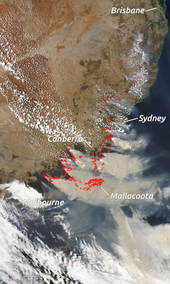

La temporada de incendios forestales australiana 2019-20 , [a] o Verano Negro , fue una de las temporadas de incendios más intensas y catastróficas registradas en Australia . Incluyó un período de incendios forestales en muchas partes de Australia , que, debido a su intensidad, tamaño, duración y dimensión incontrolable inusuales, fue considerado un megaincendio por los medios de comunicación en ese momento. [16] [b] Las condiciones excepcionalmente secas, la falta de humedad del suelo y los incendios tempranos en el centro de Queensland llevaron a un inicio temprano de la temporada de incendios forestales, que comenzó en junio de 2019. [18] Cientos de incendios ardieron, principalmente en el sureste del país, hasta mayo de 2020. Los incendios más graves alcanzaron su punto máximo entre diciembre de 2019 y enero de 2020.

Los incendios quemaron aproximadamente 24,3 millones de hectáreas (243.000 kilómetros cuadrados ), [c] [1] destruyeron más de 3.000 edificios (incluidas 2.779 viviendas), [19] y mataron al menos a 34 personas. [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [d] Según el Instituto Menzies de la Universidad de Tasmania, el humo de los incendios forestales fue responsable de más de 400 muertes, según informó el Medical Journal of Australia. [25]

En diciembre de 2023, el Sydney Morning Herald informó que un gran volumen de humo en la cuenca de Sydney resultó del llamado "megaincendio" de Gospers Mountain después de que el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur perdiera el control de las quemas en noviembre y diciembre de 2019. [26] Se afirmó que tres mil millones de vertebrados terrestres, la gran mayoría reptiles , se vieron afectados y se cree que algunas especies en peligro de extinción fueron llevadas a la extinción. [27] Se esperaba que el costo de lidiar con los incendios forestales superara los 4.400 millones de dólares australianos de los incendios del Sábado Negro de 2009 , [28] y los ingresos del sector turístico cayeron en más de 1.000 millones de dólares australianos. [29] Los economistas estimaron que los incendios forestales, el desastre natural más costoso de la historia de Australia, pueden haber costado más de 78.000 a 88.000 millones de dólares australianos en daños a la propiedad y pérdidas económicas. [30] Casi el 80% de los australianos se vieron afectados por los incendios forestales de alguna manera. [31] En su punto máximo, la calidad del aire descendió a niveles peligrosos en todos los estados del sur y el este, [32] y el humo se había estado moviendo hacia arriba de 11.000 kilómetros (6.800 millas) a través del Océano Pacífico Sur , impactando las condiciones climáticas en otros continentes. [33] [34] Los datos satelitales estimaron que las emisiones de carbono de los incendios fueron de alrededor de 715 millones de toneladas, [35] [36] superando las emisiones normales anuales de incendios forestales y combustibles fósiles de Australia en alrededor del 80%. [37] [38] [39]

Desde septiembre de 2019 hasta marzo de 2020, los incendios afectaron gravemente a varias regiones del estado de Nueva Gales del Sur (NSW). En el este y noreste de Victoria , grandes áreas de bosque ardieron sin control durante cuatro semanas antes de que los incendios emergieran de los bosques a fines de diciembre. Se declararon múltiples estados de emergencia en Nueva Gales del Sur , [40] [41] [42] Victoria, [43] y el Territorio de la Capital Australiana . [44] Se solicitaron refuerzos de toda Australia para ayudar a combatir los incendios y relevar a las tripulaciones locales exhaustas en Nueva Gales del Sur. La Fuerza de Defensa Australiana se movilizó para brindar apoyo aéreo al esfuerzo de extinción de incendios y proporcionar mano de obra y apoyo logístico. [45] [46] Los bomberos, suministros y equipos de Canadá , Nueva Zelanda , Singapur y los Estados Unidos , entre otros, ayudaron a combatir los incendios. [47] Un avión cisterna [48] y dos helicópteros [49] [2] se estrellaron durante las operaciones, matando a tres miembros de la tripulación. Dos camiones de bomberos sufrieron accidentes fatales y murieron tres bomberos. [50] [51]

Para el 4 de marzo de 2020, todos los incendios en Nueva Gales del Sur se habían extinguido por completo (hasta el punto de que no hubo incendios en el estado por primera vez desde julio de 2019), [52] y todos los incendios de Victoria habían sido contenidos. [53] El último incendio de la temporada ocurrió en el lago Clifton, Australia Occidental , a principios de mayo. [54]

Se ha debatido mucho sobre la causa subyacente de la intensidad y la escala de los incendios, incluido el papel de las prácticas de gestión de incendios y el cambio climático , que durante el pico de la crisis atrajeron una atención internacional significativa, [55] a pesar de que los incendios australianos anteriores quemaron áreas mucho más grandes ( 1974-75 ) o mataron a más personas ( 2008-09 ). [56] Los políticos que visitaron las áreas afectadas por los incendios recibieron respuestas mixtas, en particular el Primer Ministro Scott Morrison . [57] [58] Se estima que el público en general, organizaciones internacionales, figuras públicas y celebridades donaron 500 millones de dólares australianos para el socorro a las víctimas y la recuperación de la vida silvestre . Se enviaron convoyes de alimentos donados , ropa y alimento para el ganado a las áreas afectadas.

A partir de finales de julio y principios de septiembre de 2019, los incendios afectaron gravemente a varias regiones del estado de Nueva Gales del Sur , como la Costa Norte , la Costa Norte Central , la Región Hunter , Hawkesbury y Wollondilly en el extremo oeste de Sídney, las Montañas Azules , Illawarra y la Costa Sur , Riverina y las Montañas Snowy con más de 100 incendios ardieron en todo el estado. En el este y noreste de Victoria , grandes áreas de bosque ardieron sin control durante cuatro semanas antes de que los incendios emergieran de los bosques a fines de diciembre, cobrando vidas, amenazando muchas ciudades y aislando Corryong y Mallacoota . Se declaró el estado de desastre para East Gippsland . [59] Se produjeron incendios importantes en Adelaide Hills y Kangaroo Island en Australia del Sur y partes del ACT . Las áreas moderadamente afectadas fueron el sureste de Queensland y áreas del suroeste de Australia Occidental , con algunas áreas en Tasmania levemente afectadas.

El 12 de noviembre de 2019 se declaró un peligro catastrófico de incendio en la región del Gran Sídney por primera vez desde la introducción de este nivel en 2009 y se impuso una prohibición total de incendios en siete regiones de Nueva Gales del Sur, incluida el Gran Sídney. [60] Las áreas de Illawarra y Greater Hunter también experimentaron peligros catastróficos de incendios, al igual que otras partes del estado, incluidas las partes ya devastadas por el fuego del norte de Nueva Gales del Sur. [61] Las ramificaciones políticas de la temporada de incendios han sido significativas. Una decisión del Gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur de recortar la financiación de los servicios de bomberos basándose en estimaciones presupuestarias, así como unas vacaciones tomadas por el Primer Ministro australiano Scott Morrison , durante un período en el que murieron dos bomberos voluntarios, y su apatía percibida hacia la situación, dieron lugar a una controversia.

Al 14 de enero de 2020 [update], 18,626 millones de hectáreas (46,03 millones de acres) se habían quemado o estaban ardiendo en todos los estados y territorios australianos . [62] Los ecologistas de la Universidad de Sídney estimaron que se perdieron 480 millones de mamíferos, aves y reptiles desde septiembre y existe la preocupación de que especies enteras de plantas y animales puedan haber sido aniquiladas por los incendios forestales, [63] [64] que luego se expandió a más de mil millones. [65]

En febrero de 2020 se informó que investigadores de la Universidad Charles Sturt descubrieron que las muertes de nueve ratones ahumados se debieron a una "enfermedad pulmonar grave" causada por una neblina de humo que contenía partículas PM2.5 provenientes de incendios forestales a 50 kilómetros de distancia. [66]

Cuando los incendios se extinguieron allí, destruyeron 2.448 viviendas, así como 284 instalaciones y más de 5.000 dependencias solo en Nueva Gales del Sur. [67] Se confirmó que veintiséis personas murieron en Nueva Gales del Sur desde octubre. [67] La última muerte reportada fue el 23 de enero de 2020 tras la muerte de un hombre cerca de Moruya . [48]

En Nueva Gales del Sur, los incendios quemaron más tierra que cualquier otro incendio en los últimos 25 años, además de ser la peor temporada de incendios forestales registrada en el estado. [68] [69] [70] Nueva Gales del Sur también experimentó el complejo de incendios forestales en llamas más largo y continuo en la historia de Australia, habiendo quemado más de 4 millones de hectáreas (9.900.000 acres), con llamas de 70 metros de altura (230 pies) reportadas. [71] En comparación, los incendios forestales de California de 2018 consumieron 800.000 hectáreas (2.000.000 acres) y los incendios forestales de la selva amazónica de 2019 quemaron 900.000 hectáreas (2.200.000 acres) de tierra. [72]

Si bien el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur considera que estos incendios forestales son la peor temporada de incendios forestales que se recuerda en ese estado, [73] los incendios forestales de 1974-75 fueron mucho más grandes a nivel nacional [d] y consumieron 117 millones de hectáreas (290 millones de acres ; 1.170.000 kilómetros cuadrados ; 450.000 millas cuadradas ). [74] Sin embargo, debido a su menor intensidad y ubicación remota, los incendios de 1974 causaron alrededor de 5 millones de dólares australianos (aproximadamente 36,5 millones de dólares australianos en 2020 [75] ) en daños. [74] En diciembre de 2019, el Gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur declaró el estado de emergencia después de que las temperaturas récord y la sequía prolongada exacerbaran los incendios forestales. [76] [77]

Debido a preocupaciones de seguridad y una presión pública significativa, los espectáculos de fuegos artificiales de Nochevieja se cancelaron en Nueva Gales del Sur, incluidos eventos muy populares en Campbelltown , Liverpool , Parramatta y en las playas del norte de Sídney , y también en la capital del país, Canberra . [78] [79] Cuando las temperaturas alcanzaron los 49 °C (120 °F), la primera ministra de Nueva Gales del Sur, Gladys Berejiklian, convocó un nuevo estado de emergencia de siete días con efecto a partir de las 9 a. m. del 3 de enero de 2020. [80] [81] [82]

El 23 de enero de 2020 , un avión cisterna Lockheed C-130 Hercules (N134CG) se estrelló en Peak View, cerca de Cooma, mientras lanzaba bombas de agua sobre un incendio. El avión quedó destruido, lo que provocó la muerte de los tres tripulantes estadounidenses a bordo. [48] [83] Fue uno de los once grandes aviones cisterna traídos a Australia para la temporada de incendios desde Canadá y Estados Unidos. [84] Llegar al lugar del accidente resultó difícil debido a los incendios forestales activos en la zona. [85] El accidente se produjo en un denso matorral y se extendió aproximadamente 1 kilómetro (0,62 millas). [86] La Oficina Australiana de Seguridad del Transporte (ATSB) inició una investigación para determinar la causa del accidente. [85]

El 28 de febrero se publicó un informe preliminar de la ATSB. Uno de los hechos determinados fue que la grabadora de voz de cabina (CVR) estaba defectuosa y "... no había grabado ningún audio del vuelo accidentado". A diciembre de 2020, [update]la investigación no había concluido. [87]

El 31 de enero de 2020, el Territorio de la Capital Australiana declaró el estado de emergencia en las zonas alrededor de Canberra [88] debido a que varios incendios forestales amenazaban la ciudad y habían quemado 60.000 hectáreas (150.000 acres). [89]

El 7 de febrero de 2020, se informó que las lluvias torrenciales en la mayor parte del sureste de Australia habían extinguido un tercio de los incendios existentes; [90] y al 10 de febrero solo quedaba una pequeña cantidad de incendios sin control. [91]

El Informe Garnaut sobre el cambio climático de 2008 afirmó: [107] [108]

Las proyecciones recientes sobre el clima propicio para los incendios (Lucas et al. , 2007) [14] sugieren que las temporadas de incendios comenzarán antes, terminarán un poco más tarde y, en general, serán más intensas. Este efecto aumenta con el tiempo, pero debería ser directamente observable en 2020.

Para describir las tendencias emergentes de incendios, el estudio de Lucas y otros definió dos nuevas categorías de condiciones climáticas adversas: "muy extremo" y "catastrófico".

El análisis del Bushfire CRC , la Oficina Australiana de Meteorología y la Investigación Marina y Atmosférica de CSIRO encontró que el número de días de peligro de incendio "muy alto" generalmente aumenta entre un 2 y un 13 % para 2020 para los escenarios bajos ( aumento global de 0,4 °C (0,72 °F) ) y entre un 10 y un 30 % para los escenarios altos ( aumento global de 1,0 °C (1,8 °F) ). El número de días de peligro de incendio "extremo" generalmente aumenta entre un 5 y un 25 % para 2020 para los escenarios bajos y entre un 15 y un 65 % para los escenarios altos. [14]

En abril de 2019, un grupo de ex jefes de servicios de bomberos australianos, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action , advirtió que Australia no estaba preparada para la próxima temporada de incendios. Pidieron al próximo primer ministro [g] que se reuniera con los ex líderes de los servicios de emergencia "quienes describirán, sin restricciones de sus antiguos empleadores, cómo los riesgos del cambio climático están aumentando rápidamente". [109] [110] Greg Mullins, el segundo comisionado de bomberos y rescate con más años de servicio en Nueva Gales del Sur y ahora consejero del Climate Council , dijo que pensaba que el próximo verano iba a ser "el peor que he visto" para los equipos de bomberos, y renovó sus llamamientos para que el gobierno tome medidas urgentes para abordar el cambio climático y detener las crecientes emisiones de Australia. [110]

En agosto de 2019, el Centro de Investigación sobre Incendios Forestales y Riesgos Naturales, financiado con fondos federales, publicó un informe de perspectivas estacionales que advertía sobre un "potencial de incendio superior a lo normal" para el sur y sureste de Queensland, las áreas de la costa este de Nueva Gales del Sur y Victoria, para partes de Australia Occidental y Australia del Sur. [111] [112] En diciembre de 2019, el Centro de Investigación sobre Incendios Forestales y Riesgos Naturales actualizó su aviso de "potencial de incendio superior a lo normal". [113]

La Universidad Nacional de Australia informó que el área quemada en 2019-2020 estuvo "muy por debajo del promedio" debido a los bajos niveles de combustible y la actividad de incendios en partes despobladas del norte de Australia, pero que "a pesar de la baja actividad de incendios en general, se produjeron grandes incendios forestales en el sureste de Australia, desde el sureste de Queensland hasta la isla Canguro". [17]

El Período de Peligro de Incendios Forestales establecido por la ley de Nueva Gales del Sur normalmente comienza el 1 de octubre y continúa hasta el 31 de marzo. [114] En 2019-20, la temporada de incendios comenzó temprano con una sequía que afectó al 95 por ciento del estado y condiciones persistentes de sequedad y calidez en todo el estado. [115] Doce áreas de gobierno local comenzaron el Período de Peligro de Incendios Forestales dos meses antes, el 1 de agosto de 2019, [116] y nueve más comenzaron el 17 de agosto de 2019. [115] [117] En la semana anterior al 10 de febrero de 2020, una amplia franja de fuertes lluvias arrasó la mayor parte de la costa de Nueva Gales del Sur, extinguiendo una cantidad significativa de incendios; dejó 33 incendios activos, de los cuales cinco estaban sin control, todos ubicados en las regiones del Valle de Bega y las Montañas Snowy. [91] [118] Entre julio de 2019 y el 13 de febrero de 2020, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur informó que 11.264 incendios de matorrales o pastizales quemaron 5,4 millones de hectáreas (13 millones de acres), destruyeron 2.439 viviendas y se utilizaron aproximadamente 24 megalitros (5,3 millones de galones imperiales; 6,3 millones de galones estadounidenses) de retardante de fuego . [119]

El 6 de septiembre de 2019, las zonas del norte del estado experimentaron peligros extremos de incendio. Entre los incendios se encontraban el de Long Gully Road, cerca de Drake , que ardió hasta finales de octubre y mató a dos personas y destruyó 43 viviendas; [120] el de Mount McKenzie Road, que ardió en las afueras del sur de Tenterfield y causó heridas graves a una persona, destruyó una vivienda y dañó gravemente cuatro viviendas; y el de Bees Nest, cerca de Ebor , que ardió hasta el 12 de noviembre y destruyó siete viviendas. [121]

Un gran incendio comenzó en el bosque estatal de Chaelundi, al oeste de Nymbodia. El fuego se extendió al suroeste de Grafton durante un intenso período de crecimiento del incendio, donde se convirtió en un PyroCumulonimbus [122] e invadió el pueblo de Nymboida, destruyendo 80 casas. [123] Otros incendios más pequeños en el área incluyen el incendio de Myall Creek Road. [91]

En el área de Port Macquarie - Hastings , el primer incendio se reportó en Lindfield Park el 18 de julio de 2019, [124] que ardía en un pantano de turba seca y amenazaba casas en Sovereign Hills y cruzaba la Pacific Highway en Sancrox. El 12 de febrero de 2020, el incendio se declaró extinguido después de 210 días, habiendo quemado 858 hectáreas (2120 acres), de las cuales aproximadamente 400 hectáreas (990 acres) estaban bajo tierra; [125] [126] cerca del aeropuerto de Port Macquarie . [127] El incendio de turba se extinguió después de que se bombearan 65 megalitros (14 millones de galones imperiales ; 17 millones de galones estadounidenses ) de agua recuperada a los humedales adyacentes; seguido de 260 milímetros (10 pulgadas) de lluvia durante cinco días. [125] En el suburbio de Crestwood, en Port Macquarie, se inició un incendio el 26 de octubre a causa de una tormenta eléctrica seca. Los bombarderos de agua se retrasaron al día siguiente en un intento de controlar el incendio que ardía en un pantano al suroeste de Port Macquarie. El 28 de octubre, los voluntarios del Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur (NSWRFS) lograron escapar de un incendio provocado por un cambio repentino del viento que empujó el fuego hacia el sur, en dirección al lago Cathie , y hacia el oeste, sobre el lago Innes . Port Macquarie y las áreas circundantes quedaron cubiertas por una densa nube de humo el 29 de octubre y la actividad de los incendios durante la semana siguiente hizo que el cielo tuviera un resplandor anaranjado.

Un incendio ardió en áreas silvestres en la meseta de Carrai al oeste de Kempsey . Este incendio se unió al incendio de Stockyard Creek y junto con el incendio de Coombes Gap y se extendió hacia el este en dirección a Willawarrin, Temagog, Birdwood, Yarras, Bellangary, Kindee y Upper Rollands Plains. También se quemó la tierra alrededor de Nowendoc y Yarrowich. Al 6 de diciembre de 2019 [update], este incendio quemó casi 400.000 hectáreas (988.422 acres), [128] [129] [130] destruyendo numerosas casas y cobrándose la vida de tres personas. [131]

El 28 de octubre se inició un incendio al noroeste de Harrington , cerca de los humedales de Cattai. Este incendio amenazó las ciudades de Harrington, Crowdy Head y Johns River mientras se extendía hacia el norte en dirección a Dunbogan. Este incendio se cobró una vida en Johns River, [131] donde también destruyó viviendas y quemó más de 12 000 hectáreas (29 653 acres). [ cita requerida ]

En Hillville, un incendio se hizo grande debido a las condiciones de calor y viento, lo que provocó desorden en la cercana ciudad de Taree , al norte. Se llamaron autobuses temprano para llevar a los estudiantes a casa antes de que la amenaza de incendio se volviera demasiado peligrosa. El 9 de noviembre de 2019, el incendio alcanzó Old Bar y Wallabi Point, amenazando muchas propiedades. Los dos días siguientes, el incendio llegó a Tinonee y Taree South, amenazando el Centro de Servicio de Taree. Los bombarderos de agua arrojaron agua sobre las instalaciones para protegerlas. El incendio giró brevemente en dirección a Nabiac antes de que el viento lo empujara hacia Failford. Otras comunidades afectadas fueron Rainbow Flat, Khappinghat, Kooringhat y Purfleet . Un incendio puntual saltó a Ericsson Lane, amenazando a las empresas. Finalmente, quemó 31.268 hectáreas (77.260 acres). [132] [133]

En el Parque Nacional Dingo Tops, un pequeño incendio que comenzó en las cercanías de Rumba Dump Fire Trail quemó las cordilleras y afectó a las pequeñas comunidades de Caparra y Bobin. El incendio, avivado por condiciones casi catastróficas, creció considerablemente el 8 de noviembre de 2019 y consumió casi todo a su paso. La pequeña comunidad de Caparra perdió catorce hogares en pocas horas mientras el incendio forestal continuaba hacia el pequeño pueblo de Bobin , donde numerosas casas y la escuela pública de Bobin fueron destruidas en el incendio. [134] Se perdieron catorce casas en una calle de Bobin. El NSWRFS envió alertas a las personas en Killabakh, Upper Lansdowne, Kippaxs, Elands y Marlee para monitorear las condiciones. [ cita requerida ]

El Rally de Australia 2019 , planeado para ser la ronda final del Campeonato Mundial de Rally 2019 , fue un evento de carreras de motor programado para celebrarse en Coffs Harbour entre el 14 y el 17 de noviembre. [135] Una semana antes de que comenzara el rally, el incendio forestal comenzó a afectar la región que rodea a Coffs Harbour, y los organizadores del evento acortaron el evento en respuesta al deterioro de las condiciones. [136] Con el empeoramiento de la situación, los repetidos llamados de los competidores (la mayoría de los cuales estaban basados en Europa) para cancelar el evento prevalecieron y el evento se canceló el 12 de noviembre. [137] [138]

A fines de diciembre de 2019, comenzaron incendios a ambos lados de la Pacific Highway alrededor de la región de Coopernook . Quemaron 278 hectáreas (687 acres) antes de que pudieran controlarse. [ cita requerida ]

En la región de Hunter , el incendio de Kerry Ridge ardió en el Parque Nacional Wollemi , los bosques estatales de Nullo Mountain, Coricudgy y Putty en la Región del Medio Oeste , y las áreas de gobierno local de Muswellbrook y Singleton . [139] El incendio se extinguió el 10 de febrero de 2020, [91] habiendo quemado aproximadamente 191.000 hectáreas (471.971 acres) durante 79 días. [140]

El incendio de Gospers Mountain fue provocado por un rayo el 26 de octubre cerca de Gospers Mountain en el Parque Nacional Wollemi . Durante los siguientes 16 días, el incendio quemó aproximadamente 56.000 ha (140.000 acres) y fue controlado en gran parte por el Servicio de Parques Nacionales y Vida Silvestre de Nueva Gales del Sur. El 11 de noviembre, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur tomó el control de la gestión del incendio y emitió una declaración preventiva de la Sección 44 ante el deterioro previsto de las condiciones.

Alrededor del 11 de noviembre de 2019, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur ideó una estrategia para contener el incendio de Gospers Mountain utilizando caminos principales, senderos de incendios importantes y una dependencia excesiva de quemas estratégicas a gran escala. [141] Se calculó que esta estrategia daría como resultado un área quemada de 450.000 ha. [142] Bajo esta estrategia, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur llevó a cabo ocho quemas estratégicas, generalmente a muchos kilómetros del borde del incendio de Gospers Mountain, y cada una de ellas fracasó y se escapó de la contención. Esto hizo que el incendio aumentara significativamente de tamaño. En cada caso, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur describió las quemas que escaparon como el "incendio de Gospers Mountain", aunque en muchos casos, las quemas se iniciaron por separado. El área quemada por estas quemas que escaparon representó más de 130.000 hectáreas, casi una cuarta parte del tamaño total del incendio de Gospers Mountain. [141]

A las 10 de la mañana del 14 de diciembre, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur inició una gran quema en el área de Mount Wilson . Debido a las malas condiciones climáticas y a las grandes cargas de combustible, la quema se descontroló rápidamente y amenazó las casas de Mount Wilson. La quema se propagó al este de Mount Wilson Road y el 15 de diciembre, en condiciones cada vez más deterioradas, afectó a Mount Tomah , Berambing y Bilpin . Debido a la confusión en torno al origen del incendio y a las advertencias inexactas, muchos residentes afectados no sabían que la quema se propagó representaba una amenaza para sus propiedades. [143] [144] El fuego destruyó numerosas casas y edificios, y luego saltó la línea Bells de Road hacia Grose Valley . [145]

El 19 de diciembre de 2019, el incendio provocado por el incendio provocado por el RFS Mt Wilson cruzó al sur del río Grose. Esta sección del incendio fue luego anexada por el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur, que declaró un nuevo incendio llamado el incendio de Grose Valley. [146] El 21 de diciembre, un día catastrófico, el incendio provocado por el RFS afectó a Mount Victoria, Blackheath , Bell, Clarence , Dargan y Bilpin , lo que provocó la destrucción de docenas de casas. También se perdieron casas en Lithgow debido a los incendios provocados anteriormente en Glow Worm Tunnel y Blackfellows Hands Trail.

El Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur informó que el incendio de Gospers Mountain estaba controlado el 12 de enero de 2020, y afirmó que el incendio fue causado por un rayo el 26 de octubre. [147] El 4 de febrero de 2020, se declaró extinguido el incendio forestal de Mt Wilson. [148] La cantidad de área quemada por el incendio forestal original de Gospers Mountain sigue siendo controvertida, ya que una parte significativa del incendio fue causada por múltiples incendios forestales separados que aumentaron el área del incendio. El 10 de febrero de 2020, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur anunció que un evento de lluvia torrencial durante la semana anterior había extinguido el incendio de Gospers Mountain. [91] [149]

Entre los incendios más pequeños que se produjeron en la zona se encuentra el de Erskine Creek. [91] Otros incendios en Balmoral, en el extremo sureste de las Montañas Azules, también fueron causados por la quema de fondo del Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur. [150]

El incendio de Gospers Mountain fue ampliamente reportado como el mayor incendio forestal jamás registrado en Australia, que quemó más de 500.000 hectáreas. Una cantidad significativa de la superficie quemada final fue resultado de operaciones de quema inversa del Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur que no se realizaron. El 81% del Área de Patrimonio Mundial de las Montañas Azules se quemó. [31]

.jpg/440px-Sydney_bushfire_smoke_on_George_St_(49197319478).jpg)

El 12 de noviembre de 2019, en las primeras condiciones catastróficas de incendio de la historia de Sídney, se desató un incendio en el Parque Nacional Lane Cove al sur de Turramurra . Con fuertes vientos y calor extremo, el fuego se propagó rápidamente, se salió de control y afectó la interfaz suburbana en el sur de Turramurra . Una casa se incendió en Lyon Avenue, pero fue salvada por los bomberos que respondieron rápidamente. A medida que llegaban más equipos y trabajaban para proteger las propiedades, un avión cisterna C-130 realizó varias descargas retardantes de fuego directamente sobre los bomberos y las casas, salvando el resto del suburbio. El incendio finalmente se controló varias horas después, y un bombero resultó herido y sufrió una fractura de brazo. [151] [152] [153]

Debido a los incendios forestales que ocurrieron en las regiones circundantes, el área metropolitana de Sydney sufrió una peligrosa neblina de humo durante varios días a lo largo de diciembre, con una calidad del aire once veces superior al nivel peligroso en algunos días, [154] [155] haciéndolo incluso peor que el de Nueva Delhi, [156] donde también fue comparado con "fumar 32 cigarrillos" por el Profesor Asociado Brian Oliver, un científico de enfermedades respiratorias de la Universidad de Tecnología de Sydney . [157]

El 10 de diciembre de 2019, el incendio afectó a los suburbios de Nattai y Oakdale , al suroeste de Sídney , seguidos de Orangeville y Werombi , amenazando cientos de casas y provocando la destrucción de un edificio. El incendio continuó ardiendo esporádicamente, saliendo de la espesura del bosque y amenazando propiedades en Oakdale y Buxton el 14 y 15 de diciembre. [ cita requerida ] El incendio se desplazó al sureste hacia las áreas pobladas de Southern Highlands e impactó los municipios de Balmoral , Buxton , Bargo , Couridjah y Tahmoor en el extremo suroeste de Sídney. Se produjeron importantes pérdidas de propiedad en estas áreas, en particular, varios camiones de bomberos fueron invadidos por el fuego, y varios bomberos fueron llevados al hospital y dos fueron trasladados en avión en estado crítico. Más tarde esa noche, dos bomberos murieron cuando un árbol cayó sobre la carretera y su camión cisterna volcó, hiriendo a otros tres miembros de la tripulación. La situación se deterioró el 21 de diciembre cuando el fuego cambió de dirección y atacó Balmoral y Buxton una vez más desde el lado opuesto, con importantes pérdidas materiales en ambas áreas. [158] En la víspera de Año Nuevo se temía que este incendio afectara a las ciudades de Mittagong , Braemar y áreas circundantes.

El 31 de diciembre de 2019, se desató un incendio de pastizales en los bosques en pendiente de Prospect Hill , en el oeste de Sídney , que se dirigió hacia el norte en dirección a Pemulwuy por la autopista Prospect . El incendio afectó a una gran zona industrial y amenazó a numerosas propiedades antes de ser controlado a las 21:30 horas. Se quemaron aproximadamente 10 hectáreas (25 acres) y varios pinos históricos de Monterrey . [159]

A pesar de las protestas, se permitió que el espectáculo de fuegos artificiales de la ciudad de Sídney continuara con una exención especial de las autoridades contra incendios. [160] A pesar de las advertencias de las autoridades, se produjeron numerosos incendios en Sídney como resultado de fuegos artificiales ilegales , incluido un incendio que amenazó propiedades en Cecil Hills en el suroeste de Sídney. [161]

El 4 de enero de 2020, Penrith, un suburbio al oeste de Sídney , registró su día más caluroso registrado con 48,9 °C (120,0 °F), lo que lo convirtió en el lugar más caluroso de la Tierra en ese momento. [162] [163]

El 5 de enero de 2020, se produjo un incendio en un bosque en Voyager Point, en el suroeste de Sídney, que se propagó rápidamente con un fuerte viento del sur y afectó a numerosas casas en Voyager Point y Hammondville . [164] A medida que el incendio avanzaba hacia el norte, las autoridades cerraron la autopista M5 debido a las condiciones de humo y se prepararon para que el fuego afectara al complejo de viviendas New Brighton. Los bomberos en tierra, asistidos por numerosos aviones bombarderos de agua, mantuvieron el fuego al sur de la autopista y evitaron pérdidas de propiedad, conteniendo el fuego a 60 hectáreas (150 acres). [165]

A fines de octubre de 2019, se iniciaron varios incendios en un bosque remoto cerca del lago Burragorang en el Parque Nacional Kanangra-Boyd al suroeste de Sídney. Debido al aislamiento extremo de la zona y al terreno accidentado e inaccesible, los bomberos tuvieron dificultades para contener los incendios a medida que comenzaban a propagarse por el denso bosque. Estos múltiples incendios finalmente se fusionaron para convertirse en el incendio de Green Wattle Creek. El fuego continuó creciendo en tamaño e intensidad, ardiendo hacia el municipio de Yerranderie . Los bomberos realizaron quemas en contracorriente alrededor de la ciudad mientras helicópteros y aviones de ala fija trabajaban para controlar la propagación del incendio. El fuego pasó por Yerranderie pero continuó ardiendo a través del parque nacional hacia el suroeste de Sídney. El 5 de diciembre, en condiciones climáticas severas, el fuego saltó el lago Burragorang y comenzó a arder hacia áreas pobladas dentro del área de Wollondilly .

El 19 de diciembre de 2019, el incendio continuó hacia el este en dirección a la autopista Hume (lo que provocó su cierre durante varias horas) y afectó al municipio de Yanderra . Durante los días siguientes, a medida que el incendio continuó avanzando hacia el sureste, tanto Yerrinbool como Hill Top se vieron amenazados por el fuego. [166]

Además de expandirse hacia el sur y el este, el incendio también se extendió en dirección oeste, en dirección a Oberon . El Centro Correccional de Oberon fue evacuado en previsión del avance del impacto del fuego a lo largo de su flanco occidental. [167] El 2 de enero, el incendio afectó la popular e histórica zona de Jenolan Caves , destruyendo varios edificios, incluida la estación de bomberos local. La pieza central del recinto, Jenolan Caves House , se salvó. [168] El 10 de febrero de 2020, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur anunció que un evento de lluvia torrencial durante la semana anterior había extinguido el incendio de Green Wattle Creek. [91]

.jpg/440px-Smoke_rises_from_the_Tianjara_fire,_viewed_from_HMAS_Albatross_(2).jpg)

El 30 de diciembre de 2019, las condiciones climáticas se deterioraron drásticamente en las áreas del sureste del estado, con grandes incendios que estallaron y se intensificaron en el bosque estatal de Dampier, el valle del río Deua , Badja , Bemboka , Wyndham , Talmalolma y Ellerslie, obstaculizando a los bomberos que ya estaban al límite por los incendios de Currowan , Palerang y Clyde Mountain . [169] Como se pronosticaba que las temperaturas alcanzarían los 41 °C (106 °F) en la costa sur, el primer ministro Berejiklian declaró un estado de emergencia de siete días el 2 de enero de 2020 con efecto a partir de las 9 a.m. del día siguiente, incluida una "zona de salida turística" sin precedentes [170] de 14.000 kilómetros cuadrados (5.400 millas cuadradas) desde Nowra hasta el borde de la frontera norte de Victoria . [80] [81] [82]

Un incendio en la Costa Sur comenzó en Currowan y viajó hasta la costa después de saltar a través de la Princes Highway , amenazando propiedades alrededor de Termeil . A los residentes de Bawley Point , [171] Kioloa , Depot Beach, Pebbly Beach , Durras North y Pretty Beach se les dijo que evacuaran a Batemans Bay o Ulladulla o se quedaran para proteger su propiedad. Se perdió una casa. [ cita requerida ] Al 2 de enero de 2020 [update], el incendio de Currowan estaba ardiendo entre Batemans Bay en el sur, Nowra en el norte y al este de Braidwood en el oeste. El incendio había quemado más de 258.000 hectáreas (640.000 acres) y estaba fuera de control. El incendio de Currowan se había fusionado con el incendio de Tianjara en el Parque Nacional Morton al suroeste de Nowra; y el incendio del bosque Charleys había crecido a lo largo del flanco occidental del incendio; y en el flanco sur del incendio, el fuego se había fusionado con el incendio de Clyde Mountain. [172]

El 26 de diciembre de 2019, el incendio de Clyde Mountain ardía en el lado sur de Kings Highway , en las áreas de Buckenbowra y Runnyford. Alrededor de las 4 am del 31 de diciembre, el incendio había cruzado Princes Highway cerca de Mogo , y la carretera estaba cerrada entre Batemans Bay y Moruya . [173] Alrededor de las 7 am del 31 de diciembre, el incendio impactó el lado sur de Batemans Bay, causando la pérdida de alrededor de diez negocios y daños a muchos otros. El incendio también cruzó Princes Highway en las cercanías de Round Hill e impactó los suburbios residenciales de Catalina , así como los suburbios de playa desde Sunshine Bay hasta Broulee . Los residentes y los turistas se vieron obligados a huir a las playas. [80] El 23 de enero, este incendio volvió a escalar al nivel de emergencia cuando el incendio rugió hacia la ciudad costera de Moruya, una ciudad que en gran medida no se vio afectada por los incendios forestales en las últimas semanas.

En el cercano parque Conjola , numerosas casas se perdieron cuando las brasas saltaron al lago Conjola, cayeron en las cunetas e iluminaron las casas. En una calle solo quedaban cuatro casas en pie. Al 2 de enero de 2020 [update], al menos dos personas murieron y una mujer estaba desaparecida. [174] Las aldeas aisladas de Bendalong y Manyana y Cunjurong Point también fueron incendiadas, y los turistas fueron evacuados el 3 de enero de 2020. Al 6 de enero de 2020 [update], todas siguen sin electricidad. [175]

A partir del 5 de enero de 2020 [update], en el valle de Bega , el incendio de la frontera que comenzó en el noreste de Victoria estaba ardiendo hacia el norte en Nueva Gales del Sur hacia la ciudad principal de Eden , y había afectado a los asentamientos de Wonboyn y áreas circundantes, incluyendo Kiah, Lower Towamba y partes de Boydtown . Parte del incendio estaba ardiendo en un país inaccesible y continuó dirigiéndose en dirección noroeste hacia Bombala , así como hacia el norte hasta el sur de Nethercote. El incendio había quemado más de 60.000 hectáreas (150.000 acres) y estaba fuera de control. [176] [177] El 2 de febrero de 2020 en el valle de Bega, el incendio de la frontera de 177.000 hectáreas (437.377 acres) avanzó hacia el norte, mientras que otros tres incendios forestales en el suroeste se habían fusionado en uno. Kristy McBain , alcaldesa del consejo del condado de Bega Valley, dijo que se habían perdido más de 400 propiedades y hogares después de 34 días de actividad de incendios en el área. [178]

El 9 de febrero de 2020, el Servicio Rural de Bomberos de Nueva Gales del Sur anunció que un evento de lluvias torrenciales durante la semana anterior había extinguido los incendios de Morton y Currowan, [91] habiendo este último quemado 499.621 hectáreas (1.234.590 acres) en 74 días y destruido 312 casas. [179]

El 30 de diciembre de 2019, el incendio de Green Valley que ardía al este de Albury, cerca de Talmalmo (que había comenzado el día anterior), se convirtió en un incendio sin precedentes en Snowy Valleys [180] como resultado de condiciones locales extremas. La columna de humo se elevó a unos 8000 metros (26 000 pies) y desarrolló una nube pirocumulonimbus , convirtiéndose en una tormenta de fuego . El resultado fue extremo: los equipos en el terreno describieron el viento como de más de 100 km/h (62 mph), con incendios puntuales que comenzaron a más de 5 km (3,1 mi) por delante del frente de fuego principal. [ cita requerida ]

Los bomberos describieron lo que creyeron que era un tornado generado por la tormenta de fuego, que comenzó a aplanar árboles y volcó un pequeño vehículo de bomberos. Luego, el tornado impactó a un equipo de bomberos que trabajaba para proteger una propiedad, volcando su camión cisterna y atrapando a la tripulación dentro, que luego fue invadida por el fuego. Un bombero murió y varios otros resultaron heridos; uno fue trasladado en avión a Melbourne y dos a Sídney. [181] [182] [183] [184] [185] [186]

Se cree que el incendio de Dunns Road se inició por un rayo el 28 de diciembre en una plantación privada de pinos cerca de Adelong . [187] [188] En el área del gobierno local de Snowy Valleys , el 2 de enero de 2020, el incendio de Dunns Road había ardido al sur de la autopista Snowy Mountains en la cordillera Ellerslie cerca de Kunama . Se quemaron más de 130.000 hectáreas (320.000 acres) y el incendio estaba fuera de control. El NSWRFS emitió una orden de evacuación a los residentes en las áreas de Batlow y Wondalga . Los residentes y visitantes del Parque Nacional Kosciuszko fueron evacuados y el parque nacional fue cerrado. 155 reclusos del Centro Correccional Mannus cerca de Tumbarumba fueron evacuados. [189] [190] [191] [192]

El 3 de enero de 2020, el incendio de Dunns Road ardió desde Batlow hasta el Parque Nacional Kosciuszko, quemando gran parte de la parte norte del parque. El incendio causó daños importantes, dañando gravemente el Selwyn Snow Resort , destruyendo estructuras en la ciudad de Cabramurra y destruyendo casi por completo el recinto declarado patrimonio (y cuna del esquí en Australia) de Kiandra . El antiguo palacio de justicia histórico de Kiandra [193] quedó solo con sus paredes en pie después de un incendio tan caliente que el vidrio y el aluminio de las ventanas se derritieron. [194] También se teme que varias cabañas de altura , incluidas Wolgal Hut y Pattinsons Hut cerca de Kiandra, hayan sido destruidas. [195] Para el 11 de enero, tres incendios se habían fusionado – el incendio de Dunns Road, el de East Ournie Creek y el de Riverina's Green Valley – y habían creado un "megaincendio" de 600.000 hectáreas (1.482.632 acres), que ardía al sur de las Snowy Mountains. [196]

_Lockheed_EC-130Q_Hercules_departing_HMAS_Albatross.jpg/440px-Coulson_Aviation_(N134CG)_Lockheed_EC-130Q_Hercules_departing_HMAS_Albatross.jpg)

El 23 de enero de 2020, un gran avión cisterna Lockheed C-130 Hercules se estrelló cerca de Cooma mientras lanzaba bombas de agua sobre un incendio, lo que provocó la muerte de los tres tripulantes estadounidenses a bordo. [48] [83]

El 1 de febrero de 2020, se emitieron advertencias de emergencia por el incendio de Orroral y el incendio de Clear Range que amenazaban a Bredbo al norte de Cooma. [197]

El 21 de noviembre de 2019, los rayos provocaron una serie de incendios en East Gippsland, poniendo en peligro inicialmente a las comunidades de Buchan , Buchan South y Sunny Point. [198] El 20 de diciembre, el ramal Marthavale-Barmouth se expandió, poniendo en gran peligro a la comunidad de Tambo Crossing. [ cita requerida ]

El primer día de un partido de cricket de dos días entre Victoria XI y Nueva Zelanda en Melbourne fue cancelado debido a condiciones de calor extremo. [199]

El 30 de diciembre de 2019, hubo tres incendios activos en East Gippsland con un área combinada de más de 130.000 hectáreas (320.000 acres), y otro en el noreste del estado cerca de Walwa en dirección sureste hacia Cudgewa . [ cita requerida ] Se emitió una advertencia de evacuación para la ciudad de Goongerah en East Gippsland , que está rodeada de bosques antiguos de alto valor, así como Cudgewa. [ cita requerida ] El mismo día, se desató un incendio en Plenty Gorge Parklands, situado en los suburbios del norte de Melbourne entre Bundoora , Mill Park , South Morang , Greensborough y Plenty . [ 200 ] [ 201 ]

Los incendios llegaron a la ciudad de Mallacoota alrededor de las 8 am AEDT del 31 de diciembre de 2019. A las 11 am AEDT del 31 de diciembre, los incendios habían comenzado a acercarse a la ciudad vacacional de Lakes Entrance . [202] A pesar de la recomendación de que se evacuaran grandes porciones de East Gippsland, aproximadamente 30.000 turistas decidieron permanecer en la región. Aproximadamente 4.000 personas, incluidos 3.000 turistas, permanecieron en Mallacoota cuando el incendio comenzó a acercarse más a la ciudad, cortando carreteras en el proceso; Mallacoota no había recibido una advertencia de evacuación el 29 de diciembre. [203] [ verificación fallida ] El 3 de enero, aproximadamente 1.160 personas de Mallacoota fueron evacuadas en los buques de guerra HMAS Choules y MV Sycamore . [204] [205] En la aldea rural de Sarsfield, 200 de las 276 propiedades de la zona se vieron afectadas por el fuego, con 73 viviendas perdidas y el 49,2% del paisaje quemado.

El 2 de enero de 2020 a las 11 p. m. AEDT, el primer ministro de Victoria, Daniel Andrews, declaró el estado de desastre en virtud de las disposiciones de la Ley de Gestión de Emergencias de Victoria para los condados de East Gippsland , Mansfield , Wellington , Wangaratta , Towong y Alpine , y los centros turísticos alpinos de Mount Buller , Mount Hotham y Mount Stirling . El comisionado de gestión de emergencias, Andrew Crisp, declaró que se habían quemado 780 000 hectáreas (1 900 000 acres), incluidas 100 000 hectáreas (250 000 acres) cerca de Corryong, en el noreste del estado, y que había cincuenta incendios en marcha. [206] El 3 de enero, Andrews dijo que se había confirmado la muerte de dos personas a causa de los incendios de East Gippsland. [207]

El 6 de enero de 2020, Andrews dijo que los incendios forestales habían quemado 1,2 millones de hectáreas (3 millones de acres) en el este y noreste de Victoria y que se confirmó la pérdida de 200 viviendas. [208]

El 13 de enero de 2020, dos incendios forestales ardían a nivel de emergencia en Victoria a pesar de las condiciones más suaves, uno a unos 8 km al este de Abbeyard y el otro en East Gippsland, afectando a Tamboon, Tamboon South y Furnel. [209]

El 23 de enero de 2020, todavía había 12 incendios en Victoria, los más fuertes en East Gippsland y el noreste. El incendio de Buldah en East Gippsland estaba en el nivel de vigilancia y actuación y el resto estaban en el nivel de aviso. La mayoría de los 44 incendios provocados por rayos secos fueron controlados rápidamente por los bomberos. Las fuertes lluvias en la región de Melbourne trajeron poco alivio a las regiones afectadas por los incendios forestales. Andrews dijo que las lluvias podrían traer nuevos peligros para los bomberos, incluidos deslizamientos de tierra. [210]

El 30 y 31 de enero de 2020, hubo un clima muy cálido en Victoria, Nueva Gales del Sur y Australia del Sur que generó un alto riesgo de incendio, con varios incendios forestales sin control que aún continúan activos. Se emitió una advertencia de emergencia para Bendoc, Bendoc Upper y Bendoc North el 30 de enero. [211]

El 20 de febrero de 2020, el controlador de incidentes de Bairnsdale, Brett Mitchell, declaró "contenido" el enorme incendio forestal de East Gippsland que había ardido durante tres meses. Las lluvias recientes también contribuyeron a contener los incendios forestales de Omeo, Anglers Rest, Cobungra, Bindi, Hotham Heights, Glen Valley, Benambra, Swifts Creek, Omeo, Ensay, Tongio, Blue Rag Range, Dargo y Tabberabbera. El incendio del complejo Snowy en el extremo este era el único incendio importante que aún seguía ardiendo en Victoria. [212]

Todos los incendios importantes en Victoria, incluido el incendio del complejo Snowy, fueron declarados contenidos el 27 de febrero de 2020. [213]

.jpg/440px-Satellite_image_of_bushfire_smoke_over_Eastern_Australia_(December_2019).jpg)

El 7 de septiembre de 2019, varios incendios fuera de control amenazaron municipios en el sureste y norte de Queensland, destruyendo once casas en Beechmont , siete casas en Stanthorpe y una casa en Mareeba . [214] Al día siguiente, el albergue y las cabañas catalogados como patrimonio en el icónico albergue natural australiano Binna Burra Lodge fueron destruidos en el incendio forestal que consumió casas residenciales en Beechmont el día anterior. [215]

El 9 de septiembre, un gran incendio afectó la zona de Peregian Beach , en Sunshine Coast , y dañó gravemente diez casas. [216] En diciembre de 2019, Peregian Springs y las áreas circundantes se vieron amenazadas por incendios forestales por segunda vez en un par de meses. No se confirmó la pérdida de viviendas en el área de Peregian Springs en este incendio forestal. [217]

Debido al deterioro de las condiciones de los incendios y a los incendios que amenazan viviendas en todo el estado, el 9 de noviembre se declaró el estado de emergencia por incendios en 42 áreas de gobierno local en el sur, centro , norte y extremo norte de Queensland. [218] 14 casas fueron destruidas en el área de Yeppoon a mediados de noviembre de 2019. [219]

El 27 de octubre se inició un incendio en un terreno inaccesible para la Defensa en la zona militar de Canungra . Los bomberos intentaron contener el fuego con un intenso bombardeo de agua hasta que las condiciones meteorológicas mejoraron. El 8 de noviembre, el fuego atravesó la línea de contención e impactó 30 casas en Lower Beechmont , lo que provocó la evacuación de la aldea. Se salvaron todas las casas, aunque se perdieron un cobertizo y varias dependencias. [220]

El 11 de noviembre se inició un incendio en la zona de Ravensbourne , cerca de Toowoomba , que quemó más de 20.000 hectáreas (49.000 acres) de monte en varios días, destruyendo seis casas. [221] A las 8 de la mañana, la calidad del aire en Brisbane alcanzó niveles sin precedentes ( Woolloongabba PM2.5 238,8 μg /m3 ) . La directora de salud de Queensland, la Dra. Jeannette Young , instó a los residentes a permanecer en el interior y a no realizar esfuerzos físicos. [222]

El 13 de noviembre, un helicóptero lanzamisiles se estrelló mientras luchaba contra las llamas que amenazaban a la pequeña comunidad de Pechey . Aunque el helicóptero Bell 214 quedó completamente destruido, el piloto salió caminando con heridas leves. [223]

El 23 de noviembre se revocó el estado de emergencia por incendios y se establecieron prohibiciones de incendios extendidas en las áreas de gobierno local que anteriormente se vieron afectadas por esta declaración. [ cita requerida ]

El 6 de diciembre se produjo un incendio en una casa en Bundamba que se extendió rápidamente a los matorrales cercanos y los servicios de bomberos y emergencias de Queensland pusieron en alerta esa tarde. Al día siguiente, tras empeorar las condiciones, el incendio pasó a ser una advertencia de emergencia y comenzó a amenazar las viviendas de la comunidad local. El incendio destruyó un contenedor de carga lleno de fuegos artificiales y se ordenó la evacuación de los residentes dentro de la zona de exclusión de 3 kilómetros cuadrados (1,2 millas cuadradas). Una casa quedó destruida. [224]

El 8 de noviembre se produjo un incendio forestal en una zona forestal situada al oeste del municipio de Jimna, lo que provocó que los servicios de bomberos y emergencias de Queensland emitieran una alerta de "vigilancia y actuación". El incendio provocó la evacuación de toda la ciudad. [225]

El 11 de noviembre de 2019 se emitió una alerta de emergencia por incendio forestal en Port Lincoln , en la península de Eyre , y un incendio sin control se dirigía hacia la ciudad. El Servicio de Bomberos de Australia del Sur ordenó el envío de diez hidroaviones a la zona para ayudar a 26 equipos de tierra en el lugar. SA Power Networks desconectó la energía de la ciudad. [226]

El 20 de noviembre de 2019 se produjo un gran incendio en la península de Yorke que amenazó a las ciudades de Yorketown y Edithburgh . [227] Destruyó al menos once casas y quemó aproximadamente 5000 hectáreas (12 000 acres). Se cree que el incendio se inició a partir de un transformador eléctrico que emitió chispas. [228] Se utilizó un avión de bombardeo de agua Boeing 737 de Nueva Gales del Sur, además de los Air Tractor AT-802 de Australia del Sur , para proteger la ciudad de Edithburgh. [229]

El 20 de diciembre, los incendios se apoderaron de las colinas de Adelaida y cerca de Cudlee Creek en Mount Lofty Ranges . [230] Los vientos iniciales del sureste pusieron las ciudades de Lobethal y Lenswood en la línea del fuego, y a la mañana siguiente los vientos habían cambiado a norte-noroeste, amenazando otras ciudades. [231] Los incendios mataron a una persona, [232] más de 70 casas fueron destruidas, así como más de 400 dependencias y 200 automóviles. [233] Las celebraciones navideñas anuales en Lobethal fueron canceladas. [234] Los voluntarios de las áreas de Adelaida y Mount Lofty Ranges respondieron al incidente que se estaba desarrollando; esto resultó en que varios camiones de bomberos fueran invadidos por el fuego que se movía rápidamente. Uno de los camiones involucrados fue Seaford 34. Las cuadrillas estaban tratando de evitar que el fuego cruzara Croft Rd en Cudlee Creek cuando un cambio de viento empujó el frente del fuego hacia ellos. Los equipos se refugiaron en su camión hasta que pasó el frente de fuego. Los equipos fueron llevados de vuelta a Lobethal , donde continuaron ayudando a los miembros de la comunidad mientras caminaban con la protección de los bienes a medida que avanzaba el frente de fuego. También el 20 de diciembre, un incendio forestal fuera de control se produjo cerca de Angle Vale , que comenzó en la Northern Expressway y ardió a través de Buchfelde y cruzó el río Gawler . A las 11:07 am ACDT, el fuego ardía en condiciones climáticas catastróficas y se emitió una advertencia de emergencia para Hillier , Munno Para Downs , Kudla , Munno Para West y Angle Vale. Una casa fue destruida. [235]

El 3 de enero se emitió otra alerta de emergencia por un incendio cerca de Kersbrook . En su mayor extensión, la zona de alerta se superpuso con áreas que unos días antes habían estado bajo alerta por el incendio de Cudlee Creek. Los aviones cisterna lanzaron 21 cargas en poco más de una hora antes de que oscureciera, y 150 bomberos en 25 camiones, además de transportadores de agua a granel y equipos de movimiento de tierras, limitaron el avance del incendio a 18 hectáreas (44 acres). [236]

En la isla Canguro, a partir del Parque Nacional Flinders Chase , el incendio forestal de Ravine quemó más de 15 000 hectáreas (37 000 acres) y el 3 de enero de 2020 se emitió una advertencia de emergencia por incendio forestal a medida que el fuego avanzaba hacia la bahía de Vivonne y se evacuó la ciudad de Parndana . [237] [238] El 4 de enero se confirmó la muerte de al menos dos personas. [239] Al 6 de enero de 2020, [update]se habían quemado aproximadamente 170 000 hectáreas (420 000 acres), lo que representa aproximadamente un tercio de la isla. Los incendios seguían ardiendo fuera de control, y los bomberos trabajaban para contenerlos y controlarlos antes del clima potencialmente caluroso y ventoso programado para más adelante en la semana. Después de los daños causados por el fuego a una planta de tratamiento de agua, se pidió a los residentes que conservaran agua y se transportó un poco de agua a las ciudades de la isla. Existían preocupaciones por el futuro de la fauna amenazada, como las cacatúas negras brillantes , los dunnarts de la isla Canguro y los koalas. Las autoridades declararon que los koalas llevados al continente para recibir tratamiento no pueden regresar a la isla por si traen consigo enfermedades. [h] [240]

El 13 de noviembre se produjeron dos incendios forestales en Geraldton que dañaron viviendas y pequeñas estructuras. [241] [242]

El 11 de diciembre a las 14:11 se produjo un incendio en Yanchep , lo que desencadenó inmediatamente una alerta de emergencia para Yanchep y Two Rocks . El incendio provocó la explosión de una estación de servicio. [243] El 12 de diciembre, temperaturas superiores a los 40 °C (104 °F) exacerbaron el incendio y el área de alerta de emergencia se duplicó, incluidas partes de Guilderton y Brenton Bay más al norte. [244] [245] El 13 de diciembre, el aumento de las condiciones de temperatura provocó que el incendio arrasara más de 5000 hectáreas (12 000 acres), con un frente de fuego de más de 1,5 kilómetros (0,93 millas) de longitud. Al 13 de diciembre de 2019 [update], el área de alerta de emergencia se extendía desde Yanchep al norte hasta Lancelin a más de 40 km (25 millas) de distancia. [246] Para el 16 de diciembre, el incendio se consideró contenido y la alerta se degradó a vigilancia y acción. [247] Aproximadamente 13.000 hectáreas (32.000 acres) fueron quemadas; sólo dos edificios resultaron dañados, ambos dentro del primer día desde que comenzó el incendio. [247]

En diciembre, los incendios en la región alrededor de Norseman bloquearon el acceso a la autopista Eyre y a la llanura de Nullarbor y provocaron el bloqueo de las carreteras de la región, [248] con el fin de evitar que se repitiera la muerte de camioneros en la Gran Autopista del Este en 2007. [249] [250]

Entre el 26 de diciembre de 2019 y el 1 de enero de 2020, como resultado de la caída de un rayo, [251] un incendio arrasó 40.000 hectáreas (99.000 acres) de tierra en el Parque Nacional Stirling Range en el suroeste del estado, quemando más de la mitad del parque. [252] La nube de pirocúmulos de los incendios se podía ver a 80 km (50 mi) al sur en Albany . [253] Para el día de Año Nuevo de 2020, un equipo de 200 bomberos devolvió el incendio al nivel de advertencia sin ninguna pérdida de vidas o daños materiales importantes (una cabaña de guardabosques y senderos para caminatas fueron destruidos). [253] Sin embargo, los conservacionistas expresaron su preocupación por la posible pérdida de flora y fauna raras y únicas que viven en el parque, que contiene más de 1500 de esas especies dentro de sus límites, incluida una población rara de quokkas (una de las pocas en Australia Occidental continental). [252] Un político local, bomberos, agricultores y operadores turísticos pidieron al Ministro de Emergencias de Australia Occidental, Fran Logan, que invirtiera en activos locales de lucha contra incendios en la zona para asegurarse de que el destino turístico estuviera protegido adecuadamente. [253]

El último incendio de la temporada de incendios forestales 2019-2020 en Australia Occidental comenzó en el lago Clifton, dentro del condado de Waroona, el 2 de mayo y se extinguió el 3 de mayo. [254] La zona del lago Clifton sufrió graves daños durante la temporada de incendios forestales 2010-2011. [255]

A finales de octubre de 2019, cuatro incendios forestales ardían cerca de Scamander , Elderslie y Lachlan. Se emitieron advertencias de emergencia en Lulworth, Bothwell y Lachlan. Un gran incendio cerca de Swansea también quemó más de 4.000 hectáreas (9.900 acres). Posteriormente, los rayos provocaron múltiples incendios en el suroeste de Tasmania . [256] [257] El 20 de diciembre de 2019, se inició un incendio en el noreste, que se extendió a 15.000 hectáreas (37.000 acres) y destruyó una casa; un hombre fue acusado de iniciar el incendio. [258]

En enero de 2020, continuaron ardiendo dos incendios: el 29 de diciembre, en el valle de Fingal, en el noreste de Tasmania, y el 30 de diciembre, en Pelham, al norte de Hobart. Al 16 de enero de 2020, [update]el incendio de Fingal había quemado más de 20 000 hectáreas (49 000 acres) y el de Pelham, más de 2100 hectáreas (5200 acres). [259] [260]

En el Territorio de la Capital Australiana (ACT), la capital nacional, Canberra, se vio envuelta en una espesa nube de humo el día de Año Nuevo, causada por los incendios forestales que ardían en las cercanías de Nueva Gales del Sur. Ese día, la calidad del aire en la capital era la peor de todas las ciudades del mundo, con unas 23 veces el umbral para ser considerada peligrosa. Las condiciones continuaron al día siguiente y Australia Post detuvo las entregas postales en el ACT para proteger a los trabajadores del humo. [261] [262] La primera muerte directamente relacionada con la mala calidad del aire también se registró el 2 de enero. Una mujer mayor viajaba en avión de Brisbane a Canberra. Cuando salió del avión a la pista inundada de humo, sufrió dificultad respiratoria y luego murió. [263] El 2 de enero de 2020, el ACT declaró el estado de alerta; [264] que se extendió el 12 de enero cuando el incendio fusionado de Dunns Road ardió a siete kilómetros (cuatro millas) de la frontera sudoeste del Territorio. [265] El humo de los incendios forestales cercanos continuó afectando gravemente la calidad del aire de Canberra de manera intermitente durante enero de 2020.

Desde al menos el 6 de enero de 2020 se inició un incendio forestal cerca de Hospital Hill, en el Parque Nacional Namadgi , que fue extinguido el 9 de enero. [266]

El 22 de enero de 2020 se inició un incendio forestal en el bosque de secuoyas de Pialligo ; alcanzó el nivel de emergencia, amenazando a Beard and Oaks Estate . Al día siguiente se inició un segundo incendio forestal, el incendio de Kallaroo, que más tarde durante el día se fusionó con el incendio del bosque de secuoyas formando el incendio de Beard; el fuego saltó el río Molonglo y amenazó los suburbios de Beard , Harman and Oaks Estate al quemar 424 hectáreas (1050 acres). El aeropuerto de Canberra estuvo cerrado durante un día. [267] [268] [269] El incendio destruyó una instalación, cuatro dependencias y tres vehículos. [270]

El 27 de enero de 2020 se inició un incendio forestal en el valle de Orroral en el parque nacional de Namadgi. A la 1:30 p. m., un helicóptero MRH-90 Taipan del ejército que realizaba un reconocimiento de los lugares de aterrizaje para los equipos de extinción de incendios en áreas remotas intentó aterrizar para un descanso cuando su luz de aterrizaje encendió un incendio en la hierba seca. [271] [272] [273] La tripulación esperó hasta aterrizar en el aeropuerto de Canberra alrededor de las 2:15 p. m. para notificar a la Agencia de Servicios de Emergencia del ACT, mientras tanto, una torre de bomberos había detectado humo blanco a la 1:49 p. m. y se había iniciado una búsqueda para localizar el incendio. [271] En la mañana del 28 de enero, el incendio había crecido a 2575 hectáreas (6360 acres) y estaba a 9 kilómetros (5,6 millas) de la ciudad de Tharwa . [274] [275] Se declaró una advertencia de emergencia para Tharwa y los suburbios del sur de Canberra, particularmente Banks , Gordon y Conder , justo después de la 1:30 pm AEST del 28 de enero. El Ministro Principal Andrew Barr describió el incendio como la mayor amenaza para Canberra desde los incendios forestales de Canberra de 2003. [ 276] [272] Al mediodía del 31 de enero, Barr declaró el estado de emergencia para el ACT, la primera vez que se producía una acción de este tipo desde los incendios de 2003. [277] Mientras el incendio del valle de Orroral ardía sin control, se informaron muchos casos de "turismo de desastres" en el sur suburbano de Tuggeranong, con personas conduciendo a los suburbios para ver el incendio y tomar fotografías; a su vez, bloqueando el tráfico. [278] El incendio del valle de Orroral se degradó a estado de "aviso" el 5 de febrero y se declaró extinguido el 27 de febrero. [279]

El Territorio del Norte atravesó una temporada anual de incendios forestales relativamente promedio en lo que respecta a la superficie de tierra quemada, en comparación con la escala de incendios forestales observados en otras áreas de Australia. A pesar de esto, se quemaron aproximadamente 6,8 millones de hectáreas (17 millones de acres), una superficie que contribuyó significativamente a la superficie total quemada por incendios forestales en el país. Se perdieron cinco casas a causa de los incendios forestales en el Territorio. [280]

Se han registrado varios incendios forestales a gran escala en la historia de Australia. Los incendios generalizados de 1938-1939 en Victoria, Nueva Gales del Sur, Australia del Sur y el ACT también ganaron titulares internacionales cuando los incendios entraron en los suburbios de Sydney, [281] al igual que los incendios de la costa este de 1994. Los incendios forestales del Jueves Negro de 1851 conmocionaron a la Australia colonial con su ferocidad, quemando una cuarta parte de lo que ahora es Victoria (alrededor de 5 millones de hectáreas (12 millones de acres)). [282] Menos conocido es que alrededor de 117 millones de hectáreas (290 millones de acres), o el 15 por ciento de la masa terrestre de Australia, sufrieron incendios en el verano de 1974-5 . Nueva Gales del Sur se vio gravemente afectada nuevamente y tres personas murieron. Sin embargo, los incendios se produjeron principalmente en áreas del interior escasamente pobladas. [56] Los cinco incendios más mortíferos fueron: el Sábado Negro de 2009 en Victoria (173 personas murieron, 2000 hogares perdidos); Miércoles de Ceniza de 1983 en Victoria y Australia del Sur (75 muertos, casi 1.900 viviendas); Viernes Negro de 1939 en Victoria (71 muertos, 650 casas destruidas), Martes Negro de 1967 en Tasmania (62 personas y casi 1.300 viviendas); y los incendios de Gippsland y el Domingo Negro de 1926 en Victoria (60 personas asesinadas en un período de dos meses). [283]

A nivel nacional, la Universidad Nacional de Australia describió el año de incendios de 2019 como "cercano al promedio" [284] y el año de incendios de 2020 como "inusualmente pequeño". [285]

A mediados de diciembre de 2019, un análisis de la NASA reveló que desde el 1 de agosto, los incendios forestales de Nueva Gales del Sur y Queensland habían emitido 250 millones de toneladas (280 millones de toneladas cortas) de dióxido de carbono (CO 2 ). [286] Un estudio de septiembre de 2021 que utilizó datos satelitales estimó que las emisiones de CO 2 de los incendios de noviembre de 2019 a enero de 2020 fueron de ~715 millones de toneladas, [37] [38] [39] aproximadamente el doble de las estimaciones anteriores. [35] [36] En comparación, en 2018, las emisiones totales de carbono de Australia fueron equivalentes a 535 millones de toneladas (590 millones de toneladas cortas) de CO 2 , – las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero superaron las emisiones normales anuales de incendios forestales y combustibles fósiles de Australia en ~80%. [286] Si bien el carbono emitido por los incendios normalmente sería reabsorbido por la regeneración forestal, esto tomaría décadas y podría no ocurrir en absoluto si la sequía prolongada ha dañado la capacidad de los bosques para regenerarse por completo. [286]

En diciembre de 2019, el índice de calidad del aire (AQI) alrededor de Rozelle , un suburbio interior de Sydney, alcanzó 2,552 o más de 12 veces el nivel peligroso de 200. [287] El nivel de partículas finas, conocidas y medidas globalmente como PM2.5, alrededor de Sydney también se midió en 734 microgramos (0,01133 gr ) o el equivalente a 37 cigarrillos. [288] El 1 de enero de 2020, el AQI alrededor de Monash , un suburbio de Canberra, se midió en 4,650, o más de 23 veces el nivel peligroso y alcanzó un máximo de 7,700. [289]

El día de Año Nuevo de 2020 en Nueva Zelanda, una capa de humo de los incendios australianos cubrió toda la Isla Sur , dando al cielo una neblina de color amarillo anaranjado. La gente de Dunedin informó haber olido humo en el aire. [290] El Servicio Meteorológico declaró que el humo no tendría ningún efecto adverso en el clima o la temperatura del país. [290] [291] El humo se movió sobre la Isla Norte al día siguiente, pero comenzó a dispersarse y no fue tan intenso como lo fue sobre la Isla Sur el día anterior; mientras tanto, el viento del Océano Pacífico Sur disipó el humo sobre la Isla Sur. [292] El humo afectó a los glaciares del país, dando un tinte marrón a la nieve. [293] El 5 de enero de 2020, más humo flotó sobre la Isla Norte, tiñendo de naranja el cielo de Auckland . [294] Para el 7 de enero de 2020, el humo había recorrido aproximadamente 11.000 kilómetros (6.800 millas) a través del Océano Pacífico Sur hasta Chile, Argentina , [33] [34] Brasil y Uruguay . [295]

El profesor Chris Dickman, miembro de la Academia Australiana de Ciencias de la Universidad de Sídney , estimó el 8 de enero de 2020 que más de mil millones de animales murieron a causa de los incendios forestales en Australia; mientras que más de 800 millones de animales perecieron en Nueva Gales del Sur. La estimación se basó en un informe de 2007 del Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza (WWF) sobre los impactos de la tala de tierras en la vida silvestre australiana en Nueva Gales del Sur que proporcionó estimaciones de la densidad de población de mamíferos, aves y reptiles en la región. El cálculo de Dickman se había basado en estimaciones conservadoras y la mortalidad real podría ser mayor. La cifra proporcionada por Dickman incluía mamíferos (excluidos los murciélagos), aves y reptiles; y no incluía ranas, insectos u otros invertebrados. [296] Otras estimaciones, que incluyen animales como murciélagos, anfibios e invertebrados, también sitúan el número de muertos en más de mil millones. [297]

Un estudio de 2020 estimó que al menos 3 mil millones de vertebrados terrestres solamente fueron desplazados o muertos por los incendios, y que los reptiles (que tienden a tener densidades de población más altas en las áreas afectadas en comparación con otros vertebrados) representan más de dos tercios de los afectados, mientras que las aves, los mamíferos y los anfibios representan el otro tercio. [298]

Los ecologistas temían que algunas especies en peligro de extinción fueran llevadas a la extinción por los incendios. [299] [300] Aunque los incendios forestales no son poco comunes en Australia, por lo general son de menor escala e intensidad y solo afectan pequeñas partes de la distribución general de donde viven las especies. Los animales que sobrevivieron a un incendio forestal aún podían encontrar hábitats adecuados en las inmediaciones, lo que no era el caso cuando una distribución entera era diezmada en un evento intenso. Además de la mortalidad inmediata por los incendios, hubo mortalidades continuas después de los incendios por inanición, falta de refugio y ataques de depredadores como zorros y gatos salvajes que se sienten atraídos por las áreas afectadas por el fuego para cazar. [301] Al menos una especie, el gecko de cola de hoja de Kate , tuvo la totalidad de su hábitat quemado por los incendios, mientras que el potoroo de patas largas tuvo más del 82% del hábitat quemado. [302] Si bien muchas especies en peligro de extinción lograron sobrevivir a los incendios, aunque con poblaciones severamente impactadas que no sobrevivirán en el largo plazo sin una influencia humana importante, [303] otras especies como la araña microtramposa de la Isla Canguro y la araña asesina de la Isla Canguro no han sido avistadas desde entonces. [304]

En la isla Canguro, la tercera isla más grande de Australia y conocida como la "Isla Galápagos" de Australia, [305] un tercio de la isla fue quemada. Grandes partes de la isla están designadas como áreas protegidas y albergan animales como leones marinos, pingüinos, canguros, koalas, zarigüeyas pigmeas , bandicuts pardos del sur , abejas de Liguria, dunnarts de la isla Canguro y varias aves, incluidas las cacatúas negras brillantes . [306] La NASA estimó que el número de koalas muertos podría ser tan alto como 25.000 o aproximadamente la mitad de la población total de la especie en la isla. [307] Se cree que una cuarta parte de las colmenas de las abejas melíferas de Liguria que habitaban la isla fueron destruidas. [306] Tanto el dunnart de la isla Canguro como las subespecies de la cacatúa negra brillante de la isla Canguro están en peligro de extinción y solo se encuentran en la isla Canguro. Antes de los incendios, había menos de 500 cacatúas dunnart de la Isla Canguro y alrededor de 380 cacatúas negras brillantes de la Isla Canguro. [308] [309]

La pérdida de unos 8.000 koalas ( Phascolarctos cinereus ) causó preocupación. Se los considera vulnerables a la extinción, aunque no están funcionalmente extintos. [310]

Due to the extremely dry conditions, some remnant areas of rainforest that—unlike most Australian vegetation—have not evolved and adapted to fire, were burnt in 2019–2020. This may have permanently reduced the extent of the 80-million year old rainforests, which were already scarce due to previous land clearing for agriculture and logging. Smaller, isolated remnant pockets of rainforest were totally destroyed and unlikely to recover, leading to local extinctions of rainforest flora and fauna. It was notable that the normally wet rainforest areas on the margins of schlerophyll forest, did not perform their usual role as a barrier to the spread of fire but were burnt.[311][312][313][314]

Moreover, the fires caused widespread phytoplankton blooms by causing oceanic deposition of wildfire aerosols, enhancing marine productivity.[315][316] While these increased oceanic carbon dioxide uptake, the amount – estimated to be slightly more than 152±83.5 million tons[316] – did not counterbalance the ~715 million tons[39] of CO2 the fires emitted.

Fire damaged 500-year-old rock art at Anaiwan in northern New South Wales, with the intense and rapid temperature change of the fires cracking the granite rock. This caused panels of art to fracture and fall off the huge boulders that contain the galleries of art.[317]

At the Budj Bim heritage areas in Victoria the Gunditjmara people reported that when they inspected the site after fires moved across it, they found ancient channels and ponds that were newly visible after the fires burned much of the vegetation off the landscape.[318][319]

After fire burnt out a creek on a property at Cobargo, NSW, on New Year's Eve, a boomerang carved by stone artefact was found.[320]

The New South Wales Rural Fire Service is the lead agency for bush fires in New South Wales and formed the bulk of the primary response to the fires, mobilising thousands of firefighters and several hundred firefighting vehicles. They were heavily supported by Fire & Rescue New South Wales, as well as the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and the Forestry Corporation of NSW, who hold jurisdiction over national parks and forests across the state respectively. Additional local firefighting resources were also used from agencies such as Air Services Australia and Sydney Trains.[45]

Numerous interstate agencies deployed firefighting resources into New South Wales, including several hundred firefighters from the Victorian Country Fire Authority,[321] along with crews from the Melbourne Metropolitan Fire Brigade,[322] the South Australian Country Fire Service,[323] the South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service,[323] the South Australian Department of Environment and Water,[323] and the Queensland Fire and Emergency Service.[324]

Despite the substantial loss of property and loss of life, firefighters as of January 2020 managed to save over 16,000 structures from direct fire impact in addition to countless lives.[325]

Multiple other New South Wales emergency services assisted in the response, including NSW Ambulance that provided ongoing pre-hospital care to victims of the fires including firefighters, NSW Police that worked to ensure public safety was maintained through road closures and evacuations and the NSW State Emergency Service that assisted with logistical support.[325] With brush-tailed rock-wallabies and much of the indigenous wildlife population in parts of New South Wales were left without food or water, the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service airdropped approximately 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb) vegetables on the known habitats.[326] A joint operation by the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and NSW Rural Fire Service was mounted to protect the critically endangered Wollemia pines growing in Wollemi National Park. Fire retardant was dropped from air tankers, and an irrigation system was installed on the ground by specialist firefighters, who were lowered into the area by winches from helicopters.[327][328]

On 24 December 2019, the Morrison government announced that volunteer firefighters employed in the Commonwealth public service would be offered at least 20 working days paid leave.[329] On 29 December 2019, it announced that volunteer firefighters who have been called out for more than 10 days would be able to receive financial compensation.[330] On 4 January 2020, it announced that it would lease four waterbombing planes including two long-range DC-10s and two medium-range for use by state and territory governments.[331]

On 5 January 2020, the Prime Minister announced the establishment of the National Bushfire Recovery Agency, funded initially with A$2 billion, under the control of former Australian Federal Police Commissioner, Andrew Colvin.[332][333]

On 5 December 2019, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) commenced Operation Bushfire Assist to support state fire services in logistics, planning, capability, and operational support. Activities the ADF has undertaken as part of the Operation have included Air Force aircraft transporting firefighters and their equipment interstate, Army and Navy helicopters transporting firefighters, conducting night fire mapping, impact assessments and search and rescue flights, use of various defence facilities as coordination and information centres and for catering and accommodation for firefighters, liaison between state and federal government services, reloading and refuelling for waterbombing aircraft, deployment of personnel to assess fire damage and severity, and provision of humanitarian supplies.[45]

On 31 December 2019, the Defence Minister announced the ADF would provide assistance to East Gippsland, in particular the isolated high-fire-risk town of Mallacoota, deploying helicopters including a CH-47 Chinook and C-27J Spartan military transport aircraft to be based at RAAF Base East Sale and two naval vessels, HMAS Choules and MV Sycamore, with the vessels also able to assist in south-east New South Wales if required.[45][334][335] On 1 January 2020, the ADF deployed additional military staff establishing the Victorian Joint Task Force 646 (Army Reserve 4th Brigade) and the following day the New South Wales Joint Task Force 1110 (Army Reserve 5th Brigade).[45] On 3 January 2020, HMAS Choules and MV Sycamore evacuated civilians from Mallacoota bound for Westernport.[45]

On 4 January 2020, following a meeting of the National Security Committee, the Morrison government announced a compulsory call-out of Army Reserve brigades to deploy up to 3,000 reserve personnel full-time to assist with in the Operation. Additionally, Defence announced that it would deploy HMAS Adelaide to support other Navy ships in evacuations and relief, as well additional Chinook helicopters and military transport aircraft to RAAF Base East Sale.[336][331] The same day, Chinook helicopters evacuated civilians from Omeo; and Spartan aircraft evacuated civilians from Mallacoota on 5 January.[45]

The response of volunteer organisations and charities was also considerable, with WIRES Wildlife Rescue working to rescue and treat injured wildlife,[337] Rapid Relief Team Australia raising money for victims, providing meals for firefighters and assisting with two bulk water tankers,[338] Team Rubicon Australia providing debris removal and helping with the cleanup of fire affected areas,[339][340] the Animal Welfare League fundraising and assisting injured animals,[341][342] and St John Ambulance Australia and Australian Red Cross providing support at evacuation centres across New South Wales.

On 1 December 2019 WWF-Australia launched the "Towards Two Billion Trees" plan to aid the koala bushfire recovery. It aims to stop excessive tree-clearing, protect the existing trees and forests, and restore native habitat that has been lost. The ten-point plan for the next ten years foresees to grow 1.56 billion new trees and save 780 million trees.[343][344]