El océano Pacífico es la mayor y más profunda de las cinco divisiones oceánicas de la Tierra . Se extiende desde el océano Ártico en el norte hasta el océano Austral (o, según la definición, hasta la Antártida ) en el sur, y está delimitado por los continentes de Asia y Australia en el oeste y las Américas en el este.

Con una superficie de 165.250.000 kilómetros cuadrados (63.800.000 millas cuadradas) (definido como una frontera antártica meridional), esta división más grande del océano mundial y la hidrosfera cubre aproximadamente el 46% de la superficie del agua de la Tierra y aproximadamente el 32% de la superficie total del planeta, más grande que toda su superficie terrestre (148.000.000 km2 ( 57.000.000 millas cuadradas)). [1] Los centros tanto del hemisferio acuático como del hemisferio occidental , así como el polo oceánico de inaccesibilidad , se encuentran en el océano Pacífico. La circulación oceánica (causada por el efecto Coriolis ) lo subdivide [2] en dos volúmenes de agua en gran medida independientes que se encuentran en el ecuador , el océano Pacífico norte y el océano Pacífico sur (o más libremente los mares del sur ). El Océano Pacífico también puede dividirse informalmente por la Línea Internacional de Cambio de Fecha en el Pacífico Oriental y el Pacífico Occidental , lo que permite dividirlo en cuatro cuadrantes, a saber, el Pacífico Noreste frente a las costas de América del Norte , el Pacífico Sudeste frente a América del Sur , el Pacífico Noroeste frente al Lejano Oriente / Asia Pacífico , y el Pacífico Sudoeste alrededor de Oceanía .

La profundidad media del océano Pacífico es de 4.000 metros (13.000 pies). [3] El abismo Challenger en la fosa de las Marianas , ubicado en el noroeste del Pacífico, es el punto más profundo conocido del mundo, alcanzando una profundidad de 10.928 metros (35.853 pies). [4] El Pacífico también contiene el punto más profundo del hemisferio sur , el abismo Horizon en la fosa de Tonga , a 10.823 metros (35.509 pies). [5] El tercer punto más profundo de la Tierra, el abismo Sirena , también se encuentra en la fosa de las Marianas.

El Pacífico occidental tiene muchos mares marginales importantes , incluidos el mar de Filipinas , el mar de China Meridional , el mar de China Oriental , el mar de Japón , el mar de Ojotsk , el mar de Bering , el golfo de Alaska , el mar de Gray , el mar de Tasmania y el mar de Coral .

A principios del siglo XVI , el explorador español Vasco Núñez de Balboa cruzó el istmo de Panamá en 1513 y avistó el gran "Mar del Sur", al que llamó Mar del Sur . Posteriormente, el nombre actual del océano fue acuñado por el explorador portugués Fernando de Magallanes durante la circunnavegación española del mundo en 1521, ya que encontró vientos favorables al llegar al océano. Lo llamó Mar Pacífico , que en portugués significa 'mar pacífico'. [6] [7]

Principales mares grandes: [8]

En los continentes de Asia, Australia y América , más de 25.000 islas, grandes y pequeñas, se alzan sobre la superficie del océano Pacífico. Muchas de ellas eran las cáscaras de antiguos volcanes activos que han permanecido inactivos durante miles de años. Cerca del ecuador, sin grandes áreas de océano azul, hay un grupo de atolones que, con el paso del tiempo, se han formado a partir de montes submarinos como resultado de pequeñas islas de coral ensartadas en un anillo dentro de los alrededores de una laguna central .

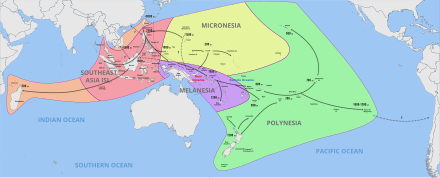

En la prehistoria se produjeron importantes migraciones humanas en el Pacífico. Los humanos modernos llegaron por primera vez al Pacífico occidental en el Paleolítico , hace unos 60.000 a 70.000 años. Procedentes de una migración humana desde África hacia la costa sur, llegaron al este de Asia , al sudeste asiático continental , a las Filipinas, a Nueva Guinea y, después, a Australia, cruzando el mar al menos 80 kilómetros (50 millas) entre Sundaland y Sahul . No se sabe con certeza qué nivel de tecnología marítima utilizaban estos grupos; se supone que utilizaban grandes balsas de bambú que pueden haber estado equipadas con algún tipo de vela. La reducción de los vientos favorables para cruzar a Sahul después de 58.000 AP encaja con la datación del asentamiento de Australia, sin migraciones posteriores en el período prehistórico. Las habilidades marineras de los residentes pre-austronesios del sudeste asiático insular están confirmadas por el asentamiento de Buka hacia el 32.000 AP y de Manus hacia el 25.000 AP. Se trata de viajes de 180 kilómetros (110 millas) y 230 kilómetros (140 millas), respectivamente. [9]

Los descendientes de estas migraciones son hoy los negritos , los melanesios y los aborígenes australianos . Sus poblaciones en el sudeste asiático marítimo , la costa de Nueva Guinea y la Melanesia insular se casaron más tarde con los colonos austronesios que llegaron de Taiwán y el norte de Filipinas , pero también con grupos anteriores asociados con hablantes de austroasiático , lo que dio lugar a los pueblos modernos del sudeste asiático insular y Oceanía. [10] [11]

Una migración marítima posterior es la expansión austronesia neolítica de los pueblos austronesios . Los austronesios se originaron en la isla de Taiwán c. 3000-1500 a. C. Están asociados con tecnologías distintivas de navegación marítima (notablemente barcos con estabilizadores , catamaranes , barcos con amarres y la vela de pinza de cangrejo ); es probable que el desarrollo progresivo de estas tecnologías estuviera relacionado con los pasos posteriores de asentamiento en Oceanía cercana y remota. A partir de alrededor de 2200 a. C., los austronesios navegaron hacia el sur para establecerse en Filipinas . Probablemente, desde el archipiélago de Bismarck cruzaron el Pacífico occidental para llegar a las islas Marianas en 1500 a. C., [12] así como a Palau y Yap en 1000 a. C. Fueron los primeros humanos en llegar a Oceanía remota y los primeros en cruzar grandes distancias de mar abierto. También continuaron expandiéndose hacia el sur y se asentaron en el resto del sudeste asiático marítimo , llegando a Indonesia y Malasia en 1500 a. C., y más al oeste a Madagascar y las Comoras en el océano Índico alrededor de 500 d. C. [13] [14] [15] Más recientemente, se sugiere que los austronesios se expandieron ya antes, llegando a Filipinas ya en 7000 a. C. Se estima que ya en 15000 a. C. se produjeron migraciones anteriores adicionales al sudeste asiático insular, asociadas con hablantes austroasiáticos del sudeste asiático continental. [16]

Entre 1300 y 1200 a. C., una rama de las migraciones austronesias conocida como la cultura Lapita llegó al archipiélago de Bismarck , las islas Salomón , Vanuatu , Fiyi y Nueva Caledonia . Desde allí, se establecieron en Tonga y Samoa entre 900 y 800 a. C. Algunos también regresaron al norte en 200 a. C. para establecerse en las islas del este de Micronesia (incluidas las Carolinas , las islas Marshall y Kiribati ), mezclándose con migraciones austronesias anteriores en la región. Esta siguió siendo la extensión más lejana de la expansión austronesia en Polinesia hasta alrededor de 700 d. C., cuando hubo otra oleada de exploración de islas. Llegaron a las islas Cook , Tahití y las Marquesas en 700 d. C.; Hawái en 900 d. C.; Rapa Nui en 1000 d. C.; y finalmente Nueva Zelanda en 1200 d. C. [14] [17] [18] Los austronesios también podrían haber llegado hasta las Américas , aunque la evidencia de esto no es concluyente. [19] [20]

El primer contacto de los navegantes europeos con el borde occidental del océano Pacífico se produjo con las expediciones portuguesas de António de Abreu y Francisco Serrão , vía las islas Menores de la Sonda , hasta las islas Molucas , en 1512, [21] [22] y con la expedición de Jorge Álvares al sur de China en 1513, [23] ambas ordenadas por Afonso de Albuquerque desde Malaca .

El lado oriental del océano fue encontrado por el explorador español Vasco Núñez de Balboa en 1513 después de que su expedición cruzó el istmo de Panamá y llegó a un nuevo océano. [24] Lo llamó Mar del Sur ("Mar del Sur" o "Mar del Sur" ) porque el océano estaba al sur de la costa del istmo donde observó por primera vez el Pacífico.

En 1520, el navegante Fernando de Magallanes y su tripulación fueron los primeros en cruzar el Pacífico de la historia registrada. Formaban parte de una expedición española a las Islas de las Especias que finalmente daría como resultado la primera circunnavegación del mundo . Magallanes llamó al océano Pacífico (o "Pacífico" que significa, "pacífico") porque, después de navegar por los mares tempestuosos del Cabo de Hornos , la expedición encontró aguas tranquilas. El océano a menudo se llamó Mar de Magallanes en su honor hasta el siglo XVIII. [25] Magallanes se detuvo en una isla deshabitada del Pacífico antes de detenerse en Guam en marzo de 1521. [26] Aunque el propio Magallanes murió en Filipinas en 1521, el navegante español Juan Sebastián Elcano dirigió los restos de la expedición de regreso a España a través del Océano Índico y alrededor del Cabo de Buena Esperanza , completando la primera circunnavegación mundial en 1522. [27] Navegando alrededor y al este de las Molucas, entre 1525 y 1527, las expediciones portuguesas se encontraron con las Islas Carolinas , [28] las Islas Aru , [29] y Papúa Nueva Guinea . [30] En 1542-43, los portugueses también llegaron a Japón. [31]

En 1564, cinco barcos españoles que transportaban 379 soldados cruzaron el océano desde México liderados por Miguel López de Legazpi , y colonizaron las Filipinas y las islas Marianas . [32] Durante el resto del siglo XVI, España mantuvo el control militar y mercantil, con barcos navegando desde México y Perú a través del océano Pacífico hasta las Filipinas vía Guam , y estableciendo las Indias Orientales Españolas . Los galeones de Manila operaron durante dos siglos y medio, uniendo Manila y Acapulco , en una de las rutas comerciales más largas de la historia. Las expediciones españolas también llegaron a Tuvalu , las Marquesas , las Islas Cook , las Islas Salomón , Vanuatu , las Islas Marshall y las Islas del Almirantazgo en el Pacífico Sur. [33]

Más tarde, en la búsqueda de Terra Australis ("la [gran] Tierra del Sur"), las exploraciones españolas en el siglo XVII, como la expedición liderada por el navegante portugués Pedro Fernandes de Queirós , llegaron a los archipiélagos de Pitcairn y Vanuatu , y navegaron por el estrecho de Torres entre Australia y Nueva Guinea, llamado así por el navegante Luís Vaz de Torres . Los exploradores holandeses, navegando alrededor del sur de África, también se dedicaron a la exploración y el comercio; Willem Janszoon , hizo el primer desembarco europeo completamente documentado en Australia (1606), en la península del Cabo York , [34] y Abel Janszoon Tasman circunnavegó y desembarcó en partes de la costa continental australiana y llegó a Tasmania y Nueva Zelanda en 1642. [35]

En los siglos XVI y XVII, España consideraba al océano Pacífico un mare clausum , es decir, un mar cerrado a otras potencias navales. Como única entrada conocida desde el Atlántico, el estrecho de Magallanes era patrullado en ocasiones por flotas enviadas para impedir la entrada de barcos no españoles. En el lado occidental del océano Pacífico, los holandeses amenazaban a las Filipinas españolas . [36]

El siglo XVIII marcó el comienzo de importantes exploraciones por parte de los rusos en Alaska y las islas Aleutianas , como la Primera expedición a Kamchatka y la Gran Expedición del Norte , liderada por el oficial de la marina rusa nacido en Dinamarca Vitus Bering . España también envió expediciones al noroeste del Pacífico , llegando a la isla de Vancouver en el sur de Canadá y Alaska. Los franceses exploraron y colonizaron Polinesia , y los británicos hicieron tres viajes con James Cook al Pacífico Sur y Australia, Hawái y el noroeste del Pacífico norteamericano . En 1768, Pierre-Antoine Véron , un joven astrónomo que acompañó a Louis Antoine de Bougainville en su viaje de exploración, estableció el ancho del Pacífico con precisión por primera vez en la historia. [37] Uno de los primeros viajes de exploración científica fue organizado por España en la Expedición Malaspina de 1789-1794. Navegó por vastas zonas del Pacífico, desde el Cabo de Hornos hasta Alaska, Guam y Filipinas, Nueva Zelanda, Australia y el Pacífico Sur. [33]

_over_the_Marianas_Trench,_23_January_1960_(NH_96797).jpg/440px-Bathyscaphe_Trieste_with_USS_Lewis_(DE-535)_over_the_Marianas_Trench,_23_January_1960_(NH_96797).jpg)

El creciente imperialismo durante el siglo XIX dio lugar a la ocupación de gran parte de Oceanía por parte de las potencias europeas y, más tarde, de Japón y Estados Unidos. Los viajes del HMS Beagle en la década de 1830, con Charles Darwin a bordo; [39] el HMS Challenger durante la década de 1870; [40] el USS Tuscarora (1873-1876); [41] y el alemán Gazelle (1874-1876) hicieron importantes contribuciones al conocimiento oceanográfico. [42]

En Oceanía, Francia obtuvo una posición de liderazgo como potencia imperial después de convertir a Tahití y Nueva Caledonia en protectorados en 1842 y 1853, respectivamente. [43] Después de las visitas de la marina a la Isla de Pascua en 1875 y 1887, el oficial de la marina chilena Policarpo Toro negoció la incorporación de la isla a Chile con los nativos rapanui en 1888. Al ocupar la Isla de Pascua, Chile se unió a las naciones imperiales. [44] : 53 Para 1900, casi todas las islas del Pacífico estaban bajo el control de Gran Bretaña, Francia, Estados Unidos, Alemania, Japón y Chile. [43]

Aunque Estados Unidos obtuvo el control de Guam y Filipinas de España en 1898, [45] Japón controlaba la mayor parte del Pacífico occidental en 1914 y ocupó muchas otras islas durante la Guerra del Pacífico ; sin embargo, al final de esa guerra, Japón fue derrotado y la Flota del Pacífico de los EE. UU. era el dueño virtual del océano. Las Islas Marianas del Norte gobernadas por Japón quedaron bajo el control de los Estados Unidos. [46] Desde el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, muchas antiguas colonias en el Pacífico se han convertido en estados independientes .

El Pacífico separa Asia y Australia de las Américas. Puede subdividirse a su vez por el ecuador en partes septentrional (Pacífico Norte) y meridional (Pacífico Sur). Se extiende desde la región antártica en el sur hasta el Ártico en el norte. [1] El océano Pacífico abarca aproximadamente un tercio de la superficie de la Tierra, con una superficie de 165.200.000 km2 ( 63.800.000 millas cuadradas), más grande que toda la masa continental de la Tierra en conjunto, 150.000.000 km2 ( 58.000.000 millas cuadradas). [47]

El Pacífico, que se extiende aproximadamente 15 500 km (9600 mi) desde el mar de Bering en el Ártico hasta el extremo norte del océano Austral circumpolar a 60°S (las definiciones más antiguas lo extienden hasta el mar de Ross en la Antártida ), alcanza su mayor ancho de este a oeste en aproximadamente 5°N de latitud , donde se extiende aproximadamente 19 800 km (12 300 mi) desde Indonesia hasta la costa de Colombia , la mitad del mundo y más de cinco veces el diámetro de la Luna. [48] Su centro geográfico está en el este de Kiribati al sur de Kiritimati , justo al oeste de la isla Starbuck a 4°58′S 158°45′O / 4.97, -158.75 . [49] El punto más bajo conocido de la Tierra –la Fosa de las Marianas– se encuentra a 10.911 m (35.797 pies ; 5.966 brazas ) por debajo del nivel del mar. Su profundidad media es de 4.280 m (14.040 pies; 2.340 brazas), lo que sitúa el volumen total de agua en aproximadamente 710.000.000 km3 ( 170.000.000 mi3). [1]

Debido a los efectos de la tectónica de placas , el océano Pacífico se está reduciendo actualmente a un ritmo de aproximadamente 2,5 cm (1 pulgada) por año en tres lados, con un promedio de aproximadamente 0,52 km2 ( 0,20 millas cuadradas) por año. En cambio, el océano Atlántico está aumentando de tamaño. [50] [51]

A lo largo de los márgenes occidentales irregulares del océano Pacífico se encuentran muchos mares, los más grandes de los cuales son el mar de Célebes , el mar de Coral , el mar de China Oriental (Mar del Este), el mar de Filipinas , el mar de Japón , el mar de China Meridional (Mar del Sur), el mar de Sulu , el mar de Tasmania y el mar Amarillo (Mar Occidental de Corea). La vía marítima de Indonesia (que incluye el estrecho de Malaca y el estrecho de Torres ) une el Pacífico y el océano Índico al oeste, y el paso de Drake y el estrecho de Magallanes unen el Pacífico con el océano Atlántico al este. Al norte, el estrecho de Bering conecta el Pacífico con el océano Ártico . [52]

Como el Pacífico se extiende a lo largo del meridiano 180 , el Pacífico occidental (o Pacífico occidental , cerca de Asia) está en el hemisferio oriental , mientras que el Pacífico oriental (o Pacífico oriental , cerca de las Américas) está en el hemisferio occidental . [53]

El Océano Pacífico Sur alberga la Dorsal Índica Sudoriental que cruza desde el sur de Australia y se convierte en la Dorsal Pacífico-Antártica (al norte del Polo Sur ) y se fusiona con otra dorsal (al sur de Sudamérica) para formar la Dorsal del Pacífico Oriental que también se conecta con otra dorsal (al sur de Norteamérica) que domina la Dorsal de Juan de Fuca .

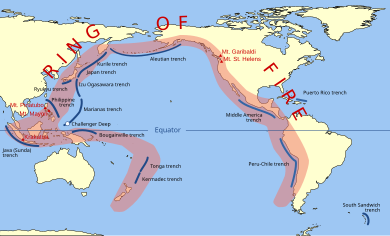

Durante la mayor parte de su viaje desde el estrecho de Magallanes hasta las Filipinas , el explorador encontró un océano en paz; sin embargo, el Pacífico no siempre es pacífico. Muchas tormentas tropicales azotan las islas del Pacífico. [54] Las tierras que rodean la costa del Pacífico están llenas de volcanes y a menudo se ven afectadas por terremotos . [55] Los tsunamis , causados por terremotos submarinos, han devastado muchas islas y en algunos casos han destruido ciudades enteras. [56]

El mapa de Martin Waldseemüller de 1507 fue el primero en mostrar las Américas separando dos océanos distintos. [57] Más tarde, el mapa de Diogo Ribeiro de 1529 fue el primero en mostrar el Pacífico aproximadamente en su tamaño adecuado. [58]

(Los territorios dependientes habitados se indican con un asterisco (*), con los nombres de los estados soberanos correspondientes entre paréntesis. Los estados asociados en el Reino de Nueva Zelanda se indican con el signo almohadilla (#).)

Territorios sin población civil permanente.

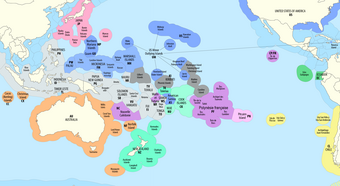

El océano Pacífico alberga la mayor parte de las islas del mundo. Hay alrededor de 25.000 islas en el océano Pacífico. [59] [60] [61] Las islas que se encuentran completamente dentro del océano Pacífico se pueden dividir en tres grupos principales conocidos como Micronesia , Melanesia y Polinesia . Micronesia, que se encuentra al norte del ecuador y al oeste de la línea internacional de cambio de fecha , incluye las islas Marianas en el noroeste, las islas Carolinas en el centro, las islas Marshall al este y las islas de Kiribati en el sureste. [62] [63]

Melanesia, to the southwest, includes New Guinea, the world's second largest island after Greenland and by far the largest of the Pacific islands. The other main Melanesian groups from north to south are the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, Fiji and New Caledonia.[64]

The largest area, Polynesia, stretching from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south, also encompasses Tuvalu, Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga and the Kermadec Islands to the west, the Cook Islands, Society Islands and Austral Islands in the center, and the Marquesas Islands, Tuamotu, Mangareva Islands, and Easter Island to the east.[65]

Islands in the Pacific Ocean are of four basic types: continental islands, high islands, coral reefs and uplifted coral platforms. Continental islands lie outside the andesite line and include New Guinea, the islands of New Zealand, and the Philippines. Some of these islands are structurally associated with nearby continents. High islands are of volcanic origin, and many contain active volcanoes. Among these are Bougainville, Hawaii, and the Solomon Islands.[66]

The coral reefs of the South Pacific are low-lying structures that have built up on basaltic lava flows under the ocean's surface. One of the most dramatic is the Great Barrier Reef off northeastern Australia with chains of reef patches. A second island type formed of coral is the uplifted coral platform, which is usually slightly larger than the low coral islands. Examples include Banaba (formerly Ocean Island) and Makatea in the Tuamotu group of French Polynesia.[67][68]

The volume of the Pacific Ocean, representing about 50.1 percent of the world's oceanic water, has been estimated at some 714 million cubic kilometers (171 million cubic miles).[69] Surface water temperatures in the Pacific can vary from −1.4 °C (29.5 °F), the freezing point of seawater, in the poleward areas to about 30 °C (86 °F) near the equator.[70] Salinity also varies latitudinally, reaching a maximum of 37 parts per thousand in the southeastern area. The water near the equator, which can have a salinity as low as 34 parts per thousand, is less salty than that found in the mid-latitudes because of abundant equatorial precipitation throughout the year. The lowest counts of less than 32 parts per thousand are found in the far north as less evaporation of seawater takes place in these frigid areas.[71] The motion of Pacific waters is generally clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere (the North Pacific gyre) and counter-clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. The North Equatorial Current, driven westward along latitude 15°N by the trade winds, turns north near the Philippines to become the warm Japan or Kuroshio Current.[72]

Turning eastward at about 45°N, the Kuroshio forks and some water moves northward as the Aleutian Current, while the rest turns southward to rejoin the North Equatorial Current.[73] The Aleutian Current branches as it approaches North America and forms the base of a counter-clockwise circulation in the Bering Sea. Its southern arm becomes the chilled slow, south-flowing California Current.[74] The South Equatorial Current, flowing west along the equator, swings southward east of New Guinea, turns east at about 50°S, and joins the main westerly circulation of the South Pacific, which includes the Earth-circling Antarctic Circumpolar Current. As it approaches the Chilean coast, the South Equatorial Current divides; one branch flows around Cape Horn and the other turns north to form the Peru or Humboldt Current.[75]

_peak_intensity.jpg/440px-Typhoon_Tip_(1979)_peak_intensity.jpg)

The climate patterns of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres generally mirror each other. The trade winds in the southern and eastern Pacific are remarkably steady while conditions in the North Pacific are far more varied with, for example, cold winter temperatures on the east coast of Russia contrasting with the milder weather off British Columbia during the winter months due to the preferred flow of ocean currents.[76]

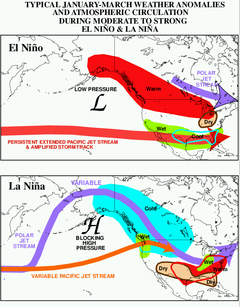

In the tropical and subtropical Pacific, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) affects weather conditions. To determine the phase of ENSO, the most recent three-month sea surface temperature average for the area approximately 3,000 km (1,900 mi) to the southeast of Hawaii is computed, and if the region is more than 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) above or below normal for that period, then an El Niño or La Niña is considered in progress.[77]

In the tropical western Pacific, the monsoon and the related wet season during the summer months contrast with dry winds in the winter which blow over the ocean from the Asian landmass.[78] Worldwide, tropical cyclone activity peaks in late summer, when the difference between temperatures aloft and sea surface temperatures is the greatest; however, each particular basin has its own seasonal patterns. On a worldwide scale, May is the least active month, while September is the most active month. November is the only month in which all the tropical cyclone basins are active.[79] The Pacific hosts the two most active tropical cyclone basins, which are the northwestern Pacific and the eastern Pacific. Pacific hurricanes form south of Mexico, sometimes striking the western Mexican coast and occasionally the Southwestern United States between June and October, while typhoons forming in the northwestern Pacific moving into southeast and east Asia from May to December. Tropical cyclones also form in the South Pacific basin, where they occasionally impact island nations.[80]

In the arctic, icing from October to May can present a hazard for shipping while persistent fog occurs from June to December.[81] A climatological low in the Gulf of Alaska keeps the southern coast wet and mild during the winter months. The Westerlies and associated jet stream within the Mid-Latitudes can be particularly strong, especially in the Southern Hemisphere, due to the temperature difference between the tropics and Antarctica,[82] which records the coldest temperature readings on the planet. In the Southern hemisphere, because of the stormy and cloudy conditions associated with extratropical cyclones riding the jet stream, it is usual to refer to the Westerlies as the Roaring Forties, Furious Fifties and Shrieking Sixties according to the varying degrees of latitude.[83]

The ocean was first mapped by Abraham Ortelius; he called it Maris Pacifici following Ferdinand Magellan's description of it as "a pacific sea" during his circumnavigation from 1519 to 1522. To Magellan, it seemed much more calm (pacific) than the Atlantic.[84]

The andesite line is the most significant regional distinction in the Pacific. A petrologic boundary, it separates the deeper, mafic igneous rock of the Central Pacific Basin from the partially submerged continental areas of felsic igneous rock on its margins.[85] The andesite line follows the western edge of the islands off California and passes south of the Aleutian arc, along the eastern edge of the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Kuril Islands, Japan, the Mariana Islands, the Solomon Islands, and New Zealand's North Island.[86][87]

The dissimilarity continues northeastward along the western edge of the Andes Cordillera along South America to Mexico, returning then to the islands off California. Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, New Guinea, and New Zealand lie outside the andesite line.

Within the closed loop of the andesite line are most of the deep troughs, submerged volcanic mountains, and oceanic volcanic islands that characterize the Pacific basin. Here basaltic lavas gently flow out of rifts to build huge dome-shaped volcanic mountains whose eroded summits form island arcs, chains, and clusters. Outside the andesite line, volcanism is of the explosive type, and the Pacific Ring of Fire is the world's foremost belt of explosive volcanism.[62] The Ring of Fire is named after the several hundred active volcanoes that sit above the various subduction zones.

The Pacific Ocean is the only ocean which is mostly bounded by subduction zones. Only the central part of the North American coast and the Antarctic and Australian coasts have no nearby subduction zones.

The Pacific Ocean was born 750 million years ago at the breakup of Rodinia, although it is generally called the Panthalassa until the breakup of Pangea, about 200 million years ago.[88] The oldest Pacific Ocean floor is only around 180 Ma old, with older crust subducted by now.[89]

The Pacific Ocean contains several long seamount chains, formed by hotspot volcanism. These include the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain and the Louisville Ridge.

The exploitation of the Pacific's mineral wealth is hampered by the ocean's great depths. In shallow waters of the continental shelves off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, petroleum and natural gas are extracted, and pearls are harvested along the coasts of Australia, Japan, Papua New Guinea, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Philippines, although in sharply declining volume in some cases.[90]

Fish are an important economic asset in the Pacific. The shallower shoreline waters of the continents and the more temperate islands yield herring, salmon, sardines, snapper, swordfish, and tuna, as well as shellfish.[91] Overfishing has become a serious problem in some areas. Overfishing leads to depleted fish populations and closed fisheries, causing both economic and ecologic consequences.[92] For example, catches in the rich fishing grounds of the Okhotsk Sea off the Russian coast have been reduced by at least half since the 1990s as a result of overfishing.[93]

The Northwestern Pacific Ocean is most susceptible to micro plastic pollution due to its proximity to highly populated countries like Japan and China.[95] The quantity of small plastic fragments floating in the north-east Pacific Ocean increased a hundredfold between 1972 and 2012.[96] The ever-growing Great Pacific garbage patch between California and Japan is three times the size of France.[97] An estimated 80,000 metric tons of plastic inhabit the patch, totaling 1.8 trillion pieces.[98]

Marine pollution is a generic term for the harmful entry into the ocean of chemicals or particles. The main culprits are those using the rivers for disposing of their waste.[99] The rivers then empty into the ocean, often also bringing chemicals used as fertilizers in agriculture. The excess of oxygen-depleting chemicals in the water leads to hypoxia and the creation of a dead zone.[100]

Marine debris, also known as marine litter, is human-created waste that has ended up floating in a lake, sea, ocean, or waterway. Oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the center of gyres and coastlines, frequently washing aground where it is known as beach litter.[99]

In addition, the Pacific Ocean has served as the crash site of satellites, including Mars 96, Fobos-Grunt, and Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite.

From 1946 to 1958, Marshall Islands served as the Pacific Proving Grounds, designated by the United States, and played host to a total of 67 nuclear tests conducted across various atolls.[102][103] Several nuclear weapons were lost in the Pacific Ocean,[104] including one-megaton bomb that was lost during the 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 incident.[105]

In 2021, the discharge of radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean over a course of 30 years was approved by the Japanese Cabinet. The Cabinet concluded the radioactive water would have been diluted to drinkable standard.[106] Apart from dumping, leakage of tritium into the Pacific was estimated to be between 20 and 40 trillion Bqs from 2011 to 2013, according to the Fukushima plant.[107]

An emerging threat for the Pacific ocean is the development of deep-sea mining. Deep-sea mining is aimed at extracting manganese nodules that contain minerals such as magnesium, nickel, copper, zinc and cobalt. The largest deposits of these are found in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone.[108]

Deep-sea mining for manganese nodules appears to have drastic consequences for the ocean. It disrupts deep-sea ecosystems and may cause irreversible damage to fragile marine habitats.[109] Sediment stirring and chemical pollution threaten various marine animals. In addition, the mining process can lead to greenhouse gas emissions and promote further climate change. Preventing deep-sea mining is therefore important to ensure the long-term health of the ocean.[citation needed]

Scientific researchers have proposed delimiting the boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by two different natural boundaries, by the Shackleton Fracture Zone[110] and by the Scotia Arc[111][112][113] the former being more current than the latter.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)