Twitter , oficialmente conocido como X desde julio de 2023, es un servicio de redes sociales . Es uno de los sitios web de redes sociales más grandes del mundo y uno de los sitios web más visitados . [3] [4] Los usuarios pueden compartir mensajes de texto cortos, imágenes y videos en publicaciones cortas comúnmente conocidas como " tweets " o " retweets " (oficialmente "publicar" o "reenviar") y dar me gusta al contenido de otros usuarios. [5] La plataforma también incluye mensajería directa , llamadas de video y audio, marcadores, listas, comunidades, un chatbot Grok , búsqueda de empleo [6] y Spaces, una función de audio social. Los usuarios pueden votar sobre el contexto agregado por usuarios aprobados usando la función Notas de la comunidad .

Twitter fue creado en marzo de 2006 por Jack Dorsey , Noah Glass , Biz Stone y Evan Williams , y se lanzó en julio de ese año. Twitter creció rápidamente; en 2012, más de 100 millones de usuarios producían 340 millones de tuits por día. [7] Twitter, Inc., tenía su sede en San Francisco, California, y más de 25 oficinas en todo el mundo. [8] Una característica distintiva del servicio inicialmente era que las publicaciones debían ser breves. Las publicaciones inicialmente estaban limitadas a 140 caracteres, que se cambiaron a 280 caracteres en 2017. La limitación se eliminó para las cuentas suscritas en 2023. [9] La mayoría de los tuits son producidos por una minoría de usuarios. [10] [11] En 2020, se estimó que aproximadamente 48 millones de cuentas (el 15% de todas las cuentas) estaban dirigidas por bots de Internet en lugar de humanos. [12]

El servicio es propiedad de la empresa estadounidense X Corp. , que se estableció para suceder al propietario anterior Twitter, Inc. en marzo de 2023 luego de la adquisición de Twitter en octubre de 2022 por Elon Musk por US$44 mil millones. Musk declaró que su objetivo con la adquisición era promover la libertad de expresión en la plataforma. Desde su adquisición , la plataforma ha sido criticada por permitir una mayor difusión de desinformación [13] [14] [15] y discursos de odio . [16] [17] [18] Linda Yaccarino sucedió a Musk como CEO el 5 de junio de 2023, y Musk permaneció como presidente y director de tecnología . [19] [20] [21] En julio de 2023, Musk anunció que Twitter cambiaría su nombre a "X" y que el logotipo del pájaro se retiraría, [22] [23] un proceso que se completó en mayo de 2024. En diciembre de 2023, Fidelity estimó que el valor de la empresa bajaría un 71,5% con respecto a su precio de compra. [24] Desde la adquisición de Musk, los datos de las empresas de seguimiento de aplicaciones han demostrado que el uso global de Twitter ha disminuido aproximadamente un 15%, en comparación con una disminución del 5-10% en algunos otros sitios de redes sociales. [25] [26] [27] La plataforma ha negado que el uso haya disminuido en absoluto, y Musk afirma que la membresía había crecido a 600 millones de usuarios a partir de un [update]tuit de mayo de 2024. [28]

Jack Dorsey afirma haber introducido la idea de que un individuo utilice un servicio de SMS para comunicarse con un grupo pequeño durante una "sesión de lluvia de ideas de todo el día" en la empresa de podcasting Odeo en 2006. [29] El nombre en código del proyecto original para el servicio era twttr , una idea que Williams luego atribuyó a Noah Glass , [30] inspirado en Flickr y la longitud de cinco caracteres de los códigos cortos de SMS estadounidenses . La decisión también se debió en parte al hecho de que el dominio twitter.com ya estaba en uso, y fue seis meses después del lanzamiento de twttr que el equipo compró el dominio y cambió el nombre del servicio a Twitter . [31] Los desarrolladores inicialmente consideraron "10958" como el código corto del servicio para mensajes de texto SMS, pero luego lo cambiaron a "40404" para "facilidad de uso y memorabilidad". [32] El trabajo en el proyecto comenzó en febrero de 2006. [33] Dorsey publicó el primer mensaje de Twitter el 21 de marzo de 2006:

Solo estoy configurando mi twttr

21 de marzo de 2006 [34]

Dorsey explicó el origen del título "Twitter" de la siguiente manera: [35]

...nos topamos con la palabra "twitter" y era perfecta. La definición era "una breve ráfaga de información intrascendente" y "el canto de los pájaros". Y eso era exactamente lo que era el producto.

El primer prototipo de Twitter, desarrollado por Dorsey y el contratista Florian Weber, se utilizó como un servicio interno para los empleados de Odeo. [33] La versión completa se presentó públicamente el 15 de julio de 2006. [36] En octubre de 2006, Biz Stone , Evan Williams , Dorsey y otros miembros de Odeo formaron Obvious Corporation y adquirieron Odeo, junto con sus activos, incluidos Odeo.com y Twitter.com, de los inversores y accionistas. [37] Williams despidió a Glass, quien guardó silencio sobre su participación en el inicio de Twitter hasta 2011. [38] Twitter se escindió en su propia empresa en abril de 2007. [39] Williams proporcionó información sobre la ambigüedad que definió este período inicial en una entrevista de 2013: [40]

En el caso de Twitter, no estaba claro qué era. Lo llamaban red social, lo llamaban microblogging , pero era difícil definirlo porque no reemplazaba a nada. Hubo un camino de descubrimiento con algo así, donde con el tiempo te das cuenta de lo que es. Twitter en realidad cambió de lo que pensábamos que era al principio, que describíamos como actualizaciones de estado y una utilidad social. Es eso, en parte, pero la idea a la que finalmente llegamos fue que Twitter era en realidad más una red de información que una red social.

El punto de inflexión de la popularidad de Twitter fue la conferencia South by Southwest Interactive (SXSWi) de 2007. Durante el evento, el uso de Twitter aumentó de 20.000 tuits por día a 60.000. [41] "La gente de Twitter colocó inteligentemente dos pantallas de plasma de 60 pulgadas en los pasillos de la conferencia, transmitiendo exclusivamente mensajes de Twitter", comentó Steven Levy de Newsweek . "Cientos de asistentes a la conferencia se mantenían al tanto de los demás mediante tuits constantes. Los panelistas y oradores mencionaron el servicio, y los blogueros presentes lo promocionaron". [42] La reacción en la conferencia fue muy positiva. [43] El personal de Twitter recibió el premio Web Award del festival con el comentario "nos gustaría agradecerles en 140 caracteres o menos. ¡Y lo acabamos de hacer!". [44]

La empresa experimentó un rápido crecimiento inicial. En 2009, Twitter ganó el premio Webby Award a la "Breakout of the Year" . [45] [46] El 29 de noviembre de 2009, Twitter fue nombrada la Palabra del Año por el Global Language Monitor , declarándola "una nueva forma de interacción social". [47] En febrero de 2010, los usuarios de Twitter enviaban 50 millones de tuits por día. [48] En marzo de 2010, la empresa registró más de 70.000 aplicaciones registradas. [49] En junio de 2010 [update], se publicaron alrededor de 65 millones de tuits cada día, lo que equivale a unos 750 tuits enviados cada segundo, según Twitter. [50] En marzo de 2011 [update], eso suponía unos 140 millones de tuits publicados diariamente. [51] Como se señala en Compete.com , Twitter ascendió al tercer sitio de redes sociales de mayor rango en enero de 2009 desde su puesto anterior de vigésimo segundo. [52]

El uso de Twitter se dispara durante eventos importantes. Por ejemplo, se estableció un récord durante la Copa Mundial de la FIFA 2010 cuando los fanáticos escribieron 2940 tuits por segundo en el período de treinta segundos después de que Japón anotara contra Camerún el 14 de junio de 2010. El récord se rompió nuevamente cuando se publicaron 3085 tuits por segundo después de la victoria de Los Angeles Lakers en las Finales de la NBA de 2010 el 17 de junio de 2010, [53] y luego nuevamente al final de la victoria de Japón sobre Dinamarca en la Copa Mundial cuando los usuarios publicaron 3283 tuits por segundo. [54] El récord se estableció nuevamente durante la Final de la Copa Mundial Femenina de la FIFA 2011 entre Japón y Estados Unidos , cuando se publicaron 7196 tuits por segundo. [55] Cuando el cantante estadounidense Michael Jackson murió el 25 de junio de 2009, los servidores de Twitter colapsaron después de que los usuarios actualizaran su estado para incluir las palabras "Michael Jackson" a una velocidad de 100.000 tuits por hora. [56] El récord actual, al 3 de agosto de 2013 [update], se estableció en Japón, con 143.199 tuits por segundo durante una proyección televisiva de la película Castle in the Sky [57] (superando el récord anterior de 33.388, también establecido por Japón para la proyección televisiva de la misma película). [58]

El primer mensaje de Twitter sin asistencia fuera de la Tierra fue publicado desde la Estación Espacial Internacional por el astronauta de la NASA TJ Creamer el 22 de enero de 2010. [59] A fines de noviembre de 2010, se publicaron un promedio de una docena de actualizaciones por día en la cuenta comunitaria de los astronautas, @NASA_Astronauts. La NASA también ha organizado más de 25 "tweetups" , eventos que brindan a los invitados acceso VIP a las instalaciones y oradores de la NASA con el objetivo de aprovechar las redes sociales de los participantes para promover los objetivos de divulgación de la NASA.

El 11 de abril de 2010, Twitter adquirió el desarrollador de aplicaciones Atebits. Atebits había desarrollado el cliente de Twitter Tweetie, ganador del premio Apple Design Award, para Mac y iPhone . La aplicación se convirtió en el cliente oficial de Twitter para iPhone, iPad y Mac. [60]

Desde septiembre hasta octubre de 2010, la compañía comenzó a implementar "New Twitter", una edición completamente renovada de twitter.com. Los cambios incluyeron la capacidad de ver imágenes y videos sin salir de Twitter haciendo clic en tweets individuales que contienen enlaces a imágenes y clips de una variedad de sitios web compatibles, incluidos YouTube y Flickr , y una revisión completa de la interfaz, que cambió enlaces como '@menciones' y 'Retweets' sobre el flujo de Twitter, mientras que 'Mensajes' y 'Cerrar sesión' se volvieron accesibles a través de una barra negra en la parte superior de twitter.com. A partir del 1 de noviembre de 2010 [update], la compañía confirmó que la "Nueva experiencia de Twitter" se había implementado para todos los usuarios. En 2019, se anunció que Twitter fue la décima aplicación móvil más descargada de la década, de 2010 a 2019. [61]

El 5 de abril de 2011, Twitter probó una nueva página de inicio y eliminó gradualmente el "Twitter antiguo". [62] Sin embargo, se produjo un problema técnico después del lanzamiento de la página, por lo que la página de inicio "retro" anterior todavía estaba en uso hasta que se resolvieron los problemas; la nueva página de inicio se reintrodujo el 20 de abril. [63] [64] El 8 de diciembre de 2011, Twitter revisó su sitio web una vez más para presentar el diseño "Fly", que según el servicio es más fácil de seguir para los nuevos usuarios y promueve la publicidad. Además de la pestaña Inicio , se introdujeron las pestañas Conectar y Descubrir junto con un perfil rediseñado y una cronología de Tweets. El diseño del sitio se ha comparado con el de Facebook. [65] [66] El 21 de febrero de 2012, se anunció que Twitter y Yandex acordaron una asociación. Yandex, un motor de búsqueda ruso, encuentra valor en la asociación debido a los feeds de noticias en tiempo real de Twitter. El director de desarrollo de negocios de Twitter explicó que es importante tener contenido de Twitter donde los usuarios de Twitter van. [67] El 21 de marzo de 2012, Twitter celebró su sexto cumpleaños al anunciar que tenía 140 millones de usuarios, un aumento del 40% desde septiembre de 2011, que enviaban 340 millones de tweets por día. [68] [69]

El 5 de junio de 2012, se dio a conocer un logotipo modificado a través del blog de la empresa, eliminando el texto para mostrar el pájaro ligeramente rediseñado como el único símbolo de Twitter. [70] [71] El 18 de diciembre de 2012, Twitter anunció que había superado los 200 millones de usuarios activos mensuales .

El 28 de enero de 2013, Twitter adquirió Crashlytics para desarrollar sus productos para desarrolladores móviles. [72] El 18 de abril de 2013, Twitter lanzó una aplicación de música llamada Twitter Music para iPhone. [73] El 28 de agosto de 2013, Twitter adquirió Trendrr, [74] seguida de la adquisición de MoPub el 9 de septiembre de 2013. [75] A septiembre de 2013 [update], los datos de la compañía mostraron que 200 millones de usuarios enviaron más de 400 millones de tweets diariamente, con casi el 60% de los tweets enviados desde dispositivos móviles. [76]

Durante el Super Bowl XLVII, el 3 de febrero de 2013, cuando se fue la luz en el Mercedes-Benz Superdome , se le pidió a la vicepresidenta de Mondelez International , Lisa Mann, que tuiteara "Todavía puedes mojar en la oscuridad", refiriéndose a las galletas Oreo . Ella lo aprobó y luego le dijo a Ad Age en 2020: "Literalmente, el mundo [había] cambiado cuando me desperté a la mañana siguiente". Esto se convirtió en un hito en el desarrollo de los comentarios diarios sobre la cultura. [77]

En abril de 2014, Twitter experimentó un rediseño que hizo que el sitio se pareciera un poco a Facebook, con una foto de perfil y una biografía en una columna a la izquierda de la línea de tiempo, y una imagen de encabezado de ancho completo con efecto de desplazamiento de paralaje . [c] [78] Ese diseño se usó como principal para la interfaz de escritorio hasta julio de 2019, sufriendo cambios con el tiempo, como tener fotos de perfil redondeadas desde junio de 2017. [79]

En abril de 2015, la página de inicio de escritorio de Twitter.com cambió. [80] Más tarde en el año se hizo evidente que el crecimiento se había desacelerado, según Fortune, [81] Business Insider, [82] Marketing Land [83] y otros sitios web de noticias, incluido Quartz (en 2016). [84]

El 29 de abril de 2018, el primer tuit comercial desde el espacio fue enviado por la empresa privada Solstar utilizando únicamente infraestructura comercial durante el vuelo New Shepard . [85]

Desde mayo de 2018, las respuestas a los tweets que un algoritmo considera que son perjudiciales para la conversación se ocultan inicialmente y solo se cargan al activar el elemento "Mostrar más respuestas" en la parte inferior. [86]

En 2019, Twitter lanzó otro rediseño de su interfaz de usuario. [87] A principios de 2019 [update], Twitter tenía más de 330 millones de usuarios activos mensuales. [88]

Twitter experimentó un crecimiento considerable durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en 2020. [89] La plataforma también se utilizó cada vez más para desinformación relacionada con la pandemia . [90] Twitter comenzó a marcar tweets que contenían información engañosa y a agregar enlaces a verificaciones de hechos. [91] En mayo de 2020, los moderadores de Twitter marcaron dos tweets del presidente estadounidense Donald Trump como "potencialmente engañosos" y los vincularon a una verificación de hechos. [92] Trump respondió firmando una orden ejecutiva para debilitar la Sección 230 de la Ley de Decencia en las Comunicaciones , que limita la responsabilidad de los sitios de redes sociales por las decisiones de moderación de contenido. [93] [94] [95] Twitter luego prohibió a Trump, alegando que violó "la política de glorificación de la violencia". [96] La prohibición provocó críticas de los conservadores y los líderes europeos, que la vieron como una interferencia en la libertad de expresión. [97]

El 5 de junio de 2021, el gobierno de Nigeria emitió una suspensión indefinida del uso de Twitter en el país, citando que "la desinformación y las noticias falsas difundidas a través de ella han tenido consecuencias violentas en el mundo real", [98] después de que la plataforma eliminara tuits hechos por el presidente nigeriano Muhammadu Buhari . [99] La prohibición de Nigeria fue criticada por Amnistía Internacional . [100]

En 2021, Twitter inició la fase de investigación de Bluesky , un protocolo de redes sociales descentralizado de código abierto donde los usuarios pueden elegir qué curación algorítmica desean. [101] [102] El mismo año, Twitter también lanzó Twitter Spaces, una función de audio social; [103] [104] "superfollows", una forma de suscribirse a creadores para contenido exclusivo; [105] y una versión beta de "Ticketed Spaces", que hace que el acceso a ciertas salas de audio sea de pago. [106] Twitter presentó un rediseño en agosto de 2021, con colores ajustados y una nueva fuente Chirp, que mejora la alineación a la izquierda de la mayoría de los idiomas occidentales. [107]

En junio de 2022, Twitter anunció una asociación con el gigante del comercio electrónico Shopify y sus planes de lanzar una aplicación de canal de ventas para comerciantes de Shopify en EE. UU. [108]

El 23 de agosto de 2022 se publicó el contenido de una denuncia presentada por el exjefe de seguridad informática Peiter Zatko ante el Congreso de los Estados Unidos. Zatko había sido despedido de Twitter en enero de 2022. La denuncia alega que Twitter no reveló varias violaciones de datos, tuvo medidas de seguridad negligentes, violó las regulaciones de valores de los Estados Unidos y rompió los términos de un acuerdo previo con la Comisión Federal de Comercio sobre la protección de los datos de los usuarios. El informe también afirma que el gobierno indio obligó a Twitter a contratar a uno de sus agentes para obtener acceso directo a los datos de los usuarios. [109]

Elon Musk llegó a un acuerdo para adquirir Twitter por 44.000 millones de dólares el 25 de abril de 2022. [110] El acuerdo se cerró formalmente el 27 de octubre de 2022, tras un intento de Musk de rescindirlo en julio. Inmediatamente después del cierre del acuerdo, Musk destituyó a los directivos existentes de Twitter, Inc., incluido el director ejecutivo Parag Agrawal, y se autoproclamó director de la empresa. [111]

Tras el cambio de propietario de Twitter, Musk comenzó a referirse a la plataforma como "X/Twitter" [112] [113] [114] y "X (Twitter)", [115] y renombró varias funciones para eliminar referencias a terminología orientada a aves, incluyendo Birdwatch a Community Notes [116] y Quote Tweets a Quotes. [117] El 23 de julio de 2023, Musk confirmó el cambio de marca, que comenzó cuando el dominio X.com (anteriormente asociado con PayPal) comenzó a redirigir a Twitter; [118] el logotipo se cambió del pájaro a la X al día siguiente, [119] y las cuentas oficiales principales y asociadas de la plataforma también comenzaron a usar la letra X dentro de sus nombres de usuario. [120] El nombre de usuario @x originalmente era propiedad del fotógrafo Gene X Hwang, quien lo registró en 2007. Hwang había expresado su voluntad de vender el nombre de usuario, pero recibió un correo electrónico el 25 de julio de 2023, indicando que la compañía lo estaba tomando. Se le ofreció algo de mercancía X y una reunión con los líderes de la empresa, pero ningún beneficio financiero. [121] El nombre y el icono de la aplicación de Android se cambiaron a X en Google Play el 27 de julio; el mismo cambio se puso en marcha en la App Store el 31 de julio después de que Apple otorgara una excepción a su longitud mínima de caracteres de 2. [122] [123] [124] En esa época, algunos elementos más de la marca Twitter se eliminaron de la versión web, incluidos los tweets que se renombraron a "publicaciones". [125]

El cambio de marca fue descrito como inusual, dado que la marca Twitter ya era fuerte a nivel internacional, con palabras como "tweet" que habían entrado en el lenguaje común. [126] El cambio de marca ha sido criticado sobre la base de que la capacidad de marcación del nombre y el logotipo es débil: hay casi 900 empresas en los EE. UU. que poseen una marca registrada X , [127] incluido un logotipo existente relacionado con las redes sociales propiedad de Meta Platforms . [128] El logotipo de X usa una X en negrita de pizarra , un carácter que ha aparecido en los libros de texto de matemáticas desde la década de 1970 y que está incluido en Unicode como U+1D54F 𝕏 MATHEMATICAL DOUBLE-STRUCK CAPITAL X. [ 129] [130]

En septiembre de 2023, Ad Age , citando una investigación realizada con la empresa The Harris Poll , dijo que el cambio de marca no se había hecho público, y que la mayoría de los usuarios, así como las marcas notables, todavía se referían a la plataforma como Twitter. [131] En diciembre de 2023, Fidelity estimó que el valor de la empresa había bajado un 71,5% con respecto a su precio de compra. [24] Sin embargo, la compra se produjo justo antes de una caída de precios en todo el mercado y Musk reconoció que pagó de más por el servicio. [132] [133] Desde la adquisición de Musk, los datos de las empresas de seguimiento de aplicaciones han demostrado que el uso global de la plataforma ha disminuido aproximadamente un 15%, en comparación con una disminución del 5-10% en algunos otros sitios de redes sociales. [25] [26] [27] Esta disminución en el número de usuarios ha sido cuestionada por Musk, quien afirmó en mayo de 2024 que había 600 millones de usuarios activos mensuales y 300 millones de usuarios activos diarios. [134] [28]

El 17 de mayo de 2024, la URL se cambió oficialmente de twitter.com a x.com. [135] [136]

El 17 de julio de 2024, Musk anunció que la sede de la plataforma se trasladaría de San Francisco a Austin, Texas . Esto fue en respuesta a la Ley de Seguridad , promulgada por el gobernador de California Gavin Newsom , que prohíbe a los distritos escolares aprobar políticas que obliguen a las escuelas a notificar a los padres si su hijo solicita cambiar su identificación de género. [137] [138]

Unos días después de que el cambio de marca entrara en vigor, una actualización del Manual de Estilo de AP recomendó que los periodistas se refirieran a la plataforma como "X, anteriormente conocida como Twitter". [5] A partir de agosto de 2024 [update], ya no recomienda usar el nombre de Twitter a menos que sea necesario, y propone el uso de los términos "publicado en X, dicho en una publicación en X, etc." en lugar de "tuiteado y tuiteado" a menos que se mencione en citas directas. [139]

El 30 de agosto de 2024, el juez del Tribunal Supremo Federal de Brasil, Alexandre de Moraes, ordenó la suspensión de la plataforma en Brasil después de que no designara un representante legal en el país y no pagara las multas pendientes. [140] Esto afectó a unos 22 millones de usuarios brasileños de la plataforma, además de los reporteros y periodistas internacionales que habían viajado a Brasil para cubrir el partido de la NFL en Brasil y ya no podían tuitear en vivo el evento. [141] Después de la prohibición, Bluesky informó un aumento de 2,6 millones de registros de usuarios en una semana, más del 85% de los cuales eran de Brasil. [142]

Los tweets eran visibles públicamente de forma predeterminada, pero los remitentes pueden restringir la entrega de mensajes solo a sus seguidores. Los usuarios pueden silenciar a los usuarios con los que no desean interactuar, bloquear cuentas para que no vean sus publicaciones y eliminar cuentas de su lista de seguidores. [143] [144] [145] Los usuarios pueden publicar a través del sitio web de Twitter, aplicaciones externas compatibles (como para teléfonos inteligentes ) o mediante el Servicio de mensajes cortos (SMS) disponible en ciertos países. [146] Los usuarios pueden suscribirse a las publicaciones de otros usuarios: esto se conoce como "seguir" y los suscriptores se conocen como "seguidores" [147] o "tweeps", un acrónimo de Twitter y peeps. [148] Otros usuarios pueden reenviar publicaciones individuales a su propio feed, un proceso conocido como "reenvío" o "retweet". En 2015, Twitter lanzó "quote tweet" (originalmente llamado "retweet con comentario"), [149] una función que permite a los usuarios agregar un comentario a su publicación, incrustando una publicación en la otra. [150] Los usuarios también pueden marcar como " Me gusta " (anteriormente "favoritos") tweets individuales. [151]

Los contadores de "me gusta", "retweets/reposts" y respuestas aparecen junto a los botones respectivos en las líneas de tiempo, como en las páginas de perfil y los resultados de búsqueda. Los contadores de me gusta y reposts también existen en la página independiente de una publicación. Desde septiembre de 2020, los tweets citados, anteriormente conocidos como "retweet con comentario", tienen su propio contador en la página de su publicación. [149] Hasta la interfaz de escritorio heredada que se suspendió en 2020, se mostraba una fila con fotos de perfil en miniatura de hasta diez usuarios que habían dado me gusta o retuiteado (la primera implementación documentada en la revisión de diciembre de 2011), así como un contador de respuestas de tweets junto al botón correspondiente en la página de un tweet. [152] [153]

Twitter permite a los usuarios actualizar su perfil a través de sus teléfonos móviles, ya sea mediante mensajes de texto o mediante aplicaciones lanzadas para ciertos teléfonos inteligentes y tabletas. [154] [ Se necesita una fuente no primaria ] Se ha comparado a Twitter con un cliente de Internet Relay Chat (IRC) basado en la web. [155] Twitter anunció en un tuit el 1 de septiembre de 2022 que se estaba probando la capacidad de editar un tuit para usuarios seleccionados. La empresa dijo que la función se estaba probando primero para determinar si se podía abusar de ella. Se permitiría la edición durante 30 minutos y las versiones anteriores de una publicación editada estarían disponibles. Con el tiempo, todos los suscriptores de Twitter Blue podrían utilizar la función. [156]

Los usuarios pueden agrupar publicaciones por tema o tipo mediante el uso de hashtags (palabras o frases precedidas por un #signo " "). De manera similar, el @signo " " seguido de un nombre de usuario se utiliza para mencionar o responder a otros usuarios. [157] En 2014, Twitter introdujo los hashtags, hashtags especiales que generan automáticamente un emoji personalizado junto a ellos durante un período de tiempo determinado. [158] Los hashtags pueden ser generados por Twitter [159] o pueden ser comprados por corporaciones. [160] Para volver a publicar un mensaje de otro usuario y compartirlo con sus propios seguidores, un usuario puede hacer clic en el botón de volver a publicar dentro de la publicación. Los usuarios pueden responder a las respuestas de otras cuentas. Los usuarios pueden ocultar las respuestas a sus mensajes y seleccionar quién puede responder a cada uno de sus tuits antes de enviarlos: cualquier persona, cuentas que siguen al autor de la publicación, cuentas específicas o ninguna. [161] [162]

El límite original, estricto, de 140 caracteres se fue relajando gradualmente. En 2016, Twitter anunció que los archivos adjuntos, enlaces y medios como fotos, videos y el nombre de usuario de la persona ya no contarían; una publicación de foto de usuario solía contar alrededor de 24 caracteres. [163] [164] En 2017, los nombres de usuario de Twitter fueron excluidos de manera similar. [165] El mismo año, Twitter duplicó su límite histórico de 140 caracteres a 280. [166] Bajo el nuevo límite, los glifos se cuentan como un número variable de caracteres, dependiendo del alfabeto del que provengan. [166] En 2023, Twitter anunció que los usuarios de Twitter Blue podrían crear publicaciones con una longitud de hasta 4000 caracteres. [167]

t.co es un servicio de acortamiento de URL creado por Twitter. [168] Solo está disponible para enlaces publicados en Twitter y no está disponible para uso general. [168] Todos los enlaces publicados en Twitter utilizan un contenedor t.co. [169] Twitter pretendía que el servicio protegiera a los usuarios de sitios maliciosos, [168] y lo utilizara para rastrear clics en enlaces dentro de tweets. [ 168] [170] Twitter había utilizado anteriormente los servicios de terceros TinyURL y bit.ly. [171]

En junio de 2011, Twitter anunció su propio servicio integrado para compartir fotos que permite a los usuarios cargar una foto y adjuntarla a un Tweet directamente desde Twitter.com. [172] Los usuarios ahora también tienen la posibilidad de agregar imágenes a la búsqueda de Twitter agregando hashtags al tweet. [173] Twitter también planea proporcionar galerías de fotos diseñadas para recopilar y sindicar todas las fotos que un usuario ha subido a Twitter y servicios de terceros como TwitPic . [173] El 29 de marzo de 2016, Twitter introdujo la capacidad de agregar un título de hasta 480 caracteres a cada imagen adjunta a un tweet, [174] [175] accesible a través de un software de lectura de pantalla o al pasar el mouse sobre una imagen dentro de TweetDeck . En abril de 2022, Twitter hizo que la capacidad de agregar y ver subtítulos esté disponible globalmente. Se pueden agregar descripciones a cualquier imagen cargada con un límite de 1000 caracteres. Las imágenes que tienen una descripción tendrán una insignia que dice ALT en la esquina inferior izquierda, que mostrará la descripción al hacer clic. [176]

En 2015, Twitter comenzó a implementar la capacidad de adjuntar preguntas de encuestas a los tuits. Las encuestas están abiertas hasta por 7 días y los votantes no son identificados personalmente. [177] En los primeros años de Twitter, los usuarios podían comunicarse con Twitter mediante SMS. Twitter suspendió esta función en la mayoría de los países en abril de 2023, después de que los piratas informáticos expusieran vulnerabilidades en la función. [178] [179]

En 2016, Twitter comenzó a poner un mayor enfoque en la programación de transmisión de video en vivo, organizando varios eventos, incluidas transmisiones de las convenciones republicana y demócrata durante la campaña presidencial de EE. UU. , [180] y ganando una licitación para los derechos de transmisión no exclusivos de diez juegos de la NFL en 2016. [181] [182] Durante un evento en Nueva York en mayo de 2017, Twitter anunció que planeaba construir un canal de transmisión de video de 24 horas alojado dentro del servicio, con contenido de varios socios. [181] [183] Twitter anunció una serie de asociaciones nuevas y ampliadas para sus servicios de transmisión de video en el evento, incluidos Bloomberg , BuzzFeed , Cheddar , IMG Fashion , Live Nation Entertainment , Major League Baseball , MTV y BET , NFL Network , el PGA Tour , The Players' Tribune , Propagate de Ben Silverman y Howard T. Owens , The Verge , Stadium y la WNBA . [184] A partir del primer trimestre de 2017 [update], Twitter tenía más de 200 socios de contenido, que transmitieron más de 800 horas de video en 450 eventos. [184]

Twitter Spaces es una función de audio social que permite a los usuarios albergar o participar en un entorno virtual de audio en vivo llamado espacio de conversación. Se permite un máximo de 13 personas en el escenario. La función estaba inicialmente limitada a usuarios con al menos 600 seguidores, pero desde octubre de 2021, cualquier usuario de Twitter puede crear un espacio. [185]

En marzo de 2020, Twitter comenzó a probar una función de historias conocida como "fleets" en algunos mercados, [186] [187] que se lanzó oficialmente el 17 de noviembre de 2020. [188] [189] Los Fleets pueden contener texto y medios, solo son accesibles durante 24 horas después de su publicación y se accede a ellos dentro de la aplicación de Twitter; [186] Twitter anunció que comenzaría a implementar publicidad en los Fleets en junio de 2021. [190] Los Fleets se eliminaron en agosto de 2021; Twitter tenía la intención de que los Fleets alentaran a más usuarios a tuitear con regularidad, pero en cambio generalmente los usaban usuarios ya activos. [191]

Se dice que una palabra, frase o tema que se menciona con mayor frecuencia que otros es un "tema de tendencia". Un tema puede ser "tendencia" debido a un evento que naturalmente provoca tuits o mediante un esfuerzo concertado de los usuarios. [192] Estos temas ayudan a Twitter y a sus usuarios a comprender los eventos mundiales y la opinión del público sobre ellos. [193] La interfaz web de Twitter muestra una lista de temas de tendencia en una barra lateral en la página de inicio, junto con contenido patrocinado.

Los temas de tendencia a veces son el resultado de esfuerzos concertados y manipulaciones por parte de los fanáticos de ciertas celebridades o fenómenos culturales, particularmente músicos como Lady Gaga , Justin Bieber , Rihanna y One Direction , y las series de novelas Crepúsculo y Harry Potter . Twitter ha alterado el algoritmo de tendencias en el pasado para evitar la manipulación de este tipo con un éxito limitado. [194] Twitter también censura los hashtags de tendencia que se afirma que son abusivos u ofensivos. Twitter censuró los hashtags #thatsafrican [195] y #thingsdarkiessay después de que los usuarios se quejaran de que los encontraban ofensivos. [196]

A finales de 2009, se añadió la función "Listas de Twitter", que permite a los usuarios seguir una lista seleccionada de cuentas a la vez, en lugar de seguir a usuarios individuales. [147] [197] Actualmente, [ ¿cuándo? ] las listas se pueden configurar como públicas o privadas. Las listas públicas se pueden recomendar a los usuarios a través de la interfaz general de Listas y aparecer en los resultados de búsqueda. [198] Si un usuario sigue una lista pública, aparecerá en la sección "Ver listas" de su perfil, para que otros usuarios puedan encontrarla rápidamente y seguirla también. [199] Las listas privadas solo se pueden seguir si el creador comparte un enlace específico a su lista. Las listas agregan una pestaña separada a la interfaz de Twitter con el título de la lista, como "Noticias" o "Economía".

En octubre de 2015, Twitter introdujo "Momentos", una función que permite a los usuarios seleccionar tuits de otros usuarios para crear una colección más grande. Twitter inicialmente tenía la intención de que la función fuera utilizada por su equipo editorial interno y otros socios; ellos completaron una pestaña dedicada en las aplicaciones de Twitter, que registraba titulares de noticias, eventos deportivos y otro contenido. [200] [201] En septiembre de 2016, la creación de momentos estuvo disponible para todos los usuarios de Twitter. [202]

El 21 de octubre de 2021, un informe basado en un "experimento aleatorio masivo y de larga duración" que analizó "millones de tuits enviados entre el 1 de abril y el 15 de agosto de 2020" descubrió que el algoritmo de recomendación de aprendizaje automático de Twitter amplificó la política de tendencia derechista en las cronologías de inicio personalizadas de los usuarios. [203] : 1 [204] El informe comparó siete países con usuarios activos de Twitter donde había datos disponibles (Alemania, Canadá, Reino Unido, Japón, Francia y España) y examinó tuits "de los principales grupos políticos y políticos". [203] : 4 Los investigadores utilizaron la Encuesta de expertos de Chapel Hill de 2019 (CHESDATA) para posicionar a los partidos sobre la ideología política dentro de cada país. [203] : 4 Los "algoritmos de aprendizaje automático", introducidos por Twitter en 2016, personalizaron el 99% de los feeds de los usuarios al mostrar tweets (incluso tweets más antiguos y retweets de cuentas que el usuario no había seguido directamente) que el algoritmo había "considerado relevantes" para las preferencias pasadas de los usuarios. [203] : 4 Twitter eligió aleatoriamente el 1% de los usuarios cuyas cronologías de inicio mostraban contenido en orden cronológico inverso de los usuarios que seguían directamente. [203] : 2

Twitter tenía aplicaciones móviles para iPhone , iPad y Android . [205] En abril de 2017, Twitter presentó Twitter Lite , una aplicación web progresiva diseñada para regiones con conexiones a Internet poco confiables y lentas, con un tamaño de menos de un megabyte , diseñada para dispositivos con capacidad de almacenamiento limitada. [206] [207]

El 3 de junio de 2021, Twitter anunció un servicio de suscripción de pago llamado Twitter Blue. Tras el cambio de nombre de Twitter a "X" , el servicio de suscripción pasó a llamarse inicialmente X Blue (o simplemente Blue) y, el 5 de agosto de 2023, pasó a llamarse X Premium (o simplemente Premium). [208] [209] La suscripción proporciona funciones premium adicionales al servicio. [210] [211] En noviembre de 2023 se lanzó una suscripción "Premium+", con una tarifa mensual más alta que ofrece beneficios como la omisión de anuncios en los feeds Para ti y Siguiendo. [212]

En noviembre de 2022, Musk anunció planes para agregar verificación de cuentas y la capacidad de cargar audio y video más largos a Twitter Blue. Se eliminó un beneficio anterior que ofrecía artículos de noticias sin publicidad de los editores participantes, pero Musk declaró que Twitter quería trabajar con los editores en un beneficio similar de " evitar el muro de pago ". [213] [214] [215] Musk había presionado para que se lanzara una versión más cara de Twitter Blue después de su adquisición, argumentando que sería necesaria para compensar una disminución en los ingresos por publicidad. [216] Twitter afirma que se requiere la verificación paga para ayudar a reducir las cuentas fraudulentas. [217]

El marcador de verificación se incluyó en un nivel premium de Twitter Blue introducido el 9 de noviembre de 2022, con un precio de US$7,99 al mes. [218] El 11 de noviembre de 2022, después de que la introducción de esta función provocara problemas importantes relacionados con cuentas que usaban la función para hacerse pasar por figuras públicas y empresas, Twitter Blue con verificación se suspendió temporalmente. [219] [220] Después de aproximadamente un mes, Twitter Blue se relanzó el 12 de diciembre de 2022, aunque para aquellos que compren el servicio a través de la tienda de aplicaciones de iOS , el costo será de $10,99 al mes para compensar la división de ingresos del 30% que se lleva Apple. [221]

Twitter inicialmente eximió a los usuarios y entidades que habían obtenido la verificación debido a su condición de figuras públicas, refiriéndose a ellos como "cuentas verificadas heredadas" que "pueden o no ser notables". [222] El 25 de marzo de 2023, se anunció que se eliminaría el estado de verificación "heredada"; se requerirá una suscripción para conservar el estado verificado, con un costo de $ 1,000 por mes para las organizaciones (que están designadas con un símbolo verificado dorado), [217] más $ 50 adicionales para cada "afiliado". [223] [224] El cambio estaba programado originalmente para el 1 de abril de 2023, pero se retrasó al 20 de abril de 2023, luego de las críticas a los cambios. [225] Musk también anunció planes para la línea de tiempo "Para ti" para priorizar las cuentas verificadas y los seguidores de los usuarios solo a partir del 15 de abril de 2023, y amenazó con permitir que solo los usuarios verificados participen en las encuestas (aunque el último cambio aún no se ha producido). [226]

A partir del 21 de abril de 2023, Twitter exige que las empresas participen en el programa de organizaciones verificadas para comprar publicidad en la plataforma, aunque las empresas que gastan al menos 1000 dólares en publicidad al mes reciben automáticamente la membresía en el programa sin costo adicional. [217]

A partir del 25 de abril de 2023, los usuarios verificados tendrán prioridad en las respuestas a los tuits. [227] [228]

En junio de 2021, la empresa abrió aplicaciones para sus opciones de suscripción premium llamadas Super Follows. Esto permite a las cuentas elegibles cobrar $2,99, $4,99 o $9,99 por mes para suscribirse a la cuenta. [229] El lanzamiento solo generó alrededor de $6000 en sus primeras dos semanas. [230] En 2023, la función Super Follows pasó a llamarse simplemente "suscripciones", lo que permite a los usuarios publicar publicaciones y videos exclusivos de formato largo para sus suscriptores; se informó que el cambio en el marketing tenía como objetivo ayudar a competir con Substack . [231]

En mayo de 2021, Twitter comenzó a probar una función Tip Jar en sus clientes iOS y Android. La función permite a los usuarios enviar propinas monetarias a determinadas cuentas, lo que proporciona un incentivo financiero para los creadores de contenido en la plataforma. Tip Jar es opcional y los usuarios pueden elegir si habilitar o no las propinas para su cuenta. [232] El 23 de septiembre de 2021, Twitter anunció que permitirá a los usuarios dar propinas a los usuarios de la red social con bitcoin . La función estará disponible para los usuarios de iOS. Anteriormente, los usuarios podían dar propinas con moneda fiduciaria utilizando servicios como Cash App de Square y Venmo de PayPal . Twitter integrará el servicio de billetera Lightning de bitcoin Strike. Se señaló que, en este momento, Twitter no tomará una parte del dinero enviado a través de la función de propinas. [233]

El 27 de agosto de 2021, Twitter lanzó Ticketed Spaces, que permite a los anfitriones de Twitter Spaces cobrar entre $1 y $999 por el acceso a sus salas. [234] En abril de 2022, Twitter anunció que se asociará con Stripe, Inc. para probar los pagos en criptomonedas para usuarios limitados en la plataforma. Los usuarios elegibles de Ticketed Spaces y Super Follows podrán recibir sus ganancias en forma de moneda USD, una moneda estable cuyo valor es el del dólar estadounidense. Los usuarios también pueden guardar sus ganancias en billeteras criptográficas y luego cambiarlas por otras criptomonedas. [235]

De 2014 a 2017, Twitter ofreció una función de "botón de compra", que permitía a los tuits incorporar productos que se podían comprar desde el servicio. Los usuarios también podían añadir su información de facturación y envío directamente a sus cuentas. Los socios de la plataforma del botón de compra en el lanzamiento incluían a Stripe , Gumroad , Musictoday y The Fancy . [236]

En julio de 2021, Twitter comenzó a probar un "módulo de compra" para usuarios de iOS en Estados Unidos, que permite a las cuentas asociadas a marcas mostrar un carrusel de tarjetas en sus perfiles que muestran productos. A diferencia del botón Comprar, donde el cumplimiento del pedido se realizaba desde Twitter, estas tarjetas son enlaces externos a tiendas en línea desde las que se pueden comprar los productos. [237] En marzo de 2022, Twitter amplió la prueba para permitir que las empresas muestren hasta 50 productos en sus perfiles. [238]

En noviembre de 2021, Twitter introdujo soporte para transmisiones en vivo "comprables", en las que las marcas pueden realizar eventos de transmisión que de manera similar muestran banners y páginas que resaltan los productos que aparecen en la presentación. [239]

Las estimaciones de usuarios diarios varían ya que la empresa no publica estadísticas sobre cuentas activas. Una entrada del blog Compete.com de febrero de 2009 clasificó a Twitter como la tercera red social más utilizada según su recuento de 6 millones de visitantes únicos mensuales y 55 millones de visitas mensuales. [52] Una entrada del blog statista.com de abril de 2017 clasificó a Twitter como la décima red social más utilizada según su recuento de 319 millones de visitantes mensuales. [240] Su base de usuarios global en 2017 fue de 328 millones. [241] Según Musk, la plataforma tenía 500 millones de usuarios activos mensuales en marzo de 2023, 550 millones en marzo de 2024 y 600 millones en mayo de 2024. [28] [242] [243]

En 2009, Twitter fue utilizado principalmente por adultos mayores que podrían no haber utilizado otros sitios sociales antes de Twitter. [244] Según comScore, solo el 11% de los usuarios de Twitter tenían entre 12 y 17 años. [244] Según un estudio de Sysomos en junio de 2009, las mujeres constituían un grupo demográfico de Twitter ligeramente mayor que los hombres: 53% sobre 47%. También afirmó que el 5% de los usuarios representaban el 75% de toda la actividad. [245] Según Quancast, 27 millones de personas en los EE. UU. usaban Twitter en septiembre de 2009; el 63% de los usuarios de Twitter tenían menos de 35 años; el 60% de los usuarios de Twitter eran caucásicos, pero un porcentaje más alto que el promedio (en comparación con otras propiedades de Internet) eran afroamericanos/negros (16%) e hispanos (11%); el 58% de los usuarios de Twitter tienen un ingreso familiar total de al menos US$60.000. [246] La prevalencia del uso de Twitter por parte de los afroamericanos y de muchos hashtags populares ha sido objeto de estudios de investigación. [247] [248]

Twitter creció de 100 millones de usuarios activos mensuales (MAU) en septiembre de 2011, [249] a 255 millones en marzo de 2014, [250] y más de 330 millones a principios de 2019. [251] [252] [88] En 2013, había más de 100 millones de usuarios que usaban Twitter activamente a diario y alrededor de 500 millones de tuits todos los días. [253] Una encuesta de investigación de Pew de 2016 encontró que Twitter es utilizado por el 24% de todos los adultos estadounidenses en línea. Fue igualmente popular entre hombres y mujeres (24% y 25% de los estadounidenses en línea respectivamente), pero más popular entre las generaciones más jóvenes (36% de los jóvenes de 18 a 29 años). [254] Una encuesta de 2019 realizada por la Fundación Pew descubrió que los usuarios de Twitter tienen tres veces más probabilidades de ser menores de 50 años, y la edad media de los usuarios adultos estadounidenses es de 40 años. La encuesta descubrió que el 10% de los usuarios más activos en Twitter son responsables del 80% de todos los tuits. [255]

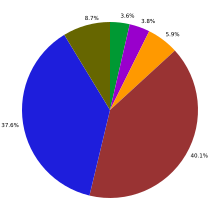

La empresa de investigación de mercado Pear Analytics, con sede en San Antonio , analizó 2.000 tweets (originados en Estados Unidos y en inglés) durante un período de dos semanas en agosto de 2009, desde las 11:00 a. m. hasta las 5:00 p. m. (hora estándar del centro de Estados Unidos) y los dividió en seis categorías. [256] El 40% de los mensajes eran jerga sin sentido , y el 38% eran mensajes conversacionales. El 9% correspondía a mensajes de valor de transmisión, el 6% a la autopromoción y el 4 %, respectivamente, al spam y las noticias.

A pesar de la afirmación abierta del propio Jack Dorsey de que un mensaje en Twitter es "una breve ráfaga de información intrascendente", la investigadora de redes sociales Danah Boyd respondió a la encuesta de Pear Analytics argumentando que lo que los investigadores de Pear etiquetaron como "balbuceo sin sentido" se caracteriza mejor como " acicalamiento social " o "conciencia periférica" (que ella justifica como personas que "quieren saber lo que las personas que las rodean están pensando, haciendo y sintiendo, incluso cuando la co-presencia no es viable"). [257] De manera similar, una encuesta de usuarios de Twitter encontró que un rol social más específico de transmitir mensajes que incluyen un hipervínculo es una expectativa de enlace recíproco por parte de los seguidores. [258]

Según una investigación publicada en abril de 2014, alrededor del 44% de las cuentas de usuario nunca han tuiteado. [259] Alrededor del 22% de los estadounidenses dicen que han usado Twitter, según una encuesta del Pew Research Center de 2019. [260] En 2009, Nielsen Online informó que Twitter tenía una tasa de retención de usuarios del 40%. Muchas personas dejan de usar el servicio después de un mes; por lo tanto, el sitio puede llegar potencialmente solo al 10% de todos los usuarios de Internet . [261] Al notar cómo la demografía de los usuarios de Twitter difiere de los estadounidenses promedio, los comentaristas han advertido contra las narrativas de los medios que tratan a Twitter como representativo de la población, [262] agregando que solo el 10% de los usuarios tuitean activamente y que el 90% de los usuarios de Twitter no han tuiteado más de dos veces. En 2016, los accionistas demandaron a Twitter, alegando que "infló artificialmente el precio de sus acciones al engañarlos sobre la participación de los usuarios". La compañía anunció el 20 de septiembre de 2021 que pagaría 809,5 millones de dólares para resolver esta demanda colectiva. [263]

La participación de los usuarios se mide generalmente por la cantidad de me gusta, respuestas y reenvíos. Un estudio de 2023 mostró que los retuits tienen más probabilidades de contener contenido positivo y dirigirse a audiencias más grandes utilizando el pronombre en primera persona "nosotros". Las respuestas, por otro lado, tienen más probabilidades de contener contenido negativo y dirigirse a personas utilizando el pronombre en segunda persona "tú" y los pronombres en tercera persona "él" o "ella". Mientras que los influencers con muchos seguidores tienden a publicar mensajes positivos, a menudo utilizando la palabra "amor" cuando se dirigen a audiencias más grandes, los usuarios con menos seguidores tienden a entablar conversaciones interpersonales para provocar la participación de los usuarios. [264]

Antes de su cambio de marca a X, Twitter era internacionalmente identificable por su logotipo de pájaro, o Twitter Bird. El logotipo original, que era simplemente la palabra Twitter , estuvo en uso desde su lanzamiento en marzo de 2006. Estaba acompañado por una imagen de un pájaro que luego se descubrió que era una pieza de clip art creada por el diseñador gráfico británico Simon Oxley . [265] Un nuevo logotipo tuvo que ser rediseñado por el fundador Biz Stone con la ayuda del diseñador Philip Pascuzzo, lo que dio como resultado un pájaro más parecido a una caricatura en 2009. Esta versión había sido llamada "Larry the Bird" en honor a Larry Bird, famoso jugador de los Boston Celtics de la NBA . [265] [266]

En un año, el logotipo de Larry the Bird se sometió a un rediseño por parte de Stone y Pascuzzo para eliminar las características de dibujos animados, dejando una silueta sólida de Larry the Bird que se utilizó desde 2010 hasta 2012. [265] En 2012, Douglas Bowman creó una versión aún más simplificada de Larry the Bird, manteniendo la silueta sólida pero haciéndolo más similar a un pájaro azul de montaña . [267] Este logotipo simplemente se llamó "Twitter Bird" y se usó hasta julio de 2023. [265] [268] [269]

El 22 de julio de 2023, Elon Musk anunció que el servicio cambiaría su nombre a "X", [270] en su búsqueda de crear una " aplicación para todo ". [269] La foto de perfil de Twitter de Musk, junto con las cuentas oficiales de la plataforma y los íconos al navegar/registrarse en la plataforma, se actualizaron para reflejar el nuevo logotipo. [271] El logotipo (𝕏) es un símbolo alfanumérico matemático Unicode para la letra "X" con estilo en negrita de doble tachado .

Mike Proulx, del New York Times , criticó este cambio y dijo que el valor de la marca había sido "borrado". Mike Carr dice que el nuevo logotipo da un " aire de señor supremo de la tecnología al estilo ' Gran Hermano '" en contraste con la naturaleza "tierna" del logotipo del pájaro anterior. [272] Los usuarios criticaron duramente la nueva aplicación "X" en la App Store de iOS el día de su presentación, y Miles Klee, de la revista Rolling Stone, dijo que el cambio de marca "huele a desesperación". [273] [274]

El 13 de abril de 2010, Twitter anunció planes para ofrecer publicidad paga a las empresas que pudieran comprar "tweets promocionados" para que aparecieran en resultados de búsqueda selectivos en el sitio web de Twitter, de manera similar al modelo publicitario de Google Adwords . [275] [276] Las fotos de los usuarios pueden generar ingresos libres de regalías para Twitter, y en mayo de 2011 se anunció un acuerdo con World Entertainment News Network (WENN). [277] Twitter generó un estimado de US$139,5 millones en ventas de publicidad durante 2011. [278]

En junio de 2011, Twitter anunció que ofrecería a las pequeñas empresas un sistema de publicidad de autoservicio. [279] La plataforma de publicidad de autoservicio se lanzó en marzo de 2012 para los miembros de la tarjeta American Express y los comerciantes en los EE. UU. solo con invitación. [280] Para continuar con su campaña publicitaria, Twitter anunció el 20 de marzo de 2012 que se introducirían tweets promocionados en los dispositivos móviles. [281] En abril de 2013, Twitter anunció que su plataforma de autoservicio Twitter Ads, que consiste en tweets promocionados y cuentas promocionadas, estaba disponible para todos los usuarios de los EE. UU. sin invitación. [280]

El 3 de agosto de 2016, Twitter lanzó Instant Unlock Card, una nueva función que alienta a las personas a tuitear sobre una marca para ganar recompensas y usar los anuncios conversacionales de la red social. El formato en sí consiste en imágenes o videos con botones de llamada a la acción y un hashtag personalizable. [282]

En octubre de 2017, Twitter prohibió a los medios de comunicación rusos RT y Sputnik anunciarse en su sitio web tras las conclusiones del informe de inteligencia nacional estadounidense del enero anterior de que tanto Sputnik como RT habían sido utilizados como vehículos para la interferencia de Rusia en las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses de 2016. [283] Maria Zakharova , del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores ruso , dijo que la prohibición era una "grave violación" por parte de Estados Unidos de la libertad de expresión. [284]

En octubre de 2019, Twitter anunció que dejaría de publicar anuncios políticos en su plataforma publicitaria a partir del 22 de noviembre. Esto fue el resultado de varias afirmaciones falsas realizadas en anuncios políticos. El director ejecutivo de la empresa, Dorsey, aclaró que la publicidad en Internet tenía un gran poder y era extremadamente eficaz para los anunciantes comerciales, poder que conlleva riesgos significativos para la política, donde decisiones cruciales afectan a millones de vidas. [285] La empresa revocó la prohibición en agosto de 2023, [286] publicando criterios que rigen la publicidad política que no permiten la promoción de contenido falso o engañoso, y exigiendo a los anunciantes que cumplan con las leyes, siendo el cumplimiento responsabilidad exclusiva del anunciante. [287]

En abril de 2022, Twitter anunció la prohibición de anuncios "engañosos" que vayan en contra del "consenso científico sobre el cambio climático". Si bien la empresa no dio pautas completas, afirmó que las decisiones se tomarían con la ayuda de "fuentes autorizadas", incluido el Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático . [288]

Twitter había sido multado varias veces por no cumplir con las leyes y regulaciones. El 25 de mayo de 2022, la Comisión Federal de Comercio y el Departamento de Justicia de los Estados Unidos le impusieron una multa de 150 millones de dólares por recopilar los datos de contacto de los usuarios y utilizarlos para publicidad dirigida. [289] [290]

Twitter se basa en software de código abierto . [291] La interfaz web de Twitter utiliza el marco Ruby on Rails , [292] implementado en una implementación de Ruby Enterprise Edition de rendimiento mejorado de Ruby . [293] [ necesita actualización ]

En los primeros días de Twitter, los tuits se almacenaban en bases de datos MySQL que estaban fragmentadas temporalmente (las bases de datos grandes se dividían en función del momento de publicación). Después de que el enorme volumen de tuits que llegaban causara problemas para leer y escribir en estas bases de datos, la empresa decidió que el sistema necesitaba una reingeniería. [57]

Desde la primavera de 2007 hasta 2008, los mensajes fueron manejados por un servidor de cola persistente Ruby llamado Starling. [294] Desde 2009, la implementación ha sido reemplazada gradualmente con software escrito en Scala . [295] El cambio de Ruby a Scala y la JVM le ha dado a Twitter un aumento de rendimiento de 200 a 300 solicitudes por segundo por host a alrededor de 10,000–20,000 solicitudes por segundo por host. Este aumento fue mayor que la mejora de 10x que los ingenieros de Twitter imaginaron al comenzar el cambio. El desarrollo continuo de Twitter también ha involucrado un cambio del desarrollo monolítico de una sola aplicación a una arquitectura donde diferentes servicios se construyen de forma independiente y se unen a través de llamadas a procedimientos remotos . [57]

El 6 de abril de 2011, los ingenieros de Twitter confirmaron que habían cambiado su pila de búsqueda Ruby on Rails por un servidor Java al que llaman Blender. [296]

Los tweets individuales se registran bajo identificadores únicos llamados copos de nieve , y los datos de geolocalización se agregan usando 'Rockdove'. El acortador de URL t.co luego verifica si hay un enlace de spam y acorta la URL. A continuación, los tweets se almacenan en una base de datos MySQL usando Gizzard , y el usuario recibe un acuse de recibo de que los tweets fueron enviados. Luego, los tweets se envían a los motores de búsqueda a través de la API de Firehose. El proceso es administrado por FlockDB y toma un promedio de 350 ms . [291]

El 16 de agosto de 2013, Raffi Krikorian , vicepresidente de ingeniería de plataformas de Twitter, compartió en una publicación de blog que la infraestructura de la empresa manejó casi 143.000 tweets por segundo durante esa semana, estableciendo un nuevo récord. Krikorian explicó que Twitter logró este récord al combinar sus tecnologías locales y de código abierto. [57] [297]

Twitter fue reconocido por tener una de las API para desarrolladores más abiertas y poderosas de cualquier empresa de tecnología importante. [298] La API del servicio permite que otros servicios web y aplicaciones se integren con Twitter. [299] El interés de los desarrolladores en Twitter comenzó inmediatamente después de su lanzamiento, lo que impulsó a la empresa a lanzar la primera versión de su API pública en septiembre de 2006. [300] La API rápidamente se volvió icónica como una implementación de referencia para las API REST públicas y se cita ampliamente en tutoriales de programación. [301]

Desde 2006 hasta 2010, la plataforma para desarrolladores de Twitter experimentó un fuerte crecimiento y una reputación muy favorable. Los desarrolladores se basaron en la API pública para crear los primeros clientes de Twitter para teléfonos móviles, así como el primer acortador de URL. Sin embargo, entre 2010 y 2012, Twitter tomó una serie de decisiones que fueron recibidas desfavorablemente por la comunidad de desarrolladores. [302] En 2010, Twitter ordenó que todos los desarrolladores adoptaran la autenticación OAuth con solo 9 semanas de aviso. [303] Más tarde ese año, Twitter lanzó su propio acortador de URL, en competencia directa con algunos de sus desarrolladores externos más conocidos. [304] Y en 2012, Twitter introdujo límites de uso más estrictos para su API, "paralizando por completo" a algunos desarrolladores. [305] [306] Si bien estas medidas aumentaron con éxito la estabilidad y la seguridad del servicio, fueron ampliamente percibidas como hostiles para los desarrolladores, lo que provocó que perdieran la confianza en la plataforma. [307]

En julio de 2020, Twitter lanzó la versión 2.0 de la API pública [308] y comenzó a mostrar aplicaciones de Twitter creadas por desarrolladores externos en su sección Twitter Toolbox en abril de 2022. [309]

En enero de 2023, Twitter puso fin al acceso de terceros a sus API, lo que obligó a todos los clientes de Twitter de terceros a cerrar. [310] Esto fue polémico entre la comunidad de desarrolladores, ya que muchas aplicaciones de terceros eran anteriores a las aplicaciones oficiales de la empresa y el cambio no se anunció de antemano. Sean Heber, de Twitterrific, confirmó en una publicación de blog que la aplicación de 16 años de antigüedad ha sido descontinuada. "Lamentamos decir que la desaparición repentina e indigna de la aplicación se debe a un cambio de política no anunciado y no documentado por parte de un Twitter cada vez más caprichoso, un Twitter que ya no reconocemos como confiable ni con el que queremos trabajar más". [311]

En febrero de 2023, Twitter anunció que pondría fin al acceso gratuito a la API de Twitter y comenzó a ofrecer planes pagos con un acceso más limitado. [312]

El 17 de abril de 2012, Twitter anunció que implementaría un "Acuerdo de Patentes para Innovadores" que obligaría a Twitter a utilizar sus patentes únicamente con fines defensivos. [ aclarar ] [313]

Twitter tiene un historial de uso y lanzamiento de software de código abierto al tiempo que supera los desafíos técnicos de su servicio. [314] Una página en su documentación para desarrolladores agradece a docenas de proyectos de código abierto que han utilizado, desde software de control de revisión como Git hasta lenguajes de programación como Ruby y Scala. [315] El software lanzado como código abierto por la empresa incluye el marco Gizzard Scala para crear almacenes de datos distribuidos, la base de datos de gráficos distribuidos FlockDB , la biblioteca Finagle para construir servidores y clientes RPC asincrónicos, el marco de interfaz de usuario TwUI para iOS y el administrador de paquetes del lado del cliente Bower. [316] El popular marco de interfaz Bootstrap también se inició en Twitter y es el décimo repositorio más popular en GitHub . [317]

El 31 de marzo de 2023, Twitter publicó en GitHub el código fuente de su algoritmo de recomendaciones , [318] que determina qué tuits aparecen en la cronología personal del usuario . Según la publicación del blog de Twitter: "Creemos que tenemos la responsabilidad, como la plaza del pueblo de Internet, de hacer que nuestra plataforma sea transparente. Por eso, hoy estamos dando el primer paso en una nueva era de transparencia y abriendo gran parte de nuestro código fuente a la comunidad global". [319] Elon Musk , el CEO en ese momento, había estado prometiendo la medida durante un tiempo: el 24 de marzo de 2022, antes de ser dueño del sitio, encuestó a sus seguidores sobre si el algoritmo de Twitter debería ser de código abierto, y alrededor del 83% de las respuestas dijeron "sí". En febrero, prometió que sucedería en una semana antes de retrasar la fecha límite hasta el 31 de marzo a principios de este mes. [320]

También en marzo de 2023, Twitter sufrió un ataque de seguridad que dio lugar a la publicación de un código propietario. Twitter luego eliminó el código fuente. [321]

Twitter introdujo el primer rediseño importante de su interfaz de usuario en septiembre de 2010, adoptando un diseño de doble panel con una barra de navegación en la parte superior de la pantalla y un mayor enfoque en la incrustación en línea de contenido multimedia. Los críticos consideraron que el rediseño era un intento de emular las características y experiencias que se encuentran en las aplicaciones móviles y los clientes de Twitter de terceros. [322] [323] [324] [325]

El nuevo diseño fue revisado en 2011 con un enfoque en la continuidad con las versiones web y móviles, introduciendo las pestañas "Conectar" (interacciones con otros usuarios como respuestas) y "Descubrir" (más información sobre temas de tendencia y titulares de noticias), un diseño de perfil actualizado y moviendo todo el contenido al panel derecho (dejando el panel izquierdo dedicado a las funciones y la lista de temas de tendencia). [326] En marzo de 2012, Twitter estuvo disponible en árabe, farsi , hebreo y urdu , las primeras versiones de idioma de derecha a izquierda del sitio. [327] En 2023, el sitio web de Twitter enumeró 34 idiomas admitidos por Twitter.com. [328]

En septiembre de 2012, se introdujo un nuevo diseño para los perfiles, con "portadas" más grandes que se podían personalizar con una imagen de encabezado personalizada y una visualización de las fotos recientes publicadas por el usuario. [329] La pestaña "Descubrir" se suspendió en abril de 2015, [330] y fue reemplazada en la aplicación móvil por una pestaña "Explorar", que presenta temas y momentos de tendencia. [331]

En septiembre de 2018, Twitter comenzó a migrar a usuarios web seleccionados a su aplicación web progresiva (basada en su experiencia Twitter Lite para la web móvil), reduciendo la interfaz a dos columnas. Las migraciones a esta versión de Twitter aumentaron en abril de 2019, y algunos usuarios la recibieron con un diseño modificado. [332] [333]

En julio de 2019, Twitter lanzó oficialmente este rediseño, sin ninguna opción adicional para optar por no participar mientras se está conectado. Está diseñado para unificar aún más la experiencia del usuario de Twitter entre las versiones web y de la aplicación móvil , adoptando un diseño de tres columnas con una barra lateral que contiene enlaces a áreas comunes (incluido "Explorar" que se ha fusionado con la página de búsqueda) que anteriormente aparecían en una barra superior horizontal, elementos de perfil como imágenes de encabezado y fotos y textos de biografía fusionados en la misma columna que la línea de tiempo, y características de la versión móvil (como soporte para múltiples cuentas y una opción de exclusión voluntaria para el modo "top tweets" en la línea de tiempo). [334] [335]

En respuesta a las primeras violaciones de seguridad de Twitter, la Comisión Federal de Comercio de los Estados Unidos (FTC) presentó cargos contra el servicio; los cargos se resolvieron el 24 de junio de 2010. Esta fue la primera vez que la FTC tomó medidas contra una red social por fallas de seguridad. El acuerdo requiere que Twitter tome una serie de medidas para proteger la información privada de los usuarios, incluido el mantenimiento de un "programa integral de seguridad de la información" que se auditará de forma independiente cada dos años. [336]

Después de una serie de ataques de alto perfil a cuentas oficiales, incluidas las de Associated Press y The Guardian , [337] en abril de 2013, Twitter anunció una verificación de inicio de sesión de dos factores como medida adicional contra el ataque. [338]

El 15 de julio de 2020, un importante hackeo de Twitter afectó a 130 cuentas de alto perfil, tanto verificadas como no verificadas, como Barack Obama , Bill Gates y Elon Musk ; el hackeo permitió a los estafadores de bitcoin enviar tweets a través de las cuentas comprometidas que pedían a los seguidores que enviaran bitcoins a una dirección pública determinada, con la promesa de duplicar su dinero. [339] En pocas horas, Twitter deshabilitó los tweets y restableció las contraseñas de todas las cuentas verificadas. [339] El análisis del evento reveló que los estafadores habían utilizado la ingeniería social para obtener credenciales de los empleados de Twitter para acceder a una herramienta de administración utilizada por Twitter para ver y cambiar los datos personales de estas cuentas con el fin de obtener acceso como parte de un intento de " aplastar y agarrar " para ganar dinero rápidamente, con un estimado de US$120.000 en bitcoins depositados en varias cuentas antes de que Twitter interviniera. [340] Varias entidades encargadas de hacer cumplir la ley, incluido el FBI, iniciaron investigaciones sobre el ataque. [341]

El 5 de agosto de 2022, Twitter reveló que un error introducido en una actualización de junio de 2021 del servicio permitía a los actores de amenazas vincular direcciones de correo electrónico y números de teléfono a las cuentas de los usuarios de Twitter. [342] [343] El error se informó a través del programa de recompensas por errores de Twitter en enero de 2022 y posteriormente se solucionó. Si bien Twitter originalmente creyó que nadie se había aprovechado de la vulnerabilidad, más tarde se reveló que un usuario del foro de piratería en línea Breach Forums había utilizado la vulnerabilidad para compilar una lista de más de 5,4 millones de perfiles de usuarios, que ofrecieron vender por $ 30,000. [344] [345] La información recopilada por el pirata informático incluye los nombres de pantalla, la ubicación y las direcciones de correo electrónico de los usuarios que podrían usarse en ataques de phishing o usarse para desanonimizar cuentas que funcionan con seudónimos.

Durante una interrupción del servicio, a los usuarios de Twitter se les mostró en un momento la imagen del mensaje de error "fail whale" creada por Yiying Lu , [346] que ilustra ocho pájaros naranjas usando una red para sacar una ballena del océano con el título "¡Demasiados tuits! Por favor, espere un momento e intente nuevamente". [347] La diseñadora web y usuaria de Twitter Jen Simmons fue la primera en acuñar el término "fail whale" en un tuit de septiembre de 2007. [348] [349] En una entrevista de Wired de noviembre de 2013 , Chris Fry, vicepresidente de ingeniería en ese momento, señaló que la empresa había sacado de uso el término "fail whale" ya que la plataforma ahora era más estable. [350] Twitter tuvo aproximadamente un 98% de tiempo de actividad en 2007 (o alrededor de seis días completos de tiempo de inactividad). [351] El tiempo de inactividad fue particularmente notable durante eventos populares en la industria de la tecnología, como el discurso de apertura de la Macworld Conference & Expo de 2008. [352] [353]

En junio de 2009, después de ser criticada por Kanye West y demandada por Tony La Russa por cuentas no autorizadas administradas por impostores , la compañía lanzó su programa "Cuentas verificadas". [354] [355] Twitter declaró que una cuenta con una insignia de verificación de "marca azul" indica "hemos estado en contacto con la persona o entidad que representa la cuenta y verificamos que está aprobada". [356] En julio de 2016, Twitter anunció un proceso de solicitud pública para otorgar el estado verificado a una cuenta "si se determina que es de interés público" y que la verificación "no implica un respaldo". [357] [358] [359] El estado verificado permite el acceso a algunas funciones que no están disponibles para otros usuarios, como ver solo las menciones de otras cuentas verificadas. [360]

En noviembre de 2020, Twitter anunció un relanzamiento de su sistema de verificación en 2021. Según la nueva política, Twitter verifica seis tipos diferentes de cuentas; para tres de ellas (empresas, marcas e individuos influyentes como activistas), la existencia de una página de Wikipedia será un criterio para demostrar que la cuenta tiene "Notabilidad Fuera de Twitter". [361] Twitter afirma que volverá a abrir las aplicaciones de verificación pública en algún momento a "principios de 2021". [362]

En octubre de 2022, después de que Elon Musk adquiriera Twitter, se informó que la verificación se incluiría en el servicio pago Twitter Blue, y que las cuentas verificadas existentes perderían su estado si no se suscribían. [363] El 1 de noviembre, Musk confirmó que la verificación se incluiría en Blue en el futuro, descartando el sistema de verificación existente como un "sistema de señores y campesinos". [213] [214] [215] A raíz de las preocupaciones sobre la posibilidad de suplantación de identidad, Twitter posteriormente volvió a implementar un segundo marcador "Oficial", que consiste en una marca de verificación gris y el texto "Oficial" que se muestra debajo del nombre de usuario, para cuentas de alto perfil de "entidades gubernamentales y comerciales". [364] [365]

En diciembre de 2022, el texto “Oficial” fue reemplazado por una marca de verificación dorada para las organizaciones, así como una marca de verificación gris para las cuentas gubernamentales y multilaterales. [366] [367]

En marzo de 2023, la marca de verificación dorada se puso a disposición de las organizaciones para su compra a través del programa Organizaciones Verificadas (anteriormente llamado Twitter Blue for Business). [366] [367]

Los tweets son públicos, pero los usuarios también pueden enviar "mensajes directos" privados. [368] La información sobre quién ha elegido seguir una cuenta y a quién ha elegido seguir un usuario también es pública, aunque las cuentas se pueden cambiar a "protegidas", lo que limita esta información (y todos los tweets) a los seguidores aprobados. [369] Twitter recopila información de identificación personal sobre sus usuarios y la comparte con terceros como se especifica en su política de privacidad . El servicio también se reserva el derecho de vender esta información como un activo si la empresa cambia de manos. [370] [ se necesita una fuente no primaria ] [371] Los anunciantes pueden dirigirse a los usuarios en función de su historial de tweets y pueden citar tweets en anuncios [372] dirigidos específicamente al usuario.

El 11 de junio de 2009, Twitter lanzó la versión beta de su servicio de "Cuentas verificadas", que permite a las personas con perfiles públicos anunciar el nombre de su cuenta. Las páginas de perfil de estas cuentas muestran una insignia que indica su estado. [373]

El 14 de diciembre de 2010, el Departamento de Justicia de los Estados Unidos emitió una citación judicial ordenando a Twitter que proporcionara información sobre las cuentas registradas o asociadas con WikiLeaks . [374] Twitter decidió notificar a sus usuarios y dijo: "... es nuestra política notificar a los usuarios sobre las solicitudes de información de las fuerzas de seguridad y del gobierno, a menos que la ley nos lo impida". [368]

En mayo de 2011, un demandante conocido como "CTB" en el caso de CTB v Twitter Inc. presentó una demanda contra Twitter en el Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Inglaterra y Gales , [375] solicitando que la empresa divulgara los detalles de los titulares de las cuentas. Esto siguió a los chismes publicados en Twitter sobre la vida privada del futbolista profesional Ryan Giggs . Esto condujo a la controversia de los mandatos judiciales británicos de privacidad de 2011 y al "supermandato judicial". [376] Tony Wang, el jefe de Twitter en Europa, dijo que las personas que hacen "cosas malas" en el sitio tendrían que defenderse bajo las leyes de su propia jurisdicción en caso de controversia y que el sitio entregaría información sobre los usuarios a las autoridades cuando estuviera legalmente obligado a hacerlo. [377] También sugirió que Twitter accedería a una orden judicial del Reino Unido para divulgar los nombres de los usuarios responsables de "actividad ilegal" en el sitio. [378]

Twitter adquirió Dasient , una startup que ofrece protección contra malware para empresas, en enero de 2012. Twitter anunció planes para usar Dasient para ayudar a eliminar anunciantes odiosos en el sitio web. [379] Twitter también ofreció una función que permitiría eliminar tweets de forma selectiva por país, antes de que los tweets eliminados se eliminaran en todos los países. [380] [381] El primer uso de la política fue bloquear la cuenta del grupo neonazi alemán Besseres Hannover el 18 de octubre de 2012. [382] La política se utilizó nuevamente al día siguiente para eliminar tweets franceses antisemitas con el hashtag #unbonjuif ("un buen judío"). [383]

Tras compartir imágenes que mostraban el asesinato del periodista estadounidense James Foley en 2014, Twitter dijo que en ciertos casos eliminaría fotos de personas que habían muerto tras pedidos de familiares y "personas autorizadas". [384] [385]

In 2015, following updated terms of service and privacy policy, Twitter users outside the United States were legally served by the Ireland-based Twitter International Company instead of Twitter, Inc. The change made these users subject to Irish and European Union data protection laws.[386]

On April 8, 2020, Twitter announced that users outside of the European Economic Area or United Kingdom (thus subject to GDPR) will no longer be allowed to opt out of sharing "mobile app advertising measurements" to Twitter third-party partners.[387]

On October 9, 2020, Twitter took additional steps to counter misleading campaigns ahead of the 2020 US Election. Twitter's new temporary update encouraged users to "add their own commentary" before retweeting a tweet, by making 'quoting tweet' a mandatory feature instead of optional. The social network giant aimed at generating context and encouraging the circulation of more thoughtful content.[388] After limited results, the company ended this experiment in December 2020.[389]

On May 25, 2022, Twitter was fined $150 million for collecting users' phone numbers and email addresses used for security and using them for targeted advertising, required to notify its users, and banned from profiting from "deceptively collected data".[390] The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice stated that Twitter violated a 2011 agreement not to use personal security data for targeted advertising.

In September 2024, the FTC released a report summarizing 9 company responses (including from Twitter) to orders made by the agency pursuant to Section 6(b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 to provide information about user and non-user data collection (including of children and teenagers) and data use by the companies that found that the companies' user and non-user data practices put individuals vulnerable to identity theft, stalking, unlawful discrimination, emotional distress and mental health issues, social stigma, and reputational harm.[391][392][393]

In August 2013, Twitter announced plans to introduce a "report abuse" button for all versions of the site following uproar, including a petition with 100,000 signatures, over Tweets that included rape and death threats to historian Mary Beard, feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez and the member of parliament Stella Creasy.[394][395][396] Twitter announced new reporting and blocking policies in December 2014,[397][398][399][400] including a blocking mechanism devised by Randi Harper, a target of GamerGate.[401][402][403] In February 2015, CEO Dick Costolo said he was 'frankly ashamed' at how poorly Twitter handled trolling and abuse, and admitted Twitter had lost users as a result.[404]

As per a research study conducted by IT for Change on abuse and misogynistic trolling on Twitter directed at Indian women in public-political life, women perceived to be ideologically left-leaning, dissenters, Muslim women, political dissenters, and political commentators and women from opposition parties received a disproportionate amount of abusive and hateful messages on Twitter.[405]

In 2016, Twitter announced the creation of the Twitter Trust & Safety Council to help "ensure that people feel safe expressing themselves on Twitter". The council's inaugural members included 50 organizations and individuals.[406] The announcement of Twitter's "Trust & Safety Council" was met with objection from parts of its userbase.[407][408] Critics accused the member organizations of being heavily skewed towards "the restriction of hate speech" and a Reason article expressed concern that "there's not a single uncompromising anti-censorship figure or group on the list".[409][410]

Twitter banned 7,000 accounts and limited 150,000 more that had ties to QAnon on July 21, 2020. The bans and limits came after QAnon-related accounts began harassing other users through practices of swarming or brigading, coordinated attacks on these individuals through multiple accounts in the weeks prior. Those accounts limited by Twitter will not appear in searches nor be promoted in other Twitter functions. Twitter said they will continue to ban or limit accounts as necessary, with their support account stating "We will permanently suspend accounts Tweeting about these topics that we know are engaged in violations of our multi-account policy, coordinating abuse around individual victims, or are attempting to evade a previous suspension".[411]