The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. The male and female are similar in plumage and size, reaching 100 cm (39 in) in length and weighing from 22 to 45 kg (49 to 99 lb). Feathers of the head and back are black and sharply delineated from the white belly, pale-yellow breast and bright-yellow ear patches.

Like all species of penguin, the emperor is flightless, with a streamlined body, and wings stiffened and flattened into flippers for a marine habitat. Its diet consists primarily of fish, but also includes crustaceans, such as krill, and cephalopods, such as squid. While hunting, the species can remain submerged around 20 minutes, diving to a depth of 535 m (1,755 ft). It has several adaptations to facilitate this, including an unusually structured haemoglobin to allow it to function at low oxygen levels, solid bones to reduce barotrauma, and the ability to reduce its metabolism and shut down non-essential organ functions.

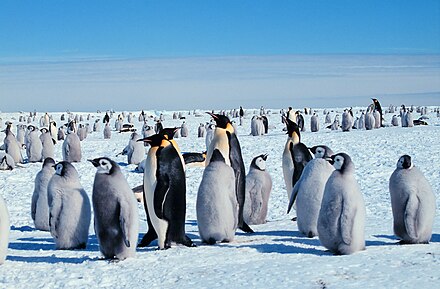

The only penguin species that breeds during the Antarctic winter, emperor penguins trek 50–120 km (31–75 mi) over the ice to breeding colonies which can contain up to several thousand individuals. The female lays a single egg, which is incubated for just over two months by the male while the female returns to the sea to feed; parents subsequently take turns foraging at sea and caring for their chick in the colony. The lifespan of an emperor penguin is typically 20 years in the wild, although observations suggest that some individuals may live as long as 50 years of age.

Emperor penguins were described in 1844 by English zoologist George Robert Gray, who created the generic name from Ancient Greek word elements, ἀ-πτηνο-δύτης [a-ptēno-dytēs], "without-wings-diver". Its specific name is in honour of the German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster, who accompanied Captain James Cook on his second voyage and officially named five other penguin species.[2] Forster may have been the first person to see emperor penguins in 1773–74, when he recorded a sighting of what he believed was the similar king penguin (A. patagonicus) but given the location, may very well have been the emperor penguin (A. forsteri).[3]

Together with the king penguin, the emperor penguin is one of two extant species in the genus Aptenodytes. Fossil evidence of a third species—Ridgen's penguin (A. ridgeni)—has been found in fossil records from the late Pliocene, about three million years ago, in New Zealand.[4] Studies of penguin behaviour and genetics have proposed that the genus Aptenodytes is basal; in other words, that it split off from a branch which led to all other living penguin species.[5] Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests this split occurred around 40 million years ago.[6]

Adult emperor penguins are 110–120 cm (43–47 in) in length, averaging 115 cm (45 in) according to Stonehouse (1975). Due to the method of bird measurement that measures length between bill to tail, sometimes body length and standing height are confused, and some reported height even reaching 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall.[7] There are still more than a few papers mentioning that they reach a standing height of 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) instead of body length.[8][9] Although standing height of emperor penguin is rarely provided at scientific reports, Prévost (1961) recorded 86 wild individuals and measured maximum height of 1.08 m (3 ft 7 in). Friedman (1945) recorded measurements from 22 wild individuals and resulted height ranging 83–97 cm (33–38 in). Ksepka et al. (2012) measured standing height of 81–94 cm (32–37 in) according to 11 complete skins collected in American Museum of Natural History.[7] The weight ranges from 22.7 to 45.4 kg (50 to 100 lb) and varies by sex, with males weighing more than females. It is the fifth heaviest living bird species, after only the larger varieties of ratite.[10] The weight also varies by season, as both male and female penguins lose substantial mass while raising hatchlings and incubating their egg. Male emperor penguins must withstand the extreme Antarctic winter cold for more than two months while protecting their eggs; eating nothing during this time, male emperors will lose around 12 kg (26 lb) while waiting for their eggs to hatch.[11] The mean weight of males at the start of the breeding season is 38 kg (84 lb) and that of females is 29.5 kg (65 lb). After the breeding season this drops to 23 kg (51 lb) for both sexes.[12][13][14]

Like all penguin species, emperor penguins have streamlined bodies to minimize drag while swimming, and wings that are more like stiff, flat flippers.[15] The tongue is equipped with rear-facing barbs to prevent prey from escaping when caught.[16] Males and females are similar in size and colouration.[12] The adult has deep black dorsal feathers, covering the head, chin, throat, back, dorsal part of the flippers, and tail. The black plumage is sharply delineated from the light-coloured plumage elsewhere. The underparts of the wings and belly are white, becoming pale yellow in the upper breast, while the ear patches are bright yellow. The upper mandible of the 8 cm (3.1 in) long bill is black, and the lower mandible can be pink, orange or lilac.[17] In juveniles, the auricular patches, chin and throat are white, while its bill is black.[17] Emperor penguin chicks are typically covered with silver-grey down and have black heads and white masks.[17] A chick with all-white plumage was seen in 2001, but was not considered to be an albino as it did not have pink eyes.[18] Chicks weigh around 315 g (11.1 oz) after hatching, and fledge when they reach about 50% of adult weight.[19]

The emperor penguin's dark plumage fades to brown from November until February (the Antarctic summer), before the yearly moult in January and February.[17] Moulting is rapid in this species compared with other birds, taking only around 34 days. Emperor penguin feathers emerge from the skin after they have grown to a third of their total length, and before old feathers are lost, to help reduce heat loss. New feathers then push out the old ones before finishing their growth.[20]

The average yearly survival rate of an adult emperor penguin has been measured at 95.1%, with an average life expectancy of 19.9 years. The same researchers estimated that 1% of emperor penguins hatched could feasibly reach an age of 50 years.[21] In contrast, only 19% of chicks survive their first year of life.[22] Therefore, 80% of the emperor penguin population comprises adults five years and older.[21]

As the species has no fixed nesting sites that individuals can use to locate their own partner or chick, emperor penguins must rely on vocal sounds alone for identification.[23] They use a complex set of calls that are critical to individual recognition between mates, parents and offspring,[12] displaying the widest variation in individual calls of all penguin species.[23] Vocalizing emperor penguins use two frequency bands simultaneously.[24] Chicks use a frequency-modulated whistle to beg for food and to contact parents.[12]

The emperor penguin breeds in the coldest environment of any bird species; air temperatures may reach −40 °C (−40 °F), and wind speeds may reach 144 km/h (89 mph). Water temperature is a frigid −1.8 °C (28.8 °F), which is much lower than the emperor penguin's average body temperature of 39 °C (102 °F). The species has adapted in several ways to counteract heat loss.[25] Dense feathers provide 80–90% of its insulation and it has a layer of sub-dermal fat which may be up to 3 cm (1.2 in) thick before breeding.[26] While the density of contour feathers is approximately 9 per square centimetre (58 per square inch), a combination of dense afterfeathers and down feathers (plumules) likely play a critical role for insulation.[27][28] Muscles allow the feathers to be held erect on land, reducing heat loss by trapping a layer of air next to the skin. Conversely, the plumage is flattened in water, thus waterproofing the skin and the downy underlayer.[29] Preening is vital in facilitating insulation and in keeping the plumage oily and water-repellent.[30]

The emperor penguin is able to thermoregulate (maintain its core body temperature) without altering its metabolism, over a wide range of temperatures. Known as the thermoneutral range, this extends from −10 to 20 °C (14 to 68 °F). Below this temperature range, its metabolic rate increases significantly, although an individual can maintain its core temperature from 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) down to −47 °C (−53 °F).[31] Movement by swimming, walking, and shivering are three mechanisms for increasing metabolism; a fourth process involves an increase in the breakdown of fats by enzymes, which is induced by the hormone glucagon.[32] At temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F), an emperor penguin may become agitated as its body temperature and metabolic rate rise to increase heat loss. Raising its wings and exposing the undersides increases the exposure of its body surface to the air by 16%, facilitating further heat loss.[33]

.jpg/440px-Aptenodytes_forsteri_(1).jpg)

In addition to the cold, the emperor penguin encounters another stressful condition on deep dives—markedly increased pressure of up to 40 times that of the surface, which in most other terrestrial organisms would cause barotrauma. The bones of the penguin are solid rather than air-filled,[34] which eliminates the risk of mechanical barotrauma.

While diving, the emperor penguin's oxygen use is markedly reduced, as its heart rate is reduced to as low as 15–20 beats per minute and non-essential organs are shut down, thus facilitating longer dives.[16] Its haemoglobin and myoglobin are able to bind and transport oxygen at low blood concentrations; this allows the bird to function with very low oxygen levels that would otherwise result in loss of consciousness.[35]

The emperor penguin has a circumpolar distribution in the Antarctic almost exclusively between the 66° and 77° south latitudes. It almost always breeds on stable pack ice near the coast and up to 18 km (11 mi) offshore.[12] Breeding colonies are usually in areas where ice cliffs and icebergs provide some protection from the wind.[12] Three land colonies have been reported: one (now disappeared) on a shingle spit at the Dion Islands on the Antarctic Peninsula,[36] one on a headland at Taylor Glacier in Victoria Land,[37] and most recently one at Amundsen Bay.[3] Since 2009, a number of colonies have been reported on shelf ice rather than sea ice, in some cases moving to the shelf in years when sea ice forms late.[38]

The northernmost breeding population is on Snow Hill Island, near the northern tip of the Peninsula.[3] Individual vagrants have been seen on Heard Island,[39] South Georgia,[40] and occasionally in New Zealand.[14][41]

In 2009, the total population of emperor penguins was estimated to be at around 595,000 adult birds, in 46 known colonies spread around the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic; around 35% of the known population lives north of the Antarctic Circle. Major breeding colonies were located at Cape Washington, Coulman Island in Victoria Land, Halley Bay, Cape Colbeck, and Dibble Glacier.[42] Colonies are known to fluctuate over time, often breaking into "suburbs" which move apart from the parent group, and some have been known to disappear entirely.[3] The Cape Crozier colony on the Ross Sea shrank drastically between the first visits by the Discovery Expedition in 1902–03[43] and the later visits by the Terra Nova Expedition in 1910–11; it was reduced to a few hundred birds, and may have come close to extinction due to changes in the position of the ice shelf.[44] By the 1960s it had rebounded dramatically,[44] but by 2009 was again reduced to a small population of around 300.[42]

In 2012, the emperor penguin was downgraded from a species of least concern to near threatened by the IUCN.[1][45] Along with nine other species of penguin, it is currently under consideration for inclusion under the US Endangered Species Act. The primary causes for an increased risk of species endangerment are declining food availability, due to the effects of climate change and industrial fisheries on the crustacean and fish populations. Other reasons for the species's placement on the Endangered Species Act's list include disease, habitat destruction, and disturbance at breeding colonies by humans. Of particular concern is the impact of tourism.[46] One study concluded that emperor penguin chicks in a crèche become more apprehensive following a helicopter approach to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[47]

Population declines of 50% in the Terre Adélie region have been observed due to an increased death rate among adult birds, especially males, during an abnormally prolonged warm period in the late 1970s, which resulted in reduced sea-ice coverage. On the other hand, egg hatching success rates declined when the sea-ice extent increased; chick deaths also increased; the species is therefore considered to be highly sensitive to climatic changes.[48] In 2009, the Dion Islands colony, which had been extensively studied since 1948, was reported to have completely disappeared at some point over the previous decade, the fate of the birds unknown. This was the first confirmed loss of an entire colony.[49]

Beginning in September 2015, a strong El Niño, strong winds, and record low amounts of sea ice resulted in "almost total breeding failure" with the deaths of thousands of emperor chicks for three consecutive years within the Halley Bay colony, the second largest emperor penguin colony in the world. Researchers have attributed this loss to immigration of breeding penguins to the Dawson-Lambton colony 55 km (34 mi) south, in which a tenfold population increase was observed between 2016 and 2018. However, this increase is nowhere near the total number of breeding adults formerly at the Halley Bay colony.[50]

In January 2009, a study from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution concluded that global climate change could push the emperor penguin to the brink of extinction by the year 2100. The study constructed a mathematical model to predict how the loss of sea ice from climate warming would affect a big colony of emperor penguins at Terre Adélie, Antarctica. The study forecasted an 87% decline in the colony's population, from three thousand breeding pairs in 2009 to four hundred breeding pairs in 2100.[51]

Another study by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 2014 again concluded that emperor penguins are at risk from global warming, which is melting the sea ice. This study predicted that by 2100 all 45 colonies of emperor penguins will be declining in numbers, mostly due to loss of habitat. Loss of ice reduces the supply of krill, which is a primary food for emperor penguins.[52]

In December 2022, a new colony at Verleger Point in West Antarctica was discovered by satellite imaging, bringing the total known colonies to 66.[53]

In 2023, another study found that more than 90% of emperor penguin colonies could face "quasi-extinction" from "catastrophic breeding failure" due to the loss of sea ice caused by climate change.[54]