En las reacciones de sustitución aromática electrófila , los grupos sustituyentes existentes en el anillo aromático influyen en la velocidad general de la reacción o tienen un efecto director sobre el isómero posicional de los productos que se forman.

Un grupo donador de electrones ( EDG ) o un grupo liberador de electrones ( ERG , Z en fórmulas estructurales) es un átomo o grupo funcional que dona parte de su densidad electrónica a un sistema π conjugado mediante resonancia (mesomería) o efectos inductivos (o inducción). llamados efectos +M o +I , respectivamente, lo que hace que el sistema π sea más nucleofílico . [1] [2] Como resultado de estos efectos electrónicos , es más probable que un anillo aromático al que esté unido dicho grupo participe en la reacción de sustitución electrófila . Por lo tanto, los EDG a menudo se conocen como grupos activadores , aunque los efectos estéricos pueden interferir con la reacción.

Un grupo aceptor de electrones (EWG) tendrá el efecto opuesto sobre la nucleofilicidad del anillo. El EWG elimina densidad electrónica de un sistema π, haciéndolo menos reactivo en este tipo de reacción, [2] [3] y por eso se le llama grupos desactivadores .

Los EDG y EWG también determinan las posiciones (en relación con ellos mismos) en el anillo aromático donde es más probable que se produzcan reacciones de sustitución. Los grupos donadores de electrones son generalmente directores orto/para para las sustituciones aromáticas electrófilas , mientras que los grupos aceptores de electrones (excepto los halógenos ) son generalmente metadirectores . Las selectividades observadas con EDG y EWG se describieron por primera vez en 1892 y se conocen como regla de Crum Brown-Gibson. [4]

Los grupos donadores de electrones generalmente se dividen en tres niveles de capacidad de activación (la categoría "extrema" puede verse como "fuerte"). Los grupos sustractores de electrones se asignan a agrupaciones similares. Los sustituyentes activadores favorecen la sustitución electrófila alrededor de las posiciones orto y para . Los grupos débilmente desactivadores dirigen a los electrófilos a atacar la molécula de benceno en las posiciones orto y para , mientras que los grupos fuertemente y moderadamente desactivantes dirigen los ataques a la posición meta . [5] Este no es un caso de favorecer la metaposición como grupos funcionales directores para y orto, sino más bien desfavorecer las posiciones orto y para más de lo que desfavorecen a la metaposición .

Los grupos activadores son en su mayoría donantes de resonancia (+M). Aunque muchos de estos grupos también se retiran inductivamente (–I), lo cual es un efecto desactivador, el efecto de resonancia (o mesomérico) es casi siempre más fuerte, con la excepción de Cl, Br e I.

En general, el efecto de resonancia de los elementos del tercer período y posteriores es relativamente débil. Esto se debe principalmente a la superposición orbital relativamente pobre del orbital 3p (o superior) del sustituyente con el orbital 2p del carbono.

Debido a un efecto de resonancia y un efecto inductivo más fuertes que los halógenos más pesados, el flúor es anómalo. El factor de velocidad parcial de sustitución aromática electrófila en el fluorobenceno suele ser mayor que uno en la posición para , lo que lo convierte en un grupo activador. [11] Por el contrario, está moderadamente desactivado en las posiciones orto y meta , debido a la proximidad de estas posiciones al sustituyente fluoro electronegativo.

Si bien todos los grupos desactivadores se retiran inductivamente (–I), la mayoría de ellos también se retiran mediante resonancia (–M). Los sustituyentes halógenos son una excepción: son donantes de resonancia (+M). Con excepción de los haluros, son grupos metadirectores .

Los haluros son grupos orto - paradirectores pero, a diferencia de la mayoría de los orto - paradirectores , los haluros desactivan ligeramente el areno. Este comportamiento inusual puede explicarse por dos propiedades:

Las propiedades inductivas y de resonancia compiten entre sí, pero el efecto de resonancia domina a la hora de dirigir los sitios de reactividad. Para la nitración, por ejemplo, el flúor se dirige fuertemente a la posición para porque la posición orto se desactiva inductivamente (86% para , 13% orto , 0,6% meta ). Por otro lado, el yodo se dirige a las posiciones orto y para de manera comparable (54% para y 45% orto , 1,3% meta ). [12]

Aunque la estructura electrónica completa de un areno sólo puede calcularse mediante la mecánica cuántica , los efectos directores de diferentes sustituyentes a menudo pueden adivinarse mediante el análisis de diagramas de resonancia.

Específicamente, cualquier carga formal negativa o positiva en contribuyentes de resonancia menores (los que están de acuerdo con la polarización natural pero que no necesariamente obedecen a la regla del octeto ) reflejan ubicaciones que tienen una densidad de carga mayor o menor en el orbital molecular de un enlace con mayor probabilidad de romperse . Un átomo de carbono con un coeficiente mayor será atacado preferentemente, debido a una superposición orbital más favorable con el electrófilo. [dieciséis]

La perturbación de un grupo conjugante aceptor o donante de electrones hace que la distribución de electrones π en un anillo de benceno se parezca (¡ muy ligeramente !) a un catión bencilo deficiente en electrones o a un anión bencilo excesivo en electrones, respectivamente. Esta última especie admite cálculos cuánticos manejables utilizando la teoría de Hückel : el catión retira densidad electrónica en las posiciones orto y para , favoreciendo el metaataque , mientras que el anión libera densidad electrónica en las mismas posiciones, activándolas para el ataque. [17] Este es precisamente el resultado que predeciría el dibujo de estructuras de resonancia.

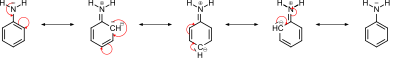

Por ejemplo, la anilina tiene estructuras de resonancia con cargas negativas alrededor del sistema de anillos:

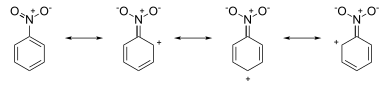

El ataque ocurre en las posiciones orto y para , porque las cargas negativas formales (parciales) en estas posiciones indican un exceso de electrones local. Por otro lado, las estructuras de resonancia del nitrobenceno tienen cargas positivas alrededor del sistema de anillos:

El ataque ocurre en la posición meta , ya que las cargas positivas formales (parciales) en las posiciones orto y para indican deficiencia de electrones en estas posiciones.

Otro argumento común, que hace predicciones idénticas, considera la estabilización o desestabilización por sustituyentes de los intermedios de Wheland resultantes del ataque electrofílico en las posiciones orto / para o meta . El postulado de Hammond dicta entonces que las energías relativas del estado de transición reflejarán las diferencias en las energías del estado fundamental de los intermedios de Wheland. [14] [18]

Debido a la carga positiva total o parcial del elemento directamente unido al anillo de cada uno de estos grupos, todos tienen un efecto inductivo de atracción de electrones de moderado a fuerte (conocido como efecto -I). También exhiben efectos de resonancia atractora de electrones (conocido como efecto -M):

Por lo tanto, estos grupos hacen que el anillo aromático sea muy pobre en electrones (δ+) en relación con el benceno y, por lo tanto, desactivan fuertemente el anillo (es decir, las reacciones proceden mucho más lentamente en los anillos que llevan estos grupos en comparación con las reacciones en el benceno).

Debido a la diferencia de electronegatividad entre el carbono y el oxígeno/nitrógeno, habrá un ligero efecto de extracción de electrones a través del efecto inductivo (conocido como efecto –I). Sin embargo, el otro efecto llamado resonancia añade densidad electrónica al anillo (conocido como efecto +M) y domina sobre el efecto inductivo. Por lo tanto, el resultado es que son EDG y orto / para directores.

El fenol es un director orto/para, pero en presencia de base, la reacción es más rápida. Se debe a la mayor reactividad del anión fenolato . El oxígeno negativo fue "obligado" a dar densidad electrónica a los carbonos (debido a que tiene carga negativa, tiene un efecto +I adicional). Incluso en frío y con electrófilos neutros (y relativamente débiles), la reacción ocurre rápidamente.

Alkyl groups are electron donating groups. The carbon on that is sp3 hybridized and less electronegative than those that are sp2 hybridized. They have overlap on the carbon–hydrogen bonds (or carbon–carbon bonds in compounds like tert-butylbenzene) with the ring p orbital. Hence they are more reactive than benzene and are ortho/para directors.

Inductively, the negatively charged carboxylate ion moderately repels the electrons in the bond attaching it to the ring. Thus, there is a weak electron-donating +I effect. There is an almost zero -M effect since the electron-withdrawing resonance capacity of the carbonyl group is effectively removed by the delocalisation of the negative charge of the anion on the oxygen. Thus overall the carboxylate group (unlike the carboxyl group) has an activating influence.[10]

These groups have a strong electron-withdrawing inductive effect (-I) either by virtue of their positive charge or because of the powerfully electronegativity of the halogens. There is no resonance effect because there are no orbitals or electron pairs which can overlap with those of the ring. The inductive effect acts like that for the carboxylate anion but in the opposite direction (i.e. it produces small positive charges on the ortho and para positions but not on the meta position and it destabilises the Wheland intermediate.) Hence these groups are deactivating and meta directing:

Fluorine is something of an anomaly in this circumstance. Above, it is described as a weak electron withdrawing group but this is only partly true. It is correct that fluorine has a -I effect, which results in electrons being withdrawn inductively. However, another effect that plays a role is the +M effect which adds electron density back into the benzene ring (thus having the opposite effect of the -I effect but by a different mechanism). This is called the mesomeric effect (hence +M) and the result for fluorine is that the +M effect approximately cancels out the -I effect. The effect of this for fluorobenzene at the para position is reactivity that is comparable to (or even higher than) that of benzene. Because inductive effects depends strongly on proximity, the meta and ortho positions of fluorobenzene are considerably less reactive than benzene. Thus, electrophilic aromatic substitution on fluorobenzene is strongly para selective.

This -I and +M effect is true for all halides - there is some electron withdrawing and donating character of each. To understand why the reactivity changes occur, we need to consider the orbital overlaps occurring in each. The valence orbitals of fluorine are the 2p orbitals which is the same for carbon - hence they will be very close in energy and orbital overlap will be favourable. Chlorine has 3p valence orbitals, hence the orbital energies will be further apart and the geometry less favourable, leading to less donation the stabilize the carbocationic intermediate, hence chlorobenzene is less reactive than fluorobenzene. However, bromobenzene and iodobenzene are about the same or a little more reactive than chlorobenzene, because although the resonance donation is even worse, the inductive effect is also weakened due to their lower electronegativities. Thus the overall order of reactivity is U-shaped, with a minimum at chlorobenzene/bromobenzene (relative nitration rates compared to benzene = 1 in parentheses): PhF (0.18) > PhCl (0.064) ~ PhBr (0.060) < PhI (0.12).[12] But still, all halobenzenes reacts slower than benzene itself.

Notice that iodobenzene is still less reactive than fluorobenzene because polarizability plays a role as well. This can also explain why phosphorus in phosphanes can't donate electron density to carbon through induction (i.e. +I effect) although it is less electronegative than carbon (2.19 vs 2.55, see electronegativity list) and why hydroiodic acid (pKa = -10) being much more acidic than hydrofluoric acid (pKa = 3). (That's 1013 times more acidic than hydrofluoric acid)

Due to the lone pair of electrons, halogen groups are available for donating electrons. Hence they are therefore ortho / para directors.

Due to the electronegativity difference between carbon and nitrogen, the nitroso group has a relatively strong -I effect, but not as strong as the nitro group. (Positively charged nitrogen atoms on alkylammonium cations and on nitro groups have a much stronger -I effect)

The nitroso group has both a +M and -M effect, but the -M effect is more favorable.

Nitrogen has a lone pair of electrons. However, the lone pair of its monomer form is unfavourable to donate through resonance. Only the dimer form is available for +M effect. However, the dimer form is less stable in a solution. Therefore, the nitroso group is less available to donate electrons.

Oppositely, withdrawing electron density is more favourable: (see the picture on the right).

.jpg/440px-Nitrosobenzene_resonance_(by_pi_bonds).jpg)

As a result, the nitroso group is a deactivator. However, it has available to donate electron density to the benzene ring during the Wheland intermediate, making it still being an ortho / para director.

There are 2 ortho positions, 2 meta positions and 1 para position on benzene when a group is attached to it. When a group is an ortho / para director with ortho and para positions reacting with the same partial rate factor, we would expect twice as much ortho product as para product due to this statistical effect. However, the partial rate factors at the ortho and para positions are not generally equal. In the case of a fluorine substituent, for instance, the ortho partial rate factor is much smaller than the para, due to a stronger inductive withdrawal effect at the ortho position. Aside from these effects, there is often also a steric effect, due to increased steric hindrance at the ortho position but not the para position, leading to a larger amount of the para product.

The effect is illustrated for electrophilic aromatic substitutions with alkyl substituents of differing steric demand for electrophilic aromatic nitration.[19]

The methyl group in toluene is small and will lead the ortho product being the major product. On the other hand, the t-butyl group is very bulky (there are 3 methyl groups attached to a single carbon) and will lead the para product as the major one. Even with toluene, the product is not 2:1 but having a slightly less ortho product.

When two substituents are already present on the ring, the third substituent's new location is relatively predictable. If the existing substituents reinforce or the molecule is highly symmetric, there may be no ambiguity. Otherwise:[20]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)