La 101.ª División Aerotransportada (Asalto Aéreo) ("Screaming Eagles") [2] es una división de infantería de asalto aéreo del Ejército de los Estados Unidos que se especializa en operaciones de asalto aéreo . [3] Puede planificar, coordinar y ejecutar operaciones de asalto aéreo del tamaño de un batallón para apoderarse del terreno. Estas operaciones pueden ser realizadas por equipos móviles que cubren grandes distancias, luchan tras las líneas enemigas y trabajan en entornos austeros con infraestructura limitada o degradada. [4] [5] [6] Estuvo activa, por ejemplo, en operaciones de defensa interna extranjera y antiterrorismo en Irak, en Afganistán en 2015-2016, [7] [8] [9] y en Siria, como parte de la Operación Inherent Resolve en 2018-2021.

Fundada en 1918, la 101.ª División Aerotransportada se constituyó por primera vez como una unidad aerotransportada en 1942. [10] Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , ganó renombre por su papel en la Operación Overlord (los desembarcos del Día D y los desembarcos aéreos el 6 de junio de 1944, en Normandía , Francia ); la Operación Market Garden ; la liberación de los Países Bajos ; y su acción durante la Batalla de las Ardenas alrededor de la ciudad de Bastogne , Bélgica . Durante la Guerra de Vietnam , la 101.ª División Aerotransportada luchó en varias campañas y batallas importantes, incluida la Batalla de Hamburger Hill en mayo de 1969. A mediados de 1968, la división fue reorganizada y rediseñada como una división aeromóvil y en 1974, la división fue nuevamente rediseñada como una división de asalto aéreo. Los títulos reflejan el cambio de la división de aviones a helicópteros como el método principal de entrega de tropas al combate.

En el apogeo de la Guerra contra el Terror , la 101.ª División Aerotransportada (Asalto Aéreo) tenía más de 200 aviones. [ cita requerida ] Esto se redujo a poco más de 100 aviones con la inactivación de la 159.ª Brigada de Aviación de Combate en 2015. [4] En 2019, los informes de los medios sugirieron que el Ejército estaba trabajando para restaurar las capacidades de aviación de la 101.ª para que pueda volver a levantar una brigada entera en una operación de asalto aéreo. [4]

La sede del 101.º es Fort Campbell , Kentucky . Muchos de sus miembros son graduados de la Escuela de Asalto Aéreo del Ejército de los EE. UU. , que comparte ubicación con la división. La escuela es conocida por ser uno de los cursos más difíciles del Ejército; solo alrededor de la mitad de quienes la comienzan se gradúan. [11]

El ex secretario de Defensa de los EE. UU. , Robert Gates , se refirió a los Screaming Eagles como "la punta de la lanza" , [12] y la más potente y tácticamente móvil de las divisiones del Ejército de los EE. UU. por el general Edward C. Meyer , entonces jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército . [13]

La 101.ª División se constituyó en el Ejército Nacional el 23 de julio de 1918. Se organizó en Camp Shelby , Mississippi , el 2 de noviembre de 1918, y fue comandada por el general de brigada Roy Hoffman . [14] La Primera Guerra Mundial terminó nueve días después, y la división fue desmovilizada el 11 de diciembre de 1918. [15]

En 1921, el cuartel general de la división se reconstituyó en la Reserva Organizada , asignada al Área del Sexto Cuerpo y asignada al XVI Cuerpo , y luego asignada al estado de Wisconsin . El cuartel general de la división se organizó el 10 de septiembre de 1921 en la Sala 412 del Edificio Federal en Milwaukee , trasladándose en julio de 1922 al Edificio Pereles, donde permaneció hasta que se activó para la Segunda Guerra Mundial. La estación de movilización y entrenamiento designada para la división fue Camp Custer , Michigan , donde ocurrieron gran parte de las actividades anuales de entrenamiento de la división en los años de entreguerras. El cuartel general y el personal generalmente se entrenaban con el personal de la 12.ª Brigada de Infantería, ya sea en Camp Custer o Fort Sheridan, Illinois , mientras que los regimientos de infantería se entrenaban principalmente con el 2.º Regimiento de Infantería en Camp Custer. Las unidades de tropas especiales, artillería, ingenieros, aviación, médicas y de intendencia se entrenaban en varios puestos en las Áreas del Sexto y Séptimo Cuerpo. Además, el personal de la división también llevó a cabo los campamentos de entrenamiento militar para ciudadanos en el área de origen de la división como una forma de entrenamiento anual. Las principales escuelas de "alimentación" de la división para los tenientes de reserva recién comisionados fueron la Universidad de Wisconsin , el Ripon College y el St. Norbert College .

El personal de la división participó a veces en los ejercicios de puesto de mando del Sexto Cuerpo de Área y del Segundo Ejército con otras unidades del Ejército regular, la Guardia Nacional y la Reserva Organizada, pero la división no participó como unidad en las diversas Maniobras del Sexto Cuerpo de Área y las maniobras del Segundo Ejército de 1937, 1940 y 1941, debido a la falta de personal alistado y equipo. En cambio, los oficiales y algunos reservistas alistados fueron asignados a unidades del Ejército regular y la Guardia Nacional para llenar los puestos vacantes, y a algunos oficiales se les asignaron funciones como árbitros o personal de apoyo. [15] [16]

Fue en esta época cuando la mascota "Screaming Eagle" pasó a asociarse con la división, como sucesora de las tradiciones de los regimientos voluntarios de Wisconsin de la Guerra Civil estadounidense . [17]

El 30 de julio de 1942, las Fuerzas Terrestres del Ejército ordenaron la activación de dos divisiones aerotransportadas para el 15 de agosto de 1942. La 82.ª División, una división de la Reserva Organizada que entró en servicio militar activo en marzo de 1942, recibió la orden de proporcionar cuadros a la 101.ª División, la otra división seleccionada para el proyecto, para todos los elementos excepto la infantería paracaidista. Como parte de la reorganización de la 101.ª División como división aerotransportada, la unidad se disolvió en la Reserva Organizada el 15 de agosto de 1942 y se reconstituyó y reactivó en el Ejército de los Estados Unidos . [15] El 19 de agosto de 1942, su primer comandante, el mayor general William C. Lee , leyó la Orden General Número 5: [19]

La 101 División Aerotransportada, activada el 16 de agosto de 1942 en Camp Claiborne , Luisiana , no tiene historia, pero tiene un encuentro con el destino.

Debido a la naturaleza de nuestro armamento y a las tácticas en las que nos perfeccionaremos, seremos llamados a llevar a cabo operaciones de importancia militar de gran alcance y habitualmente entraremos en acción cuando la necesidad sea inmediata y extrema. Permítanme llamar su atención sobre el hecho de que nuestra insignia es la gran águila estadounidense. Este es un emblema apropiado para una división que aplastará a sus enemigos cayendo sobre ellos como un rayo desde el cielo.

La historia que haremos, el registro de grandes logros que esperamos escribir en los anales del Ejército y del pueblo estadounidenses, depende total y completamente de los hombres de esta división. Cada individuo, cada oficial y cada soldado raso, debe, por lo tanto, considerarse a sí mismo como una parte necesaria de un instrumento complejo y poderoso para vencer a los enemigos de la nación. Cada uno, en su propio trabajo, debe darse cuenta de que no es sólo un medio, sino un medio indispensable para alcanzar el objetivo de la victoria. Por lo tanto, no es exagerado decir que el futuro mismo, en cuyo molde esperamos tener nuestra parte, está en manos de los soldados de la 101 División Aerotransportada. [20]

Los exploradores de la 101.ª División Aerotransportada encabezaron el camino en el Día D en el lanzamiento nocturno antes de la invasión. Partieron de la base de la RAF North Witham , donde se habían entrenado con la 82.ª División Aerotransportada . Estos lanzamientos nocturnos causaron muchos problemas a los planeadores. Muchos se estrellaron y se perdió equipo y personal. [21]

Los objetivos de la 101 División Aerotransportada eran asegurar las cuatro salidas de la calzada detrás de Utah Beach entre Saint-Martin-de-Varreville y Pouppeville para asegurar la ruta de salida de la 4.ª División de Infantería desde la playa más tarde esa mañana. [22] Los otros objetivos incluían destruir una batería de artillería costera alemana en Saint-Martin-de-Varreville, capturar edificios cercanos en Mézières que se creía que se usaban como cuarteles y un puesto de mando para la batería de artillería, capturar la esclusa del río Douve en La Barquette (frente a Carentan ), capturar dos puentes peatonales que cruzan el Douve en La Porte frente a Brévands , destruir los puentes de la carretera sobre el Douve en Saint-Côme-du-Mont y asegurar el valle del río Douve. Su misión secundaria era proteger el flanco sur del VII Cuerpo . Destruyeron dos puentes a lo largo de la carretera de Carentan y un puente ferroviario justo al oeste de ella. Obtuvieron el control de las esclusas de La Barquette y establecieron una cabeza de puente sobre el Douve, que estaba situada al noreste de Carentan. [22]

En el proceso, las unidades también interrumpieron las comunicaciones alemanas, establecieron bloqueos para obstaculizar el movimiento de refuerzos alemanes, establecieron una línea defensiva entre la cabeza de playa y Valognes , despejaron el área de las zonas de lanzamiento hasta el límite de la unidad en Les Forges y se unieron con la 82 División Aerotransportada.

Los paracaidistas de la 101 División Aerotransportada saltaron entre las 00:48 y la 01:40 hora de verano británica del 6 de junio. La primera oleada, que se dirigía a la Zona de Desembarco A (la más septentrional), no se vio sorprendida por el banco de nubes y mantuvo la formación, pero errores de navegación y la falta de señal Eureka provocaron el primer error [ aclaración necesaria ] . Aunque el 2.º Batallón del 502.º Regimiento de Infantería Paracaidista fue lanzado como una unidad compacta, saltó en la zona de desembarco equivocada, mientras que su comandante, el teniente coronel Steve A. Chappuis, descendió prácticamente solo en la zona de desembarco correcta. Chappuis y su paracaidista capturaron la batería costera poco después de reunirse y descubrieron que ya había sido desmantelada tras un ataque aéreo.

La mayor parte del resto del 502.º (70 de los 80 paracaidistas) se lanzó de forma desorganizada alrededor de la zona de lanzamiento improvisada que habían establecido los exploradores cerca de la playa. Los comandantes de batallón del 1.º y 3.º Batallones, el teniente coronel Patrick J. Cassidy (1/502) y el teniente coronel Robert G. Cole (3/502), se hicieron cargo de pequeños grupos y cumplieron todas sus misiones del Día D. El grupo de Cassidy tomó Saint Martin-de-Varreville a las 06:30, envió una patrulla al mando del sargento Harrison C. Summers para apoderarse del objetivo "XYZ", un cuartel en Mésières, y estableció una delgada línea de defensa desde Foucarville hasta Beuzeville . El grupo de Cole se trasladó durante la noche desde cerca de Sainte-Mère-Église hasta la batería de Varreville, luego continuó y capturó la Salida 3 a las 07:30. Mantuvieron la posición durante la mañana hasta que fueron relevados por tropas que se dirigían hacia el interior desde Utah Beach. Ambos comandantes encontraron la Salida 4 cubierta por el fuego de artillería alemán y Cassidy recomendó a la 4.ª División de Infantería que no utilizara la salida.

La artillería paracaidista de la división no tuvo tan buena suerte. Su lanzamiento fue uno de los peores de la operación, ya que perdió todos los obuses menos uno y arrojó todas las cargas menos dos de las 54 a una distancia de entre cuatro y veinte millas (32 km) al norte, donde la mayoría terminó sufriendo bajas.

La segunda oleada, asignada para lanzar al 506.º Regimiento de Infantería Paracaidista (PIR) en la Zona de Lanzamiento C a 1 milla (1,6 km) al oeste de Sainte Marie-du-Mont , fue dispersada gravemente por las nubes, y luego sometida a un intenso fuego antiaéreo durante 10 millas (16 km). Tres de los 81 C-47 se perdieron antes o durante el salto. Uno, pilotado por el primer teniente Marvin F. Muir del 439.º Grupo de Transporte de Tropas , se incendió. Muir mantuvo el avión firme mientras el mando saltaba, luego murió cuando el avión se estrelló inmediatamente después, por lo que se le concedió la Cruz de Servicio Distinguido . A pesar de la oposición, el 1.er Batallón del 506.º (la reserva original de la división) fue lanzado con precisión en la DZ C, aterrizando dos tercios de sus mandos y al comandante del regimiento, el coronel Robert F. Sink, en o a una milla de la zona de lanzamiento.

La mayor parte del 2.º Batallón había saltado demasiado al oeste, cerca de Sainte-Mère-Église. Finalmente se reunieron cerca de Foucarville, en el extremo norte del área objetivo de la 101.ª División Aerotransportada. A media tarde, se abrió paso hasta la aldea de Le Grand Chemin, cerca de la calzada de Houdienville, pero descubrió que la 4.ª División ya había tomado la salida horas antes. El 3.er Batallón de la 501.ª División de Infantería de Marina , dirigido por el teniente coronel Julian J. Ewell (3/501), también asignado para saltar a la DZ C, estaba más disperso, pero se hizo cargo de la misión de asegurar las salidas. Un equipo ad hoc del tamaño de una compañía que incluía al comandante de división, el mayor general Maxwell D. Taylor, llegó a la salida de Pouppeville a las 06:00. [23] Después de una batalla de seis horas con elementos del 1058.º Regimiento de Granaderos alemán para limpiar la casa, el grupo aseguró la salida poco antes de que las tropas de la 4.ª División llegaran para unirse.

La tercera oleada también se enfrentó a un intenso fuego antiaéreo y perdió seis aviones. Los portaaviones lograron lanzar sus misiles con precisión, colocando 94 de sus 132 proyectiles en la zona de lanzamiento o cerca de ella, pero parte de la zona de lanzamiento estaba cubierta por fuego de ametralladoras y morteros alemanes registrados previamente que infligieron muchas bajas antes de que muchas tropas pudieran salir de sus paracaídas. Entre los muertos se encontraban dos de los tres comandantes del batallón y el oficial ejecutivo del 3/506. [notas 2]

El comandante del batallón superviviente, el teniente coronel Robert A. Ballard, reunió a 250 soldados y avanzó hacia Saint Côme-du-Mont para completar su misión de destruir los puentes de la autopista sobre el río Douve. A menos de media milla de su objetivo en Les Droueries fue detenido por elementos del batallón III/1058 Grenadier-Rgt. Otro grupo de 50 hombres, reunidos por el S-3 del regimiento, el mayor Richard J. Allen, atacó la misma zona desde el este en Basse-Addeville, pero también fue inmovilizado.

El comandante del 501.º Regimiento de Infantería de Marina, coronel Howard R. Johnson, reunió a 150 soldados y capturó el objetivo principal, la esclusa de la Barquette, a las 04:00. Después de establecer posiciones defensivas, el coronel Johnson regresó a la zona de defensa y reunió a otros 100 hombres, incluido el grupo de Allen, para reforzar la cabeza de puente. A pesar del apoyo de fuego naval del crucero Quincy , el batallón de Ballard no pudo tomar Saint Côme-du-Mont ni unirse al coronel Johnson. [notas 3]

El oficial S-3 del 3er Batallón 506th PIR, el capitán Charles G. Shettle, formó un pelotón y logró otro objetivo al tomar dos puentes peatonales cerca de la Porte a las 04:30 y cruzar a la orilla este. Cuando se les acabó la munición después de destruir varios emplazamientos de ametralladoras, la pequeña fuerza se retiró a la orilla oeste. Duplicó su tamaño durante la noche cuando llegaron rezagados y rechazaron una sonda alemana a través de los puentes.

Otras dos acciones notables tuvieron lugar cerca de Sainte Marie-du-Mont por unidades del 506.º PIR, ambas implicaron la toma y destrucción de baterías de cañones de 105 mm del III Batallón alemán-191.º Regimiento de Artillería . Durante la mañana, una pequeña patrulla de soldados de la Compañía E del 506.º PIR bajo el mando del (entonces) primer teniente Richard D. Winters abrumó a una fuerza 3 o 4 veces su tamaño y destruyó cuatro cañones en una granja llamada Brécourt Manor , por la que Winters recibió más tarde la Cruz de Servicio Distinguido y las tropas de asalto recibieron las Estrellas de Plata y Bronce. Esto se documentó más tarde en el libro Band of Brothers y la miniserie del mismo nombre .

Alrededor del mediodía, mientras reconocía la zona en jeep , el coronel Sink recibió la noticia de que se había descubierto una segunda batería de cuatro cañones en Holdy, una mansión entre su puesto de mando y Sainte Marie-du-Mont, y los defensores tenían una fuerza de unos 70 paracaidistas inmovilizados. El capitán Lloyd E. Patch (Compañía del Cuartel General 1.º/506.º) y el capitán Knut H. Raudstein (Compañía C 506.º PIR) [notas 4] condujeron a 70 tropas adicionales a Holdy y rodearon la posición. La fuerza combinada continuó entonces para apoderarse de Sainte Marie-du-Mont. Un pelotón del 502.º PIR, que quedó para mantener la batería, destruyó tres de los cuatro cañones antes de que el coronel Sink pudiera enviar cuatro jeeps para guardarlos para el uso de la 101.ª.

Al final del Día D, el general Taylor y el comandante de artillería de la división, el general de brigada Anthony C. McAuliffe, regresaron de su incursión en Pouppeville. Taylor tenía el control de aproximadamente 2.500 de sus 6.600 hombres, la mayoría de los cuales estaban en las proximidades del puesto de mando del 506.º en Culoville, con la delgada línea de defensa al oeste de Saint Germain-du-Varreville, o la reserva de la división en Blosville. Dos puentes aéreos con planeadores habían traído escasos refuerzos y habían resultado en la muerte de su ayudante del comandante de división (ADC), el general de brigada Don F. Pratt , con el cuello roto en el impacto. El 327.º Regimiento de Infantería de Planeadores había cruzado la playa de Utah, pero solo su tercer batallón (1.º Batallón del 401.º GIR) se había presentado.

La 101 División Aerotransportada había cumplido su misión más importante de asegurar las salidas de la playa, pero tenía un control tenue de las posiciones cercanas al río Douve, por donde los alemanes aún podían mover unidades blindadas. Los tres grupos agrupados allí tenían un contacto tenue entre sí, pero ninguno con el resto de la división. La escasez de equipos de radio causada por las pérdidas durante los lanzamientos exacerbó sus problemas de control. Taylor hizo de la destrucción de los puentes de Douve la máxima prioridad de la división y delegó la tarea a Sink, quien dio órdenes para que el 1.er Batallón de la 401.ª Infantería de Planeadores liderara tres batallones hacia el sur a la mañana siguiente.

A medida que las tropas regulares avanzaban desde la costa y reforzaban las posiciones de los paracaidistas, muchos fueron relevados y enviados a la retaguardia para organizarse para la siguiente gran operación de paracaidistas. Los primeros elementos de la división regresaron a Southampton, Inglaterra, el 12 de julio de 1944 en presencia del Secretario de Guerra Henry L. Stimson , según los documentos privados del Teniente General John C. H. Lee , comandante general de la Zona de Comunicaciones , ETO, que recibió la visita del Secretario.

El 17 de septiembre de 1944, la 101.ª División Aerotransportada pasó a formar parte del XVIII Cuerpo Aerotransportado , bajo el mando del mayor general Matthew Ridgway , parte del Primer Ejército Aerotransportado Aliado , comandado por el teniente general Lewis H. Brereton . La división participó en la Operación Market Garden (17-25 de septiembre de 1944), una operación militar aliada fallida bajo el mando del mariscal de campo Bernard Montgomery , comandante del 21.º Grupo de Ejércitos anglocanadiense , para capturar puentes holandeses sobre el Rin. Se libró en los Países Bajos y es la mayor operación aerotransportada de cualquier guerra. [24]

El plan, tal como lo describió Montgomery, requería que las fuerzas aerotransportadas tomaran varios puentes en la carretera 69 sobre el río Mosa y dos brazos del Rin (el Waal y el Bajo Rin ), así como varios canales y afluentes más pequeños . Cruzar estos puentes permitiría a las unidades blindadas británicas flanquear la Línea Sigfrido , avanzar hacia el norte de Alemania y rodear el Ruhr , el corazón industrial de Alemania, poniendo así fin a la guerra. Esto significó el uso a gran escala de las fuerzas aerotransportadas aliadas , incluidas las divisiones aerotransportadas 82 y 101, junto con la 1. a División Aerotransportada británica .

La operación fue inicialmente exitosa. La 82.ª y la 101.ª División capturaron varios puentes entre Eindhoven y Nimega . La 101.ª encontró poca resistencia y capturó la mayoría de sus objetivos iniciales a fines del 17 de septiembre. Sin embargo, la demolición del objetivo principal de la división, un puente sobre el canal Wilhelmina en Son , retrasó la captura del puente de la carretera principal sobre el Mosa hasta el 20 de septiembre. Ante la pérdida del puente en Son, la 101.ª intentó sin éxito capturar un puente similar a unos pocos kilómetros de distancia en Best , pero encontró el acceso bloqueado. Otras unidades continuaron moviéndose hacia el sur y finalmente alcanzaron el extremo norte de Eindhoven.

A las 06:00 horas del 18 de septiembre, los guardias irlandeses de la División Blindada de la Guardia Británica reanudaron el avance mientras se enfrentaban a la decidida resistencia de la infantería y los tanques alemanes. [25] : p71 Alrededor del mediodía, la 101.ª División Aerotransportada se encontró con las unidades de reconocimiento líderes del XXX Cuerpo británico . A las 16:00 horas, el contacto por radio alertó a la fuerza principal de que el puente Son había sido destruido y solicitó que se trajera un puente Bailey de reemplazo. Al anochecer, la División Blindada de la Guardia se había establecido en el área de Eindhoven [26], sin embargo, las columnas de transporte estaban atascadas en las calles abarrotadas de la ciudad y fueron sometidas a bombardeos aéreos alemanes durante la noche. Los ingenieros del XXX Cuerpo, apoyados por prisioneros de guerra alemanes, construyeron un puente Bailey clase 40 en 10 horas a través del Canal Wilhelmina. [25] : p72 El sector más largo de la autopista asegurada por la 101.ª División Aerotransportada más tarde se conocería como "la autopista del infierno".

La 101.ª División llegó entonces al saliente de Nimega y relevó a la 43.ª División Wessex británica para defenderse de la contraofensiva alemana a principios de octubre.

La Ofensiva de las Ardenas (16 de diciembre de 1944 - 25 de enero de 1945) fue una importante ofensiva alemana lanzada hacia el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial a través de la región boscosa de las montañas Ardenas de Bélgica. El objetivo planificado de Alemania para estas operaciones era dividir la línea aliada británica y estadounidense en dos, capturando Amberes , Bélgica en el proceso, y luego proceder a rodear y destruir a todo el 21.º Grupo de Ejércitos británico y todas las unidades del 12.º Grupo de Ejércitos estadounidense al norte del avance alemán, obligando a los aliados occidentales a negociar un tratado de paz a favor de las potencias del Eje como resultado. [27] Para llegar a Amberes antes de que los aliados pudieran reagruparse y hacer valer su poder aéreo superior, las fuerzas mecanizadas alemanas tuvieron que apoderarse de todas las carreteras principales a través del este de Bélgica. Debido a que las siete carreteras principales de las Ardenas convergían en la pequeña ciudad de Bastogne , el control de su cruce era vital para el éxito o el fracaso del ataque alemán.

A pesar de varias señales notables en las semanas anteriores al ataque, la Ofensiva de las Ardenas logró una sorpresa prácticamente total. Al final del segundo día de batalla, se hizo evidente que la 28.ª División de Infantería estaba al borde del colapso. El mayor general Troy H. Middleton , comandante del VIII Cuerpo , ordenó que parte de su reserva blindada, el Comando de Combate B de la 10.ª División Blindada, se dirigiera a Bastogne. [notas 5] Mientras tanto, el general Eisenhower ordenó que avanzara la reserva del SHAEF , compuesta por la 82.ª y la 101.ª División Aerotransportada, que estaban estacionadas en Reims .

Ambas divisiones fueron alertadas la tarde del 17 de diciembre y, al no tener transporte orgánico, comenzaron a organizar camiones para avanzar, ya que las condiciones climáticas no eran las adecuadas para un lanzamiento en paracaídas. La 82.ª, que llevaba más tiempo en reserva y, por lo tanto, estaba mejor equipada, se puso en marcha primero. La 101.ª abandonó el campamento Mourmelon la tarde del 18 de diciembre, con la orden de marcha de la artillería de la división, los trenes de la división, el 501.º PIR, el 506.º PIR , el 502.º PIR y el 327.º de Infantería de Planeadores . Gran parte del convoy se realizó de noche, bajo llovizna y aguanieve, utilizando faros a pesar de la amenaza de un ataque aéreo para acelerar el movimiento, y en un momento la columna combinada se extendió desde Bouillon , Bélgica, de regreso a Reims.

La 101.ª División Aerotransportada fue enviada a Bastogne, situada a 172 km de distancia en una meseta de 446 m de altura , mientras que la 82.ª División Aerotransportada tomó posiciones más al norte para bloquear el avance crítico del Kampfgruppe Peiper hacia Werbomont, Bélgica. El 705.º Batallón de Destructores de Tanques , en reserva a sesenta millas al norte, recibió órdenes de ir a Bastogne para proporcionar apoyo antitanque a la 101.ª División Aerotransportada sin blindados el día 18 y llegó tarde la noche siguiente. Los primeros elementos de la 501.ª División Aerotransportada entraron en el área de reunión de la división a cuatro millas al oeste de Bastogne poco después de la medianoche del 19 de diciembre, y a las 09:00 había llegado toda la división.

El 21 de diciembre, las fuerzas alemanas habían rodeado Bastogne, que estaba defendida tanto por la 101.ª División Aerotransportada como por el Comando de Combate B de la 10.ª División Blindada. Las condiciones dentro del perímetro eran duras: la mayoría de los suministros médicos y el personal médico habían sido capturados el 19 de diciembre. [28] El CCB de la 10.ª División Blindada, severamente debilitado por las pérdidas al retrasar el avance alemán, formó una "brigada de bomberos" móvil de 40 tanques ligeros y medianos (incluidos los supervivientes del CCR de la 9.ª División Blindada , que había sido destruido mientras retrasaba a los alemanes, y ocho tanques de reemplazo encontrados sin asignar en Bastogne). Tres batallones de artillería, incluido el 969.º Batallón de Artillería de Campaña , totalmente negro , fueron requisados por la 101.ª y formaron un grupo de artillería temporal. Cada una de ellas contaba con doce obuses de 155 mm, lo que proporcionaba a la división una gran potencia de fuego en todas las direcciones, limitada únicamente por su limitado suministro de munición (el 22 de diciembre, la munición de artillería se había limitado a 10 proyectiles por cañón por día). Sin embargo, el tiempo mejoró al día siguiente y se lanzaron suministros (principalmente municiones) durante cuatro de los cinco días siguientes.

A pesar de varios ataques alemanes decididos, el perímetro se mantuvo. El comandante alemán, el teniente general Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz , [29] solicitó la rendición de Bastogne. [30] Cuando se lo comunicaron al general Anthony McAuliffe , ahora comandante en funciones de la 101.ª División, comentó: "¡Qué locura!". Después de pasar a otros asuntos urgentes, su personal le recordó que debería haber una respuesta a la demanda alemana. Un oficial (Harry WO Kinnard, entonces teniente coronel) recomendó que la respuesta de McAuliffe sería "difícil de superar". Por lo tanto, McAuliffe escribió en el papel entregado a los alemanes: "¡Qué locura!". Esa respuesta tenía que ser explicada, tanto a los alemanes como a los aliados no estadounidenses. [notas 6]

Las dos divisiones panzer del XLVII Cuerpo Panzer avanzaron desde Bastogne después del 21 de diciembre, dejando solo un regimiento de granaderos panzer de la Panzer-Lehr-Division para ayudar a la 26.ª División Volksgrenadier en su intento de capturar el cruce de caminos. La 26.ª División Panzer recibió refuerzos de blindados y granaderos panzer adicionales en Nochebuena para prepararse para su asalto final, que se llevaría a cabo el día de Navidad. Debido a que carecía de suficientes blindados y tropas y la 26.ª División Panzer estaba casi agotada, el XLVII Cuerpo Panzer concentró el asalto en varias posiciones individuales en el lado oeste del perímetro en secuencia en lugar de lanzar un ataque simultáneo por todos los lados. El asalto, a pesar del éxito inicial de los tanques alemanes al penetrar la línea estadounidense, fue derrotado y prácticamente todos los tanques alemanes involucrados fueron destruidos. Al día siguiente, 26 de diciembre, la 4.ª División Blindada , la punta de lanza de la fuerza de socorro del Tercer Ejército de los Estados Unidos del general George S. Patton , atravesó las líneas alemanas y abrió un corredor hacia Bastogne, poniendo fin al asedio. La división recibió el apodo de "Los maltrechos bastardos del bastión de Bastogne".

Con el cerco roto, los hombres de la 101.ª División Aerotransportada esperaban ser relevados, pero recibieron órdenes de reanudar la ofensiva. La 506.ª División atacó hacia el norte y recuperó Recogne el 9 de enero de 1945, el Bois des Corbeaux ( Bosque de Corbeaux ), a la derecha de la Compañía Easy, el 10 de enero, y Foy el 13 de enero. La 327.ª División atacó hacia Bourcy, al noreste de Bastogne, el 13 de enero y encontró una tenaz resistencia. La 101.ª División Aerotransportada se enfrentó a la élite del ejército alemán, que incluía unidades como la 1.ª División Panzer SS Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler , la Führerbegleitbrigade , la 12.ª División Panzer SS Hitlerjugend y la 9.ª División Panzer SS Hohenstaufen . [31] La 506.ª División retomó Noville el 15 de enero y Rachamps al día siguiente. El 502.º reforzó al 327.º y los dos regimientos capturaron Bourcy el 17 de enero, haciendo retroceder a los alemanes hasta su punto de avance el día en que la división había llegado a Bastogne. Al día siguiente, la 101.ª División Aerotransportada fue relevada. [32]

En abril de 1945, la 101.ª División se trasladó a Renania y finalmente llegó a los Alpes bávaros. Mientras la 101.ª División avanzaba hacia el sur de Alemania, liberó Kaufering IV, uno de los campos del complejo de Kaufering . Kaufering IV había sido designado como el campo de enfermos donde se enviaba a los prisioneros que ya no podían trabajar. Durante la epidemia de tifus de 1945 en Alemania, los prisioneros de Kaufering con tifus fueron enviados allí para morir. Kaufering IV estaba ubicado cerca de la ciudad de Hurlach, que la 12.ª División Blindada ocupó el 27 de abril, y la 101.ª llegó al día siguiente. Los soldados encontraron más de 500 reclusos muertos y el ejército ordenó a los habitantes de la localidad que enterraran a los muertos. [33]

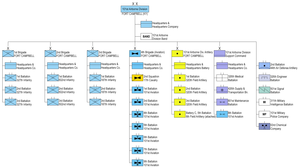

La división estaba compuesta por las siguientes unidades: [34]

Unidades de paracaidistas adjuntas:

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la división y sus miembros recibieron las siguientes condecoraciones: [36]

On 1 August 1945, the 501st PIR was moved to France, while the rest of the division was based around Zell am See and Kaprun in the Austrian Alps. Some units within the division began training for redeployment to the Pacific Theatre of War, but the war ended before they were needed. The division was inactivated 30 November 1945. For their efforts during World War II, the 101st Airborne Division was awarded four campaign streamers and two Presidential Unit Citations.

The 101st was distinguished partly by its tactical helmet insignia. Card suits (diamonds, spades, hearts, and clubs) on each side of the helmet denoted the regiment to which a soldier belonged. The only exception was the 187th which was added to the division later. Divisional headquarters and support units were denoted by use of a square and divisional artillery by a circle. Tick marks at 3, 6, and 9 o'clock indicated to which battalion the individual belonged, while the tick mark at 12 o'clock indicated a headquarters or headquarters company assignment.[37]

The 101st Airborne was allotted to the Regular Army in June 1948[15] and reactivated as a training unit at Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky the following July, only to be inactivated the next year.[15] It was reactivated in 1950 following the outbreak of the Korean War, again to serve as a Training Center at Camp Breckenridge until inactivated in December 1953. During this time it included the 53rd Airborne Infantry Regiment.

It was reactivated again in May 1954 at Fort Jackson, South Carolina[15] and in March 1956, the 101st was transferred, less personnel and equipment, to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, to be reorganized as a combat division. Using the personnel and equipment of the 187th ARCT and the 508th ARCT,[38] the 101st was reactivated as the first "pentomic" division with five battle groups in place of its World War II structure that included regiments and battalions. The reorganization was in place by late April 1957 and the division's battle groups were:

Division artillery consisted of the following units:

Other supporting units were also assigned.

The "Little Rock Nine" were a group of African-American students who were enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in September 1957, as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in the historic Brown v. Board of Education case. Elements of the division's 1st Airborne Battle Group, 327th Infantry were ordered to Little Rock by President Eisenhower to escort the students into the formerly segregated school during the crisis. The division was under the command of Major General Edwin Walker, who was committed to protecting the black students.[39] The troops were deployed from September until Thanksgiving 1957, when Task Force 153rd Infantry, (federalized Arkansas Army National Guard) which had also been on duty at the school since 24 September, assumed the responsibility.

In 1958 the US Army formed the Strategic Army Corps consisting of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions and the 1st and 4th Infantry Divisions with a mission of rapid deployment on short notice.

On 29 July 1965, the 1st Brigade deployed to II Corps, South Vietnam with the following units:

From 1965 to 1967, the 1st Brigade operated independently as sort of a fire brigade and earned the reputation as being called the "Nomads of Vietnam." They fought in every area of South Vietnam from the Demilitarized Zone up north all the way down the Central Highlands.[41] In May 1967 the 1st Brigade operated as part of Task Force Oregon.[40]

Within the United States, the 101st, along with the 82nd Airborne Division, was sent in to quell the 1967 Detroit riot.

The rest of the 101st was deployed to Vietnam in November 1967 and the 1st Brigade rejoined its parent division.[40] The 101st was deployed in the northern I Corps region, operating against the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) infiltration routes through Laos and the A Shau Valley for most of the war. Notable among these were the Battle of Hamburger Hill in 1969 and Firebase Ripcord in 1970.

During the war, the division's bald eagle patch resulted in the North Vietnamese Army referring to 101st Airborne soldiers as "chicken men."[42]

Tiger Force was the nickname of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit[43] of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought in the Vietnam War.[44] The platoon-sized unit, approximately 45 paratroopers, was founded by Colonel David Hackworth in November 1965 to "outguerrilla the guerrillas".[45] Tiger Force (Recon) 1/327th was a highly decorated small unit in Vietnam, and paid for its reputation with heavy casualties.[46] In October 1968, Tiger Force's parent battalion was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which included a mention of Tiger Force's service at Đắk Tô in June 1966.[47]

The unit was accused of committing multiple war crimes.[48] Investigators concluded that many of the war crimes indeed took place.[49] Despite this, the Army decided not to pursue any prosecutions.[50] By the end of the war, Tiger Force had killed approximately 1,000 enemy soldiers.[51]

In 1971, elements of the division supported Operation Lam Son 719, the South Vietnamese invasion of southern Laos, but only aviation units actually entered Laos.

The division began withdrawing from South Vietnam on 15 May 1971 with the departure of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry.[52]: F-1–8 Most major units of the Division had redeployed by January 1972.[52]: F-1–22

In the seven years that all or part of the division served in Vietnam it suffered 4,011 killed and 18,259 wounded in action.[53] The division, during this time, participated in 12 separate campaigns and 17 of the division's Medal of Honor recipients are from this period of time – all this giving the 101st Airborne Division a combat record unmatched by any other division.[41]

In 1968, the 101st took on the structure and equipment of an airmobile division. Following its return from Vietnam, the division was rebuilt with one brigade (3d) and supporting elements on jump status, using the assets of what had been the 173rd Airborne Brigade. The remaining two brigades and supporting units were organized as airmobile. With the exception of certain specialized units, such as the pathfinders and parachute riggers, in early 1974 the Army terminated jump status for the division. Concurrently the 101st introduced the Airmobile Badge (renamed later that year as the Air Assault Badge), the design of which was based on the Glider Badge of World War II. Initially the badge was only authorized for wear while assigned to the division, but in 1978 the Army authorized it for service-wide wear. Soldiers continued to wear the garrison cap with glider patch, bloused boots, and their specific unit's airborne background trimming behind their Air Assault or Parachute Badge, as had division paratroopers before them. A blue beret was authorized for the division in March or April 1974 and worn until revoked at the end of 1979.[54][55]

The division also was authorized to wear a full color (white eagle) shoulder patch insignia instead of the subdued green eagle shoulder patch that was worn as a combat patch by soldiers who fought with the 101st in Vietnam. While serving with the 101st, it was also acceptable to wear a non-subdued patch as a combat patch, a distinction shared with the 1st and 5th Infantry divisions.[citation needed]

In the late 1970s, the division maintained one battalion on a rotating basis as the division ready force (DRF). The force was in place to respond to alerts for action anywhere in the world. After alert notification, troopers of the "hot" platoon/company, would be airborne, "wheels-up" within 30 minutes as the first responding unit. All other companies of the battalion would follow within one hour. Within 24 hours there would be one brigade deployed to the affected area, with the remainder of the division deploying as needed.

In September 1980, 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry, 2nd Brigade, took part in Operation Bright Star '80, an exercise deployment to Egypt. In 1984, the command group formed a full-time team, the "Screaming Eagles", Command Parachute Demonstration Team.[56] However the team traces its history to the late 1950s, during the infancy of precision free fall.

On 12 December 1985, a civilian aircraft, Arrow Air Flight 1285, chartered to transport some of the division from peacekeeping duty with the Multinational Force and Observers on the Sinai Peninsula to Kentucky, crashed just a short distance from Gander International Airport, Gander, Newfoundland. All eight air crew members and 248 US servicemen died, most were from the 3d Battalion, 502d Infantry. Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board investigators were unable to determine the exact sequence of events which led to the accident, but determined that the probable cause of the crash was the aircraft's unexpectedly high drag and reduced lift condition, most likely due to ice contamination on the wings' leading edges and upper surfaces, as well as underestimated onboard weight.[57] A minority report stated that the accident could have been caused by an onboard explosion of unknown origin prior to impact.[58][59] At the time it was 17th most disastrous aviation accident in terms of fatalities. President Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy traveled to Fort Campbell to comfort grieving family members.

On 8 March 1988, two U.S. Army Blackhawk helicopters assigned to the 101st Aviation Brigade collided while on a night training mission at Fort Campbell. All 17 soldiers aboard were killed.[60] The dead included four helicopter crewmen and 13 members of the 502d Infantry Regiment. The Army's accident investigation attributed the crash to pilot error, aircraft design, and the limited field of view afforded pilots using night vision goggles (NVGs).[61] Numerous improvements have been made in NVG technology since the accident occurred.[62]

In 1974, the 101st Airborne was reorganized as an air assault division. The foundation of modern-day air assault operations was laid by the World War Two era German Fallschirmjäger, Brandenburgers, and the 22nd Air Landing Division glider borne paras.[63][64] In 1941 the U.S. Army quickly adopted this concept of offensive operations initially utilizing wooden gliders before the development of helicopters.[65] Air Assault operations consist of highly mobile teams covering extensive distances and engaging enemy forces behind enemy lines and often by surprise, as they are usually masked by darkness.[66]: 63

The 101st Airborne had earned a place in the U.S. Army's AirLand Battle doctrine.[66]: 63 This doctrine is based on belief that initiative, depth, agility, and synchronization successfully complete a mission.[66]: 63 First all soldiers are encouraged to take the initiative to seize and exploit opportunities to gain advantages over the enemy. Second, commanders are urged to utilize the entire depth of the battlefield and strike at rear targets that support frontline enemy troops. Third, agility requires commanders to strike the enemy quickly where most vulnerable and to respond to the enemy's strengths. Fourth, synchronization calls for the commander to maximize available combined arms firepower for critical targets to achieve the greatest effect.[66]: 63

At the end of the Cold War the division was organized as follows:

On 17 January 1991, the 101st Aviation Regiment fired the first shots of the war when eight AH-64 helicopters successfully destroyed two Iraqi early warning radar sites.[66]: 85 In February 1991, the 101st once again had its "Rendezvous with Destiny" in Iraq during the combat air assault into enemy territory. The 101st Airborne Division struck 155 miles (249 km) behind enemy lines.[66]: 85 It was the deepest air assault operation in history.[102]

Approximately 400 helicopters transported 2,000 soldiers into Iraq, where they destroyed Iraqi columns trying to flee westward and prevented the escape of Iraqi forces.[103] The Screaming Eagles would travel an additional 50–60 miles (80–97 km) into Iraq.[66]: 85 By nightfall, the 101st had cut off Highway 8, which was a vital supply line running between Basra and the Iraqi forces.[66]: 85 The 101st lost 16 soldiers in action during the 100-hour war and captured thousands of the enemy.

The division has supported humanitarian relief efforts in Rwanda and Somalia, then later supplied peacekeepers to Haiti and Bosnia.

From February through August 2000, 3rd Brigade 1/187 deployed to Kosovo for peacekeeping operations as part of Task Force Falcon in support of Operation Joint Guardian.

In August 2000, the 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, as well as some elements from the 502nd Infantry Regiment, helped secure the peace in Kosovo and support the October elections for the formation of the new Kosovo government. They were replaced in February 2001 with 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment along with 2nd Brigade HQ and elements of 3rd Battalion.

In September and October 2000, the 3rd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, helped fight fires on the Bitterroot National Forest in Montana. Designated Task Force Battle Force and commanded by Lt. Col. Jon S. Lehr, the battalion fought fires throughout the surrounding areas of their Valley Complex near Darby, Montana.[104]

The 101st Airborne (Air Assault) Division brigade performed counterinsurgency operations within Afghanistan, consisting mostly of raids, ambushes and patrolling. The 101st also performed combat air assaults throughout the operation.[102]

The 2nd Brigade, "Strike", built around the 502nd Infantry, was largely deployed to Kosovo on peacekeeping operations, with some elements of 3rd Battalion, 502nd, deploying after 9/11 as a security element in the U.S. CENTCOM AOR with the Fort Campbell-based 5th Special Forces Group. They had been positioned in Jordan providing security for 5th SF Group's exercise prior to 9/11.

The division quickly deployed its 3rd Brigade, the 187th Infantry's Rakkasans, as the first conventional unit to fight as part of Operation Enduring Freedom.[105]

After an intense period of combat in rugged Shoh-I-Khot Mountains of eastern Afghanistan during Operation Anaconda with elements of the 10th Mountain Division, the Rakkasans redeployed to Fort Campbell only to find the 101st awaiting another deployment order. In 2008, the 101st 4th BCT Red and White "Currahee" including the 1st and the 2nd Battalions, 506th Infantry were deployed to Afghanistan. Elements of 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment participated in joint operations with U.S. Army Special Forces particularly in the Northern province of Kapisa in the outpost Forward Operating Base (FOB) Kutchsbach. Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment performed joint operations with 5th Special Forces Group and 20th Special Forces Group in 2011. The 101st Combat Aviation Brigade deployed to Afghanistan as Task Force Destiny in early 2008 to Bagram Air Base. 159th Combat Aviation Brigade deployed as Task Force Thunder for 12 months in early 2009, and again in early 2011.[106]

In March 2010, the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade deployed again to Afghanistan as Task Force Destiny to Kandahar Airfield to be the aviation asset in southern Afghanistan.

In 2003, Major General David H. Petraeus ("Eagle 6") led the Screaming Eagles to war during the 2003 invasion of Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom). General Petraeus led the division into Iraq saying, "Guidons, Guidons. This is Eagle 6. The 101st Airborne Division's next Rendezvous with Destiny is North to Baghdad. Op-Ord Desert Eagle 2 is now in effect. Godspeed. Air Assault. Out."[107]

The division was in V Corps, providing support to the 3rd Infantry Division by clearing Iraqi strongpoints which that division had bypassed. 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry (3rd Brigade) was attached to 3rd Infantry Division and was the main effort in clearing Saddam International Airport. The division then served as part of the occupation forces of Iraq, using the city of Mosul as their primary base of operations. 1st and 2d Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment (1st Brigade) oversaw the remote airfield Qayarrah West 30 miles (48 km) south of Mosul. The 502d Infantry Regiment (2d Brigade) and 3d Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment were responsible for Mosul itself while the 187th Infantry Regiment (3d Brigade) controlled Tal Afar just west of Mosul. The 101st Airborne also participated in the Battle of Karbala. The city had been bypassed during the advance on Baghdad, leaving American units to clear it in two days of street fighting against Iraqi irregular forces. The 101st Airborne was supported by the 2nd Battalion, 70th Armor Regiment with Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry Regiment, 1st Armored Division.[108] The 3d Battalion, 502d Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division was awarded a Valorous Unit Award for their combat performance.

On the afternoon of 22 July 2003, troops of the 101st Airborne 3/327th Infantry HQ and C-Company, aided by U.S. Special Forces killed Qusay Hussein, his 14-year-old son Mustapha, and his older brother Uday, during a raid on a home in Mosul.[109] After Task Force 121 members were wounded, the 3/327th Infantry surrounded and fired on the house with a TOW missile, Mark 19 Automatic Grenade Launcher, M2 50 Caliber Machine guns and small arms. After about four hours of battle (the whole operation lasted six hours), the soldiers entered the house and found four dead, including the two brothers and their bodyguard. There were reports that Qusay's 14-year-old son Mustapha was the fourth body found. Brig. Gen. Frank Helmick, the assistant commander of 101st Airborne, commented that all occupants of the house died during the fierce gun battle before U.S. troops entered.[110]

Once replaced by the first operational Stryker Brigade, the 101st was withdrawn in early 2004 for rest and refit. As part of the Army's modular transformation, the existing infantry brigades, artillery brigade, and aviation brigades were transformed. The Army also activated the 4th Brigade Combat Team, which includes the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 506th Infantry Regiment and subordinate units. Both battalions were part of the 101st in Vietnam but saw their colors inactivated during an Army-wide reflagging of combat battalions in the 1980s.

As of December 2007, 143 members of the division have died while on service in Iraq.[111][needs update]

The division's second deployment to Iraq began in the late summer of 2005. The division headquarters replaced the 42d Infantry Division, which had been directing security operations as the headquarters for Task Force Liberty. Renamed Task Force Band of Brothers, the 101st assumed responsibility on 1 November 2005 for four provinces in north central Iraq: Salah ad Din, As Sulymaniyah.

During the second deployment, 2d and 4th Brigades of the 101st Airborne Division were assigned to conduct security operations under the command of Task Force Baghdad, led initially by 3d Infantry Division, which was replaced by 4th Infantry Division. The 1st Battalion of the 506th Infantry (4th Brigade) was separated from the division and served with the Marines in Ramadi, in the Al Anbar province. 3d Brigade was assigned to Salah ad Din and Bayji sectors and 1st Brigade was assigned to the overall Kirkuk province which included Hawijah.

Task Force Band of Brothers' primary mission during its second deployment to Iraq was the training of Iraqi security forces. When the 101st returned to Iraq, there were no Iraqi units capable of assuming the lead for operations against Iraqi and foreign terrorists. As the division concluded its tour, 33 battalions were in the lead for security in assigned areas, and two of four Iraq divisions in northern Iraq were commanding and controlling subordinate units.

Simultaneously with training Iraqi soldiers and their leaders, 101st soldiers conducted numerous security operations against terrorist cells operating in the division's assigned, six-province area of operations. Operation Swarmer was the largest air assault operation conducted in Iraq since 22 April 2003. 1st Brigade conducted Operation Scorpion with Iraqi units near Kirkuk.

Developing other aspects of Iraqi society also figured in 101st operations in Iraq. Division commander Major General Thomas Turner hosted the first governors' conference for the six provinces in the division's area of operations, as well as the neighboring province of Erbil.[112]

While the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Brigade Combat Teams were deployed to Iraq 2007–2008, the division headquarters, 4th Brigade Combat Team, the 101st Sustainment Brigade, and the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade followed by the 159th Combat Aviation Brigade were deployed to Afghanistan for one-year tours falling within the 2007–09 window.

The Division Headquarters, 101st Combat Aviation Brigade, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 2d Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, and 4th Brigade Combat Team, and the 101st Sustainment Brigade deployed to Afghanistan in 2010. This is the first time since returning from Iraq in 2006 where all four infantry brigades (plus one CAB, SUSBDE) have served in the same combat theater.

On 15 September 2010, the 101st Airborne began a major operation known as Operation Dragon Strike. The aim of the operation was to reclaim the strategic southern province of Kandahar, which was the birthplace of the Taliban movement. The area where the operation took place has been dubbed "The Heart of Darkness" by Coalition troops.[113]

By the end of December 2010, the operation's main objectives had been accomplished. The majority of Taliban forces in Kandahar had withdrawn from the province,[114] and much of their leadership was said to have been fractured.[115]

As of 5 June 2011, 131 soldiers had been killed during this deployment, the highest death toll to the 101st Airborne in any single deployment since the Vietnam War.[116]

The 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment conducted a major combat operation in Barawala Kalay Valley, Kunar Province, Afghanistan in late March–April 2011. It is known as the Battle of Barawala Kalay Valley. It was an operation to close down the Taliban supply route through the Barawala Kalay Valley and to remove the forces of Taliban warlord Qari Ziaur Rahman from the Barwala Kalay Valley. The 2nd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment would suffer 6 killed and 7 wounded during combat operations. It would inflict over 100 casualties on the Taliban and successfully close down the Taliban supply route.[117] ABC News correspondent Mike Boettcher was on scene and he called it the fiercest fighting he has ever seen in his 30 years of being in war zones.[118]

Since the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom 166 101st Airborne soldiers have died while serving in Iraq.[119]

In 2014, the 101st Airborne Division Headquarters deployed to west Africa to help contain the spread of Ebola, as part of Operation United Assistance.

Earlier in April 2014, 4th Brigade Combat Team had been inactivated as part of the Army's 2020 BCT restructuring program.[120]

In 2015, 5th Special Forces Group held five training sessions with the 1st Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division.[121] The classes covered communications and the operation of all-terrain vehicles. There was also a training session on the operation of TOW missiles.[121] Prior to these sessions training between U.S. Special Forces and U.S. conventional forces had been uncommon.[121]

The U.S. Army sent 500 soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) to Iraq and Kuwait in early 2016 to advise and assist Iraqi Security Forces.[7]

In the recent conflicts the 101st Airborne has been increasingly involved conducting special operations especially the training and development of other states' military and security forces and counter-terrorism operations.[122] This is known in the special operations community as foreign internal defense and counter-terrorism. It was announced 14 January 2016 that soldiers of the 101st Airborne would be assigned rotations in Iraq, to train members of the Iraqi ground forces in preparation for action against the Islamic State.[122] Defense Secretary Ash Carter told the 101st Airborne that "The Iraqi and Peshmerga forces you will train, advise and assist have proven their determination, their resiliency, and increasingly, their capability.[122] But they need you to continue building on that success, preparing them for the fight today and the long hard fight for their future. They need your skill. They need your experience."[122]

In Spring 2016, 200 soldiers from 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment replaced a unit of the 26th MEU at Firebase Bell; they used M777 155mm howitzers to provide support to Iraqi forces attacking IS-occupied villages between Makhmour and Mosul.[123] 500 soldiers from the division's headquarters, including its commander Major General Gary J. Volesky, and about 1,300 soldiers from 2nd Brigade Combat Team also deployed to Iraq in the Spring.[124]

On 26 June 2016, it was announced that Iraq had successfully taken back full control of Fallujah from the Islamic State of Iraq (ISIS).[125] Iraqi ground troops have been under the direction of the 101st Airborne since early 2016.[122] In summer 2016, Stars and Stripes reported that about 400 soldiers from 2nd Brigade Combat Team will deploy to Iraq as part of 11 July 2016 announcement by Defense Secretary Ash Carter of the presidential approved deployment of an additional 560 U.S. troops to Iraq to help establish and run a logistics hub at Qayyarah Airfield West, about 40 miles south Mosul, to support Iraqi and coalition troops in the Battle of Mosul.[124]

On 26 August 2016, an article from the website War is Boring shows a photo of a 101st Airborne Division M777 howitzer crew conducting fire missions during an operation to support Iraqi forces at Kara Soar Base in Iraq on 7 August 2016.[126] The article also confirms that American artillery has been supporting Iraqi forces during its campaign against ISIS.[126]

On 31 August 2016, Clarksville Online reported U.S. soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, Task Force Strike, took charge of a Ranger training program for qualified volunteers from Iraqi security forces at Camp Taji, Iraq. The Ranger training program, led by Company A, 1–502nd, is designed to lay the foundation for an elite Iraqi unit.[127]

On 21 September 2016, an article from The Leaf-Chronicle reported that Battery C, 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division had been successfully conducting artillery raids against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. Battery C is said to have executed hundreds of missions and fired thousands of rounds in support of ISF operations since arriving in theatre in late May.[128]

On 17 October 2016, an article from The Leaf-Chronicle stated that the 101st Airborne was leading a coalition of 19 nations to support the liberation of Mosul from ISIL. Under the direction of the 101st Iraqi forces have taken back a significant amount of geography from the control of ISIS. This included the liberation of Hit, Fallujah, and Qayyarah.[129]

On 3 November 2016, it was reported that U.S. Army combat engineers were seen just west of the Great Zab River about halfway between the Kurdish city of Irbil and Mosul. They were searching for improvised bombs. They were wearing 101st Airborne Division patches. The soldiers said they were not allowed to talk to the media.[130]

On 17 November 2016, sources reported that the 101st Airborne Division was headed home after a nine-month deployment to Iraq. Over the course of nine months, soldiers from the 101st Airborne helped train the Iraqi government's security forces. They taught marksmanship, basic battlefield medical care and ways to detect and disarm improvised explosive devices.[131] The division helped authorize 6,900 strikes, meant to destroy ISIS hideouts and staging areas.[131] The 101st Airborne played a significant role in the liberation of several Iraqi cities during this deployment.[131]

On 6 September 2016, the U.S. Army announced it will deploy about 1,400 soldiers from 3rd Brigade Combat Team to Afghanistan in fall 2016, in support of "Operation Freedom's Sentinel" – the U.S. counter-terrorism operation against the remnants of al-Qaeda, ISIS–K and other terror groups,[132] as part of the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021). Senior leadership referred to the 3rd Brigade Combat Team as being exceptional.[133] Brig. Gen. Scott Brower stated that the Rakkasans are trained, well-led, and prepared to accomplish any mission given to them.[133] During this deployment three Soldiers from 1/187, 3rd Brigade Combat Team died as a result of an insider attack by an Afghan Soldier.[134]

In May 2016, the brigade, deployed to advise and assist, train and equip Iraqi security forces to fight the Islamic State of Iraq. The 2nd Brigade also conducted precision surface-to-surface fires and supported a multitude of intelligence and logistical operations for coalition and Iraqi forces. They also provided base security throughout more than 12 areas of operations. The Brigade also aided in the clearance of ISIS from Fallujah, the near elimination of suicide attacks in Baghdad, and the introduction of improved tactics that liberated more than 100 towns and villages. The 2nd Brigade also played a significant role in the liberation of Mosul.[135]

In mid-April 2017, it was reported that 40 soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division were deployed to Somalia on 2 April 2017 to improve the capabilities of the Somali Army in combating Islamist militants. AFRICOM stated that the troops will focus on bolstering the Somali army's logistics capabilities; an AFRICOM spokesman said that "This mission is not associated with teaching counterextremism tactics" and that the Somali government requested the training.[136]

In June 2022, Headquarters, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) and the 2nd Brigade Combat Team rotated in to the U.S. Army V Corps' mission to reinforce NATO's eastern flank and engage in multinational exercises with partners across the European continent in order to reassure allies and deter further Russian aggression during its invasion of Ukraine. The 101st soldiers deploying to Mihail Kogălniceanu in June did not represent additional U.S. forces in Europe, but are taking the place of soldiers assigned to 82nd Airborne Division Headquarters and the 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team of the 82nd Airborne Division. In all, approximately 4700 soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division are scheduled to deploy to locations across Europe.[137]

On 30 July 2022, the Headquarters, 101st Airborne Division and 2nd Brigade Combat Team uncased their colors and conducted an air assault demonstration at the 57th Air Base "Mihail Kogălniceanu" together with the 9th Mechanized Brigade of the Romanian Armed Forces. The event was attended by Maj. Gen. Joseph P. McGee and the Prime Minister of Romania, Nicolae Ciucă.[138][139]

The 2nd Brigade Combat Team was replaced by the 1st Brigade Combat Team on 31 March 2023. During its 9 months of deployment, the 2nd Brigade conducted training exercises with multiple NATO partners and allies across the continent.[140] On 5 April, the mission authority was transferred from the 101st Division to the 10th Mountain Division. The battle flag of the 101st was also decorated with the National Order of Faithful Service during the ceremony.[141][142] On 24 November, the 3rd Brigade Combat Team "Rakkasan" replaced the 1st Brigade Combat Team following a transfer of authority ceremony.[143]

The 101st Airborne Division consists of a division headquarters and headquarters battalion, three infantry brigade combat teams, a division artillery, a combat aviation brigade, a sustainment brigade.

Page said records captured during the war showed the North Vietnamese Army warned troops to be cautious when encountering the 'chicken men,' referring to the division's bald eagle patch.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)On episode 25 of the All American Legacy Podcast, we mention the blue beret of the 101st Airborne Division in the 1970s. Well, here is the proof.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)