El buceo autónomo es una modalidad de buceo submarino en la que los buceadores utilizan un equipo de respiración que es completamente independiente de un suministro de gas de respiración en la superficie y, por lo tanto, tiene una resistencia limitada pero variable. [1] El nombre scuba es un anacrónimo de " Aparato de respiración subacuático autónomo " y fue acuñado por Christian J. Lambertsen en una patente presentada en 1952. Los buceadores llevan su propia fuente de gas de respiración , generalmente aire comprimido , [2] lo que les proporciona una mayor independencia y movimiento que los buceadores con suministro desde la superficie , y más tiempo bajo el agua que los buceadores libres. [1] Aunque el uso de aire comprimido es común, una mezcla de gases con un mayor contenido de oxígeno, conocida como aire enriquecido o nitrox , se ha vuelto popular debido a la reducción de la ingesta de nitrógeno durante inmersiones largas o repetitivas. Además, se puede utilizar gas de respiración diluido con helio para reducir los efectos de la narcosis por nitrógeno durante inmersiones más profundas.

Los sistemas de buceo con circuito abierto descargan el gas respirable al medio ambiente a medida que se exhala, y consisten en uno o más cilindros de buceo que contienen gas respirable a alta presión que se suministra al buceador a presión ambiental a través de un regulador de buceo . Pueden incluir cilindros adicionales para la extensión del rango, gas de descompresión o gas respirable de emergencia . [3] Los sistemas de buceo con rebreather de circuito cerrado o semicerrado permiten el reciclaje de los gases exhalados. El volumen de gas utilizado es reducido en comparación con el circuito abierto, por lo que se puede utilizar un cilindro o cilindros más pequeños para una duración de inmersión equivalente. Los rebreathers extienden el tiempo que se pasa bajo el agua en comparación con el circuito abierto para el mismo consumo de gas metabólico; producen menos burbujas y menos ruido que el buceo con circuito abierto, lo que los hace atractivos para los buceadores militares encubiertos para evitar ser detectados, los buceadores científicos para evitar molestar a los animales marinos y los buceadores de medios para evitar la interferencia de las burbujas. [1]

El buceo se puede practicar de forma recreativa o profesional en diversas aplicaciones, incluidas las científicas, militares y de seguridad pública, pero la mayoría de los buceos comerciales utilizan equipos de buceo provistos desde la superficie cuando esto es posible. Los buzos que participan en operaciones encubiertas de las fuerzas armadas pueden denominarse hombres rana , buzos de combate o nadadores de ataque. [4]

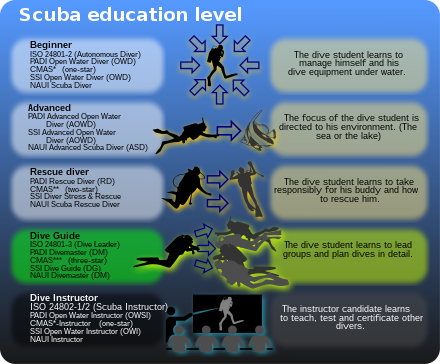

Un buceador se mueve principalmente bajo el agua utilizando aletas unidas a los pies, pero la propulsión externa puede ser proporcionada por un vehículo de propulsión de buzo o un trineo tirado desde la superficie. [5] Otros equipos necesarios para el buceo incluyen una máscara para mejorar la visión bajo el agua, protección contra la exposición por medio de un traje de buceo , pesos de lastre para superar el exceso de flotabilidad, equipo para controlar la flotabilidad y equipo relacionado con las circunstancias específicas y el propósito de la inmersión, que puede incluir un esnórquel para nadar en la superficie, una herramienta de corte para controlar los enredos, luces , una computadora de buceo para monitorear el estado de descompresión y dispositivos de señalización . Los buceadores reciben capacitación en los procedimientos y habilidades apropiados para su nivel de certificación por parte de instructores de buceo afiliados a las organizaciones de certificación de buceadores que emiten estas certificaciones. [6] Estos incluyen procedimientos operativos estándar para usar el equipo y lidiar con los peligros generales del entorno submarino , y procedimientos de emergencia para la autoayuda y asistencia de un buceador equipado de manera similar que experimente problemas. La mayoría de las organizaciones de formación exigen un nivel mínimo de aptitud física y salud , pero un nivel más elevado de aptitud física puede ser adecuado para algunas aplicaciones. [7]

La historia del buceo está estrechamente vinculada con la historia del equipo de buceo . A principios del siglo XX, se habían desarrollado dos arquitecturas básicas para los aparatos de respiración subacuática: los equipos de circuito abierto con suministro de superficie, en los que el gas exhalado por el buceador se ventila directamente al agua, y los aparatos de respiración de circuito cerrado, en los que el dióxido de carbono del buceador se filtra del oxígeno exhalado no utilizado , que luego se recircula y se agrega oxígeno para completar el volumen cuando es necesario. Los equipos de circuito cerrado se adaptaron más fácilmente al buceo en ausencia de recipientes de almacenamiento de gas a alta presión confiables, portátiles y económicos.

A mediados del siglo XX, se disponía de cilindros de gas a alta presión y habían surgido dos sistemas de buceo: el buceo de circuito abierto , en el que el aliento exhalado por el buceador se ventila directamente al agua, y el buceo de circuito cerrado, en el que se elimina el dióxido de carbono del aliento exhalado por el buceador, al que se le añade oxígeno y se recircula. Los rebreathers de oxígeno están severamente limitados en profundidad debido al riesgo de toxicidad por oxígeno , que aumenta con la profundidad, y los sistemas disponibles para rebreathers de gases mixtos eran bastante voluminosos y estaban diseñados para su uso con cascos de buceo. [8] El primer rebreather de buceo comercialmente práctico fue diseñado y construido por el ingeniero de buceo Henry Fleuss en 1878, mientras trabajaba para Siebe Gorman en Londres. [9] Su aparato de respiración autónomo consistía en una máscara de goma conectada a una bolsa de respiración, con un estimado de 50-60% de oxígeno suministrado desde un tanque de cobre y dióxido de carbono lavado al pasarlo a través de un haz de hilo de cuerda empapado en una solución de potasa cáustica, el sistema daba una duración de inmersión de hasta aproximadamente tres horas. Este aparato no tenía forma de medir la composición del gas durante el uso. [9] [10] Durante la década de 1930 y durante toda la Segunda Guerra Mundial , los británicos, italianos y alemanes desarrollaron y utilizaron ampliamente rebreathers de oxígeno para equipar a los primeros hombres rana . Los británicos adaptaron el aparato de escape sumergido Davis y los alemanes adaptaron los rebreathers de escape submarino Dräger , para sus hombres rana durante la guerra. [11] En los EE. UU., el mayor Christian J. Lambertsen inventó un rebreather de oxígeno submarino de natación libre en 1939, que fue aceptado por la Oficina de Servicios Estratégicos . [12] En 1952 patentó una modificación de su aparato, esta vez llamado SCUBA (acrónimo de "self-contained underwater breath apparatus"), [13] [2] [14] [15] que se convirtió en la palabra inglesa genérica para el equipo de respiración autónoma para buceo, y más tarde para la actividad que utiliza el equipo. [16] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los hombres rana militares continuaron utilizando rebreathers ya que no hacen burbujas que delaten la presencia de los buceadores. El alto porcentaje de oxígeno utilizado por estos primeros sistemas de rebreathers limitó la profundidad a la que podían usarse debido al riesgo de convulsiones causadas por la toxicidad aguda del oxígeno . [1] : 1–11

Aunque Auguste Denayrouze y Benoît Rouquayrol habían inventado un sistema regulador de demanda funcional en 1864 , [17] el primer sistema de buceo de circuito abierto desarrollado en 1925 por Yves Le Prieur en Francia era un sistema de flujo libre ajustado manualmente con una baja resistencia, lo que limitaba su utilidad práctica. [18] En 1942, durante la ocupación alemana de Francia , Jacques-Yves Cousteau y Émile Gagnan diseñaron el primer buceo de circuito abierto exitoso y seguro, conocido como Aqua-Lung . Su sistema combinaba un regulador de demanda mejorado con tanques de aire de alta presión. [19] Esto fue patentado en 1945. Para vender su regulador en países de habla inglesa, Cousteau registró la marca Aqua-Lung , que primero fue licenciada a la empresa estadounidense Divers , [20] y en 1948 a Siebe Gorman de Inglaterra. [21] A Siebe Gorman se le permitió vender en países de la Commonwealth, pero tuvo dificultades para satisfacer la demanda y la patente estadounidense impidió que otros fabricaran el producto. La patente fue eludida por Ted Eldred de Melbourne , Australia, quien desarrolló el sistema de buceo de circuito abierto de una sola manguera, que separa la primera etapa y la válvula de demanda del regulador de presión mediante una manguera de baja presión, coloca la válvula de demanda en la boca del buceador y libera el gas exhalado a través de la carcasa de la válvula de demanda. Eldred vendió el primer buceo de una sola manguera Porpoise Modelo CA a principios de 1952. [22]

Los primeros equipos de buceo solían estar provistos de un arnés sencillo con correas para los hombros y un cinturón. Las hebillas del cinturón solían ser de liberación rápida, y las correas para los hombros a veces tenían hebillas ajustables o de liberación rápida. Muchos arneses no tenían placa posterior y los cilindros descansaban directamente contra la espalda del buceador. [23] Los primeros buceadores buceaban sin ayuda de flotabilidad. [nota 1] En caso de emergencia, tenían que deshacerse de sus lastre. En la década de 1960, se comercializaron los chalecos salvavidas de flotabilidad ajustable (ABLJ), que se pueden usar para compensar la pérdida de flotabilidad en profundidad debido a la compresión del traje de neopreno y como un chaleco salvavidas que sostendrá a un buceador inconsciente boca arriba en la superficie, y que se puede inflar rápidamente. Las primeras versiones se inflaban a partir de un pequeño cilindro de dióxido de carbono desechable, más tarde con un pequeño cilindro de aire acoplado directamente. Una alimentación de baja presión desde la primera etapa del regulador a una unidad de válvula de inflado/desinflado, una válvula de inflado oral y una válvula de descarga permite controlar el volumen del ABLJ como ayuda a la flotabilidad. En 1971, ScubaPro introdujo el chaleco estabilizador . Esta clase de ayuda a la flotabilidad se conoce como dispositivo de control de la flotabilidad o compensador de flotabilidad. [24] [25]

Una placa posterior y un ala es una configuración alternativa de un arnés de buceo con una vejiga de compensación de flotabilidad conocida como "ala" montada detrás del buceador, intercalada entre la placa posterior y el cilindro o cilindros. A diferencia de los chalecos estabilizadores, la placa posterior y el ala son un sistema modular, ya que consta de componentes separables. Esta disposición se hizo popular entre los buceadores de cuevas que realizaban inmersiones largas o profundas, que necesitaban llevar varios cilindros adicionales, ya que despeja el frente y los lados del buceador para colocar otro equipo en la región donde es fácilmente accesible. Este equipo adicional generalmente está suspendido del arnés o se lleva en los bolsillos del traje de exposición. [5] [26] El montaje lateral es una configuración de equipo de buceo que tiene equipos básicos de buceo , cada uno compuesto por un solo cilindro con un regulador y un manómetro dedicados, montados junto al buceador, sujetados al arnés debajo de los hombros y a lo largo de las caderas, en lugar de en la espalda del buceador. Se originó como una configuración para el buceo avanzado en cuevas , ya que facilita la penetración en secciones estrechas de cuevas ya que los equipos se pueden quitar y volver a montar fácilmente cuando sea necesario. La configuración permite un fácil acceso a las válvulas de los cilindros y proporciona una redundancia de gas fácil y confiable. Estos beneficios para operar en espacios confinados también fueron reconocidos por los buceadores que hicieron penetraciones en naufragios . El buceo con montaje lateral ha ganado popularidad dentro de la comunidad de buceo técnico para el buceo con descompresión general , [27] y se ha convertido en una especialidad popular para el buceo recreativo. [28] [29] [30]

En la década de 1950, la Marina de los Estados Unidos (USN) documentó procedimientos de gas de oxígeno enriquecido para uso militar de lo que hoy se llama nitrox, [1] y en 1970, Morgan Wells de la NOAA comenzó a instituir procedimientos de buceo para aire enriquecido con oxígeno. En 1979, la NOAA publicó procedimientos para el uso científico de nitrox en el Manual de buceo de la NOAA. [3] [31] En 1985, la IAND (Asociación Internacional de Buceadores con Nitrox) comenzó a enseñar el uso de nitrox para el buceo recreativo. Esto fue considerado peligroso por algunos y se encontró con un gran escepticismo por parte de la comunidad de buceo. [32] Sin embargo, en 1992 NAUI se convirtió en la primera agencia importante de entrenamiento de buceadores recreativos existente en aprobar nitrox, [33] y finalmente, en 1996, la Asociación Profesional de Instructores de Buceo (PADI) anunció el apoyo educativo total para nitrox. [34] El uso de una única mezcla de nitrox se ha convertido en parte del buceo recreativo, y las mezclas de gases múltiples son comunes en el buceo técnico para reducir el tiempo total de descompresión. [35]

El buceo técnico es el buceo recreativo que excede los límites generalmente aceptados para el buceo recreativo y puede exponer al buceador a peligros que van más allá de los que normalmente se asocian con el buceo recreativo, y a mayores riesgos de lesiones graves o muerte. Estos riesgos pueden reducirse con las habilidades, los conocimientos y la experiencia adecuados, y utilizando el equipo y los procedimientos adecuados. El concepto y el término son ambos de aparición relativamente reciente, aunque los buceadores ya habían estado participando en lo que ahora se conoce comúnmente como buceo técnico durante décadas. Una definición razonablemente generalizada es que cualquier inmersión en la que en algún punto del perfil planificado no sea físicamente posible o fisiológicamente aceptable hacer un ascenso vertical directo e ininterrumpido al aire de la superficie es una inmersión técnica. [36] El equipo a menudo implica respirar gases distintos del aire o mezclas estándar de nitrox , múltiples fuentes de gas y diferentes configuraciones de equipo. [37] Con el tiempo, algunos equipos y técnicas desarrollados para el buceo técnico han sido más ampliamente aceptados para el buceo recreativo. [36]

La toxicidad del oxígeno limita la profundidad a la que pueden llegar los buceadores bajo el agua cuando respiran mezclas de nitrox. En 1924, la Marina de los EE. UU. comenzó a investigar la posibilidad de usar helio y, después de experimentos con animales, los sujetos humanos que respiraron heliox 20/80 (20 % de oxígeno, 80 % de helio) se descomprimieron con éxito de inmersiones profundas, [38] En 1963, se realizaron inmersiones de saturación utilizando trimix durante el Proyecto Génesis , [39] y en 1979, un equipo de investigación del Laboratorio Hiperbárico del Centro Médico de la Universidad de Duke comenzó a trabajar en la identificación del uso de trimix para prevenir los síntomas del síndrome nervioso de alta presión . [40] Los buceadores de cuevas comenzaron a utilizar trimix para permitir inmersiones más profundas y se utilizó ampliamente en el Proyecto Wakulla Springs de 1987 y se extendió a la comunidad de buceo en naufragios del noreste de Estados Unidos. [41]

Los desafíos de las inmersiones más profundas y las penetraciones más largas y las grandes cantidades de gas respirable necesarias para estos perfiles de inmersión y la fácil disponibilidad de células de detección de oxígeno a partir de finales de la década de 1980 llevaron a un resurgimiento del interés en el buceo con rebreather. Al medir con precisión la presión parcial de oxígeno, se hizo posible mantener y monitorear con precisión una mezcla de gases respirables en el circuito a cualquier profundidad. [36] A mediados de la década de 1990, los rebreathers de circuito semicerrado comenzaron a estar disponibles para el mercado del buceo recreativo, seguidos por los rebreathers de circuito cerrado alrededor del cambio de milenio. [42] Los rebreathers se fabrican actualmente para los mercados de buceo militar, técnico y recreativo, [36] pero siguen siendo menos populares, menos confiables y más caros que los equipos de circuito abierto.

El equipo de buceo, también conocido como equipo de buceo, es el equipo utilizado por un buceador con el propósito de bucear, e incluye el aparato de respiración, el traje de buceo , los sistemas de control de flotabilidad y de ponderación, aletas para movilidad, máscara para mejorar la visión submarina y una variedad de equipos de seguridad y otros accesorios.

El equipo que define al buceador es el equipo de buceo epónimo , el aparato autónomo de respiración subacuática que permite al buceador respirar mientras bucea y que es transportado por el buceador. También se lo conoce comúnmente como equipo de buceo.

A medida que se desciende, además de la presión atmosférica normal en la superficie, el agua ejerce una presión hidrostática creciente de aproximadamente 1 bar (14,7 libras por pulgada cuadrada) por cada 10 m (33 pies) de profundidad. La presión del aire inhalado debe equilibrar la presión ambiental o circundante para permitir una inflación controlada de los pulmones. Se vuelve prácticamente imposible respirar aire a presión atmosférica normal a través de un tubo a menos de 3 pies (0,9 m) bajo el agua. [2]

La mayoría de las inmersiones recreativas se realizan con una máscara de media cara que cubre los ojos y la nariz del buceador, y una boquilla para suministrar el gas respirable desde la válvula de demanda o el rebreather. Inhalar desde una boquilla se convierte en algo natural muy rápidamente. La otra disposición común es una máscara de cara completa que cubre los ojos, la nariz y la boca, y a menudo permite al buceador respirar por la nariz. Los buceadores profesionales son más propensos a utilizar máscaras de cara completa, que protegen las vías respiratorias del buceador si este pierde el conocimiento. [43]

El equipo de buceo de circuito abierto no permite utilizar el gas respirable más de una vez para la respiración. [1] El gas inhalado del equipo de buceo se exhala al medio ambiente o, ocasionalmente, a otro elemento del equipo para un propósito especial, generalmente para aumentar la flotabilidad de un dispositivo de elevación como un compensador de flotabilidad, una boya de señalización de superficie inflable o una pequeña bolsa de elevación. El gas respirable generalmente se proporciona desde un cilindro de buceo de alta presión a través de un regulador de buceo. Al proporcionar siempre el gas respirable adecuado a presión ambiental, los reguladores de válvula de demanda garantizan que el buceador pueda inhalar y exhalar de forma natural y sin un esfuerzo excesivo, independientemente de la profundidad, cuando sea necesario. [23]

El equipo de buceo más comúnmente utilizado utiliza un regulador de demanda de dos etapas de circuito abierto de "manguera única", conectado a un solo cilindro de gas de alta presión montado en la parte posterior, con la primera etapa conectada a la válvula del cilindro y la segunda etapa a la boquilla. [1] Esta disposición difiere del diseño original de "manguera doble" de Émile Gagnan y Jacques Cousteau de 1942, conocido como Aqua-lung, en el que la presión del cilindro se reducía a la presión ambiente en una o dos etapas que estaban todas en la carcasa montada en la válvula del cilindro o colector. [23] El sistema de "manguera única" tiene ventajas significativas sobre el sistema original para la mayoría de las aplicaciones. [44]

En el diseño de dos etapas de "manguera única", el regulador de la primera etapa reduce la presión del cilindro de hasta aproximadamente 300 bares (4400 psi) a una presión intermedia (IP) de aproximadamente 8 a 10 bares (120 a 150 psi) por encima de la presión ambiental. El regulador de válvula de demanda de la segunda etapa , alimentado por una manguera de baja presión desde la primera etapa, suministra el gas respirable a presión ambiental a la boca del buceador. Los gases exhalados se expulsan directamente al medio ambiente como desechos a través de una válvula antirretorno en la carcasa de la segunda etapa. La primera etapa generalmente tiene al menos un puerto de salida que suministra gas a presión de tanque lleno que está conectado al manómetro sumergible o al ordenador de buceo del buceador, para mostrar cuánto gas respirable queda en el cilindro. [44]

Menos comunes son los rebreathers de circuito cerrado (CCR) y semicerrados (SCR) que, a diferencia de los equipos de circuito abierto que expulsan todos los gases exhalados, procesan todo o parte de cada aliento exhalado para su reutilización eliminando el dióxido de carbono y reemplazando el oxígeno utilizado por el buceador. [45] Los rebreathers liberan pocas o ninguna burbuja de gas en el agua y utilizan mucho menos volumen de gas almacenado, para una profundidad y tiempo equivalentes porque se recupera el oxígeno exhalado; esto tiene ventajas para la investigación, el ejército, [1] la fotografía y otras aplicaciones. Los rebreathers son más complejos y más caros que el buceo de circuito abierto, y se requiere una capacitación especial y un mantenimiento correcto para su uso seguro, debido a la mayor variedad de modos de falla potenciales. [45]

En un rebreather de circuito cerrado, la presión parcial de oxígeno en el rebreather está controlada, por lo que se puede mantener en un máximo continuo seguro, lo que reduce la presión parcial de gas inerte (nitrógeno y/o helio) en el circuito de respiración. Minimizar la carga de gas inerte de los tejidos del buceador para un perfil de inmersión determinado reduce la obligación de descompresión. Esto requiere un control continuo de las presiones parciales reales con el tiempo y, para lograr la máxima eficacia, requiere un procesamiento informático en tiempo real por parte del ordenador de descompresión del buceador. La descompresión se puede reducir mucho en comparación con las mezclas de gases de proporción fija que se utilizan en otros sistemas de buceo y, como resultado, los buceadores pueden permanecer sumergidos durante más tiempo o requerir menos tiempo para descomprimirse. Un rebreather de circuito semicerrado inyecta un flujo de masa constante de una mezcla fija de gases respirables en el circuito de respiración, o reemplaza un porcentaje específico del volumen respirado, por lo que la presión parcial de oxígeno en cualquier momento durante la inmersión depende del consumo de oxígeno del buceador y/o de su frecuencia respiratoria. La planificación de los requisitos de descompresión requiere un enfoque más conservador para un SCR que para un CCR, pero los ordenadores de descompresión con una entrada de presión parcial de oxígeno en tiempo real pueden optimizar la descompresión para estos sistemas. Debido a que los rebreathers producen muy pocas burbujas, no perturban la vida marina ni hacen notar la presencia de un buzo en la superficie; esto es útil para la fotografía submarina y para el trabajo encubierto. [36]

Para algunas inmersiones, se pueden utilizar mezclas de gases distintas del aire atmosférico normal (21 % de oxígeno, 78 % de nitrógeno , 1 % de gases traza), [1] [2] siempre que el buceador sea competente en su uso. La mezcla más utilizada es el nitrox, también conocido como aire enriquecido con nitrox (EAN o EANx), que es aire con oxígeno adicional, a menudo con un 32 % o 36 % de oxígeno, y por lo tanto menos nitrógeno, lo que reduce el riesgo de enfermedad por descompresión o permite una exposición más prolongada a la misma presión con el mismo riesgo. El nitrógeno reducido también puede permitir no hacer paradas o tiempos de parada de descompresión más cortos o un intervalo de superficie más corto entre inmersiones. [46] [2] : 304

La mayor presión parcial de oxígeno debido al mayor contenido de oxígeno del nitrox aumenta el riesgo de toxicidad por oxígeno, que se vuelve inaceptable por debajo de la profundidad máxima de operación de la mezcla. Para desplazar el nitrógeno sin aumentar la concentración de oxígeno, se pueden utilizar otros gases diluyentes, generalmente helio , cuando la mezcla de tres gases resultante se denomina trimix , y cuando el nitrógeno está completamente sustituido por helio, heliox . [3]

Para las inmersiones que requieren paradas de descompresión prolongadas, los buceadores pueden llevar cilindros que contienen diferentes mezclas de gases para las distintas fases de la inmersión, generalmente denominados gases de viaje, de fondo y de descompresión. Estas diferentes mezclas de gases se pueden utilizar para extender el tiempo de fondo, reducir los efectos narcóticos de los gases inertes y reducir los tiempos de descompresión . El gas de espalda se refiere a cualquier gas que el buceador lleve en la espalda, generalmente gas de fondo. [47]

Para aprovechar la libertad de movimiento que ofrece el equipo de buceo, el buceador debe poder moverse bajo el agua. La movilidad personal se mejora con aletas de natación y, opcionalmente, con vehículos de propulsión para buceadores. Las aletas tienen una gran superficie de pala y utilizan los músculos más potentes de las piernas, por lo que son mucho más eficientes para la propulsión y el empuje de maniobra que los movimientos de brazos y manos, pero requieren habilidad para proporcionar un control preciso. Hay varios tipos de aletas disponibles, algunas de las cuales pueden ser más adecuadas para maniobras, estilos de patada alternativos, velocidad, resistencia, esfuerzo reducido o robustez. [3] La flotabilidad neutra permitirá que el esfuerzo de propulsión se dirija en la dirección del movimiento previsto y reducirá la resistencia inducida. La aerodinámica del equipo de buceo también reducirá la resistencia y mejorará la movilidad. El ajuste equilibrado que permite al buceador alinearse en cualquier dirección deseada también mejora la aerodinámica al presentar el área de sección más pequeña a la dirección del movimiento y permitir que el empuje de propulsión se utilice de manera más eficiente. [48]

En ocasiones, un buceador puede ser remolcado utilizando un "trineo", un dispositivo sin motor que se remolca detrás de una embarcación de superficie que conserva la energía del buceador y permite cubrir una mayor distancia con un consumo de aire y un tiempo de fondo determinados. La profundidad suele ser controlada por el buceador utilizando planos de inmersión o inclinando todo el trineo. [49] Algunos trineos están carenados para reducir la resistencia al avance del buceador. [50]

Para bucear de forma segura, los buceadores deben controlar su velocidad de ascenso y descenso en el agua [2] y ser capaces de mantener una profundidad constante en el agua intermedia. [51] Ignorando otras fuerzas como las corrientes de agua y la natación, la flotabilidad general del buceador determina si asciende o desciende. Se pueden utilizar equipos como sistemas de pesas para buceo , trajes de buceo (se utilizan trajes húmedos, secos o semisecos según la temperatura del agua) y compensadores de flotabilidad (BC) o dispositivos de control de flotabilidad (BCD) para ajustar la flotabilidad general. [1] Cuando los buceadores quieren permanecer a una profundidad constante, intentan lograr una flotabilidad neutra. Esto minimiza el esfuerzo de nadar para mantener la profundidad y, por lo tanto, reduce el consumo de gas. [51]

La fuerza de flotabilidad sobre el buceador es el peso del volumen del líquido que él y su equipo desplazan menos el peso del buceador y su equipo; si el resultado es positivo , esa fuerza es hacia arriba. La flotabilidad de cualquier objeto sumergido en agua también se ve afectada por la densidad del agua. La densidad del agua dulce es aproximadamente un 3% menor que la del agua del océano. [52] Por lo tanto, los buceadores que son neutrales en un destino de buceo (por ejemplo, un lago de agua dulce) previsiblemente serán positiva o negativamente flotantes cuando utilicen el mismo equipo en destinos con diferentes densidades de agua (por ejemplo, un arrecife de coral tropical ). [51] La eliminación ("zambullida" o "desprendimiento") de los sistemas de peso del buceador se puede utilizar para reducir el peso del buceador y provocar un ascenso boyante en caso de emergencia. [51]

Los trajes de buceo fabricados con materiales compresibles disminuyen de volumen a medida que el buceador desciende y se expanden nuevamente a medida que asciende, lo que provoca cambios en la flotabilidad. Bucear en diferentes entornos también requiere ajustes en la cantidad de peso transportado para lograr una flotabilidad neutra. El buceador puede inyectar aire en los trajes secos para contrarrestar el efecto de compresión y apretar . Los compensadores de flotabilidad permiten realizar ajustes fáciles y precisos en el volumen general del buceador y, por lo tanto, en su flotabilidad. [51]

La flotabilidad neutra de un buceador es un estado inestable. Se modifica con pequeñas diferencias en la presión ambiental causadas por un cambio en la profundidad, y el cambio tiene un efecto de retroalimentación positiva. Un pequeño descenso aumentará la presión, lo que comprimirá los espacios llenos de gas y reducirá el volumen total del buceador y el equipo. Esto reducirá aún más la flotabilidad y, a menos que se contrarreste, dará como resultado un hundimiento más rápido. El efecto equivalente se aplica a un pequeño ascenso, que provocará un aumento de la flotabilidad y dará como resultado un ascenso acelerado a menos que se contrarreste. El buceador debe ajustar continuamente la flotabilidad o la profundidad para permanecer neutral. Se puede lograr un control preciso de la flotabilidad controlando el volumen pulmonar promedio en el buceo con circuito abierto, pero esta característica no está disponible para el buceador con rebreather de circuito cerrado, ya que el gas exhalado permanece en el circuito de respiración. Esta es una habilidad que mejora con la práctica hasta que se convierte en una segunda naturaleza. [51]

Los cambios de flotabilidad con la variación de profundidad son proporcionales a la parte compresible del volumen del buceador y del equipo, y al cambio proporcional de presión, que es mayor por unidad de profundidad cerca de la superficie. Minimizar el volumen de gas requerido en el compensador de flotabilidad minimizará las fluctuaciones de flotabilidad con los cambios de profundidad. Esto se puede lograr mediante una selección precisa del peso del lastre, que debe ser el mínimo para permitir la flotabilidad neutra con suministros de gas agotados al final de la inmersión, a menos que exista un requisito operativo para una mayor flotabilidad negativa durante la inmersión. [35] La flotabilidad y el equilibrio pueden afectar significativamente la resistencia de un buceador. El efecto de nadar con un ángulo de cabeza hacia arriba de aproximadamente 15°, como es bastante común en buceadores mal equilibrados, puede ser un aumento de la resistencia del orden del 50%. [48]

La capacidad de ascender a un ritmo controlado y permanecer a una profundidad constante es importante para una descompresión correcta. Los buceadores recreativos que no tienen obligaciones de descompresión pueden salirse con la suya con un control imperfecto de la flotabilidad, pero cuando se requieren paradas de descompresión prolongadas a profundidades específicas, el riesgo de enfermedad por descompresión aumenta por las variaciones de profundidad durante una parada. Las paradas de descompresión se realizan típicamente cuando el gas respirable en los cilindros se ha agotado en gran medida, y la reducción de peso de los cilindros aumenta la flotabilidad del buceador. Se debe llevar suficiente peso para permitir que el buceador se descomprima al final de la inmersión con los cilindros casi vacíos. [35]

El control de la profundidad durante el ascenso se facilita ascendiendo sobre una cuerda con una boya en la parte superior. El buceador puede permanecer marginalmente negativo y mantener fácilmente la profundidad sujetándose de la cuerda. Para este fin se utilizan comúnmente una cuerda de salvamento o una boya de descompresión. Un control de la profundidad preciso y fiable es especialmente valioso cuando el buceador tiene una gran obligación de descompresión, ya que permite la descompresión teóricamente más eficiente con el menor riesgo razonablemente practicable. Lo ideal es que el buceador practique un control preciso de la flotabilidad cuando el riesgo de enfermedad por descompresión debido a que la variación de la profundidad viola el techo de descompresión es bajo.

El agua tiene un índice de refracción más alto que el aire, similar al de la córnea del ojo. La luz que entra en la córnea desde el agua casi no se refracta, dejando solo el cristalino del ojo para enfocar la luz. Esto conduce a una hipermetropía muy severa . Por lo tanto, las personas con miopía severa pueden ver mejor bajo el agua sin máscara que las personas con visión normal. [53] Las máscaras y cascos de buceo resuelven este problema al proporcionar un espacio de aire frente a los ojos del buceador. [1] El error de refracción creado por el agua se corrige en gran parte a medida que la luz viaja del agua al aire a través de una lente plana, excepto que los objetos parecen aproximadamente un 34% más grandes y un 25% más cercanos en el agua de lo que realmente están. La placa frontal de la máscara está sostenida por un marco y una falda, que son opacos o translúcidos, por lo tanto, el campo de visión total se reduce significativamente y la coordinación ojo-mano debe ajustarse. [53]

Los buceadores que necesitan lentes correctoras para ver con claridad fuera del agua normalmente necesitarían la misma prescripción si usaran una máscara. Hay lentes correctoras genéricas disponibles en el mercado para algunas máscaras de dos ventanas, y se pueden colocar lentes personalizadas en máscaras que tienen una sola ventana frontal o dos ventanas. [54]

A medida que un buceador desciende, debe exhalar periódicamente por la nariz para igualar la presión interna de la máscara con la del agua circundante. Las gafas de natación no son adecuadas para bucear porque solo cubren los ojos y, por lo tanto, no permiten la compensación. Si no se iguala la presión dentro de la máscara, puede producirse una forma de barotrauma conocido como compresión de la máscara. [1] [3]

Las máscaras tienden a empañarse cuando el aire húmedo y cálido exhalado se condensa en el interior frío de la placa frontal. Para evitar que se empañen, muchos buceadores escupen en la máscara seca antes de usarla, esparcen la saliva por el interior del cristal y lo enjuagan con un poco de agua. El residuo de saliva permite que la condensación humedezca el cristal y forme una película húmeda continua, en lugar de pequeñas gotas. Hay varios productos comerciales que se pueden utilizar como alternativa a la saliva, algunos de los cuales son más efectivos y duran más, pero existe el riesgo de que el agente antivaho entre en contacto con los ojos. [55]

El agua atenúa la luz por absorción selectiva. [53] [56] El agua pura absorbe preferentemente la luz roja y, en menor medida, la amarilla y la verde, por lo que el color que menos se absorbe es la luz azul. [57] Los materiales disueltos también pueden absorber selectivamente el color además de la absorción por el agua misma. En otras palabras, a medida que un buceador se sumerge más profundamente, el agua absorbe más color y, en agua limpia, el color se vuelve azul con la profundidad. La visión del color también se ve afectada por la turbidez del agua, que tiende a reducir el contraste. La luz artificial es útil para proporcionar luz en la oscuridad, para restaurar el contraste a corta distancia y para restaurar el color natural perdido por la absorción. [53]

Las luces de buceo también pueden atraer peces y una variedad de otras criaturas marinas.

La protección contra la pérdida de calor en agua fría suele proporcionarse mediante trajes de neopreno o trajes secos. Estos también proporcionan protección contra las quemaduras solares, la abrasión y las picaduras de algunos organismos marinos. Cuando el aislamiento térmico no es importante, los trajes de lycra o las pieles de buceo pueden ser suficientes. [58]

Un traje de neopreno es una prenda, generalmente hecha de neopreno espumado, que proporciona aislamiento térmico, resistencia a la abrasión y flotabilidad. Las propiedades de aislamiento dependen de las burbujas de gas encerradas dentro del material, que reducen su capacidad para conducir el calor. Las burbujas también le dan al traje de neopreno una baja densidad, lo que proporciona flotabilidad en el agua. Los trajes varían desde un traje delgado (2 mm o menos) "corto", que cubre solo el torso, hasta un traje semiseco de 8 mm, generalmente complementado con botas de neopreno, guantes y capucha. Un buen ajuste y pocas cremalleras ayudan al traje a permanecer impermeable y reducen el enrojecimiento, la sustitución del agua atrapada entre el traje y el cuerpo por agua fría del exterior. Los sellos mejorados en el cuello, las muñecas y los tobillos y los deflectores debajo de la cremallera de entrada producen un traje conocido como "semiseco". [59] [58]

Un traje seco también proporciona aislamiento térmico al usuario mientras está sumergido en agua, [60] [61] [62] [63] y normalmente protege todo el cuerpo excepto la cabeza, las manos y, a veces, los pies. En algunas configuraciones, estos también están cubiertos. Los trajes secos se utilizan generalmente cuando la temperatura del agua es inferior a 15 °C (60 °F) o para inmersiones prolongadas en agua por encima de 15 °C (60 °F), donde un usuario de traje de neopreno pasaría frío, y con un casco integrado, botas y guantes para protección personal cuando se bucea en agua contaminada. [64] Los trajes secos están diseñados para evitar que entre agua. Esto generalmente permite un mejor aislamiento, lo que los hace más adecuados para su uso en agua fría. Pueden ser incómodamente calientes en aire cálido o caliente, y suelen ser más caros y más complejos de colocar. Para los buceadores, añaden cierto grado de complejidad, ya que el traje debe inflarse y desinflarse con los cambios de profundidad para evitar "apretones" en el descenso o ascensos rápidos descontrolados debido al exceso de flotabilidad. [64] Los buceadores con traje seco también pueden utilizar el gas argón para inflar sus trajes a través de una manguera de inflado de baja presión. Esto se debe a que el gas es inerte y tiene una conductividad térmica baja. [65]

A menos que se conozca la profundidad máxima del agua y esta sea bastante baja, un buceador debe controlar la profundidad y la duración de una inmersión para evitar la enfermedad por descompresión. Tradicionalmente, esto se hacía utilizando un medidor de profundidad y un reloj de buceo, pero ahora se utilizan de forma generalizada los ordenadores de buceo electrónicos , ya que están programados para realizar modelos en tiempo real de los requisitos de descompresión para la inmersión y permiten automáticamente un intervalo en la superficie. Muchos pueden configurarse para la mezcla de gases que se utilizará en la inmersión y algunos pueden aceptar cambios en la mezcla de gases durante la inmersión. La mayoría de los ordenadores de buceo proporcionan un modelo de descompresión bastante conservador, y el nivel de conservadurismo puede ser seleccionado por el usuario dentro de ciertos límites. La mayoría de los ordenadores de descompresión también pueden configurarse para compensar la altitud hasta cierto punto [35] y algunos tendrán en cuenta automáticamente la altitud midiendo la presión atmosférica real y utilizándola en los cálculos [66] .

Si el sitio de buceo y el plan de buceo requieren que el buceador navegue, se puede llevar una brújula y, cuando es fundamental volver a trazar una ruta, como en el caso de penetraciones en cuevas o pecios, se coloca una línea guía desde un carrete de buceo. En condiciones menos críticas, muchos buceadores simplemente navegan por puntos de referencia y de memoria, un procedimiento también conocido como pilotaje o navegación natural. Un buceador debe estar siempre al tanto del suministro de gas respirable restante y de la duración del tiempo de buceo que este le permitirá de manera segura, teniendo en cuenta el tiempo necesario para salir a la superficie de manera segura y un margen para contingencias previsibles. Esto se suele controlar mediante el uso de un manómetro sumergible en cada cilindro. [67]

Todo buceador que vaya a bucear por debajo de una profundidad desde la que sea competente para realizar un ascenso de emergencia seguro a nado debe asegurarse de tener un suministro alternativo de gas respirable disponible en todo momento en caso de que falle el equipo con el que esté respirando en ese momento. Se utilizan varios sistemas comunes según el perfil de inmersión planificado. El más común, pero el menos confiable, es confiar en el compañero de buceo para compartir el gas utilizando una segunda etapa secundaria, comúnmente llamada regulador octopus conectado a la primera etapa primaria. Este sistema depende completamente de que el compañero de buceo esté inmediatamente disponible para proporcionar gas de emergencia. Los sistemas más confiables requieren que el buceador lleve un suministro alternativo de gas suficiente para permitirle llegar de manera segura a un lugar donde haya más gas respirable disponible. Para los buceadores recreativos en aguas abiertas, esta es la superficie. Un cilindro de rescate proporciona gas respirable de emergencia suficiente para un ascenso de emergencia seguro. Para los buceadores técnicos en una inmersión de penetración, puede ser un cilindro de etapa ubicado en un punto en la ruta de salida. Un suministro de gas de emergencia debe ser lo suficientemente seguro para respirar en cualquier punto del perfil de inmersión planificado en el que pueda ser necesario. Este equipo puede ser un cilindro de emergencia , un rebreather de emergencia , un cilindro de gas de viaje o un cilindro de gas de descompresión . Cuando se utiliza un gas de viaje o un gas de descompresión, el gas de respaldo (suministro de gas principal) puede ser el suministro de gas de emergencia designado.

Cutting tools such as knives, line cutters or shears are often carried by divers to cut loose from entanglement in nets or lines. A surface marker buoy (SMB) on a line held by the diver indicates the position of the diver to the surface personnel. This may be an inflatable marker deployed by the diver at the end of the dive, or a sealed float, towed for the whole dive. A surface marker also allows easy and accurate control of ascent rate and stop depth for safer decompression.[68]

Various surface detection aids may be carried to help surface personnel spot the diver after ascent. In addition to the surface marker buoy, divers may carry mirrors, lights, strobes, whistles, flares or emergency locator beacons.[68]

Divers may carry underwater photographic or video equipment, or tools for a specific application in addition to diving equipment. Professional divers will routinely carry and use tools to facilitate their underwater work, while most recreational divers will not engage in underwater work.

Breathing from scuba is mostly a straightforward matter. Under most circumstances, it differs very little from normal surface breathing. In the case of a full-face mask, the diver may usually breathe through the nose or mouth as preferred, and in the case of a mouth held demand valve, the diver will have to hold the mouthpiece between the teeth and maintain a seal around it with the lips. Over a long dive this can induce jaw fatigue, and for some people, a gag reflex. Various styles of mouthpiece are available off the shelf or as customised items, and one of them may work better if either of these problems occur.

The frequently quoted warning against holding one's breath on scuba is a gross oversimplification of the actual hazard. The purpose of the admonition is to ensure that inexperienced divers do not accidentally hold their breath while surfacing, as the expansion of gas in the lungs could over-expand the lung air spaces and rupture the alveoli and their capillaries, allowing lung gases to get into the pulmonary return circulation, the pleura, or the interstitial areas near the injury, where it could cause dangerous medical conditions. Holding the breath at constant depth for short periods with a normal lung volume is generally harmless, providing there is sufficient ventilation on average to prevent carbon dioxide buildup, and is done as a standard practice by underwater photographers to avoid startling their subjects. Holding the breath during descent can eventually cause lung squeeze, and may allow the diver to miss warning signs of a gas supply malfunction until it is too late to remedy.

Skilled open-circuit divers make small adjustments to buoyancy by adjusting their average lung volume during the breathing cycle. This adjustment is generally in the order of a kilogram (corresponding to a litre of gas), and can be maintained for a moderate period, but it is more comfortable to adjust the volume of the buoyancy compensator over the longer term.[72]

The practice of shallow breathing or skip breathing in an attempt to conserve breathing gas should be avoided as it is inefficient and tends to cause a carbon dioxide buildup, which can result in headaches and a reduced capacity to recover from a breathing gas supply emergency. The breathing apparatus will generally increase dead space by a small but significant amount, and cracking pressure and flow resistance in the demand valve will cause a net work of breathing increase, which will reduce the diver's capacity for other work. Work of breathing and the effect of dead space can be minimised by breathing relatively deeply and slowly. These effects increase with depth, as density and friction increase in proportion to the increase in pressure, with the limiting case where all the diver's available energy may be expended on simply breathing, with none left for other purposes. This would be followed by a buildup in carbon dioxide, causing an urgent feeling of a need to breathe, and if this cycle is not broken, panic and drowning are likely to follow. The use of a low-density inert gas, typically helium, in the breathing mixture can reduce this problem, as well as diluting the narcotic effects of the other gases.[73][74]

Breathing from a rebreather is much the same, except that the work of breathing is affected mainly by flow resistance in the breathing loop. This is partly due to the carbon dioxide absorbent in the scrubber, and is related to the distance the gas passes through the absorbent material, and the size of the gaps between the grains, as well as the gas composition and ambient pressure. Water in the loop can greatly increase the resistance to gas flow through the scrubber. There is even less point in shallow or skip breathing on a rebreather as this does not even conserve gas, and the effect on buoyancy is negligible when the sum of loop volume and lung volume remains constant.[74][75]

A breathing pattern of slow, deep breaths which limits gas velocity and thereby turbulent flow in the air passages will minimise the work of breathing for a given gas mixture composition and density, and respiratory minute volume.[74]

The underwater environment is unfamiliar and hazardous, and to ensure diver safety, simple, yet necessary procedures must be followed. A certain minimum level of attention to detail and acceptance of responsibility for one's own safety and survival are required. Most of the procedures are simple and straightforward, and become second nature to the experienced diver, but must be learned, and take some practice to become automatic and faultless, just like the ability to walk or talk. Most of the safety procedures are intended to reduce the risk of drowning, and many of the rest are to reduce the risk of barotrauma and decompression sickness. In some applications getting lost is a serious hazard, and specific procedures to minimise the risk are followed.[6]

The purpose of dive planning is to ensure that divers do not exceed their comfort zone or skill level, or the safe capacity of their equipment, and includes gas planning to ensure that the amount of breathing gas to be carried is sufficient to allow for any reasonably foreseeable contingencies. Before starting a dive both the diver and their buddy[note 2] do equipment checks to ensure everything is in good working order and available. Recreational divers are responsible for planning their own dives, unless in training when the instructor is responsible.[76][77] Divemasters may provide useful information and suggestions to assist the divers, but are generally not responsible for the details unless specifically employed to do so. In professional diving teams, all team members are usually expected to contribute to planning and to check the equipment they will use, but the overall responsibility for the safety of the team lies with the supervisor as the appointed on-site representative of the employer.[43][78][79][80]

Some procedures are common to almost all scuba dives, or are used to manage very common contingencies. These are learned at entry level and may be highly standardised to allow efficient cooperation between divers trained at different schools.[81][82][6]

Inert gas components of the diver's breathing gas accumulate in the tissues during exposure to elevated pressure during a dive, and must be eliminated during the ascent to avoid the formation of symptomatic bubbles in tissues where the concentration is too high for the gas to remain in solution. This process is called decompression, and occurs on all scuba dives.[84] Decompression sickness is also known as the bends and can also include symptoms such as itching, rash, joint pain or nausea.[85] Most recreational and professional scuba divers avoid obligatory decompression stops by following a dive profile which only requires a limited rate of ascent for decompression, but will commonly also do an optional short, shallow, decompression stop known as a safety stop to further reduce risk before surfacing. In some cases, particularly in technical diving, more complex decompression procedures are necessary. Decompression may follow a pre-planned series of ascents interrupted by stops at specific depths, or may be monitored by a personal decompression computer.[86]

These include debriefing where appropriate, and equipment maintenance, to ensure that the equipment is kept in good condition for later use.[83][6] It is also considered a best practice to log each dive upon completion. This is done for several reasons: If a diver is planning on doing multiple dives in a day, they need to know what the depth and duration of previous dives were in order to calculate residual inert gas levels in preparation for the next dive. It is helpful to note what equipment was used for each dive and what the conditions were like for reference when planning another similar dive. For example, the thickness and type of wetsuit used during a dive, and if it was in fresh or salt water, will influence the amount of weight needed. Knowing this information and taking note of whether the weight used was too heavy or too light can help when planning another dive in similar conditions. In order to achieve a level of certification the diver may be required to present evidence of a specified number of logged and verified dives.[87] Professional divers may be legally required to log specific information for every working dive.[43] When a personal dive computer is used, it will accurately record the details of the dive profile, and this data can usually be downloaded to an electronic logbook, in which the diver can add the other details manually.

Buddy and team diving procedures are intended to ensure that a recreational scuba diver who gets into difficulty underwater is in the presence of a similarly equipped person who will understand the problem and can render assistance. Divers are trained to assist in those emergencies specified in the training standards for their certification, and are required to demonstrate competence in a set of prescribed buddy assistance skills. The fundamentals of buddy and team safety are centred on diver communication, redundancy of gear and breathing gas by sharing with the buddy, and the added situational perspective of another diver.[88] There is general consensus that the presence of a buddy both willing and competent to assist can reduce the risk of certain classes of accidents, but much less agreement on how often this happens in practice.

Solo divers take responsibility for their own safety and compensate for the absence of a buddy with skill, vigilance and appropriate equipment. Like buddy or team divers, properly equipped solo divers rely on the redundancy of critical articles of dive gear which may include at least two independent supplies of breathing gas and ensuring that there is always enough available to safely terminate the dive if any one supply fails. The difference between the two practices is that this redundancy is carried and managed by the solo diver instead of a buddy. Agencies that certify for solo diving require candidates to have a relatively high level of dive experience – usually about 100 dives or more.[89][90]

Since the inception of scuba, there has been an ongoing debate regarding the wisdom of solo diving with strong opinions on both sides of the issue. This debate is complicated by the fact that the line which separates a solo diver from a buddy/team diver is not always clear.[91] For example, should a scuba instructor (who supports the buddy system) be considered a solo diver if their students do not have the knowledge or experience to assist the instructor through an unforeseen scuba emergency? Should the buddy of an underwater photographer consider themselves as effectively diving alone since their buddy (the photographer) is giving most or all of their attention to the subject of the photograph? This debate has motivated some prominent scuba agencies such as Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) to stress that its members only dive in teams and "remain aware of team member location and safety at all times."[92] Other agencies such as Scuba Diving International (SDI) and Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) have taken the position that divers might find themselves alone (by choice or by accident) and have created certification courses such as the "SDI Solo Diver Course" and the "PADI Self-Reliant Diver Course" in order to train divers to handle such possibilities.[93][94]

Other organisations such as the International Diving Safety Standards Commission (IDSSC), do not accept recreational solo diving for unspecified "psychological, social and technical reasons", without providing logical arguments or evidence supporting their stance.[95][96] It is not clear that the IDSSC is formally recognised in the role they have claimed.

The most urgent underwater emergencies usually involve a compromised breathing gas supply. Divers are trained in procedures for donating and receiving breathing gas from each other in an emergency, and may carry an independent alternative air source if they do not choose to rely on a buddy.[83][6][82] Divers may need to make an emergency ascent in the event of a loss of breathing gas which cannot be managed at depth. Controlled emergency ascents are almost always a consequence of loss of breathing gas, while uncontrolled ascents are usually the result of a buoyancy control failure.[97] Other urgent emergencies may involve loss of control of depth and medical emergencies.

Divers may be trained in procedures that have been approved by the training agencies for recovery of an unresponsive diver to the surface, where it might be possible to administer first aid. Not all recreational divers have this training as some agencies do not include it in entry-level training. Professional divers may be required by legislation or code of practice to have a standby diver at any diving operation, who is both competent and available to attempt rescue of a distressed diver.[83][82]

Two basic types of entrapment are significant hazards for scuba divers: Inability to navigate out of an enclosed space, and physical entrapment which prevents the diver from leaving a location. The first case can usually be avoided by staying out of enclosed spaces, and when the objective of the dive includes penetration of enclosed spaces, taking precautions such as the use of lights and guidelines, for which specialised training is provided in the standard procedures.[98] The most common form of physical entrapment is getting snagged on ropes, lines or nets, and the use of a cutting implement is the standard method of dealing with the problem. The risk of entanglement can be reduced by careful configuration of equipment to minimise those parts which can easily be snagged, and allow easier disentanglement. Other forms of entrapment such as getting wedged into tight spaces can often be avoided, but must otherwise be dealt with as they happen. The assistance of a buddy may be helpful where possible.[5]

Scuba diving in relatively hazardous environments such as caves and wrecks, areas of strong water movement, relatively great depths, with decompression obligations, with equipment that has more complex failure modes, and with gases that are not safe to breathe at all depths of the dive require specialised safety and emergency procedures tailored to the specific hazards, and often specialised equipment. These conditions are generally associated with technical diving.[47]

The depth range applicable to scuba diving depends on the application and training. Entry-level divers are expected to limit themselves to about 60 feet (18 m) to 20 metres (66 ft).[99] The major worldwide recreational diver certification agencies consider 130 feet (40 m) to be the limit for recreational diving. British and European agencies, including BSAC and SAA, recommend a maximum depth of 50 metres (160 ft)[100] Shallower limits are recommended for divers who are youthful, inexperienced, or who have not taken training for deep dives. Technical diving extends these depth limits through changes to training, equipment, and the gas mix used. The maximum depth considered safe is controversial and varies among agencies and instructors, however, there are programs that train divers for dives to 120 metres (390 ft).[101]

Professional diving usually limits the allowed planned decompression depending on the code of practice, operational directives, or statutory restrictions. Depth limits depend on the jurisdiction, and maximum depths allowed range from 30 metres (100 ft) to more than 50 metres (160 ft), depending on the breathing gas used and the availability of a decompression chamber nearby or on site.[79][43] Commercial diving using scuba is generally restricted for reasons of occupational health and safety. Surface supplied diving allows better control of the operation and eliminates or significantly reduces the risks of loss of breathing gas supply and losing the diver.[102] Scientific and media diving applications may be exempted from commercial diving constraints, based on acceptable codes of practice and a self-regulatory system.[103]

Scuba diving may be performed for a number of reasons, both personal and professional. Recreational diving is done purely for enjoyment and has a number of technical disciplines to increase interest underwater, such as cave diving, wreck diving, ice diving and deep diving.[104][105][106] Underwater tourism is mostly done on scuba and the associated tour guiding must follow suit.[43]

Divers may be employed professionally to perform tasks underwater. Some of these tasks are suitable for scuba.[1][3][43]

There are divers who work, full or part-time, in the recreational diving community as instructors, assistant instructors, divemasters and dive guides. In some jurisdictions, the professional nature, with particular reference to responsibility for health and safety of the clients, of recreational diver instruction, dive leadership for reward and dive guiding is recognised and regulated by national legislation.[43]

Other specialist areas of scuba diving include military diving, with a long history of military frogmen in various roles. Their roles include direct combat, infiltration behind enemy lines, placing mines or using a manned torpedo, bomb disposal or engineering operations.[1] In civilian operations, many police forces operate police diving teams to perform "search and recovery" or "search and rescue" operations and to assist with the detection of crime which may involve bodies of water. In some cases diver rescue teams may also be part of a fire department, paramedical service or lifeguard unit, and may be classed as public safety diving.[43]

Underwater maintenance and research in large aquariums and fish farms, and harvesting of marine biological resources such as fish, abalones, crabs, lobsters, scallops, and sea crayfish may be done on scuba.[43][79] Boat and ship underwater hull inspection, cleaning and some aspects of maintenance (ships husbandry) may be done on scuba by commercial divers and boat owners or crew.[43][79][1]

Lastly, there are professional divers involved with underwater environments, such as underwater photographers or underwater videographers, who document the underwater world, or scientific diving, including marine biology, geology, hydrology, oceanography and underwater archaeology. This work is normally done on scuba as it provides the necessary mobility. Rebreathers may be used when the noise of open-circuit would alarm the subjects or the bubbles could interfere with the images.[3][43][79] Scientific diving under the OSHA (US) exemption has been defined as being diving work done by persons with, and using, scientific expertise to observe, or gather data on, natural phenomena or systems to generate non-proprietary information, data, knowledge or other products as a necessary part of a scientific, research or educational activity, following the direction of a diving safety manual and a diving control safety board.[103]

The choice between scuba and surface-supplied diving equipment is based on both legal and logistical constraints. Where the diver requires mobility and a large range of movement, scuba is usually the choice if safety and legal constraints allow. Higher risk work, particularly in commercial diving, may be restricted to surface-supplied equipment by legislation and codes of practice.[79][43]

The safety of underwater diving depends on four factors: the environment, the equipment, behaviour of the individual diver and performance of the dive team. The underwater environment can impose severe physical and psychological stress on a diver, and is mostly beyond the diver's control. Scuba equipment allows the diver to operate underwater for limited periods, and the reliable function of some of the equipment is critical to even short-term survival. Other equipment allows the diver to operate in relative comfort and efficiency. The performance of the individual diver depends on learned skills, many of which are not intuitive, and the performance of the team depends on competence, communication and common goals.[107]

There is a large range of hazards to which the diver may be exposed. These each have associated consequences and risks, which should be taken into account during dive planning. Where risks are marginally acceptable it may be possible to mitigate the consequences by setting contingency and emergency plans in place, so that damage can be minimised where reasonably practicable. The acceptable level of risk varies depending on legislation, codes of practice and personal choice, with recreational divers having a greater freedom of choice.[43]

Divers operate in an environment for which the human body is not well suited. They face special physical and health risks when they go underwater or use high pressure breathing gas. The consequences of diving incidents range from merely annoying to rapidly fatal, and the result often depends on the equipment, skill, response and fitness of the diver and diving team. The hazards include the aquatic environment, the use of breathing equipment in an underwater environment, exposure to a pressurised environment and pressure changes, particularly pressure changes during descent and ascent, and breathing gases at high ambient pressure. Diving equipment other than breathing apparatus is usually reliable, but has been known to fail, and loss of buoyancy control or thermal protection can be a major burden which may lead to more serious problems. There are also hazards of the specific diving environment, and hazards related to access to and egress from the water, which vary from place to place, and may also vary with time and tide. Hazards inherent in the diver include pre-existing physiological and psychological conditions and the personal behaviour and competence of the individual. For those pursuing other activities while diving, there are additional hazards of task loading, of the dive task and of special equipment associated with the task.[108][109]

The presence of a combination of several hazards simultaneously is common in diving, and the effect is generally increased risk to the diver, particularly where the occurrence of an incident due to one hazard triggers other hazards with a resulting cascade of incidents. Many diving fatalities are the result of a cascade of incidents overwhelming the diver, who should be able to manage any single reasonably foreseeable incident.[110] Although there are many dangers involved in scuba diving, divers can decrease the risks through proper procedures and appropriate equipment. The requisite skills are acquired by training and education, and honed by practice. Entry level certification programmes highlight diving physiology, safe diving practices, and diving hazards, but do not provide the diver with sufficient practice to become truly adept.[110]

Scuba divers, by definition, carry their breathing gas supply with them during the dive, and this limited quantity must get them back to the surface safely. Pre-dive planning of appropriate gas supply for the intended dive profile lets the diver allow for sufficient breathing gas for the planned dive and contingencies.[111] They are not connected to a surface control point by an umbilical, such as surface-supplied divers use, and the freedom of movement that this allows, also allows the diver to penetrate overhead environments in ice diving, cave diving and wreck diving to the extent that the diver may lose their way and be unable to find the way out. This problem is exacerbated by the limited breathing gas supply, which gives a limited amount of time before the diver will drown if unable to surface. The standard procedure for managing this risk is to lay a continuous guideline from open water, which allows the diver to be sure of the route to the surface.[98]

Most scuba diving, particularly recreational scuba, uses a breathing gas supply mouthpiece that is gripped by the diver's teeth, and which can be dislodged relatively easily by impact. This is generally easily rectified unless the diver is incapacitated, and the associated skills are part of entry-level training.[6] The problem becomes severe and immediately life-threatening if the diver loses both consciousness and the mouthpiece. Rebreather mouthpieces that are open when out of the mouth may let in water which can flood the loop, making them unable to deliver breathing gas, and will lose buoyancy as the gas escapes, thus putting the diver in a situation of two simultaneous life-threatening problems.[112] Skills to manage this situation are a necessary part of training for the specific configuration. Full-face masks reduce these risks and are generally preferred for professional scuba diving, but can make emergency gas sharing difficult, and are less popular with recreational divers who often rely on gas sharing with a buddy as their breathing gas redundancy option.[113]

The risk of dying during recreational, scientific or commercial diving is small, and on scuba, deaths are usually associated with poor gas management, poor buoyancy control, equipment misuse, entrapment, rough water conditions and pre-existing health problems. Some fatalities are inevitable and caused by unforeseeable situations escalating out of control, but the majority of diving fatalities can be attributed to human error on the part of the victim. Equipment failure is rare in well-maintained open-circuit scuba that has been set up and tested correctly before the dive.[97]

According to death certificates, over 80% of the deaths were ultimately attributed to drowning, but other factors usually combined to incapacitate the diver in a sequence of events culminating in drowning, which is more a consequence of the medium in which the accidents occurred than the actual accident. Scuba divers should not drown unless there are other contributory factors as they carry a supply of breathing gas and equipment designed to provide the gas on demand. Drowning occurs as a consequence of preceding problems such as unmanageable stress, cardiac disease, pulmonary barotrauma, unconsciousness from any cause, water aspiration, trauma, environmental hazards, equipment difficulties, inappropriate response to an emergency or failure to manage the gas supply.[114] and often obscures the real cause of death. Air embolism is also frequently cited as a cause of death, and it, too is the consequence of other factors leading to an uncontrolled and badly managed ascent, possibly aggravated by medical conditions. About a quarter of diving fatalities are associated with cardiac events, mostly in older divers. There is a fairly large body of data on diving fatalities, but in many cases the data is poor due to the standard of investigation and reporting. This hinders research that could improve diver safety.[97]

Fatality rates are comparable with jogging (13 deaths per 100,000 persons per year) and are within the range where reduction is desirable by Health and Safety Executive (HSE) criteria,[115]The most frequent root cause for diving fatalities is running out of, or low on, gas. Other factors cited include buoyancy control failure, entanglement or entrapment, rough water, equipment misuse or problems, and emergency ascent. The most common injuries and causes of death were drowning or asphyxia due to inhalation of water, air embolism and cardiac events. The risk of cardiac arrest is greater for older divers, and greater for men than women, although the risks are equal by age 65.[115]

Several plausible opinions have been put forward but have not yet been empirically validated. Suggested contributing factors included inexperience, infrequent diving, inadequate supervision, insufficient pre-dive briefings, buddy separation and dive conditions beyond the diver's training, experience or physical capacity.[115]

Decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism in recreational diving have been associated with specific demographic, environmental, and diving behavioural factors. A statistical study published in 2005 tested potential risk factors: age, asthma, body mass index, gender, smoking, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, previous decompression illness, years since certification, number of dives in the previous year, number of consecutive diving days, number of dives in a repetitive series, depth of the previous dive, use of nitrox as breathing gas, and use of a dry suit. No significant associations with risk of decompression sickness or arterial gas embolism were found for asthma, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes or smoking. Greater dive depth, previous decompression illness, number of consecutive days diving, and male sex were associated with higher risk for decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism. The use of dry suits and nitrox breathing gas, greater frequency of diving in the previous year, greater age, and more years since certification were associated with lower risk, possibly as indicators of more extensive training and experience.[citation needed]

Risk management has three major aspects besides equipment and training: Risk assessment, emergency planning and insurance cover. The risk assessment for a dive is primarily a planning activity, and may range in formality from a part of the pre-dive buddy check for recreational divers, to a safety file with professional risk assessment and detailed emergency plans for professional diving projects. Some form of pre-dive briefing is customary with organised recreational dives, and this generally includes a recitation by the divemaster of the known and predicted hazards, the risk associated with the significant ones, and the procedures to be followed in case of the reasonably foreseeable emergencies associated with them. Insurance cover for diving accidents may not be included in standard policies. There are a few organisations that focus specifically on diver safety and insurance cover, such as the international Divers Alert Network[116]

A scuba emergency is an incident in which there is a high probability of death or severe injury if the problem is not resolved quickly.

The most urgent scuba emergency is running out of breathing gas under water, often referred to as an out-of-air incident. It is a true emergency, as without access to breathing gas the diver will die within a few minutes. This emergency can be managed in several ways including assistance by a dive buddy, if the buddy is close enough to help, by sharing breathing gas. Other responses are by the diver providing themself with an alternative (bailout) scuba source, which does not rely on a buddy. Another alternative which is viable if the decompression risk is low, and there is no hard overhead,is to make an emergency ascent, which also does not rely on a buddy.

Other interruptions to the breathing gas supply, such as regulator malfunctions, dislodging of the regulator or full-face mask, rolling off of the cylinder valve, may become emergencies if not managed promptly and effectively, though for a competent diver most of these should be inconveniences rather than emergencies if there are no compounding factors.

Oxygen toxicity convulsions involve a temporary loss of consciousness, during which the diver can lose the mouthpiece and consequently drown. An observant buddy might be able to help.

Hypoxia causing loss of consciousness can be due to breathing from the wrong cylinder for the current depth, or a rebreather malfunction. An observant and competent buddy may be able to help.

Irretrievable loss of buoyancy control can be an emergency depending on when it occurs, whether it is a loss of buoyancy (eg BC failure, catastrophic dry suit flood), or an excess of buoyancy (loss of weights, insufficient weighting at end of deco dive), whether there is enough breathing gas in reserve, and whether there is a decompression obligation. An observant buddy might be able to help in some circumstances. (types and causes, management options) Insufficient weighting at the end of a dive when no weights have been lost is usually an indication of inadequate training and failure of the diver to take responsibility for their own safety, and is usually caused by the diver not adequately checking that they are correctly weighted for the dive, and is often partly due to poor advice from rental equipment providers.

Symptomatic omitted or insufficient decompression. The urgency depends on the symptoms and when they occur (pain, neurological effects, inner ear/vertigo and nuasea). In some cases an observant and competent buddy might be able to help. (response to different symptoms)

Carbon dioxide toxicity due to rebreather scrubber breakthrough.

Overwhelming work of breathing could be caused by high gas density, regulator malfunction, loop flood in a rebreather, or excessive exertion with hypercapnia. A buddy with lower work of breathing may be able to perform a rescue, depending on the cause of the high WoB.

A dry suit flooding in frigid water presents combined risks from buoyancy loss and hypothermia. There is nothing the buddy can do to help for hypothermia, and not much for buoyancy loss. This is not as urgent as breathing emergencies, but can be a definite risk to life.

Loss of the guideline in a cave or wreck when out of sight of the exit. A buddy may be able to help depending on circumstances.

_training._(49085148586).jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Scuba training is normally provided by a qualified instructor who is a member of one or more diver certification agencies or is registered with a government agency. Basic diver training entails the learning of skills required for the safe conduct of activities in an underwater environment, and includes procedures and skills for the use of diving equipment, safety, emergency self-help and rescue procedures, dive planning, and use of dive tables or a personal dive computer.[6]

Scuba skills which an entry-level diver will normally learn include:[6][117]

Some knowledge of physiology and the physics of diving is considered necessary by most diver certification agencies, as the diving environment is alien and relatively hostile to humans. The physics and physiology knowledge required is fairly basic, and helps the diver to understand the effects of the diving environment so that informed acceptance of the associated risks is possible.[117][6] The physics mostly relates to gases under pressure, buoyancy, heat loss, and light underwater. The physiology relates the physics to the effects on the human body, to provide a basic understanding of the causes and risks of barotrauma, decompression sickness, gas toxicity, hypothermia, drowning and sensory variations.[117][6] More advanced training often involves first aid and rescue skills, skills related to specialised diving equipment, and underwater work skills.[117]

.jpg/440px-Frau_beim_Tauchen_(2).jpg)