.jpg/440px-Catedrala_Sfântul_Iosif_din_București_(2023-04).jpg)

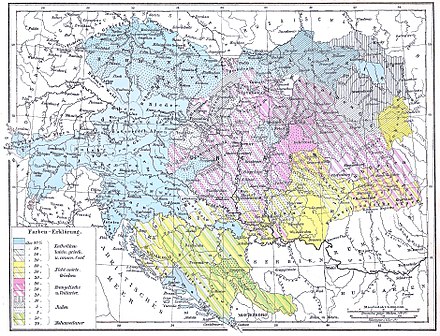

Romanian Catholics, like Catholics elsewhere, are members of the Catholic Church under the spiritual leadership of the Pope and Curia in Rome. The administration for the local Latin Church is centered in Bucharest, and comprises two archdioceses and four other dioceses. It is the second largest Romanian denomination after the Romanian Orthodox Church, and one of the 18 state-recognized religions. As of 2021[update], 5.2% of Romanians identified as Catholic.[1] The 2012 census indicated that there were 741,276 Romanian citizens adhering to the Latin Church (3.89% of the population). Of these, the largest groups were Hungarians (54.7% or 405,212, including Székely and Csángó), Romanians (38.2% or 283,092), Germans (1.7% or 12,495) and Slovaks (0.9% or 6,853).[2]

Most Romanian Latin Catholics inhabit the region of Transylvania and Bacău County in Moldavia.[3] Smaller Latin Catholic communities exist among Banat Bulgarians, Italian-Romanians, Polish-Romanians, Croat-Romanians and Krashovani, Czech-Romanians and the local Romani people.[4]

The Romanian Church United with Rome, Greek-Catholic is an Eastern Catholic sui iuris church which uses the Byzantine Rite. It has separate jurisdictions, five eparchies, and one archeparchy headed by a major archbishop (thus the church has its own synod), and has historically been strongest in Transylvania. The majority of its members are Romanians, with groups of Ukrainians from northern Romania.[4] Members of the Armenian community who belong to the Armenian Catholic Church are organized in the Latin Church-led Ordinariate for Catholics of Armenian Rite in Romania. The Armenian Rite as used by its largely Transylvanian membership was significantly hybridized into the 20th century.[5][6]

The Archdiocese of Bucharest is the metropolitan see for the entire country's Latin jurisdiction, directly overseeing the regions of Muntenia, Northern Dobruja and Oltenia; it has around 52,000 parishioners, most of them Romanians.[7] The other diocese of its rank, the Archdiocese of Alba Iulia (in Alba Iulia), groups the region of Transylvania-proper (without Maramureș and Crișana), and has around 480,000 mostly Hungarian parishioners.[8] Four other dioceses function in Romania and are based, respectively, in Timișoara (the Diocese of Timișoara, representing the Banat), Oradea (the Diocese of Oradea, for Crișana), Satu Mare (the Diocese of Satu Mare, for Maramureș), and Iași (the Diocese of Iași, for Moldavia).[2]

The church presently runs a faculty of theology (as part of the Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca), four theological institutes, six medical schools and sixteen seminaries (see Religious education in Romania).[2] Among the journals issued by Catholic institutions are the Romanian-language Actualitatea Creștină (Bucharest) and Lumina Creștinului (Iași), as well as the Hungarian-language Keresztény Szó and Vasárnap (both in Cluj-Napoca).[2] It leads a network of charitable organizations and other social ventures, administrated by its Caritas foundation or the religious institutes; it includes kindergartens, orphanages, social canteens, medical facilities.[2]

.JPG/440px-Baia_(catedrala).JPG)

The oldest traces of Catholic activities on present-day Romanian territory were recorded in Transylvania, in connection to the extension of Magyar rule and the region's integration into the Kingdom of Hungary (see History of Transylvania). Inaugurated by the early presence of Benedictines, these were strengthened by the colonization of Transylvanian Saxons,[2] as well as by missionary activities among the local Vlach (Romanian) population[2] and forceful conversions.[11] The Diocese of Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) was probably set up in the 11th century.[8][12][13] Tradition holds that this was done under supervision from King Stephen I — according to the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913, a more likely patron is Ladislaus I, who ruled almost a century after (the first bishop it lists is Simon, who held the see between 1103 and 1113).[12]

Other dioceses were created in Cenad (Csanád) and Oradea (Nagyvárad).[2][13] They were subordinated to the Archbishop of Kalocsa, part of the Catholic Church in Hungary.[13] The northern area comprised in the comitatus of Máramaros was originally part of the Alba Iulia Diocese, while the southern one, Szeben, was a provostship not comprised in any bishopric (and thus exempt).[12]

During the rule of Béla IV, the Catholic hierarchy was disestablished by the Mongol incursion (see Battle of Mohi), and only recovered after 1300.[12] In 1304, Pope Boniface VIII sent the first Catholic missionaries from Transylvania into the lands over the Carpathian Mountains (the area known as "Cumania"), where Eastern Orthodox bishops were already present.[14] A Diocese of Cumania was created on the Milcov, in areas later ruled by Moldavia and Wallachia. Its assets were granted by the Hungarian rulers, whose claimed suzerainty over the region,[15] and it extended over parts of Székely Land.[12]

The Diocese of Cumania disappeared for a while, as locals took over its property, but was revived in 1332–1334, when Pope John XXII appointed the Franciscan Vitus de Monteferro, the chaplain of King Charles Robert, as the new bishop.[15] Direct control over the congregation was made difficult by the intrusion of the Golden Horde, who had set up its base in the region later known as Budjak (present-day southern Ukraine).[15] Around 1318, the Dobrujan town of Vicina was part of the Catholic vicariate of "Northern Tartary".[14]

During the 14th century, in the years following the establishment of Moldavia and Wallachia as separate states (the Danubian Principalities), Catholic clerics arriving mainly from Jagiellon Poland and Transylvania set up the first Catholic congregations over the Carpathians.[2]

In both countries, as a result of stately emancipation and lingering conflicts with the Hungarian Kingdom, the relatively strong Catholic presence receded with the establishment of more powerful Eastern Orthodox institutions (the Hungro-Wallachian diocese and the Moldavian diocese).[2][16] Nevertheless, Catholics remained an important presence in both areas.[2] As a result of fighting between Wallachia's Prince Vladislav I Vlaicu and Hungarian King Louis I, concessions were made by both sides, and Wallachia agreed to tolerate a Catholic bishopric (1368).[17] The following year, Wallachia resumed its anti-Catholic policies.[18] In Moldavia, Prince Lațcu began negotiations with Pope Urban V and agreed to convert to Catholicism (1369); following a period of trouble, this political choice was to be overturned by Petru I during the 1380s.[18] New sees were created in that country: in 1371, the one in Siret, and, under the rule of Alexandru cel Bun, the short-lived one of Baia (1405–1413).[2][19][20]

Over the following centuries, the citadel of Cotnari was home to a notable Catholic community, initially comprising local Hungarians and Germans. In Wallachia, a short-lived Catholic diocese was created during the reign of Radu I, around the main town of Curtea de Argeș (1381).[21] The Moldavian diocese of Siret survived through the early stage of war with the Ottoman Empire, but was ultimately disestablished during the early 15th century, when it moved to Bacău.[19] In 1497, that location was abandoned by the hierarchy, and was no longer active during the following century.[19] Until the mid-19th century, like all other religious minorities, Catholics did not enjoy full political and civil rights.[22]

Following the 1526 Battle of Mohács, during which the Ottomans conquered much of Hungary, leaving Transylvania under the rule of local Princes (see Ottoman Hungary), Roman Catholicism entered a period of regression, and was later confronted with the success of Reformation.[2] The first community to embrace a Protestant creed were the Transylvanian Saxons, most of whom adhered to the Lutheran Augsburg Confession as early as 1547,[3][12] followed soon after by large groups of the Hungarian population, who converted to Calvinism.[3] The provostship of Szeben ceased to exist entirely.[12] Catholicism attempted to reestablish itself as George Martinuzzi, a Catholic cleric, took over rule of Transylvania, but again declined after Martinuzzi was assassinated in 1551.[12]

Religious disputes and battles prolonged themselves over the following centuries, as a large number of Latin Catholic communities founded specifically Protestant local churches — the Reformed Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Evangelical Church of Augustan Confession — while others adhered to the Unitarian Church of Transylvania.[2][3][23] The Diocese of Alba Iulia was disestablished in 1556.[12]

An unprecedented stalemate was reached in 1568, under John II Sigismund Zápolya, when the Edict of Torda sanctioned freedom of religion and awarded legal status to the Latin Catholic, Reformed, Lutheran and Unitarian churches alike (while viewing the majority Orthodox as "tolerated").[3] The Alba Iulia see was revived soon after the Catholic Stefan Batory took the Transylvanian throne in succession to Zápolya (who had since become King of Hungary).[12]

During that age, Latin Catholics were recognized an autonomous structure, which allowed clerics and laity to organize teaching and administrate community schools.[12] A particular compromise was the Saxon citadel of Biertan (Birthälm), where the fortified church was taken over by the majority Lutheran community, and Catholic worship was still allowed to take place in the "Catholic Tower", located just south of the religious building.[24]

The Counter-Reformation itself had an impact, with members of the Jesuit religious order being called into the region as early as 1579 (under the rule of Stefan Batory).[25] In 1581, they founded an educational university in Cluj (Kolozsvár), nucleus of the present-day Babeș-Bolyai University.[25] Originally protected by the powerful Báthorys, they continued to have a precarious status in Transylvania.[12] Expelled in 1588-1595 (when Calvinism became official), and again in 1610-1615 (following the pressures of Gabriel Báthori), they continued their activities in the Moldavian region around Cotnari.[25]

Coinciding with the Habsburg offensives, religious conflicts were resumed and, in 1601 Bishop Demeter Napragy was forced out of Alba Iulia, with the see being confiscated by Protestants (although bishops continued to be appointed, they resided abroad).[12] By 1690, Roman Catholics were a minority in Transylvania.[23]

In parallel, Hungary-proper was integrated into Habsburg domains (1622), which created a new base for Counter-Reformation, as well as a local seat for the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide.[23] In Moldavia, Catholicism was reasserted among the Csángós before around 1590, when Franciscan friars took charge of the diocese reestablished in Bacău (1611)[19] and first led by Bernardino Quirini.[26] After 1644, more Jesuits from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth settled in that country, founding a college in Cotnari and establishing a branch in Iași.[25]

Around that time, the ethnic Romanian Transylvanian intellectual Gheorghe Buitul joined the Jesuit order, the first member of his community to study in the Roman College of Rome, while the Transylvanian-born Stephen Pongracz was one of the Jesuits executed by Calvinists in Royal Hungary (1619).[25] The order was expelled a third time from Transylvania (1652), on orders from George II Rákóczi, and was twice driven out of Moldavia by the Great Turkish War (1672, 1683).[25]

During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Catholic Church sought to obtain the adherence of non-Catholic Christians to the Eastern Catholic Churches. They were assisted in this effort by the Habsburg offensive into Eastern Europe, which brought about Emperor Leopold I's conquest of Transylvania in 1699.[2][23] An additional factor for the new Catholic successes was, arguably, the continuous fighting between the various Protestant denominations of Transylvania.[3]

In 1657, Armenians in Transylvania who belonged to the Armenian Apostolic Church and were led by Bishop Oxendius Vărzărescu, placed themselves under indirect Roman Catholic jurisdiction, as part of the Armenian Catholic Church.[27] Michael I Apafi, a Transylvanian prince, allowed the resettling of 600 Armenian families from Moldavia in 1672, elevating 55 of the families to nobility. The Armenians–which included a Catholic contingent–created trading towns, with Gherla (Armenopolis or Szamosújvár) the most prominent.[28][27] Some Transylvania Romanian Orthodox would join with Rome in 1698.[29]

Under the rule of Emperor Charles VI, the Bishops of Alba Iulia were able to return to their restored domains, as the see was removed from Protestant rule (1713).[12] The diocese was completely restored in 1771, under Empress Maria Theresia.[12] The defunct provostship of Szeben was not revived, and its assets went instead to the main diocese.[12] It was also under Maria Theresia that Catholic teaching and school administration came under the supervision of the Commissio catholica (this remained the rule under the Austrian Empire and the early years of Austria-Hungary).[12]

In 1700, with Jesuit assistance, the Romanian Greek Catholic Church was established for formerly Eastern Orthodox Romanians within the Catholic Church. Its leadership was supervised by Jesuit theologians, whose office ensured doctrinal conformity.[25] The Jesuits were also allowed back into Moldavia by 1699, under the rule of Prince Antioh Cantemir.[25] In 1773, the order was suppressed throughout Europe, before being again created by Pope Pius VII in 1814 (see Suppression of the Society of Jesus).[25] Pope Pius IX reorganized the local Greek-Catholic Church in 1853, and placed it under Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide jurisdiction[30] (between 1912 and 1919, the Greek-Catholic parishes were administered from Hajdúdorog).[31]

Romanian Greek Catholic autonomy was challenged by the Diocese of Ardeal's Latin bishop in 1721. The Latin bishop, invoking the Fourth Lateran Council, asserted that the Romanian Greek Catholic clergy were subordinate to him. The Latin bishop also claimed that Romanian Greek Catholic bishop Ioan Giurgiu Patachi was in fact his "ritual vicar" for the Byzantine Rite community. Pope Innocent XIII intervened, asserting Patachi's ordinary authority over Romanian Greek Catholics but moving Patachi's see to Făgăraș.[32]

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Moldavia and Wallachia were awarded their own apostolic vicariates, based respectively in Iași and Bucharest.[2][19][30] The old Moldavian see of Bacău was itself abolished as a result.[19] The Wallachian one was subordinated to the Bishop of Nikopol (later, of Rousse) for the following century.[33] In 1792–1793, Bishop Paulus Davanlia left Rousse to live with the Franciscans in Bucharest (who had set up an important center at the Bărăția).[34]

In addition to the local presence, the Danubian Principalities became home to communities of Catholic diasporas: in Bucharest, Ragusan traders were first mentioned Bucharest during the 16th century, followed, around 1630, by Italian stonemasons;[35] later, the Wallachian capital was settled by groups of Hungarians, Poles (a presence notable after the 1863 January Uprising forced many to take refuge in Romania), and French people (see History of Bucharest).[36]

In 1812, the Franciscan Bulgarian Catholic Bishop of Chiprovtsi decided, as a result of an epidemic in the city, to move his seat to the village of Cioplea (presently part of Bucharest).[33] The locality was a new center for the Bulgarian community in Wallachia,[33] but opposition from the local Eastern Orthodox hierarchy allowed the move to be completed only after 1847.[34] Following the end of the Crimean War, the Danubian Principalities came under the supervision of several European powers, ending Russian tutelage and its Regulamentul Organic administration. The two countries were instead awarded ad hoc Divans. On November 11, 1857, on Costache Negri's proposal, Moldavia's Divan regulated an end to religious discrimination against non-Eastern Orthodox Christians, a measure which mostly benefited the resident Latin Catholics and Armenian Apostolic Christians.[22]

Following the Moldo-Wallachian union of 1859, and the 1881 creation of the Kingdom of Romania, the seat in Bucharest became an archdiocese (April 7, 1883) and the one in Iași a diocese, replacing the Franciscan-led diocese of Bacău (June 27, 1884).[2][26][30] This came as a consequence of repeated protests from locals, who called for Romanian clerics not to be under the strict control of foreign bishops.[34] Upgrading the local ecclesiastical hierarchy, the move also led to the disestablishment of the Cioplea bishopric.[33] The first Archbishop of Bucharest was Ignazio Paoli.[34]

The Neogothic Saint Joseph Cathedral in Bucharest was also completed in 1884,[34] and two seminaries were set up (the main seminary was in Bucharest,[34] and the Iași-based one was a Jesuit institution created in 1886, notably led by the Polish priest Feliks Wierciński).[25] The Jesuit Mission in Romania was created in 1918, being subordinated to the Order's Province of Belgium, and then to the Southern Province of Poland; it became a Vice-Province in 1927.[25] Romania accommodated various Catholic organizations, including the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools (who operated three Bucharest schools by 1913), the Sisters of Mercy, the Passionists, and the Congregation of Notre-Dame de Sion.[34] Despite this increase in importance, Romania and the Holy See did not formally establish diplomatic relations for several decades.[30] The authorities also refused to allow the Church to create its own college.[34]

In parallel, autonomy for Latin Catholic school administration in Austro-Hungarian Transylvania was recovered in 1873, through the creation of a "Roman-Catholic Status".[12] Among the Romanian Greek Catholics, the blanket policy of granting annulments for marriages involving adultery was suppressed during the 19th century. This practice, typical to the Romanian Orthodox, was considered an "abuse" by the Catholic Church.[32]

During the final years of World War I and the stages leading up to Transylvania's union with Romania, Catholicism in Romania met with several diplomatic problems. Romania was defeated by the Central Powers and signed the Treaty of Bucharest, but its diplomats remained active in Allied countries, setting up the National Romanian Council in Paris. The latter, which also represented Romanian groups in the Austro-Hungarian-ruled Transylvania and Bukovina, appointed Monsignor Vladimir Ghika as its representative in Vatican City.[37]

During the interwar years, Romanian national identity was molded to emphasize the Romanian Orthodox Church at the exclusion of other religious groups including Latin and Greek Catholics and Protestants. Trăirism, an anti-Western Romanian political theory led by Nae Ionescu, associated Catholics with a "fundamentally different mode of existence" than true Romanian-ness. For the Romanian Orthodox Church, the Romanian Greek Catholics in particular had been rivals since the Habsburg uniatism conversion efforts in 18th-century Transylvania. Memories of the Austro-Hungarian Catholic monarchy and its limitations on Romanian Orthodoxy further fomented anti-Catholic sentiment in this period.[38]

When the Paris Peace Conference confirmed the creation of Greater Romania, Catholics of both churches represented 13 to 14% of its population.[30] During the Conference, the Ion I. C. Brătianu cabinet and representatives of Pope Benedict XV established preliminary contacts, a gesture coinciding with the encyclical Pacem, Dei Munus Pulcherrimum (which, in turn, redefined relations between the Holy See and individual states).[31] Negotiations were continued by the Alexandru Vaida-Voevod cabinet, who appointed the Greek-Catholic priest Vasile Lucaciu as its representative, and by that of Alexandru Averescu.[31] Through a decision taken by Foreign Minister Duiliu Zamfirescu, the outgoing Ghika was replaced with Dimitrie Pennescu, who was Romania's first ambassador to the Vatican.[31] The Apostolic Nunciature in Romania was set up as a result of this.[2][31] The first person to hold this office was Archbishop Francesco Marmaggi, who took charge in October 1920.[31] The mix of new Latin Catholic Hungarian and Swabians along with the Romanian Greek Catholic population created ethnic tension with the dominant Romanian Orthodox Christians.[39]

Subsequently, the Latin Catholic presence registered significant successes: new religious institutes, such as the Assumptionists and the Sisters of St. Mary, began their activities on Romanian soil, and the lay Acțiunea Catolică, a Romanian version of the Catholic Action, was set up in 1927.[2] By the end of World War II, there were 25 religious institutes present in the country in 203 monasteries, maintaining 421 religious schools and coordinating various charity ventures.[2] Over the early 1920s, the Holy See and Romania engaged in several diplomatic disputes: in one case, the Catholic Church declared itself dissatisfied by the effects of a land reform carried out in 1920–1921 (as a result of talks, it was occasionally allowed to keep larger estates than the law permitted);[40] in parallel, Romanian authorities were dissatisfied with the activities of certain Latin Catholic prelates in Transylvania and Hungary, whom they suspected of actively supporting Hungarian irredentism (in one of his notes to the Vatican, Pennescu condemned the politically motivated letters addressed by Gyula Glattfelder, the Bishop of Timișoara, to his Hungarian-majority congregation).[41]

A Concordat was negotiated in 1927, being ratified by the Romanian side in 1929[2][42][43] and through the papal bull Solemni conventione on June 5, 1930.[44] On the basis of it, a 1932 agreement assigned the Latin Church all the Transylvanian assets previously administered by the "Roman-Catholic Status".[2] On August 15, 1930, the bishop of Bucharest was appointed metropolitan (the others becoming suffragans).[45]

A redefinition of ecclesiastical administration took place in formerly Austro-Hungarian provinces, corresponding with the new borders of Greater Romania: Latin Catholics in Bukovina became part of the Iași Diocese, and those of Oradea were joined with the Satu Mare Diocese.[45] The Armenians maintained their autonomous structure, with the Latin Church hierarchy overseeing the Ordinariate for Catholics of Armenian Rite in Romania.[45][5][46]

Both the Latin Church and the Romanian Church United with Rome, Greek-Catholic entered a period of persecution and regression after 1948, when the Communist regime, which subscribed to the doctrine of Marxist–Leninist atheism, was established. Early signs of this were present after Soviet authorities, when the Concordat came to be regularly disregarded by the Petru Groza government, partly based on suspicions that the Holy See was attempting to convert the Orthodox population (see Soviet occupation of Romania).[47] In parallel, after 1945, Vladimir Ghika and others led a movement calling for a union between the Latin Catholic and Romanian Orthodox Churches, which caused further suspicions from the new authorities.[47] The Romanian Catholic hierarchies also explicitly refused to let their clergy join the Romanian Communist Party, which singled it out among religious organizations in the country.[47]

In 1946, the Groza cabinet declared Apostolic Nuncio Andrea Cassulo a persona non grata, alleging that he had collaborated with Romania's wartime dictator, Ion Antonescu; he was replaced with Gerald Patrick Aloysius O'Hara, who continued to face accusations that he was spying in favor of the Western Allies.[47] In secrecy, O'Hara continued to consecrate bishops and administrators.[48]

The 1927 Concordat was unilaterally denounced on July 17, 1948[42][47] In December of the same year, the Greek-Catholic Church was disestablished, and its patrimony was passed to the Eastern Orthodox Church.[3][42][49] At least 70 Eastern Orthodox clergy were imprisoned for refusing to take over the seized Romanian Greek Catholic churches.[5] However, the general absorption of the Romanian Greek Catholics' property and clergy into the Romanian Orthodox Church was achieved, serving as perhaps the clearest example of how the Romanian Orthodox Church's cooperation with communist authorities elevated its societal standing.[39] Those Romanian Greek Catholics who left their church generally joined the Romanian Orthodox Church for its inherent Romanian identity. Others joined the Hungarian-majority Latin Church, leaving the Romanian Greek Catholic Church isolated and with only 10 percent of its pre-communist membership.[50]

New state regulations were designed to abolish papal authority over Catholics in Romania, and the Latin Church, although it was one of the sixteen recognized religions, lacked legal standing, as its organizational charter was never approved by the Department of Cults.[2][42][47] Until 1978, the celebration of Catholic Mass in Romanian language outside Bucharest and Moldavia was forbidden by the government.[51] Many foreign clerics, including the Jesuit superiors,[25] were intimidated and ultimately expelled.[47][48] The Apostolic Nunciature was also closed down on government orders in 1950, after O'Hara left the country.[48] By that year, Romania, like all other Eastern Bloc countries, cut off diplomatic contacts with the Holy See.[52] Only two dioceses were allowed (the Bucharest Diocese and the Alba Iulia Diocese),[2][48] while the banned ones continued to function in semi-clandestinity (their new bishops, appointed by the Holy See, were not formally recognized).[2] The Communists unsuccessfully attempted to convince Catholics to organize themselves into a national church, and to cease their contacts with the Holy See.[47]

Many Latin Catholic clerics, alongside their approximately 600 Greek-Catholics counterparts,[42] were held in communist prisons from as early as 1947[47] and throughout the 1950s. Five of the six bishops, including both bishops of the recognized dioceses, Anton Durcovici and Áron Márton, were placed in custody.[48][53] Among Catholic clerics to die in confinement were the bishops Szilárd Bogdánffy and Durcovici, Monsignor Ghika, and the Jesuit priest Cornel Chira.[25] In 1949, 15 religious institutes were banned in Romania, and the rest (including the Franciscans) significantly reduced their activities.[2] A number of local Jesuits were kept in imprisonment or under house arrest at the Franciscan friary in Gherla (a situation which lasted for seven years).[25] The communist repression of against Latin clergy took a less severe form than that against first the Ruthenians of Galicia and then the Romanian Greek Catholics; it was met by resolve among all groups.[5]

In 1962, the Catholic population of Romania was reckoned at around 1.5 million Romanian Greek Catholics (primarily in Transylvania), 1.5 million Latin Catholics of mostly Hungarian and German ethnicity, with the Armenian Catholic population primarily found in the longstanding Transylvanian community.[5] During the relative liberalization of the 1960s, sporadic talks between the Holy See and the Romanian state were carried out over the status of Romanian Greek Catholic possessions, but without any significant result.[3] Romania became a Jesuit Province by 1974 (numbering, at that time, eight priests and five brothers).[25]

The situation normalized soon after the Romanian Revolution of 1989. Links with the Holy See were resumed in May 1990 (Romania was the fourth formerly Eastern Bloc country and first minority Catholic country to allow this, after the majority-Catholic Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia).[52] All six dioceses were recognized by the Romanian state during 1990,[2][49] and the one in Alba Iulia became an archdiocese in 1991.[8] Religious institutes were once again permitted to function,[2] and Jesuit activities were freely resumed following the 1990 visit of Provincial superior Peter Hans Kolvenbach.[25]

Beginning in the 1980s, the Romanian Roman Catholic Church has taken part in several international gatherings to promote ecumenism. These include the meetings in Patmos (1980), Munich (1982), Crete and Bari (1984), Vienna and Freising (1990), and at the Balamand Monastery (1993).[2] In May 1999, Romania was the first majority-Orthodox country to be visited by Pope John Paul II, who was personally welcomed by Teoctist Arăpașu, the Patriarch of All Romania.[49] Problems continued to be faced in the relation with the Orthodox Church, in respect to the status of Greek-Catholic status and property.[2][49]