Funciones especiales de varias variables complejas

Función theta de Jacobi θ 1 q = e i π τ e 0,1 i π θ 1 ( el , q ) = 2 q 1 4 ∑ norte = 0 ∞ ( − 1 ) norte q norte ( norte + 1 ) pecado ( 2 norte + 1 ) el = ∑ norte = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) norte − 1 2 q ( norte + 1 2 ) 2 mi ( 2 norte + 1 ) i el . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\theta _{1}(z,q)&=2q^{\frac {1}{4}}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }(-1 )^{n}q^{n(n+1)}\sin(2n+1)z\\&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }(-1)^{n- {\frac {1}{2}}}q^{\left(n+{\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{2}}e^{(2n+1)iz}.\end{ alineado}}} En matemáticas , las funciones theta son funciones especiales de varias variables complejas . Aparecen en muchos temas, incluidas las variedades abelianas , los espacios de módulos , las formas cuadráticas y los solitones . Como álgebras de Grassmann , aparecen en la teoría cuántica de campos . [1]

La forma más común de función theta es la que se da en la teoría de funciones elípticas . Con respecto a una de las variables complejas (convencionalmente llamada z ), una función theta tiene una propiedad que expresa su comportamiento con respecto a la adición de un período de las funciones elípticas asociadas, lo que la convierte en una función cuasiperiódica . En la teoría abstracta, esta cuasiperiodicidad proviene de la clase de cohomología de un fibrado lineal en un toro complejo , una condición de descendencia .

Una interpretación de las funciones theta cuando se trata de la ecuación del calor es que "una función theta es una función especial que describe la evolución de la temperatura en un dominio de segmento sujeto a ciertas condiciones de contorno". [2]

A lo largo de este artículo, debe interpretarse como (para resolver cuestiones de elección de rama ). [nota 1] ( mi π i τ ) alfa {\displaystyle (e^{\pi i\tau })^{\alpha }} mi alfa π i τ {\displaystyle e^{\alpha \pi i\tau }}

Función theta de Jacobi Existen varias funciones estrechamente relacionadas llamadas funciones theta de Jacobi, y muchos sistemas de notación diferentes e incompatibles para ellas. Una función theta de Jacobi (nombrada en honor a Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi ) es una función definida para dos variables complejas z y τ , donde z puede ser cualquier número complejo y τ es la razón de semiperíodos , confinada al semiplano superior , lo que significa que tiene una parte imaginaria positiva. Se da por la fórmula

ϑ ( el ; τ ) = ∑ norte = − ∞ ∞ exp ( π i norte 2 τ + 2 π i norte el ) = 1 + 2 ∑ norte = 1 ∞ q norte 2 porque ( 2 π norte el ) = ∑ norte = − ∞ ∞ q norte 2 η norte {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta (z;\tau )&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\exp \left(\pi in^{2}\tau +2\pi inz\right)\\&=1+2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }q^{n^{2}}\cos(2\pi nz)\\&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{n^{2}}\eta ^{n}\end{aligned}}} donde q = exp( πiτ )nombre y η = exp(2 πiz )forma de Jacobi . La restricción asegura que sea una serie absolutamente convergente. En τ fijo , esta es una serie de Fourier para una función entera 1-periódica de z . En consecuencia, la función theta es 1-periódica en z :

ϑ ( z + 1 ; τ ) = ϑ ( z ; τ ) . {\displaystyle \vartheta (z+1;\tau )=\vartheta (z;\tau ).} Al completar el cuadrado , también es τ -cuasiperiódico en z , con

ϑ ( z + τ ; τ ) = exp ( − π i ( τ + 2 z ) ) ϑ ( z ; τ ) . {\displaystyle \vartheta (z+\tau ;\tau )=\exp {\bigl (}-\pi i(\tau +2z){\bigr )}\vartheta (z;\tau ).} Así pues, en general,

ϑ ( z + a + b τ ; τ ) = exp ( − π i b 2 τ − 2 π i b z ) ϑ ( z ; τ ) {\displaystyle \vartheta (z+a+b\tau ;\tau )=\exp \left(-\pi ib^{2}\tau -2\pi ibz\right)\vartheta (z;\tau )} para cualquier número entero a y b .

Para cualquier fijo , la función es una función completa en el plano complejo, por lo que, según el teorema de Liouville , no puede ser doblemente periódica en a menos que sea constante, por lo que lo mejor que podemos hacer es hacerla periódica en y cuasiperiódica en . De hecho, dado que y , la función no está acotada, como lo exige el teorema de Liouville. τ {\displaystyle \tau } 1 , τ {\displaystyle 1,\tau } 1 {\displaystyle 1} τ {\displaystyle \tau } | ϑ ( z + a + b τ ; τ ) ϑ ( z ; τ ) | = exp ( π ( b 2 ℑ ( τ ) + 2 b ℑ ( z ) ) ) {\displaystyle \left|{\frac {\vartheta (z+a+b\tau ;\tau )}{\vartheta (z;\tau )}}\right|=\exp \left(\pi (b^{2}\Im (\tau )+2b\Im (z))\right)} ℑ ( τ ) > 0 {\displaystyle \Im (\tau )>0} ϑ ( z , τ ) {\displaystyle \vartheta (z,\tau )}

Se trata de hecho de la función completa más general con 2 cuasi-periodos, en el siguiente sentido: [3]

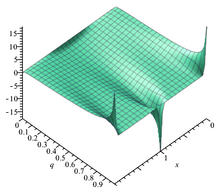

Función theta θ 1 q = e iπτ q con τ . Función theta θ 1 q = e iπτ q con τ .

Funciones auxiliares La función theta de Jacobi definida anteriormente a veces se considera junto con tres funciones theta auxiliares, en cuyo caso se escribe con un subíndice doble 0:

ϑ 00 ( z ; τ ) = ϑ ( z ; τ ) {\displaystyle \vartheta _{00}(z;\tau )=\vartheta (z;\tau )} Las funciones auxiliares (o de semiperíodo) se definen mediante

ϑ 01 ( z ; τ ) = ϑ ( z + 1 2 ; τ ) ϑ 10 ( z ; τ ) = exp ( 1 4 π i τ + π i z ) ϑ ( z + 1 2 τ ; τ ) ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) = exp ( 1 4 π i τ + π i ( z + 1 2 ) ) ϑ ( z + 1 2 τ + 1 2 ; τ ) . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{01}(z;\tau )&=\vartheta \left(z+{\tfrac {1}{2}};\tau \right)\\[3pt]\vartheta _{10}(z;\tau )&=\exp \left({\tfrac {1}{4}}\pi i\tau +\pi iz\right)\vartheta \left(z+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\tau ;\tau \right)\\[3pt]\vartheta _{11}(z;\tau )&=\exp \left({\tfrac {1}{4}}\pi i\tau +\pi i\left(z+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\right)\right)\vartheta \left(z+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\tau +{\tfrac {1}{2}};\tau \right).\end{aligned}}} Esta notación sigue a Riemann y Mumford ; la formulación original de Jacobi estaba en términos del nombre q = e iπτ τ . En la notación de Jacobi, las funciones θ se escriben:

θ 1 ( z ; q ) = θ 1 ( π z , q ) = − ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) θ 2 ( z ; q ) = θ 2 ( π z , q ) = ϑ 10 ( z ; τ ) θ 3 ( z ; q ) = θ 3 ( π z , q ) = ϑ 00 ( z ; τ ) θ 4 ( z ; q ) = θ 4 ( π z , q ) = ϑ 01 ( z ; τ ) {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\theta _{1}(z;q)&=\theta _{1}(\pi z,q)=-\vartheta _{11}(z;\tau )\\\theta _{2}(z;q)&=\theta _{2}(\pi z,q)=\vartheta _{10}(z;\tau )\\\theta _{3}(z;q)&=\theta _{3}(\pi z,q)=\vartheta _{00}(z;\tau )\\\theta _{4}(z;q)&=\theta _{4}(\pi z,q)=\vartheta _{01}(z;\tau )\end{aligned}}} Jacobi theta 1 Jacobi theta 2 Jacobi theta 3 Jacobi theta 4 Las definiciones anteriores de las funciones theta de Jacobi no son únicas. Consulte Funciones theta de Jacobi (variaciones de notación) para obtener más información.

Si establecemos z = 0τ solamente, definidas en el semiplano superior. Estas funciones se denominan funciones Theta Nullwert , basadas en el término alemán para el valor cero debido a la anulación de la entrada izquierda en la expresión de la función theta. Alternativamente, obtenemos cuatro funciones de q solamente, definidas en el disco unitario . A veces se las llama constantes theta : [nota 2] | q | < 1 {\displaystyle |q|<1}

ϑ 11 ( 0 ; τ ) = − θ 1 ( q ) = − ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) n − 1 / 2 q ( n + 1 / 2 ) 2 ϑ 10 ( 0 ; τ ) = θ 2 ( q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ q ( n + 1 / 2 ) 2 ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) = θ 3 ( q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ q n 2 ϑ 01 ( 0 ; τ ) = θ 4 ( q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) n q n 2 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{11}(0;\tau )&=-\theta _{1}(q)=-\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }(-1)^{n-1/2}q^{(n+1/2)^{2}}\\\vartheta _{10}(0;\tau )&=\theta _{2}(q)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{(n+1/2)^{2}}\\\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )&=\theta _{3}(q)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{n^{2}}\\\vartheta _{01}(0;\tau )&=\theta _{4}(q)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }(-1)^{n}q^{n^{2}}\end{aligned}}} con el nombre q = e iπτ formas modulares y para parametrizar ciertas curvas; en particular, la identidad de Jacobi es θ 1 ( q ) = 0 {\displaystyle \theta _{1}(q)=0}

θ 2 ( q ) 4 + θ 4 ( q ) 4 = θ 3 ( q ) 4 {\displaystyle \theta _{2}(q)^{4}+\theta _{4}(q)^{4}=\theta _{3}(q)^{4}} o equivalentemente,

ϑ 01 ( 0 ; τ ) 4 + ϑ 10 ( 0 ; τ ) 4 = ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) 4 {\displaystyle \vartheta _{01}(0;\tau )^{4}+\vartheta _{10}(0;\tau )^{4}=\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )^{4}} que es la curva de Fermat de grado cuatro.

Identidades de Jacobi Las identidades de Jacobi describen cómo las funciones theta se transforman bajo el grupo modular , que es generado por τ ↦ τ + 1τ ↦ − 1 / τ τ en el exponente tiene el mismo efecto que sumar 1 / 2 z ( n ≡ n 2 mod 2

α = ( − i τ ) 1 2 exp ( π τ i z 2 ) . {\displaystyle \alpha =(-i\tau )^{\frac {1}{2}}\exp \left({\frac {\pi }{\tau }}iz^{2}\right).} Entonces

ϑ 00 ( z τ ; − 1 τ ) = α ϑ 00 ( z ; τ ) ϑ 01 ( z τ ; − 1 τ ) = α ϑ 10 ( z ; τ ) ϑ 10 ( z τ ; − 1 τ ) = α ϑ 01 ( z ; τ ) ϑ 11 ( z τ ; − 1 τ ) = − i α ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{00}\!\left({\frac {z}{\tau }};{\frac {-1}{\tau }}\right)&=\alpha \,\vartheta _{00}(z;\tau )\quad &\vartheta _{01}\!\left({\frac {z}{\tau }};{\frac {-1}{\tau }}\right)&=\alpha \,\vartheta _{10}(z;\tau )\\[3pt]\vartheta _{10}\!\left({\frac {z}{\tau }};{\frac {-1}{\tau }}\right)&=\alpha \,\vartheta _{01}(z;\tau )\quad &\vartheta _{11}\!\left({\frac {z}{\tau }};{\frac {-1}{\tau }}\right)&=-i\alpha \,\vartheta _{11}(z;\tau ).\end{aligned}}}

Theta funciona en términos del nomo En lugar de expresar las funciones Theta en términos de z y τ , podemos expresarlas en términos de los argumentos w y el nombre q , donde w = e πiz q = e πiτ

ϑ 00 ( w , q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( w 2 ) n q n 2 ϑ 01 ( w , q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) n ( w 2 ) n q n 2 ϑ 10 ( w , q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( w 2 ) n + 1 2 q ( n + 1 2 ) 2 ϑ 11 ( w , q ) = i ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) n ( w 2 ) n + 1 2 q ( n + 1 2 ) 2 . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{00}(w,q)&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\left(w^{2}\right)^{n}q^{n^{2}}\quad &\vartheta _{01}(w,q)&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }(-1)^{n}\left(w^{2}\right)^{n}q^{n^{2}}\\[3pt]\vartheta _{10}(w,q)&=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\left(w^{2}\right)^{n+{\frac {1}{2}}}q^{\left(n+{\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{2}}\quad &\vartheta _{11}(w,q)&=i\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }(-1)^{n}\left(w^{2}\right)^{n+{\frac {1}{2}}}q^{\left(n+{\frac {1}{2}}\right)^{2}}.\end{aligned}}} Vemos que las funciones theta también se pueden definir en términos de w y q , sin una referencia directa a la función exponencial. Por lo tanto, estas fórmulas se pueden utilizar para definir las funciones theta sobre otros campos en los que la función exponencial podría no estar definida en todas partes, como los campos de números p -ádicos .

Representaciones de productos El triple producto de Jacobi (un caso especial de las identidades de Macdonald ) nos dice que para números complejos w y q con | q y w ≠ 0

∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 + w 2 q 2 m − 1 ) ( 1 + w − 2 q 2 m − 1 ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ w 2 n q n 2 . {\displaystyle \prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1+w^{2}q^{2m-1}\right)\left(1+w^{-2}q^{2m-1}\right)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }w^{2n}q^{n^{2}}.} Se puede demostrar por medios elementales, como por ejemplo en Introducción a la teoría de números,

Si expresamos la función theta en términos del nombre q = e πiτ q = e 2 πiτ w = e πiz

ϑ ( z ; τ ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ exp ( π i τ n 2 ) exp ( 2 π i z n ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ w 2 n q n 2 . {\displaystyle \vartheta (z;\tau )=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\exp(\pi i\tau n^{2})\exp(2\pi izn)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }w^{2n}q^{n^{2}}.} Por lo tanto, obtenemos una fórmula del producto para la función theta en la forma

ϑ ( z ; τ ) = ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − exp ( 2 m π i τ ) ) ( 1 + exp ( ( 2 m − 1 ) π i τ + 2 π i z ) ) ( 1 + exp ( ( 2 m − 1 ) π i τ − 2 π i z ) ) . {\displaystyle \vartheta (z;\tau )=\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }{\big (}1-\exp(2m\pi i\tau ){\big )}{\Big (}1+\exp {\big (}(2m-1)\pi i\tau +2\pi iz{\big )}{\Big )}{\Big (}1+\exp {\big (}(2m-1)\pi i\tau -2\pi iz{\big )}{\Big )}.} En términos de w y q :

ϑ ( z ; τ ) = ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 + q 2 m − 1 w 2 ) ( 1 + q 2 m − 1 w 2 ) = ( q 2 ; q 2 ) ∞ ( − w 2 q ; q 2 ) ∞ ( − q w 2 ; q 2 ) ∞ = ( q 2 ; q 2 ) ∞ θ ( − w 2 q ; q 2 ) {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta (z;\tau )&=\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1+q^{2m-1}w^{2}\right)\left(1+{\frac {q^{2m-1}}{w^{2}}}\right)\\&=\left(q^{2};q^{2}\right)_{\infty }\,\left(-w^{2}q;q^{2}\right)_{\infty }\,\left(-{\frac {q}{w^{2}}};q^{2}\right)_{\infty }\\&=\left(q^{2};q^{2}\right)_{\infty }\,\theta \left(-w^{2}q;q^{2}\right)\end{aligned}}} donde ( ; ) ∞ es el símbolo q -Pochhammer y θ ( ; )función q -theta . Desarrollando términos, el producto triple de Jacobi también se puede escribir

∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 + ( w 2 + w − 2 ) q 2 m − 1 + q 4 m − 2 ) , {\displaystyle \prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right){\Big (}1+\left(w^{2}+w^{-2}\right)q^{2m-1}+q^{4m-2}{\Big )},} que también podemos escribir como

ϑ ( z ∣ q ) = ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 + 2 cos ( 2 π z ) q 2 m − 1 + q 4 m − 2 ) . {\displaystyle \vartheta (z\mid q)=\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1+2\cos(2\pi z)q^{2m-1}+q^{4m-2}\right).} Esta forma es válida en general, pero claramente es de particular interés cuando z es real. Fórmulas de producto similares para las funciones theta auxiliares son

ϑ 01 ( z ∣ q ) = ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 − 2 cos ( 2 π z ) q 2 m − 1 + q 4 m − 2 ) , ϑ 10 ( z ∣ q ) = 2 q 1 4 cos ( π z ) ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 + 2 cos ( 2 π z ) q 2 m + q 4 m ) , ϑ 11 ( z ∣ q ) = − 2 q 1 4 sin ( π z ) ∏ m = 1 ∞ ( 1 − q 2 m ) ( 1 − 2 cos ( 2 π z ) q 2 m + q 4 m ) . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{01}(z\mid q)&=\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1-2\cos(2\pi z)q^{2m-1}+q^{4m-2}\right),\\[3pt]\vartheta _{10}(z\mid q)&=2q^{\frac {1}{4}}\cos(\pi z)\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1+2\cos(2\pi z)q^{2m}+q^{4m}\right),\\[3pt]\vartheta _{11}(z\mid q)&=-2q^{\frac {1}{4}}\sin(\pi z)\prod _{m=1}^{\infty }\left(1-q^{2m}\right)\left(1-2\cos(2\pi z)q^{2m}+q^{4m}\right).\end{aligned}}} En particular, podemos interpretarlas como deformaciones de un parámetro de las funciones periódicas , validando nuevamente la interpretación de la función theta como la función cuasi-período 2 más general. lim q → 0 ϑ 10 ( z ∣ q ) 2 q 1 4 = cos ( π z ) , lim q → 0 − ϑ 11 ( z ∣ q ) 2 q − 1 4 = sin ( π z ) {\displaystyle \lim _{q\to 0}{\frac {\vartheta _{10}(z\mid q)}{2q^{\frac {1}{4}}}}=\cos(\pi z),\quad \lim _{q\to 0}{\frac {-\vartheta _{11}(z\mid q)}{2q^{-{\frac {1}{4}}}}}=\sin(\pi z)} sin , cos {\displaystyle \sin ,\cos }

Representaciones integrales Las funciones theta de Jacobi tienen las siguientes representaciones integrales:

ϑ 00 ( z ; τ ) = − i ∫ i − ∞ i + ∞ e i π τ u 2 cos ( 2 π u z + π u ) sin ( π u ) d u ; ϑ 01 ( z ; τ ) = − i ∫ i − ∞ i + ∞ e i π τ u 2 cos ( 2 π u z ) sin ( π u ) d u ; ϑ 10 ( z ; τ ) = − i e i π z + 1 4 i π τ ∫ i − ∞ i + ∞ e i π τ u 2 cos ( 2 π u z + π u + π τ u ) sin ( π u ) d u ; ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) = e i π z + 1 4 i π τ ∫ i − ∞ i + ∞ e i π τ u 2 cos ( 2 π u z + π τ u ) sin ( π u ) d u . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta _{00}(z;\tau )&=-i\int _{i-\infty }^{i+\infty }e^{i\pi \tau u^{2}}{\frac {\cos(2\pi uz+\pi u)}{\sin(\pi u)}}\mathrm {d} u;\\[6pt]\vartheta _{01}(z;\tau )&=-i\int _{i-\infty }^{i+\infty }e^{i\pi \tau u^{2}}{\frac {\cos(2\pi uz)}{\sin(\pi u)}}\mathrm {d} u;\\[6pt]\vartheta _{10}(z;\tau )&=-ie^{i\pi z+{\frac {1}{4}}i\pi \tau }\int _{i-\infty }^{i+\infty }e^{i\pi \tau u^{2}}{\frac {\cos(2\pi uz+\pi u+\pi \tau u)}{\sin(\pi u)}}\mathrm {d} u;\\[6pt]\vartheta _{11}(z;\tau )&=e^{i\pi z+{\frac {1}{4}}i\pi \tau }\int _{i-\infty }^{i+\infty }e^{i\pi \tau u^{2}}{\frac {\cos(2\pi uz+\pi \tau u)}{\sin(\pi u)}}\mathrm {d} u.\end{aligned}}} La función Theta Nullwert es esta identidad integral: θ 3 ( q ) {\displaystyle \theta _{3}(q)}

θ 3 ( q ) = 1 + 4 q ln ( 1 / q ) π ∫ 0 ∞ exp [ − ln ( 1 / q ) x 2 ] { 1 − q 2 cos [ 2 ln ( 1 / q ) x ] } 1 − 2 q 2 cos [ 2 ln ( 1 / q ) x ] + q 4 d x {\displaystyle \theta _{3}(q)=1+{\frac {4q{\sqrt {\ln(1/q)}}}{\sqrt {\pi }}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp[-\ln(1/q)\,x^{2}]\{1-q^{2}\cos[2\ln(1/q)\,x]\}}{1-2q^{2}\cos[2\ln(1/q)\,x]+q^{4}}}\,\mathrm {d} x} Esta fórmula fue discutida en el ensayo Serie Square: transformaciones de funciones generadoras del matemático Maxie Schmidt de Georgia en Atlanta.

En base a esta fórmula se dan los siguientes tres ejemplos eminentes:

[ 2 π K ( 1 2 2 ) ] 1 / 2 = θ 3 [ exp ( − π ) ] = 1 + 4 exp ( − π ) ∫ 0 ∞ exp ( − π x 2 ) [ 1 − exp ( − 2 π ) cos ( 2 π x ) ] 1 − 2 exp ( − 2 π ) cos ( 2 π x ) + exp ( − 4 π ) d x {\displaystyle {\biggl [}{\frac {2}{\pi }}K{\bigl (}{\frac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2}}{\bigr )}{\biggr ]}^{1/2}=\theta _{3}{\bigl [}\exp(-\pi ){\bigr ]}=1+4\exp(-\pi )\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp(-\pi x^{2})[1-\exp(-2\pi )\cos(2\pi x)]}{1-2\exp(-2\pi )\cos(2\pi x)+\exp(-4\pi )}}\,\mathrm {d} x} [ 2 π K ( 2 − 1 ) ] 1 / 2 = θ 3 [ exp ( − 2 π ) ] = 1 + 4 2 4 exp ( − 2 π ) ∫ 0 ∞ exp ( − 2 π x 2 ) [ 1 − exp ( − 2 2 π ) cos ( 2 2 π x ) ] 1 − 2 exp ( − 2 2 π ) cos ( 2 2 π x ) + exp ( − 4 2 π ) d x {\displaystyle {\biggl [}{\frac {2}{\pi }}K({\sqrt {2}}-1){\biggr ]}^{1/2}=\theta _{3}{\bigl [}\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi ){\bigr ]}=1+4\,{\sqrt[{4}]{2}}\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi x^{2})[1-\exp(-2{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\cos(2{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi x)]}{1-2\exp(-2{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\cos(2{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi x)+\exp(-4{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )}}\,\mathrm {d} x} { 2 π K [ sin ( π 12 ) ] } 1 / 2 = θ 3 [ exp ( − 3 π ) ] = 1 + 4 3 4 exp ( − 3 π ) ∫ 0 ∞ exp ( − 3 π x 2 ) [ 1 − exp ( − 2 3 π ) cos ( 2 3 π x ) ] 1 − 2 exp ( − 2 3 π ) cos ( 2 3 π x ) + exp ( − 4 3 π ) d x {\displaystyle {\biggl \{}{\frac {2}{\pi }}K{\bigl [}\sin {\bigl (}{\frac {\pi }{12}}{\bigr )}{\bigr ]}{\biggr \}}^{1/2}=\theta _{3}{\bigl [}\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi ){\bigr ]}=1+4\,{\sqrt[{4}]{3}}\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi x^{2})[1-\exp(-2{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\cos(2{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi x)]}{1-2\exp(-2{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\cos(2{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi x)+\exp(-4{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )}}\,\mathrm {d} x} Además, se mostrarán los ejemplos theta y : θ 3 ( 1 2 ) {\displaystyle \theta _{3}({\tfrac {1}{2}})} θ 3 ( 1 3 ) {\displaystyle \theta _{3}({\tfrac {1}{3}})}

θ 3 ( 1 2 ) = 1 + 2 ∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 2 n 2 = 1 + 2 π − 1 / 2 ln ( 2 ) ∫ 0 ∞ exp [ − ln ( 2 ) x 2 ] { 16 − 4 cos [ 2 ln ( 2 ) x ] } 17 − 8 cos [ 2 ln ( 2 ) x ] d x {\displaystyle \theta _{3}{\bigl (}{\frac {1}{2}}{\bigr )}=1+2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{2^{n^{2}}}}=1+2\pi ^{-1/2}{\sqrt {\ln(2)}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp[-\ln(2)\,x^{2}]\{16-4\cos[2\ln(2)\,x]\}}{17-8\cos[2\ln(2)\,x]}}\,\mathrm {d} x} θ 3 ( 1 2 ) = 2.128936827211877158669 … {\displaystyle \theta _{3}{\bigl (}{\frac {1}{2}}{\bigr )}=2.128936827211877158669\ldots } θ 3 ( 1 3 ) = 1 + 2 ∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 3 n 2 = 1 + 4 3 π − 1 / 2 ln ( 3 ) ∫ 0 ∞ exp [ − ln ( 3 ) x 2 ] { 81 − 9 cos [ 2 ln ( 3 ) x ] } 82 − 18 cos [ 2 ln ( 3 ) x ] d x {\displaystyle \theta _{3}{\bigl (}{\frac {1}{3}}{\bigr )}=1+2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{3^{n^{2}}}}=1+{\frac {4}{3}}\pi ^{-1/2}{\sqrt {\ln(3)}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\exp[-\ln(3)\,x^{2}]\{81-9\cos[2\ln(3)\,x]\}}{82-18\cos[2\ln(3)\,x]}}\,\mathrm {d} x} θ 3 ( 1 3 ) = 1.691459681681715341348 … {\displaystyle \theta _{3}{\bigl (}{\frac {1}{3}}{\bigr )}=1.691459681681715341348\ldots }

Valores explícitos

Valores lemniscaticos El crédito por la mayoría de estos resultados corresponde a Ramanujan. Véase el cuaderno perdido de Ramanujan y una referencia relevante en Función de Euler . Los resultados de Ramanujan citados en Función de Euler más unas pocas operaciones elementales dan los resultados que aparecen a continuación, por lo que están en el cuaderno perdido de Ramanujan o se desprenden inmediatamente de él. Véase también Yi (2004). [4] Defina,

φ ( q ) = ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) = θ 3 ( 0 ; q ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ q n 2 {\displaystyle \quad \varphi (q)=\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )=\theta _{3}(0;q)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{n^{2}}} con el nombre y la función eta de Dedekind Entonces para q = e π i τ , {\displaystyle q=e^{\pi i\tau },} τ = n − 1 , {\displaystyle \tau =n{\sqrt {-1}},} η ( τ ) . {\displaystyle \eta (\tau ).} n = 1 , 2 , 3 , … {\displaystyle n=1,2,3,\dots }

φ ( e − π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) = 2 η ( − 1 ) φ ( e − 2 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 + 2 2 φ ( e − 3 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 1 + 3 108 8 φ ( e − 4 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 + 8 4 4 φ ( e − 5 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 + 5 5 φ ( e − 6 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 1 4 + 3 4 + 4 4 + 9 4 12 3 8 φ ( e − 7 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 13 + 7 + 7 + 3 7 14 3 8 ⋅ 7 16 φ ( e − 8 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 + 2 + 128 8 4 φ ( e − 9 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 1 + 2 + 2 3 3 3 φ ( e − 10 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 64 4 + 80 4 + 81 4 + 100 4 200 4 φ ( e − 11 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 11 + 11 + ( 5 + 3 3 + 11 + 33 ) − 44 + 33 3 3 + ( − 5 + 3 3 − 11 + 33 ) 44 + 33 3 3 52180524 8 φ ( e − 12 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 1 4 + 2 4 + 3 4 + 4 4 + 9 4 + 18 4 + 24 4 2 108 8 φ ( e − 13 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 13 + 8 13 + ( 11 − 6 3 + 13 ) 143 + 78 3 3 + ( 11 + 6 3 + 13 ) 143 − 78 3 3 19773 4 φ ( e − 14 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 13 + 7 + 7 + 3 7 + 10 + 2 7 + 28 8 4 + 7 28 7 16 φ ( e − 15 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 7 + 3 3 + 5 + 15 + 60 4 + 1500 4 12 3 8 ⋅ 5 2 φ ( e − 16 π ) = φ ( e − 4 π ) + π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 1 + 2 4 128 16 φ ( e − 17 π ) = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 ( 1 + 17 4 ) + 17 8 5 + 17 17 + 17 17 2 φ ( e − 20 π ) = φ ( e − 5 π ) + π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 3 + 2 5 4 5 2 6 φ ( e − 36 π ) = 3 φ ( e − 9 π ) + 2 φ ( e − 4 π ) − φ ( e − π ) + π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) 2 4 + 18 4 + 216 4 3 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\varphi \left(e^{-\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}={\sqrt {2}}\,\eta \left({\sqrt {-1}}\right)\\\varphi \left(e^{-2\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {2+{\sqrt {2}}}}{2}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-3\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {1+{\sqrt {3}}}}{\sqrt[{8}]{108}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-4\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {2+{\sqrt[{4}]{8}}}{4}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-5\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\sqrt {\frac {2+{\sqrt {5}}}{5}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-6\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {{\sqrt[{4}]{1}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{3}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{4}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{9}}}}{\sqrt[{8}]{12^{3}}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-7\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {{\sqrt {13+{\sqrt {7}}}}+{\sqrt {7+3{\sqrt {7}}}}}}{{\sqrt[{8}]{14^{3}}}\cdot {\sqrt[{16}]{7}}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-8\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {{\sqrt {2+{\sqrt {2}}}}+{\sqrt[{8}]{128}}}{4}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-9\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {1+{\sqrt[{3}]{2+2{\sqrt {3}}}}}{3}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-10\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {{\sqrt[{4}]{64}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{80}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{81}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{100}}}}{\sqrt[{4}]{200}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-11\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {11+{\sqrt {11}}+(5+3{\sqrt {3}}+{\sqrt {11}}+{\sqrt {33}}){\sqrt[{3}]{-44+33{\sqrt {3}}}}+(-5+3{\sqrt {3}}-{\sqrt {11}}+{\sqrt {33}}){\sqrt[{3}]{44+33{\sqrt {3}}}}}}{\sqrt[{8}]{52180524}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-12\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {{\sqrt[{4}]{1}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{2}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{3}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{4}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{9}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{18}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{24}}}}{2{\sqrt[{8}]{108}}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-13\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {13+8{\sqrt {13}}+(11-6{\sqrt {3}}+{\sqrt {13}}){\sqrt[{3}]{143+78{\sqrt {3}}}}+(11+6{\sqrt {3}}+{\sqrt {13}}){\sqrt[{3}]{143-78{\sqrt {3}}}}}}{\sqrt[{4}]{19773}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-14\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {{\sqrt {13+{\sqrt {7}}}}+{\sqrt {7+3{\sqrt {7}}}}+{\sqrt {10+2{\sqrt {7}}}}+{\sqrt[{8}]{28}}{\sqrt {4+{\sqrt {7}}}}}}{\sqrt[{16}]{28^{7}}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-15\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt {7+3{\sqrt {3}}+{\sqrt {5}}+{\sqrt {15}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{60}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{1500}}}}{{\sqrt[{8}]{12^{3}}}\cdot {\sqrt {5}}}}\\2\varphi \left(e^{-16\pi }\right)&=\varphi \left(e^{-4\pi }\right)+{\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{1+{\sqrt {2}}}}{\sqrt[{16}]{128}}}\\\varphi \left(e^{-17\pi }\right)&={\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\frac {{\sqrt {2}}(1+{\sqrt[{4}]{17}})+{\sqrt[{8}]{17}}{\sqrt {5+{\sqrt {17}}}}}{\sqrt {17+17{\sqrt {17}}}}}\\2\varphi \left(e^{-20\pi }\right)&=\varphi \left(e^{-5\pi }\right)+{\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\sqrt {\frac {3+2{\sqrt[{4}]{5}}}{5{\sqrt {2}}}}}\\6\varphi \left(e^{-36\pi }\right)&=3\varphi \left(e^{-9\pi }\right)+2\varphi \left(e^{-4\pi }\right)-\varphi \left(e^{-\pi }\right)+{\frac {\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}{\Gamma \left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}{\sqrt[{3}]{{\sqrt[{4}]{2}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{18}}+{\sqrt[{4}]{216}}}}\end{aligned}}} Si el recíproco de la constante de Gelfond se eleva a la potencia del recíproco de un número impar, entonces los valores correspondientes se pueden representar de forma simplificada utilizando el seno lemniscático hiperbólico : ϑ 00 {\displaystyle \vartheta _{00}} ϕ {\displaystyle \phi }

φ [ exp ( − 1 5 π ) ] = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) − 1 slh ( 1 5 2 ϖ ) slh ( 2 5 2 ϖ ) {\displaystyle \varphi {\bigl [}\exp(-{\tfrac {1}{5}}\pi ){\bigr ]}={\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}\,{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {3}{4}}\right)}^{-1}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{5}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {2}{5}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}} φ [ exp ( − 1 7 π ) ] = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) − 1 slh ( 1 7 2 ϖ ) slh ( 2 7 2 ϖ ) slh ( 3 7 2 ϖ ) {\displaystyle \varphi {\bigl [}\exp(-{\tfrac {1}{7}}\pi ){\bigr ]}={\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}\,{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {3}{4}}\right)}^{-1}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{7}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {2}{7}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {3}{7}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}} φ [ exp ( − 1 9 π ) ] = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) − 1 slh ( 1 9 2 ϖ ) slh ( 2 9 2 ϖ ) slh ( 3 9 2 ϖ ) slh ( 4 9 2 ϖ ) {\displaystyle \varphi {\bigl [}\exp(-{\tfrac {1}{9}}\pi ){\bigr ]}={\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}\,{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {3}{4}}\right)}^{-1}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{9}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {2}{9}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {3}{9}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {4}{9}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}} φ [ exp ( − 1 11 π ) ] = π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) − 1 slh ( 1 11 2 ϖ ) slh ( 2 11 2 ϖ ) slh ( 3 11 2 ϖ ) slh ( 4 11 2 ϖ ) slh ( 5 11 2 ϖ ) {\displaystyle \varphi {\bigl [}\exp(-{\tfrac {1}{11}}\pi ){\bigr ]}={\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}\,{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {3}{4}}\right)}^{-1}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{11}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {2}{11}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {3}{11}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {4}{11}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}\operatorname {slh} {\bigl (}{\tfrac {5}{11}}{\sqrt {2}}\,\varpi {\bigr )}} Con la letra se representa la constante Lemniscata . ϖ {\displaystyle \varpi }

Tenga en cuenta que se cumplen las siguientes identidades modulares:

2 φ ( q 4 ) = φ ( q ) + 2 φ 2 ( q 2 ) − φ 2 ( q ) 3 φ ( q 9 ) = φ ( q ) + 9 φ 4 ( q 3 ) φ ( q ) − φ 3 ( q ) 3 5 φ ( q 25 ) = φ ( q 5 ) cot ( 1 2 arctan ( 2 5 φ ( q ) φ ( q 5 ) φ 2 ( q ) − φ 2 ( q 5 ) 1 + s ( q ) − s 2 ( q ) s ( q ) ) ) {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}2\varphi \left(q^{4}\right)&=\varphi (q)+{\sqrt {2\varphi ^{2}\left(q^{2}\right)-\varphi ^{2}(q)}}\\3\varphi \left(q^{9}\right)&=\varphi (q)+{\sqrt[{3}]{9{\frac {\varphi ^{4}\left(q^{3}\right)}{\varphi (q)}}-\varphi ^{3}(q)}}\\{\sqrt {5}}\varphi \left(q^{25}\right)&=\varphi \left(q^{5}\right)\cot \left({\frac {1}{2}}\arctan \left({\frac {2}{\sqrt {5}}}{\frac {\varphi (q)\varphi \left(q^{5}\right)}{\varphi ^{2}(q)-\varphi ^{2}\left(q^{5}\right)}}{\frac {1+s(q)-s^{2}(q)}{s(q)}}\right)\right)\end{aligned}}} ¿Dónde está la fracción continua de Rogers-Ramanujan ? s ( q ) = s ( e π i τ ) = − R ( − e − π i / ( 5 τ ) ) {\displaystyle s(q)=s\left(e^{\pi i\tau }\right)=-R\left(-e^{-\pi i/(5\tau )}\right)}

s ( q ) = tan ( 1 2 arctan ( 5 2 φ 2 ( q 5 ) φ 2 ( q ) − 1 2 ) ) cot 2 ( 1 2 arccot ( 5 2 φ 2 ( q 5 ) φ 2 ( q ) − 1 2 ) ) 5 = e − π i / ( 25 τ ) 1 − e − π i / ( 5 τ ) 1 + e − 2 π i / ( 5 τ ) 1 − ⋱ {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}s(q)&={\sqrt[{5}]{\tan \left({\frac {1}{2}}\arctan \left({\frac {5}{2}}{\frac {\varphi ^{2}\left(q^{5}\right)}{\varphi ^{2}(q)}}-{\frac {1}{2}}\right)\right)\cot ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {arccot} \left({\frac {5}{2}}{\frac {\varphi ^{2}\left(q^{5}\right)}{\varphi ^{2}(q)}}-{\frac {1}{2}}\right)\right)}}\\&={\cfrac {e^{-\pi i/(25\tau )}}{1-{\cfrac {e^{-\pi i/(5\tau )}}{1+{\cfrac {e^{-2\pi i/(5\tau )}}{1-\ddots }}}}}}\end{aligned}}}

Equianarmónicovalores El matemático Bruce Berndt descubrió otros valores [5] de la función theta:

φ ( exp ( − 3 π ) ) = π − 1 Γ ( 4 3 ) 3 / 2 2 − 2 / 3 3 13 / 8 φ ( exp ( − 2 3 π ) ) = π − 1 Γ ( 4 3 ) 3 / 2 2 − 2 / 3 3 13 / 8 cos ( 1 24 π ) φ ( exp ( − 3 3 π ) ) = π − 1 Γ ( 4 3 ) 3 / 2 2 − 2 / 3 3 7 / 8 ( 2 3 + 1 ) φ ( exp ( − 4 3 π ) ) = π − 1 Γ ( 4 3 ) 3 / 2 2 − 5 / 3 3 13 / 8 ( 1 + cos ( 1 12 π ) ) φ ( exp ( − 5 3 π ) ) = π − 1 Γ ( 4 3 ) 3 / 2 2 − 2 / 3 3 5 / 8 sin ( 1 5 π ) ( 2 5 100 3 + 2 5 10 3 + 3 5 5 + 1 ) {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lll}\varphi \left(\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1}{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {4}{3}}\right)}^{3/2}2^{-2/3}3^{13/8}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-2{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1}{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {4}{3}}\right)}^{3/2}2^{-2/3}3^{13/8}\cos({\tfrac {1}{24}}\pi )\\\varphi \left(\exp(-3{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1}{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {4}{3}}\right)}^{3/2}2^{-2/3}3^{7/8}({\sqrt[{3}]{2}}+1)\\\varphi \left(\exp(-4{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1}{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {4}{3}}\right)}^{3/2}2^{-5/3}3^{13/8}{\Bigl (}1+{\sqrt {\cos({\tfrac {1}{12}}\pi )}}{\Bigr )}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-5{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1}{\Gamma \left({\tfrac {4}{3}}\right)}^{3/2}2^{-2/3}3^{5/8}\sin({\tfrac {1}{5}}\pi )({\tfrac {2}{5}}{\sqrt[{3}]{100}}+{\tfrac {2}{5}}{\sqrt[{3}]{10}}+{\tfrac {3}{5}}{\sqrt {5}}+1)\end{array}}}

Valores adicionales Muchos valores de la función theta [6] y especialmente de la función phi mostrada se pueden representar en términos de la función gamma:

φ ( exp ( − 2 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 9 8 ) Γ ( 5 4 ) − 1 / 2 2 7 / 8 φ ( exp ( − 2 2 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 9 8 ) Γ ( 5 4 ) − 1 / 2 2 1 / 8 ( 1 + 2 − 1 ) φ ( exp ( − 3 2 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 9 8 ) Γ ( 5 4 ) − 1 / 2 2 3 / 8 3 − 1 / 2 ( 3 + 1 ) tan ( 5 24 π ) φ ( exp ( − 4 2 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 9 8 ) Γ ( 5 4 ) − 1 / 2 2 − 1 / 8 ( 1 + 2 2 − 2 4 ) φ ( exp ( − 5 2 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 9 8 ) Γ ( 5 4 ) − 1 / 2 1 15 2 3 / 8 × × [ 5 3 10 + 2 5 ( 5 + 2 + 3 3 3 + 5 + 2 − 3 3 3 ) − ( 2 − 2 ) 25 − 10 5 ] φ ( exp ( − 6 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 5 24 ) Γ ( 5 12 ) − 1 / 2 2 − 13 / 24 3 − 1 / 8 sin ( 5 12 π ) φ ( exp ( − 1 2 6 π ) ) = π − 1 / 2 Γ ( 5 24 ) Γ ( 5 12 ) − 1 / 2 2 5 / 24 3 − 1 / 8 sin ( 5 24 π ) {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lll}\varphi \left(\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {9}{8}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{4}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{7/8}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-2{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {9}{8}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{4}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{1/8}{\Bigl (}1+{\sqrt {{\sqrt {2}}-1}}{\Bigr )}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-3{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {9}{8}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{4}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{3/8}3^{-1/2}({\sqrt {3}}+1){\sqrt {\tan({\tfrac {5}{24}}\pi )}}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-4{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {9}{8}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{4}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{-1/8}{\Bigl (}1+{\sqrt[{4}]{2{\sqrt {2}}-2}}{\Bigr )}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-5{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {9}{8}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{4}}\right)}^{-1/2}{\frac {1}{15}}\,2^{3/8}\times \\&&\times {\biggl [}{\sqrt[{3}]{5}}\,{\sqrt {10+2{\sqrt {5}}}}{\biggl (}{\sqrt[{3}]{5+{\sqrt {2}}+3{\sqrt {3}}}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{5+{\sqrt {2}}-3{\sqrt {3}}}}\,{\biggr )}-{\bigl (}2-{\sqrt {2}}\,{\bigr )}{\sqrt {25-10{\sqrt {5}}}}\,{\biggr ]}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-{\sqrt {6}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{24}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{12}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{-13/24}3^{-1/8}{\sqrt {\sin({\tfrac {5}{12}}\pi )}}\\\varphi \left(\exp(-{\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {6}}\,\pi )\right)&=&\pi ^{-1/2}\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{24}}\right){\Gamma \left({\tfrac {5}{12}}\right)}^{-1/2}2^{5/24}3^{-1/8}\sin({\tfrac {5}{24}}\pi )\end{array}}}

Teoremas de potencia de nome

Teoremas de potencia directa Para la transformación del nomo [7] en las funciones theta se pueden utilizar estas fórmulas:

θ 2 ( q 2 ) = 1 2 2 [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] {\displaystyle \theta _{2}(q^{2})={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2[\theta _{3}(q)^{2}-\theta _{4}(q)^{2}]}}} θ 3 ( q 2 ) = 1 2 2 [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 + θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] {\displaystyle \theta _{3}(q^{2})={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2[\theta _{3}(q)^{2}+\theta _{4}(q)^{2}]}}} θ 4 ( q 2 ) = θ 4 ( q ) θ 3 ( q ) {\displaystyle \theta _{4}(q^{2})={\sqrt {\theta _{4}(q)\theta _{3}(q)}}} Los cuadrados de las tres funciones theta de valor cero con la función cuadrada como función interna también se forman según el patrón de las ternas pitagóricas según la identidad de Jacobi. Además, esas transformaciones son válidas:

θ 3 ( q 4 ) = 1 2 θ 3 ( q ) + 1 2 θ 4 ( q ) {\displaystyle \theta _{3}(q^{4})={\tfrac {1}{2}}\theta _{3}(q)+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\theta _{4}(q)} Estas fórmulas se pueden utilizar para calcular los valores theta del cubo del nombre:

27 θ 3 ( q 3 ) 8 − 18 θ 3 ( q 3 ) 4 θ 3 ( q ) 4 − θ 3 ( q ) 8 = 8 θ 3 ( q 3 ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 2 [ 2 θ 4 ( q ) 4 − θ 3 ( q ) 4 ] {\displaystyle 27\,\theta _{3}(q^{3})^{8}-18\,\theta _{3}(q^{3})^{4}\theta _{3}(q)^{4}-\,\theta _{3}(q)^{8}=8\,\theta _{3}(q^{3})^{2}\theta _{3}(q)^{2}[2\,\theta _{4}(q)^{4}-\theta _{3}(q)^{4}]} 27 θ 4 ( q 3 ) 8 − 18 θ 4 ( q 3 ) 4 θ 4 ( q ) 4 − θ 4 ( q ) 8 = 8 θ 4 ( q 3 ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 2 [ 2 θ 3 ( q ) 4 − θ 4 ( q ) 4 ] {\displaystyle 27\,\theta _{4}(q^{3})^{8}-18\,\theta _{4}(q^{3})^{4}\theta _{4}(q)^{4}-\,\theta _{4}(q)^{8}=8\,\theta _{4}(q^{3})^{2}\theta _{4}(q)^{2}[2\,\theta _{3}(q)^{4}-\theta _{4}(q)^{4}]} Y se pueden utilizar las siguientes fórmulas para calcular los valores theta de la quinta potencia del nombre:

[ θ 3 ( q ) 2 − θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 ] [ 5 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 − θ 3 ( q ) 2 ] 5 = 256 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 4 [ θ 3 ( q ) 4 − θ 4 ( q ) 4 ] {\displaystyle [\theta _{3}(q)^{2}-\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}][5\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}-\theta _{3}(q)^{2}]^{5}=256\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}\theta _{3}(q)^{2}\theta _{4}(q)^{4}[\theta _{3}(q)^{4}-\theta _{4}(q)^{4}]} [ θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] [ 5 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] 5 = 256 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 4 [ θ 3 ( q ) 4 − θ 4 ( q ) 4 ] {\displaystyle [\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}-\theta _{4}(q)^{2}][5\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}-\theta _{4}(q)^{2}]^{5}=256\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}\theta _{4}(q)^{2}\theta _{3}(q)^{4}[\theta _{3}(q)^{4}-\theta _{4}(q)^{4}]}

Transformación en la raíz cúbica del nombre Las fórmulas para los valores de la función theta Nullwert a partir de la raíz cúbica del nomo elíptico se obtienen contrastando las dos soluciones reales de las ecuaciones cuárticas correspondientes:

[ θ 3 ( q 1 / 3 ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 2 − 3 θ 3 ( q 3 ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 2 ] 2 = 4 − 4 [ 2 θ 2 ( q ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 4 ] 2 / 3 {\displaystyle {\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(q^{1/3})^{2}}{\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}}-{\frac {3\,\theta _{3}(q^{3})^{2}}{\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}}{\biggr ]}^{2}=4-4{\biggl [}{\frac {2\,\theta _{2}(q)^{2}\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}{\theta _{3}(q)^{4}}}{\biggr ]}^{2/3}} [ 3 θ 4 ( q 3 ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 2 − θ 4 ( q 1 / 3 ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] 2 = 4 + 4 [ 2 θ 2 ( q ) 2 θ 3 ( q ) 2 θ 4 ( q ) 4 ] 2 / 3 {\displaystyle {\biggl [}{\frac {3\,\theta _{4}(q^{3})^{2}}{\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q^{1/3})^{2}}{\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}}{\biggr ]}^{2}=4+4{\biggl [}{\frac {2\,\theta _{2}(q)^{2}\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}{\theta _{4}(q)^{4}}}{\biggr ]}^{2/3}}

Transformación en la quinta raíz del nomo La fracción continua de Rogers-Ramanujan se puede definir en términos de la función theta de Jacobi de la siguiente manera:

R ( q ) = tan { 1 2 arctan [ 1 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 2 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 ] } 1 / 5 tan { 1 2 arccot [ 1 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 2 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 ] } 2 / 5 {\displaystyle R(q)=\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\arctan {\biggl [}{\frac {1}{2}}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{1/5}\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {arccot} {\biggl [}{\frac {1}{2}}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{2/5}} R ( q 2 ) = tan { 1 2 arctan [ 1 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 2 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 ] } 2 / 5 cot { 1 2 arccot [ 1 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 2 θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 ] } 1 / 5 {\displaystyle R(q^{2})=\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\arctan {\biggl [}{\frac {1}{2}}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{2/5}\cot {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {arccot} {\biggl [}{\frac {1}{2}}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{1/5}} R ( q 2 ) = tan { 1 2 arctan [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 2 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 − 1 2 ] } 2 / 5 tan { 1 2 arccot [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 2 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 − 1 2 ] } 1 / 5 {\displaystyle R(q^{2})=\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\arctan {\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{2}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{2/5}\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {arccot} {\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{2}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{1/5}} La función de fracción continua alternada de Rogers-Ramanujan S(q) tiene las dos identidades siguientes:

S ( q ) = R ( q 4 ) R ( q 2 ) R ( q ) = tan { 1 2 arctan [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 2 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 − 1 2 ] } 1 / 5 cot { 1 2 arccot [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 2 θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 − 1 2 ] } 2 / 5 {\displaystyle S(q)={\frac {R(q^{4})}{R(q^{2})R(q)}}=\tan {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\arctan {\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{2}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{1/5}\cot {\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2}}\operatorname {arccot} {\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(q)^{2}}{2\,\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}}}-{\frac {1}{2}}{\biggr ]}{\biggr \}}^{2/5}} Los valores de la función theta de la quinta raíz del nombre se pueden representar como una combinación racional de las fracciones continuas R y S y los valores de la función theta de la quinta potencia del nombre y el nombre mismo. Las siguientes cuatro ecuaciones son válidas para todos los valores q entre 0 y 1:

θ 3 ( q 1 / 5 ) θ 3 ( q 5 ) − 1 = 1 S ( q ) [ S ( q ) 2 + R ( q 2 ) ] [ 1 + R ( q 2 ) S ( q ) ] {\displaystyle {\frac {\theta _{3}(q^{1/5})}{\theta _{3}(q^{5})}}-1={\frac {1}{S(q)}}{\bigl [}S(q)^{2}+R(q^{2}){\bigr ]}{\bigl [}1+R(q^{2})S(q){\bigr ]}} 1 − θ 4 ( q 1 / 5 ) θ 4 ( q 5 ) = 1 R ( q ) [ R ( q 2 ) + R ( q ) 2 ] [ 1 − R ( q 2 ) R ( q ) ] {\displaystyle 1-{\frac {\theta _{4}(q^{1/5})}{\theta _{4}(q^{5})}}={\frac {1}{R(q)}}{\bigl [}R(q^{2})+R(q)^{2}{\bigr ]}{\bigl [}1-R(q^{2})R(q){\bigr ]}} θ 3 ( q 1 / 5 ) 2 − θ 3 ( q ) 2 = [ θ 3 ( q ) 2 − θ 3 ( q 5 ) 2 ] [ 1 + 1 R ( q 2 ) S ( q ) + R ( q 2 ) S ( q ) + 1 R ( q 2 ) 2 + R ( q 2 ) 2 + 1 S ( q ) − S ( q ) ] {\displaystyle \theta _{3}(q^{1/5})^{2}-\theta _{3}(q)^{2}={\bigl [}\theta _{3}(q)^{2}-\theta _{3}(q^{5})^{2}{\bigr ]}{\biggl [}1+{\frac {1}{R(q^{2})S(q)}}+R(q^{2})S(q)+{\frac {1}{R(q^{2})^{2}}}+R(q^{2})^{2}+{\frac {1}{S(q)}}-S(q){\biggr ]}} θ 4 ( q ) 2 − θ 4 ( q 1 / 5 ) 2 = [ θ 4 ( q 5 ) 2 − θ 4 ( q ) 2 ] [ 1 − 1 R ( q 2 ) R ( q ) − R ( q 2 ) R ( q ) + 1 R ( q 2 ) 2 + R ( q 2 ) 2 − 1 R ( q ) + R ( q ) ] {\displaystyle \theta _{4}(q)^{2}-\theta _{4}(q^{1/5})^{2}={\bigl [}\theta _{4}(q^{5})^{2}-\theta _{4}(q)^{2}{\bigr ]}{\biggl [}1-{\frac {1}{R(q^{2})R(q)}}-R(q^{2})R(q)+{\frac {1}{R(q^{2})^{2}}}+R(q^{2})^{2}-{\frac {1}{R(q)}}+R(q){\biggr ]}}

Teoremas dependientes del módulo En combinación con el módulo elíptico, se pueden mostrar las siguientes fórmulas:

Estas son las fórmulas para el cuadrado del nomo elíptico:

θ 4 [ q ( k ) ] = θ 4 [ q ( k ) 2 ] 1 − k 2 8 {\displaystyle \theta _{4}[q(k)]=\theta _{4}[q(k)^{2}]{\sqrt[{8}]{1-k^{2}}}} θ 4 [ q ( k ) 2 ] = θ 3 [ q ( k ) ] 1 − k 2 8 {\displaystyle \theta _{4}[q(k)^{2}]=\theta _{3}[q(k)]{\sqrt[{8}]{1-k^{2}}}} θ 3 [ q ( k ) 2 ] = θ 3 [ q ( k ) ] cos [ 1 2 arcsin ( k ) ] {\displaystyle \theta _{3}[q(k)^{2}]=\theta _{3}[q(k)]\cos[{\tfrac {1}{2}}\arcsin(k)]} Y esta es una fórmula eficiente para el cubo del nombre:

θ 4 ⟨ q { tan [ 1 2 arctan ( t 3 ) ] } 3 ⟩ = θ 4 ⟨ q { tan [ 1 2 arctan ( t 3 ) ] } ⟩ 3 − 1 / 2 ( 2 t 4 − t 2 + 1 − t 2 + 2 + t 2 + 1 ) 1 / 2 {\displaystyle \theta _{4}{\biggl \langle }q{\bigl \{}\tan {\bigl [}{\tfrac {1}{2}}\arctan(t^{3}){\bigr ]}{\bigr \}}^{3}{\biggr \rangle }=\theta _{4}{\biggl \langle }q{\bigl \{}\tan {\bigl [}{\tfrac {1}{2}}\arctan(t^{3}){\bigr ]}{\bigr \}}{\biggr \rangle }\,3^{-1/2}{\bigl (}{\sqrt {2{\sqrt {t^{4}-t^{2}+1}}-t^{2}+2}}+{\sqrt {t^{2}+1}}\,{\bigr )}^{1/2}} Para todos los valores reales es válida la fórmula ahora mencionada. t ∈ R {\displaystyle t\in \mathbb {R} }

Y para esta fórmula se darán dos ejemplos:

Primer ejemplo de cálculo con el valor insertado: t = 1 {\displaystyle t=1}

Segundo ejemplo de cálculo con el valor insertado: t = Φ − 2 {\displaystyle t=\Phi ^{-2}}

La constante representa exactamente el número de proporción áurea . Φ {\displaystyle \Phi } Φ = 1 2 ( 5 + 1 ) {\displaystyle \Phi ={\tfrac {1}{2}}({\sqrt {5}}+1)}

Algunas identidades de la serie

Sumas con función theta en el resultado La suma infinita [8] [9] de los recíprocos de los números de Fibonacci con índices impares tiene esta identidad:

∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 F 2 n − 1 = 5 2 ∑ n = 1 ∞ 2 ( Φ − 2 ) n − 1 / 2 1 + ( Φ − 2 ) 2 n − 1 = 5 4 ∑ a = − ∞ ∞ 2 ( Φ − 2 ) a − 1 / 2 1 + ( Φ − 2 ) 2 a − 1 = {\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{F_{2n-1}}}={\frac {\sqrt {5}}{2}}\,\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {2(\Phi ^{-2})^{n-1/2}}{1+(\Phi ^{-2})^{2n-1}}}={\frac {\sqrt {5}}{4}}\sum _{a=-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {2(\Phi ^{-2})^{a-1/2}}{1+(\Phi ^{-2})^{2a-1}}}=} = 5 4 θ 2 ( Φ − 2 ) 2 = 5 8 [ θ 3 ( Φ − 1 ) 2 − θ 4 ( Φ − 1 ) 2 ] {\displaystyle ={\frac {\sqrt {5}}{4}}\,\theta _{2}(\Phi ^{-2})^{2}={\frac {\sqrt {5}}{8}}{\bigl [}\theta _{3}(\Phi ^{-1})^{2}-\theta _{4}(\Phi ^{-1})^{2}{\bigr ]}} Al no utilizar la expresión de la función theta, se puede formular la siguiente identidad entre dos sumas:

∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 F 2 n − 1 = 5 4 [ ∑ n = 1 ∞ 2 Φ − ( 2 n − 1 ) 2 / 2 ] 2 {\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{F_{2n-1}}}={\frac {\sqrt {5}}{4}}\,{\biggl [}\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }2\,\Phi ^{-(2n-1)^{2}/2}{\biggr ]}^{2}} ∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 F 2 n − 1 = 1.82451515740692456814215840626732817332 … {\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{F_{2n-1}}}=1.82451515740692456814215840626732817332\ldots } También en este caso se trata nuevamente del número de proporción áurea . Φ = 1 2 ( 5 + 1 ) {\displaystyle \Phi ={\tfrac {1}{2}}({\sqrt {5}}+1)}

Suma infinita de los recíprocos de los cuadrados de los números de Fibonacci:

∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 F n 2 = 5 24 [ 2 θ 2 ( Φ − 2 ) 4 − θ 3 ( Φ − 2 ) 4 + 1 ] = 5 24 [ θ 3 ( Φ − 2 ) 4 − 2 θ 4 ( Φ − 2 ) 4 + 1 ] {\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{F_{n}^{2}}}={\frac {5}{24}}{\bigl [}2\,\theta _{2}(\Phi ^{-2})^{4}-\theta _{3}(\Phi ^{-2})^{4}+1{\bigr ]}={\frac {5}{24}}{\bigl [}\theta _{3}(\Phi ^{-2})^{4}-2\,\theta _{4}(\Phi ^{-2})^{4}+1{\bigr ]}} Suma infinita de los recíprocos de los números de Pell con índices impares:

∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 P 2 n − 1 = 1 2 θ 2 [ ( 2 − 1 ) 2 ] 2 = 1 2 2 [ θ 3 ( 2 − 1 ) 2 − θ 4 ( 2 − 1 ) 2 ] {\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{P_{2n-1}}}={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\,\theta _{2}{\bigl [}({\sqrt {2}}-1)^{2}{\bigr ]}^{2}={\frac {1}{2{\sqrt {2}}}}{\bigl [}\theta _{3}({\sqrt {2}}-1)^{2}-\theta _{4}({\sqrt {2}}-1)^{2}{\bigr ]}}

Sumas con función theta en el sumando Las siguientes dos identidades de serie fueron demostradas por István Mező: [10]

θ 4 2 ( q ) = i q 1 4 ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ q 2 k 2 − k θ 1 ( 2 k − 1 2 i ln q , q ) , θ 4 2 ( q ) = ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ q 2 k 2 θ 4 ( k ln q i , q ) . {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\theta _{4}^{2}(q)&=iq^{\frac {1}{4}}\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{2k^{2}-k}\theta _{1}\left({\frac {2k-1}{2i}}\ln q,q\right),\\[6pt]\theta _{4}^{2}(q)&=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }q^{2k^{2}}\theta _{4}\left({\frac {k\ln q}{i}},q\right).\end{aligned}}} Estas relaciones se cumplen para todos los valores 0 < q < 1. Especializando los valores de q , tenemos las siguientes sumas libres de parámetros

π e π 2 ⋅ 1 Γ 2 ( 3 4 ) = i ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ e π ( k − 2 k 2 ) θ 1 ( i π 2 ( 2 k − 1 ) , e − π ) {\displaystyle {\sqrt {\frac {\pi {\sqrt {e^{\pi }}}}{2}}}\cdot {\frac {1}{\Gamma ^{2}\left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}=i\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }e^{\pi \left(k-2k^{2}\right)}\theta _{1}\left({\frac {i\pi }{2}}(2k-1),e^{-\pi }\right)} π 2 ⋅ 1 Γ 2 ( 3 4 ) = ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ θ 4 ( i k π , e − π ) e 2 π k 2 {\displaystyle {\sqrt {\frac {\pi }{2}}}\cdot {\frac {1}{\Gamma ^{2}\left({\frac {3}{4}}\right)}}=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {\theta _{4}\left(ik\pi ,e^{-\pi }\right)}{e^{2\pi k^{2}}}}}

Ceros de las funciones theta de Jacobi Todos los ceros de las funciones theta de Jacobi son ceros simples y se dan de la siguiente manera:

ϑ ( z ; τ ) = ϑ 00 ( z ; τ ) = 0 ⟺ z = m + n τ + 1 2 + τ 2 ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) = 0 ⟺ z = m + n τ ϑ 10 ( z ; τ ) = 0 ⟺ z = m + n τ + 1 2 ϑ 01 ( z ; τ ) = 0 ⟺ z = m + n τ + τ 2 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\vartheta (z;\tau )=\vartheta _{00}(z;\tau )&=0\quad &\Longleftrightarrow &&\quad z&=m+n\tau +{\frac {1}{2}}+{\frac {\tau }{2}}\\[3pt]\vartheta _{11}(z;\tau )&=0\quad &\Longleftrightarrow &&\quad z&=m+n\tau \\[3pt]\vartheta _{10}(z;\tau )&=0\quad &\Longleftrightarrow &&\quad z&=m+n\tau +{\frac {1}{2}}\\[3pt]\vartheta _{01}(z;\tau )&=0\quad &\Longleftrightarrow &&\quad z&=m+n\tau +{\frac {\tau }{2}}\end{aligned}}} donde m , n son números enteros arbitrarios.

Relación con la función zeta de Riemann La relación

ϑ ( 0 ; − 1 τ ) = ( − i τ ) 1 2 ϑ ( 0 ; τ ) {\displaystyle \vartheta \left(0;-{\frac {1}{\tau }}\right)=\left(-i\tau \right)^{\frac {1}{2}}\vartheta (0;\tau )} Fue utilizado por Riemann para demostrar la ecuación funcional de la función zeta de Riemann , mediante la transformada de Mellin.

Γ ( s 2 ) π − s 2 ζ ( s ) = 1 2 ∫ 0 ∞ ( ϑ ( 0 ; i t ) − 1 ) t s 2 d t t {\displaystyle \Gamma \left({\frac {s}{2}}\right)\pi ^{-{\frac {s}{2}}}\zeta (s)={\frac {1}{2}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\bigl (}\vartheta (0;it)-1{\bigr )}t^{\frac {s}{2}}{\frac {\mathrm {d} t}{t}}} que se puede demostrar que es invariante bajo la sustitución de s por 1 − s . La integral correspondiente para z ≠ 0función zeta de Hurwitz .

Relación con la función elíptica de Weierstrass La función theta fue utilizada por Jacobi para construir (en una forma adaptada a un cálculo fácil) sus funciones elípticas como cocientes de las cuatro funciones theta anteriores, y podría haber sido utilizada por él también para construir las funciones elípticas de Weierstrass , ya que

℘ ( z ; τ ) = − ( log ϑ 11 ( z ; τ ) ) ″ + c {\displaystyle \wp (z;\tau )=-{\big (}\log \vartheta _{11}(z;\tau ){\big )}''+c} donde la segunda derivada es con respecto a z y la constante c está definida de modo que la expansión de Laurent de ℘( z ) en z = 0

Relación con elq-función gamma La cuarta función theta –y por lo tanto las demás también– está íntimamente conectada con la función q -gamma de Jackson a través de la relación [11].

( Γ q 2 ( x ) Γ q 2 ( 1 − x ) ) − 1 = q 2 x ( 1 − x ) ( q − 2 ; q − 2 ) ∞ 3 ( q 2 − 1 ) θ 4 ( 1 2 i ( 1 − 2 x ) log q , 1 q ) . {\displaystyle \left(\Gamma _{q^{2}}(x)\Gamma _{q^{2}}(1-x)\right)^{-1}={\frac {q^{2x(1-x)}}{\left(q^{-2};q^{-2}\right)_{\infty }^{3}\left(q^{2}-1\right)}}\theta _{4}\left({\frac {1}{2i}}(1-2x)\log q,{\frac {1}{q}}\right).}

Relaciones con la función eta de Dedekind Sea η ( τ )función eta de Dedekind y el argumento de la función theta el nombre q = e πiτ

θ 2 ( q ) = ϑ 10 ( 0 ; τ ) = 2 η 2 ( 2 τ ) η ( τ ) , θ 3 ( q ) = ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) = η 5 ( τ ) η 2 ( 1 2 τ ) η 2 ( 2 τ ) = η 2 ( 1 2 ( τ + 1 ) ) η ( τ + 1 ) , θ 4 ( q ) = ϑ 01 ( 0 ; τ ) = η 2 ( 1 2 τ ) η ( τ ) , {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\theta _{2}(q)=\vartheta _{10}(0;\tau )&={\frac {2\eta ^{2}(2\tau )}{\eta (\tau )}},\\[3pt]\theta _{3}(q)=\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )&={\frac {\eta ^{5}(\tau )}{\eta ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{2}}\tau \right)\eta ^{2}(2\tau )}}={\frac {\eta ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{2}}(\tau +1)\right)}{\eta (\tau +1)}},\\[3pt]\theta _{4}(q)=\vartheta _{01}(0;\tau )&={\frac {\eta ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{2}}\tau \right)}{\eta (\tau )}},\end{aligned}}} y,

θ 2 ( q ) θ 3 ( q ) θ 4 ( q ) = 2 η 3 ( τ ) . {\displaystyle \theta _{2}(q)\,\theta _{3}(q)\,\theta _{4}(q)=2\eta ^{3}(\tau ).} Véase también las funciones modulares de Weber .

Módulo elíptico El módulo elíptico es

k ( τ ) = ϑ 10 ( 0 ; τ ) 2 ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) 2 {\displaystyle k(\tau )={\frac {\vartheta _{10}(0;\tau )^{2}}{\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )^{2}}}} y el módulo elíptico complementario es

k ′ ( τ ) = ϑ 01 ( 0 ; τ ) 2 ϑ 00 ( 0 ; τ ) 2 {\displaystyle k'(\tau )={\frac {\vartheta _{01}(0;\tau )^{2}}{\vartheta _{00}(0;\tau )^{2}}}}

Derivadas de funciones theta Éstas son dos definiciones idénticas de la integral elíptica completa de segundo tipo:

E ( k ) = ∫ 0 π / 2 1 − k 2 sin ( φ ) 2 d φ {\displaystyle E(k)=\int _{0}^{\pi /2}{\sqrt {1-k^{2}\sin(\varphi )^{2}}}d\varphi } E ( k ) = π 2 ∑ a = 0 ∞ [ ( 2 a ) ! ] 2 ( 1 − 2 a ) 16 a ( a ! ) 4 k 2 a {\displaystyle E(k)={\frac {\pi }{2}}\sum _{a=0}^{\infty }{\frac {[(2a)!]^{2}}{(1-2a)16^{a}(a!)^{4}}}k^{2a}} Las derivadas de las funciones Theta Nullwert tienen estas series de MacLaurin:

θ 2 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 2 ( x ) = 1 2 x − 3 / 4 + ∑ n = 1 ∞ 1 2 ( 2 n + 1 ) 2 x ( 2 n − 1 ) ( 2 n + 3 ) / 4 {\displaystyle \theta _{2}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{2}(x)={\frac {1}{2}}x^{-3/4}+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{2}}(2n+1)^{2}x^{(2n-1)(2n+3)/4}} θ 3 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 3 ( x ) = 2 + ∑ n = 1 ∞ 2 ( n + 1 ) 2 x n ( n + 2 ) {\displaystyle \theta _{3}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{3}(x)=2+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }2(n+1)^{2}x^{n(n+2)}} θ 4 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 4 ( x ) = − 2 + ∑ n = 1 ∞ 2 ( n + 1 ) 2 ( − 1 ) n + 1 x n ( n + 2 ) {\displaystyle \theta _{4}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{4}(x)=-2+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }2(n+1)^{2}(-1)^{n+1}x^{n(n+2)}} Las derivadas de las funciones theta de valor cero [12] son las siguientes:

θ 2 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 2 ( x ) = 1 2 π x θ 2 ( x ) θ 3 ( x ) 2 E [ θ 2 ( x ) 2 θ 3 ( x ) 2 ] {\displaystyle \theta _{2}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{2}(x)={\frac {1}{2\pi x}}\theta _{2}(x)\theta _{3}(x)^{2}E{\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{2}(x)^{2}}{\theta _{3}(x)^{2}}}{\biggr ]}} θ 3 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 3 ( x ) = θ 3 ( x ) [ θ 3 ( x ) 2 + θ 4 ( x ) 2 ] { 1 2 π x E [ θ 3 ( x ) 2 − θ 4 ( x ) 2 θ 3 ( x ) 2 + θ 4 ( x ) 2 ] − θ 4 ( x ) 2 4 x } {\displaystyle \theta _{3}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{3}(x)=\theta _{3}(x){\bigl [}\theta _{3}(x)^{2}+\theta _{4}(x)^{2}{\bigr ]}{\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2\pi x}}E{\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{2}-\theta _{4}(x)^{2}}{\theta _{3}(x)^{2}+\theta _{4}(x)^{2}}}{\biggr ]}-{\frac {\theta _{4}(x)^{2}}{4\,x}}{\biggr \}}} θ 4 ′ ( x ) = d d x θ 4 ( x ) = θ 4 ( x ) [ θ 3 ( x ) 2 + θ 4 ( x ) 2 ] { 1 2 π x E [ θ 3 ( x ) 2 − θ 4 ( x ) 2 θ 3 ( x ) 2 + θ 4 ( x ) 2 ] − θ 3 ( x ) 2 4 x } {\displaystyle \theta _{4}'(x)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{4}(x)=\theta _{4}(x){\bigl [}\theta _{3}(x)^{2}+\theta _{4}(x)^{2}{\bigr ]}{\biggl \{}{\frac {1}{2\pi x}}E{\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{2}-\theta _{4}(x)^{2}}{\theta _{3}(x)^{2}+\theta _{4}(x)^{2}}}{\biggr ]}-{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{2}}{4\,x}}{\biggr \}}} Las dos últimas fórmulas mencionadas son válidas para todos los números reales del intervalo de definición real: − 1 < x < 1 ∩ x ∈ R {\displaystyle -1<x<1\,\cap \,x\in \mathbb {R} }

Y estas dos últimas funciones derivadas theta están relacionadas entre sí de esta manera:

ϑ 4 ( x ) [ d d x ϑ 3 ( x ) ] − ϑ 3 ( x ) [ d d x θ 4 ( x ) ] = 1 4 x θ 3 ( x ) θ 4 ( x ) [ θ 3 ( x ) 4 − θ 4 ( x ) 4 ] {\displaystyle \vartheta _{4}(x){\biggl [}{\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\vartheta _{3}(x){\biggr ]}-\vartheta _{3}(x){\biggl [}{\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,\theta _{4}(x){\biggr ]}={\frac {1}{4\,x}}\,\theta _{3}(x)\,\theta _{4}(x){\bigl [}\theta _{3}(x)^{4}-\theta _{4}(x)^{4}{\bigr ]}} Las derivadas de los cocientes de dos de las tres funciones theta mencionadas aquí siempre tienen una relación racional con esas tres funciones:

d d x θ 2 ( x ) θ 3 ( x ) = θ 2 ( x ) θ 4 ( x ) 4 4 x θ 3 ( x ) {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,{\frac {\theta _{2}(x)}{\theta _{3}(x)}}={\frac {\theta _{2}(x)\,\theta _{4}(x)^{4}}{4\,x\,\theta _{3}(x)}}} d d x θ 2 ( x ) θ 4 ( x ) = θ 2 ( x ) θ 3 ( x ) 4 4 x θ 4 ( x ) {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,{\frac {\theta _{2}(x)}{\theta _{4}(x)}}={\frac {\theta _{2}(x)\,\theta _{3}(x)^{4}}{4\,x\,\theta _{4}(x)}}} d d x θ 3 ( x ) θ 4 ( x ) = θ 3 ( x ) 5 − θ 3 ( x ) θ 4 ( x ) 4 4 x θ 4 ( x ) {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} x}}\,{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)}{\theta _{4}(x)}}={\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{5}-\theta _{3}(x)\,\theta _{4}(x)^{4}}{4\,x\,\theta _{4}(x)}}} Para la derivación de estas fórmulas de derivación, consulte los artículos Nombre (matemáticas) y Función lambda modular .

Integrales de funciones theta Para las funciones theta son válidas estas integrales [13] :

∫ 0 1 θ 2 ( x ) d x = ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ 4 ( 2 k + 1 ) 2 + 4 = π tanh ( π ) ≈ 3.129881 {\displaystyle \int _{0}^{1}\theta _{2}(x)\,\mathrm {d} x=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {4}{(2k+1)^{2}+4}}=\pi \tanh(\pi )\approx 3.129881} ∫ 0 1 θ 3 ( x ) d x = ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ 1 k 2 + 1 = π coth ( π ) ≈ 3.153348 {\displaystyle \int _{0}^{1}\theta _{3}(x)\,\mathrm {d} x=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {1}{k^{2}+1}}=\pi \coth(\pi )\approx 3.153348} ∫ 0 1 θ 4 ( x ) d x = ∑ k = − ∞ ∞ ( − 1 ) k k 2 + 1 = π csch ( π ) ≈ 0.272029 {\displaystyle \int _{0}^{1}\theta _{4}(x)\,\mathrm {d} x=\sum _{k=-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{k}}{k^{2}+1}}=\pi \,\operatorname {csch} (\pi )\approx 0.272029} Los resultados finales que se muestran ahora se basan en las fórmulas generales de suma de Cauchy.

Una solución a la ecuación del calor La función theta de Jacobi es la solución fundamental de la ecuación de calor unidimensional con condiciones de contorno periódicas espaciales. [14] Tomando z = x τ = it t real y positivo, podemos escribir

ϑ ( x ; i t ) = 1 + 2 ∑ n = 1 ∞ exp ( − π n 2 t ) cos ( 2 π n x ) {\displaystyle \vartheta (x;it)=1+2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\exp \left(-\pi n^{2}t\right)\cos(2\pi nx)} que resuelve la ecuación del calor

∂ ∂ t ϑ ( x ; i t ) = 1 4 π ∂ 2 ∂ x 2 ϑ ( x ; i t ) . {\displaystyle {\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}\vartheta (x;it)={\frac {1}{4\pi }}{\frac {\partial ^{2}}{\partial x^{2}}}\vartheta (x;it).} Esta solución de función theta es 1-periódica en x , y cuando t → 0función delta periódica , o peine de Dirac , en el sentido de distribuciones .

lim t → 0 ϑ ( x ; i t ) = ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ δ ( x − n ) {\displaystyle \lim _{t\to 0}\vartheta (x;it)=\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\delta (x-n)} Se pueden obtener soluciones generales del problema del valor inicial espacialmente periódico para la ecuación de calor convolucionando los datos iniciales en t = 0

Relación con el grupo de Heisenberg La función theta de Jacobi es invariante bajo la acción de un subgrupo discreto del grupo de Heisenberg . Esta invariancia se presenta en el artículo sobre la representación theta del grupo de Heisenberg.

Generalizaciones Si F es una forma cuadrática en n variables, entonces la función theta asociada con F es

θ F ( z ) = ∑ m ∈ Z n e 2 π i z F ( m ) {\displaystyle \theta _{F}(z)=\sum _{m\in \mathbb {Z} ^{n}}e^{2\pi izF(m)}} con la suma extendiéndose sobre la red de números enteros . Esta función theta es una forma modular de peso . Z n {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} ^{n}} norte / 2 grupo modular . En la expansión de Fourier,

θ ^ F ( z ) = ∑ k = 0 ∞ R F ( k ) e 2 π i k z , {\displaystyle {\hat {\theta }}_{F}(z)=\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }R_{F}(k)e^{2\pi ikz},} Los números R F ( k )números de representación de la forma.

Serie theta de un carácter de Dirichlet Para χ un carácter de Dirichlet primitivo módulo q y ν = 1 − χ (−1) / 2

θ χ ( z ) = 1 2 ∑ n = − ∞ ∞ χ ( n ) n ν e 2 i π n 2 z {\displaystyle \theta _{\chi }(z)={\frac {1}{2}}\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }\chi (n)n^{\nu }e^{2i\pi n^{2}z}} es un peso 1 / 2 ν 4 q 2 y carácter

χ ( d ) ( − 1 d ) ν , {\displaystyle \chi (d)\left({\frac {-1}{d}}\right)^{\nu },} lo que significa [15]

θ χ ( a z + b c z + d ) = χ ( d ) ( − 1 d ) ν ( θ 1 ( a z + b c z + d ) θ 1 ( z ) ) 1 + 2 ν θ χ ( z ) {\displaystyle \theta _{\chi }\left({\frac {az+b}{cz+d}}\right)=\chi (d)\left({\frac {-1}{d}}\right)^{\nu }\left({\frac {\theta _{1}\left({\frac {az+b}{cz+d}}\right)}{\theta _{1}(z)}}\right)^{1+2\nu }\theta _{\chi }(z)} cuando sea

a , b , c , d ∈ Z 4 , a d − b c = 1 , c ≡ 0 mod 4 q 2 . {\displaystyle a,b,c,d\in \mathbb {Z} ^{4},ad-bc=1,c\equiv 0{\bmod {4}}q^{2}.}

Función theta de Ramanujan

Función theta de Riemann Dejar

H n = { F ∈ M ( n , C ) | F = F T , Im F > 0 } {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} _{n}=\left\{F\in M(n,\mathbb {C} )\,{\big |}\,F=F^{\mathsf {T}}\,,\,\operatorname {Im} F>0\right\}} sea el conjunto de matrices cuadradas simétricas cuya parte imaginaria es definida positiva . se llama semiespacio superior de Siegel y es el análogo multidimensional del semiplano superior . El análogo n -dimensional del grupo modular es el grupo simpléctico Sp(2 n , ) ; para n = 1 , Sp(2, ) = SL(2, ) . El análogo n -dimensional de los subgrupos de congruencia lo desempeña H n {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} _{n}} Z {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} } Z {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} } Z {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} }

ker { Sp ( 2 n , Z ) → Sp ( 2 n , Z / k Z ) } . {\displaystyle \ker {\big \{}\operatorname {Sp} (2n,\mathbb {Z} )\to \operatorname {Sp} (2n,\mathbb {Z} /k\mathbb {Z} ){\big \}}.} Entonces, dado τ ∈ H n {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} _{n}} función theta de Riemann se define como

θ ( z , τ ) = ∑ m ∈ Z n exp ( 2 π i ( 1 2 m T τ m + m T z ) ) . {\displaystyle \theta (z,\tau )=\sum _{m\in \mathbb {Z} ^{n}}\exp \left(2\pi i\left({\tfrac {1}{2}}m^{\mathsf {T}}\tau m+m^{\mathsf {T}}z\right)\right).} Aquí, z ∈ C n {\displaystyle \mathbb {C} ^{n}} n -dimensional, y el superíndice T denota la transpuesta . La función theta de Jacobi es entonces un caso especial, con n = 1τ ∈ H {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} } semiplano superior . Una aplicación importante de la función theta de Riemann es que permite dar fórmulas explícitas para funciones meromórficas en superficies compactas de Riemann , así como otros objetos auxiliares que figuran prominentemente en su teoría de funciones, al tomar τ como la matriz de período con respecto a una base canónica para su primer grupo de homología . H {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} }

La theta de Riemann converge de manera absoluta y uniforme en subconjuntos compactos de . C n × H n {\displaystyle \mathbb {C} ^{n}\times \mathbb {H} _{n}}

La ecuación funcional es

θ ( z + a + τ b , τ ) = exp ( 2 π i ( − b T z − 1 2 b T τ b ) ) θ ( z , τ ) {\displaystyle \theta (z+a+\tau b,\tau )=\exp \left(2\pi i\left(-b^{\mathsf {T}}z-{\tfrac {1}{2}}b^{\mathsf {T}}\tau b\right)\right)\theta (z,\tau )} lo cual es válido para todos los vectores a , b ∈ Z n {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} ^{n}} los z ∈ C n {\displaystyle \mathbb {C} ^{n}} τ ∈ H n {\displaystyle \mathbb {H} _{n}}

Serie de Poincaré La serie de Poincaré generaliza la serie theta a formas automórficas con respecto a grupos fuchsianos arbitrarios .

Derivación de los valores theta

Identidad de la función beta de Euler A continuación se derivarán como ejemplos tres valores importantes de la función theta:

Así se define la función beta de Euler en su forma reducida:

β ( x ) = Γ ( x ) 2 Γ ( 2 x ) {\displaystyle \beta (x)={\frac {\Gamma (x)^{2}}{\Gamma (2x)}}} En general, para todos los números naturales esta fórmula de la función beta de Euler es válida: n ∈ N {\displaystyle n\in \mathbb {N} }

4 − 1 / ( n + 2 ) n + 2 csc ( π n + 2 ) β [ n 2 ( n + 2 ) ] = ∫ 0 ∞ 1 x n + 2 + 1 d x {\displaystyle {\frac {4^{-1/(n+2)}}{n+2}}\csc {\bigl (}{\frac {\pi }{n+2}}{\bigr )}\beta {\biggl [}{\frac {n}{2(n+2)}}{\biggr ]}=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{\sqrt {x^{n+2}+1}}}\,\mathrm {d} x}

Integrales elípticas ejemplares A continuación se derivan algunos valores singulares integrales elípticos [16] :

Combinación de las identidades integrales con el nomo La función noma elíptica tiene estos valores importantes:

q ( 1 2 2 ) = exp ( − π ) {\displaystyle q({\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2}})=\exp(-\pi )} q [ 1 4 ( 6 − 2 ) ] = exp ( − 3 π ) {\displaystyle q[{\tfrac {1}{4}}({\sqrt {6}}-{\sqrt {2}})]=\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )} q ( 2 − 1 ) = exp ( − 2 π ) {\displaystyle q({\sqrt {2}}-1)=\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )} Para comprobar la exactitud de estos valores de nome, véase el artículo Nome (matemáticas) .

Sobre la base de estas identidades integrales y la Definición y las identidades de las funciones theta mencionadas anteriormente en la misma sección de este artículo, se determinarán ahora valores cero theta ejemplares:

θ 3 [ exp ( − π ) ] = θ 3 [ q ( 1 2 2 ) ] = 2 π − 1 K ( 1 2 2 ) = 2 − 1 / 2 π − 1 / 2 β ( 1 4 ) 1 / 2 = 2 − 1 / 4 π 4 Γ ( 3 4 ) − 1 {\displaystyle \theta _{3}[\exp(-\pi )]=\theta _{3}[q({\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2}})]={\sqrt {2\pi ^{-1}K({\tfrac {1}{2}}{\sqrt {2}})}}=2^{-1/2}\pi ^{-1/2}\beta ({\tfrac {1}{4}})^{1/2}=2^{-1/4}{\sqrt[{4}]{\pi }}\,{\Gamma {\bigl (}{\tfrac {3}{4}}{\bigr )}}^{-1}} θ 3 [ exp ( − 3 π ) ] = θ 3 { q [ 1 4 ( 6 − 2 ) ] } = 2 π − 1 K [ 1 4 ( 6 − 2 ) ] = 2 − 1 / 6 3 − 1 / 8 π − 1 / 2 β ( 1 3 ) 1 / 2 {\displaystyle \theta _{3}[\exp(-{\sqrt {3}}\,\pi )]=\theta _{3}{\bigl \{}q{\bigl [}{\tfrac {1}{4}}({\sqrt {6}}-{\sqrt {2}}){\bigr ]}{\bigr \}}={\sqrt {2\pi ^{-1}K{\bigl [}{\tfrac {1}{4}}({\sqrt {6}}-{\sqrt {2}}){\bigr ]}}}=2^{-1/6}3^{-1/8}\pi ^{-1/2}\beta ({\tfrac {1}{3}})^{1/2}} θ 3 [ exp ( − 2 π ) ] = θ 3 [ q ( 2 − 1 ) ] = 2 π − 1 K ( 2 − 1 ) = 2 − 1 / 8 cos ( 1 8 π ) π − 1 / 2 β ( 3 8 ) 1 / 2 {\displaystyle \theta _{3}[\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )]=\theta _{3}[q({\sqrt {2}}-1)]={\sqrt {2\pi ^{-1}K({\sqrt {2}}-1)}}=2^{-1/8}\cos({\tfrac {1}{8}}\pi )\,\pi ^{-1/2}\beta ({\tfrac {3}{8}})^{1/2}} θ 4 [ exp ( − 2 π ) ] = θ 4 [ q ( 2 − 1 ) ] = 2 2 − 2 4 2 π − 1 K ( 2 − 1 ) = 2 − 1 / 4 cos ( 1 8 π ) 1 / 2 π − 1 / 2 β ( 3 8 ) 1 / 2 {\displaystyle \theta _{4}[\exp(-{\sqrt {2}}\,\pi )]=\theta _{4}[q({\sqrt {2}}-1)]={\sqrt[{4}]{2{\sqrt {2}}-2}}\,{\sqrt {2\pi ^{-1}K({\sqrt {2}}-1)}}=2^{-1/4}\cos({\tfrac {1}{8}}\pi )^{1/2}\,\pi ^{-1/2}\beta ({\tfrac {3}{8}})^{1/2}}

Secuencias de partición y productos Pochhammer

Secuencia de números de partición regular La secuencia de partición regular en sí misma indica la cantidad de formas en que un número entero positivo se puede dividir en sumandos enteros positivos. Para los números hasta , los números de partición asociados con todas las particiones de números asociadas se enumeran en la siguiente tabla: P ( n ) {\displaystyle P(n)} n {\displaystyle n} n = 1 {\displaystyle n=1} n = 5 {\displaystyle n=5} P {\displaystyle P}

La función generadora de la secuencia de números de partición regular se puede representar mediante el producto Pochhammer de la siguiente manera:

∑ k = 0 ∞ P ( k ) x k = 1 ( x ; x ) ∞ = θ 3 ( x ) − 1 / 6 θ 4 ( x ) − 2 / 3 [ θ 3 ( x ) 4 − θ 4 ( x ) 4 16 x ] − 1 / 24 {\displaystyle \sum _{k=0}^{\infty }P(k)x^{k}={\frac {1}{(x;x)_{\infty }}}=\theta _{3}(x)^{-1/6}\theta _{4}(x)^{-2/3}{\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{4}-\theta _{4}(x)^{4}}{16\,x}}{\biggr ]}^{-1/24}} La sumatoria del producto Pochhammer mencionado anteriormente se describe mediante el teorema del número pentagonal de esta manera:

( x ; x ) ∞ = 1 + ∑ n = 1 ∞ [ − x Fn ( 2 n − 1 ) − x Kr ( 2 n − 1 ) + x Fn ( 2 n ) + x Kr ( 2 n ) ] {\displaystyle (x;x)_{\infty }=1+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\bigl [}-x^{{\text{Fn}}(2n-1)}-x^{{\text{Kr}}(2n-1)}+x^{{\text{Fn}}(2n)}+x^{{\text{Kr}}(2n)}{\bigr ]}} Las siguientes definiciones básicas se aplican a los números pentagonales y a los números de los castillos de naipes:

Fn ( z ) = 1 2 z ( 3 z − 1 ) {\displaystyle {\text{Fn}}(z)={\tfrac {1}{2}}z(3z-1)} Kr ( z ) = 1 2 z ( 3 z + 1 ) {\displaystyle {\text{Kr}}(z)={\tfrac {1}{2}}z(3z+1)} Como aplicación adicional [17] se obtiene una fórmula para la tercera potencia del producto de Euler:

( x ; x ) 3 = ∏ n = 1 ∞ ( 1 − x n ) 3 = ∑ m = 0 ∞ ( − 1 ) m ( 2 m + 1 ) x m ( m + 1 ) / 2 {\displaystyle (x;x)^{3}=\prod _{n=1}^{\infty }(1-x^{n})^{3}=\sum _{m=0}^{\infty }(-1)^{m}(2m+1)x^{m(m+1)/2}}

Secuencia de número de partición estricta Y la secuencia de partición estricta indica el número de formas en que un número entero positivo puede dividirse en sumandos enteros positivos de modo que cada sumando aparezca como máximo una vez [18] y ningún valor de sumando se repita. También se genera exactamente la misma secuencia [19] si en la partición solo se incluyen sumandos impares, pero estos sumandos impares pueden aparecer más de una vez. Ambas representaciones para la secuencia de números de partición estricta se comparan en la siguiente tabla: Q ( n ) {\displaystyle Q(n)} n {\displaystyle n}

La función generadora de la secuencia de números de partición estricta se puede representar utilizando el producto de Pochhammer:

∑ k = 0 ∞ Q ( k ) x k = 1 ( x ; x 2 ) ∞ = θ 3 ( x ) 1 / 6 θ 4 ( x ) − 1 / 3 [ θ 3 ( x ) 4 − θ 4 ( x ) 4 16 x ] 1 / 24 {\displaystyle \sum _{k=0}^{\infty }Q(k)x^{k}={\frac {1}{(x;x^{2})_{\infty }}}=\theta _{3}(x)^{1/6}\theta _{4}(x)^{-1/3}{\biggl [}{\frac {\theta _{3}(x)^{4}-\theta _{4}(x)^{4}}{16\,x}}{\biggr ]}^{1/24}}

Secuencia numérica de sobrepartición La serie de Maclaurin para el recíproco de la función ϑ 01 la secuencia de partición como coeficientes con signo positivo: [20]

1 θ 4 ( x ) = ∏ n = 1 ∞ 1 + x n 1 − x n = ∑ k = 0 ∞ P ¯ ( k ) x k {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\theta _{4}(x)}}=\prod _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {1+x^{n}}{1-x^{n}}}=\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }{\overline {P}}(k)x^{k}} 1 θ 4 ( x ) = 1 + 2 x + 4 x 2 + 8 x 3 + 14 x 4 + 24 x 5 + 40 x 6 + 64 x 7 + 100 x 8 + 154 x 9 + 232 x 10 + … {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\theta _{4}(x)}}=1+2x+4x^{2}+8x^{3}+14x^{4}+24x^{5}+40x^{6}+64x^{7}+100x^{8}+154x^{9}+232x^{10}+\dots } Si, para un número dado , todas las particiones se configuran de tal manera que el tamaño del sumando nunca aumenta, y todos aquellos sumandos que no tienen un sumando del mismo tamaño a la izquierda de ellos mismos se pueden marcar para cada partición de este tipo, entonces será el número resultante [21] de las particiones marcadas dependiendo de la función de sobrepartición . k {\displaystyle k} k {\displaystyle k} P ¯ ( k ) {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(k)}

Primer ejemplo:

P ¯ ( 4 ) = 14 {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(4)=14} Existen estas 14 posibilidades de marcado de partición para la suma 4:

Segundo ejemplo:

P ¯ ( 5 ) = 24 {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(5)=24} Existen estas 24 posibilidades de marcas de partición para la suma 5:

Relaciones de las secuencias de números de partición entre sí En la Enciclopedia en línea de secuencias de números enteros (OEIS), la secuencia de números de partición regular se encuentra bajo el código A000041, la secuencia de particiones estrictas se encuentra bajo el código A000009 y la secuencia de superparticiones se encuentra bajo el código A015128. Todas las particiones principales del índice son pares. P ( n ) {\displaystyle P(n)} Q ( n ) {\displaystyle Q(n)} P ¯ ( n ) {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(n)} n = 1 {\displaystyle n=1}

La secuencia de superparticiones se puede escribir con la secuencia de partición regular P [22] y la secuencia de partición estricta Q [23] se puede generar de la siguiente manera: P ¯ ( n ) {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(n)}

P ¯ ( n ) = ∑ k = 0 n P ( n − k ) Q ( k ) {\displaystyle {\overline {P}}(n)=\sum _{k=0}^{n}P(n-k)Q(k)} En la siguiente tabla de secuencias de números se deberá utilizar como ejemplo esta fórmula:

En relación con esta propiedad, la siguiente combinación de dos series de sumas también se puede configurar mediante la función ϑ 01 :

θ 4 ( x ) = [ ∑ k = 0 ∞ P ( k ) x k ] − 1 [ ∑ k = 0 ∞ Q ( k ) x k ] − 1 {\displaystyle \theta _{4}(x)={\biggl [}\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }P(k)x^{k}{\biggr ]}^{-1}{\biggl [}\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }Q(k)x^{k}{\biggr ]}^{-1}}

Notas ^ Véase, por ejemplo, https://dlmf.nist.gov/20.1. Nótese que, en general, esto no es equivalente a la interpretación habitual cuando está fuera de la franja . Aquí, denota la rama principal del logaritmo complejo . ( e z ) α = e α Log e z {\displaystyle (e^{z})^{\alpha }=e^{\alpha \operatorname {Log} e^{z}}} z {\displaystyle z} − π < Im z ≤ π {\displaystyle -\pi <\operatorname {Im} z\leq \pi } Log {\displaystyle \operatorname {Log} } ^ para todos con . θ 1 ( q ) = 0 {\displaystyle \theta _{1}(q)=0} q ∈ C {\displaystyle q\in \mathbb {C} } | q | < 1 {\displaystyle |q|<1}

Referencias ^ Tyurin, Andrey N. (30 de octubre de 2002). "Cuantización, teoría de campos clásica y cuántica y funciones theta". arXiv : math/0210466v1 . ^ Chang, Der-Chen (2011). Núcleos de calor para operadores elípticos y subelípticos . Birkhäuser. pág. 7. ^ Tata Lectures on Theta I. Clásicos modernos de Birkhäuser. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston. 2007. pág. 4. doi :10.1007/978-0-8176-4577-9. ISBN 978-0-8176-4572-4 ^ Yi, Jinhee (2004). "Identidades de funciones theta y fórmulas explícitas para funciones theta y sus aplicaciones". Revista de análisis matemático y aplicaciones . 292 (2): 381–400. doi : 10.1016/j.jmaa.2003.12.009 . ^ Berndt, Bruce C; Rebák, Örs (9 de enero de 2022). "Valores explícitos para la función theta de Ramanujan ϕ(q)". Revista Hardy-Ramanujan . 44 : 8923. arXiv : 2112.11882 . doi : 10.46298/hrj.2022.8923 . S2CID 245851672. ^ Yi, Jinhee (15 de abril de 2004). "Identidades de funciones theta y fórmulas explícitas para funciones theta y sus aplicaciones". Revista de análisis matemático y aplicaciones . 292 (2): 381–400. doi : 10.1016/j.jmaa.2003.12.009 . ^ Andreas Dieckmann: Tabla de productos infinitos Sumas infinitas Serie infinita, Theta elíptica. Physikalisches Institut Universität Bonn, abril del 1 de octubre de 2021. ^ Landau (1899) zitiert nach Borwein, página 94, ejercicio 3. ^ "Funciones numéricas teóricas, combinatorias y enteras: documentación de mpmath 1.1.0" . Consultado el 18 de julio de 2021 . ^ Mező, István (2013), "Fórmulas de duplicación que involucran funciones theta de Jacobi y funciones trigonométricas q de Gosper ", Actas de la American Mathematical Society , 141 (7): 2401–2410, doi : 10.1090/s0002-9939-2013-11576-5 ^ Mező, István (2012). "Una fórmula q-Raabe y una integral de la cuarta función theta de Jacobi". Revista de teoría de números . 133 (2): 692–704. doi : 10.1016/j.jnt.2012.08.025 . hdl : 2437/166217 . ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Función alfa elíptica". MathWorld . ^ "integración - Integrales curiosas para funciones theta de Jacobi $\int_0^1 \vartheta_n(0,q)dq$". 2022-08-13. ^ Ohyama, Yousuke (1995). "Relaciones diferenciales de funciones theta". Osaka Journal of Mathematics . 32 (2): 431–450. ISSN 0030-6126. ^ Shimura, Sobre formas modulares de peso semiintegral ^ "Valor singular integral elíptico". msu.edu . Consultado el 7 de abril de 2023 . ^ Identidades de funciones theta de Ramanujan que involucran series de Lambert ^ "código golf - Particiones estrictas de un entero positivo" . Consultado el 9 de marzo de 2022 . ^ "A000009 - OEIS". 2022-03-09. ^ Mahlburg, Karl (2004). "La función de sobrepartición módulo pequeñas potencias de 2". Matemáticas discretas . 286 (3): 263–267. doi :10.1016/j.disc.2004.03.014. ^ Kim, Byungchan (28 de abril de 2009). "Elsevier Enhanced Reader". Matemáticas discretas . 309 (8): 2528–2532. doi : 10.1016/j.disc.2008.05.007 . ^ Eric W. Weisstein (11 de marzo de 2022). "Función de partición P". ^ Eric W. Weisstein (11 de marzo de 2022). "Función de partición Q". Abramowitz, Milton ; Stegun, Irene A. (1964). Manual de funciones matemáticas Dover Publications . sec. 16.27ff. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0 Akhiezer, Naum Illyich (1990) [1970]. Elementos de la teoría de funciones elípticas . Traducciones de monografías matemáticas de AMS . Vol. 79. Providence, RI: AMS . ISBN. 978-0-8218-4532-5 Farkas, Hershel M.; Kra, Irwin (1980). Superficies de Riemann . Nueva York: Springer-Verlag . cap. 6. ISBN. 978-0-387-90465-8 (para el tratamiento de la theta de Riemann) Hardy, GH ; Wright, EM (1959). Introducción a la teoría de números (4ª ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press .Mumford, David (1983). Tata Lectures on Theta I. Boston: Birkhauser . ISBN 978-3-7643-3109-2 Pierpont, James (1959). Funciones de una variable compleja . Nueva York: Dover Publications .Rauch, Harry E. ; Farkas, Hershel M. (1974). Funciones theta con aplicaciones a superficies de Riemann . Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins . ISBN 978-0-683-07196-2 Reinhardt, William P.; Walker, Peter L. (2010), "Funciones theta", en Olver, Frank WJ ; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), Manual del NIST de funciones matemáticas 978-0-521-19225-5 Whittaker, ET ; Watson, GN (1927). Un curso de análisis moderno (4.ª ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . cap. 21.(Historia de las funciones θ de Jacobi )

Lectura adicional Farkas, Hershel M. (2008). "Funciones theta en el análisis complejo y la teoría de números". En Alladi, Krishnaswami (ed.). Encuestas sobre teoría de números . Desarrollos en matemáticas. Vol. 17. Springer-Verlag . págs. 57–87. ISBN 978-0-387-78509-7 1206.11055 . Schoeneberg, Bruno (1974). "IX. Serie Theta". Funciones modulares elípticas . Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. vol. 203. Springer-Verlag . págs. 203–226. ISBN 978-3-540-06382-7 Ackerman, Michael (1 de febrero de 1979). "Sobre las funciones generadoras de determinadas series de Eisenstein". Annalen Matemáticas . 244 (1): 75–81. doi :10.1007/BF01420339. S2CID 120045753. Harry Rauch con Hershel M. Farkas: Funciones theta con aplicaciones a superficies de Riemann, Williams y Wilkins, Baltimore MD 1974, ISBN 0-683-07196-3 .

Charles Hermite: Sur la résolution de l'Équation du cinquiéme degré Comptes rendus, CR Acad. Ciencia. París, núm. 11 de marzo de 1858.

Enlaces externos Moiseev Igor. "Funciones elípticas para Matlab y Octave". Este artículo incorpora material de Representaciones integrales de funciones theta de Jacobi en PlanetMath , que se encuentra bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License .