de su palacio residencial.

Nota :

Árbol genealógico simplificado de la dinastía Nguyen Phuc:

La bandera nacional de la dinastía Nguyễn o la bandera imperial apareció por primera vez durante el reinado de Gia Long . Era una bandera amarilla con una o tres franjas rojas horizontales, a veces en 1822, era completamente amarilla o blanca. [248] La bandera personal del emperador era un dragón dorado escupiendo fuego, rodeado de nubes, una luna plateada y una media luna negra sobre un fondo amarillo. [248]

Los sellos de la dinastía Nguyễn son ricos y diversos en tipos y tenían reglas y leyes estrictas que regulaban su manipulación, gestión y uso. [249] La práctica común de usar sellos fue claramente registrada en el libro "Khâm định Đại Nam hội điển sự lệ" sobre cómo usar sellos, cómo colocarlos y en qué tipos de documentos, que fue compilado por el Gabinete de la dinastía Nguyễn en el año Minh Mạng 3 (1822). [249] Los distintos tipos de sellos de la dinastía Nguyễn tenían diferentes nombres según su función, a saber, Bảo (寶), Tỷ (璽), Ấn (印), Chương (章), Ấn chương (印章), Kim bảo tỷ (金寶璽), Quan phòng (關).防), Đồ ký (圖記), Kiềm ký (鈐記), Tín ký (信記), Ấn Ký (印記), Trưởng ký (長記) y Ký (記). [250] [249]

Los sellos en la dinastía Nguyễn eran supervisados por un par de agencias conocidas como la Oficina de Gestión de Sellos del Ministerio - Oficiales de Turno (印司 - 直處, Ấn ty - Trực xứ ), este es un término que se refiere a dos agencias que se establecieron dentro de cada uno de los Seis Ministerios , estas agencias tenían la tarea de realizar un seguimiento de los sellos, archivos y capítulos de su ministerio. [251] De servicio en la Oficina de Gestión de Sellos del Ministerio estaban los corresponsales de cada ministerio individual que recibían y distribuían documentos y registros de una agencia gubernamental. [251] Estas dos agencias generalmente tenían unas pocas docenas de oficiales que importaban documentos de su ministerio. [251] Por lo general, el nombre del ministerio se adjunta directamente al nombre de la agencia de sellos, por ejemplo, "Oficina de Gestión de Sellos del Ministerio de Asuntos Civiles - Oficiales de Servicio del Ministerio de Asuntos Civiles" (吏印司吏直處, Lại Ấn ty Lại Trực xứ ). [251]