Una refinería de petróleo o refinería de petróleo es una planta de proceso industrial donde el petróleo (petróleo crudo) se transforma y refina en productos como gasolina (gasolina), combustible diésel , base de asfalto , fueloil , aceite de calefacción , queroseno , gas licuado de petróleo y nafta de petróleo . [1] [2] [3] Las materias primas petroquímicas como el etileno y el propileno también se pueden producir directamente mediante el craqueo del petróleo crudo sin la necesidad de utilizar productos refinados del petróleo crudo como la nafta. [4] [5] La materia prima de petróleo crudo generalmente ha sido procesada por una planta de producción de petróleo . [1] Por lo general, hay un depósito de petróleo en o cerca de una refinería de petróleo para el almacenamiento de la materia prima de petróleo crudo entrante, así como de productos líquidos a granel. En 2020, la capacidad total de las refinerías mundiales de petróleo crudo fue de aproximadamente 101,2 millones de barriles por día. [6]

Las refinerías de petróleo suelen ser complejos industriales grandes y extensos con extensas tuberías que recorren todo su recorrido y transportan corrientes de fluidos entre grandes unidades de procesamiento químico , como columnas de destilación . En muchos sentidos, las refinerías de petróleo utilizan muchas tecnologías diferentes y pueden considerarse como tipos de plantas químicas . Desde diciembre de 2008, la refinería de petróleo más grande del mundo ha sido la Refinería de Jamnagar , propiedad de Reliance Industries , ubicada en Gujarat , India, con una capacidad de procesamiento de 1,24 millones de barriles (197.000 m 3 ) por día.

Las refinerías de petróleo son una parte esencial del sector downstream de la industria petrolera . [7]

Los chinos fueron una de las primeras civilizaciones en refinar petróleo. [8] Ya en el siglo I, los chinos refinaban petróleo crudo para usarlo como fuente de energía. [9] [8] Entre 512 y 518, a fines de la dinastía Wei del Norte , el geógrafo, escritor y político chino Li Daoyuan introdujo el proceso de refinación de petróleo en varios lubricantes en su famosa obra Comentario sobre el Clásico del Agua . [10] [9] [8]

Los químicos persas solían destilar petróleo crudo , con descripciones claras en manuales como los de Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi ( c. 865-925 ). [11] Las calles de Bagdad estaban pavimentadas con alquitrán , derivado del petróleo al que se podía acceder desde los campos naturales de la región. En el siglo IX, se explotaron yacimientos petrolíferos en el área alrededor de la actual Bakú , Azerbaiyán. Estos yacimientos fueron descritos por el geógrafo árabe Abu al-Hasan 'Alī al-Mas'ūdī en el siglo X, y por Marco Polo en el siglo XIII, quien describió la producción de esos pozos como cientos de barcos cargados. [12] Los químicos árabes y persas también destilaban petróleo crudo para producir productos inflamables para fines militares. A través de la España islámica , la destilación estuvo disponible en Europa occidental en el siglo XII. [13]

En la dinastía Song del Norte (960-1127), se estableció en la ciudad de Kaifeng un taller llamado "Taller de aceite feroz", para producir aceite refinado para el ejército Song como arma. Las tropas llenaban entonces latas de hierro con aceite refinado y las arrojaban hacia las tropas enemigas, provocando un incendio, en efecto, la primera " bomba incendiaria " del mundo. El taller fue una de las primeras fábricas de refinación de petróleo del mundo, donde miles de personas trabajaban para producir armamento chino propulsado por petróleo. [14]

Antes del siglo XIX, el petróleo era conocido y utilizado de diversas formas en Babilonia , Egipto , China , Filipinas , Roma y Azerbaiyán . Sin embargo, se dice que la historia moderna de la industria petrolera comenzó en 1846, cuando Abraham Gessner, de Nueva Escocia (Canadá) , ideó un proceso para producir queroseno a partir de carbón. Poco después, en 1854, Ignacy Łukasiewicz comenzó a producir queroseno a partir de pozos de petróleo excavados a mano cerca de la ciudad de Krosno ( Polonia) .

Rumania fue registrado como el primer país en las estadísticas de producción mundial de petróleo, según la Academia de Récords Mundiales. [15] [16]

En América del Norte, el primer pozo de petróleo fue perforado en 1858 por James Miller Williams en Oil Springs, Ontario , Canadá. [17] En los Estados Unidos, la industria petrolera comenzó en 1859 cuando Edwin Drake encontró petróleo cerca de Titusville , Pensilvania . [18] La industria creció lentamente en el siglo XIX, principalmente produciendo queroseno para lámparas de aceite. A principios del siglo XX, la introducción del motor de combustión interna y su uso en automóviles creó un mercado para la gasolina que fue el impulso para el crecimiento bastante rápido de la industria petrolera. Los primeros hallazgos de petróleo como los de Ontario y Pensilvania pronto fueron superados por grandes "booms" petroleros en Oklahoma , Texas y California . [19]

Samuel Kier estableció la primera refinería de petróleo de Estados Unidos en Pittsburgh, en la Séptima Avenida, cerca de Grant Street, en 1853. [20] El farmacéutico e inventor polaco Ignacy Łukasiewicz estableció una refinería de petróleo en Jasło , entonces parte del Imperio austrohúngaro (ahora en Polonia ) en 1854.

La primera gran refinería se inauguró en Ploiesti, Rumania, en 1856-1857. [15] Fue en Ploiesti donde, 51 años después, en 1908, Lazăr Edeleanu , un químico rumano de origen judío que obtuvo su doctorado en 1887 al descubrir la anfetamina , inventó, patentó y probó a escala industrial el primer método moderno de extracción líquida para refinar petróleo crudo, el proceso Edeleanu . Esto aumentó la eficiencia de refinación en comparación con la destilación fraccionada pura y permitió un desarrollo masivo de las plantas de refinación. Sucesivamente, el proceso se implementó en Francia, Alemania, EE. UU. y en pocas décadas se extendió por todo el mundo. En 1910 Edeleanu fundó en Alemania la Allgemeine Gesellschaft für Chemische Industrie, que, dado el éxito del nombre, cambió a Edeleanu GmbH en 1930. Durante la época nazi, la empresa fue comprada por la Deutsche Erdöl-AG y Edeleanu, de origen judío, se trasladó de nuevo a Rumanía. Después de la guerra, la marca registrada fue utilizada por la empresa sucesora EDELEANU Gesellschaft mbH Alzenau (RWE) para muchos productos petrolíferos, mientras que la empresa se integró más tarde como EDL en el Grupo Pörner . Las refinerías de Ploiești, tras ser tomadas por la Alemania nazi , fueron bombardeadas en la Operación Tidal Wave de 1943 por los Aliados , durante la Campaña del Petróleo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial .

Otra ciudad que se disputa el título de albergar la refinería de petróleo más antigua del mundo es Salzbergen, en la Baja Sajonia , Alemania. La refinería de Salzbergen se inauguró en 1860.

En un momento dado, se afirmó que la refinería de Ras Tanura , Arabia Saudita, propiedad de Saudi Aramco, era la refinería de petróleo más grande del mundo. Durante la mayor parte del siglo XX, la refinería más grande fue la Refinería de Abadan en Irán . Esta refinería sufrió grandes daños durante la Guerra Irán-Irak . Desde el 25 de diciembre de 2008, el complejo de refinería más grande del mundo es el Complejo de Refinería de Jamnagar , que consta de dos refinerías una al lado de la otra operadas por Reliance Industries Limited en Jamnagar, India, con una capacidad de producción combinada de 1.240.000 barriles por día (197.000 m 3 /d). El Complejo Refinador Paraguaná de PDVSA en la Península de Paraguaná , Venezuela , con una capacidad de 940.000 bbl/d (149.000 m 3 /d) y Ulsan de SK Energy en Corea del Sur con 840.000 bbl/d (134.000 m 3 /d) son el segundo y tercer más grande, respectivamente.

Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, a principios de la década de 1940, la mayoría de las refinerías de petróleo en los Estados Unidos consistían simplemente en unidades de destilación de petróleo crudo (a menudo denominadas unidades de destilación atmosférica de petróleo crudo). Algunas refinerías también tenían unidades de destilación al vacío , así como unidades de craqueo térmico , como los viscorreductores (disminuyentes de viscosidad, unidades para reducir la viscosidad del petróleo). Todos los demás procesos de refinación que se analizan a continuación se desarrollaron durante la guerra o unos pocos años después de la misma. Se volvieron comercialmente disponibles entre 5 y 10 años después de que terminara la guerra y la industria petrolera mundial experimentó un crecimiento muy rápido. La fuerza impulsora de ese crecimiento en la tecnología y en el número y tamaño de las refinerías en todo el mundo fue la creciente demanda de gasolina para automóviles y combustible para aviones.

En los Estados Unidos, por diversas razones económicas y políticas complejas, la construcción de nuevas refinerías prácticamente se detuvo alrededor de la década de 1980. Sin embargo, muchas de las refinerías existentes en los Estados Unidos han modernizado muchas de sus unidades y/o construido unidades adicionales con el fin de: aumentar su capacidad de procesamiento de petróleo crudo, aumentar el índice de octano de su gasolina producto, reducir el contenido de azufre de su combustible diésel y combustibles para calefacción doméstica para cumplir con las regulaciones ambientales y cumplir con los requisitos ambientales de contaminación del aire y del agua.

En el siglo XIX, las refinerías de Estados Unidos procesaban el petróleo crudo principalmente para recuperar el queroseno . No había mercado para la fracción más volátil, incluida la gasolina, que se consideraba un desecho y a menudo se vertía directamente en el río más cercano. La invención del automóvil desplazó la demanda hacia la gasolina y el diésel, que siguen siendo los principales productos refinados en la actualidad. [22]

En la actualidad, la legislación nacional y estatal exige que las refinerías cumplan con estrictos estándares de limpieza del aire y del agua. De hecho, las compañías petroleras en los EE. UU. perciben que obtener un permiso para construir una refinería moderna es tan difícil y costoso que no se construyeron nuevas refinerías (aunque muchas se han ampliado) en los EE. UU. desde 1976 hasta 2014, cuando comenzó a operar la pequeña refinería Dakota Prairie en Dakota del Norte. [23] Más de la mitad de las refinerías que existían en 1981 ahora están cerradas debido a las bajas tasas de utilización y la aceleración de las fusiones. [24] Como resultado de estos cierres, la capacidad total de las refinerías de los EE. UU. cayó entre 1981 y 1995, aunque la capacidad operativa se mantuvo bastante constante en ese período de tiempo en alrededor de 15.000.000 de barriles por día (2.400.000 m 3 /d). [25] El aumento en el tamaño de las instalaciones y las mejoras en la eficiencia han compensado gran parte de la capacidad física perdida de la industria. En 1982 (los primeros datos disponibles), Estados Unidos operaba 301 refinerías con una capacidad combinada de 17,9 millones de barriles (2.850.000 m 3 ) de petróleo crudo cada día calendario. En 2010, había 149 refinerías operables en Estados Unidos con una capacidad combinada de 17,6 millones de barriles (2.800.000 m 3 ) por día calendario. [26] Para 2014, el número de refinerías se había reducido a 140, pero la capacidad total aumentó a 18,02 millones de barriles (2.865.000 m 3 ) por día calendario. De hecho, para reducir los costos operativos y la depreciación, la refinación se opera en menos sitios pero de mayor capacidad.

Entre 2009 y 2010, cuando los flujos de ingresos en el negocio petrolero se agotaron y la rentabilidad de las refinerías de petróleo cayó debido a la menor demanda del producto y las altas reservas de suministro anteriores a la recesión económica , las compañías petroleras comenzaron a cerrar o vender las refinerías menos rentables. [27]

El petróleo crudo crudo o sin procesar no suele ser útil en aplicaciones industriales, aunque el petróleo crudo "ligero y dulce" (de baja viscosidad y bajo contenido de azufre ) se ha utilizado directamente como combustible de quemador para producir vapor para la propulsión de buques marítimos. Sin embargo, los elementos más ligeros forman vapores explosivos en los tanques de combustible y, por lo tanto, son peligrosos, especialmente en los buques de guerra . En cambio, los cientos de moléculas de hidrocarburos diferentes del petróleo crudo se separan en una refinería en componentes que se pueden utilizar como combustibles , lubricantes y materias primas en procesos petroquímicos que fabrican productos como plásticos , detergentes , disolventes , elastómeros y fibras como el nailon y los poliésteres .

Los combustibles fósiles derivados del petróleo se queman en motores de combustión interna para proporcionar energía a barcos , automóviles , motores de aeronaves , cortadoras de césped , motos de cross y otras máquinas. Los diferentes puntos de ebullición permiten separar los hidrocarburos mediante destilación . Dado que los productos líquidos más ligeros tienen una gran demanda para su uso en motores de combustión interna, una refinería moderna convertirá los hidrocarburos pesados y los elementos gaseosos más ligeros en estos productos de mayor valor. [28]

El petróleo se puede utilizar de diversas maneras porque contiene hidrocarburos de diferentes masas moleculares , formas y longitudes, como parafinas , aromáticos , naftenos (o cicloalcanos ), alquenos , dienos y alquinos . [29] Si bien las moléculas del petróleo crudo incluyen diferentes átomos, como azufre y nitrógeno, los hidrocarburos son la forma más común de moléculas, que son moléculas de diferentes longitudes y complejidad hechas de átomos de hidrógeno y carbono , y una pequeña cantidad de átomos de oxígeno. Las diferencias en la estructura de estas moléculas explican sus diferentes propiedades físicas y químicas , y es esta variedad la que hace que el petróleo crudo sea útil en una amplia gama de varias aplicaciones.

Una vez separado y purificado de cualquier contaminante e impureza, el combustible o lubricante puede venderse sin procesamiento adicional. Las moléculas más pequeñas, como el isobutano y el propileno o los butilenos, pueden recombinarse para cumplir con los requisitos específicos de octano mediante procesos como la alquilación o, más comúnmente, la dimerización . El grado de octano de la gasolina también puede mejorarse mediante reformado catalítico , que implica eliminar el hidrógeno de los hidrocarburos produciendo compuestos con índices de octano más altos, como los aromáticos . Los productos intermedios, como los gasóleos, incluso pueden reprocesarse para romper un aceite pesado de cadena larga en uno más ligero de cadena corta, mediante varias formas de craqueo, como el craqueo catalítico de fluidos , el craqueo térmico y el hidrocraqueo . El paso final en la producción de gasolina es la mezcla de combustibles con diferentes índices de octano, presiones de vapor y otras propiedades para cumplir con las especificaciones del producto. Otro método para reprocesar y mejorar estos productos intermedios (aceites residuales) utiliza un proceso de desvolatilización para separar el aceite utilizable del material de asfalteno de desecho.

Las refinerías de petróleo son plantas de gran escala que procesan entre cien mil y varios cientos de miles de barriles de petróleo crudo por día. Debido a su gran capacidad, muchas de las unidades funcionan de manera continua , en lugar de procesar en lotes , en un estado estable o casi estable durante meses o años. La gran capacidad también hace que la optimización de procesos y el control avanzado de procesos sean muy deseables.

Los productos derivados del petróleo son materiales derivados del petróleo crudo ( petróleo ) a medida que se procesa en las refinerías de petróleo . La mayor parte del petróleo se convierte en productos derivados del petróleo, que incluyen varias clases de combustibles. [31]

Las refinerías de petróleo también producen diversos productos intermedios, como hidrógeno , hidrocarburos ligeros, reformados y gasolina de pirólisis . Por lo general, estos no se transportan, sino que se mezclan o procesan en el lugar. Por lo tanto, las plantas químicas suelen estar adyacentes a las refinerías de petróleo o se integran en ellas una serie de procesos químicos adicionales. Por ejemplo, los hidrocarburos ligeros se craquean a vapor en una planta de etileno y el etileno producido se polimeriza para producir polietileno .

Para garantizar una separación adecuada y la protección del medio ambiente, es necesario un contenido muy bajo de azufre en todos los productos, excepto en los más pesados. El contaminante de azufre crudo se transforma en sulfuro de hidrógeno mediante hidrodesulfuración catalítica y se elimina de la corriente de producto mediante un tratamiento con gas de amina . Mediante el proceso Claus , el sulfuro de hidrógeno se transforma posteriormente en azufre elemental para venderlo a la industria química. La gran cantidad de energía térmica liberada por este proceso se utiliza directamente en las otras partes de la refinería. A menudo, se combina una planta de energía eléctrica en todo el proceso de refinería para absorber el exceso de calor.

Según la composición del petróleo crudo y dependiendo de las demandas del mercado, las refinerías pueden producir diferentes porciones de productos derivados del petróleo. La mayor parte de los productos derivados del petróleo se utiliza como "portadores de energía", es decir, varios grados de fueloil y gasolina . Estos combustibles incluyen o pueden mezclarse para dar gasolina, combustible para aviones , combustible diésel , fueloil para calefacción y fueloils más pesados. Las fracciones más pesadas (menos volátiles ) también se pueden utilizar para producir asfalto , alquitrán , cera de parafina , lubricantes y otros aceites pesados. Las refinerías también producen otros productos químicos , algunos de los cuales se utilizan en procesos químicos para producir plásticos y otros materiales útiles. Dado que el petróleo a menudo contiene un pequeño porcentaje de moléculas que contienen azufre , el azufre elemental también se produce a menudo como un producto derivado del petróleo. El carbono , en forma de coque de petróleo , y el hidrógeno también se pueden producir como productos derivados del petróleo. El hidrógeno producido se utiliza a menudo como un producto intermedio para otros procesos de refinería de petróleo, como el hidrocraqueo y la hidrodesulfuración . [32]

Los productos derivados del petróleo suelen agruparse en cuatro categorías: destilados ligeros (GLP, gasolina, nafta), destilados medios (queroseno, combustible para aviones, diésel), destilados pesados y residuos (fueloil pesado, aceites lubricantes, cera, asfalto). Estos requieren la mezcla de diversas materias primas, la mezcla de aditivos adecuados, el almacenamiento a corto plazo y la preparación para la carga a granel en camiones, barcazas, barcos de productos y vagones de ferrocarril. Esta clasificación se basa en la forma en que se destila el petróleo crudo y se separa en fracciones. [2]

Más de 6.000 artículos se fabrican a partir de subproductos de desechos de petróleo, incluidos fertilizantes , revestimientos de suelo, perfumes , insecticidas , vaselina , jabón y cápsulas de vitaminas. [33]

La imagen que aparece a continuación es un diagrama esquemático de flujo de una refinería de petróleo típica que muestra los diversos procesos unitarios y el flujo de corrientes de productos intermedios que se produce entre la materia prima de petróleo crudo de entrada y los productos finales. El diagrama muestra solo una de los literalmente cientos de configuraciones diferentes de refinerías de petróleo. El diagrama tampoco incluye ninguna de las instalaciones de refinería habituales que proporcionan servicios como vapor, agua de refrigeración y energía eléctrica, así como tanques de almacenamiento para la materia prima de petróleo crudo y para los productos intermedios y finales. [1] [53] [54] [55]

Existen muchas configuraciones de proceso distintas a la descrita anteriormente. Por ejemplo, la unidad de destilación al vacío también puede producir fracciones que se pueden refinar para obtener productos finales, como aceite para husos que se utiliza en la industria textil, aceite ligero para máquinas, aceite para motores y diversas ceras.

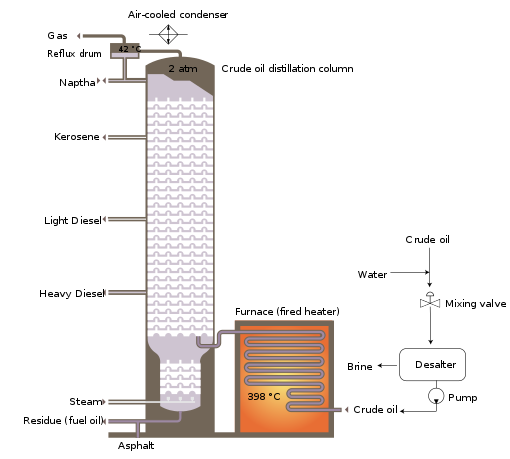

The crude oil distillation unit (CDU) is the first processing unit in virtually all petroleum refineries. The CDU distills the incoming crude oil into various fractions of different boiling ranges, each of which is then processed further in the other refinery processing units. The CDU is often referred to as the atmospheric distillation unit because it operates at slightly above atmospheric pressure.[1][2][39]Below is a schematic flow diagram of a typical crude oil distillation unit. The incoming crude oil is preheated by exchanging heat with some of the hot, distilled fractions and other streams. It is then desalted to remove inorganic salts (primarily sodium chloride).

Following the desalter, the crude oil is further heated by exchanging heat with some of the hot, distilled fractions and other streams. It is then heated in a fuel-fired furnace (fired heater) to a temperature of about 398 °C and routed into the bottom of the distillation unit.

The cooling and condensing of the distillation tower overhead is provided partially by exchanging heat with the incoming crude oil and partially by either an air-cooled or water-cooled condenser. Additional heat is removed from the distillation column by a pumparound system as shown in the diagram below.

As shown in the flow diagram, the overhead distillate fraction from the distillation column is naphtha. The fractions removed from the side of the distillation column at various points between the column top and bottom are called sidecuts. Each of the sidecuts (i.e., the kerosene, light gas oil, and heavy gas oil) is cooled by exchanging heat with the incoming crude oil. All of the fractions (i.e., the overhead naphtha, the sidecuts, and the bottom residue) are sent to intermediate storage tanks before being processed further.

A party searching for a site to construct a refinery or a chemical plant needs to consider the following issues:

Factors affecting site selection for oil refinery:

Refineries that use a large amount of steam and cooling water need to have an abundant source of water. Oil refineries, therefore, are often located nearby navigable rivers or on a seashore, nearby a port. Such location also gives access to transportation by river or by sea. The advantages of transporting crude oil by pipeline are evident, and oil companies often transport a large volume of fuel to distribution terminals by pipeline. A pipeline may not be practical for products with small output, and railcars, road tankers, and barges are used.

Petrochemical plants and solvent manufacturing (fine fractionating) plants need spaces for further processing of a large volume of refinery products, or to mix chemical additives with a product at source rather than at blending terminals.

The refining process releases a number of different chemicals into the atmosphere (see AP 42 Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors) and a notable odor normally accompanies the presence of a refinery. Aside from air pollution impacts there are also wastewater concerns,[52] risks of industrial accidents such as fire and explosion, and noise health effects due to industrial noise.[56]

Many governments worldwide have mandated restrictions on contaminants that refineries release, and most refineries have installed the equipment needed to comply with the requirements of the pertinent environmental protection regulatory agencies. In the United States, there is strong pressure to prevent the development of new refineries, and no major refinery has been built in the country since Marathon's Garyville, Louisiana facility in 1976. However, many existing refineries have been expanded during that time. Environmental restrictions and pressure to prevent the construction of new refineries may have also contributed to rising fuel prices in the United States.[57] Additionally, many refineries (more than 100 since the 1980s) have closed due to obsolescence and/or merger activity within the industry itself.[58]

Environmental and safety concerns mean that oil refineries are sometimes located some distance away from major urban areas. Nevertheless, there are many instances where refinery operations are close to populated areas and pose health risks.[59][60] In California's Contra Costa County and Solano County, a shoreline necklace of refineries, built in the early 20th century before this area was populated, and associated chemical plants are adjacent to urban areas in Richmond, Martinez, Pacheco, Concord, Pittsburg, Vallejo and Benicia, with occasional accidental events that require "shelter in place" orders to the adjacent populations. A number of refineries are located in Sherwood Park, Alberta, directly adjacent to the City of Edmonton, which has a population of over 1,000,000 residents.[61]

NIOSH criteria for occupational exposure to refined petroleum solvents have been available since 1977.[62]

Modern petroleum refining involves a complicated system of interrelated chemical reactions that produce a wide variety of petroleum-based products.[63][64] Many of these reactions require precise temperature and pressure parameters.[65] The equipment and monitoring required to ensure the proper progression of these processes is complex, and has evolved through the advancement of the scientific field of petroleum engineering.[66][67]

The wide array of high pressure and/or high temperature reactions, along with the necessary chemical additives or extracted contaminants, produces an astonishing number of potential health hazards to the oil refinery worker.[68][69] Through the advancement of technical chemical and petroleum engineering, the vast majority of these processes are automated and enclosed, thus greatly reducing the potential health impact to workers.[70] However, depending on the specific process in which a worker is engaged, as well as the particular method employed by the refinery in which he/she works, significant health hazards remain.[71]

Although occupational injuries in the United States were not routinely tracked and reported at the time, reports of the health impacts of working in an oil refinery can be found as early as the 1800s. For instance, an explosion in a Chicago refinery killed 20 workers in 1890.[72] Since then, numerous fires, explosions, and other significant events have from time to time drawn the public's attention to the health of oil refinery workers.[73] Such events continue in the 21st century, with explosions reported in refineries in Wisconsin and Germany in 2018.[74]

However, there are many less visible hazards that endanger oil refinery workers.

Given the highly automated and technically advanced nature of modern petroleum refineries, nearly all processes are contained within engineering controls and represent a substantially decreased risk of exposure to workers compared to earlier times.[70] However, certain situations or work tasks may subvert these safety mechanisms, and expose workers to a number of chemical (see table above) or physical (described below) hazards.[75][76] Examples of these scenarios include:

A 2021 systematic review associated working in the petrochemical industry with increased risk of various cancers, such as mesothelioma. It also found reduced risks of other cancers, such as stomach and rectal. The systematic review did mention that several of the associations were not due to factors directly related to the petroleum industry, rather were related to lifestyle factors such as smoking. Evidence for adverse health effects for nearby residents was also weak, with the evidence primarily centering around neighborhoods in developed countries.[79]

BTX stands for benzene, toluene, xylene. This is a group of common volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are found in the oil refinery environment, and serve as a paradigm for more in depth discussion of occupational exposure limits, chemical exposure and surveillance among refinery workers.[80][81]

The most important route of exposure for BTX chemicals is inhalation due to the low boiling point of these chemicals. The majority of the gaseous production of BTX occurs during tank cleaning and fuel transfer, which causes offgassing of these chemicals into the air.[82] Exposure can also occur through ingestion via contaminated water, but this is unlikely in an occupational setting.[83] Dermal exposure and absorption is also possible, but is again less likely in an occupational setting where appropriate personal protective equipment is in place.[83]

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) have all established occupational exposure limits (OELs) for many of the chemicals above that workers may be exposed to in petroleum refineries.[84][85][86]

Benzene, in particular, has multiple biomarkers that can be measured to determine exposure. Benzene itself can be measured in the breath, blood, and urine, and metabolites such as phenol, t,t-muconic acid (t,tMA) and S-phenylmercapturic acid (sPMA) can be measured in urine.[91] In addition to monitoring the exposure levels via these biomarkers, employers are required by OSHA to perform regular blood tests on workers to test for early signs of some of the feared hematologic outcomes, of which the most widely recognized is leukemia. Required testing includes complete blood count with cell differentials and peripheral blood smear "on a regular basis".[92] The utility of these tests is supported by formal scientific studies.[93]

Workers are at risk of physical injuries due to a large number of high-powered machines in the relatively close proximity of the oil refinery. The high pressure required for many of the chemical reactions also presents the possibility of localized system failures resulting in blunt or penetrating trauma from exploding system components.[108]

Heat is also a hazard. The temperature required for the proper progression of certain reactions in the refining process can reach 1,600 °F (870 °C).[70] As with chemicals, the operating system is designed to safely contain this hazard without injury to the worker. However, in system failures, this is a potent threat to workers' health. Concerns include both direct injury through a heat illness or injury, as well as the potential for devastating burns should the worker come in contact with super-heated reagents/equipment.[70]

Noise is another hazard. Refineries can be very loud environments, and have previously been shown to be associated with hearing loss among workers.[109] The interior environment of an oil refinery can reach levels in excess of 90 dB.[110][56] In the United States, an average of 90 dB is the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for an 8-hour work-day.[111] Noise exposures that average greater than 85 dB over an 8-hour require a hearing conservation program to regularly evaluate workers' hearing and to promote its protection.[112] Regular evaluation of workers' auditory capacity and faithful use of properly vetted hearing protection are essential parts of such programs.[113]

While not specific to the industry, oil refinery workers may also be at risk for hazards such as vehicle-related accidents, machinery-associated injuries, work in a confined space, explosions/fires, ergonomic hazards, shift-work related sleep disorders, and falls.[114]

The theory of hierarchy of controls can be applied to petroleum refineries and their efforts to ensure worker safety.

Elimination and substitution are unlikely in petroleum refineries, as many of the raw materials, waste products, and finished products are hazardous in one form or another (e.g. flammable, carcinogenic).[94][115]

Examples of engineering controls include a fire detection/extinguishing system, pressure/chemical sensors to detect/predict loss of structural integrity,[116] and adequate maintenance of piping to prevent hydrocarbon-induced corrosion (leading to structural failure).[77][78][117][118] Other examples employed in petroleum refineries include the post-construction protection of steel components with vermiculite to improve heat/fire resistance.[119] Compartmentalization can help to prevent a fire or other systems failure from spreading to affect other areas of the structure, and may help prevent dangerous reactions by keeping different chemicals separate from one another until they can be safely combined in the proper environment.[116]

Administrative controls include careful planning and oversight of the refinery cleaning, maintenance, and turnaround processes. These occur when many of the engineering controls are shut down or suppressed and may be especially dangerous to workers. Detailed coordination is necessary to ensure that maintenance of one part of the facility will not cause dangerous exposures to those performing the maintenance, or to workers in other areas of the plant. Due to the highly flammable nature of many of the involved chemicals, smoking areas are tightly controlled and carefully placed.[75]

Personal protective equipment (PPE) may be necessary depending on the specific chemical being processed or produced. Particular care is needed during sampling of the partially-completed product, tank cleaning, and other high-risk tasks as mentioned above. Such activities may require the use of impervious outerwear, acid hood, disposable coveralls, etc.[75] More generally, all personnel in operating areas should use appropriate hearing and vision protection, avoid clothes made of flammable material (nylon, Dacron, acrylic, or blends), and full-length pants and sleeves.[75]

Worker health and safety in oil refineries is closely monitored at a national level by both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).[120][121] In addition to federal monitoring, California's CalOSHA has been particularly active in protecting worker health in the industry, and adopted a policy in 2017 that requires petroleum refineries to perform a "Hierarchy of Hazard Controls Analysis" (see above "Hazard controls" section) for each process safety hazard.[122] Safety regulations have resulted in a below-average injury rate for refining industry workers. In a 2018 report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, they indicate that petroleum refinery workers have a significantly lower rate of occupational injury (0.4 OSHA-recordable cases per 100 full-time workers) than all industries (3.1 cases), oil and gas extraction (0.8 cases), and petroleum manufacturing in general (1.3 cases).[123]

Below is a list of the most common regulations referenced in petroleum refinery safety citations issued by OSHA:[124]

Corrosion of metallic components is a major factor of inefficiency in the refining process. Because it leads to equipment failure, it is a primary driver for the refinery maintenance schedule. Corrosion-related direct costs in the U.S. petroleum industry as of 1996 were estimated at US$3.7 billion.[118][125]

Corrosion occurs in various forms in the refining process, such as pitting corrosion from water droplets, embrittlement from hydrogen, and stress corrosion cracking from sulfide attack.[126] From a materials standpoint, carbon steel is used for upwards of 80 percent of refinery components, which is beneficial due to its low cost. Carbon steel is resistant to the most common forms of corrosion, particularly from hydrocarbon impurities at temperatures below 205 °C, but other corrosive chemicals and environments prevent its use everywhere. Common replacement materials are low alloy steels containing chromium and molybdenum, with stainless steels containing more chromium dealing with more corrosive environments. More expensive materials commonly used are nickel, titanium, and copper alloys. These are primarily saved for the most problematic areas where extremely high temperatures and/or very corrosive chemicals are present.[127]

Corrosion is fought by a complex system of monitoring, preventative repairs, and careful use of materials. Monitoring methods include both offline checks taken during maintenance and online monitoring. Offline checks measure corrosion after it has occurred, telling the engineer when equipment must be replaced based on the historical information they have collected. This is referred to as preventative management.

Online systems are a more modern development and are revolutionizing the way corrosion is approached. There are several types of online corrosion monitoring technologies such as linear polarization resistance, electrochemical noise and electrical resistance. Online monitoring has generally had slow reporting rates in the past (minutes or hours) and been limited by process conditions and sources of error but newer technologies can report rates up to twice per minute with much higher accuracy (referred to as real-time monitoring). This allows process engineers to treat corrosion as another process variable that can be optimized in the system. Immediate responses to process changes allow the control of corrosion mechanisms, so they can be minimized while also maximizing production output.[117] In an ideal situation having on-line corrosion information that is accurate and real-time will allow conditions that cause high corrosion rates to be identified and reduced. This is known as predictive management.

Materials methods include selecting the proper material for the application. In areas of minimal corrosion, cheap materials are preferable, but when bad corrosion can occur, more expensive but longer-lasting materials should be used. Other materials methods come in the form of protective barriers between corrosive substances and the equipment metals. These can be either a lining of refractory material such as standard Portland cement or other special acid-resistant cement that is shot onto the inner surface of the vessel. Also available are thin overlays of more expensive metals that protect cheaper metal against corrosion without requiring much material.[128]