Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif ( Urdu : میاں محمد نواز شریف ; nacido el 25 de diciembre de 1949) es un empresario y político paquistaní que se desempeñó como Primer Ministro de Pakistán durante tres mandatos no consecutivos. Es el Primer Ministro de Pakistán con más años en el cargo, habiendo servido un total de más de 9 años en tres mandatos. Cada mandato ha terminado con su destitución.

Nacido en la familia Sharif de clase media alta en Lahore , Nawaz es hijo de Muhammad Sharif , el fundador de los grupos Ittefaq y Sharif . Es el hermano mayor de Shehbaz Sharif , quien también se desempeñó como primer ministro de Pakistán de 2022 a 2023 y de 2024 al presente. Según la Comisión Electoral de Pakistán , Nawaz es uno de los hombres más ricos de Pakistán, con un patrimonio neto estimado de al menos 1.750 millones de rupias (equivalente a 8.900 millones de rupias o 31 millones de dólares estadounidenses en 2021). [1] La mayor parte de su riqueza proviene de sus negocios en la construcción de acero . [2]

Antes de entrar en política a mediados de la década de 1980, Nawaz estudió negocios en la Escuela de Gobierno y derecho en la Universidad de Punjab . En 1981, Nawaz fue nombrado por el presidente Zia como ministro de finanzas de la provincia de Punjab . Respaldado por una coalición informal de conservadores, Nawaz fue elegido como Ministro Principal de Punjab en 1985 y reelegido después del fin de la ley marcial en 1988. En 1990 , Nawaz lideró la conservadora Alianza Democrática Islámica y se convirtió en el duodécimo primer ministro de Pakistán.

Después de ser derrocado en 1993, cuando el presidente Ghulam Ishaq Khan disolvió la Asamblea Nacional , Nawaz sirvió como líder de la oposición al gobierno de Benazir Bhutto de 1993 a 1996. Regresó al cargo de primer ministro después de que la Liga Musulmana de Pakistán (N) (PML-N) fuera elegida en 1997 , y sirvió hasta su destitución en 1999 por toma de poder militar y fue juzgado en un caso de secuestro de avión que fue defendido por el abogado Ijaz Husain Batalvi, asistido por el abogado principal de Khawaja Sultan, Sher Afghan Asdi y el abogado Akhtar Aly Kureshy . Después de ser encarcelado y luego exiliado durante más de una década, regresó a la política en 2011 y llevó a su partido a la victoria por tercera vez en 2013. [3]

En 2017, Nawaz fue destituido de su cargo por la Corte Suprema de Pakistán debido a las revelaciones del caso de los Papeles de Panamá . [4] En 2018, la Corte Suprema de Pakistán inhabilitó a Nawaz para ejercer cargos públicos, [5] [6] y también fue sentenciado a diez años de prisión por un tribunal de rendición de cuentas . [7] Desde 2019, Nawaz se encontraba en Londres para recibir tratamiento médico bajo fianza. También fue declarado fugitivo por un tribunal paquistaní, sin embargo, el Tribunal Superior de Islamabad (IHC) le otorgó libertad bajo fianza hasta el 24 de octubre en los casos Avenfield y Al-Aziza. [8] [9] [10] En 2023, después de cuatro años de exilio, regresó a Pakistán. [11]

En un proceso judicial, un tribunal de primera instancia, integrado por el presidente del Tribunal Superior de Islamabad (IHC), Aamir Farooq, y el juez Miangul Hasan Aurangzeb, resolvió las apelaciones de Nawaz Sharif que impugnaban sus sentencias en los casos de las acerías Avenfield y Al-Azizia. El resultado de estos procedimientos fue la absolución del líder del PML-N, Nawaz Sharif, el 29 de noviembre de 2023, de los cargos relacionados con las referencias a los apartamentos Avenfield hechas por el IHC. [12]

Nawaz nació en Lahore, Punjab , el 25 de diciembre de 1949. [13] [14] La familia Sharif son cachemires de habla punjabi . [14] Su padre, Muhammad Sharif , era un empresario e industrial de clase media alta cuya familia había emigrado de Anantnag en Cachemira por negocios. Se establecieron en el pueblo de Jati Umra en el distrito de Amritsar , Punjab, a principios del siglo XX. La familia de su madre provenía de Pulwama . [15] Después de la creación de Pakistán en 1947, los padres de Nawaz emigraron de Amritsar a Lahore. [14] Su padre siguió las enseñanzas de Ahl-i Hadith . [16] Su familia es propietaria de Ittefaq Group , un conglomerado siderúrgico multimillonario, [17] y Sharif Group , un conglomerado con participaciones en agricultura, transporte y fábricas de azúcar. [18] Tiene dos hermanos menores: Shehbaz Sharif y el difunto Abbas Sharif , ambos políticos de profesión. [19]

Nawaz asistió a la escuela secundaria Saint Anthony . Se graduó en la Government College University (GCU) con un título en arte y negocios y luego recibió un título en derecho de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Punjab en Lahore . [20] [21]

Nawaz fue un jugador de críquet en sus primeros años, jugando como bateador de apertura . Peter Oborne señaló que tuvo éxito a nivel de club y que "estaba orgulloso de su récord de primera clase ", habiendo sido parte del equipo altamente calificado de Pakistan Railways en 1973-1974. Años más tarde, cuando era un político conocido, jugaría en partidos de preparación, para Lahore Gymkhana contra Inglaterra y como capitán temporal del equipo nacional contra las Indias Occidentales , ambos justo antes de la Copa del Mundo de 1987. Debido al partido de las Indias Occidentales, sorprendería a Imran Khan , entonces capitán regular, porque Nawaz abrió las entradas con una protección mínima contra uno de los ataques de bolos rápidos más temidos . [22]

La esposa de Nawaz Sharif, Kulsoom, tenía dos hermanas y un hermano. Por parte materna, era nieta del luchador The Great Gama (Ghulam Mohammad Baksh Butt). Se casó con Nawaz Sharif en abril de 1970. La pareja tiene cuatro hijos: Maryam , Asma, Hassan y Hussain.

Nawaz sufrió pérdidas financieras cuando el negocio siderúrgico de su familia fue confiscado en el marco de las políticas de nacionalización del ex primer ministro Zulfikar Ali Bhutto . Como resultado, Nawaz entró en política [14], inicialmente centrado en recuperar el control de las plantas siderúrgicas. En 1976, Nawaz se unió a la Liga Musulmana de Pakistán (PML), un frente conservador arraigado en la provincia de Punjab. [14]

En mayo de 1980, Ghulam Jilani Khan , el recientemente nombrado gobernador militar de Punjab y ex Director General de la Inteligencia Interservicios (ISI), estaba buscando nuevos líderes urbanos; rápidamente promovió a Nawaz, convirtiéndolo en ministro de finanzas . [23] En 1981, Nawaz se unió al Consejo Asesor de Punjab [20] bajo el mando de Khan. [23]

Durante la década de 1980, Nawaz ganó influencia como partidario del gobierno militar del general Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq . Zia-ul-Haq acordó devolver la industria del acero a Nawaz, quien convenció al general de desnacionalizar y desregular las industrias para mejorar la economía. [14] Dentro de Punjab, Nawaz privatizó industrias propiedad del gobierno y presentó presupuestos orientados al desarrollo al gobierno militar. [20] Estas políticas recaudaron capital financiero y ayudaron a aumentar el nivel de vida y el poder adquisitivo en la provincia, lo que a su vez mejoró la ley y el orden y extendió el gobierno de Khan. [14] Punjab era la provincia más rica y recibió más fondos federales que las otras provincias de Pakistán , lo que contribuyó a la desigualdad económica . [14]

Nawaz invirtió su riqueza en Arabia Saudita y otros países árabes ricos en petróleo para reconstruir su imperio del acero. [24] [25] Según relatos personales y el tiempo que pasó con Nawaz, el historiador estadounidense Stephen P. Cohen afirma en su libro de 2004 Idea of Pakistan : "Nawaz Sharif nunca perdonó a Bhutto después de que su imperio del acero se perdiera [...] incluso después del terrible final [de Bhutto] , Nawaz se negó públicamente a perdonar el alma de Bhutto o del Partido Popular de Pakistán ". [24]

En 1985, Khan nominó a Nawaz como Ministro Principal de Punjab, en contra de los deseos del Primer Ministro Muhammad Khan Junejo . [23] Con el respaldo del ejército, Nawaz consiguió una victoria aplastante en las elecciones de 1985. [14] Debido a su popularidad, recibió el apodo de "León del Punjab". [ 26] Nawaz construyó vínculos con los generales superiores del ejército que patrocinaron su gobierno. [20] Mantuvo una alianza con el general Rahimuddin Khan , presidente del Comité de Jefes de Estado Mayor Conjunto . Nawaz también tenía estrechos vínculos con el teniente general (retirado) Hamid Gul , director general del ISI. [14]

Como primer ministro, Nawaz hizo hincapié en las actividades de bienestar y desarrollo y en el mantenimiento de la ley y el orden. [20] Khan embelleció Lahore, amplió la infraestructura militar y silenció a la oposición política, mientras que Nawaz expandió la infraestructura económica para beneficiar al ejército, sus propios intereses comerciales y al pueblo de Punjab. [20] En 1988, el general Zia destituyó al gobierno de Junejo y convocó nuevas elecciones. [20] Sin embargo, Zia mantuvo a Nawaz como primer ministro de Punjab y, hasta su muerte , continuó apoyándolo. [20]

Después de la muerte del general Zia en agosto de 1988, su partido político, la Liga Musulmana de Pakistán (Grupo Pagara) , se dividió en dos facciones. [27] Nawaz lideró el Grupo Fida, leal a Zia, contra la Liga Musulmana de Pakistán (J) del Primer Ministro Junejo . [27] El Grupo Fida luego tomó el manto del PML mientras que el Grupo Junejo se conoció como JIP. [27] Los dos partidos, junto con otros siete partidos conservadores y religiosos de derecha, se unieron con el aliento y la financiación del ISI para formar el Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI). [27] (El IJI recibió ₨ 15 millones de los leales a Zia en el ISI, [28] con un papel sustancial desempeñado por el aliado de Nawaz, Gul. [14] ) La alianza fue liderada por Nawaz y Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi y se opuso al Partido Popular de Pakistán (PPP) de Benazir Bhutto en las elecciones. [27] El IJI obtuvo la mayoría en Punjab y Nawaz fue reelegido como primer ministro. [27]

En diciembre de 1989, Nawaz decidió permanecer en la Asamblea provincial de Punjab en lugar de mantener un escaño en la Asamblea Nacional. [29] A principios de 1989, el gobierno del PPP intentó derrocar a Nawaz mediante una moción de censura en la Asamblea de Punjab, [27] que perdió por 152 votos a 106. [27]

Los conservadores llegaron al poder por primera vez en un Pakistán democrático bajo el liderazgo de Nawaz. [30] Nawaz Sharif se convirtió en el duodécimo primer ministro de Pakistán el 1 de noviembre de 1990, sucediendo a Benazir Bhutto. También se convirtió en jefe del IJI. [30] Sharif tenía una mayoría en la asamblea y gobernó con considerable confianza, teniendo disputas con tres jefes sucesivos del ejército . [30]

Nawaz había hecho campaña con una plataforma conservadora y prometió reducir la corrupción gubernamental. [30] Nawaz introdujo una economía basada en la privatización y la liberalización económica para revertir la nacionalización de Zulfikar Bhutto, [24] en particular para los bancos y las industrias. [30] Legalizó el cambio de moneda extranjera para que se realizara a través de cambistas privados. [30] Sus políticas de privatización fueron continuadas tanto por Benazir Bhutto a mediados de la década de 1990 como por Shaukat Aziz en la década de 2000. [30] También mejoró la infraestructura de la nación y estimuló el crecimiento de las telecomunicaciones digitales. [30]

Nawaz continuó con la islamización y el conservadurismo simultáneos de la sociedad pakistaní, [30] una política iniciada por Zia. Se realizaron reformas para introducir el conservadurismo fiscal , la economía de la oferta , el bioconservadurismo y el conservadurismo religioso en Pakistán. [30]

Nawaz intensificó las controvertidas políticas de islamización de Zia e introdujo leyes islámicas como la Ordenanza Sharia y Bait-ul-Maal (para ayudar a los huérfanos pobres, las viudas, etc.) para impulsar al país según el modelo de un estado de bienestar islámico . [30] Además, encargó al Ministerio de Religión la preparación de informes y recomendaciones sobre los pasos a seguir hacia la islamización. Se aseguró de que se establecieran tres comités: [30]

Nawaz extendió la membresía de la Organización de Cooperación Económica (OCE) a todos los países de Asia Central para unirlos en un bloque musulmán. [30] Nawaz incluyó el ambientalismo en su plataforma de gobierno y estableció la Agencia de Protección Ambiental de Pakistán en 1997. [31]

Tras la imposición y aprobación de las resoluciones 660 , 661 y 665 , Nawaz se puso del lado de las Naciones Unidas en la invasión iraquí de Kuwait . [32] El gobierno de Nawaz criticó a Irak por invadir el país musulmán, lo que tensó las relaciones de Pakistán con Irak. [32] Esto continuó mientras Pakistán buscaba fortalecer sus relaciones con Irán . Esta política continuó bajo Benazir Bhutto y Pervez Musharraf hasta la eliminación de Saddam Hussein en 2003. [32] Nawaz planteó la cuestión de Cachemira en foros internacionales [ cita requerida ] y trabajó por una transferencia pacífica del poder en Afganistán [ cita requerida ] para frenar el comercio desenfrenado de drogas ilícitas y armas a través de la frontera. [30] [ cita requerida ]

Nawaz desafió al ex Jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército , el general Mirza Aslam Beg, por la Guerra del Golfo de 1991. [32] Bajo la dirección de Beg, las Fuerzas Armadas de Pakistán participaron en la Operación Tormenta del Desierto y el Grupo de Servicio Especial del Ejército y el Grupo de Servicio Especial Naval fueron desplegados en Arabia Saudita para brindar seguridad a la familia real saudí . [32]

Nawaz tuvo dificultades para trabajar con el PPP y el Movimiento Mutahidda Qaumi (MQM), una fuerza poderosa en Karachi. [33] El MQM y el PPP se opusieron a Nawaz debido a su enfoque en embellecer Punjab y Cachemira mientras descuidaba Sindh, [33] y el MQM también se opuso al conservadurismo de Nawaz. Aunque el MQM había formado gobierno con Nawaz, [33] las tensiones políticas entre el liberalismo y el conservadurismo estallaron en un conflicto entre facciones renegadas en 1992. [33]

Para poner fin a los combates entre el PML-N y el MQM, el partido de Nawaz aprobó una resolución para lanzar una operación paramilitar [33] bajo el mando del Jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército, el general Asif Nawaz Janjua . [32] La violencia estalló en Karachi en 1992 y paralizó la economía. [33] Durante este tiempo, Benazir Bhutto y el PPP de centroizquierda se mantuvieron neutrales, [33] pero su hermano Murtaza Bhutto ejerció presión que suspendió la operación. [33] El período de 1992-1994 es considerado [¿ por quién? ] el más sangriento en la historia de la ciudad, con muchas personas desaparecidas. [ cita requerida ]

Nawaz había hecho campaña con una plataforma conservadora [30] y después de asumir el cargo anunció su política económica bajo el Programa Nacional de Reconstrucción Económica (NERP). [30] Este programa introdujo un nivel extremo de economía capitalista de estilo occidental . [30]

El desempleo había limitado el crecimiento económico de Pakistán y Nawaz creía que sólo la privatización podría resolver este problema. [30] Nawaz introdujo una economía basada en la privatización y la liberalización económica , [24] en particular para los bancos y las industrias. [30] Según el Departamento de Estado de los EE.UU., esto siguió una visión de "convertir a Pakistán en una [ Corea del Sur] fomentando un mayor ahorro e inversión privados para acelerar el crecimiento económico". [34]

El programa de privatización revirtió la nacionalización de Zulfikar Ali Bhutto [24] y el PPP en la década de 1970. [35] Para 1993, alrededor de 115 industrias nacionalizadas se abrieron a la propiedad privada, [35] incluyendo la Corporación Nacional de Financiamiento para el Desarrollo , la Corporación Nacional de Transporte Marítimo de Pakistán , la Autoridad Nacional de Regulación de Energía Eléctrica , Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), la Corporación de Telecomunicaciones de Pakistán y Pakistan State Oil . [30] Esto impulsó la economía [30] pero la falta de competencia en las licitaciones permitió el surgimiento de oligarcas empresariales y amplió aún más la brecha de riqueza , contribuyendo a la inestabilidad política. [35] El ex asesor científico Dr. Mubashir Hassan calificó la privatización de Nawaz de "inconstitucional". [36] El PPP sostuvo que la política de nacionalización recibió estatus constitucional por parte del parlamento , y que las políticas de privatización eran ilegales y se habían llevado a cabo sin aprobación parlamentaria. [36]

Nawaz inició varios proyectos a gran escala para estimular la economía, como el Proyecto Hidroeléctrico Ghazi-Barotha . [30] Sin embargo, el desempleo siguió siendo un desafío. En un intento de contrarrestarlo, Nawaz importó miles de taxis amarillos privatizados para jóvenes paquistaníes, pero pocos de los préstamos fueron devueltos y Nawaz se vio obligado a pagarlos a través de su industria siderúrgica. [30] Los proyectos de Nawaz no se distribuyeron de manera uniforme, centrándose en las provincias de Punjab y Cachemira , la base de su apoyo, [36] con menores esfuerzos en las provincias de Khyber y Baluchistán , y sin beneficios de la industrialización en la provincia de Sindh . [30] Después de intensas críticas del PPP y MQM, Nawaz completó la Zona Industrial Orangi Cottage [30] pero esto no reparó su reputación en Sindh. [30] Los opositores acusaron a Nawaz de usar influencia política para construir fábricas para él y su negocio, [30] de expandir el conglomerado industrial secreto de las Fuerzas Armadas y de sobornar a los generales. [36]

Al mismo tiempo que privatizaba la industria, Nawaz tomó medidas para un intenso control gubernamental de la ciencia en Pakistán y puso proyectos bajo su autorización. [37] En 1991, Nawaz fundó y autorizó el Programa Antártico de Pakistán bajo la dirección científica del Instituto Nacional de Oceanografía (NIO), con la División de Ingeniería de Armas de la Armada de Pakistán , y estableció por primera vez la Estación Antártica Jinnah y la Célula de Investigación Polar. En 1992, Pakistán se convirtió en miembro asociado del Comité Científico de Investigación Antártica .

El 28 de julio de 1997, Nawaz declaró que 1997 sería el año de la ciencia en Pakistán y asignó fondos personalmente para la creación del 22º Colegio de Física Teórica del INSC. En 1999, Nawaz firmó el decreto ejecutivo que declaraba el 28 de mayo como el Día Nacional de la Ciencia en Pakistán.

Nawaz hizo del programa de armas y energía nuclear una de sus principales prioridades. [37] [38] Amplió el programa de energía nuclear y continuó un programa atómico [30] [37] mientras seguía una política de ambigüedad nuclear deliberada . [38]

Esto dio lugar a una crisis nuclear con los Estados Unidos, que endurecieron su embargo a Pakistán en diciembre de 1990 y, según se informa, ofrecieron una ayuda económica sustancial para detener el programa de enriquecimiento de uranio del país. [37] [38] En respuesta al embargo estadounidense, Nawaz anunció que Pakistán no tenía una bomba atómica y que firmaría el Tratado de No Proliferación Nuclear si la India también lo hacía. [38] El embargo bloqueó los planes para una planta de energía nuclear construida en Francia, por lo que los asesores de Nawaz presionaron intensamente al Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica (OIEA), que permitió a China establecer la planta de energía nuclear CHASNUPP-I y modernizar la KANUPP-I . [37]

La política nuclear de Nawaz fue considerada menos agresiva hacia la India, con su enfoque en el uso público a través de la energía nuclear y la medicina , vista como una continuación del programa estadounidense Átomos para la Paz . [¿ Por quién? ] En 1993, Nawaz estableció el Instituto de Ingeniería Nuclear (INE) para promover su política de uso pacífico de la energía nuclear.

Nawaz sufrió una importante pérdida de apoyo político a raíz del escándalo de las cooperativas. [30] Estas sociedades aceptan depósitos de sus miembros y pueden legalmente conceder préstamos sólo a los miembros para fines que beneficien a los mismos. [30] Sin embargo, la mala gestión condujo a un colapso que afectó a millones de paquistaníes en 1992. [30] En Punjab y Cachemira, alrededor de 700.000 personas perdieron sus ahorros y se descubrió que se habían concedido miles de millones de rupias al Grupo de Industrias Ittefaq , la acería de Nawaz. Aunque los préstamos se devolvieron rápidamente, la reputación de Nawaz se vio gravemente dañada. [30]

Nawaz había desarrollado serios problemas de autoridad con el presidente conservador Ghulam Ishaq Khan, quien había elevado a Nawaz a la prominencia durante la dictadura de Zia. [39] El 18 de abril, antes de las elecciones parlamentarias de 1993 , Khan utilizó sus poderes de reserva (58-2b) para disolver la Asamblea Nacional, y con el apoyo del ejército nombró a Mir Balakh Sher como primer ministro interino . Nawaz se negó a aceptar este acto y presentó un recurso ante la Corte Suprema de Pakistán . El 26 de mayo, la Corte Suprema dictaminó por 10 a 1 que la orden presidencial era inconstitucional, que el presidente podía disolver la asamblea solo si se había producido un colapso constitucional y que la incompetencia o corrupción del gobierno era irrelevante. [39] ( El juez Sajjad Ali Shah fue el único juez disidente; más tarde se convirtió en el 13.º presidente de la Corte Suprema de Pakistán . [40] [ ¿relevante? ] )

Los problemas de autoridad continuaron. En julio de 1993, bajo presión de las fuerzas armadas, Nawaz dimitió en virtud de un acuerdo que también destituía al presidente Khan del poder. El presidente del Comité de Jefes de Estado Mayor Conjunto , el general Shamim Allam , y el jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército, el general Abdul Vahied Kakar, obligaron a Khan a dimitir de la presidencia y pusieron fin al estancamiento político. Bajo la estrecha vigilancia de las Fuerzas Armadas del Pakistán, se formó un gobierno provisional y de transición y se celebraron nuevas elecciones parlamentarias al cabo de tres meses. [39]

Tras las elecciones de 1993 , el PPP volvió al poder bajo la dirección de Benazir Bhutto. Nawaz ofreció su plena cooperación como líder de la oposición, pero pronto el PPP y el PML-N mantuvieron al parlamento en un conflicto. A Bhutto le resultó difícil actuar con eficacia ante la oposición de Nawaz, y también enfrentó problemas en su bastión político de la provincia de Sindh por parte de su hermano menor Murtaza Bhutto . [39]

Nawaz y Murtaza Bhutto formaron el eje Nawaz-Bhutto y trabajaron para socavar el gobierno de Benazir Bhutto, aprovechando una ola anticorrupción en Pakistán. Acusaron al gobierno de corrupción con importantes corporaciones estatales y de ralentizar el progreso económico. En 1994 y 1995 realizaron una "marcha en tren" desde Karachi a Peshawar, pronunciando discursos críticos ante grandes multitudes. Nawaz organizó huelgas en todo Pakistán en septiembre y octubre de 1994. La muerte de Murtaza Bhutto en 1996, en la que supuestamente estaba involucrada la esposa de Benazir, provocó manifestaciones en Sindh y el gobierno perdió el control de la provincia. Benazir Bhutto se volvió muy impopular en todo el país y fue derrocada en octubre de 1996. [39]

En 1996, la continua corrupción a gran escala por parte del gobierno de Benazir Bhutto había deteriorado la economía del país, que estaba al borde del fracaso. [41] En las elecciones parlamentarias de 1997 , Nawaz y el PML-N obtuvieron una victoria abrumadora, con un mandato exclusivo en todo Pakistán. [41] [42] Se esperaba que Nawaz cumpliera sus promesas de proporcionar un gobierno conservador estable y mejorar las condiciones generales. [41] Nawaz juró como primer ministro el 17 de febrero. [43]

Nawaz había formado una alianza con Altaf Hussain del MQM que se desintegró tras el asesinato de Hakim Said . [33] Nawaz luego eliminó al MQM del parlamento y asumió el control de Karachi mientras que el MQM se vio obligado a pasar a la clandestinidad. [33] Esto llevó a Nawaz a reclamar un mandato exclusivo, y por primera vez Nawaz y el PML-N tuvieron el control de Sindh, Baluchistán, Frontera Noroeste, Cachemira y Punjab. [33] Con una supermayoría , el nuevo gobierno de Nawaz enmendó la constitución para restringir los poderes del presidente para destituir gobiernos. [44] Con la aprobación de la 14ª enmienda , Nawaz emergió como el primer ministro electo más poderoso del país. [41]

La popularidad de Nawaz alcanzó su punto máximo en mayo de 1998 [45] después de realizar las primeras pruebas de armas nucleares del país en respuesta a las pruebas de la India. [46] Cuando los países occidentales suspendieron la ayuda exterior , Nawaz congeló las reservas de divisas del país y las condiciones económicas empeoraron. [47] [48] El país se vio envuelto en conflictos en dos fronteras y las relaciones de larga data de Nawaz con el estamento militar se rompieron, de modo que a mediados de 1999 pocos aprobaban sus políticas. [49]

Durante las elecciones de 1997, Nawaz prometió seguir con su política de ambigüedad nuclear y al mismo tiempo utilizar la energía nuclear para estimular la economía. [50] Sin embargo, el 7 de septiembre, antes de una visita de Estado a los EE.UU., Nawaz reconoció en una entrevista con STN News que el país había tenido una bomba atómica desde 1978. Nawaz sostuvo que:

La cuestión de la capacidad [atómica] es un hecho establecido. [P]or lo tanto, el debate sobre esta cuestión [atómica] debería llegar a su fin [...] Desde 1972, [P]akistán ha avanzado significativamente, y hemos dejado esa etapa [de desarrollo] muy atrás. Pakistán no se convertirá en un "rehén" de la India por firmar el TPCE antes que [la India].

— Nawaz Sharif, 7 de septiembre de 1997 [50]

El 1 de diciembre, Nawaz dijo al Daily Jang y a The News International que Pakistán se convertiría inmediatamente en parte del Tratado de Prohibición Completa de los Ensayos Nucleares (TPCE) si la India lo firmaba y ratificaba primero. [50] Bajo su liderazgo, el programa nuclear se había convertido en una parte vital de la política económica de Pakistán. [37]

En mayo de 1998, poco después de las pruebas nucleares indias , Nawaz prometió que su país daría una respuesta adecuada. [51] El 14 de mayo, la líder de la oposición Benazir Bhutto y el MQM pidieron pruebas nucleares, seguidas por llamamientos del público. [52] Cuando la India probó sus armas nucleares por segunda vez, causó una gran alarma en Pakistán y aumentó la presión sobre Nawaz. El 15 de mayo, Nawaz puso a las fuerzas armadas en alerta máxima y convocó una reunión del Consejo de Seguridad Nacional , [52] discutiendo las preocupaciones financieras, diplomáticas, militares, estratégicas y de seguridad nacional. [52] Sólo el Ministro del Tesoro Sartaj Aziz se opuso a las pruebas, debido a la recesión económica, las bajas reservas de divisas y las sanciones económicas . [52]

Al principio, Nawaz dudaba del impacto económico de las pruebas nucleares, [53] y observó la reacción internacional a las pruebas de la India, donde un embargo no tenía ningún efecto económico. [53] El hecho de no realizar las pruebas pondría en duda la credibilidad de la disuasión nuclear de Pakistán, [52] lo que se enfatizó cuando el Ministro del Interior indio Lal Kishanchand Advani y el Ministro de Defensa George Fernandes se jactaron y menospreciaron a Pakistán, enfureciendo a Nawaz. [53]

El 18 de mayo, Nawaz ordenó a la Comisión de Energía Atómica de Pakistán (PAEC) que hiciera preparativos para las pruebas, [52] y puso a las fuerzas militares en alerta máxima para brindar apoyo. [47] El 21 de mayo, Nawaz autorizó pruebas de armas nucleares en Baluchistán. [53]

El 27 de mayo, el día antes de las pruebas, el ISI detectó a los cazas israelíes F-16 realizando ejercicios y recibió información de que tenían órdenes de atacar las instalaciones nucleares de Pakistán en nombre de la India. [54] Nawaz envió a la Fuerza Aérea de Pakistán y tenía bombas nucleares preparadas para su despliegue. Según el politólogo Shafik H. Hashmi, Estados Unidos y otras naciones aseguraron a Nawaz que Pakistán estaba a salvo; el ataque israelí nunca se materializó. [54]

El 28 y el 30 de mayo de 1998, Pakistán llevó a cabo con éxito sus pruebas nucleares, denominadas en código Chagai-I y Chagai-II . [47] [52] Después de estas pruebas, Nawaz apareció en la televisión nacional y declaró:

Si [Pakistán] hubiera querido, habría realizado pruebas nucleares hace 15 o 20 años [...] pero la pobreza abyecta de la población de la región disuadió a [... Pakistán] de hacerlo. Pero el [m]undio, en lugar de presionar a [India...] para que no tomara el camino destructivo [...] impuso todo tipo de sanciones a [Pakistán] sin culpa alguna [...] Si [Japón] hubiera tenido su propia capacidad nuclear [...] Hiroshima y Nagasaki no habrían sufrido la destrucción atómica a manos de [Estados Unidos].

— Nawaz Sharif, 30 de mayo de 1998, televisado en PTV [55]

El prestigio político de Nawaz alcanzó su punto máximo cuando el país se volvió nuclear. [45] A pesar de la intensa crítica internacional y la disminución de la inversión extranjera y el comercio, la popularidad interna de Nawaz aumentó, ya que las pruebas convirtieron a Pakistán en el primer país musulmán y la séptima nación en convertirse en una potencia nuclear . [52] Los editoriales estaban llenos de elogios para el liderazgo del país y abogaban por el desarrollo de la disuasión nuclear . [45] La líder de la oposición, Benazir Bhutto, felicitó a Nawaz por su "decisión audaz" a pesar de los resultados económicos, [55] y sintió que las pruebas borraron las dudas y los temores que preocupaban a la nación desde la guerra indo-paquistaní de 1971. [ 56] En la India, los líderes de la oposición en el parlamento culparon al gobierno de iniciar una carrera armamentista nuclear. [47] Nawaz fue galardonado con un premio Ig Nobel por sus "explosiones agresivamente pacíficas de bombas atómicas". [57] [ ¿relevante? ]

Nawaz construyó la primera gran autopista de Pakistán, la autopista M2 (3MM), llamada la Autopista del Sur de Asia. [30] Este proyecto público-privado se completó en noviembre de 1997 con un costo de 989,12 millones de dólares. [30] Sus críticos cuestionaron el diseño de la autopista, su excesiva longitud, su distancia de ciudades importantes y la ausencia de carreteras de enlace con ciudades importantes. También se apropió de fondos designados para la autopista del Indo Peshawar-Karachi, beneficiando a Punjab y Cachemira a costa de otras provincias. Hubo un descontento particular en las provincias de Sindh y Baluchistán, y Nawaz se enfrentó a una falta de inversión de capital para financiar proyectos adicionales. [30] Nawaz flexibilizó las restricciones cambiarias y abrió la Bolsa de Valores de Karachi al capital extranjero, pero el gobierno siguió sin fondos para inversiones. [30]

Debido a las presiones económicas, Nawaz detuvo el programa espacial nacional, lo que obligó a la Comisión de Investigación Espacial a retrasar el lanzamiento de su satélite, Badr-II(B) , que se completó en 1997. Esto provocó frustración entre la comunidad científica, que criticó la incapacidad de Nawaz para promover la ciencia. Los científicos e ingenieros de alto nivel atribuyeron esto a la "corrupción personal de Nawaz", que afectó a la seguridad nacional.

Al final del segundo mandato de Nawaz, la economía estaba en crisis. El gobierno se enfrentaba a graves problemas estructurales y financieros; la inflación y la deuda externa estaban en su nivel más alto, y el desempleo en Pakistán había alcanzado su punto más alto. Pakistán tenía deudas de 32.000 millones de dólares frente a reservas de poco más de 1.000 millones. El Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) había suspendido la ayuda, exigiendo que se resolvieran las finanzas del país. Nawaz siguió entrometiéndose en los mercados bursátiles con efectos devastadores. [49] Cuando fue depuesto, el país se encaminaba hacia una quiebra financiera.

El 20 de abril de 2015, el periódico Express Tribune afirmó que la administración de Sharif había engañado al Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) en relación con el impuesto que se cobraba por la emisión de acciones de bonificación, ya que lo que debería haber sido la mayor fuente de impuestos sobre la renta ascendía a apenas 1.000 millones de rupias . El gobierno había dicho al FMI que había aplicado un impuesto del 10%, que generaría unos ingresos equivalentes al 0,1% del PIB o29.000 millones de rupias . [58]

Nawaz fortaleció las relaciones de Pakistán con el mundo musulmán y Europa. [59]

En febrero de 1997, Nawaz se reunió con el presidente chino Jiang Zemin y el primer ministro Li Peng para discutir la cooperación económica. [59] Se organizaron dos conferencias en Beijing y Hong Kong para promover la inversión china en Pakistán. [59]

En 1997, Nawaz firmó un acuerdo de libre comercio trilateral con Malasia y Singapur, [59] al que siguió una colaboración en materia de defensa. [59] Uno de los temas centrales fue el acuerdo de Malasia de compartir su tecnología espacial con Pakistán. [59] Tanto Malasia como Singapur aseguraron su apoyo a que Pakistán se uniera a la Reunión Asia-Europa , [59] aunque Pakistán y la India no fueron partes del tratado hasta 2008. [59]

En enero de 1998, Nawaz firmó acuerdos económicos bilaterales con el presidente surcoreano Kim Young-sam . [59] Nawaz instó a Corea del Norte a hacer la paz y mejorar sus lazos con Corea del Sur, lo que provocó una división en las relaciones entre Pakistán y Corea del Norte. [59] En abril de 1998, Nawaz visitó Italia, Alemania, Polonia y Bélgica para promover los lazos económicos. [59] Firmó una serie de acuerdos para ampliar la cooperación económica con Italia y Bélgica, y un acuerdo con la Unión Europea (UE) para la protección de los derechos de propiedad intelectual, industrial y comercial. [59]

Sin embargo, los esfuerzos diplomáticos de Nawaz parecieron haber sido en vano después de realizar pruebas nucleares en mayo de 1998. Las críticas internacionales generalizadas llevaron la reputación de Pakistán a un mínimo desde la guerra indo-paquistaní de 1971. [ 59] Pakistán no logró reunir ningún apoyo de sus aliados en la ONU, [59] y los acuerdos comerciales fueron revocados por los EE. UU., Europa y el bloque asiático. [59] Pakistán fue acusado de permitir la proliferación nuclear. [59] En junio de 1998, Nawaz autorizó una reunión secreta entre Pakistán y los embajadores de Israel ante la ONU y los EE. UU., y aseguró al Primer Ministro israelí Benjamin Netanyahu que Pakistán no transferiría tecnología o materiales nucleares a Irán u otros países de Oriente Medio. [50] Israel respondió con preocupaciones de que la visita del Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores iraní Kamal Kharrazi a Pakistán poco después de las pruebas de armas nucleares de mayo de 1998 fuera una señal de que Pakistán se estaba preparando para vender tecnología nuclear a Irán. [50]

En 1998, India y Pakistán llegaron a un acuerdo que reconocía el principio de construir un ambiente de paz y seguridad y resolver todos los conflictos bilaterales. [60] El 19 de febrero de 1999, el primer ministro indio Atal Bihari Vajpayee realizó una histórica visita de Estado a Pakistán, viajando en el autobús inaugural Delhi-Lahore que conectaba la capital india con la principal ciudad cultural de Pakistán, Lahore. [60] El 21 de febrero, los primeros ministros firmaron un acuerdo bilateral con un memorando de entendimiento para garantizar la seguridad libre de armas nucleares en el sur de Asia, que se conoció como la Declaración de Lahore . [60] El acuerdo fue muy popular en ambos países, [60] donde se sintió que el desarrollo de armas nucleares trajo consigo una responsabilidad adicional y promovió la importancia de las medidas de fomento de la confianza para evitar el uso accidental o no autorizado de armas nucleares. [60] Algunos observadores occidentales compararon el tratado con las conversaciones sobre limitación de armas estratégicas de la guerra fría . [61]

A finales de agosto de 1998, Nawaz propuso una ley para establecer un sistema legal basado en los principios islámicos. [62] Su propuesta llegó una semana después de las conmemoraciones de los 10 años del difunto presidente Zia ul-Haq . Después de que su gabinete eliminara algunos de sus aspectos controvertidos, [63] [64] la Asamblea Nacional aprobó y aprobó el proyecto de ley el 10 de octubre de 1998 por una votación de 151 a 16. [65] Con una mayoría en el parlamento, Nawaz revirtió el sistema semipresidencial a favor de un sistema más parlamentario . [65] Con estas enmiendas, Nawaz se convirtió en el primer ministro libremente elegido más fuerte del país. [65] Sin embargo, estas enmiendas no lograron una mayoría de dos tercios en el Senado, que permaneció bajo el control del PPP. Semanas después, el parlamento fue suspendido por un golpe militar y la Orden del Marco Legal, 2002 (2002 LFO) devolvió al país a un sistema semipresidencial por otra década.

La Decimocuarta Enmienda de Nawaz consolidó su poder al impedir que los legisladores y legisladores disintieran o votaran en contra de sus propios partidos, [66] y prohibió la apelación judicial para los infractores. [66] Los legisladores de diferentes partidos desafiaron esto ante la Corte Suprema , enfureciendo a Nawaz. [66] Criticó abiertamente al presidente de la Corte Suprema Sajad Alishah , solicitando una notificación de desacato. [66] A instancias de los militares y el presidente, Nawaz aceptó resolver el conflicto amistosamente, pero siguió decidido a derrocar a Alishah. [66]

Nawaz manipuló las filas de los jueces superiores, destituyendo a dos jueces cercanos a Alishah. [66] Los jueces destituidos desafiaron las órdenes de Nawaz por motivos de procedimiento presentando una petición en el Tribunal Superior de Quetta el 26 de noviembre de 1997. [66] Alishah fue impedido por sus compañeros jueces de fallar en el caso contra el primer ministro. [66] El 28 de noviembre, Nawaz compareció ante el Tribunal Supremo y justificó sus acciones, citando evidencia contra los dos jueces destituidos. [66] Alishah suspendió la decisión del Tribunal Superior de Quetta, pero pronto el Tribunal Superior de Peshawar emitió órdenes similares destituyendo a los jueces más cercanos a Alishah. [66] El presidente asociado del Tribunal Superior de Peshawar, el juez Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui , se declaró presidente interino del Tribunal Supremo. [66]

Alishah siguió haciendo valer su autoridad y persistió en escuchar el caso de Nawaz. [66] El 30 de noviembre, los ministros del gabinete de Nawaz y un gran número de partidarios entraron en el edificio de la Corte Suprema, interrumpiendo los procedimientos. [66] El presidente de la Corte Suprema solicitó la presencia de la policía militar y, posteriormente, anuló la Decimotercera Enmienda , restaurando el poder del presidente. [66] Sin embargo, Nawaz, que contaba con el respaldo militar, se negó a obedecer las órdenes del presidente de destituirlo. [66] Nawaz obligó al presidente Farooq Leghari a dimitir y nombró a Wasim Sajjad como presidente interino, [66] luego derrocó a Alishah para poner fin a la crisis constitucional. [66]

El 29 de noviembre de 2006, Nawaz y el PML-N emitieron una disculpa formal por sus acciones a Alishah y Leghari. [67] Alishah recibió una disculpa escrita en su residencia y, más tarde, su partido emitió un libro blanco en el Parlamento en el que pedía disculpas formales por sus malas acciones. [68]

El 17 de agosto de 1997, Nawaz aprobó la controvertida Ley Antiterrorista , que establecía los Tribunales Antiterroristas . [41] Posteriormente, el Tribunal Supremo declaró inconstitucional la Ley. Sin embargo, Nawaz introdujo modificaciones y recibió el permiso del Tribunal Supremo para establecer dichos tribunales. [41]

Desde 1981 hasta 1999, Nawaz disfrutó de relaciones extremadamente cordiales con las Fuerzas Armadas de Pakistán, y fue el único líder civil de alto rango que tuvo relaciones amistosas con el estamento militar durante ese período. [14] Sin embargo, cuando el Jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército, General Jehangir Karamat, abogó por un Consejo de Seguridad Nacional , Nawaz lo interpretó como una conspiración para devolver al ejército un papel político activo. [14] [ aclaración necesaria ]

En octubre de 1998, tres meses antes de que terminara su mandato, Karamat se vio obligado a dimitir . [14] Esto fue polémico incluso dentro del gabinete de Nawaz [69] y fue visto como el momento menos popular de la administración de Nawaz. [70] Los abogados militares y los expertos en derecho civil vieron esto como inconstitucional y una violación del código de justicia militar . [70] Sin embargo, el Ministro de Medios Syed Mushahid Hussain sintió que Pakistán estaba "finalmente convirtiéndose en una sociedad democrática normal", no en deuda con sus militares. [71]

Nawaz promovió al general Pervez Musharraf para reemplazar a Karamat, [14] y también convirtió a Musharraf en presidente del Estado Mayor Conjunto a pesar de su falta de antigüedad. [14] El almirante Fasih Bokhari renunció como jefe del Estado Mayor Naval en protesta. [14] Bokhari presentó una protesta contra la debacle de Kargil y pidió que se sometiera a un tribunal militar a Musharraf, [68] [72] quien, según Nawaz, actuó solo. [73] [ se necesita más explicación ]

En agosto, la India derribó un avión de reconocimiento de la Armada de Pakistán en el Incidente del Atlántico , matando a 16 oficiales navales, [ cita requerida ] [74] el mayor número de bajas en combate para la armada desde la Guerra Naval Indo-Pakistaní de 1971. [ 74] Nawaz no logró obtener apoyo extranjero contra la India por el incidente, que el recién nombrado Jefe del Estado Mayor Naval, el almirante Abdul Aziz Mirza, consideró como una falta de apoyo a la armada en tiempos de guerra. [74] Nawaz perdió además la confianza de los marines por no defender a la armada en la Corte Internacional de Justicia (CIJ) en septiembre. [74] Las relaciones con la Fuerza Aérea también se deterioraron, cuando el Jefe del Estado Mayor del Aire, el general Parvaiz Mehdi Qureshi, acusó al primer ministro de no consultar a la fuerza aérea en asuntos críticos para la seguridad nacional. [75] [74]

Dos meses después, tras un empeoramiento constante de las relaciones con las Fuerzas Armadas, Nawaz fue depuesto por Musharraf y se estableció la ley marcial en todo el país. [74]

Los conflictos simultáneos en la guerra de Kargil con la India y la guerra civil de Afganistán , junto con la crisis económica, hicieron que la opinión pública se volviera contra Nawaz y sus políticas. El 12 de octubre de 1999, Nawaz intentó destituir a Musharraf por sus fracasos militares y reemplazarlo por el general Ziauddin Butt . La mentalidad de Nawaz era destituir primero al Presidente del Estado Mayor Conjunto y al Jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército, y luego destituir a los demás jefes de las fuerzas armadas que habían destruido su credibilidad. Musharraf, que estaba en Sri Lanka , intentó regresar en un vuelo comercial de PIA .

Nawaz ordenó a la Fuerza de Policía de Sindh que arrestara a Musharraf . Temiendo un golpe de estado , ordenó además que se sellara la Terminal Jinnah para evitar el aterrizaje del avión. Se ordenó al avión A300 que aterrizara en el aeropuerto de Nawabshah (ahora aeropuerto Shaheed Benazirabad). Allí, Musharraf se puso en contacto con los principales generales del Ejército de Pakistán que tomaron el control del país y derrocaron la administración de Nawaz. Nawaz fue llevado a la cárcel de Adiala para ser juzgado por un juez militar. [76] Musharraf asumió más tarde el control del gobierno como jefe ejecutivo. Sardar Mohsin Abbasi realizó una única protesta frente a la Corte Suprema el 17 de octubre en la primera audiencia de Nawaz.

Raja Zafar-ul-Haq , Sir Anjam Khan, Zafer Ali Shah y Sardar Mohsin Abbasi fueron los únicos partidarios que quedaron después de los primeros seis meses. Muchos de los ministros del gabinete de Nawaz y sus electores se mostraron divididos durante los procedimientos judiciales y se mantuvieron neutrales. Los disidentes como Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain se mantuvieron tranquilos y más tarde formaron la Liga Musulmana de Pakistán (PML-Q), dividiendo el partido de Nawaz en pequeñas facciones. La policía militar inició arrestos masivos de los trabajadores de la PML y los líderes del partido, que fueron retenidos en prisiones policiales de Sindh y Punjab. [76]

Los militares llevaron a Nawaz a juicio por "secuestro, intento de asesinato, secuestro ilícito, terrorismo y corrupción". [77] [78] En un juicio rápido, el tribunal militar condenó a Nawaz y le dio cadena perpetua. [78] Surgieron informes de que Nawaz casi había sido condenado a muerte. [77] [79] Su principal abogado defensor, Iqbal Raad , fue asesinado a tiros en Karachi a mediados de marzo. [80] El equipo de defensa de Nawaz culpó a los militares por proporcionar una protección inadecuada. [80] Los procedimientos del tribunal militar fueron ampliamente acusados de ser un juicio espectáculo . [81] [82] [83]

Nawaz también fue juzgado por evasión fiscal por la compra de un helicóptero valorado en un millón de dólares. El Tribunal Superior de Lahore accedió a absolverlo si podía demostrar su inocencia, pero Nawaz no pudo citar ninguna prueba sustancial. Se le ordenó pagar una multa de 400.000 dólares por evasión fiscal y fue condenado a 14 años de prisión. [84]

Pakistán y Arabia Saudita, bajo Nawaz y el rey Fahd, habían disfrutado de relaciones comerciales y culturales extremadamente estrechas que a veces se atribuyen como una relación especial . [79] Arabia Saudita se sorprendió con la noticia del golpe. [79] En medio de la presión de Fahd y el presidente estadounidense Bill Clinton , el tribunal militar evitó una sentencia de muerte para Sharif. [79] Fahd había expresado su preocupación de que la sentencia de muerte provocaría una intensa violencia étnica en Pakistán como había sucedido en la década de 1980 [79] después de la ejecución de Zulfikar Ali Bhutto . [77] En virtud de un acuerdo facilitado por Arabia Saudita, Nawaz fue puesto en exilio durante los siguientes 10 años, [79] y acordó no participar en la política en Pakistán durante 21 años. También confiscó propiedades por valor de US$8,3 millones (£5,7 millones) y pagó una multa de US$500.000. [85] Musharraf escribió en sus memorias que, sin la intervención de Fahd, Sharif habría sido ejecutado. [86] Nawaz viajó a Jeddah , Arabia Saudita, donde fue llevado a una residencia administrada y controlada por el gobierno saudí, [79] y le proporcionaron un préstamo saudí para establecer una fábrica de acero. [79]

El 23 de agosto de 2007, la Corte Suprema de Pakistán dictaminó que Nawaz y su hermano, Shehbaz Sharif , eran libres de regresar a Pakistán. Ambos prometieron regresar pronto. [87] [88] El 8 de septiembre, el político libanés Saad Hariri y el jefe de inteligencia saudí, el príncipe Muqrin bin Abdul-Aziz, celebraron una conferencia de prensa conjunta sin precedentes en el Cuartel General de los Combatientes del Ejército (GHQ) para discutir cómo afectaría a las relaciones el regreso de Nawaz. Muqrin expresó su esperanza de que Nawaz mantuviera el acuerdo de no regresar durante 10 años, pero dijo que "estas pequeñas cosas no afectan a las relaciones". [89]

Dos días después, Nawaz regresó de su exilio en Londres [89] a Islamabad . Se le impidió bajar del avión y fue deportado a Yeddah, Arabia Saudita, en cuestión de horas [90] . Su carrera política parecía haber terminado [43] .

Musharraf viajó a Arabia Saudita el 20 de noviembre de 2007, la primera vez que salía de Pakistán desde que se implementó el estado de emergencia. [91] [ contradictorio ] Intentó convencer a Arabia Saudita de que impidiera el regreso de Nawaz hasta después de las elecciones de enero de 2008. [91] Nawaz había adquirido mayor relevancia política tras el regreso a Pakistán de Benazir Bhutto, que también había estado exiliada. [91] Arabia Saudita sugirió que si Pakistán había permitido que una mujer líder democrática-socialista, Bhutto, regresara al país, entonces también se debería permitir el regreso del conservador Nawaz. [91]

Nawaz regresó a Pakistán cinco días después. Miles de seguidores silbaron y vitorearon mientras cargaban a Nawaz y a su hermano sobre sus hombros. [92] Después de una procesión de 11 horas desde el aeropuerto, llegó a una mezquita donde ofreció oraciones y criticó a Musharraf. [93] Su regreso a Pakistán le permitió sólo un día para registrarse para las elecciones, lo que preparó el terreno para un cambio de la escena política de la noche a la mañana. [92]

Nawaz hizo un llamamiento al boicot de las elecciones de enero de 2008 porque creía que no serían justas, dado el estado de emergencia impuesto por Musharraf. Nawaz y el PML-N decidieron participar en las elecciones parlamentarias después de que 33 grupos de la oposición, incluido el PPP de Bhutto, se reunieran en Lahore pero no lograran alcanzar una posición conjunta. [94] Hizo campaña por la restauración de los jueces independientes destituidos por el decreto de emergencia del gobierno y la salida de Musharraf. [95] [96]

El asesinato de Bhutto provocó el aplazamiento de las elecciones hasta el 18 de febrero de 2008. [97] Nawaz condenó el asesinato de Bhutto y lo calificó como el "día más sombrío en la historia de Pakistán". [98] A medida que se acercaban las elecciones, el país se enfrentaba a un aumento de los ataques de los militantes. [99] Nawaz acusó a Musharraf de ordenar operaciones antiterroristas que habían dejado al país "ahogado en sangre". [99] El gobierno de Pakistán instó a los líderes de la oposición a abstenerse de celebrar manifestaciones antes de las elecciones, citando una amenaza terrorista en aumento. [99] El PML-N rechazó esto, acusando a los funcionarios de interferencia en la campaña. [99]

El 25 de enero, Musharraf intentó la mediación británica para reconciliarse con los hermanos Nawaz, pero fracasó. [100] Las elecciones estuvieron dominadas [ aclaración necesaria ] por el PPP, impulsado por la muerte de Bhutto, y el PML-N. En la Asamblea Nacional de 342 escaños, el PPP obtuvo 86 escaños; el PML-N, 66; y el PML-Q, que apoyó a Musharraf, 40. [101]

El partido de Nawaz se había unido a una coalición con el PPP, liderada por su nuevo líder Asif Ali Zardari, pero la alianza se vio afectada por las diferencias. [102] Nawaz obtuvo un gran apoyo público por su postura intransigente, [102] y la coalición logró forzar la renuncia de Musharraf a la presidencia. Después del colapso de la coalición, Nawaz presionó a Zardari para que restituyera a los jueces que Musharraf había destituido durante el estado de emergencia. Esto llevó a que los tribunales absolvieran los antecedentes penales de Nawaz para que pudiera volver a entrar en el parlamento. [103]

En las elecciones parciales de junio de 2008, el partido de Nawaz ganó 91 escaños en la Asamblea Nacional y 180 en la Asamblea Provincial del Punjab. [104] La elección para el escaño de Lahore se pospuso debido a dudas sobre la elegibilidad de Nawaz para presentarse como candidato. [102] [105]

El 7 de agosto de 2008, el gobierno de coalición acordó destituir a Musharraf. Zardari y Nawaz enviaron una solicitud formal para que dimitiera. Se había redactado un pliego de cargos que debía presentarse al Parlamento. [106] En él se incluía la primera toma de poder de Musharraf en 1999 y la segunda en noviembre de 2007, cuando declaró el estado de emergencia como medio para ser reelegido presidente. [107] El pliego de cargos también enumeraba algunas de las contribuciones de Musharraf a la "guerra contra el terrorismo". [107]

Cuatro días después se convocó a la Asamblea Nacional para debatir el proceso de destitución. [108] El 18 de agosto, Musharraf dimitió como presidente de Pakistán debido a la creciente presión política. El 19 de agosto, Musharraf defendió su mandato de nueve años en un discurso de una hora de duración. [109]

Nawaz afirmó que Musharraf era responsable de la crisis del país. "Musharraf hizo retroceder la economía del país 20 años después de imponer la ley marcial y derrocar al gobierno democrático". [110]

Musharraf había destituido a 60 jueces y al presidente de la Corte Suprema Iftikhar Chaudhry bajo el estado de emergencia en marzo de 2007, en un intento fallido de permanecer en el poder. [107] Sharif había defendido la causa de los jueces desde su destitución, y él y Zardari habían apoyado la reinstalación de los jueces en sus campañas. [26] Sin embargo, el nuevo gobierno de coalición no había logrado reinstalar a los jueces, lo que llevó a su colapso a fines de 2008. [26] Zardari temía que Chaudhry deshiciera todos los edictos instaurados por Musharraf, incluida una amnistía que Zardari había recibido por cargos de corrupción. [26]

El 25 de febrero de 2009, el Tribunal Supremo inhabilitó a Nawaz Sharif y a su hermano Shehbaz Sharif, el Ministro Principal de Punjab, para ejercer cargos públicos. Zardari intentó poner a Nawaz bajo arresto domiciliario, [26] pero la policía de Punjab abandonó su residencia después de que una multitud furiosa se reuniera afuera. La decisión de la policía de levantar su confinamiento fue muy probablemente en respuesta a una orden del ejército. [26] [ ¿según quién? ] Nawaz, con un gran contingente de todoterrenos, comenzó a liderar una marcha hacia Islamabad pero terminó la marcha en Gujranwala . [26] En un discurso televisado el 16 de marzo, el Primer Ministro Yusuf Raza Gilani prometió restituir a Chaudhry después de recibir presión del ejército de Pakistán, enviados estadounidenses y británicos y protestas internas. El PPP hizo un acuerdo secreto para restaurar el gobierno del PML en Punjab. Nawaz luego canceló la "larga marcha". [26]

El gobierno dirigido por el PPP siguió sobreviviendo. Un alto dirigente del PML-N dijo que "el 95% de los miembros del PML(N) estaban en contra de formar parte del movimiento de abogados, pero después del veredicto [del Tribunal Supremo], el PML(N) no tuvo otra opción". [111]

El 8 de abril de 2010, el Parlamento aprobó la 18.ª Enmienda , que eliminaba el impedimento que permitía a los primeros ministros cumplir un máximo de dos mandatos en el cargo. Esto hizo que Nawaz pudiera volver a ser primer ministro, [112] lo que hizo en 2013.

Entre 2011 y 2013, Nawaz e Imran Khan comenzaron a enzarzarse en una amarga disputa. La rivalidad entre ambos líderes aumentó a fines de 2011, cuando Khan se dirigió a una gran multitud en Minar-e-Pakistan, en Lahore. Ambos comenzaron a culparse mutuamente por muchas razones políticas. [113] [114]

Desde el 26 de abril de 2013, en vísperas de las elecciones de 2013 , tanto el PML-N como el Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) se criticaron mutuamente con vehemencia. Khan fue acusado de atacar personalmente a Nawaz y la Comisión Electoral de Pakistán le notificó , aunque Khan lo negó. [115] [116]

Sólo a través de su voto podrá lograr un cambio que genere prosperidad, fortalezca las fronteras del país, ponga fin al terrorismo, mejore la educación, realice reformas agrarias y ponga a Sindh y a Pakistán en el camino del progreso.

—Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz hizo campaña con la promesa de terminar con los cortes de suministro eléctrico , construir autopistas y el ferrocarril de alta velocidad Peshawar-Karachi . [117] También prometió construir un tercer puerto en Keti Bandar en la costa sur del distrito de Thatta . [118] Justo antes de las elecciones, Nawaz confirmó que había tenido una larga conversación telefónica con el primer ministro indio , Manmohan Singh , sugiriendo un deseo de mejorar las relaciones diplomáticas. [119]

La Comisión Electoral de Pakistán anunció que el PML-N había obtenido 124 escaños en el Parlamento. Sharif necesitaba 13 escaños adicionales para formar una mayoría, por lo que mantuvo conversaciones con candidatos independientes electos para formar una coalición. [120] Ocho días después, 18 candidatos independientes se unieron al partido, lo que permitió al PML-N formar gobierno sin el acuerdo de otro partido político. [121] Nawaz declaró que quería prestar juramento como primer ministro el 28 de mayo, el decimoquinto aniversario de las pruebas nucleares de Chagai-I . [122] [ necesita actualización ]

El 27 de junio de 2014, Khan anunció que el PTI marcharía el 14 de agosto en protesta contra el gobierno, alegando que las elecciones de 2013 habían sido amañadas. [123] El 6 de agosto de 2014, Khan exigió que se disolvieran las asambleas y las renuncias de la comisión electoral y el primer ministro, afirmando que la marcha sería la "protesta política más grande en la historia del país". [124] El PTI comenzó su marcha desde Lahore el 14 de agosto y llegó a Islamabad el 16 de agosto. [125] Khan acusó a Nawaz de saquear la riqueza nacional y pidió al público que retuviera los impuestos y el pago de las facturas de los servicios públicos para obligar al gobierno a dimitir. [126] En protesta por el supuesto fraude electoral, los legisladores del PTI anunciaron su renuncia a la Asamblea Nacional y a las asambleas de Punjab y Sindh. [127] El PML-N intentó negociar un acuerdo con Khan y los partidarios de su partido para romper el estancamiento político. [128] El 22 de agosto de 2014, Khan y sus 33 compañeros legisladores del PTI renunciaron a la Asamblea Nacional. Pidió que se formara un gobierno provisional integrado por no políticos y que se convocaran nuevas elecciones. [129]

El 7 de junio de 2013, Nawaz juró su cargo para un tercer mandato sin precedentes como primer ministro. Se enfrentó a numerosos desafíos, entre ellos poner fin a los ataques con aviones no tripulados estadounidenses y a los ataques talibanes , al tiempo que abordaba una economía paralizada . Se especuló ampliamente con que el nuevo gobierno necesitaría un rescate del Fondo Monetario Internacional para restablecer la estabilidad económica. [130]

El tercer mandato de Nawaz pasó del conservadurismo social al centrismo social . [131] [132] [133] En 2016, dijo que el futuro de Pakistán sería uno respaldado por una "nación educada, progresista, con visión de futuro y emprendedora". [134] En enero de 2016, respaldó la política del gobierno de Punjab de prohibir que Tablighi Jamaat predicara en instituciones educativas y en febrero promulgó una ley para proporcionar una línea telefónica de ayuda para que las mujeres denunciaran el abuso doméstico, a pesar de las críticas de los partidos religiosos conservadores. [135]

El gobierno de Nawaz ahorcó a Mumtaz Qadri el 29 de febrero de 2016. Qadri había matado a tiros a Salman Taseer por su oposición a las leyes de blasfemia . [136] Según BBC News , la decisión de ahorcar a Qadri fue una indicación de la creciente confianza del gobierno en dominar el poder callejero de los grupos religiosos. [137] Para disgusto de los conservadores religiosos, Nawaz prometió que los autores de crímenes de honor serían "castigados muy severamente". [138] En marzo de 2016, The Washington Post informó que Nawaz estaba desafiando al poderoso clero de Pakistán al desbloquear el acceso a YouTube, presionar para poner fin al matrimonio infantil, promulgar una histórica ley sobre violencia doméstica y supervisar la ejecución de Qadri. [139] [140] El 28 de marzo de 2016, el movimiento Sunni Tehreek encabezó las protestas de casi 2.000 fundamentalistas islámicos , que organizaron una sentada de tres días en el D-Chowk de Islamabad, exigiendo que Nawaz aplicara la sharia y declarara a Qadri mártir. [141] En respuesta, Nawaz se dirigió a la nación y afirmó que aquellos que "avivan el fuego del odio" serían tratados conforme a la ley. [142]

El futuro de la nación está en un Pakistán democrático y liberal donde el sector privado prospere y nadie se quede atrás.

— Nawaz Sharif [143]

El gobierno de Nawaz declaró que las festividades hindúes Diwali y Holi , y la festividad cristiana de Pascua, eran oficialmente días festivos. La revista Time lo calificó como un "paso significativo para las minorías religiosas asediadas del país". [144] El 6 de diciembre de 2016, Nawaz aprobó el cambio de nombre del centro de física de la Universidad Quaid-i-Azam (QAU) al Centro de Física Profesor Abdus Salam. Nawaz también estableció la Beca Profesor Abdus Salam para financiar completamente a cinco estudiantes de doctorado paquistaníes en física. [145] En respuesta, el Consejo de Ideología Islámica criticó la medida de Nawaz alegando que "cambiar el nombre del departamento no sentaría el precedente correcto". [146] [ se necesita más explicación ]

Nawaz destacó la necesidad de que la operación Zarb-e-Qalam combatiera el extremismo social y la intolerancia mediante el poder de los "escritores, poetas e intelectuales". [147] Dirigiéndose a la Academia de Literatura de Pakistán, Nawaz dijo que "en una sociedad donde florecen las flores de la poesía y la literatura, no nacen las enfermedades del extremismo, la intolerancia, la desunión y el sectarismo". Nawaz también anunció un fondo de dotación de 500 millones de rupias para la promoción de las actividades artísticas y literarias en Pakistán. [148] El 9 de enero de 2017, el gobierno negó visas a predicadores internacionales para la conferencia Tablighi Jamaat en Lahore. Jamia Binoria criticó las decisiones del gobierno. [149]

En un discurso pronunciado en marzo de 2017 en Jamia Naeemia , Nawaz instó a los eruditos islámicos a difundir las verdaderas enseñanzas del Islam y a adoptar una postura firme contra quienes están causando desunión entre los musulmanes. Nawaz hizo un llamamiento a favor de un “mundo musulmán progresista y próspero” y pidió a los “eruditos religiosos que […] lleven la guerra contra estos terroristas hasta su fin lógico”. [150]

El 7 de abril de 2016, The Express Tribune afirmó que el plan de seguro de salud multimillonario de Nawaz parecía estar fracasando debido a una mala planificación, afirmando que la infraestructura sanitaria básica no permite un plan de ese tipo. [151] [152] [ ¿relevante? ]

La economía del país se enfrentó a muchos desafíos, entre ellos escasez de energía, hiperinflación , crecimiento económico moderado, deuda elevada y un gran déficit presupuestario. Poco después de tomar el poder en 2013, Nawaz recibió un préstamo de 6.600 millones de dólares del Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) para evitar una crisis de balanza de pagos. Los precios más bajos del petróleo, las remesas más altas y el aumento del gasto de los consumidores impulsaron el crecimiento hacia un máximo de siete años del 4,3 por ciento en el año fiscal 2014-15. [159]

El Banco Asiático de Desarrollo atribuyó el crecimiento gradual de la economía a los bajos precios del petróleo y otras materias primas, la esperada recuperación del crecimiento en las economías avanzadas y cierto alivio de la escasez de energía. [160] Sin embargo, la deuda soberana de Pakistán aumentó drásticamente, y las deudas y pasivos totales aumentaron a 22,5 billones de rupias (o 73 mil millones de dólares) en agosto de 2016. [161] La administración de Nawaz emitió un eurobono a cinco años de 500 millones de dólares en 2015 al 8,25% de interés y en septiembre de 2016 también recaudó 1.000 millones de dólares mediante la emisión de sukuk (bonos islámicos) al 5,5%. [162]

La administración Sharif negoció acuerdos de libre comercio (ALC) para ampliar la liberalización del comercio , en particular con Turquía , Corea del Sur , Irán [163] y Tailandia, y una ampliación del TLC con Malasia.

Según el Instituto de Desarrollo Legislativo y Transparencia del Pakistán (PILDAT), la calidad de la gobernanza había "mejorado marginalmente" durante el primer año de Nawaz en el poder, con una puntuación general del 44%. Obtuvo la puntuación más alta en preparación para desastres, contratación basada en méritos y gestión de la política exterior, mientras que recibió las puntuaciones más bajas en alivio de la pobreza y transparencia. [164]

El 4 de julio de 2013, el FMI y Pakistán llegaron a un acuerdo provisional sobre un paquete de rescate de 5.300 millones de dólares para apuntalar la economía del país, que se encontraba en crisis y sus reservas de divisas peligrosamente bajas, lo que contradecía una promesa electoral de no aceptar más préstamos. [165] El 4 de septiembre, el FMI aprobó otro paquete de préstamos de 6.700 millones de dólares a lo largo de un período de tres años. El FMI exigió que Pakistán llevara a cabo reformas económicas, incluida la privatización de 31 empresas estatales. [166]

La confianza empresarial en Pakistán alcanzó su nivel más alto en tres años en mayo de 2014, respaldada por el aumento de las reservas extranjeras, que superaron los 15.000 millones de dólares a mediados de 2014. En mayo de 2014, el FMI afirmó que la inflación había caído al 13% (en comparación con el 25% en 2008), las reservas extranjeras estaban en una mejor posición y que el déficit de cuenta corriente había bajado al 3% del PIB. [167] Standard & Poor's y Moody's Corporation cambiaron la calificación de largo plazo de Pakistán a "perspectiva estable". [168] [169] [170] El Banco Mundial afirmó el 9 de abril de 2014 que la economía de Pakistán estaba en un punto de inflexión, con un crecimiento proyectado del PIB cercano al 4%, impulsado por los sectores manufacturero y de servicios, una mejor disponibilidad de energía y una pronta recuperación de la confianza de los inversores. [171]

En el año fiscal 2015, el crecimiento industrial se desaceleró debido a la escasez de energía, [160] ya que la administración de Sharif no logró realizar reformas adecuadas en materia de energía, impuestos y empresas del sector público. [172] El 3 de mayo, The Economist le dio a la administración de Sharif crédito parcial por la nueva estabilidad de la economía, tras haber mantenido sus acuerdos con el FMI. Standard & Poor revisó la calificación crediticia de Pakistán de "estable" a "positiva", destacando los esfuerzos del gobierno en pos de la consolidación fiscal, la mejora de las condiciones de financiamiento externo y mayores entradas de capital. [173]

.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Durante un viaje a Pakistán el 10 de febrero de 2016, el presidente del Grupo del Banco Mundial, Jim Yong Kim, aplaudió las políticas económicas del gobierno de Nawaz. Afirmó que las perspectivas económicas de Pakistán se habían vuelto más estables. [174] El 19 de marzo, Nawaz aprobó incentivos fiscales en un intento de atraer nuevas plantas de fabricación de automóviles al país. [175] En noviembre de 2016, el gobierno anunció que se esperaba que Renault comenzara a ensamblar automóviles en Pakistán en 2018. [176] [177]

El 8 de abril de 2016, tras la presión ejercida por grupos de desarrollo internacionales, el gobierno cambió su metodología para medir la pobreza. La línea de pobreza pasó de 2.350 rupias a 3.030 rupias por adulto al mes, lo que aumentó la tasa de pobreza del 9,3% al 29,5%. [178] Una encuesta de PILDAT afirmó que la calidad de la gobernanza había mejorado, aunque todavía era débil en cuanto a transparencia. [179] Fred Hochberg , director del Banco de Exportación e Importación de los Estados Unidos, visitó Pakistán el 14 de abril y dijo que "ve muchas oportunidades para ampliar su exposición a Pakistán". [180]

El 9 de mayo, el Informe sobre el Desarrollo del Pakistán del Banco Mundial afirmó que la cuenta corriente se encontraba en una posición saludable, pero que la competitividad de las exportaciones del Pakistán había disminuido debido a las políticas proteccionistas, la mala infraestructura y los altos costos de transacción del comercio. En consecuencia, la relación entre las exportaciones y el PIB del Pakistán había estado disminuyendo durante las dos últimas décadas. [181]

El 15 de diciembre de 2016, Pakistán se convirtió en signatario de la Convención sobre Asistencia Administrativa Mutua en Materia Fiscal de la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE) , destinada a frenar la evasión fiscal. [182] En su libro de 2016, The Rise and Fall of Nations , Ruchir Sharma afirmó que la economía de Pakistán estaba en una etapa de "despegue" y que las perspectivas futuras hasta 2020 eran "muy buenas". [183]

El 24 de octubre de 2016, meses después de que el gobierno de Sharif concluyera un programa trienal de 6.400 millones de dólares, la directora gerente del FMI, Christine Lagarde, visitó Pakistán, durante la cual sostuvo que el país estaba "fuera de la crisis económica". Añadió que era necesario seguir haciendo esfuerzos para que más personas pagaran impuestos y garantizar que todos pagaran la parte que les correspondía. [184] El índice de facilidad para hacer negocios de 2017 reconoció a Pakistán como uno de los diez países que más mejoras estaban haciendo en materia de regulación empresarial. [185]

Cientos de camiones chinos cargados con mercancías llegaron al puerto seco de Sost en Gilgit-Baltistán el 1 de noviembre como el primer envío del Corredor Económico China-Pakistán . [187] [ ¿relevante? ]

El gobierno anunció planes para reestructurar PIA, que buscaba volverse más competitiva mediante el arrendamiento de aeronaves más nuevas y eficientes. PIA se dividió en dos compañías: un grupo holding retendría unos ₨ 250 mil millones en deuda y personal excedente, y una "nueva" PIA mantendría los lucrativos derechos de aterrizaje y las nuevas aeronaves. El gobierno planeó vender una participación del 26% en la nueva PIA a un socio estratégico. En febrero de 2016, Pakistan International Airlines Corporation (PIAC) se convertirá en una sociedad anónima como Pakistan International Airlines Company Limited (PIACL) para dar paso a la privatización, sin embargo, esto desencadenó una huelga sindical de ocho días. [188] [ necesita actualización ] El 23 de diciembre de 2016, un consorcio chino ganó la licitación por una participación del 40% en PSX con una oferta de US$85,5 millones. [189]

Al asumir el cargo, Nawaz lanzó el Programa de Desarrollo del Sector Público (PSDP) que construyó proyectos importantes para estimular la economía. Esto incluyó la presa Diamer-Bhasha , la presa Dasu , la autopista M-4 Faisalabad-Khanewal , el servicio de metrobús Rawalpindi-Islamabad y la autopista Lahore-Karachi. [190] Nawaz también aprobó estudios de viabilidad para muchos otros proyectos. [191] Durante el año fiscal 2014-15, el gobierno de Nawaz anunció una financiación adicional del PSDP de ₨ 425 a ₨ 525 mil millones. [192] [193] El gobierno asignó ₨ 73 mil millones de fondos del PSDP para el Corredor Económico China-Pakistán , incluida la autopista Lahore-Karachi. [194]

En enero de 2017, The Economist criticó el gasto de Nawaz en infraestructura, explicando que no se utilizó porque "el auge económico que se suponía que desencadenaría nunca llegó". En cuanto al Corredor Económico China-Pakistán , la revista escribió que "los críticos temen que el país tenga dificultades para pagar la deuda, especialmente si los ingresos en divisas de las exportaciones siguen disminuyendo", y agregó que "puede que no le preocupe demasiado al Sr. Sharif si la próxima generación de carreteras está tan desierta como la última". [195]

El 24 de abril de 2014, las compañías de telefonía móvil Mobilink, Telenor, Ufone y Zong ganaron subastas de licencias de espectro móvil 3G y 4G, recaudando 1.112 millones de dólares. Nawaz afirmó que se recaudarán 260.000 millones de rupias en ingresos anuales por las licencias, mientras que la tecnología crearía millones de puestos de trabajo en el sector de servicios. [196] Nawaz también lanzó el Programa de la Juventud del Primer Ministro , proporcionando un fondo de 20.000 millones de rupias para préstamos sin intereses, desarrollo de habilidades y suministro de computadoras portátiles.

El 27 de marzo de 2016, unos 2.000 manifestantes de extrema derecha encabezados por Sunni Tehreek organizaron una sentada en D-Chowk, frente al parlamento de Islamabad, lo que provocó un cierre parcial de la capital. Los manifestantes exigieron la aplicación de la sharia en el país y la declaración de Mumtaz Qadri como mártir. Los manifestantes quemaron coches y una estación de transporte público e hirieron a periodistas y transeúntes. [197] El gobierno llamó al ejército para imponer el orden. [198] Para el 29 de marzo, la multitud se había reducido a 700 manifestantes, [199] y la protesta terminó el 30 de marzo después de que el gobierno prometiera no modificar las leyes sobre la blasfemia. [200]

El 29 de octubre de 2016, Imran Khan comenzó a movilizar a los trabajadores para cerrar Islamabad y exigir la dimisión de Nawaz y una investigación por corrupción. En respuesta, el gobierno de Sharif prohibió las reuniones en toda la ciudad y detuvo a cientos de activistas de la oposición. El gobierno también detuvo a decenas de trabajadores de Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf y cerró la autopista que conducía a Khyber Pakhtunkhwa . El 1 de noviembre, Khan cesó las protestas después de que el Tribunal Supremo dijera que formaría una comisión judicial para investigar las acusaciones derivadas de las filtraciones de los "Papeles de Panamá" sobre la riqueza offshore de la familia Sharif. [201] En la primera semana de enero, cuatro activistas paquistaníes conocidos en las redes sociales por sus opiniones seculares de izquierda desaparecieron. [202]

In August 2014, the Sharif administration unveiled an ambitious programme to enhance exports to US$150 billion by 2025.[203] According to the Daily Times, the Vision 2025 is based on seven pillars: putting people first; developing human and social capital; achieving sustained, indigenous and inclusive growth; governance, institutional reform and modernisation of the public sector; energy, water and food security; private-sector-led growth and entrepreneurship, developing a competitive knowledge economy through value addition and modernisation of transportation infrastructure and greater regional connectivity.[204][clarification needed]

Considering the existing political challenges faced by Sharif and shaky democratic process in the country, ownership of the rather flawed Vision 2025 is another major concern. The question is will future political setups continue to work on this plan to make it a reality, in case of any change of guard at the center? Each successive government in Pakistan has historically made a U-turn from its predecessor's policies. If this trend prevails, then the Vision 2025 will fail to translate into action.

— Arab News, 18 August 2014[205]

In November 2013, Nawaz broke ground on a US$9.59 billion nuclear power complex in Karachi, designed to produce 2200 MW of electricity.[207] During the groundbreaking ceremony, Nawaz stated that Pakistan would construct six nuclear power plants during his term in office.[208] He went on to say that Pakistan has plans to construct a total of 32 nuclear power plants by 2050, which will generate more than 40,000 MW.[209] In February 2014, Nawaz confirmed to the IAEA that all future civilian nuclear power plants and research reactors will voluntarily be put under IAEA safeguards.[210]

Nawaz attended the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit, and stated that Pakistan was giving nuclear security the highest importance.[211]

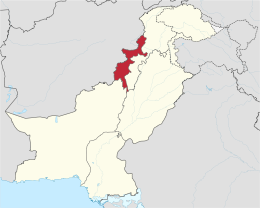

On 3 March 2017, Nawaz's cabinet approved a set of steps to be taken for the proposed merger of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, along with a 10-year ₨110 billion development-reform package. Under the reform project, the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and the Peshawar High Court will be extended to the FATA region.[212]

On 9 September 2013, Nawaz proposed a civil-military partnership,[213] and immediately reestablished the National Security Council with Sartaj Aziz as his National Security Advisor (NSA).[214] Nawaz also reconstituted the Cabinet Committee on National Security (C2NS), with military representation in the political body.[215] According to political scientist and civic-military relations expert Aqil Shah, Nawaz finally did exactly what former chairman joint chiefs Jehangir Karamat had called for in 1998.[215]

In September 2013, Nawaz announced that Pakistan would open unconditional talks with the Taliban, declaring them stakeholders rather than terrorists. The PML-N's conservative hardliners also chose to blame the US and NATO for causing terrorism in Pakistan. However, Pakistani Taliban's Supreme Council demanded a cease-fire, to also include the release of all imprisoned militants and the withdrawal of the Pakistani military from all tribal regions. Former and current government officials criticised Nawaz for not providing clear leadership on how to handle the more than 40 militant groups, many of them comprising violent Islamic extremists.[216]

On 15 September, just six days after Nawaz's proposal for talks with the Taliban, a roadside bomb killed Major-General Sanaullah Khan, a lieutenant colonel and another soldier in the Upper Dir district near the Afghanistan border. Taliban spokesman Shahidullah Shahid claimed responsibility for the bombing. On the same day, seven more soldiers were killed in four separate attacks.[217] In a press release, Chairman joint chiefs General Khalid Shameem Wynne and chief of army staff General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, who had earlier warned Nawaz not to adopt a surrender strategy, publicly warned the government that the military would not allow the Taliban to set conditions for peace. General Kayani stated: "No-one should have any misgivings that we would let terrorists coerce us into accepting their terms."[218][219]

Pakistan desires peace and tranquility both within and outside its borders so that the much needed socio-economic development goals are achieved. We cannot afford to be distracted in fulfilling our national objectives. At the same [time] Pakistan will never compromise on its sovereignty and independence.

— Nawaz Sharif, addressing the Pakistan Naval War College[220]

Seven members of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan conducted a terrorist attack on a public school in the city of Peshawar on 16 December, killing over 130 children in Pakistan's deadliest terrorist attack. In response to the attack, Nawaz – with consultation from all political parties – devised a 20-point National Action Plan which included continued execution of convicted terrorists, establishment of special military courts for two years and regulation of madrasas.[221]

Based on the National Action Plan, the government made 32,347 arrests in 28,826 operations conducted across the country from 24 December 2014 to 25 March 2015. During the same period, Pakistan deported 18,855 Afghan refugees while the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) registered 64 cases for money transfer through Hawala, arrested 83 people and recovered ₨101.7 million. In total, 351 actionable calls were received on the anti-terror helpline and National Database and Registration Authority verified 59.47 million SIMs.[222] On 28 March 2016, a suicide attack by the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar at a park in Lahore killed 70 people on the evening of Easter Sunday.[223] Analysts believed that Nawaz's desire to maintain stability in Punjab led him to turn a blind eye towards groups operating there. Following the attack, Pakistan detained more than 5,000 suspects and made 216 arrests.[224]