Malayalam ( / ˌ m æ l ə ˈ j ɑː l ə m / ; [6] മലയാളം , malayāḷam , IPA: [mɐlɐjaːɭɐm] ) es unalengua dravídicahablada en el estado indio deKeralay los territorios de la unión deLakshadweepyPuducherry(distrito de Mahé) por elmalayali. Es uno de los 22idiomas programadosde la India. El malabar fue designado "idioma clásico de la India" en 2013, citando sus 2500 años de uso continuo.[7][8]El malabar tienede idioma oficialen Kerala, Lakshadweep y Puducherry (Mahé),[9][10][11]y también es el idioma hablado principal de Lakshadweep. El malabar es hablado por 35 millones de personas en la India.[12]El malabar también es hablado por minorías lingüísticas en los estados vecinos; con un número significativo de hablantes en losKodaguyDakshina KannadadeKarnataka, yKanyakumari,CoimbatoreyNilgirisde Tamil Nadu. También lo habla ladiáspora malayalien todo el mundo, especialmente en lospaíses del Golfo Pérsico, debido a la gran población demalayalique hay allí. Son una población significativa en todas las ciudades dela IndiaincluidasMumbai,Bengaluru,Chennai,Delhi,Hyderabad, etc.

El origen del malabar sigue siendo un tema de disputa entre los académicos. La opinión dominante sostiene que el malabar desciende del tamil medio temprano y se separó de él en algún momento entre los siglos IX y XIII. [13] Una segunda opinión defiende el desarrollo de las dos lenguas a partir del "protodravídico" o "prototamil-malabar" en la era prehistórica, [14] aunque esto es generalmente rechazado por los lingüistas históricos. [15] Las placas de cobre sirias quilon de 849/850 d. C. son consideradas por algunos como la inscripción más antigua disponible escrita en malabar antiguo . Sin embargo, la existencia del malabar antiguo es a veces cuestionada por los académicos. [16] Consideran que el idioma de inscripción chera perumal es un dialecto divergente o una variedad del tamil contemporáneo . [16] [17] La obra literaria existente más antigua en malabar distinta de la tradición tamil es el Ramacharitam (finales del siglo XII o principios del XIII). [18]

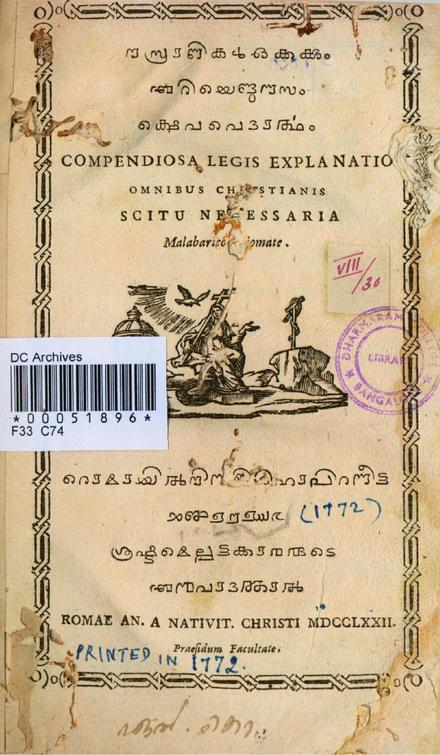

La primera escritura utilizada para escribir malabar fue la escritura vatteluttu . [19] La escritura malabar actual se basa en la escritura vatteluttu, que se amplió con letras de la escritura grantha para adoptar préstamos indoarios . [19] [20] Tiene una gran similitud con la escritura tigalari , una escritura histórica que se utilizó para escribir el idioma tulu en el sur de Canara y el sánscrito en la región adyacente de Malabar . [21] La gramática malabar moderna se basa en el libro Kerala Panineeyam escrito por AR Raja Raja Varma a fines del siglo XIX d. C. [22] El primer diario de viaje en cualquier idioma indio es el malabar Varthamanappusthakam , escrito por Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar en 1785. [23] [24]

Robert Caldwell describe la extensión del malayalam en el siglo XIX como una extensión que se extendía desde las cercanías de Kumbla en el norte, donde reemplaza al tulu, hasta Kanyakumari en el sur, donde comienza a ser reemplazado por el tamil , [25] junto a las islas habitadas de Lakshadweep en el mar Arábigo .

La palabra malayalam se originó de las palabras mala , que significa ' montaña ', y alam , que significa ' región ' o '-barco' (como en "municipio"); Malayalam, por lo tanto, se traduce directamente como 'la región montañosa '. El término Malabar se usó como un término alternativo para Malayalam en los círculos de comercio exterior para denotar la costa suroeste de la península india, que también significa La tierra de las colinas . [26] [27] [28] [29] El término originalmente se refería a la tierra montañosa occidental de la dinastía Chera (más tarde Zamorins y el Reino de Cochin ), el Reino de Ezhimala (más tarde Kolathunadu ) y el reino Ay (más tarde Travancore ), y solo más tarde se convirtió en el nombre de su idioma. [30] El idioma malayalam se llamó alternativamente Alealum , Malayalani , Malayali , Malabari , Malean , Maliyad , Mallealle y Kerala Bhasha hasta principios del siglo XIX EC. [31] [32] [33]

Las primeras obras literarias existentes en el idioma regional de la actual Kerala probablemente datan del siglo XII . En ese momento, el idioma se diferenciaba por el nombre Kerala Bhasha . La identidad distintiva del nombre "Malayalam" de esta lengua parece haber surgido solo alrededor del siglo XVI , cuando se conocía como "Malayayma" o "Malayanma"; las palabras también se usaban para referirse a la escritura y la región . [34] Según Duarte Barbosa , un visitante portugués que visitó Kerala a principios del siglo XVI d. C., la gente de la costa suroccidental de Malabar de la India, desde Kumbla en el norte hasta Kanyakumari en el sur, tenía un idioma único, que ellos llamaban "Maliama". [35] [36]

Antes de este período , la gente de Kerala solía referirse a su lengua como "tamil", y ambos términos se superpusieron durante el período colonial . [nota 1]

.jpg/440px-Quilon_Syrian_copper_plates_(849_AD).jpg)

Debido al aislamiento geográfico de la costa de Malabar del resto de la península india debido a la presencia de las cadenas montañosas de los Ghats occidentales que se encuentran paralelas a la costa, el dialecto del antiguo tamil hablado en Kerala era diferente del hablado en Tamil Nadu . [32] La opinión predominante sostiene que el malabar comenzó a crecer como una lengua literaria distinta del dialecto costero occidental del tamil medio [39] y la separación lingüística se completó en algún momento entre los siglos IX y XIII. [40] [41] Los renombrados poetas del tamil clásico como Paranar (siglo I d. C.), Ilango Adigal (siglos II-III d. C.) y Kulasekhara Alvar (siglo IX d. C.) eran keralitas . [32] Las obras de Sangam pueden considerarse como el antiguo predecesor del malabar. [42]

Sin embargo, algunos estudiosos creen que tanto el tamil como el malabar se desarrollaron durante el período prehistórico a partir de un ancestro común, el "prototamil-malabar", y que la noción de que el malabar es una "hija" del tamil es errónea. [14] Esto se basa en el hecho de que el malabar y varias lenguas dravídicas de la costa occidental tienen características arcaicas comunes que no se encuentran ni siquiera en las formas históricas más antiguas del tamil literario. [43] A pesar de esto, el malabar comparte muchas innovaciones comunes con el tamil que surgieron durante el período tamil medio temprano, lo que hace imposible la descendencia independiente. [13] [nota 2] Por ejemplo, el tamil antiguo carece de los pronombres de primera y segunda persona del plural con la terminación kaḷ . Es en la etapa del tamil medio temprano cuando aparece por primera vez kaḷ : [45]

De hecho, la mayoría de las características de la morfología del malayalam son derivables de una forma de habla correspondiente al tamil medio temprano. [46]

Robert Caldwell , en su libro de 1856 " Una gramática comparada de la familia de lenguas dravídicas o del sur de la India" , opinó que el malabar literario se derivó del tamil clásico y con el tiempo adquirió una gran cantidad de vocabulario sánscrito y perdió las terminaciones personales de los verbos. [30] Como lengua de erudición y administración, el tamil antiguo, que se escribió en tamil-brahmi y más tarde en el alfabeto vatteluttu, influyó enormemente en el desarrollo temprano del malabar como lengua literaria. La escritura malabar comenzó a divergir de las escrituras vatteluttu y grantha occidental en los siglos VIII y IX de la era común . A fines del siglo XIII, surgió una forma escrita del idioma que era única respecto de la escritura vatteluttu que se usaba para escribir tamil en la costa este. [47]

El antiguo malabar ( Paḻaya Malayāḷam ), una lengua de inscripción que se encontró en Kerala desde alrededor del siglo IX hasta alrededor del siglo XIII d. C., [48] es la forma más antigua atestiguada de malabar. [49] [50] El comienzo del desarrollo del antiguo malabar a partir de un dialecto costero occidental del tamil medio se puede fechar alrededor del siglo VIII d. C. [51] [19] [52] Siguió siendo un dialecto de la costa oeste hasta alrededor del siglo IX d. C. o un poco más tarde. [53] [51] El origen del calendario malabar se remonta al año 825 d. C. [54] [55] [56] En general, se acepta que el dialecto costero occidental del tamil comenzó a separarse, divergir y crecer como una lengua distinta debido a la separación geográfica de Kerala del país tamil [53] y la influencia del sánscrito y el prácrito de los brahmanes nambudiri de la costa de Malabar . [49] [32]

El antiguo idioma malabar se empleó en varios registros y transacciones oficiales (a nivel de los reyes Chera Perumal , así como en los templos de las aldeas de casta superior ( Nambudiri )). [49] La mayoría de las inscripciones en antiguo malabar se encontraron en los distritos del norte de Kerala , los que se encuentran adyacentes a Tulu Nadu . [49] El antiguo malabar se escribió principalmente en escritura vatteluttu (con caracteres pallava/grantha del sur ). [49] El antiguo malabar tenía varias características distintas del tamil contemporáneo, que incluyen la nasalización de sonidos adyacentes, la sustitución de sonidos palatales por sonidos dentales, la contracción de vocales y el rechazo de verbos de género. [49] [57] [58] Ramacharitam y Thirunizhalmala son las posibles obras literarias del antiguo malabar se encontraron hasta ahora.

El malayalam antiguo se convirtió gradualmente en malayalam medio ( Madhyakaala malayalam ) en el siglo XIII d.C. [59] La literatura malayalam también divergió completamente de la literatura tamil durante este período. Obras como Unniyachi Charitham , Unnichiruthevi Charitham y Unniyadi Charitham están escritas en malayalam medio y se remontan a los siglos XIII y XIV de la Era Común . [60] [32] Los Sandesha Kavya del siglo XIV d.C. escritos en idioma Manipravalam incluyen a Unnuneeli Sandesam . [60] [32] Kannassa Ramayanam y Kannassa Bharatham de Rama Panikkar de los poetas Niranam que vivieron entre 1350 y 1450, son representativos de esta lengua. [61] Ulloor ha opinado que Rama Panikkar ocupa la misma posición en la literatura malayalam que Edmund Spenser en la literatura inglesa . [61] El Champu Kavyas escrito por Punam Nambudiri, uno de los Pathinettara Kavikal (Dieciocho poetas y medio) en la corte del Zamorin de Calicut , también pertenecen al malayalam medio. [32] [60] Las obras literarias de este período estuvieron fuertemente influenciadas por Manipravalam , que era una combinación de tamil y sánscrito contemporáneos . [32] La palabra Mani-Pravalam significa literalmente Coral diamante o coral rubí . El texto Lilatilakam del siglo XIV afirma que el manipravalam es un bhashya (idioma) en el que "el dravida y el sánscrito deben combinarse como el rubí y el coral, sin el menor rastro de discordia". [62] [63 ] Las escrituras Kolezhuthu y Malayanma también se utilizaron para escribir el malayalam medio . Además de la escritura Vatteluthu y Grantha , se utilizaron para escribir el malabar antiguo . [32] Las obras literarias escritas en malabar medio estuvieron fuertemente influenciadas por el sánscrito y el prácrito., al compararlos con la literatura malayalam moderna . [60] [32]

El malayalam medio fue sucedido por el malayalam moderno ( Aadhunika Malayalam ) en el siglo XV d.C. [32] El poema Krishnagatha escrito por Cherusseri Namboothiri , poeta de la corte del rey Udaya Varman Kolathiri (1446-1475) de Kolathunadu , está escrito en malayalam moderno. [60] El idioma utilizado en Krishnagatha es la forma hablada moderna del malayalam. [60] Durante el siglo XVI d.C., Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan del Reino de Tanur y Poonthanam Nambudiri del Reino de Valluvanad , siguieron la nueva tendencia iniciada por Cherussery en sus poemas. El Adhyathmaramayanam Kilippattu y Mahabharatham Kilippattu , escritos por Ezhuthachan, y Jnanappana , escrito por Poonthanam, también se incluyen en la forma más antigua del malayalam moderno. [60]

A Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan también se le atribuye el desarrollo de la escritura malayalam en la forma actual a través de la mezcla y modificación de las antiguas escrituras de Vatteluttu , Kolezhuthu y Grantha , que se usaban para escribir las inscripciones y obras literarias del antiguo y medio malayalam. [60] Además, eliminó las letras sobrantes e innecesarias de la escritura modificada. [60] Por lo tanto, a Ezhuthachan también se le conoce como el padre del malayalam moderno . [60] El desarrollo de la escritura malayalam moderna también estuvo fuertemente influenciado por la escritura tigalari , que se usaba para escribir sánscrito , debido a la influencia de los brahmanes tuluva en Kerala. [60] El idioma utilizado en las obras de malayalam árabe del siglo XVI al XVII d. C. es una mezcla de malayalam moderno y árabe . [60] Siguen la sintaxis del malabar moderno, aunque escritos en una forma modificada de escritura árabe , que se conoce como escritura malabar árabe . [60] P. Shangunny Menon atribuye la autoría de la obra medieval Keralolpathi , que describe la leyenda de Parashurama y la partida del último rey Cheraman Perumal a La Meca , a Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan. [64]

Kunchan Nambiar introdujo una nueva forma literaria llamada Thullal , y Unnayi Variyar introdujo reformas en la literatura Attakkatha . [60] La imprenta, la literatura en prosa y el periodismo malayalam se desarrollaron después de la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII d. C. Los movimientos literarios modernos en la literatura malayalam comenzaron a fines del siglo XIX con el surgimiento del famoso Triunvirato Moderno formado por Kumaran Asan , [65] Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer [66] y Vallathol Narayana Menon . [67] En la segunda mitad del siglo XX, poetas y escritores ganadores del Jnanpith como G. Sankara Kurup , SK Pottekkatt , Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai , MT Vasudevan Nair , ONV Kurup y Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri , habían hecho valiosas contribuciones a la literatura malayalam moderna. [68] [69] [70] [71] [72] La vida y las obras de Edasseri Govindan Nair han asumido una mayor importancia socioliteraria después de su muerte y Edasseri ahora es reconocido como un importante poeta de Malayalam. [73] Más tarde, escritores como OV Vijayan , Kamaladas , M. Mukundan , Arundhati Roy y Vaikom Muhammed Basheer , han ganado reconocimiento internacional. [74] [75] [76] El malayalam también ha tomado prestadas muchas de sus palabras de varios idiomas extranjeros: principalmente de los idiomas semíticos , incluido el árabe , y los idiomas europeos , incluido el holandés y el portugués , debido a la larga herencia del comercio del Océano Índico y la colonización portuguesa-holandesa de la costa de Malabar . [32] [60]

Se pueden observar variaciones en los patrones de entonación , vocabulario y distribución de elementos gramaticales y fonológicos según los parámetros de región, religión, comunidad, ocupación, estrato social, estilo y registro.

Según la Enciclopedia Dravidiana, los dialectos regionales del malabar pueden dividirse en quince áreas dialectales. [77] Son las siguientes:

Según Ethnologue, los dialectos son: [31] Malabar, Nagari-Malayalam, Kerala del Norte, Kerala Central, Kerala del Sur, Kayavar, Namboodiri , Nair , Mappila , Beary , Jeseri , Yerava , Pulaya, Nasrani y Kasargod . Los dialectos comunitarios son: Namboodiri , Nair , Arabi Malayalam , Pulaya y Nasrani . [31] Mientras que los dialectos Namboothiri y Nair tienen una naturaleza común, el Arabi Malayalam es uno de los dialectos más divergentes, diferenciándose considerablemente del Malayalam literario. [31] Jeseri es un dialecto del Malayalam hablado principalmente en el territorio de la Unión de Lakshadweep y Beary se habla en Tulu Nadu , que están más cerca de Kerala. De los 33.066.392 hablantes de malayalam en la India en 2001, 33.015.420 hablaban los dialectos estándar, 19.643 hablaban el dialecto Yerava y 31.329 hablaban variaciones regionales no estándar como el Eranadan . [78]

Los dialectos del malabar hablados en distritos como Kasaragod , Kannur , Wayanad , Kozhikode y Malappuram en el antiguo distrito de Malabar tienen pocas influencias del kannada . [32] Por ejemplo, las palabras que comienzan con el sonido "V" en malabar se convierten en "B" en estos distritos como en kannada . [32] Además, la aproximante retrofleja sonora (/ɻ/) que se ve tanto en tamil como en la forma estándar del malabar, no se ve en los dialectos del norte del malabar, como en kannada . [32] Por ejemplo, las palabras Vazhi (Camino), Vili (Llamado), Vere (Otro) y Vaa (Ven/Boca), se convierten en Bayi , Bili , Bere y Baa en los dialectos del norte del malabar. [32] De manera similar, el malabar que se habla en los distritos del sur de Kerala, es decir, la zona de Thiruvananthapuram - Kollam - Pathanamthitta , está influenciado por el tamil. [32]

Las etiquetas como "dialecto nampoothiri", "dialecto mappila" y "dialecto nasrani" hacen referencia a patrones generales constituidos por los subdialectos hablados por las subcastas o subgrupos de cada una de esas castas. Las características más destacadas de los principales dialectos comunales del malabar se resumen a continuación:

El malabar ha incorporado muchos elementos de otros idiomas a lo largo de los años, siendo los más notables el sánscrito y, más tarde, el inglés. [85] Según Sooranad Kunjan Pillai , que compiló el léxico autorizado del malabar, los otros idiomas principales cuyo vocabulario se incorporó a lo largo de los siglos fueron el árabe , el holandés , el indostánico , el pali , el persa , el portugués , el prácrito y el siríaco . [86]

El malabar es una lengua hablada por los pueblos nativos del suroeste de la India y las islas de Lakshadweep en el mar Arábigo . Según el censo indio de 2011, había 32.413.213 hablantes de malabar en Kerala, lo que representa el 93,2% del número total de hablantes de malabar en la India y el 97,03% de la población total del estado. Había otros 701.673 (1,14% del número total) en Karnataka , 957.705 (2,70%) en Tamil Nadu y 406.358 (1,2%) en Maharashtra .

El número de hablantes de malabar en Lakshadweep es de 51.100, lo que supone solo el 0,15% del número total, pero supone aproximadamente el 84% de la población de Lakshadweep. El malabar era el idioma más hablado en el antiguo taluk de Gudalur (ahora taluks de Gudalur y Panthalur) del distrito de Nilgiris en Tamil Nadu, que representa el 48,8% de la población, y era el segundo idioma más hablado en los taluks de Mangalore y Puttur de South Canara, que representan el 21,2% y el 15,4% respectivamente, según el informe del censo de 1951. [89] El 25,57% de la población total del distrito de Kodagu de Karnataka son malabaristas , y forman el grupo lingüístico más grande, representando el 35,5% en el taluk de Virajpet . [90] Alrededor de un tercio de los malayos del distrito de Kodagu hablan el dialecto Yerava según el censo de 2011, que es nativo de Kodagu y Wayanad . [90]

En total, los malayalis constituían el 3,22% de la población total de la India en 2011. De los 34.713.130 hablantes de malayalam en la India en 2011, 33.015.420 hablaban los dialectos estándar, 19.643 hablaban el dialecto Yerava y 31.329 hablaban variaciones regionales no estándar como Eranadan . [91] Según los datos del censo de 1991, el 28,85% de todos los hablantes de malayalam en la India hablaban una segunda lengua y el 19,64% del total conocía tres o más idiomas.

Justo antes de la independencia, Malasia atrajo a muchos malayalis. Un gran número de ellos se han establecido en Chennai , Bengaluru , Mangaluru , Hyderabad , Mumbai , Navi Mumbai , Pune , Mysuru y Delhi . Muchos malayalis también han emigrado a Oriente Medio , Estados Unidos y Europa. Había 179.860 hablantes de malabar en los Estados Unidos, según el censo de 2000, con las mayores concentraciones en el condado de Bergen, Nueva Jersey , y el condado de Rockland, Nueva York . [92] Hay 144.000 hablantes de malabar en Malasia . [ cita requerida ] Había 11.687 hablantes de malabar en Australia en 2016. [93] El censo canadiense de 2001 informó de 7.070 personas que indicaron el malabar como su lengua materna, principalmente en Toronto . El censo de Nueva Zelanda de 2006 informó de 2.139 hablantes. [94] En 1956 se informó de la existencia de 134 hogares de habla malayalam en Fiji . También hay una considerable población malayalam en las regiones del Golfo Pérsico , especialmente en Dubai y Doha .

Para las consonantes y vocales, se da el símbolo del Alfabeto Fonético Internacional (IPA), seguido del carácter malayalam y la transliteración ISO 15919. [96] La escritura malayalam actual tiene una gran similitud con la escritura tigalari , que se usaba para escribir el idioma tulu , hablado en la costa de Karnataka ( distritos de Dakshina Kannada y Udupi ) y el distrito más septentrional de Kasargod en Kerala. [21] La escritura tigalari también se usaba para escribir sánscrito en la región de Malabar .

El malabar también ha tomado prestados los diptongos sánscritos / ai̯/ (representados en malabar como ഐ , ai) y /au̯/ (representados en malabar como ഔ , au), aunque estos aparecen principalmente solo en préstamos sánscritos. Tradicionalmente (como en sánscrito), cuatro consonantes vocálicas (generalmente pronunciadas en malabar como consonantes seguidas de saṁvr̥tōkāram , que no es oficialmente una vocal, y no como consonantes vocálicas reales) se han clasificado como vocales: r vocálica ( ഋ , /rɨ̆/ , r̥), r vocálica larga ( ൠ , /rɨː/ , r̥̄), l vocálica ( ഌ , /lɨ̆/ , l̥) y l vocálica larga ( ൡ , /lɨː/ , l̥̄). A excepción de la primera, las otras tres se han omitido de la escritura actual utilizada en Kerala, ya que no hay palabras en el malabar actual que las utilicen.

Algunos autores dicen que el malabar no tiene diptongos y que /ai̯, au̯/ son grupos de V+glide j/ʋ [19] mientras que otros consideran que todos los grupos de V+glide son diptongos /ai̯, aːi̯, au̯, ei̯, oi̯, i̯a/ como en kai, vāypa, auṣadhaṁ, cey, koy y kāryaṁ [96]

La longitud de las vocales es fonémica y todas las vocales tienen pares mínimos, por ejemplo , kaṭṭi "grosor", kāṭṭi "mostró", koṭṭi "golpeó", kōṭṭi "retorcido, palo, canica", er̠i "arrojar", ēr̠i "lotes" [96]

Algunos hablantes también tienen /æː/, /ɔː/, /ə/ de préstamos lingüísticos, por ejemplo /bæːŋgɨ̆/ "banco", pero la mayoría de los hablantes lo reemplazan con /aː/, /eː/ o /ja/; /oː/ o /aː/ y /e/ o /a/. [19]

El siguiente texto es el Artículo 1 de la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos .

Todos los seres humanos nacen libres e iguales en dignidad y derechos y, dotados como están de razón y conciencia, deben comportarse fraternalmente los unos con los otros.

മനുഷ്യരെല്ലാവരും തുലvase സോടും സ്വാതന്ത്ര്യത്തോടുംകൂടി ജനിച്ചിട്ടുള്ളവരാണ്. Más información മനുഷ്യനം മനസാക്ഷിയും സിദ്ധമായിരിക്കുന്നത്.

manuṣyarellāvaruṁ tulyāvakāśaṅṅaḷōṭuṁ antassōṭuṁ svātantryattōṭuṅkūṭi janicciṭṭuḷḷavarāṇŭ. anyōnyaṁ bhrātr̥bhāvattōṭe perumāṟuvānāṇŭ manuṣyanŭ vivēkabuddhiyuṁ manasākṣiyuṁ siddhamāyirikkunnatŭ.

/manuʂjaɾellaːʋaɾum t̪uljaːʋakaːʃaŋŋaɭoːʈum an̪t̪assoːʈum sʋaːt̪an̪tɾjat̪t̪oːʈuŋkuːʈi d͡ʒanit͡ʃt͡ʃiʈʈuɭɭa ʋaɾaːɳɨ̆ ǁ anjoːnjam bʱraːt̪rɨ̆bʱaːʋat̪t̪oːʈe peɾumaːruʋaːnaːɳɨ̆ manuʂjanɨ̆ ʋiʋeːkabud̪d̪ʱijum manasaːkʂijum sid̪d̪ʱamaːjiɾikkun̪ːat̪ɨ̆ ǁ/

El orden de palabras canónico del malabarismo es SOV (sujeto-objeto-verbo), al igual que otras lenguas dravídicas . [106] Un orden de palabras OSV poco común se da en las cláusulas interrogativas cuando la palabra interrogativa es el sujeto. [107] Tanto los adjetivos como los adjetivos posesivos preceden a los sustantivos que modifican. El malabarismo tiene 6 [108] o 7 [109] [ ¿fuente poco fiable? ] casos gramaticales . Los verbos se conjugan para el tiempo, el modo y el aspecto, pero no para la persona, el género ni el número, excepto en el lenguaje arcaico o poético. La gramática malabarismo moderna se basa en el libro Kerala Panineeyam escrito por AR Raja Raja Varma a finales del siglo XIX d. C. [22]

A continuación se presentan los paradigmas declinacionales de algunos sustantivos y pronombres comunes. Como el malabar es una lengua aglutinante, es difícil delimitar los casos de forma estricta y determinar cuántos hay, aunque el número generalmente aceptado es siete u ocho. Las oclusivas alveolares y nasales (aunque la escritura malabar moderna no distingue estas últimas de la nasal dental ) están subrayadas para mayor claridad, siguiendo la convención de romanización de la Biblioteca Nacional de Calcuta .

Las formas vocativas se dan entre paréntesis después del nominativo , ya que los únicos vocativos pronominales que se utilizan son los de tercera persona, que solo aparecen en compuestos.

Los siguientes son ejemplos de algunos de los patrones de declinación más comunes.

Cuando se adoptan palabras del sánscrito, sus terminaciones suelen cambiarse para adaptarse a las normas del malayalam:

Además de la escritura malayalam, el idioma malayalam se ha escrito en otras escrituras como el latín , el siríaco [112] [81] [82] y el árabe . El malayalam suriyani fue utilizado por los cristianos de Santo Tomás (también conocidos como nasranis) hasta el siglo XIX. [112] [81] [82] Las escrituras árabes en particular se enseñaban en las madrasas de Kerala y las islas Lakshadweep . [113] [114]

.jpg/440px-Malayalam_board_with_old_style_Malayalam_letter_(cropped).jpg)

Históricamente, se utilizaron varias escrituras para escribir malabar. Entre ellas se encontraban las escrituras vatteluttu, kolezhuthu y malayanma . Pero fue la escritura grantha , otra variación del brahmi meridional , la que dio origen a la escritura malabar moderna . La escritura malabar moderna tiene una gran similitud con la escritura tigalari , que se utilizó para escribir el idioma tulu en la costa de Karnataka ( distritos de Dakshina Kannada y Udupi ) y el distrito más septentrional de Kasaragod en Kerala. [21] Es silábica en el sentido de que la secuencia de elementos gráficos significa que las sílabas deben leerse como unidades, aunque en este sistema los elementos que representan vocales y consonantes individuales son en su mayor parte fácilmente identificables. En la década de 1960, el malabar prescindió de muchas letras especiales que representaban consonantes conjuntas menos frecuentes y combinaciones de la vocal /u, u:/ con diferentes consonantes.

La escritura malayalam consta de un total de 578 caracteres. La escritura contiene 52 letras, incluidas 16 vocales y 36 consonantes, que forman 576 caracteres silábicos, y contiene dos caracteres diacríticos adicionales llamados anusvāra y visarga . [115] [116] El estilo de escritura anterior ha sido reemplazado por un nuevo estilo a partir de 1981. Esta nueva escritura reduce las diferentes letras para la composición tipográfica de 900 a menos de 90. Esto se hizo principalmente para incluir el malayalam en los teclados de las máquinas de escribir y las computadoras.

En 1999, un grupo llamado "Rachana Akshara Vedi" produjo un conjunto de fuentes gratuitas que contenían todo el repertorio de caracteres de más de 900 glifos . Esto se anunció y lanzó junto con un editor de texto en Thiruvananthapuram , la capital de Kerala , ese mismo año . En 2004, las fuentes fueron lanzadas bajo la licencia GPL por Richard Stallman de la Free Software Foundation en la Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de Cochin en Kochi, Kerala.

Un chillu ( ചില്ല് , cillŭ ), o un chillaksharam ( ചില്ലക്ഷരം , cillakṣaram ), es una letra consonántica especial que representa una consonante pura de forma independiente, sin la ayuda de un virama . A diferencia de una consonante representada por una letra consonante ordinaria, esta consonante nunca es seguida por una vocal inherente. Anusvara y visarga encajan en esta definición, pero no suelen incluirse. ISCII y Unicode 5.0 tratan a un chillu como una variante de glifo de una letra consonante normal ("base"). [117] En Unicode 5.1 y posteriores, las letras chillu se tratan como caracteres independientes, codificados atómicamente.

Los números y fracciones malayalam se escriben de la siguiente manera. Estos son arcaicos y ya no se utilizan. En su lugar, se sigue el sistema de numeración hindú-arábigo común . Existe una confusión sobre el glifo del dígito malayalam cero. La forma correcta es ovalada, pero en ocasiones el glifo de 1 ⁄ 4 ( ൳ ) se muestra erróneamente como el glifo de 0.

El número "11" se escribe "൰൧" y no "൧൧". El "32" se escribe "൩൰൨", similar al sistema numérico tamil .

Por ejemplo, el número "2013" se lee en malayalam como രണ്ടായിരത്തി പതിമൂന്ന് ( raṇḍāyiratti padimūnnŭ ). Se divide en:

Combínalos para obtener el número malayalam ൨൲൰൩ . [118]

Y 1,00,000 como " ൱൲ " = cien( ൱ ), mil( ൲ ) (100×1000), 10,00,000 como " ൰൱൲ " = diez( ൰ ), cien( ൱ ), mil( ൲ ) (10×100×1000) y 1,00,00,000 como " ൱൱൲ " = cien( ൱ ), cien( ൱ ), mil( ൲ ) (100×100×1000).

Más tarde, este sistema se reformó para que fuera más similar a los numerales hindúes-arábigos , de modo que 10.00.000 en los numerales reformados sería ൧൦൦൦൦൦൦. [119]

En malayalam se puede transcribir cualquier fracción añadiendo ( -il ) después del denominador seguido del numerador, por lo que una fracción como 7 ⁄ 10 se leería como പത്തിൽ ഏഴ് ( pattil ēḻŭ ) 'de diez, siete' pero fracciones como 1 ⁄ 2 1 ⁄ 4 y 3 ⁄ 4 tienen nombres distintos ( ara , kāl , mukkāl ) y 1 ⁄ 8 ( arakkāl ) 'medio cuarto'. [119]

Vatteluttu ( malayalam : വട്ടെഴുത്ത് , Vaṭṭezhuthŭ , "escritura redonda") es una escritura que evolucionó a partir del tamil-brahmi y que alguna vez se usó ampliamente en la parte sur del actual Tamil Nadu y en Kerala .

El malabar se escribió por primera vez en vattezhuthu. La inscripción Vazhappally emitida por Rajashekhara Varman es el ejemplo más antiguo, que data de alrededor del año 830 d. C. [120] [121] Durante el período medieval, la escritura tigalari que se usaba para escribir tulu en el sur de Canara y sánscrito en la región adyacente de Malabar , tenía una gran similitud con la escritura malabar moderna. [21] En el país tamil, la escritura tamil moderna había suplantado a vattezhuthu en el siglo XV, pero en la región de Malabar , vattezhuthu siguió siendo de uso general hasta el siglo XVII [122] o el siglo XVIII. [123] Una forma variante de esta escritura, kolezhuthu , se usó hasta aproximadamente el siglo XIX, principalmente en el área de Malabar - Cochin . [124]

El vatteluttu era de uso general, pero no era adecuado para la literatura en la que se utilizaban muchas palabras sánscritas. Al igual que el tamil-brahmi, se utilizó originalmente para escribir tamil y, como tal, no tenía letras para las consonantes sonoras o aspiradas que se utilizan en sánscrito pero no en tamil. Por esta razón, el vatteluttu y el alfabeto Grantha a veces se mezclaban, como en el Manipravalam . Uno de los ejemplos más antiguos de la literatura del Manipravalam, el vaishikatantram ( വൈശികതന്ത്രം , vaiśikatantram ), se remonta al siglo XII, [125] [126] donde se utilizó la forma más antigua de la escritura malayalam, que parece haber sido sistematizada hasta cierto punto en la primera mitad del siglo XIII. [120] [123]

Otra variante, la malayanma , se utilizó en el sur de Thiruvananthapuram . [124] En el siglo XIX, las escrituras antiguas como Kolezhuthu habían sido suplantadas por Arya-eluttu, que es la escritura malayalam actual. Hoy en día, se utiliza ampliamente en la prensa de la población malayali en Kerala. [127]

Según Arthur Coke Burnell , una forma del alfabeto Grantha, originalmente utilizado en la dinastía Chola , fue importada a la costa suroeste de la India en el siglo VIII o IX, que luego se modificó con el tiempo en esta área aislada, donde la comunicación con la costa este era muy limitada. [128] Más tarde evolucionó a la escritura tigalari-malayalam que utilizaron los pueblos malayali , brahmanes havyaka y brahmanes tulu, pero originalmente solo se aplicaba para escribir sánscrito . Esta escritura se dividió en dos escrituras: tigalari y malayalam. Mientras que la escritura malayalam se extendió y modificó para escribir malayalam en lengua vernácula, el tigalari se escribió solo para sánscrito. [128] [129] En Malabar, este sistema de escritura se denominó Arya-eluttu ( ആര്യ എഴുത്ത് , Ārya eḻuttŭ ), [130] que significa "escritura Arya" (el sánscrito es una lengua indo-aria , mientras que el malayalam es una lengua dravídica ).

Suriyani Malayalam ( സുറിയാനി മലയാളം , third Cristianos ( también conocidos como cristianos sirios ) . o Nasranis) de Kerala en India . [131] [112] [81] [82] Utiliza gramática malayalam, la escritura maḏnḥāyā o siríaca "oriental" con características ortográficas especiales y vocabulario del malayalam y siríaco oriental. Se originó en la región del sur de la India, en la costa de Malabar (actualmente Kerala). Hasta el siglo XX, la escritura fue ampliamente utilizada por los cristianos sirios en Kerala.

La escritura árabe malayalam , también conocida como escritura Ponnani , [132] [133] [134] es un sistema de escritura (una variante de la escritura árabe con características ortográficas especiales ) que se desarrolló durante el período medieval temprano y se utilizó para escribir árabe malayalam hasta principios del siglo XX d. C. [135] [136] Aunque la escritura se originó y se desarrolló en Kerala , hoy en día se utiliza predominantemente en Malasia y Singapur por la comunidad musulmana migrante . [137] [138]

La literatura Sangam puede considerarse como el predecesor antiguo del malabar. [42] Según Iravatham Mahadevan , la inscripción malabar más antigua descubierta hasta ahora es la inscripción Edakal-5 (aproximadamente finales del siglo IV - principios del siglo V) que dice ī pazhama ( trad. 'esto es antiguo'). [139] Aunque esto ha sido disputado por muchos eruditos que lo consideran un dialecto regional del tamil antiguo. [140] El uso del pronombre ī y la falta de la terminación -ai del tamil literario son arcaísmos del protodravidiano en lugar de innovaciones únicas del malabar. [nota 3]

La literatura temprana del malayalam comprendía tres tipos de composiciones: [60] Nada malayalam, Nada tamil y Nada sánscrito. [60]

Malayalam literature has been profoundly influenced by poets Cherusseri Namboothiri,[143][60] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan,[60] and Poonthanam Nambudiri,[60][144] in the 15th and the 16th centuries of Common Era.[60][145] Unnayi Variyar, a probable 17th–18th century poet,[146] and Kunchan Nambiar, a poet of 18th century,[147] also greatly influenced Malayalam literature in its early form.[60] The words used in many of the Arabi Malayalam works those date back to 16th–17th centuries of Common Era are also very closer to the modern Malayalam language.[60][148] The prose literature, criticism, and Malayalam journalism began after the latter half of 18th century CE. Contemporary Malayalam literature deals with social, political, and economic life context. The tendency of the modern poetry is often towards political radicalism.[149] Malayalam literature has been presented with six Jnanapith awards, the second-most for any Dravidian language and the third-highest for any Indian language.[150][151]

Malayalam poetry to the late 20th century betrays varying degrees of the fusion of the three different strands. The oldest examples of Pattu and Manipravalam, respectively, are Ramacharitam and Vaishikatantram, both from the 12th century.[152][60]

The earliest extant prose work in the language is a commentary in simple Malayalam, Bhashakautalyam (12th century) on Chanakya's Arthashastra. Adhyatmaramayanam by Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan (known as the father of modern Malayalam literature) who was born in Tirur, one of the most important works in Malayalam literature. Unnunili Sandesam written in the 14th century is amongst the oldest literary works in Malayalam language.[153] Cherusseri Namboothiri of 15th century (Kannur-based poet), Poonthanam Nambudiri of 16th century (Perinthalmanna-based poet), Unnayi Variyar of 17th–18th centuries (Thrissur-based poet), and Kunchan Nambiar of 18th century (Palakkad-based poet), have played a major role in the development of Malayalam literature into current form.[60] The words used in many of the Arabi Malayalam works, which dates back to 16th–17th centuries are also very closer to modern Malayalam language.[60] The basin of the river Bharathappuzha, which is otherwise known as River Ponnani, and its tributaries, have played a major role in the development of modern Malayalam Literature.[154][60]

By the end of the 18th century some of the Christian missionaries from Kerala started writing in Malayalam but mostly travelogues, dictionaries and religious books. Varthamanappusthakam (1778), written by Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar[155] is considered to be the first travelogue in an Indian language. The modern Malayalam grammar is based on the book Kerala Panineeyam written by A. R. Raja Raja Varma in late 19th century CE.[22]

For the first 600 years of the Malayalam calendar, Malayalam literature remained in a preliminary stage. During this time, Malayalam literature consisted mainly of various genres of songs (Pattu).[60] Folk songs are the oldest literary form in Malayalam.[22] They were just oral songs.[22] Many of them were related to agricultural activities, including Pulayar Pattu, Pulluvan Pattu, Njattu Pattu, Koythu Pattu, etc.[22] Other Ballads of Folk Song period include the Vadakkan Pattukal (Northern songs) in North Malabar region and the Thekkan Pattukal (Southern songs) in Southern Travancore.[22] Some of the earliest Mappila songs (Muslim songs) were also folk songs.[22]

The earliest known poems in Malayalam, Ramacharitam and Thirunizhalmala, dated to the 12th to 14th century, were completed before the introduction of the Sanskrit alphabet. It was written by a poet with the pen name Cheeramakavi who, according to poet Ulloor S Parameswara Iyer, was Sree Veerarama Varman, a king of southern Kerala from AD 1195 to 1208.[156] However the claim that it was written in Southern Kerala is expired on the basis of new discoveries.[157] Other experts, like Chirakkal T Balakrishnan Nair, K.M. George, M. M. Purushothaman Nair, and P.V. Krishnan Nair, state that the origin of the book is in Kasaragod district in North Malabar region.[157] They cite the use of certain words in the book and also the fact that the manuscript of the book was recovered from Nileshwaram in North Malabar.[158] The influence of Ramacharitam is mostly seen in the contemporary literary works of Northern Kerala.[157] The words used in Ramacharitam such as Nade (Mumbe), Innum (Iniyum), Ninna (Ninne), Chaaduka (Eriyuka) are special features of the dialect spoken in North Malabar (Kasaragod-Kannur region).[157] Furthermore, the Thiruvananthapuram mentioned in Ramacharitham is not the Thiruvananthapuram in Southern Kerala.[157] But it is Ananthapura Lake Temple of Kumbla in the northernmost Kasaragod district of Kerala.[157] The word Thiru is used just by the meaning Honoured.[157] Today it is widely accepted that Ramacharitham was written somewhere in North Malabar (most likely near Kasaragod).[157]

But the period of the earliest available literary document cannot be the sole criterion used to determine the antiquity of a language. In its early literature, Malayalam has songs, Pattu, for various subjects and occasions, such as harvesting, love songs, heroes, gods, etc. A form of writing called Campu emerged from the 14th century onwards. It mixed poetry with prose and used a vocabulary strongly influenced by Sanskrit, with themes from epics and Puranas.[47]

The works including Unniyachi Charitham, Unnichirudevi Charitham, and Unniyadi Charitham, are written in Middle Malayalam, those date back to 13th and 14th centuries of Common Era.[60][32] The Sandesha Kavyas of 14th century CE written in Manipravalam language include Unnuneeli Sandesam[60][32] The literary works written in Middle Malayalam were heavily influenced by Sanskrit and Prakrit, while comparing them with the modern Malayalam literature.[60][32] The word Manipravalam literally means Diamond-Coral or Ruby-Coral. The 14th-century Lilatilakam text states Manipravalam to be a Bhashya (language) where "Malayalam and Sanskrit should combine together like ruby and coral, without the least trace of any discord".[62][63] The Champu Kavyas written by Punam Nambudiri, one among the Pathinettara Kavikal (Eighteen and a half poets) in the court of the Zamorin of Calicut, also belong to Middle Malayalam.[32][60]

The poem Krishnagatha written by Cherusseri Namboothiri, who was the court poet of the king Udaya Varman Kolathiri (1446–1475) of Kolathunadu, is written in modern Malayalam.[60] The language used in Krishnagatha is the modern spoken form of Malayalam.[60] It appears to be the first literary work written in the present-day language of Malayalam.[60] During the 16th century CE, Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan from the Kingdom of Tanur and Poonthanam Nambudiri from the Kingdom of Valluvanad followed the new trend initiated by Cherussery in their poems. The Adhyathmaramayanam Kilippattu and Mahabharatham Kilippattu written by Ezhuthachan and Jnanappana written by Poonthanam are also included in the earliest form of Modern Malayalam.[60] The words used in most of the Arabi Malayalam works, which dates back to 16th–17th centuries, are also very closer to modern Malayalam language.[60] P. Shangunny Menon ascribes the authorship of the medieval work Keralolpathi, which describes the Parashurama legend and the departure of the final Cheraman Perumal king to Mecca, to Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan.[64]

Kunchan Nambiar, the founder of Thullal movement, was a prolific literary figure of the 18th century.[60]

The British printed Malabar English Dictionary[159] by Graham Shaw in 1779 was still in the form of a Tamil-English Dictionary.[160] Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar wrote the first Malayalam travelogue called Varthamanappusthakam in 1789.

Hermann Gundert, (1814–1893), a German missionary and scholar of exceptional linguistic talents, played a distinguishable role in the development of Malayalam literature. His major works are Keralolpathi (1843), Pazhancholmala (1845), Malayalabhaasha Vyakaranam (1851), Paathamala (1860) the first Malayalam school text book, Kerala pazhama (1868), the first Malayalam dictionary (1872), Malayalarajyam (1879) – Geography of Kerala, Rajya Samacharam (1847 June) the first Malayalam news paper, Paschimodayam (1879) – Magazine.[161] He lived in Thalassery for around 20 years. He learned the language from well established local teachers Ooracheri Gurukkanmar from Chokli, a village near Thalassery and consulted them in works. He also translated the Bible into Malayalam.[162][163]

In 1821, the Church Mission Society (CMS) at Kottayam in association with the Syriac Orthodox Church started a seminary at Kottayam in 1819 and started printing books in Malayalam when Benjamin Bailey, an Anglican priest, made the first Malayalam types. In addition, he contributed to standardizing the prose.[164] Hermann Gundert from Stuttgart, Germany, started the first Malayalam newspaper, Rajya Samacaram in 1847 at Talasseri. It was printed at Basel Mission.[165] Malayalam and Sanskrit were increasingly studied by Christians of Kottayam and Pathanamthitta. The Marthomite movement in the mid-19th century called for replacement of Syriac by Malayalam for liturgical purposes. By the end of the 19th century Malayalam replaced Syriac as language of Liturgy in all Syrian Christian churches.

Vengayil Kunhiraman Nayanar, (1861–1914) from Thalassery was the author of first Malayalam short story, Vasanavikriti. After him innumerable world class literature works by was born in Malayalam.[60]

O. Chandu Menon wrote his novels "Indulekha" and "Saradha" while he was the judge at Parappanangadi Munciff Court. Indulekha is also the first Major Novel written in Malayalam language.[166]

.[60]

The third quarter of the 19th century CE bore witness to the rise of a new school of poets devoted to the observation of life around them and the use of pure Malayalam. The major poets of the Venmani School were Venmani Achhan Nambudiripad (1817–1891), Venmani Mahan Nambudiripad (1844–1893), Poonthottam Achhan Nambudiri (1821–1865), Poonthottam Mahan Nambudiri (1857–1896) and the members of the Kodungallur Kovilakam (Royal Family) such as Kodungallur Kunjikkuttan Thampuran. The style of these poets became quite popular for a while and influenced even others who were not members of the group like Velutheri Kesavan Vaidyar (1839–1897) and Perunlli Krishnan Vaidyan (1863–1894). The Venmani school pioneered a style of poetry that was associated with common day themes, and the use of pure Malayalam (Pachcha Malayalam) rather than Sanskrit.[60]

In the second half of the 20th century, Jnanpith winning poets and writers like G. Sankara Kurup, S. K. Pottekkatt, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, M. T. Vasudevan Nair, O. N. V. Kurup, Edasseri Govindan Nair and Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri, had made valuable contributions to the modern Malayalam literature.[68][69][70][71][72] Later, writers like O. V. Vijayan, Kamaladas, M. Mukundan, Arundhati Roy, and Vaikom Muhammed Basheer, have gained international recognition.[74][75][76][167]

The travelogues written by S. K. Pottekkatt were turning point in the travelogue literature.[60] The writers like Kavalam Narayana Panicker have contributed much to Malayalam drama.[22]

Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai turned away from party politics and produced a moving romance in Chemmeen (Shrimps) in 1956. For S. K. Pottekkatt and Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, who had not dabbled in politics, the continuity is marked in the former's Vishakanyaka (Poison Maid, 1948) and the latter's Ntuppuppakkoranendarnnu (My Grandpa had an Elephant, 1951). The non-political social or domestic novel was championed by P. C. Kuttikrishnan (Uroob) with his Ummachu (1955) and Sundarikalum Sundaranmarum (Men and Women of Charm, 1958).[60]

In 1957 Basheer's Pathummayude Aadu (Pathumma's Goat) brought in a new kind of prose tale, which perhaps only Basheer could handle with dexterity. The fifties thus mark the evolution of a new kind of fiction, which had its impact on the short stories as well. This was the auspicious moment for the entry of M. T. Vasudevan Nair and T. Padmanabhan upon the scene. Front runners in the post-modern trend include Kakkanadan, O. V. Vijayan, E. Harikumar, M. Mukundan and Anand.[60]

Kerala has the highest media exposure in India with newspapers publishing in nine languages, mainly English and Malayalam.[168][169]

Contemporary Malayalam poetry deals with social, political, and economic life context. The tendency of the modern poetry is often towards political radicalism.[149]

Malayalam is spoken along the Malabar coast, on the western side of the Ghauts, or Malaya range of mountains, from the vicinity of Kumbla near Mangalore, where it supersedes Tuļu, to Kanyakumari, where it begins to be superseded by Tamil. (Pages 6, 16, 20, 31)

Per Barbosa, Malabar begins at the point where the kingdom of Narasyngua or Vijayanagar ends, that is at Cumbola (Cambola) on the Chandragiri river.

This Bungalow in Tellicherry ... was the residence of Dr. Herman Gundert .He lived here for 20 years