The Plesiosauria[a][4] or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million years ago.[5] They became especially common during the Jurassic Period, thriving until their disappearance due to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 66 million years ago. They had a worldwide oceanic distribution, and some species at least partly inhabited freshwater environments.[6]

Plesiosaurs were among the first fossil reptiles discovered. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, scientists realised how distinctive their build was and they were named as a separate order in 1835. The first plesiosaurian genus, the eponymous Plesiosaurus, was named in 1821. Since then, more than a hundred valid species have been described. In the early twenty-first century, the number of discoveries has increased, leading to an improved understanding of their anatomy, relationships and way of life.

Plesiosaurs had a broad flat body and a short tail. Their limbs had evolved into four long flippers, which were powered by strong muscles attached to wide bony plates formed by the shoulder girdle and the pelvis. The flippers made a flying movement through the water. Plesiosaurs breathed air, and bore live young; there are indications that they were warm-blooded.

Plesiosaurs showed two main morphological types. Some species, with the "plesiosauromorph" build, had (sometimes extremely) long necks and small heads; these were relatively slow and caught small sea animals. Other species, some of them reaching a length of up to seventeen metres, had the "pliosauromorph" build with a short neck and a large head; these were apex predators, fast hunters of large prey. The two types are related to the traditional strict division of the Plesiosauria into two suborders, the long-necked Plesiosauroidea and the short-neck Pliosauroidea. Modern research, however, indicates that several "long-necked" groups might have had some short-necked members or vice versa. Therefore, the purely descriptive terms "plesiosauromorph" and "pliosauromorph" have been introduced, which do not imply a direct relationship. "Plesiosauroidea" and "Pliosauroidea" today have a more limited meaning. The term "plesiosaur" is properly used to refer to the Plesiosauria as a whole, but informally it is sometimes meant to indicate only the long-necked forms, the old Plesiosauroidea.

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such.[7] In 1605, Richard Verstegen of Antwerp illustrated in his A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence plesiosaur vertebrae that he referred to fishes and saw as proof that Great Britain was once connected to the European continent.[8] The Welshman Edward Lhuyd in his Lithophylacii Brittannici Ichnographia from 1699 also included depictions of plesiosaur vertebrae that again were considered fish vertebrae or Ichthyospondyli.[9] Other naturalists during the seventeenth century added plesiosaur remains to their collections, such as John Woodward; these were only much later understood to be of a plesiosaurian nature and are today partly preserved in the Sedgwick Museum.[7]

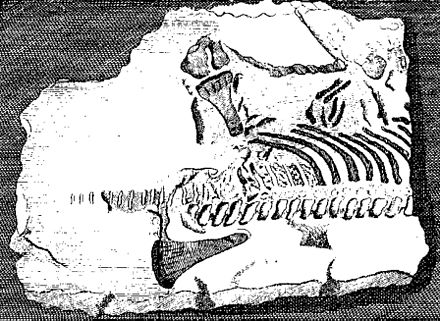

In 1719, William Stukeley described a partial skeleton of a plesiosaur, which had been brought to his attention by the great-grandfather of Charles Darwin, Robert Darwin of Elston. The stone plate came from a quarry at Fulbeck in Lincolnshire and had been used, with the fossil at its underside, to reinforce the slope of a watering-hole in Elston in Nottinghamshire. After the strange bones it contained had been discovered, it was displayed in the local vicarage as the remains of a sinner drowned in the Great Flood. Stukely affirmed its "diluvial" nature but understood it represented some sea creature, perhaps a crocodile or dolphin.[10] The specimen is today on display at the Natural History Museum, and its inventory number is NHMUK PV R.1330 (formerly BMNH R.1330). It is the earliest discovered more or less complete fossil reptile skeleton in a museum collection. It can perhaps be referred to Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus.[7]

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the Vale of Belvoir, whose collections were in 1795 described by John Nicholls in the first part of his The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicestershire.[11] One of Turner's partial plesiosaur skeletons is still preserved as specimen NHMUK PV R.45 (formerly BMNH R.45) in the British Museum of Natural History; this is today referred to Thalassiodracon.[7]

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with ichthyosaurs, so the fossils of one group were sometimes combined with those of the other to obtain a more complete specimen. In 1821, a partial skeleton discovered in the collection of Colonel Thomas James Birch,[12] was described by William Conybeare and Henry Thomas De la Beche, and recognised as representing a distinctive group. A new genus was named, Plesiosaurus. The generic name was derived from the Greek πλήσιος, plèsios, "closer to" and the Latinised saurus, in the meaning of "saurian", to express that Plesiosaurus was in the Chain of Being more closely positioned to the Sauria, particularly the crocodile, than Ichthyosaurus, which had the form of a more lowly fish.[13] The name should thus be rather read as "approaching the Sauria" or "near reptile" than as "near lizard".[14] Parts of the specimen are still present in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.[7]

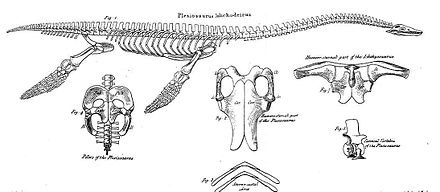

Soon afterwards, the morphology became much better known. In 1823, Thomas Clark reported an almost complete skull, probably belonging to Thalassiodracon, which is now preserved by the British Geological Survey as specimen BGS GSM 26035.[7] The same year, commercial fossil collector Mary Anning and her family uncovered an almost complete skeleton at Lyme Regis in Dorset, England, on what is today called the Jurassic Coast. It was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham, who made it available to the geologist William Buckland. He in turn let it be described by Conybeare on 24 February 1824 in a lecture to the Geological Society of London,[15] during the same meeting in which for the first time a dinosaur was named, Megalosaurus. The two finds revealed the unique and bizarre build of the animals, in 1832 by Professor Buckland likened to "a sea serpent run through a turtle". In 1824, Conybeare also provided a specific name to Plesiosaurus: dolichodeirus, meaning "longneck". In 1848, the skeleton was bought by the British Museum of Natural History and catalogued as specimen NHMUK OR 22656 (formerly BMNH 22656).[7] When the lecture was published, Conybeare also named a second species: Plesiosaurus giganteus. This was a short-necked form later assigned to the Pliosauroidea.[16]

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri of 1834[17] and The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals,[18] seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history.[19] Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.[20]

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus Plesiosaurus is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a wastebasket taxon. Gradually, other genera were named. Hawkins had already created new genera, though these are no longer seen as valid. In 1841, Owen named Pliosaurus brachydeirus. Its etymology referred to the earlier Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus as it is derived from πλεῖος, pleios, "more fully", reflecting that according to Owen it was closer to the Sauria than Plesiosaurus. Its specific name means "with a short neck".[21] Later, the Pliosauridae were recognised as having a morphology fundamentally different from the plesiosaurids. The family Plesiosauridae had already been coined by John Edward Gray in 1825.[22] In 1835, Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville named the order Plesiosauria itself.[23]

In the second half of the nineteenth century, important finds were made outside of England. While this included some German discoveries, it mainly involved plesiosaurs found in the sediments of the American Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway, the Niobrara Chalk. One fossil in particular marked the start of the Bone Wars between the rival paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh.

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace in Kansas uncovered a plesiosaur skeleton, which he donated to Cope.[24] Cope attempted to reconstruct the animal on the assumption that the longer extremity of the vertebral column was the tail, the shorter one the neck. He soon noticed that the skeleton taking shape under his hands had some very special qualities: the neck vertebrae had chevrons and with the tail vertebrae the joint surfaces were orientated back to front.[25] Excited, Cope concluded to have discovered an entirely new group of reptiles: the Streptosauria or "Turned Saurians", which would be distinguished by reversed vertebrae and a lack of hindlimbs, the tail providing the main propulsion.[26] After having published a description of this animal,[27] followed by an illustration in a textbook about reptiles and amphibians,[28] Cope invited Marsh and Joseph Leidy to admire his new Elasmosaurus platyurus. Having listened to Cope's interpretation for a while, Marsh suggested that a simpler explanation of the strange build would be that Cope had reversed the vertebral column relative to the body as a whole. When Cope reacted indignantly to this suggestion, Leidy silently took the skull and placed it against the presumed last tail vertebra, to which it fitted perfectly: it was in fact the first neck vertebra, with still a piece of the rear skull attached to it.[29] Mortified, Cope tried to destroy the entire edition of the textbook and, when this failed, immediately published an improved edition with a correct illustration but an identical date of publication.[30] He excused his mistake by claiming that he had been misled by Leidy himself, who, describing a specimen of Cimoliasaurus, had also reversed the vertebral column.[31] Marsh later claimed that the affair was the cause of his rivalry with Cope: "he has since been my bitter enemy". Both Cope and Marsh in their rivalry named many plesiosaur genera and species, most of which are today considered invalid.[32]

Around the turn of the century, most plesiosaur research was done by a former student of Marsh, Professor Samuel Wendell Williston. In 1914, Williston published his Water reptiles of the past and present.[33] Despite treating sea reptiles in general, it would for many years remain the most extensive general text on plesiosaurs.[34] In 2013, a first modern textbook was being prepared by Olivier Rieppel. During the middle of the twentieth century, the USA remained an important centre of research, mainly through the discoveries of Samuel Paul Welles.

Whereas during the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, new plesiosaurs were described at a rate of three or four novel genera each decade, the pace suddenly picked up in the 1990s, with seventeen plesiosaurs being discovered in this period. The tempo of discovery accelerated in the early twenty-first century, with about three or four plesiosaurs being named each year.[35] This implies that about half of the known plesiosaurs are relatively new to science, a result of a far more intense field research. Some of this is taking place away from the traditional areas, e.g. in new sites developed in New Zealand, Argentina, Chile,[36] Norway, Japan, China and Morocco, but the locations of the more original discoveries have proven to be still productive, with important new finds in England and Germany. Some of the new genera are a renaming of already known species, which were deemed sufficiently different to warrant a separate genus name.

In 2002, the "Monster of Aramberri" was announced to the press. Discovered in 1982 at the village of Aramberri, in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León, it was originally classified as a dinosaur. The specimen is actually a very large plesiosaur, possibly reaching 15 m (49 ft) in length. The media published exaggerated reports claiming it was 25 metres (82 ft) long, and weighed up to 150,000 kilograms (330,000 lb), which would have made it among the largest predators of all time.[37][38]

In 2004, what appeared to be a completely intact juvenile plesiosaur was discovered, by a local fisherman, at Bridgwater Bay National Nature Reserve in Somerset, UK. The fossil, dating from 180 million years ago as indicated by the ammonites associated with it, measured 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) in length, and may be related to Rhomaleosaurus. It is probably the best