For the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating a Denial of Traditional Family Values, commonly known as the Russian anti-LGBT law[1][2][3][4] or as the Russian anti-gay law,[5][6][7][8] is a law of Russia. It was unanimously passed by the State Duma on 11 June 2013 (with only one member abstaining—Ilya Ponomarev),[7] unanimously passed by the Federation Council on 27 June 2013,[9] and signed into law by President Vladimir Putin on 30 June 2013.[6]

The stated purpose of the Russian government for the law is to prevent the presentation of the LGBT community as a normal part of Russian society under the argument that LGBT rights in Russia contradict traditional Russian values. The statute amended the Russian law On Protecting Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development and the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses, to prohibit the distribution of "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships" among minors. This definition includes materials that "raise interest in" such relationships, cause minors to "form non-traditional sexual predispositions", or "[present] distorted ideas about the equal social value of traditional and non-traditional sexual relationships." Businesses and organizations can also be forced to temporarily cease operations if convicted under the law, and foreign nationals may be arrested and detained for up to 15 days then deported, or fined up to 5,000 rubles and deported.

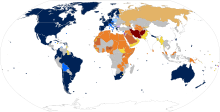

The support of the Russian government for the law appealed to social conservatives, religious conservatives, and Russian nationalists. The law was condemned by the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe (of which Russia was a member of at the time of the enactment of the law), by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and by human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The statute was criticized for its broad and ambiguous wording (including the aforementioned "raises interest in" and "among minors"), which many critics characterized as being an effective ban on publicly promoting LGBT culture and LGBT rights. The law was also criticized for leading to an increase and justification of homophobic violence,[10] while the implications of the laws in relation to the then-upcoming Winter Olympics being hosted by Sochi were also cause for concern, as the Olympic Charter contains language explicitly barring various forms of discrimination.

In December 2022, an amendment to the law was signed into law by Putin, prohibiting the distribution of "propaganda of non-traditional relationships" among any age group. It also prohibits the distribution of materials that promote gender dysphoria among minors.

Despite the fact that the cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg have been well known for their thriving LGBT communities, there has been growing opposition towards gay rights among politicians since 2006.[11] The city of Moscow has actively refused to authorize gay pride parades, and former Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov supported the city's refusal to authorize the first two Moscow Pride events, describing them as "satanic" and blaming western groups for spreading "this kind of enlightenment" in the country.[12][13][14] Social democratic Fair Russia member of parliament Alexander Chuev was also opposed to gay rights and attempted to introduce a similar "propaganda" law in 2007. In response, prominent LGBT rights activist and Moscow Pride founder Nikolay Alexeyev disclosed on the television talk show К барьеру! that Chuev had been publicly involved in same-sex relationships prior to his time in office.[15]

In 2010, Russia was fined by the European Court of Human Rights under allegations by Alexeyev that cities were discriminating against gays by refusing to approve pride parades. Although claiming a risk of violence, the court interpreted the decisions as being in support of groups which oppose such demonstrations.[16] In March 2012, a Russian judge blocked the establishment of a Pride House in Sochi for the 2014 Winter Olympics, ruling that it would "undermine the security of Russian society", and that it contradicted with public morality and policies "in the area of family motherhood and childhood protection."[17] In August 2012, Moscow upheld a ruling blocking Nikolay Alexeyev's requests for 100 years' worth of permission to hold Moscow Pride annually, citing the possibility of public disorder.[18][19]

El proyecto de ley " Sobre la protección de los niños frente a información nociva para su salud y su desarrollo " introdujo leyes que prohibían la distribución de material "nocivo" entre menores. Esto incluye contenido que "puede provocar miedo, horror o pánico en los niños" entre menores, pornografía y materiales que glorifican la violencia, las actividades ilegales, el abuso de sustancias o la autolesión . Una enmienda a la ley aprobada en 2012 instituyó un sistema de clasificación de contenido obligatorio para el material distribuido a través de una "red de información y telecomunicaciones" (que abarca la televisión e Internet ) y estableció una lista negra para censurar sitios web que contengan pornografía infantil o contenido que glorifique el abuso de drogas y suicidio . [20] [21] [22] [23] [24]

La enmienda de 2013, que añadió la "propaganda de relaciones sexuales no tradicionales" como una clase de contenido nocivo según la ley, tenía como objetivo, según el Gobierno de Rusia , proteger a los niños de la exposición a contenidos que retratan la homosexualidad como una "conducta". norma". Se hizo hincapié en el objetivo de proteger los valores familiares "tradicionales" ; La autora del proyecto de ley, Yelena Mizulina (presidenta del Comité de Familia, Mujeres y Niños de la Duma, quien ha sido descrita por algunos como una "cruzada moral"), [8] [25] [26] argumentó que las relaciones "tradicionales" entre una un hombre y una mujer necesitaban protección especial según la legislación rusa. [6] [24] [27] [28] La enmienda también amplió leyes similares promulgadas por varias regiones rusas, incluidas Riazán , Arkhangelsk (que derogó su ley poco después de la aprobación de la versión federal) y San Petersburgo . [29]

Mark Gevisser writes that the Kremlin's backing of the law was reflective of a "dramatic tilt toward homophobia" in Russia that began in the years preceding the law's passage.[30] Gevisser writes that the law's passage allowed the Russian government to find "common ground" with the nationalist far right, and also appeal to the many Russians who view "homosexuality as a sign of encroaching decadence in a globalized era."[30] He writes: "Many Russians feel they can steady themselves against this cultural tsunami by laying claim to 'traditional values,' of which rejection of homosexuality is the easiest shorthand. This message plays particularly well for a government wishing to mobilize against demographic decline (childless homosexuals are evil) and cozy up to the Russian Orthodox Church (homosexuals with children are evil)."[30] Human Rights Watch noted that Putin's enactment of the law allowed him to pander to socially conservative voters at home and "position Russia as a champion of so-called 'traditional values'" on the global stage.[31]

Article 1 of the bill amended On Protecting Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development with a provision classifying "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships" as a class of materials that must not be distributed among minors. The term is defined as materials that are "[aimed] at causing minors to form non-traditional sexual predispositions, notions of attractiveness of non-traditional sexual relationships, distorted ideas about the equal social value of traditional and non-traditional sexual relationships, or imposing information about non-traditional sexual relationships which raises interest in such relationships insofar as these acts do not amount to a criminal offence."

Article 2 makes similar amendments to "On basic guarantees for the rights of the child in the Russian Federation", commanding the government to protect children from such material.[24]

El artículo 3 del proyecto de ley modificó el Código de Infracciones Administrativas de la Federación de Rusia con el artículo 6.21, que prescribe sanciones por violaciones de la prohibición de propaganda: los ciudadanos rusos declarados culpables pueden recibir multas de hasta 5.000 rublos , y los funcionarios públicos pueden recibir multas de hasta 5.000 rublos. hasta 50.000 rublos. Las organizaciones o empresas pueden recibir multas de hasta 1 millón de rublos y verse obligadas a cesar sus operaciones por hasta 90 días. Los extranjeros pueden ser arrestados y detenidos por hasta 15 días y luego deportados, o multados con hasta 5.000 rublos y deportados. Las multas para los particulares son mucho mayores si el delito se cometió a través de los medios de comunicación o Internet. [24]

According to a survey conducted in June 2013 by the state-owned All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion (also known as VTsIOM), at least 90 percent of Russians surveyed were in favour of the law.[11] Over 100 conservative groups worldwide signed a petition in support for the law, with Larry Jacobs, manager of the World Congress of Families, supporting its aim to "prohibit advocacy aimed at involving minors in a lifestyle that would imperil their physical and moral health."[32] President of Russia Vladimir Putin answered to early objections to the then-proposed bill in April 2013 by stating that "I want everyone to understand that in Russia there are no infringements on sexual minorities' rights. They're people, just like everyone else, and they enjoy full rights and freedoms".[33] He went on to say that he fully intended to sign the bill because the Russian people demanded it.[27] As he put it, "Can you imagine an organization promoting pedophilia in Russia? I think people in many Russian regions would have started to take up arms.... The same is true for sexual minorities: I can hardly imagine same-sex marriages being allowed in Chechnya. Can you imagine it? It would have resulted in human casualties."[27] Putin also mentioned that he was concerned about Russia's low birth rate, as same-sex relationships do not produce children.[34] In August 2013, Russian Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko also defended the law, equating it to protecting children from content that glorifies alcohol abuse or drug addiction. He also argued that the controversy over the law and its effects was "invented" by the Western media.[35]

La aprobación de la ley fue recibida con una gran reacción internacional, especialmente del mundo occidental, ya que los críticos la consideraron un intento de prohibir efectivamente la promoción de los derechos y la cultura LGBT en el país. El artículo 19 cuestionó la supuesta intención de la ley y consideró que muchos de los términos utilizados en ella eran demasiado ambiguos, como las "relaciones sexuales no tradicionales" antes mencionadas y "genera interés en". La organización argumentó que "posiblemente podría aplicarse a cualquier información sobre orientación sexual o identidad de género que no encaje con lo que el Estado considera acorde con la 'tradición'". El término "entre menores" también fue criticado por ser ambiguo, ya que no está claro si se refiere a estar en presencia de menores o a cualquier lugar donde los menores puedan estar presentes. Argumentaron que "predecir la presencia de niños en cualquier espacio, en línea o fuera de línea, es bastante imposible y es una variable sobre la que el proponente de cualquier expresión rara vez tendrá un control absoluto". [24]

La ley fue condenada por grupos de derechos humanos como Amnistía Internacional [36] [37] y Human Rights Watch . [38] [31] El Secretario General de la ONU, Ban Ki-moon, criticó indirectamente la ley. [39] Activistas de derechos LGBT , activistas de derechos humanos y otros críticos declararon que la redacción amplia y vaga de la ley, que se caracterizaba como una prohibición de la propaganda gay por parte de los medios de comunicación, tipificaba como delito hacer declaraciones públicas o distribuir materiales en apoyar los derechos LGBT, realizar desfiles del orgullo gay o manifestaciones similares, [40] afirmar que las relaciones homosexuales son iguales a las relaciones heterosexuales o, según el presidente de la Campaña de Derechos Humanos (HRC), Chad Griffin , incluso exhibir símbolos LGBT como la bandera del arco iris o besar a un pareja del mismo sexo en público. [5] [27] [41] [42] El primer arresto realizado bajo la ley involucró a una persona que protestó públicamente con un cartel que contenía un mensaje pro-LGBT. [43]

The legislation reportedly led to an increase in violence against LGBT people in Russia.[44] Russian LGBT Network chairman Igor Kochetkov argued that the law "[has] essentially legalised violence against LGBT people, because these groups of hooligans justify their actions with these laws," supported by their belief that gays and lesbians are "not valued as a social group" by the federal government. Reports surfaced of activity by groups such as 'Occupy Paedophilia' and 'Parents of Russia', who lured alleged "paedophiles" into "dates" where they were tortured and humiliated.[10] In August 2013, it was reported that a gay teenager was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by a group of Russian Neo-Nazis. Violence also increased during pro-gay demonstrations; on 29 July 2013, a gay pride demonstration at Saint Petersburg's Field of Mars resulted in a violent clash between activists, protesters, and police.[45][46][47]

In January 2014, a letter, co-written by chemist Sir Harry Kroto and actor Sir Ian McKellen and co-signed by 27 Nobel laureates from the fields of science and the arts, was sent to Vladimir Putin urging him to repeal the propaganda law as it "inhibits the freedom of local and foreign LGBT communities."[48] In February 2014, the activist group Queer Nation announced a planned protest in New York City outside the Russian consulate on 6 February 2014, timed to coincide with the opening ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics.[49] The same day, gay rights group All Out similarly coordinated worldwide protests in London, New York City, Paris, and Rio de Janeiro.[50] On 8 February 2014, a flash mob was held in Cambridge, England, featuring same-sex couples embracing and hugging, as part of a video project known as "From Russia With Love".[51]

The TV documentary Stephen Fry: Out There explored gay rights and homophobia in numerous countries in the world, including Russia.[52] In it, Stephen Fry interviews a lesbian couple who discuss their fears that simply being out to their 16-year-old daughter and her friends could be taken as breaking this law,[53][54] due to the law's prohibition "on anyone disseminating information about homosexuality to under 18s".[55] The LGBT news magazine The Advocate described the law as criminalising "any positive discussion of LGBT people, identities, or issues in forums that might be accessible to minors. In practice, the law has given police broad license to interpret almost any mention of being LGBT—whether uttered, printed, or signified by waving a rainbow flag—as just cause to arrest LGBT people."[56] The US State Department in its 2013 report on human rights in Russia noted the clarification from Roskomnadzor (the Russian Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies and Mass Communications) that the "gay propaganda" prohibited under the law includes materials which "directly or indirectly approve of people who are in nontraditional sexual relationships."[57] One couple interviewed by Fry said: "Of course we are afraid because we really don't know what's going to happen next in the country. ... You just don't know if they can incarcerate you tomorrow for something or not."[53] Fry also interviewed politician Vitaly Milonov, the original proponent of the law, whose attempts to defend it have been strongly criticized;[52][54] Milonov responded branding Fry as "sick"[58] for making a suicide attempt while filming the documentary[59] in an interview in which he also compared homosexuality with bestiality.[58]

There is a general consensus that the law violates the European Convention of Human Rights, which Russia ratified.[60] In the 2017 case Bayev and Others v. Russia brought by three Russian LGBT activists following their convictions under local anti-propaganda laws, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the laws in question violated the applicants' freedom of speech and right not to be discriminated against in the exercise of Convention rights. The court found that "the authorities reinforce[d] stigma and prejudice and encourage[d] homophobia, which is incompatible with the notions of equality, pluralism and tolerance in a democratic society".[61]

The Council of Europe's advisory body on constitutional law, the Venice Commission, passed a resolution in 2013 stating that bans on "propaganda of homosexuality" "are incompatible with ECHR and international human rights standards" for several reasons. First, these bans were worded too vaguely to satisfy the requirement in Article 10 ECHR that limits on freedom of expression must be "prescribed by law". Second, "homosexuality as a variation of sexual orientation, is protected under the ECHR and as such, cannot be deemed contrary to morals by public authorities, in the sense of Article 10 § 2 of The ECHR". Third, the laws only target "propaganda of homosexuality" but not "propaganda of heterosexuality", which amounts to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation under Article 14 ECHR.[62]

Hate crimes became more prevalent as a direct consequence of the "gay propaganda law". Across the country, numerous individuals, sometimes with implicit support from authorities, engaged in acts of violence against LGBTQ individuals. Some of those individuals organized hate groups that viewed the elimination of LGBTQ individuals as a means of restoring societal order.[63]

The Russian government does not officially record hate crimes against the LGBTQ community, perpetuating a narrative that such individuals do not exist. Instead, authorities make statements such as "We don't have those kinds of people here. We don't have any gays. You cannot kill those who do not exist".[64]

Overall, the number of crimes perpetrated on an annual basis since the enactment of the "gay propaganda" law has been three times higher than prior to the law. This has been reported by a number of research projects and NGOs (two Russian NGOs—LGBT Initiative Group Stimul and SOVA Center and two international organization—OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights – ODIHR).[65][66][67] In addition to this quantitative change, crimes against LGBTQ people have changed qualitatively: since the 2013 law, not only have they have become more violent, more often premeditated and more often committed by a group of perpetrators.[68]

Between 2013 and 2018 there was an increase in the number of hate crimes against LGBTQ people. Such crimes existed before 2013, but the level of violence increased significantly after the introduction of the discriminatory legislation. The increase was recorded in the following year,[69] and it remained on a higher level throughout the decade.[67] It was reported that between 2010 and 2020 there were 1056 hate crimes committed against 853 individuals, with 365 fatalities. The number of crimes after the "gay propaganda" law was enacted is three times higher than before (46 in 2010 compared to 138 in 2015).[67]

These incidents include violent attacks, murders, threats, destruction of property, robberies and others.[67]

After 2013 the crimes against gay people became more violent—research shows that 67% of hate crime incidents have indications of "extreme violence".[67]

Additionally, the crimes became more elaborate, there were more premeditated crimes, committed with preparation (oftentimes by a group of perpetrators with a purposeful selection of a homosexual target)—for three years in a row (2017, 2018, 2019) there was an increase in organized hate crimes against LGBTQ people, attributed to the activity of homophobic hate groups.[67] In most of the cases those hate groups used dating apps and websites in order to "hunt" homosexuals. Those attacks would oftentimes include physical abuse and harassment, the videos of attacks are disseminated on the Internet.[70][71]

One of the most prevalent hate group—Occupy Pedophilia became very active in the aftermath of "the gay propaganda law". Launched by Maxim Martsinkevich, a.k.a. Tesak, at the peak of its activity it was present in 40 regions of Russia.[70] The ideology of this hate group was described in Tesak's book Restruct (2012), where he specifically addresses homosexuality, stating that it "cannot be cured" and therefore needs to be exterminated:

Restrukt [Tesak's follower] is heterosexual. In all his actions, he relies on the laws of nature, therefore he does not allow any tolerance for homosexuals. He hates them, like all other vices. However, this one, unlike some of the others, cannot be cured. There might be former smokers and former alcoholics, but there cannot be former faggots[63]

Between 2010 and 2020 the research identified 205 cases of hate crimes committed by various homophobic hate groups. Moreover, the introduction of the "gay propaganda law" had a noticeable effect on this—the number of cases grew from 2 in 2010 to 38 in 2014. Many of those crimes are committed by Tesak, his followers or copycat movements.[63]

A number of protests were held against the law, both locally and internationally. Activists demonstrated outside New York City's Lincoln Center at the opening night of the Metropolitan Opera on 23 September 2013, which was set to feature Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin. The protests targeted Tchaikovsky's own homosexuality, and the involvement of two Russians in the production; soprano Anna Netrebko and conductor Valery Gergiev, as they were identified as vocal supporters of Putin's government.[72][73]

On 12 October 2013, the day following National Coming Out Day, a protest organized by at least 15 activists was held in Saint Petersburg. The protest site was occupied by a large number of demonstrators, some of whom were dressed as Russian Orthodox priests and Cossacks.[74] In total, 67 protestors were arrested for creating a public disturbance.[75]

Activists also called for a boycott of Stolichnaya vodka, who had prominently branded itself as a Russian vodka (going as far as to dub itself "[the] Mother of All Vodkas from The Motherland of Vodka" in an ad campaign). However, its Luxembourg-based parent company, Soiuzplodoimport, responded to the boycott effort, noting that the company was not technically Russian, did not support the government's opinion on homosexuality, and described itself as a "fervent supporter and friend" of LGBT people.[76]

In 2014, a bill modeled after the Russian anti-gay law was proposed in the parliament of Kyrgyzstan; the measure, which "drew a welter of criticism from multiple rights groups, governments, the United Nations Human Rights Council and the European parliament," would provide for even harsher penalties than the Russian law.[77] The bill passed its first two readings by wide margins (79–7 and then 90–2) but faltered after two of the legislation's lead sponsors failed to win reelection.[77][78] In 2016, the legislation was again raised in parliament, but was held up in subcommittee.[77]

The first arrest made under the propaganda law occurred just hours after it was passed: 24-year-old activist Dmitry Isakov was arrested in Kazan for publicly holding a sign reading "Freedom to the Gays and Lesbians of Russia. Down With Fascists and Homophobes", and ultimately fined 4,000 rubles (US$115). Isakov had performed a similar protest in the same location the previous day as a "test" run, but was later caught in an altercation with police officers who targeted his pro-gay activism, and arrested him for swearing. He would be released without charge, but pledged to return there the next day to show that he would "not be cowed by such pressure." Isakov also claimed that he had been fired from his job at a bank as a result of the conviction.[43][79]

In December 2013, Nikolay Alexeyev and Yaroslav Yevtushenko were fined 4,000 rubles for picketing outside a children's library in Arkhangelsk with banners reading, "Gays aren't made, they're born!" Their appeal was denied.[80]

En enero de 2014, Alexander Suturin, editor en jefe del periódico Molodoi Dalnevostochnik de Khabarovsk , fue multado con 50.000 rublos (1.400 dólares estadounidenses) por publicar una noticia sobre el profesor Alexander Yermoshkin, quien había sido despedido por admitir que portaba "un flash de arco iris". turbas" en Khabarovsk con sus estudiantes, y posteriormente fue atacado por extremistas de derecha debido a su sexualidad. La multa se centró en una cita del artículo del profesor, quien afirmaba que su propia existencia era "una prueba efectiva de que la homosexualidad es normal". [81] [82] [83]

Elena Klimova ha sido acusada varias veces en virtud de la ley de operar Children-404 , un grupo de apoyo en línea para jóvenes LGBT en los servicios de redes sociales VKontakte y Facebook . El primero de estos cargos fue anulado en febrero de 2014, después de que un tribunal dictaminara, en consulta con un profesional de la salud mental, que el grupo "ayuda a los adolescentes a explorar su sexualidad para afrontar cuestiones emocionales difíciles y otros problemas que puedan encontrar", y que estas actividades no constituía "propaganda de relaciones sexuales no tradicionales" según lo define la ley. [84] [85] En enero de 2015, Klimova fue enviada a los tribunales por los mismos cargos. Fueron anuladas en apelación, pero el mismo tribunal condenó a Kilmova y le impuso una multa de 50.000 rublos en julio de 2015, a la espera de una apelación. [86]

En noviembre de 2014, un día después de que el actual director ejecutivo de Apple Inc., Tim Cook, anunciara públicamente que estaba orgulloso de ser gay, [87] se informó que un monumento con forma de iPhone en honor a su difunto cofundador Steve Jobs había sido retirado de un templo santo. Campus universitario de San Petersburgo por su instalador, la Unión Financiera de Europa Occidental (ZEFS). Se alegó que el monumento fue retirado por ley porque estaba en una zona frecuentada por menores. [88] En septiembre de 2015, Apple se convirtió en objeto de una investigación por parte de funcionarios de Kirov por implementar emoji en sus sistemas operativos que representan relaciones entre personas del mismo sexo, sobre si pueden constituir una promoción de relaciones sexuales no tradicionales con menores. [89] Roskomnadzor dictaminó más tarde que, por sí mismos, los emoji que representan parejas del mismo sexo no constituían una violación de la ley de propaganda, ya que si tienen una connotación positiva o negativa depende de su contexto y uso reales. [90]

En marzo de 2018, Roskomnadzor ordenó el bloqueo del destacado sitio web Gay.ru en el país debido a la ley. [91] [92] [93]

El Campeonato Mundial de Atletismo de 2013 , celebrado en el estadio Luzhniki de Moscú en agosto de 2013, se vio ensombrecido por comentarios y protestas por la ley por parte de los atletas. Después de ganar una medalla de plata en el evento, el corredor estadounidense Nick Symmonds afirmó que "ya seas gay, heterosexual, negro o blanco, todos merecemos los mismos derechos. Si hay algo que pueda hacer para defender la causa y promoverla, lo haré". Will, tímido de ser arrestado." [94] Las atletas suecas Emma Green Tregaro y Moa Hjelmer se pintaron las uñas con los colores del arco iris como protesta simbólica. [95] Sin embargo, Tregaro se vio obligado a volver a pintarlos después de que se consideraron un gesto político que violaba las reglas de la IAAF . En respuesta, los volvió a pintar de rojo como símbolo de amor. [96] La saltadora con pértiga rusa Yelena Isinbayeva criticó el gesto de Tregaro por ser irrespetuoso con el país anfitrión, afirmando en una conferencia de prensa que "tenemos nuestra ley que todos deben respetar. Cuando vamos a diferentes países, tratamos de seguir sus reglas. No estamos tratando de establecer nuestras reglas allí. Sólo estamos tratando de ser respetuosos". Después de que los comentarios de Isinbayeva atrajeran críticas generalizadas, ella argumentó que su elección de palabras había sido "malinterpretada" debido a su mal inglés. [97]

The implications of the law on Russia's hosting of two major international sporting events, the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi (where seven LGBT athletes, all female, were expected to compete)[98] and the 2018 FIFA World Cup, were called into question. In the case of the World Cup, FIFA had recently established an anti-discrimination task force, and was also facing criticism for awarding the 2022 World Cup to the country of Qatar, where homosexuality is illegal;[99] in August 2013, FIFA requested information from the Russian government on the law and its potential effects on the association football tournament.[94] In the case of the Winter Olympics, critics considered the law to be inconsistent with the Olympic Charter, which states that "[discrimination] on grounds of race, religion, politics, gender or otherwise is incompatible with belonging to the Olympic Movement."[100] In August 2013, the International Olympic Committee "received assurances from the highest level of government in Russia that the legislation will not affect those attending or taking part in the Games", and also received word that the government would abide by the Olympic Charter.[101][102] The IOC also confirmed that it would enforce Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which forbids political protest, against athletes who make displays of support for the LGBT community at the Games.[103] Vladimir Putin also made similar assurances prior to the Games, but warned LGBT attendees that they would still be subject to the law.[104]

Athletes and supporters used the Olympics as leverage for further campaigns against the propaganda law. A number of athletes came out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual to spread awareness of the situation in Russia, including Australian snowboarder Belle Brockhoff,[105] Canadian speed skater Anastasia Bucsis,[106] gold medal figure skater Brian Boitano,[107] and Finnish swimmer Ari-Pekka Liukkonen.[108] There were also calls to boycott the Games, drawing comparisons to the Summer Olympics of 1980 in Moscow, the last time the Olympics were held on what is now Russian soil.[5] A campaign known as Principle 6 was established in collaboration between a group of Olympic athletes, the organizations All Out and Athlete Ally, and clothing maker American Apparel, selling merchandise (such as clothing) with a quotation from the Olympic Charter to support pro-LGBT organizations.[109] Toronto advertising copywriter Brahm Finkelstein also began to market a rainbow-coloured matryoshka doll set known as "Pride Dolls", designed by Italian artist Danilo Santino, to benefit the Gay and Lesbian International Sport Association, organizers of the World Outgames.[110][111]

Action was leveraged directly against Olympic sponsors and partners as well; in late-August 2013, the Human Rights Campaign sent letters to the ten Worldwide Olympic Partner companies, urging them to show opposition towards anti-LGBT laws, denounce homophobic violence, ask the IOC to obtain written commitments for the safety of LGBT athletes and attendees, and oppose future Olympic bids from countries that outlaw support for LGBT equality.[112] In February 2014, prior to the games, a group of 40 human rights organizations (including Athlete Ally, Freedom House, Human Rights Campaign, Human Rights Watch and Russian LGBT Network among others) also sent a joint letter to the Worldwide Olympic Partners, urging them to use their prominence to support the rights of LGBT athletes under the Olympic Charter, and pressure the IOC to show greater scrutiny towards the human rights abuses of future host countries.[113][114] On 3 February 2014, USOC sponsor AT&T issued a statement in support of LGBT rights at the Games, becoming the first major Olympic advertiser to condemn the laws.[115] Several major non-sponsors also made pro-LGBT statements to coincide with the opening of the Games; Google placed a quotation from the Olympic Charter and an Olympic-themed logo in the colours of the rainbow flag on its home page worldwide,[116] while Channel 4 (who serves as the official British broadcaster of the Paralympics) adopted a rainbow-coloured logo and broadcast a "celebratory", pro-LGBT advert entitled "Gay Mountain" on 7 February 2014, alongside an interview with former rugby union player and anti-homophobia activist Ben Cohen. As part of its Dispatches series, Channel 4 had also broadcast a documentary during the week of the Opening Ceremony entitled Hunted, which documented the violence and abuse against LGBT people in Russia in the wake of the law.[10][117][118]

In May 2014, it was revealed that in accordance with the propaganda law, the computer game The Sims 4—a new installment in a life simulation game franchise published by Electronic Arts which has historically allowed characters to participate in same-sex relationships, and allowed players to give their characters a customised gender, had been given an "18+" rating, restricting its sale to adults only. In contrast, the pan-European ratings board PEGI has historically rated The Sims games as being suitable for those aged 12 and over.[119][120][121]

In December 2016, the video game FIFA 17 (which is also published by Electronic Arts) was targeted for an event that allowed users to obtain rainbow-coloured shoelaces for their virtual footballers, in support of a pro-LGBT advocacy campaign backed by the English Premier League. MP Irina Rodnina stated that relevant authorities needed to "verify the possibility of distributing this game on the territory of the Russian Federation".[122]

In December 2016, Blizzard Entertainment geo-blocked a tie-in web comic for its game Overwatch in Russia for containing a scene of the character Tracer, who was confirmed as being lesbian, kissing her partner, another woman. Blizzard cited the gay propaganda law as reasoning for the block. The game itself is not blocked in the country.[123][124]

In February 2021, Miitopia received an 18+ rating due to the ability of same-sex Miis being able to form "relationships" with each other despite no actual sexual content whatsoever being present in the game.[125]

In July 2022, Communist politician Nina Ostanina co-sponsored a bill that would ban "the denial of family values" and the promotion of "non-traditional sexual orientations." In an interview, she further stated that "a traditional family is a union of a man and woman, it’s children, it’s a multi-generational family."[126][127][128]

In September 2022, at a political ceremony in which Russia formally annexed regions of Ukraine, Putin said: "Do we really want to have here, in our country, in Russia, 'Parent No. 1, No. 2, No. 3' instead of 'mom' and 'dad?' Do we really want perversions that lead to degradation and extinction to be imposed in our schools from the primary grades?"[129]

On 27 October 2022, the State Duma unanimously passed a proposed bill that expands the gay propaganda law to cover any age group, instead of only minors. The bill also adds materials that give minors a "desire to change their sex", or constitute the promotion of "paedophilia", to the categories of materials covered by the law.[130][131][132] The bill was unanimously passed by the Federation Council on 2 December 2022 and signed into law by Putin on 5 December 2022.[133]

Deputy Secretary of the General Council of Putin's United Russia, Alexander Khinshtein, is one of the architects of anti-LGBT legislation that widens a prohibition of "LGBT propaganda" and restricts the "demonstration" of LGBT behaviour, saying, "LGBT today is an element of hybrid warfare and in this hybrid warfare we must protect our values, our society and our children."[134]

Supporters of the bill consider it as a response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, seeking to protect the country from influence and indoctrination by liberal Western values. Konstantin Malofeev argued that "our enemy holds the propaganda of sodomy as the core of its influence". The bill has faced criticism from LGBT rights groups and other parties, who consider it to be a blanket ban on any pro-LGBT activity, and warned that it could result in the ban or censorship of advertising, films, and literature that include LGBT themes. It was also criticised for falsely conflating homosexuality with pedophilia.[130][131][132]

Narrator (Stephen Fry): The man behind the new law is the Deputy of St. Petersburg, Vitaly Milanov. He believes that he can prevent a new generation of Russians from becoming gay be banning so-called gay propaganda. It's created an impossible situation for gay parents here who could now be accused of promoting their homosexuality to their own children. ... Olga, a local activist, has arranged for me to meet some of those living with the fallout from the law. ... Irina and Olga have been together for 12 years, and each have one child from previous relationships: 20-year old Daniel, and Christina, who at 16 is still considered a minor.

STEPHEN FRY: According to this new law, every day you are breaking the law by promoting homosexuality to Christina. (Olga and Irina nodding)

OLGA (in Russian): Yes, not only Christina but her friends too! According to Mr Milinov gay families are perverts and their children are even worse. It's very insulting and hard for the kids, especially Christina. All of that was very unpleasant for her to hear.

STEPHEN FRY: Does it actually seriously worry you that the day may come when you as a family are threatened by this new law?

IRINA (in Russian): Of course we are afraid because we really don't know what's going to happen next in the country. There is even aggression in the streets and it is getting worse.

OLGA (in Russian): We are living in a very difficult period of time historically.

IRINA (in Russian):You just don't know if they can incarcerate you tomorrow for something or not.

President Putin signed a law that criminalizes the so-called propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations to minors. The law effectively limits the rights of free expression and assembly for citizens who wish to publicly advocate for LGBT rights or express the opinion that homosexuality is normal (see sections 2.a. and 2.b.). On December 2, Roskomnadzor issued a list of clarifying criteria and examples of so-called LGBT propaganda, which includes materials that "directly or indirectly approve of people who are in nontraditional sexual relationships." LGBT persons reported dramatically heightened societal stigma and discrimination, which some attributed to increasing official promotion of intolerance and homophobia. Gay rights activists asserted that the majority of LGBT persons hid their orientation due to fear of losing their jobs or their homes as well as the threat of violence