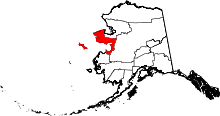

The Inupiat[2] (singular: Iñupiaq[3]) are a group of Alaska Natives whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States border.[4][5][6][7] Their current communities include 34 villages across Iñupiat Nunaat (Iñupiaq lands), including seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation.[8] They often claim to be the first people of the Kauwerak.[9]

Inupiat (IPA: [iɲupiɐt]) is the plural form of the name for the people (e.g., the Inupiat live in several communities.). The singular form is Iñupiaq (IPA: [iɲupiɑq]) (e.g., She is an Iñupiaq), which also sometimes refers to the language (e.g., She speaks Iñupiaq).[2] In English, both Inupiat and Iñupiaq are used as modifiers (e.g., An Inupiat/Iñupiaq librarian, Inupiat/Iñupiaq songs).[10] The language is called Inupiatun in Inupiatun and frequently in English as well. Iñupiak (IPA: [iɲupiɐk]) is the dual form.

The roots are iñuk "person" and -piaq "real", i.e., an endonym meaning "real people".[11][12]

The Inupiat are made up of the following communities

In 1971, the Alaskan Native Claims Settlement Act established thirteen Alaskan Native Regional Corporations. The purpose of the regional corporations were to create institutions in which Native Alaskans would generate venues to provide services for its members, who were incorporated as "shareholders".[15] Three regional corporations are located in the lands of the Inupiat. These are the following.

Prior to colonization, the Inupiat exercised sovereignty based on complex social structures and order. Despite the transfer of land from Russia to the U.S. and eventual annexation of Alaska, Inupiat sovereignty continues to be articulated in various ways. A limited form of this sovereignty has been recognized by Federal Indian Law, which outlines the relationship between the federal government and American Indians. The Federal Indian Law recognized Tribal governments as having limited self-determination. In 1993, the federal government extended federal recognition to Alaskan Natives tribes.[16] Tribal governments created avenues for tribes to contract with the federal government to manage programs that directly benefit Native peoples.[16] Throughout Inupiat lands, there are various regional and village tribal governments. The tribal governments vary in structure and services provided, but often are related to the social well-being of the communities. Services included but are not limited to education, housing, tribal services, and supporting healthy families and cultural connection to place and community.

The following Alaska Native tribal entities for the Inupiat are recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs:

Inuit, the language and the people, extend borders and dialects across the Circumpolar North. Inuit are the Native inhabitants of Northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Inuit languages have differing names depending on the region it is spoken in. In Northern Alaskan, the Inuit language is called Iñupiatun.[17] Within Iñupiatun, there are four major dialects: North Slope, Malimiut, Bering Straits, and Qawiaraq.[17] Before European contact, the Iñupiaq dialects flourished. Due to harsh assimilation efforts in Native American boarding schools, Natives were punished for speaking their language.[8][16] Now only 2,000 of the approximately 24,500 Inupiat can speak their Native tongue.[17]

Revitalization efforts have focused on Alaskan Native languages and ways of life. Located in Kotzebue, Alaska, an Iñupiaq language immersion school called Nikaitchuat Iḷisaġviat was established in 1998. The immersion school's mission is to "instill the knowledge of Iñupiaq identity, dignity, respect and to cultivate a love of lifelong learning".[18] June Nelson Elementary school is another school in Kotzebue that is working to include more content into their curriculum about Iñupiaq language and culture.[19] Nome Elementary School in Nome, Alaska has also put in place plans to incororate an Iñupiaq language immersion program.[20] There are many courses being offered at the various campuses a part of the University of Alaska system. University of Alaska Fairbanks offers several course in the Iñupiaq language. University of Alaska Anchorage offers multiple levels of Elementary Iñupiaq Language and Alaskan Native language apprenticeship and fluency intensive courses.[21]

Since 2017, a grassroots group of Iñupiaq language learners have organized Iḷisaqativut, a two-week Iñupiaq language intensive that is held throughout communities in the Inupiaq region.[22] The first gathering was held in Utqiaġvik in 2017, Siqnasuaq (Nome) in 2018, and Qikiqtaġruk (Kotzebue) in 2019.[23]

Kawerak, a nonprofit organization from the Bering Strait region, has created a language glossary that features terms from Iñupiaq, as well as terms from English, Yup'ik, and St. Lawrence Island Yupik.[24]

Several Inupiat developed pictographic writing systems in the early twentieth century. It is known as Alaskan Picture Writing.[8]

Along with other Inuit groups, the Iñupiaq originate from the Thule culture. Circa 300 B.C., the Thule migrated from islands in the Bering Sea to what now is Alaska.

Iñupiaq groups, in common with Inuit-speaking groups, often have a name ending in "miut," which means 'a people of'. One example is the Nunamiut, a generic term for inland Iñupiaq caribou hunters. During a period of starvation and an influenza epidemic introduced by American and European whaling crews,[25] most of these people moved to the coast or other parts of Alaska between 1890 and 1910. A number of Nunamiut returned to the mountains in the 1930s.

By 1950, most Nunamiut groups, such as the Killikmiut, had coalesced in Anaktuvuk Pass, a village in north-central Alaska. Some of the Nunamiut remained nomadic until the 1950s.

The Iditarod Trail's antecedents were the native trails of the Dena'ina and Deg Hit'an Athabaskan American Indians and the Inupiat.[26]

.jpg/440px-Inupiat_Family_from_Noatak,_Alaska,_1929,_Edward_S._Curtis_(restored).jpg)

Inupiat are hunter-gatherers, as are most Arctic peoples. Inupiat continue to rely heavily on subsistence hunting and fishing. Depending on their location, they harvest walrus, seal, whale, polar bears, caribou, and fish.[13] Both the inland (Nunamiut) and coastal (Tikiġaġmiut) Inupiat depend greatly on fish. Throughout the seasons, when they are available, food staples also include ducks, geese, rabbits, berries, roots, and shoots.

The inland Inupiat also hunt caribou, Dall sheep, grizzly bear, and moose. The coastal Inupiat hunt walrus, seals, beluga whales, and bowhead whales. Cautiously, polar bear also is hunted.

The capture of a whale benefits each member of an Inupiat community, as the animal is butchered and its meat and blubber are allocated according to a traditional formula. Even city-dwelling relatives, thousands of miles away, are entitled to a share of each whale killed by the hunters of their ancestral village. Maktak, which is the skin and blubber of bowhead and other whales, is rich in vitamins A and C.[27][28] The vitamin C content of meats is destroyed by cooking, so consumption of raw meats and these vitamin-rich foods contributes to good health in a population with limited access to fruits and vegetables.

A major value within subsistence hunting is the utilization of the whole catch or animal. This is demonstrated in the utilization of the hides to turn into clothing, as seen with seal skin, moose and caribou hides, polar bear hides. Fur from rabbits, beaver, marten, otter, and squirrels are also utilized to adorn clothing for warmth. These hides and furs are used to make parkas, mukluks, hats, gloves, and slippers. Qiviut is also gathered as Muskox shed their underlayer of fur and it is spun into wool to make scarves, hats, and gloves. The use of the animal's hides and fur have kept Inupiat warm throughout the harsh conditions of their homelands, as many of the materials provide natural waterproof or windproof qualities. Other animal parts that have been utilized are the walrus intestines that are made into dance drums and qayaq or umiaq, traditional skin boats.

The walrus tusks of ivory and the baleen of bowhead whales are also utilized as Native expressions of art or tools. The use of these sensitive materials are inline with the practice of utilizing the gifts from the animals that are subsisted. There are protective policies on the harvesting of walrus and whales.[29] The harvest of walrus solely for the use of ivory is highly looked down upon as well as prohibited by federal law with lengthy and costly punishments.

Since the 1970s, oil and other resources have been an important revenue source for the Inupiat. The Alaska Pipeline connects the Prudhoe Bay wells with the port of Valdez in south-central Alaska. Because of the oil drilling in Alaska's arid north, however, the traditional way of whaling is coming into conflict with one of the modern world's most pressing demands: finding more oil.[30]

The Inupiat eat a variety of berries and when mixed with tallow, make a traditional dessert. They also mix the berries with rosehips and highbush cranberries and boil them into a syrup.[31]

Historically, some Inupiat lived in sedentary communities, while others were nomadic. Some villages in the area have been occupied by Indigenous groups for more than 10,000 years.

The Nalukataq is a spring whaling festival among Inupiat. The festival celebrates traditional whale hunting and honors the whale's spirit as it gave its physical body to feed entire villages. The whale's spirit is honored by dance groups from across the North performing songs and dances.

The Iñupiat Ilitqusiat is a list of values that define Inupiat. It was created by elders in Kotzebue, Alaska,[32] yet the values resonate with and have been articulated similarly by other Iñupiat communities.[33][34] These values include: respect for elders, hard work, hunter's success, family roles, humor, respect for nature, knowledge of family tree, respect for others, sharing, love for children, cooperation, avoid conflict, responsibility to tribe, humility, and spirituality.[32]

These values serve as guideposts of how Inupiat are to live their lives. They inform and can be derived from Iñupiaq subsistence practices.

There is one Iñupiaq culture-oriented institute of higher education, Iḷisaġvik College, located in Utqiaġvik.

Inupiat have grown more concerned in recent years that climate change is threatening their traditional lifestyle. The warming trend in the Arctic affects their lifestyle in numerous ways, for example: thinning sea ice[35] makes it more difficult to harvest bowhead whales, seals, walrus, and other traditional foods as it changes the migration patterns of marine mammals that rely on iceflows and the thinning sea ice can result in people falling through the ice; warmer winters make travel more dangerous and less predictable as more storms form; later-forming sea ice contributes to increased flooding and erosion along the coast as there is an increase in fall storms, directly imperiling many coastal villages.[36] The Inuit Circumpolar Council, a group representing indigenous peoples of the Arctic, has made the case that climate change represents a threat to their human rights.[37]

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, the Inupiat population in the United States numbered more than 19,000.[citation needed] Most of them live in Alaska.

The North Slope Borough has the following cities Anaktuvuk Pass (Anaqtuuvak, Naqsraq), Atqasuk (Atqasuk), Utqiaġvik (Utqiaġvik, Ukpiaġvik), Kaktovik (Qaaktuġvik), Nuiqsut (Nuiqsat), Point Hope (Tikiġaq), Point Lay (Kali), Wainwright (Ulġuniq)

The Northwest Arctic Borough has the following cities Ambler (Ivisaappaat), Buckland (Nunatchiaq, Kaŋiq), Deering (Ipnatchiaq), Kiana (Katyaak, Katyaaq), Kivalina (Kivalliñiq), Kobuk (Laugviik), Kotzebue (Qikiqtaġruk), Noatak (Nuataaq ), Noorvik (Nuurvik), Selawik (Siilvik, Akuligaq ), Shungnak (Isiŋnaq, Nuurviuraq)

The Nome Census Area has the following cities Brevig Mission (Sitaisaq, Sinauraq), Diomede (Iŋalik), Golovin (Siŋik), Koyuk (Kuuyuk), Nome (Siqnazuaq, Sitŋasuaq), Shaktoolik (Saqtuliq), Shishmaref (Qigiqtaq), Teller (Tala, Iġaluŋniaġvik), Wales (Kiŋigin), White Mountain (Natchirsvik), Unalakleet (Uŋalaqłiq)