El noreste de la India , oficialmente la Región Nororiental ( NER ), es la región más oriental de la India y representa una división administrativa geográfica y política del país. [18] Comprende ocho estados : Arunachal Pradesh , Assam , Manipur , Meghalaya , Mizoram , Nagaland y Tripura (comúnmente conocidos como las "Siete Hermanas" ), y el estado "hermano" de Sikkim . [19]

La región comparte una frontera internacional de 5.182 kilómetros (3.220 millas) (aproximadamente el 99 por ciento de su límite geográfico total) con varios países vecinos: 1.395 kilómetros (867 millas) con China en el norte, 1.640 kilómetros (1.020 millas) con Myanmar en el este, 1.596 kilómetros (992 millas) con Bangladesh en el suroeste, 97 kilómetros (60 millas) con Nepal en el oeste y 455 kilómetros (283 millas) con Bután en el noroeste. [20] Comprende un área de 262.184 kilómetros cuadrados (101.230 millas cuadradas), casi el 8 por ciento de la de la India. El Corredor Siliguri conecta la región con el resto de la India continental .

Los estados de la Región Nororiental están oficialmente reconocidos por el Consejo Nororiental (NEC), [19] constituido en 1971 como la agencia interina para el desarrollo de los estados nororientales. Mucho después de la incorporación del NEC, Sikkim pasó a formar parte de la Región Nororiental como octavo estado en 2002. [21] [22] Los proyectos de conectividad Look-East de la India conectan el noreste de la India con el este de Asia y la ASEAN . La ciudad de Guwahati en Assam se conoce como la "Puerta al noreste" y es la metrópolis más grande del noreste de la India.

Los primeros colonos pueden haber sido hablantes austroasiáticos del sudeste asiático , seguidos por hablantes tibetano-birmanos de China, y hacia el 500 a. C. hablantes indoarios de las llanuras del Ganges , así como hablantes de kra-dai del sur de Yunnan y el estado de Shan . [23] Debido a la biodiversidad y la diversidad de cultivos de la región, los investigadores arqueológicos creen que los primeros colonos del noreste de la India habían domesticado varias plantas importantes. [24] Los historiadores creen que los escritos del año 100 a. C. del explorador chino Zhang Qian indican una ruta comercial temprana a través del noreste de la India. [25] El Periplo del mar Eritreo menciona a un pueblo llamado Sêsatai en la región, [26] que producía malabathron (hojas aromáticas parecidas a la canela, secadas y utilizadas como agente aromatizante), tan apreciadas en el viejo mundo. [27] La Geographia de Ptolomeo (siglo II d. C.) llama a la región Kirrhadia , aparentemente en honor a la población Kirata . [28]

En el período histórico temprano (la mayor parte del primer milenio d. C.), Kamarupa se extendía a ambos lados de la actual India nororiental. Xuanzang , un monje budista chino viajero, visitó Kamarupa en el siglo VII d. C. Describió a la gente como "de baja estatura y aspecto negro", cuyo habla difería un poco de la de la India central y que eran de disposición simple pero violenta. Escribió que la gente de Kamarupa conocía Sichuan , que se encontraba al este del reino más allá de una montaña traicionera. [29]

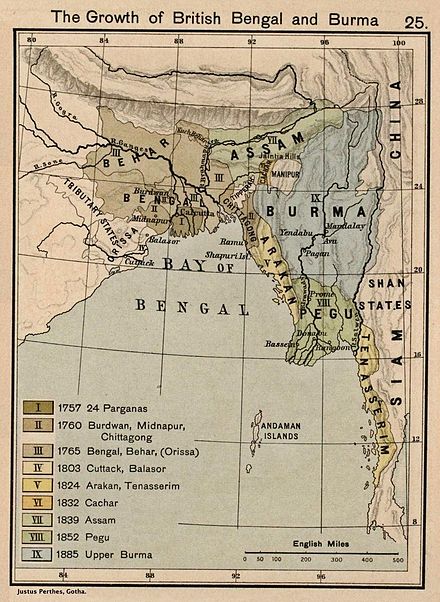

Los estados del noreste se establecieron durante el Raj británico de los siglos XIX y principios del XX, cuando quedaron relativamente aislados de sus socios comerciales tradicionales, como Bután y Myanmar . [30] Muchos de los pueblos de las actuales Mizoram, Meghalaya y Nagaland se convirtieron al cristianismo bajo la influencia de los misioneros británicos (galeses). [31]

Desde los disturbios de Moamoria , la dinastía Ahom estaba en decadencia. Los británicos aparecieron en escena bajo la apariencia de salvadores. [32] A principios del siglo XIX, tanto el reino Ahom como el de Manipur cayeron ante una invasión birmana . [32] La Primera Guerra Anglo-Birmana que siguió dio como resultado que toda la región quedara bajo control británico. En el período colonial (1826-1947), el noreste de la India pasó a formar parte de la provincia de Bengala desde 1839 hasta 1873, después de lo cual el Assam colonial se convirtió en su propia provincia , [33] pero que incluía a Sylhet .

Después de la independencia de la India del dominio británico en 1947, la región noreste de la India británica consistió en Assam y los estados principescos del Reino de Tripura y el Reino de Manipur . Posteriormente, Manipur y Tripura se convirtieron en Territorios de la Unión de la India en 1956 y en 1972 alcanzaron la condición de estado de pleno derecho. Más tarde, Nagaland alcanzó la condición de estado en 1963, Meghalaya en 1972. Arunachal Pradesh y Mizoram se convirtieron en estados de pleno derecho el 20 de febrero de 1987, al ser separados del gran territorio de Assam. [34] Sikkim se integró como el octavo estado del Consejo Nororiental en 2002. [21]

La ciudad de Shillong fue la capital de la provincia de Assam, creada durante el gobierno británico. Siguió siendo la capital de Assam hasta la formación del estado de Meghalaya en 1972. [35] La capital de Assam se trasladó a Dispur , una parte de Guwahati , y Shillong fue designada como la capital de Meghalaya. [ cita requerida ]

En un principio, los japoneses habían invadido territorios británicos en el sudeste asiático, incluida Birmania (hoy Myanmar), con la intención de crear un perímetro fortificado alrededor de Japón. Los británicos habían descuidado la defensa de Birmania y, a principios de 1942, los japoneses habían capturado Rangún y habían hecho retroceder a las fuerzas aliadas hacia la India mediante una agotadora retirada. [40]

En respuesta al avance japonés, los británicos formaron el Comando del Sudeste Asiático (SEAC) bajo el mando del almirante Lord Louis Mountbatten en noviembre de 1943. Este comando trajo nueva energía al esfuerzo bélico en la región y enfatizó la importancia de mantenerse firme y luchar a pesar de los desafíos logísticos, como durante la temporada de los monzones. [41]

En marzo de 1944, los japoneses lanzaron una ofensiva con el objetivo de capturar Imphal y Kohima, lugares clave en el noreste de la India. La captura de estas áreas les habría permitido interrumpir las líneas de suministro de los Aliados a China y lanzar ataques aéreos contra la India. [42]

Sin embargo, las fuerzas aliadas, bajo el mando del mariscal de campo William Slim, se mantuvieron firmes y adoptaron tácticas agresivas, incluida la creación de "cajas" defensivas y el uso de técnicas de guerra en la jungla. A pesar de estar rodeados, los defensores de Kohima resistieron los intensos ataques japoneses hasta que llegaron los refuerzos. [43]

Las batallas de Imphal y Kohima resultaron en una derrota decisiva para los japoneses, que sufrieron numerosas bajas y se vieron obligados a retirarse, lo que marcó un punto de inflexión en la Campaña de Birmania. La victoria aliada allanó el camino para posteriores ofensivas para expulsar a las fuerzas japonesas de Birmania y, en última instancia, condujo a la reconquista de la región. [44]

Arunachal Pradesh, un estado en el extremo noreste de la India, es reclamado por China como el Tíbet del Sur . [45] Las relaciones chino-indias se degradaron, lo que resultó en la Guerra chino-india de 1962. La causa de la escalada de la guerra aún es disputada por fuentes chinas e indias. Durante la guerra de 1962, la República Popular China (China) capturó gran parte de la NEFA ( Agencia de la Frontera del Noreste ) creada por la India en 1954. Pero el 21 de noviembre de 1962, China declaró un alto el fuego unilateral y retiró sus tropas 20 kilómetros (12 millas) detrás de la Línea McMahon . China devolvió a los prisioneros de guerra indios en 1963. [46]

Los Siete Estados Hermanos es un término popular para los estados contiguos de Arunachal Pradesh , Assam , Meghalaya , Manipur , Mizoram , Nagaland y Tripura antes de la inclusión del estado de Sikkim en la Región Nororiental de la India. El sobrenombre de "Tierra de las Siete Hermanas" fue acuñado para coincidir con la inauguración de los nuevos estados en enero de 1972 por Jyoti Prasad Saikia, [47] un periodista de Tripura, en el transcurso de un programa de radio. Más tarde compiló un libro sobre la interdependencia y la similitud de los Siete Estados Hermanos. Ha sido principalmente debido a esta publicación que el apodo se ha puesto de moda. [48]

La región del noreste se puede clasificar fisiográficamente en el Himalaya oriental , el Patkai y el Brahmaputra y las llanuras del valle de Barak . El noreste de la India (en la confluencia de los reinos biogeográficos indo-malayo, indochino e indio) tiene un clima subtropical predominantemente húmedo con veranos cálidos y húmedos, monzones severos e inviernos suaves. Junto con la costa occidental de la India, esta región tiene algunas de las últimas selvas tropicales restantes del subcontinente indio, que sustentan una flora y fauna diversa y varias especies de cultivos. Se estima que las reservas de petróleo y gas natural en la región constituyen una quinta parte del potencial total de la India. [ cita requerida ]

La región está cubierta por los poderosos sistemas fluviales Brahmaputra-Barak y sus afluentes. Geográficamente, aparte de los valles Brahmaputra , Barak e Imphal y algunas llanuras entre las colinas de Meghalaya y Tripura , los dos tercios restantes del área son terreno montañoso intercalado con valles y llanuras; la altitud varía desde casi el nivel del mar hasta más de 7.000 metros (23.000 pies) sobre el nivel del mar . La alta precipitación de la región, con un promedio de alrededor de 10.000 milímetros (390 pulgadas) y más, crea problemas en el ecosistema, alta actividad sísmica e inundaciones. Los estados de Arunachal Pradesh y Sikkim tienen un clima montañoso con inviernos fríos y nevados y veranos suaves. [ cita requerida ]

Kangchenjunga , el tercer pico montañoso más alto del mundo, con una altitud de 8.586 m (28.169 pies), se encuentra entre el estado de Sikkim y el país adyacente Nepal .

Afluentes del río Brahmaputra en el noreste de la India:

El noreste de la India tiene un clima subtropical que está influenciado por su relieve y las influencias de los monzones del suroeste y noreste . [49] [50] El Himalaya al norte, la meseta de Meghalaya al sur y las colinas de Nagaland, Mizoram y Manipur al este influyen en el clima. [51] Dado que los vientos monzónicos que se originan en la Bahía de Bengala se mueven hacia el noreste, estas montañas fuerzan los vientos húmedos hacia arriba, lo que hace que se enfríen adiabáticamente y se condensen en nubes, liberando fuertes precipitaciones en estas laderas. [51] Es la región más lluviosa del país, con muchos lugares que reciben una precipitación anual promedio de 2000 mm (79 pulgadas), que se concentra principalmente en verano durante la temporada de monzones . [51] Cherrapunji , ubicada en la meseta de Meghalaya, es uno de los lugares más lluviosos del mundo con una precipitación anual de 11 777 mm (463,7 pulgadas). [51] Las temperaturas son moderadas en las llanuras de los ríos Brahmaputra y Barak , y disminuyen con la altitud en las zonas montañosas. [51] En las altitudes más altas, hay una cubierta de nieve permanente. [51] En general, la región tiene 3 estaciones: invierno, verano y temporada de lluvias, en la que la temporada de lluvias coincide con los meses de verano, al igual que el resto de la India. [52] El invierno va desde principios de noviembre hasta mediados de marzo, mientras que el verano va desde mediados de abril hasta mediados de octubre. [51]

Según la clasificación climática de Köppen , la región se divide en 3 grandes tipos: A (climas tropicales), C (climas mesotérmicos templados cálidos) y D (climas microtérmicos de nieve). [53] [54] Los climas tropicales se encuentran en partes de Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram y las llanuras de Cachar al sur de los 25 o N y se clasifican como tropicales húmedos y secos ( Aw ). [53] Gran parte de Assam, Nagaland, partes del norte de Meghalaya y Manipur y partes de Arunachal Pradesh se incluyen en los climas mesotérmicos de temperatura cálida (tipo C), donde las temperaturas medias en los meses más fríos varían de −3 a 18 °C (27 a 64 °F). [54] [55] Todo el valle del Brahmaputra tiene un clima subtropical húmedo ( Cfa/Cwa ) con veranos calurosos. [54] [55] En altitudes entre 500 y 1.500 m (1.600 y 4.900 pies) ubicadas en las colinas orientales de Nagaland, Manipur y Arunachal Pradesh, prevalece un clima ( Cfb/CWb ) con veranos cálidos. [54] [55] Las ubicaciones por encima de los 1.500 m (4.900 pies) en Meghalaya, partes de Nagaland y el norte de Arunachal Pradesh tienen un clima ( Cfc/Cwc ) con veranos cortos y frescos. [55] Finalmente, las partes extremas del norte de Arunachal Pradesh se clasifican como climas continentales húmedos con temperaturas medias invernales por debajo de −3 °C (27 °F). [54] [56]

Las temperaturas varían según la altitud, siendo los lugares más cálidos los que se encuentran en las llanuras de los ríos Brahmaputra y Barak , y los más fríos los que se encuentran en las altitudes más altas. [57] También está influenciada por la proximidad al mar, ya que los valles y las áreas occidentales están cerca del mar, lo que modera las temperaturas. [57] En general, las temperaturas en las áreas montañosas y montañosas son más bajas que en las llanuras, que se encuentran a menor altitud. [58] Las temperaturas de verano tienden a ser más uniformes que las temperaturas de invierno debido a la alta cobertura de nubes y la humedad. [59]

En las llanuras fluviales del valle de Brahmaputra y Barak, las temperaturas medias de invierno varían entre 16 y 17 °C (61 y 63 °F), mientras que las temperaturas medias de verano rondan los 28 °C (82 °F). [57] Las temperaturas de verano más altas se dan en la llanura de Tripura occidental, con Agartala , la capital de Tripura , con temperaturas máximas medias de verano que oscilan entre 33 y 35 °C (91 y 95 °F) en abril. [60] Las temperaturas más altas en verano se dan antes de la llegada de los monzones y, por tanto, las zonas orientales tienen las temperaturas más altas en junio y julio, donde el monzón llega más tarde que las zonas occidentales. [60] En la llanura de Cachar, situada al sur de la llanura de Brahmaputra, las temperaturas son más altas que en la llanura de Brahmaputra, aunque el rango de temperatura es menor debido a la mayor cobertura de nubes y a los monzones que moderan las temperaturas nocturnas durante todo el año. [58] [60]

En las zonas montañosas de Arunachal Pradesh, las cordilleras del Himalaya en la frontera norte con India y China experimentan las temperaturas más bajas con fuertes nevadas durante el invierno y temperaturas que caen por debajo del punto de congelación. [58] Las áreas con altitudes superiores a los 2000 metros (6562 pies) reciben nevadas durante los inviernos y tienen veranos frescos. [58] Por debajo de los 2000 metros (6562 pies) sobre el nivel del mar, las temperaturas invernales alcanzan hasta 15 °C (59 °F) durante el día y las noches caen a cero mientras que los veranos son frescos, con una máxima media de 25 °C (77 °F) y una mínima media de 15 °C (59 °F). [58] En las zonas montañosas de Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur y Mizoram, los inviernos son fríos mientras que los veranos son frescos. [59]

Las llanuras de Manipur tienen temperaturas mínimas invernales más frías de lo que justifica su altitud debido a que están rodeadas de colinas por todos lados. [61] Esto se debe a las inversiones de temperatura durante las noches de invierno, cuando el aire frío desciende de las colinas a los valles de abajo, y a su ubicación geográfica, que impide que los vientos que traen temperaturas cálidas y humedad entren en la llanura de Manipur. [61] Por ejemplo, en Imphal, las temperaturas diurnas de invierno rondan los 21 °C (70 °F), pero las temperaturas nocturnas bajan a 3 °C (37 °F). [61]

Ninguna parte del noreste de la India recibe menos de 1.000 mm (39 pulgadas) de lluvia al año. [52] Las áreas en el valle de Brahmputra reciben 2.000 mm (79 pulgadas) de lluvia al año, mientras que las áreas montañosas reciben de 2.000 a 3.000 mm (79 a 118 pulgadas) al año. [52] El monzón del suroeste es responsable de traer el 90% de la lluvia anual a la región. [62] De abril a finales de octubre son los meses en los que se produce la mayor parte de la lluvia en el noreste de la India, siendo junio y julio los meses más lluviosos. [62] En la mayor parte de la región, la fecha media de inicio de los monzones es el 1 de junio. [63] Las áreas del sur son las primeras en recibir el monzón (mayo o junio), mientras que el valle de Brahmaputra y el norte montañoso lo reciben más tarde (finales de mayo o junio). [62] En las partes montañosas de Mizoram, la proximidad a la Bahía de Bengala hace que se experimenten monzones tempranos, siendo junio la estación más lluviosa. [62]

La región nororiental de la India es una zona propensa a megaterremotos causados por planos de falla activos debajo formados por la convergencia de tres placas tectónicas , a saber, la placa de la India , la placa euroasiática y la placa de Birmania . Históricamente, la región ha sufrido dos grandes terremotos (M > 8,0) - el terremoto de Assam de 1897 y el terremoto de Assam-Tíbet de 1950 - y alrededor de 20 grandes terremotos (8,0 > M > 7,0) desde 1897. [64] [65] El terremoto de Assam-Tíbet de 1950 sigue siendo el terremoto más grande en la India . [ cita requerida ]

.jpg/440px-A_scene_from_Kanchenjunga_National_Park,_Sikkim_(1).jpg)

WWF ha identificado todo el Himalaya oriental como una ecorregión prioritaria de Global 200. Conservation International ha ampliado la escala del punto crítico del Himalaya oriental para incluir los ocho estados del noreste de la India, junto con los países vecinos de Bután , el sur de China y Myanmar .

El Consejo Indio de Investigación Agrícola ha identificado la región como un centro de germoplasma de arroz. La Oficina Nacional de Recursos Fitogenéticos (NBPGR), India, ha destacado la región como rica en parientes silvestres de plantas de cultivo. Es el centro de origen de los frutos cítricos. Se han reportado dos variedades primitivas de maíz, Sikkim Primitive 1 y 2, en Sikkim (Dhawan, 1964). Aunque el cultivo jhum , un sistema tradicional de agricultura, se cita a menudo como una razón para la pérdida de la cubierta forestal de la región, esta actividad económica agrícola primaria practicada por las tribus locales apoyó el cultivo de 35 variedades de cultivos. La región es rica en plantas medicinales y muchos otros taxones raros y en peligro de extinción . Su alto endemismo tanto en plantas superiores , vertebrados y diversidad aviar la ha calificado como un punto crítico de biodiversidad .

Las siguientes cifras resaltan la importancia de la biodiversidad de la región: [66]

El Consejo Internacional para la Preservación de las Aves del Reino Unido identificó las llanuras de Assam y el Himalaya oriental como un Área de Aves Endémicas (EBA). El EBA tiene una superficie de 220.000 km2 siguiendo la cordillera del Himalaya en los países de Bangladesh, Bután, China, Nepal, Myanmar y los estados indios de Sikkim , Bengala del Norte , Assam, Nagaland , Manipur , Meghalaya y Mizoram . Debido a que esta cordillera se encuentra más al sur en comparación con otras cordilleras del Himalaya, esta región tiene un clima claramente diferente, con temperaturas medias más cálidas y menos días con heladas, y precipitaciones mucho más elevadas. Esto ha dado lugar a la aparición de una rica variedad de especies de aves de distribución restringida. Más de dos especies en peligro crítico, tres especies en peligro y 14 especies de aves vulnerables se encuentran en esta EBA. Stattersfield et al. (1998) identificaron 22 especies de distribución restringida, de las cuales 19 están confinadas a esta región y las tres restantes están presentes en otras áreas endémicas y secundarias. Once de las 22 especies de distribución restringida que se encuentran en esta región se consideran amenazadas ( Birdlife International 2001), un número mayor que en cualquier otra EBA de la India. [ cita requerida ]

El noreste de la India es muy rico en diversidad faunística. Hay hasta 15 especies de primates no humanos y las más importantes de ellas son el gibón hoolock , el macaco stumpti, el macaco de cola de cerdo, el langur dorado, el langur hanuman y el mono rhesus. La especie más importante y en peligro de extinción es el rinoceronte de un cuerno. Los bosques de la región también son hábitat de elefantes, tigres reales de Bengala, leopardos, gatos dorados, gatos pescadores, gatos jaspeados, zorros de Bengala, etc. El delfín del Ganges en el Brahmaputra también es una especie en peligro de extinción. Las otras especies en peligro de extinción son la nutria, el cocodrilo de las marismas, la tortuga y algunos peces. [67]

WWF ha identificado las siguientes ecorregiones prioritarias en el noreste de la India:

The total population of Northeast India is 46 million with 68 per cent of that living in Assam alone. Assam also has a higher population density of 397 persons per km2 than the national average of 382 persons per km2. The literacy rates in the states of the Northeastern region, except those in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, are higher than the national average of 74 per cent. As per 2011 census, Meghalaya recorded the highest population growth of 27.8 per cent among all the states of the region, higher than the national average at 17.64 per cent; while Nagaland recorded the lowest in the entire country with a negative 0.5 per cent.[73]

According to 2011 Census of India, the largest cities in Northeast India are

Northeast India constitutes a single linguistic region within the Indian national context, with about 220 languages in multiple language families (Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Kra–Dai, Austroasiatic, as well as some creole languages) that share a number of features that set them apart from most other areas of the Indian subcontinent (such as alveolar consonants rather than the more typical dental/retroflex distinction).[75][76] Assamese, an Indo-Aryan language spoken mostly in the Brahmaputra Valley, developed as a lingua franca for many speech communities. Assamese-based pidgin/creoles have developed in Nagaland (Nagamese) and Arunachal (Nefamese),[77] though Nefamese has been replaced by Hindi in recent times. Bengali language is another Indo-Aryan language spoken in South Assam in the Barak Valley and Tripura, being the majority and official language in both the regions. The Austro-Asiatic family is represented by the Khasi, Jaintia and War languages of Meghalaya. A small number of Tai–Kadai languages (Ahom, Tai Phake, Khamti, etc.) are also spoken. Sino-Tibetan is represented by a number of languages that differ significantly from each other,[78] some of which are: Boro, Rabha, Karbi, Mising, Tiwa, Deori, Hmar (including Biate, Chorei, Halam, Hrangkhawl, Kaipeng, Molsom, Ranglong, Saihriem, Sakachep, Thangachep, Thiek), Zeme Naga, Rengma Naga and, Kuki (Thadou language) (Assam); Garo, Rabha, Hmar (including Biate, Sakachep) (Meghalaya); Ao, Angami, Sema, Lotha, Konyak, Chakhesang, Chang, Khiamniungan, Phom, Pochury, Rengma, Sangtam, Tikhir, Yimkhiung, Zeliang, Kuki (Thadou), and Hmar (including Sakachep/Khelma) etc. (Nagaland); Mizo languages such as Lusei (including Hualngo), Hmar (including Chorei, Darlawng, Darngawn, Kaipeng, Khawlhring, Molsom, Ngente, Sakachep, Zote), Lai (including Hakha, Falam, Khualsim, Zanniet, Sim), Mara languages, Ralte/Galte, Zomi/Paihte, Kuki/Thahdo, etc. (Mizoram); Hrusso, Tanee, Niyshi, Adi, Abor, Nocte, Apatani, Mishmi etc. (Arunachal). Kokborok is the dominant among the tribal people of Tripura and one of the official languages of the state, while Garo, Hmar (including Bong, Bongcher, Chorei, Dab, Darlawng, Hmarchaphang, Hrangkhawl, Langkai, Kaipeng, Koloi, Korbong, Molsom, Ranglong, Rupini, Saihmar, Sakachep, Thangachep)), Lusei (including Rokhum), etc are also spoken. Meitei is the official language in Manipur, the dominant language of the Imphal Valley; while "Naga" languages such as Poumai, Mao, Maram, Rongmei (Kabui),Tangkhul, Zeme, Liangmei, Inpui, Thangal Naga and Mizo languages such as Kuki/Thado, Lusei, Zomi languages (including Paite, Simte, Vaiphei, Zou, Mate, Thangkhal, Tedim-Chin), Gangte and Hmar languages (including Biete, Hrangkhawl, Thiek, Zote) predominate in individual hill areas of the state.[79]

Among other Indo-Aryan languages, Chakma is spoken in Mizoram and Hajong in Assam and Meghalaya. Nepali, an Indo-Aryan language, is dominant in Sikkim, besides the Sino-Tibetan languages Limbu, Bhutia, Lepcha, Rai, Tamang, Sherpa, etc. Bengali was made the official language of Colonial Assam from 1836 to 1873.[82]

Religion in Northeast India (2011)

Hinduism is the majority religion in the North Eastern states of Assam, Tripura, Manipur, Sikkim and plurality in Arunachal Pradesh, while Christianity is the majority religion in Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram and plurality in Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. A significant plurality of the state of Arunachal Pradesh follows the indigenous religion Donyi-Polo. Islam has a significant presence in Assam and about 93% of all North East Muslim population is concentrated in that state alone. A bulk of Christian population in India resides in North East, as about 30% of India's Christian population is concentrated in North Eastern region alone. There is a significant presence of Buddhism in Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram.[88]

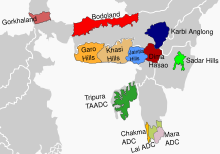

Northeast India has over 220 ethnic groups and an equal number of dialects in which Bodo form the largest indigenous ethnic group.[90] The hills states in the region like Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland are predominantly inhabited by tribal people with a degree of diversity even within the tribal groups. The region's population results from ancient and continuous flows of migrations from Tibet, Indo-Gangetic India, the Himalayas, present Bangladesh, and Myanmar.[91]

These ethnic groups form significant majorities in the states/regions of Northeast India:

These ethnic groups form minorities in the states of Northeast India:

The Manipuri Raas Leela dance (from Manipur) and the Sattriya (from Assam) have been included in the elite category of the "Classical Dances of India", as officially recognised by both the Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Ministry of Culture (India). Besides these, all tribes in Northeast India have their own folk dances associated with their religion and festivals. The tribal heritage in the region is rich with the practice of hunting, land cultivation and indigenous crafts. The rich culture is vibrant and visible with the traditional attires of each community.[citation needed]

All states in Northeast India share the handicrafts of bamboo and cane, wood carving, making traditional weapons and musical instruments, pottery and handloom weaving. Traditional tribal attires are made of thick fabrics primarily with cotton.[92] Assam silk is a famous industry in the region.

Northeast is a hub of different genres of music. Each community has its own rich heritage of folk music. Talented musicians and singers are plentifully found in this part of the country. The Assamese singer-composer Bhupen Hazarika achieved national and international fame with his remarkable creations. Another famous singer from Assam, Pratima Barua Pandey is a well-known folk singer. Zubeen Garg, Papon, Anurag Saikia are some other notable singers, musicians from the state of Assam. Tangkhul Naga folk blue singer like Rewben Mashangva, who comes from Ukhrul, is an acclaimed Folk singer whose music is inspired by the like of Bob Dylan and Bob Marley. Another famous folk singing band from Nagaland popularly known as Tetseo Sisters is one to be noted for their original music genre. However, younger generation has started pursuing western music more and more nowadays. The northeast region has seen a significant increase in musical innovation in the 21st century.[102]

Many of the Northeast Indian indigenous communities have an ancient heritage of folktales which tell the tale of their origin, rituals, beliefs and so on. These tales are transmitted from one generation to another in oral form. They are remarkable instances of tribal wisdom and imagination. However, Assam, Tripura and Manipur have some ancient written texts. These states were mentioned in the great Hindu epic Mahabharata. The Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by Madhava Kandali is considered the first translation of the Sanskrit Ramayana into a modern Indo-Aryan Language. Karbi Ramayana bears witness to the old heritage of written literature in Assam. Two writers from the Northeast, viz., Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya and Mamoni Raisom Goswami, have been awarded Jnanpith, the highest literary award in India.[103] Hence, Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya was the first Assamese writer and from the Northeast India to receive Jnanpith Award for his Assamese novel Mrityunjay (1979).[104] Mamoni Raisom Goswami was awarded the Jnanpith Award in the year 2000.[103] Nagen Saikia is the first writer from Assam and the Northeast India, to have been conferred the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship by the Sahitya Akademi.[105][106] Some of the notable writers of Northeast Literature are--(from Assam) Lakshminath Bezbaroa, Homen Borgohain, Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya, Harekrishna Deka, Rongbong Terang, Nilmani Phukan, Indira Goswami, Hiren Bhattacharyya, Mitra Phukan, Jahnavi Barua, Dhruba Hazarika, Rita Chowdhury; (from Arunachal Pradesh) Mamang Dai; (from Manipur) Robin S Ngangom, Ratan Thiyam; (from Meghalaya) Paul Lyngdoh; (from Nagaland) Temsula Ao, Easterine Kire; (from Sikkim) Rajendra Bhandari. Temsula Ao is the first writer from Northeast India to be awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award (2013) in the Indian English Literature category for her collection of short stories, Laburnum for My Head, and Padma Shri (2007). Easterine Kire is the first English novelist hailed from Nagaland. She received The Hindu Literary Prize (2015) for her novel When the River Sleeps. Indira Goswami, alias Mamoni Roisom Goswami, is an acclaimed Assamese writer whose novels include Moth-Eaten Howda of the Tusker, Pages Stained with Blood, The Shadow of Kamakhya and The Blue-Necked God. Mamang Dai won the Sahitya Akademi Award (2017) for her novel The Black Hill.[107]

Indigenous festivals in the northeast include the Ojiale festival of the Wancho people, Chhekar festival of the Sherdukpen people, Longte Yullo festival of Nishis, Solung festival of Adis, Losar festival of Monpas, Reh festival of Idu Mishmis and Dree festival of Apatani. Mamita Tripurabda(Tring festival), Buisu, Hangrai, Hojagiri, Kharchi and Garia festivals of Tripura, [108] In Manipur popular festivals include Ningol Chakouba and the Manipur boat racing festival or the Heikru Hidongba, Chasok Tangnam festival of Limbu people.

The northeastern states, having 3.8% of India's total population, are allotted 25 out of a total of 543 seats in the Lok Sabha. This is 4.6% of the total number of seats.[citation needed]

In 1947 Indian independence and partition resulted in the North East becoming a landlocked region. This exacerbated the isolation that has been recognised, but not studied. East Pakistan controlled access to the Indian Ocean.[113] The mountainous terrain has hampered the construction of road and railways connections in the region.[citation needed]

Several militant groups have formed an alliance to fight against the governments of India, Bhutan, and Myanmar, and now use the term "Western Southeast Asia" (WESEA) to refer to the region.[114] The separatist groups include the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP), Kanglei Yawol Kanna Lup (KYKL), People's Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK), People's Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak-Pro (PREPAK-Pro), Revolutionary People's Front (RPF) and United National Liberation Front (UNLF) of Manipur, Hynniewtrep National Liberation Council (HNLC) of Meghalaya, Kamatapur Liberation Organization (KLO), which operates in Assam and North Bengal, National Democratic Front of Bodoland and ULFA of Assam, and the National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT).[115]

The Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (MDoNER) is the deciding body under Government of India for socio-economic development in the region. The North Eastern Council under MDoNER serves as the regional governing body for Northeast India. The North Eastern Development Finance Corporation Ltd. (NEDFi) is a public limited company providing assistance to micro, small, medium and large enterprises within the northeastern region (NER). Other organisations under MDoNER include North Eastern Regional Agricultural Marketing Corporation Limited (NERAMAC), Sikkim Mining Corporation Limited (SMC) and North Eastern Handlooms and Handicrafts Development Corporation (NEHHDC).

The economy is agrarian. Little land is available for settled agriculture. Along with settled agriculture, jhum (slash-and-burn) cultivation is still practised by a few indigenous groups of people. The inaccessible terrain and internal disturbances have made rapid industrialisation difficult in the region.[citation needed]

Living Root Bridges

Northeast India is also the home of many living root bridges. In Meghalaya, these can be found in the southern Khasi and Jaintia Hills.[116][117][118] They are still widespread in the region, though as a practice they are fading out, with many examples having been destroyed in floods or replaced by more standard structures in recent years.[119] Living root bridges have also been observed in the state of Nagaland, near the Indo-Myanmar border.[120]

Northeast India has several newspapers in both English and regional languages. The largest circulated English daily in Assam is The Assam Tribune. In Meghalaya, The Shillong Times is the highest circulated newspaper. In Nagaland, Nagaland Post has the highest number of readers. G Plus is the only print and digital English weekly tabloid published from Guwahati. In Manipur, Imphal Free Press is a highly respected newspaper. In Arunachal Pradesh, The Arunachal Times is the highest circulated newspaper in Arunachal Pradesh.[citation needed]

States in the North Eastern Region are well connected by air-transport conducting regular flights to all major cities in the country. The states also own several small airstrips for military and private purposes which may be accessed using Pawan Hans helicopter services. The region currently has two international airports viz. Lokapriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport, Bir Tikendrajit International Airport Maharaja Bir Bikram Airport conducting flights to Thailand, Myanmar, Nepal and Bhutan. While the airport in Sikkim is under-construction, Bagdogra Airport (IATA: IXB, ICAO: VEBD) remains the closest domestic airport to the state.

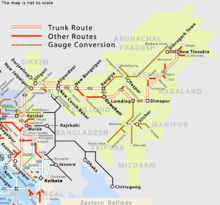

Railway in Northeast India is delineated as Northeast Frontier Railway zone of Indian Railways. The regional network is underdeveloped. States of Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Sikkim will remain almost disconnected till March 2023 when the capital cities of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland are expected to get the rail links once the under construction rail projects are completed.[121]

In the 21st century, there has been recognition among policymakers and economists of the region that the main stumbling block for economic development of the Northeastern region is the disadvantageous geographical location.[122] It was argued that globalisation propagates deterritorialisation and a borderless world which is often associated with economic integration. With 98 per cent of its borders with China, Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal, Northeast India appears to have a better scope for development in the era of globalisation.[123] As a result, a new policy developed among intellectuals and politicians that one direction the Northeastern region must be looking to as a new way of development lies with political integration with the rest of India and economic integration with the rest of Asia and Oceania, with North, East and Southeast Asia, Micronesia and Polynesia in particular, as the policy of economic integration with the rest of India did not yield much dividends. With the development of this new policy, the Government of India directed its Look East policy towards developing the Northeastern region. This policy is reflected in the Year End Review 2004 of the Ministry of External Affairs, which stated that: "India’s Look East Policy has now been given a new dimension by the UPA Government. India is now looking towards a partnership with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN countries, both within BIMSTEC and the India-ASEAN Summit dialogue as integrally linked to economic and security interests, particularly for India’s East and North East region."[124]

The north-east (NE) region of India lags behind the rest of the country in several development indicators. Although infrastructure has developed over the years, the region has to go a long way to level up the national standard. The total road network of about 377 thousand km of NE contributes about 9.94 per cent of the total roads in the country. Road density in terms of road length per thousand square kilometres. area is very poor in hilly state of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Meghalaya and Sikkim, while it is significantly high in Tripura and Assam. The road length per 100 km2 area in NE districts varies from as less as below 10 km (in Arunachal Pradesh) to more than 200 km (in Tripura). Other means of transport such as rail, air and water is insignificant in NE (except Assam); however, a few cities of these states having direct air connectivity in the region. The total railway network in the NE is 2,602 km (as on 2011), which is only about 4 per cent of the total rail network of the country. Constructions of roads build the road map for development and road is the only means of mass transport for the entire NE of India. Due to hilly terrain and varied altitudes, rail transport is mainly confined to Assam and water transport is almost non-existent.

India's road network has benefited greatly from the articulation of the National Highways Development Project (NHDP). The Ministry has formulated the Special Accelerated Road Development Programme for North East (SARDP-NE) for the development/improvement of more than 10,000 km roads in the NE states. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) has been paying special attention to the development of national highways in the region and has assigned 10 per cent of the total allocation of fund for the NE region.

Another major constraint of surface infrastructure projects in the NE states has to be linked up with parallel developments in the neighbouring countries, particularly with Bangladesh. The restoration and extension of pre-partition land and river transit routes through Bangladesh is vital for transport infrastructure in NE states. Other international cooperation, such as, revival of Ledo road (Stilwell road) connecting Ledo in Assam to northern Myanmar and extended up to Kunming in south-eastern China, Kaladan Multimodal Transit Project and Trans-Asian Railways, could open up an eastern window for the land-locked NE states of India. Various regional initiatives, such as, the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) and Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway (IMTTH) project to link the markets of South and Southeast Asia, are in very initial stages.[125]

The first group of migrants to settle in this part of the country is perhaps the Austro-Asiatic language speaking people who came here from South-East Asia a few millennia before Christ. The second group of migrants came to Assam from the north, north-east and east. They are mostly the Tibeto-Burman language speaking people. From about the fifth century before Christ, there started a trickle of migration of the people speaking Indo-Aryan language from the Gangetic plain.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)