945 Madison Avenue, also known as the Breuer Building, is a museum building on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City. The Marcel Breuer-designed structure was built to house the Whitney Museum of American Art; it subsequently held a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and from 2021 to March 2024 was the temporary quarters of the Frick Collection while the Henry Clay Frick House was being renovated.

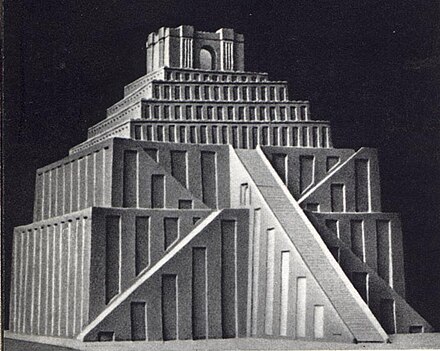

The building resides on a 13,000-square-foot (1,200 m2) site at Madison Avenue and 75th Street that was once occupied by six 1880s rowhouses. The structure and surrounding buildings contribute to the Upper East Side Historic District, a New York City and national historic district. The building is usually described as part of the Modernist art and architecture movement, and is often described as part of the narrower Brutalist style. The structure has exterior faces of variegated granite and exposed concrete and makes use of stark angular shapes, including cantilevered floors progressively extending atop its entryway, resembling an inverted ziggurat. The design was controversial, though lauded by notable architecture critics at its opening and the building defined the Whitney Museum's image for nearly 50 years, influencing subsequent projects such as the Cleveland Museum of Art's north wing and Atlanta's Central Library. Breuer's design also impacted the new Whitney Museum in Lower Manhattan by Renzo Piano, with both buildings featuring cantilevering floor plates and oversized elevators.

Ideas for the building began in the 1960s, when the Whitney Museum expanded its board and sought a new building three times the size of its existing facility, aiming to match the prominence of other major city museums. Marcel Breuer was chosen to design the assertive and experimental building, which would become the museum's third and potentially first permanent home, significantly increasing its space and amenities. Breuer and Hamilton P. Smith served as primary architects, with Michael H. Irving as the consulting architect and Paul Weidlinger as the structural engineer. 945 Madison Avenue was among Breuer's most important works, and his most major in New York City. It also was his first museum commission, first commission in Manhattan, and is his sole remaining work in Manhattan.

The museum building was built from 1964 to 1966 as the third home for the Whitney. The Whitney moved out in 2014, after nearly 50 years in the building. During these decades, the surrounding area evolved from an elegant residential neighborhood to an upscale commercial hub. In 2016, the museum building was leased to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and became the Met Breuer; the new museum contributed to the neighborhood's transformation. The Met branch closed in 2020 amid low attendance, high expenses, and mixed reviews. From 2021 to March 2024, the building became the Frick Madison, the temporary home of the Frick Collection while the Henry Clay Frick House underwent renovation. In 2023, auction house Sotheby's purchased the building and announced plans to turn the building into its global headquarters, including an auction room and gallery and exhibition space.

The museum building occupies the southeast corner of the intersection of Madison Avenue and 75th Street.[2] The property is considered to be within the Lenox Hill neighborhood within the Upper East Side,[3] one block east of Central Park.[4] The original building's site measures 103+2⁄3 by 125 feet (31.6 by 38.1 m),[5] occupying almost 13,000 square feet (1,200 m2).[6][7]

The site was formerly occupied by six 1880s rowhouses like those that surround it;[8]: 767, n.p. they had been demolished before the museum purchased the property.[9] The site was an elegant residential area before World War II; after the war, the area took on new luxury apartments and art dealers, becoming the "gallery center of New York".[10] It became an upscale commercial area by the mid-2010s, surrounded by retail shops for global fashion brands, luxury condominiums, and a large Apple Store. The 21st century site changes are partially attributed to development spurred by the Met Breuer's opening in 2016.[11]

945 Madison Avenue was designed for the Whitney Museum of American Art by Marcel Breuer & Associates – primarily Breuer himself and his partner Hamilton P. Smith. Michael H. Irving was the consulting architect, and Paul Weidlinger was the structural engineer.[5][12] The work was the most major in New York City for Breuer, and one of the most important of his career.[13] It was his first museum commission,[14] and his first and only remaining work in Manhattan.[15]: 123 [16]: 4 Breuer was originally a student of the Bauhaus architecture and design school, though he later became one of the leading figures in "New Brutalism" or Brutalism.[17]: 6

Sources variously describe the building's architectural style to be Brutalist[14][18][19] or part of the larger Modernist movement. It has been described as a Brutalist structure due to its top-heavy, massive, uninviting, and bunker-like shape, its primal form, as well as its use of exposed raw concrete.[14][17]: 6 Notable statements supporting the building's Brutalist architecture come from Ada Louise Huxtable in 1966 and Phaidon's Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, published in 2018.[14][20] While the Metropolitan Museum of Art was a tenant of the building, the museum's curators discouraged the structure's association with Brutalism; saying that Breuer never associated himself with the style, and that contrary to the Brutalist aesthetic, 945 Madison had a colorful, yet subtle, spectrum of colors, and that it overall was supposed to engage visitors.[21][22] The building's use of concrete was described by Sarah Williams Goldhagen as more of an ideological position than an aesthetic; Goldhagen stated that progressive architects at the time had to choose between using steel and glass or reinforced concrete, typically adhering to one design choice or the other. Steel and glass began to become associated with commercial buildings and mass production, while concrete gave the impression of monumentality, authenticity, and age.[23]

The overall design has been likened to an inverted ziggurat, at least since 1964;[5] Progressive Architecture likened it to the stepped Pyramid of Djoser in Egypt.[12] The building was designed in the spirit of the nearby Guggenheim Museum – another unique artistic landmark created by a renowned architect, completed seven years earlier.[6] The Guggenheim, too, had its basic form come from an overturned ziggurat, as its architect Frank Lloyd Wright stated in a 1945 Time interview. Architecture critics noticed, calling the Whitney a "squared-off Guggenheim".[24]: 8 Breuer designed the building in response to specific desires from the Whitney Museum – an "assertive, even 'controversial' presence that would announce the experimentation it sought within; a clear 'definition, even monumentality that was basic to [their] program'; but also a continued effort to be 'as human as possible,' to reflect the Whitney's tradition of warmth and intimacy" after years situated in Greenwich Village.[15]: 121–2

The five-story building,[8] as stated in 1964, counters gravity as well as uniformity, poor lighting, crowded space, and a lack of identity (most of which were issues for the Whitney's prior spaces).[5] The building utilizes "close-to-earth" materials that weather over time, intended to express age beautifully. Breuer chose coarse granite, split slate floors, bronze doors and fittings, and teakwood.[25]

The building's exterior lies in stark contrast with the streetscape of Madison Avenue. It uses reinforced concrete with variegated gray granite cladding. The structure includes a cantilevered facade in progressive steps overshadowing the Madison Avenue street front.[2][8] Breuer stated that the cantilevered floors help receive visitors before they enter the museum building.[12] The Madison Avenue entrance also features an areaway, or sunken stone courtyard.[8] Above the areaway is a canopied concrete bridge into the building's lobby, likened to a portal and sculpture by Architectural Forum.[6]

The majority of the building is faced with dark gray granite, with white veining resembling curling smoke.[6] There are 1,500 slabs of stone, each weighing 500–600 lbs.[26] The west side of the lower level and ground floor is almost fully faced in glass.[6] Besides this, the building is predominantly windowless. The majority of the upper floor windows are simply decorative, and meant to prevent claustrophobia. These trapezoidal windows jut out from the exterior walls, and visually appear to have been placed at random.[8] The windows are set at angles from 20 to 25 degrees, pointed away from the path of the sun to avoid direct light from entering the building.[27][10] The Madison Avenue facade only has a single window of this design, an oversized cyclopean pane.[15]: 125

The north and south walls are load-bearing; the walls are all made of reinforced concrete.[5] The party walls, on the building's south and east sides, are massive projecting walls of unadorned and rough reinforced concrete, separated and distinct from the more elegant rest of the exterior.[6] The north and west walls originally formed a parapet on the fifth floor, hiding the building's windowed office space from street view while bringing light into the space.[12]

The building originally had 76,830 sq ft (7,138 m2) of interior space.[5] Only about 30,000 square feet was for exhibition space; the remainder was for offices, storage, meeting rooms, a library, a restoration laboratory, stairs, elevators, and other spaces.[28] The building was designed with an earth-colored interior, utilizing concrete, bluestone, and oiled bronze.[29] The floors are of bluestone tile; the walls are white, gray, or granite-faced and relatively blank, allowing for "plenty of hanging area for the paintings inside". The ceilings use a suspended grid of concrete coffers, specially designed with rails to allow for movable partition walls. Ceiling heights vary; the second and third floors are 12'9", while the fourth floor is 17'6".[5]

As first designed, the building had a lobby, coatroom, small gallery, and loading dock on its first floor. The second, third, and fourth floors were dedicated to gallery space, each progressively larger than the space beneath it. Administrative offices were on the fifth floor, and a large mechanical penthouse acted as the sixth floor. The lower floors were designed for a sculpture gallery and courtyard, a kitchen and dining space, and storage.[5][6] While exhibition space was made relatively bare at the museum's opening (with white walls and panels on slate floors), its permanent gallery space made use of carpets, woven wall coverings, and comfortable furniture to make the space more intimate.[12] During its 2010s lease to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the interior spaces on the second and third floor were divided into various gallery rooms, compromising the original design of large open spaces.[29]

According to architect and author Robert McCarter, the building incorporates "one of the best examples of Breuer's ability to make staircases into functional sculpture", as it changes gradually and subtly in dimensions and proportions between floors, though its materials are consistent throughout.[30][31] Lighting was designed to be almost entirely artificial, with only a few windows, angled to prevent direct sunlight from entering.[5] Lights were by Edison Price, and hung from the concrete grid ceilings – both spot lighting and indirect lighting.[28]

The lobby contains an information desk and waiting spaces. Its ceiling is taken up by white circular light fixtures, each with a single bare silver-tipped bulb. The interior is rich in materials – granite, wood, bronze, and leather, though muted in color.[12] Concrete walls in the lobby are bush-hammered, and framed by smooth boardformed edges, noted by the Met's contemporary art chair as a delightful attention to detail.[21] The lobby, renovated extensively in preparation for the Met Breuer's opening, had an unoriginal gift shop structure removed, and its walls and sculptural ceiling lights were repaired. The room now features a 32-foot-long (9.8 m) matte black LED media wall, a television screen to indicate pricing, exhibitions, and other information.[21]

The Breuer Building's lower-level dining space has hosted numerous tenants. At its opening, the building had a cafeteria-style restaurant.[32] By the 1980s, the space was called the Garden Restaurant, the same name used for the restaurant in the museum's prior space beside the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden.[33]<[34] The restaurant hired a new manager and offered an English tea service, mushroom omelets, spicy pasta, and a layered "Whitney Cake".[34]

In the 1990s, the Whitney was among numerous Manhattan museums to elevate their restaurants; the Whitney contracted Sarabeth's, a New York City brunch chain of cafés with a nostalgic homeyness, noted as contrasting with the modern stark museum building. The Whitney chose Sarabeth's for its offerings of American food matching the museum's American theme, and for the chain's already substantial following. It opened in mid-July 1991.[35] The space in the museum building had wooden tables and comfortable blond wood armchairs with lively fabric upholstery situated on slate floors with stone-and-granite walls. The 80-seat dining room's west wall was entirely glass, looking out onto the museum's outdoor sculpture garden, where brunch was served on weekends. It was at times adorned with a self-portrait by Alfred Leslie,[36][34] or with Andy Warhol's Flowers 1970.[35]

For approximately 20 years, Sarabeth's operated the café there, serving breakfast and lunch.[37] Its American-themed menu included cream of tomato soup, Caesar salad, and strawberry shortcake.[35] Sarabeth's was known for its home-style desserts which were compared to works of art; in 2001 owner Sarabeth Levine chose to replicate works shown in a Wayne Thiebaud exhibit for her daily dessert specials.[38] As well, for a time, Thiebaud's painting Pie Counter, depicting rows of American-style pies and cakes, hung at the entrance to the restaurant.[35] Sarabeth's closed in January 2010, replaced by a popup operated by New York restaurateur Danny Meyer. The Whitney chose the new tenant in order to avoid contracting outside caterers, as Sarabeth's did not offer large-scale catering.[37] In 2011, Meyer closed the popup and opened his restaurant Untitled (a business which in 2015 re-opened at the Whitney's new building in the Meatpacking District, and permanently closed in 2021).[39]

Beginning in 2015 when 945 Madison held the Met Breuer, it housed a pop-up Blue Bottle Coffee shop on the fifth floor. It later added the restaurant Flora Bar (known before opening as Estela Breuer) in its lower level and sunken sculpture court.[40] It was operated by restaurateurs Ignacio Mattos and Thomas Carter, and was critically acclaimed (with two stars from The New York Times), though it was hindered by reports of a toxic work environment. The space was renovated at the Met Breuer's opening at an estimated cost of $2 million.[41] The restaurant and museum closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it was announced in February 2021 that the restaurant would not reopen when the Frick gallery opened in March.[42] A café with light dishes and snacks, operated by Joe Coffee, operated in the space during the beginning of the Frick's tenancy.[43] In November 2022, the café lease was transferred to the company the SisterYard.[44]

In 1929, philanthropist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney founded the Whitney Museum to champion American modern art. Prior to this, she had offered 500 artworks from her collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, only to have her proposal declined. Consequently, Whitney resolved to establish her own museum, initially showcasing around 700 works of American art.[45] The museum initially opened its doors to the public in 1931 at 8 West 8th Street. However, this location quickly proved inadequate.[46][47]: 824 In 1954, the museum relocated to an annex of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) at 22 West 54th Street, but this space also failed to meet the museum's rapidly growing needs.[47]: 824, 826

The Whitney began looking for sites for a new museum building in 1958, which would be three times as large as the existing facility.[47]: 826 During the 1960s, the Whitney Museum expanded its board of trustees beyond the Whitney family and their close advisors, welcoming new members such as first lady Jacqueline Kennedy.[9][15]: 122–23 The new members desired matching the Whitney to other major museums in the city. The Guggenheim had constructed a new museum in 1959 and MoMA expanded in 1951 and 1964. In the early 1960s, Marcel Breuer and Louis Kahn presented ideas for a new museum building; the two had "captured the committee's imagination" best and thus had been narrowed down from a list of five "radical" architects, none of whom had designed major public buildings in New York City.[25] In 1961, the board chose Breuer for the project.[15]: 122–23 The new building would be assertive and experimental, a recognizable icon defying the near-anonymous site the Whitney had left, in the shadow of the MoMA.[15]: 123 Breuer's building was the museum's third home,[45] and sometimes considered its first permanent location.[21] The facility tripled the Whitney's space[14] while adding a library and restaurant.[25]

In early 1963, the Whitney identified a site at Madison Avenue and 75th Street on the Upper East Side for the new museum building.[47]: 826 The site was formerly occupied by six 1880s rowhouses like those that surround it;[8]: 767, n.p. they were owned by developer and art collector Ian Woodner, who demolished them before the museum purchased the property. He had considered the site for an apartment tower but the project did not make it to fruition, prompting the land's sale to the Whitney.[47]: 826 [15]: 123 [9] The Whitney selected the location as it was relatively equidistant from the Guggenheim Museum, the Met Fifth Avenue, MoMA, and the Jewish Museum, in a neighborhood increasingly populated with private art galleries.[25] The decision to acquire the lot was publicly announced in June 1963,[47]: 826 [48] while Breuer's plans were publicly announced that December.[47]: 826 [10]

The building was designed in 1963.[13] The HRH Construction Corp. was awarded the building contract in September 1964,[49] and the museum's cornerstone was laid in a ceremony marking the beginning of construction on October 20, 1964. The cornerstone held a time capsule containing the history of the museum.[50] The building had an estimated cost of $3–4 million in 1964,[5] though it ended up costing $6 million.[27] It opened on September 28, 1966, in an event with former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who had been a trustee of the Whitney since 1963.[27] In a member preview event the night before, the museum was given four warnings by telephone of a bomb in the building. During a member preview event the night prior, the museum received four phone warnings of a bomb in the building. However, a thorough police search found no evidence of any explosives. The preview was also attended by Kennedy, along with the Whitney family, the architects, and museum board members and staff.[51]

The inaugural Whitney Biennial exhibition took place in 1973 at the Breuer Building, featuring works by 221 artists. The 1993 edition of the show also took place in the same building. Curated by Elisabeth Sussman, this event showcased art that addressed race, gender, sexuality, AIDS, and socioeconomic issues. Reviews were initially antagonistic, though it eventually became recognized as among the most notable and influential exhibitions in the museum's history.[52]

The institution grappled with space constraints for decades,[53] prompting several satellite museums and exhibition spaces in the 1970s and 1980s. The Whitney considered a significant number of expansion proposals for the Breuer Building, an unusual proportion versus what was actually built. Five different architects (including three Pritzker Prize winners) provided a total of eight proposals; only one modest design was actually built.[15]: 120 The expansions were prompted by growing crowds in recent years. The building was believed to function well with 1,000 visitors per day, though would reach three to five thousand on busier days. The Whitney thus acquired five brownstone buildings south to 74th Street, and had Breuer design knockout panels in the outer walls at each floor, with plans for eventual expansion.[15]: 127

In 1978, the Whitney's trustees considered a 35-story tower expansion to the building's south, amid plans for MoMA's museum-condominium "Museum Tower". The plan would let Italian developers create a luxury mixed-use tower with Whitney galleries on its lower floors. The proposed high-tech design was created by the British Norman Foster Associates and Derek Walker Associates.[15]: 128 The project was cancelled when it was pointed out that height restrictions would make the mixed-use development unprofitable.[54] The next expansion proposal was by Michael Graves, first announced in 1981, three months after Breuer's death. The first proposal came in May 1985, revised in 1987 and 1988. Graves' postmodern additions were heavily condemned for their bulk and for not harmonizing with the existing building.[15]: 130–32

The first polarizing proposal was met with a petition against the design, signed by I.M. Pei, Isamu Noguchi, and about 600 other art and architecture professionals. Breuer's wife Constance and his architect partner Hamilton Smith also weighed in against the design, preferring Breuer's work be torn down.[15]: 134 Certain critics prompted the Whitney's board to request the 1987 revision, and his final revision was also disliked. His main advocate, director Thomas Armstrong III, resigned in 1990 before the third revision's approval process had begun.[15]: 136, 139

The board of the Whitney still desired an expansion, though now aimed for a near-imperceptible change. The museum purchased surrounding townhouses (five on Madison, two on 74th, and a two-story building between the two sets).[15]: 142 The museum board hired Gluckman Mayner Architects to perform a $135 million two-phase renovation, spanning from 1995 to 1998.[55][2] The expansion involved renovating three townhouses to create office space, connecting them to the museum via Breuer's knockout panels. A new two-story library was built within a rear yard space. The Breuer Building's fifth floor terraces were enclosed, and the floor was converted into gallery space. The building was also extensively cleaned and given new HVAC systems. The work was made to look invisible – the new galleries appeared original, and the new administrative spaces preserved the historic brownstones' exteriors and much of the interiors.[15]: 142–43 The new fifth floor gallery was funded by then-chairman Leonard Lauder, and was named for him and his wife.[52]

In 2001, the Whitney held a closed competition to further increase space; this time with a more visible addition to the building. Gluckman Mayner submitted a new proposal,[56] along with the firms of Peter Eisenman, Steven Holl, Machado & Silvetti, Jean Nouvel, Norman Foster, and Rem Koolhaas. The Whitney selected Koolhaas and his firm OMA. The proposed building would be enormous, cantilevering above and over the Breuer Building. The museum kept the proposal relatively confidential and ultimately abandoned it in 2003, prior to any review processes, citing economic concerns and poor timing (the economics and public willpower of New York City and the country had changed dramatically following the September 11 attacks late in 2001). The project's abandonment was once of the major issues prompting the Whitney's director Maxwell L. Anderson to resign, which was compared to Armstrong III's resignation in 1990.[15]: 144–45

Around 2005, amid further planned expansions, the Whitney had the neighboring 943 Madison Avenue demolished and rebuilt, and 941 Madison's depth reduced from 31 to 17 feet (9.4 to 5.2 m). The work was controversial, seen by some preservationists as too severe, and by some in the architecture field as not bold enough.[57] The Whitney hired Italian architect Renzo Piano to design an addition in 2004; Piano proposed a nine-story tower inset into the block, connected to the Breuer Building with glass bridges. His proposal would leave the Breuer Building and surrounding brownstones mostly untouched. Preservationists worked to save two brownstones that would be demolished; that paired with skyrocketing construction costs largely doomed the project.[15]: 148, 151 The Whitney abandoned Piano's proposal in 2005, deciding instead for him to design a new building for the museum in Lower Manhattan.[15]: 121 The Whitney operated at the Breuer Building until 2014, until it moved to the Renzo Piano-designed building in the Meatpacking District the following year.[58]

The Whitney's final exhibit in the Breuer Building was a Jeff Koons retrospective in 2014.[59] It was the largest survey the Whitney made dedicated to a single artist, and was among the Whitney's highest-attended events.[52] The Whitney still maintains ownership of the building, so its donor plaques remain, as does Dwellings, a miniature work of art by Charles Simonds, located in the building's stairwell as well as the rooftop and windowsill of neighboring 940 Madison Avenue.[29][60] The portion inside the Breuer Building was commissioned for the Whitney, and is the most accessible component of the artwork. The piece will remain in its current location during Sotheby's ownership of the structure.[61]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, looking to build its presence in the modern and contemporary art scenes, agreed to lease the building in 2011,[62] to enter into effect around 2015.[21] The museum was also looking to display its contemporary and modern art while its Fifth Avenue building's wing was renovated, making the move potentially temporary from the beginning.[26] The building underwent a $12.95 million renovation ahead of the Met opening.[41] This included a thorough cleaning, led by Beyer Blinder Belle. The architects also stripped decades of additions, decluttering the lobby of posters, postcard racks, and wires.[29] Floors were re-waxed, and the lobby's lights were replaced with custom LED bulbs.[40] The restoration was careful to preserve elements of natural aging; Breuer chose materials like wood and bronze that would change positively over time.[21]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened the Met Breuer at 945 Madison Avenue in 2016, naming the branch after its architect. The museum housed its contemporary art in the building for the next four years.[58] In a surprise announcement in September 2018, the Met announced its plan to close the Met Breuer and hand over the building to the Frick Collection. The Met's director stated that the museum's future was in its main building, and simultaneously announced it will renovate its modern and contemporary galleries at a proposed cost of $500 million ($100 million less than was announced for the project in 2014). The decision would offload three years of rent from its eight-year lease, remove $18 million in annual operation costs, and allow the Frick to open in 2020 in the building with a $45 million sublease (an undisclosed portion of the Met's lease from the Whitney Museum).[41][63] Robin Pogrebin, writing for The New York Times, stated that critics of the Met Breuer would undoubtedly view the news of the Met Breuer closing as confirmation that the branch was a bad idea.[63]

The museum was originally set to close in July 2020, after its last exhibition, though it closed temporarily during the COVID-19 pandemic in March of that year. That June, the Met decided to close its space there permanently, despite the short-lived exhibition.[58][64] The closure was a priority of incoming Met director Max Hollein, as it had an expensive lease, low attendance, and mixed reviews.[65]

The museum building reopened in March 2021 as the Frick Madison, a temporary gallery of the Frick Collection. Since 1935, the Frick had been situated at Henry Clay Frick House, five blocks south of the Breuer Building. However, due to a planned renovation, the museum was set to temporarily operate at 945 Madison for approximately two years.[66] The Frick Collection was looking to open a temporary exhibit during its planned 2020–2022 renovations, and sought the Guggenheim, which was only available for four months. The Metropolitan Museum of Art lent use of the Breuer Building instead; the Met had leased the building from the Whitney in a deal set to expire in 2023.[66]

The move was seen as remarkable, given that Henry Clay Frick's will stipulated that his purchases (about two-thirds of the museum's holdings) cannot be lent to any other institutions.[67] The Frick Madison's opening became the first and potentially only time these works are being moved. The building houses its old masters collection, including 104 paintings, along with sculptures, vases, and clocks. Dutch and Flemish paintings occupy the second floor, while Italian and Spanish works take up the third, along with Mughal carpets and Chinese porcelain. The fourth floor features British and French works.[66] The temporary museum is the second reported occurrence of non-Modern works exhibited in the Modernist Breuer building, after the Met Breuer's inaugural exhibit.[18] Here the Frick Collection will maintain visitorship, membership, and its public attention, rather than if it shuttered for two or more years.[63] Most of the 1,500-piece collection of artwork is being placed in storage in the Breuer Building, and about 300 are on display on the second through fourth floors.[18]

The artwork is exhibited against stark dark gray walls, with most walls only holding one to two paintings; this contrasted with the ornate setting the paintings had inside the Frick Mansion. There is no protective glass, nor any plaques or signs (a standard the Frick Collection held at its longtime home), save for the artist's name on some frames. Visitors are encouraged to use the museum's app to learn about the artworks in lieu of visible signage. There are no barriers and few display cases, allowing guests to see works unimpaired. Taller works are set low to the ground, giving an illusion of entering the scenes depicted.[18][66] In April 2023, the Frick announced the Frick Madison would close the next year in preparation for the reopening of the Frick Mansion;[68] the Frick Madison closed on March 3, 2024.[69][70]

During much of the Frick Madison's lease, the building's future after 2023 was uncertain.[63] There were no announced tenants beyond the Frick Collection, and the Whitney Museum reportedly could not sell the building for the foreseeable future. The 20-year restriction was set in 2008 as part of a $131 million gift from Leonard Lauder, former board chairman emeritus, the largest donation in the museum's history.[15]: 121 The museum was reported to be considering a sale by late 2021.[71] Lauder was initially opposed to the Whitney's move downtown, though he eventually grew to like the new museum building, which was named for him in 2016.[19] In June 2023, the auction house Sotheby's agreed to purchase the building for approximately $100 million.[72][73] 945 Madison Avenue is planned to house Sotheby's headquarters, including its galleries, exhibition space, and auction room.[74] The company took over the property after the Frick Collection's sublease ended in August 2024;[73] it plans to open the new space in 2025, with galleries free and open to the public.[74] The auction house will hire an architect to rework interior spaces, but will preserve the integrity of the building.[19]

The building was controversial to the public at its opening;[45] comments likened it to a fortress or garage, while some admired it for being striking or romantic.[27] It was nevertheless well-received as a masterpiece by critics in the 1960s, in architecture, art, and general magazines and newspapers.[13] In 1966, Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times referred to the building as "harsh and handsome", and a site that grows on the viewer slowly over time, though she admitted it was "the most disliked building in New York".[14] Huxtable noted that the building may be too severe and gloomy for many people's tastes, and, in the same year, art critic Emily Genauer echoed her statement, calling the building "oppressively heavy" and "the Madison Avenue Monster".[9] In 1966, Progressive Architecture criticized the 75th Street facade for being incongruous with the Madison Avenue facade and for appearing empty save for its sculptural windows.[12]

In 2010, the Times' architecture critic Christopher Gray called it "ornery and menacing", perhaps "New York's most bellicose work of architecture".[9] In a reply, architectural historian Victoria Newhouse called the museum one of the most successfully designed in the world; she had traveled to hundreds in order to write two books about museum architecture. She prompted Huxtable to give a new statement in support of the building, after Gray had taken her words out of context in his review.[75]

Breuer and the Whitney sought to build a controversial structure. Breuer's commission brief (contradicting itself) told him to create an assertive or even controversial structure that represents the Whitney's experimental art, and with a clear definition and monumentality, though aiming to be "as human as possible" and reflect the museum's custom for "warmth and intimacy".[15]: 123 [25] Critics supported the controversial design; Peter Blake stated that "Any museum of art that does not, somehow, shake up the neighbor-hood is at least a partial failure. Whatever else Breuer's museum may do to its neighbors, it will never bore them."[28] The museum's design won Marcel Breuer the 1968 Albert S. Bard Award for Excellence in Architecture and Urban Design, and a 1970 Honor Award from the AIA Journal.[15]: 126

Architectural Forum, in 1966, stated that the building was "intended to be a landmark".[6] It was first listed in 1981, as a contributing structure to the Upper East Side Historic District (as designated by New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission).[8] Despite this, it was listed as a noncontributing structure in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) district of the same name in 1984. The museum was independently added to the State Register of Historic Places in June 1986 and was deemed eligible for a standalone entry in the National Register in September of that year. In 2006, the NRHP's historic district listing was revised, with one of the modifications being to now list the museum building as a contributing structure.[13][76]

The building came to define the Whitney Museum's image, as its iconic home for almost 50 years.[15]: 121–2 [9] Marcel Breuer's work with the Whitney Museum prompted an invitation to design for the Cleveland Museum of Art. Breuer was the only person invited to submit a design for its north wing, as he showed an understanding for museum needs and understanding for materials with the Whitney project. Breuer's wing opened in 1971,[77] designed with similarities to the Whitney Museum, including a cantilevered concrete entrance canopy outside and a suspended coffered grid inside.[78][79]

Breuer's work for the Whitney also influenced Atlanta Public Library director Carlton C. Rochell, who nominated Breuer to design a new central library; Breuer and his partner Hamilton Smith won the commission, paired with the Atlanta firm Stevens & Wilkinson.[80][81] The Atlanta Central Library, completed in 1980, is seen as a "confident progression" of the Whitney design.[80] The Breuer Building also influenced Renzo Piano's design of the new Whitney Museum in Lower Manhattan. The building, opened in 2015, also features cantilevering floor plates that progressively extend over a portion of the street; both museum buildings also feature oversized elevators.[26] A 2017 exhibit at the Met Breuer, Breuer Revisited: New Photographs by Luisa Lambri and Bas Princen, featured artistic photographs of four of Marcel Breuer's works, including 945 Madison Avenue.[82][83]

In 2024, watch company Toledano and Chan revealed their first watch, the B/1, inspired by the windows found on the Breuer building and the founders' admiration for brutalist architecture.[84][85]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)