Una rueda hidráulica es una máquina que convierte la energía del agua que fluye o cae en formas útiles de energía, a menudo en un molino de agua . Una rueda hidráulica consiste en una rueda (generalmente construida de madera o metal), con una serie de cuchillas o cubos dispuestos en el borde exterior que forman el carro impulsor. Las ruedas hidráulicas todavía se usaban comercialmente hasta bien entrado el siglo XX, pero ya no son de uso común en la actualidad. Los usos incluían moler harina en molinos , moler madera para hacer pulpa para la fabricación de papel , martillar hierro forjado , mecanizar, triturar minerales y machacar fibra para usar en la fabricación de telas .

Algunas ruedas hidráulicas se alimentan con agua de un estanque de molino, que se forma cuando se represa un arroyo que fluye . Un canal por el que fluye el agua hacia o desde una rueda hidráulica se llama canal de molino . El canal que lleva agua desde el estanque del molino hasta la rueda hidráulica es un canal de entrada ; el que lleva agua después de que ha salido de la rueda se conoce comúnmente como canal de descarga . [1]

Las ruedas hidráulicas se utilizaron para diversos fines, desde la agricultura hasta la metalurgia en civilizaciones antiguas que abarcaron el mundo griego helenístico , Roma , China e India . Las ruedas hidráulicas se siguieron utilizando en la era posclásica , como en la Europa medieval y la Edad de Oro islámica , pero también en otros lugares. A mediados y finales del siglo XVIII, la investigación científica de John Smeaton sobre la rueda hidráulica condujo a aumentos significativos en la eficiencia, suministrando energía muy necesaria para la Revolución Industrial . [2] [3] Las ruedas hidráulicas comenzaron a ser reemplazadas por la turbina más pequeña, menos costosa y más eficiente , desarrollada por Benoît Fourneyron , comenzando con su primer modelo en 1827. [3] Las turbinas son capaces de manejar grandes alturas o elevaciones que exceden la capacidad de las ruedas hidráulicas de tamaño práctico.

La principal dificultad de las ruedas hidráulicas es su dependencia del agua que fluye, lo que limita su ubicación. Las presas hidroeléctricas modernas pueden considerarse descendientes de las ruedas hidráulicas, ya que también aprovechan el movimiento del agua cuesta abajo.

Las ruedas hidráulicas vienen en dos diseños básicos: [4]

Este último se puede subdividir según el lugar donde el agua golpea la rueda en retroceso (inclinación hacia atrás [5] ), retroceso hacia arriba, retroceso hacia abajo, retroceso hacia abajo y ruedas de corriente. [6] [7] [8] El término retroceso hacia abajo puede referirse a cualquier rueda donde el agua pasa por debajo de la rueda [9] pero generalmente implica que la entrada de agua es baja en la rueda.

Las ruedas hidráulicas de tiro superior e inferior se utilizan normalmente cuando la diferencia de altura disponible es superior a un par de metros. Las ruedas de tiro inferior son más adecuadas para caudales grandes con una caída moderada . Las ruedas de tiro inferior y de corriente utilizan caudales grandes con poca o ninguna caída.

A menudo, hay un estanque asociado , un depósito para almacenar agua y, por lo tanto, energía hasta que se necesite. Los cabezales más grandes almacenan más energía potencial gravitatoria para la misma cantidad de agua, por lo que los depósitos para las ruedas de tiro superior e inferior tienden a ser más pequeños que para las ruedas de tiro frontal.

Las ruedas hidráulicas de tiro superior e inferior son adecuadas cuando hay un pequeño arroyo con una diferencia de altura de más de 2 metros (6,5 pies), a menudo asociado a un pequeño embalse. Las ruedas de tiro inferior e inferior se pueden utilizar en ríos o caudales de gran volumen con grandes embalses.

Una rueda horizontal con un eje vertical.

Comúnmente llamada rueda de tina , molino nórdico o molino griego , [10] [11] la rueda horizontal es una forma primitiva e ineficiente de la turbina moderna. Sin embargo, si entrega la potencia requerida, entonces la eficiencia es de importancia secundaria. Generalmente se monta dentro de un edificio de molino debajo del piso de trabajo. Un chorro de agua se dirige a las paletas de la rueda hidráulica, lo que hace que giren. Este es un sistema simple generalmente sin engranajes, de modo que el eje vertical de la rueda hidráulica se convierte en el husillo de accionamiento del molino.

Una rueda de agua [6] [12] es una rueda hidráulica montada verticalmente que gira cuando el agua de un curso de agua golpea paletas o aspas en la parte inferior de la rueda. Este tipo de rueda hidráulica es el tipo más antiguo de rueda de eje horizontal. [ cita requerida ] También se las conoce como ruedas de superficie libre porque el agua no está restringida por canales de molino o fosos de ruedas. [ cita requerida ]

Las ruedas fluviales son más baratas y sencillas de construir y tienen un menor impacto ambiental que otros tipos de ruedas. No constituyen un cambio importante en el río. Sus desventajas son su baja eficiencia, lo que significa que generan menos energía y solo se pueden usar donde el caudal es suficiente. Una rueda típica de tabla plana con descarga inferior utiliza alrededor del 20 por ciento de la energía del flujo de agua que golpea la rueda, según las mediciones del ingeniero civil inglés John Smeaton en el siglo XVIII. [13] Las ruedas más modernas tienen mayor eficiencia.

Las ruedas de los arroyos obtienen poca o ninguna ventaja de la diferencia en el nivel del agua.

Las ruedas de corriente montadas sobre plataformas flotantes se denominan a menudo ruedas de cadera y el molino, molino de barco . A veces se montaban inmediatamente aguas abajo de los puentes, donde la restricción del flujo de los pilares del puente aumentaba la velocidad de la corriente. [ cita requerida ]

Históricamente eran muy ineficientes pero se produjeron avances importantes en el siglo XVIII. [14]

Una rueda de impulsión inferior es una rueda hidráulica montada verticalmente con un eje horizontal que gira cuando el agua golpea la rueda en el cuarto inferior desde un vertedero bajo. La mayor parte de la ganancia de energía proviene del movimiento del agua y comparativamente poca del cabezal. Su funcionamiento y diseño son similares a los de las ruedas de arroyo.

El término prognatismo inferior se utiliza a veces con significados relacionados pero diferentes:

Este es el tipo más antiguo de rueda hidráulica vertical.

La palabra breastshot se utiliza de diversas maneras. Algunos autores limitan el término a las ruedas en las que el agua entra aproximadamente en la posición de las 10 en punto, otros a las 9 en punto y otros a una variedad de alturas. [17] En este artículo se utiliza para las ruedas en las que la entrada de agua está significativamente por encima de la parte inferior y significativamente por debajo de la parte superior, generalmente la mitad central.

Se caracterizan por:

Se utilizan tanto la energía cinética (movimiento) como la potencial (altura y peso).

El pequeño espacio libre entre la rueda y la mampostería requiere que una rueda de pecho tenga una buena rejilla para basura ('screen' en inglés británico) para evitar que los residuos se atasquen entre la rueda y el faldón y potencialmente causen daños graves.

Las ruedas de tiro en pecho son menos eficientes que las ruedas de tiro en contra y en contra, pero pueden manejar altos caudales y, en consecuencia, una gran potencia. Son las preferidas para flujos constantes y de gran volumen, como los que se encuentran en la línea de caída de la costa este de América del Norte. Las ruedas de tiro en pecho son el tipo más común en los Estados Unidos de América [ cita requerida ] y se dice que impulsaron la revolución industrial. [14]

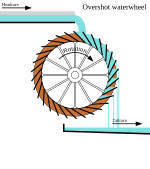

Una rueda hidráulica montada verticalmente que gira gracias al agua que entra en unos cubos justo por encima de la parte superior de la rueda se denomina rueda de empuje. El término a veces se aplica, erróneamente, a las ruedas de empuje trasero, en las que el agua baja por detrás de la rueda.

Una rueda de pescante típica tiene el agua canalizada hacia la rueda en la parte superior y un poco más allá del eje. El agua se acumula en los cubos de ese lado de la rueda, lo que la hace más pesada que el otro lado "vacío". El peso hace girar la rueda y el agua fluye hacia el agua de cola cuando la rueda gira lo suficiente como para invertir los cubos. El diseño de la rueda de pescante es muy eficiente, puede alcanzar el 90% [18] y no requiere un flujo rápido.

Casi toda la energía se obtiene del peso del agua que baja hasta el canal de descarga, aunque una pequeña contribución puede deberse a la energía cinética del agua que entra en la rueda. Son adecuadas para saltos mayores que el otro tipo de rueda, por lo que son ideales para países montañosos. Sin embargo, incluso la rueda hidráulica más grande, la rueda de Laxey en la Isla de Man , solo utiliza un salto de unos 30 m (100 pies). Las turbinas de salto más grandes del mundo, la central hidroeléctrica de Bieudron en Suiza , utilizan unos 1.869 m (6.132 pies).

Las ruedas de arrastre requieren una mayor altura de caída en comparación con otros tipos de ruedas, lo que suele suponer una inversión importante en la construcción del canal de entrada. A veces, la aproximación final del agua a la rueda se realiza a lo largo de un canal o conducto forzado , que puede ser largo.

Una rueda de descarga hacia atrás (también llamada de descarga hacia atrás ) es una variedad de rueda de descarga hacia arriba en la que el agua se introduce justo antes de la cima de la rueda. En muchas situaciones, tiene la ventaja de que la parte inferior de la rueda se mueve en la misma dirección que el agua en el canal de descarga, lo que la hace más eficiente. También funciona mejor que una rueda de descarga hacia arriba en condiciones de inundación cuando el nivel del agua puede sumergir la parte inferior de la rueda. Continuará girando hasta que el agua en el foso de la rueda suba bastante en la rueda. Esto hace que la técnica sea particularmente adecuada para arroyos que experimentan variaciones significativas en el flujo y reduce el tamaño, la complejidad y, por lo tanto, el costo del canal de descarga.

La dirección de rotación de una rueda de tiro hacia atrás es la misma que la de una rueda de tiro hacia atrás, pero en otros aspectos es muy similar a la de una rueda de tiro hacia arriba. Véase a continuación.

Algunas ruedas tienen un resalte superior y un resalte inferior, lo que permite combinar las mejores características de ambos tipos. La fotografía muestra un ejemplo en Finch Foundry en Devon, Reino Unido. El canal de entrada es la estructura de madera superior y un ramal a la izquierda suministra agua a la rueda. El agua sale por debajo de la rueda y vuelve al arroyo.

Un tipo especial de rueda de arrastre es la rueda hidráulica reversible. Esta tiene dos juegos de palas o cangilones que giran en direcciones opuestas, de modo que puede girar en cualquier dirección dependiendo de hacia qué lado se dirija el agua. Las ruedas reversibles se utilizaban en la industria minera para impulsar diversos medios de transporte de mineral. Al cambiar la dirección de la rueda, se podían elevar o bajar barriles o cestas de mineral por un pozo o plano inclinado. Normalmente había un tambor de cable o una cesta de cadena en el eje de la rueda. Es esencial que la rueda tenga un equipo de frenado para poder detener la rueda (conocido como rueda de frenado). El dibujo más antiguo conocido de una rueda hidráulica reversible es de Georgius Agricola y data de 1556.

Como en toda maquinaria, el movimiento rotatorio es más eficiente en los dispositivos de elevación de agua que el movimiento oscilatorio. [19] En términos de fuente de energía, las ruedas hidráulicas pueden ser giradas por la fuerza humana o animal o por la corriente de agua misma. Las ruedas hidráulicas vienen en dos diseños básicos, ya sea equipadas con un eje vertical u horizontal. El último tipo se puede subdividir, dependiendo de dónde golpea el agua las paletas de la rueda, en ruedas de tiro superior, de tiro inferior y de tiro inferior. Las dos funciones principales de las ruedas hidráulicas eran históricamente la elevación de agua para fines de riego y la molienda, particularmente de granos. En el caso de los molinos de eje horizontal, se requiere un sistema de engranajes para la transmisión de energía, que los molinos de eje vertical no necesitan.

La primera rueda hidráulica que funcionaba como una palanca fue descrita por Zhuangzi a finales del período de los Reinos Combatientes (476-221 a. C.). Dice que la rueda hidráulica fue inventada por Zigong, un discípulo de Confucio en el siglo V a. C. [20] Al menos hacia el siglo I d. C., los chinos de la dinastía Han del Este usaban ruedas hidráulicas para triturar el grano en los molinos y para accionar los fuelles de pistón en la forja del mineral de hierro para convertirlo en hierro fundido . [21]

En el texto conocido como Xin Lun escrito por Huan Tan alrededor del año 20 d. C. (durante la usurpación de Wang Mang ), se afirma que el legendario rey mitológico conocido como Fu Xi fue el responsable del mortero, que evolucionó hasta convertirse en el martillo basculante y luego en el martillo de maniobra (véase martillo de maniobra ). Aunque el autor habla del mitológico Fu Xi, un pasaje de su escrito da pistas de que la rueda hidráulica ya se utilizaba ampliamente en el siglo I d. C. en China ( ortografía de Wade-Giles ):

Fu Hsi inventó el mortero, que es tan útil, y más tarde lo mejoró de tal manera que todo el peso del cuerpo podía utilizarse para golpear el martillo basculante ( tui ), aumentando así la eficiencia diez veces. Más tarde, la fuerza de los animales (burros, mulas, bueyes y caballos) se aplicó por medio de maquinaria, y también se utilizó la fuerza del agua para golpear, de modo que el beneficio se multiplicó por cien. [22]

En el año 31 d. C., el ingeniero y prefecto de Nanyang , Du Shi (fallecido en el año 38), aplicó un uso complejo de la rueda hidráulica y la maquinaria para accionar los fuelles del alto horno y crear hierro fundido . Du Shi se menciona brevemente en el Libro de los Han posteriores ( Hou Han Shu ) de la siguiente manera (con ortografía Wade-Giles):

En el séptimo año del reinado de Chien-Wu (31 d. C.) Tu Shih fue designado prefecto de Nanyang. Era un hombre generoso y sus políticas eran pacíficas; destruyó a los malhechores y estableció la dignidad (de su cargo). Era bueno en la planificación, amaba a la gente común y deseaba ahorrar su trabajo. Inventó un reciprocador impulsado por agua ( shui phai ) para la fundición de herramientas agrícolas (de hierro). Aquellos que fundían y fundían ya tenían los fuelles de empuje para avivar sus fuegos de carbón, y ahora se les instruyó para usar el impulso del agua ( chi shui ) para operarlos ... De esta manera, la gente obtuvo grandes beneficios por poco trabajo. Encontraron convenientes los 'fuelles impulsados por agua' y los adoptaron ampliamente. [23]

Las ruedas hidráulicas en China encontraron usos prácticos como este, así como usos extraordinarios. El inventor chino Zhang Heng (78-139) fue el primero en la historia en aplicar la fuerza motriz para rotar el instrumento astronómico de una esfera armilar , mediante el uso de una rueda hidráulica. [24] El ingeniero mecánico Ma Jun (c. 200-265) de Cao Wei utilizó una vez una rueda hidráulica para impulsar y operar un gran teatro mecánico de marionetas para el emperador Ming de Wei ( r. 226-239). [25]

El gran avance tecnológico se produjo en el período helenístico, tecnológicamente desarrollado , entre los siglos III y I a. C. [26] Un poema de Antípatro de Tesalónica elogió la rueda hidráulica por liberar a las mujeres del agotador trabajo de moler y moler. [27] [28]

La rueda hidráulica compartimentada se presenta en dos formas básicas, la rueda con cuerpo compartimentado ( latín tympanum ) y la rueda con borde compartimentado o un borde con recipientes separados y adjuntos. [19] Las ruedas podían ser giradas por hombres que las pisaban por fuera o por animales mediante un engranaje sakia . [29] Si bien el tímpano tenía una gran capacidad de descarga, podía elevar el agua solo a menos de la altura de su propio radio y requería un gran torque para girar. [29] Estas deficiencias constructivas fueron superadas por la rueda con un borde compartimentado que era un diseño menos pesado con una elevación mayor. [30]

La primera referencia literaria a una rueda compartimentada impulsada por agua aparece en el tratado técnico Pneumatica (cap. 61) del ingeniero griego Filón de Bizancio ( c. 280 - c. 220 a. C. ). [31] En su Parasceuastica (91.43−44), Filón aconseja el uso de tales ruedas para sumergir minas de asedio como medida defensiva contra el minado enemigo. [32] Las ruedas compartimentadas parecen haber sido el medio elegido para drenar los diques secos en Alejandría bajo el reinado de Ptolomeo IV (221−205 a. C.). [32] Varios papiros griegos del siglo III al II a. C. mencionan el uso de estas ruedas, pero no dan más detalles. [32] La inexistencia del dispositivo en el Antiguo Cercano Oriente antes de la conquista de Alejandro se puede deducir de su pronunciada ausencia de la, por lo demás, rica iconografía oriental sobre prácticas de irrigación. [33] [ verificación fallida ] [34] [35] [36] Sin embargo, a diferencia de otros dispositivos y bombas de elevación de agua de la época, la invención de la rueda compartimentada no se puede atribuir a ningún ingeniero helenístico en particular y puede haberse realizado a fines del siglo IV a. C. en un contexto rural lejos de la metrópolis de Alejandría. [37]

La representación más antigua de una rueda compartimentada procede de una pintura de una tumba del Egipto ptolemaico que data del siglo II a. C. Muestra un par de bueyes uncidos que impulsan la rueda mediante un engranaje sakia , del que también se tiene constancia por primera vez. [38] El sistema de engranajes sakia griego ya se muestra plenamente desarrollado hasta el punto de que "los dispositivos egipcios modernos son prácticamente idénticos". [38] Se supone que los científicos del Museo de Alejandría , en aquella época el centro de investigación griego más activo, pudieron haber estado involucrados en su invención. [39] Un episodio de la Guerra de Alejandría en el 48 a. C. cuenta cómo los enemigos de César emplearon ruedas hidráulicas con engranajes para verter agua de mar desde lugares elevados sobre la posición de los romanos atrapados. [40]

Alrededor del año 300 d. C., finalmente se introdujo la noria cuando los compartimentos de madera fueron reemplazados por vasijas de cerámica económicas que se ataban al exterior de una rueda de marco abierto. [37]

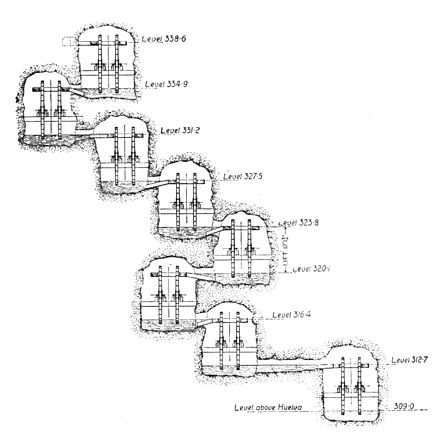

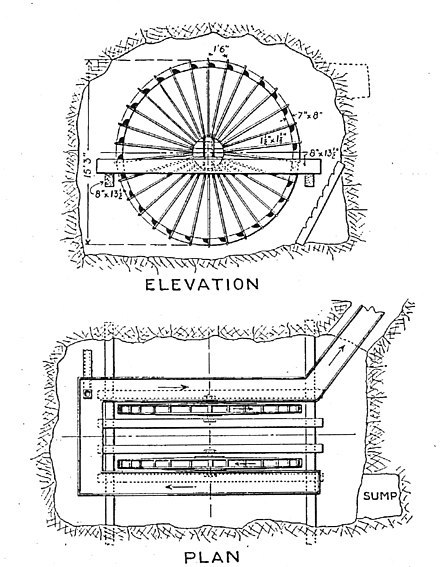

Los romanos utilizaron ampliamente las ruedas hidráulicas en proyectos mineros , y se han encontrado enormes ruedas hidráulicas de la época romana en lugares como la actual España . Eran ruedas hidráulicas de pescante invertido diseñadas para desagotar minas subterráneas profundas. [ cita requerida ] Vitruvio describe varios de estos dispositivos , incluida la rueda hidráulica de pescante invertido y el tornillo de Arquímedes . Muchos se encontraron durante la minería moderna en las minas de cobre de Río Tinto en España , un sistema que involucraba 16 ruedas de este tipo apiladas una sobre otra para elevar el agua a unos 80 pies del sumidero de la mina. Parte de una de estas ruedas se encontró en Dolaucothi , una mina de oro romana en el sur de Gales en la década de 1930, cuando la mina se reabrió brevemente. Se encontró a unos 160 pies debajo de la superficie, por lo que debe haber sido parte de una secuencia similar a la descubierta en Río Tinto. Recientemente se ha datado mediante carbono en torno al año 90 d. C. y, dado que la madera con la que se fabricó es mucho más antigua que la mina profunda, es probable que las explotaciones profundas estuvieran en funcionamiento quizás entre 30 y 50 años después. De estos ejemplos de ruedas de drenaje halladas en galerías subterráneas selladas en lugares muy distantes entre sí se desprende claramente que la construcción de ruedas hidráulicas estaba dentro de sus posibilidades, y que dichas ruedas hidráulicas verticales se utilizaban habitualmente con fines industriales.

Teniendo en cuenta la evidencia indirecta del trabajo del técnico griego Apolonio de Perge , el historiador británico de la tecnología MJT Lewis fecha la aparición del molino de agua de eje vertical a principios del siglo III a. C., y el molino de agua de eje horizontal alrededor del 240 a. C., con Bizancio y Alejandría como los lugares asignados de invención. [41] El geógrafo griego Estrabón ( c. 64 a. C. - c. 24 d. C. ) informa que existió un molino de agua en algún momento antes del 71 a. C. en el palacio del rey póntico Mitrídates VI Eupator , pero su construcción exacta no se puede obtener del texto (XII, 3, 30 C 556). [42]

La primera descripción clara de un molino de agua con engranajes la ofrece el arquitecto romano Vitruvio, de finales del siglo I a. C., quien habla del sistema de engranajes sakia aplicado a un molino de agua. [43] El relato de Vitruvio es particularmente valioso porque muestra cómo surgió el molino de agua, es decir, mediante la combinación de las invenciones griegas separadas del engranaje dentado y la rueda hidráulica en un sistema mecánico eficaz para aprovechar la energía hidráulica. [44] La rueda hidráulica de Vitruvio se describe como sumergida con su extremo inferior en el curso de agua para que sus paletas pudieran ser impulsadas por la velocidad del agua corriente (X, 5.2). [45]

Casi al mismo tiempo, la rueda de arrastre aparece por primera vez en un poema de Antípatro de Tesalónica , que la elogia como un dispositivo que ahorra trabajo (IX, 418.4–6). [46] El motivo también es retomado por Lucrecio (ca. 99–55 a. C.) que compara la rotación de la rueda hidráulica con el movimiento de las estrellas en el firmamento (V 516). [47] El tercer tipo de rueda de eje horizontal, la rueda hidráulica de pecho, aparece en evidencia arqueológica a finales del siglo II d. C. en el contexto de la Galia central . [48] La mayoría de los molinos de agua romanos excavados estaban equipados con una de estas ruedas que, aunque más complejas de construir, eran mucho más eficientes que la rueda hidráulica de eje vertical. [49] En el complejo de molinos de agua de Barbegal del siglo II d. C. , una serie de dieciséis ruedas de arrastre eran alimentadas por un acueducto artificial, una fábrica de granos protoindustrial que ha sido referida como "la mayor concentración conocida de energía mecánica en el mundo antiguo". [50]

En el norte de África romano se encontraron varias instalaciones de alrededor del año 300 d. C. en las que se instalaron ruedas hidráulicas de eje vertical provistas de palas en ángulo en el fondo de un pozo circular lleno de agua. El agua del canal del molino que entraba tangencialmente en el pozo creaba una columna de agua arremolinada que hacía que las ruedas, completamente sumergidas, actuaran como verdaderas turbinas hidráulicas , las más antiguas conocidas hasta la fecha. [51]

Apart from its use in milling and water-raising, ancient engineers applied the paddled waterwheel for automatons and in navigation. Vitruvius (X 9.5–7) describes multi-geared paddle wheels working as a ship odometer, the earliest of its kind. The first mention of paddle wheels as a means of propulsion comes from the 4th–5th century military treatise De Rebus Bellicis (chapter XVII), where the anonymous Roman author describes an ox-driven paddle-wheel warship.[52]

Ancient water-wheel technology continued unabated in the early medieval period where the appearance of new documentary genres such as legal codes, monastic charters, but also hagiography was accompanied with a sharp increase in references to watermills and wheels.[53]

The earliest vertical-wheel in a tide mill is from 6th-century Killoteran near Waterford, Ireland,[54] while the first known horizontal-wheel in such a type of mill is from the Irish Little Island (c. 630).[55] As for the use in a common Norse or Greek mill, the oldest known horizontal-wheels were excavated in the Irish Ballykilleen, dating to c. 636.[55]

The earliest excavated water wheel driven by tidal power was the Nendrum Monastery mill in Northern Ireland which has been dated to 787, although a possible earlier mill dates to 619. Tide mills became common in estuaries with a good tidal range in both Europe and America generally using undershot wheels.

Cistercian monasteries, in particular, made extensive use of water wheels to power watermills of many kinds.[21] An early example of a very large water wheel is the still extant wheel at the early 13th century Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda, a Cistercian monastery in the Aragon region of Spain. Grist mills (for grain) were undoubtedly the most common, but there were also sawmills, fulling mills and mills to fulfil many other labour-intensive tasks. The water wheel remained competitive with the steam engine well into the Industrial Revolution. At around the 8th to 10th century, a number of irrigation technologies were brought into Spain and thus introduced to Europe. One of those technologies is the Noria, which is basically a wheel fitted with buckets on the peripherals for lifting water. It is similar to the undershot water wheel mentioned later in this article. It allowed peasants to power watermills more efficiently. According to Thomas Glick's book, Irrigation and Society in Medieval Valencia, the Noria probably originated from somewhere in Persia. It has been used for centuries before the technology was brought into Spain by Arabs who had adopted it from the Romans. Thus the distribution of the Noria in the Iberian peninsula "conforms to the area of stabilized Islamic settlement".[56] This technology has a profound effect on the life of peasants. The Noria is relatively cheap to build. Thus it allowed peasants to cultivate land more efficiently in Europe. Together with the Spaniards, the technology spread to the New World in Mexico and South America following Spanish expansion

The assembly convened by William of Normandy, commonly referred to as the "Domesday" or Doomsday survey, took an inventory of all potentially taxable property in England, which included over six thousand mills spread across three thousand different locations,[57] up from less than a hundred in the previous century.[21]

The type of water wheel selected was dependent upon the location. Generally if only small volumes of water and high waterfalls were available a millwright would choose to use an overshot wheel. The decision was influenced by the fact that the buckets could catch and use even a small volume of water.[58] For large volumes of water with small waterfalls the undershot wheel would have been used, since it was more adapted to such conditions and cheaper to construct. So long as these water supplies were abundant the question of efficiency remained irrelevant. By the 18th century, with increased demand for power coupled with limited water locales, an emphasis was made on efficiency scheme.[58]

By the 11th century there were parts of Europe where the exploitation of water was commonplace.[57] The water wheel is understood to have actively shaped and forever changed the outlook of Westerners. Europe began to transit from human and animal muscle labor towards mechanical labor with the advent of the water wheel. Medievalist Lynn White Jr. contended that the spread of inanimate power sources was eloquent testimony to the emergence of the West of a new attitude toward, power, work, nature, and above all else technology.[57]

Harnessing water-power enabled gains in agricultural productivity, food surpluses and the large scale urbanization starting in the 11th century. The usefulness of water power motivated European experiments with other power sources, such as wind and tidal mills.[59] Waterwheels influenced the construction of cities, more specifically canals. The techniques that developed during this early period such as stream jamming and the building of canals, put Europe on a hydraulically focused path, for instance water supply and irrigation technology was combined to modify supply power of the wheel.[60] Illustrating the extent to which there was a great degree of technological innovation that met the growing needs of the feudal state.

The water mill was used for grinding grain, producing flour for bread, malt for beer, or coarse meal for porridge.[61] Hammermills used the wheel to operate hammers. One type was fulling mill, which was used for cloth making. The trip hammer was also used for making wrought iron and for working iron into useful shapes, an activity that was otherwise labour-intensive. The water wheel was also used in papermaking, beating material to a pulp. In the 13th century water mills used for hammering throughout Europe improved the productivity of early steel manufacturing. Along with the mastery of gunpowder, waterpower provided European countries worldwide military leadership from the 15th century.

Millwrights distinguished between the two forces, impulse and weight, at work in water wheels long before 18th-century Europe. Fitzherbert, a 16th-century agricultural writer, wrote "druieth the wheel as well as with the weight of the water as with strengthe [impulse]".[62] Leonardo da Vinci also discussed water power, noting "the blow [of the water] is not weight, but excites a power of weight, almost equal to its own power".[63] However, even realisation of the two forces, weight and impulse, confusion remained over the advantages and disadvantages of the two, and there was no clear understanding of the superior efficiency of weight.[64] Prior to 1750 it was unsure as to which force was dominant and was widely understood that both forces were operating with equal inspiration amongst one another.[65] The waterwheel sparked questions of the laws of nature, specifically the laws of force. Evangelista Torricelli's work on water wheels used an analysis of Galileo's work on falling bodies, that the velocity of a water sprouting from an orifice under its head was exactly equivalent to the velocity a drop of water acquired in falling freely from the same height.[66]

The water wheel was a driving force behind the earliest stages of industrialization in Britain. Water-powered reciprocating devices were used in trip hammers and blast furnace bellows. Richard Arkwright's water frame was powered by a water wheel.[67]

The most powerful water wheel built in the United Kingdom was the 100 hp Quarry Bank Mill water wheel near Manchester. A high breastshot design, it was retired in 1904 and replaced with several turbines. It has now been restored and is a museum open to the public.

The biggest working water wheel in mainland Britain has a diameter of 15.4 m (51 ft) and was built by the De Winton company of Caernarfon. It is located within the Dinorwic workshops of the National Slate Museum in Llanberis, North Wales.

The largest working water wheel in the world is the Laxey Wheel (also known as Lady Isabella) in the village of Laxey, Isle of Man. It is 72 feet 6 inches (22.10 m) in diameter and 6 feet (1.83 m) wide and is maintained by Manx National Heritage.

During the Industrial Revolution, in the first half of the 19th century engineers started to design better wheels. In 1823 Jean-Victor Poncelet invented a very efficient undershot wheel design that could work on very low heads, which was commercialized and became popular by late 1830s. Other designs, as the Sagebien wheel, followed later. At the same time Claude Burdin was working on a radically different machine which he called turbine, and his pupil Benoît Fourneyron designed the first commercial one in the 1830s.

Development of water turbines led to decreased popularity of water wheels. The main advantage of turbines is that its ability to harness head is much greater than the diameter of the turbine, whereas a water wheel cannot effectively harness head greater than its diameter. The migration from water wheels to modern turbines took about one hundred years.

Water wheels were used to power sawmills, grist mills and for other purposes during development of the United States. The 40 feet (12 m) diameter water wheel at McCoy, Colorado, built in 1922, is a surviving one out of many which lifted water for irrigation out of the Colorado River.

Two early improvements were suspension wheels and rim gearing. Suspension wheels are constructed in the same manner as a bicycle wheel, the rim being supported under tension from the hub- this led to larger lighter wheels than the former design where the heavy spokes were under compression. Rim-gearing entailed adding a notched wheel to the rim or shroud of the wheel. A stub gear engaged the rim-gear and took the power into the mill using an independent line shaft. This removed the rotative stress from the axle which could thus be lighter, and also allowed more flexibility in the location of the power train. The shaft rotation was geared up from that of the wheel which led to less power loss. An example of this design pioneered by Thomas Hewes and refined by William Armstrong Fairburn can be seen at the 1849 restored wheel at the Portland Basin Canal Warehouse.[68]

Somewhat related were fish wheels used in the American Northwest and Alaska, which lifted salmon out of the flow of rivers.

.jpg/440px-Garfield_water_wheel_(State_Library_of_Victoria_IE1864826).jpg)

Australia has a relatively dry climate, nonetheless, where suitable water resources were available, water wheels were constructed in 19th-century Australia. These were used to power sawmills, flour mills, and stamper batteries used to crush gold-bearing ore. Notable examples of water wheels used in gold recovery operations were the large Garfield water wheel near Chewton—one of at least seven water wheels in the surrounding area—and the two water wheels at Adelong Falls; some remnants exist at both sites.[69][70][71][72] The mining area at Walhalla once had at least two water wheels, one of which was rolled to its site from Port Albert, on its rim using a novel trolley arrangement, taking nearly 90 days.[73] A water wheel at Jindabyne, constructed in 1847, was the first machine used to extract energy—for flour milling—from the Snowy River.[74]

Compact water wheels, known as Dethridge wheels, were used not as sources of power but to measure water flows to irrigated land.[75]

Water wheels were used extensively in New Zealand.[76] The well-preserved remains of the Young Australian mine's overshot water wheel exist near the ghost town of Carricktown,[77] and those of the Phoenix flour mill's water wheel are near Oamaru.[78]

The early history of the watermill in India is obscure. Ancient Indian texts dating back to the 4th century BC refer to the term cakkavattaka (turning wheel), which commentaries explain as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached). On this basis, Joseph Needham suggested that the machine was a noria. Terry S. Reynolds, however, argues that the "term used in Indian texts is ambiguous and does not clearly indicate a water-powered device." Thorkild Schiøler argued that it is "more likely that these passages refer to some type of tread- or hand-operated water-lifting device, instead of a water-powered water-lifting wheel."[79]

According to Greek historical tradition, India received water-mills from the Roman Empire in the early 4th century AD when a certain Metrodoros introduced "water-mills and baths, unknown among them [the Brahmans] till then".[80] Irrigation water for crops was provided by using water raising wheels, some driven by the force of the current in the river from which the water was being raised. This kind of water raising device was used in ancient India, predating, according to Pacey, its use in the later Roman Empire or China,[81] even though the first literary, archaeological and pictorial evidence of the water wheel appeared in the Hellenistic world.[82]

Around 1150, the astronomer Bhaskara Achārya observed water-raising wheels and imagined such a wheel lifting enough water to replenish the stream driving it, effectively, a perpetual motion machine.[83] The construction of water works and aspects of water technology in India is described in Arabic and Persian works. During medieval times, the diffusion of Indian and Persian irrigation technologies gave rise to an advanced irrigation system which bought about economic growth and also helped in the growth of material culture.[84]

After the spread of Islam engineers of the Islamic world continued the water technologies of the ancient Near East; as evident in the excavation of a canal in the Basra region with remains of a water wheel dating from the 7th century. Hama in Syria still preserves some of its large wheels, on the river Orontes, although they are no longer in use.[85] One of the largest had a diameter of about 20 metres (66 ft) and its rim was divided into 120 compartments. Another wheel that is still in operation is found at Murcia in Spain, La Nora, and although the original wheel has been replaced by a steel one, the Moorish system during al-Andalus is otherwise virtually unchanged. Some medieval Islamic compartmented water wheels could lift water as high as 30 metres (100 ft).[86] Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi's Kitab al-Hawi in the 10th century described a noria in Iraq that could lift as much as 153,000 litres per hour (34,000 imp gal/h), or 2,550 litres per minute (560 imp gal/min). This is comparable to the output of modern norias in East Asia, which can lift up to 288,000 litres per hour (63,000 imp gal/h), or 4,800 litres per minute (1,100 imp gal/min).[87]

The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use by the 9th century. A variety of industrial watermills were used in the Islamic world, including gristmills, hullers, sawmills, shipmills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, and tide mills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial watermills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[88] Muslim and Christian engineers also used crankshafts and water turbines, gears in watermills and water-raising machines, and dams as a source of water, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[89] Fulling mills and steel mills may have spread from Islamic Spain to Christian Spain in the 12th century. Industrial water mills were also employed in large factory complexes built in al-Andalus between the 11th and 13th centuries.[90]

The engineers of the Islamic world developed several solutions to achieve the maximum output from a water wheel. One solution was to mount them to piers of bridges to take advantage of the increased flow. Another solution was the shipmill, a type of water mill powered by water wheels mounted on the sides of ships moored in midstream. This technique was employed along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in 10th-century Iraq, where large shipmills made of teak and iron could produce 10 tons of flour from grain every day for the granary in Baghdad.[91] The flywheel mechanism, which is used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine, was invented by Ibn Bassal (fl. 1038–1075) of Al-Andalus; he pioneered the use of the flywheel in the saqiya (chain pump) and noria.[92] The engineers Al-Jazari in the 13th century and Taqi al-Din in the 16th century described many inventive water-raising machines in their technological treatises. They also employed water wheels to power a variety of devices, including various water clocks and automata.

A recent development of the breastshot wheel is a hydraulic wheel which effectively incorporates automatic regulation systems. The Aqualienne is one example. It generates between 37 kW and 200 kW of electricity from a 20 m3 (710 cu ft) waterflow with a head of 1 to 3.5 m (3 to 11 ft).[93] It is designed to produce electricity at the sites of former watermills.

Overshot (and particularly backshot) wheels are the most efficient type; a backshot steel wheel can be more efficient (about 60%) than all but the most advanced and well-constructed turbines. In some situations an overshot wheel is preferable to a turbine.[94]

The development of the hydraulic turbine wheels with their improved efficiency (>67%) opened up an alternative path for the installation of water wheels in existing mills, or redevelopment of abandoned mills.

The energy available to the wheel has two components:

The kinetic energy can be accounted for by converting it into an equivalent head, the velocity head, and adding it to the actual head. For still water the velocity head is zero, and to a good approximation it is negligible for slowly moving water, and can be ignored. The velocity in the tail race is not taken into account because for a perfect wheel the water would leave with zero energy which requires zero velocity. That is impossible, the water has to move away from the wheel, and represents an unavoidable cause of inefficiency.

The power is how fast that energy is delivered which is determined by the flow rate. It has been estimated that the ancient donkey or slave-powered quern of Rome made about one-half of a horsepower, the horizontal waterwheel creating slightly more than one-half of a horsepower, the undershot vertical waterwheel produced about three horsepower, and the medieval overshot waterwheel produced up to forty to sixty horsepower.[95]

dotted notation

The pressure head is the difference in height between the head race and tail race water surfaces. The velocity head is calculated from the velocity of the water in the head race at the same place as the pressure head is measured from. The velocity (speed) can be measured by the pooh sticks method, timing a floating object over a measured distance. The water at the surface moves faster than water nearer to the bottom and sides so a correction factor should be applied as in the formula below.[96]

There are many ways to measure the volume flow rate. Two of the simplest are:

A parallel development is the hydraulic wheel/part reaction turbine that also incorporates a weir into the centre of the wheel but uses blades angled to the water flow. The WICON-Stem Pressure Machine (SPM) exploits this flow.[102] Estimated efficiency 67%.

The University of Southampton School of Civil Engineering and the Environment in the UK has investigated both types of Hydraulic wheel machines and has estimated their hydraulic efficiency and suggested improvements, i.e. The Rotary Hydraulic Pressure Machine. (Estimated maximum efficiency 85%).[103]

These type of water wheels have high efficiency at part loads / variable flows and can operate at very low heads, < 1 m (3 ft 3 in). Combined with direct drive Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Alternators and power electronics they offer a viable alternative for low head hydroelectric power generation.

^ Dotted notation. A dot above the quantity indicates that it is a rate. In other how much each second or how much per second. In this article q is a volume of water and is a volume of water per second. q, as in quantity of water, is used to avoid confusion with v for velocity.

It is no surprise that all the water-lifting devices that depend on subdivided wheels or cylinders originate in the sophisticated, scientifically advanced Hellenistic period, ...

The sudden appearance of literary and archaological evidence for the compartmented wheel in the third century B.C. stand in marked contrast to the complete absence of earlier testimony, suggesting that the device was invented not long before.

References to water-wheels in ancient Mesopotamia, found in handbooks and popular accounts, are for the most part based on the false assumption that the Akkadian equivalent of the logogram GIS.APIN was nartabu and denotes an instrument for watering ("instrument for making moist").

As a result of his investigations, Laessoe writes as follows on the question of the saqiya: "I consider it unlikely that any reference to the saqiya will appear in ancient Mesopotamian sources." In his opinion, we should turn our attention to Alexandria, "where it seems plausible to assume that the saqiya was invented."

This is also the period when water-mills started to spread outside the former Empire. According to Cedrenus (Historiarum compendium), a certain Metrodoros who went to India in c. A.D. 325 "constructed water-mills and baths, unknown among them [the Brahmans] till then".