La Sinfonía n.º 9 en re menor , WAB 109, es la última sinfonía en la que trabajó Anton Bruckner , dejando incompleto el último movimiento en el momento de su muerte en 1896; Bruckner la dedicó "al amado Dios" (en alemán, dem lieben Gott ). La sinfonía fue estrenada bajo la dirección de Ferdinand Löwe en Viena en 1903.

Se dice que Bruckner dedicó su Novena Sinfonía al "Dios amado". August Göllerich y Max Auer, en su biografía de Bruckner, Ein Lebens- und Schaffensbild, afirman que Bruckner expresó a su médico, Richard Heller, esta dedicatoria de su obra diciendo:

Ya veis, ya he dedicado dos sinfonías de majestad terrenal al pobre rey Luis, como real mecenas de las artes [VII. Sinfonía, nota d. Ed.] A nuestro ilustre y querido Emperador, como a la más alta majestad terrenal, a quien reconozco [VIII. Sinfonía, nota d. Ed.] Y ahora dedico mi última obra a la majestad de todas las majestades, al amado Dios, y espero que me conceda tanto tiempo para completarla. [1]

Inmediatamente después de completar la primera versión de su Octava Sinfonía el 10 de agosto de 1887, Bruckner comenzó a trabajar en su Novena. Los primeros bocetos, que se conservan en la Biblioteca Jagiellońska de Cracovia, están fechados entre el 12 y el 18 de agosto de 1887. [2] [3] Además, la primera partitura del primer movimiento está fechada el 21 de septiembre de 1887.

El trabajo en el primer movimiento se interrumpió pronto. El director Hermann Levi, a quien Bruckner acababa de enviar la partitura de su Octava, consideró que la orquestación era imposible y la elaboración de los temas "dudosa", por lo que sugirió a Bruckner que la rehiciera. [4] Bruckner se puso a revisarla en 1888. Durante la revisión de su Octava, también revisó su Tercera sinfonía entre marzo de 1888 y marzo de 1889.

El 12 de febrero de 1889, mientras revisaba su Octava y Tercera Sinfonía, Bruckner comenzó a preparar su Segunda Sinfonía para su publicación. El 10 de marzo de 1890, completó su Octava Sinfonía antes de realizar más revisiones de su Primera y Cuarta Sinfonías y de su Misa en fa menor . [5]

Bruckner anunció en una carta fechada el 18 de febrero de 1891 al crítico Theodor Helm: "Hoy hay secretos en voz alta. ¡Señor Doctor! [...] Tercer secreto. La Novena Sinfonía (en re menor) ha comenzado", [6] ocultando el hecho de que sus primeros bocetos de la Novena habían sido escritos casi cuatro años antes. [5] Bruckner compuso entonces dos obras sinfónicas-corales, una versión del Salmo 150 (1892) y la obra coral masculina Helgoland (1893) .

El 23 de diciembre de 1893, se completó el primer movimiento de la Novena, después de seis años. El Scherzo (segundo movimiento), esbozado ya en 1889, se completó el 15 de febrero de 1894. [7] Bruckner compuso tres versiones sucesivas del Trío :

El Adagio (tercer movimiento) se completó el 30 de noviembre de 1894. En lo que respecta al último movimiento, en el calendario de Bruckner se puede encontrar la siguiente entrada: "24. Mai [1]895 1.mal Finale neue Scitze" ("24 de mayo de 1895, primer nuevo esbozo del final"). [12] [13] En general, el trabajo en la Novena se extendió a lo largo del largo período de 1887 a 1896 y tuvo que ser interrumpido repetidamente debido a revisiones de otras obras y al deterioro de la salud de Bruckner. Bruckner murió mientras trabajaba en el cuarto movimiento, antes de completar la sinfonía.

La Novena Sinfonía tiene una única versión, compuesta por tres movimientos con amplios bocetos del final. Si Bruckner hubiera vivido para completar el final, casi con toda seguridad habría repasado los demás movimientos y realizado ajustes. Por lo tanto, lo que tenemos es un trabajo en progreso. [14]

— Libro rojo de Bruckner

Los tres primeros movimientos de la Novena fueron estrenados en Viena, en la Musikvereinssaal el 11 de febrero de 1903 por la Orquesta de Concertos de Viena, precursora de la Sinfonía de Viena , bajo la dirección de Ferdinand Löwe en un arreglo propio. Löwe cambió profundamente la partitura original de Bruckner al adaptar la orquestación de Bruckner en el sentido de un acercamiento al ideal de sonido de Wagner , e hizo cambios en la armonía de Bruckner en ciertos pasajes (sobre todo en el clímax del Adagio). Publicó su versión alterada sin comentarios, y esta edición fue considerada durante mucho tiempo como el original de Bruckner. En 1931, el musicólogo Robert Haas señaló las diferencias entre la edición de Löwe y los manuscritos originales de Bruckner. [15] Al año siguiente, el director Siegmund von Hausegger interpretó tanto la partitura editada por Löwe como la partitura original de Bruckner, de modo que el estreno real de los tres primeros movimientos de la Novena Sinfonía de Bruckner tuvo lugar el 2 de abril de 1932 en Múnich. La primera grabación (publicada en LP en la década de 1950) fue realizada por Hausegger con la Filarmónica de Múnich en la versión original (editada por Alfred Orel ) en abril de 1938. [16]

Bruckner amplió la forma sinfónica de forma extrema utilizando el sonido negativo del silencio, secuenciando fases, ampliando picos y procesos de decadencia. Bruckner tenía sus raíces en la música de Palestrina, Bach , Beethoven y Schubert [17] y también fue un innovador de la armonía de finales del siglo XIX (junto con Franz Liszt ). Bruckner continúa su camino sinfónico al adherirse a la forma sonata en la Novena Sinfonía. También expande la forma, realzándola hasta lo monumental. Esta expansión del aparato de orquesta es también una expresión de este aumento de masa. [18]

"Si se observa el conjunto de instrumentos que utiliza Bruckner, lo más sorprendente es la cantidad de sonido que hasta entonces era desconocida en la música absoluta... La orquesta de la IX sinfonía de Bruckner es sólo el punto final de la línea de desarrollo auditivo de Bruckner en lo que respecta a los medios utilizados... El factor decisivo, sin embargo, no es la cantidad de medios expresivos, sino la forma en que se utilizan... Como en las cuerdas del grupo, los instrumentos de viento de madera y de metal se yuxtaponen, se vuelven a acoplar de las más diversas maneras y se unen para formar un todo inseparable, lo mismo que los instrumentos de estos grupos en cuanto al sonido individual. Por un lado, la obra abierta, por otro lado, la peculiaridad de Bruckner de formar sus temas a menudo a partir de frases cortas, significan que rara vez un instrumento surge como solista durante mucho tiempo sin interrupción."

— Anton Bruckner, Das Werk – Der Künstler – Die Zeit

Según Ekkehard Kreft, "las fases de mejora en la Novena Sinfonía adquieren un nuevo significado, ya que sirven para dar forma al carácter procesual [ sic ] desde el punto de partida del complejo temático (primer tema) hasta su destino final (tema principal)". [19] Tanto en la primera frase como en el movimiento final esto se expresa en una dimensión hasta ahora desconocida. La entrada del tema principal está precedida por una fase de aumento armoniosamente complicada. El uso de esta armonía cada vez más compleja convierte a Bruckner en el pionero de desarrollos posteriores. El musicólogo Albrecht von Mossow resume esto con respecto a la Novena de la siguiente manera: "A los desarrollos materiales de la modernidad se deben atribuir a Bruckner, como a otros compositores del siglo XIX, la creciente emancipación de la disonancia, la cromatización de la armonía, el debilitamiento de la tonalidad, el toque de los armónicos triádicos mediante la creciente inclusión de sonidos de cuatro y cinco tonos, las rupturas formales dentro de sus movimientos sinfónicos y la revalorización del timbre a un parámetro casi independiente". [20]

La Novena Sinfonía tiene grandes oleadas de desarrollo, clímax y decadencia, que el psicólogo musical Ernst Kurth describe como un "contraste de amplitud y vacío específicos del sonido en comparación con la compresión y posición cumbre anteriores". [21] Kurth compara esto con la composición de Stockhausen de 1957 ' Gruppen ', donde la estructura también se muestra en el desmembramiento del aparato individual en lugar de la génesis lineal, diciendo que Bruckner transfiere una riqueza de sonidos, colores y caracteres, y no solo concepciones espaciales del sonido al aparato instrumental. [22]

La fuga es inusual debido a su posición prominente en el movimiento final de la Novena Sinfonía, aunque la inclusión de una fuga en el contexto sinfónico de Bruckner no es infrecuente. Como escribe Rainer Bloss (traducido del alemán): "El tema principal del final de la Novena Sinfonía tiene una peculiaridad, porque su forma cambia, se transforma en sus dos últimos compases... La 'inusual' extensión de dos compases de Bruckner demuestra esta regresión modular de manera excepcional". [23]

Bruckner afina cada vez más su técnica de citación en la Novena Sinfonía. Paul Thissen lo resume en su análisis (traducido del alemán): "Sin duda, la forma de integración de citas utilizada por Bruckner en el Adagio de la Novena Sinfonía muestra el aspecto más diferenciado. Abarca desde la técnica del mero montaje (como en el Miserere ) hasta la penetración de la secuencia con transformaciones similares al Kyrie ". [24]

La sinfonía tiene cuatro movimientos , aunque el final es incompleto y fragmentario:

Gran parte del material para el final de la partitura completa puede haberse perdido muy poco después de la muerte del compositor; algunas de las secciones perdidas de la partitura completa sobrevivieron solo en formato de boceto de dos a cuatro pentagramas. La ubicación del segundo scherzo y la tonalidad, re menor , son solo dos de los elementos que esta obra tiene en común con la Novena sinfonía de Beethoven .

La sinfonía se interpreta tan a menudo sin ningún tipo de final que algunos autores describen "la forma de esta sinfonía [como]... un arco masivo, dos movimientos lentos a caballo entre un enérgico Scherzo". [26]

La partitura requiere tres flautas, tres oboes, tres clarinetes en si bemol y la, tres fagotes, tres trompetas en fa, tres trombones, ocho trompas (del 5.º al 8.º doblando las tubas de Wagner ), una tuba contrabajo , timbales y cuerdas .

El primer movimiento en re menor ( alla breve ) es un movimiento de sonata de diseño libre con tres grupos temáticos. Al principio, las cuerdas en el trémolo entonan la nota fundamental re, que se solidifica en el tercer compás por los instrumentos de viento de madera. Un primer núcleo temático suena en las trompas como una "repetición de tono (fundamental) en el ritmo de triple puntillo, a partir del cual se disuelve el intervalo de la tercera, luego la quinta, encaja en la estructura del orden métrico subyacente mediante golpes de cesura de los timbales y las trompetas. Difícilmente puede comenzar una sinfonía más primitiva, elemental, arquetípica". [28] El fenómeno típico de la división del sonido para Bruckner ocurre en el compás 19: la nota fundamental re se disocia en sus notas vecinas mi bemol y re bemol . Un audaz ascenso de mi bemol mayor de las trompas anuncia algo auspicioso. Como resultado, una fase de desarrollo prolongada prepara la entrada del tema principal. La música de Bruckner es específica, y esto subyace a su principio de desarrollo y exploración del sonido. [29] El camino de Bruckner hacia la creación de este tema se hace más largo; lleva cada vez más tiempo que la idea principal surja.

El potente tema principal del primer movimiento impresiona, ya que el espacio sonoro en re menor se confirma primero con la transposición rítmicamente impactante de octavas de las notas re y la, con una desviación repentina del sonido a do bemol mayor, reinterpretado como dominante a mi menor. El tema sigue una cadencia múltiple sobre do mayor y sol menor hasta la mayor y finalmente a re mayor , aparentemente entrando en su fase de decadencia, pero al mismo tiempo haciendo la transición al tema secundario líricamente cantable: el llamado período de canto. Este intervalo de caída en sucesión, que también desempeña un papel en el cuarto movimiento inacabado, forma parte integral del motivo principal del período de canto. Posteriormente, Bruckner compone una fase de transición prístina, que se repite estrechamente entre el segundo y el tercer grupo de temas.

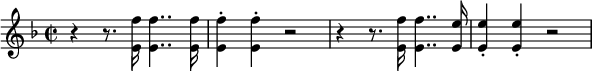

El segundo grupo temático cambia la música a La mayor y comienza en tono tranquilo. Esta sección se toca más lentamente que la primera y los violines llevan el tema inicial:

El tercer grupo temático regresa a re menor y tiene un lugar destacado en las trompas.

Al final de la transición hay una pausa en la nota fa, que se realiza sin fisuras. En términos formales, Bruckner amplía su camino sinfónico fusionando el desarrollo y la repetición posterior, en lugar de separarlos. [30]

"Estas dos partes [ejecución y recapitulación] se han convertido en la estructura interna, soldando la costura en un todo unificado. La implementación consiste en una ampliación del tema principal, pero sin cambiar la disposición del material del motivo en su división tripartita. Así, la primera parte del tema principal experimenta una repetición, no fiel al original, sino a la esencia interna. La repetición, sin embargo, se combina con el material del motivo de la segunda parte en la inversión como acompañamiento. La segunda parte también se amplía y, como en la exposición, conduce a la tercera parte y al clímax con el mismo aumento que en la exposición. [...] Este clímax también se amplía mediante una secuenciación repetida y creciente. Se evita la conclusión repentina de la exposición; se reemplaza por una breve interpretación del material del motivo de este clímax con un nuevo motivo para el acompañamiento independiente que determina el carácter de este pasaje".

— Anton Bruckner, Das Werk – Der Künstler – Die Zeit

La tendencia de Bruckner a reducir el desarrollo y la recapitulación de la forma sonata encuentra su máxima realización en este movimiento, cuya forma Robert Simpson describe como "Declaración, contradeclaración y coda". En el primer grupo temático se da una cantidad inusualmente grande de motivos, que se desarrollan de manera sustancial y rica en la repetición y en la coda. El tema principal del movimiento, interpretado por la orquesta completa, contiene una caída de octava que efectivamente sigue un ritmo de cuatro puntillos (una redonda unida a una blanca con tres puntillos).

Bruckner también cita material de sus obras anteriores: en un punto cerca de la coda, Bruckner cita un pasaje del primer movimiento de su Séptima Sinfonía . La página final del movimiento, además de los acordes tónicos (I) y dominantes (V) habituales, que se presentan en una explosión de quintas abiertas , utiliza un bemol napolitano ( ♭ II; la figura ascendente de Mi ♭ del compás 19) en una disonancia abrasiva con I y V.

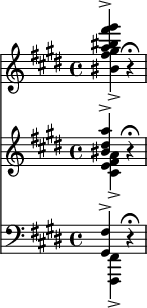

El Scherzo en re menor (3

4) comienza de forma inusual con un compás vacío. Después de esta pausa, los instrumentos de viento entonan un acorde de disonancia rítmica distintivo con los sonidos E, G ♯ , B ♭ y C ♯ . Este acorde se puede analizar de varias maneras. El musicólogo Wolfram Steineck da la siguiente explicación: "Si bien se puede escuchar sin duda el giro a Do sostenido menor, desde el principio también está relacionado dominantemente con Re menor, por lo que al menos es ambiguo. [...] Es la raíz dominante A, que se divide en sus dos semitonos circundantes (y tonos principales) y da al sonido su carácter subdominante característico, sin quitarle la dominante". [31] Por lo tanto, el fenómeno de la división de tonos también es significativo aquí. Mientras que la disociación de tonos en el primer movimiento afecta a la raíz de la tónica y ocurre relativamente tarde, en el Scherzo la nota A, ubicada en el centro de un acorde de sexta mayor de La dominante, se divide en sus tonos vecinos G ♯ y B ♭ ya al principio. El intervalo de este acorde es el sexto, que es temática y estructuralmente inmanente a la Novena Sinfonía. Bruckner escribió "E Fund[ament] Vorhalt auf Dom" en su boceto del 4 de enero de 1889; [32] por lo tanto, según Steinbeck, el acorde también tiene teóricamente como raíz el Mi, pero es una suspensión sobre la dominante (el acorde de La mayor) a una distancia de una quinta. [31] Sin embargo, este acorde característico también puede escucharse como un acorde de séptima disminuida en Do ♯ , séptimo grado de la escala menor armónica, en primera inversión y con Sol ♯ como su quinta elevada. En su resumen de las sinfonías de Bruckner, Philip Barford describió el estado de ánimo general del scherzo como "severo y tenso". [33]

Bruckner ha compuesto tres versiones sucesivas del Trío :

Los Tríos 1 y 2, que ya no se tocan, fueron estrenados por el Cuarteto Strub (1940). Una grabación de esta interpretación se conserva en el Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv . Grabaciones posteriores se han almacenado en el Archivo Bruckner. [38] Las tres versiones del Trío han sido publicadas por Cohrs. [39] Ricardo Luna ha grabado las tres versiones sucesivas del Trío en un arreglo propio para orquesta de cámara en 2013. [40] [41] El 2 de julio de 2022, Ricardo Luna interpretó una versión sinfónica de las tres versiones sucesivas del Trío con la Orquesta Sinfónica de Bolton. [42]

El Adagio de tres partes en mi mayor (4

4) "ha experimentado innumerables interpretaciones que buscan describir su estado de ánimo y, sin duda, experimentará estas mismas interpretaciones en el futuro". [43] Por ejemplo, Göllerich y Auer ven el comienzo "en el sombrío estado de ánimo del errante Parsifal (el preludio del Tercer Acto del Festival de la Dedicación de Richard Wagner)". [44] En términos de análisis compositivo, el fenómeno de la división del tono juega un papel integral en el comienzo de este movimiento.

Bruckner llamó a este movimiento su "Adiós a la vida". Comienza con una ambigüedad tonal y es el comienzo más problemático de cualquier Adagio de Bruckner, aunque logra una serenidad lírica y un asombro. El tema principal es un presagio del cromatismo del movimiento, que comienza con un salto ascendente de una novena menor y contiene los 12 tonos de la escala cromática:

El tono inicial B está dividido o difiere en sus dos notas vecinas C y A ♯ , por lo que el salto distintivo del intervalo de novena le da al comienzo del movimiento una carga sonora intensa. El posterior descenso cromático C, B, A ♯ conduce a un choque repentino de octavas, seguido de frases diatónicas verticales que terminan en un tono quejumbroso. Bruckner no compuso otro Adagio que planteara un movimiento melódico unánime sin acompañamiento alguno. [45] Los bocetos y borradores de Bruckner muestran que este comienzo no fue planeado. [46]

El resto de las cuerdas y las tubas wagnerianas se ponen en pleno tono en el tercer tiempo del segundo compás. Estas últimas se utilizan aquí por primera vez en la Novena Sinfonía, un método retardado que Bruckner ya había utilizado en su Séptima Sinfonía. Aquí, al comienzo de su canción de duelo por la muerte de Wagner, Bruckner pide que estos instrumentos entren, con su sonido redondo y oscuro, por primera vez. El Adagio de la Séptima comienza con un acompañamiento de acordes completo, a diferencia de la Novena. Mientras que en la Séptima, la tonalidad básica de do ♯ menor está establecida desde el principio, la tonalidad básica de mi mayor en la Novena se evita inicialmente por completo, y solo se recurre a ella después de un largo retraso.

La segunda parte del motivo, que llama la atención, muestra ecos del llamado amén de Dresde . Como afirma en principio Clemens Brinkmann: "Bajo la influencia de Mendelssohn y Wagner, Bruckner utilizó el 'amén de Dresde' en su música sacra y en sus obras sinfónicas". [47] El tercer motivo, melancólico, en pianissimo está marcado por los "cansados segundos de los contrabajos". [48] En un lamento, el primer oboe se balancea hacia arriba y se convierte en parte de una fase de secuencia que gira en espiral de manera constante, y finalmente conduce a la erupción del cuarto motivo: un llamado de trompeta pentatónico repetido en esta tonalidad [mi mayor] siete veces [en cada compás] sin ser modificado nunca " [49] se presenta en una cara de acorde sin rumbo tonal resultante de un quintillo múltiple. Michael Adensamer lo explica en detalle: "Uno podría interpretar al menos cuatro tonalidades de esta superposición (mi mayor, si mayor, do sostenido menor y fa sostenido menor) y aún así pasar el carácter de este sonido. Este carácter reside en la utilidad múltiple del sonido. Podría extenderse hacia arriba o hacia abajo hasta que cubriera los doce tonos. En este sentido es ilimitado, infinito y básicamente atonal..." [49] Sobre esta superficie sonora, los característicos abanicos de trompetas son literalmente escenificados y contrapunteados por un motivo de trompa que se despliega fatídicamente. Este motivo cita el comienzo expresivo de la frase mediante el uso del vacío ampliamente extendido. Los sonidos fluyen y refluyen en un coral de duelo por las trompas y las tubas de Wagner, que Auer y Göllerich, bautizaron en honor al "adiós a la vida" de Bruckner. [50] Ernst Décsey también destaca este pasaje de duelo, afirmando: "Bruckner llamó a este pasaje [marca de ensayo B ] cuando lo tocó para los dos Helms, que regresaron en 1894 de Berlín". [51]

Hacia el final del primer grupo temático, aparece un coral que desciende lentamente. Anton Bruckner cita este coral como el "Adiós a la vida". [52] [53] Interpretado por una trompa y las tubas de Wagner, está en si bemol menor (un tritono sobre la tónica general del movimiento, mi):

El comienzo del segundo grupo temático presenta un tema algo más melódico y lamentable en los violines:

Su segundo tema, una suave melodía vocal, cuya estructura a veces se "compara con los temas del Beethoven tardío", [43] sufre numerosas modificaciones y variaciones a medida que avanza. Inmediatamente antes de la reentrada del tema principal, la flauta solista desciende en un tríverso en do mayor sobre el pálido primer sonido de un acorde de séptima mayor de fa ♯ de quinta alterada de las tubas wagnerianas, para permanecer en el sonido de fa ♯ después de una caída final en tritono.

Tras un silencio, sigue la segunda parte del Adagio (a partir del compás 77), que se basa en gran medida en los componentes del tema principal. El material presentado es variado y desarrollado. El principio de la división de tonos también se manifiesta aquí, sobre todo en la voz opuesta de la flauta, que como nuevo elemento forma un claro contrapunto con el tema principal. Sólo ahora comienza el trabajo de implementación propiamente dicho, en el que el motivo principal del primer tema es llevado adelante por bajos que caminan orgullosamente. Después, el tono más suave del variado tema lírico vuelve a dominar. Después de una fase intermedia melancólica, surge una nueva ola creciente que conduce al clímax de la implementación. Una vez más, las trompetas hacen sonar su fanfarria ya familiar, que se detiene bruscamente. A continuación, sigue la parte central del tema vocal, que también termina abruptamente. Sólo el último final de la frase lo retoma el oboe y lo declara en el forte, que surge de la trompa en forma diminuta y del piano. Después de una pausa general, el movimiento se abre rápidamente. El crescendo, que se ha prolongado durante un largo período, se interrumpe abruptamente, seguido por una parte de pianissimo de sonido casi tímido de los instrumentos de viento de madera, que a su vez conduce a un episodio de tipo coral de cuerdas y metales. En opinión de Constantin Floros , hay dos pasajes en el Adagio, cada uno aparece solo una vez y no se "repite en el curso posterior de la composición. Esto se aplica una vez a la tuba [salida de la vida] en [marca de ensayo] B. [...] Esto se aplica al otro para el episodio de tipo coral, compases 155-162". [54] Este pasaje esféricamente transfigurado tiene su origen establecido estructuralmente en el coral de tuba, disminuyendo con el coral hasta el final.

La tercera parte del movimiento lento (a partir del compás 173) comienza con una reproducción figurativamente animada del segundo tema. Floros enfatiza que el Adagio de la Novena, así como el final, "deben considerarse en un contexto autobiográfico". [55] Bruckner compuso su Novena Sinfonía con la conciencia de su muerte inminente. En consecuencia, las autocitas existentes, como el Miserere de la Misa en re menor (a partir del compás 181), también pueden entenderse en el sentido de una connotación religiosa. En la tercera parte, los dos temas principales se superponen uno sobre otro y finalmente se fusionan; todo esto tiene lugar en el contexto de un enorme aumento de sonido. Bruckner crea un clímax, "como si buscara su poder expresivo monumental y su intensidad sin paralelo en la historia de la música". [56] La enorme acumulación de sonido experimenta una descarga agudamente disonante en forma de un acorde decimotercero que se extiende figurativamente en el compás 206. Luego Bruckner, tomando partes del primer tema y del Miserere, teje un canto del cisne reconciliador. Finalmente, el Adagio de la Novena termina, desvaneciéndose; Kurth habla de esto como un "proceso de disolución": [57] Mientras el órgano toca una nota Mi sostenida en el pedal, las tubas wagnerianas anuncian el motivo secundario del Adagio de la Octava Sinfonía mientras las trompas recuerdan el comienzo de la Séptima.

A lo largo de todo el movimiento, se retoman algunos de los estados de ánimo turbulentos de los movimientos anteriores. Una llamada del oboe –una cita del Kyrie de la Misa nº 3– introduce la repetición del primer tema, que se ve subrayada por dramáticas apelaciones al trombón. Poco después, Bruckner también cita, como una especie de súplica, el «Miserere nobis» del Gloria de su Misa en re menor . El siguiente clímax final, interpretado por toda la orquesta, concluye con un acorde extremadamente disonante, una decimotercera dominante :

A continuación, en la coda más serena hasta el momento, la música alude a la coda del Adagio de la Sinfonía n.º 8 y también hace alusión a la Sinfonía n.º 7. Estos compases de música concluyen la mayoría de las interpretaciones en directo y grabaciones de la sinfonía, aunque Bruckner había previsto que fueran seguidos por un cuarto movimiento.

Aunque se supone que Bruckner sugirió utilizar su Te Deum como finale de la Novena Sinfonía, ha habido varios intentos de completar la sinfonía con un cuarto movimiento basándose en los manuscritos supervivientes de Bruckner para el Finale. De hecho, la sugerencia de Bruckner se ha utilizado como justificación para completar el cuarto movimiento, ya que, además de la existencia de los fragmentos del Finale, demuestra (según estudiosos como John A. Phillips [58] ), que el compositor no quería que esta obra terminara con el Adagio .

En el material de este cuarto movimiento se han conservado diversas fases de la composición: desde simples bocetos de perfil hasta hojas de partitura más o menos preparadas, los llamados "bifolios". Un bifolio (en alemán: Bogen ) consiste en una hoja de papel doble (cuatro páginas). A veces, hay varios bifolios, que documentan los diferentes conceptos compositivos de Bruckner. La mayor parte de los manuscritos de Bruckner del último movimiento se puede encontrar en la Biblioteca Nacional de Austria en Viena. Otras obras se encuentran en la Biblioteca de Viena, en la biblioteca de la Universidad de Música y Artes Escénicas de Viena, en el Museo Histórico de la Ciudad de Viena y en la Biblioteca Jagiellonska de Cracovia.

El administrador de los bienes de Bruckner, Theodor Reisch, y los testigos del testamento, Ferdinand Löwe y Joseph Schalk, según el acta del 18 de octubre de 1896, dividieron los bienes; Joseph Schalk recibió el encargo de investigar la conexión entre los Fragmentos del Finale. El material pasó a manos de su hermano Franz en 1900; Ferdinand Löwe recibió más material. En 1911, Max Auer examinó el material superviviente del movimiento final, que había estado en posesión del antiguo alumno de Bruckner, Joseph Schalk. Refiriéndose a una hoja de bocetos, que ya no está disponible en la actualidad, Auer afirma: "Los bocetos... revelan un tema principal, un tema de fuga, un coral y el quinto tema del Te Deum ". [59] [ volumen necesario ] Además, Auer escribe: "Una vez estos temas incluso se elevaban uno sobre el otro, como en el final de la Octava ". [60] No es posible identificar a qué pasaje del final se refiere realmente.

While Bruckner's score designs and sketches can be arranged harmoniously, so that a logical musical sequence results, there are five gaps in this musical composition. For instance, the coda is missing. The original material was more extensive and some sheets were lost after Bruckner died. Bruckner's first biographer and secretary, August Göllerich (1859–1923), who was also the secretary of Franz Liszt, began a comprehensive Bruckner biography, which was completed after his death by the Bruckner researcher Max Auer (1880–1962).[61] The authors criticized the disarray in which Bruckner's papers were kept after his death:

It was an unforgivable mistake that an inventory of the estate was not included and an exact list can not be determined. After Dr. Heller's [Bruckner's attending physician] report the sheet music of the Master were laying around and parts of it were taken by qualified and unbidden people. It was even therefore not possible to find the chorale, which the Master had specially composed for Dr. Heller.[61]

The Australian musicologist John A. Phillips researched the different remaining fragments,[62] compiling a selection of the fragments for the Musikwissenschaftlichen Verlag Vienna.[63] In his opinion, the material he obtained is of Bruckner's carefully numbered "autograph score in the making". According to his research, in May 1896, the composition, in the primary stage of the score (strings added, sketches for wind instruments too) was written. In his opinion, half of the final bifolios have been lost to the score today. The course of most of the gaps can be restored from earlier versions and extensive Particell sketches. The surviving remains of the score break off shortly before the coda with the 32nd bifolio. According to Phillips, the sketches contain the progress of the coda to the last cadence. The corresponding sketch for the 36th bifolio still contains the first eight bars with a lying tone of D.

A facsimile edition of Bruckner's surviving final material has been published by Musikwissenschaftliche Verlag Vienna.[64] The largest part of the fragments can now also be viewed in the works database "Bruckner online".[65] Alfred Orel sequenced Bruckner's drafts and sketches of the Ninth Symphony in 1934, assuming that different versions still existed.[66]

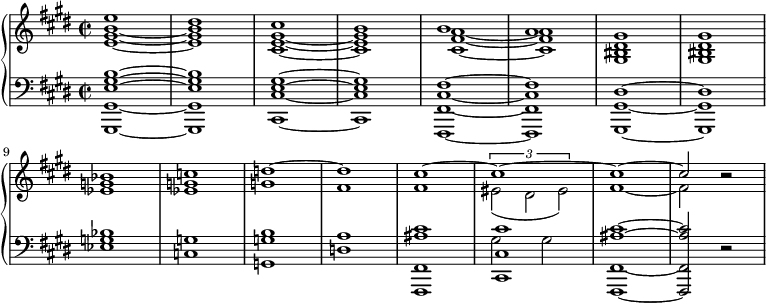

The movement, as left by Bruckner, features a "jagged" main theme with a double-dotted rhythm:

This insistent double-dotted rhythm pervades the movement. The second theme group begins with a variant of the main theme. The third theme group features a grand chorale, presented by the full brass. This chorale, a "resplendent resurrection"[67] of the "Farewell to Life" of the Adagio, descends in its first half with a similar mood as the Farewell to Life. In the second half the chorale ascends triumphantly:

The opening motif of the Te Deum appears before the development begins, played by the flute.[67] The brief development contains a bizarre passage with minor-ninth trumpet calls:[68]

A "wild fugue" begins the recapitulation, using a variant of the main theme as a subject:[69]

After the recapitulation of the chorale, a new "epilogue theme" is introduced. Harnoncourt suggested that it probably would have led to the coda.[69] After this cuts off, the only remaining extant music in Bruckner's hand is the previously mentioned initial crescendo and approach to the final cadence.

In 1934, parts of the final composition fragments in the piano version were edited by Else Krüger and performed by her and Kurt Bohnen, in Munich.

In 1940, Fritz Oeser created an orchestral installation for the Finale's exposition. This was performed on 12 October 1940 at the Leipzig Bruckner Festival in a concert of the Great Orchestra of the Reichssenders Leipzig with the conductor Hans Weisbach and transmitted by the radio.[70]

In 1974, Conductor Hans-Hubert Schönzeler played major parts of the Finale for BBC with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra.

In his essay, "Approaching a Torso" in 1976, the composer Peter Ruzicka published his research findings regarding the unfinished final movement of the Ninth Symphony.[71] Previously, he recorded parts of the finale with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra.

In 1986 Yoav Talmi with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra performed and recorded the whole symphony, including the finale fragments (Orel edition) as well as a movement completion by William Carragan using Bruckner's fragments. The set of 2 discs appeared on Chandos Records (CHAN 8468/9) and received the Grande Prix du Disque in Paris.

In 2002 Peter Hirsch recorded the finale fragments (Phillips edition) with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin.[72] In the same year during the Salzburger Festspiele, Nikolaus Harnoncourt made a workshop on the finale, during which he performed the retrieved fragments with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.[73]

In 2012, Sir Simon Rattle and the Berliner Philharmoniker published a recording of a four-movement version of the symphony, edited by a team led by Nicola Samale.[74]

Many (alleged) utterances by Bruckner concerning his Ninth Symphony have only survived indirectly. Bruckner, fearing that he would not be able to complete his composition, was supposed to have envisioned his Te Deum as the possible end of the symphony. When the conductor Hans Richter (1843–1916) visited Bruckner, he told him (translated from German):[75]

He [Hans Richter] had scheduled Bruckner's Seventh for a concert of the Philharmonic in autumn and now came to the Belvedere [Bruckner's last apartment was in the so-called Kustodenstöckl of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna] to tell it Bruckner. When Bruckner also communicated to him about his misery over the unfinished 4th movement of the Ninth, Richter gave him, as Meissner [Bruckner's close confidant and secretary] reports, the advice to complete the symphony, instead of a fourth movement with the Te Deum. The Master was very grateful for this suggestion, but he looked at it only as a last resort. As soon as he felt reasonably better, he sat down at the piano to work on the finale. He now seemed to think of a transition to the Te Deum and promised, as Meissner relates, a tremendous effect on the far-reaching main theme, blasted out by the brass choir, and on the familiar and original introductory bars of the Te Deum, as well as on the singers appearing there. He wanted, as he told Meissner a few times during audition, to shake, as it were, to the gates of eternity'.

— Anton Bruckner, Ein Lebens- und Schaffens-Bild

Auer continued, about a possible transition to the Te Deum, in the biography (translated from German):[75]

"The Master's student August Stradal and Altwirth assure that he had played for them a 'transition to the Tedeum', Stradal noted out of his memory. This transition music was to lead from E major to C major, the key of the Te Deum. Surrounded by the string figures of the Te Deum, there was a chorale that is not included in the Te Deum. Stradal's remark that the manuscript, that is in Schalk's hands, seems to indicate that it refers to the final bars of the finale score, which Bruckner has overwritten with 'Chorale 2nd Division'. [...] That Bruckner deliberately wanted to bring the Te Deum motif, proves the remark 'Te Deum thirteen bars before the entrance of the Te Deum figure'. As can be proved from the communication of the aforementioned informants, whose correctness can be proved by the hand of the manuscript, the master does not seem to have devised an independent transitional music from the Adagio to the Te Deum, but rather one from the point of reprise, where the coda begins."

— Anton Bruckner, Ein Lebens- und Schaffens-Bild

August Göllerich, Anton Meissner, August Stradal and Theodor Altwirth, who all knew Bruckner personally, reported in unison that Bruckner was no longer able to complete an instrumental finale: "Realizing that the completion of a purely instrumental final movement was impossible, he [Bruckner] attempted to establish an organic connection to the Te Deum, as proposed to him, to produce an emergency closure of the work, contrary to the tonal misgivings."[76] Bruckner, therefore, certainly had tonal misgivings about ending the D minor symphony in C major. Nevertheless, he conceded to the variant with the Te Deum as a final replacement, at least according to the testimony of various eyewitnesses.

Biographer Göllerich knew Bruckner and his environment personally. Subsequent biographers drew on Göllerich's work, so later generations' explanations and assumptions are sometimes considered less accurate than contemporary statements. Contemporary biography suggests Bruckner improvised the end of the symphony at the piano, without fixing the coda in definitive form and in writing. According to the physician's report Bruckner was unwilling to write the symphony in the main thoughts, because he was weak.[1][77] Bruckner died while working on an instrumental finale and powerful fugue.[78] In the fugue the last almost completely orchestrated score pages are traceable. Subsequent pages are not fully instrumented.[79]

The first attempt of a performing version of the Finale available on disc was by William Carragan (who has done arguably more important work editing Bruckner's Second Symphony) in 1983. This completion has been premiered by Moshe Atzmon, conducting the American Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in January 1984. The European premiere by the Utrecht Symfonie Orkest conducted by Hubert Soudant (Utrecht, April 1985), has been the first to be recorded (on LP). Shortly afterwards, this version has been recorded for CD release by Yoav Talmi and the Oslo Philharmonic. Talmi's recording also included the retrieved fragments Bruckner left (Orel edition), so that the listener may determine for himself how much of the realisation was speculation by the editor.

According to William Carragan, to make an own completion of the Finale, one should have three goals in mind: a faithful presentation of the fragments, an appropriate filling-out both horizontally and vertically, and a positive and triumphant ending.[86]Carragan uses both older and earlier bifolios. He bridges the gaps more freely by using sound formations and harmonic connections that are less typical for Bruckner than for later musical history (Mahler). He extends the coda by remaining at a constant fortissimo level for long periods and incorporating a variety of themes and allusions, including the chorale theme and the Te Deum.[87]

Indeed there can be no fully correct completion, just completions which avoid the most obvious errors, and there will always be debate on many points. But the finale, even as a fragmented and patched-together assemblage, still has a great deal to tell us about the authentic inspiration and lofty goals of Anton Bruckner, and it is a pity not to take every opportunity offered to become familiar with it and its profound meaning.[86]

The team of Nicola Samale and Giuseppe Mazzuca put together a new realisation from 1983 to 1985. The 1984 completion was recorded in 1986 by Eliahu Inbal and fits in with Inbal's recordings of early versions of Bruckner's symphonies. It was also included by Gennadi Rozhdestvensky in his recording of the different versions of Bruckner's symphonies. The coda of this realisation has more in common with the corresponding passage of the Eighth Symphony than it does with the later Samale, Mazzuca, Phillips and Cohrs realisation.

Samale revised the 1985 completion in 1988 with Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs and recorded it in the same year with the Katowice National Symphony Orchestra.[80]

After the 1988 revision of their completion, Samale and Mazzuca were joined by John A. Phillips and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs. A new completion (1992) proposed of one way to realise Bruckner's intention to combine themes from all four movements. This completion has been recorded by Kurt Eichhorn with the Bruckner Orchestra in Linz for the Camerata label. Phillips has also made a transition from the finale completion to the Te Deum. This transition, and its association with the finale and an example of the Te Deum are available the Bruckner Archive.[38]

A 1996 revision of this completion has been recorded in 1998 by Johannes Wildner with the Neue Philharmonie Westfalen for Naxos Records.

An intermediate 2001 revision has been performed in Gmunden on 8 October 2002 by Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs with the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra.[88]

A new, revised edition was published in 2005 by Nicola Samale and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs. Cohrs' latest research also made it possible to recover the musical content of one missing bifolio in the Fugue fully from the particello-sketch. This new edition, 665 bars long, makes use of 569 bars from Bruckner himself. This version has been recorded by Marcus Bosch with the Sinfonieorchester Aachen for the label Coviello Classics.

A revised reprint of this revision was performed by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Daniel Harding, Stockholm, in November 2007. This revision was published in 2008 and was then recorded by conductor Friedemann Layer with the Musikalische Akademie des Nationaltheater-Orchesters, Mannheim. Richard Lehnert explains the changes made for this version.[89]

A "final revision" was made in 2011, in particular including an entirely new conception of the coda.[90]The world premiere of this new ending was given by the Dutch Brabants Orkest under the baton of Friedemann Layer in Breda (NL), 15 October 2011. It was performed in Berlin on 9 February 2012 by Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic and can be watched on the Internet.[91] This version was released on EMI Classics on 22 May 2012.[92] Rattle conducted the American premiere at Carnegie Hall on 24 February 2012.[93] Simon Rattle conducted this version again with the Berlin Philharmonic on 26 May 2018.[94]

In September–October 2021 – in commemoration of the 125th anniversary of the composer’s death, John A. Phillips undertook an additional revision to it, substantive changes being confined to fugue and coda.[95] Cohrs, who had resigned from the Editorial Team in November 2021, was no more involved in this revision.[96] On 30 November 2022 this new revision of the Finale Completion was premiered by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Robin Ticciati.[97]

Nicola Samale and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs compare in their preface to the study score of the completed performance version of Samale-Phillips-Cohrs-Mazzuca (2008) the reconstruction of a musical work with methods of reconstruction of plastic surgery, forensic pathology, aetiology and fine art:

For this purpose, techniques of reconstruction are required that are not only legitimate in the natural sciences, but vital if one wishes to demonstrate certain processes. Unfortunately, in other fields such reconstruction techniques are accepted far more than in music: In medicine, victims of accidents are more than grateful for the possibility of replacing lost parts of their body by plastic surgery. In forensic pathology, such reconstructions are of value. This was demonstrated very effectively in 1977, when in the eponymous TV series Dr. Quincy reconstructed from a single femur not only the general appearance of the deceased but also that of his murderer (The Thigh Bone's Connected to the Knee Bone by Lou Shaw, also available as a novel by Thom Racina).

Reconstructions are also well known in the fine arts and archaeology. Paintings, torsi of sculptures, mosaics and fresco, shipwrecks, castles, theatres (Venice), Churches (Dresden), and even entire ancient villages have been successfully reconstructed.[98]

For the beginning of the final movement, the SMPC team of authors uses a bifolio in Bruckner's form in a shortened form. To fill in the gaps, the authors rely primarily on later bifolios and sketches of Bruckner, while earlier original material is sometimes disregarded. The authors believe that every gap has a certain number of bars. The gaps are added by the four editors according to the calculations they have made. For the coda, the authors use Bruckner's sequencing sketches, which are also processed by other authors, in a transposed form. The block effect of the final part is achieved mainly by the constant repetition of individual motifs. The authors also include various themes of the finale.[99]

In his finale edition, Nors S. Josephson makes various cyclical connections to the first and third movement of the symphony. Above all, he refers to a method that Bruckner uses in his Symphony No. 8. Josephson also uses Bruckner's sketched sequencing, which is believed to be part of the coda. In the coda. He refers to the themes of the exposition and avoids further development of the material.[100] Compared to the Adagio, the final movement gets less weight in his edition.[101] Josephson's completion by John Gibbons with the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra has been issued by Danacord: CD DADOCD 754, 2014.

Nors S. Josephson also aims for a reconstruction and states in the preface to his score edition, which is titled as Finale-Reconstruction:

The present edition of the finale to Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony is the result of a ten-year-long project. The editor utilized the scetches and score sctetches to this movement that are found in the Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna, Austria, the Viennese Stadt- und Landbibliothek and the Viennese Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst; all of these institutions kindly provided me with microfilms and photographic copies of these sources. In addition, Alfred Orel's 1934 edition of most of these sources as part of the Bruckner Complete Works was a particular value.[102]

In 2008 the Belgian organist and composer Sébastien Letocart realized a new completion of the Finale in 2007–08.[103][104][105] In the Coda he included quotations of themes from the Fifth, Seventh and Eighth Symphonies, the mid-subject of the Trio as a final Halleluja,[106] and at the end the combination of the four main themes from all four movements of the Ninth.[107]

Letocart's completion, together with the first three parts of the symphony, was recorded in 2008 by the French conductor Nicolas Couton with the MAV Symphony Orchestra of Budapest.[108] Sébastien Letocart states in the booklet text to the CD recording of his final version:

I want to make it quite clear that my completion of the finale of Bruckner's Ninth Symphony is based strictly on Bruckner's own material. This I have orchestrated as faithfully and discretely as possible. There are two main different aspects to understand the purpose of this completion... Firstly, besides having to fill in some of the orchestration of the existing parts, there are six gaps in the development/recapitulation that have to be speculatively reconstructed sometimes with the recreate of coherent links. My forthcoming thesis will give a bar-by-bar explanation of the musicological thinking and meaning behind my completion and additions as well as give details of the reconstruction phase. Secondly, my elaboration of the coda, however, shares neither the same task nor the same concern about the question "what would Bruckner have done" because it is quite simply impossible to know or to guess. We only have a few sketches of and some vague testimonies (Heller, Auer and Graf) about the Finale's continuation; we know nothing even about the precise number of bars, but all these hardly give any idea of the global structure Bruckner had in mind.[109]

During the closing concert of the Bruckner Casco Festival (13 to 15 September 2024) at the Muziekgebouw of Amsterdam, the Camerata RCO featured Anton Bruckner's 9th Symphony in a reduction for 16 musicians arranged by Sébastien Letocart specifically for this occasion.[110]

Gerd Schaller has composed his own completion of the Ninth, closely based on Bruckner's notes. He took into account all available draft materials as far back as the earliest sketches in order to close the remaining gaps in the score as much as possible. He used Bruckner's original manuscript documents, and ran the finale to 736 bars. Additionally, Schaller was able to supplement archival and manuscript material with missing elements in the score by drawing on his experience as a conductor, and applying Bruckner's compositional techniques to the recordings of the complete cycle of all the composer's eleven symphonies. The resulting composition, even the passages without continuous original material, are in a recognizably Brucknerian style.[111] Schaller also creates the broad, dramatically designed reprise of the main theme from Bruckner's earlier sketches. In the coda he quotes the opening theme of the first movement, thereby bridging the beginning of the symphony, a technique of quoting that Bruckner himself used in his symphonies (Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 5) and originating back to Beethoven. In the final part of the coda, Schaller renounces the quotations from other works by Bruckner in his newly published revised edition of 2018.[112]

Schaller first performed his version of the finale with the Philharmonie Festiva in the abbey church at Ebrach on 24 July 2016, as part of the Ebrach Summer Music Festival.[113] In March 2018 Schaller's revised version was published by Ries and Erler, Berlin, Score No 51487, ISMN M-013-51487-8. Schaller performed his revised version of the finale in the abbey church at Ebrach on 22 July 2018. This performance is issued on Profil CD PH18030. Gerd Schaller explains a reconstruction in itself as an impossible undertaking:

Before work could begin on the completion, though, a number of conceptual questions needed to be addressed... It soon became apparent that a "reconstruction", as such, would logically be infeasible, quite simply because it is impossible to reconstruct something that previously never existed in a finished form. And in any case, which version of the score should be reconstructed?... It is known that Bruckner frequently revised and amended his works, and he undoubtedly would have subjected the supposedly finished pages of the Ninth to numerous thorough reviews. It follows that there is no complete version that can be taken as a basis for reconstruction. In short, it seemed impossible for me to reconstruct a hypothetical musical masterpiece by such a genius as Anton Bruckner, and so I made it my aim to pursue historical accuracy by drawing on all the available fragments and thus supplement and complete the finale in the most authentic way possible and in keeping with Bruckner's late style. My top priority in this endeavour was to use, or at least consider, as much of Bruckner's original material as possible and thus avoid speculation as far as possible. The previously seldom perused, early sketches were another important source of essential Brucknerian ideas.[114]

Other attempts has been made by, among others, Jacques Roelands (2003, rev. 2014),[119] Kimiaki Tanaka (2020, rev. 2024)[120] and Martin Bernhard (2022).[121]

Free compositions incorporating material from the finale sketches were made by Peter-Jan Marthé (2006),[27][122] and a "Bruckner Dialog" by Gottfried von Einem (1971).[27]

Bruckner did not make many revisions of his Ninth Symphony. Multiple editions of his work and attempted completions of the symphony's unfinished fourth movement have been published.

This was the first published edition of the Ninth Symphony. It was also the version performed at the work's posthumous premiere, and the only version heard until 1932. Ferdinand Löwe made multiple unauthorized changes to the Symphony amounting to a wholesale re-composition of the work.[123] In addition to second-guessing Bruckner's orchestration, phrasing and dynamics, Löwe also dialed back Bruckner's more adventurous harmonies, such as the complete dominant thirteenth chord in the Adagio.[124]

This was the first edition to attempt to reproduce what Bruckner had actually written. It was first performed in 1932 by the Munich Philharmonic conducted by Siegmund von Hausegger, in the same program immediately following a performance of Löwe's edition. The edition was published, possibly with adjustments, two years later (1934) under the auspices of the Gesamtausgabe.

It is a re-edition of the Orel edition of 1934. The Nowak edition is the most commonly performed one today.

A new edition of the complete three movements was recorded by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Simon Rattle and Simone Young. It corrects several printing errors and includes extensive explanation of the editorial problems. The separate Critical Report of Cohrs contains numerous facsimiles from the first three movements. It includes an edition of the two earlier Trios for concert performance.[125]

Recordings of the completions of the fourth movement are usually coupled with the Nowak or Cohrs edition for the first three movements.[126]

A recording of the Orel or Nowak edition on average lasts about 65 minutes, though a fast conductor like Carl Schuricht can get it down to 56 minutes.

The oldest complete performance (of the three completed movements) preserved on record is by Otto Klemperer with the New York Philharmonic from 1934.

The first commercial recording was made by Siegmund von Hausegger with the Munich Philharmonic in 1938 for HMV. Both recordings used the Orel edition.

The apocryphal Löwe version is available on CD remasterings of LPs by Hans Knappertsbusch and F. Charles Adler. These can be as short as 51 minutes.

The earliest recordings of the Orel edition were Oswald Kabasta's live performance with the Munich Philharmonic in 1943 for the Music and Arts label, and Wilhelm Furtwängler's studio performance with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1944 (multiple labels).

After Bruno Walter's studio recording with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in 1959 for Sony/CBS, the Nowak edition was preferred.

The most recent Orel edition recording was Daniel Barenboim's live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1991 for Teldec.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Vienna Philharmonic recorded the Ninth (Cohrs edition) and the Finale fragment for BMG/RCA in 2003 – without the coda sketches.

In the CD "Bruckner unknown" (PR 91250, 2013) Ricardo Luna recorded the Scherzo, the three versions of the Trio (own edition) as well as the Finale fragment – with the coda sketches.[127]