Un reloj de sol es un dispositivo de relojería que indica la hora del día (denominado hora civil en el uso moderno) cuando la luz solar directa brilla por la posición aparente del Sol en el cielo . En el sentido más estricto de la palabra, consta de una placa plana (la esfera ) y un gnomon , que proyecta una sombra sobre la esfera. A medida que el Sol parece moverse por el cielo, la sombra se alinea con diferentes líneas horarias, que están marcadas en la esfera para indicar la hora del día. El estilo es el borde que indica la hora del gnomon, aunque se puede utilizar un solo punto o nodus . El gnomon proyecta una sombra amplia; la sombra del estilo muestra la hora. El gnomon puede ser una varilla, un alambre o una fundición de metal elaboradamente decorada. El estilo debe ser paralelo al eje de rotación de la Tierra para que el reloj de sol sea preciso durante todo el año. El ángulo del estilo con respecto a la horizontal es igual a la latitud geográfica del reloj de sol .

El término reloj de sol puede referirse a cualquier dispositivo que utilice la altura o el acimut del Sol (o ambos) para mostrar la hora. Los relojes de sol son valorados como objetos decorativos, metáforas y objetos de intriga y estudio matemático.

El paso del tiempo se puede observar colocando un palo en la arena o un clavo en una tabla y colocando marcadores en el borde de una sombra o delineando una sombra a intervalos. Es común que los relojes de sol decorativos de bajo costo y de producción en masa tengan gnomones, longitudes de sombra y líneas horarias mal alineadas, que no se pueden ajustar para indicar la hora correcta. [2]

Existen distintos tipos de relojes de sol. Algunos relojes de sol utilizan una sombra o el borde de una sombra, mientras que otros utilizan una línea o un punto de luz para indicar la hora.

El objeto que proyecta la sombra, conocido como gnomon , puede ser una varilla larga y delgada u otro objeto con una punta afilada o un borde recto. Los relojes de sol emplean muchos tipos de gnomon. El gnomon puede ser fijo o móvil según la estación. Puede estar orientado verticalmente, horizontalmente, alineado con el eje de la Tierra o en una dirección completamente diferente determinada por las matemáticas.

Dado que los relojes de sol utilizan la luz para indicar el tiempo, se puede formar una línea de luz al permitir que los rayos del Sol pasen a través de una ranura delgada o al enfocarlos a través de una lente cilíndrica . Se puede formar un punto de luz al permitir que los rayos del Sol pasen a través de un pequeño orificio, ventana, óculo , o al reflejarlos desde un pequeño espejo circular. Un punto de luz puede ser tan pequeño como un agujero de alfiler en un solarógrafo o tan grande como el óculo del Panteón.

Los relojes de sol también pueden utilizar muchos tipos de superficies para recibir la luz o la sombra. Los planos son la superficie más común, pero se han utilizado esferas parciales , cilindros , conos y otras formas para lograr una mayor precisión o belleza.

Los relojes de sol se diferencian por su portabilidad y su necesidad de orientación. La instalación de muchos relojes requiere conocer la latitud local , la dirección vertical precisa (por ejemplo, mediante un nivel o una plomada) y la dirección hacia el norte verdadero . Los relojes portátiles se alinean automáticamente: por ejemplo, pueden tener dos relojes que funcionan según principios diferentes, como un reloj horizontal y otro analemático , montados juntos en una placa. En estos diseños, sus horas coinciden solo cuando la placa está alineada correctamente.

Los relojes de sol pueden indicar únicamente la hora solar local . Para obtener la hora del reloj nacional, se requieren tres correcciones:

Los principios de los relojes solares se entienden más fácilmente a partir del movimiento aparente del Sol . [3] La Tierra rota sobre su eje y gira en una órbita elíptica alrededor del Sol. Una excelente aproximación supone que el Sol gira alrededor de una Tierra estacionaria en la esfera celeste , que rota cada 24 horas sobre su eje celeste. El eje celeste es la línea que conecta los polos celestes . Dado que el eje celeste está alineado con el eje sobre el que gira la Tierra, el ángulo del eje con la horizontal local es la latitud geográfica local .

A diferencia de las estrellas fijas , el Sol cambia su posición en la esfera celeste, estando (en el hemisferio norte) en declinación positiva en primavera y verano, y en declinación negativa en otoño e invierno, y teniendo exactamente declinación cero (es decir, estando en el ecuador celeste ) en los equinoccios . La longitud celeste del Sol también varía, cambiando una revolución completa por año. La trayectoria del Sol en la esfera celeste se llama eclíptica . La eclíptica pasa por las doce constelaciones del zodíaco en el transcurso de un año.

Este modelo del movimiento del Sol ayuda a comprender los relojes solares. Si el gnomon que proyecta la sombra está alineado con los polos celestes , su sombra girará a una velocidad constante y esta rotación no cambiará con las estaciones. Este es el diseño más común. En tales casos, se pueden utilizar las mismas líneas horarias durante todo el año. Las líneas horarias estarán espaciadas uniformemente si la superficie que recibe la sombra es perpendicular (como en el reloj solar ecuatorial) o circular alrededor del gnomon (como en la esfera armilar ).

En otros casos, las líneas horarias no están espaciadas uniformemente, aunque la sombra gire uniformemente. Si el gnomon no está alineado con los polos celestes, incluso su sombra no girará uniformemente, y las líneas horarias deben corregirse en consecuencia. Los rayos de luz que rozan la punta de un gnomon, o que pasan a través de un pequeño orificio, o se reflejan en un pequeño espejo, trazan un cono alineado con los polos celestes. El punto de luz o la punta de la sombra correspondiente, si cae sobre una superficie plana, trazará una sección cónica , como una hipérbola , una elipse o (en los polos norte o sur) un círculo .

Esta sección cónica es la intersección del cono de rayos de luz con la superficie plana. Este cono y su sección cónica cambian con las estaciones, a medida que cambia la declinación del Sol; por lo tanto, los relojes de sol que siguen el movimiento de dichos puntos de luz o puntas de sombra a menudo tienen diferentes líneas horarias para diferentes épocas del año. Esto se ve en los diales de pastor, los anillos de los relojes de sol y los gnomones verticales como los obeliscos. Alternativamente, los relojes de sol pueden cambiar el ángulo o la posición (o ambos) del gnomon en relación con las líneas horarias, como en el dial analemático o el dial de Lambert.

Los primeros relojes de sol conocidos a partir del registro arqueológico son relojes de sombras (1500 a. C. o a. C. ) de la astronomía del antiguo Egipto y la astronomía babilónica . Presumiblemente, los humanos ya medían el tiempo a partir de las longitudes de las sombras en una fecha incluso anterior, pero esto es difícil de verificar. Aproximadamente en el 700 a. C., el Antiguo Testamento describe un reloj de sol: el "reloj de Acaz" mencionado en Isaías 38:8 y 2 Reyes 20:11. Hacia el 240 a. C., Eratóstenes había estimado la circunferencia del mundo utilizando un obelisco y un pozo de agua y unos siglos más tarde, Ptolomeo había cartografiado la latitud de las ciudades utilizando el ángulo del sol. La gente de Kush creó relojes de sol a través de la geometría. [4] [5] El escritor romano Vitruvio enumera los relojes de sombras y los relojes de sombra conocidos en esa época en su De architectura . La Torre de los Vientos construida en Atenas incluía un reloj de sol y un reloj de agua para medir el tiempo. Un reloj de sol canónico es aquel que indica las horas canónicas de los actos litúrgicos. Este tipo de relojes fueron utilizados desde el siglo VII al XIV por los miembros de las comunidades religiosas. El astrónomo italiano Giovanni Padovani publicó un tratado sobre el reloj de sol en 1570, en el que incluía instrucciones para la fabricación y el diseño de relojes de sol murales (verticales) y horizontales. La Constructio instrumenti ad horologia solaria (c. 1620) de Giuseppe Biancani analiza cómo hacer un reloj de sol perfecto. Se han utilizado comúnmente desde el siglo XVI.

En general, los relojes de sol indican la hora proyectando una sombra o arrojando luz sobre una superficie conocida como esfera o placa de esfera . Aunque normalmente es una superficie plana, la esfera también puede ser la superficie interior o exterior de una esfera, un cilindro, un cono, una hélice y otras formas diversas.

La hora se indica cuando una sombra o luz cae sobre la esfera, que suele estar marcada con líneas horarias. Aunque normalmente son rectas, estas líneas horarias también pueden ser curvas, según el diseño del reloj de sol (véase más abajo). En algunos diseños, es posible determinar la fecha del año, o puede ser necesario conocer la fecha para encontrar la hora correcta. En tales casos, puede haber varios conjuntos de líneas horarias para diferentes meses, o puede haber mecanismos para configurar/calcular el mes. Además de las líneas horarias, la esfera puede ofrecer otros datos (como el horizonte, el ecuador y los trópicos), a los que se hace referencia colectivamente como los elementos de la esfera.

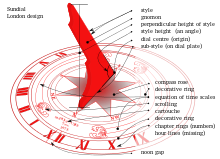

El objeto entero que proyecta una sombra o luz sobre la cara del dial se conoce como gnomon del reloj de sol . [6] Sin embargo, normalmente es solo un borde del gnomon (u otra característica lineal) la que proyecta la sombra utilizada para determinar la hora; esta característica lineal se conoce como estilo del reloj de sol . El estilo suele estar alineado en paralelo al eje de la esfera celeste y, por lo tanto, está alineado con el meridiano geográfico local. En algunos diseños de relojes de sol, solo se utiliza una característica puntual, como la punta del estilo, para determinar la hora y la fecha; esta característica puntual se conoce como nodus del reloj de sol . [6] [a] Algunos relojes de sol utilizan tanto un estilo como un nodus para determinar la hora y la fecha.

El gnomon suele estar fijo en relación con la esfera del reloj, pero no siempre; en algunos diseños, como el reloj de sol analemático, el estilo se mueve según el mes. Si el estilo es fijo, la línea en la placa del reloj perpendicularmente debajo del estilo se llama subestilo , [ 6] que significa "debajo del estilo". El ángulo que forma el estilo con el plano de la placa del reloj se llama altura del subestilo, un uso inusual de la palabra altura para significar un ángulo . En muchos relojes de pared, el subestilo no es lo mismo que la línea del mediodía (ver más abajo). El ángulo en la placa del reloj entre la línea del mediodía y el subestilo se llama distancia del subestilo , un uso inusual de la palabra distancia para significar un ángulo .

Según la tradición, muchos relojes de sol tienen un lema . El lema suele tener la forma de un epigrama : a veces son reflexiones sombrías sobre el paso del tiempo y la brevedad de la vida, pero también son ocurrencias humorísticas del fabricante de relojes. Una de esas ocurrencias es: Soy un reloj de sol y hago una chapuza de lo que un reloj hace mucho mejor. [7]

Se dice que una esfera es equiangular si sus líneas horarias son rectas y están espaciadas de manera uniforme. La mayoría de los relojes solares equiangulares tienen un estilo de gnomon fijo alineado con el eje de rotación de la Tierra, así como una superficie receptora de sombras que es simétrica respecto de ese eje; algunos ejemplos son la esfera ecuatorial, el arco ecuatorial, la esfera armilar, la esfera cilíndrica y la esfera cónica. Sin embargo, otros diseños son equiangulares, como la esfera Lambert, una versión del reloj solar analemático con un estilo móvil.

Un reloj de sol en una latitud particular en un hemisferio debe invertirse para su uso en la latitud opuesta en el otro hemisferio. [8] Un reloj de sol vertical directo al sur en el hemisferio norte se convierte en un reloj de sol vertical directo al norte en el hemisferio sur . Para colocar un reloj de sol horizontal correctamente, uno tiene que encontrar el norte o el sur verdaderos . El mismo proceso se puede utilizar para hacer ambas cosas. [9] El gnomon, ajustado a la latitud correcta, tiene que apuntar al sur verdadero en el hemisferio sur, así como en el hemisferio norte tiene que apuntar al norte verdadero. [10] Los números de las horas también corren en direcciones opuestas, por lo que en un dial horizontal corren en sentido antihorario (EE. UU.: antihorario) en lugar de en el sentido de las agujas del reloj. [11]

Los relojes de sol que están diseñados para usarse con sus placas horizontales en un hemisferio pueden usarse con sus placas verticales en la latitud complementaria en el otro hemisferio. Por ejemplo, el reloj de sol ilustrado en Perth , Australia , que está en la latitud 32° Sur, funcionaría correctamente si estuviera montado en una pared vertical orientada al sur en la latitud 58° (es decir, 90° − 32°) Norte, que está un poco más al norte que Perth, Escocia . La superficie de la pared en Escocia sería paralela al suelo horizontal en Australia (ignorando la diferencia de longitud), por lo que el reloj de sol funcionaría de manera idéntica en ambas superficies. En consecuencia, las marcas de las horas, que corren en sentido contrario a las agujas del reloj en un reloj de sol horizontal en el hemisferio sur, también lo hacen en un reloj de sol vertical en el hemisferio norte. (Vea las primeras dos ilustraciones en la parte superior de este artículo). En los relojes de sol horizontales del hemisferio norte, y en los verticales del hemisferio sur, las marcas de las horas corren en el sentido de las agujas del reloj.

La razón más común por la que un reloj de sol difiere mucho de la hora del reloj es que el reloj de sol no ha sido orientado correctamente o sus líneas horarias no han sido dibujadas correctamente. Por ejemplo, la mayoría de los relojes de sol comerciales están diseñados como relojes de sol horizontales, como se describió anteriormente. Para ser precisos, un reloj de sol de este tipo debe haber sido diseñado para la latitud geográfica local y su estilo debe ser paralelo al eje de rotación de la Tierra; el estilo debe estar alineado con el norte verdadero y su altura (su ángulo con la horizontal) debe ser igual a la latitud local. Para ajustar la altura del estilo, el reloj de sol a menudo se puede inclinar ligeramente "hacia arriba" o "hacia abajo" mientras se mantiene la alineación norte-sur del estilo. [12]

En algunas zonas del mundo se aplica el horario de verano , que modifica la hora oficial, normalmente en una hora. Este cambio debe sumarse a la hora del reloj de sol para que coincida con la hora oficial.

Una zona horaria estándar cubre aproximadamente 15° de longitud, por lo que cualquier punto dentro de esa zona que no esté en la longitud de referencia (generalmente un múltiplo de 15°) experimentará una diferencia con la hora estándar que es igual a 4 minutos de tiempo por grado. A modo de ejemplo, las puestas y salidas del sol son mucho más tardías en el tiempo "oficial" en el extremo occidental de una zona horaria, en comparación con las horas de salida y puesta del sol en el extremo oriental. Si un reloj de sol está ubicado, por ejemplo, en una longitud 5° al oeste de la longitud de referencia, entonces su hora se leerá 20 minutos más tarde, ya que el Sol parece girar alrededor de la Tierra a 15° por hora. Esta es una corrección constante durante todo el año. Para los diales equiangulares, como los diales ecuatoriales, esféricos o Lambert, esta corrección se puede realizar girando la superficie del dial en un ángulo igual a la diferencia de longitud, sin cambiar la posición u orientación del gnomon. Sin embargo, este método no funciona para otros diales, como un dial horizontal; la corrección debe ser aplicada por el espectador.

Sin embargo, por razones políticas y prácticas, los límites de las zonas horarias se han distorsionado. En sus casos más extremos, las zonas horarias pueden hacer que el mediodía oficial, incluido el horario de verano, se produzca hasta tres horas antes (en cuyo caso, el Sol está realmente en el meridiano a la hora oficial del reloj, las 3:00 p. m. ). Esto ocurre en el extremo oeste de Alaska , China y España . Para obtener más detalles y ejemplos, consulte husos horarios .

Aunque el Sol parece girar de manera uniforme alrededor de la Tierra, en realidad este movimiento no es perfectamente uniforme. Esto se debe a la excentricidad de la órbita de la Tierra (el hecho de que la órbita de la Tierra alrededor del Sol no es perfectamente circular, sino ligeramente elíptica ) y la inclinación (oblicuidad) del eje de rotación de la Tierra con respecto al plano de su órbita. Por lo tanto, la hora del reloj de sol varía con respecto a la hora del reloj estándar . En cuatro días del año, la corrección es efectivamente cero. Sin embargo, en otros, puede ser hasta un cuarto de hora antes o después. La cantidad de corrección se describe mediante la ecuación del tiempo . Esta corrección es igual en todo el mundo: no depende de la latitud o longitud local de la posición del observador. Sin embargo, cambia durante largos períodos de tiempo (siglos o más, [13] ) debido a las lentas variaciones en los movimientos orbitales y rotacionales de la Tierra. Por lo tanto, las tablas y gráficos de la ecuación del tiempo que se hicieron hace siglos ahora son significativamente incorrectos. La lectura de un reloj de sol antiguo debe corregirse aplicando la ecuación del tiempo actual, no la del período en que se fabricó el reloj.

En algunos relojes de sol, la ecuación de corrección de la hora se proporciona como una placa informativa fijada al reloj de sol, para que el observador la calcule. En relojes de sol más sofisticados, la ecuación se puede incorporar automáticamente. Por ejemplo, algunos relojes de sol con arco ecuatorial se suministran con una pequeña rueda que establece la hora del año; esta rueda a su vez hace girar el arco ecuatorial, compensando su medición de la hora. En otros casos, las líneas horarias pueden ser curvas, o el arco ecuatorial puede tener forma de jarrón, lo que aprovecha la altitud cambiante del sol a lo largo del año para lograr el desfase horario adecuado. [14]

Un heliocronómetro es un reloj solar de precisión ideado por primera vez en 1763 aproximadamente por Philipp Hahn y mejorado por Abbé Guyoux en 1827 aproximadamente. [15] Corrige el tiempo solar aparente para que signifique el tiempo solar u otro tiempo estándar . Los heliocronómetros suelen indicar los minutos con una precisión de 1 minuto respecto del Tiempo Universal .

El reloj de sol Sunquest , diseñado por Richard L. Schmoyer en la década de 1950, utiliza un gnomon de inspiración analémica para proyectar un haz de luz sobre una medialuna de escala de tiempo ecuatorial. Sunquest es ajustable en latitud y longitud, corrigiendo automáticamente la ecuación del tiempo, lo que lo hace "tan preciso como la mayoría de los relojes de bolsillo". [16] [17] [18] [19]

De manera similar, en lugar de la sombra de un gnomon, el reloj solar de la Universidad Miguel Hernández utiliza la proyección solar de una gráfica de la ecuación del tiempo que interseca una escala de tiempo para mostrar directamente la hora del reloj.

A muchos tipos de relojes de sol se les puede añadir un analema para corregir la hora solar aparente y convertirla en hora solar media u otra hora estándar . Estos suelen tener líneas horarias con forma de "ocho" ( analemas ) según la ecuación del tiempo . Esto compensa la ligera excentricidad de la órbita de la Tierra y la inclinación del eje de la Tierra que provoca una variación de hasta 15 minutos con respecto a la hora solar media. Este es un tipo de mecanismo de cuadrante que se observa en cuadrantes horizontales y verticales más complicados.

Antes de la invención de los relojes de precisión, a mediados del siglo XVII, los relojes de sol eran los únicos relojes de uso común y se consideraba que indicaban la hora "correcta". La ecuación del tiempo no se utilizaba. Tras la invención de los buenos relojes, los relojes de sol seguían considerándose correctos y los relojes, por lo general, incorrectos. La ecuación del tiempo se utilizaba en sentido inverso a la actual, para aplicar una corrección a la hora que mostraba un reloj para que coincidiera con la hora del reloj de sol. Algunos " relojes de ecuación " elaborados, como el fabricado por Joseph Williamson en 1720, incorporaban mecanismos para realizar esta corrección automáticamente. (El reloj de Williamson puede haber sido el primer dispositivo en utilizar un engranaje diferencial ). Sólo después de 1800 aproximadamente se consideró que la hora del reloj sin corregir era "correcta" y la hora del reloj de sol, por lo general, "incorrecta", por lo que la ecuación del tiempo pasó a utilizarse tal como se utiliza hoy en día. [20]

Los relojes solares más comunes son aquellos en los que el estilo de proyección de sombras está fijo en su posición y alineado con el eje de rotación de la Tierra, estando orientado con el norte y el sur verdaderos , y formando un ángulo con la horizontal igual a la latitud geográfica. Este eje está alineado con los polos celestes , que están estrechamente, pero no perfectamente, alineados con la estrella polar Polaris . A modo de ejemplo, el eje celeste apunta verticalmente al verdadero Polo Norte , mientras que apunta horizontalmente al ecuador . El reloj solar gnomon axial más grande del mundo es el mástil del Puente Sundial en Turtle Bay en Redding, California . Un gnomon que antes era el más grande del mundo se encuentra en Jaipur , elevado 26°55′ sobre la horizontal, lo que refleja la latitud local. [21]

En un día cualquiera, el Sol parece rotar uniformemente sobre este eje, a unos 15° por hora, haciendo un circuito completo (360°) en 24 horas. Un gnomon lineal alineado con este eje proyectará una lámina de sombra (un semiplano) que, al caer en sentido opuesto al Sol, también rota sobre el eje celeste a 15° por hora. La sombra se ve al caer sobre una superficie receptora que normalmente es plana, pero que puede ser esférica, cilíndrica, cónica o de otras formas. Si la sombra cae sobre una superficie que es simétrica respecto del eje celeste (como en una esfera armilar o un dial ecuatorial), la sombra de la superficie también se mueve uniformemente; las líneas horarias del reloj solar están espaciadas de forma uniforme. Sin embargo, si la superficie receptora no es simétrica (como en la mayoría de los relojes solares horizontales), la sombra de la superficie generalmente se mueve de forma no uniforme y las líneas horarias no están espaciadas de forma uniforme; una excepción es el dial Lambert que se describe a continuación.

Algunos tipos de relojes de sol están diseñados con un gnomon fijo que no está alineado con los polos celestes como un obelisco vertical. Estos relojes de sol se describen a continuación en la sección "Relojes de sol basados en Nodus".

Las fórmulas que se muestran en los párrafos siguientes permiten calcular las posiciones de las líneas horarias para varios tipos de relojes de sol. En algunos casos, los cálculos son sencillos; en otros, son extremadamente complicados. Existe un método alternativo y sencillo para encontrar las posiciones de las líneas horarias que se puede utilizar para muchos tipos de relojes de sol y que ahorra mucho trabajo en los casos en que los cálculos son complejos. [22] Se trata de un procedimiento empírico en el que se marca la posición de la sombra del gnomon de un reloj de sol real a intervalos de una hora. Se debe tener en cuenta la ecuación del tiempo para garantizar que las posiciones de las líneas horarias sean independientes de la época del año en que se marquen. Una forma sencilla de hacerlo es configurar un reloj de manera que muestre la "hora del reloj de sol" [b], que es la hora estándar , [c] más la ecuación del tiempo del día en cuestión. [d] Las líneas horarias del reloj de sol se marcan para mostrar las posiciones de la sombra del estilo cuando este reloj muestra números enteros de horas, y se etiquetan con estos números de horas. Por ejemplo, cuando el reloj marca las 5:00, la sombra del estilo se marca y se etiqueta como "5" (o "V" en números romanos ). Si las líneas de las horas no están todas marcadas en un solo día, el reloj debe ajustarse cada uno o dos días para tener en cuenta la variación de la ecuación del tiempo.

La característica distintiva de la esfera ecuatorial (también llamada esfera equinoccial ) es la superficie plana que recibe la sombra, que es exactamente perpendicular al estilo del gnomon. [25] Este plano se llama ecuatorial, porque es paralelo al ecuador de la Tierra y de la esfera celeste. Si el gnomon está fijo y alineado con el eje de rotación de la Tierra, la rotación aparente del sol alrededor de la Tierra proyecta una lámina de sombra que gira uniformemente desde el gnomon; esto produce una línea de sombra que gira uniformemente en el plano ecuatorial. Dado que la Tierra gira 360° en 24 horas, las líneas horarias en una esfera ecuatorial están todas espaciadas a 15° (360/24).

La uniformidad de su espaciado hace que este tipo de reloj solar sea fácil de construir. Si el material de la placa de la esfera es opaco, ambos lados de la esfera ecuatorial deben marcarse, ya que la sombra se proyectará desde abajo en invierno y desde arriba en verano. Con placas de esfera translúcidas (por ejemplo, de vidrio), los ángulos horarios solo deben marcarse en el lado que mira hacia el sol, aunque las numeraciones de las horas (si se usan) deben hacerse en ambos lados de la esfera, debido al diferente esquema horario en los lados que miran hacia el sol y los que están detrás de él.

Otra ventaja importante de esta esfera es que las correcciones de la ecuación de tiempo (EoT) y del horario de verano (DST) se pueden realizar simplemente girando la placa de la esfera en el ángulo apropiado cada día. Esto se debe a que los ángulos horarios están espaciados de manera uniforme alrededor de la esfera. Por esta razón, una esfera ecuatorial suele ser una opción útil cuando la esfera se exhibe al público y es deseable que muestre la hora local real con una precisión razonable. La corrección de la ecuación de tiempo (EoT) se realiza mediante la relación

Cerca de los equinoccios de primavera y otoño, el sol se mueve en un círculo que es casi igual al plano ecuatorial; por lo tanto, no se produce una sombra clara en la esfera ecuatorial en esas épocas del año, un inconveniente del diseño.

A veces se añade un nodo a los relojes de sol ecuatoriales, lo que permite que el reloj indique la época del año. En un día determinado, la sombra del nodo se mueve en un círculo en el plano ecuatorial, y el radio del círculo mide la declinación del sol. Los extremos de la barra del gnomon pueden usarse como nodo, o algún elemento a lo largo de su longitud. Una variante antigua del reloj de sol ecuatorial tiene solo un nodo (sin estilo) y las líneas horarias circulares concéntricas están dispuestas para parecerse a una telaraña. [26]

En el reloj de sol horizontal (también llamado reloj de sol de jardín ), el plano que recibe la sombra está alineado horizontalmente, en lugar de ser perpendicular al estilo como en el dial ecuatorial. [27] Por lo tanto, la línea de sombra no gira uniformemente en la cara del dial; más bien, las líneas de las horas están espaciadas de acuerdo con la regla. [28]

O en otros términos:

donde L es la latitud geográfica del reloj de sol (y el ángulo que forma el gnomon con la placa del dial), es el ángulo entre una línea horaria dada y la línea horaria del mediodía (que siempre apunta hacia el norte verdadero ) en el plano, y t es el número de horas antes o después del mediodía. Por ejemplo, el ángulo de la línea horaria de las 3 p. m. sería igual a la arcotangente de sen L , ya que tan 45° = 1. Cuando (en el Polo Norte ), el reloj de sol horizontal se convierte en un reloj de sol ecuatorial; el estilo apunta hacia arriba (verticalmente) y el plano horizontal está alineado con el plano ecuatorial; la fórmula de la línea horaria se convierte en la de un dial ecuatorial. Un reloj de sol horizontal en el ecuador de la Tierra , donde requeriría un estilo horizontal (elevado) y sería un ejemplo de un reloj de sol polar (ver más abajo).

Las principales ventajas del reloj de sol horizontal son que es fácil de leer y que la luz del sol ilumina la esfera durante todo el año. Todas las líneas horarias se cruzan en el punto donde el estilo del gnomon cruza el plano horizontal. Dado que el estilo está alineado con el eje de rotación de la Tierra, el estilo apunta al norte verdadero y su ángulo con la horizontal es igual a la latitud geográfica del reloj de sol L . Un reloj de sol diseñado para una latitud se puede ajustar para su uso en otra latitud inclinando su base hacia arriba o hacia abajo en un ángulo igual a la diferencia de latitud. Por ejemplo, un reloj de sol diseñado para una latitud de 40° se puede utilizar en una latitud de 45°, si el plano del reloj de sol está inclinado hacia arriba 5°, alineando así el estilo con el eje de rotación de la Tierra. [ cita requerida ]

Muchos relojes de sol ornamentales están diseñados para usarse a 45 grados norte. Algunos relojes de sol de jardín producidos en masa no calculan correctamente las líneas horarias y, por lo tanto, nunca se pueden corregir. Una zona horaria estándar local tiene nominalmente 15 grados de ancho, pero puede modificarse para seguir los límites geográficos o políticos. Un reloj de sol se puede girar sobre su estilo (que debe permanecer apuntando al polo celeste) para ajustarse a la zona horaria local. En la mayoría de los casos, una rotación en el rango de 7,5° este a 23° oeste es suficiente. Esto introducirá un error en los relojes de sol que no tienen ángulos horarios iguales. Para corregir el horario de verano , una esfera necesita dos juegos de números o una tabla de corrección. Un estándar informal es tener números en colores cálidos para el verano y en colores fríos para el invierno. [ cita requerida ] Dado que los ángulos horarios no están espaciados de manera uniforme, la ecuación de las correcciones de tiempo no se puede realizar girando la placa del dial sobre el eje del gnomon. Este tipo de diales suelen tener una tabla de corrección de la ecuación de tiempo grabada en sus pedestales o cerca de ellos. Los diales horizontales se ven comúnmente en jardines, cementerios y áreas públicas.

En la esfera vertical común , el plano receptor de sombra está alineado verticalmente; como es habitual, el estilo del gnomon está alineado con el eje de rotación de la Tierra. [29] Al igual que en la esfera horizontal, la línea de sombra no se mueve uniformemente en la esfera; el reloj de sol no es equiangular . Si la cara de la esfera vertical apunta directamente al sur, el ángulo de las líneas horarias se describe mediante la fórmula [30]

donde L es la latitud geográfica del reloj de sol , es el ángulo entre una línea horaria dada y la línea horaria del mediodía (que siempre apunta al norte) en el plano, y t es el número de horas antes o después del mediodía. Por ejemplo, el ángulo de la línea horaria de las 3 p. m. sería igual a la arcotangente de cos L , ya que tan 45° = 1. La sombra se mueve en sentido antihorario en un dial vertical orientado al sur, mientras que corre en el sentido de las agujas del reloj en diales horizontales y ecuatoriales orientados al norte.

Dials with faces perpendicular to the ground and which face directly south, north, east, or west are called vertical direct dials.[31] It is widely believed, and stated in respectable publications, that a vertical dial cannot receive more than twelve hours of sunlight a day, no matter how many hours of daylight there are.[32] However, there is an exception. Vertical sundials in the tropics which face the nearer pole (e.g. north facing in the zone between the Equator and the Tropic of Cancer) can actually receive sunlight for more than 12 hours from sunrise to sunset for a short period around the time of the summer solstice. For example, at latitude 20° North, on June 21, the sun shines on a north-facing vertical wall for 13 hours, 21 minutes.[33] Vertical sundials which do not face directly south (in the northern hemisphere) may receive significantly less than twelve hours of sunlight per day, depending on the direction they do face, and on the time of year. For example, a vertical dial that faces due East can tell time only in the morning hours; in the afternoon, the sun does not shine on its face. Vertical dials that face due East or West are polar dials, which will be described below. Vertical dials that face north are uncommon, because they tell time only during the spring and summer, and do not show the midday hours except in tropical latitudes (and even there, only around midsummer). For non-direct vertical dials – those that face in non-cardinal directions – the mathematics of arranging the style and the hour-lines becomes more complicated; it may be easier to mark the hour lines by observation, but the placement of the style, at least, must be calculated first; such dials are said to be declining dials.[34]

Vertical dials are commonly mounted on the walls of buildings, such as town-halls, cupolas and church-towers, where they are easy to see from far away. In some cases, vertical dials are placed on all four sides of a rectangular tower, providing the time throughout the day. The face may be painted on the wall, or displayed in inlaid stone; the gnomon is often a single metal bar, or a tripod of metal bars for rigidity. If the wall of the building faces toward the south, but does not face due south, the gnomon will not lie along the noon line, and the hour lines must be corrected. Since the gnomon's style must be parallel to the Earth's axis, it always "points" true north and its angle with the horizontal will equal the sundial's geographical latitude; on a direct south dial, its angle with the vertical face of the dial will equal the colatitude, or 90° minus the latitude.[35]

.jpg/440px-Reloj_de_sol_polar_en_Donramiro_(Lalín,_España).jpg)

In polar dials, the shadow-receiving plane is aligned parallel to the gnomon-style.[36]Thus, the shadow slides sideways over the surface, moving perpendicularly to itself as the Sun rotates about the style. As with the gnomon, the hour-lines are all aligned with the Earth's rotational axis. When the Sun's rays are nearly parallel to the plane, the shadow moves very quickly and the hour lines are spaced far apart. The direct East- and West-facing dials are examples of a polar dial. However, the face of a polar dial need not be vertical; it need only be parallel to the gnomon. Thus, a plane inclined at the angle of latitude (relative to horizontal) under the similarly inclined gnomon will be a polar dial. The perpendicular spacing X of the hour-lines in the plane is described by the formula

where H is the height of the style above the plane, and t is the time (in hours) before or after the center-time for the polar dial. The center time is the time when the style's shadow falls directly down on the plane; for an East-facing dial, the center time will be 6 A.M., for a West-facing dial, this will be 6 P.M., and for the inclined dial described above, it will be noon. When t approaches ±6 hours away from the center time, the spacing X diverges to +∞; this occurs when the Sun's rays become parallel to the plane.

A declining dial is any non-horizontal, planar dial that does not face in a cardinal direction, such as (true) north, south, east or west.[37] As usual, the gnomon's style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, but the hour-lines are not symmetrical about the noon hour-line. For a vertical dial, the angle between the noon hour-line and another hour-line is given by the formula below. Note that is defined positive in the clockwise sense w.r.t. the upper vertical hour angle; and that its conversion to the equivalent solar hour requires careful consideration of which quadrant of the sundial that it belongs in.[38]

where is the sundial's geographical latitude; t is the time before or after noon; is the angle of declination from true south, defined as positive when east of south; and is a switch integer for the dial orientation. A partly south-facing dial has an value of +1 ; those partly north-facing, a value of −1 . When such a dial faces south (), this formula reduces to the formula given above for vertical south-facing dials, i.e.

When a sundial is not aligned with a cardinal direction, the substyle of its gnomon is not aligned with the noon hour-line. The angle between the substyle and the noon hour-line is given by the formula[39]

If a vertical sundial faces trUe south Or north ( or respectively), the angle and the substyle is aligned with the noon hour-line.

The height of the gnomon, that is the angle the style makes to the plate, is given by :

The sundials described above have gnomons that are aligned with the Earth's rotational axis and cast their shadow onto a plane. If the plane is neither vertical nor horizontal nor equatorial, the sundial is said to be reclining or inclining.[41] Such a sundial might be located on a south-facing roof, for example. The hour-lines for such a sundial can be calculated by slightly correcting the horizontal formula above[42][43]

where is the desired angle of reclining relative to the local vertical, L is the sundial's geographical latitude, is the angle between a given hour-line and the noon hour-line (which always points due north) on the plane, and t is the number of hours before or after noon. For example, the angle of the 3pm hour-line would equal the arctangent of cos( L + R ) , since tan 45° = 1 . When R = 0° (in other words, a south-facing vertical dial), we obtain the vertical dial formula above.

Some authors use a more specific nomenclature to describe the orientation of the shadow-receiving plane. If the plane's face points downwards towards the ground, it is said to be proclining or inclining, whereas a dial is said to be reclining when the dial face is pointing away from the ground. Many authors also often refer to reclined, proclined and inclined sundials in general as inclined sundials. It is also common in the latter case to measure the angle of inclination relative to the horizontal plane on the sun side of the dial. In such texts, since the hour angle formula will often be seen written as :

The angle between the gnomon style and the dial plate, B, in this type of sundial is :

or :

Some sundials both decline and recline, in that their shadow-receiving plane is not oriented with a cardinal direction (such as true north or true south) and is neither horizontal nor vertical nor equatorial. For example, such a sundial might be found on a roof that was not oriented in a cardinal direction.

The formulae describing the spacing of the hour-lines on such dials are rather more complicated than those for simpler dials.

There are various solution approaches, including some using the methods of rotation matrices, and some making a 3D model of the reclined-declined plane and its vertical declined counterpart plane, extracting the geometrical relationships between the hour angle components on both these planes and then reducing the trigonometric algebra.[44]

One system of formulas for Reclining-Declining sundials: (as stated by Fennewick)[45]

The angle between the noon hour-line and another hour-line is given by the formula below. Note that advances counterclockwise with respect to the zero hour angle for those dials that are partly south-facing and clockwise for those that are north-facing.

within the parameter ranges : and

Or, if preferring to use inclination angle, rather than the reclination, where :

within the parameter ranges : and

Here is the sundial's geographical latitude; is the orientation switch integer; t is the time in hours before or after noon; and and are the angles of reclination and declination, respectively. Note that is measured with reference to the vertical. It is positive when the dial leans back towards the horizon behind the dial and negative when the dial leans forward to the horizon on the Sun's side. Declination angle is defined as positive when moving east of true south. Dials facing fully or partly south have while those partly or fully north-facing have an Since the above expression gives the hour angle as an arctangent function, due consideration must be given to which quadrant of the sundial each hour belongs to before assigning the correct hour angle.

Unlike the simpler vertical declining sundial, this type of dial does not always show hour angles on its sunside face for all declinations between east and west. When a northern hemisphere partly south-facing dial reclines back (i.e. away from the Sun) from the vertical, the gnomon will become co-planar with the dial plate at declinations less than due east or due west. Likewise for southern hemisphere dials that are partly north-facing. Were these dials reclining forward, the range of declination would actually exceed due east and due west. In a similar way, northern hemisphere dials that are partly north-facing and southern hemisphere dials that are south-facing, and which lean forward toward their upward pointing gnomons, will have a similar restriction on the range of declination that is possible for a given reclination value. The critical declination is a geometrical constraint which depends on the value of both the dial's reclination and its latitude :

As with the vertical declined dial, the gnomon's substyle is not aligned with the noon hour-line. The general formula for the angle between the substyle and the noon-line is given by :

The angle between the style and the plate is given by :

Note that for i.e. when the gnomon is coplanar with the dial plate, we have :

i.e. when the critical declination value.[45]

Because of the complexity of the above calculations, using them for the practical purpose of designing a dial of this type is difficult and prone to error. It has been suggested that it is better to locate the hour lines empirically, marking the positions of the shadow of a style on a real sundial at hourly intervals as shown by a clock and adding/deducting that day's equation of time adjustment.[46] See Empirical hour-line marking, above.

The surface receiving the shadow need not be a plane, but can have any shape, provided that the sundial maker is willing to mark the hour-lines. If the style is aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, a spherical shape is convenient since the hour-lines are equally spaced, as they are on the equatorial dial shown here; the sundial is equiangular. This is the principle behind the armillary sphere and the equatorial bow sundial.[47] However, some equiangular sundials – such as the Lambert dial described below – are based on other principles.

In the equatorial bow sundial, the gnomon is a bar, slot or stretched wire parallel to the celestial axis. The face is a semicircle, corresponding to the equator of the sphere, with markings on the inner surface. This pattern, built a couple of meters wide out of temperature-invariant steel invar, was used to keep the trains running on time in France before World War I.[48]

Among the most precise sundials ever made are two equatorial bows constructed of marble found in Yantra mandir.[49] This collection of sundials and other astronomical instruments was built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then-new capital of Jaipur, India between 1727 and 1733. The larger equatorial bow is called the Samrat Yantra (The Supreme Instrument); standing at 27 meters, its shadow moves visibly at 1 mm per second, or roughly a hand's breadth (6 cm) every minute.

Other non-planar surfaces may be used to receive the shadow of the gnomon.

As an elegant alternative, the style (which could be created by a hole or slit in the circumference) may be located on the circumference of a cylinder or sphere, rather than at its central axis of symmetry.

In that case, the hour lines are again spaced equally, but at twice the usual angle, due to the geometrical inscribed angle theorem. This is the basis of some modern sundials, but it was also used in ancient times;[e]

In another variation of the polar-axis-aligned cylindrical, a cylindrical dial could be rendered as a helical ribbon-like surface, with a thin gnomon located either along its center or at its periphery.

Sundials can be designed with a gnomon that is placed in a different position each day throughout the year. In other words, the position of the gnomon relative to the centre of the hour lines varies. The gnomon need not be aligned with the celestial poles and may even be perfectly vertical (the analemmatic dial). These dials, when combined with fixed-gnomon sundials, allow the user to determine true north with no other aid; the two sundials are correctly aligned if and only if they both show the same time. [citation needed]

A universal equinoctial ring dial (sometimes called a ring dial for brevity, although the term is ambiguous), is a portable version of an armillary sundial,[51] or was inspired by the mariner's astrolabe.[52] It was likely invented by William Oughtred around 1600 and became common throughout Europe.[53]

In its simplest form, the style is a thin slit that allows the Sun's rays to fall on the hour-lines of an equatorial ring. As usual, the style is aligned with the Earth's axis; to do this, the user may orient the dial towards true north and suspend the ring dial vertically from the appropriate point on the meridian ring. Such dials may be made self-aligning with the addition of a more complicated central bar, instead of a simple slit-style. These bars are sometimes an addition to a set of Gemma's rings. This bar could pivot about its end points and held a perforated slider that was positioned to the month and day according to a scale scribed on the bar. The time was determined by rotating the bar towards the Sun so that the light shining through the hole fell on the equatorial ring. This forced the user to rotate the instrument, which had the effect of aligning the instrument's vertical ring with the meridian.

When not in use, the equatorial and meridian rings can be folded together into a small disk.

In 1610, Edward Wright created the sea ring, which mounted a universal ring dial over a magnetic compass. This permitted mariners to determine the time and magnetic variation in a single step.[54]

Analemmatic sundials are a type of horizontal sundial that has a vertical gnomon and hour markers positioned in an elliptical pattern. There are no hour lines on the dial and the time of day is read on the ellipse. The gnomon is not fixed and must change position daily to accurately indicate time of day. Analemmatic sundials are sometimes designed with a human as the gnomon. Human gnomon analemmatic sundials are not practical at lower latitudes where a human shadow is quite short during the summer months. A 66 inch tall person casts a 4 inch shadow at 27° latitude on the summer solstice.[55]

The Foster-Lambert dial is another movable-gnomon sundial.[56] In contrast to the elliptical analemmatic dial, the Lambert dial is circular with evenly spaced hour lines, making it an equiangular sundial, similar to the equatorial, spherical, cylindrical and conical dials described above. The gnomon of a Foster-Lambert dial is neither vertical nor aligned with the Earth's rotational axis; rather, it is tilted northwards by an angle α = 45° - (Φ/2), where Φ is the geographical latitude. Thus, a Foster-Lambert dial located at latitude 40° would have a gnomon tilted away from vertical by 25° in a northerly direction. To read the correct time, the gnomon must also be moved northwards by a distance

where R is the radius of the Foster-Lambert dial and δ again indicates the Sun's declination for that time of year.

Altitude dials measure the height of the Sun in the sky, rather than directly measuring its hour-angle about the Earth's axis. They are not oriented towards true north, but rather towards the Sun and generally held vertically. The Sun's elevation is indicated by the position of a nodus, either the shadow-tip of a gnomon, or a spot of light.

In altitude dials, the time is read from where the nodus falls on a set of hour-curves that vary with the time of year. Many such altitude-dials' construction is calculation-intensive, as also the case with many azimuth dials. But the capuchin dials (described below) are constructed and used graphically.

Altitude dials' disadvantages:

Since the Sun's altitude is the same at times equally spaced about noon (e.g., 9am and 3pm), the user had to know whether it was morning or afternoon. At, say, 3:00 pm, that is not a problem. But when the dial indicates a time 15 minutes from noon, the user likely will not have a way of distinguishing 11:45 from 12:15.

Additionally, altitude dials are less accurate near noon, because the sun's altitude is not changing rapidly then.

Many of these dials are portable and simple to use. As is often the case with other sundials, many altitude dials are designed for only one latitude. But the capuchin dial (described below) has a version that's adjustable for latitude.[57]

Mayall & Mayall (1994), p. 169 describe the Universal Capuchin sundial.

The length of a human shadow (or of any vertical object) can be used to measure the sun's elevation and, thence, the time.[58] The Venerable Bede gave a table for estimating the time from the length of one's shadow in feet, on the assumption that a monk's height is six times the length of his foot. Such shadow lengths will vary with the geographical latitude and with the time of year. For example, the shadow length at noon is short in summer months, and long in winter months.

Chaucer evokes this method a few times in his Canterbury Tales, as in his Parson's Tale.[f]

An equivalent type of sundial using a vertical rod of fixed length is known as a backstaff dial.

A shepherd's dial – also known as a shepherd's column dial,[59][60] pillar dial, cylinder dial or chilindre – is a portable cylindrical sundial with a knife-like gnomon that juts out perpendicularly.[61] It is normally dangled from a rope or string so the cylinder is vertical. The gnomon can be twisted to be above a month or day indication on the face of the cylinder. This corrects the sundial for the equation of time. The entire sundial is then twisted on its string so that the gnomon aims toward the Sun, while the cylinder remains vertical. The tip of the shadow indicates the time on the cylinder. The hour curves inscribed on the cylinder permit one to read the time. Shepherd's dials are sometimes hollow, so that the gnomon can fold within when not in use.

The shepherd's dial is evoked in Henry VI, Part 3,[g]among other works of literature.[h]

The cylindrical shepherd's dial can be unrolled into a flat plate. In one simple version,[64] the front and back of the plate each have three columns, corresponding to pairs of months with roughly the same solar declination (June:July, May:August, April:September, March:October, February:November, and January:December). The top of each column has a hole for inserting the shadow-casting gnomon, a peg. Often only two times are marked on the column below, one for noon and the other for mid-morning / mid-afternoon.

Timesticks, clock spear,[59] or shepherds' time stick,[59] are based on the same principles as dials.[59][60] The time stick is carved with eight vertical time scales for a different period of the year, each bearing a time scale calculated according to the relative amount of daylight during the different months of the year. Any reading depends not only on the time of day but also on the latitude and time of year.[60]A peg gnomon is inserted at the top in the appropriate hole or face for the season of the year, and turned to the Sun so that the shadow falls directly down the scale. Its end displays the time.[59]

In a ring dial (also known as an Aquitaine or a perforated ring dial), the ring is hung vertically and oriented sideways towards the sun.[65] A beam of light passes through a small hole in the ring and falls on hour-curves that are inscribed on the inside of the ring. To adjust for the equation of time, the hole is usually on a loose ring within the ring so that the hole can be adjusted to reflect the current month.

Card dials are another form of altitude dial.[66] A card is aligned edge-on with the sun and tilted so that a ray of light passes through an aperture onto a specified spot, thus determining the sun's altitude. A weighted string hangs vertically downwards from a hole in the card, and carries a bead or knot. The position of the bead on the hour-lines of the card gives the time. In more sophisticated versions such as the Capuchin dial, there is only one set of hour-lines, i.e., the hour lines do not vary with the seasons. Instead, the position of the hole from which the weighted string hangs is varied according to the season.

The Capuchin sundials are constructed and used graphically, as opposed the direct hour-angle measurements of horizontal or equatorial dials; or the calculated hour angle lines of some altitude and azimuth dials.

In addition to the ordinary Capuchin dial, there is a universal Capuchin dial, adjustable for latitude.

A navicula de Venetiis or "little ship of Venice" was an altitude dial used to tell time and which was shaped like a little ship. The cursor (with a plumb line attached) was slid up / down the mast to the correct latitude. The user then sighted the Sun through the pair of sighting holes at either end of the "ship's deck". The plumb line then marked what hour of the day it was.[citation needed]

Another type of sundial follows the motion of a single point of light or shadow, which may be called the nodus. For example, the sundial may follow the sharp tip of a gnomon's shadow, e.g., the shadow-tip of a vertical obelisk (e.g., the Solarium Augusti) or the tip of the horizontal marker in a shepherd's dial. Alternatively, sunlight may be allowed to pass through a small hole or reflected from a small (e.g., coin-sized) circular mirror, forming a small spot of light whose position may be followed. In such cases, the rays of light trace out a cone over the course of a day; when the rays fall on a surface, the path followed is the intersection of the cone with that surface. Most commonly, the receiving surface is a geometrical plane, so that the path of the shadow-tip or light-spot (called declination line) traces out a conic section such as a hyperbola or an ellipse. The collection of hyperbolae was called a pelekonon (axe) by the Greeks, because it resembles a double-bladed ax, narrow in the center (near the noonline) and flaring out at the ends (early morning and late evening hours).

There is a simple verification of hyperbolic declination lines on a sundial: the distance from the origin to the equinox line should be equal to harmonic mean of distances from the origin to summer and winter solstice lines.[67]

Nodus-based sundials may use a small hole or mirror to isolate a single ray of light; the former are sometimes called aperture dials. The oldest example is perhaps the antiborean sundial (antiboreum), a spherical nodus-based sundial that faces true north; a ray of sunlight enters from the south through a small hole located at the sphere's pole and falls on the hour and date lines inscribed within the sphere, which resemble lines of longitude and latitude, respectively, on a globe.[68]

Isaac Newton developed a convenient and inexpensive sundial, in which a small mirror is placed on the sill of a south-facing window.[69] The mirror acts like a nodus, casting a single spot of light on the ceiling. Depending on the geographical latitude and time of year, the light-spot follows a conic section, such as the hyperbolae of the pelikonon. If the mirror is parallel to the Earth's equator, and the ceiling is horizontal, then the resulting angles are those of a conventional horizontal sundial. Using the ceiling as a sundial surface exploits unused space, and the dial may be large enough to be very accurate.

Sundials are sometimes combined into multiple dials. If two or more dials that operate on different principles — such as an analemmatic dial and a horizontal or vertical dial — are combined, the resulting multiple dial becomes self-aligning, most of the time. Both dials need to output both time and declination. In other words, the direction of true north need not be determined; the dials are oriented correctly when they read the same time and declination. However, the most common forms combine dials are based on the same principle and the analemmatic does not normally output the declination of the sun, thus are not self-aligning.[70]

The diptych consisted of two small flat faces, joined by a hinge.[71] Diptychs usually folded into little flat boxes suitable for a pocket. The gnomon was a string between the two faces. When the string was tight, the two faces formed both a vertical and horizontal sundial. These were made of white ivory, inlaid with black lacquer markings. The gnomons were black braided silk, linen or hemp string. With a knot or bead on the string as a nodus, and the correct markings, a diptych (really any sundial large enough) can keep a calendar well-enough to plant crops. A common error describes the diptych dial as self-aligning. This is not correct for diptych dials consisting of a horizontal and vertical dial using a string gnomon between faces, no matter the orientation of the dial faces. Since the string gnomon is continuous, the shadows must meet at the hinge; hence, any orientation of the dial will show the same time on both dials.[72]

A common type of multiple dial has sundials on every face of a Platonic solid (regular polyhedron), usually a cube.[73]

Extremely ornate sundials can be composed in this way, by applying a sundial to every surface of a solid object.

In some cases, the sundials are formed as hollows in a solid object, e.g., a cylindrical hollow aligned with the Earth's rotational axis (in which the edges play the role of styles) or a spherical hollow in the ancient tradition of the hemisphaerium or the antiboreum. (See the History section above.) In some cases, these multiface dials are small enough to sit on a desk, whereas in others, they are large stone monuments.

A Polyhedral's dial faces can be designed to give the time for different time-zones simultaneously. Examples include the Scottish sundial of the 17th and 18th centuries, which was often an extremely complex shape of polyhedral, and even convex faces.

Prismatic dials are a special case of polar dials, in which the sharp edges of a prism of a concave polygon serve as the styles and the sides of the prism receive the shadow.[74] Examples include a three-dimensional cross or star of David on gravestones.

The Benoy dial was invented by Walter Gordon Benoy of Collingham, Nottinghamshire, England. Whereas a gnomon casts a sheet of shadow, his invention creates an equivalent sheet of light by allowing the Sun's rays through a thin slit, reflecting them from a long, slim mirror (usually half-cylindrical), or focusing them through a cylindrical lens. Examples of Benoy dials can be found in the United Kingdom at:[75]

.jpg/440px-Stainless_steel_bifilar_sundial_(dial).jpg)

Invented by the German mathematician Hugo Michnik in 1922, the bifilar sundial has two non-intersecting threads parallel to the dial. Usually the second thread is orthogonal to the first.[77]The intersection of the two threads' shadows gives the local solar time.

A digital sundial indicates the current time with numerals formed by the sunlight striking it. Sundials of this type are installed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich and in the Sundial Park in Genk (Belgium), and a small version is available commercially. There is a patent for this type of sundial.[78]

The globe dial is a sphere aligned with the Earth's rotational axis, and equipped with a spherical vane.[79] Similar to sundials with a fixed axial style, a globe dial determines the time from the Sun's azimuthal angle in its apparent rotation about the earth. This angle can be determined by rotating the vane to give the smallest shadow.

The simplest sundials do not give the hours, but rather note the exact moment of 12:00 noon.[80] In centuries past, such dials were used to set mechanical clocks, which were sometimes so inaccurate as to lose or gain significant time in a single day. The simplest noon-marks have a shadow that passes a mark. Then, an almanac can translate from local solar time and date to civil time. The civil time is used to set the clock. Some noon-marks include a figure-eight that embodies the equation of time, so that no almanac is needed.

In some U.S. colonial-era houses, a noon-mark might be carved into a floor or windowsill.[81] Such marks indicate local noon, and provide a simple and accurate time reference for households to set their clocks. Some Asian countries had post offices set their clocks from a precision noon-mark. These in turn provided the times for the rest of the society. The typical noon-mark sundial was a lens set above an analemmatic plate. The plate has an engraved figure-eight shape, which corresponds to the equation of time (described above) versus the solar declination. When the edge of the Sun's image touches the part of the shape for the current month, this indicates that it is 12:00 noon.

A sundial cannon, sometimes called a 'meridian cannon', is a specialized sundial that is designed to create an 'audible noonmark', by automatically igniting a quantity of gunpowder at noon. These were novelties rather than precision sundials, sometimes installed in parks in Europe mainly in the late 18th or early 19th centuries. They typically consist of a horizontal sundial, which has in addition to a gnomon a suitably mounted lens, set to focus the rays of the sun at exactly noon on the firing pan of a miniature cannon loaded with gunpowder (but no ball). To function properly the position and angle of the lens must be adjusted seasonally.[citation needed]

.jpg/440px-Sun_beam_approaching_the_meridional_line_in_the_Duomo_(Milan).jpg)

A horizontal line aligned on a meridian with a gnomon facing the noon-sun is termed a meridian line and does not indicate the time, but instead the day of the year. Historically they were used to accurately determine the length of the solar year. Examples are the Bianchini meridian line in Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome, and the Cassini line in San Petronio Basilica at Bologna.[82]

The association of sundials with time has inspired their designers over the centuries to display mottoes as part of the design. Often these cast the device in the role of memento mori, inviting the observer to reflect on the transience of the world and the inevitability of death. "Do not kill time, for it will surely kill thee." Other mottoes are more whimsical: "I count only the sunny hours," and "I am a sundial and I make a botch / of what is done far better by a watch." Collections of sundial mottoes have often been published through the centuries.[citation needed]

If a horizontal-plate sundial is made for the latitude in which it is being used, and if it is mounted with its plate horizontal and its gnomon pointing to the celestial pole that is above the horizon, then it shows the correct time in apparent solar time. Conversely, if the directions of the cardinal points are initially unknown, but the sundial is aligned so it shows the correct apparent solar time as calculated from the reading of a clock, its gnomon shows the direction of True north or south, allowing the sundial to be used as a compass. The sundial can be placed on a horizontal surface, and rotated about a vertical axis until it shows the correct time. The gnomon will then be pointing to the north, in the northern hemisphere, or to the south in the southern hemisphere. This method is much more accurate than using a watch as a compass (see Cardinal direction#Watch face) and can be used in places where the magnetic declination is large, making a magnetic compass unreliable. An alternative method uses two sundials of different designs. (See #Multiple dials, above.) The dials are attached to and aligned with each other, and are oriented so they show the same time. This allows the directions of the cardinal points and the apparent solar time to be determined simultaneously, without requiring a clock.[citation needed]

This ugly plastic 'non-dial' does nothing at all except display the 'designer's ignorance and persuade the general public that 'real' sundials don't work.