Azerbaiyanos ( / ˌ æ z ər b aɪ ˈ dʒ æ n i , - ɑː n i / ; azerbaiyanos : Azərbaycanlılar , آذربایجانلیلار ), azeríes ( Azərilər , آذریلر ), o turcos azerbaiyanos ( Azərbaycan Türk ləri , آذربایجان تۆرکلری ) [47] [48 ] [49] son un grupo étnico turco que vive principalmente en la región de Azerbaiyán en el noroeste de Irán y la República de Azerbaiyán . Son predominantemente musulmanes chiítas . [44] Constituyen el grupo étnico más grande de la República de Azerbaiyán y el segundo grupo étnico más grande de los vecinos Irán y Georgia . [50] Hablan el idioma azerbaiyano , perteneciente a la rama oghuz de las lenguas turcas .

Tras las guerras ruso-persas de 1813 y 1828 , los territorios del Irán Qajar en el Cáucaso fueron cedidos al Imperio ruso y los tratados de Gulistán en 1813 y Turkmenchay en 1828 finalizaron las fronteras entre Rusia e Irán. [51] [52] Después de más de 80 años de estar bajo el Imperio ruso en el Cáucaso, se estableció la República Democrática de Azerbaiyán en 1918, que definió el territorio de la República de Azerbaiyán.

Se cree que Azerbaiyán debe su nombre a Atropates , un sátrapa (gobernador) persa [53] [54] [55] que gobernó en Atropatene (actual Azerbaiyán iraní ) alrededor del año 321 a . C. [56] [57] : 2 El nombre Atropates es la forma helenística del antiguo persa Aturpat , que significa 'guardián del fuego ' [58], un compuesto de ātūr ( ![]() ) 'fuego' (más tarde ādur (آذر) en persa nuevo (temprano) , y hoy se pronuncia āzar ) [59] + -pat (

) 'fuego' (más tarde ādur (آذر) en persa nuevo (temprano) , y hoy se pronuncia āzar ) [59] + -pat (![]() ) sufijo para -guardián, -señor, -amo [59] ( -pat en persa medio temprano , -bod (بُد) en persa nuevo).

) sufijo para -guardián, -señor, -amo [59] ( -pat en persa medio temprano , -bod (بُد) en persa nuevo).

El nombre actual Azerbaiyán es la forma arabizada de Āzarpāyegān ( persa : آذرپایگان) que significa 'los guardianes del fuego ', que más tarde se convirtió en Azerbaiyán ( persa : آذربایجان) debido al cambio fonémico de /p/ a /b/ y /g/ a /dʒ/ que es el resultado de las influencias árabes medievales que siguieron a la invasión árabe de Irán , y se debe a la falta del fonema /p/ y /g/ en el idioma árabe . [60] La palabra Azarpāyegān en sí proviene en última instancia del persa antiguo Āturpātakān ( persa : آتورپاتکان) [61] [62] que significa 'la tierra asociada con (el sátrapa) Aturpat' o 'la tierra de los guardianes del fuego' ( -an , aquí confuso en -kān , es un sufijo para asociación o para formar adverbios y plurales; [59] p. ej.: Gilan 'tierra asociada con la gente de Gil '). [63]

El etnónimo moderno "azerbaiyano" o "azerí" se refiere a los pueblos turcos de la región histórica noroccidental de Azerbaiyán (también conocida como Azerbaiyán iraní) y la República de Azerbaiyán . [64] Históricamente se llamaban a sí mismos o eran referidos por otros como musulmanes y/o turcos. También se los conocía como Ajam (que significa de Irán), utilizando el término incorrectamente para denotar su creencia chiita en lugar de su identidad étnica. [65] Cuando el Cáucaso meridional se convirtió en parte del Imperio ruso en el siglo XIX, las autoridades rusas, que tradicionalmente se referían a todos los pueblos turcos como tártaros , definieron a los tártaros que vivían en la región del Transcáucaso como tártaros caucásicos o más raramente [66] tártaros de Aderbeijanskie (Адербейджанские) o incluso [67] tártaros persas para distinguirlos de otros grupos turcos y de los hablantes de persa de Irán. [67] [68] El Diccionario enciclopédico ruso Brockhaus y Efron , escrito en la década de 1890, también se refería a los tártaros en Azerbaiyán como Aderbeijans (адербейджаны), [69] pero señaló que el término no había sido ampliamente adoptado. [70] Este etnónimo también fue utilizado por Joseph Deniker en 1900. [71] En las publicaciones en idioma azerbaiyano, la expresión "nación azerbaiyana" refiriéndose a los que eran conocidos como tártaros del Cáucaso apareció por primera vez en el periódico Kashkul en 1880. [72]

Durante el período soviético temprano, el término " tártaros de Transcaucasia " fue suplantado por "turcos azerbaiyanos" y finalmente "azerbaiyanos". [73] [74] [75] Durante algún tiempo después, el término "azerbaiyanos" se aplicó a todos los musulmanes de habla turca en Transcaucasia, desde los turcos mesjetios en el suroeste de Georgia , hasta los terekemes del sur de Daguestán , así como los tats y talysh asimilados . [74] La designación temporal de los turcos mesjetios como "azerbaiyanos" probablemente estaba relacionada con el marco administrativo existente de la RSFS de Transcaucasia , ya que la RSS de Azerbaiyán fue uno de sus miembros fundadores. [76] Después del establecimiento de la RSS de Azerbaiyán, [77] por orden del líder soviético Stalin , el "nombre del idioma formal" de la RSS de Azerbaiyán también fue "cambiado de turco a azerbaiyano". [77]

Los nombres chechenos e ingusetios para los azerbaiyanos [a] son Ghezloy / Ghoazloy ( Гүзлой / Гүоазлой ) y Ghazaroy / Ghazharey ( Гүжарой / Гүжарей ). El primero se remonta al nombre de Qizilbash mientras que el segundo se remonta al nombre de Qajars , habiendo surgido presumiblemente en las lenguas chechena e ingusetio durante el reinado de los Qajars en Irán en los siglos XVIII y XIX. [79]

Los antiguos residentes de la zona hablaban azerí antiguo , una rama iraní de las lenguas indoeuropeas . [80] En el siglo XI d. C., con las conquistas selyúcidas, las tribus turcas oghuz comenzaron a trasladarse a través de la meseta iraní hacia el Cáucaso y Anatolia. La afluencia de oghuz y otras tribus turcomanas se acentuó aún más con la invasión mongola. [81] Estas tribus turcomanas se extendieron en grupos más pequeños, varios de los cuales se establecieron en el Cáucaso e Irán, lo que resultó en la turquificación de la población local. Con el tiempo, se convirtieron al Islam chiita y gradualmente absorbieron Azerbaiyán y Shirvan . [82]

Se cree que las tribus albanesas de habla caucásica fueron los primeros habitantes de la región al norte del río Aras, donde se encuentra la República de Azerbaiyán. [83] La región también vio asentamientos escitas en el siglo IX a. C., después de lo cual los medos llegaron a dominar el área al sur del río Aras . [84]

Alejandro Magno derrotó a los aqueménidas en el 330 a. C., pero permitió que el sátrapa medo Atropates permaneciera en el poder. Tras la decadencia de los seléucidas en Persia en el 247 a. C., un reino armenio ejerció el control sobre partes de la Albania caucásica . [85] Los albaneses caucásicos establecieron un reino en el siglo I a. C. y permanecieron en gran medida independientes hasta que los sasánidas persas convirtieron su reino en un estado vasallo en el 252 d. C. [2] : 38 El gobernante de la Albania caucásica, el rey Urnayr , fue a Armenia y luego adoptó oficialmente el cristianismo como religión estatal en el siglo IV d. C., y Albania siguió siendo un estado cristiano hasta el siglo VIII. [86] [87]

El control sasánida terminó con su derrota por el califato Rashidun en 642 d. C. a través de la conquista musulmana de Persia . [88] Los árabes hicieron de la Albania caucásica un estado vasallo después de que la resistencia cristiana, liderada por el príncipe Javanshir , se rindiera en 667. [2] : 71 Entre los siglos IX y X, los autores árabes comenzaron a referirse a la región entre los ríos Kura y Aras como Arran . [2] : 20 Durante este tiempo, los árabes de Basora y Kufa llegaron a Azerbaiyán y se apoderaron de tierras que los pueblos indígenas habían abandonado; los árabes se convirtieron en una élite terrateniente. [89] : 48 La conversión al Islam fue lenta ya que la resistencia local persistió durante siglos y el resentimiento creció a medida que pequeños grupos de árabes comenzaron a migrar a ciudades como Tabriz y Maraghah . Esta afluencia desencadenó una importante rebelión en el Azerbaiyán iraní entre 816 y 837, liderada por un plebeyo zoroastriano iraní llamado Babak Khorramdin . [90] Sin embargo, a pesar de los focos de resistencia continua, la mayoría de los habitantes de Azerbaiyán se convirtieron al Islam. Más tarde, en los siglos X y XI, partes de Azerbaiyán fueron gobernadas por la dinastía kurda de Shaddadid y los árabes Radawids .

A mediados del siglo XI, la dinastía seléucida derrocó el dominio árabe y estableció un imperio que abarcaba la mayor parte del suroeste de Asia . El período seléucida marcó la llegada de los nómadas oghuz a la región. El dominio emergente de la lengua turca quedó registrado en poemas épicos o dastans , el más antiguo de los cuales es el Libro de Dede Korkut , que relata historias alegóricas sobre los primeros turcos en el Cáucaso y Asia Menor . [2] : 45 El dominio turco fue interrumpido por los mongoles en 1227, pero regresó con los timúridas y luego los sunitas Qara Qoyunlū (turcomanos oveja negra) y Aq Qoyunlū (turcomanos oveja blanca), que dominaron Azerbaiyán, grandes partes de Irán, Anatolia oriental y otras partes menores de Asia occidental, hasta que los safávidas chiítas tomaron el poder en 1501. [2] : 113 [89] : 285

Los safávidas , que surgieron en los alrededores de Ardabil en el Azerbaiyán iraní y duraron hasta 1722, establecieron las bases del estado iraní moderno. [91] Los safávidas, junto con sus archirrivales otomanos , dominaron toda la región de Asia occidental y más allá durante siglos. En su apogeo bajo el Sha Abbas el Grande , rivalizó con su archirrival político e ideológico, el imperio otomano, en fuerza militar. Notable por sus logros en la construcción del estado, la arquitectura y las ciencias, el estado safávida se desmoronó debido a la decadencia interna (principalmente intrigas reales), levantamientos de minorías étnicas y presiones externas de los rusos y los eventualmente oportunistas afganos , que marcarían el final de la dinastía. Los safávidas alentaron y difundieron el Islam chiita, así como las artes y la cultura, y el Sha Abbas el Grande creó una atmósfera intelectual que, según algunos académicos, fue una nueva "edad de oro". [92] Reformó el gobierno y el ejército y respondió a las necesidades de la gente común. [92]

Después de la desintegración del Estado safávida, se produjo la conquista por parte de Nader Shah Afshar , un jefe chiita de Jorasán que redujo el poder del ghulat chiita y empoderó a una forma moderada de chiismo, [89] : 300 y, excepcionalmente conocido por su genio militar, hizo que Irán alcanzara su mayor extensión desde el Imperio sasánida . El breve reinado de Karim Khan vino a continuación, seguido por los Qajars , que gobernaron lo que hoy es la República de Azerbaiyán e Irán desde 1779. [2] : 106 Rusia se perfilaba como una amenaza para las posesiones persas y turcas en el Cáucaso en este período. Las guerras ruso-persas , a pesar de haber tenido ya conflictos militares menores en el siglo XVII, comenzaron oficialmente en el siglo XVIII y finalizaron a principios del siglo XIX con el Tratado de Gulistán de 1813 y el Tratado de Turkmenchay en 1828, que cedieron la porción caucásica del Irán Qajar al Imperio ruso . [57] : 17 Mientras que los azerbaiyanos en Irán se integraron a la sociedad iraní, los azerbaiyanos que solían vivir en Aran, fueron incorporados al Imperio ruso.

A pesar de la conquista rusa, durante todo el siglo XIX, la preocupación por la cultura , la literatura y la lengua iraníes siguió siendo generalizada entre los intelectuales chiítas y sunitas de las ciudades de Bakú , Ganja y Tiflis ( Tiflis , ahora Georgia), controladas por los rusos. [93] En el mismo siglo, en el Cáucaso oriental controlado por los rusos postiraníes, surgió una identidad nacional azerbaiyana a finales del siglo XIX. [94] En 1891, la idea de reconocerse como un "turco azerbaiyano" se popularizó por primera vez entre los tártaros del Cáucaso en el periódico Kashkül . [95] Los artículos impresos en Kaspiy y Kashkül en 1891 suelen considerarse las primeras expresiones de una identidad cultural azerbaiyana. [96]

La modernización, en comparación con los armenios y georgianos vecinos , se desarrolló lentamente entre los tártaros del Cáucaso ruso. Según el censo del Imperio ruso de 1897 , menos del cinco por ciento de los tártaros sabía leer o escribir. El intelectual y editor de periódicos Ali bey Huseynzade (1864-1940) encabezó una campaña para "turquificar, islamizar, modernizar" a los tártaros caucásicos, mientras que Mammed Said Ordubadi (1872-1950), otro periodista y activista, criticó la superstición entre los musulmanes. [97]

Después del colapso del Imperio ruso durante la Primera Guerra Mundial , se declaró la efímera República Federativa Democrática de Transcaucasia , que constituyó lo que hoy son las repúblicas de Azerbaiyán, Georgia y Armenia. A esto le siguieron las masacres de los Días de Marzo [99] [100] que tuvieron lugar entre el 30 de marzo y el 2 de abril de 1918 en la ciudad de Bakú y áreas adyacentes de la Gobernación de Bakú del Imperio ruso . [101] Cuando la república se disolvió en mayo de 1918, el partido líder Musavat adoptó el nombre de "Azerbaiyán" para la recién establecida República Democrática de Azerbaiyán , que fue proclamada el 27 de mayo de 1918, [102] por razones políticas, [103] [104] a pesar de que el nombre de "Azerbaiyán" se había utilizado para referirse a la región adyacente del noroeste contemporáneo de Irán . [105] [106] La ADR fue la primera república parlamentaria moderna en el mundo turco y el mundo musulmán . [99] [107] [108] Entre los logros importantes del Parlamento estuvo la extensión del sufragio a las mujeres, convirtiendo a Azerbaiyán en la primera nación musulmana en otorgar a las mujeres derechos políticos iguales a los de los hombres. [107] Otro logro importante del ADR fue el establecimiento de la Universidad Estatal de Bakú , que fue la primera universidad de tipo moderno fundada en el Oriente musulmán. [107]

En marzo de 1920, era obvio que la Rusia soviética atacaría la tan necesaria Bakú. Vladimir Lenin dijo que la invasión estaba justificada ya que la Rusia soviética no podría sobrevivir sin el petróleo de Bakú . [109] [110] El Azerbaiyán independiente duró solo 23 meses hasta que el 11.º Ejército Rojo Soviético bolchevique lo invadió, estableciendo la República Socialista Soviética de Azerbaiyán el 28 de abril de 1920. Aunque la mayor parte del recién formado ejército azerbaiyano estaba comprometido en sofocar una revuelta armenia que acababa de estallar en Karabaj , los azeríes no rindieron su breve independencia de 1918-20 rápida ni fácilmente. Hasta 20.000 soldados azerbaiyanos murieron resistiendo lo que fue efectivamente una reconquista rusa. [111]

La breve independencia obtenida por la efímera República Democrática de Azerbaiyán en 1918-1920 fue seguida por más de 70 años de gobierno soviético . [112] : 91 Sin embargo, fue en el período soviético temprano cuando finalmente se forjó la identidad nacional azerbaiyana. [94] Después de la restauración de la independencia en octubre de 1991, la República de Azerbaiyán se vio envuelta en una guerra con su vecina Armenia por la región de Nagorno-Karabaj. [112] : 97

La primera guerra de Nagorno-Karabaj provocó el desplazamiento de aproximadamente 725.000 azerbaiyanos y entre 300.000 y 500.000 armenios tanto de Azerbaiyán como de Armenia. [113] Como resultado de la guerra de Nagorno-Karabaj de 2020 , Azerbaiyán recuperó 5 ciudades, 4 pueblos y 286 aldeas de la región. [114] Según el acuerdo de alto el fuego de Nagorno-Karabaj de 2020 , los desplazados internos y los refugiados deberán regresar al territorio de Nagorno-Karabaj y las zonas adyacentes bajo la supervisión del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados. [115]

En Irán, azerbaiyanos como Sattar Khan buscaron una reforma constitucional. [116] La Revolución Constitucional Persa de 1906-11 sacudió a la dinastía Qajar. Se fundó un parlamento ( Majlis ) gracias a los esfuerzos de los constitucionalistas y aparecieron periódicos prodemocráticos. El último Sha de la dinastía Qajar fue pronto derrocado en un golpe militar dirigido por Reza Khan . En su afán por imponer la homogeneidad nacional en un país donde la mitad de la población eran minorías étnicas, Reza Shah prohibió en rápida sucesión el uso del idioma azerbaiyano en las escuelas, representaciones teatrales, ceremonias religiosas y libros. [117]

Tras el derrocamiento de Reza Shah en septiembre de 1941, las fuerzas soviéticas tomaron el control de Azerbaiyán iraní y ayudaron a establecer el Gobierno Popular de Azerbaiyán , un estado cliente bajo el liderazgo de Sayyid Jafar Pishevari respaldado por Azerbaiyán soviético . La presencia militar soviética en Azerbaiyán iraní tenía como objetivo principal asegurar la ruta de suministro de los Aliados durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Preocupados por la continua presencia soviética después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña presionaron a los soviéticos para que se retiraran a fines de 1946. Inmediatamente después, el gobierno iraní recuperó el control de Azerbaiyán iraní . Según el profesor Gary R. Hess, los azerbaiyanos locales favorecían el gobierno iraní, mientras que los soviéticos renunciaron a Azerbaiyán iraní debido al exagerado sentimiento de autonomía y al petróleo como su máxima prioridad. [118]

En muchas referencias, los azerbaiyanos son designados como un pueblo turco , [45] [119] mientras que algunas fuentes describen el origen de los azerbaiyanos como "poco claro", [120] principalmente caucásicos, [121] principalmente iraníes, [122] [123] una mezcla de albaneses caucásicos y turcos, [124] y una mezcla de elementos caucásicos, iraníes y turcos. [125] El historiador y orientalista ruso Vladimir Minorsky escribe que en gran parte las poblaciones iraníes y caucásicas se volvieron de habla turca después de la ocupación oghuz de la región, aunque los rasgos característicos de la lengua turca local, como las entonaciones persas y el desprecio por la armonía vocálica, eran un remanente de la población no turca. [126]

Las investigaciones históricas sugieren que el antiguo idioma azerí , perteneciente a la rama noroccidental de las lenguas iraníes y que se cree que desciende del idioma de los medos, [127] ganó popularidad gradualmente y se habló ampliamente en dicha región durante muchos siglos. [128] [129] [130] [131] [132]

Se cree que algunos azerbaiyanos de la República de Azerbaiyán descienden de los habitantes de la Albania caucásica , un antiguo país ubicado en la región oriental del Cáucaso , y de varios pueblos iraníes que se asentaron en la región. [133] Afirman que hay evidencia de que, debido a repetidas invasiones y migraciones, la población aborigen caucásica puede haber sido gradualmente asimilada cultural y lingüísticamente, primero por los pueblos iraníes, como los persas , [134] y más tarde por los turcos oghuz . Se ha aprendido considerable información sobre los albaneses caucásicos, incluyendo su idioma , historia, conversión temprana al cristianismo y relaciones con los armenios y georgianos , bajo cuya fuerte influencia religiosa y cultural los albaneses caucásicos llegaron en los siglos siguientes. [135] [136]

La turquificación de la población no turca se deriva de los asentamientos turcos en el área ahora conocida como Azerbaiyán, que comenzaron y se aceleraron durante el período selyúcida . [45] La migración de turcos oghuz desde el actual Turkmenistán , que está atestiguada por la similitud lingüística, se mantuvo alta durante el período mongol, ya que muchas tropas bajo los ilkhanidas eran turcas. En el período safávida , la naturaleza turca de Azerbaiyán aumentó con la influencia de los qizilbash , una asociación de las tribus nómadas turcomanas [137] que fue la columna vertebral del Imperio safávida.

Según los estudiosos soviéticos, la turquización de Azerbaiyán se completó en gran medida durante el período iljánida. Faruk Sümer postula tres períodos en los que tuvo lugar la turquización: selyúcida, mongol y posmongol (Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu y Safávida). En los dos primeros, las tribus turcas oghuz avanzaron o fueron expulsadas a Anatolia y Arran. En el último período, a los elementos turcos de Irán (oghuz, con mezclas menores de uigures, qipchaq, qarluq, así como mongoles turquizados) se unieron los turcos de Anatolia que migraron de regreso a Irán. Esto marcó la etapa final de la turquización. [45]

El historiador árabe del siglo X Al-Masudi atestiguó la antigua lengua azerí y describió que la región de Azerbaiyán estaba habitada por persas . [138] La evidencia arqueológica indica que la religión iraní del zoroastrismo era prominente en todo el Cáucaso antes del cristianismo y el islam. [139] [140] [141] Según la Enciclopedia Iranica , los azerbaiyanos se originan principalmente de los hablantes iraníes anteriores, que todavía existen hasta el día de hoy en menor número, y una migración masiva de turcos oghuz en los siglos XI y XII turquificó gradualmente Azerbaiyán y Anatolia. [142]

Según la Enciclopedia Británica, los azerbaiyanos son de ascendencia mixta, originarios de la población indígena del este de Transcaucasia y posiblemente de los medos del norte de Irán. [143] Hay evidencia de que, debido a repetidas invasiones y migraciones, los aborígenes caucásicos pueden haber sido asimilados culturalmente, primero por los pueblos iraníes antiguos y más tarde por los oghuz. Se ha aprendido considerable información sobre los albaneses caucásicos, incluyendo su idioma, historia y conversión temprana al cristianismo . El idioma udi , que todavía se habla en Azerbaiyán, puede ser un remanente del idioma de los albaneses. [144]

Los genomas contemporáneos de Asia occidental, una región que incluye Azerbaiyán, han sido muy influenciados por las primeras poblaciones agrícolas de la zona; los movimientos de población posteriores, como los de hablantes de turco, también contribuyeron. [145] Sin embargo, a partir de 2017, no existe un estudio de secuenciación del genoma completo de Azerbaiyán; limitaciones de muestreo como estas impiden formar una "imagen a escala más fina de la historia genética de la región". [145]

Un estudio de 2014 que comparó la genética de las poblaciones de Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaiyán (que se agruparon como " Ruta de la Seda Occidental "), Kazajstán, Uzbekistán y Tayikistán (agrupadas como "Ruta de la Seda Oriental") encontró que las muestras de Azerbaiyán eran el único grupo de la Ruta de la Seda Occidental que mostraba una contribución significativa de la Ruta de la Seda Oriental, a pesar de la agrupación general con las otras muestras de la Ruta de la Seda Occidental. Se estimó que la contribución oriental a la genética azerbaiyana fue hace aproximadamente 25 generaciones, lo que corresponde a la época de la expansión mongola . [146]

Un estudio de 2002 centrado en once marcadores del cromosoma Y sugirió que los azerbaiyanos están genéticamente más relacionados con sus vecinos geográficos caucásicos que con sus vecinos lingüísticos. [147] Los azerbaiyanos iraníes son genéticamente más similares a los azerbaiyanos del norte y a la población turca vecina que a las poblaciones turcomanas geográficamente distantes. [148] Las poblaciones de habla iraní de Azerbaiyán (los talysh y los tats ) son genéticamente más cercanas a los azerbaiyanos de la República que a otras poblaciones de habla iraní ( los persas y los kurdos de Irán, los osetios y los tayikos ). [149] Varios estudios genéticos sugirieron que los azerbaiyanos se originan de una población nativa residente durante mucho tiempo en el área que adoptó una lengua turca a través del reemplazo de la lengua , incluida la posibilidad de un escenario de dominio de la élite. [150] [151] [147] Sin embargo, el reemplazo de la lengua en Azerbaiyán (y en Turquía) podría no haber estado de acuerdo con el modelo de dominio de la élite, con una contribución estimada de Asia Central a Azerbaiyán del 18% para las mujeres y del 32% para los hombres. [152] Un estudio posterior también sugirió una contribución del 33% de Asia Central a Azerbaiyán. [153]

Un estudio de 2001 que examinó el primer segmento hipervariable del ADNmt sugirió que "las relaciones genéticas entre las poblaciones del Cáucaso reflejan relaciones geográficas más que lingüísticas", siendo los armenios y azerbaiyanos "los más estrechamente relacionados con sus vecinos geográficos más cercanos". [154] Otro estudio de 2004 que examinó 910 ADNmt de 23 poblaciones en la meseta iraní, el valle del Indo y Asia central sugirió que las poblaciones "al oeste de la cuenca del Indo, incluidas las de Irán, Anatolia [Turquía] y el Cáucaso, exhiben una composición de linaje de ADNmt común, que consiste principalmente en linajes euroasiáticos occidentales, con una contribución muy limitada del sur de Asia y Eurasia oriental". [155] Si bien el análisis genético del ADNmt indica que las poblaciones caucásicas están genéticamente más cerca de los europeos que de los habitantes del Cercano Oriente, los resultados del cromosoma Y indican una afinidad más cercana con los grupos del Cercano Oriente. [147]

La variedad de haplogrupos en la región puede reflejar una mezcla genética histórica, [156] quizás como resultado de migraciones masculinas invasivas. [147]

En un estudio comparativo (2013) sobre la diversidad completa del ADN mitocondrial en los iraníes se ha indicado que los azeríes iraníes están más relacionados con la gente de Georgia que con otros iraníes , así como con los armenios . Sin embargo, el mismo gráfico de escala multidimensional muestra que los azeríes del Cáucaso, a pesar de su supuesto origen común con los azeríes iraníes, "ocupan una posición intermedia entre los grupos azeríes/georgianos y turcos/iraníes". [157]

Un estudio de 2007 que investigó el antígeno leucocitario humano de clase dos sugirió que "no se observó ninguna relación genética cercana entre los azeríes de Irán y los pueblos de Turquía o de Asia central". [158] Un estudio de 2017 que investigó los alelos HLA colocó las muestras de azeríes en el noroeste de Irán "en el grupo mediterráneo cerca de los kurdos, gorganes, chuvasos (sur de Rusia, hacia el norte del Cáucaso), iraníes y poblaciones del Cáucaso (svanes y georgianos)". Esta población mediterránea incluye "poblaciones turcas y caucásicas". Las muestras azeríes también estaban en una "posición entre las muestras mediterráneas y de Asia central", lo que sugiere que el "proceso de turquificación causado por las tribus turcas oghuz también podría contribuir al trasfondo genético del pueblo azerí". [159]

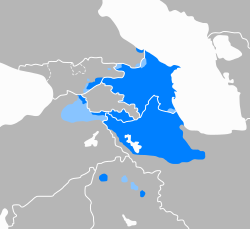

La gran mayoría de los azerbaiyanos viven en la República de Azerbaiyán y Azerbaiyán iraní . Entre 12 y 23 millones de azerbaiyanos viven en Irán, [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] principalmente en las provincias del noroeste. Aproximadamente 9,1 millones de azerbaiyanos se encuentran en la República de Azerbaiyán. Una diáspora de más de un millón se extiende por el resto del mundo. Según Ethnologue , hay más de 1 millón de hablantes del dialecto azerbaiyano del norte en el sur de Daguestán , Estonia, Georgia, Kazajstán, Kirguistán, Rusia propiamente dicha, Turkmenistán y Uzbekistán. [160] No se registraron azerbaiyanos en el censo de 2001 en Armenia, [161] donde el conflicto de Nagorno-Karabaj resultó en cambios de población. Otras fuentes, como los censos nacionales, confirman la presencia de azerbaiyanos en los demás estados de la ex Unión Soviética .

Los azerbaiyanos son, con diferencia, el grupo étnico más numeroso de la República de Azerbaiyán (más del 90 %), y constituyen la segunda comunidad más numerosa de azerbaiyanos étnicos después del vecino Irán. La tasa de alfabetización es muy elevada y se estima que llega al 99,5 %. [162] Azerbaiyán comenzó el siglo XX con instituciones basadas en las de Rusia y la Unión Soviética, con una política oficial de ateísmo y un estricto control estatal sobre la mayoría de los aspectos de la sociedad. Desde la independencia, existe un sistema secular.

Azerbaiyán se ha beneficiado de la industria petrolera, pero los altos niveles de corrupción han impedido una mayor prosperidad para la población. [163] A pesar de estos problemas, hay un renacimiento financiero en Azerbaiyán, ya que las predicciones económicas positivas y una oposición política activa parecen decididas a mejorar las vidas de los azerbaiyanos promedio. [164] [165]

El número exacto de azerbaiyanos en Irán es muy discutido. Desde principios del siglo XX, los sucesivos gobiernos iraníes han evitado publicar estadísticas sobre los grupos étnicos. [166] Las estimaciones no oficiales de la población de azerbaiyanos en Irán rondan el 16% del área propuesta por la CIA y la Biblioteca del Congreso. [167] [168] Una encuesta independiente en 2009 situó la cifra en torno al 20-22%. [169] Según la iranóloga Victoria Arakelova en la revista arbitrada Iran and the Caucasus , la estimación del número de azerbaiyanos en Irán se ha visto obstaculizada durante años desde la disolución de la Unión Soviética , cuando la "teoría una vez inventada de la llamada nación separada (es decir, los ciudadanos de la República de Azerbaiyán, los llamados azerbaiyanos y los azaríes en Irán), se actualizó de nuevo (véase en detalle Reza 1993)". Arakelova añade que el número de azeríes en Irán, que en las publicaciones políticamente sesgadas se presenta como “la minoría azerbaiyana de Irán”, se considera la “parte altamente especulativa de esta teoría”. Aunque todos los censos de población iraníes distinguen exclusivamente a las minorías religiosas, numerosas fuentes han presentado cifras diferentes sobre las comunidades de habla turca de Irán, sin “ninguna justificación ni referencias concretas”. [12]

A principios de los años 90, justo después del colapso de la Unión Soviética, la cifra más popular que reflejaba el número de "azerbaiyanos" en Irán era de treinta y tres millones, en un momento en que la población total de Irán apenas alcanzaba los sesenta millones. Por lo tanto, en ese momento, la mitad de los ciudadanos de Irán eran considerados "azerbaiyanos". Poco después, esta cifra fue reemplazada por la de treinta millones, que se convirtió en "casi un recuento normativo sobre la situación demográfica en Irán, que circuló ampliamente no solo entre académicos y analistas políticos, sino también en los círculos oficiales de Rusia y Occidente". Luego, en la década de 2000, la cifra disminuyó a 20 millones; esta vez, al menos dentro del establishment político ruso, la cifra se convirtió en "firmemente fija". Esta cifra, agrega Arakelova, se ha utilizado ampliamente y se ha mantenido actualizada, solo con algunos ajustes menores. Sin embargo, un vistazo rápido a la situación demográfica de Irán muestra que todas estas cifras han sido manipuladas y fueron "definitivamente inventadas con fines políticos". Arakelova estima que el número de azeríes, es decir, "azerbaiyanos" en Irán basándose en la demografía de la población de Irán, es de entre 6 y 6,5 millones. [12]

Los azerbaiyanos en Irán se encuentran principalmente en las provincias del noroeste: Azerbaiyán Occidental , Azerbaiyán Oriental , Ardabil , Zanjan , partes de Hamadan , Qazvin y Markazi . [168] Las minorías azerbaiyanas viven en los condados de Qorveh [170] y Bijar [171] del Kurdistán , en Gilan , [172] [173] [174] [175] como enclaves étnicos en Galugah en Mazandaran , alrededor de Lotfabad y Dargaz en Razavi Khorasan , [176] y en la ciudad de Gonbad-e Qabus en Golestán . [177] También se pueden encontrar grandes poblaciones azerbaiyanas en el centro de Irán ( Teherán # Alborz ) debido a la migración interna. Los azerbaiyanos representan el 25% [178] de la población de Teherán y el 30,3% [179] - 33% [180] [181] de la población de la provincia de Teherán , donde los azerbaiyanos se encuentran en todas las ciudades. [182] Son los grupos étnicos más numerosos después de los persas en Teherán y la provincia de Teherán. [183] [184] Arakelova señala que el "cliché" generalizado entre los residentes de Teherán sobre el número de azerbaiyanos en la ciudad ("la mitad de Teherán está formada por azerbaiyanos"), no puede tomarse "seriamente en consideración". Arakelova añade que el número de habitantes de Teherán que han emigrado de las zonas noroccidentales de Irán, que actualmente son hablantes de persa "en su mayor parte", no es más que "varios cientos de miles", siendo el máximo un millón. [12] Los azerbaiyanos también han emigrado y se han reasentado en gran número en Jorasán , [185] especialmente en Mashhad . [186]

En general, los académicos consideraban a los azerbaiyanos en Irán como "una minoría lingüística bien integrada" antes de la Revolución Islámica de Irán . [187] [188] A pesar de la fricción, los azerbaiyanos en Irán llegaron a estar bien representados en todos los niveles de las "jerarquías políticas, militares e intelectuales, así como en la jerarquía religiosa". [166]

El resentimiento llegó con las políticas Pahlavi que suprimieron el uso del idioma azerbaiyano en el gobierno local, las escuelas y la prensa. [189] Sin embargo, con el advenimiento de la Revolución iraní en 1979, el énfasis se alejó del nacionalismo cuando el nuevo gobierno destacó la religión como el principal factor unificador. Las instituciones teocráticas islámicas dominan casi todos los aspectos de la sociedad. El idioma azerbaiyano y su literatura están prohibidos en las escuelas iraníes. [190] [191] Hay signos de malestar civil debido a las políticas del gobierno iraní en Azerbaiyán iraní y una mayor interacción con otros azerbaiyanos en Azerbaiyán y las transmisiones por satélite de Turquía y otros países turcos han revivido el nacionalismo azerbaiyano. [192] En mayo de 2006, Azerbaiyán iraní fue testigo de disturbios por la publicación de una caricatura que representaba a una cucaracha hablando azerbaiyano [193] que muchos azerbaiyanos encontraron ofensiva. [194] [195] La caricatura fue dibujada por Mana Neyestani , un azerí, que fue despedido junto con su editor como resultado de la controversia. [196] [197] Uno de los principales incidentes que ocurrieron recientemente fueron las protestas azeríes en Irán (2015) que comenzaron en noviembre de 2015, después de que el programa de televisión infantil Fitileha se transmitiera el 6 de noviembre en la televisión estatal, que ridiculizaba y se burlaba del acento y el idioma de los azeríes e incluía chistes ofensivos. [198] Como resultado, cientos de azeríes étnicos protestaron contra un programa en la televisión estatal que contenía lo que consideran un insulto étnico. Se celebraron manifestaciones en Tabriz , Urmia , Ardabil y Zanjan , así como en Teherán y Karaj . La policía en Irán se enfrentó a los manifestantes, lanzó gases lacrimógenos para dispersar a las multitudes y muchos manifestantes fueron arrestados. Uno de los manifestantes, Ali Akbar Murtaza, supuestamente "murió a causa de las heridas" en Urmia. [199] También se celebraron protestas frente a las embajadas iraníes en Estambul y Bakú . [200] El director de la emisora estatal del país, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), Mohammad Sarafraz, se disculpó por emitir el programa, cuya emisión fue posteriormente interrumpida. [201]

Los azerbaiyanos son una comunidad intrínseca de Irán y su estilo de vida se parece mucho al de los persas :

El estilo de vida de los azerbaiyanos urbanos no difiere del de los persas, y en las ciudades de población mixta hay un número considerable de matrimonios mixtos entre las clases altas. De manera similar, las costumbres entre los habitantes de las aldeas azerbaiyanas no parecen diferir marcadamente de las de los habitantes de las aldeas persas. [168]

Los azeríes son famosos por su actividad comercial y sus locuaces voces se escuchan en los bazares de todo Irán. Los hombres azeríes de más edad llevan el tradicional sombrero de lana, y su música y sus bailes se han convertido en parte de la cultura dominante. Los azeríes están bien integrados y muchos azeríes-iraníes son destacados en la literatura , la política y el mundo clerical persas . [202]

Existe un importante comercio transfronterizo entre Azerbaiyán e Irán, y los azerbaiyanos de Azerbaiyán van a Irán a comprar bienes más baratos, pero la relación era tensa hasta hace poco. [190] Sin embargo, las relaciones han mejorado significativamente desde que el gobierno de Rouhani asumió el cargo.

Existen al menos diez grupos étnicos azerbaiyanos, cada uno de los cuales tiene particularidades en la economía, la cultura y la vida cotidiana. Algunos grupos étnicos azerbaiyanos continuaron existiendo en el último cuarto del siglo XIX.

Principales grupos étnicos azerbaiyanos:

En Azerbaiyán, a las mujeres se les concedió el derecho a votar en 1917. [204] Las mujeres han alcanzado la igualdad al estilo occidental en las principales ciudades como Bakú , aunque en las zonas rurales siguen existiendo puntos de vista más reaccionarios. [164] La violencia contra las mujeres, incluida la violación, rara vez se denuncia, especialmente en las zonas rurales, al igual que en otras partes de la ex Unión Soviética. [205] En Azerbaiyán, el velo se abandonó durante el período soviético. [206] Las mujeres están subrepresentadas en los cargos electivos, pero han alcanzado altos puestos en el parlamento. Una mujer azerbaiyana es la presidenta del Tribunal Supremo de Azerbaiyán, y otras dos son magistradas del Tribunal Constitucional. En las elecciones de 2010, las mujeres constituyeron el 16% de todos los diputados (veinte escaños en total) en la Asamblea Nacional de Azerbaiyán . [207] El aborto está disponible a pedido en la República de Azerbaiyán. [208] La defensora de los derechos humanos desde 2002, Elmira Süleymanova , es una mujer.

In Iran, a groundswell of grassroots movements have sought gender equality since the 1980s.[168] Protests in defiance of government bans are dispersed through violence, as on 12 June 2006 when female demonstrators in Haft Tir Square in Tehran were beaten.[209] Past Iranian leaders, such as the reformer ex-president Mohammad Khatami promised women greater rights, but the Guardian Council of Iran opposes changes that they interpret as contrary to Islamic doctrine. In the 2004 legislative elections, nine women were elected to parliament (Majlis), eight of whom were conservatives.[210] The social fate of Azerbaijani women largely mirrors that of other women in Iran.[citation needed]

The Azerbaijanis speak the Azerbaijani language, a Turkic language descended from the branches of Oghuz Turkic language that became established in Azerbaijan in the 11th and 12th centuries CE. The Azerbaijani language is closely related to Qashqai, Gagauz, Turkish, Turkmen and Crimean Tatar, sharing varying degrees of mutual intelligibility with each of those languages.[212] Certain lexical and grammatical differences formed within the Azerbaijani language as spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iran, after nearly two centuries of separation between the communities speaking the language; mutual intelligibility, however, has been preserved.[213] Additionally, the Turkish and Azerbaijani languages are mutually intelligible to a high enough degree that their speakers can have simple conversations without prior knowledge of the other.[112]

Early literature was mainly based on oral tradition, and the later compiled epics and heroic stories of Dede Korkut probably derive from it. The first written, classical Azerbaijani literature arose after the Mongol invasion, while the first accepted Oghuz Turkic text goes back to the 15th century.[214] Some of the earliest Azerbaijani writings trace back to the poet Nasimi (died 1417) and then decades later Fuzûlî (1483–1556). Ismail I, Shah of Safavid Iran wrote Azerbaijani poetry under the pen name Khatâ'i.

Modern Azerbaijani literature continued with a traditional emphasis upon humanism, as conveyed in the writings of Samad Vurgun, Shahriar, and many others.[215]

Azerbaijanis are generally bilingual, often fluent in either Russian (in Azerbaijan) or Persian (in Iran) in addition to their native Azerbaijani. As of 1996, around 38% of Azerbaijan's roughly 8,000,000 population spoke Russian fluently.[216] An independent telephone survey in Iran in 2009 reported that 20% of respondents could understand Azerbaijani, the most spoken minority language in Iran, and all respondents could understand Persian.[169]

The majority of Azerbaijanis are Twelver Shi'a Muslims. Religious minorities include Sunni Muslims (mainly Shafi'i just like other Muslims in the surrounding North Caucasus),[217][218] and Baháʼís. An unknown number of Azerbaijanis in the Republic of Azerbaijan have no religious affiliation. Many describe themselves as Shia Muslims.[164] There is a small number of Naqshbandi Sufis among Muslim Azerbaijanis.[219] Christian Azerbaijanis number around 5,000 people in the Republic of Azerbaijan and consist mostly of recent converts.[220][221] Some Azerbaijanis from rural regions retain pre-Islamic animist or Zoroastrian-influenced[222] beliefs, such as the sanctity of certain sites and the veneration of fire, certain trees and rocks.[223] In Azerbaijan, traditions from other religions are often celebrated in addition to Islamic holidays, including Nowruz and Christmas.

In the group dance the performers come together in a semi-circular or circular formation as, "The leader of these dances often executes special figures as well as signaling and changes in the foot patterns, movements, or direction in which the group is moving, often by gesturing with his or her hand, in which a kerchief is held."[224]

Azerbaijani musical tradition can be traced back to singing bards called Ashiqs, a vocation that survives. Modern Ashiqs play the saz (lute) and sing dastans (historical ballads).[225] Other musical instruments include the tar (another type of lute), balaban (a wind instrument), kamancha (fiddle), and the dhol (drums). Azerbaijani classical music, called mugham, is often an emotional singing performance. Composers Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Gara Garayev and Fikret Amirov created a hybrid style that combines Western classical music with mugham. Other Azerbaijanis, notably Vagif and Aziza Mustafa Zadeh, mixed jazz with mugham. Some Azerbaijani musicians have received international acclaim, including Rashid Behbudov (who could sing in over eight languages), Muslim Magomayev (a pop star from the Soviet era), Googoosh, and more recently Sami Yusuf.[citation needed]

After the 1979 revolution in Iran due to the clerical opposition to music in general, Azerbaijani music took a different course. According to Iranian singer Hossein Alizadeh, "Historically in Iran, music faced strong opposition from the religious establishment, forcing it to go underground."[226]

Some Azerbaijanis have been film-makers, such as Rustam Ibragimbekov, who wrote Burnt by the Sun, winner of the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1994.

Sports have historically been an important part of Azerbaijani life. Horseback competitions were praised in the Book of Dede Korkut and by poets and writers such as Khaqani.[227] Other ancient sports include wrestling, javelin throwing and fencing.

The Soviet legacy has in modern times propelled some Azerbaijanis to become accomplished athletes at the Olympic level.[227] The Azerbaijani government supports the country's athletic legacy and encourages youth participation. Iranian athletes have particularly excelled in weight lifting, gymnastics, shooting, javelin throwing, karate, boxing, and wrestling.[228] Weight lifters, such as Iran's Hossein Reza Zadeh, world super heavyweight-lifting record holder and two-time Olympic champion in 2000 and 2004, or Hadi Saei is a former Iranian[229] Taekwondo athlete who became the most successful Iranian athlete in Olympic history and Nizami Pashayev, who won the European heavyweight title in 2006, have excelled at the international level. Ramil Guliyev, an ethnic Azerbaijani who plays for Turkey, became the first world champion in athletics in the history of Turkey.

Chess is another popular pastime in the Republic of Azerbaijan.[230] The country has produced many notable players, such as Teimour Radjabov, Vugar Gashimov and Shahriyar Mammadyarov, all three highly ranked internationally. Karate is also popular, where Rafael Aghayev achieved particular success, becoming a five-time world champion and eleven-time European champion.

They number 30-35 million and live primarily in Iran (approximately 20 million), the Republic of Azerbaijan (8 million), Turkey (1-2 million), Russia (1 million), and Georgia (300,000).

Ethnic population: 16,700,000 (2019)

CIA and Library of Congress estimates range from 16 percent to 24 percent—that is, 12–18 million people if we employ the latest total figure for Iran's population (77.8 million).

As of 2003, the ethnic classifications are estimated as: [...] Azeri (24 percent)

The latest figures estimate the Azerbaijani population at 24% of Iran's 70 million inhabitants (NVI 2003/2004: 301). This means that there are between 15 and 20 million Azerbaijanis in Iran.

The Azeris have a mixed heritage of Iranic, Caucasian, and Turkic elements(...) Between 16 to 23 million Azeris live in Iran.

Irrespective of the large Azerbaijani population in Iran (about 20 million, compared to 7 million in Azerbaijan)(...)

The official records of the Russian Empire and various published sources from the pre-1917 period also called them "Tatar" or "Caucasian Tatars," "Azerbaijani Tatars" and even "Persian Tatars" in order to differentiate them from the other "Tatars" of the empire and the Persian speakers of Iran.

Ce groupement ne coïncide pas non-plus avec le groupement somatologique : ainsi, les Aderbaïdjani du Caucase et de la Perse, parlant une langue turque, ont le mème type physique que les Persans-Hadjemi, parlant une langue iranienne.

The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter was to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkified' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.

The preoccupation with Iranian culture, literature, and language was widespread among Baku-, Ganja-, and Tiflis-based Shia as well as Sunni intellectuals, and it never ceased throughout the nineteenth century.

Azerbaijani national identity emerged in post-Persian Russian-ruled East Caucasia at the end of the nineteenth century, and was finally forged during the early Soviet period.

The results of the March events were immediate and total for the Musavat. Several hundreds of its members were killed in the fighting; up to 12,000 Muslim civilians perished; thousands of others fled Baku in a mass exodus

On May 27, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (DRA) was declared with Ottoman military support. The rulers of the DRA refused to identify themselves as [Transcaucasian] Tatar, which they rightfully considered to be a Russian colonial definition. (...) Neighboring Iran did not welcome the DRA's adoption of the name of "Azerbaijan" for the country because it could also refer to Iranian Azerbaijan and implied a territorial claim.

(...) whenever it is necessary to choose a name that will encompass all regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan, name Arran can be chosen. But the term Azerbaijan was chosen because when the Azerbaijan republic was created, it was assumed that this and the Persian Azerbaijan will be one entity because the population of both has a big similarity. On this basis, the word Azerbaijan was chosen. Of course right now when the word Azerbaijan is used, it has two meanings as Persian Azerbaijan and as a republic, its confusing and a question arises as to which Azerbaijan is talked about.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)The region to the north of the river Araxes was not called Azerbaijan prior to 1918, unlike the region in northwestern Iran that has been called since so long ago.

The ethnic origins of the Azeris are unclear. The prevailing view is that Azeris are a Turkic people, but there is also a claim that Azeris are Turkicized Caucasians or, as the Iranian official history claims, Turkicized Aryans.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter were to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkised' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)Our ADMIXTURE analysis (Fig 2) revealed that Turkic-speaking populations scattered across Eurasia tend to share most of their genetic ancestry with their current geographic non-Turkic neighbors. This is particularly obvious for Turkic peoples in Anatolia, Iran, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe, but more difficult to determine for northeastern Siberian Turkic speakers, Yakuts and Dolgans, for which non-Turkic reference populations are absent. We also found that a higher proportion of Asian genetic components distinguishes the Turkic speakers all over West Eurasia from their immediate non-Turkic neighbors. These results support the model that expansion of the Turkic language family outside its presumed East Eurasian core area occurred primarily through language replacement, perhaps by the elite dominance scenario, that is, intrusive Turkic nomads imposed their language on indigenous peoples due to advantages in military and/or social organization.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)16% of 77,891,220 [12.5 million]

16% of 70 million [14.5 million]

21.6% of 70,495,782 [15.2 million]