A well is an excavation or structure created in the earth by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. The well water is drawn up by a pump, or using containers, such as buckets or large water bags that are raised mechanically or by hand. Water can also be injected back into the aquifer through the well. Wells were first constructed at least eight thousand years ago and historically vary in construction from a simple scoop in the sediment of a dry watercourse to the qanats of Iran, and the stepwells and sakiehs of India. Placing a lining in the well shaft helps create stability, and linings of wood or wickerwork date back at least as far as the Iron Age.

Wells have traditionally been sunk by hand digging, as is still the case in rural areas of the developing world. These wells are inexpensive and low-tech as they use mostly manual labour, and the structure can be lined with brick or stone as the excavation proceeds. A more modern method called caissoning uses pre-cast reinforced concrete well rings that are lowered into the hole. Driven wells can be created in unconsolidated material with a well hole structure, which consists of a hardened drive point and a screen of perforated pipe, after which a pump is installed to collect the water. Deeper wells can be excavated by hand drilling methods or machine drilling, using a bit in a borehole. Drilled wells are usually cased with a factory-made pipe composed of steel or plastic. Drilled wells can access water at much greater depths than dug wells.

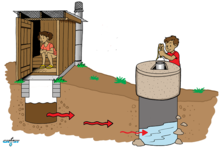

Two broad classes of well are shallow or unconfined wells completed within the uppermost saturated aquifer at that location, and deep or confined wells, sunk through an impermeable stratum into an aquifer beneath. A collector well can be constructed adjacent to a freshwater lake or stream with water percolating through the intervening material. The site of a well can be selected by a hydrogeologist, or groundwater surveyor. Water may be pumped or hand drawn. Impurities from the surface can easily reach shallow sources and contamination of the supply by pathogens or chemical contaminants needs to be avoided. Well water typically contains more minerals in solution than surface water and may require treatment before being potable. Soil salination can occur as the water table falls and the surrounding soil begins to dry out. Another environmental problem is the potential for methane to seep into the water.

Very early neolithic wells are known from the Eastern Mediterranean:[1] The oldest reliably dated well is from the pre-pottery neolithic (PPN) site of Kissonerga-Mylouthkia on Cyprus. At around 8400 BC a shaft (well 116) of circular diameter was driven through limestone to reach an aquifer at a depth of 8 metres (26 ft). Well 2070 from Kissonerga-Mylouthkia, dating to the late PPN, reaches a depth of 13 metres (43 ft). Other slightly younger wells are known from this site and from neighbouring Parekklisha-Shillourokambos. A first stone lined[2] well of 5.5 metres (18 ft) depth is documented from a drowned final PPN (c. 7000 BC) site at ‘Atlit-Yam off the coast near modern Haifa in Israel.

,_Brunnenbaureste_um_5300_v._Ch._.jpg/440px-Kückhoven_(Erkelenz),_Brunnenbaureste_um_5300_v._Ch._.jpg)

Wood-lined wells are known from the early Neolithic Linear Pottery culture, for example in Ostrov, Czech Republic, dated 5265 BC,[3] Kückhoven (an outlying centre of Erkelenz), dated 5300 BC,[4] and Eythra in Schletz (an outlying centre of Asparn an der Zaya) in Austria, dated 5200 BC.[5]

The neolithic Chinese discovered and made extensive use of deep drilled groundwater for drinking.[citation needed] The Chinese text The Book of Changes, originally a divination text of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 -771 BC), contains an entry describing how the ancient Chinese maintained their wells and protected their sources of water.[6] A well excavated at the Hemedu excavation site was believed to have been built during the neolithic era.[7] The well was cased by four rows of logs with a square frame attached to them at the top of the well. 60 additional tile wells southwest of Beijing are also believed to have been built around 600 BC for drinking and irrigation.[7][8]

In Egypt, shadoofs and sakias are used.[9][10] The sakia is much more efficient, as it can bring up water from a depth of 10 metres (versus the 3 metres of the shadoof). The sakia is the Egyptian version of the noria. Some of the world's oldest known wells, located in Cyprus, date to 7000–8,500 BC.[11] Two wells from the Neolithic period, around 6500 BC, have been discovered in Israel. One is in Atlit, on the northern coast of Israel, and the other is in the Jezreel Valley.[12]

Wells for other purposes came along much later, historically. The first recorded salt well was dug in the Sichuan province of China around 2,250 years ago. This was the first time that ancient water well technology was applied successfully for the exploitation of salt, and marked the beginning of Sichuan's salt drilling industry.[6] The earliest known oil wells were also drilled in China, in 347 CE. These wells had depths of up to about 240 metres (790 ft) and were drilled using bits attached to bamboo poles.[13] The oil was burned to evaporate brine and produce salt. By the 10th century, extensive bamboo pipelines connected oil wells with salt springs. The ancient records of China and Japan are said to contain many allusions to the use of natural gas for lighting and heating. Petroleum was known as Burning water in Japan in the 7th century.[14]

Hasta hace algunos siglos, todos los pozos artificiales eran pozos excavados a mano sin bombas y de distintos grados de sofisticación, y siguen siendo una fuente muy importante de agua potable en algunas zonas rurales en desarrollo, donde hoy en día se excavan y utilizan de forma rutinaria. Su carácter indispensable ha dado lugar a numerosas referencias literarias, tanto literales como figurativas, entre ellas la referencia al encuentro de Jesús con una mujer en el pozo de Jacob ( Juan 4:6) en la Biblia y la canción infantil " Ding Dong Bell " sobre un gato en un pozo.

Los pozos excavados a mano son excavaciones con diámetros lo suficientemente grandes como para que puedan pasar una o más personas con palas hasta debajo del nivel freático . La excavación se apuntala horizontalmente para evitar que los desprendimientos de tierra o la erosión pongan en peligro a las personas que excavan. Pueden estar revestidos con piedra o ladrillo; extender este revestimiento hacia arriba por encima de la superficie del suelo para formar una pared alrededor del pozo sirve para reducir tanto la contaminación como las caídas accidentales en el pozo.

Un método más moderno, llamado "caissoning", utiliza anillos prefabricados de hormigón armado o de hormigón simple que se bajan al pozo. Un equipo de excavación de pozos excava debajo de un anillo de corte y la columna del pozo se hunde lentamente en el acuífero , al mismo tiempo que protege al equipo del colapso del pozo .

Los pozos excavados a mano son económicos y de baja tecnología (en comparación con la perforación) y utilizan principalmente mano de obra para acceder al agua subterránea en las zonas rurales de los países en desarrollo. Pueden construirse con un alto grado de participación comunitaria o por empresarios locales que se especializan en pozos excavados a mano. Se han excavado con éxito hasta 60 metros (200 pies). Tienen bajos costos de operación y mantenimiento, en parte porque el agua se puede extraer a mano, sin una bomba. El agua a menudo proviene de un acuífero o de aguas subterráneas, y se puede profundizar fácilmente, lo que puede ser necesario si el nivel del agua subterránea baja, al extender el revestimiento más hacia el interior del acuífero. El rendimiento de los pozos excavados a mano existentes se puede mejorar mediante la profundización o la introducción de túneles verticales o tuberías perforadas.

Los pozos excavados a mano tienen numerosos inconvenientes. Puede resultar poco práctico excavarlos a mano en zonas donde hay roca dura y su excavación y revestimiento pueden llevar mucho tiempo incluso en zonas favorables. Debido a que explotan acuíferos poco profundos, el pozo puede ser susceptible a fluctuaciones de rendimiento y posible contaminación por aguas superficiales, incluidas las aguas residuales. La construcción de pozos excavados a mano generalmente requiere el uso de un equipo de construcción bien capacitado, y la inversión de capital en equipos como moldes de anillos de hormigón, equipo de elevación pesada, encofrado de pozos, bombas de drenaje motorizadas y combustible puede ser alta para las personas en los países en desarrollo. La construcción de pozos excavados a mano puede ser peligrosa debido al colapso del pozo, la caída de objetos y la asfixia, incluso por los gases de escape de las bombas de drenaje.

El pozo de agua de Woodingdean , excavado a mano entre 1858 y 1862, es el pozo excavado a mano más profundo, con 392 metros (1285 pies). [15] El Gran Pozo de Greensburg, Kansas , se considera el pozo excavado a mano más grande del mundo, con 109 pies (33 m) de profundidad y 32 pies (9,8 m) de diámetro. Sin embargo, el Pozo de José en la Ciudadela de El Cairo, con 280 pies (85 m) de profundidad, y el Pozzo di San Patrizio (Pozo de San Patricio), construido en 1527 en Orvieto, Italia , con 61 metros (200 pies) de profundidad por 13 metros (43 pies) de ancho [16], son ambos más grandes en volumen.

Los pozos hincados pueden crearse de manera muy simple en material no consolidado con una estructura de pozo , que consiste en una punta de hincado endurecida y una pantalla (tubo perforado). La punta simplemente se martilla en el suelo, generalmente con un trípode y un hincado , y se agregan secciones de tubo según sea necesario. Un hincado es un tubo con peso que se desliza sobre el tubo que se está hincando y se deja caer repetidamente sobre él. Cuando se encuentra agua subterránea , se limpia el pozo de sedimentos y se instala una bomba. [17]

Los pozos perforados se construyen utilizando varios tipos de máquinas de perforación, como las rotativas de cabezal superior, las rotativas de mesa o las de cable, que utilizan vástagos de perforación que giran para cortar la formación, de ahí el término "perforación".

Los pozos perforados se pueden excavar mediante métodos simples de perforación manual (barrena, perforación con lodo, perforación con chorro de agua, perforación con percusión manual) o perforación con máquina (barrena, perforación rotatoria, perforación con percusión, perforación con martillo en el fondo del pozo). El método de perforación rotatoria en roca profunda es el más común. La perforación rotatoria se puede utilizar en el 90 % de los tipos de formación (consolidada).

Los pozos perforados pueden extraer agua de un nivel mucho más profundo que los pozos excavados, a menudo hasta varios cientos de metros. [18]

Drilled wells with electric pumps are used throughout the world, typically in rural or sparsely populated areas, though many urban areas are supplied partly by municipal wells. Most shallow well drilling machines are mounted on large trucks, trailers, or tracked vehicle carriages. Water wells typically range from 3 to 18 metres (10–60 ft) deep, but in some areas it can go deeper than 900 metres (3,000 ft).[citation needed]

Rotary drilling machines use a segmented steel drilling string, typically made up of 3m (10ft), 6 m (20 ft) to 8m (26ft) sections of steel tubing that are threaded together, with a bit or other drilling device at the bottom end. Some rotary drilling machines are designed to install (by driving or drilling) a steel casing into the well in conjunction with the drilling of the actual bore hole. Air and/or water is used as a circulation fluid to displace cuttings and cool bits during the drilling. Another form of rotary-style drilling, termed mud rotary, makes use of a specially made mud, or drilling fluid, which is constantly being altered during the drill so that it can consistently create enough hydraulic pressure to hold the side walls of the bore hole open, regardless of the presence of a casing in the well. Typically, boreholes drilled into solid rock are not cased until after the drilling process is completed, regardless of the machinery used.

The oldest form of drilling machinery is the cable tool, still used today. Specifically designed to raise and lower a bit into the bore hole, the spudding of the drill causes the bit to be raised and dropped onto the bottom of the hole, and the design of the cable causes the bit to twist at approximately 1⁄4 revolution per drop, thereby creating a drilling action. Unlike rotary drilling, cable tool drilling requires the drilling action to be stopped so that the bore hole can be bailed or emptied of drilled cuttings. Cable tool drilling rigs are rare as they tend to be 10x slower to drill through materials compared to similar diameter rotary air or rotary mud equipped rigs.

Los pozos perforados suelen estar revestidos con una tubería fabricada en fábrica, normalmente de acero (en la perforación con herramientas rotativas de aire o con cable) o de plástico / PVC (en los pozos rotativos de lodo, también presentes en los pozos perforados en roca sólida). La tubería de revestimiento se construye soldando, ya sea química o térmicamente, segmentos de tubería de revestimiento entre sí. Si la tubería de revestimiento se instala durante la perforación, la mayoría de las perforadoras la introducirán en el suelo a medida que avanza el pozo, mientras que algunas máquinas más nuevas permitirán que la tubería de revestimiento gire y se perfore en la formación de manera similar a como avanza la broca justo debajo. El PVC o el plástico normalmente se sueldan con disolvente y luego se bajan al pozo perforado, se apilan verticalmente con sus extremos anidados y pegados o estriados entre sí. Las secciones de tubería de revestimiento suelen tener 6 metros (20 pies) o más de longitud y entre 4 y 12 pulgadas (10 y 30 cm) de diámetro, según el uso previsto del pozo y las condiciones locales del agua subterránea.

La contaminación superficial de los pozos en los Estados Unidos se controla típicamente mediante el uso de un sello de superficie . Se perfora un agujero grande hasta una profundidad predeterminada o hasta una formación de confinamiento (arcilla o lecho de roca, por ejemplo), y luego se completa un agujero más pequeño para el pozo desde ese punto en adelante. El pozo generalmente se entuba desde la superficie hacia abajo en el agujero más pequeño con una carcasa que tiene el mismo diámetro que ese agujero. El espacio anular entre el agujero grande y la carcasa más pequeña se llena con arcilla de bentonita , hormigón u otro material sellador. Esto crea un sello impermeable desde la superficie hasta la siguiente capa de confinamiento que evita que los contaminantes se desplacen por las paredes laterales externas de la carcasa o el pozo y hacia el acuífero . Además, los pozos generalmente se tapan con una tapa o sello de pozo diseñado que ventila el aire a través de una pantalla hacia el pozo, pero evita que los insectos, los animales pequeños y las personas no autorizadas accedan al pozo.

At the bottom of wells, based on formation, a screening device, filter pack, slotted casing, or open bore hole is left to allow the flow of water into the well. Constructed screens are typically used in unconsolidated formations (sands, gravels, etc.), allowing water and a percentage of the formation to pass through the screen. Allowing some material to pass through creates a large area filter out of the rest of the formation, as the amount of material present to pass into the well slowly decreases and is removed from the well. Rock wells are typically cased with a PVC liner/casing and screen or slotted casing at the bottom, this is mostly present just to keep rocks from entering the pump assembly. Some wells utilize a filter pack method, where an undersized screen or slotted casing is placed inside the well and a filter medium is packed around the screen, between the screen and the borehole or casing. This allows the water to be filtered of unwanted materials before entering the well and pumping zone.

There are two broad classes of drilled-well types, based on the type of aquifer the well is in:

A special type of water well may be constructed adjacent to freshwater lakes or streams. Commonly called a collector well but sometimes referred to by the trade name Ranney well or Ranney collector, this type of well involves sinking a caisson vertically below the top of the aquifer and then advancing lateral collectors out of the caisson and beneath the surface water body. Pumping from within the caisson induces infiltration of water from the surface water body into the aquifer, where it is collected by the collector well laterals and conveyed into the caisson where it can be pumped to the ground surface.[citation needed]

Two additional broad classes of well types may be distinguished, based on the use of the well:

A water well constructed for pumping groundwater can be used passively as a monitoring well and a small diameter well can be pumped, but this distinction by use is common.[citation needed]

Before excavation, information about the geology, water table depth, seasonal fluctuations, recharge area and rate should be found if possible. This work can be done by a hydrogeologist, or a groundwater surveyor using a variety of tools including electro-seismic surveying,[20] any available information from nearby wells, geologic maps, and sometimes geophysical imaging. These professionals provide advice that is almost as accurate a driller who has experience and knowledge of nearby wells/bores and the most suitable drilling technique based on the expected target depth.

.jpg/440px-Hand_water_pump_in_India_(3382861084).jpg)

Shallow pumping wells can often supply drinking water at a very low cost. However, impurities from the surface easily reach shallow sources, which leads to a greater risk of contamination for these wells compared to deeper wells. Contaminated wells can lead to the spread of various waterborne diseases. Dug and driven wells are relatively easy to contaminate; for instance, most dug wells are unreliable in the majority of the United States.[21] Some research has found that, in cold regions, changes in river flow and flooding caused by extreme rainfall or snowmelt can degrade well water quality.[22]

Most of the bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi that contaminate well water comes from fecal material from humans and other animals. Common bacterial contaminants include E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter jejuni. Common viral contaminants include norovirus, sapovirus, rotavirus, enteroviruses, and hepatitis A and E. Parasites include Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora cayetanensis, and microsporidia.[21]

Chemical contamination is a common problem with groundwater.[23] Nitrates from sewage, sewage sludge or fertilizer are a particular problem for babies and young children. Pollutant chemicals include pesticides and volatile organic compounds from gasoline, dry-cleaning, the fuel additive methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), and perchlorate from rocket fuel, airbag inflators, and other artificial and natural sources.[citation needed]

Several minerals are also contaminants, including lead leached from brass fittings or old lead pipes, chromium VI from electroplating and other sources, naturally occurring arsenic, radon, and uranium—all of which can cause cancer—and naturally occurring fluoride, which is desirable in low quantities to prevent tooth decay, but can cause dental fluorosis in higher concentrations.[21]

Some chemicals are commonly present in water wells at levels that are not toxic, but can cause other problems. Calcium and magnesium cause what is known as hard water, which can precipitate and clog pipes or burn out water heaters. Iron and manganese can appear as dark flecks that stain clothing and plumbing, and can promote the growth of iron and manganese bacteria that can form slimy black colonies that clog pipes.[21]

The quality of the well water can be significantly increased by lining the well, sealing the well head, fitting a self-priming hand pump, constructing an apron, ensuring the area is kept clean and free from stagnant water and animals, moving sources of contamination (pit latrines, garbage pits, on-site sewer systems) and carrying out hygiene education. The well should be cleaned with 1% chlorine solution after construction and periodically every 6 months.[citation needed]

Well holes should be covered to prevent loose debris, animals, animal excrement, and wind-blown foreign matter from falling into the hole and decomposing. The cover should be able to be in place at all times, including when drawing water from the well. A suspended roof over an open hole helps to some degree, but ideally the cover should be tight fitting and fully enclosing, with only a screened air vent.[citation needed]

Minimum distances and soil percolation requirements between sewage disposal sites and water wells need to be observed. Rules regarding the design and installation of private and municipal septic systems take all these factors into account so that nearby drinking water sources are protected.

Education of the general population in society also plays an important role in protecting drinking water.[citation needed]

Cleanup of contaminated groundwater tends to be very costly. Effective remediation of groundwater is generally very difficult. Contamination of groundwater from surface and subsurface sources can usually be dramatically reduced by correctly centering the casing during construction and filling the casing annulus with an appropriate sealing material. The sealing material (grout) should be placed from immediately above the production zone back to surface, because, in the absence of a correctly constructed casing seal, contaminated fluid can travel into the well through the casing annulus. Centering devices are important (usually one per length of casing or at maximum intervals of 9 m) to ensure that the grouted annular space is of even thickness.[citation needed]

Al construir un nuevo pozo de prueba, se considera que la mejor práctica es invertir en una batería completa de pruebas químicas y biológicas del agua del pozo en cuestión. Hay tratamientos en el punto de uso disponibles para propiedades individuales y a menudo se construyen plantas de tratamiento para suministros de agua municipales que sufren contaminación. La mayoría de estos métodos de tratamiento implican la filtración de los contaminantes en cuestión, y se puede obtener protección adicional instalando rejillas en los revestimientos de los pozos solo en profundidades donde no haya contaminación. [ cita requerida ]

El agua de pozo para uso personal suele filtrarse con procesadores de agua por ósmosis inversa ; este proceso puede eliminar partículas muy pequeñas. Una forma sencilla y eficaz de matar microorganismos es hervir el agua por completo durante uno a tres minutos, según la ubicación. Un pozo doméstico contaminado por microorganismos puede tratarse inicialmente con cloración de choque con lejía, lo que genera concentraciones cientos de veces mayores que las que se encuentran en los sistemas de agua comunitarios; sin embargo, esto no solucionará ningún problema estructural que haya provocado la contaminación y, por lo general, requiere cierta experiencia y pruebas para una aplicación eficaz. [21]

Después del proceso de filtración, es común implementar un sistema ultravioleta (UV) para matar los patógenos en el agua. La luz ultravioleta afecta el ADN del patógeno mediante fotones UV-C que atraviesan la pared celular. La desinfección por UV ha ganado popularidad en las últimas décadas, ya que es un método de tratamiento del agua sin químicos. [24]

Un riesgo con la colocación de pozos de agua es la salinización del suelo que ocurre cuando el nivel freático del suelo comienza a bajar y la sal comienza a acumularse a medida que el suelo comienza a secarse. [25] Otro problema ambiental que es muy frecuente en la perforación de pozos de agua es la posibilidad de que el metano se filtre.

La posibilidad de salinización del suelo es un gran riesgo a la hora de elegir la ubicación de los pozos de agua. La salinización del suelo se produce cuando el nivel freático del suelo desciende con el tiempo y la sal comienza a acumularse. A su vez, la mayor cantidad de sal comienza a secar el suelo. El aumento del nivel de sal en el suelo puede provocar la degradación del suelo y puede ser muy perjudicial para la vegetación. [ cita requerida ]

Methane, an asphyxiant, is a chemical compound that is the main component of natural gas. When methane is introduced into a confined space, it displaces oxygen, reducing oxygen concentration to a level low enough to pose a threat to humans and other aerobic organisms but still high enough for a risk of spontaneous or externally caused explosion. This potential for explosion is what poses such a danger in regards to the drilling and placement of water wells.[citation needed]

Low levels of methane in drinking water are not considered toxic. When methane seeps into a water supply, it is commonly referred to as "methane migration". This can be caused by old natural gas wells near water well systems becoming abandoned and no longer monitored.[citation needed]

Lately,[when?] however, the described wells/pumps are no longer very efficient and can be replaced by either handpumps or treadle pumps. Another alternative is the use of self-dug wells, electrical deep-well pumps (for higher depths). Appropriate technology organizations as Practical Action are now[when?] supplying information on how to build/set-up (DIY) handpumps and treadle pumps in practice.[26][27]

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS or PFASs) are a group of synthetic organofluorine chemical compounds that have multiple fluorine atoms attached to an alkyl chain. PFAS are a group of "forever chemicals" that spread very quickly and very far in ground water polluting it permanently. Water wells near certain airports where any form fire fighting or training activities occurred up to 2010 are likely to be contaminated by PFAS.

A study concluded that of ~39 million groundwater wells 6-20% are at high risk of running dry if local groundwater levels decline by less than five meters, or – as with many areas and possibly more than half of major aquifers[28] – continue to decline.[29][30][further explanation needed]

Springs and wells have had cultural significance since prehistoric times, leading to the foundation of towns such as Wells and Bath in Somerset. Interest in health benefits led to the growth of spa towns including many with wells in their name, examples being Llandrindod Wells and Royal Tunbridge Wells.[31]

Eratosthenes is sometimes claimed to have used a well in his calculation of the Earth's circumference; however, this is just a simplification used in a shorter explanation of Cleomedes, since Eratosthenes had used a more elaborate and precise method.[32]

Many incidents in the Bible take place around wells, such as the finding of a wife for Isaac in Genesis and Jesus's talk with the Samaritan woman in the Gospels.[33]

For a well with impermeable walls, the water in the well is resupplied from the bottom of the well. The rate at which water flows into the well will depend on the pressure difference between the ground water at the well bottom and the well water at the well bottom. The pressure of a column of water of height z will be equal to the weight of the water in the column divided by the cross-sectional area of the column, so the pressure of the ground water a distance zT below the top of the water table will be:

where ρ is the mass density of the water and g is the acceleration due to gravity. When the water in the well is below the water table level, the pressure at the bottom of the well due to the water in the well will be less than Pg and water will be forced into the well. Referring to the diagram, if z is the distance from the bottom of the well to the well water level and zT is the distance from the bottom of the well to the top of the water table, the pressure difference will be:

Applying Darcy's Law, the volume rate (F) at which water is forced into the well will be proportional to this pressure difference:

where R is the resistance to the flow, which depends on the well cross section, the pressure gradient at the bottom of the well, and the characteristics of the substrate at the well bottom. (e.g., porosity). The volume flow rate into the well can be written as a function of the rate of change of the well water level:

Combining the above three equations yields a simple differential equation in z:

which may be solved:

where z0 is the well water level at time t=0 and τ is the well time constant:

Note that if dz/dt for a depleted well can be measured, it will be equal to and the time constant τ can be calculated. According to the above model, it will take an infinite amount of time for a well to fully recover, but if we consider a well that is 99% recovered to be "practically" recovered, the time for a well to practically recover from a level at z will be:

For a well that is fully depleted (z=0) it would take a time of about 4.6 τ to practically recover.

The above model does not take into account the depletion of the aquifer due to the pumping which lowered the well water level (See aquifer test and groundwater flow equation). Also, practical wells may have impermeable walls only up to, but not including the bedrock, which will give a larger surface area for water to enter the well.[34][35]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)