Los territorios de Ucrania ocupados por Rusia son áreas de Ucrania que actualmente están controladas por Rusia en el curso de la Guerra Ruso-Ucraniana . En la legislación ucraniana, se definen como los " territorios temporalmente ocupados de Ucrania " ( ucraniano : Тимчасово окупована територія України , romanizado : Tymchasovo okupovana terytoriia Ukrainy ).

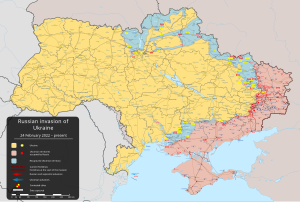

La ocupación comenzó en 2014 tras la invasión y anexión de la península de Crimea por parte de Rusia , y su toma de facto del Donbás de Ucrania [1] durante una guerra en el este de Ucrania . [2] En 2022, las fuerzas rusas iniciaron una invasión a gran escala de la nación y ocuparon con éxito más territorio en todo el país. Sin embargo, después de la continua y feroz resistencia ucraniana, junto con desafíos logísticos [3] ( por ejemplo , el convoy ruso estancado en Kiev ), las Fuerzas Armadas rusas anunciaron su retirada de los óblasts de Chernihiv , Kiev , Sumy y Zhytomyr a principios de abril. [4]

A principios de septiembre de 2022, las fuerzas ucranianas pusieron fin al estancamiento de meses en las líneas del frente con una contraofensiva exitosa en la región de Járkov , infligiendo una importante derrota a las fuerzas rusas al obligarlas a retirarse. [5] Luego, más tarde en noviembre, las fuerzas ucranianas volvieron a lograr un gran éxito con una contraofensiva en el sur recuperando la ciudad de Jersón el 11 de noviembre.

El 30 de septiembre de 2022, Rusia anunció la anexión de las provincias de Donetsk, Jersón, Luhansk y Zaporizhia , a pesar de ocupar solo una parte del territorio reclamado. La Asamblea General de la ONU respondió aprobando una resolución que rechazaba esta anexión por ilegal y defendía el derecho de Ucrania a la integridad territorial. [6] Se estima que aproximadamente 3 millones de ucranianos vivían en los territorios de Ucrania ocupados por Rusia en 2024, [7] en comparación con los 6,37 millones que residían allí antes de la invasión de 2022. [8]

Antes de 2022, Rusia ocupaba 42.000 km2 ( 16.000 millas cuadradas) de territorio ucraniano (Crimea y partes de Donetsk y Luhansk), y ocupó 119.000 km2 (46.000 millas cuadradas) adicionales después de su invasión a gran escala en marzo de 2022, un total de 161.000 km2 ( 62.000 millas cuadradas) o casi el 27% del territorio de Ucrania. [9] Para el 11 de noviembre de 2022, el Instituto para el Estudio de la Guerra calculó que las fuerzas ucranianas habían liberado un área de 74.443 km2 ( 28.743 millas cuadradas) de la ocupación rusa, [10] dejando a Rusia con el control de aproximadamente el 18% del territorio de Ucrania. [11] Durante todo el año 2023, las fuerzas rusas solo capturaron 518 km2 ( 200 millas cuadradas) de territorio ucraniano, a pesar de las enormes pérdidas en el campo de batalla. [12]

Con el Euromaidán y la Revolución de la Dignidad desde noviembre de 2013, las protestas populares en Ucrania llevaron a la destitución del presidente ucraniano prorruso Viktor Yanukovych por la Verkhovna Rada (el parlamento de Ucrania), mientras huía a Rusia. [13] El creciente sentimiento proeuropeo en el centro de este período de agitación causó malestar en el Kremlin , y el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin movilizó inmediatamente al ejército ruso y las fuerzas aerotransportadas para invadir Crimea , y rápidamente tomaron el control de los principales edificios gubernamentales y bloquearon al ejército ucraniano en sus bases en toda la península . [14] Poco después, los funcionarios instalados por Rusia anunciaron y llevaron a cabo un referéndum para que la región se uniera a Rusia , que las organizaciones occidentales e independientes etiquetaron como ilegítimo. [15] El Kremlin rechazó estas afirmaciones y pronto anexó oficialmente Crimea a Rusia , y las naciones occidentales emitieron sanciones contra Rusia en respuesta . [16] Además, con las contraprotestas prorrusas en el este y el sur de Ucrania en respuesta al derrocamiento de Yanukovych, [17] Rusia supuestamente apoyó a los separatistas militantes rusos y prorrusos en la región del Donbass para tomar el control de importantes edificios gubernamentales. [18] Estos separatistas finalmente crearon las Repúblicas Populares de Donetsk y Luhansk , [19] y desde entonces han estado en conflicto con el ahora proeuropeo gobierno ucraniano, conocido como la guerra en el Donbass (Rusia anunció su "anexión" después de la invasión rusa de Ucrania en 2022 ).

En respuesta a la intervención militar rusa , el Parlamento de Ucrania adoptó leyes gubernamentales (con posteriores actualizaciones y ampliaciones) para calificar a la República Autónoma de Crimea y partes de las regiones de Donetsk y Luhansk como territorios temporalmente ocupados y no controlados:

Petro Poroshenko , uno de los líderes de la oposición durante Euromaidán , obtuvo una victoria aplastante en las elecciones para suceder al presidente interino Turchynov, tres meses después del derrocamiento de Yanukovich. [23]

El siguiente gráfico resume algunas estimaciones de la superficie total del territorio ucraniano bajo control ruso, presentadas por varias editoriales en diferentes momentos durante el conflicto. Cabe señalar que algunas de las estimaciones de finales de 2022 eran contradictorias.

Desde que Rusia se anexionó Crimea en marzo de 2014 , administra la península bajo dos sujetos federales : la República de Crimea y la ciudad federal de Sebastopol . Ucrania sigue reclamando la península como parte integral de su territorio, lo que cuenta con el apoyo de la mayoría de los gobiernos extranjeros a través de la Resolución 68/262 de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas , [31] a pesar de que Rusia y algunos otros estados miembros de la ONU han expresado su apoyo al referéndum de Crimea de 2014, lo que implica el reconocimiento de Crimea como parte de la Federación Rusa. En 2015, el parlamento ucraniano fijó oficialmente el 20 de febrero de 2014 como la fecha del "inicio de la ocupación temporal de Crimea y Sebastopol por Rusia". [32]

Las partes no controladas de las provincias de Donetsk y Luhansk se abrevian comúnmente como " ORDLO " del ucraniano , especialmente entre los medios de comunicación ucranianos. ("ciertas áreas de las provincias de Donetsk y Luhansk", ucraniano : Окремі райони Донецької та Луганської областей , romanizado : Okremi raiony Donetskoi ta Luhanskoi oblastei ) [33] El término apareció por primera vez en la Ley de Ucrania No.1680-VII (octubre de 2014). [34] Los documentos del Protocolo de Minsk y la OSCE se refieren a ellas como "ciertas áreas de las regiones de Donetsk y Luhansk" (CADLR) de Ucrania. [35]

El Ministerio de Reintegración de Territorios Ocupados Temporalmente es el ministerio del gobierno ucraniano que supervisa la política gubernamental hacia las regiones. [36] En 2019 [update], el gobierno consideró que el 7% del territorio de Ucrania estaba bajo ocupación. [37] La resolución 73/194 de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas , adoptada el 17 de diciembre de 2018, designó a Crimea como bajo "ocupación temporal". [38]

En 2019, el ejército ucraniano se mostró preocupado por el despliegue de misiles de crucero 3M-54 Kalibr en buques de la marina y de la guardia costera rusa que operan en el mar de Azov , adyacente a los territorios ocupados temporalmente. Como resultado, Mariupol y Berdiansk , dos de los principales puertos marítimos de Priazovia , sufren un aumento de la inseguridad [39] (ambas ciudades fueron capturadas en 2022).

Supuestamente Temryuk y Taganrog , otros dos puertos del Mar de Azov, han sido utilizados para ocultar la procedencia de carbón antracita y gas natural licuado (GNL) de los territorios ocupados temporalmente. [39]

Desde el inicio de la guerra ruso-ucraniana en 2014, el Gobierno de Ucrania ha publicado (como ampliación de la orden gubernamental núm. 1085-р y la ley núm. 254-VIII) una "Lista de regiones y asentamientos ocupados temporalmente" y una "Lista de lugares de interés que bordean la zona de operaciones antiterroristas" actualizadas. [41] A partir del 16 de septiembre de 2020, el Gabinete de Ministros de Ucrania ha realizado cuatro actualizaciones a la orden núm. 1085-р y la ley núm. 254-VIII:

Los nombres de algunos asentamientos son el resultado de la descomunización de Ucrania en 2016. [49] [50]

La lista que figura a continuación se basa en la ampliación a partir del 7 de febrero de 2018. Las fronteras de algunas raiones han cambiado desde 2015.

Tras la invasión a gran escala de Rusia en febrero de 2022, el ejército ruso y las fuerzas rusas subordinadas a él ocuparon más territorio ucraniano. A principios de abril, las fuerzas rusas se retiraron del norte de Ucrania , incluida la capital , Kiev , [51] tras estancarse el avance en medio de una feroz resistencia ucraniana, para centrarse en consolidar el control sobre el este y el sur de Ucrania. El 2 de junio de 2022, Zelenski anunció que Rusia ocupaba aproximadamente el 20% del territorio ucraniano. [26]

El 27 de abril de 2023, Vladimir Putin emitió un decreto en virtud del cual los ciudadanos ucranianos de los territorios ocupados que se negaran a llevar un pasaporte ruso serían considerados extranjeros y deportados por ese motivo. El Defensor del Pueblo de Ucrania calificó esto como otro acto de genocidio . Al mismo tiempo, la Asamblea Parlamentaria del Consejo de Europa (APCE) reconoció la práctica de la deportación o el desplazamiento forzoso de niños ucranianos a Rusia como genocidio. [52]

La ocupación comenzó el 24 de febrero de 2022, inmediatamente después de que las tropas rusas invadieran Ucrania y comenzaran a apoderarse de partes del óblast de Járkov. Desde abril, las fuerzas rusas intentaron consolidar el control en la región y capturar la importante ciudad de Járkov después de su retirada del norte de Ucrania . Sin embargo, a mediados de mayo, las fuerzas ucranianas hicieron retroceder a los rusos hacia la periferia de la frontera rusa, [53] lo que indica que los ucranianos siguen encontrando una dura resistencia contra los avances rusos. A principios de septiembre de 2022, las fuerzas ucranianas comenzaron una importante contraofensiva y, para el 11 de septiembre de 2022, Rusia se había retirado de la mayoría de los asentamientos que ocupaba anteriormente en el óblast, [54] y el Ministerio de Defensa ruso anunció una retirada formal de las fuerzas rusas de casi todo el óblast de Járkov afirmando que estaba en marcha una "operación para reducir y transferir tropas". [55] [56]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Сергей_Кириенко_(08-04-2020)_(cropped).jpg)

El 24 de febrero de 2022, las tropas rusas de Crimea invadieron los raiones de Henichesk y Skadovsk . Durante los primeros días de la ofensiva, los rusos rodearon la mayoría de las ciudades y pueblos del óblast, bloqueando las entradas a ellos con barricadas, pero sin entrar en las ciudades mismas. Se libraron importantes batallas por el puente Antonivskyi , que cruza el río Dnipro entre las posiciones rusas en la orilla sur y la ciudad ucraniana de Jersón en la orilla norte. La abrumadora potencia de fuego del ejército ruso obligó a las fuerzas ucranianas a retirarse, y la ciudad cayó bajo control ruso el 2 de marzo . [58] El 29 de junio, las autoridades de ocupación rusas en el óblast de Jersón anunciaron los preparativos para la celebración de un referéndum de anexión . [59] El 9 de julio, el gobierno ucraniano anunció los preparativos para una contraofensiva inminente en el sur e instó a los residentes de las partes ocupadas de los óblasts de Jersón y Zaporizhia a refugiarse o evacuar para minimizar las bajas civiles en la operación. [60] Tras la destrucción del puente Antonivskyi y el avance de las tropas ucranianas desde el oeste, la falta de líneas de suministro sostenibles en medio de un intenso bombardeo ucraniano obligó a las fuerzas rusas a retirarse. Finalmente se retiraron de todas las áreas de la orilla norte del río Dniéper , incluida la ciudad de Jersón, que las fuerzas ucranianas recuperaron poco después, lo que se conoció como la liberación de Jersón .

.jpg/440px-Kherson_after_Russian_shelling,_2023-01-15_(02).jpg)

Distritos de la provincia de Jersón que están ocupados:

.jpg/440px-Zaporizhzhia_after_Russian_shelling,_2022-10-09_(41).jpg)

El 26 de febrero de 2022, la ciudad de Berdiansk quedó bajo control ruso, seguida de Melitopol el 1 de marzo tras feroces combates entre fuerzas rusas y ucranianas. Las tropas rusas también sitiaron y capturaron la ciudad de Enerhodar , donde se encuentra la central nuclear de Zaporizhia , que quedó bajo control ruso el 4 de marzo. Desde julio, han aumentado las tensiones en torno a la central eléctrica, ya que tanto Rusia como Ucrania se acusan mutuamente de ataques con misiles alrededor de la planta, [61] lo que provoca temores de una posible repetición del desastre de Chernóbil .

Distritos de la región de Zaporizhia que están ocupados:

Desde la invasión, el ejército ruso, junto con la República Popular de Donetsk respaldada por Rusia , aprovecharon las ganancias territoriales que habían obtenido durante la guerra en el Donbás y capturaron territorio adicional, el más significativo de los cuales fue el puerto de Mariupol , después de un asedio prolongado .

Hasta el 24 de febrero de 2022, se ocuparon las siguientes regiones de la región de Donetsk :

Después del 24 de febrero de 2022, fueron capturadas las siguientes regiones de la región de Donetsk:

Hasta el 24 de febrero de 2022, se ocuparon los siguientes distritos de la región de Luhansk :

Después del 24 de febrero de 2022, fueron capturadas las siguientes regiones de la región de Luhansk :

On July 3, 2022, the Russian military claimed that the entire Luhansk Oblast has been "liberated",[64] suggesting that Russian forces has succeeded in occupying the entire oblast and marked a major milestone for their goal of capturing the Donbas in Eastern Ukraine.

However, by September 19, Ukraine recaptured Bilohorivka.[65] By early October, Ukrainian forces liberated several more settlements as their counteroffensive operations shifted focus into the main territory of the oblast,[66] specifically the half north of the Siverskyi Donets in the Battle of the Svatove–Kreminna line. By May 2024, Ukraine had again lost control of Bilohorivka.[67]

The occupation of Mykolaiv Oblast began on February 26, 2022, with Russian troops crossing into the oblast through the Kherson Oblast from Crimea. In March, Russia attempted to advance towards Voznesensk, Mykolaiv and Nova Odesa, but were met with stiff resistance and failed. By May, Russia occupied Snihurivka, Tsentralne, Novopetrivka and numerous other small villages within the oblast. All these were retaken on 10–11 November 2022 during the Ukrainian counteroffensive, which followed the withdrawal of Russian troops from the right bank of the Dnieper.

Raions of Mykolaiv Oblast that are occupied:

.jpg/440px-President_of_Ukraine_presented_state_awards_to_the_Ukrainian_servicemen_who_liberated_the_Kherson_region._(52501682261).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Volodymyr_Zelenskyy_took_part_in_hoisting_the_State_Flag_of_Ukraine_in_liberated_Kherson._(52502133553).jpg)

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern campaign in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The occupying forces occupied a large part of the oblast, and eventually laid siege to the oblast capital, but failed to capture the city. Eventually, their stagnant progress led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

By April 2022, Russian troops began to secure towns north of Mariupol, most notably the Battle of Volnovakha, and completed the encirclement of Mariupol.[68] They then began to attack towns to the north, including starting the Battle of Velyka Novosilka.[69] As the Russians advanced, there were reports of clashes[by whom?] near Ternove, Novomykolaivka, Kalynivske, Berezove, Stepove and Maliivka, all in Synelnykove Raion, bordering Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk Oblasts, partially occupied by Russian forces. Ukrainian forces reported small battles near the Ternove area on 1 March.[70][citation not found] Ukrainian forces claimed to have cleared out Russian troops from the area on 14 March.[71][failed verification] These areas alongside Nikopol and Apostolove are still regularly shelled.[72][73][74] On 16 March, Russian forces spilled over from Kherson Oblast into Hannivka, reportedly occupying it.[75][better source needed] It was later liberated on 11 May.[76]

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Russian troops occupied a large part of the oblast, even approaching the borders of Kyiv city proper. However, the invaders' stagnant progress led to their failure to capture the Ukrainian capital, and eventually led to a complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

From 24 February to 30 June 2022, Russian forces occupied Snake Island in Odesa Oblast, but later withdrew after suffering heavy missile, artillery and drone strikes from the Ukrainian forces.[77]

During the battles of Lebedyn and Okhtyrka, Sumy Oblast, Russian forces spilled over and attacked Hadiach on 4 March 2022,[78][79][better source needed] and captured small areas around it, and advanced near Zinkiv and occupied Pirky on 3 March, but were repelled.[80][81] They were soon afterwards repelled which was known as the "Hadiach Safari", since people used shotguns and rifles to hunt for Russian soldiers.[82] Some notable areas captured were Pirky and Bobryk.[83]

Russia started the occupation as part of the northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Russian military occupied a large part of the oblast, but failed to take the oblast capital. Eventually, the stagnant progress of the Russian Ground Forces led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

Russia started the occupation as part of the Northern offensive in the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Russians occupied a small portion of the oblast, and never attempted to capture the oblast capital. Eventually, the culmination of the drive on Kyiv led to their complete withdrawal from the oblast by early April, ending the occupation.

United Nations special rapporteurs have condemned the Russian occupation authorities for attempting "to erase local [Ukrainian] culture, history, and language" and to forcibly replace it with Russian language and culture. Monuments and places of worship have been razed, while Ukrainian history books and literature deemed to be "extremist" have been seized from public libraries and destroyed. Civil servants and teachers have been detained for their refusal to implement Russian policy.[84] The International Court of Justice ruled that Russia had broken the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination by restricting school classes in the Ukrainian language in occupied Crimea.[85] Russia has been accused of neo-colonialism and colonization in Crimea by enforced Russification, passportization, and by settling Russian citizens on the peninsula and forcing out Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars.[86]

Russian armed forces committed widespread violations, including arbitrary detentions, torture and ill-treatment, looting of Ukrainian homes, and enforced disappearances. They did this under full impunity. Any person suspected of opposing the occupation was targeted. Peaceful protests and free expression were suppressed, whereas the freedom of movements was severely restricted.[87]

Following the liberation of occupied territories, thousands of civilians were accused of collaboration. They are tried by a single judge without a jury. The offense is punished by up to ten years of prison, with some of those convicted getting three or five years of prison. The accused include people who worked as volunteers and held administrative positions during the occupation.[88]

On 20 April 2016 Ukraine officially established government Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Internally Displaced Persons.[36] It was subsequently renamed the Temporarily Occupied Territories, IDPs and veterans and then the Ministry of Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories. The current minister is Iryna Vereshchuk, appointed on 4 November 2021.[89]

In March 2014, in a vote at the United Nations, 100 member states out of 193[90] did not recognize the annexation of the Crimea by Russia, with only Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Zimbabwe voting against the resolution[91] (see United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262).

The United Nations passed three resolutions regarding the issue of "human rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol", first in December 2016,[92] then again a year later in December 2017,[93] and lastly yet another in December 2018.

The UN's position according to the resolution adopted in 2018:

Condemning the ongoing temporary occupation of part of the territory of Ukraine, namely, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (hereinafter referred to as "Crimea"), by the Russian Federation, and reaffirming the non-recognition of its annexation[38]

In April 2018, PACE's emergency assembly recognized occupied regions of Ukraine as "territories under effective control by the Russian Federation".[94][95] Chairman of the Ukrainian delegation to PACE, MP Volodymyr Aryev mentioned that recognition of the fact that part of the occupied Donbas is under Russia's control is so important for Ukraine. "The responsibility for all the crimes committed in the uncontrolled territories is removed from Ukraine. Russia becomes responsible", Aryev wrote on Facebook.[96]

In early March 2022, in response to Russia's invasion, the United Nations General Assembly convened an emergency special session to discuss the latest developments regarding the peace situation in Ukraine, and adopted the United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1 to condemn Russia's invasion and Belarus's involvement.[97]

Territory under assessed Russian control or advances

approximately 43,133 sq km, or about 7.1% of Ukraine's area, is Russian occupied; the seized area includes all of Crimea and about one-third of both Luhans'k and Donets'k oblasts.