.jpg/440px-Michael_Noonan_(crop).jpg)

Irlanda ha sido etiquetada como paraíso fiscal o paraíso fiscal corporativo en múltiples informes financieros, una acusación que el estado ha rechazado en respuesta. [a] [2] Irlanda está en todas las " listas de paraísos fiscales " académicas, incluidas las de § Líderes en investigación de paraísos fiscales y ONG fiscales . Irlanda no cumple con la definición de paraíso fiscal de la OCDE de 1998 , [3] pero ningún miembro de la OCDE, incluida Suiza, cumplió nunca con esta definición; solo Trinidad y Tobago la cumplió en 2017. [4] De manera similar, ningún país de la UE-28 se encuentra entre los 64 incluidos en la lista negra y la lista gris de paraísos fiscales de la UE de 2017. [5] En septiembre de 2016, Brasil se convirtió en el primer país del G20 en "poner en la lista negra" a Irlanda como paraíso fiscal. [6]

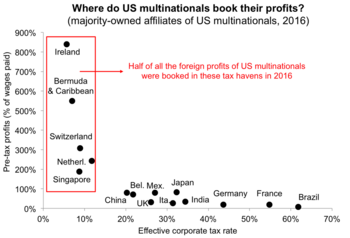

Las herramientas de erosión de la base imponible y traslado de beneficios (BEPS) de Irlanda otorgan a algunas corporaciones extranjeras § Tasas impositivas efectivas de 0% a 2,5% [b] sobre las ganancias globales redirigidas a Irlanda a través de su red de tratados impositivos. [c] [d] Las tasas impositivas efectivas agregadas de Irlanda para corporaciones extranjeras son de 2,2-4,5%. Las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda son los flujos BEPS más grandes del mundo, exceden todo el sistema del Caribe e inflan artificialmente el déficit comercial entre EE. UU. y la UE. [8] [9] Los regímenes QIAIF y L–QIAIF libres de impuestos de Irlanda , y los SPV de la Sección 110 , permiten a los inversores extranjeros evitar los impuestos irlandeses sobre los activos irlandeses, y pueden combinarse con las herramientas BEPS irlandesas para crear rutas confidenciales fuera del sistema impositivo corporativo irlandés . [e] Como estas estructuras están en la lista blanca de la OCDE, las leyes y regulaciones de Irlanda permiten el uso de disposiciones de protección y privacidad de datos, y exclusiones voluntarias de la presentación de cuentas públicas, para ocultar sus efectos. Hay pruebas discutibles de que Irlanda actúa como un Estado capturado, que fomenta estrategias fiscales. [11] [12]

La situación de Irlanda se atribuye a § Compromisos políticos derivados del histórico sistema de impuestos corporativos "mundial" de EE. UU., que ha convertido a las multinacionales estadounidenses en los mayores usuarios de paraísos fiscales y herramientas BEPS en el mundo. [f] La Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de EE. UU. de 2017 ("TCJA"), y el paso a un sistema impositivo "territorial" híbrido, [g] eliminaron la necesidad de algunos de estos compromisos. En 2018, las multinacionales del S&P 500 con gran peso en la propiedad intelectual guiaron tasas impositivas efectivas posteriores a la TCJA similares , ya sea que tengan su sede legal en EE. UU. (por ejemplo, Pfizer [h] ) o en Irlanda (por ejemplo , Medtronic [h] ). Si bien la TCJA neutralizó algunas herramientas BEPS irlandesas, mejoró otras (por ejemplo, la " CAIA " de Apple [i] ). [19] La dependencia de las corporaciones estadounidenses ( 80% del impuesto de sociedades irlandés, 25% de la mano de obra irlandesa, 25 de las 50 principales empresas irlandesas y 57% del valor agregado irlandés ) es un problema en Irlanda. [j]

La debilidad de Irlanda para atraer empresas de sistemas tributarios "territoriales" ( Tabla 1 ), [k] fue evidente en su fracaso para atraer empleos materiales de servicios financieros que se trasladaron debido al Brexit (por ejemplo, no hay bancos de inversión estadounidenses ni franquicias materiales de servicios financieros). La diversificación de Irlanda en herramientas de paraíso fiscal completo [l] (por ejemplo , QIAIF , L–QIAIF e ICAV ), ha visto a firmas de abogados tributarios y firmas de círculo mágico offshore establecer oficinas irlandesas para manejar la reestructuración fiscal impulsada por el Brexit. Estas herramientas hicieron de Irlanda el tercer OFC bancario en la sombra más grande del mundo , [24] y el quinto OFC de conducto más grande . [25] [26]

Irlanda ha estado asociada con el término "paraíso fiscal" desde que el IRS de los Estados Unidos elaboró una lista el 12 de enero de 1981. [m] [28] Irlanda ha sido un elemento constante en casi todas las listas de paraísos fiscales no gubernamentales desde Hines en febrero de 1994, [29] hasta Zucman en junio de 2018 [30] (y cada una de las intermedias). Sin embargo, Irlanda nunca ha sido considerada un paraíso fiscal ni por la OCDE ni por la Comisión Europea. [3] [5] Varios bandos utilizan estos dos hechos contrastantes para supuestamente probar o refutar que Irlanda es un paraíso fiscal, y se descarta gran parte de los detalles intermedios, algunos de los cuales pueden explicar la posición de la UE y la OCDE. Han surgido escenarios confusos, por ejemplo:

Las siguientes secciones describen en detalle la clasificación de Irlanda como paraíso fiscal ( fuentes y evidencias más citadas) y las refutaciones oficiales del Estado irlandés a la clasificación (tanto técnicas como no técnicas). La sección final describe la investigación académica sobre los factores que impulsan la toma de decisiones de los EE. UU., la UE y la OCDE con respecto a Irlanda.

Irlanda ha sido calificada de paraíso fiscal o paraíso fiscal corporativo (o Conduit OFC ) por:

Irlanda también ha sido etiquetada con términos relacionados como paraíso fiscal:

El término paraíso fiscal ha sido utilizado por los principales medios de comunicación irlandeses y por los principales comentaristas irlandeses. [89] [90] [91] [92] [68] [93] Los diputados electos irlandeses han planteado la pregunta: "¿Es Irlanda un paraíso fiscal?". [94] [95] Una búsqueda en los debates de la Dáil Éireann muestra 871 referencias al término. [96] Algunos partidos políticos irlandeses establecidos acusan al Estado irlandés de actividades de paraíso fiscal. [97] [98] [99]

En este momento, la comunidad internacional está preocupada por la naturaleza de los paraísos fiscales, y en particular Irlanda es vista con considerable sospecha por la comunidad internacional por hacer lo que se considera –por lo menos– dentro de los límites de las prácticas aceptables.

— Ashoka Mody , exjefe de la misión del FMI en Irlanda, "Ex funcionario del FMI advierte a Irlanda que se prepare para el fin del régimen fiscal", 21 de junio de 2018. [100]

Aunque Irlanda ha sido considerada un paraíso fiscal por muchos durante décadas, el sistema fiscal global del que depende Irlanda para incentivar a las corporaciones multinacionales a mudarse allí está siendo revisado por una coalición de 130 naciones. Esto provocaría cambios en la tasa impositiva corporativa oficial de Irlanda del 12,5%, y las reglas asociadas que a veces se describen como una ayuda para que las empresas con sede allí eviten pagar impuestos a otros países donde obtienen ganancias. [101] Originalmente, Irlanda fue uno de los pocos países (uno de nueve) que se opuso a firmar una reforma para una tasa impositiva corporativa mínima global del 15% y para obligar a las empresas de tecnología y minoristas a pagar impuestos en función de dónde se vendían sus bienes y servicios, en lugar de dónde estaba ubicada la empresa. El gobierno irlandés finalmente aceptaría los términos del acuerdo después de cierto debate. A partir del 7 de octubre de 2021, Irlanda abandonó su oposición a una revisión de las reglas impositivas corporativas globales renunciando a su tasa impositiva del 12,5%. [102] El Gabinete irlandés aprobó un aumento del 12,5% al 15% del impuesto de sociedades para las empresas con una facturación superior a 750 millones de euros. [103] Además, el Departamento de Finanzas irlandés ha estimado que la adhesión a este acuerdo global reduciría la recaudación fiscal del país en 2.000 millones de euros (2.300 millones de dólares) al año, según RTE. Los demás países que formaban parte de este acuerdo tuvieron que aceptar compromisos sobre algunas cuestiones clave relacionadas con la reforma, eliminando el “al menos” en la declaración “tasa mínima de impuesto de sociedades de al menos el 15%” y actualizándola a sólo el 15%, lo que indica que la tasa no se elevaría en una fecha posterior. Irlanda también recibió garantías de que podría mantener la tasa más baja para las empresas más pequeñas ubicadas en el país.

Irlanda figura en todas las " listas de paraísos fiscales " no políticas desde las primeras listas de 1994, [m] [28] y aparece en todas las " pruebas proxy " para paraísos fiscales y " medidas cuantitativas " de paraísos fiscales. El nivel de erosión de la base imponible y traslado de beneficios (BEPS) por parte de las multinacionales estadounidenses en Irlanda es tan grande, [8] que en 2017 el Banco Central de Irlanda abandonó el PIB/PNB como estadística para reemplazarlo por el ingreso nacional bruto modificado (INB*). [105] [106] Los economistas señalan que el PIB distorsionado de Irlanda ahora está distorsionando el PIB agregado de la UE, [107] y ha inflado artificialmente el déficit comercial entre la UE y los EE. UU. [108] (véase la Tabla 1 ).

Las herramientas BEPS basadas en la propiedad intelectual de Irlanda utilizan la " propiedad intelectual " ("PI") para "desplazar las ganancias" desde lugares con impuestos más altos, con los que Irlanda tiene tratados fiscales bilaterales , de vuelta a Irlanda. [d] Una vez en Irlanda, estas herramientas reducen los impuestos corporativos irlandeses al redireccionarlos, por ejemplo, a Bermudas con la herramienta BEPS irlandesa doble (por ejemplo, como hicieron Google y Facebook ), o a Malta con la herramienta BEPS de malta única (por ejemplo, como hicieron Microsoft y Allergan), o al cancelar los activos virtuales creados internamente contra el impuesto corporativo irlandés con la herramienta BEPS de desgravación de capital para activos intangibles ("CAIA") (por ejemplo, como hizo Apple después de 2015). Estas herramientas BEPS dan una tasa impositiva efectiva corporativa irlandesa (ETR) de 0-2,5%. Son las herramientas BEPS más grandes del mundo y superan los flujos agregados del sistema impositivo del Caribe. [8] [9] [43] [109] [110]

Irlanda ha recibido la mayor cantidad de inversiones fiscales corporativas de EE. UU. de cualquier jurisdicción global o paraíso fiscal desde la primera inversión fiscal de EE. UU. en 1983. [112]

Si bien las herramientas BEPS basadas en IP constituyen la mayoría de los flujos BEPS irlandeses, se desarrollaron a partir de la experiencia tradicional de Irlanda en fabricación por contrato entre grupos o herramientas BEPS basadas en precios de transferencia (PT) (por ejemplo, esquemas de deducción de capital, cobros transfronterizos entre grupos), que aún brindan empleo material en Irlanda (por ejemplo, de empresas de ciencias de la vida de EE. UU. [113] ). [111] [114] [115] Algunas corporaciones como Apple mantienen costosas operaciones BEPS basadas en PT de fabricación por contrato irlandesas (en comparación con opciones más baratas en Asia, como Foxconn de Apple ), para dar " sustancia " a sus herramientas BEPS basadas en IP más grandes de Irlanda. [116] [117]

Al negarse a implementar la Directiva de Contabilidad de la UE de 2013 (e invocar exenciones para informar sobre las estructuras de las sociedades holding hasta 2022), Irlanda permite que sus herramientas BEPS basadas en TP e IP se estructuren como "sociedades de responsabilidad ilimitada" ("ULC") que no tienen que presentar cuentas públicas ante la CRO irlandesa . [118] [119]

Las herramientas BEPS basadas en la deuda de Irlanda (por ejemplo, la SPV de la Sección 110 ), han convertido a Irlanda en el tercer mayor banco en la sombra del mundo , [24] [120] y han sido utilizadas por los bancos rusos para eludir las sanciones. [121] [122] [123] Las SPV irlandesas de la Sección 110 ofrecen " orfandad " para proteger la identidad del propietario y para protegerlo de los impuestos irlandeses (la SPV de la Sección 110 es una empresa irlandesa). Fueron utilizadas por los fondos de deuda en dificultades de los EE. UU. para evitar miles de millones en impuestos irlandeses, [124] [125] [126] con la ayuda de bufetes de abogados irlandeses especializados en derecho fiscal que utilizaron organizaciones benéficas para niños irlandesas internas para completar la estructura huérfana , [127] [128] [129] que permitió a los fondos de deuda en dificultades de los EE. UU. exportar las ganancias de sus activos irlandeses, libres de impuestos o aranceles irlandeses, a Luxemburgo y el Caribe (véase el abuso de la Sección 110 ). [130] [131]

A diferencia de las herramientas BEPS basadas en TP e IP, las SPV de la Sección 110 deben presentar cuentas públicas ante la CRO irlandesa , que fue como se descubrieron los abusos mencionados en 2016-17. En febrero de 2018, el Banco Central de Irlanda actualizó el régimen L-QIAIF, poco utilizado, para brindar los mismos beneficios fiscales que las SPV de la Sección 110, pero sin tener que presentar cuentas públicas. En junio de 2018, el Banco Central informó que 55 mil millones de euros de activos irlandeses en dificultades de propiedad estadounidense, equivalentes al 25% del PNB irlandés* , salieron de las SPV irlandesas de la Sección 110 y pasaron a las L-QIAIF. [132] [133] [134]

.jpg/440px-Pre-Tax_Profits_of_U.S._foreign_subsidiaries_(2015_BEA_Data).jpg)

La reestructuración irlandesa del primer trimestre de 2015 de Apple, posterior a la multa fiscal de la UE de 13.000 millones de euros correspondiente al período 2004-2014, es una de las herramientas BEPS más avanzadas del mundo que cumplen con las normas de la OCDE. Integra herramientas BEPS basadas en la propiedad intelectual irlandesas y herramientas BEPS basadas en la deuda de Jersey para amplificar materialmente los efectos de protección fiscal, por un factor de aproximadamente 2. [136] Apple Irlanda compró alrededor de 300.000 millones de dólares de un activo de propiedad intelectual "virtual" de Apple Jersey en el primer trimestre de 2015 (véase leprechaun economics ). [111] [137] La herramienta BEPS irlandesa de " asignaciones de capital para activos intangibles " ("CAIA") permite a Apple Irlanda amortizar este activo de propiedad intelectual virtual contra el futuro impuesto de sociedades irlandés. El aumento de 26.220 millones de euros en las asignaciones de capital intangible reclamadas en 2015, [138] mostró que Apple Irlanda está amortizando este activo de propiedad intelectual durante un período de 10 años. Además, Apple Jersey otorgó a Apple Ireland un préstamo "virtual" de 300 mil millones de dólares para comprar este activo de propiedad intelectual virtual de Apple Jersey. [136] Por lo tanto, Apple Ireland puede reclamar una reducción adicional del impuesto de sociedades irlandés sobre los intereses de este préstamo, que es de aproximadamente 20 mil millones de dólares por año (Apple Jersey no paga impuestos sobre los intereses del préstamo que recibe de Apple Ireland). Estas herramientas, creadas completamente a partir de activos internos virtuales financiados por préstamos internos virtuales, le dan a Apple aproximadamente 45 mil millones de euros por año en concepto de reducción del impuesto de sociedades irlandés. [137] En junio de 2018 se demostró que Microsoft se está preparando para copiar este plan de Apple, [139] conocido como "Green Jersey". [136] [137]

Como la propiedad intelectual es un activo interno virtual, se puede reponer con cada ciclo de producto tecnológico (o de ciencias biológicas) (por ejemplo, nuevos activos de propiedad intelectual virtuales creados en el extranjero y luego comprados por la filial irlandesa, con préstamos virtuales internos, a precios más altos). El Green Jersey ofrece así una herramienta BEPS perpetua, como el Double Irish , pero a una escala mucho mayor que el Double Irish , ya que el efecto BEPS completo se capitaliza desde el primer día.

Los expertos esperan que el régimen GILTI de la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de los EE. UU. de 2017 ("TCJA") neutralice algunas herramientas BEPS irlandesas, incluido el whisky de pura malta y el whisky doble irlandés . [140] Debido a que las desgravaciones de capital intangible irlandesas se aceptan como deducciones GILTI de los EE. UU., [141] el "Green Jersey" ahora permite a las multinacionales estadounidenses lograr tasas impositivas corporativas netas efectivas de los EE. UU. de 0% a 2,5% a través del alivio de la participación de la TCJA. [17] Como las principales herramientas BEPS irlandesas de Microsoft son el whisky de pura malta y el whisky doble irlandés , en junio de 2018, Microsoft estaba preparando un plan BEPS irlandés "Green Jersey". [139] Los expertos irlandeses, incluido Seamus Coffey , presidente del Consejo Asesor Fiscal Irlandés y autor de la Revisión del Código de Impuestos de Sociedades de Irlanda de 2017 del Estado irlandés , [142] [143] esperan un auge en la deslocalización de activos de propiedad intelectual internos virtuales de Estados Unidos a Irlanda, a través de la herramienta BEPS de Green Jersey (por ejemplo, en el marco del plan de desgravaciones de capital para activos intangibles). [144]

El régimen de Fondos de Inversión Alternativos para Inversores Cualificados ("QIAIF") de Irlanda es una gama de cinco envoltorios legales libres de impuestos ( ICAV , Sociedad de Inversión, Fideicomiso de Unidad, Fondo Contractual Común, Sociedad Limitada de Inversión). [145] [146] Cuatro de los cinco envoltorios no presentan cuentas públicas ante la CRO irlandesa y, por lo tanto, ofrecen confidencialidad y secreto fiscal. [147] [148] Si bien están regulados por el Banco Central de Irlanda , al igual que el SPV de la Sección 110, se ha demostrado que muchos son efectivamente entidades " de pantalla " no reguladas. [123] [149] [150] [151] [152] El Banco Central no tiene mandato para investigar la elusión o evasión fiscal, y según la Ley de Secreto Bancario Central de 1942 , el Banco Central de Irlanda no puede enviar la información confidencial que los QIAIF deben presentar ante el Banco a la Hacienda irlandesa . [153]

Los QIAIF se han utilizado para eludir impuestos sobre activos irlandeses, [154] [155] [156] [157] para eludir regulaciones internacionales, [158] para evitar leyes fiscales en la UE y los EE. UU. [159] [160] Los QIAIF se pueden combinar con herramientas corporativas BEPS irlandesas (por ejemplo, el Orphaned Super–QIF), para crear rutas fuera del sistema de impuestos corporativos irlandés a Luxemburgo, [10] el principal sumidero OFC para Irlanda. [161] [162] [163] Se afirma que una cantidad material de activos en los QIAIF irlandeses, y el envoltorio ICAV en particular, son activos irlandeses que están siendo protegidos de los impuestos irlandeses. [164] [165] Los bufetes de abogados especializados en círculos mágicos offshore (por ejemplo, Walkers y Maples y Calder , que han establecido oficinas en Irlanda), comercializan el ICAV irlandés como un envoltorio superior al SPC de las Islas Caimán ( Maples y Calder afirman ser uno de los principales arquitectos del ICAV), [166] [167] [168] y existen reglas QIAIF explícitas para ayudar con la redomiciliación de fondos de las Islas Caimán/BVI en ICAV irlandeses. [169]

Hay evidencia de que Irlanda cumple con los criterios de estado capturado para los paraísos fiscales. [11] [12] [150] [171] Cuando la UE investigó a Apple en Irlanda en 2016, encontraron resoluciones fiscales privadas de la Agencia Tributaria irlandesa que otorgaban a Apple una tasa impositiva del 0,005% sobre más de 110 mil millones de euros de ganancias irlandesas acumuladas entre 2004 y 2014. [ 172] [173] [174]

Cuando un eurodiputado irlandés alertó al ministro de Finanzas irlandés Michael Noonan en 2016 sobre una nueva herramienta BEPS irlandesa que reemplazaría al Double Irish (llamado Single Malt ), se le dijo que " se pusiera la camiseta verde ". [1] Cuando Apple ejecutó la mayor transacción BEPS de la historia en el primer trimestre de 2015, la Oficina Central de Estadísticas suprimió los datos para ocultar la identidad de Apple. [175] [176]

Noonan cambió las reglas del esquema de desgravación de capital para activos intangibles , la herramienta BEPS basada en IP que Apple utilizó en el primer trimestre de 2015, para reducir la tasa impositiva efectiva de Apple del 2,5% al 0%. [177] Cuando se descubrió en 2016 que los fondos de deuda en dificultades de EE. UU. abusaron de los SPV de la Sección 110 para proteger € 80 mil millones en saldos de préstamos irlandeses de los impuestos irlandeses, el Estado irlandés no investigó ni procesó (ver abuso de la Sección 110 ). En febrero de 2018, el Banco Central de Irlanda , que regula los SPV de la Sección 110, actualizó el poco utilizado régimen libre de impuestos L-QIAIF , que tiene una privacidad más fuerte del escrutinio público. [133] [178] En junio de 2018, los fondos de deuda en dificultades de EE. UU. transfirieron € 55 mil millones de activos irlandeses (o el 25% del PNB irlandés*), de los SPV de la Sección 110 a los L–QIAIF. [132] [133]

Setenta jurisdicciones firmaron la MLI Anti-BEPS de la OCDE de junio de 2017. [179] Los paraísos fiscales corporativos , incluida Irlanda, optaron por no aplicar el artículo 12 clave. [180]

En enero de 2017, el bufete internacional Baker McKenzie [ 181], que representa a una coalición de 24 empresas multinacionales de software estadounidenses, entre ellas Microsoft, presionó a Michael Noonan, como ministro de finanzas [irlandés], para que se resistiera a las propuestas [de la OCDE sobre el impuesto sobre sociedades]. En una carta dirigida a él, el grupo recomendó a Irlanda que no adoptara el artículo 12, ya que los cambios "tendrán efectos que durarán décadas" y podrían "obstaculizar la inversión y el crecimiento globales debido a la incertidumbre en torno a los impuestos". La carta decía que "mantener el estándar actual hará de Irlanda un lugar más atractivo para una sede regional al reducir el nivel de incertidumbre en la relación fiscal con los socios comerciales de Irlanda".

— Irish Times . “Irlanda se resiste a cerrar la ‘laguna’ del impuesto de sociedades”, 10 de noviembre de 2017. [180]

-_ALONG_BOTANIC_AVENUE_(JANUARY_2018)-135337_(39605114602).jpg/440px-THE_CENTRAL_BANK_OF_IRELAND_(NEW_HEADQUARTER_BUILDING_ON_NORTH_WALL_QUAY)-_ALONG_BOTANIC_AVENUE_(JANUARY_2018)-135337_(39605114602).jpg)

El investigador de paraísos fiscales Nicholas Shaxson documentó cómo el estado capturado de Irlanda utiliza una red compleja y "compartida" de leyes irlandesas de privacidad y protección de datos para sortear el hecho de que sus herramientas fiscales están en la lista blanca de la OCDE, [182] [183] y por lo tanto deben ser transparentes para alguna entidad estatal. [11] Por ejemplo, los QIAIF irlandeses libres de impuestos (y los L-QIAIF) están regulados por el Banco Central de Irlanda y deben proporcionar al Banco detalles de sus finanzas. Sin embargo, la Ley de Secreto del Banco Central de 1942 impide que el Banco Central envíe estos datos a los Comisionados de Ingresos . [153] De manera similar, la Oficina Central de Estadísticas (Irlanda) declaró que tuvo que restringir su publicación de datos públicos en 2016-17 para proteger la identidad de Apple durante su acción BEPS de 2015, porque la Ley Central de Estadísticas de 1993 prohíbe el uso de datos económicos para revelar tales actividades. [184] Cuando la Comisión Europea multó a Apple con 13.000 millones de euros por ayuda estatal ilegal en 2016 , no existían registros oficiales de ninguna discusión sobre el acuerdo fiscal otorgado a Apple fuera de la Oficina de Ingresos de Irlanda , ya que dichos datos también están protegidos. [185]

Cuando Tim Cook afirmó en 2016 que Apple era el mayor contribuyente de Irlanda, los Comisionados de Ingresos Irlandeses citaron la Sección 815A de la Ley Tributaria de 1997 que les impide revelar dicha información, incluso a los miembros del Dáil Éireann , o el Departamento de Finanzas irlandés (a pesar del hecho de que Apple representa aproximadamente una quinta parte del PIB de Irlanda). [186]

Los comentaristas destacan la plausible posibilidad de negación que ofrecen las leyes irlandesas de privacidad y protección de datos, que permiten al Estado funcionar como un paraíso fiscal manteniendo al mismo tiempo el cumplimiento de la OCDE. Garantizan que la entidad estatal que regula cada herramienta fiscal esté "aislada" de la Hacienda irlandesa y del escrutinio público a través de las leyes de acceso a la información . [11] [187] [188]

En febrero de 2019, The Guardian informó sobre informes internos filtrados de Facebook que revelaban la influencia que tenía Facebook en el Estado irlandés, a lo que el académico de la Universidad de Cambridge John Naughton afirmó: "la filtración fue "explosiva" en la forma en que reveló el "vasallaje" del estado irlandés a las grandes empresas tecnológicas". [189] En abril de 2019, Politico informó sobre las preocupaciones de que Irlanda estaba protegiendo a Facebook y Google de las nuevas regulaciones GDPR de la UE , afirmando: "A pesar de sus promesas de reforzar su gastado aparato regulador, Irlanda tiene una larga historia de complacer a las mismas empresas que se supone que debe supervisar, habiendo cortejado a las principales empresas de Silicon Valley a la Isla Esmeralda con promesas de impuestos bajos, acceso abierto a altos funcionarios y ayuda para asegurar fondos para construir nuevas y relucientes sedes". [190]

Las multinacionales estadounidenses desempeñan un papel sustancial en la economía de Irlanda, atraídas por las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda , que protegen sus ganancias no estadounidenses del sistema de impuestos corporativos "mundial" histórico de Estados Unidos. En cambio, las multinacionales de países con sistemas impositivos "territoriales", con mucho el sistema impositivo corporativo más común en el mundo, no necesitan utilizar paraísos fiscales corporativos como Irlanda, ya que sus ingresos extranjeros están gravados a tasas mucho más bajas. [192]

Por ejemplo, en 2016-2017, las multinacionales controladas por Estados Unidos en Irlanda:

De la tabla anterior:

El Estado irlandés rechaza las etiquetas de paraíso fiscal como una crítica injusta a su baja, pero legítima, tasa impositiva corporativa irlandesa del 12,5%, [201] [202] que defiende como la tasa impositiva efectiva ("ETR"). [203] Estudios independientes muestran que la tasa impositiva corporativa efectiva agregada de Irlanda se encuentra entre el 2,2% y el 4,5% (dependiendo de los supuestos realizados). [204] [109] [205] [206] Esta tasa impositiva efectiva agregada más baja es coherente con las tasas impositivas efectivas individuales de las multinacionales estadounidenses en Irlanda (las multinacionales controladas por los EE. UU. son 14 de las 20 empresas más grandes de Irlanda, y Apple por sí sola representa más de una quinta parte del PIB irlandés; véase " economía de bajos impuestos "), [50] [207] [208] [209] [210] así como las herramientas BEPS basadas en IP comercializadas abiertamente por las principales firmas de abogados tributarios en el Centro de Servicios Financieros Internacionales de Irlanda con ETR de 0-2,5% (véase " tasa impositiva efectiva "). [211] [212] [213]

.jpg/440px-Conversation_with_Margrethe_Vestager,_European_Commissioner_for_Competition_(17222242662).jpg)

Dos de los principales líderes mundiales en investigación sobre paraísos fiscales estimaron que la tasa impositiva corporativa efectiva de Irlanda era del 4 %: James R. Hines Jr., en su artículo Hines-Rice de 1994 sobre paraísos fiscales, estimó que la tasa impositiva corporativa efectiva de Irlanda era del 4 % (Apéndice 4); [29] Gabriel Zucman , 24 años después, en su artículo de junio de 2018 sobre paraísos fiscales corporativos, también estimó que el impuesto corporativo efectivo de Irlanda era del 4 % (Apéndice 1). [109]

La diferencia entre el ETR del 12,5% que afirman el Estado irlandés y sus asesores y el ETR real del 2,2% al 4,5% calculado por expertos independientes se debe a que el código fiscal irlandés considera que un alto porcentaje de los ingresos irlandeses no están sujetos a impuestos irlandeses, debido a diversas exclusiones y deducciones. La diferencia del 12,5% frente al 2,2% al 4,5% implica que más de dos tercios de los beneficios corporativos contabilizados en Irlanda están excluidos del impuesto corporativo irlandés (véase el ETR irlandés ).

Este tratamiento selectivo permitió a Apple pagar una tasa impositiva corporativa efectiva del 1 por ciento sobre sus ganancias europeas en 2003, hasta el 0,005 por ciento en 2014.

— Margrethe Vestager , " Ayuda estatal (SA.38373): Irlanda concedió beneficios fiscales ilegales a Apple por un valor de hasta 13.000 millones de euros " (30 de agosto de 2016) [214]

Aplicar una tasa del 12,5% en un código tributario que protege la mayoría de las ganancias corporativas de impuestos es indistinguible de aplicar una tasa cercana al 0% en un código tributario normal.

— Jonathan Weil , Bloomberg View (11 de febrero de 2014) [63]

El Estado irlandés no hace referencia a los QIAIF (o L–QIAIF), ni a los SPV de la Sección 110, que permiten a los inversores no residentes mantener activos irlandeses indefinidamente sin incurrir en impuestos, IVA o aranceles irlandeses (por ejemplo, "erosión de la base imponible" permanente para el fisco irlandés, ya que las unidades QIAIF y las acciones de los SPV pueden comercializarse), y que pueden combinarse con las herramientas BEPS irlandesas para evitar todos los impuestos corporativos irlandeses (véase § Herramientas fiscales nacionales).

Los impuestos sobre el salario, el IVA y el impuesto sobre las ganancias de capital para los residentes irlandeses están en línea con las tasas de otros países de la UE-28 y tienden a ser ligeramente más altos que los promedios de la UE-28 en muchos casos. Debido a esto, Irlanda tiene un plan especial de tasas de impuestos sobre el salario más bajas y otras bonificaciones fiscales para los empleados de multinacionales extranjeras que ganan más de 75.000 euros ("SARP"). [215]

La pirámide de la "Jerarquía de impuestos" de la OCDE (del documento de política fiscal de 2011 del Grupo de Estrategia Fiscal del Departamento de Finanzas ) resume la estrategia fiscal de Irlanda. [216]

Estudios realizados en la UE y los EE.UU. que intentaron encontrar un consenso sobre la definición de paraíso fiscal concluyeron que no existe consenso (ver definiciones de paraíso fiscal ). [217]

El Estado irlandés y sus asesores han refutado la etiqueta de paraíso fiscal invocando la definición de la OCED de 1998 de "paraíso fiscal" como definición de consenso: [218] [219] [220] [221]

La mayoría de las herramientas BEPS y QIAIF irlandesas están en la lista blanca de la OCDE (y, por lo tanto, pueden acogerse a los 70 tratados fiscales bilaterales de Irlanda ), [182] [183] y, por lo tanto, si bien Irlanda podría cumplir con la primera prueba de la OCDE, no pasa la segunda y la tercera pruebas de la OCDE. [3] La cuarta prueba de la OCDE (‡) fue retirada por la OCDE en 2002 tras la protesta de los EE. UU., lo que indica que hay una dimensión política en la definición. [31] [222] En 2017, solo una jurisdicción, Trinidad y Tobago, cumplió con la definición de paraíso fiscal de la OCDE de 1998 (Trinidad y Tobago no es uno de los 35 países miembros de la OCDE ), y la definición ha caído en descrédito. [4] [223] [224]

El académico James R. Hines Jr., especialista en paraísos fiscales, señala que las listas de paraísos fiscales de la OCDE nunca incluyen a los 35 países miembros de la OCDE (Irlanda es un miembro fundador de la OCDE). [39] La definición de la OCDE se elaboró en 1998 como parte de la investigación de la OCDE sobre Competencia fiscal perjudicial: un problema mundial emergente . [225] En 2000, cuando la OCDE publicó su primera lista de 35 paraísos fiscales, [226] no incluía a ningún país miembro de la OCDE, ya que ahora se consideraba que todos habían participado en el Foro Global de la OCDE sobre Transparencia e Intercambio de Información con Fines Fiscales (véase § Enlaces externos). Debido a que la OCDE nunca ha incluido a ninguno de sus 35 miembros como paraísos fiscales, a Irlanda, Luxemburgo, los Países Bajos y Suiza a veces se los denomina "paraísos fiscales de la OCDE". [86]

Las definiciones subsiguientes de paraíso fiscal y/o centro financiero extraterritorial / paraíso fiscal corporativo (véase la definición de "paraíso fiscal" ) se centran en los impuestos efectivos como requisito principal, que Irlanda cumpliría, y han entrado en el léxico general. [227] [ 228] [229] La Red de Justicia Fiscal , que coloca a Irlanda en su lista de paraísos fiscales, [31] separó el concepto de tasas impositivas de la transparencia fiscal al definir una jurisdicción de secreto y crear el Índice de Secreto Financiero . La OCDE nunca ha actualizado ni modificado su definición de 1998 (aparte de eliminar el cuarto criterio). La Red de Justicia Fiscal implica que Estados Unidos puede ser la razón. [230]

Si bien en 2017 la OCDE solo consideraba a Trinidad y Tobago como paraíso fiscal, [3] en 2017 la UE elaboró una lista de 17 paraísos fiscales, además de otras 47 jurisdicciones en la "lista gris", [231] sin embargo, al igual que con las listas de la OCDE anteriores, la lista de la UE no incluyó ninguna jurisdicción de la UE-28. [232] Solo uno de los 17 paraísos fiscales de la UE incluidos en la lista negra, a saber, Samoa, apareció en la lista de los 20 principales paraísos fiscales de julio de 2017 de CORPNET.

La Comisión Europea fue criticada por no incluir a Irlanda, Luxemburgo, los Países Bajos, Malta y Chipre, [233] [234] y Pierre Moscovici , declaró explícitamente ante un Comité de Finanzas del Oireachtas estatal irlandés el 24 de enero de 2017: Irlanda no es un paraíso fiscal , [5] aunque posteriormente llamó a Irlanda y los Países Bajos "agujeros negros fiscales" el 18 de enero de 2018. [27] [235]

El 27 de marzo de 2019, RTÉ News informó que el Parlamento Europeo había "aceptado por abrumadora mayoría" un nuevo informe que comparaba a Irlanda con un paraíso fiscal. [236]

El primer gran § Líderes en la investigación de paraísos fiscales fue James R. Hines Jr. , quien en 1994, publicó un artículo con Eric M Rice, enumerando 41 paraísos fiscales, de los cuales Irlanda era uno de sus 7 principales paraísos fiscales . [29] El artículo de Hines-Rice de 1994 es reconocido como el primer artículo importante sobre paraísos fiscales, [36] y es el artículo más citado en la historia de la investigación sobre paraísos fiscales. [37] El artículo ha sido citado por todos los artículos de investigación posteriores, más citados , sobre paraísos fiscales, por otros § Líderes en la investigación de paraísos fiscales, incluyendo Desai , [237] Dharmapala , [41] Slemrod , [44] y Zucman . [30] [238] Hines amplió su lista original de 1994 a 45 países en 2007, [38] y a 52 países en la lista de Hines de 2010 , [39] y utilizó técnicas cuantitativas para estimar que Irlanda era el tercer paraíso fiscal más grande del mundo. Otros documentos importantes sobre paraísos fiscales de Dharmapala (2008, 2009), [41] y Zucman (2015, 2018), [30] citan el documento de Hines-Rice de 1994, pero crean sus propias listas de paraísos fiscales, todas las cuales incluyen a Irlanda (por ejemplo, la lista de junio de 2018, Zucman–Tørsløv–Wier 2018 ).

El documento Hines-Rice de 1994 fue uno de los primeros en utilizar el término " traslado de beneficios " . [239] Hines-Rice también introdujo las primeras pruebas cuantitativas de un paraíso fiscal, que Hines consideró necesarias ya que muchos paraísos fiscales tenían tasas impositivas "generales" no triviales. [240] Estas dos pruebas siguen siendo las pruebas indirectas más citadas para los paraísos fiscales en la literatura académica. La primera prueba, la distorsión extrema de las cuentas nacionales por los flujos contables BEPS , fue utilizada por el FMI en junio de 2000 al definir los centros financieros extraterritoriales ("OFC"), un término que el FMI utilizó para abarcar tanto los paraísos fiscales tradicionales como los paraísos fiscales corporativos modernos emergentes : [31] [32] [33] [34]

El documento de Hines-Rice mostró que las bajas tasas impositivas extranjeras [de los paraísos fiscales] en última instancia mejoran las recaudaciones impositivas de los EE. UU . [243] La idea de Hines de que EE. UU. es el mayor beneficiario de los paraísos fiscales fue confirmada por otros, [15] y dictó la política estadounidense hacia los paraísos fiscales, incluidas las reglas de " marcar la casilla " [o] de 1996 , y la hostilidad de EE. UU. a los intentos de la OCDE de frenar las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda. [p] [222] Bajo la TCJA estadounidense de 2017, las multinacionales estadounidenses pagaron un impuesto de repatriación del 15,5% sobre el billón de dólares aproximadamente en efectivo no gravado acumulado en paraísos fiscales globales entre 2004 y 2017. [q] Si estas multinacionales estadounidenses hubieran pagado impuestos extranjeros, habrían acumulado suficientes créditos fiscales extranjeros para evitar pagar impuestos estadounidenses. Al permitir que las multinacionales estadounidenses utilicen paraísos fiscales globales, el fisco norteamericano recibió más impuestos, a expensas de otros países, como predijo Hines en 1994.

Varios de los documentos de Hines sobre los paraísos fiscales, incluidos los cálculos del documento Hines-Rice de 1994, se utilizaron en el informe final del Consejo de Asesores Económicos del Presidente de los Estados Unidos que justificó la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de 2017, la mayor reforma fiscal estadounidense en una generación. [244]

El Estado irlandés rechaza los estudios académicos que enumeran a Irlanda como paraíso fiscal por considerarlos "obsoletos", porque citan el documento Hines-Rice de 1994. [245] [246] El Estado irlandés ignora el hecho de que tanto Hines como todos los demás académicos desarrollaron nuevas listas; o que el documento Hines-Rice de 1994 todavía se considera correcto (por ejemplo, según la legislación TCJA de EE. UU. de 2017). [244] En 2013, el Departamento de Finanzas (Irlanda) coescribió un documento con los Comisionados de Ingresos Irlandeses , que habían publicado en el ESRI Quarterly patrocinado por el Estado , que encontró que las únicas fuentes que enumeraban a Irlanda como paraíso fiscal eran: [219] [r]

Este documento escrito por el Estado irlandés en 2013 invocó entonces la definición de paraíso fiscal de la OCDE de 1998, cuatro años más reciente que la de Hines–Rice y desde entonces desacreditada, para demostrar que Irlanda no era un paraíso fiscal. [219]

Lo que sigue es un artículo del Irish Independent de junio de 2018 escrito por el director ejecutivo del organismo comercial clave que representa a todas las multinacionales estadounidenses en Irlanda sobre el documento Hines-Rice de 1994:

Sin embargo, parece que la narrativa de los "paraísos fiscales" siempre estará con nosotros, y normalmente esa narrativa se basa en estudios y datos de hace 20 o 30 años o incluso más. Es un poco como acusar a Irlanda hoy de ser homofóbica porque hasta 1993 las relaciones homosexuales estaban criminalizadas e ignorar el feliz día de mayo de 2015 en que Irlanda se convirtió en el primer país del mundo en introducir la igualdad matrimonial por votación popular.

— Mark Redmond, presidente de la Cámara de Comercio Estadounidense en Irlanda, 21 de junio de 2018 [199] [247]

De una manera menos técnica que las refutaciones del Estado irlandés, las etiquetas también han provocado respuestas de los líderes de la comunidad empresarial irlandesa que atribuyen el valor de la inversión estadounidense en Irlanda a la base de talento única del país. Con 334 mil millones de euros, el valor de la inversión estadounidense en Irlanda es mayor que el PIB de Irlanda de 2016 de 291 mil millones de euros (o el INB* de 2016 de 190 mil millones de euros), y mayor que la inversión estadounidense agregada total en todos los países BRIC. [199] Esta base de talento única también es mencionada por IDA Ireland , el organismo estatal responsable de atraer inversión extranjera, pero nunca se define más allá del concepto amplio. [250]

La educación irlandesa no parece ser distintiva. [251] Irlanda tiene un alto porcentaje de graduados de nivel terciario, pero esto se debe a que reclasificó muchos colegios técnicos como instituciones que otorgan títulos en 2005-08. Se cree que esto contribuyó al declive de sus principales universidades, de las cuales hay dos entre las 200 mejores (es decir, un problema de calidad sobre cantidad). [248] [252] [253] Irlanda continúa aplicando esta estrategia y está considerando reclasificar los institutos técnicos irlandeses restantes como universidades para 2019. [254]

Irlanda no muestra ninguna distinción aparente en ninguna métrica no relacionada con los impuestos de competitividad empresarial, incluidos el costo de vida, [255] [256] [257] las tablas de clasificación de los lugares preferidos para la IED de la UE, [258] las tablas de clasificación de los destinos preferidos de la UE para las entidades financieras con sede en Londres después del Brexit (que están vinculadas a la calidad del talento), [259] y las clasificaciones clave del Informe de Competitividad Global del Foro Económico Mundial . [260]

Sin su régimen de bajos impuestos, Irlanda tendrá dificultades para mantener el impulso económico

— Ashoka Mody , exjefe de la misión del FMI en Irlanda, "Advertencia: Irlanda se enfrenta a una amenaza económica por la dependencia fiscal corporativa – Jefe de la troika", 9 de junio de 2018. [261]

Los comentaristas irlandeses ofrecen una perspectiva sobre la "base de talento" de Irlanda. El Estado aplica un " impuesto al empleo " a las multinacionales estadounidenses que utilizan herramientas de BEPS irlandesas. Para cumplir con sus cuotas de empleo irlandesas, algunas empresas tecnológicas estadounidenses realizan funciones de localización de bajo nivel en Irlanda que requieren empleados extranjeros que hablen idiomas globales (mientras que muchas multinacionales estadounidenses realizan funciones de ingeniería de software de mayor valor en Irlanda, algunas no lo hacen [117] [265] ). Estos empleados deben ser contratados internacionalmente. Esto se facilita a través de un programa de visas de trabajo irlandés flexible. [266] Este requisito de " impuesto al empleo " irlandés para el uso de herramientas BEPS, y su cumplimiento a través de visas de trabajo extranjeras, es un factor impulsor de la crisis de la vivienda en Dublín. [267] Esto es coherente con un sesgo hacia el crecimiento económico impulsado por el desarrollo inmobiliario, favorecido por los principales partidos políticos irlandeses (véase Abuso de QIAIF ). [268]

En otra refutación menos técnica, el Estado explica la alta clasificación de Irlanda en las " pruebas proxy " establecidas para los paraísos fiscales como un subproducto de la posición de Irlanda como centro preferido para las multinacionales globales de la "economía del conocimiento" (por ejemplo, tecnología y ciencias de la vida), "que venden en los mercados de la UE-28". [269] Cuando la Oficina Central de Estadísticas (Irlanda) suprimió su publicación de datos de 2016-2017 para proteger la acción BEPS del primer trimestre de 2015 de Apple, publicó un documento sobre "cómo afrontar los desafíos de una economía del conocimiento globalizada moderna". [270]

Irlanda no tiene corporaciones extranjeras que no sean estadounidenses o británicas entre sus 50 principales empresas por ingresos, y solo una por empleados ( Lidl , de Alemania , que vende en Irlanda). [20] Las multinacionales británicas en Irlanda están vendiendo en Irlanda (por ejemplo, Tesco) o datan de antes de 2009, después de lo cual el Reino Unido revisó su sistema impositivo a un modelo de "impuesto territorial". Desde 2009, el Reino Unido se ha convertido en un importante paraíso fiscal (véase la transformación del Reino Unido ). [21] [22] Desde esta transformación, ninguna firma importante del Reino Unido se ha mudado a Irlanda y la mayoría de las inversiones de impuestos corporativos del Reino Unido a Irlanda regresaron; [23] aunque Irlanda ha logrado atraer algunas firmas de servicios financieros afectadas por el Brexit . [271] [272]

En 2016, el experto estadounidense en impuestos corporativos, James R. Hines Jr. , demostró que las multinacionales de sistemas de impuestos corporativos "territoriales" no necesitan paraísos fiscales, al investigar los comportamientos de las multinacionales alemanas con expertos académicos alemanes en impuestos. [273]

Las multinacionales controladas por los EE. UU. constituyen 25 de las 50 principales empresas irlandesas (incluyendo inversiones fiscales ) y el 70% de los ingresos de las 50 principales (véase la Tabla 1 ). Las multinacionales controladas por los EE. UU. pagan el 80% de los impuestos corporativos irlandeses (véase " economía de impuestos bajos "). Las multinacionales estadounidenses con sede en Irlanda pueden estar vendiendo en Europa, sin embargo, la evidencia es que dirigen todos los negocios no estadounidenses a través de Irlanda. [c] [277] [278] Irlanda se describe con mayor precisión como un "paraíso fiscal corporativo estadounidense". [279] Las multinacionales estadounidenses en Irlanda son de "industrias del conocimiento" (véase la Tabla 1 ). Esto se debe a que las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda (por ejemplo, el double Irish , el whisky de malta simple y las desgravaciones de capital para activos intangibles ) requieren propiedad intelectual ("PI") para ejecutar las acciones BEPS, que la tecnología y las ciencias de la vida poseen en cantidad (véase IP–Based BEPS tools ). [280]

La propiedad intelectual (PI) se ha convertido en el principal vehículo de evasión fiscal.

— UCLA Law Review , "Soluciones de la legislación sobre propiedad intelectual para la evasión fiscal", (2015) [281]

En lugar de un "centro mundial de conocimiento" para "vender en Europa", se podría sugerir que Irlanda es una base para multinacionales estadounidenses con suficiente propiedad intelectual para usar las herramientas BEPS de Irlanda para proteger los ingresos no estadounidenses de los impuestos estadounidenses. [16]

Ningún otro país de la OCDE que no sea un paraíso fiscal registra una proporción tan alta de ganancias extranjeras contabilizadas en paraísos fiscales [t] como Estados Unidos. [...] Esto sugiere que la mitad de todas las ganancias globales trasladadas a paraísos fiscales son trasladadas por multinacionales estadounidenses. En cambio, alrededor del 25% se acumula en países de la UE, el 10% en el resto de la OCDE y el 15% en países en desarrollo (Tørsløv et al., 2018).

— Gabriel Zucman , Thomas Wright, “EL PRIVILEGIO FISCAL EXORBITANTE”, Documentos de trabajo del NBER (septiembre de 2018). [13]

En 2018, Estados Unidos se convirtió en un sistema fiscal híbrido "territorial" (Estados Unidos era uno de los últimos sistemas fiscales puros "mundiales" que quedaban). [17] Después de esta conversión, las tasas impositivas efectivas de Estados Unidos para las multinacionales estadounidenses con gran peso de la propiedad intelectual son muy similares a las tasas impositivas efectivas que incurrirían si tuvieran su sede legal en Irlanda, incluso netas de herramientas BEPS irlandesas completas como el doble Irish . Esto representa un desafío sustancial para la economía irlandesa (ver el efecto de la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de Estados Unidos ). [282] [283] Sin embargo, § Los problemas técnicos con TCJA significan que algunas herramientas BEPS irlandesas, como § Green Jersey de Apple, se han mejorado.

La reciente expansión de Irlanda hacia los servicios de paraísos fiscales tradicionales (por ejemplo, las ICAV y los L–QIAIF del tipo de las Islas Caimán y Luxemburgo ) es un factor de diversificación con respecto a los servicios de paraísos fiscales corporativos de los EE. UU. [284] El Brexit fue inicialmente decepcionante para Irlanda en el área de atraer firmas de servicios financieros de Londres, pero la situación mejoró más tarde. El Brexit ha llevado al crecimiento de firmas de derecho tributario centradas en el Reino Unido (incluidas las firmas de círculo mágico offshore ), que establecen oficinas en Irlanda para manejar servicios de paraísos fiscales tradicionales para los clientes. [285]

Si bien el desarrollo de Irlanda hacia herramientas de paraíso fiscal tradicionales (por ejemplo, ICAV y L–QIAIF) es más reciente, el estatus de Irlanda como paraíso fiscal corporativo se ha observado desde 1994 (el primer documento de Hines–Rice sobre paraísos fiscales), [29] y se ha debatido en el Congreso de los EE. UU. durante una década. [57] La falta de progreso y los retrasos en el abordaje de las herramientas BEPS del impuesto corporativo de Irlanda son evidentes:

Los expertos en paraísos fiscales explican estas contradicciones como resultado de las diferentes agendas de las principales autoridades fiscales de la OCDE, y en particular de los EE. UU. [13] y Alemania, quienes, si bien no se consideran paraísos fiscales o paraísos fiscales corporativos, ocupan el segundo y séptimo lugar respectivamente en el Índice de Secreto Financiero de 2018 de jurisdicciones de secreto fiscal : [135] [298] [299] [300]

Antes de la aprobación de la TCJA en diciembre de 2017, Estados Unidos era una de las ocho jurisdicciones restantes que aplicaban un sistema tributario "mundial", lo que era el principal obstáculo para la reforma del impuesto corporativo estadounidense, ya que no era posible diferenciar entre las fuentes de ingresos. [u] Los otros siete sistemas tributarios "mundiales" son: Chile, Grecia, Irlanda, Israel, Corea, México y Polonia. [306]

Los expertos en impuestos esperan que las disposiciones anti-BEPS del nuevo sistema tributario "territorial" híbrido de la TCJA, los regímenes tributarios GILTI y BEAT, neutralicen algunas herramientas BEPS irlandesas (por ejemplo, el doble irlandés y el whisky de malta). Además, el régimen tributario FDII de la TCJA hace que a las multinacionales controladas por los EE. UU. les resulte indiferente si facturan su propiedad intelectual desde los EE. UU. o desde Irlanda, ya que las tasas impositivas netas efectivas sobre la propiedad intelectual, bajo los regímenes FDII y GILTI, son muy similares. Después de la TCJA, las multinacionales controladas por los EE. UU. con una gran presencia de propiedad intelectual del S&P 500, tienen tasas impositivas para 2019 similares, ya sea que tengan su sede legal en Irlanda o en los EE. UU. [h] [18] [309]

El académico fiscal Mihir A. Desai , en una entrevista posterior a la TCJA en la Harvard Business Review, dijo que: "Por lo tanto, si piensas en muchas empresas de tecnología que tienen su sede en Irlanda y operaciones masivas allí, tal vez no las necesiten de la misma manera, y esas pueden reubicarse nuevamente en los EE. UU. [310]

Se espera que Washington sea menos tolerante con las multinacionales estadounidenses que utilizan las herramientas BEPS irlandesas y ubican la propiedad intelectual en paraísos fiscales. [284] La Comisión Europea también se ha vuelto menos tolerante con el uso de las herramientas BEPS irlandesas por parte de las multinacionales estadounidenses, como lo demuestra la multa de 13 mil millones de euros a Apple por evasión fiscal irlandesa entre 2004 y 2014. Existe un descontento generalizado con las herramientas BEPS irlandesas en Europa, incluso en otros paraísos fiscales. [311]

"Ahora que se aprobó la reforma del impuesto de sociedades [en Estados Unidos], las ventajas de ser una empresa invertida son menos obvias"

— Jami Rubin, directora general y jefa del grupo de investigación en ciencias biológicas de Goldman Sachs (marzo de 2018). [18]

Si bien los compromisos políticos de Washington y la UE que toleran a Irlanda como paraíso fiscal corporativo pueden estar debilitándose, los expertos fiscales señalan varias fallas técnicas en la TCJA que, si no se resuelven, en realidad pueden mejorar a Irlanda como paraíso fiscal corporativo estadounidense: [140] [141] [312] [313]

A June 2018 IMF country report on Ireland, while noting the significant exposure of Ireland's economy to U.S. corporates, concluded that the TCJA may not be as effective as Washington expects in addressing Ireland as a U.S. corporate tax haven. In writing its report, the IMF conducted confidential anonymous interviews with Irish corporate tax experts.[315]

Some tax experts, noting Google and Microsoft's actions in 2018, assert these flaws in the TCJA are deliberate, and part of the U.S. Administration's original strategy to reduce aggregate effective global tax rates for U.S. multinationals to circa 10–15% (i.e. 21% on U.S. income, and 2.5% on non–U.S. income, via Irish BEPS tools).[316] There has been an increase in U.S. multinational use of Irish intangible capital allowances, and some tax experts believe that the next few years will see a boom in U.S. multinationals using the Irish "Green Jersey" BEPS tool and on-shoring their IP to Ireland (rather than the U.S.).[144]

As discussed in § Hines–Rice 1994 definition and § Source of contradictions, the U.S. Treasury's corporation tax policy seeks to maximise long-term U.S. taxes paid by using corporate tax havens to minimise near-term foreign taxes paid. In this regard, it is possible that Ireland still has a long-term future as a U.S. corporate tax haven.

It is undoubtedly true that some American business operations are drawn offshore by the lure of low tax rates in tax havens; nevertheless, the policies of tax havens may, on net, enhance the U.S. Treasury's ability to collect tax revenue from American corporations.

— James R. Hines Jr. & Eric M Rice, Fiscal Paradise: Foreign tax havens and American business, 1994.[29]

In February 2019, Brad Setser from the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote a New York Times article highlighting material issues with TCJA.[19]

The following are the most cited papers on "tax havens", as ranked on the IDEAS/RePEc database of economic papers, at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.[37]

Papers marked with (‡) were also cited by the EU Commission's 2017 summary as the most important research on tax havens.[36]

(with at least 300 citations on Google Scholar)

Pearse Doherty: It was interesting that when [MEP] Matt Carthy put that to the Minister's predecessor (Michael Noonan), his response was that this was very unpatriotic and he should wear the green jersey. That was the former Minister's response to the fact there is a major loophole, whether intentional or unintentional, in our tax code that has allowed large companies to continue to use the double Irish [called single malt]

Separately, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar told attendees [at a U.S. Embassy event in Ireland] that "Ireland is not a tax haven, we do not wish to be a haven, nor do we wish to be seen as one".

Pascal Saint Amans, the director of the OCED's centre for tax policy and administration, told an Oireachtas Committee today that Ireland does not meet any of the organisation's criteria to be defined as a tax haven – that there is no taxes, no transparency and no exchange of information

Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network said: It's disheartening to see the OECD fall back into the old pattern of creating 'tax haven' blacklists on the basis of criteria that are so weak as to be near enough meaningless, and then declaring success when the list is empty."

European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs Pierre Moscovici was in Dublin on Tuesday, appearing before the Oireachtas Finance Committee where he faced questions from TDs and Senators on the relaunched Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB).

* Ireland joined Panama and Monaco on Brazil blacklist.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

Research conducted by academics at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Copenhagen estimated that foreign multinationals moved €90 billion of profits to Ireland in 2015 — more than all Caribbean countries combined.

Figure 3. Foreign Direct Investment – Over half of Irish outbound FDI is routed to Luxembourg

[Ireland] It is the "captured state", over again.

John Christensen and Mark Hampton (1999) have shown [..] how several tax havens [including Ireland] have in effect been "captured" by these private interests, which literally draft local laws to suit their interests.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)Lower foreign tax rates entail smaller credits for foreign taxes and greater ultimate U.S. tax collections (Hines and Rice, 1994). Dyreng and Lindsey (2009), offer evidence that U.S. firms with foreign affiliates in certain tax havens pay lower pay lower foreign taxes and higher U.S. taxes than do otherwise-similar large U.S. companies

Finally, we find that U.S. firms with operations in some tax haven countries have higher federal tax rates on foreign income than other firms. This result suggests that in some cases, tax haven operations may increase U.S. tax collections at the expense of foreign country tax collections.

"Ireland solidifies its position as the #1 tax haven," Zucman said on Twitter. "U.S. firms book more profits in Ireland than in China, Japan, Germany, France & Mexico combined. Irish tax rate is 5.7%."

While lawmakers generally refer to the new system as a "territorial" tax system, it is more appropriately described as a hybrid system.

The new tax code addresses the historical competitive disadvantage of U.S.–based multinationals in terms of tax rates and international access to capital, and helps level the playing field for U.S. companies, Pfizer CEO Ian Read.

In 2007 to 2009, WPP, United Business Media, Henderson Group, Shire, Informa, Regus, Charter and Brit Insurance all left the UK. By 2015, WPP, UBM, Henderson Group, Informa and Brit Insurance have all returned

Jurisdictions with the largest financial systems relative to GDP (Exhibit 2-3) tend to have relatively larger OFI [or Shadow Banking] sectors: Luxembourg (at 92% of total financial assets), the Cayman Islands (85%), Ireland (76%) and the Netherlands (58%)

A new University of Amsterdam CORPNET study has found that the Netherlands, the UK, Switzerland, Singapore and Ireland are the leading intermediary countries that corporations use to funnel their money to and from tax havens

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

Various attempts have been made to identify and list tax havens and offshore finance centres (OFCs). This Briefing Paper aims to compare these lists and clarify the criteria used in preparing them.

Tax havens are low-tax jurisdictions that offer businesses and individuals opportunities for tax avoidance" (Hines, 2008). In this paper, I will use the expression "tax haven" and "offshore financial center" interchangeably (the list of tax havens considered by Dharmapala and Hines (2009) is identical to the list of offshore financial centers considered by the Financial Stability Forum (IMF, 2000), barring minor exceptions)

Some experts see no difference between tax havens and OFCs, and employ the terms interchangeably.

Yet today it is difficult to distinguish between the activities of tax havens and OFCs.

The economist [Kevin Hassett], who has previously referred to the Republic as a tax haven, said there had been a need to introduce reforms in the US, which have brought its corporate rate down to 21 per cent.

Figure D: Tax Haven Literature Review: A Typology

Tax Havens by Most Cited

There are roughly 45 major tax havens in the world today. Examples include Andorra, Ireland, Luxembourg and Monaco in Europe, Hong Kong and Singapore in Asia, and the Cayman Islands, the Netherlands Antilles, and Panama in the Americas.

Table 1: 52 Tax Havens

Table 1: List of Tax Havens

Page 1067: List of Tax Havens

The balance of payments provides a country-by-country decomposition of this total, indicating that 55 percent are made in six tax havens: the Netherlands, Bermuda, Luxembourg, Ireland, Singapore, and Switzerland (Figure 2)

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $200 billion globally

Examples of such tax havens include Ireland and Luxembourg in Europe, Hong Kong and Singapore in Asia, and various Caribbean island nations in the Americas.

The eight major pass-through economies—the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong SAR, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Ireland, and Singapore—host more than 85 percent of the world's investment in special purpose entities, which are often set up for tax reasons.

Table A1: Tax havens full list:IRELAND

A Survey of surveys of the eleven best known and most authoritative lists of tax havens of the world found that Switzerland is considered as a tax haven by nine of them, Luxembourg and Ireland by eight, the Netherlands by two and Belgium by one

Countries traditionally perceived as tax havens (Cyprus, Ireland and the United Kingdom)

Ireland meets all of these characteristics and together with Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland have been described as the four OECD tax havens.

The study provided figures for the combined profits reported by American multinational corporations in '10 notorious tax havens' – a list that included Ireland, the Netherlands and Switzerland

Table 1: Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions and the Sources of Those Jurisdictions

Table 1. Countries Listed on Various Tax Haven Lists

A number of studies show that multinational corporations are moving "mobile" income out of the United States into low or no tax jurisdictions, including tax havens such as Ireland, Bermuda, and the Cayman Islands.

Senators LEVIN and McCAIN: Most reasonable people would agree that negotiating special tax arrangements that allow companies to pay little or no income tax meets a common-sense definition of a tax haven.

Large corporations like Apple, Google, Nike and Starbucks all take steps to book profits in tax havens such as Bermuda and Ireland

At least 125 major U.S. companies have registered several hundred subsidiaries or investment funds at 70 Sir John Rogerson's Quay, a seven-story building in Dublin's docklands, according to a review of government and corporate records by The Wall Street Journal. The common thread is the building's primary resident: Matheson, an Irish law firm that specializes in ways companies can use Irish tax law.

That undermines Ireland's insistence that it is not a tax haven, making it more difficult to defend its system in an international climate that is turning sharply against tax avoidance.

The Netherlands, and other low-tax havens such as Ireland and Luxembourg, have attracted much criticism from other countries for the legal loopholes they leave open to encourage such tax avoidance by big corporations.

These examples feel far more relevant to the corporate tax issue analysis than comparisons to small economies and tax havens like Ireland and Switzerland upon which the CEA relies

Our research shows that six European tax havens alone (Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Malta and Cyprus) siphon off a total of €350bn every year

IRELAND'S CORPORATE TAX rate has come under heavy criticism at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Members of the European parliament have voted to include the Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus on the official EU tax haven black list.

The Republic helps big multinationals to engage in aggressive tax planning and the European Commission should regard it as one of five "EU tax havens" until substantial tax reforms are implemented.

SPD parliamentary secretary Carsten Schneider called Irish "tax dumping" a "poison for democracy" ahead of a vote which saw the Bundestag grant Ireland's request

We won't go along with this free pass for Ireland because we don't want ongoing tax dumping in the EU. We're not talking about Ireland's 12.5 per cent tax rate here, but secret deals that reduce that tax burden to near zero.

Google Inc., Facebook Inc. and LinkedIn Corp. wound up in Ireland because they could reduce their tax bills. Their success is leading European and U.S. politicians to label the country a tax haven that must change its ways

The four OECD member countries Luxembourg, Ireland, Belgium and Switzerland, which can also be regarded as tax havens for multinationals because of their special tax regimes.

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki made an emotive plea for reform – saying EU tax havens should be abolished in a thinly veiled swipe at Ireland.

Despite such developments, "Team Ireland" has constantly dismissed the description of Ireland as a tax haven, even when the extent of that haven is patently obvious.

There is a broad consensus that Ireland must defend its 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate. But that rate is defensible only if it is real. The great risk to Ireland is that we are trying to defend the indefensible. It is morally, politically and economically wrong for Ireland to allow vastly wealthy corporations to escape the basic duty of paying tax. If we don't recognise that now, we will soon find that a key plank of Irish policy has become untenable.

And as the UN's Philip Aston says, 'when lists of tax havens are drawn up, Ireland is always prominently among them'. The U.S. Senate similarly found that by any 'common sense definition of a tax haven' Ireland easily met the criteria. I mean when Forbes regularly ranks you in their list of 'Top ten tax havens', there's not really much of a debate to be had.

Eurostat's structural business statistics give a range of measures of the business economy broken down by the controlling country of the enterprises. Here is the Gross Operating Surplus generated in Ireland in 2015 for the countries with figures reported by Eurostat.

Ireland has, more or less, stopped using GDP to measure its own economy. And on current trends [because Irish GDP is distorting EU–28 aggregate data], the eurozone taken as a whole may need to consider something similar.

Profit shifting also has a significant effect on trade balances. For instance, after accounting for profit shifting, Japan, the UK, France, and Greece turn out to have trade surpluses in 2015, in contrast to the published data that record trade deficits. According to our estimates, the true trade deficit of the United States was 2.1% of GDP in 2015, instead of 2.8% in the official statistics—that is, a quarter of the recorded trade deficit of the United States is an illusion of multinational corporate tax avoidance.

Ireland's effective tax rate on all foreign corporates (U.S. and non-U.S.) is 4%

Economists suggest offshore activity has given misleading picture of health.

The use of private "unlimited liability company" (ULC) status, which exempts companies from filing financial reports publicly. The fact that Apple, Google and many others continue to keep their Irish financial information secret is due to a failure by the Irish government to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive, which would require full public financial statements, until 2017, and even then retaining an exemption from financial reporting for certain holding companies until 2022

Local subsidiaries of multinationals must always be required to file their accounts on public record, which is not the case at present. Ireland is not just a tax haven at present, it is also a corporate secrecy jurisdiction.

125 Russian-linked companies raise €103 billion through IFSC; some entities linked to embargoed and sanctioned companies

Regulation has been described as light touch regulation/unregulated

SPVs, QIAIFs and ICAVs. They're acronyms only corporate wonks could love. But they have entered the lexicon of the Dáil in recent months as Opposition members have highlighted how these corporate structures have been used to great advantage by so-called vulture funds to minimise taxes on property bought at bargain basement prices in recent years.

Regulator attributes decline to the decision of funds to exit their so-called 'section 110 status'

Fianna Fáil claims that funds have discovered a "new nirvana". Documents also reveal new strategy to avoid regulation.

Vulture funds are putting in place new strategies to avoid tax and regulation, the Sunday Business Post reports. Citing a letter from Fianna Fail TD Stephen Donnelly to the Minister for Finance, it says the funds have moved substantial sums from the controversial Section 110 companies and into other entities called L-QIAIFs (loan-originating qualifying alternative investment funds). These do not file public accounts.

IP onshoring is something we should be expecting to see much more of as we move towards the end of the decade. Buckle up!

Irish politicians are "mindlessly in favour" of growing the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), according to a former deputy governor of the Central Bank

The same source in comparing different investment vehicles states that :- Another positive of the Section 110 Company is that there are no regulatory restrictions regarding lending as is the case with a QIF (Qualifying Investor Fund).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has raised concerns about instances where individual bankers and lawyers were appointed to hundreds of boards of unregulated special-purpose vehicles in Dublin's International Financial Services Centre.

Certain funds in operation here are seeing foreign property investors paying no tax on income. The value of property owned in these QIAIFs is in the region of €300 billion.

Icavs were introduced last year, following lobbying by the funds industry, to tempt certain types of offshore fund business to Ireland. It has since emerged, however, that the structures have been widely utilised to avoid tax on Irish property.

Ireland is a wonderful, special country in many ways. But when it comes to providing foreigners with lax financial regulation or tax trickery, it is a goddamned rogue state

The massive profitability levels of European banks in Ireland suggests that large profits may be reported in Ireland as a tax-avoidance strategy

The massive profitability levels of European banks in Ireland suggests that large profits may be reported in Ireland as a tax-avoidance strategy

Irish withholding tax on transfers to Luxembourg can be avoided if structured as a Eurobond

The Irish Collective Asset-management Vehicle was a nifty little tax structure introduced last year. Designed to primarily facilitate the transfer of U.S. funds into Dublin, it allows foreign investors to channel their investments through Ireland while paying no tax.

Internal Department of Finance briefing documents reveal that officials believe there has been "extremely significant" tax leakage due to investors using special purpose vehicles.

Since then we have retained our position as the leading Irish counsel on ICAVs and to date have advised on 30% of all ICAV sub-funds authorised by the Central Bank, which is nearly twice as many as our nearest rival.

ANDREA KELLY (PwC Ireland): "We expect most Irish QIAIFs to be structured as ICAVs from now on and given that ICAVs are superior tax management vehicles to the Cayman Island SPCs, Ireland should attract substantial re-domiciling business

But on another level this is an Irish version of a phenomenon we've encountered across the tax haven world: the state 'captured' by offshore financial services.

Brussels. 30.8.2016 C(2016) 5605 final. Total Pages (130)

The Commission's investigation concluded that Ireland granted illegal tax benefits to Apple, which enabled it to pay substantially less tax than other businesses over many years. In fact, this selective treatment allowed Apple to pay an effective corporate tax rate of 1 percent on its European profits in 2003 down to 0.005 percent in 2014.

As a consequence of the overall scale of these additions, elements of the results that would previously been published are now suppressed to protect the confidentiality of the contributing companies, in accordance with the Statistics Act 1993

A key architect [for Apple] was Baker McKenzie, a huge law firm based in Chicago. The firm has a reputation for devising creative offshore structures for multinationals and defending them to tax regulators. It has also fought international proposals for tax avoidance crackdowns.

Confidentiality and use of information for statistical purposes: Information obtained under the Statistics Act is strictly confidential, under Section 33 of the Statistics Act, 1993. It may only be accessed by Officers of Statistics, who are required to sign a Declaration of Secrecy under Section 21.

Revenue said: "Interactions between Revenue and individual taxpayers are subject to the taxpayer confidentiality provisions of Section 851A".

The willingness to brush dirt under the carpet to support the financial sector, and an equating of these policies with patriotism (sometimes known in Ireland as the Green Jersey agenda,) contributed to the remarkable regulatory laxity with massive impacts in other nations (as well as in Ireland itself) as global financial firms sought an escape from financial regulation in Dublin.

"The Irish authorities knew exactly what was going on, long before the international community finally blew the whistle.

Eurostat's structural business statistics give a range of measures of the business economy broken down by the controlling country of the enterprises. Here is the Gross Operating Surplus generated in Ireland in 2015 for the countries with figures reported by Eurostat.

Germany taxes only 5% of the active foreign business profits of its resident corporations. [..] Similarly, Irish multinationals do not benefit from this system as the Revenue Commissioners tax Irish Companies on worldwide income, whereas the IRS only tax profits repatriated to the USA. Furthermore, German firms do not have incentives to structure their foreign operations in ways that avoid repatriating income. Therefore, the tax incentives for German firms to establish tax haven affiliates are likely to differ from those of US firms and bear strong similarities to those of other G-7 and OECD firms.

The total value of U.S. business investment in Ireland – ranging from data centres to the world's most advanced manufacturing facilities – stands at $387bn (€334bn) – this is more than the combined U.S. investment in South America, Africa and the Middle East, and more than the BRIC countries combined.

But Mr Kenny noted that Oxfam included Ireland's 12.5 per cent corporation tax rate as one of the factors for deeming it a tax haven. "The 12.5 per cent is fully in line with the OECD and international best practice in having a low rate and applying it to a very wide tax base."

Suggestions that Ireland are a tax haven simply because of our longstanding 12.5% corporate tax rate are totally out of line with the agreed global consensus that a low corporate tax rate applied to a wide tax base is good economic policy for attracting investment and supporting economic growth.

Misleadingly, studies cited by the Irish Times and other outlets suggest that the effective tax rate is close to the headline 12.5 percent rate – but this is a fictional result based on a theoretical 'standard firm with 60 employees' and no exports: it is entirely inapplicable to transnationals. Though there are various ways to calculate effective tax rates, other studies find rates of just 2.5–4.5 percent.

A study by James Stewart, associate professor in finance at Trinity College Dublin, suggests that in 2011 the subsidiaries of U.S. multinationals in Ireland paid an effective tax rate of 2.2 per cent.

Meanwhile, the tax rate reported by those Irish subsidiaries of U.S. companies plummeted to 3% from 9% by 2010

Structure 1: The profits of the Irish company will typically be subject to the corporation tax rate of 12.5% if the company has the requisite level of substance to be considered trading. The tax depreciation and interest expense can reduce the effective rate of tax to a minimum of 2.5%.

The tax deduction can be used to achieve an effective tax rate of 2.5% on profits from the exploitation of the IP purchased. Provided the IP is held for five years, a subsequent disposal of the IP will not result in a clawback.

Intellectual Property: The effective corporation tax rate can be reduced to as low as 2.5% for Irish companies whose trade involves the exploitation of intellectual property. The Irish IP regime is broad and applies to all types of IP. A generous scheme of capital allowances in Ireland offers significant incentives to companies who locate their activities in Ireland. A well-known global company [Accenture in 2009] recently moved the ownership and exploitation of an IP portfolio worth approximately $7 billion to Ireland.

Under the arrangement – known as the special assignee relief (Sarp) – 30% of income above €75,000 is exempt from income tax. Those who benefit are also allowed a €5,000 per child tax–free allowance for school fees, if those fees are paid by their employer

There is no single definition of a tax haven, although there are a number of commonalities in the various concepts used

IFAC member and economist Martina Lawless said on the basis of the OECD's criteria for tax havens, which are internationally recognised, Ireland was not one.

The OECD outlined certain factors which in its view described a tax haven.

The OECD stated that for a country to be a tax haven, it had to have certain characteristics.

As a result of the Bush Administration's efforts, the OECD backed away from its efforts to target "harmful tax practices" and shifted the scope of its efforts to improving exchanges of tax information between member countries.

The OECD is clearly ill-equipped to deal with tax-havens, not least as many of its members, including the UK, Switzerland, Ireland and the Benelux countries are themselves considered tax havens

TAX HAVENS: 1.Andorra 2.Anguilla 3.Antigua and Barbuda 4.Aruba 5.Bahamas 6.Bahrain 7.Barbados 8.Belize 9.British Virgin Islands 10.Cook Islands 11.Dominica 12.Gibraltar 13.Grenada 14.Guernsey 15.Isle of Man 16.Jersey 17.Liberia 18.Liechtenstein 19.Maldives 20.Marshall Islands 21.Monaco 22.Montserrat 23.Nauru 24.Net Antilles 25.Niue 26.Panama 27.Samoa 28.Seychelles 29.St. Lucia 30.St. Kitts & Nevis 31.St. Vincent and the Grenadines 32.Tonga 33.Turks & Caicos 34.U.S. Virgin Islands 35.Vanuatu