Un volcán es una ruptura en la corteza de un objeto de masa planetaria , como la Tierra , que permite que la lava caliente , la ceniza volcánica y los gases escapen de una cámara de magma debajo de la superficie. El proceso que forma los volcanes se llama vulcanismo .

En la Tierra, los volcanes se encuentran con mayor frecuencia donde las placas tectónicas divergen o convergen , y debido a que la mayoría de los límites de placas de la Tierra están bajo el agua, la mayoría de los volcanes se encuentran bajo el agua. Por ejemplo, una dorsal oceánica , como la dorsal mesoatlántica , tiene volcanes causados por placas tectónicas divergentes, mientras que el Anillo de Fuego del Pacífico tiene volcanes causados por placas tectónicas convergentes. Los volcanes también pueden formarse donde hay estiramiento y adelgazamiento de las placas de la corteza, como en el Rift de África Oriental , el campo volcánico Wells Gray-Clearwater y el rift del Río Grande en América del Norte. Se ha postulado que el vulcanismo alejado de los límites de placas surge de diapiros ascendentes del límite núcleo-manto , a 3000 kilómetros (1900 mi) de profundidad dentro de la Tierra. Esto da como resultado el vulcanismo de punto caliente , del cual el punto caliente hawaiano es un ejemplo. Los volcanes generalmente no se crean donde dos placas tectónicas se deslizan una sobre otra.

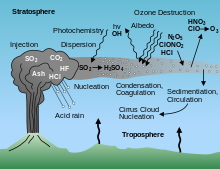

Las grandes erupciones pueden afectar la temperatura atmosférica, ya que las cenizas y las gotitas de ácido sulfúrico oscurecen el Sol y enfrían la troposfera terrestre . Históricamente, las grandes erupciones volcánicas han sido seguidas por inviernos volcánicos que han causado hambrunas catastróficas. [1]

Además de la Tierra, otros planetas tienen volcanes. Por ejemplo, en Venus hay muchos volcanes. [2] En 2009 se publicó un artículo que sugería una nueva definición de la palabra «volcán» que incluye procesos como el criovulcanismo . Sugería que un volcán se definiera como «una abertura en la superficie de un planeta o luna de la que sale magma , tal como se define para ese cuerpo, y/o gas magmático». [3]

Este artículo trata principalmente sobre los volcanes de la Tierra. Para obtener más información, consulte el apartado Volcanes en otros cuerpos celestes y Criovolcán .

La palabra volcán se deriva del nombre de Vulcano , una isla volcánica en las Islas Eolias de Italia cuyo nombre a su vez proviene de Vulcano , el dios del fuego en la mitología romana . [4] El estudio de los volcanes se llama vulcanología , a veces escrito vulcanología . [5]

Según la teoría de la tectónica de placas, la litosfera de la Tierra , su capa exterior rígida, está dividida en dieciséis placas más grandes y varias más pequeñas. Estas se mueven en cámara lenta, debido a la convección en el manto dúctil subyacente , y la mayor parte de la actividad volcánica en la Tierra tiene lugar a lo largo de los límites de las placas, donde las placas convergen (y se destruye la litosfera) o divergen (y se crea una nueva litosfera). [6]

Durante el desarrollo de la teoría geológica se han desarrollado ciertos conceptos que permitieron agrupar a los volcanes en tiempo, lugar, estructura y composición y que finalmente han tenido que ser explicados en la teoría de la tectónica de placas. Por ejemplo, algunos volcanes son poligénicos con más de un período de actividad durante su historia; otros volcanes que se extinguen después de entrar en erupción exactamente una vez son monogénicos (es decir, “de una sola vida”) y tales volcanes a menudo se agrupan en una región geográfica. [7]

En las dorsales oceánicas , dos placas tectónicas divergen entre sí a medida que la roca caliente del manto se desliza hacia arriba debajo de la corteza oceánica adelgazada . La disminución de la presión en la roca ascendente del manto conduce a la expansión adiabática y la fusión parcial de la roca, lo que causa vulcanismo y crea nueva corteza oceánica. La mayoría de los límites de las placas divergentes se encuentran en el fondo de los océanos, por lo que la mayor parte de la actividad volcánica en la Tierra es submarina, formando un nuevo fondo marino . Las fumarolas negras (también conocidas como respiraderos de aguas profundas) son evidencia de este tipo de actividad volcánica. Donde la dorsal oceánica está por encima del nivel del mar, se forman islas volcánicas, como Islandia . [8]

Las zonas de subducción son lugares donde dos placas, generalmente una oceánica y una continental, chocan. La placa oceánica se subduce (se sumerge debajo de la placa continental), formando una fosa oceánica profunda justo en la costa. En un proceso llamado fusión por flujo , el agua liberada de la placa en subducción reduce la temperatura de fusión de la cuña del manto suprayacente, creando así magma . Este magma tiende a ser extremadamente viscoso debido a su alto contenido de sílice , por lo que a menudo no llega a la superficie sino que se enfría y se solidifica en profundidad . Sin embargo, cuando llega a la superficie, se forma un volcán. Por lo tanto, las zonas de subducción están bordeadas por cadenas de volcanes llamados arcos volcánicos . Ejemplos típicos son los volcanes del Cinturón de Fuego del Pacífico , como los volcanes de las Cascadas o el archipiélago japonés , o las islas orientales de Indonesia . [9]

Los puntos calientes son áreas volcánicas que se cree que están formadas por penachos del manto , que se supone que son columnas de material caliente que se elevan desde el límite entre el núcleo y el manto. Al igual que con las dorsales oceánicas, la roca del manto ascendente experimenta una fusión por descompresión que genera grandes volúmenes de magma. Debido a que las placas tectónicas se mueven a través de los penachos del manto, cada volcán se vuelve inactivo a medida que se aleja del penacho, y se crean nuevos volcanes donde la placa avanza sobre el penacho. Se cree que las islas hawaianas se formaron de esa manera, al igual que la llanura del río Snake , y que la caldera de Yellowstone es parte de la placa norteamericana actualmente sobre el punto caliente de Yellowstone . [10] Sin embargo, la hipótesis del penacho del manto ha sido cuestionada. [11]

El afloramiento sostenido de roca del manto caliente puede desarrollarse bajo el interior de un continente y dar lugar a un rifting. Las primeras etapas del rifting se caracterizan por basaltos de inundación y pueden progresar hasta el punto en que una placa tectónica se divide por completo. [12] [13] Luego se desarrolla un límite de placa divergente entre las dos mitades de la placa dividida. Sin embargo, el rifting a menudo no logra dividir por completo la litosfera continental (como en un aulacógeno ), y los rifts fallidos se caracterizan por volcanes que hacen erupción de lava alcalina o carbonatitas inusuales . Los ejemplos incluyen los volcanes del Rift de África Oriental . [14]

Un volcán necesita un depósito de magma fundido (por ejemplo, una cámara de magma), un conducto que permita que el magma suba a través de la corteza y un respiradero que permita que el magma escape por encima de la superficie en forma de lava. [15] El material volcánico erupcionado (lava y tefra) que se deposita alrededor del respiradero se conoce comoedificio volcánico , típicamente un cono o montaña volcánica.[15]

La percepción más común de un volcán es la de una montaña cónica , que arroja lava y gases venenosos desde un cráter en su cima; sin embargo, esto describe solo uno de los muchos tipos de volcanes. Las características de los volcanes son variadas. La estructura y el comportamiento de los volcanes dependen de varios factores. Algunos volcanes tienen picos escarpados formados por domos de lava en lugar de un cráter en la cima, mientras que otros tienen características paisajísticas como mesetas masivas . Los respiraderos que emiten material volcánico (incluyendo lava y ceniza ) y gases (principalmente vapor y gases magmáticos) pueden desarrollarse en cualquier parte del relieve y pueden dar lugar a conos más pequeños como Puʻu ʻŌʻō en un flanco de Kīlauea en Hawái. Los cráteres volcánicos no siempre están en la cima de una montaña o colina y pueden estar llenos de lagos, como el lago Taupō en Nueva Zelanda. Algunos volcanes pueden ser accidentes geográficos de bajo relieve, con el potencial de ser difíciles de reconocer como tales y quedar ocultos por procesos geológicos.

Otros tipos de volcanes incluyen los criovolcanes (o volcanes de hielo), particularmente en algunas lunas de Júpiter , Saturno y Neptuno ; y los volcanes de lodo , que son estructuras que a menudo no están asociadas con una actividad magmática conocida. Los volcanes de lodo activos tienden a tener temperaturas mucho más bajas que las de los volcanes ígneos , excepto cuando el volcán de lodo es en realidad un respiradero de un volcán ígneo.

Los respiraderos de fisuras volcánicas son fracturas planas y lineales a través de las cuales emerge la lava .

Los volcanes en escudo, llamados así por sus amplios perfiles en forma de escudo, se forman por la erupción de lava de baja viscosidad que puede fluir a gran distancia desde un respiradero. Por lo general, no explotan de manera catastrófica, sino que se caracterizan por erupciones efusivas relativamente suaves . Dado que el magma de baja viscosidad suele tener un bajo contenido de sílice, los volcanes en escudo son más comunes en entornos oceánicos que continentales. La cadena volcánica hawaiana es una serie de conos en escudo y también son comunes en Islandia .

Los domos de lava se forman por erupciones lentas de lava altamente viscosa. A veces se forman dentro del cráter de una erupción volcánica anterior, como en el caso del Monte Santa Helena , pero también pueden formarse de forma independiente, como en el caso del Pico Lassen . Al igual que los estratovolcanes, pueden producir erupciones violentas y explosivas, pero la lava generalmente no fluye lejos del respiradero de origen.

Los criptodomos se forman cuando la lava viscosa es empujada hacia arriba, lo que hace que la superficie se abulte. La erupción del Monte Santa Helena en 1980 fue un ejemplo: la lava debajo de la superficie de la montaña creó un abultamiento ascendente que luego se derrumbó por el lado norte de la montaña.

Los conos de ceniza son el resultado de erupciones de pequeños trozos de escoria y piroclásticos (ambos se parecen a las cenizas, de ahí el nombre de este tipo de volcán) que se acumulan alrededor del respiradero. Estas pueden ser erupciones de vida relativamente corta que producen una colina en forma de cono de quizás 30 a 400 metros (100 a 1,300 pies) de altura. La mayoría de los conos de ceniza entran en erupción solo una vez y algunos pueden encontrarse en campos volcánicos monogenéticos que pueden incluir otras características que se forman cuando el magma entra en contacto con el agua, como cráteres de explosión de maar y anillos de toba . [16] Los conos de ceniza pueden formarse como respiraderos de flanco en volcanes más grandes, o ocurrir por sí solos. Parícutin en México y Sunset Crater en Arizona son ejemplos de conos de ceniza. En Nuevo México , Caja del Río es un campo volcánico de más de 60 conos de ceniza.

Basándose en imágenes satelitales, se ha sugerido que los conos de ceniza también podrían aparecer en otros cuerpos terrestres del Sistema Solar; en la superficie de Marte y la Luna. [17] [18] [19] [20]

Los estratovolcanes (volcanes compuestos) son altas montañas cónicas formadas por flujos de lava y tefra en capas alternas, los estratos que dan origen al nombre. También se conocen como volcanes compuestos porque se crean a partir de múltiples estructuras durante diferentes tipos de erupciones. Ejemplos clásicos incluyen el monte Fuji en Japón, el volcán Mayon en Filipinas y el monte Vesubio y el Stromboli en Italia.

Las cenizas producidas por la erupción explosiva de los estratovolcanes han supuesto históricamente el mayor peligro volcánico para las civilizaciones. Las lavas de los estratovolcanes tienen un mayor contenido de sílice y, por lo tanto, son mucho más viscosas que las lavas de los volcanes escudo. Las lavas con alto contenido de sílice también tienden a contener más gas disuelto. La combinación es mortal, ya que promueve erupciones explosivas que producen grandes cantidades de ceniza, así como oleadas piroclásticas como la que destruyó la ciudad de Saint-Pierre en Martinica en 1902. También son más empinadas que los volcanes escudo, con pendientes de 30 a 35° en comparación con las pendientes de 5 a 10° generalmente, y su tefra suelta es material para lahares peligrosos . [21] Los grandes trozos de tefra se denominan bombas volcánicas . Las bombas grandes pueden medir más de 1,2 metros (4 pies) de ancho y pesar varias toneladas. [22]

Un supervolcán se define como un volcán que ha experimentado una o más erupciones que produjeron más de 1000 kilómetros cúbicos (240 millas cúbicas) de depósitos volcánicos en un solo evento explosivo. [23] Tales erupciones ocurren cuando una cámara de magma muy grande llena de magma silícico rico en gas se vacía en una erupción catastrófica que forma una caldera . Las tobas de flujo de cenizas emplazadas por tales erupciones son el único producto volcánico con volúmenes que rivalizan con los de los basaltos de inundación . [24]

Las erupciones de supervolcanes, aunque son el tipo más peligroso, son muy poco frecuentes: se conocen cuatro en el último millón de años y se han identificado alrededor de 60 erupciones históricas de VEI 8 en el registro geológico a lo largo de millones de años. Un supervolcán puede producir devastación a escala continental y enfriar gravemente las temperaturas globales durante muchos años después de la erupción debido a los enormes volúmenes de azufre y ceniza liberados a la atmósfera.

Debido a la enorme área que cubren y su posterior ocultamiento bajo la vegetación y los depósitos glaciares, los supervolcanes pueden ser difíciles de identificar en el registro geológico sin un mapeo geológico cuidadoso . [25] Los ejemplos conocidos incluyen la Caldera de Yellowstone en el Parque Nacional de Yellowstone y la Caldera de Valles en Nuevo México (ambos en el oeste de los Estados Unidos); el lago Taupō en Nueva Zelanda; el lago Toba en Sumatra , Indonesia; y el cráter de Ngorongoro en Tanzania.

Los volcanes que, aunque son grandes, no son lo suficientemente grandes como para ser llamados supervolcanes, también pueden formar calderas de la misma manera; a menudo se los describe como "volcanes de caldera". [26]

Los volcanes submarinos son características comunes del fondo del océano. La actividad volcánica durante la época del Holoceno se ha documentado en solo 119 volcanes submarinos, pero puede haber más de un millón de volcanes submarinos geológicamente jóvenes en el fondo del océano. [27] [28] En aguas poco profundas, los volcanes activos revelan su presencia al expulsar vapor y escombros rocosos muy por encima de la superficie del océano. En las cuencas oceánicas profundas, el tremendo peso del agua impide la liberación explosiva de vapor y gases; sin embargo, las erupciones submarinas pueden detectarse mediante hidrófonos y por la decoloración del agua debido a los gases volcánicos . La lava almohadillada es un producto eruptivo común de los volcanes submarinos y se caracteriza por gruesas secuencias de masas discontinuas en forma de almohada que se forman bajo el agua. Incluso las grandes erupciones submarinas pueden no perturbar la superficie del océano, debido al rápido efecto de enfriamiento y al aumento de la flotabilidad en el agua (en comparación con el aire), lo que a menudo hace que los respiraderos volcánicos formen pilares empinados en el fondo del océano. Los respiraderos hidrotermales son comunes cerca de estos volcanes y algunos sustentan ecosistemas peculiares basados en quimiótrofos que se alimentan de minerales disueltos. Con el tiempo, las formaciones creadas por los volcanes submarinos pueden llegar a ser tan grandes que rompen la superficie del océano como nuevas islas o balsas flotantes de piedra pómez .

En mayo y junio de 2018, las agencias de monitoreo de terremotos de todo el mundo detectaron una multitud de señales sísmicas . Adoptaron la forma de zumbidos inusuales, y algunas de las señales detectadas en noviembre de ese año tuvieron una duración de hasta 20 minutos. Una campaña de investigación oceanográfica en mayo de 2019 mostró que los zumbidos hasta entonces misteriosos fueron causados por la formación de un volcán submarino frente a la costa de Mayotte . [29]

Los volcanes subglaciales se desarrollan debajo de los casquetes polares . Están formados por mesetas de lava que cubren extensas lavas almohadilladas y palagonita . Estos volcanes también se denominan montañas de mesa, tuyas [ 30] o (en Islandia) mobergs. [31] Se pueden ver muy buenos ejemplos de este tipo de volcán en Islandia y en Columbia Británica . El origen del término proviene de Tuya Butte , que es una de las varias tuyas en el área del río Tuya y la cordillera Tuya en el norte de Columbia Británica. Tuya Butte fue la primera forma de relieve de este tipo analizada y, por lo tanto, su nombre ha entrado en la literatura geológica para este tipo de formación volcánica. [32] El Parque Provincial de las Montañas Tuya se estableció recientemente para proteger este paisaje inusual, que se encuentra al norte del lago Tuya y al sur del río Jennings, cerca del límite con el Territorio del Yukón .

Los volcanes de lodo (domos de lodo) son formaciones creadas por líquidos y gases excretados por el suelo, aunque varios procesos pueden causar dicha actividad. [33] Las estructuras más grandes tienen 10 kilómetros de diámetro y alcanzan los 700 metros de altura. [34]

.jpg/440px-Aerial_image_of_Stromboli_(view_from_the_northeast).jpg)

El material que se expulsa en una erupción volcánica se puede clasificar en tres tipos:

Las concentraciones de diferentes gases volcánicos pueden variar considerablemente de un volcán a otro. El vapor de agua es típicamente el gas volcánico más abundante, seguido por el dióxido de carbono [38] y el dióxido de azufre . Otros gases volcánicos principales incluyen sulfuro de hidrógeno , cloruro de hidrógeno y fluoruro de hidrógeno . También se encuentra una gran cantidad de gases menores y traza en las emisiones volcánicas, por ejemplo , hidrógeno , monóxido de carbono , halocarbonos , compuestos orgánicos y cloruros metálicos volátiles .

La forma y el estilo de la erupción de un volcán están determinados en gran medida por la composición de la lava que expulsa. La viscosidad (la fluidez de la lava) y la cantidad de gas disuelto son las características más importantes del magma, y ambas están determinadas en gran medida por la cantidad de sílice presente en el magma. El magma rico en sílice es mucho más viscoso que el magma pobre en sílice, y el magma rico en sílice también tiende a contener más gases disueltos.

La lava se puede clasificar en cuatro composiciones diferentes: [39]

Los flujos de lava máfica muestran dos variedades de textura superficial: ʻAʻa (pronunciado [ˈʔaʔa] ) y pāhoehoe ( [paːˈho.eˈho.e] ), ambas palabras hawaianas . ʻAʻa se caracteriza por una superficie áspera y viscosa y es la textura típica de los flujos de lava basáltica más fríos. Pāhoehoe se caracteriza por su superficie lisa y a menudo fibrosa o arrugada y generalmente se forma a partir de flujos de lava más fluidos. A veces se observa que los flujos de Pāhoehoe pasan a flujos ʻaʻa a medida que se alejan del respiradero, pero nunca a la inversa. [53]

Los flujos de lava más silícicos toman la forma de lava en bloques, donde el flujo está cubierto de bloques angulares pobres en vesículas. Los flujos riolíticos generalmente consisten principalmente en obsidiana . [54]

La tefra se forma cuando el magma dentro del volcán es destrozado por la rápida expansión de los gases volcánicos calientes. El magma suele explotar cuando el gas disuelto en él sale de la solución a medida que la presión disminuye cuando fluye hacia la superficie . Estas explosiones violentas producen partículas de material que pueden volar desde el volcán. Las partículas sólidas de menos de 2 mm de diámetro ( del tamaño de la arena o más pequeñas) se denominan ceniza volcánica. [36] [37]

La tefra y otros volcaniclásticos (material volcánico fragmentado) constituyen una parte mayor del volumen de muchos volcanes que los flujos de lava. Los volcaniclásticos pueden haber contribuido hasta con un tercio de toda la sedimentación en el registro geológico. La producción de grandes volúmenes de tefra es característica del vulcanismo explosivo. [55]

A través de procesos naturales, principalmente la erosión , gran parte del material solidificado que forma el manto de un volcán puede ser eliminado y su anatomía interna se vuelve evidente. Usando la metáfora de la anatomía biológica , este proceso se llama "disección". [56] Cinder Hill , una característica del Monte Bird en la Isla Ross , Antártida , es un ejemplo destacado de un volcán diseccionado. Los volcanes que, en una escala de tiempo geológica, estuvieron activos recientemente, como por ejemplo el Monte Kaimon en el sur de Kyūshū , Japón , tienden a no estar diseccionados.

Los estilos de erupción se dividen en general en erupciones magmáticas, freatomagmáticas y freáticas. [57] La intensidad del vulcanismo explosivo se expresa utilizando el Índice de Explosividad Volcánica (VEI), que varía de 0 para erupciones de tipo hawaiano a 8 para erupciones supervolcánicas. [58]

A diciembre de 2022 [actualizar], la base de datos del Programa de Vulcanismo Global del Instituto Smithsoniano sobre erupciones volcánicas en la época del Holoceno (los últimos 11.700 años) enumera 9.901 erupciones confirmadas de 859 volcanes. La base de datos también enumera 1.113 erupciones inciertas y 168 erupciones desacreditadas para el mismo intervalo de tiempo. [59] [60]

Los volcanes varían mucho en su nivel de actividad, y cada sistema volcánico tiene una recurrencia de erupción que va desde varias veces al año hasta una vez cada decenas de miles de años. [61] Los volcanes se describen informalmente como en erupción , activos , inactivos o extintos , pero las definiciones de estos términos no son completamente uniformes entre los vulcanólogos. El nivel de actividad de la mayoría de los volcanes cae dentro de un espectro graduado, con mucha superposición entre categorías, y no siempre encaja perfectamente en una sola de estas tres categorías separadas. [62]

El USGS define que un volcán está "en erupción" siempre que la expulsión de magma desde cualquier punto del volcán sea visible, incluido el magma visible aún contenido dentro de las paredes del cráter de la cumbre.

Si bien no existe un consenso internacional entre los vulcanólogos sobre cómo definir un volcán activo, el USGS define un volcán como activo siempre que estén presentes indicadores subterráneos, como enjambres de terremotos , inflación del suelo o niveles inusualmente altos de dióxido de carbono o dióxido de azufre. [63] [64]

El Servicio Geológico de los Estados Unidos define un volcán inactivo como cualquier volcán que no muestra signos de actividad, como enjambres de terremotos, crecidas del terreno o emisiones excesivas de gases nocivos, pero que muestra signos de que podría volver a activarse. [64] Muchos volcanes inactivos no han entrado en erupción durante miles de años, pero aún han mostrado signos de que es probable que vuelvan a entrar en erupción en el futuro. [65] [66]

En un artículo que justifica la reclasificación del volcán Mount Edgecumbe de Alaska de "inactivo" a "activo", los vulcanólogos del Observatorio de Volcanes de Alaska señalaron que el término "inactivo" en referencia a los volcanes ha quedado obsoleto en las últimas décadas y que "[e]l término "volcán inactivo" se utiliza tan poco y está tan indefinido en la vulcanología moderna que la Enciclopedia de Volcanes (2000) no lo contiene en los glosarios ni en el índice", [67] sin embargo el USGS todavía emplea ampliamente el término.

Anteriormente, se consideraba que un volcán estaba extinto si no había registros escritos de su actividad. Tal generalización es incompatible con la observación y un estudio más profundo, como ocurrió recientemente con la erupción inesperada del volcán Chaitén en 2008. [68] Las técnicas modernas de monitoreo de la actividad volcánica y las mejoras en el modelado de los factores que producen erupciones han ayudado a comprender por qué los volcanes pueden permanecer inactivos durante mucho tiempo y luego volverse inesperadamente activos. El potencial de erupciones y su estilo dependen principalmente del estado del sistema de almacenamiento de magma debajo del volcán, el mecanismo desencadenante de la erupción y su escala de tiempo. [69] : 95 Por ejemplo, el volcán de Yellowstone tiene un período de reposo/recarga de alrededor de 700.000 años, y el Toba de alrededor de 380.000 años. [70] Los escritores romanos describieron el Vesubio como cubierto de jardines y viñedos antes de su inesperada erupción del año 79 d. C. , que destruyó las ciudades de Herculano y Pompeya .

En consecuencia, a veces puede ser difícil distinguir entre un volcán extinto y uno inactivo. Se sabe que la inactividad prolongada de un volcán disminuye la conciencia. [69] : 96 Pinatubo era un volcán discreto, desconocido para la mayoría de las personas en las áreas circundantes, e inicialmente no monitoreado sísmicamente antes de su erupción inesperada y catastrófica de 1991. Otros dos ejemplos de volcanes que alguna vez se creyeron extintos, antes de volver a la actividad eruptiva fueron el volcán Soufrière Hills, inactivo durante mucho tiempo , en la isla de Montserrat , que se pensó extinto hasta que la actividad se reanudó en 1995 (convirtiendo su capital Plymouth en una ciudad fantasma ) y Fourpeaked Mountain en Alaska, que, antes de su erupción de septiembre de 2006, no había entrado en erupción desde antes de 8000 a. C.

Los volcanes extintos son aquellos que los científicos consideran poco probable que vuelvan a entrar en erupción porque el volcán ya no tiene un suministro de magma. Ejemplos de volcanes extintos son muchos volcanes en la cadena de montes submarinos Hawái-Emperador en el océano Pacífico (aunque algunos volcanes en el extremo oriental de la cadena están activos), Hohentwiel en Alemania , Shiprock en Nuevo México , EE. UU. , Capulin en Nuevo México, EE. UU., El volcán Zuidwal en los Países Bajos y muchos volcanes en Italia como Monte Vulture . El Castillo de Edimburgo en Escocia está ubicado sobre un volcán extinto, que forma Castle Rock . A menudo es difícil determinar si un volcán está realmente extinto. Dado que las calderas de "supervolcanes" pueden tener una vida útil eruptiva a veces medida en millones de años, una caldera que no ha producido una erupción en decenas de miles de años puede considerarse inactiva en lugar de extinta. Un volcán individual en un campo volcánico monogénico puede estar extinto, pero eso no significa que un volcán completamente nuevo no pueda entrar en erupción cerca con poca o ninguna advertencia, ya que su campo puede tener un suministro de magma activo.

Las tres clasificaciones populares más comunes de los volcanes pueden ser subjetivas y algunos volcanes que se creían extintos han vuelto a entrar en erupción. Para ayudar a evitar que las personas crean erróneamente que no corren riesgo al vivir en un volcán o cerca de él, los países han adoptado nuevas clasificaciones para describir los distintos niveles y etapas de la actividad volcánica. [71] Algunos sistemas de alerta utilizan diferentes números o colores para designar las diferentes etapas. Otros sistemas utilizan colores y palabras. Algunos sistemas utilizan una combinación de ambos.

Los Volcanes del Decenio son 16 volcanes identificados por la Asociación Internacional de Vulcanología y Química del Interior de la Tierra (IAVCEI) como dignos de estudio particular a la luz de su historial de erupciones grandes y destructivas y su proximidad a áreas pobladas. Se los llama Volcanes del Decenio porque el proyecto se inició como parte del Decenio Internacional para la Reducción de los Desastres Naturales (década de 1990) patrocinado por las Naciones Unidas. Los 16 volcanes del Decenio actuales son:

El Proyecto de Desgasificación de Carbono de la Tierra Profunda , una iniciativa del Observatorio de Carbono Profundo , monitorea nueve volcanes, dos de los cuales son volcanes de la Década. El objetivo del Proyecto de Desgasificación de Carbono de la Tierra Profunda es utilizar instrumentos del Sistema Analizador de Gas Multicomponente para medir las proporciones de CO2 / SO2 en tiempo real y en alta resolución para permitir la detección de la desgasificación preeruptiva de magmas ascendentes, mejorando la predicción de la actividad volcánica . [72]

Las erupciones volcánicas suponen una amenaza importante para la civilización humana. Sin embargo, la actividad volcánica también ha proporcionado a los seres humanos importantes recursos.

Existen muchos tipos diferentes de erupciones volcánicas y actividades asociadas: erupciones freáticas (erupciones generadas por vapor), erupciones explosivas de lava con alto contenido de sílice (por ejemplo, riolita ), erupciones efusivas de lava con bajo contenido de sílice (por ejemplo, basalto ), derrumbes de sectores , flujos piroclásticos , lahares (flujos de escombros) y emisiones de gases volcánicos . Estos pueden representar un peligro para los humanos. Los terremotos, las fuentes termales , las fumarolas , los pozos de lodo y los géiseres a menudo acompañan a la actividad volcánica.

Los gases volcánicos pueden alcanzar la estratosfera, donde forman aerosoles de ácido sulfúrico que pueden reflejar la radiación solar y reducir significativamente las temperaturas de la superficie. [73] El dióxido de azufre de la erupción de Huaynaputina puede haber causado la hambruna rusa de 1601-1603 . [74] Las reacciones químicas de los aerosoles de sulfato en la estratosfera también pueden dañar la capa de ozono , y ácidos como el cloruro de hidrógeno (HCl) y el fluoruro de hidrógeno (HF) pueden caer al suelo como lluvia ácida . Las sales de fluoruro excesivas de las erupciones han envenenado al ganado en Islandia en múltiples ocasiones. [75] : 39–58 Las erupciones volcánicas explosivas liberan el gas de efecto invernadero dióxido de carbono y, por lo tanto, proporcionan una fuente profunda de carbono para los ciclos biogeoquímicos . [76]

Las cenizas que se lanzan al aire durante las erupciones pueden representar un peligro para las aeronaves, especialmente para los aviones a reacción , cuyas partículas pueden fundirse debido a la alta temperatura de funcionamiento; las partículas fundidas se adhieren a las aspas de la turbina y alteran su forma, alterando el funcionamiento de la misma, lo que puede causar importantes trastornos en los viajes aéreos.

Se cree que hace unos 70.000 años se produjo un invierno volcánico tras la supererupción del lago Toba en la isla de Sumatra, en Indonesia. [77] Esto puede haber creado un cuello de botella poblacional que afectó a la herencia genética de todos los seres humanos actuales. [78] Las erupciones volcánicas pueden haber contribuido a importantes eventos de extinción, como las extinciones masivas del Ordovícico final , el Pérmico-Triásico y el Devónico tardío . [79]

La erupción del monte Tambora en 1815 creó anomalías climáticas globales que se conocieron como el " año sin verano " debido a su efecto sobre el clima de América del Norte y Europa. [80] El gélido invierno de 1740-1741, que provocó una hambruna generalizada en el norte de Europa, también puede tener su origen en una erupción volcánica. [81]

Aunque las erupciones volcánicas plantean peligros considerables para los seres humanos, la actividad volcánica del pasado ha creado importantes recursos económicos. La toba formada a partir de cenizas volcánicas es una roca relativamente blanda y se ha utilizado para la construcción desde la antigüedad. [82] [83] Los romanos solían utilizar toba, que es abundante en Italia, para la construcción. [84] El pueblo Rapa Nui utilizó toba para hacer la mayoría de las estatuas moai de la Isla de Pascua . [85]

Las cenizas volcánicas y el basalto erosionado producen uno de los suelos más fértiles del mundo, rico en nutrientes como hierro, magnesio, potasio, calcio y fósforo. [86] La actividad volcánica es responsable de la ubicación de valiosos recursos minerales, como minerales metálicos. [86] Va acompañada de altas tasas de flujo de calor desde el interior de la Tierra. Estos pueden aprovecharse como energía geotérmica . [86]

El turismo asociado a los volcanes también es una industria mundial. [87]

Muchos volcanes cercanos a asentamientos humanos son monitoreados intensamente con el objetivo de proporcionar advertencias anticipadas adecuadas de erupciones inminentes a las poblaciones cercanas. Además, una mejor comprensión moderna de la vulcanología ha llevado a algunas respuestas gubernamentales y públicas mejor informadas a actividades volcánicas imprevistas. Si bien la ciencia de la vulcanología puede no ser capaz todavía de predecir las horas y fechas exactas de las erupciones en el futuro lejano, en volcanes adecuadamente monitoreados el monitoreo de indicadores volcánicos en curso a menudo es capaz de predecir erupciones inminentes con advertencias anticipadas de al menos horas, y generalmente de días antes de cualquier erupción. [88] La diversidad de volcanes y sus complejidades significan que los pronósticos de erupciones para el futuro previsible se basarán en la probabilidad y la aplicación de la gestión de riesgos . Incluso entonces, algunas erupciones no tendrán una advertencia útil. Un ejemplo de esto ocurrió en marzo de 2017, cuando un grupo de turistas estaba presenciando una erupción previsible del Monte Etna y la lava que fluía entró en contacto con una acumulación de nieve, lo que provocó una explosión freática situacional que causó heridas a diez personas. [87] Se sabe que otros tipos de erupciones significativas dan advertencias útiles de solo horas como máximo mediante el monitoreo sísmico. [68] La reciente demostración de una cámara de magma con tiempos de reposo de decenas de miles de años, con potencial de recarga rápida, lo que potencialmente reduce los tiempos de advertencia, debajo del volcán más joven de Europa central, [69] no nos dice si un monitoreo más cuidadoso será útil.

Se sabe que los científicos perciben el riesgo, con sus elementos sociales, de manera diferente a las poblaciones locales y a quienes realizan evaluaciones de riesgo social en su nombre, de modo que, cuando ocurren desastres, seguirán produciéndose falsas alarmas disruptivas y culpas retrospectivas. [89] : 1–3

Así, en muchos casos, si bien las erupciones volcánicas aún pueden causar importantes destrozos materiales, la pérdida periódica de vidas humanas a gran escala que antes se asociaba a muchas erupciones volcánicas se ha reducido significativamente en las zonas donde los volcanes se controlan adecuadamente. Esta capacidad para salvar vidas se deriva de estos programas de monitoreo de la actividad volcánica, de la mayor capacidad de los funcionarios locales para facilitar evacuaciones oportunas basadas en el mayor conocimiento moderno del vulcanismo que ahora está disponible y de las tecnologías de comunicación mejoradas, como los teléfonos celulares. Estas operaciones tienden a proporcionar tiempo suficiente para que los humanos escapen al menos con vida antes de una erupción inminente. Un ejemplo de una evacuación volcánica exitosa reciente fue la evacuación del Monte Pinatubo de 1991. Se cree que esta evacuación salvó 20.000 vidas. [90] En el caso del Monte Etna , una revisión de 2021 encontró 77 muertes debido a erupciones desde 1536, pero ninguna desde 1987. [87]

Los ciudadanos que puedan estar preocupados por su propia exposición al riesgo de la actividad volcánica cercana deberían familiarizarse con los tipos y la calidad de los procedimientos de vigilancia de volcanes y notificación pública que emplean las autoridades gubernamentales en sus zonas. [91]

La Luna de la Tierra no tiene grandes volcanes ni actividad volcánica actual, aunque evidencias recientes sugieren que aún puede poseer un núcleo parcialmente fundido. [92] Sin embargo, la Luna tiene muchas características volcánicas como mares [93] (las manchas más oscuras que se ven en la Luna), grietas [94] y domos . [95]

El planeta Venus tiene una superficie compuesta en un 90% por basalto , lo que indica que el vulcanismo jugó un papel importante en la conformación de su superficie. El planeta puede haber tenido un importante evento de resurgimiento global hace unos 500 millones de años, [96] por lo que los científicos pueden deducir de la densidad de cráteres de impacto en la superficie. Los flujos de lava están muy extendidos y también se producen formas de vulcanismo que no están presentes en la Tierra. Los cambios en la atmósfera del planeta y las observaciones de relámpagos se han atribuido a las erupciones volcánicas en curso, aunque no hay confirmación de si Venus sigue siendo volcánicamente activo o no. Sin embargo, el sondeo de radar de la sonda Magallanes reveló evidencia de actividad volcánica comparativamente reciente en el volcán más alto de Venus, Maat Mons , en forma de flujos de ceniza cerca de la cumbre y en el flanco norte. [97] Sin embargo, la interpretación de los flujos como flujos de ceniza ha sido cuestionada. [98]

Hay varios volcanes extintos en Marte , cuatro de los cuales son enormes volcanes en escudo mucho más grandes que cualquiera de los de la Tierra. Entre ellos se encuentran el monte Arsia , el monte Ascraeus , el monte Hecates Tholus , el monte Olympus y el monte Pavonis . Estos volcanes llevan extintos muchos millones de años, [99] pero la sonda espacial europea Mars Express ha encontrado pruebas de que también puede haber habido actividad volcánica en Marte en el pasado reciente. [99]

La luna de Júpiter, Ío, es el objeto volcánicamente más activo del Sistema Solar debido a la interacción de las mareas con Júpiter. Está cubierta de volcanes que expulsan azufre , dióxido de azufre y rocas de silicato , y como resultado, Ío está constantemente renovando su superficie. Sus lavas son las más calientes conocidas en cualquier parte del Sistema Solar, con temperaturas que superan los 1.800 K (1.500 °C). En febrero de 2001, las mayores erupciones volcánicas registradas en el Sistema Solar ocurrieron en Ío. [100] Europa , la más pequeña de las lunas galileanas de Júpiter , también parece tener un sistema volcánico activo, excepto que su actividad volcánica es completamente en forma de agua, que se congela en hielo en la superficie gélida. Este proceso se conoce como criovulcanismo , y aparentemente es más común en las lunas de los planetas exteriores del Sistema Solar . [101]

En 1989, la sonda espacial Voyager 2 observó criovolcanes (volcanes de hielo) en Tritón , una luna de Neptuno , y en 2005 la sonda Cassini-Huygens fotografió fuentes de partículas congeladas que brotaban de Encélado , una luna de Saturno . [102] [103] La eyección puede estar compuesta de agua, nitrógeno líquido , amoníaco , polvo o compuestos de metano . Cassini-Huygens también encontró evidencia de un criovolcán que arroja metano en la luna de Saturno Titán , que se cree que es una fuente importante del metano que se encuentra en su atmósfera. [104] Se teoriza que el criovulcanismo también puede estar presente en el objeto del cinturón de Kuiper Quaoar .

Un estudio de 2010 del exoplaneta COROT-7b , que fue detectado por tránsito en 2009, sugirió que el calentamiento por marea de la estrella anfitriona muy cercana al planeta y los planetas vecinos podría generar una intensa actividad volcánica similar a la encontrada en Ío. [105]

Los volcanes no se distribuyen uniformemente sobre la superficie de la Tierra, pero los activos con un impacto significativo se encontraron temprano en la historia humana, evidenciado por huellas de homínidos encontradas en cenizas volcánicas de África Oriental que datan de 3,66 millones de años. [106] : 104 La asociación de los volcanes con el fuego y el desastre se encuentra en muchas tradiciones orales y tenía significado religioso y, por lo tanto, social antes del primer registro escrito de conceptos relacionados con los volcanes. Algunos ejemplos son: (1) las historias en las subculturas atabascas sobre humanos que viven dentro de las montañas y una mujer que usa el fuego para escapar de una montaña, [107] : 135 (2) la migración de Pele a través de la cadena de islas Hawarian, la capacidad de destruir bosques y las manifestaciones del temperamento del dios, [108] y (3) la asociación en el folclore javanés de un rey residente en el volcán Monte Merapi y una reina residente en una playa a 50 km (31 mi) de distancia en lo que ahora se sabe que es una falla sísmica que interactúa con ese volcán. [109]

Muchos relatos antiguos atribuyen las erupciones volcánicas a causas sobrenaturales , como las acciones de dioses o semidioses . El ejemplo más antiguo conocido es una diosa neolítica en Çatalhöyük . [110] : 203 El antiguo dios griego Hefesto y los conceptos del inframundo están relacionados con los volcanes en esa cultura griega. [87]

Sin embargo, otros propusieron causas más naturales (pero aún incorrectas) de la actividad volcánica. En el siglo V a. C., Anaxágoras propuso que las erupciones eran causadas por un fuerte viento. [111] Hacia el 65 d. C., Séneca el Joven propuso la combustión como causa, [111] una idea también adoptada por el jesuita Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), quien presenció las erupciones del Monte Etna y Stromboli , luego visitó el cráter del Vesubio y publicó su visión de una Tierra en Mundus Subterraneus con un fuego central conectado a muchos otros que representan a los volcanes como un tipo de válvula de seguridad. [112] Edward Jorden, en su trabajo sobre aguas minerales, desafió esta visión; en 1632 propuso la "fermentación" del azufre como una fuente de calor dentro de la Tierra, [111] El astrónomo Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) creía que los volcanes eran conductos para las lágrimas de la Tierra. [113] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] En 1650, René Descartes propuso que el núcleo de la Tierra era incandescente y, en 1785, los trabajos de Descartes y otros fueron sintetizados en geología por James Hutton en sus escritos sobre intrusiones ígneas de magma. [111] Lazzaro Spallanzani había demostrado en 1794 que las explosiones de vapor podían causar erupciones explosivas y muchos geólogos sostuvieron que esto era la causa universal de las erupciones explosivas hasta la erupción del Monte Tarawera en 1886 , que permitió en un evento la diferenciación de las erupciones freatomagmáticas e hidrotermales concurrentes de la erupción explosiva seca, de, como resultó, un dique de basalto . [114] : 16–18 [115] : 4 Alfred Lacroix se basó en sus otros conocimientos con sus estudios sobre la erupción del Monte Pelée en 1902 , [111] y en 1928 el trabajo de Arthur Holmes había reunido los conceptos de generación radiactiva de calor, la estructura del manto de la Tierra , la fusión por descompresión parcial del magma y la convección del magma. [111] Esto eventualmente condujo a la aceptación de la tectónica de placas. [116]