El asedio a la escuela de Beslán (también conocido como la crisis de los rehenes de la escuela de Beslán o la masacre de Beslán ) [2] [3] [4] fue un ataque rebelde que comenzó el 1 de septiembre de 2004. Duró tres días e implicó el encarcelamiento de más de 1.100 personas como rehenes (incluidos 777 niños) [5] y terminó con la muerte de 334 personas, 186 de ellas niños, [6] así como 31 de los atacantes [1] . Se considera el tiroteo escolar más mortífero de la historia. [7]

La crisis comenzó cuando un grupo de terroristas armados ocupó la Escuela Número Uno (SNO) en la ciudad de Beslan , Osetia del Norte (una república autónoma en la región del Cáucaso Norte de Rusia ) el 1 de septiembre de 2004. Los secuestradores eran miembros de Riyad-us Saliheen , enviados por el caudillo checheno Shamil Basayev , que exigía que Rusia se retirara y reconociera la independencia de Chechenia . Al tercer día del enfrentamiento, las fuerzas de seguridad rusas irrumpieron en el edificio.

El evento tuvo repercusiones políticas y de seguridad en Rusia, lo que llevó a una serie de reformas del gobierno federal que consolidaron el poder en el Kremlin y fortalecieron los poderes del Presidente de Rusia . [8] Las críticas a la gestión de la crisis por parte del gobierno ruso han persistido, incluidas acusaciones de desinformación y censura en los medios de comunicación, así como preguntas sobre la libertad periodística, [9] las negociaciones con los terroristas, la asignación de responsabilidad por el resultado final y el uso excesivo de la fuerza. [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

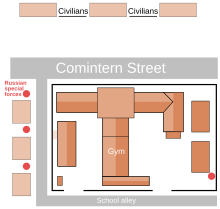

La Escuela Nº 1 era una de las siete escuelas de Beslán, una ciudad de unos 35.000 habitantes en la República de Osetia del Norte-Alania, en el Cáucaso ruso . La escuela, situada junto a la comisaría de policía del distrito, albergaba a unos 60 profesores y más de 800 estudiantes. [15] Su gimnasio, donde estuvieron retenidos la mayoría de los rehenes durante 52 horas, era una adición reciente, de 10 metros de ancho y 25 metros de largo. [16] Hubo informes de que hombres disfrazados de reparadores habían introducido armas y explosivos de contrabando en la escuela durante julio de 2004, un hecho que las autoridades negaron posteriormente. Sin embargo, varios testigos han declarado desde entonces que se vieron obligados a ayudar a sus captores a sacar las armas de los escondites ocultos en la escuela. [17] [18] También hubo afirmaciones de que se había instalado con antelación un "nido de francotiradores" en el tejado del pabellón de deportes. [19]

El ataque a la escuela tuvo lugar el 1 de septiembre, el inicio tradicional del año escolar ruso, conocido como "Primera campana" o Día del conocimiento . [20] [7]

En este día, los niños, acompañados de sus padres y otros familiares, asisten a ceremonias organizadas por su escuela. [21] Debido a las festividades del Día del Conocimiento, el número de personas en las escuelas fue considerablemente mayor de lo normal. Temprano en la mañana, un grupo de varias docenas de guerrilleros nacionalistas islámicos fuertemente armados abandonaron un campamento forestal ubicado en las cercanías de la aldea de Psedakh en la vecina República de Ingushetia , al este de Osetia del Norte y al oeste de Chechenia devastada por la guerra. Los terroristas llevaban camuflaje militar verde y pasamontañas negros , y en algunos casos también llevaban cinturones explosivos y ropa interior explosiva. En el camino a Beslan, en una carretera rural cerca de la aldea de Khurikau en Osetia del Norte, capturaron a un oficial de policía ingusetio, el Mayor Sultan Gurazhev. [22] Gurazhev fue abandonado en un vehículo después de que los terroristas llegaran a Beslan y luego corrió hacia el patio de la escuela [23] y fue al departamento de policía del distrito para informarles de la situación, añadiendo que le habían quitado su pistola de servicio y su placa. [24]

A las 09:11 hora local, los terroristas llegaron a Beslán en un furgón policial GAZelle y un camión militar GAZ-66 . Muchos testigos y expertos independientes afirman que había dos grupos de atacantes, y que el primer grupo ya estaba en la escuela cuando llegó el segundo grupo en camión. [25] Al principio, algunos en la escuela confundieron a los militantes con fuerzas especiales rusas practicando un simulacro de seguridad. [26] Sin embargo, los atacantes pronto comenzaron a disparar al aire y obligaron a todos los que estaban en el recinto de la escuela a entrar en el edificio. Durante el caos inicial, hasta 50 personas lograron huir y alertar a las autoridades sobre la situación. [27] Varias personas también lograron esconderse en la sala de calderas. [16] Después de un intercambio de disparos contra la policía y un civil local armado, en el que, según se informa, un atacante murió y dos resultaron heridos, los militantes tomaron el edificio de la escuela. [28] Los informes sobre el número de muertos en este tiroteo oscilaron entre dos y ocho personas, mientras que más de una docena de personas resultaron heridas.

Los atacantes tomaron aproximadamente 1.100 rehenes. [10] [29] El gobierno inicialmente minimizó el número de rehenes a un rango de 200 a 400, y luego, por una razón desconocida, anunció que eran exactamente 354. [9] En 2005, el total del gobierno se estimó en 1.128. [11] Los militantes llevaron a sus cautivos al gimnasio de la escuela y confiscaron todos sus teléfonos móviles bajo amenaza de muerte. [30] Ordenaron a los rehenes que hablaran en ruso y solo cuando se les hablara por primera vez. Cuando un padre llamado Ruslan Betrozov se puso de pie para calmar a la gente y repitió las reglas en el idioma local de Ossetic , un hombre armado se le acercó, le preguntó a Betrozov si había terminado y luego le disparó en la cabeza. Otro padre llamado Vadim Bolloyev, que se negó a arrodillarse, también recibió un disparo de un captor y luego se desangró hasta morir. [31] Sus cuerpos fueron arrastrados fuera del pabellón deportivo, dejando un rastro de sangre visible posteriormente en el vídeo realizado por los terroristas.

Después de reunir a los rehenes en el gimnasio, los atacantes seleccionaron a 15-20 adultos que pensaron que eran los más fuertes entre los maestros, empleados de la escuela y padres, y los llevaron a un pasillo al lado de la cafetería en el segundo piso, donde un cinturón explosivo en una de las mujeres bombarderas detonó, matando a otra mujer bombardera (también se afirmó que la segunda mujer murió por una herida de bala [32] ) y a varios de los rehenes seleccionados, además de herir mortalmente a un terrorista masculino. [33] A los rehenes sobrevivientes de este grupo se les ordenó que se tumbaran y otro pistolero les disparó con un rifle automático ; todos menos uno de ellos murieron. [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] Karen Mdinaradze, el camarógrafo del equipo FC Alania , sobrevivió a la explosión y al tiroteo; cuando se descubrió que todavía estaba vivo, se le permitió regresar al pabellón de deportes, donde perdió el conocimiento. [31] [39] Los militantes obligaron entonces a otros rehenes a arrojar los cuerpos fuera del edificio y a lavar la sangre del suelo. [40] Uno de estos rehenes, Aslan Kudzayev, escapó saltando por la ventana; las autoridades lo detuvieron brevemente como sospechoso de terrorismo. [31]

Pronto se estableció un cordón de seguridad alrededor de la escuela, formado por la policía rusa ( militsiya ), las tropas internas , las fuerzas del ejército ruso , Spetsnaz (incluidas las unidades de élite Alpha y Vympel del Servicio Federal de Seguridad de Rusia (FSB)) y las unidades especiales OMON del Ministerio del Interior de Rusia (MVD). Una línea de tres edificios de apartamentos frente al gimnasio de la escuela fue evacuada y tomada por las fuerzas especiales. El perímetro que formaron estaba a 225 metros (738 pies) de la escuela, dentro del alcance de los lanzagranadas de los militantes. [41] No había ningún equipo de extinción de incendios en posición y, a pesar de las experiencias previas de la crisis de los rehenes del teatro de Moscú de 2002 , había pocas ambulancias listas. [16] El caos se agravó por la presencia de milicianos voluntarios osetios ( opolchentsy ) y civiles armados entre la multitud que se había reunido en el lugar, [42] en total quizás hasta 5.000. [16]

Los atacantes minaron el gimnasio y el resto del edificio con artefactos explosivos improvisados (IED) y lo rodearon con cables trampa . En un intento adicional por disuadir los intentos de rescate, amenazaron con matar a 50 rehenes por cada uno de sus propios miembros asesinados por la policía, y matar a 20 rehenes por cada pistolero herido. [16] También amenazaron con volar la escuela si las fuerzas gubernamentales atacaban. Para evitar ser abrumados por un ataque con gas como lo fueron sus camaradas en la crisis de rehenes de Moscú de 2002, los insurgentes rápidamente rompieron las ventanas de la escuela. Los captores impidieron que los rehenes comieran y bebieran (llamándolo una " huelga de hambre ") hasta que el presidente de Osetia del Norte, Alexander Dzasokhov , llegara para negociar con ellos. [40] Sin embargo, el FSB estableció su propio cuartel general de crisis del que Dzasokhov fue excluido, y amenazó con arrestarlo si intentaba ir a la escuela. [10] [43]

El gobierno ruso anunció que no usaría la fuerza para rescatar a los rehenes, y las negociaciones para una resolución pacífica tuvieron lugar el primer y segundo día, lideradas al principio por Leonid Roshal , un pediatra a quien los secuestradores habían solicitado por su nombre. Roshal había ayudado a negociar la liberación de los niños en el asedio de Moscú de 2002, pero también había dado consejos a los servicios de seguridad rusos mientras se preparaban para asaltar el teatro, por lo que recibió el premio Héroe de Rusia . Sin embargo, la declaración de un testigo indicó que los negociadores rusos confundieron a Roshal con Vladimir Rushailo , un oficial de seguridad ruso. [44] Según el informe del miembro de la Duma Estatal Yuri Savelyev, el cuartel general oficial ("civil") buscaba una resolución pacífica mientras que el cuartel general secreto ("pesado") establecido por el FSB preparaba el asalto. Savelyev escribió que, en muchos sentidos, los "pesados" restringieron las acciones de los "civiles", en particular en sus intentos de negociar con los militantes. [45]

A petición de Rusia, el 1 de septiembre de 2004 por la tarde se convocó una reunión especial del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas , en la que los miembros del Consejo exigieron "la liberación inmediata e incondicional de todos los rehenes del ataque terrorista". [46] El presidente estadounidense George W. Bush hizo una declaración en la que ofrecía "apoyo en cualquier forma" a Rusia. [47]

El 2 de septiembre de 2004, las negociaciones entre Roshal y los militantes resultaron infructuosas, y se negaron a permitir que se llevara comida, agua o medicinas para los rehenes o que se retiraran los cadáveres de la parte delantera de la escuela. [31] Al mediodía, el primer subdirector del FSB, coronel general Vladimir Pronichev, mostró a Dzasokhov un decreto firmado por el primer ministro Mikhail Fradkov que nombraba al jefe del FSB de Osetia del Norte, el general de división Valery Andreyev, como jefe del cuartel general operativo. [48] Sin embargo, en abril de 2005 un periodista de Moscow News recibió fotocopias de los protocolos de las entrevistas de Dzasokhov y Andreyev realizadas por los investigadores, revelando que se habían formado dos cuarteles generales en Beslán: uno formal, sobre el que recaía toda la responsabilidad, y uno secreto ("pesados"), que tomaba las decisiones reales, y en el que Andreyev nunca había estado a cargo. [49]

El gobierno ruso restó importancia a las cifras, afirmando repetidamente que sólo había 354 rehenes; esto, al parecer, enfureció a los secuestradores, que maltrataron aún más a sus cautivos. [50] [51] Varios funcionarios también dijeron que parecía que sólo había entre 15 y 20 militantes en la escuela. [15] La crisis fue recibida con un silencio casi total por parte del presidente de Rusia, Vladimir Putin, y el resto de los líderes políticos de Rusia. [52] Sólo el segundo día Putin hizo su primer comentario público sobre el asedio durante una reunión en Moscú con el rey Abdullah II de Jordania : "Nuestra principal tarea, por supuesto, es salvar las vidas y la salud de los que se convirtieron en rehenes. Todas las acciones de nuestras fuerzas involucradas en el rescate de los rehenes se dedicarán exclusivamente a esta tarea". [53] Fue la única declaración pública de Putin sobre la crisis hasta un día después de que terminara. [52] En protesta, varias personas en el lugar levantaron carteles que decían: "¡Putin! ¡Libera a nuestros niños! ¡Atiende sus demandas!" y “¡Putin! ¡Hay al menos 800 rehenes!” Los lugareños también dijeron que no permitirían ningún asalto ni “envenenamiento de sus hijos” (en alusión a la crisis de los rehenes de Moscú con un agente químico ). [24]

Por la tarde, los hombres armados permitieron al ex presidente de Ingushetia Ruslan Aushev entrar en el edificio de la escuela y accedieron a entregarle personalmente a 11 mujeres lactantes y a los 15 bebés. [37] [54] Los hijos mayores de las mujeres se quedaron atrás y una madre se negó a irse, por lo que Aushev se llevó a su hijo más pequeño en su lugar. [34] Los terroristas le dieron a Aushev una cinta de vídeo grabada en la escuela y una nota con demandas de su supuesto líder, Shamil Basayev, que no estaba presente en Beslán. Las autoridades rusas mantuvieron en secreto la existencia de la nota, mientras que la cinta fue declarada vacía (lo que más tarde se demostró que era incorrecto). Se anunció falsamente que los militantes no habían hecho ninguna demanda. [10] En la nota, Basayev exigió el reconocimiento de una "independencia formal para Chechenia" en el marco de la Comunidad de Estados Independientes . También dijo que aunque los separatistas chechenos "no habían tenido ningún papel" en los atentados con bombas en los apartamentos rusos de 1999 , ahora asumirían públicamente la responsabilidad por ellos si fuera necesario. [10] Algunos funcionarios rusos y medios de comunicación controlados por el Estado criticaron posteriormente a Aushev por entrar en la escuela, acusándolo de conspirar con los terroristas. [55]

La falta de comida y agua afectó a los niños pequeños, muchos de los cuales se vieron obligados a permanecer de pie durante largos períodos en el gimnasio, que estaba abarrotado de gente y estaba caluroso. Muchos niños se desnudaron debido al calor sofocante que reinaba en el gimnasio, lo que dio lugar a falsos rumores de conducta sexual inapropiada. Muchos niños se desmayaron y sus padres temieron que murieran. Algunos rehenes bebieron su propia orina. De vez en cuando, los militantes (muchos de los cuales se quitaron las máscaras) sacaron a algunos de los niños inconscientes y les echaron agua en la cabeza antes de devolverlos al pabellón deportivo. Más tarde, algunos adultos también empezaron a desmayarse de cansancio y sed. Debido a las condiciones del gimnasio, cuando comenzó la explosión y el tiroteo al tercer día, muchos de los niños supervivientes estaban tan fatigados que apenas pudieron huir de la carnicería. [30] [56]

Alrededor de las 15:30, los militantes detonaron dos granadas contra las fuerzas de seguridad fuera de la escuela con aproximadamente diez minutos de diferencia, [57] incendiando un coche de policía e hiriendo a un oficial, [58] pero las fuerzas rusas no respondieron al fuego. A medida que avanzaba el día y la noche, la combinación de estrés y falta de sueño -y posiblemente abstinencia de drogas [59] [ ¿fuente poco fiable? ] - hizo que los secuestradores se volvieran cada vez más histéricos e impredecibles. El llanto de los niños los irritaba, y en varias ocasiones los niños que lloraban y sus madres fueron amenazados con dispararles si el llanto no cesaba. [26] Las autoridades rusas afirmaron que los terroristas habían escuchado al grupo alemán de heavy metal Rammstein en estéreos personales durante el asedio para mantenerse "nerviosos y entusiasmados". (Rammstein ya había sido objeto de críticas tras la masacre de la escuela secundaria de Columbine en 1999 , y de nuevo en 2007 tras el tiroteo de la escuela secundaria de Jokela ). [60]

Durante la noche, un policía resultó herido por disparos desde la escuela. Las conversaciones se interrumpieron y se reanudaron al día siguiente. [53]

Temprano en el tercer día, Ruslan Aushev, Alexander Dzasokhov, Taymuraz Mamsurov (presidente del parlamento de Osetia del Norte) y el primer vicepresidente Izrail Totoonti se pusieron en contacto con el presidente de la República Chechena de Ichkeria , Aslan Maskhadov . [43] Totoonti dijo que tanto Maskhadov como su emisario con base en Occidente, Akhmed Zakayev, declararon que estaban listos para volar a Beslan para negociar con los militantes, lo que luego fue confirmado por Zakayev. [61] Totoonti dijo que la única demanda de Maskhadov era su paso sin obstáculos a la escuela; sin embargo, el asalto comenzó una hora después de que se hiciera el acuerdo para su llegada. [62] [63] También mencionó que, durante tres días, los periodistas de la televisión Al Jazeera se ofrecieron a participar en las negociaciones y entrar a la escuela, incluso como rehenes, pero se les dijo que "sus servicios no eran necesarios para nadie". [64]

También se dijo que el asesor presidencial ruso, ex general de policía y de etnia chechena Aslambek Aslakhanov estaba cerca de lograr un avance en las negociaciones secretas. Cuando abandonó Moscú el segundo día, Aslakhanov había recopilado los nombres de más de 700 personalidades rusas conocidas que se habían ofrecido a entrar en la escuela como rehenes a cambio de la liberación de los niños. Aslakhanov dijo que los secuestradores habían acordado permitirle entrar en la escuela al día siguiente a las 15:00 horas. Sin embargo, el asalto había comenzado dos horas antes. [65]

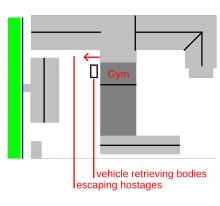

El 3 de septiembre, alrededor de las 13:00 horas, los militantes permitieron que cuatro trabajadores médicos del Ministerio de Situaciones de Emergencia, en dos ambulancias, retiraran 20 cadáveres del recinto escolar y llevaran el cadáver del terrorista asesinado a la escuela. Sin embargo, a las 13:03, cuando los paramédicos se acercaron a la escuela, se oyó una explosión en el gimnasio. Los terroristas abrieron fuego contra los paramédicos y mataron a dos de ellos. [40] Los otros dos se refugiaron detrás de su vehículo.

La segunda explosión, descrita como de "sonido extraño", se escuchó 22 segundos después. [16] A las 13:05, se inició un incendio en el techo del gimnasio y pronto las vigas y partes del techo en llamas cayeron sobre los rehenes que estaban abajo, muchos de los cuales estaban heridos pero todavía con vida. [45] Finalmente, todo el techo se derrumbó, llenando la habitación de fuego. Las llamas mataron a unas 160 personas, más de la mitad del total de rehenes muertos. [19]

Existen varias opiniones contradictorias sobre el origen y la naturaleza de las explosiones:

Las explosiones derribaron parte del muro del pabellón deportivo, lo que permitió que algunos rehenes escaparan. [16] Los militantes abrieron fuego y los militares respondieron. Varias personas murieron en el fuego cruzado. [76] Los funcionarios rusos afirman que los militantes dispararon a los rehenes mientras corrían y que los militares respondieron al fuego. [66] El gobierno afirmó que una vez que comenzó el tiroteo, las tropas no tuvieron más opción que asaltar el edificio. Sin embargo, algunos relatos de los residentes de la ciudad han contradicho esta versión oficial de los hechos. [77]

El teniente coronel de policía Elbrus Nogayev, cuya esposa e hija murieron en la escuela, dijo: "Escuché una orden que decía: '¡Dejen de disparar! ¡Dejen de disparar!', mientras que las radios de otras tropas decían: '¡Ataquen!'" [41]. Cuando comenzó la lucha, el presidente y negociador de la compañía petrolera, Mikhail Gutseriyev , de etnia ingusetio, llamó por teléfono a los secuestradores y escuchó: "¡Nos engañaron!" como respuesta. Cinco horas después, Gutseriyev y su interlocutor supuestamente tuvieron su última conversación, durante la cual el hombre dijo: "La culpa es suya y del Kremlin". [65]

Según Torshin, la orden de iniciar la operación la dio el jefe del FSB de Osetia del Norte, Valery Andreyev. [78] Sin embargo, las declaraciones tanto de Andreyev como de Dzasokhov indicaron que eran los subdirectores del FSB Vladimir Pronichev y Vladimir Anisimov quienes estaban realmente a cargo de la operación de Beslán. [63] El general Andreyev también dijo al Tribunal Supremo de Osetia del Norte que la decisión de utilizar armas pesadas durante el asalto la tomó el jefe del Centro de Operaciones Especiales del FSB, el coronel general Aleksandr Tikhonov. [79]

Se desató una batalla caótica cuando las fuerzas especiales lucharon por entrar en la escuela. Las fuerzas incluían los grupos de asalto del FSB y las tropas asociadas del Ejército ruso y el Ministerio del Interior ruso, apoyados por varios tanques T-72 del 58º Ejército de Rusia (requisados por Tikhonov al ejército el 2 de septiembre), vehículos blindados de transporte de personal con ruedas BTR-80 y helicópteros armados, incluido al menos un helicóptero de ataque Mi-24 . [80] Muchos civiles locales también se unieron a la batalla, habiendo traído sus propias armas, y se sabe que al menos uno de los voluntarios armados murió. El presunto criminal Aslan Gagiyev afirmó estar entre ellos. Al mismo tiempo, se informó que los soldados regulares reclutados huyeron del lugar cuando comenzó la lucha. Los testigos civiles afirmaron que la policía local también entró en pánico, a veces disparando en la dirección equivocada. [81] [82]

Al menos tres, pero hasta nueve, potentes cohetes Shmel fueron disparados contra la escuela desde las posiciones de las fuerzas especiales (tres [11] o nueve [83] tubos desechables vacíos fueron encontrados más tarde en los tejados de los bloques de apartamentos cercanos). El uso de los cohetes Shmel , clasificados en Rusia como lanzallamas y en Occidente como armas termobáricas , fue negado inicialmente, pero luego admitido por el gobierno. [13] [84] Un informe de un asistente del fiscal militar de la guarnición de Osetia del Norte afirmó que también se utilizaron granadas propulsadas por cohetes RPG-26 . [85] Los terroristas también utilizaron lanzagranadas, disparando contra las posiciones rusas en los edificios de apartamentos. [16]

Según un fiscal militar, un vehículo blindado BTR pasó cerca de la escuela y abrió fuego con su ametralladora pesada KPV de 14,5 × 114 mm contra las ventanas del segundo piso. [11] Testigos presenciales (entre ellos Totoonti [64] y Kesayev [74] ) y periodistas vieron a dos tanques T-72 avanzar hacia la escuela esa tarde, al menos uno de los cuales disparó su cañón principal de 125 mm varias veces. [11] Más tarde, durante el juicio, el comandante del tanque Viktor Kindeyev testificó que proporcionó el tanque a un oficial del FSB y alrededor de las 21:00 el tanque disparó "un tiro en blanco y seis proyectiles antipersonal de alto poder explosivo" por órdenes del FSB. [86] El uso de tanques y vehículos blindados de transporte de personal fue finalmente admitido por el teniente general Viktor Sobolev , comandante del 58.º Ejército. [80] Otro testigo citado en el informe de Kesayev afirma que había saltado sobre la torreta de un tanque en un intento de evitar que éste disparara contra la escuela. [74] Los militantes trasladaron a decenas de rehenes desde el pabellón deportivo en llamas a otras partes de la escuela, en particular a la cafetería, donde se les obligó a permanecer de pie junto a las ventanas como escudos humanos . Muchos de ellos fueron fusilados por las tropas que estaban fuera, según los supervivientes (entre ellos Kudzeyeva, [87] Kusrayeva [88] y Naldikoyeva [41] ). Savelyev estimó que entre 106 y 110 rehenes murieron tras ser trasladados a la cafetería. [89]

A las 15:00, dos horas después de que comenzara el asalto, las tropas rusas se hicieron con el control de la mayor parte de la escuela. Sin embargo, al caer la tarde, los combates continuaban en el recinto, incluida la resistencia de un grupo de militantes que se mantenían en el sótano de la escuela. [90] Durante la batalla, un grupo de unos 13 militantes rompió el cordón militar y se refugió en las cercanías. Se cree que varios de ellos entraron en un edificio local de dos pisos, que fue destruido por tanques y lanzallamas alrededor de las 21:00, según las conclusiones del comité osetio (Informe Kesayev). [91] Otro grupo de militantes pareció regresar por la vía férrea, perseguidos por helicópteros hacia la ciudad. [16]

Los bomberos, a los que Andreyev llamó dos horas después de que comenzara el incendio, [4] no estaban preparados para combatir el incendio que ardía en el gimnasio. Un equipo de bomberos llegó dos horas después por iniciativa propia, pero con sólo 200 litros de agua y no pudieron conectarse a los hidrantes cercanos. [11] [92] El primer camión cisterna llegó a las 15:28, casi dos horas y media después del inicio del incendio; [45] el segundo camión de bomberos llegó a las 15:43. [11] Había pocas ambulancias disponibles para transportar a los cientos de víctimas heridas, que en su mayoría fueron conducidas al hospital en coches particulares. [41] Se informó de que un presunto militante fue linchado en el lugar por una turba de civiles. [93] [ ¿ Fuente poco fiable? ] Un militante desarmado fue capturado vivo por las tropas OMON mientras trataba de esconderse debajo de un camión (más tarde fue identificado como Nur-Pashi Kulayev). [94] Algunos de los insurgentes muertos parecían haber sido mutilados por los comandos. [11]

Explosiones esporádicas y disparos continuaron durante la noche a pesar de los informes de que toda resistencia por parte de los militantes había sido suprimida, [95] hasta unas 12 horas después de las primeras explosiones. [96] Temprano al día siguiente, Putin ordenó cerrar las fronteras de Osetia del Norte mientras algunos de los terroristas aparentemente todavía estaban siendo perseguidos. [95]

Tras la conclusión de la crisis, muchos de los heridos murieron antes de que los pacientes fueran enviados a instalaciones mejor equipadas en Vladikavkaz , ya que el único hospital de Beslán no estaba preparado para tratar a las víctimas. [97] Había un suministro inadecuado de camas de hospital, medicamentos y equipo de neurocirugía. [98] A los familiares no se les permitió visitar los hospitales donde se trataba a los heridos y a los médicos no se les permitió utilizar sus teléfonos móviles. [99] [100]

Al día siguiente del asalto, las excavadoras recogieron los escombros del edificio, incluidos los restos de las víctimas, y los llevaron a un vertedero de basura. [10] [11] El primero de los numerosos funerales se celebró el 4 de septiembre, al día siguiente del asalto final, y poco después se celebraron más, incluido un entierro masivo de 120 personas. [101] El cementerio local era demasiado pequeño y tuvo que ampliarse a un terreno adyacente para dar cabida a los muertos. Tres días después del asedio, 180 personas seguían desaparecidas. [102] Muchos supervivientes quedaron gravemente traumatizados y al menos una ex rehén se suicidó tras volver a casa, poco después de identificar el cuerpo de su hijo. [103]

En su única visita a Beslán, Putin apareció durante un apresurado viaje al hospital de Beslán en las primeras horas del 4 de septiembre para ver a varias de las víctimas heridas. [104] Más tarde fue criticado por no reunirse con las familias de las víctimas. [95] Después de regresar a Moscú, ordenó un período de dos días de duelo nacional el 6 y el 7 de septiembre. En su discurso televisado, Putin dijo: "Hemos demostrado ser débiles. Y los débiles son golpeados". [40] En el segundo día de luto, se estima que 135.000 personas se unieron a una manifestación organizada por el gobierno contra el terrorismo en la Plaza Roja de Moscú. [105] En San Petersburgo, se estima que 40.000 personas se reunieron en la Plaza del Palacio . [106]

Después de la crisis, se introdujeron mayores medidas de seguridad en las ciudades rusas. Más de 10.000 personas sin los documentos adecuados fueron detenidas por la policía de Moscú en una "cacería de terroristas". El coronel Magomed Tolboyev , cosmonauta y Héroe de la Federación Rusa , fue atacado y brutalmente golpeado por una patrulla de la policía de Moscú debido a su nombre que sonaba a chechenio. [107] [108] El público ruso parecía apoyar en general el aumento de las medidas de seguridad; una encuesta de opinión del Centro Levada del 16 de septiembre de 2004 encontró que el 58% de los rusos apoyaba leyes antiterroristas más estrictas y la pena de muerte para el terrorismo, mientras que el 33% apoyaría prohibir a todos los chechenos entrar en las ciudades rusas. [109] [110]

A raíz de Beslán, el gobierno procedió a endurecer las leyes contra el terrorismo y a ampliar los poderes de los organismos encargados de hacer cumplir la ley. [8]

Además, Putin firmó una ley que sustituyó la elección directa de los jefes de los sujetos federales de Rusia por un sistema en el que son propuestos por el presidente de Rusia y aprobados o desaprobados por los órganos legislativos electos de los sujetos federales. [111] El sistema electoral para el parlamento ruso también fue modificado repetidamente, eliminando la elección de los miembros de la Duma Estatal por distritos de mandato único. [112] El Kremlin consolidó su control sobre los medios de comunicación rusos y atacó cada vez más a las organizaciones no gubernamentales (especialmente las fundadas en el extranjero). [113]

El ataque a Beslán tuvo más que ver con los ingusetios que con los chechenos, pero fue muy simbólico para ambas regiones. Los osetios y los ingusetios tienen un conflicto sobre la propiedad del distrito de Prigorodny que se avivó con las purgas estalinistas de 1944 y la limpieza étnica de los ingusetios llevada a cabo por los osetios en 1992-1993, con la ayuda del ejército ruso. En el momento del ataque, más de 40.000 refugiados ingusetios vivían en campamentos de tiendas de campaña en Ingushetia y Chechenia. [114] La propia escuela de Beslán había sido utilizada contra los ingusetios: en 1992, el gimnasio fue utilizado como corral para acorralar a los ingusetios durante la limpieza étnica llevada a cabo por los osetios. Para los chechenos, el motivo era la venganza por la destrucción de sus hogares y familias; Beslán fue uno de los lugares desde los que se lanzaron los ataques aéreos federales contra Chechenia. [115] [116]

Al enterarse de que un grupo terrorista en el que había chechenos había asesinado a muchos niños, muchos chechenos sintieron vergüenza. Un portavoz de la causa independentista chechena declaró: "No se nos podría haber asestado un golpe más fuerte... La gente de todo el mundo pensará que los chechenos son bestias y monstruos si pueden atacar a niños". [117]

El 7 de septiembre de 2004, las autoridades rusas declararon que habían muerto 334 personas, entre ellas 156 niños; en ese momento, 200 personas seguían desaparecidas o sin identificar. [118] El Informe Torshin afirmó que, en última instancia, no quedaba ningún cuerpo sin identificar. [119] Los lugareños afirmaron que más de 200 de los muertos fueron encontrados con quemaduras, y 100 o más de ellos fueron quemados vivos. [11] [41] En 2005, dos rehenes murieron a causa de las heridas sufridas en el incidente, al igual que un rehén en agosto de 2006. Una bibliotecaria de 33 años, Yelena Avdonina, sucumbió a un hematoma el 8 de diciembre de 2006. En ese momento, The Washington Post declaró que el número de muertos era de 334, excluyendo a los terroristas. [1] La ciudad de Beslán declara un número de muertos de 335 en su sitio web. [120] El número de muertos incluye a 186 niños. [6]

El ministro de Sanidad y Reforma Social de Rusia , Mijail Zurabov, dijo que el número total de heridos en la crisis superó los 1.200. [121] No se conoce el número exacto de personas que recibieron asistencia ambulatoria inmediatamente después de la crisis, pero se estima que fueron alrededor de 700 (753 según la ONU [5] ). El analista militar con sede en Moscú Pavel Felgenhauer concluyó el 7 de septiembre de 2004 que el 90% de los rehenes supervivientes habían sufrido heridas. Al menos 437 personas, incluidos 221 niños, fueron hospitalizadas; 197 niños fueron trasladados al Hospital Clínico Republicano Infantil en la capital de Osetia del Norte, Vladikavkaz, y 30 estaban en unidades de reanimación cardiopulmonar en estado crítico . Otras 150 personas fueron trasladadas al Hospital de Emergencias de Vladikavkaz. Sesenta y dos personas, incluidos 12 niños, fueron tratadas en dos hospitales locales de Beslán, mientras que seis niños con heridas graves fueron trasladados en avión a Moscú para recibir tratamiento especializado. [122] La mayoría de los niños fueron tratados por quemaduras, heridas de bala , heridas de metralla y mutilaciones causadas por explosiones. [123] A algunos les amputaron miembros y les quitaron ojos, y muchos niños quedaron discapacitados permanentemente. Un mes después del ataque, 240 personas (160 de ellas niños) seguían recibiendo tratamiento en hospitales de Vladikavkaz y Beslan. [122] [124] Los niños y padres supervivientes han recibido tratamiento psicológico en el Centro de Rehabilitación de Vladikavkaz. [125]

Uno de los rehenes, un profesor de educación física llamado Yanis Kanidis ( griego del Cáucaso , originario de Georgia ), que murió durante el asedio, salvó la vida de muchos niños. Una de las nuevas escuelas construidas en Beslán recibió posteriormente su nombre. [ cita requerida ]

La operación también se convirtió en la más sangrienta en la historia de las fuerzas especiales antiterroristas rusas. Diez miembros de las fuerzas especiales murieron (7 miembros de Vympel y 3 miembros de Alpha). [126] [127] Se cree que un comando llamado Vyacheslav Bocharov fue asesinado, pero resultó estar gravemente herido en la cara, pero estaba vivo cuando recuperó la conciencia y logró escribir su nombre. [128]

Entre las víctimas mortales se encontraban los tres comandantes de los grupos de asalto: el coronel Oleg Ilyin y el teniente coronel Dmitry Razumovsky de Vympel, y el mayor Alexander Perov de Alpha. [129] Al menos 30 comandos sufrieron heridas graves. [130]

En un principio, no estaba clara la identidad ni el origen de los atacantes. Desde el segundo día se asumió ampliamente que eran separatistas de la vecina Chechenia, aunque el ayudante checheno de Putin, Aslambek Aslakhanov, lo negó, diciendo que "no eran chechenos. Cuando empecé a hablar con ellos en checheno , me respondieron: 'No entendemos; hablemos ruso ' " . [131] Los rehenes liberados dijeron que los secuestradores hablaban ruso con acentos típicos de los caucásicos . [16]

Aunque Putin rara vez dudó en culpar a los separatistas chechenos por actos terroristas pasados, evitó vincular el ataque con la Segunda Guerra Chechena . En cambio, culpó de la crisis a la "intervención directa del terrorismo internacional", ignorando las raíces nacionalistas de la crisis. [132] Fuentes del gobierno ruso afirmaron inicialmente que nueve de los militantes en Beslán eran árabes y uno era un africano negro (llamado "un negro " por Andreyev), [133] [134] aunque solo dos árabes fueron identificados más tarde. [40] Analistas independientes como el comentarista político moscovita Andrei Piontkovsky dijeron que Putin trató de minimizar el número y la escala de los ataques terroristas chechenos en lugar de exagerarlos como lo había hecho en el pasado. [22] Putin pareció conectar los eventos con la Guerra contra el Terror liderada por Estados Unidos , [76] pero al mismo tiempo acusó a Occidente de consentir a los terroristas. [135]

On 17 September 2004, Chechen terrorist leader Shamil Basayev, operating autonomously from the rest of the North Caucasian terrorist movement, issued a statement claiming responsibility for the Beslan school siege, boasting that the siege only costed 8,000 euros.[136] The event was strikingly similar to the Chechen raid on Budyonnovsk in 1995 and the Moscow theatre hostage crisis of 2002, incidents in which hundreds of Russian civilians were held hostage by Chechen terrorists led by Basayev. Basayev said that his Riyad-us Saliheen "brigade of martyrs" had carried out the attack and also claimed responsibility for a series of terrorist bombings in Russia in the weeks before the Beslan crisis. He said that he had originally planned to seize at least one school in either Moscow or Saint Petersburg, but lack of funds forced him to pick North Ossetia, "the Russian garrison in the North Caucasus." Basayev blamed the Russian authorities for "a terrible tragedy" in Beslan.[137] Basayev claimed that he had miscalculated the Kremlin's determination to end the crisis by all means possible.[8] He said he was "cruelly mistaken" and that he was "not delighted by what happened there", but also added to be "planning more Beslan-type operations in the future because we are forced to do so."[138] However, it was the last major act of terrorism in Russia until 2009, as Basayev was soon persuaded to give up indiscriminate attacks by new Chechen leader Abdul-Halim Sadulayev,[139] who made Basayev his second-in-command but banned hostage-taking, kidnapping for ransom and operations specifically targeting civilians.[140]

Chechen separatist leader Aslan Maskhadov denied that his forces were involved in the siege, calling it "a blasphemy" for which "there is no justification". Maskhadov described the perpetrators of Beslan as "Madmen" driven out of their senses by Russian acts of brutality.[141] He condemned the action and all attacks against civilians via a statement issued by his envoy Akhmed Zakayev in London, blaming it on what he called a radical local group,[142] and he agreed to the North Ossetian proposition to act as a negotiator. Later, he also called on western governments to initiate peace talks between Russia and Chechnya and added to "categorically refute all accusations by the Russian government that President Maskhadov had any involvement in the Beslan event."[143] Putin responded that he would not negotiate with "child-killers",[106] comparing the calls for negotiations with the appeasement of Hitler,[135] and put a $10 million bounty on Maskhadov (the same amount as for Basayev).[144] Maskhadov was killed by Russian commandos in Chechnya on 8 March 2005[145] and buried at an undisclosed location.[146]

Shortly after the crisis, official Russian sources stated that the attackers were part of a supposed international group led by Basayev that included a number of Arabs with connections to al-Qaeda, and claimed that they had picked up phone calls in Arabic from the Beslan school to Saudi Arabia and another undisclosed Middle Eastern country.[147]

Two British-Algerians, Osman Larussi and Yacine Benalia, were initially named as having actively participated in the attack. Another UK citizen called Kamel Rabat Bouralha, arrested while trying to leave Russia immediately following the attack, was suspected to be a key organiser. All three were linked to the Finsbury Park Mosque of North London.[148] Allegations of al-Qaeda involvement were not repeated by the Russian government.[19] Larussi and Benalia are not named in the Torshin Report and were never identified by Russian authorities as suspects in the Beslan attack.[149]

The following people were named by the Russian government as planners and financiers of the attack:

In November 2004, 28-year-old Akhmed Merzhoyev and 16-year-old Marina Korigova of Sagopshi, Ingushetia were arrested by Russian authorities in connection with the Beslan attack. Merzhoyev was charged with providing food and equipment to the terrorists, and Korigova was charged with having possession of a phone that Tsechoyev had phoned multiple times.[151] Korigova was released when her defence attorney showed that she was given the phone by an acquaintance after the crisis.[152]

Russian negotiators say that the Beslan militants never explicitly stated their demands, although they did have notes handwritten by one of the hostages on a school notebook, in which they spelled out demands of full Russian troop withdrawal from Chechnya and recognition of Chechen independence.

The hostage-takers were reported to have made the following demands on 1 September 11:00–11:30 in a letter sent along with a hostage ER doctor:[153]

Dzasokhov and Zyazikov did not come to Beslan; Dzasokhov later claimed that he was forcibly stopped by "a very high-ranking general from the Interior Ministry [who] said, 'I have received orders to arrest you if you try to go'."[43] The stated reason why Zyazikov did not arrive was that he had been "sick".[65] Aushev, Zyazikov's predecessor at the post of Ingushetia's president, who was forced to resign by Putin in 2002, entered the school and secured the release of 26 hostages.

Aslakhanov said that the hostage-takers also demanded the release of some 28 to 30 suspects detained in the crackdown following the terrorist raids in Ingushetia earlier in June.[15][19]

Later, Basayev said the terrorists also demanded a letter of resignation from President Putin.[137]

According to the official version of events, 32 militants participated directly in the seizure, one of whom was taken alive while the rest were killed on the spot. The number and identity of hostage-takers remains a controversial topic, fuelled by the often-contradictory government statements and official documents. The 3–4 September government statements said that a total of 26–27 militants were killed during the siege.[95] At least four militants, including two women, died prior to the Russian storming of the school.

Many of the surviving hostages and eyewitnesses claim there were many more captors, some of whom may have escaped. It was also initially claimed that three terrorists were captured alive, including their leader Vladimir Khodov and a female militant.[154] Witness testimonies during the Kulayev trial reported the presence of a number of apparently Slavic-, unaccented Russian- and "perfect" Ossetian-speaking individuals among the militants who were not seen among the bodies of those killed by Russian security forces.[85] The unknown men (and a woman, according to one testimony) included a man with a red beard who was reportedly issuing orders to the kidnappers' leaders, and whom the hostages were forbidden to look at. He was possibly the militant known only as "Fantomas", an ethnic Russian who served as a bodyguard to Shamil Basayev.[19][85][155]

According to Basayev, "Thirty-three mujahideen took part in Nord-Ost. Two of them were women. We prepared four [women] but I sent two of them to Moscow on August 24. They then boarded the two airplanes that blew up. In the group there were 12 Chechen men, two Chechen women, nine Ingush, three Russians, two Arabs, two Ossetians, one Tartar, one Kabardinian and one Guran "[156]

Basayev further said an FSB agent (Khodov) had been sent undercover to the terrorists to persuade them to carry out an attack on a target in North Ossetia's capital, Vladikavkaz, and that the group was allowed to enter the region with ease because the FSB planned to capture them at their destination in Vladikavkaz. He also claimed that an unnamed hostage-taker had survived the siege and managed to escape.[13]

On 6 September 2004, the names and identities of seven of the assailants became known, after forensic work over the weekend and interviews with surviving hostages and a captured assailant. The forensic tests also established that 21 of the hostage-takers took heroin,[157] methamphetamine as well as morphine in a normally lethal amount;[158][159] the investigation cited the use of drugs as a reason for the militants' ability to continue fighting despite being badly wounded and presumably in great pain. In November 2004, Russian officials announced that 27 of the 32 hostage-takers had been identified. However, in September 2005, the lead prosecutor against Nur-Pashi Kulayev stated that only 22 of the 32 bodies of the captors had been identified,[160] leading to further confusion over which identities have been confirmed.

Most of the suspects, aged 20–35, were identified as Ingush or residents of Ingushetia (some of them Chechen refugees). At least five of the suspected hostage-takers were declared dead by Russian authorities before the seizure, while eight were known to have been previously arrested and then released, in some cases shortly before the Beslan attack.

The male hostage-takers were tentatively identified by the Russian government as:

In April 2005, the identity of the shahidka female militants was revealed:[182]

The captured suspect, 24-year-old Nur-Pashi Kulayev, born in Chechnya, was identified by former hostages as one of the hostage-takers. The state-controlled Channel One showed fragments of Kulayev's interrogation in which he said his group was led by a Chechnya-born man nicknamed Polkovnik and by the North Ossetia native Vladimir Khodov. According to Kulayev, Polkovnik shot another militant and detonated two female suicide bombers because they objected to capturing children.[183]

In May 2005, Kulayev was a defendant in a court in the Republic of North Ossetia. He was charged with murder, terrorism, kidnapping, and other crimes and pleaded guilty on seven of the counts;[184] many former hostages denounced the trial as a "smoke screen" and "farce".[55] Some of the relatives of the victims, who used the trial in their attempts to accuse the authorities, even called for a pardon for Kulayev so he could speak freely about what happened.[66] The director of the FSB, Nikolai Patrushev, was summoned to give evidence, but he did not attend the trial.[19] Ten days later, on 26 May 2006, Nur-Pashi Kulayev was sentenced to life imprisonment.[185] Kulayev later disappeared in the Russian prison system.[186] Following questions about whether Kulayev had been killed or died in prison, Russian government officials said in 2007 that he was alive and awaiting the start of his sentence.[187][clarification needed]

Family members of the victims of the attacks have accused the security forces of incompetence, and have demanded that authorities be held accountable. Putin personally promised to the Mothers of Beslan group to hold an "objective investigation". On 26 December 2005, Russian prosecutors investigating the siege on the school declared that authorities had made no mistakes whatsoever.[188]

At a press conference with foreign journalists on 6 September 2004, Vladimir Putin rejected the prospect of an open public inquiry, but cautiously agreed with an idea of a parliamentary investigation led by the State Duma, dominated by the pro-Kremlin parties.[189][190]

In November 2004, the Interfax news agency reported Aleksandr Torshin, head of the parliamentary commission, as saying that there was evidence of involvement by "a foreign intelligence agency" (he declined to say which).[191] On 22 December 2006, the Russian parliamentary commission ended their investigation into the incident. Their report concluded that the number of gunmen who stormed the school was 32 and laid much of the blame on the North Ossetian police, stating that there was a severe shortcoming in security measures, but also criticizing authorities for under-reporting the number of hostages involved.[192] In addition, the commission said the attack on the school was premeditated by Chechen terrorist leadership, including the moderate leader Aslan Maskhadov. In another controversial move, the commission claimed that the shoot-out that ended the siege was instigated by the hostage-takers, not security forces.[193] About the "grounded" decision to use flamethrowers, Torshin said that "international law does not prohibit using them against terrorists."[194] Ella Kesayeva, an activist who leads a Beslan support group, suggested that the report was meant as a signal that Putin and his circle were no longer interested in having a discussion about the crisis.[75]

On 28 August 2006, Duma member Yuri Savelyev, a member of the federal parliamentary inquiry panel, publicised his own report which he said proves that Russian forces deliberately stormed the school using maximum force. According to Savelyev, a weapons and explosives expert, special forces fired rocket-propelled grenades without warning as a prelude to an armed assault, ignoring apparently ongoing negotiations. In February 2007, two members of the commission (Savelyev and Yuri Ivanov) denounced the investigation as a cover-up, and the Kremlin's official version of events as fabricated. They refused to approve the Torshin's report.[73]

Three local policemen of the Pravoberezhny District ROVD (district militsiya unit) were the only officials put on trial over the massacre. They were charged with negligence in failing to stop gunmen seizing the school.[195] On 30 May 2007, the Pravoberezhny Court's judge granted an amnesty to them. In response, a group of dozens of local women rioted and ransacked the courtroom by smashing windows, overturning furniture, and tearing down a Russian flag. Victims' groups said the trial had been a whitewash designed to protect their superiors from blame.[196] The victims of the siege said they would appeal against the court judgement.[197]

In June 2007, a court in Kabardino-Balkaria charged two Malgobeksky District ROVD police officials, Mukhazhir Yevloyev and Akhmed Kotiyev, with negligence, accusing them of failing to prevent the attackers from setting up their training and staging camp in Ingushetia. The two pleaded innocent,[198] and were acquitted in October 2007. The verdict was upheld by the Supreme Court of Ingushetia in March 2008. The victims said they would appeal the decision to the European Court for Human Rights.[199]

The handling of the siege by Vladimir Putin's administration was criticised by a number of observers and grassroots organisations, amongst them Mothers of Beslan and Voice of Beslan.[200] Soon after the crisis, the independent MP Vladimir Ryzhkov blamed "the top leadership" of Russia.[201] Initially, the European Union also criticised the response.[202]

Critics, including Beslan residents who survived the attack and relatives of the victims, focused on allegations that the storming of the school was ruthless. They cite the use of heavy weapons, such as tanks and Shmel rocket flamethrowers.[80][203][204] Their usage was officially confirmed.[205] The Shmel is a type of thermobaric weapon, described by a source associated with the US military as "just about the most vicious weapon you can imagine – igniting the air, sucking the oxygen out of an enclosed area and creating a massive pressure wave crushing anything unfortunate enough to have lived through the conflagration."[11] Pavel Felgenhauer has gone further and accused the government of also firing rockets from an Mi-24 attack helicopter,[206] a claim that the authorities deny.[80] Some human rights activists claim that at least 80% of the hostages were killed by indiscriminate Russian fire.[10] According to Felgenhauer, "It was not a hostage rescue operation ... but an army operation aimed at wiping out the terrorists."[80] David Satter of the Hudson Institute said the incident "presents a chilling portrait of the Russian leadership and its total disregard for human life".[89]

The provincial government and police were criticised by the locals for having allowed the attack to take place, especially since police roadblocks on the way to Beslan were removed shortly before the attack.[207] Many blamed rampant corruption that allowed the attackers to bribe their way through the checkpoints; in fact, this was even what they had openly boasted to their hostages.[66][208][209] Others say the militants took the back roads used by smugglers in collusion with the police.[210] Yulia Latynina alleged that Major Gurazhev was captured after he approached the militants' truck to demand a bribe for what he thought was an oil-smuggling operation.[211] It was also alleged the federal police knew of the time and place of the planned attack; according to internal police documents obtained by Novaya Gazeta, the Moscow MVD knew about the hostage taking four hours in advance, having learned this from a militant captured in Chechnya.[10][212] According to Basayev, the road to Beslan was cleared of roadblocks because the FSB planned to ambush the group later, believing the terrorists' aim was to seize the parliament of North Ossetia in Vladikavkaz.

Critics also charged that the authorities did not organise the siege properly, including failing to keep the scene secure from entry by civilians,[213] while the emergency services were not prepared during the 52 hours of the crisis.[4] The Russian government has been also heavily criticised by many of the local people who, days and even months after the siege, did not know whether their children were alive or dead, as the hospitals were isolated from the outside world.[clarification needed] Two months after the crisis, human remains and identity documents were found by a local driver, Muran Katsanov,[11] in the garbage landfill at the outskirts of Beslan; the discovery prompted further outrage.[214][215]

In addition, there were serious accusations that federal officials had not earnestly tried to negotiate with the hostage-takers (including the alleged threat from Moscow to arrest President Dzasokhov if he came to negotiate) and deliberately provided incorrect and inconsistent reports of the situation to the media.

The report by Yuri Savelyev, a dissenting parliamentary investigator and one of Russia's leading rocket scientists, placed the responsibility for the final massacre on actions of the Russian forces and the highest-placed officials in the federal government.[216] Savelyev's 2006 report, devoting 280 pages to determining responsibility for the initial blast, concludes that the authorities decided to storm the school building, but wanted to create the impression they were acting in response to actions taken by the terrorists.[74][note 9] Savelyev, the only expert on the physics of combustion on the commission, accused Torshin of "deliberate falsification".[89]

A separate public inquiry by the North Ossetian parliament (headed by Kesayev) concluded on 29 November 2005 that both local and federal law enforcement mishandled the situation.[77]

On 26 June 2007, 89 relatives of victims lodged a joint complaint against Russia with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The applicants say their rights were violated both during the hostage-taking and the trials that followed.[198][217] The case was brought by over 400 Russians.[218]

In an April 2017 judgement that supported the prosecutors, the court deemed that Russia's failure to act on "sufficient" evidence about a likely attack on a North Ossetia school had violated the "Right to Life" guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights. The court stated the error was made worse by the Russian use of "indiscriminate force".[219] Result were published in April 2017, and found that Russian actions in using tank cannons, flame-throwers and grenade launchers "contributed to the casualties among the hostages", and had "not been compatible with the requirement under Article 2 that lethal force be used "no more than [is] absolutely necessary". The report also said that "The authorities had been in possession of sufficiently specific information of a planned terrorist attack in the area, linked to an educational institution", "nevertheless, not enough had been done to disrupt the terrorists meeting and preparing", or to warn schools or the public.[218][220][221]

The ECHR court in Strasbourg ordered Russia to pay €2.9 million in damages and €88,000 in legal costs. The Court's findings were rejected by the Russian Government.[218][222] Although obligated to accept the ruling because it is a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights, the Kremlin called the ruling "absolutely unacceptable".[219] The Russian government challenged it in a higher chamber: it argued that several of the court's conclusions were "not backed up", but ultimately agreed to the ruling after the complaints were rejected by the Strasbourg-based court.[223]

In opposition to the coverage on foreign television news channels (such as CNN and the BBC), the crisis was not broadcast live by the three major state-owned Russian television networks.[112] The two main state-owned broadcasters, Channel One and Rossiya, did not interrupt their regular programming following the school seizure.[201] After explosions and gunfire started on the third day, NTV Russia shifted away from the scenes of mayhem to broadcast a World War II soap opera.[52] According to the Ekho Moskvy ("Echo of Moscow") radio station, 92% of the people polled said that Russian TV channels concealed parts of information.[99]

Russian state-controlled television only reported official information about the number of hostages during the course of the crisis. The figure of 354 people was persistently given, initially reported by Lev Dzugayev (the press secretary of Dzasokhov)[note 10][224] and Valery Andreyev (the chief of the republican FSB). It was later claimed that Dzugayev only disseminated information given to him by "Russian presidential staff who were located in Beslan from September 1".[63] Torshin laid the blame squarely at Andreyev, for whom he reserved special scorn.[225]

The deliberately false figure had grave consequences for the treatment of the hostages by their angered captors (the hostage-takers were reported saying, "Maybe we should kill enough of you to get down to that number") and contributed to the declaration of a "hunger strike".[41][192] One inquiry has suggested that it may have prompted the militants to kill the group of male hostages shot on the first day.[225] The government disinformation also sparked incidents of violence by the local residents, aware of the real numbers, against the members of Russian and foreign media.[99]

On 8 September 2004, several leading Russian and international human-rights organisations – including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Memorial, and Moscow Helsinki Group – issued a joint statement in which they pointed out the responsibility that Russian authorities bore in disseminating false information:

We are also seriously concerned with the fact that authorities concealed the true scale of the crisis by, inter alia, misinforming Russian society about the number of hostages. We call on Russian authorities to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the circumstances of the Beslan events which should include an examination of how authorities informed the whole society and the families of the hostages. We call on making the results of such an investigation public."[99]

The Moscow daily tabloid Moskovskij Komsomolets ran a rubric headlined "Chronicle of Lies", detailing various initial reports put out by government officials about the hostage taking, which later turned out to be false.[106]

The late Novaya Gazeta journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who had negotiated during the 2002 Moscow siege, was twice prevented by the authorities from boarding a flight. When she eventually succeeded, she fell into a coma after being poisoned aboard an aeroplane bound for Rostov-on-Don.[99][226]

According to the report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), several correspondents were detained or otherwise harassed after arriving in Beslan (including Russians Anna Gorbatova and Oksana Semyonova from Novye Izvestia, Madina Shavlokhova from Moskovskij Komsomolets, Elena Milashina from Novaya Gazeta, and Simon Ostrovskiy from The Moscow Times). Several foreign journalists were also briefly detained, including a group of journalists from the Polish Gazeta Wyborcza, French Libération, and British The Guardian. Many foreign journalists were exposed to pressure from the security forces and materials were confiscated from TV crews ZDF and ARD (Germany), AP Television News (USA), and Rustavi 2 (Georgia). The crew of Rustavi 2 was arrested; the Georgian Minister of Health said that the correspondent Nana Lezhava, who had been kept for five days in the Russian pre-trial detention centers, had been poisoned with dangerous psychotropic drugs (like Politkovskaya, Lezhava had passed out after being given a cup of tea). The crew from another Georgian TV channel, Mze, was expelled from Beslan.[99]

Raf Shakirov, chief editor of the Russia's leading newspaper, Izvestia, was forced to resign after criticism by the major shareholders of both style and content of the issue of 4 September 2004.[227] In contrast to the less emotional coverage by other Russian newspapers, Izvestia had featured large pictures of dead or injured hostages. It also expressed doubts about the government's version of events.[228]

The video tape made by the hostage-takers and given to Ruslan Aushev on the second day was declared by the officials as being "blank".[229] Aushev himself did not watch the tape before he handed it to government agents. A fragment of tape shot by the hostage-takers was shown on Russian NTV television several days after the crisis.[230] Another fragment of a tape shot by the hostage-takers was acquired by media and publicised in January 2005.[34][208]

In July 2007, the Mothers of Beslan asked the FSB to declassify video and audio archives on Beslan, saying there should be no secrets in the investigation.[231] They did not receive any official answer to this request.[232] However, the Mothers received an anonymous video, which they disclosed saying it might prove that the Russian security forces started the massacre by firing rocket-propelled grenades on the besieged building.[233] The film had been kept secret by the authorities for nearly three years before being officially released by the Mothers on 4 September 2007.[234][235] The graphic film apparently shows the prosecutors and military experts surveying the unexploded shrapnel-based bombs of the militants and structural damage in the school in Beslan shortly after the massacre. Footage shows a large hole in the wall of the sports hall, with a man saying, "The hole in the wall is not from this [kind of] explosion. Apparently someone fired [there]", adding that many victims bear no sign of shrapnel wounds. In another scene filmed next morning, a uniformed investigator points out that most of the IEDs in the school actually did not go off, and then points out a hole in the floor which he calls a "puncture of an explosive character".[236]

In general, the criticism was rejected by the Russian government. President Vladimir Putin specifically dismissed the foreign criticism as Cold War mentality and said that the West wants to "pull the strings so that Russia won't raise its head."[112]

The Russian government defended the use of tanks and other heavy weaponry, arguing that it was used only after surviving hostages escaped from the school. However, this contradicts the eyewitness accounts, including by the reporters and former hostages.[237] According to the survivors and other witnesses, many hostages were seriously wounded and could not possibly escape by themselves, while others were kept by the terrorists as human shields and moved through the building.[58]

Deputy Prosecutor General of Russia Nikolai Shepel, acting as deputy prosecutor at the trial of the sole surviving attacker, found no fault with the security forces in handling the siege, "According to the conclusions of the investigation, the expert commission did not find any violations that could be responsible for the harmful consequences."[29][238] Shepel acknowledged that commandos fired flamethrowers, but said this could not have sparked the fire that caused most of the deaths;[84] he also said that the troops did not use napalm during the attack.[13]

To address doubts, in 2005 Putin launched a Duma parliamentary investigation led by Aleksandr Torshin,[239] resulting in the report which criticised the federal government only indirectly[240] and instead put blame for "a whole number of blunders and shortcomings" on local authorities.[241] The findings of the federal and the North Ossetian commissions differed widely in many main aspects.[74][242]

In 2005, previously unreleased documents by the national commission in Moscow were made available to Der Spiegel. According to the paper, "instead of calling for self-criticism in the wake of the disaster, the commission recommended the Russian government to crack down harder."[133]

Three local top officials resigned in the aftermath of the tragedy:[note 11][243]

Five Ossetian and Ingush police officers were tried in the local courts; all of them were subsequently amnestied or acquitted in 2007. As of December 2009, none of the Russian federal officials suffered consequences in connection with the Beslan events.

Nur-Pashi Kulayev, the sole survivor of the 32 attackers, claimed that attacking a school and targeting mothers and young children was not merely coincidental, but was deliberately designed for maximum outrage with the purpose of igniting a wider war in the Caucasus. According to Kulayev, the attackers hoped that the mostly Orthodox Ossetians would attack their mostly Muslim Ingush and Chechen neighbours to seek revenge, encouraging ethnic and religious hatred and strife throughout the North Caucasus.[247] North Ossetia and Ingushetia had previously been involved in a brief but bloody conflict in 1992 over disputed land in the North Ossetian Prigorodny District, leaving up to 1,000 dead and some 40,000 to 60,000 displaced persons, mostly Ingush.[40] Indeed, shortly after the Beslan massacre, 3,000 people demonstrated in Vladikavkaz calling for revenge against the ethnic Ingush.[40]

The expected backlash against neighbouring nations failed to materialise on a massive scale. In one noted incident, a group of ethnic Ossetian soldiers led by a Russian officer detained two Chechen Spetsnaz soldiers and executed one of them.[248] In July 2007, the office of the presidential envoy for the Southern Federal District Dmitry Kozak announced that a North Ossetian armed group engaged in abductions as retaliation for the Beslan school hostage-taking.[40][102][249] FSB Lieutenant Colonel Alikhan Kalimatov, sent from Moscow to investigate these cases, was shot dead by unidentified gunmen in September 2007.[250]

In September 2005, the self-proclaimed faith healer and miracle-maker Grigory Grabovoy claimed he could resurrect the murdered children. Grabovoy was arrested and indicted of fraud in April 2006, amidst the accusations that he was being used by the government as a tool to discredit the Mothers of Beslan group.[251]

In January 2008, the Voice of Beslan group, which in the previous year had been court-ordered to disband, was charged by Russian prosecutors with "extremism" for their appeals in 2005 to the European Parliament to help establish an international investigation.[204][252][253] This was soon followed with other charges, some of them relating to the 2007 court incident. As of February 2008, the group was charged in total of four different criminal cases.[254]

Russian Patriarch Alexius II's plans to build an Orthodox church as part of the Beslan monument caused a serious conflict between the Orthodox Church and the leadership of the Russian Muslims in 2007.[255] Beslan victims organisations also spoke against the project, and many in Beslan want the ruins of the school to be preserved, opposing the government plan to demolish them.[256]

The attack at Beslan was met with international abhorrence and universal condemnation. Countries and charities around the world donated to funds set up to assist the families and children that were involved in the Beslan crisis.

At the end of 2004, the International Foundation For Terror Act Victims had raised over $1.2 million with a goal of $10 million.[257] The Israeli government offered help in rehabilitating freed hostages, and during Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov's visit to China in November 2005, the Chinese Health Ministry announced that they were sending doctors to Beslan, and offered free medical care to any of the victims who still needed treatment.[258] The then mayor of Croatia's capital Zagreb, Vlasta Pavić, offered free vacations to the Adriatic Sea to the Beslan children.[259]

On 1 September 2005, UNICEF marked the first anniversary of the Beslan school tragedy by calling on all adults to shield children from war and conflict.[260]

Maria Sharapova and many other female Russian tennis players wore black ribbons during the 2004 US Open in memory of the tragedy.

In August 2005, two new schools were built in Beslan, paid for by the Moscow government.[261]

bringing the total death toll to 334, a Beslan activist said. ... Two other former hostages died of their wounds last year and another died last August, which had brought the overall death toll to 333 -- a figure that does not include the hostage-takers.

Of those who died, 186 were children.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)