The United Kingdom government austerity programme was a fiscal policy that was adopted for a period in the early 21st century following the era of the Great Recession. Coalition and Conservative governments in office from 2010 to 2019 used the term, and it was applied again by many observers to describe Conservative Party policies from 2021 to 2024, during the cost of living crisis. With the exception of the Truss ministry, the governments in power over the second period did not formally re-adopt the term. The two austerity periods are separated by increased spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first period was one of the most extensive deficit reduction programmes seen in any advanced economy since the Second World War, with emphasis placed on shrinking the state, rather than consolidating fiscally as was more common elsewhere in Europe.[2]

The Conservative-led government claimed that austerity served as a deficit reduction programme consisting of sustained reductions in public spending and tax rises, intended to reduce the government budget deficit and the role of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. Some commentators accepted this claim, but many scholars have observed that in fact, its primary, largely unstated aim, like most austerity policies,[3] was to restore the rate of profit.[4][5] Successive Conservative governments claimed that the National Health Service[6] and education[7] had ostensibly been "ringfenced" and protected from direct spending cuts,[8] but between 2010 and 2019 more than £30 billion in spending reductions were made to welfare payments, housing subsidies, and social services.[9]

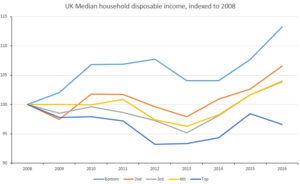

There was no central function or risk assessment made to predict the impact of the austerity programme on services and budgets in the long term. There were however "big strategic moves" to protect groups more likely to vote Conservative, and make cuts elsewhere.[10] This meant that the richest 20% of the population were largely protected, and the 2015 Conservative general election victory is credited to this tactic. During the second austerity period, a wider group than before were affected by the resulting cost-of-living crisis. This was connected to declining support for the Conservatives ahead of the 2024 general election, which resulted in a landslide defeat for the party.[11][12] The Conservatives had planned further measures for after the election, some of which were leaked in advance.[13][14]

The effects proved controversial and the policies received criticism from a variety of politicians, economists, and Anti-austerity movements.[2][15] The British Medical Association nicknamed austerity "COVID's little helper" and connected British excess deaths to the effects of austerity on public services, however no causal link was shown and was assumed based upon life expectancy not rising in the UK at the same rate as other selected countries, excluding the United States which showed equal stagnation in life expectancy.[16]

A UK government budget surplus in 2001-2 was followed by many years of budget deficit,[17] and following the 2007–2008 financial crisis, a period of economic recession began in the country. The first austerity measures were introduced in late 2008.[18] In 2009, the term "age of austerity", which had previously been used to describe the years immediately following the Second World War, was popularised by Conservative Party leader David Cameron and future British chancellor George Osborne. The term at the time lacked the negative associations it would develop over the course of the following decade, and was somewhat synonymous with "prudence".[19] In his keynote speech to the Conservative Party forum in Cheltenham on 26 April 2009, Cameron declared that "the age of irresponsibility is giving way to the age of austerity", and committed to end years of what he characterised as excessive government spending.[20][21][22] Conservative Party leaders also promoted the idea of budget cuts bringing about the Big Society, a political ideology involving reduced government, with grass-roots organisations, charities and private companies delivering public services more efficiently.[9] Osborne has been more dismissive in retrospect, acknowledging that the modernisation programme was simply the party "trying to win".[2]

The austerity programme was initiated in 2010 by the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government. In his June 2010 budget speech, Osborne identified two goals. The first was that the structural current budget deficit would be eliminated to "achieve [a] cyclically-adjusted current balance by the end of the rolling, five-year forecast period". The second was that national debt as a percentage of GDP would fall. The government intended to achieve both of its goals through substantial reductions in public expenditure.[18] This was to be achieved by a combination of public spending cuts and tax increases amounting to £110 billion.[23] Between 2010 and 2013, the Coalition government said that it had reduced public spending by £14.3 billion compared with 2009–10.[24] Growth remained low, while unemployment rose.[23] In a speech in 2013, David Cameron indicated that his government had no intention of increasing public spending once the structural deficit had been eliminated, and proposed that these spending reductions be made permanent.[25] The end of the forecast period at the time was 2015–16, but the Treasury extended austerity until at least 2018.[26] By 2015, the deficit, as a percentage of GDP, had been reduced to half of what it was in 2010, and the sale of government assets (mostly the shares of banks nationalised in the 2000s) had resulted in government debt as a proportion of GDP falling.[18] By 2016, the Chancellor was aiming to deliver a budget surplus by 2020, but following the result of the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, he expressed the opinion that this goal was no longer feasible.[27]

Cuts in spending were not equally applied geographically, leading to some allegations that non-Conservative areas were being systematically targeted. Health expenditure in Blackpool (Labour) fell five times more per person than in Surrey (Conservative). Osborne has denied the cuts were applied in this way, but other Conservative staff members have since acknowledged "big strategic moves" that were made to favour demographic groups more likely to vote Conservative. This meant that the richest 20% of the population were essentially excluded from the impact of cuts. The approach was "devastatingly politically effective" according to Osborne, and is credited with the 2015 election win. British MP David Gauke also stated that this rebalancing had gone too far.[2]

Osborne's successor as Chancellor, Philip Hammond, retained the aim of a balanced budget[28] but abandoned plans to eliminate the deficit by 2020.[29] In Hammond's first Autumn statement in 2016, there was no mention of austerity, and some commentators concluded that the austerity programme had ended.[30][31] However, in February 2017, Hammond proposed departmental budget reductions of up to 6% for the year 2019–20,[24] and Hammond's 2017 budget continued government policies of freezing working-age benefits.[32] Following the 2017 snap general election, Hammond confirmed in a speech at Mansion House that the austerity programme would be continued[33] and Michael Fallon, the Secretary of State for Defence, commented: "we all understand that austerity is never over until we've cleared the deficit".[34] Government spending reductions planned for the period 2017–2020 are consistent with some departments, such as the Department for Work and Pensions and the Ministry of Justice, experiencing funding reductions of approximately 40% in real terms over the decade 2010–2020.[35] During 2017, an overall budget surplus on day-to-day spending was achieved for the first time since 2001. This fulfilled one of the fiscal targets set by George Osborne in 2010, which he had hoped to achieve in 2015.[36]

In 2018 the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicted that in 2018–19, public sector debt would fall as a share of national income for the first time since 2001–02, while tax revenues would exceed public spending. Hammond's 2018 Spring Statement suggested that austerity measures could be reduced in the Autumn Budget of that year. However, according to the Resolution Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), the OBR's forecasts for borrowing and debt were based on the assumption that the government continued with the planned spending reductions that were announced after the 2015 general election. By 2018, only 25% of the proposed reductions in welfare spending had been implemented. The Resolution Foundation, a British think tank, calculated that the proposed reduction in spending on working-age benefits amounted to £2.5 billion in 2018–19 and £2.7 billion in 2019–20, with the households most affected being the poorest 20%. The IFS calculated that the OBR's figures would require spending on public services per person in real terms to be 2% lower in 2022–23 than in 2019–20.[37]

The deficit in the first quarter of the 2018–19 financial year was lower than at any time since 2007[38] and by August 2018 it had reached the lowest level since 2002–3. Hammond's aim at this time was to eliminate the deficit entirely by the mid-2020s.[17] At the Conservative Party conference in October 2018 Prime Minister Theresa May indicated her intention to end the austerity programme following Brexit in 2019,[39] and opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn said that austerity could not be ended without significant increases in public spending.[40] The IFS calculated that funding an end to austerity would require an additional £19 billion per year raised through higher government borrowing or tax increases.[41] Hammond's preference was to reduce the national debt with more years of austerity,[42] but in the October 2018 budget he agreed to defer the target date for eliminating the deficit, abandoning plans to achieve a surplus in 2022–23 to allow an increase in health spending and tax cuts. The Resolution Foundation described the step as a "significant easing of austerity".[43] Hammond said that the "era of austerity is finally coming to an end"[44] but that there would be no "real terms" increase in public spending apart from on the NHS.[45]

The end of austerity was declared by Hammond's successor Sajid Javid in September 2019, though the Institute for Fiscal Studies expressed doubts that the planned spending in the Conservative manifesto for the 2019 election would constitute a true end to austerity, with spending per capita still 9% lower than 2010 levels.[46]

The spending plans were dramatically altered in early 2020, with the following two years characterised by vast spending brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK suffered its deepest recession in 300 years.[47] Government spending jumped from 39.1% of GDP to 51.9%, widening the deficit to a level not seen even during the 2008 financial crisis, and reversing austerity era efforts to balance national finances.[48] The government abandoned efforts to lower the national debt across the lifetime of the 2019 parliament, as had been planned, instead adopting policies, described by Will Hutton in The Guardian as Keynesian, during the pandemic.[49][50] The Eat Out to Help Out scheme in particular has been cited as an example of this.[51]

Beginning during the latter part of the premiership of Boris Johnson, high inflation, high taxation, and the removal of temporary COVID-era support measures culminated in a cost of living crisis. The Johnson ministry embarked on a series of cuts, which continued throughout the Truss and Sunak ministries. Johnson and Sunak avoided using the term austerity, though it was adopted again by the Truss ministry.[52] The period from 2021 onwards is referred to as a "second era" or "second period" of austerity by many observers.[53][54][55]

The Johnson ministry made cuts to Universal Credit in September 2021, and this was described by some as an austerity policy.[56] UK in a Changing Europe described the period as "round two", viewing the Johnson government's 2022 spring statement as a turning point similar to the October 2010 statement then delivered by George Osborne, at the initiation of austerity.[57] This view was shared by The Guardian, which described the period from Spring 2022 onward as "another era",[58] and The Telegraph, which termed it "another ill-judged bout".[59] Johnson announced his resignation that July, amid a Conservative rebellion sparked in part over the cost of living crisis.[60]

Shortly after the beginning of the premiership of Liz Truss in September 2022, the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Simon Clarke announced a "New age of austerity", saying that the country had a "very large welfare state" and that the government would "trim the fat".[61] The scope or detail of these planned cuts were not announced at the time, though by some estimates Truss' tax changes, announced in a mini-budget that September, added 32 billion pounds to an existing 6 billion pound deficit, that would have either required sig