A blood donation occurs when a person voluntarily has blood drawn and used for transfusions and/or made into biopharmaceutical medications by a process called fractionation (separation of whole blood components). Donation may be of whole blood, or of specific components directly (apheresis). Blood banks often participate in the collection process as well as the procedures that follow it.

Today in the developed world, most blood donors are unpaid volunteers who donate blood for a community supply. In some countries, established supplies are limited and donors usually give blood when family or friends need a transfusion (directed donation). Many donors donate for several reasons, such as a form of charity, general awareness regarding the demand for blood, increased confidence in oneself, helping a personal friend or relative, and social pressure. Despite the many reasons that people donate, not enough potential donors actively donate. However, this is reversed during disasters when blood donations increase, often creating an excess supply that will have to be later discarded. In countries that allow paid donation some people are paid, and in some cases there are incentives other than money such as paid time off from work. People can also have blood drawn for their own future use (autologous donation). Donating is relatively safe, but some donors have bruising where the needle is inserted or may feel faint.

Potential donors are evaluated for anything that might make their blood unsafe to use. The screening includes testing for diseases that can be transmitted by a blood transfusion, including HIV and viral hepatitis. The donor must also answer questions about medical history and take a short physical examination to make sure the donation is not hazardous to their health. How often a donor can donate varies from days to months based on what component they donate and the laws of the country where the donation takes place. For example, in the United States, donors must wait 56 days (eight weeks) between whole-blood donations but only seven days between platelet apheresis donations and twice per seven-day period in plasmapheresis.[1]: How often can I donate blood?

The amount of blood drawn and the methods vary. The collection can be done manually or with automated equipment that takes only specific components of the blood. Most of the components of blood used for transfusions have a short shelf life, and maintaining a constant supply is a persistent problem. This has led to some increased interest in autotransfusion, whereby a patient's blood is salvaged during surgery for continuous reinfusion—or alternatively, is self-donated prior to when it will be needed. Generally, the notion of donation does not refer to giving to one's self, though in this context it has become somewhat acceptably idiomatic.

Charles Richard Drew (1904–1950) was an American surgeon and medical researcher. His research was in the field of blood transfusions, developing improved techniques for blood storage, and applied his expert knowledge to developing large-scale blood banks early in World War II. This allowed medics to save thousands of lives of the Allied forces. As the most prominent African American in the field, Drew protested against the practice of racial segregation in the donation of blood, as it lacked scientific foundation, and resigned his position with the American Red Cross, which maintained the policy until 1950.[citation needed]

Blood donations are divided into groups based on who will receive the collected blood.[2] An allogeneic (also called homologous) donation is when a donor gives blood for storage at a blood bank for transfusion to an unknown recipient. A directed donation is when a person, often a family member, donates blood for transfusion to a specific individual.[3] Directed donations are relatively rare when an established supply exists.[4] A replacement donor donation is a hybrid of the two and is common in developing countries.[5] In this case, a friend or family member of the recipient donates blood to replace the stored blood used in a transfusion, ensuring a consistent supply. When a person has blood stored that will be transfused back to the donor at a later date, usually after surgery, that is called an autologous donation.[6] Blood that is used to make medications can be made from allogeneic donations or from donations exclusively used for manufacturing.[7]

Sometimes there are specific reasons for preferring one form or the other. Allogeneic donations have a lower risk of some complications than blood from a family member.[8] Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia may require a transfusion from the mother's own platelets.[8] Autologous (self) donations may be preferred for someone with a rare blood type for a planned surgery.[8]

Blood is sometimes collected using similar methods for therapeutic phlebotomy, similar to the ancient practice of bloodletting, which is used to treat conditions such as hereditary hemochromatosis or polycythemia vera. This blood is sometimes treated as a blood donation, but may be immediately discarded if it cannot be used for transfusion or further manufacturing.[9]

The actual process varies according to the laws of the country, and recommendations to donors vary according to the collecting organization.[10][11][12] The World Health Organization gives recommendations for blood donation policies,[13] but in developing countries many of these are not followed. For example, the recommended testing requires laboratory facilities, trained staff, and specialized reagents, all of which may not be available or too expensive in developing countries.[14]

.jpg/440px-Give_Life_-_Donner_la_vie_(37346943046).jpg)

A blood drive or a blood donor session is an event in which donors come to donate allogeneic blood. These can occur at a blood bank, but they are often set up at a location in the community, such as a shopping center, workplace, school, or house of worship.[15]

Donors are typically required to give consent for the process, and meet a certain criteria such as weight and hemoglobin levels, and this requirement means minors cannot donate without permission from a parent or guardian.[16] In some countries, answers are associated with the donor's blood, but not name, to provide anonymity; in others, such as the United States, names are kept to create lists of ineligible donors.[17] If a potential donor does not meet these criteria, they are 'deferred'. This term is used because many donors who are ineligible may be allowed to donate later. Blood banks in the United States may be required to label the blood if it is from a therapeutic donor, so some do not accept donations from donors with any blood disease.[18] Others, such as the Australian Red Cross Blood Service, accept blood from donors with hemochromatosis. It is a genetic disorder that does not affect the safety of the blood.[19]

The donor's race or ethnic background is sometimes important since certain blood types, especially rare ones, are more common in certain ethnic groups.[20] Historically, in the United States donors were segregated or excluded on race, religion, or ethnicity, but this is no longer a standard practice.[21][22]

Donors are screened for health risks that could make the donation unsafe for the recipient. Some of these restrictions are controversial, such as restricting donations from men who have sex with men (MSM) because of the risk of transmitting HIV.[23] In 2011, the UK (excluding Northern Ireland) reduced its blanket ban on MSM donors to a narrower restriction which only prevents MSM from donating blood if they have had sex with other men within the past year.[24] A similar change was made in the US in late 2015 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[25] In 2017, the UK and US further reduced their restrictions to three months.[26] In 2023, the FDA announced new policies easing restrictions on gay and bisexual men donating blood.[27] These updated guidelines stipulate that men in monogamous relationships with other men, or who have not recently had sex, can donate.[27] Individuals who report having sex with people who are HIV positive or have had sex with a new partner who has engaged in anal sex are still barred from blood donation.[27] Autologous donors are not always screened for recipient safety problems since the donor is the only person who will receive the blood.[28] Since the donated blood may be given to pregnant women or women of child-bearing age, donors taking teratogenic (birth defect-causing) medications are deferred. These medications include acitretin, etretinate, isotretinoin, finasteride, and dutasteride.[29]

Donors are examined for signs and symptoms of diseases that can be transmitted in a blood transfusion, such as HIV, malaria, and viral hepatitis. Screening may include questions about risk factors for various diseases, such as travel to countries at risk for malaria or variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD). These questions vary from country to country. For example, while blood centers in Québec and the rest of Canada, Poland, and many other places defer donors who lived in the United Kingdom for risk of vCJD,[30][31] donors in the United Kingdom are only restricted for vCJD risk if they have had a blood transfusion in the United Kingdom.[32] Australia removed its UK-donor deferral in July 2022.[33]

Directed donations from family members (e.g., a father donating blood to his child) carry extra risks for the recipient.[8] Any blood transfusion carries some risk of a transfusion reaction, but between genetically related family members, there are additional risks.[8] The donated blood must be irradiated to prevent a potentially deadly graft-versus-host disease, which is more likely between genetically related people.[8] Not all healthcare facilities have the equipment to do this on site.[8] Alloimmunization is a particular risk for directed granulocyte donations.[8] It is a common misconception that directed donations are safer for the recipient; however, family members and close friends, especially parents who have not previously donated blood, frequently feel pressured into lying about disqualifying risk factors (e.g., drug use or prior sexual relationships) and their eligibility, which can result in a higher risk of infection with bloodborne pathogens.[8] Additionally, in the less common case of a person with leukemia or other bone marrow disease, a familial blood transfusion can trigger the production of alloantibodies against HLA proteins, which can cause a bone marrow transplant from that donor to fail in the future.[8] (Closely related family members are usually the best match for a bone marrow transplant.[8]) A directed donation from an unrelated friend, however, would not have the same risk.

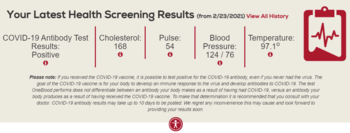

The donor is also examined and asked specific questions about their medical history to make sure that donating blood is not hazardous to their health. The donor's hematocrit or hemoglobin level is tested to make sure that the loss of blood will not make them anemic, and this check is the most common reason that a donor is ineligible.[34] Accepted hemoglobin levels for blood donations, by the American Red Cross, is 12.5g/dL (for females) and 13.0g/dL (for males) to 20.0g/dL, anyone with a higher or lower hemoglobin level cannot donate.[35] Pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature are also evaluated. Elderly donors are sometimes also deferred on age alone because of health concerns.[36] In addition to age, weight and height are important factors when considering the eligibility for donors. For example, the American Red Cross requires a donor to be 110 pounds (50 kg) or more for whole blood and platelet donation and at least 130 pounds (59 kg) (males) and at least 150 pounds (68 kg) (females) for power red donations (double red erythrocytapheresis).[37] The safety of donating blood during pregnancy has not been studied thoroughly, and pregnant women are usually deferred until six weeks after the pregnancy.[38] Donors with aortic stenosis have traditionally been deferred out of concern that the acute volume depletion (475 mL) of blood donation might compromise cardiac output.[39]

The donor's blood type must be determined if the blood will be used for transfusions. The collecting agency usually identifies whether the blood is type A, B, AB, or O and the donor's Rh (D) type and will screen for antibodies to less common antigens. More testing, including a crossmatch, is usually done before a transfusion. Type O negative is often cited as the "universal donor"[40] but this only refers to red cell and whole blood transfusions. For plasma and platelet transfusions the system is reversed: AB positive is the universal platelet donor type while both AB positive and AB negative are universal plasma donor types.[41][42]

Most blood is tested for diseases, including some STDs.[43] The tests used are high-sensitivity screening tests and no actual diagnosis is made. Some of the test results are later found to be false positives using more specific testing.[44] False negatives are rare, but donors are discouraged from using blood donation for the purpose of anonymous STD screening because a false negative could mean a contaminated unit. The blood is usually discarded if these tests are positive, but there are some exceptions, such as autologous donations. The donor is generally notified of the test result.[45]

Donated blood is tested by many methods, but the core tests recommended by the World Health Organization are these four:[46]

The WHO reported in 2006 that 56 out of 124 countries surveyed did not use these basic tests on all blood donations.[14]

A variety of other tests for transfusion transmitted infections are often used based on local requirements. Additional testing is expensive, and in some cases the tests are not implemented because of the cost.[47] These additional tests include other infectious diseases such as West Nile fever[48] and babesiosis.[49] Sometimes multiple tests are used for a single disease to cover the limitations of each test. For example, the HIV antibody test will not detect a recently infected donor, so some blood banks use a p24 antigen or HIV nucleic acid test in addition to the basic antibody test to detect infected donors. Cytomegalovirus is a special case in donor testing in that many donors will test positive for it.[50] The virus is not a hazard to a healthy recipient, but it can harm infants[51] and other recipients with weak immune systems.[50]

Blood testing in the US takes at least 48 hours.[52] Because of the time required for testing, directed donations are not practical in emergencies.[8][52]

There are two main methods of obtaining blood from a donor. The most frequent is to simply take the blood from a vein as whole blood. This blood is typically separated into parts, usually red blood cells and plasma, since most recipients (other than trauma patients) need only a specific component for transfusions.[53]

The amount of blood donated in one session – generally called a 'unit' – is defined by the WHO as 450 millilitres.[54] Some countries like Canada follow this standard,[55] but others have set their own rules, and sometimes there is variation even among different agencies within a country. For example, whole blood donations in the United States are in the 460–500 ml range,[56][57] while those in the EU must be in the 400-500 ml range.[58] Other countries have smaller units – India uses 350 ml,[59] Singapore 350 or 450 ml,[60] and Japan 200 or 400 ml.[61] Historically, donors in the People's Republic of China would donate only 200 ml, though larger 300 and 400 ml donations have become more common, particularly in northern China and for heavier donors.[62] In any case, an additional 5-10 ml of blood may be collected separately for testing.

The other method is to draw blood from the donor, separate it using a centrifuge or a filter, store the desired part, and return the rest to the donor. This process is called apheresis, and it is often done with a machine specifically designed for this purpose. This process is especially common for plasma, platelets, and red blood cells.[63]

For direct transfusions a vein can be used but the blood may be taken from an artery instead.[64] In this case, the blood is not stored, but is pumped directly from the donor into the recipient. This was an early method for blood transfusion and is rarely used in modern practice.