In astronomy, stellar classification is the classification of stars based on their spectral characteristics. Electromagnetic radiation from the star is analyzed by splitting it with a prism or diffraction grating into a spectrum exhibiting the rainbow of colors interspersed with spectral lines. Each line indicates a particular chemical element or molecule, with the line strength indicating the abundance of that element. The strengths of the different spectral lines vary mainly due to the temperature of the photosphere, although in some cases there are true abundance differences. The spectral class of a star is a short code primarily summarizing the ionization state, giving an objective measure of the photosphere's temperature.

Most stars are currently classified under the Morgan–Keenan (MK) system using the letters O, B, A, F, G, K, and M, a sequence from the hottest (O type) to the coolest (M type). Each letter class is then subdivided using a numeric digit with 0 being hottest and 9 being coolest (e.g., A8, A9, F0, and F1 form a sequence from hotter to cooler). The sequence has been expanded with three classes for other stars that do not fit in the classical system: W, S and C. Some non-stellar objects have also been assigned letters: D for white dwarfs and L, T and Y for Brown dwarfs.

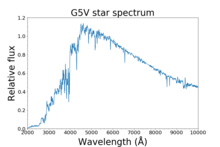

In the MK system, a luminosity class is added to the spectral class using Roman numerals. This is based on the width of certain absorption lines in the star's spectrum, which vary with the density of the atmosphere and so distinguish giant stars from dwarfs. Luminosity class 0 or Ia+ is used for hypergiants, class I for supergiants, class II for bright giants, class III for regular giants, class IV for subgiants, class V for main-sequence stars, class sd (or VI) for subdwarfs, and class D (or VII) for white dwarfs. The full spectral class for the Sun is then G2V, indicating a main-sequence star with a surface temperature around 5,800 K.

The conventional colour description takes into account only the peak of the stellar spectrum. In actuality, however, stars radiate in all parts of the spectrum. Because all spectral colours combined appear white, the actual apparent colours the human eye would observe are far lighter than the conventional colour descriptions would suggest. This characteristic of 'lightness' indicates that the simplified assignment of colours within the spectrum can be misleading. Excluding colour-contrast effects in dim light, in typical viewing conditions there are no green, cyan, indigo, or violet stars. "Yellow" dwarfs such as the Sun are white, "red" dwarfs are a deep shade of yellow/orange, and "brown" dwarfs do not literally appear brown, but hypothetically would appear dim red or grey/black to a nearby observer.

The modern classification system is known as the Morgan–Keenan (MK) classification. Each star is assigned a spectral class (from the older Harvard spectral classification, which did not include luminosity[1]) and a luminosity class using Roman numerals as explained below, forming the star's spectral type.

Other modern stellar classification systems, such as the UBV system, are based on color indices—the measured differences in three or more color magnitudes.[2] Those numbers are given labels such as "U−V" or "B−V", which represent the colors passed by two standard filters (e.g. Ultraviolet, Blue and Visual).

The Harvard system is a one-dimensional classification scheme by astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, who re-ordered and simplified the prior alphabetical system by Draper (see History). Stars are grouped according to their spectral characteristics by single letters of the alphabet, optionally with numeric subdivisions. Main-sequence stars vary in surface temperature from approximately 2,000 to 50,000 K, whereas more-evolved stars can have temperatures above 100,000 K[citation needed]. Physically, the classes indicate the temperature of the star's atmosphere and are normally listed from hottest to coldest.

A common mnemonic for remembering the order of the spectral type letters, from hottest to coolest, is "Oh, Be A Fine Guy/Girl: Kiss Me!", or another one is "Our Bright Astronomers Frequently Generate Killer Mnemonics!" .[11]

The spectral classes O through M, as well as other more specialized classes discussed later, are subdivided by Arabic numerals (0–9), where 0 denotes the hottest stars of a given class. For example, A0 denotes the hottest stars in class A and A9 denotes the coolest ones. Fractional numbers are allowed; for example, the star Mu Normae is classified as O9.7.[12] The Sun is classified as G2.[13]

The fact that the Harvard classification of a star indicated its surface or photospheric temperature (or more precisely, its effective temperature) was not fully understood until after its development, though by the time the first Hertzsprung–Russell diagram was formulated (by 1914), this was generally suspected to be true.[14] In the 1920s, the Indian physicist Meghnad Saha derived a theory of ionization by extending well-known ideas in physical chemistry pertaining to the dissociation of molecules to the ionization of atoms. First he applied it to the solar chromosphere, then to stellar spectra.[15]

Harvard astronomer Cecilia Payne then demonstrated that the O-B-A-F-G-K-M spectral sequence is actually a sequence in temperature.[16] Because the classification sequence predates our understanding that it is a temperature sequence, the placement of a spectrum into a given subtype, such as B3 or A7, depends upon (largely subjective) estimates of the strengths of absorption features in stellar spectra. As a result, these subtypes are not evenly divided into any sort of mathematically representable intervals.

The Yerkes spectral classification, also called the MK, or Morgan-Keenan (alternatively referred to as the MKK, or Morgan-Keenan-Kellman)[17][18] system from the authors' initials, is a system of stellar spectral classification introduced in 1943 by William Wilson Morgan, Philip C. Keenan, and Edith Kellman from Yerkes Observatory.[19] This two-dimensional (temperature and luminosity) classification scheme is based on spectral lines sensitive to stellar temperature and surface gravity, which is related to luminosity (whilst the Harvard classification is based on just surface temperature). Later, in 1953, after some revisions to the list of standard stars and classification criteria, the scheme was named the Morgan–Keenan classification, or MK,[20] which remains in use today.

Denser stars with higher surface gravity exhibit greater pressure broadening of spectral lines. The gravity, and hence the pressure, on the surface of a giant star is much lower than for a dwarf star because the radius of the giant is much greater than a dwarf of similar mass. Therefore, differences in the spectrum can be interpreted as luminosity effects and a luminosity class can be assigned purely from examination of the spectrum.

A number of different luminosity classes are distinguished, as listed in the table below.[21]

Marginal cases are allowed; for example, a star may be either a supergiant or a bright giant, or may be in between the subgiant and main-sequence classifications. In these cases, two special symbols are used:

For example, a star classified as A3-4III/IV would be in between spectral types A3 and A4, while being either a giant star or a subgiant.

Sub-dwarf classes have also been used: VI for sub-dwarfs (stars slightly less luminous than the main sequence).

Nominal luminosity class VII (and sometimes higher numerals) is now rarely used for white dwarf or "hot sub-dwarf" classes, since the temperature-letters of the main sequence and giant stars no longer apply to white dwarfs.

Occasionally, letters a and b are applied to luminosity classes other than supergiants; for example, a giant star slightly less luminous than typical may be given a luminosity class of IIIb, while a luminosity class IIIa indicates a star slightly brighter than a typical giant.[31]

A sample of extreme V stars with strong absorption in He II λ4686 spectral lines have been given the Vz designation. An example star is HD 93129 B.[32]

Additional nomenclature, in the form of lower-case letters, can follow the spectral type to indicate peculiar features of the spectrum.[33]

For example, 59 Cygni is listed as spectral type B1.5Vnne,[40] indicating a spectrum with the general classification B1.5V, as well as very broad absorption lines and certain emission lines.

The reason for the odd arrangement of letters in the Harvard classification is historical, having evolved from the earlier Secchi classes and been progressively modified as understanding improved.

During the 1860s and 1870s, pioneering stellar spectroscopist Angelo Secchi created the Secchi classes in order to classify observed spectra. By 1866, he had developed three classes of stellar spectra, shown in the table below.[41][42][43]

In the late 1890s, this classification began to be superseded by the Harvard classification, which is discussed in the remainder of this article.[44][45][46]

The Roman numerals used for Secchi classes should not be confused with the completely unrelated Roman numerals used for Yerkes luminosity classes and the proposed neutron star classes.

In the 1880s, the astronomer Edward C. Pickering began to make a survey of stellar spectra at the Harvard College Observatory, using the objective-prism method. A first result of this work was the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, published in 1890. Williamina Fleming classified most of the spectra in this catalogue and was credited with classifying over 10,000 featured stars and discovering 10 novae and more than 200 variable stars.[52] With the help of the Harvard computers, especially Williamina Fleming, the first iteration of the Henry Draper catalogue was devised to replace the Roman-numeral scheme established by Angelo Secchi.[53]

The catalogue used a scheme in which the previously used Secchi classes (I to V) were subdivided into more specific classes, given letters from A to P. Also, the letter Q was used for stars not fitting into any other class.[50][51] Fleming worked with Pickering to differentiate 17 different classes based on the intensity of hydrogen spectral lines, which causes variation in the wavelengths emanated from stars and results in variation in color appearance. The spectra in class A tended to produce the strongest hydrogen absorption lines while spectra in class O produced virtually no visible lines. The lettering system displayed the gradual decrease in hydrogen absorption in the spectral classes when moving down the alphabet. This classification system was later modified by Annie Jump Cannon and Antonia Maury to produce the Harvard spectral classification scheme.[52][54]

In 1897, another astronomer at Harvard, Antonia Maury, placed the Orion subtype of Secchi class I ahead of the remainder of Secchi class I, thus placing the modern type B ahead of the modern type A. She was the first to do so, although she did not use lettered spectral types, but rather a series of twenty-two types numbered from I–XXII.[55][56]

Because the 22 Roman numeral groupings did not account for additional variations in spectra, three additional divisions were made to further specify differences: Lowercase letters were added to differentiate relative line appearance in spectra; the lines were defined as:[57]

Antonia Maury published her own stellar classification catalogue in 1897 called "Spectra of Bright Stars Photographed with the 11 inch Draper Telescope as Part of the Henry Draper Memorial", which included 4,800 photographs and Maury's analyses of 681 bright northern stars. This was the first instance in which a woman was credited for an observatory publication.[58]

In 1901, Annie Jump Cannon returned to the lettered types, but dropped all letters except O, B, A, F, G, K, M, and N used in that order, as well as P for planetary nebulae and Q for some peculiar spectra. She also used types such as B5A for stars halfway between types B and A, F2G for stars one fifth of the way from F to G, and so on.[59][60]

Finally, by 1912, Cannon had changed the types B, A, B5A, F2G, etc. to B0, A0, B5, F2, etc.[61][62] This is essentially the modern form of the Harvard classification system. This system was developed through the analysis of spectra on photographic plates, which could convert light emanated from stars into a readable spectrum.[63]

A luminosity classification known as the Mount Wilson system was used to distinguish between stars of different luminosities.[64][65][66] This notation system is still sometimes seen on modern spectra.[67]

The stellar classification system is taxonomic, based on type specimens, similar to classification of species in biology: The categories are defined by one or more standard stars for each category and sub-category, with an associated description of the distinguishing features.[68]

Stars are often referred to as early or late types. "Early" is a synonym for hotter, while "late" is a synonym for cooler.

Depending on the context, "early" and "late" may be absolute or relative terms. "Early" as an absolute term would therefore refer to O or B, and possibly A stars. As a relative reference it relates to stars hotter than others, such as "early K" being perhaps K0, K1, K2 and K3.

"Late" is used in the same way, with an unqualified use of the term indicating stars with spectral types such as K and M, but it can also be used for stars that are cool relative to other stars, as in using "late G" to refer to G7, G8, and G9.

In the relative sense, "early" means a lower Arabic numeral following the class letter, and "late" means a higher number.

This obscure terminology is a hold-over from a late nineteenth century model of stellar evolution, which supposed that stars were powered by gravitational contraction via the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism, which is now known to not apply to main-sequence stars. If that were true, then stars would start their lives as very hot "early-type" stars and then gradually cool down into "late-type" stars. This mechanism provided ages of the Sun that were much smaller than what is observed in the geologic record, and was rendered obsolete by the discovery that stars are powered by nuclear fusion.[69] The terms "early" and "late" were carried over, beyond the demise of the model they were based on.

O-type stars are very hot and extremely luminous, with most of their radiated output in the ultraviolet range. These are the rarest of all main-sequence stars. About 1 in 3,000,000 (0.00003%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are O-type stars.[c][10] Some of the most massive stars lie within this spectral class. O-type stars frequently have complicated surroundings that make measurement of their spectra difficult.

O-type spectra formerly were defined by the ratio of the strength of the He II λ4541 relative to that of He I λ4471, where λ is the radiation wavelength. Spectral type O7 was defined to be the point at which the two intensities are equal, with the He I line weakening towards earlier types. Type O3 was, by definition, the point at which said line disappears altogether, although it can be seen very faintly with modern technology. Due to this, the modern definition uses the ratio of the nitrogen line N IV λ4058 to N III λλ4634-40-42.[70]

O-type stars have dominant lines of absorption and sometimes emission for He II lines, prominent ionized (Si IV, O III, N III, and C III) and neutral helium lines, strengthening from O5 to O9, and prominent hydrogen Balmer lines, although not as strong as in later types. Higher-mass O-type stars do not retain extensive atmospheres due to the extreme velocity of their stellar wind, which may reach 2,000 km/s. Because they are so massive, O-type stars have very hot cores and burn through their hydrogen fuel very quickly, so they are the first stars to leave the main sequence.

When the MKK classification scheme was first described in 1943, the only subtypes of class O used were O5 to O9.5.[71] The MKK scheme was extended to O9.7 in 1971[72] and O4 in 1978,[73] and new classification schemes that add types O2, O3, and O3.5 have subsequently been introduced.[74]

Spectral standards:[68]

B-type stars are very luminous and blue. Their spectra have neutral helium lines, which are most prominent at the B2 subclass, and moderate hydrogen lines. As O- and B-type stars are so energetic, they only live for a relatively short time. Thus, due to the low probability of kinematic interaction during their lifetime, they are unable to stray far from the area in which they formed, apart from runaway stars.

The transition from class O to class B was originally defined to be the point at which the He II λ4541 disappears. However, with modern equipment, the line is still apparent in the early B-type stars. Today for main-sequence stars, the B class is instead defined by the intensity of the He I violet spectrum, with the maximum intensity corresponding to class B2. For supergiants, lines of silicon are used instead; the Si IV λ4089 and Si III λ4552 lines are indicative of early B. At mid-B, the intensity of the latter relative to that of Si II λλ4128-30 is the defining characteristic, while for late B, it is the intensity of Mg II λ4481 relative to that of He I λ4471.[70]

These stars tend to be found in their originating OB associations, which are associated with giant molecular clouds. The Orion OB1 association occupies a large portion of a spiral arm of the Milky Way and contains many of the brighter stars of the constellation Orion. About 1 in 800 (0.125%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are B-type main-sequence stars.[c][10] B-type stars are relatively uncommon and the closest is Regulus, at around 80 light years.[75]

Massive yet non-supergiant stars known as Be stars have been observed to show one or more Balmer lines in emission, with the hydrogen-related electromagnetic radiation series projected out by the stars being of particular interest. Be stars are generally thought to feature unusually strong stellar winds, high surface temperatures, and significant attrition of stellar mass as the objects rotate at a curiously rapid rate.[76]

Objects known as B[e] stars - or B(e) stars for typographic reasons - possess distinctive neutral or low ionisation emission lines that are considered to have forbidden mechanisms, undergoing processes not normally allowed under current understandings of quantum mechanics.

Spectral standards:[68]

A-type stars are among the more common naked eye stars, and are white or bluish-white. They have strong hydrogen lines, at a maximum by A0, and also lines of ionized metals (Fe II, Mg II, Si II) at a maximum at A5. The presence of Ca II lines is notably strengthening by this point. About 1 in 160 (0.625%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are A-type stars,[c][10] which includes 9 stars within 15 parsecs.[77]

Spectral standards:[68]

F-type stars have strengthening spectral lines H and K of Ca II. Neutral metals (Fe I, Cr I) beginning to gain on ionized metal lines by late F. Their spectra are characterized by the weaker hydrogen lines and ionized metals. Their color is white. About 1 in 33 (3.03%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are F-type stars,[c][10] including 1 star Procyon A within 20 ly.[78]

Spectral standards:[68][79][80][81][82]

G-type stars, including the Sun,[13] have prominent spectral lines H and K of Ca II, which are most pronounced at G2. They have even weaker hydrogen lines than F, but along with the ionized metals, they have neutral metals. There is a prominent spike in the G band of CN molecules. Class G main-sequence stars make up about 7.5%, nearly one in thirteen, of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood. There are 21 G-type stars within 10pc.[c][10]

Class G contains the "Yellow Evolutionary Void".[83] Supergiant stars often swing between O or B (blue) and K or M (red). While they do this, they do not stay for long in the unstable yellow supergiant class.

Spectral standards:[68]

K-type stars are orangish stars that are slightly cooler than the Sun. They make up about 12% of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood.[c][10] There are also giant K-type stars, which range from hypergiants like RW Cephei, to giants and supergiants, such as Arcturus, whereas orange dwarfs, like Alpha Centauri B, are main-sequence stars.

They have extremely weak hydrogen lines, if those are present at all, and mostly neutral metals (Mn I, Fe I, Si I). By late K, molecular bands of titanium oxide become present. Mainstream theories (those rooted in lower harmful radioactivity and star longevity) would thus suggest such stars have the optimal chances of heavily evolved life developing on orbiting planets (if such life is directly analogous to Earth's) due to a broad habitable zone yet much lower harmful periods of emission compared to those with the broadest such zones.[84][85]

Spectral standards:[68]

Class M stars are by far the most common. About 76% of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are class M stars.[c][f][10] However, class M main-sequence stars (red dwarfs) have such low luminosities that none are bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye, unless under exceptional conditions. The brightest-known M class main-sequence star is Lacaille 8760, class M0V, with magnitude 6.7 (the limiting magnitude for typical naked-eye visibility under good conditions being typically quoted as 6.5), and it is extremely unlikely that any brighter examples will be found.

Although most class M stars are red dwarfs, most of the largest-known supergiant stars in the Milky Way are class M stars, such as VY Canis Majoris, VV Cephei, Antares, and Betelgeuse. Furthermore, some larger, hotter brown dwarfs are late class M, usually in the range of M6.5 to M9.5.

The spectrum of a class M star contains lines from oxide molecules (in the visible spectrum, especially TiO) and all neutral metals, but absorption lines of hydrogen are usually absent. TiO bands can be strong in class M stars, usually dominating their visible spectrum by about M5. Vanadium(II) oxide bands become present by late M.

Spectral standards:[68]

A number of new spectral types have been taken into use from newly discovered types of stars.[86]

Spectra of some very hot and bluish stars exhibit marked emission lines from carbon or nitrogen, or sometimes oxygen.

Once included as type O stars, the Wolf–Rayet stars of class W[88] or WR are notable for spectra lacking hydrogen lines. Instead their spectra are dominated by broad emission lines of highly ionized helium, nitrogen, carbon, and sometimes oxygen. They are thought to mostly be dying supergiants with their hydrogen layers blown away by stellar winds, thereby directly exposing their hot helium shells. Class WR is further divided into subclasses according to the relative strength of nitrogen and carbon emission lines in their spectra (and outer layers).[39]

WR spectra range is listed below:[89][90]

Although the central stars of most planetary nebulae (CSPNe) show O-type spectra,[91] around 10% are hydrogen-deficient and show WR spectra.[92] These are low-mass stars and to distinguish them from the massive Wolf–Rayet stars, their spectra are enclosed in square brackets: e.g. [WC]. Most of these show [WC] spectra, some [WO], and very rarely [WN].

The slash stars are O-type stars with WN-like lines in their spectra. The name "slash" comes from their printed spectral type having a slash in it (e.g. "Of/WNL")[70]).

There is a secondary group found with these spectra, a cooler, "intermediate" group designated "Ofpe/WN9".[70] These stars have also been referred to as WN10 or WN11, but that has become less popular with the realisation of the evolutionary difference from other Wolf–Rayet stars. Recent discoveries of even rarer stars have extended the range of slash stars as far as O2-3.5If*/WN5-7, which are even hotter than the original "slash" stars.[93]

They are O stars with strong magnetic fields. Designation is Of?p.[70]

The new spectral types L, T, and Y were created to classify infrared spectra of cool stars. This includes both red dwarfs and brown dwarfs that are very faint in the visible spectrum.[94]

Brown dwarfs, stars that do not undergo hydrogen fusion, cool as they age and so progress to later spectral types. Brown dwarfs start their lives with M-type spectra and will cool through the L, T, and Y spectral classes, faster the less massive they are; the highest-mass brown dwarfs cannot have cooled to Y or even T dwarfs within the age of the universe. Because this leads to an unresolvable overlap between spectral types' effective temperature and luminosity for some masses and ages of different L-T-Y types, no distinct temperature or luminosity values can be given.[9]

Class L dwarfs get their designation because they are cooler than M stars and L is the remaining letter alphabetically closest to M. Some of these objects have masses large enough to support hydrogen fusion and are therefore stars, but most are of substellar mass and are therefore brown dwarfs. They are a very dark red in color and brightest in infrared. Their atmosphere is cool enough to allow metal hydrides and alkali metals to be prominent in their spectra.[95][96][97]

Due to low surface gravity in giant stars, TiO- and VO-bearing condensates never form. Thus, L-type stars larger than dwarfs can never form in an isolated environment. However, it may be possible for these L-type supergiants to form through stellar collisions, an example of which is V838 Monocerotis while in the height of its luminous red nova eruption.

Class T dwarfs are cool brown dwarfs with surface temperatures between approximately 550 and 1,300 K (277 and 1,027 °C; 530 and 1,880 °F). Their emission peaks in the infrared. Methane is prominent in their spectra.[95][96]

Study of the number of proplyds (protoplanetary disks, clumps of gas in nebulae from which stars and planetary systems are formed) indicates that the number of stars in the galaxy should be several orders of magnitude higher than what was previously conjectured. It is theorized that these proplyds are in a race with each other. The first one to form will become a protostar, which are very violent objects and will disrupt other proplyds in the vicinity, stripping them of their gas. The victim proplyds will then probably go on to become main-sequence stars or brown dwarfs of the L and T classes, which are quite invisible to us.[98]

Brown dwarfs of spectral class Y are cooler than those of spectral class T and have qualitatively different spectra from them. A total of 17 objects have been placed in class Y as of August 2013.[99] Although such dwarfs have been modelled[100] and detected within forty light-years by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE)[86][101][102][103][104] there is no well-defined spectral sequence yet and no prototypes. Nevertheless, several objects have been proposed as spectral classes Y0, Y1, and Y2.[105]

The spectra of these prospective Y objects display absorption around 1.55 micrometers.[106] Delorme et al. have suggested that this feature is due to absorption from ammonia, and that this should be taken as the indicative feature for the T-Y transition.[106][107] In fact, this ammonia-absorption feature is the main criterion that has been adopted to define this class.[105] However, this feature is difficult to distinguish from absorption by water and methane,[106] and other authors have stated that the assignment of class Y0 is premature.[108]

The latest brown dwarf proposed for the Y spectral type, WISE 1828+2650, is a > Y2 dwarf with an effective temperature originally estimated around 300 K, the temperature of the human body.[101][102][109] Parallax measurements have, however, since shown that its luminosity is inconsistent with it being colder than ~400 K. The coolest Y dwarf currently known is WISE 0855−0714 with an approximate temperature of 250 K, and a mass just seven times that of Jupiter.[110]

The mass range for Y dwarfs is 9–25 Jupiter masses, but young objects might reach below one Jupiter mass (although they cool to become planets), which means that Y class objects straddle the 13 Jupiter mass deuterium-fusion limit that marks the current IAU division between brown dwarfs and planets.[105]

Young brown dwarfs have low surface gravities because they have larger radii and lower masses compared to the field stars of similar spectral type. These sources are marked by a letter beta (β) for intermediate surface gravity and gamma (γ) for low surface gravity. Indication for low surface gravity are weak CaH, KI and NaI lines, as well as strong VO line.[113] Alpha (α) stands for normal surface gravity and is usually dropped. Sometimes an extremely low surface gravity is denoted by a delta (δ).[115] The suffix "pec" stands for peculiar. The peculiar suffix is still used for other features that are unusual and summarizes different properties, indicative of low surface gravity, subdwarfs and unresolved binaries.[116]The prefix sd stands for subdwarf and only includes cool subdwarfs. This prefix indicates a low metallicity and kinematic properties that are more similar to halo stars than to disk stars.[112] Subdwarfs appear bluer than disk objects.[117]The red suffix describes objects with red color, but an older age. This is not interpreted as low surface gravity, but as a high dust content.[114][115] The blue suffix describes objects with blue near-infrared colors that cannot be explained with low metallicity. Some are explained as L+T binaries, others are not binaries, such as 2MASS J11263991−5003550 and are explained with thin and/or large-grained clouds.[115]

Carbon-stars are stars whose spectra indicate production of carbon – a byproduct of triple-alpha helium fusion. With increased carbon abundance, and some parallel s-process heavy element production, the spectra of these stars become increasingly deviant from the usual late spectral classes G, K, and M. Equivalent classes for carbon-rich stars are S and C.

The giants among those stars are presumed to produce this carbon themselves, but some stars in this class are double stars, whose odd atmosphere is suspected of having been transferred from a companion that is now a white dwarf, when the companion was a carbon-star.

.jpg/440px-Curious_spiral_spotted_by_ALMA_around_red_giant_star_R_Sculptoris_(data_visualisation).jpg)

Originally classified as R and N stars, these are also known as carbon stars. These are red giants, near the end of their lives, in which there is an excess of carbon in the atmosphere. The old R and N classes ran parallel to the normal classification system from roughly mid-G to late M. These have more recently been remapped into a unified carbon classifier C with N0 starting at roughly C6. Another subset of cool carbon stars are the C–J-type stars, which are characterized by the strong presence of molecules of 13CN in addition to those of 12CN.[118] A few main-sequence carbon stars are known, but the overwhelming majority of known carbon stars are giants or supergiants. There are several subclasses:

Class S stars form a continuum between class M stars and carbon stars. Those most similar to class M stars have strong ZrO absorption bands analogous to the TiO bands of class M stars, whereas those most similar to carbon stars have strong sodium D lines and weak C2 bands.[119] Class S stars have excess amounts of zirconium and other elements produced by the s-process, and have more similar carbon and oxygen abundances to class M or carbon stars. Like carbon stars, nearly all known class S stars are asymptotic-giant-branch stars.

The spectral type is formed by the letter S and a number between zero and ten. This number corresponds to the temperature of the star and approximately follows the temperature scale used for class M giants. The most common types are S3 to S5. The non-standard designation S10 has only been used for the star Chi Cygni when at an extreme minimum.

The basic classification is usually followed by an abundance indication, following one of several schemes: S2,5; S2/5; S2 Zr4 Ti2; or S2*5. A number following a comma is a scale between 1 and 9 based on the ratio of ZrO and TiO. A number following a slash is a more-recent but less-common scheme designed to represent the ratio of carbon to oxygen on a scale of 1 to 10, where a 0 would be an MS star. Intensities of zirconium and titanium may be indicated explicitly. Also occasionally seen is a number following an asterisk, which represents the strength of the ZrO bands on a scale from 1 to 5.

In between the M and S classes, border cases are named MS stars. In a similar way, border cases between the S and C-N classes are named SC or CS. The sequence M → MS → S → SC → C-N is hypothesized to be a sequence of increased carbon abundance with age for carbon stars in the asymptotic giant branch.

The class D (for Degenerate) is the modern classification used for white dwarfs—low-mass stars that are no longer undergoing nuclear fusion and have shrunk to planetary size, slowly cooling down. Class D is further divided into spectral types DA, DB, DC, DO, DQ, DX, and DZ. The letters are not related to the letters used in the classification of other stars, but instead indicate the composition of the white dwarf's visible outer layer or atmosphere.

The white dwarf types are as follows:[120][121]

The type is followed by a number giving the white dwarf's surface temperature. This number is a rounded form of 50400/Teff, where Teff is the effective surface temperature, measured in kelvins. Originally, this number was rounded to one of the digits 1 through 9, but more recently fractional values have started to be used, as well as values below 1 and above 9.(For example DA1.5 for IK Pegasi B)[120][122]

Two or more of the type letters may be used to indicate a white dwarf that displays more than one of the spectral features above.[120]

A different set of spectral peculiarity symbols are used for white dwarfs than for other types of stars:[120]

Finally, the classes P and Q are left over from the system developed by Cannon for the Henry Draper Catalogue. They are occasionally used for certain non-stellar objects: Type P objects are stars within planetary nebulae (typically young white dwarfs or hydrogen-poor M giants); type Q objects are novae.[citation needed]

Stellar remnants are objects associated with the death of stars. Included in the category are white dwarfs, and as can be seen from the radically different classification scheme for class D, non-stellar objects are difficult to fit into the MK system.

The Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, which the MK system is based on, is observational in nature so these remnants cannot easily be plotted on the diagram, or cannot be placed at all. Old neutron stars are relatively small and cold, and would fall on the far right side of the diagram. Planetary nebulae are dynamic and tend to quickly fade in brightness as the progenitor star transitions to the white dwarf branch. If shown, a planetary nebula would be plotted to the right of the diagram's upper right quadrant. A black hole emits no visible light of its own, and therefore would not appear on the diagram.[123]

A classification system for neutron stars using Roman numerals has been proposed: type I for less massive neutron stars with low cooling rates, type II for more massive neutron stars with higher cooling rates, and a proposed type III for more massive neutron stars (possible exotic star candidates) with higher cooling rates.[124] The more massive a neutron star is, the higher neutrino flux it carries. These neutrinos carry away so much heat energy that after only a few years the temperature of an isolated neutron star falls from the order of billions to only around a million Kelvin. This proposed neutron star classification system is not to be confused with the earlier Secchi spectral classes and the Yerkes luminosity classes.

Several spectral types, all previously used for non-standard stars in the mid-20th century, have been replaced during revisions of the stellar classification system. They may still be found in old editions of star catalogs: R and N have been subsumed into the new C class as C-R and C-N.

While humans may eventually be able to colonize any kind of stellar habitat, this section will address the probability of life arising around other stars.

Stability, luminosity, and lifespan are all factors in stellar habitability. Humans know of only one star that hosts life, the G-class Sun, a star with an abundance of heavy elements and low variability in brightness. The Solar System is also unlike many stellar systems in that it only contains one star (see Habitability of binary star systems).

Working from these constraints and the problems of having an empirical sample set of only one, the range of stars that are predicted to be able to support life is limited by a few factors. Of the main-sequence star types, stars more massive than 1.5 times that of the Sun (spectral types O, B, and A) age too quickly for advanced life to develop (using Earth as a guideline). On the other extreme, dwarfs of less than half the mass of the Sun (spectral type M) are likely to tidally lock planets within their habitable zone, along with other problems (see Habitability of red dwarf systems).[125] While there are many problems facing life on red dwarfs, many astronomers continue to model these systems due to their sheer numbers and longevity.

For these reasons NASA's Kepler Mission is searching for habitable planets at nearby main-sequence stars that are less massive than spectral type A but more massive than type M—making the most probable stars to host life dwarf stars of types F, G, and K.[125]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)