El torneo de baloncesto masculino de la División I de la NCAA , conocido como March Madness , es un torneo de eliminación simple que se juega en los Estados Unidos para determinar el campeón nacional de baloncesto universitario masculino de la División I en la Asociación Nacional de Atletismo Universitario . El torneo, que se juega principalmente durante el mes de marzo, consta de 68 equipos y se celebró por primera vez en 1939. Conocido por sus victorias sorpresa sobre los equipos favoritos, se ha convertido en uno de los eventos deportivos anuales más importantes de los EE. UU.

El formato de 68 equipos se adoptó en 2011 ; se había mantenido prácticamente sin cambios desde 1985, cuando se amplió a 64 equipos. Antes de eso, el tamaño del torneo variaba desde tan solo 8 hasta 53. El campo estaba restringido a los campeones de la conferencia hasta que se extendieron las ofertas generales en 1975 y los equipos no fueron sembrados completamente hasta 1979. En 2020 , el torneo se canceló por primera vez debido a la pandemia de COVID-19 ; en la temporada siguiente, el torneo se disputó completamente en el estado de Indiana como medida de precaución.

Hasta la fecha, treinta y siete escuelas diferentes han ganado el torneo. UCLA es la que más títulos ha ganado, con 11 campeonatos; su entrenador, John Wooden, tiene la mayor cantidad de títulos de cualquier entrenador, con 10. La Universidad de Kentucky (UK) tiene ocho campeonatos, la Universidad de Connecticut (UConn) y la Universidad de Carolina del Norte tienen seis campeonatos, la Universidad de Duke y la Universidad de Indiana tienen cinco campeonatos, la Universidad de Kansas (KU) tiene cuatro campeonatos y la Universidad de Villanova tiene tres campeonatos. Siete programas están empatados con dos campeonatos nacionales y 23 equipos han ganado el campeonato nacional una vez.

Todos los partidos del torneo son transmitidos por CBS , TBS , TNT y truTV bajo el nombre de programa NCAA March Madness . Con un contrato hasta 2032, Paramount Global y Warner Bros. Discovery pagan $891 millones anuales por los derechos de transmisión. La NCAA distribuye los ingresos a los equipos participantes en función de lo lejos que avanzan, lo que proporciona una financiación significativa para el atletismo universitario. El torneo se ha convertido en parte de la cultura popular estadounidense a través de concursos de llaves que otorgan dinero y otros premios por predecir correctamente los resultados de la mayor cantidad de juegos. En 2023, Sports Illustrated informó que se estima que se completan entre 60 y 100 millones de llaves cada año.

El primer torneo se celebró en 1939 y lo ganó Oregon . Fue idea del entrenador de Ohio State, Harold Olsen . La Asociación Nacional de Entrenadores de Baloncesto organizó el primer torneo para la NCAA.

De 1939 a 1950, el torneo de la NCAA consistió en ocho equipos, cada uno seleccionado de un distrito geográfico. Varias conferencias se consideraron parte de cada distrito, como las conferencias Missouri Valley y Big Seven en un distrito y las conferencias Southern y Southeastern en otro, lo que a menudo llevó a que los equipos mejor clasificados quedaran fuera del torneo. El problema llegó a un punto crítico en 1950 , cuando la NCAA sugirió que Kentucky, que ocupaba el tercer puesto, y North Carolina State, que ocupaba el quinto, compitieran en un partido de playoffs por una oferta, pero Kentucky se negó, creyendo que se les debía dar la oferta como el equipo mejor clasificado. En respuesta, la NCAA duplicó el campo a 16 en 1951 , agregando dos distritos adicionales y seis lugares para equipos generales. Las conferencias todavía solo podían tener un equipo en el torneo, pero ahora se podían incluir varias conferencias del mismo distrito geográfico a través de ofertas generales. Este desarrollo ayudó a la NCAA a competir con el Torneo Nacional de Invitación por prestigio. [2]

En el formato de ocho equipos, el torneo se dividió en las regiones Este y Oeste, y los campeones se enfrentaron en el partido por el campeonato nacional. Las dos primeras rondas de cada región se llevaron a cabo en el mismo sitio y el campeonato nacional y, a partir de 1946 , el partido de consolación se llevó a cabo una semana después. Algunos años, el sitio del campeonato nacional fue el mismo sitio que un campeonato regional y en otros años un nuevo sitio. Con la expansión a 16 equipos, el torneo mantuvo el formato original de las semifinales nacionales siendo las finales regionales en 1951. Para el torneo de 1952 , hubo cuatro regiones llamadas Este-1, Este-2, Oeste-1, Oeste-2, todas jugadas en sitios separados. Los campeones regionales se enfrentaron para las semifinales nacionales y el campeonato en una ubicación separada una semana después, estableciendo el formato con dos rondas finales del torneo (aunque el nombre "Final Four" no se usaría en la marca hasta la década de 1980).

El torneo de 1953 se amplió para incluir 22 equipos y agregó una quinta ronda, con diez equipos recibiendo un pase directo a las semifinales regionales. El número de equipos fluctuaría de 22 a 25 equipos durante las siguientes dos décadas, pero el número de rondas se mantuvo igual. La denominación de doble región se mantuvo hasta 1956 , cuando las regiones se denominaron Este, Medio Oeste, Oeste y Lejano Oeste. En 1957 , las regiones se denominaron Este, Medio Oriente, Medio Oeste y Oeste, que se mantuvieron hasta 1985. Las regiones se emparejaron en las semifinales nacionales en función de sus ubicaciones geográficas, con las dos regiones orientales enfrentándose en una semifinal y las dos regiones occidentales enfrentándose en la otra semifinal.

A partir de 1946 , se celebró un partido por el tercer puesto a nivel nacional antes del partido por el campeonato. A partir de 1939, se jugaron partidos regionales por el tercer puesto en el Oeste y a partir de 1941 en el Este . A pesar de la expansión en 1951 , todavía había solo dos regiones, cada una con un partido por el tercer puesto. El torneo de 1952 tuvo cuatro regiones, cada una con un partido por el tercer puesto.

Esta era del torneo se caracterizó por la competencia con el Torneo Nacional por Invitación . Fundado por la Asociación Metropolitana de Escritores de Baloncesto un año antes del torneo de la NCAA, el NIT se llevó a cabo íntegramente en la ciudad de Nueva York en el Madison Square Garden. Debido a que Nueva York era el centro de la prensa en los Estados Unidos, el NIT a menudo recibió más cobertura que el torneo de la NCAA en los primeros años. Además, los buenos equipos a menudo eran excluidos del torneo de la NCAA porque cada conferencia solo podía tener una oferta e incluso los campeones de la conferencia eran excluidos debido al sistema de 8 distritos antes de 1950. Los equipos a menudo compitieron en ambos torneos durante la primera década, y el City College de Nueva York ganó tanto el NIT como el torneo de la NCAA en 1950. Poco después, la NCAA prohibió a los equipos participar en ambos torneos.

Dos cambios importantes a lo largo de la década de 1970 llevaron a que la NCAA se convirtiera en el torneo de postemporada por excelencia para el baloncesto universitario. En primer lugar, la NCAA añadió una regla en 1971 que prohibía a los equipos que rechazaran una invitación al torneo de la NCAA participar en otros torneos de postemporada. Esto fue en respuesta a que Marquette , octavo clasificado, rechazara su invitación en 1970 y, en su lugar, participara y ganara el NIT después de que el entrenador Al McGuire se quejara de su ubicación regional. Desde entonces, el torneo de la NCAA ha sido claramente el más importante, con los campeones de la conferencia y la mayoría de los equipos mejor clasificados participando. [3] En segundo lugar, la NCAA permitió varios equipos por conferencia a partir de 1975. Esto fue en respuesta a que a varios equipos de alto rango se les negaron las ofertas durante la década de 1970. Estos incluyeron a Carolina del Sur en 1970, que estuvo invicto en el juego de la conferencia pero perdió en el torneo ACC; USC , que ocupó el segundo lugar en 1971 , se quedó fuera porque su conferencia estaba representada por UCLA , que ocupó el primer lugar ; y Maryland en 1974 , que ocupó el tercer lugar pero perdió el juego por el campeonato del torneo ACC ante el eventual campeón nacional North Carolina State . [ cita requerida ]

Para dar cabida a las ofertas generales, el torneo se amplió en 1975 para incluir 32 equipos, lo que permitió que un segundo equipo representara a una conferencia además del campeón de la conferencia, [4] y eliminó los byes. En 1979 , el torneo se amplió a 40 equipos y agregó una sexta ronda; 24 equipos recibieron byes a la segunda ronda. Se agregaron ocho equipos más en 1980 con solo 16 equipos recibiendo byes, y se eliminó la restricción en el número de ofertas generales de una conferencia. [4] En 1983 , se agregó una séptima ronda con cuatro juegos de play-in; se agregó un juego de play-in adicional en 1984. A partir de 1973 , los emparejamientos regionales para las semifinales nacionales se rotaron anualmente en lugar de que siempre jugaran las dos regiones orientales y las dos occidentales.

La clasificación también comenzó durante esta era, lo que agregó dramatismo y aseguró que los mejores equipos tuvieran mejores caminos hacia la Final Four. En 1978 , los equipos fueron clasificados en dos grupos separados según su método de clasificación. Cada región tenía cuatro equipos que se clasificaban automáticamente con el puesto Q1-Q4 y cuatro equipos que recibieron una oferta general con el puesto L1-L4. En 1979 , todos los equipos de cada región fueron clasificados del 1 al 10, sin tener en cuenta su método de clasificación.

En 1973, las semifinales nacionales se trasladaron al sábado y el campeonato al lunes por la noche , fecha en la que se han mantenido desde entonces. Antes, el campeonato se jugaba el sábado y las semifinales dos días antes.

Los juegos por el tercer lugar fueron eliminados durante esta era, y los últimos juegos por el tercer lugar regional se jugaron en 1975 y el último juego por el tercer lugar nacional se jugó en 1981 .

En 1985 , el torneo se amplió a 64 equipos, eliminando todos los byes y play-ins. Por primera vez, todos los equipos tuvieron que ganar seis partidos para ganar el torneo. Esta expansión condujo a una mayor cobertura mediática y popularidad en la cultura estadounidense. Hasta 2001 , la Primera y la Segunda Ronda se llevaban a cabo en dos sedes de cada región. [ cita requerida ]

En 1985, la Región Medio Oriente pasó a llamarse Región Sudeste. En 1997 , la Región Sudeste se convirtió en la Región Sur. De 2004 a 2006 , las regiones recibieron el nombre de sus ciudades anfitrionas, por ejemplo, la regional de Phoenix en 2004, la regional de Chicago en 2005 y la regional de Minneapolis en 2006, pero volvieron a las designaciones geográficas tradicionales a partir de 2007. Para el torneo de 2011, la Región Sur fue la Región Sudeste y la Región Medio Oeste la Región Suroeste; ambas volvieron a sus nombres anteriores en 2012. [ cita requerida ]

La Final Four de 1996 fue la última que se disputó en un recinto construido específicamente para el baloncesto. Desde entonces, la Final Four se ha jugado exclusivamente en grandes estadios de fútbol cubiertos.

A partir de 2001 , el campo se amplió de 64 a 65 equipos, agregando al torneo lo que informalmente se conocía como el "juego de play-in" . Esto fue en respuesta a la creación de la Conferencia Mountain West durante 1999. Originalmente, el ganador del torneo de Mountain West no recibía una oferta automática, ya que al hacerlo habría eliminado una de las ofertas generales. Como alternativa a la eliminación de una oferta general, la NCAA amplió el torneo a 65 equipos . Los sembrados # 64 y # 65 fueron sembrados en un grupo regional como 16 sembrados, y luego jugaron el juego de la ronda inaugural el martes anterior al primer fin de semana del torneo. Este juego siempre se jugó en el University of Dayton Arena en Dayton, Ohio.

A partir de 2004 , el comité de selección reveló las clasificaciones generales entre los equipos con el primer puesto. Con base en estas clasificaciones, las regiones se emparejaron de modo que el equipo con el primer puesto en general jugara contra el equipo con el cuarto puesto en general en una semifinal nacional si ambos equipos llegaban a la Final Four. Esto se hizo para evitar que los dos equipos con el primer puesto se enfrentaran antes de la final, como se consideró en gran medida el caso en 1996 , cuando Kentucky jugó contra Massachusetts en la Final Four. Anteriormente, los emparejamientos regionales rotaban anualmente.

En 2010 , hubo especulaciones sobre aumentar el tamaño del torneo a 128 equipos. El 1 de abril de 2010, la NCAA anunció que estaba considerando expandirse a 96 equipos para 2011. Sin embargo, tres semanas después, la NCAA anunció un nuevo contrato de televisión con CBS/Turner que amplió el campo a 68 equipos, en lugar de 96, a partir de 2011. El First Four se creó con la adición de tres juegos de play-in. [5] Dos de los juegos del First Four enfrentan a 16 cabezas de serie entre sí. Los otros dos juegos, sin embargo, enfrentan a las últimas ofertas generales entre sí. La clasificación para los equipos generales será determinada por el comité de selección y fluctúa en función de la clasificación real de los equipos. Al explicar el razonamiento de este formato, el presidente del comité de selección, Dan Guerrero , dijo: "Sentimos que si íbamos a expandir el campo, crearíamos un mejor drama para el torneo si los Primeros Cuatro fueran mucho más emocionantes. Todos podrían estar en la línea 10 o la línea 12 o la línea 11". [5] Como parte de esta expansión, la ronda de 64 pasó a llamarse Segunda Ronda y la ronda de 32 pasó a llamarse Tercera Ronda, siendo los Primeros Cuatro oficialmente la Primera Ronda. [5] En 2016 , las rondas de 64 y 32 volvieron a sus nombres anteriores de Primera Ronda y Segunda Ronda y los Primeros Cuatro se convirtieron en el nombre oficial de la ronda de apertura. [6]

En 2016 , la NCAA introdujo un nuevo logotipo "NCAA March Madness" para la marca de todo el torneo, incluidas canchas con la marca completa en cada una de las sedes del torneo. Anteriormente, la NCAA había utilizado la cancha existente o una cancha genérica de la NCAA.

A partir de 2017 , el equipo con el primer puesto en la clasificación general elige los sitios para sus partidos de primera y segunda ronda y sus posibles partidos regionales. Además, el comité de selección comenzó a publicar los 16 equipos con el primer puesto tres semanas antes del Domingo de Selección como una vista previa de los grupos.

Debido a la pandemia de COVID-19 , la NCAA canceló el torneo de 2020. Inicialmente, la NCAA discutió la posibilidad de realizar una versión abreviada con solo 16 equipos en la ciudad anfitriona de la Final Four, Atlanta. Una vez que se entendió la gran escala de la pandemia, la NCAA canceló el torneo, lo que lo convirtió en la primera edición que no se realizó, y decidió no publicar los cuadros en los que había estado trabajando el Comité de Selección.

En 2021 , el torneo se llevó a cabo íntegramente en el estado de Indiana para reducir los viajes. Esta fue hasta la fecha la única vez que el torneo se llevó a cabo en un estado. Como precaución por el COVID-19, todos los equipos participantes debían permanecer en alojamientos proporcionados por la NCAA hasta que perdieran. El calendario se ajustó para proporcionar tiempo extendido para la evaluación de COVID-19 antes de que comenzara el torneo, y los First Four se llevaron a cabo íntegramente el jueves, la Primera y la Segunda Ronda se retrasaron un día a una ventana de viernes a lunes, y los Sweet Sixteen y Elite Eight también se retrasaron a una ventana de viernes a lunes. Los equipos clasificados entre el 69 y el 72 por el Comité de Selección fueron puestos en "espera" para reemplazar a cualquier equipo que se retirara del torneo debido a los protocolos de COVID-19 durante las 48 horas posteriores al anuncio de los brackets. Solo un juego fue declarado nulo debido al COVID-19, y Oregon avanzó a la segunda ronda porque VCU no pudo participar debido a los protocolos de COVID-19. VCU no fue reemplazado por uno de los primeros cuatro equipos eliminados porque las infecciones por COVID-19 comenzaron más de dos días después de que se anunciaran los cuadros. El torneo volvió a su formato habitual en 2022 .

En respuesta a las protestas de los jugadores del torneo femenino de 2021 sobre la diferente calidad de las instalaciones y la marca, tanto el torneo masculino como el femenino se denominaron "NCAA March Madness" a partir de 2022 con variaciones del mismo logotipo para todo el torneo utilizado por el torneo masculino. Además, la Final Four del torneo masculino se denominó "Final Four masculina" a partir de 2022, lo que refleja la marca "Final Four femenina" que se utiliza para ese torneo desde 1987 .

.jpg/440px-1988_NCAA_Men's_Division_I_Basketball_Tournament_-_National_Semifinals_(ticket).jpg)

El torneo consta de 68 equipos que compiten en siete rondas de un cuadro de eliminación simple . Treinta y dos equipos se clasifican automáticamente para el torneo al ganar su torneo de conferencia, jugado durante las dos semanas anteriores al torneo, y treinta y seis equipos se clasifican al recibir una oferta general en función de su desempeño durante la temporada. [8] El Comité de Selección determina las ofertas generales, clasifica a todos los equipos del 1 al 68 y coloca a los equipos en el cuadro, todo lo cual se revela públicamente el domingo antes del torneo, apodado Domingo de Selección por los medios y los fanáticos. No hay reclasificación durante el torneo y los enfrentamientos en cada ronda posterior están predeterminados por el cuadro. [ cita requerida ]

El torneo se divide en cuatro regiones, cada una de las cuales cuenta con entre dieciséis y dieciocho equipos. Las regiones reciben su nombre de la zona geográfica de EE. UU. de la ciudad que alberga cada semifinal y final regional (la tercera y cuarta ronda del torneo en general). Las ciudades anfitrionas de todas las regiones varían de un año a otro.

El torneo se juega durante tres fines de semana, con dos rondas cada fin de semana. Antes del primer fin de semana, ocho equipos compiten en el First Four para avanzar a la primera ronda. Dos juegos emparejan a los campeones de conferencia con la clasificación más baja y dos juegos emparejan a los clasificados generales con la clasificación más baja. La primera y la segunda ronda se juegan durante el primer fin de semana, las semifinales regionales y las finales regionales durante el segundo fin de semana, y las semifinales nacionales y el juego del campeonato durante el tercer fin de semana. Las rondas regionales se denominan Sweet Sixteen y Elite Eight y el tercer fin de semana se denomina Final Four, todas nombradas según el número de equipos restantes al comienzo de la ronda. Todos los juegos, incluido el First Four, están programados de modo que los equipos tengan un día de descanso entre cada juego. Este formato se ha utilizado desde 2011, con cambios menores en el calendario en 2021 debido a la pandemia de COVID-19 . [ cita requerida ]

El Comité de Selección, que incluye a los comisionados de las conferencias y a los directores deportivos de las universidades designados por la NCAA, determina el cuadro durante la semana anterior al torneo. Dado que los resultados de varios torneos de conferencias que se llevan a cabo durante la misma semana pueden afectar significativamente el cuadro, el Comité suele elaborar varios cuadros para diferentes resultados.

Para hacer el cuadro, el Comité clasifica a todo el campo del 1 al 68; estos se conocen como el verdadero sembrado . Luego, el comité divide a los equipos entre las cuatro regiones, dando a cada uno un sembrado entre el No. 1 y el No. 16. Los mismos cuatro sembrados en todas las regiones se conocen como la línea de sembrados (es decir, la línea de sembrados No. 6). Ocho equipos se duplican y compiten en el First Four. Dos de los equipos emparejados compiten por los sembrados No. 16, y los otros dos equipos emparejados son los últimos equipos generales a los que se les otorgan ofertas para el torneo y compiten por una línea de sembrados en el rango del No. 10 al No. 14, que varía de año en año en función de los sembrados reales de los equipos en general. [9]

Los cuatro primeros clasificados en general se colocan como cabezas de serie N.º 1 en cada región. Las regiones se emparejan de modo que si todos los cabezas de serie N.º 1 llegan a la Final Four, el verdadero favorito N.º 1 jugará con el N.º 4 y el N.º 2 jugará con el N.º 3. Los equipos N.º 2 se colocan preferiblemente de modo que el verdadero favorito N.º 5 no se empareje con el verdadero favorito N.º 1. El comité garantiza el equilibrio competitivo entre los cuatro primeros clasificados en cada región sumando los valores de los verdaderos favoritos y comparando los valores entre las regiones. Si hay una desviación significativa, algunos equipos se moverán entre las regiones para equilibrar la distribución de los verdaderos favoritos. [9]

Si una conferencia tiene de dos a cuatro equipos entre los cuatro primeros clasificados, se los colocará en regiones diferentes. De lo contrario, los equipos de la misma conferencia se colocan para evitar una revancha antes de las finales regionales si han jugado tres o más veces en la temporada, las semifinales regionales si han jugado dos veces, o la segunda ronda si han jugado una vez. Además, se recomienda al comité evitar las revanchas de la temporada regular y del torneo del año anterior en el First Four. Finalmente, el comité intentará asegurarse de que un equipo no sea movido fuera de su región geográfica preferida una cantidad desmesurada de veces en función de su ubicación en los dos torneos anteriores. Para cumplir con estas reglas y preferencias, el comité puede mover a un equipo fuera de su línea de clasificación esperada. Así, por ejemplo, el equipo que ocupa el puesto 40 en la clasificación general, originalmente programado para ser el puesto n.° 10 dentro de una región en particular, puede en cambio ser movido a un puesto n.° 9 o ser movido a un puesto n.° 11. [9]

Desde 2012, el comité publica la lista de los equipos que ocupan los puestos 1 al 68 después de anunciar el cuadro. [9] Desde 2017, el Comité de Selección publica una lista de los 16 mejores equipos tres semanas antes del Domingo de Selección. Esta lista no garantiza una candidatura para ningún equipo, ya que el Comité vuelve a clasificar a todos los equipos al iniciar el proceso de selección final. [10]

La línea de cabezas de serie de los cuatro equipos que compiten en el First Four ha variado cada año, dependiendo de la clasificación general de los equipos en el campo. [9]

En el torneo masculino, todos los sitios son nominalmente neutrales; los equipos tienen prohibido jugar partidos del torneo en sus canchas locales durante la primera, segunda y rondas regionales. Según las reglas de la NCAA, cualquier cancha en la que un equipo albergue más de tres juegos de temporada regular (sin incluir juegos de pretemporada o torneos de conferencia) se considera una "cancha local". [9] Para el First Four y el Final Four, la prohibición de la cancha local no se aplica porque solo una sede alberga estas rondas. El First Four es organizado regularmente por los Dayton Flyers ; como tal, el equipo compitió en su cancha local en 2015. [ 11] Debido a que el Final Four se organiza en estadios de fútbol bajo techo, es poco probable que un equipo juegue en su cancha local en el futuro. La última vez que esto fue posible fue en 1996, cuando el Continental Airlines Arena , cancha local de Seton Hall , lo albergó.

Para la primera y la segunda ronda, ocho sedes albergarán partidos, cuatro en cada día de la ronda. Cada sede albergará dos grupos de cuatro equipos, denominados "grupos". Para limitar los viajes, los equipos se ubican en grupos más cercanos a su sede, a menos que las reglas de clasificación lo impidan. Debido a que cada grupo incluye a uno de los cuatro primeros clasificados, los equipos mejor clasificados normalmente obtienen los sitios más cercanos.

Las posibles vainas por siembra son:

* Título vacante no incluido

Un total de 333 equipos han aparecido en el torneo de la NCAA desde 1939. Debido a que la NCAA no se dividió en divisiones hasta 1957 , algunas escuelas que han aparecido en el torneo ya no están en la División I. Entre las escuelas de la División I, 46 nunca han llegado al torneo, incluidas 11 que no son elegibles porque están en transición a la División I.

Llave

Para cada temporada que comienza en 1979, los 4 equipos clasificados en el puesto n.º 1 se muestran con doble subrayado , y los 12 equipos clasificados entre el puesto n.º 2 y el n.º 4 se muestran con subrayado punteado .

Bold indicates an active current streak as of the 2024 tournament.

*Kansas's 2018 appearance was vacated.

As a tournament ritual, the winning team cuts down the nets at the end of regional championship games as well as the national championship game. Starting with the seniors, and moving down by classes, players each cut a single strand off each net; the head coach cuts the last strand connecting the net to the hoop, claiming the net itself.[12] An exception to the head coach cutting the last strand came in 2013, when Louisville head coach Rick Pitino gave that honor to Kevin Ware, who had suffered a catastrophic leg injury during the tournament.[13] This tradition is credited to Everett Case, the coach of North Carolina State, who stood on his players' shoulders to accomplish the feat after the Wolfpack won the Southern Conference tournament in 1947.[14] CBS, since 1987 and yearly to 2015, in the odd-numbered years since 2017, and TBS, since 2016, the even-numbered years, close out the tournament with "One Shining Moment", performed by Luther Vandross.

Just as the Olympics awards gold, silver, and bronze medals for first, second, and third place, respectively, the NCAA awards the national champions a gold-plated wooden NCAA national championship trophy. The loser of the championship game receives a silver-plated national runner-up trophy for second place. Since 2006, all four Final Four teams receive a bronze plated NCAA regional championship trophy; prior to 2006, only the teams who did not make the title game received bronze plated trophies for being a semifinalist.

The champions also receive a commemorative gold championship ring, and the other three Final Four teams receive Final Four rings.

The National Association of Basketball Coaches also presents a more elaborate marble/crystal trophy to the winning team. Ostensibly, this award is given for taking the top position in the NABC's end-of-season poll, but this is invariably the same as the NCAA championship game winner. In 2005, Siemens AG acquired naming rights to the NABC trophy, which is now called the Siemens Trophy. Formerly, the NABC trophy was presented right after the standard NCAA championship trophy, but this caused some confusion.[15] Since 2006, the Siemens/NABC trophy has been presented separately at a press conference the day after the game.[16]

After the championship trophy is awarded, one player is selected and then awarded the Most Outstanding Player award (which almost always comes from the championship team). It is not intended to be the same as a Most Valuable Player award although it is sometimes informally referred to as such.

Because the NBA draft takes place just three months after the NCAA tournament, NBA executives have to decide how players' performances in a maximum of seven games, from the First Four to the championship game, should affect their draft decisions. A 2012 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research explores how the March tournament affects the way that professional teams behave in the June draft. The study is based on data from 1997 to 2010 that looks at how college tournament standouts performed at the NBA level.[17][18]

The researchers determined that a player who outperforms his regular season averages or who is on a team that wins more games than its seed would indicate will be drafted higher than he otherwise would have been. At the same time, the study indicated that professional teams do not take college tournament performance into consideration as much as they should, as success in the tournament correlates with elite professional accomplishment, particularly top-level success. "If anything, NBA teams undervalue the signal provided by unexpected performance in the NCAA March Madness tournament as a predictor of future NBA success."[17][18]

Since 2011, the NCAA has had a joint contract with CBS and Warner Bros. Discovery. The coverage of the tournament is split between CBS, TNT, TBS, and truTV.[19]

Broadcasters from CBS, TBS, and TNT's sports coverage are shared across all four networks, with CBS' college basketball teams supplemented with TNT's NBA teams, while studio segments take place at the CBS Broadcast Center in New York City and TNT's studios in Atlanta. In the New York–based studio shows, CBS' Greg Gumbel and Clark Kellogg are joined by Kenny Smith, and Charles Barkley of TNT's Inside the NBA while Seth Davis and Jay Wright of CBS assist with Inside the NBA's Ernie Johnson, as well as Adam Lefkoe and Candace Parker of TNT's Tuesday night NBA coverage. While three of TNT's NBA voices, Kevin Harlan, Ian Eagle, and Spero Dedes are already employed by CBS in other capacities, TNT also lends analysts Stan Van Gundy, Jim Jackson, Grant Hill, and Steve Smith, secondary play-by-play man Brian Anderson, and reporters Allie LaForce and Lauren Shehadi, the latter being from TBS's MLB coverage, to CBS. In turn, CBS announcers Brad Nessler, Andrew Catalon, and Tom McCarthy appear on WBD network broadcasts along with analysts Jim Spanarkel, Bill Raftery, Dan Bonner, Steve Lappas, Brendan Haywood, and Avery Johnson, as well as reporters Tracy Wolfson, Evan Washburn, A. J. Ross, and Jon Rothstein, and rules analyst Gene Steratore. Announcers from other networks like Lisa Byington and Robbie Hummel from Fox, the latter also working for Peacock and Big Ten Network, Debbie Antonelli from ESPN, Jamie Erdahl from NFL Network, and Andy Katz from NCAA.com are also lent to CBS and TNT.

The most recent transaction in 2016 renews the contract through 2032 and provides for the nationwide broadcast each year of all games of the tournament. All First Four games air on truTV. A featured first- or second-round game in each time "window" is broadcast on CBS, while all other games are shown either on TBS, TNT or truTV. The regional semifinals, better known as the Sweet Sixteen, are split between CBS and TBS. CBS had the exclusive rights to the regional finals, also known as the Elite Eight, through 2014. That exclusivity extended to the entire Final Four as well, but after the 2013 tournament Turner Sports elected to exercise a contractual option for 2014 and 2015 giving TBS broadcast rights to the national semifinal matchups.[20] CBS kept its national championship game rights.[20]

Since 2015, CBS and TBS split coverage of the Elite Eight. Since 2016 CBS and TBS alternate coverage of the Final Four and national championship game, with TBS getting the final two rounds in even-numbered years, and CBS getting the games in odd-numbered years. March Madness On Demand would remain unchanged, although Turner was allowed to develop their own service.[21]

The CBS broadcast provides the NCAA with over $500 million annually, and makes up over 90% of the NCAA's annual revenue.[22] The revenues from the multibillion-dollar television contract are divided among the Division I basketball playing schools and conferences as follows:[23]

CBS has been the major partner of the NCAA in televising the tournament since 1982, but there have been many changes in coverage since the tournament was first broadcast in 1969.

From 1969 to 1981, the NCAA tournament aired on NBC, but not all games were televised. The early rounds, in particular, were not always seen on TV.

In 1982, CBS obtained broadcast television rights to the NCAA tournament.

In 1980, ESPN began showing the opening rounds of the tournament. This was the network's first contract signed with the NCAA for a major sport, and helped to establish ESPN's following among college basketball fans. ESPN showed six first-round games on Thursday and again on Friday, with CBS, from 1982 to 1990, then picking up a seventh game at 11:30 pm ET. Thus, 14 of 32 first-round games were televised. ESPN also re-ran games overnight. At the time, there was only one ESPN network, with no ability to split its signal regionally, so ESPN showed only the most competitive games. During the 1980s, the tournament's popularity on television soared.[citation needed]

However, ESPN became a victim of its own success, as CBS was awarded the rights to cover all games of the NCAA tournament, starting in 1991. Only with the introduction of the so-called "play-in" game (between the 64 seed and the 65 seed) in the 2000s, did ESPN get back in the game (and actually, the first time this "play-in" game was played in 2001, the game was aired on The Nashville Network, using CBS graphics and announcers, as both CBS and TNN were both owned by Viacom at the time.[27]

Through 2010, CBS broadcast the remaining 63 games of the NCAA tournament proper. Most areas saw only eight of 32 first-round games, seven of 16 second-round games, and four of eight regional semifinal games (out of the possible 56 games during these rounds; there would be some exceptions to this rule in the 2000s). Coverage preempted regular programming on the network, except during a 2-hour window from about 5 ET until 7 ET when the local affiliates could show programming. The CBS format resulted in far fewer hours of first-round coverage than under the old ESPN format but allowed the games to reach a much larger audience than ESPN was able to reach.[citation needed]

During this period of near-exclusivity by CBS, the network provided to its local affiliates three types of feeds from each venue: constant feed, swing feed, and flex feed. Constant feeds remained primarily on a given game, and were used primarily by stations with a clear local interest in a particular game. Despite its name, a constant feed occasionally veered away to other games for brief updates (as is typical in most American sports coverage), but coverage generally remained with the initial game. A swing feed tended to stay on games believed to be of natural interest to the locality, such as teams from local conferences, but may leave that game to go to other games that during their progress become close matches. On a flex feed, coverage bounced around from one venue to another, depending on action at the various games in progress. If one game was a blowout, coverage could switch to a more competitive game. A flex feed was provided when there were no games with a significant natural local interest for the stations carrying them, which allowed the flex game to be the best game in progress. Station feeds were planned in advance and stations had the option of requesting either constant or flex feed for various games.[citation needed]

In 1999, DirecTV began broadcasting all games otherwise not shown on local television with its Mega March Madness premium package. The DirecTV system used the subscriber's ZIP code to black out games which could be seen on broadcast television. Prior to that, all games were available on C-Band satellite and were picked up by sports bars.

In 2003, CBS struck a deal with Yahoo! to offer live streaming of the first three rounds of games under its Yahoo! Platinum service, for $16.95 a month.[28] In 2004, CBS began selling viewers access to March Madness On Demand, which provided games not otherwise shown on broadcast television; the service was free for AOL subscribers. In 2006, March Madness On Demand was made free, and continued to be so to online users through the 2011 tournament. For 2012, it once again became a pay service, with a single payment of $3.99 providing access to all 67 tournament games. In 2013, the service, now renamed March Madness Live, was again made free, but uses Turner's rights and infrastructure for TV Everywhere, which requires sign-in though the password of a customer's cable or satellite provider to watch games, both via PC/Mac and mobile devices. Those that do not have a cable or satellite service or one not participating in Turner's TV Everywhere are restricted to games carried on the CBS national feed and three hours (originally four) of other games without sign-in, or coverage via Westwood One's radio coverage. Effective with the 2018 tournament, the national semifinals and final are under TV Everywhere restrictions if they are aired by Turner networks; before then, those particular games were not subject to said restrictions.

In addition, CBS Sports Network (formerly CBS College Sports Network) had broadcast two "late early" games that would not otherwise be broadcast nationally. These were the second games in the daytime session in the Pacific Time Zone, to avoid starting games before 10 AM. These games are also available via March Madness Live and on CBS affiliates in the market areas of the team playing. In other markets, newscasts, local programming or preempted CBS morning programming are aired. CBSSN is scheduled to continue broadcasting the official pregame and postgame shows and press conferences from the teams involved, along with overnight replays.[29]

The Final Four has been broadcast in HDTV since 1999. From 2000 to 2004, only one first/second round site and one regional site were designated as HDTV sites. In 2005, all regional games were broadcast in HDTV, and four first and second round sites were designated for HDTV coverage. Local stations broadcasting in both digital and analog had the option of airing separate games on their HD and SD channels, to take advantage of the available high definition coverage. Beginning in 2007, all games in the tournament (including all first and second-round games) were available in high definition, and local stations were required to air the same game on both their analog and digital channels. However, due to satellite limitations, first round "constant" feeds were only available in standard definition.[30] Moreover, some digital television stations, such as WRAL-TV in Raleigh, North Carolina, choose not to participate in HDTV broadcasts of the first and second rounds and the regional semifinals, and used their available bandwidth to split their signal into digital subchannels to show all games going on simultaneously.[31] By 2008, upgrades at the CBS broadcast center allowed all feeds, flex and constant, to be in HD for the tournament.

As of 2011, ESPN International holds international broadcast rights to the tournament, distributing coverage to its co-owned networks and other broadcasters. ESPN produces the world feed for broadcasts of the Final Four and championship game, produced using ESPN College Basketball staff and commentators.[32][33][34][35]

The top ten programs in total NCAA victories:

*Vacated victories not included

Programs with ten or more appearances in the Final Four:

*Vacated appearances not included

Since 1979, the NCAA has seeded each region. Beginning in 2004, the Selection Committee announced the rankings among the 1 seeds, designating an overall #1 seed and pairing the regions so that the overall #1 seed would meet the #4 overall seed in the Final Four if both advanced. The overall rankings are denoted with the numbers in parentheses. The following teams received the top ranking in each region:

*Vacated

Bold denotes team also won tournament

Last updated through 2024 tournament.

*Vacated appearances not included (see #1 seeds by year and region)

Only once did all four No. 1 seeds make it to the Final Four:

Four times (including three since the field expanded to 64 teams) the Final Four has been without a No. 1 seed:

Since 1985, there have been 4 instances of three No. 1 seeds reaching the Final Four; 13 instances of two No. 1 seeds making it; and 14 instances of just one No. 1 seed reaching the Final Four. 2023 was the first Final Four without a 1, 2, or 3 seed.

There have been ten occasions (nine times since the field expanded to 64) that the championship game has been played between two No. 1 seeds:

Since 1985 there have been 18 instances of one No. 1 seed reaching the Championship Game (No. 1 seeds are 13–5 against other seeds in the title game) and 8 instances where no No. 1 seed made it to the title game.

Teams that entered the tournament ranked No. 1 in at least one of the AP, UPI, or USA Today polls and won the tournament:[36]

The record here refers to the record before the first game of the NCAA tournament.

The NCAA tournament has dramatically expanded since 1975, and since the expansion to 48 teams in 1980, no unbeaten team has failed to qualify. Since by definition, a team would have to win its conference tournament, and thus secure an automatic bid to the tournament, to be undefeated in a season, the only way a team could finish undefeated and not reach the tournament is if the team is banned from postseason play. As of 2021, no team banned from postseason play has finished undefeated since 1980. Other possibilities for an undefeated team to fail to qualify: the team is independent; the conference does not have an automatic bid; or the team is transitioning from a lower NCAA division or the NAIA, during which time it is barred from NCAA-sponsored postseason play in the NCAA tournament or NIT. No men's team from a transitional D-I member has been unbeaten after its conference tournament, but one such women's team has been—California Baptist in 2021. (CBU was able to play in the women's NIT, which has never been operated by the NCAA.)

Before 1980, there were occasions on which a team achieved perfection in the regular season, yet did not appear in the NCAA tournament.

Eight programs have repeated as national championships. UCLA is the only program to win more than 2 in a row, winning 7 straight from 1967 to 1973. These programs are:

There have been nine times in which the tournament did not include the reigning champion (the previous year's winner):

Mid-major teams—which are defined as teams from the America East Conference (America East), ASUN Conference (ASUN), Atlantic 10 (A-10), Big Sky Conference (Big Sky), Big South Conference (Big South), Big West Conference (Big West), Coastal Athletic Association (CAA), Conference USA (C-USA), Horizon League (Horizon), Ivy League (Ivy), Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference (MAAC), Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC), Missouri Valley Conference (MVC), Mountain West Conference (MW), Northeast Conference (NEC), Ohio Valley Conference (OVC), Patriot League (Patriot), Southern Conference (SoCon), Southland Conference (Southland), Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC), Summit League (Summit), Sun Belt Conference (Sun Belt), West Coast Conference (WCC), and the Western Athletic Conference (WAC)[40]—have experienced success in the tournament.

The last time, as of 2024, a mid-major team won the National Championship was 1990 when UNLV won with a 103–73 win over Duke, since UNLV was then a member of the Big West and since 1999 has been a member of the MW; the Big West was not then considered a power conference, nor is the MW today. However, during the tenure of UNLV's coach at the time, Jerry Tarkanian, the Runnin' Rebels were widely viewed as a major program despite their conference affiliation (a situation similar to that of Gonzaga since the first years of the 21st century). Additionally, the Big West received three bids in the 1990 tournament. The last time, as of 2024, an independent mid-major team won the national championship was 1977 when Marquette won 67–59 over North Carolina. However, Marquette was not considered a "mid-major" program at that time. The very term "mid-major" was not coined until 1977 and did not see wide use until the 1990s. More significantly, Marquette was one of several traditional basketball powers that were still NCAA Division I independents in the late 1970s. Also, Marquette has been a member of widely acknowledged "major" basketball conferences since 1991, and is currently in the undeniably major Big East Conference. The last time, as of 2024, a mid-major team from a small media market (defined as a market that is outside of the top 25 television markets in the United States in 2024) won the National Championship was arguably 1962 when Cincinnati, then in the MVC, won 71–59 over Ohio State of the Big Ten, since Cincinnati's TV market is listed 35th in the nation as of 2024. However, the MVC was generally seen in that day as a major basketball conference.

The last time the Final Four was composed, as of 2024, of at least 75% mid-major teams (3/4), i.e. excluding all present-day major conferences or their predecessors, was 1979, where Indiana State, then as now of the Missouri Valley Conference (which had lost several of its most prominent programs, among them Cincinnati, earlier in the decade); Penn, then as now in the Ivy League; and DePaul, then an independent, participated in the Final Four, only to see Indiana State lose to Michigan State. The last time, as of 2024, the Final Four has been composed of at least 50% mid-major teams (2/4) was 2023, when Florida Atlantic, of Conference USA, and San Diego State, of the Mountain West Conference, participated in the Final Four, only to see San Diego State lose to UConn. To date, as of 2024, no Final Four has been composed of 100% mid-major teams (4/4), therefore guaranteeing a mid-major team winning the national championship.

Arguably the tournament with the most mid-major success was the 1970 tournament, which had 63% representation of mid-major teams in the Sweet 16 (10/16), 75% representation in the Elite 8 (6/8), 75% representation in the Final 4 (3/4), and 50% representation in the national championship game (1/2). Jacksonville lost to UCLA in the National Championship, with New Mexico State defeating St. Bonaventure for third place.

This table shows the performance of mid-major teams from the Sweet Sixteen round to the national championship game from 1939—the tournament's first year—to 2024.

This table shows teams that saw success in the tournament from later defunct conferences, or were independents.

One conference listed, the Southwest Conference, was universally considered a major conference throughout its history. Of its final eight members, five moved to conferences typically considered "major" in basketball—three in the Big 12, one in the SEC, and one in The American. Another member that left during the SWC's last decade also moved to the SEC. The Metro Conference, which operated from 1975 to 1995, is not listed because it was considered a major basketball conference throughout its history. The, Louisville, which was a member for the league's entire existence, won both of its NCAA-recognized titles (1980, 1986) while in the Metro. It was one of the two leagues that merged to form the Conference USA. The other league involved in the merger, the Great Midwest Conference, was arguably a major conference; it was formed in 1990, with play starting in 1991, when several of the Metro's strongest basketball programs left that league.

Rick Pitino is the only coach to have officially taken three teams to the Final Four: Providence (1987), Kentucky (1993, 1996, 1997) and Louisville (2005, 2012).

There are 14 coaches who have officially coached two schools to the Final Four – Roy Williams, Eddie Sutton, Frank McGuire, Lon Kruger, Hugh Durham, Jack Gardner, Lute Olson, Gene Bartow, Forddy Anderson, Lee Rose, Bob Huggins, Lou Henson, Kelvin Sampson and Jim Larrañaga.

Point differentials, or margin of victory, can be viewed either by the championship game, or by a team's performance over the whole tournament.

30 points, by UNLV in 1990 (103–73, over Duke)

1 point, on six occasions

Eight times the championship game has been tied at the end of regulation. On one of those occasions (1957) the game went into double and then triple overtime.

Teams that played 6 games

Teams that played 5 games

Teams that played 4 games

Teams that played 3 games

Achieved 14 times by 10 schools

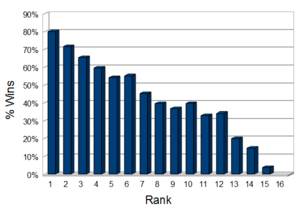

Since the inception of the 64-team tournament in 1985, each seed-pairing has played 156 games in the Round of 64, with the following results:

Until 1952, the national championship was played at a separate site from the national semifinal games, which were considered regional finals. Forty-one different venues have hosted the final rounds, and several have hosted more than five times:

Among cities, Kansas City has hosted the Final Four a total of ten times, with Kemper Arena hosting in 1988 in addition to Municipal Auditorium. New York and Indianapolis have both hosted seven times, with the latter doing so at three venues: Market Square Arena in 1980, four times in the RCA Dome between 1991 and 2006, and three times in Lucas Oil Stadium, between 2010 and 2021. The state of Texas has hosted the Final Four eleven times in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and Arlington between 1971 and 2023.

For most of the tournament's history, the national championship game and national semifinal games have been played in basketball arenas. The first instance of a domed stadium being used for the Final Four was the Houston Astrodome in 1971, but the Final Four would not return to a dome until 1982 when the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans hosted the event for the first time. The last on-campus venue to host the Final Four was University Arena in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1983. The last venue primarily built for a college basketball team to host the Final Four was Rupp Arena in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1985. The last NBA arena to host the Final Four was the Meadowlands Arena, then known as Continental Airlines Arena, in 1996. From 1997 to 2013, the NCAA required that the Final Four be played in domed stadiums with a minimum capacity of 40,000. As of 2009,[clarify] the minimum was increased to 70,000, by adding additional seating on the floor of the dome, and raising the court on a platform three feet above the dome's floor.

In September 2012, the NCAA began preliminary discussions on the possibility of returning occasional Final Fours to basketball-specific arenas in major metropolitan areas. According to ESPN.com writer Andy Katz, when Mark Lewis was hired as NCAA executive vice president for championships during 2012, "he took out a United States map and saw that both coasts are largely left off from hosting the Final Four."[43] Lewis added in an interview with Katz,

I don't know where this will lead, if anywhere, but the right thing is to sit down and have these conversations and see if we want our championship in more than eight cities or do we like playing exclusively in domes. None of the cities where we play our championship is named New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Chicago or Miami. We don't play on a campus. We play in professional football arenas.[43]

Under then-current criteria, only eleven stadiums could be considered as Final Four locations.[43] On June 12, 2013, Katz reported that the NCAA had changed its policy. In July 2013, the NCAA had a portal available on its website for venues to make Final Four proposals in the 2017–2020 period, and there were no restrictions on proposals based on venue size. Also, the NCAA decided that future regionals will no longer be held in domes. In Katz' report, Lewis indicated that the use of domes for regionals was intended as a dry run for future Final Four venues, but this particular policy was no longer necessary because all of the Final Four sites from 2014 to 2016 had already hosted regionals.[44] The policy was changed to only be used if a new venue would be hosting the subsequent tournament's Final Four.[45][46] Under the current policy, the 2030 regionals could be held at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, which opened in 2017 that will be hosting its first Final Four in 2031.

On several occasions NCAA tournament teams played their games in their home arena. In 1959, Louisville played at its regular home of Freedom Hall; however, the Cardinals lost to West Virginia in the semifinals. In 1984, Kentucky defeated Illinois, 54–51 in the Elite Eight on its home court of Rupp Arena. Also in 1984, #6 seeded Memphis played the first 2 rounds on its home court, defeating Oral Roberts and Purdue. In 1985, Dayton played its first-round game against Villanova (it lost 51–49) on its home floor. In 1986 (beating Brown before losing to Navy) and '87 (beating Georgia Southern and Western Kentucky), Syracuse played the first 2 rounds of the NCAA tournament in the Carrier Dome. Also in 1986, LSU played in Baton Rouge on its home floor for the first 2 rounds despite being an 11th seed (beating Purdue and Memphis State). In 1987, Arizona lost to UTEP on its home floor in the first round. In 2015, Dayton played at its regular home of UD Arena, and the Flyers beat Boise State in the First Four.

Since the inception of the modern Final Four in 1952, only once has a team played a Final Four on its actual home court—Louisville in 1959. But through the 2015 tournament, three other teams have played the Final Four in their home cities, one other team has played in its metropolitan area, and six additional teams have played the Final Four in their home states through the 2015 tournament. Kentucky (1958 in Louisville), UCLA (1968 and 1972 in Los Angeles, 1975 in San Diego), and North Carolina State (1974 in Greensboro) won the national title; Louisville (1959 at its home arena, Freedom Hall); Purdue (1980 in Indianapolis) lost in the Final Four; and California (1960 in the San Francisco Bay Area), Duke (1994 in Charlotte), Michigan State (2009 in Detroit), and Butler (2010 in Indianapolis) lost in the final.

In 1960, Cal had nearly as large an edge as Louisville had the previous year, only having to cross the San Francisco Bay to play in the Final Four at the Cow Palace in Daly City; the Golden Bears lost in the championship game to Ohio State. UCLA had a similar advantage in 1968 and 1972 when it advanced to the Final Four at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, not many miles from the Bruins' homecourt of Pauley Pavilion (also UCLA's home arena before the latter venue opened in 1965, and again during the 2011–12 season while Pauley was closed for renovations); unlike Louisville and Cal, the Bruins won the national title on both occasions. Butler lost the 2010 title 6 miles (9.7 km) from its Indianapolis campus.

Before the Final Four was established, the east and west regionals were held at separate sites, with the winners advancing to the title game. During that era, three New York City teams, all from Manhattan, played in the east regional at Madison Square Garden—frequently used as a "big-game" venue by each team—and advanced at least to the national semifinals. NYU won the east regional in 1945 but lost in the title game, also held at the Garden, to Oklahoma A&M. CCNY played in the east regional in both 1947 and 1950; the Beavers lost in the 1947 east final to eventual champion Holy Cross but won the 1950 east regional and national titles at the Garden.

In 1974, North Carolina State won the NCAA tournament without leaving its home state of North Carolina. The team was put in the east region, and played its regional games at its home arena Reynolds Coliseum. NC State played the Final Four and national championship games at nearby Greensboro Coliseum.

While not its home state, Kansas has played in the championship game in Kansas City, Missouri, only 45 minutes from the campus in Lawrence, Kansas, on four different occasions. In 1940, 1953, and 1957 the Jayhawks lost the championship game each time at Municipal Auditorium. In 1988, playing at Kansas City's Kemper Arena, Kansas won the championship, over Big Eight–rival Oklahoma. Similarly, in 2005, Illinois played in St. Louis, Missouri, where it enjoyed a noticeable home court advantage, yet still lost in the championship game to North Carolina.

In 2002, Texas was paired with Mississippi State in Dallas despite being the lower seed. The #6 seeded Longhorns defeated the #3 seeded Bulldogs 68–64 in front of a predominately Texas crowd.

The NCAA had banned the Bon Secours Wellness Arena, originally known as Bi-Lo Center, and Colonial Life Arena, originally Colonial Center, in South Carolina from hosting tournament games, despite their sizes (16,000 and 18,000 seats, respectively) because of an NAACP protest at the Bi-Lo Center during the 2002 first and second round tournament games over that state's refusal to completely remove the Confederate Battle Flag from the state capitol grounds, although it had already been relocated from atop the capitol dome to a less prominent place in 2000. Following requests by the NAACP and Black Coaches Association, the Bi-Lo Center, and the newly built Colonial Center, which was built for purposes of hosting the tournament, were banned from hosting any future tournament events.[47] As a result of the removal of the battle flag from the South Carolina State Capitol, the NCAA lifted its ban on South Carolina hosting games in 2015, and it was able to host in 2017 due to North Carolina House Bill 2 (see next section).[48]

On September 12, 2016, the NCAA stripped the state of North Carolina of hosting rights for seven upcoming college sports tournaments and championships held by the association, including early round games of the 2017 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament scheduled for the Greensboro Coliseum. The NCAA argued that House Bill 2 made it "challenging to guarantee that host communities can help deliver [an inclusive atmosphere]".[49][50] Bon Secours Wellness Arena was able to secure the bid to be the replacement site.[51]

Ahead of the 75th anniversary of the tournament, on December 11, 2012, the NCAA announced the 75 best players, the 25 best teams, and the 35 best moments in tournament history. The NCAA started with a group of more than 100 nominees and then analyzed the tournament statistics for each player to select the 75 finalists from which the public would select the top 15 via an online poll in January 2013.[52]

The results of the public vote were revealed at the 2013 NCAA Final Four.[53][54] Among the 15 players, ten had won a championship, 11 were declared the Most Outstanding Player of the tournament at least once, and all made the Final Four at least once. Abdul-Jabbar, Laettner, Lucas, Olajuwon, and Walton all reached the Final Four in every season they played college basketball, and an additional five players went to multiple Final Fours. Hill, Laettner, Russell, and Walton all won two championships, and Abdul-Jabbar won three championships. Lucas and Walton repeated as Most Outstanding Players, and Abdul-Jabbar was declared the MOP all three seasons he played. Bradley, Lucas, Olajuwon, and West were all declared MOP without winning the championship. Twelve players competed in the tournament every year they played college basketball.

UCLA and Duke are the only team with multiple honorees. Christian Laettner and Grant Hill are the only teammates, they played together for Duke and won two championships in 1991 and 1992. Larry Bird and Magic Johnson competed against each other in the 1979 NCAA Championship Game, and Patrick Ewing and Michael Jordan competed against each other in the 1982 NCAA Championship Game as freshmen. Oscar Robertson and Jerry West competed during the same seasons, but never met in the tournament.

Eleven of the players have been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the College Basketball Hall of Fame as players. Michael Jordan and Olajuwon have only been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial as players, and Christian Laettner and Danny Manning have only been inducted into the CBHOF as players. Bill Russell has also been enshrined in the Naismith Memorial as a coach.

Patrick Ewing (Georgetown) and Danny Manning (Tulsa and Wake Forest) have appeared in the tournament as head coaches. Manning has also recorded six appearances, two Final Fours, one runner-up, and one championship as an assistant for Kansas.

The NCAA tournament and the Super Bowl are the two American sports events that draw both fans and non-fans.[55][56] Many people are connected to a school in the tournament, having been an alumnus of one of the participants, knowing someone from the college, or living close to the school.[56]

There are pools or private gambling-related contests in which participants predict the outcome of each tournament game, filling out a complete tournament bracket in the process. The popularity of this practice grew around 1985, when the tournament expanded to 64 games, forming four symmetrical regions with 15 games apiece to decide the Final Four.[57] In 2023, Sports Illustrated reported that an estimated 60 to 100 million brackets are filled out each year.[58] Filling out a tournament bracket with predictions is called the practice of "bracketology;" sports programming during the tournament often features commentators comparing the accuracy of their predictions. On The Dan Patrick Show, a wide variety of celebrities from various fields (such as Darius Rucker, Charlie Sheen, Neil Patrick Harris, Ellen DeGeneres, Dave Grohl, and Brooklyn Decker) have posted full brackets with predictions. Former U.S. president Barack Obama began releasing his bracket annually in 2009, his first year in office.[59] While in office, he filled out the men's and women's brackets on ESPN with reporter Andy Katz,[60] and they were also posted on the White House website.[61] He continued releasing his picks after leaving office.[62]

There are many tournament prediction scoring systems. Most award points for correctly picking the winning team in a particular match up, with increasingly more points being given for correctly predicting later round winners. Some provide bonus points for correctly predicting upsets, the amount of the bonus varying based on the degree of upset. Some just provide points for wins by correctly picked teams in the brackets.

There are 2^63 or about 9.22 quintillion unique combinations of winners in a 64-team NCAA bracket, meaning that without considering seed number, the odds of picking a perfect bracket are about 9.22 quintillion to 1.[58] Including the First Four, the number of unique combinations increases to 2^67 or about 147.57 quintillion.

There are numerous awards and prizes given by companies for anyone who can make the perfect bracket. One of the largest was done by a partnership between Quicken Loans and Berkshire Hathaway, which was backed by Warren Buffett, with a $1 billion prize to any person(s) who could correctly predict the outcome of the 2014 tournament. No one was able to complete the challenge and win the $1 billion prize.[63]

During the tournament, American workers take extended lunch breaks at sports bars to follow the game. They also use company computer and internet access to view games, scores, and bracket results. Some workplaces block access to sports and entertainment sites, but the rise of mobile devices and live-streamed games bypassed those restrictions, and even workers not normally in front of computers then had access.[55] Workers spend an estimated average of six hours on the tournament each year,[64] and U.S. employers are projected to lose around $13 billion due to lost productivity during the tournament.[65][66]

As indicated below, none of these phrases are exclusively used in regard to the NCAA tournament. Nonetheless, they are associated widely with the tournament, sometimes for legal reasons, sometimes as part of the American sports vernacular.

March Madness is a popular term for season-ending basketball tournaments played in March. March Madness is also a registered trademark currently owned exclusively by the NCAA.

H. V. Porter, an official with the Illinois High School Association (and later a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame), was the first person to use March Madness to describe a basketball tournament. Porter published an essay named March Madness during 1939, and during 1942, he used the phrase in a poem, Basketball Ides of March. Through the years the use of March Madness increased, especially in Illinois, Indiana, and other parts of the Midwest. During this period the term was used almost exclusively in reference to state high school tournaments. During 1977, Jim Enright published a book about the Illinois tournament entitled March Madness.[67]

Fans began associating the term with the NCAA tournament during the early 1980s. Evidence suggests that CBS sportscaster Brent Musburger, who had worked for many years in Chicago before joining CBS, popularized the term during the annual tournament broadcasts. The NCAA has credited Bob Walsh of the Seattle Organizing Committee for starting the March Madness celebration in 1984.[68]

Only during the 1990s did either the IHSA or the NCAA think about trademarking the term, and by that time a small television production company named Intersport had already trademarked it. IHSA eventually bought the trademark rights from Intersport, and then went to court to establish its primacy. IHSA sued GTE Vantage, an NCAA licensee that used the name March Madness for a computer game based on the college tournament. During 1996, in a historic ruling, Illinois High School Association v. GTE Vantage, Inc., the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit created the concept of a "dual-use trademark", granting both the IHSA and NCAA the right to trademark the term for their own purposes.

After the ruling, the NCAA and IHSA joined forces and created the March Madness Athletic Association to coordinate the licensing of the trademark and investigate possible trademark infringement. One such case involved a company that had obtained the internet domain name marchmadness.com and was using it to post information about the NCAA tournament. During 2003, by March Madness Athletic Association v. Netfire, Inc., the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit decided that March Madness was not a generic term, and ordered Netfire to relinquish the domain name to the NCAA.[69]

Later during the 2000s, the IHSA relinquished its ownership share in the trademark, although it retained the right to use the term in association with high school championships. During October 2010, the NCAA reached a settlement with Intersport, paying $17.2 million for the latter company's license to use the trademark.[70]

This is a popular term for the regional semifinal round of the tournament, consisting of the final 16 teams. As in the case of "March Madness", this was first used by a high school federation—in this case, the Kentucky High School Athletic Association (KHSAA), which has used the term for decades to describe its own season-ending tournaments. It officially registered the trademark in 1988. Unlike the situation with "March Madness", the KHSAA has retained sole ownership of the "Sweet Sixteen" trademark; it licenses the term to the NCAA for use in collegiate tournaments.[71]

The Elite Eight is a popular term to describe the two teams in each of the four regional championship games. The NCAA officially uses the term for the eight-team final phase of the Division II men's and women's basketball tournaments. The winners of these games in the D-I tournament advance to the Final Four (the NCAA does not use the term "Final Four" in D-II). The NCAA trademarked this phrase in 1997. Like "March Madness," the phrase "Elite Eight" originally referred to the Illinois High School Boys Basketball Championship, the single-elimination high school basketball tournament run by the Illinois High School Association. In 1956, when the IHSA finals were reduced from sixteen to eight teams, a new nickname for Sweet Sixteen was needed, and Elite Eight won the vote. The IHSA trademarked the term in 1995; the trademark rights are now held by the March Madness Athletic Association, a joint venture between the NCAA and IHSA formed after a 1996 court case allowed both organizations to use "March Madness" for their own tournaments.

The term Final Four refers to the last four teams remaining in the playoff tournament. These are the champions of the tournament's four regional brackets, and are the only teams remaining on the tournament's final weekend. (While the term "Final Four" was not used during the early decades of the tournament, the term has been applied retroactively to include the last four teams in tournaments from earlier years, even when only two brackets existed.)

Some claim that the phrase Final Four was first used to describe the final games of Indiana's annual high school basketball tournament. But the NCAA, which has a trademark on the term, says Final Four was originated by a Plain Dealer sportswriter, Ed Chay, in a 1975 article that appeared in the Official Collegiate Basketball Guide.[72] The article stated that Marquette University "was one of the final four" of the 1974 tournament. The NCAA started capitalizing the term during 1978 and converting it to a trademark several years later.

During recent years, the term Final Four has been used for other sports besides basketball. Tournaments which use Final Four include the EuroLeague in basketball, national basketball competitions in several European countries, and the now-defunct European Hockey League. Together with the name Final Four, these tournaments have adopted an NCAA-style format in which the four surviving teams compete in a single-elimination tournament held in one place, typically, during one weekend. The derivative term "Frozen Four" is used by the NCAA to refer to the final rounds of the Division I men's and women's ice hockey tournaments. Until 1999, it was just a popular nickname for the last two rounds of the hockey tournament; officially, it was also known as the Final Four.

A Cinderella team, both in NCAA basketball and other sports, is one that achieves far greater success than would reasonably have been best expected.[73][74] In the NCAA tournament, teams may earn the Cinderella title after multiple wins in a single tournament against higher seeded teams. The term first came into widespread usage in 1950, when the City College of New York unexpectedly won the tournament in the same month that a film adaptation of Cinderella was released in the United States.

Notable Cinderella teams include North Carolina State in 1983 (the subject of a 30 for 30 documentary titled Survive and Advance), Villanova in 1985 (the lowest-seeded team to ever win the tournament), LSU in 1986 (the only team to defeat the top three seeds in their region in the same tournament), UMBC in 2018 (the first No. 16 seed to defeat a No. 1 seed), Saint Peter's in 2022 (the first No. 15 seed to advance to the Elite Eight), and Fairleigh Dickinson (the second 16 seed to defeat a 1 seed) and Florida Atlantic (a 9 seed which had never won an NCAA tournament game before its Final Four run) in 2023.[75]

And at one end of the court, there was Kevin Ware on his crutches, the net lowered to accommodate him and his crutches, making the final snip on the only nets Louisville has cut all season.