Dromaeosauridae ( / ˌdrɒmiəˈsɔːrɪdiː / ) es una familia de dinosaurios terópodos celurosaurios emplumados . Por lo general , eran carnívoros emplumados de tamaño pequeño a mediano que florecieron en el Período Cretácico. El nombre Dromaeosauridae significa 'lagartos corredores', del griego δρομαῖος ( dromaîos ) , que significa ' correr a toda velocidad ' , 'rápido', y σαῦρος ( saûros ), que significa 'lagarto'. En el uso informal, a menudo se les llama rapaces [6] (en honor a Velociraptor ), un término popularizado por la película Jurassic Park ; Varios géneros incluyen el término "raptor" directamente en su nombre, y la cultura popular ha llegado a enfatizar su apariencia similar a la de las aves y su comportamiento especulativo similar al de las aves.

Se han encontrado fósiles de dromeosáuridos en todo el mundo en América del Norte , Europa , África , Asia y América del Sur , y algunos fósiles dan crédito a la posibilidad de que también habitaran Australia . [7] Los fósiles corporales más antiguos se conocen del Cretácico Inferior (hace 145-140 millones de años), y sobrevivieron hasta el final del Cretácico ( etapa Maastrichtiana , 66 ma), existiendo hasta el evento de extinción masiva del Cretácico-Paleógeno . La presencia de dromeosáuridos ya en el Jurásico Medio ha sido sugerida por el descubrimiento de dientes fósiles aislados, aunque no se han encontrado fósiles corporales de dromeosáuridos de este período. [8] [9]

Los dromeosáuridos se diagnostican por las siguientes características: frontales cortos en forma de T que forman el límite rostral de la fenestra supratemporal ; una plataforma caudolateral que sobresale del escamoso ; un proceso lateral del cuadrado que contacta con el cuadradoyugal ; parapófisis elevadas y pedunculadas en las vértebras dorsales , un dígito pedal II modificado; chevrones y precigapófisis de las vértebras caudales alargados y que abarcan varias vértebras; la presencia de una fosa subglenoidea en el coracoides . [10]

Los dromeosáuridos eran dinosaurios de tamaño pequeño a mediano, que medían entre 1,5 y 2,07 metros (en el caso del Velociraptor ) hasta aproximarse o superar los 6 m (en el caso del Utahraptor , el Dakotaraptor y el Achillobator ). [11] [12] El gran tamaño parece haber evolucionado al menos dos veces entre los dromeosáuridos; una entre los dromeosáuridos Utahraptor y Achillobator , y otra entre los unenlagiinos ( Austroraptor , que medía entre 5 y 6 m (16 y 20 pies) de largo). Un posible tercer linaje de dromeosáuridos gigantes está representado por dientes aislados encontrados en la Isla de Wight , Inglaterra . Los dientes pertenecen a un animal del tamaño del dromeosáurido Utahraptor , pero parecen pertenecer a los velociraptorinos, a juzgar por la forma de los dientes. [13] [14]

El característico plan corporal de los dromeosáuridos ayudó a reavivar las teorías de que los dinosaurios pueden haber sido activos, rápidos y estrechamente relacionados con las aves. La ilustración de Robert Bakker para la monografía de John Ostrom de 1969, [15] que muestra al dromeosáurido Deinonychus en una carrera rápida, es una de las reconstrucciones paleontológicas más influyentes de la historia. [16] El plan corporal de los dromeosáuridos incluye un cráneo relativamente grande, dientes dentados, hocico estrecho (una excepción son los dromeosáuridos derivados ) y ojos orientados hacia adelante que indican cierto grado de visión binocular. [17]

Los dromeosáuridos, como la mayoría de los demás terópodos, tenían un cuello moderadamente largo curvado en forma de S, y su tronco era relativamente corto y profundo. Al igual que otros maniraptores , tenían brazos largos que podían doblarse contra el cuerpo en algunas especies, y manos relativamente grandes con tres dedos largos (el dedo medio era el más largo y el índice el más corto) que terminaban en grandes garras. [10] La estructura de la cadera de los dromeosáuridos presentaba una característica bota púbica grande que sobresalía debajo de la base de la cola. Los pies de los dromeosáuridos tenían una garra grande y curvada en el segundo dedo. Sus colas eran delgadas, con vértebras largas y bajas que carecían de proceso transversal y espinas neurales después de la decimocuarta vértebra caudal. [10] Se han identificado procesos uncinados osificados de las costillas en varios dromeosáuridos. [18] [19] [20]

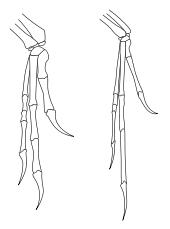

Al igual que otros terópodos, los dromeosáuridos eran bípedos, es decir, caminaban sobre sus patas traseras. Sin embargo, mientras que la mayoría de los terópodos caminaban con tres dedos en contacto con el suelo, las huellas fosilizadas confirman que muchos grupos de paravianos primitivos , incluidos los dromeosáuridos, mantenían el segundo dedo del pie fuera del suelo en una posición hiperextendida, y solo el tercer y cuarto dedos soportaban el peso del animal. Esto se llama didactilia funcional. [21] El segundo dedo agrandado tenía una garra falciforme (con forma de hoz, alt. drepanoidea ) inusualmente grande, curvada (sostenida fuera del suelo o "retraída" al caminar), que se cree que se utilizó para capturar presas y trepar a los árboles (ver "Función de la garra" a continuación). Esta garra era especialmente parecida a una cuchilla en los eudromosaurios depredadores de cuerpo grande . [22] Una posible especie de dromeosáurido, Balaur bondoc , también poseía un primer dedo que estaba muy modificado en paralelo con el segundo. Tanto el primer como el segundo dedo de cada pie de B. bondoc también se mantenían retraídos y tenían garras agrandadas en forma de hoz. [23]

Los dromeosáuridos tenían colas largas. La mayoría de las vértebras de la cola tenían extensiones óseas similares a varillas (llamadas prezigapófisis), así como tendones óseos en algunas especies. En su estudio de Deinonychus , Ostrom propuso que estas características endurecían la cola de modo que solo podía flexionarse en la base, y toda la cola se movería entonces como una única palanca rígida. [15] Sin embargo, un espécimen bien conservado de Velociraptor mongoliensis (IGM 100/986) tiene un esqueleto de cola articulado que se curva horizontalmente en una larga forma de S. Esto sugiere que, en vida, la cola podía doblarse de lado a lado con un grado sustancial de flexibilidad. [24] Se ha propuesto que esta cola se usaba como estabilizador o contrapeso mientras corría o estaba en el aire; [24] en Microraptor , se conserva un abanico de plumas alargado en forma de diamante en el extremo de la cola. Es posible que se haya utilizado como estabilizador aerodinámico y timón durante el planeo o el vuelo propulsado (véase "Vuelo y planeo" a continuación). [25]

Existe una gran cantidad de evidencia que muestra que los dromeosáuridos estaban cubiertos de plumas . Algunos fósiles de dromeosáuridos conservan plumas largas y penáceas en las manos y los brazos ( rémiges ) y la cola ( rectrices ), así como plumas más cortas, similares al plumón, que cubren el cuerpo. [26] [27] Otros fósiles, que no conservan impresiones reales de plumas, aún conservan las protuberancias asociadas en los huesos del antebrazo donde las largas plumas de las alas se habrían adherido en vida. [28] En general, este patrón de plumas se parece mucho al Archaeopteryx . [26]

El primer dromeosáurido conocido con evidencia definitiva de plumas fue Sinornithosaurus , reportado en China por Xu et al. en 1999. [27] Se han encontrado muchos otros fósiles de dromeosáuridos con plumas cubriendo sus cuerpos, algunos con alas emplumadas completamente desarrolladas. Microraptor incluso muestra evidencia de un segundo par de alas en las patas traseras. [26] Si bien las impresiones directas de plumas solo son posibles en sedimentos de grano fino, algunos fósiles encontrados en rocas más gruesas muestran evidencia de plumas por la presencia de protuberancias en las púas, los puntos de unión de las plumas de las alas que poseen algunas aves. Los dromeosáuridos Rahonavis y Velociraptor se han encontrado con protuberancias en las púas, lo que demuestra que estas formas tenían plumas a pesar de que no se han encontrado impresiones. A la luz de esto, es muy probable que incluso los dromeosáuridos terrestres más grandes tuvieran plumas, ya que incluso las aves no voladoras de hoy en día conservan la mayor parte de su plumaje, y se sabe que los dromeosáuridos relativamente grandes, como el Velociraptor , conservaron plumas penáceas. [28] [29] Aunque algunos científicos habían sugerido que los dromeosáuridos más grandes perdieron parte o la totalidad de su cubierta aislante, el descubrimiento de plumas en especímenes de Velociraptor se ha citado como evidencia de que todos los miembros de la familia conservaban plumas. [28] [30]

Más recientemente, el descubrimiento de Zhenyuanlong estableció la presencia de un pelaje lleno de plumas en dromeosáuridos relativamente grandes. Además, el animal muestra plumas en las alas proporcionalmente grandes y aerodinámicas, así como un abanico que se extiende a lo largo de la cola, ambos rasgos inesperados que pueden ofrecer una comprensión del tegumento de los grandes dromeosáuridos. [31] Dakotaraptor es una especie de dromeosáurido aún más grande con evidencia de plumas, aunque indirectamente en forma de protuberancias en las púas, [32] aunque el taxón es considerado como quimera por otros investigadores ya que incluso los elementos dinosaurios con supuestos rasgos diagnósticos para los dromeosáuridos también son atribuibles a los caenagnátidos y ornitomimosaurianos . [33] [34]

Los dromeosáuridos comparten muchas características con las aves primitivas (clado Avialae o Aves ). La naturaleza precisa de su relación con las aves ha sido objeto de un gran estudio, y las hipótesis sobre esa relación han cambiado a medida que se disponía de grandes cantidades de nueva evidencia. Tan tarde como 2001, Mark Norell y colegas analizaron un gran estudio de fósiles de celurosaurios y produjeron el resultado tentativo de que los dromeosáuridos estaban más estrechamente relacionados con las aves, con los troodóntidos como un grupo externo más distante. Incluso sugirieron que los Dromaeosauridae podrían ser parafiléticos en relación con Avialae. [35] En 2002, Hwang y colegas utilizaron el trabajo de Norell et al. , incluyendo nuevos caracteres y mejor evidencia fósil, para determinar que las aves (avialanos) eran mejor consideradas como primos de los dromeosáuridos y los troodóntidos . [11] El consenso de los paleontólogos es que aún no hay suficiente evidencia para determinar si los dromeosáuridos podían volar o planear, o si evolucionaron a partir de ancestros que podían hacerlo. [36]

Los dromeosáuridos son tan parecidos a las aves que han llevado a algunos investigadores a argumentar que sería mejor clasificarlos como aves. En primer lugar, dado que tenían plumas, los dromeosáuridos (junto con muchos otros dinosaurios terópodos celurosaurios) son "pájaros" según las definiciones tradicionales de la palabra "pájaro" o "aves", que se basan en la posesión de plumas. Sin embargo, otros científicos, como Lawrence Witmer , han argumentado que llamar ave a un terópodo como Caudipteryx porque tiene plumas puede extender la palabra más allá de cualquier significado útil. [37]

Al menos dos escuelas de investigadores han propuesto que los dromeosáuridos en realidad pueden descender de ancestros voladores. Las hipótesis que implican un ancestro volador de los dromeosáuridos a veces se denominan "Las aves llegaron primero" (BCF). George Olshevsky suele ser reconocido como el primer autor de BCF. [38] En su propio trabajo, Gregory S. Paul señaló numerosas características del esqueleto de los dromeosáuridos que interpretó como evidencia de que todo el grupo había evolucionado a partir de ancestros voladores, dinosaurios, tal vez un animal como Archaeopteryx . En ese caso, los dromeosáuridos más grandes eran secundariamente no voladores, como el avestruz moderno . [29] En 1988, Paul sugirió que los dromeosáuridos en realidad pueden estar más estrechamente relacionados con las aves modernas que con Archaeopteryx . Sin embargo, en 2002, Paul colocó a los dromeosáuridos y Archaeopteryx como los parientes más cercanos entre sí. [39]

En 2002, Hwang et al. descubrieron que Microraptor era el dromeosáurido más primitivo. [11] En 2003, Xu y sus colegas citaron la posición basal de Microraptor , junto con las características de las plumas y las alas, como evidencia de que el dromeosáurido ancestral podía planear. En ese caso, los dromeosáuridos más grandes serían secundariamente terrestres, habiendo perdido la capacidad de planear más adelante en su historia evolutiva. [26]

También en 2002, Steven Czerkas describió a Cryptovolans , aunque es un probable sinónimo menor de Microraptor . Reconstruyó el fósil de forma imprecisa con solo dos alas y, por lo tanto, argumentó que los dromeosáuridos eran voladores con motor, en lugar de planeadores pasivos. Más tarde publicó una reconstrucción revisada que concordaba con la de Microraptor [40] .

Otros investigadores, como Larry Martin , han propuesto que los dromeosáuridos, junto con todos los maniraptoros, no eran dinosaurios en absoluto. Martin afirmó durante décadas que las aves no estaban relacionadas con los maniraptoros, pero en 2004 cambió su posición, aceptando que los dos eran parientes cercanos. Sin embargo, Martin creía que los maniraptoros eran aves secundariamente no voladoras, y que las aves no evolucionaron de los dinosaurios, sino de arcosaurios no dinosaurios. [41]

En 2005, Mayr y Peters describieron la anatomía de un espécimen muy bien conservado de Archaeopteryx , y determinaron que su anatomía era más parecida a la de los terópodos no aviares de lo que se creía anteriormente. Específicamente, encontraron que Archaeopteryx tenía un palatino primitivo , un hallux no invertido y un segundo dedo hiperextensible. Su análisis filogenético produjo el controvertido resultado de que Confuciusornis estaba más cerca de Microraptor que de Archaeopteryx , lo que convierte a Avialae en un taxón parafilético. También sugirieron que el paraviano ancestral podía volar o planear, y que los dromeosáuridos y troodóntidos eran secundariamente no voladores (o habían perdido la capacidad de planear). [43] [44] Corfe y Butler criticaron este trabajo por motivos metodológicos. [45]

Un desafío a todos estos escenarios alternativos llegó cuando Turner y colegas en 2007 describieron un nuevo dromeosáurido, Mahakala , que encontraron que era el miembro más basal y más primitivo de los Dromaeosauridae, más primitivo que Microraptor . Mahakala tenía brazos cortos y no tenía capacidad para planear. Turner et al. también dedujeron que el vuelo evolucionó solo en Avialae, y estos dos puntos sugirieron que el dromeosáurido ancestral no podía planear ni volar. Con base en este análisis cladístico, Mahakala sugiere que la condición ancestral de los dromeosáuridos es no volar . [46] Sin embargo, en 2012, un estudio ampliado y revisado que incorporaba los hallazgos de dromeosáuridos más recientes recuperó a Xiaotingia , similar a Archaeopteryx , como el miembro más primitivo del clado Dromaeosauridae, lo que parece sugerir que los primeros miembros del clado pueden haber sido capaces de volar. [47]

La autoría de la familia Dromaeosauridae se atribuye a William Diller Matthew y Barnum Brown , quienes la erigieron como una subfamilia (Dromaeosaurinae) de la familia Deinodontidae en 1922, conteniendo únicamente al nuevo género Dromaeosaurus . [48]

Las subfamilias de Dromaeosauridae cambian frecuentemente de contenido en función de nuevos análisis, pero por lo general consisten en los siguientes grupos. Una serie de dromeosáuridos no han sido asignados a ninguna subfamilia en particular, a menudo porque están demasiado mal conservados para ser ubicados con confianza en el análisis filogenético (ver la sección Filogenia a continuación) o son indeterminados, siendo asignados a diferentes grupos dependiendo de la metodología empleada en diferentes artículos. La subfamilia más básica conocida de dromeosáuridos es Halszkaraptorinae, un grupo de criaturas extrañas con dedos y cuellos largos, una gran cantidad de dientes pequeños y posibles hábitos semiacuáticos. [49] Otro grupo enigmático, Unenlagiinae, es la subfamilia de dromeosáuridos con menos respaldo y es posible que algunos o todos sus miembros pertenezcan fuera de Dromaeosauridae. [50] [51] Los miembros más grandes que viven en el suelo, como Buitreraptor y Unenlagia, muestran fuertes adaptaciones para el vuelo, aunque probablemente eran demasiado grandes para "despegar". Un posible miembro de este grupo, Rahonavis , es muy pequeño, con alas bien desarrolladas que muestran evidencia de protuberancias en las púas (los puntos de unión de las plumas de vuelo) y es muy probable que pudiera volar. El siguiente clado más primitivo de dromeosáuridos es Microraptoria. Este grupo incluye a muchos de los dromeosáuridos más pequeños, que muestran adaptaciones para vivir en árboles. Todas las impresiones de piel de dromeosáuridos conocidas provienen de este grupo y todas muestran una extensa cobertura de plumas y alas bien desarrolladas. Al igual que los unenlagiines, algunas especies pueden haber sido capaces de volar activamente. El subgrupo más avanzado de dromeosáuridos, Eudromaeosauria, incluye géneros robustos y de patas cortas que probablemente eran cazadores de emboscada. Este grupo incluye a Velociraptorinae, Dromaeosaurinae y, en algunos estudios, a un tercer grupo: Saurornitholestinae. La subfamilia Velociraptorinae ha incluido tradicionalmente a Velociraptor , Deinonychus y Saurornitholestes , y aunque el descubrimiento de Tsaagan respaldó esta agrupación, la inclusión de Deinonychus , Saurornitholestes y algunos otros géneros aún es incierta. Se suele encontrar que Dromaeosaurinae consiste en especies de tamaño mediano a gigante, con cráneos generalmente en forma de caja (las otras subfamilias generalmente tienen hocicos más estrechos). [5]

La siguiente clasificación de los diversos géneros de dromeosáuridos sigue la tabla proporcionada en Holtz, 2011, a menos que se indique lo contrario. [5]

Dromaeosauridae fue definido por primera vez como un clado por Paul Sereno en 1998, como el grupo natural más inclusivo que contiene a Dromaeosaurus pero no a Troodon , Ornithomimus o Passer . Las diversas "subfamilias" también han sido redefinidas como clados, generalmente definidos como todas las especies más cercanas al homónimo del grupo que a Dromaeosaurus o cualquier homónimo de otros subclados (por ejemplo, Makovicky definió el clado Unenlagiinae como todos los dromaeosauridos más cercanos a Unenlagia que a Velociraptor ). Microraptoria es el único subclado de dromaeosauridos que no se convirtió de una subfamilia. Senter y sus colegas acuñaron expresamente el nombre sin el sufijo de subfamilia -inae para evitar problemas percibidos con la erección de un taxón de grupo familiar tradicional , en caso de que se descubriera que el grupo se encontraba fuera de los dromaeosauridae propiamente dichos. [53] Sereno ofreció una definición revisada del subgrupo que contiene a Microraptor para asegurar que caería dentro de Dromaeosauridae, y erigió la subfamilia Microraptorinae, atribuyéndola a Senter et al. , aunque este uso solo ha aparecido en su base de datos en línea TaxonSearch y no ha sido publicado formalmente. [54] El extenso análisis cladístico realizado por Turner et al. (2012) respaldó aún más la monofilia de Dromaeosauridae. [55]

El cladograma a continuación sigue un análisis de 2015 realizado por DePalma et al. utilizando datos actualizados del Theropod Working Group. [32]

Otro cladograma construido a continuación sigue el análisis filogenético realizado en 2017 por Cau et al. utilizando los datos actualizados del Theropod Working Group en su descripción de Halszkaraptor . [49]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of several dromaeosaurids (Microraptor, Sinornithosaurus, and Velociraptor) and modern birds and reptiles indicate that some dromaeosaurids (including Microraptor and Velociraptor) may have been nocturnal predators, while Sinornithosaurus is inferred to be cathemeral (active throughout the day at short intervals).[56] However, the discovery of iridescent plumage in Microraptor has cast doubt on the inference of nocturnality in this genus, as no modern birds that have iridescent plumage are known to be nocturnal.[57]

Studies of the olfactory bulbs of dromaeosaurids reveal that they had similar olfactory ratios for their size to other non-avian theropods and modern birds with an acute sense of smell, such as tyrannosaurids and the turkey vulture, probably reflecting the importance of the olfactory sense in the daily activities of dromaeosaurids such as finding food.[58][59]

Dromaeosaurid feeding was discovered to be typical of coelurosaurian theropods, with a characteristic "puncture and pull" feeding method. Studies of wear patterns on the teeth of dromaeosaurids by Angelica Torices et al. indicate that dromaeosaurid teeth share similar wear patterns to those seen in the Tyrannosauridae and Troodontidae. However, microwear on the teeth indicated that dromaeosaurids likely preferred larger prey items than the troodontids they often shared their environment with. Such dietary differentiations likely allowed them to inhabit the same environment. The same study also indicated that dromaeosaurids such as Dromaeosaurus and Saurornitholestes (two dromaeosaurids analyzed in the study) likely included bone in their diet and were better adapted to handle struggling prey while troodontids, equipped with weaker jaws, preyed on softer animals and prey items such as invertebrates and carrion.[60]

There is currently disagreement about the function of the enlarged "sickle claw" on the second toe. When John Ostrom described it for Deinonychus in 1969, he interpreted the claw as a blade-like slashing weapon, much like the canines of some saber-toothed cats, used with powerful kicks to cut into prey. Adams (1987) suggested that the talon was used to disembowel large ceratopsian dinosaurs.[61] The interpretation of the sickle claw as a killing weapon applied to all dromaeosaurids. However, Manning et al. argued that the claw instead served as a hook, reconstructing the keratinous sheath with an elliptical cross section, instead of the previously inferred inverted teardrop shape.[62] In Manning's interpretation, the second toe claw would be used as a climbing aid when subduing bigger prey and also as a stabbing weapon.

Ostrom compared Deinonychus to the ostrich and cassowary. He noted that the bird species can inflict serious injury with the large claw on the second toe.[15] The cassowary has claws up to 125 millimetres (4.9 in) long.[63] Ostrom cited Gilliard (1958) in saying that they can sever an arm or disembowel a man.[64] Kofron (1999 and 2003) studied 241 documented cassowary attacks and found that one human and two dogs had been killed, but no evidence that cassowaries can disembowel or dismember other animals.[65][66] Cassowaries use their claws to defend themselves, to attack threatening animals, and in agonistic displays such as the Bowed Threat Display.[63] The seriema also has an enlarged second toe claw, and uses it to tear apart small prey items for swallowing.[67]

Phillip Manning and colleagues (2009) attempted to test the function of the sickle claw and similarly shaped claws on the forelimbs. They analyzed the bio-mechanics of how stresses and strains would be distributed along the claws and into the limbs, using X-ray imaging to create a three-dimensional contour map of a forelimb claw from Velociraptor. For comparison, they analyzed the construction of a claw from a modern predatory bird, the eagle owl. They found that, based on the way that stress was conducted along the claw, they were ideal for climbing. The scientists found that the sharpened tip of the claw was a puncturing and gripping instrument, while the curved and expanded claw base helped transfer stress loads evenly. The Manning team also compared the curvature of the dromaeosaurid "sickle claw" on the foot with curvature in modern birds and mammals. Previous studies had shown that the amount of curvature in a claw corresponded to what lifestyle the animal has: animals with strongly curved claws of a certain shape tend to be climbers, while straighter claws indicate ground-dwelling lifestyles. The sickle claws of the dromaeosaurid Deinonychus have a curvature of 160 degrees, well within the range of climbing animals. The forelimb claws they studied also fell within the climbing range of curvature.[68]

Paleontologist Peter Mackovicky commented on the Manning team's study, stating that small, primitive dromaeosaurids (such as Microraptor) were likely to have been tree-climbers, but that climbing did not explain why later, gigantic dromaeosaurids such as Achillobator retained highly curved claws when they were too large to have climbed trees. Mackovicky speculated that giant dromaeosaurids may have adapted the claw to be used exclusively for latching on to prey.[69]

In 2009 Phil Senter published a study on dromaeosaurid toes and showed that their range of motion was compatible with the excavation of tough insect nests. Senter suggested that small dromaeosaurids such as Rahonavis and Buitreraptor were small enough to be partial insectivores, while larger genera such as Deinonychus and Neuquenraptor could have used this ability to catch vertebrate prey residing in insect nests. However, Senter did not test whether the strong curvature of dromaeosaurid claws was also conducive to such activities.[70]

In 2011, Denver Fowler and colleagues suggested a new method by which dromaeosaurids may have taken smaller prey. This model, known as the "raptor prey restraint" (RPR) model of predation, proposes that dromaeosaurids killed their prey in a manner very similar to extant accipitrid birds of prey: by leaping onto their quarry, pinning it under their body weight, and gripping it tightly with the large, sickle-shaped claws. Like accipitrids, the dromaeosaurid would then begin to feed on the animal while still alive, until it eventually died from blood loss and organ failure. This proposal is based primarily on comparisons between the morphology and proportions of the feet and legs of dromaeosaurids to several groups of extant birds of prey with known predatory behaviors. Fowler found that the feet and legs of dromaeosaurids most closely resemble those of eagles and hawks, especially in terms of having an enlarged second claw and a similar range of grasping motion. The short metatarsus and foot strength, however, would have been more similar to that of owls. The RPR method of predation would be consistent with other aspects of dromaeosaurid anatomy, such as their unusual dentition and arm morphology. The arms, which could exert a lot of force but were likely covered in long feathers, may have been used as flapping stabilizers for balance while atop a struggling prey animal, along with the stiff counterbalancing tail. Dromaeosaurid jaws, thought by Fowler and colleagues to be comparatively weak, would have been useful for eating prey alive but not as useful for quick, forceful dispatch of the prey. These predatory adaptations working together may also have implications for the origin of flapping in paravians.[71][72]

In 2019, Peter Bishop reconstructed the leg skeleton and musculature of Deinonychus by using three-dimensional models of muscles, tendons, and bones. With the addition of mathematical models and equations, Bishop simulated the conditions that would provide maximum force at the tip of the sickle claw and therefore the most likely function. Among the proposed modes of the sickle claw use are: kicking to cut, slash or disembowel prey; for gripping onto the flanks of prey; piercing aided by body weight; to attack vital areas of the prey; to restrain prey; intra- or interspecific competition; and digging out prey from hideouts. The results obtained by Bishop showed that a crouching posture increased the claw forces, however, these forces remained relatively weak indicating that the claws were not strong enough to be used in slashing strikes. Rather than being used for slashing, the sickle claws were more likely to be useful in flexed leg angles such as restraining prey and stabbing prey at close quarters. These results are consistent with the Fighting Dinosaurs specimen, which preserves a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in combat, with the former gripping onto the other with its claws in a non-extended leg posture. Despite the obtained results, Bishop considered that the capabilities of the sickle claw could have varied within taxa given that among dromaeosaurids, Adasaurus had an unusually smaller sickle claw that retained the characteristic ginglymoid—a structure divided in two parts—and hyperextensible articular surface of the penultimate phalange. He could neither confirm nor disregard that the pedal digit II could have loss or retain its functionally.[73]

A 2020 study by Gianechini et al., also indicates that velociraptorines, dromaeosaurines and other eudromaeosaurs in Laurasia differed greatly in their locomotive and killing techniques from the unenlagiine dromaeosaurids of Gondwana. The shorter second phalanx in the second digit of the foot allowed for increased force to be generated by that digit, which, combined with a shorter and wider metatarsus, and a noticeable marked hinge‐like morphology of the articular surfaces of metatarsals and phalanges, possibly allowed eudromaeosaurs to exert a greater gripping strength than unenlagiines, allowing for more efficient subduing and killing of large prey. In comparison, the unenlagiine dromaeosaurids had a longer and slender subarctometatarsus, and less well‐marked hinge joints, a trait that possibly gave them greater cursorial capacities and allowed for greater speed. Additionally, the longer second phalanx of the second digit allowed unenlagiines fast movements of their feet's second digits to hunt smaller and more elusive types of prey. These differences in locomotor and predatory specializations may have been a key feature that influenced the evolutionary pathways that shaped both groups of dromaeosaurs in the northern and southern hemispheres.[74]

Deinonychus fossils have been uncovered in small groups near the remains of the herbivore Tenontosaurus, a larger ornithischian dinosaur. This had been interpreted as evidence that these dromaeosaurids hunted in coordinated packs like some modern mammals.[76] However, not all paleontologists found the evidence conclusive, and a subsequent study published in 2007 by Roach and Brinkman suggests that the Deinonychus may have actually displayed a disorganized mobbing behavior. Modern diapsids, including birds and crocodiles (the closest relatives of dromaeosaurids), display minimal long-term cooperative hunting (except the aplomado falcon and Harris's hawk); instead, they are usually solitary hunters, either joining forces time to time to increase hunting success (as crocodilians sometimes do), or are drawn to previously killed carcasses, where conflict often occurs between individuals of the same species. For example, in situations where groups of Komodo dragons are eating together, the largest individuals eat first and might attack smaller Komodo dragons that attempt to feed; if the smaller animal dies, it is usually cannibalized. When this information is applied to the sites containing putative pack-hunting behavior in dromaeosaurids, it appears somewhat consistent with a Komodo dragon-like feeding strategy. Deinonychus skeletal remains found at these sites are from subadults, with missing parts that may have been eaten by other Deinonychus, which a study by Roach et al. presented as evidence against the idea that the animals cooperated in the hunt.[77] Different dietary preferences between juvenile and adult Deinonychus published in 2020 indicate that the animal did not exhibit complex, cooperative behavior seen in pack-hunting animals. Whether this extended to other dromaeosaurs is currently unknown.[78] A third possible option is that dromaeosaurids did not exhibit long-term cooperative behaviour, but did show short-term cooperative behaviour as seen in crocodilians, which display both true cooperation and competition for prey.

In 2001, multiple Utahraptor specimens ranging in age from fully grown adult to tiny three-foot-long baby were found at a site considered by some to be a quicksand predator trap. Some consider this as evidence of family hunting behaviour; however, the full sandstone block is yet to be opened and researchers are unsure as to whether or not the animals died at the same time.[79]

In 2007, scientists described the first known extensive dromaeosaurid trackway, in Shandong, China. In addition to confirming the hypothesis that the sickle claw was held retracted off the ground, the trackway (made by a large, Achillobator-sized species) showed evidence of six individuals of about equal size moving together along a shoreline. The individuals were spaced about one meter apart, traveling in the same direction and walking at a fairly slow pace. The authors of the paper describing these footprints interpreted the trackways as evidence that some species of dromaeosaurids lived in groups. While the trackways clearly do not represent hunting behavior, the idea that groups of dromaeosaurids may have hunted together, according to the authors, could not be ruled out.[21]

The forearms of dromaeosaurids appear well adapted to resisting the torsional and bending stresses associated with flapping and gliding,[80] and the ability to fly or glide has been suggested for at least five dromaeosaurid species. The first, Rahonavis ostromi (originally classified as avian bird, but found to be a dromaeosaurid in later studies[17][81]) may have been capable of powered flight, as indicated by its long forelimbs with evidence of quill knob attachments for long sturdy flight feathers.[82] The forelimbs of Rahonavis were more powerfully built than Archaeopteryx, and show evidence that they bore strong ligament attachments necessary for flapping flight. Luis Chiappe concluded that, given these adaptations, Rahonavis could probably fly but would have been more clumsy in the air than modern birds.[83]

Another species of dromaeosaurid, Microraptor gui, may have been capable of gliding using its well-developed wings on both the fore and hind limbs. A 2005 study by Sankar Chatterjee suggested that the wings of Microraptor functioned like a split-level "biplane", and that it likely employed a phugoid style of gliding, in which it would launch from a perch and swoop downward in a U-shaped curve, then lift again to land on another tree, with the tail and hind wings helping to control its position and speed. Chatterjee also found that Microraptor had the basic requirements to sustain level powered flight in addition to gliding.[25]

Changyuraptor yangi is a close relative of Microraptor gui, also thought to be a glider or flyer based on the presence of four wings and similar limb proportions. However, it is a considerably larger animal, around the size of a wild turkey, being among the largest known flying Mesozoic paravians.

Another dromaeosaurid species, Deinonychus antirrhopus, may display partial flight capacities. The young of this species bore longer arms and more robust pectoral girdles than adults, and which were similar to those seen in other flapping theropods, implying that they may have been capable of flight when young and then lost the ability as they grew.[84]

The possibility that Sinornithosaurus millenii was capable of gliding or even powered flight has also been brought up several times,[85][86] though no further studies have occurred.

Zhenyuanlong preserves wing feathers that are aerodynamically shaped, with particularly bird-like coverts as opposed to the longer, wider-spanning coverts of forms like Archaeopteryx and Anchiornis, as well as fused sternal plates. Due to its size and short arms it is unlikely that Zhenyuanlong was capable of powered flight (though the importance of biomechanical modelling in this regard is stressed[31]), but it may suggest a relatively close descendance from flying ancestors, or even some capacity for gliding or wing-assisted incline running.

In 2001, Bruce Rothschild and others published a study examining evidence for stress fractures and tendon avulsions in theropod dinosaurs and the implications for their behavior. Since stress fractures are caused by repeated trauma rather than singular events they are more likely to be caused by regular behavior than other types of injuries. The researchers found lesions like those caused by stress fractures on a dromaeosaurid hand claw, one of only two such claw lesions discovered in the course of the study. Stress fractures in the hands have special behavioral significance compared to those found in the feet, since stress fractures in the feet can be obtained while running or during migration. Hand injuries, by contrast, are more likely to be obtained while in contact with struggling prey.[87]

At least one dromaeosaurid group, Halszkaraptorinae, whose members are halszkaraptorines, are most likely to have been specialised for aquatic or semiaquatic habits, having developed limb proportions, tooth morphology, and rib cage akin to those of diving birds.[49][88][89]

Fishing habits have been proposed for unenlagiines, including comparisons to attributed semi-aquatic spinosaurids,[90] but any aquatic propulsion mechanisms have not been discussed so far.

In 2006, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky reported an egg associated with a specimen of Deinonychus. The egg shares similarities with oviraptorid eggs, and the authors interpreted the association as potentially indicative of brooding.[91] A study published in November 2018 by Norell, Yang and Wiemann et al., indicates that Deinonychus laid blue eggs, likely to camouflage them as well as creating open nests. Other dromaeosaurids may have done the same, and it is theorized that they and other maniraptoran dinosaurs may have been an origin point for laying colored eggs and creating open nests as many birds do today.[92][93][94]

Velociraptor, a dromaeosaurid, gained much attention after it was featured prominently in the 1993 Steven Spielberg film Jurassic Park. However, the dimensions of the Velociraptor in the film are much larger than the largest members of that genus. Robert Bakker recalled that Spielberg had been disappointed with the dimensions of Velociraptor and so upsized it.[95] Gregory S. Paul, in his 1988 book Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, also considered Deinonychus antirrhopus a species of Velociraptor, and so rechristened the species Velociraptor antirrhopus.[39] This taxonomic opinion has not been widely followed.[10][96][97]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)