La medicina tradicional china ( MTC ) es una práctica médica alternativa derivada de la medicina tradicional china. Una gran parte de sus afirmaciones son pseudocientíficas y la mayoría de los tratamientos no tienen evidencia sólida de su eficacia ni de su mecanismo de acción lógico . [1] [2]

La medicina tradicional china abarcaba una variedad de prácticas de salud y curación que a veces competían entre sí, creencias populares , teoría literaria y filosofía confuciana , remedios herbales , alimentos , dietas, ejercicios, especializaciones médicas y escuelas de pensamiento. [3] La medicina tradicional china tal como existe hoy en día ha sido descrita como una invención en gran parte del siglo XX. [4] A principios del siglo XX, los modernizadores culturales y políticos chinos trabajaron para eliminar las prácticas tradicionales por considerarlas atrasadas y poco científicas. Luego, los practicantes tradicionales seleccionaron elementos de filosofía y práctica y los organizaron en lo que llamaron "medicina china" (chino: 中医Zhongyi ). [5] En la década de 1950, el gobierno chino buscó revivir la medicina tradicional (incluida la legalización de prácticas previamente prohibidas) y patrocinó la integración de la medicina tradicional china y la medicina occidental, [6] [7] y en la Revolución Cultural de la década de 1960, promovió la medicina tradicional china como barata y popular. [8] La creación de la medicina tradicional china moderna fue encabezada en gran medida por Mao Zedong , a pesar del hecho de que no creía en su eficacia. [4] Tras la apertura de las relaciones entre Estados Unidos y China después de 1972, hubo un gran interés en Occidente por lo que hoy se llama medicina tradicional china (MTC). [9]

Se dice que la MTC se basa en textos como Huangdi Neijing (El canon interno del Emperador Amarillo), [10] y Compendio de Materia Médica , una obra enciclopédica del siglo XVI, e incluye varias formas de medicina herbal , acupuntura , terapia con ventosas , gua sha , masaje (tui na) , huesero (die-da) , ejercicio (qigong) y terapia dietética. La MTC se usa ampliamente en la Sinosfera . Uno de los principios básicos es que el qi del cuerpo circula a través de canales llamados meridianos que tienen ramas conectadas a los órganos y funciones corporales. [11] No hay evidencia de que existan meridianos o energía vital. Los conceptos del cuerpo y de la enfermedad utilizados en la MTC reflejan sus orígenes antiguos y su énfasis en los procesos dinámicos sobre la estructura material, similar a la teoría humoral de la antigua Grecia y la antigua Roma . [12]

La demanda de medicinas tradicionales en China ha sido un importante generador de contrabando ilegal de vida silvestre , vinculado a la matanza y el contrabando de animales en peligro de extinción . [13] Sin embargo, en los últimos años las autoridades chinas han tomado medidas enérgicas contra el contrabando ilegal de vida silvestre, y la industria ha recurrido cada vez más a alternativas cultivadas. [14] [15]

Los estudiosos de la historia de la medicina en China distinguen sus doctrinas y prácticas de las de la medicina tradicional china actual. JA Jewell y SM Hillier afirman que el término "medicina tradicional china" se convirtió en un término establecido debido al trabajo del Dr. Kan-Wen Ma, un médico formado en Occidente que fue perseguido durante la Revolución Cultural y emigró a Gran Bretaña, donde se unió al Instituto Wellcome de Historia de la Medicina de la Universidad de Londres . [16] Ian Johnson dice, por otro lado, que el término en inglés "medicina tradicional china" fue acuñado por "propagandistas del partido" en 1955. [17]

Nathan Sivin critica los intentos de tratar la medicina y las prácticas médicas en la China tradicional como si fueran un solo sistema. En cambio, dice, hubo 2.000 años de "sistema médico en crisis" y habla de un "mito de una tradición médica inmutable". Insiste en que "traducir la medicina tradicional puramente en términos de medicina moderna se vuelve en parte absurdo, en parte irrelevante y en parte erróneo; lo mismo es cierto al revés, un punto que se pasa por alto fácilmente". [18] TJ Hinrichs observa que la gente en las sociedades occidentales modernas divide las prácticas curativas en biomedicina para el cuerpo, psicología para la mente y religión para el espíritu, pero estas distinciones son inadecuadas para describir los conceptos médicos entre los chinos históricamente y en gran medida hoy. [19]

El antropólogo médico Charles Leslie escribe que las medicinas tradicionales china, grecoárabe e india se basaban en sistemas de correspondencia que alineaban la organización de la sociedad, el universo, el cuerpo humano y otras formas de vida en un "orden de cosas que lo abarcaba todo". Cada uno de estos sistemas tradicionales estaba organizado con cualidades como el calor y el frío, la humedad y la sequedad, la luz y la oscuridad, cualidades que también alinean las estaciones, las direcciones de la brújula y el ciclo humano de nacimiento, crecimiento y muerte. Proporcionaban, continuó Leslie, una "forma integral de concebir patrones que recorrían toda la naturaleza" y "servían como un dispositivo clasificatorio y mnemotécnico para observar los problemas de salud y reflexionar sobre el conocimiento empírico, almacenarlo y recuperarlo", pero también estaban "sujetos a una elaboración teórica embrutecedora, al autoengaño y al dogmatismo ". [20]

Las doctrinas de la medicina china tienen sus raíces en libros como el Canon Interno del Emperador Amarillo y el Tratado sobre el Daño por Frío , así como en nociones cosmológicas como el yin-yang y las cinco fases . La "Documentación de la materia médica china" (CMM) se remonta a alrededor de 1100 a. C., cuando solo se describieron unas pocas docenas de medicamentos. A fines del siglo XVI, el número de medicamentos documentados había llegado a cerca de 1900. Y a fines del siglo pasado, los registros publicados de CMM habían alcanzado los 12 800 medicamentos". [21] A partir de la década de 1950, estos preceptos se estandarizaron en la República Popular China, incluidos los intentos de integrarlos con nociones modernas de anatomía y patología . En la década de 1950, el gobierno chino promovió una forma sistematizada de MTC. [22]

Existen rastros de actividades terapéuticas en China que datan de la dinastía Shang (siglos XIV-XI a. C.). [23] Aunque los Shang no tenían un concepto de "medicina" distinto de otras prácticas de salud, sus inscripciones oraculares en huesos y caparazones de tortuga hacen referencia a enfermedades que afectaban a la familia real Shang: trastornos oculares, dolores de muelas, abdomen hinchado y similares. [24] Las élites Shang solían atribuirlas a maldiciones enviadas por sus antepasados. Actualmente no hay evidencia de que la nobleza Shang usara remedios a base de hierbas. [23]

Las agujas de piedra y hueso encontradas en tumbas antiguas llevaron a Joseph Needham a especular que la acupuntura podría haberse llevado a cabo en la dinastía Shang. [25] [26] Dicho esto, la mayoría de los historiadores ahora hacen una distinción entre la punción médica (o sangría ) y la acupuntura en el sentido más estricto de usar agujas de metal para intentar tratar enfermedades estimulando puntos a lo largo de los canales de circulación ("meridianos") de acuerdo con creencias relacionadas con la circulación del "Qi". [25] [26] [27] La evidencia más temprana de la acupuntura en este sentido data del siglo II o I a. C. [23] [25] [26] [28]

El Canon Interno del Emperador Amarillo ( Huangdi Neijing ) , la obra recibida más antigua de la teoría médica china, fue compilado durante la dinastía Han alrededor del siglo I a. C. sobre la base de textos más cortos de diferentes linajes médicos. [25] [26] [29] Escrito en forma de diálogos entre el legendario Emperador Amarillo y sus ministros, ofrece explicaciones sobre la relación entre los humanos, su entorno y el cosmos , sobre los contenidos del cuerpo, sobre la vitalidad y patología humana, sobre los síntomas de la enfermedad y sobre cómo tomar decisiones diagnósticas y terapéuticas a la luz de todos estos factores. [29] A diferencia de textos anteriores como Recetas para cincuenta y dos dolencias , que se excavó en la década de 1970 de la tumba de Mawangdui que había sido sellada en 168 a. C., el Canon Interno rechazó la influencia de los espíritus y el uso de la magia. [26] También fue uno de los primeros libros en los que las doctrinas cosmológicas del Yinyang y las Cinco Fases fueron llevadas a una síntesis madura. [29]

El Tratado sobre los trastornos causados por el frío y otras enfermedades diversas (Shang Han Lun) fue compilado por Zhang Zhongjing en algún momento entre 196 y 220 d. C.; al final de la dinastía Han. [30] Centrado en las prescripciones de medicamentos en lugar de la acupuntura, [31] [32] fue el primer trabajo médico que combinó el Yinyang y las Cinco Fases con la terapia farmacológica. [23] Este formulario también fue el primer texto médico público chino que agrupaba los síntomas en "patrones" clínicamente útiles ( zheng 證) que podían servir como objetivos para la terapia. Después de haber pasado por numerosos cambios a lo largo del tiempo, el formulario ahora circula como dos libros distintos: el Tratado sobre los trastornos causados por el frío y las Prescripciones esenciales del cofre de oro , que se editaron por separado en el siglo XI, bajo la dinastía Song . [33]

Nanjing o "Clásico de los problemas difíciles", originalmente llamado "El Emperador Amarillo Ochenta y un Nan Jing", atribuido a Bian Que en la dinastía Han del este . Este libro fue compilado en forma de explicaciones de preguntas y respuestas. Se han discutido un total de 81 preguntas. Por lo tanto, también se llama "Ochenta y un Nan". [34] El libro se basa en la teoría básica y también ha analizado algunos certificados de enfermedades. Las preguntas uno a veintidós tratan sobre el estudio del pulso, las preguntas veintitrés a veintinueve tratan sobre el estudio de los meridianos, las preguntas treinta a cuarenta y siete están relacionadas con enfermedades urgentes, las preguntas cuarenta y ocho a sesenta y uno están relacionadas con enfermedades graves, las preguntas sesenta y dos a sesenta y ocho están relacionadas con los puntos de acupuntura y las preguntas sesenta y nueve a ochenta y uno están relacionadas con los métodos de bordado. [34]

Se le atribuye al libro el desarrollo de su propio camino, al tiempo que hereda las teorías de Huangdi Neijing. El contenido incluye fisiología, patología, diagnóstico, contenidos de tratamiento y una discusión más esencial y específica del diagnóstico del pulso. [34] Se ha convertido en uno de los cuatro clásicos de los que los practicantes de la medicina china pueden aprender y ha influido en el desarrollo médico en China. [34]

Shennong Ben Cao Jing es uno de los primeros libros médicos escritos en China. Escrito durante la dinastía Han del Este entre 200 y 250 d. C., fue el esfuerzo combinado de los profesionales de las dinastías Qin y Han que resumieron, recopilaron y compilaron los resultados de la experiencia farmacológica durante sus períodos de tiempo. Fue el primer resumen sistemático de la medicina herbal china. [35] La mayoría de las teorías farmacológicas y las reglas de compatibilidad y el principio propuesto de "siete emociones y armonía" han desempeñado un papel en la práctica de la medicina durante miles de años. [35] Por lo tanto, ha sido un libro de texto para los trabajadores médicos en la China moderna. [35] El texto completo de Shennong Ben Cao Jing en inglés se puede encontrar en línea. [36]

En los siglos siguientes, varios libros más breves intentaron resumir o sistematizar el contenido del Canon Interno del Emperador Amarillo . El Canon de los Problemas (probablemente del siglo II d. C.) intentó reconciliar doctrinas divergentes del Canon Interno y desarrolló un sistema médico completo centrado en la terapia con agujas. [31] El Canon AB de Acupuntura y Moxibustión ( Zhenjiu jiayi jing 針灸甲乙經, compilado por Huangfu Mi en algún momento entre 256 y 282 d. C.) reunió un cuerpo consistente de doctrinas sobre la acupuntura; [31] mientras que el Canon del Pulso ( Maijing 脈經; c. 280) se presentó como un "manual completo de diagnóstico y terapia". [31]

Alrededor de los años 900 a 1000 d. C., los chinos fueron los primeros en desarrollar una forma de vacunación, conocida como variolación o inoculación , para prevenir la viruela . Los médicos chinos se habían dado cuenta de que cuando las personas sanas estaban expuestas al tejido de la costra de la viruela, tenían menos posibilidades de contraer la enfermedad más adelante. Los métodos comunes de inoculación en ese momento eran triturar las costras de la viruela hasta convertirlas en polvo y respirarlo por la nariz. [37]

Entre los eruditos médicos destacados del período post-Han se incluyen Tao Hongjing (456-536), Sun Simiao de las dinastías Sui y Tang, Zhang Jiegu ( c. 1151-1234 ) y Li Shizhen (1518-1593).

Las comunidades chinas que vivían en las ciudades portuarias coloniales se vieron influenciadas por las diversas culturas que conocieron, lo que también condujo a una evolución de la comprensión de las prácticas médicas en las que las formas chinas de medicina se combinaban con el conocimiento médico occidental. [16] Por ejemplo, el Hospital Tung Wah se estableció en Hong Kong en 1869 sobre la base del rechazo generalizado de la medicina occidental por las prácticas médicas preexistentes, aunque la medicina occidental todavía se practicaría en el hospital junto con las prácticas medicinales chinas. El Hospital Tung Wah probablemente estaba conectado a otra institución médica china, el Hospital Kwong Wai Shiu de Singapur, que tenía vínculos comunitarios previos con Tung Wah, se estableció por razones similares y también brindaba atención médica tanto occidental como china. [38] En 1935, los periódicos en idioma inglés en el Singapur colonial ya usaban el término "Medicina tradicional china" para etiquetar las prácticas médicas étnicas chinas. [39] [40]

En 1950, el presidente del Partido Comunista Chino (PCCh), Mao Zedong , anunció su apoyo a la medicina tradicional china, pero él personalmente no creía en ella ni la utilizaba. [22] En 1952, el presidente de la Asociación Médica China dijo que “Esta Medicina Única tendrá una base en las ciencias naturales modernas, habrá absorbido lo antiguo y lo nuevo, lo chino y lo extranjero, todos los logros médicos, ¡y será la Nueva Medicina de China!” [22]

Durante la Revolución Cultural (1966-1976), el PCCh y el gobierno enfatizaron la modernidad, la identidad cultural y la reconstrucción social y económica de China y las contrastaron con el pasado colonial y feudal. El gobierno estableció un sistema de atención médica de base como un paso en la búsqueda de una nueva identidad nacional e intentó revitalizar la medicina tradicional e hizo grandes inversiones en medicina tradicional para tratar de desarrollar atención médica asequible e instalaciones de salud pública. [41] El Ministerio de Salud dirigió la atención médica en toda China y estableció unidades de atención primaria. Los médicos chinos formados en medicina occidental debían aprender medicina tradicional, mientras que los curanderos tradicionales recibían formación en métodos modernos. Esta estrategia tenía como objetivo integrar conceptos y métodos médicos modernos y revitalizar aspectos apropiados de la medicina tradicional. Por lo tanto, la medicina tradicional china se recreó en respuesta a la medicina occidental. [41]

_at_Jiangsu_Chinese_Medical_Hospital_in_Nanjing_南京,_China_(34326619184).jpg/440px-Apothecary_mixing_traditional_chinese_medicin_(中药房)_at_Jiangsu_Chinese_Medical_Hospital_in_Nanjing_南京,_China_(34326619184).jpg)

En 1968, el PCCh apoyó un nuevo sistema de prestación de servicios de salud para las zonas rurales. A cada aldea se le asignó un médico descalzo (un personal médico con habilidades y conocimientos médicos básicos para tratar enfermedades menores) responsable de la atención médica básica. El personal médico combinó los valores de la China tradicional con métodos modernos para proporcionar atención médica y sanitaria a los agricultores pobres de las zonas rurales remotas. Los médicos descalzos se convirtieron en un símbolo de la Revolución Cultural, por la introducción de la medicina moderna en las aldeas donde se utilizaban los servicios de la medicina tradicional china. [41]

La Oficina Estatal de Propiedad Intelectual (ahora conocida como CNIPA ) estableció una base de datos de patentes otorgadas para la medicina tradicional china. [42]

En la segunda década del siglo XXI, el secretario general del Partido Comunista Chino, Xi Jinping, apoyó firmemente la medicina tradicional china, calificándola de "joya". En mayo de 2011, con el fin de promover la medicina tradicional china en todo el mundo, China había firmado acuerdos de asociación en materia de medicina tradicional china con más de 70 países. [43] Su gobierno presionó para aumentar su uso y el número de médicos formados en medicina tradicional china y anunció que los estudiantes de medicina tradicional china ya no tendrían que aprobar exámenes de medicina occidental. Sin embargo, los científicos e investigadores chinos expresaron su preocupación por el hecho de que la formación y las terapias en medicina tradicional china recibieran el mismo apoyo que la medicina occidental. También criticaron la reducción de las pruebas y la regulación gubernamentales de la producción de medicina tradicional china, algunas de las cuales eran tóxicas. Los censores gubernamentales han eliminado las publicaciones de Internet que cuestionan la medicina tradicional china. [44] En 2020, Pekín redactó una normativa local que prohíbe las críticas a la medicina tradicional china. [45] Según Caixin , la normativa se aprobó posteriormente con la disposición que prohibía las críticas a la medicina tradicional china eliminada. [46]

Al comienzo de la apertura de Hong Kong , la medicina occidental aún no era popular y los médicos occidentales eran en su mayoría extranjeros; los residentes locales dependían principalmente de los practicantes de medicina china. En 1841, el gobierno británico de Hong Kong emitió un comunicado en el que se comprometía a gobernar a los residentes de Hong Kong de acuerdo con todos los rituales, costumbres y derechos de propiedad privada originales. [47] Como la medicina tradicional china siempre se había utilizado en China, el uso de la medicina tradicional china no estaba regulado. [48]

La fundación del Hospital Tung Wah en 1870 fue el primer uso de la medicina china para el tratamiento en hospitales chinos que brindaban servicios médicos gratuitos. [49] A medida que el gobierno británico comenzó a promover la medicina occidental a partir de 1940, [50] la medicina occidental comenzó a ser popular entre la población de Hong Kong. En 1959, Hong Kong había investigado el uso de la medicina tradicional china para reemplazar la medicina occidental. [51] [ verificación requerida ]

Los historiadores han señalado dos aspectos clave de la historia médica china: comprender las diferencias conceptuales al traducir el término身y observar la historia desde la perspectiva de la cosmología en lugar de la biología. [52]

En los textos clásicos chinos, el término身es la traducción histórica más cercana a la palabra inglesa "cuerpo" porque a veces se refiere al cuerpo humano físico en términos de ser pesado o medido, pero el término debe entenderse como un "conjunto de funciones" que abarca tanto la psique humana como las emociones. Este concepto del cuerpo humano se opone a la dualidad europea de una mente y un cuerpo separados. [52] Es fundamental que los académicos comprendan las diferencias fundamentales en los conceptos del cuerpo para poder conectar la teoría médica de los clásicos con el "organismo humano" que está explicando. [52] : 20

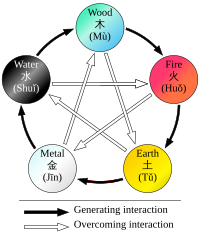

Los eruditos chinos establecieron una correlación entre el cosmos y el "organismo humano". Los componentes básicos de la cosmología, qi, yin yang y la teoría de las cinco fases, se utilizaron para explicar la salud y la enfermedad en textos como Huangdi neijing . [52] El yin y el yang son los factores cambiantes en la cosmología, con el qi como la fuerza vital o energía de la vida. La teoría de las cinco fases ( Wuxing ) de la dinastía Han contiene los elementos madera, fuego, tierra, metal y agua. Al comprender la medicina desde una perspectiva cosmológica, los historiadores comprenden mejor las clasificaciones médicas y sociales chinas como el género, que se definía por una dominación o remisión del yang en términos del yin.

Estas dos distinciones son imperativas al analizar la historia de la ciencia médica tradicional china.

La mayor parte de la historia médica china escrita según los cánones clásicos se presenta en forma de estudios de casos de fuentes primarias en los que los médicos académicos registran la enfermedad de una persona en particular y las técnicas de curación utilizadas, así como su eficacia. [52] Los historiadores han señalado que los eruditos chinos escribieron estos estudios en lugar de "libros de recetas o manuales de consejos"; en su comprensión histórica y ambiental, no había dos enfermedades iguales, por lo que las estrategias de curación del médico eran únicas en cada caso para el diagnóstico específico del paciente. [52] Los estudios de casos médicos existieron a lo largo de la historia china, pero la "historia de caso escrita y publicada individualmente" fue una creación destacada de la dinastía Ming. [52] Un ejemplo de tales estudios de casos sería el médico literato Cheng Congzhou, cuya colección de 93 casos se publicó en 1644. [52]

Los historiadores de la ciencia han desarrollado el estudio de la medicina en la China tradicional hasta convertirla en un campo con sus propias asociaciones académicas, revistas, programas de posgrado y debates entre sí. [53] Muchos distinguen la "medicina en la China tradicional" de la medicina tradicional china (MTC) reciente, que tomó elementos de textos y prácticas tradicionales para construir un cuerpo sistemático. Paul Unschuld, por ejemplo, ve una "alejamiento de la MTC de sus orígenes históricos". [54] Lo que se llama "medicina tradicional china" y se practica hoy en China y Occidente no tiene miles de años, sino que se construyó recientemente utilizando términos tradicionales seleccionados, algunos de los cuales se han sacado de contexto y otros se han malinterpretado gravemente. Ha criticado los libros populares chinos y occidentales por el uso selectivo de la evidencia , eligiendo solo aquellas obras o partes de obras históricas que parecen conducir a la medicina moderna, ignorando aquellos elementos que ahora no parecen ser efectivos. [55]

Los críticos dicen que la teoría y la práctica de la medicina tradicional china no tienen base en la ciencia moderna , y los practicantes de la medicina tradicional china no están de acuerdo sobre qué diagnóstico y tratamientos se deben utilizar para cada persona en particular. [11] Un editorial de 2007 en la revista Nature escribió que la medicina tradicional china "sigue estando poco investigada y respaldada, y la mayoría de sus tratamientos no tienen un mecanismo de acción lógico ". [2] [56] También describió a la medicina tradicional china como "plagada de pseudociencia ". [2] Una revisión de la literatura en 2008 encontró que los científicos "todavía no pueden encontrar una pizca de evidencia" de acuerdo con los estándares de la medicina basada en la ciencia para conceptos chinos tradicionales como el qi , los meridianos y los puntos de acupuntura, [57] y que los principios tradicionales de la acupuntura son profundamente defectuosos. [58] "Los puntos de acupuntura y los meridianos no son una realidad", continuó la revisión, sino "simplemente el producto de una antigua filosofía china". [59] En junio de 2019, la Organización Mundial de la Salud incluyó la medicina tradicional china en un compendio de diagnóstico global, pero un portavoz dijo que esto "no era un respaldo a la validez científica de ninguna práctica de medicina tradicional ni a la eficacia de ninguna intervención de medicina tradicional". [60] [61] [62]

Una revisión de 2012 de la investigación de costo-efectividad para la MTC encontró que los estudios tenían niveles bajos de evidencia , sin resultados beneficiosos. [63] La investigación farmacéutica sobre el potencial para crear nuevos medicamentos a partir de remedios tradicionales tiene pocos resultados exitosos. [2] Los defensores sugieren que la investigación hasta ahora ha pasado por alto características clave del arte de la MTC, como interacciones desconocidas entre varios ingredientes y sistemas biológicos interactivos complejos. [2] Uno de los principios básicos de la MTC es que el qi del cuerpo (a veces traducido como energía vital ) circula a través de canales llamados meridianos que tienen ramas conectadas a órganos y funciones corporales. [11] El concepto de energía vital es pseudocientífico. Los conceptos del cuerpo y de la enfermedad utilizados en la MTC reflejan sus orígenes antiguos y su énfasis en los procesos dinámicos sobre la estructura material, similar a la teoría humoral clásica . [12]

La medicina tradicional china también ha sido controvertida en China. En 2006, el filósofo chino Zhang Gongyao desencadenó un debate nacional con un artículo titulado “Adiós a la medicina tradicional china”, en el que sostenía que la medicina tradicional china era una pseudociencia que debía abolirse en la sanidad pública y en el mundo académico. El gobierno chino adoptó la postura de que la medicina tradicional china es una ciencia y siguió fomentando su desarrollo. [64]

Existe preocupación por una serie de plantas, partes de animales y compuestos minerales chinos potencialmente tóxicos, [65] así como por la facilitación de enfermedades. Los animales criados en granjas y traficados que se utilizan en la medicina tradicional china son una fuente de varias enfermedades zoonóticas letales . [66] Existen preocupaciones adicionales por el comercio y transporte ilegal de especies en peligro de extinción, incluidos los rinocerontes y los tigres, y el bienestar de los animales criados especialmente, incluidos los osos. [67]

La medicina tradicional china (MTC) es una amplia gama de prácticas médicas que comparten conceptos comunes que se han desarrollado en China y se basan en una tradición de más de 2000 años, que incluye varias formas de medicina herbal , acupuntura, masajes ( tui na ), ejercicio ( qigong ) y terapia dietética. [68] [69] Se utiliza principalmente como un enfoque de medicina alternativa complementaria. [68] La MTC se usa ampliamente en China y también en Occidente. [68] Su filosofía se basa en el Yinyangismo (es decir, la combinación de la teoría de las Cinco Fases con la teoría del Yin-Yang), [70] que luego fue absorbida por el Taoísmo . [71] Los textos filosóficos influyeron en la MTC, principalmente al basarse en las mismas teorías del qi , el yin-yang y el wuxing y las analogías microcosmos-macrocosmos. [72]

El yin y el yang son antiguos conceptos de razonamiento deductivo chino utilizados en el diagnóstico médico chino que se remontan a la dinastía Shang [73] (1600-1100 a. C.). Representan dos aspectos abstractos y complementarios en los que se puede dividir cada fenómeno del universo. [73] Las analogías primordiales para estos aspectos son el lado de una colina que mira hacia el sol (yang) y el lado sombreado (yin). [32] Otras dos alegorías representativas del yin y el yang que se utilizan comúnmente son el agua y el fuego. [73] En la teoría del yin-yang , se hacen atribuciones detalladas sobre el carácter yin o yang de las cosas:

El concepto de yin y yang también es aplicable al cuerpo humano; por ejemplo, la parte superior del cuerpo y la espalda se asignan al yang, mientras que se cree que la parte inferior del cuerpo tiene el carácter yin. [74] La caracterización del yin y el yang también se extiende a las diversas funciones corporales y, lo que es más importante, a los síntomas de las enfermedades (por ejemplo, se supone que las sensaciones de frío y calor son síntomas yin y yang, respectivamente). [74] Por lo tanto, el yin y el yang del cuerpo se consideran fenómenos cuya falta (o sobreabundancia) viene acompañada de combinaciones de síntomas característicos:

La medicina tradicional china también identifica medicamentos que se cree que tratan estas combinaciones de síntomas específicos, es decir, que refuerzan el yin y el yang. [32]

Se identifican reglas estrictas para aplicar a las relaciones entre las Cinco Fases en términos de secuencia, de acción entre sí, de contraataque, etc. [76] Todos estos aspectos de la teoría de las Cinco Fases constituyen la base del concepto zàng-fǔ y, por lo tanto, tienen una gran influencia con respecto al modelo de la MTC del cuerpo. [32] La teoría de las Cinco Fases también se aplica en el diagnóstico y la terapia. [32]

Históricamente, las correspondencias entre el cuerpo y el universo no solo se han visto en términos de los Cinco Elementos, sino también de los "Grandes Números" (大數; dà shū ) [79] Por ejemplo, a veces se ha visto que el número de puntos de acupuntura es 365, lo que corresponde al número de días de un año; y se ha visto que el número de meridianos principales (12) se corresponde con el número de ríos que fluyen a través del antiguo imperio chino . [79] [80]

La MTC "sostiene que la energía vital del cuerpo ( chi o qi ) circula a través de canales, llamados meridianos , que tienen ramas conectadas a los órganos y funciones corporales". [11] Su visión del cuerpo humano sólo se ocupa marginalmente de las estructuras anatómicas, sino que se centra principalmente en las funciones del cuerpo [79] [81] (como la digestión, la respiración, el mantenimiento de la temperatura, etc.):

Estas funciones se agregan y luego se asocian con una entidad funcional primaria; por ejemplo, la nutrición de los tejidos y el mantenimiento de su humedad se consideran funciones conectadas, y la entidad que se postula como responsable de estas funciones es xiě (sangre). [81] Estas entidades funcionales, por lo tanto, constituyen conceptos en lugar de algo con propiedades bioquímicas o anatómicas. [82]

Las entidades funcionales primarias utilizadas por la medicina tradicional china son qì, xuě, los cinco órganos zàng, los seis órganos fǔ y los meridianos que se extienden a través de los sistemas de órganos. [83] Todos ellos están teóricamente interconectados: cada órgano zàng está emparejado con un órgano fǔ, que se nutren de la sangre y concentran el qi para una función particular, y los meridianos son extensiones de esos sistemas funcionales en todo el cuerpo.

Los conceptos del cuerpo y de la enfermedad utilizados en la MTC son pseudocientíficos, similares a la teoría humoral mediterránea . [12] El modelo del cuerpo de la MTC se caracteriza por estar lleno de pseudociencia. [84] Algunos practicantes ya no consideran el yin y el yang ni la idea de un flujo de energía para aplicar. [85] La investigación científica no ha encontrado ninguna evidencia histológica o fisiológica de conceptos chinos tradicionales como el qi , los meridianos y los puntos de acupuntura. [a] Es una creencia generalizada dentro de la comunidad de acupuntura que los puntos de acupuntura y las estructuras de los meridianos son conductos especiales para señales eléctricas, pero ninguna investigación ha establecido ninguna estructura o función anatómica consistente para los puntos de acupuntura o los meridianos. [a] [86] La evidencia científica de la existencia anatómica de los meridianos o los puntos de acupuntura no es convincente. [87] Stephen Barrett, de Quackwatch , escribe que "la teoría y la práctica de la medicina tradicional china no se basan en el conjunto de conocimientos relacionados con la salud, la enfermedad y la atención sanitaria que ha sido ampliamente aceptado por la comunidad científica. Los profesionales de la medicina tradicional china no están de acuerdo entre sí sobre cómo diagnosticar a los pacientes y qué tratamientos deben ir con cada diagnóstico. Incluso si pudieran ponerse de acuerdo, las teorías de la medicina tradicional china son tan nebulosas que ningún estudio científico permitirá que la medicina tradicional china ofrezca una atención racional". [11]

Qi es una palabra polisémica que la medicina tradicional china distingue por ser capaz de transformarse en muchas cualidades diferentes de qi (气;氣; qì ). [88] En un sentido general, qi es algo que se define por cinco "funciones cardinales": [88]

La falta de qi se caracterizará especialmente por tez pálida, lasitud de espíritu, falta de fuerza, sudoración espontánea, pereza para hablar, falta de digestión de los alimentos, dificultad para respirar (especialmente al hacer esfuerzo) y una lengua pálida y agrandada. [74]

Se cree que el Qi se genera en parte a partir de los alimentos y bebidas, y en parte a partir del aire (al respirar). Otra parte considerable se hereda de los padres y se consume a lo largo de la vida.

La MTC utiliza términos especiales para el qi que circula por el interior de los vasos sanguíneos y para el qi que se distribuye en la piel, los músculos y los tejidos entre ellos. El primero se denomina yingqi (营气;營氣; yíngqì ); su función es complementar el xuè y su naturaleza tiene un fuerte aspecto yin (aunque el qi en general se considera yang). [89] El segundo se denomina weiqi (卫气;衛氣; weìqì ); su función principal es la defensa y tiene una naturaleza yang pronunciada. [89]

Se dice que el Qi circula por los meridianos. Al igual que el Qi que retiene cada uno de los órganos zang-fu, se considera que este forma parte del Qi "principal" del cuerpo. [b]

A diferencia de la mayoría de las demás entidades funcionales, xuè o xiě (血, "sangre") se correlaciona con una forma física: el líquido rojo que corre por los vasos sanguíneos. [90] Su concepto, sin embargo, está definido por sus funciones: nutrir todas las partes y tejidos del cuerpo, salvaguardar un grado adecuado de humedad y sostener y calmar tanto la conciencia como el sueño. [90]

Los síntomas típicos de una falta de xiě (generalmente denominada "vacío de sangre" [血虚; xiě xū ]) se describen como: tez blanca pálida o amarilla marchita, mareos, visión florida, palpitaciones, insomnio, entumecimiento de las extremidades; lengua pálida; pulso "fino". [91]

Closely related to xuě are the jinye (津液; jīnyè, usually translated as "body fluids"), and just like xuě they are considered to be yin in nature, and defined first and foremost by the functions of nurturing and moisturizing the different structures of the body.[92] Their other functions are to harmonize yin and yang, and to help with the secretion of waste products.[93]

Jinye are ultimately extracted from food and drink, and constitute the raw material for the production of xuě; conversely, xuě can also be transformed into jinye.[92] Their palpable manifestations are all bodily fluids: tears, sputum, saliva, gastric acid, joint fluid, sweat, urine, etc.[94]

The zangfu (脏腑; 臟腑; zàngfǔ) are the collective name of eleven entities (similar to organs) that constitute the centre piece of TCM's systematization of bodily functions. The term zang refers to the five considered to be yin in nature – Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung, Kidney – while fu refers to the six associated with yang – Small Intestine, Large Intestine, Gallbladder, Urinary Bladder, Stomach and San Jiao.[95] Despite having the names of organs, they are only loosely tied to (rudimentary) anatomical assumptions.[96] Instead, they are primarily understood to be certain "functions" of the body.[75][81] To highlight the fact that they are not equivalent to anatomical organs, their names are usually capitalized.

The zang's essential functions consist in production and storage of qi and xuě; they are said to regulate digestion, breathing, water metabolism, the musculoskeletal system, the skin, the sense organs, aging, emotional processes, and mental activity, among other structures and processes.[97] The fǔ organs' main purpose is merely to transmit and digest (傳化; chuán-huà)[98] substances such as waste and food.

Since their concept was developed on the basis of Wǔ Xíng philosophy, each zàng is paired with a fǔ, and each zàng-fǔ pair is assigned to one of five elemental qualities (i.e., the Five Elements or Five Phases).[99] These correspondences are stipulated as:

The zàng-fǔ are also connected to the twelve standard meridians – each yang meridian is attached to a fǔ organ, and five of the yin meridians are attached to a zàng.[100] As there are only five zàng but six yin meridians, the sixth is assigned to the Pericardium, a peculiar entity almost similar to the Heart zàng.[100]

The meridians (经络, jīng-luò) are believed to be channels running from the zàng-fǔ in the interior (里, lǐ) of the body to the limbs and joints ("the surface" [表, biaǒ]), transporting qi and xuĕ.[101] TCM identifies 12 "regular" and 8 "extraordinary" meridians;[83] the Chinese terms being 十二经脉 (shí-èr jīngmài, lit. "the Twelve Vessels") and 奇经八脉 (qí jīng bā mài) respectively.[102] There's also a number of less customary channels branching from the "regular" meridians.[83]

Fuke (妇科; 婦科; Fùkē) is the traditional Chinese term for women's medicine (it means gynecology and obstetrics in modern medicine). However, there are few or no ancient works on it except for Fu Qingzhu's Fu Qingzhu Nu Ke (Fu Qingzhu's Gynecology).[103] In traditional China, as in many other cultures, the health and medicine of female bodies was less understood than that of male bodies. Women's bodies were often secondary to male bodies, since women were thought of as the weaker, sicklier sex.[104]

In clinical encounters, women and men were treated differently. Diagnosing women was not as simple as diagnosing men. First, when a woman fell ill, an appropriate adult man was to call the doctor and remain present during the examination, for the woman could not be left alone with the doctor.[105] The physician would discuss the female's problems and diagnosis only through the male. However, in certain cases, when a woman dealt with complications of pregnancy or birth, older women assumed the role of the formal authority. Men in these situations would not have much power to interfere.[106] Second, women were often silent about their issues with doctors due to the societal expectation of female modesty when a male figure was in the room.[105] Third, patriarchal society also caused doctors to call women and children patients "the anonymous category of family members (Jia Ren) or household (Ju Jia)"[105] in their journals. This anonymity and lack of conversation between the doctor and woman patient led to the inquiry diagnosis of the Four Diagnostic Methods[107] being the most challenging. Doctors used a medical doll known as a Doctor's lady, on which female patients could indicate the location of their symptoms.[108]

Cheng Maoxian (b. 1581), who practiced medicine in Yangzhou, described the difficulties doctors had with the norm of female modesty. One of his case studies was that of Fan Jisuo's teenage daughter, who could not be diagnosed because she was unwilling to speak about her symptoms, since the illness involved discharge from her intimate areas.[106] As Cheng describes, there were four standard methods of diagnosis – looking, asking, listening and smelling and touching (for pulse-taking). To maintain some form of modesty, women would often stay hidden behind curtains and screens. The doctor was allowed to touch enough of her body to complete his examination, often just the pulse taking. This would lead to situations where the symptoms and the doctor's diagnosis did not agree and the doctor would have to ask to view more of the patient.[109]

These social and cultural beliefs were often barriers to learning more about female health, with women themselves often being the most formidable barrier. Women were often uncomfortable talking about their illnesses, especially in front of the male chaperones that attended medical examinations.[104] Women would choose to omit certain symptoms as a means of upholding their chastity and honor. One such example is the case in which a teenage girl was unable to be diagnosed because she failed to mention her symptom of vaginal discharge.[104] Silence was their way of maintaining control in these situations, but it often came at the expense of their health and the advancement of female health and medicine. This silence and control were most obviously seen when the health problem was related to the core of Ming fuke, or the sexual body.[104] It was often in these diagnostic settings that women would choose silence. In addition, there would be a conflict between patient and doctor on the probability of her diagnosis. For example, a woman who thought herself to be past the point of child-bearing age, might not believe a doctor who diagnoses her as pregnant.[104] This only resulted in more conflict.

Yin and yang were critical to the understanding of women's bodies, but understood only in conjunction with male bodies.[110] Yin and yang ruled the body, the body being a microcosm of the universe and the earth. In addition, gender in the body was understood as homologous, the two genders operating in synchronization.[104] Gender was presumed to influence the movement of energy and a well-trained physician would be expected to read the pulse and be able to identify two dozen or more energy flows.[111] Yin and yang concepts were applied to the feminine and masculine aspects of all bodies, implying that the differences between men and women begin at the level of this energy flow. According to Bequeathed Writings of Master Chu the male's yang pulse movement follows an ascending path in "compliance [with cosmic direction] so that the cycle of circulation in the body and the Vital Gate are felt...The female's yin pulse movement follows a defending path against the direction of cosmic influences, so that the nadir and the Gate of Life are felt at the inch position of the left hand".[112] In sum, classical medicine marked yin and yang as high and low on bodies which in turn would be labeled normal or abnormal and gendered either male or female.[106]

Bodily functions could be categorized through systems, not organs. In many drawings and diagrams, the twelve channels and their visceral systems were organized by yin and yang, an organization that was identical in female and male bodies. Female and male bodies were no different on the plane of yin and yang. Their gendered differences were not acknowledged in diagrams of the human body. Medical texts such as the Yuzuan yizong jinjian were filled with illustrations of male bodies or androgynous bodies that did not display gendered characteristics.[113]

As in other cultures, fertility and menstruation dominate female health concerns.[104] Since male and female bodies were governed by the same forces, traditional Chinese medicine did not recognize the womb as the place of reproduction. The abdominal cavity presented pathologies that were similar in both men and women, which included tumors, growths, hernias, and swellings of the genitals. The "master system", as Charlotte Furth calls it, is the kidney visceral system, which governed reproductive functions. Therefore, it was not the anatomical structures that allowed for pregnancy, but the difference in processes that allowed for the condition of pregnancy to occur.[104]

Traditional Chinese medicine's dealings with pregnancy are documented from at least the seventeenth century. According to Charlotte Furth, "a pregnancy (in the seventeenth century) as a known bodily experience emerged [...] out of the liminality of menstrual irregularity, as uneasy digestion, and a sense of fullness".[105] These symptoms were common among other illness as well, so the diagnosis of pregnancy often came late in the term. The Canon of the Pulse, which described the use of pulse in diagnosis, stated that pregnancy was "a condition marked by symptoms of the disorder in one whose pulse is normal" or "where the pulse and symptoms do not agree".[114] Women were often silent about suspected pregnancy, which led to many men not knowing that their wife or daughter was pregnant until complications arrived. Complications through the misdiagnosis and the woman's reluctance to speak often led to medically induced abortions. Cheng, Furth wrote, "was unapologetic about endangering a fetus when pregnancy risked a mother's well being".[105] The method of abortion was the ingestion of certain herbs and foods. Disappointment at the loss of the fetus often led to family discord.[105]

If the baby and mother survived the term of the pregnancy, childbirth was then the next step. The tools provided for birth were: towels to catch the blood, a container for the placenta, a pregnancy sash to support the belly, and an infant swaddling wrap.[115] With these tools, the baby was born, cleaned, and swaddled; however, the mother was then immediately the focus of the doctor to replenish her qi.[105] In his writings, Cheng places a large amount of emphasis on the Four Diagnostic methods to deal with postpartum issues and instructs all physicians to "not neglect any [of the four methods]".[105] The process of birthing was thought to deplete a woman's blood level and qi so the most common treatments for postpartum were food (commonly garlic and ginseng), medicine, and rest.[116] This process was followed up by a month check-in with the physician, a practice known as zuo yuezi.[117]

Infertility, not very well understood, posed serious social and cultural repercussions. The seventh-century scholar Sun Simiao is often quoted: "those who have prescriptions for women's distinctiveness take their differences of pregnancy, childbirth and [internal] bursting injuries as their basis."[110] Even in contemporary fuke placing emphasis on reproductive functions, rather than the entire health of the woman, suggests that the main function of fuke is to produce children.

Once again, the kidney visceral system governs the "source Qi", which governs the reproductive systems in both sexes. This source Qi was thought to "be slowly depleted through sexual activity, menstruation and childbirth."[110] It was also understood that the depletion of source Qi could result from the movement of an external pathology that moved through the outer visceral systems before causing more permanent damage to the home of source Qi, the kidney system. In addition, the view that only very serious ailments ended in the damage of this system means that those who had trouble with their reproductive systems or fertility were seriously ill.

According to traditional Chinese medical texts, infertility can be summarized into different syndrome types. These were spleen and kidney depletion (yang depletion), liver and kidney depletion (yin depletion), blood depletion, phlegm damp, liver oppression, and damp heat. This is important because, while most other issues were complex in Chinese medical physiology, women's fertility issues were simple. Most syndrome types revolved around menstruation, or lack thereof. The patient was entrusted with recording not only the frequency, but also the "volume, color, consistency, and odor of menstrual flow."[110] This placed responsibility of symptom recording on the patient, and was compounded by the earlier discussed issue of female chastity and honor. This meant that diagnosing female infertility was difficult, because the only symptoms that were recorded and monitored by the physician were the pulse and color of the tongue.[110]

In general, disease is perceived as a disharmony (or imbalance) in the functions or interactions of yin, yang, qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians etc. and/or of the interaction between the human body and the environment.[74] Therapy is based on which "pattern of disharmony" can be identified.[32][118] Thus, "pattern discrimination" is the most important step in TCM diagnosis.[32][118] It is also known to be the most difficult aspect of practicing TCM.[119]

To determine which pattern is at hand, practitioners will examine things like the color and shape of the tongue, the relative strength of pulse-points, the smell of the breath, the quality of breathing or the sound of the voice.[120][121] For example, depending on tongue and pulse conditions, a TCM practitioner might diagnose bleeding from the mouth and nose as: "Liver fire rushes upwards and scorches the Lung, injuring the blood vessels and giving rise to reckless pouring of blood from the mouth and nose."[122] He might then go on to prescribe treatments designed to clear heat or supplement the Lung.

In TCM, a disease has two aspects: "bìng" and "zhèng".[123] The former is often translated as "disease entity",[32] "disease category",[119] "illness",[123] or simply "diagnosis".[123] The latter, and more important one, is usually translated as "pattern"[32][119] (or sometimes also as "syndrome"[123]). For example, the disease entity of a common cold might present with a pattern of wind-cold in one person, and with the pattern of wind-heat in another.[32]

From a scientific point of view, most of the disease entities (病; bìng) listed by TCM constitute symptoms.[32] Examples include headache, cough, abdominal pain, constipation etc.[32][124]

Since therapy will not be chosen according to the disease entity but according to the pattern, two people with the same disease entity but different patterns will receive different therapy.[118] Vice versa, people with similar patterns might receive similar therapy even if their disease entities are different. This is called yì bìng tóng zhì, tóng bìng yì zhì (异病同治,同病异治; 'different diseases', ' same treatment', ' same disease', ' different treatments').[118]

In TCM, "pattern" (证; zhèng) refers to a "pattern of disharmony" or "functional disturbance" within the functional entities of which the TCM model of the body is composed.[32] There are disharmony patterns of qi, xuě, the body fluids, the zàng-fǔ, and the meridians.[123] They are ultimately defined by their symptoms and signs (i.e., for example, pulse and tongue findings).[118]

In clinical practice, the identified pattern usually involves a combination of affected entities[119] (compare with typical examples of patterns). The concrete pattern identified should account for all the symptoms a person has.[118]

The Six Excesses (六淫; liù yín,[74] sometimes also translated as "Pathogenic Factors",[125] or "Six Pernicious Influences";[81] with the alternative term of 六邪; liù xié, – "Six Evils" or "Six Devils")[81] are allegorical terms used to describe disharmony patterns displaying certain typical symptoms.[32] These symptoms resemble the effects of six climatic factors.[81] In the allegory, these symptoms can occur because one or more of those climatic factors (called 六气; liù qì, "the six qi")[77] were able to invade the body surface and to proceed to the interior.[32] This is sometimes used to draw causal relationships (i.e., prior exposure to wind/cold/etc. is identified as the cause of a disease),[77] while other authors explicitly deny a direct cause-effect relationship between weather conditions and disease,[32][81] pointing out that the Six Excesses are primarily descriptions of a certain combination of symptoms[32] translated into a pattern of disharmony.[81] It is undisputed, though, that the Six Excesses can manifest inside the body without an external cause.[32][74] In this case, they might be denoted "internal", e.g., "internal wind"[74] or "internal fire (or heat)".[74]

The Six Excesses and their characteristic clinical signs are:

Six-Excesses-patterns can consist of only one or a combination of Excesses (e.g., wind-cold, wind-damp-heat).[77] They can also transform from one into another.[77]

For each of the functional entities (qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians etc.), typical disharmony patterns are recognized; for example: qi vacuity and qi stagnation in the case of qi;[74] blood vacuity, blood stasis, and blood heat in the case of xuĕ;[74] Spleen qi vacuity, Spleen yang vacuity, Spleen qi vacuity with down-bearing qi, Spleen qi vacuity with lack of blood containment, cold-damp invasion of the Spleen, damp-heat invasion of Spleen and Stomach in case of the Spleen zàng;[32] wind/cold/damp invasion in the case of the meridians.[118]

TCM gives detailed prescriptions of these patterns regarding their typical symptoms, mostly including characteristic tongue and/or pulse findings.[74][118] For example:

The process of determining which actual pattern is on hand is called 辩证 (biàn zhèng, usually translated as "pattern diagnosis",[32] "pattern identification"[74] or "pattern discrimination"[119]). Generally, the first and most important step in pattern diagnosis is an evaluation of the present signs and symptoms on the basis of the "Eight Principles" (八纲; bā gāng).[32][74] These eight principles refer to four pairs of fundamental qualities of a disease: exterior/interior, heat/cold, vacuity/repletion, and yin/yang.[74] Out of these, heat/cold and vacuity/repletion have the biggest clinical importance.[74] The yin/yang quality, on the other side, has the smallest importance and is somewhat seen aside from the other three pairs, since it merely presents a general and vague conclusion regarding what other qualities are found.[74] In detail, the Eight Principles refer to the following:

After the fundamental nature of a disease in terms of the Eight Principles is determined, the investigation focuses on more specific aspects.[74] By evaluating the present signs and symptoms against the background of typical disharmony patterns of the various entities, evidence is collected whether or how specific entities are affected.[74] This evaluation can be done

There are also three special pattern diagnosis systems used in case of febrile and infectious diseases only ("Six Channel system" or "six division pattern" [六经辩证; liù jīng biàn zhèng]; "Wei Qi Ying Xue system" or "four division pattern" [卫气营血辩证; weì qì yíng xuè biàn zhèng]; "San Jiao system" or "three burners pattern" [三焦辩证; sānjiaō biàn zhèng]).[118][123]

Although TCM and its concept of disease do not strongly differentiate between cause and effect,[81] pattern discrimination can include considerations regarding the disease cause; this is called 病因辩证 (bìngyīn biàn zhèng, "disease-cause pattern discrimination").[119]

There are three fundamental categories of disease causes (三因; sān yīn) recognized:[74]

In TCM, there are five major diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation, olfaction, inquiry, and palpation.[128] These are grouped into what is known as the "Four pillars" of diagnosis, which are Inspection, Auscultation/ Olfaction, Inquiry, and Palpation (望,聞,問,切).

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in TCM. Details of the tongue, including shape, size, color, texture, cracks, teeth marks, as well as tongue coating are all considered as part of tongue diagnosis. Various regions of the tongue's surface are believed to correspond to the zàng-fŭ organs. For example, redness on the tip of the tongue might indicate heat in the Heart, while redness on the sides of the tongue might indicate heat in the Liver.[129]

Pulse palpation involves measuring the pulse both at a superficial and at a deep level at three different locations on the radial artery (Cun, Guan, Chi, located two fingerbreadths from the wrist crease, one fingerbreadth from the wrist crease, and right at the wrist crease, respectively, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring finger) of each arm, for a total of twelve pulses, all of which are thought to correspond with certain zàng-fŭ. The pulse is examined for several characteristics including rhythm, strength and volume, and described with qualities like "floating, slippery, bolstering-like, feeble, thready and quick"; each of these qualities indicates certain disease patterns. Learning TCM pulse diagnosis can take several years.[130]

The term "herbal medicine" is somewhat misleading in that, while plant elements are by far the most commonly used substances in TCM, other, non-botanic substances are used as well: animal, human, fungi, and mineral products are also used.[133][134] Thus, the term "medicinal" (instead of herb) may be used.[135] A 2019 review of traditional herbal treatments found they are widely used but lacking in scientific evidence, and urged a more rigorous approach by which genuinely useful medicinals might be identified.[1]

There are roughly 13,000 compounds used in China and over 100,000 TCM recipes recorded in the ancient literature.[136] Plant elements and extracts are by far the most common elements used.[137] In the classic Handbook of Traditional Drugs from 1941, 517 drugs were listed – out of these, 45 were animal parts, and 30 were minerals.[137]

Some animal parts used include cow gallstones,[138] hornet nests,[139] leeches,[140] and scorpion.[141] Other examples of animal parts include horn of the antelope or buffalo, deer antlers, testicles and penis bone of the dog, and snake bile.[142] Some TCM textbooks still recommend preparations containing animal tissues, but there has been little research to justify the claimed clinical efficacy of many TCM animal products.[142]

Some compounds can include the parts of endangered species, including tiger bones[143] and rhinoceros horn[144]which is used for many ailments (though not as an aphrodisiac as is commonly misunderstood in the West).[145]The black market in rhinoceros horns (driven not just by TCM but also unrelated status-seeking) has reduced the world's rhino population by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years.[146]Concerns have also arisen over the use of pangolin scales,[147] turtle plastron,[148] seahorses,[149] and the gill plates of mobula and manta rays.[150]

Poachers hunt restricted or endangered species to supply the black market with TCM products.[151][152] There is no scientific evidence of efficacy for tiger medicines.[151] Concern over China considering to legalize the trade in tiger parts prompted the 171-nation Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) to endorse a decision opposing the resurgence of trade in tigers.[151] Fewer than 30,000 saiga antelopes remain, which are exported to China for use in traditional fever therapies.[152] Organized gangs illegally export the horn of the antelopes to China.[152] The pressures on seahorses (Hippocampus spp.) used in traditional medicine is enormous; tens of millions of animals are unsustainably caught annually.[132] Many species of syngnathid are currently part of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or national equivalents.[132]

Since TCM recognizes bear bile as a treatment compound, more than 12,000 asiatic black bears are held in bear farms. The bile is extracted through a permanent hole in the abdomen leading to the gall bladder, which can cause severe pain. This can lead to bears trying to kill themselves. As of 2012, approximately 10,000 bears are farmed in China for their bile.[153] This practice has spurred public outcry across the country.[153] The bile is collected from live bears via a surgical procedure.[153] As of March 2020 bear bile as ingredient of Tan Re Qing injection remains on the list of remedies recommended for treatment of "severe cases" of COVID-19 by National Health Commission of China and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine.[154]

The deer penis is believed to have therapeutic benefits according to traditional Chinese medicine. Tiger parts from poached animals include tiger penis, believed to improve virility, and tiger eyes.[155] The illegal trade for tiger parts in China has driven the species to near-extinction because of its popularity in traditional medicine.[156][155] Laws protecting even critically endangered species such as the Sumatran tiger fail to stop the display and sale of these items in open markets.[157] Shark fin soup is traditionally regarded in Chinese medicine as beneficial for health in East Asia, and its status as an elite dish has led to huge demand with the increase of affluence in China, devastating shark populations.[158] The shark fins have been a part of traditional Chinese medicine for centuries.[159] Shark finning is banned in many countries, but the trade is thriving in Hong Kong and China, where the fins are part of shark fin soup, a dish considered a delicacy, and used in some types of traditional Chinese medicine.[160]

The tortoise (freshwater turtle, guiban) and turtle (Chinese softshell turtle, biejia) species used in traditional Chinese medicine are raised on farms, while restrictions are made on the accumulation and export of other endangered species.[161] However, issues concerning the overexploitation of Asian turtles in China have not been completely solved.[161] Australian scientists have developed methods to identify medicines containing DNA traces of endangered species.[162] Finally, although not an endangered species, sharp rises in exports of donkeys and donkey hide from Africa to China to make the traditional remedy ejiao have prompted export restrictions by some African countries.[163]

Traditional Chinese medicine also includes some human parts: the classic Materia medica (Bencao Gangmu) describes (also criticizes) the use of 35 human body parts and excreta in medicines, including bones, fingernail, hairs, dandruff, earwax, impurities on the teeth, feces, urine, sweat, organs, but most are no longer in use.[165][166][167]

Human placenta has been used an ingredient in certain traditional Chinese medicines,[168] including using dried human placenta, known as "Ziheche", to treat infertility, impotence and other conditions.[164] The consumption of the human placenta is a potential source of infection.[168]

The traditional categorizations and classifications that can still be found today are:

As of 2007[update] there were not enough good-quality trials of herbal therapies to allow their effectiveness to be determined.[56] A high percentage of relevant studies on traditional Chinese medicine are in Chinese databases. Fifty percent of systematic reviews on TCM did not search Chinese databases, which could lead to a bias in the results.[170] Many systematic reviews of TCM interventions published in Chinese journals are incomplete, some contained errors or were misleading.[171] The herbs recommended by traditional Chinese practitioners in the US are unregulated.[172]

.jpg/440px-Artemisia_annua(01).jpg)

With an eye to the enormous Chinese market, pharmaceutical companies have explored creating new drugs from traditional remedies. The journal Nature commented that "claims made on behalf of an uncharted body of knowledge should be treated with the customary skepticism that is the bedrock of both science and medicine."[2]

There had been success in the 1970s, however, with the development of the antimalarial drug artemisinin, which is a processed extract of Artemisia annua, a herb traditionally used as a fever treatment.[2][188] Artemisia annua has been used by Chinese herbalists in traditional Chinese medicines for 2,000 years. In 1596, Li Shizhen recommended tea made from qinghao specifically to treat malaria symptoms in his Compendium of Materia Medica. Researcher Tu Youyou discovered that a low-temperature extraction process could isolate an effective antimalarial substance from the plant.[189] Tu says she was influenced by a traditional Chinese herbal medicine source, The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments, written in 340 by Ge Hong, which states that this herb should be steeped in cold water.[189] The extracted substance, once subject to detoxification and purification processes, is a usable antimalarial drug[188] – a 2012 review found that artemisinin-based remedies were the most effective drugs for the treatment of malaria.[190] For her work on malaria, Tu received the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Despite global efforts in combating malaria, it remains a large burden for the population.[191] Although WHO recommends artemisinin-based remedies for treating uncomplicated malaria, resistance to the drug can no longer be ignored.[191][192]

Also in the 1970s Chinese researcher Zhang TingDong and colleagues investigated the potential use of the traditionally used substance arsenic trioxide to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).[193] Building on his work, research both in China and the West eventually led to the development of the drug Trisenox, which was approved for leukemia treatment by the FDA in 2000.[194]

Huperzine A, an extract from the herb, Huperzia serrata, is under preliminary research as a possible therapeutic for Alzheimer's disease, but poor methodological quality of the research restricts conclusions about its effectiveness.[195]

Ephedrine in its natural form, known as má huáng (麻黄) in TCM, has been documented in China since the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) as an antiasthmatic and stimulant.[196] In 1885, the chemical synthesis of ephedrine was first accomplished by Japanese organic chemist Nagai Nagayoshi based on his research on Japanese and Chinese traditional herbal medicines[197]

Pien tze huang was first documented in the Ming dynasty.

A 2012 systematic review found there is a lack of available cost-effectiveness evidence in TCM.[63]

From the earliest records regarding the use of compounds to today, the toxicity of certain substances has been described in all Chinese materiae medicae.[32] Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese plants, animal parts and minerals.[65] Traditional Chinese herbal remedies are conveniently available from grocery stores in most Chinese neighborhoods; some of these items may contain toxic ingredients, are imported into the U.S. illegally, and are associated with claims of therapeutic benefit without evidence.[200] For most compounds, efficacy and toxicity testing are based on traditional knowledge rather than laboratory analysis.[65] The toxicity in some cases could be confirmed by modern research (i.e., in scorpion); in some cases it could not (i.e., in Curculigo).[32] Traditional herbal medicines can contain extremely toxic chemicals and heavy metals, and naturally occurring toxins, which can cause illness, exacerbate pre-existing poor health or result in death.[201] Botanical misidentification of plants can cause toxic reactions in humans.[202] The description of some plants used in TCM has changed, leading to unintended poisoning by using the wrong plants.[202] A concern is also contaminated herbal medicines with microorganisms and fungal toxins, including aflatoxin.[202] Traditional herbal medicines are sometimes contaminated with toxic heavy metals, including lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium, which inflict serious health risks to consumers.[203] Also, adulteration of some herbal medicine preparations with conventional drugs which may cause serious adverse effects, such as corticosteroids, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, and glibenclamide, has been reported.[202][204]

Substances known to be potentially dangerous include Aconitum,[32][65] secretions from the Asiatic toad,[200] powdered centipede,[205] the Chinese beetle (Mylabris phalerata),[206] certain fungi,[207] Aristolochia,[65] arsenic sulfide (realgar),[208] mercury sulfide,[209] and cinnabar.[210] Asbestos ore (Actinolite, Yang Qi Shi, 阳起石) is used to treat impotence in TCM.[211] Due to galena's (litharge, lead(II) oxide) high lead content, it is known to be toxic.[198] Lead, mercury, arsenic, copper, cadmium, and thallium have been detected in TCM products sold in the U.S. and China.[208]

To avoid its toxic adverse effects Xanthium sibiricum must be processed.[65] Hepatotoxicity has been reported with products containing Reynoutria multiflora (synonym Polygonum multiflorum), glycyrrhizin, Senecio and Symphytum.[65] The herbs indicated as being hepatotoxic included Dictamnus dasycarpus, Astragalus membranaceus, and Paeonia lactiflora.[65] Contrary to popular belief, Ganoderma lucidum mushroom extract, as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy, appears to have the potential for toxicity.[212] A 2013 review suggested that although the antimalarial herb Artemisia annua may not cause hepatotoxicity, haematotoxicity, or hyperlipidemia, it should be used cautiously during pregnancy due to a potential risk of embryotoxicity at a high dose.[213]

However, many adverse reactions are due to misuse or abuse of Chinese medicine.[65] For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy.[65] Products adulterated with pharmaceuticals for weight loss or erectile dysfunction are one of the main concerns.[65] Chinese herbal medicine has been a major cause of acute liver failure in China.[214]

The harvesting of guano from bat caves (yemingsha) brings workers into close contact with these animals, increasing the risk of zoonosis.[215] The Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli has identified dozens of SARS-like coronaviruses in samples of bat droppings.[216]

Acupuncture is the insertion of needles into superficial structures of the body (skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscles) – usually at acupuncture points (acupoints) – and their subsequent manipulation; this aims at influencing the flow of qi.[217] According to TCM it relieves pain and treats (and prevents) various diseases.[218] The US FDA classifies single-use acupuncture needles as Class II medical devices, under CFR 21.[219]

Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion – the Chinese characters for acupuncture (针灸; 針灸; zhēnjiǔ) literally meaning "acupuncture-moxibustion" – which involves burning mugwort on or near the skin at an acupuncture point.[220] According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that moxibustion is effective in preventing or treating cancer or any other disease".[221]

In electroacupuncture, an electric current is applied to the needles once they are inserted, to further stimulate the respective acupuncture points.[222]

A recent historian of Chinese medicine remarked that it is "nicely ironic that the specialty of acupuncture – arguably the most questionable part of their medical heritage for most Chinese at the start of the twentieth century – has become the most marketable aspect of Chinese medicine." She found that acupuncture as we know it today has hardly been in existence for sixty years. Moreover, the fine, filiform needle we think of as the acupuncture needle today was not widely used a century ago. Present day acupuncture was developed in the 1930s and put into wide practice only as late as the 1960s.[223]

A 2013 editorial in the American journal Anesthesia and Analgesia stated that acupuncture studies produced inconsistent results, (i.e. acupuncture relieved pain in some conditions but had no effect in other very similar conditions) which suggests the presence of false positive results. These may be caused by factors like biased study design, poor blinding, and the classification of electrified needles (a type of TENS) as a form of acupuncture. The inability to find consistent results despite more than 3,000 studies, the editorial continued, suggests that the treatment seems to be a placebo effect and the existing equivocal positive results are the type of noise one expects to see after a large number of studies are performed on an inert therapy. The editorial concluded that the best controlled studies showed a clear pattern, in which the outcome does not rely upon needle location or even needle insertion, and since "these variables are those that define acupuncture, the only sensible conclusion is that acupuncture does not work."[224]

According to the US NIH National Cancer Institute, a review of 17,922 patients reported that real acupuncture relieved muscle and joint pain, caused by aromatase inhibitors, much better than sham acupuncture.[225] Regarding cancer patients, the review hypothesized that acupuncture may cause physical responses in nerve cells, the pituitary gland, and the brain – releasing proteins, hormones, and chemicals that are proposed to affect blood pressure, body temperature, immune activity, and endorphin release.[225]

A 2012 meta-analysis concluded that the mechanisms of acupuncture "are clinically relevant, but that an important part of these total effects is not due to issues considered to be crucial by most acupuncturists, such as the correct location of points and depth of needling ... [but is] ... associated with more potent placebo or context effects".[226] Commenting on this meta-analysis, both Edzard Ernst and David Colquhoun said the results were of negligible clinical significance.[227][228]

A 2011 overview of Cochrane reviews found evidence that suggests acupuncture is effective for some but not all kinds of pain.[229] A 2010 systematic review found that there is evidence "that acupuncture provides a short-term clinically relevant effect when compared with a waiting list control or when acupuncture is added to another intervention" in the treatment of chronic low back pain.[230] Two review articles discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture, from 2008 and 2009, have concluded that there is not enough evidence to conclude that it is effective beyond the placebo effect.[231][232]

Acupuncture is generally safe when administered using Clean Needle Technique (CNT).[233] Although serious adverse effects are rare, acupuncture is not without risk.[233] Severe adverse effects, including very rarely death (five case reports), have been reported.[234]

Tui na (推拿) is a form of massage, based on the assumptions of TCM, from which shiatsu is thought to have evolved.[235] Techniques employed may include thumb presses, rubbing, percussion, and assisted stretching.

Qìgōng (气功; 氣功) is a TCM system of exercise and meditation that combines regulated breathing, slow movement, and focused awareness, purportedly to cultivate and balance qi.[236] One branch of qigong is qigong massage, in which the practitioner combines massage techniques with awareness of the acupuncture channels and points.[237][238]

Qi is air, breath, energy, or primordial life source that is neither matter or spirit. While Gong is a skillful movement, work, or exercise of the qi.[239]

Cupping (拔罐; báguàn) is a type of Chinese massage, consisting of placing several glass "cups" (open spheres) on the body. A match is lit and placed inside the cup and then removed before placing the cup against the skin. As the air in the cup is heated, it expands, and after placing in the skin, cools, creating lower pressure inside the cup that allows the cup to stick to the skin via suction.[240] When combined with massage oil, the cups can be slid around the back, offering "reverse-pressure massage".

Gua sha (刮痧; guāshā) is abrading the skin with pieces of smooth jade, bone, animal tusks or horns or smooth stones; until red spots then bruising cover the area to which it is done. It is believed that this treatment is for almost any ailment. The red spots and bruising take three to ten days to heal, there is often some soreness in the area that has been treated.[241]

Diē-dǎ (跌打) or Dit Da, is a traditional Chinese bone-setting technique, usually practiced by martial artists who know aspects of Chinese medicine that apply to the treatment of trauma and injuries such as bone fractures, sprains, and bruises. Some of these specialists may also use or recommend other disciplines of Chinese medical therapies if serious injury is involved. Such practice of bone-setting (正骨; 整骨) is not common in the West.

The concepts yin and yang are associated with different classes of foods, and tradition considers it important to consume them in a balanced fashion.

Many governments have enacted laws to regulate TCM practice.

From 1 July 2012 Chinese medicine practitioners must be registered under the national registration and accreditation scheme with the Chinese Medicine Board of Australia and meet the Board's Registration Standards, to practice in Australia.[242]

TCM is regulated in five provinces in Canada: Alberta, British Columbia,[243] Ontario,[244] Quebec, and Newfoundland & Labrador.

The National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine was created in 1949, which then absorbed existing TCM management in 1986 with major changes in 1998.[245][246]

China's National People's Congress Standing Committee passed the country's first law on TCM in 2016, which came into effect on 1 July 2017. The new law standardized TCM certifications by requiring TCM practitioners to (i) pass exams administered by provincial-level TCM authorities, and (ii) obtain recommendations from two certified practitioners. TCM products and services can be advertised only with approval from the local TCM authority.[247]

During British rule, Chinese medicine practitioners in Hong Kong were not recognized as "medical doctors", which means they could not issue prescription drugs, give injections, etc. However, TCM practitioners could register and operate TCM as "herbalists".[248] The Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong was established in 1999. It regulates the compounds and professional standards for TCM practitioners. All TCM practitioners in Hong Kong are required to register with the council. The eligibility for registration includes a recognised 5-year university degree of TCM, a 30-week minimum supervised clinical internship, and passing the licensing exam.[249]

Currently, the approved Chinese medicine institutions are HKU, CUHK and HKBU.[250]

The Portuguese Macau government seldom interfered in the affairs of Chinese society, including with regard to regulations on the practice of TCM. There were a few TCM pharmacies in Macau during the colonial period. In 1994, the Portuguese Macau government published Decree-Law no. 53/94/M that officially started to regulate the TCM market. After the sovereign handover, the Macau S.A.R. government also published regulations on the practice of TCM.[clarification needed] In 2000, Macau University of Science and Technology and Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine established the Macau College of Traditional Chinese Medicine to offer a degree course in Chinese medicine.[251]

In 2022, a new law regulating TCM, Law no. 11/2021, came into effect. The same law also repealed Decree-Law no. 53/94/M.[252][253]